Abstract

Recent research into the flowering of rice (Oryza sativa) has revealed both unique and conserved genetic pathways in the photoperiodic control of flowering compared with those in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). We discovered an early heading date2 (ehd2) mutant that shows extremely late flowering under both short- and long-day conditions in line with a background deficient in Heading date1 (Hd1), a rice CONSTANS ortholog that belongs to the conserved pathway. This phenotype in the ehd2 mutants suggests that Ehd2 is pivotal for the floral transition in rice. Map-based cloning revealed that Ehd2 encodes a putative transcription factor with zinc finger motifs orthologous to the INDETERMINATE1 (ID1) gene, which promotes flowering in maize (Zea mays). Ehd2 mRNA in rice tissues accumulated most abundantly in developing leaves, but was present at very low levels around the shoot apex and in roots, patterns that are similar to those of ID1. To assign the position of Ehd2 within the flowering pathway of rice, we compared transcript levels of previously isolated flowering-time genes, such as Ehd1, a member of the unique pathway, Hd3a, and Rice FT-like1 (RFT1; rice florigens), between the wild-type plants and the ehd2 mutants. Severely reduced expression of these genes in ehd2 under both short- and long-day conditions suggests that Ehd2 acts as a flowering promoter mainly by up-regulating Ehd1 and by up-regulating the downstream Hd3a and RFT1 genes in the unique genetic network of photoperiodic flowering in rice.

Flowering is one of the fundamental events in the life cycle of many higher plants and is a very important trait for determining the ability of a species to adapt to various environmental conditions. Flowering time is largely determined by the timing of the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth and is controlled by both environmental signals and developmental programs. Photoperiod (i.e. daylength) is an important environmental signal that determines flowering time in plants and recent molecular genetic research in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) has revealed how plant sensitivity to photoperiod controls flowering time (Kobayashi and Weigel, 2008; Turck et al., 2008). It has been demonstrated that the CONSTANS (CO) transcription factor up-regulates the transcription of the FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) gene in Arabidopsis leaves in response to induction by long daylength (Kardailsky et al., 1999; Kobayashi et al., 1999; Samach et al., 2000; Suarez-Lopez et al., 2001; Yanovsky and Kay, 2002; Valverde et al., 2004). FT protein then moves to the shoot apex, where it interacts with the transcription factor encoded by FD to activate genes that determine floral organ identity and consequently induces flowering (Abe et al., 2005; Wigge et al., 2005; Corbesier et al., 2007).

A genetic pathway similar to that in Arabidopsis is conserved in the photoperiodic control of flowering in rice (Oryza sativa), a short-day (SD) plant. Heading date1 (Hd1) is one of the first flowering-related genes to have been cloned from a natural variant of rice (Yano et al., 2000). The Arabidopsis CO promotes flowering only under long-day (LD) conditions, whereas Hd1 (a CO ortholog in rice) promotes flowering under SD conditions and represses it under LD conditions (Yano et al., 2000). Another flowering-related gene, Hd3a, is a rice ortholog of FT and is regulated by Hd1 (Izawa et al., 2002; Kojima et al., 2002). Recently, Tamaki et al. (2007) demonstrated that the Hd3a protein functions as a mobile florigen-type flowering signal. Additionally, Rice FT-like1 (RFT1), the closest homolog of Hd3a, may act redundantly to Hd3a as a floral promoter (Izawa et al., 2002; Kojima et al., 2002; Komiya et al., 2008). In Arabidopsis, the CO/FT module is regulated by GIGANTEA (GI), which is a component of the genes related to the circadian clock (Suarez-Lopez et al., 2001; Sawa et al., 2007). Similarly, it has been demonstrated that regulation of the Hd1/Hd3a module is mediated by OsGI, a rice ortholog of GI (Hayama et al., 2003). These findings reveal that a common floral induction pathway from CO to FT in photoperiodic control of flowering is conserved in both Arabidopsis and rice, but that the photoperiodic response has differentiated between these LD and SD (respectively) plants. On the other hand, Early heading date1 (Ehd1) is a flowering time gene unique to rice that encodes a B-type response regulator, with no obvious counterpart in the Arabidopsis genome (Doi et al., 2004). Ehd1 promotes floral transition preferentially under SD conditions, even in the absence of functional alleles of Hd1. Expression analysis revealed that Ehd1 functions upstream of Hd3a, RFT1, and some MADS-box genes (Doi et al., 2004). More recently, Ghd7, which encodes a CCT (CO, CO-LIKE, and TIMING OF CAB1)-domain protein was isolated from natural variations in rice (Xue et al., 2008). Ghd7 affects levels of Ehd1 and Hd3a transcripts, but does not affect Hd1 mRNA levels. Ghd7 represses Ehd1 and Hd3a expression under LD conditions, thereby delaying flowering. Thus, two independent floral pathways are present in rice: the conserved Hd1 pathway and a unique Ehd1 pathway that may integrate environmental photoperiod signals into the expression of FT-like genes (Izawa, 2007).

Although the recent rapid accumulation of knowledge about the genetic control of flowering in rice has been largely based on the analysis of natural variations (Yano et al., 2001; Kojima et al., 2002; Doi et al., 2004; Xue et al., 2008), a large part of the control pathway remains to be analyzed compared with Arabidopsis, in which analysis of this pathway has progressed mainly by using flowering mutants (for review, see Koornneef et al., 1998; Kobayashi and Weigel, 2008; Turck et al., 2008). Therefore, to comprehensively understand the genetic control of flowering in rice, we require more analysis of mutants as well as natural variants.

In this study, we discovered an ehd2 mutant that flowers extremely late compared with wild-type plants under both SD and LD conditions. The presence of this phenotype in the ehd2 mutants suggested that the wild-type gene (Ehd2) essentially acts as a flowering promoter. In this article, we describe molecular cloning of Ehd2 and the gene's role in the control of photoperiodic flowering in rice. No significant morphological aberration was observed in the vegetative and reproductive organs of the ehd2 mutants. Map-based cloning revealed that Ehd2 encodes a putative transcription factor with zinc finger motifs, which is orthologous to the INDETERMINATE1 (ID1) gene in maize (Zea mays). Mutations in ID1 have severe effects on the floral transition (Singleton, 1946; Colasanti et al., 1998): The late-flowering phenotype demonstrated that ID1 is essential for normal floral transition. The ID1 gene is expressed specifically in developing leaves (Colasanti et al., 1998; Kozaki et al., 2004; Wong and Colasanti, 2007). The floral induction pathway mediated by ID1 may be unique to monocots because no clear ID1 ortholog is present in Arabidopsis (Colasanti et al., 2006). Rice, which is closely related to maize, has a putative ID1 ortholog with a leaf-specific accumulation of protein similar to that in maize (Colasanti et al., 2006). However, its role in controlling flowering time remains to be clarified. Expression analysis of genes related to rice flowering in the ehd2 mutant and the wild type, and genetic interactions between Hd1 and Ehd2, demonstrated that Ehd2 promotes floral transition mainly by up-regulating Ehd1 and genes downstream of Ehd1, such as Hd3a and RFT1. These results indicate the critical role of a unique genetic flowering pathway in monocotyledonous plants such as rice.

RESULTS

Phenotypes of the ehd2 Mutant

The ehd2 mutant was identified as a late-flowering variant of the M2 plants from a γ-ray-mutagenized line of rice cv Tohoku IL9 (subsp. japonica). Flowering time of the ehd2 mutants (177.0 ± 13.2 d) was delayed by more than 77 d compared with the wild-type plants (99.4 ± 1.1 d) under natural-day (ND) conditions (Fig. 1A).

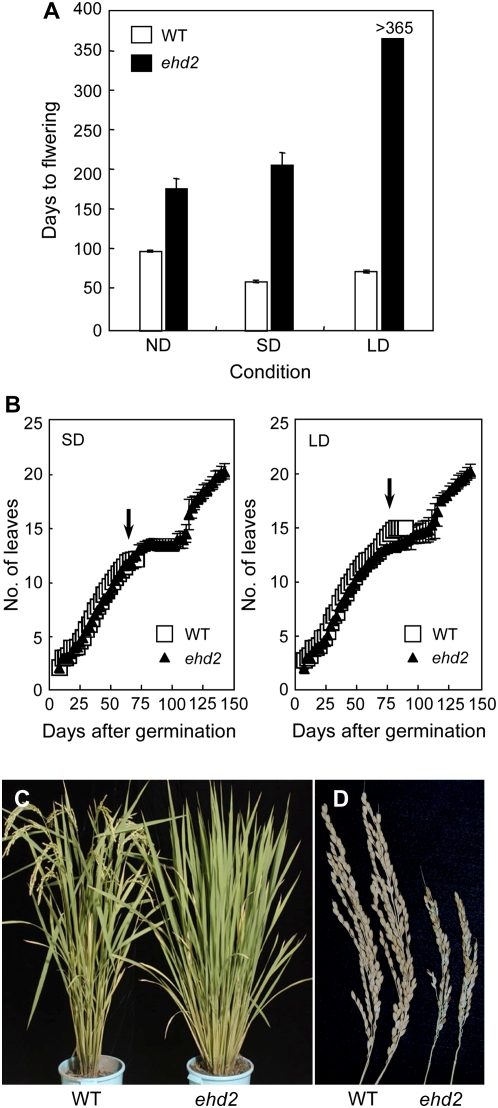

Figure 1.

Flowering date phenotypes of the ehd2 mutant compared with those of the wild-type plant (cv Tohoku IL9). A, Days to flowering of the wild-type plants and the ehd2 mutants under different photoperiodic conditions (means ± sd, n = 10). B, Comparison of leaf emergence rates between wild-type plants and ehd2 mutants under SD and LD conditions during development (means ± sd, n = 5). Leaf emergence rate was calculated according to the measurements described by Itoh et al. (1998). Average days to flowering of the wild-type plants are shown by an arrowhead. C, Wild-type plant (left) and ehd2 mutant (right) under ND conditions after flowering of the wild-type plant. D, Inflorescences of a wild-type plant (left) and the ehd2 mutant (right).

To test whether the flowering times of the ehd2 mutants differed among photoperiodic conditions, we grew the mutants and corresponding wild-type plants under SD conditions (10 h light/14 h dark) and LD conditions (14.5 h light/9.5 h dark). Under SD conditions, flowering time of the ehd2 mutants was 206.5 d, an increase of 145 d compared with the wild-type plants (61.5 ± 1.3 d; Fig. 1A). Under LD conditions, the ehd2 mutants never flowered during more than 365 d, whereas the wild-type plants flowered at 73.7 ± 2.1 d (Fig. 1A). The difference in flowering time in the wild-type plants under the SD and LD conditions was small (12 d; Fig. 1A). Thus, the ehd2 mutants showed extremely late flowering compared with the wild-type plants under both conditions, although the mutation had a more severe effect on flowering time under LD conditions.

To examine whether a reduction in growth rate or a prolonged plastochron might have caused the late flowering in the ehd2 mutants, we next compared the leaf emergence rate between the ehd2 mutants and the wild-type plants until 144 d. The wild-type plants flowered after 12 leaves had emerged under SD conditions and after 15 leaves had emerged under LD conditions (Fig. 1B). Before flowering of the wild-type plants, the leaf emergence rate of the ehd2 mutants was almost indistinguishable from that of the wild-type plants under both SD and LD conditions (Fig. 1B). Under both conditions, the ehd2 mutants had developed 20 leaves by 144 d after germination. By the time the wild-type plants flowered, the leaf size and plant height in the ehd2 mutants were similar to those in the wild-type plants under ND conditions (Fig. 1C). The ehd2 mutants eventually flowered under ND and SD conditions (Fig. 1A). No significant morphological aberration was evident in the ehd2 mutants, although the inflorescences with ripened seeds were smaller than those of the wild-type plants (Fig. 1D). Thus, the growth rate and development of the inflorescences were not affected by the ehd2 mutation. These results demonstrate that Ehd2 controls the floral transition in rice, but not its growth rates.

Ehd2 Encodes a Putative Transcription Factor

We then performed map-based cloning of ehd2. The ehd2 mutant was first crossed with an indica cultivar (Guang Lu Ai 4), and the resultant F1 was backcrossed with cv Guang Lu Ai 4. It was easy to obtain sufficient DNA marker polymorphisms between japonica and indica rice. The ehd2 phenotype segregated as a monogenic recessive trait in the BC1F2 population (Supplemental Fig. S1). Because the mutant phenotype behaved as a complete recessive, the mutation appears to have been caused by an absence of Ehd2 function. We next performed bulked segregant analysis using plants with normal and mutant phenotypes from the BC1F2 population. The result of the analysis revealed that a simple sequence repeat (SSR) marker (RM6124) on chromosome 10 was linked to the gene for the mutant phenotype (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, a high-resolution linkage analysis demonstrated that ehd2 is delimited within a 13.9-kb genomic region between two single-nucleotide polymorphisms, SNP-1 and SNP-2, on chromosome 10 (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Table S1). An SSR marker (SSR-1) showed cosegregation with the mutant phenotype (Supplemental Table S1). In this candidate region, two putative proteins, a zinc finger protein (Os10g0419200) and a heat shock transcription factor (Os10g0419300), were annotated in the Rice Annotation Project Database (http://rapdb.dna.affrc.go.jp; zinc finger and heat shock transcription factor, respectively; Fig. 2B). Comparison of the sequence of the candidate region between the ehd2 mutant and the wild-type Ehd2 plants revealed a 4-bp insertion within the second exon of the putative zinc finger protein in the ehd2 mutant (Fig. 2C), resulting in a premature stop codon in the open reading frame (ORF). No other nucleotide polymorphisms were observed in this 13.9-kb candidate region. A homology search using tBLASTn software (http://blast.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/top-j.html) revealed that the putative zinc finger protein is a rice homolog of the maize ID1 protein (accession no. AF058757) that is involved in the transition to flowering (Colasanti et al., 1998). The two proteins shared 58% amino acid identity over the entire peptide sequence, but fasta software (http://fasta.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/top-j.html) indicated that the identity between the putative zinc finger domains reached 82%.

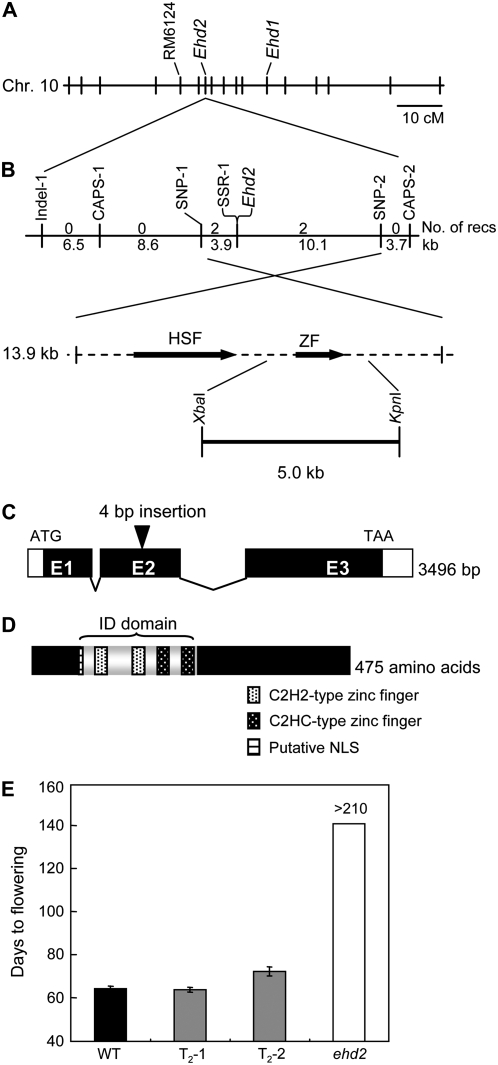

Figure 2.

Results of the map-based cloning of Ehd2. A, Location of Ehd2 on chromosome 10. B, High-resolution linkage map of Ehd2 (n = 2,047). A 5.0-kb genomic fragment digested by XbaI and KpnI from cv Nipponbare was introduced into the ehd2 mutant. HSF, Heat shock factor; ZF, zinc finger protein. C, Structure of Ehd2. E1, E2, and E3 represent exons. White boxes represent the 5′-untranslated region (left) and the 3′-untranslated region (right), respectively. The structure of the mRNA was determined by RACE. D, Structure of the Ehd2 protein. E, Days to flowering of two independent T2 lines homozygous for the Ehd2 transgene from cv Nipponbare under SD (10 h light/14 h dark) conditions (means ± sd, n = 10).

The 3,496-bp Ehd2 gene consisted of three exons and two introns (Fig. 2C). The deduced sequence of 475 amino acids in the protein had a nuclear localization signal motif (KKKR) and four zinc finger motifs (two C2H2-type and two C2HC-type), previously designated as the ID domain (Fig. 2D; Supplemental Fig. S2; Kozaki et al., 2004). In addition, the deduced C-terminal peptide sequence of the Ehd2 protein was nearly identical to the 19 C-terminal amino acids of maize ID1 (17/19 amino acids). A phylogenetic analysis among the deduced amino acid sequences of rice, maize, and the Arabidopsis ID domain revealed that Ehd2 is a rice ortholog of the maize ID1 gene (Supplemental Fig. S3; also inferred by Colasanti et al., 2006). A synteny conservation between the harbored regions of Ehd2 (rice chromosome 10) and ID1 (maize chromosome 1) also supported the results of the phylogenetic analysis (Rice Chromosome 10 Sequencing Consortium, 2003).

To demonstrate that the ehd2 mutant phenotype was caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the putative zinc finger protein, we complemented ehd2 by transforming it with the corresponding cv Nipponbare genomic fragment; cv Nipponbare had a sequence for the putative Ehd2 ORF identical to that of cv Tohoku IL9. The 5.0-kb fragment consisted of a 0.9-kb upstream sequence, the putative coding region, and a 0.7-kb downstream sequence digested by XbaI and KpnI. In these transgenic plants, the Ehd2 phenotype was restored under SD conditions (Fig. 2E). These results confirmed that Ehd2 encodes the ID1 ortholog.

Ehd2 mRNA Is Abundant in the Developing Leaf

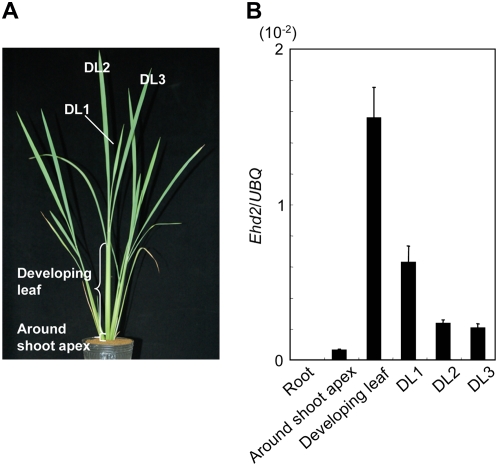

Previous studies in maize revealed that ID1 mRNA appears exclusively in developing leaves (Colasanti et al., 1998; Wong and Colasanti, 2007). Therefore, we examined the level of Ehd2 transcripts in several rice tissues (Fig. 3A) by means of quantitative real-time (RT)-PCR under LD conditions. A clear gradient in the level of Ehd2 transcripts was observed among the rice tissues (Fig. 3B). Ehd2 mRNA accumulated most abundantly in developing leaves within the leaf sheath (1.55 × 10−2). In the blades of the developed leaves (DL), it gradually decreased as the leaves aged to 0.63 × 10−2 in DL1, 0.23 × 10−2 in DL2, and 0.20 × 10−2 in DL3. Levels were low around the shoot apex (0.06 × 10−2) and transcripts were undetectable in the roots. These results demonstrate that rice Ehd2 mRNA accumulated most abundantly in developing leaf tissues, as maize ID1 has been observed to do, but was also present in mature leaves, although at much lower levels.

Figure 3.

Ehd2 mRNA expression in different tissues of rice. A, Wild-type plant 30 d after germination grown under LD conditions (14.5 h light/9.5 h dark). B, Quantitative RT-PCR results for Ehd2 mRNA in different tissues. Values are shown as means ± sd of three independent experiments. DL, Developed leaf; UBQ, ubiquitin. Tissue samples were collected at 2 h after dawn. Data are representative of two independent biological replicates. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Ehd2 Promotes Flowering by Up-Regulating Ehd1, Hd3a, and RFT1

To identify potential downstream genes that are regulated by Ehd2, we examined the transcript levels of five flowering-related genes (Ehd2, Hd1, Ehd1, Hd3a, and RFT1) by means of quantitative RT-PCR. Leaf samples were collected from 3-week-old and 30-d-old plants grown under SD and LD conditions, respectively. The developmental stage of these plants was about 40 d before flowering.

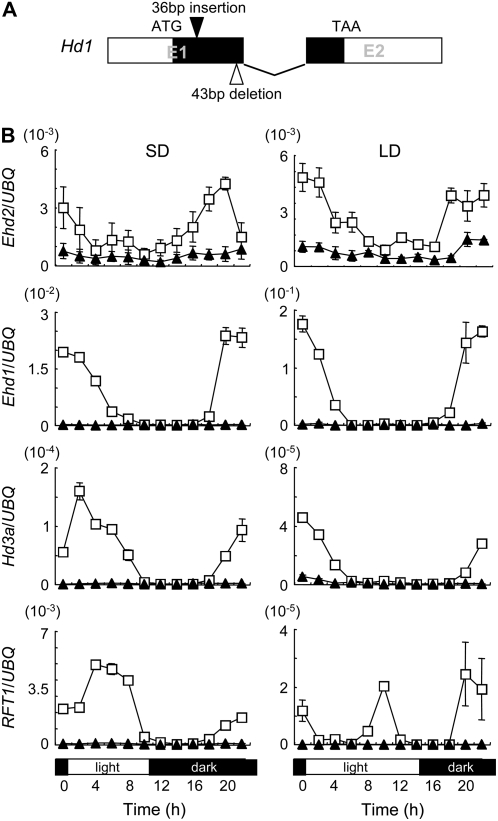

We found that the ehd2 mutant and the wild type both carried a defective Hd1 allele (accession no. AB433218) derived from the japonica cv Sasanishiki. The defective allele had a 43-bp deletion and a 36-bp insertion in the first exon compared with the functional cv Nipponbare Hd1 allele (accession no. AB041837), resulting in a premature stop codon (Fig. 4A). Nonetheless, the Hd1 mRNA expression was observed in the wild-type plants and the mutants under both SD and LD conditions with a clear diurnal change (Supplemental Fig. S4). However, the level of the Hd1 transcripts in the ehd2 mutants was reduced under both SD and LD conditions compared with that of the wild-type plants. The results suggested that Ehd2 up-regulates Hd1 mRNA expression.

Figure 4.

Ehd2 up-regulates Ehd1, Hd3a, and RFT1 (increases the level of their transcripts). A, Defective cv Tohoku IL9 allele of Hd1. E1 and E2 represent exons. White boxes represent the 5′- untranslated region (left) and the 3′- untranslated region (right), respectively. B, Diurnal changes in levels of Ehd2, Ehd1, Hd3a, and RFT1 transcripts under SD (10 h light/14 h dark) and LD (14.5 h light/9.5 h dark) conditions. UBQ, Ubiquitin. White squares represent wild-type plants; black triangles represent the ehd2 mutants. Developing leaves were harvested every 2 h. Values are shown as mean ± sd of three independent experiments. Data are representative of two independent biological replicates.

In the wild-type plants under SD conditions, the level of Ehd2 transcripts started to increase after dusk and reached a peak before dawn (Fig. 4B). Then the Ehd2 transcript level decreased once and increased again just before dawn. The Ehd2 transcript level decreased gradually after dawn. Thus, Ehd2 mRNA expression showed a clear diurnal change. The patterns of accumulation of Ehd1, Hd3a, and RFT1 mRNAs appeared to parallel Ehd2 expression, with a short delay, suggesting transcriptional regulation of these genes by Ehd2, although these transcripts remained abundant during the daytime, gradually decreasing until dusk. In contrast, Ehd2 mRNA in the ehd2 mutants remained at very low levels all day, with no sign of diurnal variation, possibly as a result of nonsense-mediated decay of the mRNA. Levels of Ehd1, Hd3a, and RFT1 mRNAs decreased dramatically to nearly undetectable levels in the ehd2 mutants. Under LD conditions, Ehd2 mRNA showed diurnal changes in the wild-type plants and, to a much lesser extent, in the ehd2 mutants (Fig. 4B). The pattern of accumulation of Ehd1, Hd3a, and RFT1 in the wild-type plants was apparently more synchronized with Ehd2 expression under LD conditions than under SD conditions, except that a second peak of RFT1 expression was apparent during the daytime. In the ehd2 mutants, the accumulation of Ehd1, Hd3a, and RFT1 mRNAs was also repressed, at a significantly lower level, as was the case under SD conditions. These results demonstrated that Ehd2 up-regulates the transcription of Ehd1 and of the downstream FT-like genes, Hd3a and RFT1, under both SD and LD conditions, thereby promoting the floral transition.

To further examine whether Ehd2 regulates any other genes, we performed a microarray analysis of wild-type plants and ehd2 mutants grown under LD conditions, with approximately 44,000 rice gene probes. Leaf samples were collected from 30-d-old plants 2 h after dawn. As expected, the level of Ehd2 transcripts was dramatically less in the ehd2 mutants than in the wild-type plants (Supplemental Table S2). The difference in levels of Ehd1 transcripts between the wild-type plants and the ehd2 mutants showed the greatest down-regulation among the genes we examined (Supplemental Table S2). In addition to transcripts of Ehd1, the transcript levels of putative NO APICAL MERISTEM (NAM) protein domain-containing protein (Os08g0200600; Supplemental Fig. S5) and of α-l-arabinofuranosidase/β-d-xylosidase isoenzyme (ARA-I; Os04g0640700) were also greatly reduced in the ehd2 mutants, but the roles of these proteins in floral induction is unknown, and further analysis is needed. The results of this analysis strongly support the hypothesis that Ehd2 up-regulates Ehd1 and that Ehd1 is the primary downstream gene of the Ehd2 protein.

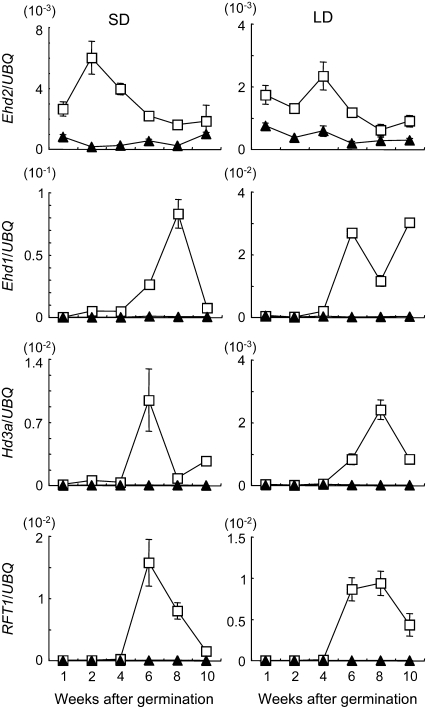

Levels of Ehd2 Transcripts and Expression of Downstream Genes during Development

To examine the accumulation of Ehd2, Ehd1, Hd3a, and RFT1 mRNAs during development, we harvested developed leaves from wild-type plants and ehd2 mutants at different developmental stages and analyzed them by means of quantitative RT-PCR. The samples were collected 2 h after dawn under SD and LD conditions. In the wild-type plants under SD conditions, Ehd2 mRNA was observed by 1 week after germination and reached a peak by 2 weeks (Fig. 5). Subsequently, the level gradually decreased, but transcripts were detected continuously at low levels even after flowering of the wild-type plants (about 9 weeks). The accumulation of Ehd1 mRNA was detected at 2 weeks after germination, and increased greatly thereafter to reach a peak at 8 weeks. Hd3a mRNA was also observed at 2 weeks, then began to increase, and reached a peak at 6 weeks. RFT1 mRNA was present at very low levels until 4 weeks, then began to increase, and reached a peak at 6 weeks. After flowering, levels of Ehd1, Hd3a, and RFT1 mRNAs decreased. Under LD conditions in wild-type plants, the level of Ehd2 transcripts was low during all developmental stages (Fig. 5), although transcription was detected from at least 1 week after germination. Ehd1, Ehd3a, and RFT1 mRNAs were less abundant than under SD conditions, although transcription increased after 4 weeks.

Figure 5.

Change in levels of Ehd2, Ehd1, Hd3a, and RFT1 transcripts during development under SD (10 h light/14 h dark) and LD (14.5 h light/9.5 h dark) conditions. UBQ, Ubiquitin. White squares represent wild-type plants; black triangles represent ehd2 mutants. Developing leaves were harvested 2 h after dawn. Values are shown as mean ± sd of three independent experiments. Data are representative of two independent biological replicates.

In contrast, the transcription of Ehd2 was very low in the ehd2 mutants, and Ehd1, Hd3a, and RFT1 transcripts were almost undetectable throughout all stages of development under both SD and LD conditions. These results further suggest that Ehd2 functions upstream of Ehd1 and of the FT-like genes.

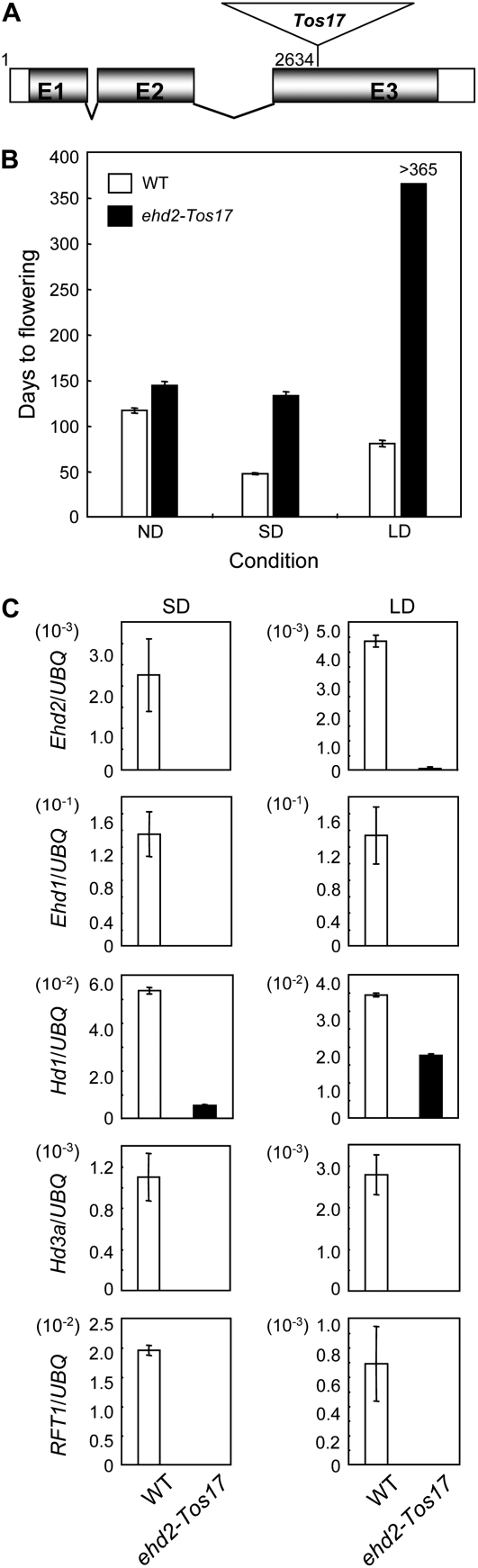

Ehd2 Functions Upstream of Hd1

Because cv Tohoku IL9 (the wild-type of the ehd2 mutant) carried a defective allele at the Hd1 locus, the functional relationship between Ehd2 and Hd1 remained unconfirmed (Fig. 4A). Therefore, we screened Tos17-induced mutant lines (http://tos.nias.affrc.go.jp/∼miyao/pub/tos17) and found an ehd2 mutant with a Tos17 insertion in cv Nipponbare, which carries a functional allele at the Hd1 locus (Yano et al. 2000). A sequence analysis of the flanking Tos17 insertion revealed that the retrotransposon was inserted in the third exon of Ehd2 (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Characteristics of the ehd2-Tos17 mutants. A, Diagram of the ehd2 mutant disrupted by Tos17 (i.e. ehd2-Tos17). B, Days to flowering of wild-type plants (cv Nipponbare) and of the ehd2-Tos17 mutants under different daylength conditions (means ± sd, n = 10). C, Levels of Ehd2, Ehd1, Hd1, Hd3a, and RFT1 transcripts in the ehd2-Tos17 mutants under SD and LD conditions. Values are shown as means ± sd of three independent experiments. UBQ, Ubiquitin. Developing leaves were harvested 2 h after dawn under SD conditions for analysis of Ehd2, Ehd1, Hd3a, and RFT1, and after dusk for Hd1. Data are representative of two independent biological replicates.

Under ND conditions, the wild-type plants (cv Nipponbare) flowered at 116.6 ± 2.8 d and the Tos17-induced mutants of Ehd2 (hereafter referred to as ehd2-Tos17) flowered at 144.1 ± 4.3 d without significant morphological aberration (Fig. 6B). We grew the ehd2-Tos17 mutants and the wild-type plants under SD and LD conditions also. Under SD conditions, the wild-type plants flowered at 47.5 ± 1.1 d and the ehd2-Tos17 mutants flowered at 132.7 ± 4.3 d. Under LD conditions, the wild-type plants flowered at 80.6 ± 3.4 d, but the ehd2-Tos17 mutants did not flower for more than 365 d (Fig. 6B), as was the case for the ehd2 mutants of cv Tohoku IL9 (Fig. 1A). The flowering time of the ehd2-Tos17 mutants was significantly delayed (by more than 85 d) compared with the wild-type plants under SD conditions. However, as in the case of the ehd2 mutants of cv Tohoku IL9, the ehd2-Tos17 mutants grown under SD conditions flowered dramatically earlier than those under LD conditions, suggesting that some unidentified gene other than Hd1 and Ehd1 can promote flowering under SD conditions in the ehd2 mutants (Fig. 6B).

We further examined the levels of Hd1 transcripts in the ehd2-Tos17 mutants and the wild-type plants. First, we analyzed the accumulation of Ehd2 and Ehd1 mRNAs to confirm that the late-flowering phenotype was caused by the Tos17-induced mutation of Ehd2 and the consequent reduced abundance of Ehd1 mRNA. The leaf samples were harvested 2 h after dawn from plants that had been grown for 4 weeks under SD and LD conditions and expression analysis was performed. Ehd2 and Ehd1 transcripts were abundant in the wild-type plants, but were nearly undetectable in the ehd2-Tos17 mutants (Fig. 6C). This result confirmed that the late flowering was caused by the ehd2 mutation. Next, we compared Hd1 mRNA expression between the ehd2-Tos17 mutants and the wild-type plants. The leaf samples were harvested 6 h after dusk under SD conditions or at 1.5 h after dusk under LD conditions because it has been reported that the accumulation of Hd1 mRNA increases after dusk (Izawa et al., 2002; Kojima et al., 2002). Contrary to our expectations, Hd1 mRNA decreased in the ehd2-Tos17 mutants under both photoperiodic conditions, although the degree of reduction was less dramatic than that for Ehd1 mRNA (Fig. 6C). In addition, no accumulation of Hd3a or RFT1 mRNAs was detected in the ehd2-Tos17 mutants under either photoperiodic condition (Fig. 6C). These results demonstrate that Ehd2 functions upstream of Ehd1. Because the reduction of Hd1 mRNA accumulation in the ehd2-Tos17 mutants was not severe compared with the reduction of Ehd1 mRNA (Fig. 6C), Hd1 appears to be functional in the ehd2-Tos17 mutants. However, we could not see clear differences in Ehd2 action between the cv Tohoku IL9 and cv Nipponbare backgrounds.

DISCUSSION

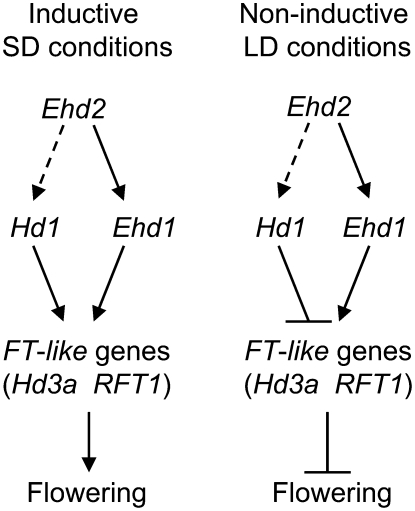

In this article, we cloned a rice ortholog of the maize ID1 gene, Ehd2, and demonstrated that it plays a critical role in the photoperiodic control of flowering in rice. Comparison of mRNA accumulation between the ehd2 mutants and wild-type plants (cv Tohoku IL9, carrying a deficient allele of Hd1) revealed that Ehd2 function is required for the expression of Ehd1 and of downstream FT-like genes under both SD and LD conditions (Figs. 4B and 5). Furthermore, expression analysis to compare Tos17-induced mutants of Ehd2 with wild-type plants (cv Nipponbare carrying a functional allele of Hd1) revealed that Ehd2 could up-regulate Hd1 (Fig. 6C). However, Hd1 may remain functional in the ehd2-Tos17 mutant because the reduction of Hd1 mRNA accumulation in the mutants was less severe than the reduction of Ehd1 mRNA (Fig. 6C). In this situation, flowering was severely delayed in the ehd2-Tos17 mutant under SD conditions (Fig. 6B). Therefore, Hd1 may not compensate for the late flowering caused by the ehd2-Tos17 mutation. Instead, Ehd2 and Hd1 may act additively because the ehd2-Tos17 mutants with a cv Nipponbare background flowered sooner than the ehd2 mutants with a cv Tohoku IL9 background. We cannot yet confirm this because we did not compare quantitative trait loci (QTL) between the two backgrounds. Note that either Hd1 or Ehd1 alone can promote rice flowering under SD conditions (Doi et al., 2004). On the basis of these results, we conclude that Ehd2 plays a pivotal role in the promotion of floral transition in rice under both inductive SD conditions and noninductive LD conditions (Fig. 7). It is noteworthy that an as-yet unidentified photoperiodic genetic pathway may operate in rice under SD conditions because both the ehd2 mutant and the ehd2-Tos17 mutant flowered under these conditions, but not under LD conditions, suggesting that the mutant plants became more sensitive to photoperiod than the wild-type plants.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the role of Ehd2 in the genetic control of flowering in rice. Pathways suggested by the results of this study are shown by dashed lines.

A diurnal change in Ehd2 mRNA accumulation was observed under both SD and LD conditions, although we did not define whether this pattern was controlled by a circadian clock or by an acute response to light signals (Fig. 4B). In addition, Ehd2 mRNA did not exhibit any photoperiodic responses because the expression of Ehd1 did not appear to be affected much by photoperiod under our study conditions.

During development, the accumulation of both Ehd1 and Hd3a mRNAs was observed at 2 weeks under SD conditions, although it was low level (Fig. 5). The mRNA accumulation of these genes might follow the rise of Ehd2 mRNA level and might be related to floral transition because, under SD conditions, the floral transition of wild-type plants (cv Tohoku IL9) should occur at about 3 weeks after germination. On the other hand, the level of Ehd1 and Hd3a mRNAs clearly reached a peak after the floral transition, although we do not have any knowledge about the increase in level of Ehd1 and Hd3a mRNAs after floral transition for now. Under LD conditions, the mRNA accumulation pattern of Ehd2 and the downstream genes showed a similar trend as under SD conditions with short delay.

Ehd2 is not the only gene that functions upstream of Ehd1. Recently, it has been reported that a type I MADS box gene, OsMADS51, also up-regulates Ehd1 and subsequently activates Hd3a mRNA expression (Kim et al., 2007). In osmads51 mutants, flowering time was delayed by about 2 weeks compared with wild-type plants under inductive SD conditions, but little change was observed under noninductive LD conditions (Kim et al., 2007). Therefore, it is likely that OsMADS51 preferentially promotes flowering under SD conditions (Kim et al., 2007). The microarray analysis in our study suggested that OsMADS51 is not downstream of Ehd2 because we observed no significant change in OsMADS51 expression between the ehd2 mutants and the wild-type plants. On the other hand, if OsMADS51 was upstream of Ehd2, the level of Hd1 transcripts would be altered in loss-of-function mutants of OsMADS51 because Ehd2 functions upstream of Hd1 (Fig. 6C). However, there was no apparent change in the abundance of Hd1 mRNA between the osmads51 mutants and the wild-type plants (Kim et al., 2007). Therefore, it is very likely that OsMADS51 follows a distinct pathway from that of Ehd2 and up-regulates Ehd1 mRNA expression. More recently, it was reported that Ghd7 is likely to down-regulate Ehd1 under LD conditions via a different pathway from the Ehd2 pathway (Xue et al., 2008). These findings demonstrate that Ehd1 expression is regulated by multiple pathways in the photoperiodic control of flowering.

In maize, two genes other than ID1 that play a role in flowering have been cloned and characterized thus far: delayed flowering1 (dlf1; Muszynski et al., 2006) and Vegetative to generative transition1 (Vgt1; Salvi et al., 2007). The dlf1 mutation has less effect on flowering than id1 mutations (Muszynski et al., 2006). DLF1 encodes a bZIP transcription factor that is homologous to Arabidopsis FD, suggesting that DLF1 interacts with a maize FT-like partner to induce flowering (Muszynski et al., 2006). However, the FT-like partner has not yet been shown in maize. Vgt1 had previously been known as a QTL for flowering time and was shown to be confined to an approximately 2-kb noncoding region by map-based cloning (Salvi et al., 2007). It functions as a cis-acting regulatory element positioned about 70 kb upstream of an APETALA2-like transcription factor (termed ZmRap2.7). The Vgt1 region is likely to have been evolutionarily conserved across maize, sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), and rice (Salvi et al., 2007).

The orthologous relationship between rice Ehd2 and maize ID1, which show a very high identity (82%) between their zinc finger domains, had been previously inferred by Colasanti et al. (2006) and supported by evidence of synteny conservation (Rice Chromosome 10 Sequencing Consortium, 2003). However, the function of the rice ortholog had not yet been demonstrated at the time of our study. Our study demonstrated that rice Ehd2 also acts as a flowering promoter. In addition, tissue-specific expression of orthologous genes in young leaves was likely to be similar (Fig. 3B; Colasanti et al., 1998, 2006; Wong and Colasanti, 2007). These results reveal that the functions of rice Ehd2 and maize ID1 are roughly conserved with respect to their role in flowering promotion and tissue-specific expression. On the other hand, it is likely that some functional differences between them are present. First, it has been reported that severe id1 mutants perturb the normal transition to floral development and produce aberrant inflorescences with vegetative characteristics (Galinat and Naylor, 1951; Colasanti et al., 1998). Such a morphological aberration was not observed in the ehd2 mutants in this study (Fig. 1, C and D). Certainly, the ehd2 mutants produced smaller inflorescences than those of the wild-type plants (Fig. 1D), but the production of small inflorescences is generally observed in rice plants that are grown under noninductive LD conditions and that consequently have a long vegetative duration. Therefore, we hypothesize that rice Ehd2 essentially acts as a flowering promoter. Maize ID1 may also be involved in floral development, but with a different form of genetic control from that in rice. The plant architectures of the two species differ in that rice develops bisexual flowers, whereas maize develops spatially separated unisexual male and female flowers (Bommert et al., 2005). Such a morphological difference should be caused by developmentally distinct patterns of genetic control. Therefore, species specificity of genetic control of floral development may result in the phenotype differences produced by mutations of rice Ehd2 and maize ID1. Identification of the genes involved in floral development downstream of both Ehd2 and ID1 is needed to clarify this issue.

The amount of ID1 mRNA and its protein showed no obvious diurnal changes even if the maize plants were subjected to different light and dark cycles (Wong and Colasanti, 2007). Microarray analysis revealed that none of the CO-like and FT-like genes showed significant differential expression between the wild-type plants and the id1 mutants, suggesting that ID1 expression is not under photoperiodic control (Coneva et al., 2007). Instead, Wong and Colasanti (2007) proposed that ID1 expression is developmentally regulated because ID1 mRNA was abundant in immature leaves, but less abundant in greening leaf tips and mature albino leaves. From those findings, Coneva et al. (2007) suggested that ID1 functions in an autonomous floral induction pathway that is distinct from the photoperiod-based induction pathway, although they did not completely rule out the possibility of involvement of the ID1 protein in the CO/FT regulatory pathway. Because the expression pattern is not altered by daylength, rice Ehd2 and maize ID1 appear to behave similarly. However, rice Ehd2 is certainly integrated in the photoperiod induction pathway (Figs. 4B, 5, and 6C), whereas maize ID1 may not be. We could not define any maize B-type response regulator (RR) as an Ehd1 ortholog from any database-registered protein. Maize ZmRR9 (AB062095) shares high identity between the receiver and Golden2, Arabidopsis RESPONSE REGULATOR, and Chlamydomonas regulatory protein of P-starvation acclimatization response DNA-binding domains of ZmRR9 and those of Ehd1 (43% and 65%, respectively), but other parts of ZmRR9 were not conserved in Ehd1 (Asakura et al., 2003; Ito and Kurata, 2006). Such functional differentiation in the downstream genes between rice Ehd2 and maize ID1 may affect their photoperiodic responses. Both rice and maize, which originated from low-latitude regions, are basically SD plants (Thomas and Vince-Prue, 1997). However, modern rice cultivars exhibit photoperiod sensitivity, whereas maize cultivars are considered to be essentially day neutral (Coneva et al., 2007). This question is intriguing because of its relevance in the process of divergence in the floral induction pathways of rice and maize.

In summary, Ehd2 promotes floral transition by up-regulating Ehd1 primarily and by up-regulating the downstream Hd3a and RFT1 genes (Fig. 7), demonstrating that Ehd2 is a key factor in the genetic network that controls photoperiodic flowering in rice. Like Ehd1, there is no obvious ortholog of rice Ehd2 or maize ID1 in Arabidopsis. Moreover, some functional differences are likely to be present even between the orthologous genes of rice and maize in their floral induction pathways. Further clarifying how these differences contribute to the control flowering time in rice, maize, and Arabidopsis will improve our understanding of the diversification of photoperiodic control of flowering in higher plants at a molecular level.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Two japonica rice (Oryza sativa) cv Tohoku IL9 and cv Nipponbare, were used as the wild-type controls; cv Tohoku IL9 is a near-isogenic derivative of the japonica cv Sasanishiki. The ehd2 mutant was identified in an M2 generation of γ-irradiated cv Tohoku IL. The indica cv Guang Lu Ai 4 was used for mapping of the ehd2 locus. A Tos17-induced mutant of Ehd2 was obtained from the National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences of Japan (Tos17 mutant panel project; http://tos.nias.affrc.go.jp/∼miyao/pub/tos17). Plants were grown in a controlled-growth cabinet (Especmic TGEH-9) under SD conditions (10 h light/14 h dark; 28°C for 12 h and 24°C for 12 h) or LD conditions (14.5 h light/9.5 h dark; 28°C for 12 h and 24°C for 12 h) at 60% relative humidity. Light was provided by metal halide lamps (300- to 1,000-nm spectrum, 500 μmol m−2 s−1). For evaluation under ND conditions, plants were also grown from mid-April in a paddy field in Tsukuba, Japan. The daylengths during vegetative growth were 13.1 h at germination (mid-April), 14.1 h at 30 d after germination (mid-May), 14.6 h at 60 d (mid-June), 14.4 h at 90 d (mid-July), 13.5 h at 120 d (mid-August), and 12.4 h at 150 d (mid-September).

Map-Based Cloning

To map the ehd2 locus, the ehd2 mutant was first crossed with the indica cv Guang Lu Ai 4 to obtain sufficient DNA marker polymorphisms and the resultant F1 population was backcrossed with cv Guang Lu Ai 4. We then performed bulked segregant analysis by pooling equal amounts of DNA from 10 BC1F2 plants with a late-flowering phenotype (homozygous for the recessive allele at ehd2) or 10 BC1F2 plants with a normal flowering phenotype (heterozygous or homozygous for the dominant Ehd2 allele). A total of 93 SSR markers, which were distributed evenly across all 12 chromosomes, were selected to examine SSR marker polymorphism between the late-flowering phenotype with the ehd2 mutant and the normal flowering phenotype in cv Guang Lu Ai 4. For the high-resolution mapping, the progeny (2,047 plants) of heterozygotes of the initial mapping population were used. To test the complementation of Ehd2, we cloned a 5.0-kb genomic fragment of cv Nipponbare, which was digested by XbaI and KpnI and transformed into the pPZP2H-lac binary vector (Fuse et al., 2001). The resultant plasmid was then introduced into the ehd2 mutant by means of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (Hiei et al., 1994). Homozygous T2 progeny derived from single-copy T0 transformants were grown under SD conditions and their flowering time was recorded. The structure of the mRNA of Ehd2 was determined by means of RACE using the Marathon cDNA amplification kit (CLONTECH).

Identification of the Tos17-Induced Mutant of Ehd2

To identify the Tos17-induced mutation of Ehd2, we extracted genomic DNA using a cetyltrimethylammonium bromide method (Murray and Thompson, 1980) from the selfed progeny of Ehd2 heterozygotes and used PCR analysis to examine the cosegregation of Tos17 with the late-flowering phenotype by genotyping with a Tos17-specific primer (5′-AGGAGGTTGCTTAGCAGTGAAACG-3′) in combination with two Ehd2-specific primers (5′-TTGTTCATGCCTGCAGGAAG-3′ and 5′-AATTTGCATTATGGCTTGATCTTC-3′). We identified plants that carried a homozygous insertion for Tos17 and cosegregated with the late-flowering phenotype (Supplemental Fig. S6). The sequence flanking the Tos17 insertion was determined by direct sequencing of the PCR products.

Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis of Gene Expression

Total RNA was extracted from leaves by using the SDS-phenol method (Shirzadegan et al., 1991). Total RNA (2.5 μg) was primed with the dT18 primer by using the first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Amersham Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed as previously described (Kojima et al. 2002). cDNA corresponding to 50 ng of total RNA was used as the template for each TaqMan PCR reaction (Applied Biosystems). At least three PCR reactions using the same templates were performed to obtain average values for the expression levels. The PCR conditions were 2 min at 50°C, then 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, and 1 min at 60°C. To quantify Ehd2 mRNA expression, we used the specific primers 5′-CGACAATAGCTCGATCGCC-3′ and 5′-AAGCCCGAAGCTGACACTGT-3′ and the probe 5′-CGATGTCATGGTGGCTGCAGGTG-3′. Hd1, Ehd1, Hd3a, RFT1, and UBQ mRNAs were quantified by using previously described primers and probes (Kojima et al., 2002 for Hd1, Hd3a, and UBQ; Doi et al. 2004 for Ehd1 and RFT1). For copy number standards, quantified fragments of cloned cDNA were used.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers AB359195, AB359196, AB359197, and AB359198.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Distribution of days to flowering under ND conditions in BC1F2 population (n = 109) from the cross between the ehd2 mutant and cv Guang Lu Ai 4.

Supplemental Figure S2. Alignment of deduced amino acid sequences of rice Ehd2 and maize ID1.

Supplemental Figure S3. Phylogenetic comparison of ID domain amino acid sequences from rice, maize, and Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Figure S4. Diurnal changes in levels of Hd1 transcripts under SD (10 h light/14 h dark) and LD (14.5 h light/9.5 h dark) conditions.

Supplemental Figure S5. Expression analyses of Os08g0200600 (NAM protein domain containing protein).

Supplemental Figure S6. Distribution of days to flowering under ND conditions in the selfed progeny (n = 48) of the Tos17-induced mutants heterozygous for Ehd2.

Supplemental Table S1. Genetic markers used in the delimitation of candidate genomic region of Ehd2.

Supplemental Table S2. Summary of microarray data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kazuhiko Sugimoto for valuable advice regarding the experimental procedures. We also thank Dr. Hirohiko Hirochika and Dr. Akio Miyao for the DNA pools used to screen the Tos17 lines, Ms. Meenu Gupta for screening the ehd2-Tos17 line, Dr. Yoshiaki Nagamura and Ms. Ritsuko Motoyama for performing the microarray analysis, Ms. Kazuko Ono for the Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, and Ms. Kanako Takeyama for technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (Integrated Research Project for Plant, Insect and Animal using Genome Technology [grant no. IP1001] and Genomics for Agricultural Innovation [grant no. GPN0001]).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Masahiro Yano (myano@nias.affrc.go.jp).

Some figures in this article are displayed in color online but in black and white in the print edition.

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

References

- Abe M, Kobayashi Y, Yamamoto S, Daimon Y, Yamaguchi A, Ikeda Y, Ichinoki H, Notaguchi M, Goto K, Araki T (2005) FD, a bZIP protein mediating signals from the floral pathway integrator FT at the shoot apex. Science 309 1052–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura Y, Hagino T, Ohta Y, Aoki K, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Deji A, Yamaya T, Sugiyama T, Sakakibara H (2003) Molecular characterization of His-Asp phosphorelay signaling factors in maize leaves: implications of the signal divergence by cytokinin-inducible response regulators in the cytosol and nuclei. Plant Mol Biol 52 331–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommert P, Satoh-Ngasawa N, Jackson D, Hirano HY (2005) Genetics and evolution of inflorescence and flower development in grasses. Plant Cell Physiol 46 69–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colasanti J, Tremblay R, Wong AYM, Coneva V, Kozaki A, Mable BK (2006) The maize INDETERMINATE1 flowering time regulator defines a highly conserved zinc finger protein family in higher plants. BMC Genomics 7 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colasanti J, Yuan Z, Sundaresan V (1998) The indeterminate gene encodes a zinc finger protein and regulates a leaf-generated signal required for the transition to flowering in maize. Cell 93 593–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coneva V, Zhu T, Colasanti J (2007) Expression differences between normal and indeterminate1 maize suggest downstream targets of ID1, a floral transition regulator in maize. J Exp Bot 58 3679–3693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier L, Vincent C, Jang S, Fornara F, Fan Q, Searle I, Giakountis A, Farrona S, Gissot L, Turnbull C, et al (2007) FT protein movement contributes to long-distance signaling in floral induction of Arabidopsis. Science 316 1030–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi K, Izawa T, Fuse T, Yamanouchi U, Kubo T, Shimatani Z, Yano M, Yoshimura A (2004) Ehd1, a B-type response regulator in rice, confers short-day promotion of flowering and controls FT-like gene expression independently of Hd1. Genes Dev 18 926–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuse T, Sasaki T, Yano M (2001) Ti-plasmid vectors useful for functional analysis of rice genes. Plant Biotechnol 18 219–222 [Google Scholar]

- Galinat WC, Naylor AW (1951) Relation of photoperiod to inflorescence proliferation in Zea mays L. Am J Bot 38 38–47 [Google Scholar]

- Hayama R, Yokoi S, Tamaki S, Yano M, Shimamoto K (2003) Adaptation of photoperiodic control pathways produces short-day flowering in rice. Nature 422 719–722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiei Y, Ohta S, Komari T, Kumashiro T (1994) Efficient transformation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) mediated by Agrobacterium and sequence analysis of the boundaries of the T-DNA. Plant J 6 271–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Kurata N (2006) Identification and characterization of cytokinin-signalling gene families in rice. Gene 382 57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh JI, Hasegawa A, Kitano H, Nagato Y (1998) A recessive heterochronic mutation, plastochron1, shortens the plastochron and elongates the vegetative phase in rice. Plant Cell 10 1511–1521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa T (2007) Adaptation of flowering-time by natural and artificial selection in Arabidopsis and rice. J Exp Bot 58 3091–3097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa T, Oikawa T, Sugiyama N, Tanisaka T, Yano M, Shimamoto K (2002) Phytochrome mediates the external light signal to repress FT orthologs in photoperiodic flowering of rice. Genes Dev 16 2006–2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardailsky I, Shukla VK, Ahn JH, Dagenais N, Christensen SK, Nguyen JT, Chory J, Harrison MJ, Weigel D (1999) Activation tagging of the floral inducer FT. Science 286 1962–1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SL, Lee S, Kim HJ, Nam HG, An G (2007) OsMADS51 is a short-day flowering promoter upstream of Ehd1, OsMADS14, and Hd3a. Plant Physiol 145 1484–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y, Kaya H, Goto K, Iwabuchi M, Araki T (1999) A pair of related genes with antagonistic roles in mediating flowering signals. Science 286 1960–1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y, Weigel D (2008) Move on up, it's time for change—mobile signals controlling photoperiod-dependent flowering. Genes Dev 21 2371–2384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima S, Takahashi Y, Kobayashi Y, Monna L, Sasaki T, Araki T, Yano M (2002) Hd3a, a rice ortholog of the Arabidopsis FT gene, promotes transition to flowering downstream of Hd1 under short-day conditions. Plant Cell Physiol 43 1096–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiya R, Ikegami A, Tamaki S, Yokoi S, Shimamoto K (2008) Hd3a and RFT1 are essential for flowering in rice. Development 135 767–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M, Alonso-Blanco C, Peeters AJM, Soppe W (1998) Genetic control of flowering time in Arabidopsis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 49 345–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozaki A, Hake S, Colasanti J (2004) The maize ID1 flowering time regulator is a zinc finger protein with novel DNA binding properties. Nucleic Acids Res 32 1710–1720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray MG, Thompson WF (1980) Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 8 4321–4325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muszynski MG, Dam T, Li B, Shirbroun DM, Hou Z, Bruggemann E, Archibald R, Ananiev EV, Danilevskaya ON (2006) delayed flowering 1 encodes a basic leucine zipper protein that mediates floral inductive signals at the shoot apex in maize. Plant Physiol 142 1523–1536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvi S, Sponza G, Morgante M, Tomes D, Niu X, Fengler KA, Meeley R, Ananiev EV, Svitashev S, Bruggemann E, et al (2007) Conserved noncoding genomic sequences associated with a flowering-time quantitative trait locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104 11376–11381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samach A, Onouchi H, Gold SE, Ditta GS, Schwarz-Sommer Z, Yanofsky MF, Coupland G (2000) Distinct roles of CONSTANS target genes in reproductive development of Arabidopsis. Science 288 1613–1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa M, Nusinow DA, Kay SA, Imaizumi T (2007) FKF1 and GIGANTEA complex formation is required for day-length measurement in Arabidopsis. Science 318 261–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirzadegan M, Christie P, Seemann JR (1991) An efficient method for isolation of RNA from tissue cultured plant cells. Nucleic Acids Res 19 6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton WR (1946) Inheritance of indeterminate growth in maize. J Hered 37 61–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Lopez P, Wheatley K, Robson F, Onouchi H, Valverde F, Coupland G (2001) CONSTANS mediates between the circadian clock and the control of flowering in Arabidopsis. Nature 410 1116–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaki S, Matsuo S, Wong HL, Yokoi S, Shimamoto K (2007) Hd3a protein is a mobile flowering signal in rice. Science 316 1033–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice Chromosome 10 Sequencing Consortium (2003) In-depth view of structure, activity, and evolution of rice chromosome 10. Science 300 1566–1569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas B, Vince-Prue D (1997) Photoperiodism in Plants, Ed 2. Academic Press, San Diego

- Turck F, Fornara F, Coupland G (2008) Regulation and identity of florigen: FLOWERING LOCUS T moves center stage. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59 573–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde F, Mouradov A, Soppe W, Ravenscroft D, Samach, A, Coupland G (2004) Photoreceptor regulation of CONSTANS protein in photoperiodic flowering. Science 303 1003–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigge PA, Kim MC, Jaeger KE, Busch W, Schmid M, Lohmann JU, Weigel D (2005) Integration of spatial and temporal information during floral induction in Arabidopsis. Science 309 1056–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong AYM, Colasanti J (2007) Maize floral regulator INDETERMINATE1 is localized to developing leaves and is not altered by light or the sink/source transition. J Exp Bot 58 403–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W, Xing Y, Weng X, Zhao Y, Tang W, Wang L, Zhou H, Yu S, Xu C, Li X, et al (2008) Natural variation in Ghd7 is an important regulator of heading date and yield potential in rice. Nat Genet 40 761–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano M, Katayose Y, Ashikari M, Yamanouchi U, Monna L, Fuse T, Baba T, Yamamoto K, Umehara Y, Nagamura Y, et al (2000) Hd1, a major photoperiod sensitivity quantitative trait locus in rice, is closely related to the Arabidopsis flowering time gene CONSTANS. Plant Cell 12 2473–2483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano M, Kojima S, Takahashi Y, Lin H, Sasaki T (2001) Genetic control of flowering time in rice, a short-day plant. Plant Physiol 127 1425–1429 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovsky MJ, Kay SA (2002) Molecular basis of seasonal time measurement in Arabidopsis. Nature 419 308–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.