Abstract

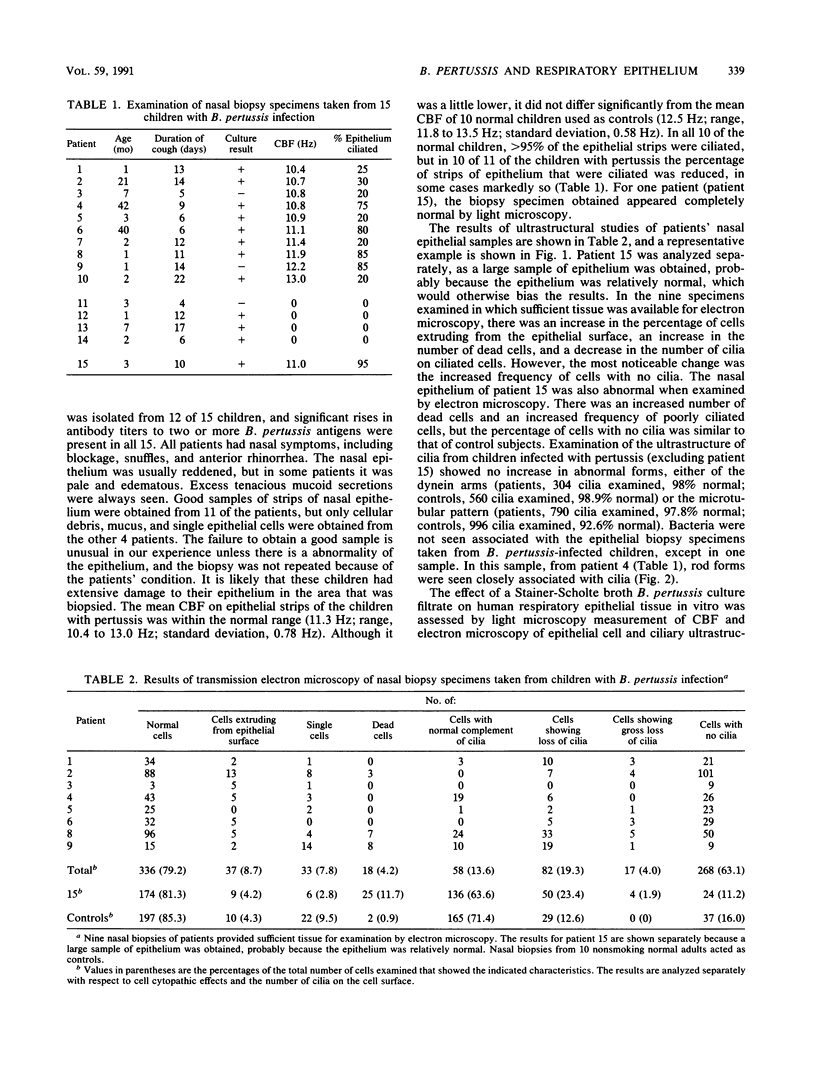

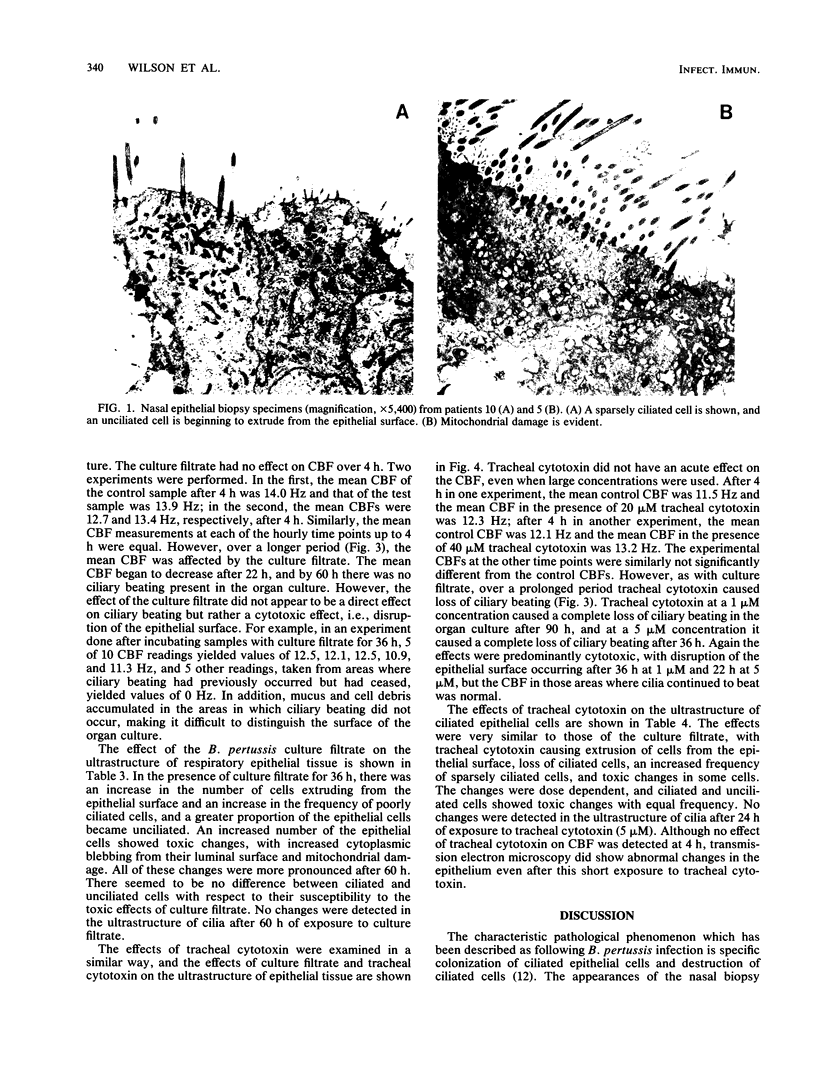

Bordetella pertussis infection probably involves attachment to and destruction of ciliated epithelial cells, but most previous studies have used animal tissue. During an epidemic, nasal epithelial biopsy specimens of 15 children (aged 1 month to 3 1/2 years) with whooping cough were examined for ciliary beat frequency, percent ciliation of the epithelium, and ciliary and epithelial cell ultrastructure. In addition, the in vitro effects of filtrates from a 24-h broth culture and of tracheal cytotoxin derived from B. pertussis on human nasal tissue organ culture were measured. B. pertussis was cultured from nasal swabs from 12 children. The mean ciliary beat frequency of their nasal biopsy specimens, 11.3 Hz (range, 10.4 to 13.0 Hz) was similar to that found in biopsy specimens from 10 normal children (mean, 12.5 Hz; range, 11.8 to 13.5 Hz). The abnormalities of the epithelium observed in 14 of 15 patients were a reduction in the number of ciliated cells, an increase in the number of cells with sparse ciliation, an increase in the number of dead cells, and extrusion of cells from the epithelial surface. In vitro, neither culture filtrate nor tracheal cytotoxin had any acute effect on ciliary function, but culture filtrate and tracheal cytotoxin (1 and 5 microM, respectively) caused extrusion of cells from the epithelial surface of turbinate tissue, loss of ciliated cells, an increased frequency of sparsely ciliated cells, and toxic changes in some cells. These changes were dose dependent and progressive, and between 36 and 90 h ciliary beating ceased. The observations made with patient tissue confirm that B. pertussis infection damages ciliated epithelium, and the in vitro experiments suggest that tracheal cytotoxin may be responsible for the abnormalities observed in vivo.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Coleman K. D., Wetterlow L. H. Use of implantable intraperitoneal diffusion chambers to study Bordetella pertussis pathogenesis: growth and toxin production in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1986 Jul;154(1):33–39. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson B. T., Cho H. L., Herwaldt L. A., Goldman W. E. Biological activities and chemical composition of purified tracheal cytotoxin of Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1989 Jul;57(7):2223–2229. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.7.2223-2229.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson B. T., Tyler A. N., Goldman W. E. Primary structure of the peptidoglycan-derived tracheal cytotoxin of Bordetella pertussis. Biochemistry. 1989 Feb 21;28(4):1744–1749. doi: 10.1021/bi00430a048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine P. E., Clarkson J. A. Reflections on the efficacy of pertussis vaccines. Rev Infect Dis. 1987 Sep-Oct;9(5):866–883. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.5.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman W. E., Herwaldt L. A. Bordetella pertussis tracheal cytotoxin. Dev Biol Stand. 1985;61:103–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman W. E., Klapper D. G., Baseman J. B. Detection, isolation, and analysis of a released Bordetella pertussis product toxic to cultured tracheal cells. Infect Immun. 1982 May;36(2):782–794. doi: 10.1128/iai.36.2.782-794.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura A., Mountzouros K. T., Relman D. A., Falkow S., Cowell J. L. Bordetella pertussis filamentous hemagglutinin: evaluation as a protective antigen and colonization factor in a mouse respiratory infection model. Infect Immun. 1990 Jan;58(1):7–16. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.1.7-16.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melly M. A., McGee Z. A., Rosenthal R. S. Ability of monomeric peptidoglycan fragments from Neisseria gonorrhoeae to damage human fallopian-tube mucosa. J Infect Dis. 1984 Mar;149(3):378–386. doi: 10.1093/infdis/149.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muse K. E., Collier A. M., Baseman J. B. Scanning electron microscopic study of hamster tracheal organ cultures infected with Bordetella pertussis. J Infect Dis. 1977 Dec;136(6):768–777. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.6.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opremcak L. B., Rheins M. S. Scanning electron microscopy of mouse ciliated oviduct and tracheal epithelium infected in vitro with Bordetella pertussis. Can J Microbiol. 1983 Apr;29(4):415–420. doi: 10.1139/m83-067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan J., Lowe F. Enrichment medium for the isolation of Bordetella. J Clin Microbiol. 1977 Sep;6(3):303–309. doi: 10.1128/jcm.6.3.303-309.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relman D. A., Domenighini M., Tuomanen E., Rappuoli R., Falkow S. Filamentous hemagglutinin of Bordetella pertussis: nucleotide sequence and crucial role in adherence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Apr;86(8):2637–2641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R. S., Nogami W., Cookson B. T., Goldman W. E., Folkening W. J. Major fragment of soluble peptidoglycan released from growing Bordetella pertussis is tracheal cytotoxin. Infect Immun. 1987 Sep;55(9):2117–2120. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2117-2120.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutland J., Cole P. J. Non-invasive sampling of nasal cilia for measurement of beat frequency and study of ultrastructure. Lancet. 1980 Sep 13;2(8194):564–565. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91995-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stainer D. W., Scholte M. J. A simple chemically defined medium for the production of phase I Bordetella pertussis. J Gen Microbiol. 1970 Oct;63(2):211–220. doi: 10.1099/00221287-63-2-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinfort C., Wilson R., Mitchell T., Feldman C., Rutman A., Todd H., Sykes D., Walker J., Saunders K., Andrew P. W. Effect of Streptococcus pneumoniae on human respiratory epithelium in vitro. Infect Immun. 1989 Jul;57(7):2006–2013. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.7.2006-2013.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M. G., Redhead K., Lambert H. P. Human serum antibody responses to Bordetella pertussis infection and pertussis vaccination. J Infect Dis. 1989 Feb;159(2):211–218. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomanen E., Towbin H., Rosenfelder G., Braun D., Larson G., Hansson G. C., Hill R. Receptor analogs and monoclonal antibodies that inhibit adherence of Bordetella pertussis to human ciliated respiratory epithelial cells. J Exp Med. 1988 Jul 1;168(1):267–277. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.1.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urisu A., Cowell J. L., Manclark C. R. Filamentous hemagglutinin has a major role in mediating adherence of Bordetella pertussis to human WiDr cells. Infect Immun. 1986 Jun;52(3):695–701. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.3.695-701.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss A. A., Hewlett E. L. Virulence factors of Bordetella pertussis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1986;40:661–686. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.40.100186.003305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R., Alton E., Rutman A., Higgins P., Al Nakib W., Geddes D. M., Tyrrell D. A., Cole P. J. Upper respiratory tract viral infection and mucociliary clearance. Eur J Respir Dis. 1987 May;70(5):272–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R., Pitt T., Taylor G., Watson D., MacDermot J., Sykes D., Roberts D., Cole P. Pyocyanin and 1-hydroxyphenazine produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa inhibit the beating of human respiratory cilia in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1987 Jan;79(1):221–229. doi: 10.1172/JCI112787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. Secondary ciliary dysfunction. Clin Sci (Lond) 1988 Aug;75(2):113–120. doi: 10.1042/cs0750113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]