Abstract

As commonly encountered, pituitary adenomas are invariably benign. We therefore studied protective pituitary proliferative mechanisms. Pituitary tumor transforming gene (Pttg) deletion results in pituitary p21 induction and abrogates tumor development in Rb+/−Pttg−/− mice. p21 disruption restores attenuated Rb+/−Pttg−/− pituitary proliferation rates and enables high penetrance of pituitary, but not thyroid, tumor growth in triple mutant animals (88% of Rb+/− and 72% of Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− vs. 30% of Rb+/−Pttg−/− mice developed pituitary tumors, P < 0.001). p21 deletion also accelerated S-phase entry and enhanced transformation rates in triple mutant MEFs. Intranuclear p21 accumulates in Pttg-null aneuploid GH-secreting cells, and GH3 rat pituitary tumor cells overexpressing PTTG also exhibited increased levels of mRNA for both p21 (18-fold, P < 0.01) and ATM (9-fold, P < 0.01). PTTG is abundantly expressed in human pituitary tumors, and in 23 of 26 GH-producing pituitary adenomas with high PTTG levels, senescence was evidenced by increased p21 and SA-β-galactosidase. Thus, either deletion or overexpression of Pttg promotes pituitary cell aneuploidy and p53/p21-dependent senescence, particularly in GH-secreting cells. Aneuploid pituitary cell p21 may constrain pituitary tumor growth, thus accounting for the very low incidence of pituitary carcinomas.

Keywords: acromegaly, nonfunctioning adenoma, pituitary adenoma, PTTG

Perturbed cell proliferation subserves pituitary trophic disorders that lead to pituitary hypoplasia, hyperplasia, or adenoma formation (1, 2). These conditions, associated with either hormonal hyposecretion or hypersecretion, are characterized by several unique features, including reversibility as exemplified by pregnancy-associated hyperplasia (3), transcription-factor- or aging-associated hypoplasia, and a compelling resistance to adenomatous malignant transformation. Pituitary tumors, commonly encountered as intracranial neoplasms, are invariably benign, but cause significant morbidity through mass effects and/or the inappropriate secretion of pituitary hormones (4, 5). Changes leading to pituitary tumorigenesis involve both intrinsic pituicyte dysfunction and altered availability of paracrine or endocrine factors that regulate hormone secretion and cell growth (6–9). Mitotic activity is relatively low, even in aggressive pituitary adenomas, in contrast to tumors arising from more rapidly replicating tissues (2). To gain insight into the unique pathogenesis of disordered pituitary growth, we examined mechanisms subserving pituitary cell proliferation.

Pituitary tumor transforming gene (Pttg) (10), a mammalian securin that facilitates sister-chromatid separation during metaphase (11), exhibits oncogene properties as overexpression causes cell transformation, induces aneuploidy (12, 13), and promotes tumor formation (14). PTTG also regulates transcription of several genes (15), including those encoding G1-S-phase proteins (16, 17). Pttg is overexpressed in pituitary tumors (18), and abundance of the protein correlates with pituitary, thyroid, colon, and uterine tumor invasiveness (19). Equilibrium of intracellular PTTG levels is important for maintaining chromosomal stability, as both high or low Pttg expression induce genetic instability (20, 21), and cells overexpressing Pttg (22) and Pttg-null cells (23) both exhibit aneuploidy. Enhanced chromosomal rearrangements and chromatid breaks are observed after DNA damage in Pttg−/− HCT116 cells, highlighting the securin requirement for the maintenance of chromosomal stability after genotoxic stress (24).

Pituitary-directed transgenic Pttg overexpression results in focal pituitary hyperplasia and small but functional adenoma formation (14). In contrast, mice lacking Pttg exhibit selective endocrine cell hypoplasia (25). The permissive role of PTTG for pituitary adenoma development was further confirmed by the observation that Pttg deletion from the Rb+/− background results in p53/p21 senescence pathway activation, associated with pituitary hypoplasia and attenuated adenoma formation (23, 26).

p21Cip/Kip (p21), a transcriptional target of p53, is induced in response to a spectrum of cellular stresses and acts to constrain the cell cycle. p21 may also be induced as a result of DNA damage or oncogene expression, triggering irreversible cell cycle arrest (i.e., senescence), which facilitates tumor growth arrest (27–30). Mechanisms effecting cell senescence act to buffer the cell from pro-proliferative signals, and in vivo senescent markers are predominantly expressed in benign but not in malignant lesions (31). p21 may mediate either suppression or promotion of cell proliferation depending on intracellular localization of the protein (32), and intranuclear p21 acts to arrest proliferation of unstable or aneuploid cells (33, 34). Activating oncogene functions may also switch to growth restraint, depending on the cellular genetic context and functional p21 status (35).

To delineate mechanisms underlying the protective role of p21 in pituitary tumor growth, we generated triple mutant Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− mice and show that p21 deficiency rescues pituitary cell proliferation and restores abrogated pituitary tumor formation in Rb+/−Pttg−/− mice. Paradoxically, p21 is also induced in Pttg-transfected GH3 pituitary cells and in human GH-secreting pituitary adenomas exhibiting high PTTG levels. The results indicate that both Pttg deletion and Pttg overexpression trigger pituitary cell aneuploidy and p21 induction. High pituitary p21 levels appear to promote senescence and restrain pituitary tumor growth and may underlie the failure of invariably benign pituitary tumors to progress to true malignancy.

Results

p21 Deletion Restores Pituitary Tumor Development in Rb+/−Pttg−/− Mice.

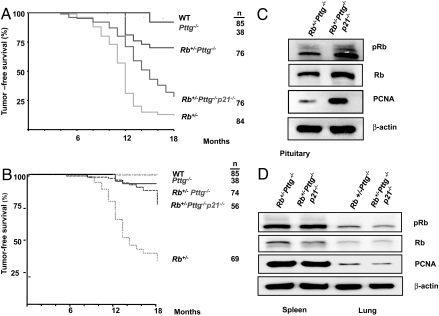

We hypothesized that high pituitary p21 contributed to the protective effect of Pttg deletion on pituitary tumor development in Rb+/− mice (23). We therefore deleted p21 from the Rb+/−Pttg−/− background and generated triple mutant Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− mice. Spontaneous WT pituitary tumors were observed in 6 of 85 animals (5%) starting at 9 months of age. Of 38 Rb+/+Pttg−/− mice, 3 (8%) harbored pituitary tumors by 18 months. Rb heterozygous mice die mostly from pituitary tumors at 8–15 months depending on their genetic backgrounds (36, 37). Mice developed pituitary tumors starting from 4 months of age, and by 18 months, 74 of 84 (88%) Rb+/−Pttg+/+ mice harbored confirmed tumors. Pttg deletion delayed the appearance of pituitary tumors; of 78 double mutant Rb+/−Pttg−/− mice, only 30% harbored tumors by 18 months. p21 removal from the Rb+/−Pttg−/− background (triple mutant Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− mice) restored tumor formation almost to levels observed in single mutant Rb+/− mice; of 76 such triple mutant mice, 63 (72%) developed pituitary tumors (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

p21 deletion from the Rb+/−Pttg−/− background restores pituitary but not thyroid tumor development in mice. (A) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (log-rank test) of the time of death with evidence of pituitary tumor showed significant differences between Rb+/−Pttg−/− and Rb+/−Pttg+/+ (P < 0.001), between Rb+/−Pttg−/− and Rb+/+Pttg−/− (P < 0.05), and between a Rb+/−Pttg−/− and Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− mice (P = 0.007). (B) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (log-rank test) with evidence of thyroid tumors in the different genotypes showed significant differences between Rb+/−Pttg−/− and Rb+/−Pttg+/+ (P < 0.001), and between Rb+/−Pttg+/+ and Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− mice (P < 0.001). No differences were observed between Rb+/−Pttg−/− and Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− mice. n, number of animals killed. Western blot analysis of proliferation markers in (C) pituitary and (D) spleen and lung lysates derived from Rb+/− Pttg−/− and Rb+/− Pttg−/− p21−/− mice.

Rb+/−Pttg+/+, Rb+/−Pttg−/−, and Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− mice developed intermediate and anterior lobe tumors, with some animals developing tumors in both pituitary sites. Fewer triple mutant animals simultaneously developed both intermediate and anterior lobe tumors (supporting information (SI) Fig. S1).

Rb+/− mice also spontaneously develop medullary thyroid (C-cell) carcinoma (36). Sixty-three percent of Rb+/− mice (44 of 69 animals) developed medullary C-cell carcinoma by 18 months. Although deletion of Pttg from the Rb+/− background abrogated thyroid tumor development and the incidence of tumors dropped from 57 to 7% in Rb+/−Pttg−/− animals (5 of 74 mice), p21 ablation did not restore thyroid tumor development in Rb+/−Pttg−/− mice. Of 56 Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− animals, only 9 (16%) developed medullary thyroid carcinoma (Fig. 1B).

p21 Deletion Enhances Pituitary Cell Proliferation.

p21 deletion from the Rb+/−Pttg−/− background enhances pituitary Rb levels and Rb phosphorylation at Ser-807/811, a residue preferentially phosphorylated by cyclin D-Cdk2 complexes (38) (Fig. 1C), and specifically increases pituitary PCNA levels in triple mutant Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− mice. In contrast, spleen and lung Rb, phosphoRb, and PCNA levels were unchanged (Fig. 1D).

p21 Expression in the Pttg-Null Pituitary Gland.

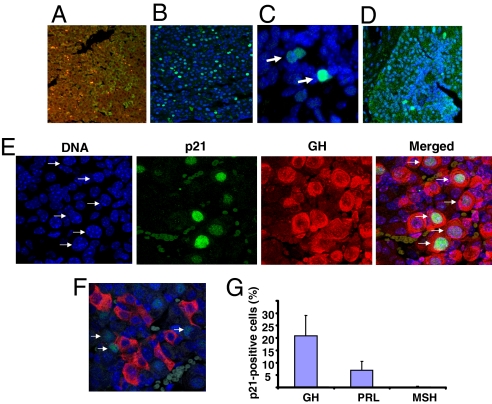

Growth inhibiting p21 activity correlates with nuclear localization of the protein (32). Strong intranuclear p21 expression was evident in Pttg−/− anterior and, to a much lesser extent, in intermediate lobe pituitary cells, but not in WT pituitary nuclei (Fig. 2 A–D). Importantly, multiple GH-secreting cells exhibit aneuploidy evidenced by the presence of macronuclei, and these readily expressed p21 (Fig. 2E). Of 1,078 oddly shaped aneuploid nuclei, 452 cells (≈42%) expressed high to moderate levels of intranuclear p21, whereas intranuclear p21 was not detected in TSH-, FSH-, LH- (data not shown and ref. 23), or ACTH-secreting Pttg−/− cells (Fig. 2F). Accordingly, 20% of GH-producing cells, ≈7% of PRL-producing cells, and 1.5% of MSH-producing cells coexpressed p21 (Fig. 2G).

Fig. 2.

Pituitary p21 expression. Fluorescence immunohistochemistry of p21 expression in WT (A) and Pttg−/− (B) pituitary glands. High resolution (×100) confocal image shows intranuclear p21 expression in Pttg−/− pituitary anterior (C) and intermediate (D) lobes. Paraffin slides were labeled with p21 antibody (green). Here and below slides were counterstained with DNA-specific dye ToPro3 (blue). (E) Pttg deletion evokes aneuploidy and enhances p21 expression in GH-producing pituitary cells. Confocal image of Pttg-null pituitary tissue labeled with p21 antibody (green) and GH- antibody (red). (F) The same as E but stained with ACTH antibody (red). In E and F, arrows indicate aneuploid nuclei expressing p21. (G) Percent of hormone-producing cells coexpressing intra-nuclear p21 in Pttg−/− glands.

Pttg-Null MEFs Exhibit Chromosomal Instability, DNA Damage, and p21-Induced Senescence.

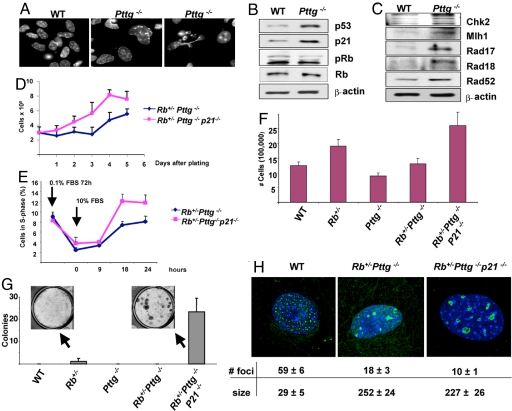

We tested mechanisms underlying p21-mediated pituitary senescence, using mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) prepared from 13.5 embryonic day embryos. We first tested whether DNA damage-associated senescence underlies the restraining effect of Pttg deletion on cell growth. First passage Pttg−/− but not WT cells exhibit genetic instability, with macronuclei, micronuclei, and bizarre-looking nuclei, all signs of aneuploidy (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

(A–C) Pttg−/− MEFs exhibit abnormal nuclear morphology, DNA damage, and activation of the p53/p21 senescence pathway. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of 1st passage WT and Pttg−/− MEFs. (B) Western blot analysis of p53/p21 senescence pathway markers in 10th passage MEFs. (C) Western blot analysis of DNA damage/repair proteins. Experiments were repeated 3 times with similar results, and representative blots are shown. (D–F) p21 deletion results in increased cell proliferation, accelerated G1-S phase transition, and enhanced transformation. (D)12th passage MEFs (3 × 105) were plated in duplicate 10-cm dishes and cells counted daily for 5 days. (E) 8th passage MEFs were synchronized in 0.1% FBS for 72 h and then cultured in 10% FBS. At the indicated times, duplicate samples were pulsed with BrdU for 30 min and analyzed by flow cytometry and S-phase cells were identified by staining with BrdU antibodies. (F) Proliferation of 12th passage MEFs from 5 experimental genotypes. In D–F, the cell number at each time-point represents the average of duplicate plates ± range. These experiments were performed with 2 independent MEF preparations with similar results, and a single experiment is depicted. (G) 4th passage MEFs derived from the indicated genotypes were infected with retrovirus encoding Ras+T-Ag and cultured in 6-well plates in triplicate for 21 days, and the number of colonies per well was counted. Numbers of colonies are expressed as mean ± SE of 3 independent MEF preparations. (H) γ-foci in 10th passage MEF nuclei. Depicted are single representative high-resolution confocal images of asynchronous and untreated mouse MEFs fixed and labeled with anti γ-H2AX antibody. Foci were counted and measured in 30 to 40 nuclei of each genotype, and focus number and size were determined by using ImageJ Software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij).

Pttg deletion resulted in enhanced p53 and p21 expression with no changes in total Rb, but decreased Rb phosphorylation, reflective of decreased Pttg−/− MEF proliferation capacity (Fig. 3B). Levels of Chk2 kinase, a critical checkpoint for cellular responses to DNA damage (39), were increased in Pttg-null MEFs, and further evidence for DNA damage was observed by up-regulated DNA repair proteins including Rad17, Rad18, Rad52, and Mlh1 (Fig. 3B). Thus, Pttg-deficient MEFs exhibit p21-dependent senescent features similar to those observed in Pttg-null pituitary tissues (23).

p21 Deletion Increases Growth and Transformation of Rb+/−Pttg−/− MEFs.

To assess the role of p21 in restraining tumorigenic properties of Rb+/−Pttg−/− cells, we examined effects of p21 disruption on MEF growth and transformation potential. For these experiments MEFs were derived from WT, Pttg−/−, Rb+/−, and Rb+/−Pttg−/− genotypes with and without p21 deletion from embryos obtained from intercross-breeding of triply mutant Rb+/−Pttg+/−p21+/−mice. Growth properties of fibroblasts did not differ for up to 12 passages, at which time Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− MEFs continue to grow while Rb+/−Pttg−/− cell growth was attenuated (Fig. 3 F and D).

To further determine a rate-limiting p21 function in the transition between quiescence and proliferation, we compared cell cycle entry of Rb+/−Pttg−/− and Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− quiescent 8th passage MEFs. Cells grown in 0.1% FBS for 72 h were stimulated by the addition of 10% FBS. Flow cytometry of cells pulsed with BrdU demonstrated that by 18 h more triple mutant Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− MEFs began to enter S-phase, whereas Rb+/−Pttg−/− MEFs lagged. Thus, the absence of p21 accelerates G0-S transition (Fig. 3E).

To test the effects of p21 deletion on cell transformation, MEFs were infected with retrovirus bearing Ras+T-Ag oncogenes. Rb+/− MEFs were readily transformed and exhibited enhanced cell growth and small colony formation. However, Rb+/−Pttg−/− MEFs did not form colonies consistent with a protective effect of Pttg deletion on cell transformation. Deletion of p21 enhanced proliferation while markedly increasing Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− MEF colony number and size (Fig. 3G).

Accumulation of γ-H2AX foci (γ –foci) in cells is reflective of double-strand DNA breaks (40) and γ-focus size depends on the severity of DNA damage. In agreement with others (41), a multitude of small foci were observed in 8th passage WT MEFs. The number of foci were decreased with markedly increased Rb+/−Pttg−/− and Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− MEF focus size, confirming accumulation of DNA damage in these cells. Foci number and size were similar in the 2 genotypes (Fig. 3H).

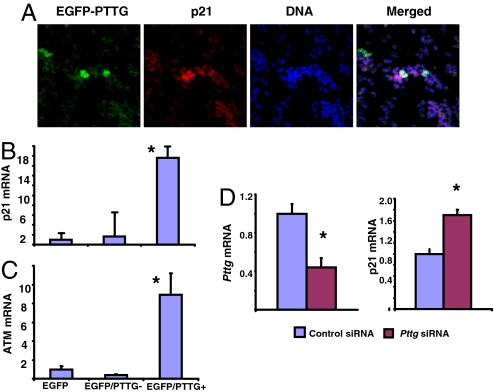

p21 Is Induced in GH3 Cells Overexpressing Pttg.

Aneuploidy induces cellular p21 levels (33, 34), and pituitary aneuploidy caused by Pttg deletion resulted in p21 induction mostly in GH-producing pituitary cells (Fig. 2E). We therefore tested effects of Pttg overexpression and silencing on pituitary cell p21 levels. We transiently transfected rat GH3 pituitary cells with plasmids expressing EGFP-PTTG, and immunocytochemistry showed enhanced p21 protein expression in these cells as compared with vector-transfected cells (Fig. 4A). Transfected cells were sorted by flow cytometry, and increased p21 mRNA levels were observed in EGFP-PTTG-positive GH3 (Fig. 4B). To confirm the aneuploid state and DNA damage in these cells, we measured the protein kinase mutated in ataxia telangiectasia (ATM), essential in sensing aneuploidy and DNA damage. ATM and p21 cooperate to impede aneuploidy and maintain chromosomal stability (33). In EGFP-PTTG-positive GH3 cells, ATM mRNA levels were induced 9-fold as compared with EGFP-only transfected cells (Fig. 4C). Silencing of Pttg in GH3 cells with Pttg siRNA also enhanced p21 mRNA levels (Fig. 4D), thus confirming our in vivo observation showing p21 up-regulation in the Pttg-null pituitary gland.

Fig. 4.

Both Pttg overexpression and silencing induces p21 in GH3 cells. (A) Confocal image of double fluorescence immunohistochemistry of rat GH-producing GH3 cells transfected with EGFP or EGFP-PTTG. Cells were fixed, labeled with EGFP antibody (green), p21 antibody (red). Cells coexpressing EGFP-PTTG and p21 appeared white. (B and C) Pttg overexpression induced p21 mRNA and ATM mRNA levels in GH3 cells. Cells were transfected with plasmids expressing EGFP or EGFP-PTTG and sorted by flow cytometry, and real-time PCR of p21 mRNA and ATM mRNA was performed. (D) Pttg silencing by Pttg siRNA induces p21 mRNA levels detected by real-time PCR. Values are expressed as mean ± SE of triplicate measurements for each experimental group. All experiments were repeated twice, and representative experiments are shown. *, P < 0.05 vs. control.

p21 Is Induced in Human Pituitary Tumors.

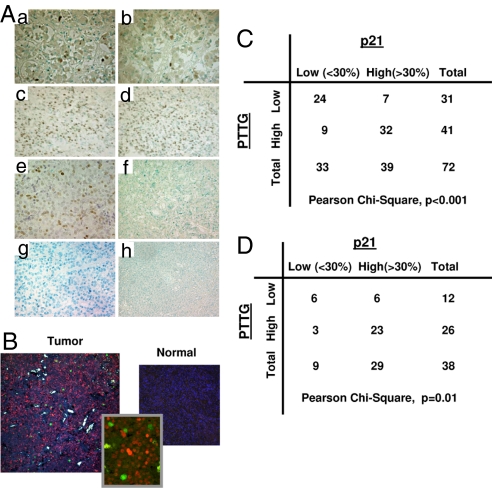

Seventy-nine human pituitary adenomas of various phenotypes, and seven normal pituitaries were analyzed for p21 expression. Normal pituitary tissues exhibit weak p21 immunoreactivity. In nonsecreting pituitary oncocytomas (21 samples) and null cell adenomas (7 samples) p21 immunoreactivity was not detected. In ACTH-producing tumors (8 samples), 3 were weakly positive and 5 were negative for p21. Of 5 gonadotropin-producing tumors, 1 was strongly positive, 1 weakly positive, and 3 were negative. However, in GH-producing adenomas (38 samples), 29 tested strongly positive and 9 weakly positive for p21 immunoreactivity. In contrast, p21 was not detected in 4 human GH-producing pituitary carcinomas, nor in high grade human breast carcinoma specimens (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

p21 is induced in human GH-producing pituitary adenomas. (A) (a–e) Immunohistochemistry of pituitary adenoma sections stained for p21 (brown). (f) Normal pituitary. (g) Breast carcinoma. (h) Pituitary carcinoma. (B) Confocal image of fluorescence immunohistochemistry for p21 and PTTG expression. Specimen was labeled with p21 antibody (red) and PTTG antibody (green). (C and D) Reciprocal p21 and PTTG expression in all pituitary tumor types (C) and in GH-secreting adenomas (D).

Seventy-two pituitary adenomas of various phenotypes were analyzed for both p21 and PTTG expression, and in 56 such tumors strong positive correlation was observed between PTTG and p21 expression (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5 B and C). Twenty-three of twenty-six GH-producing pituitary adenomas (88%) express both high p21 and PTTG levels (P = 0.025) (Fig. 5D).

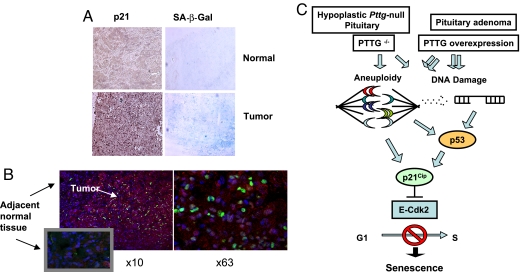

GH-secreting pituitary adenomas expressed markers of senescence. Senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity (SA-β-gal) (42) was analyzed in cryosections, and β-galactosidase protein levels in paraffin sections of surgically removed normal pituitary tissue and in GH-secreting adenomas. Levels of β-galactosidase protein correlate positively with its enzymatic activity (43). Unlike nontumorous pituitary tissue, GH-secreting adenomas were strongly positive for this senescence marker. Tumors with high levels of SA-β-gal activity express high p21 (Fig. 6A). To confirm that p21 is expressed in senescent cells, we double-labeled GH-secreting adenoma specimens with antibodies to both p21 and β-galactosidase. All 15 p21-expressing adenomas examined were positive for β-galactosidase, and p21 colocalized with β-galactosidase in adenomatose tissue, whereas adjacent normal tissue did not express either of these proteins (Fig. 6B and Fig. S2).

Fig. 6.

Senescence markers in human GH-producing pituitary adenomas. (A) Immunohistochemistry of the same GH-secreting human adenoma sections stained for p21 (brown) and SA-β-gal activity (blue). (B) Confocal image of double fluorescence immunohistochemistry of p21 (green) and β-galactosidase (red) proteins coexpression in human pituitary adenomatous but not in normal adjacent tissue (Left). High resolution (×63) image of the same slide (Right). (C) Proposed model for p21-induced senescence in the hypoplastic Pttg-null pituitary gland and PTTG-overexpressing pituitary adenomas. Arrows depict proposed pathways.

Discussion

Both pituitary hypoplasia and pituitary adenomas exhibit features of aneuploidy and p21 induction (23, 44). p21 is up-regulated and contributes to restraining cell cycle progression in the Pttg-null hypoplastic pituitary gland (23, 26). Intranuclear p21 is also observed in established GH-secreting pituitary adenomas, and when Pttg was either overexpressed or knocked down in GH3 cells, p21 levels were further enhanced.

Pttg-deficient pituitary glands are hypoplastic, and Pttg-null multipotent adult progenitor cells (45) and pituitary cells (23, 26) exhibit decreased cell proliferation and premature senescence associated with p53/p21 activation. Abundant p21 expression underlies decreased pituitary tumor development in Pttg-deficient Rb+/− mice (23). Indeed, when p21 was deleted, the number of Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− animals developing pituitary tumors reverted to the high tumor penetrance observed in Rb+/− animals. While Pttg ablation protects Rb+/− mice from developing thyroid tumors, p21 deletion, unlike in the pituitary, did not increase the incidence of these tumors in Rb+/−Pttg−/− mice. This finding is not surprising given that thyroid p21 levels are not elevated in Pttg-null mice (not shown). Thus, removal of p21 from the Rb+/−Pttg−/− background appears to be a selective determinant of pituitary tumorigenesis.

p21 deletion enhanced Rb+/−Pttg−/− pituitary phosphoRb and PCNA, both indicative of accelerated pituitary cell replication. Surprisingly, p21 absence did not affect spleen or lung Rb and PCNA protein levels, further highlighting a pituitary-selective role for p21 in these animals. p21 tissue specificity has been reported, and Rb induces the p21 promoter in epithelial cells, but not in fibroblasts (46). Thus, Pttg deletion resulted in pituitary, but not thyroid, thymic, or splenic p21 induction (23). Effects of PTTG perturbation on p21 expression and cell cycle arrest may therefore be pituitary-selective.

p21 deletion or mutation is not commonly encountered in human tumors, and mice lacking p21 exhibit moderately increased spontaneous tumor development only after 16 months (47). p21 may exert a cell- or tissue-specific tumor-suppressing function, unmasked under conditions where other genetic alterations or stresses are present. Thus, p21 deficiency accelerated Ras-dependent oncogenesis in MMTV/v-Ha-ras mice (48), and we show that high p21 levels are associated with restrained pituitary tumor formation in mutant Rb+/−Pttg−/− mice.

Surveillance mechanisms protecting genome integrity maintain the status of chromosomal DNA (39). In addition to direct repair of DNA breaks, cells respond to DNA damage by halting cell cycle progression, or undergoing programmed cell death, with both processes requiring p53 and p21 (32). Enhanced apoptosis was not evident in the Pttg−/− pituitary (26) while proteins associated with DNA repair are induced. Chk2 is constitutively elevated in senescent cells and also contributes to cell cycle restraint through p21 up-regulation (39), and Chk2 is activated in primary Pttg−/− MEFs. p21 directly inhibits Cdk2, thereby limiting cell cycle progression, also evident by observed decreased Rb phosphorylation.

MEFs are often reflective of in vivo processes and are useful to study cell tumorigenic potentials. p21 deletion enhanced transformation of Rb+/−Pttg−/− primary fibroblasts. These results are concordant with increased anchorage-independent growth observed in Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− MEFs (23) and indicate that these primary cells exhibit tumorigenic potential.

H2AX is a core histone H2A variant, and H2AX phosphorylation foci (γ-foci) are evident at sites of double-stranded DNA breaks (DSB). Cells normally exhibit abundant small foci, with decreased focus number, but their size increases with DSB accumulation (40, 41). γ-foci were increased in Rb+/−Pttg−/− and Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− MEFs, implying that Rb and Pttg mutations facilitate DNA damage. Although DSB levels are similar in Rb+/−Pttg−/− and Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− cells, MEFs lacking p21 proliferate faster and are more readily transformed. p21 therefore protects damaged cells from proliferation and transformation.

WT pituitary cells exhibit weak cytoplasmic p21 expression, while Pttg-deficient pituitary glands exhibit intranuclear p21 localization, especially in GH- and PRL- and, to a lesser extent, in MSH-producing cells (23). The results showing induced intranuclear p21 in pituitary tumor cells also overexpressing Pttg are seemingly inconsistent with the conclusion that Pttg absence restrains pituitary tumor development by activating p21 senescent pathways. Pttg behaves as an oncogene (19) and is permissive for pituitary tumor formation in mice (14, 26). Both loss of Pttg and Pttg overexpression result in aneuploidy (here and in refs. 22 and 26), and Pttg overexpression triggers genetic instability characterized by DNA breakage (20, 21, 44). Whether aneuploidy is the cause of DNA damage signaling-pathway activation remains unproven, but both processes activate p21 expression (33). p21 is strongly induced in aneuploid cells and functions to preserve chromosomal stability by suppressing cell cycle progression (34). Here we observe high p21 levels in Pttg-null anterior pituitary cells and also in GH-secreting GH3 cells where Pttg was either silenced or overexpressed, as well as in human GH-secreting adenomas overexpressing Pttg. In the Pttg-null hypoplastic pituitary, p21 expression is associated with pituitary cell senescence, and leads to restrained cell growth. Furthermore, in Pttg-overexpressing pituitary tumors, p21 acts as a tumor suppressor on the background of genomic instability (33) to restrain proliferation and trigger senescence. Thus, altered PTTG expression results in activation of p53/p21 senescence in both Pttg- deficient and Pttg-overexpressing pituitary cells (Fig. 6C).

Although PTTG and p21 are coexpressed in the same tumor, these proteins do not appear to colocalize in the same cell. PTTG is a cell cycle protein expressed mostly during mitosis and in G2, whereas p21 is overexpressed in G1 to prevent the damaged cell from entering S phase.

We did not observe an inverse correlation between tumor size and levels of p21 expression. Our hypothesis is that PTTG, functioning as an oncogene, acts proximally in tumor formation, and, as a result of aneuploidy and DNA damage, p21 appears later to restrain subsequent tumor growth and malignant transformation. This hypothesis is supported by clinical observations that tumor size and malignancy are not reciprocally correlated. In fact, the overwhelming majority of large invasive pituitary adenomas are not malignant (2).

ACTH-secreting microadenomas are mostly immunonegative for p21, and ≈30% of PRL-secreting microadenomas are positive for p21. FSH-, LH-, null-adenomas, and oncocytomas are mostly negative for p21 immunoreactivity. However, >70% of GH-secreting adenomas strongly express p21. Although a cell lineage specific effect is evident in pituitary adenomas, p21 expression in the normal non-tumorous pituitary is very low. The results therefore indicate that tumor growth triggers p21 expression predominantly in GH-secreting, and to a lesser extent in PRL-secreting, tumor cells.

Mechanisms underlying specific endocrine cell sensitivity to globally disrupted PTTG levels are unclear. Of note, the evolutionarily conserved GH-IGF1 growth pathway is critical for lifespan regulation, and this axis is attenuated when DNA damage and genomic instability accumulate to induce senescence (49). These observations underscore the sensitivity of GH-secreting cells to PTTG-induced genomic instability, and resultant p21 induction and senescence may constrain tumor growth. This postulate is consistent with experimental and clinical observations that somatotrophs are more sensitive to aging, radiation damage, or compressive damage than other pituitary cell types (50, 51). Our data (not shown) indicate that, unlike rat thyroid FRTL cells, GH3 cells are extremely sensitive to etoposide-induced DNA damage responding with p21 induction and senescence. Pathways restraining pituitary tumor growth and progression are lineage-specific, as shown in pituitary gonadotrophs, where MEG3 functions as a tumor suppressor gene in a p21-independent manner (7).

The results depict an in vivo model for pituitary senescence, whereby a proto-oncogene switches between oncogenic and tumor-suppressive modes depending on the genetic context. Thus, similar to the KLF4 transcription factor (35), Pttg behaves as either a tumor suppressor or oncogene depending on p21 status which couples cell cycle control and maintenance of chromosomal stability (33, 34). High levels of Pttg behaving as a securin protein, cause defective metaphase-anaphase progression and chromosomal instability, and promote pituitary tumor formation. Activation of pituitary DNA damage pathways triggers p21, a barrier to tumor growth (52), which in turn may restrain further growth and malignant transformation of pituitary tumors

Methods

Animals.

Experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Pretumorous 2–4 month Rb+/−Pttg−/−, Rb+/−Pttg+/+, Rb+/+ Pttg−/−, Rb+/+Pttg+/+, and Rb+/−Pttg−/−p21−/− mice and MEFs were used in this study.

Human Tissue Samples.

Pituitary tumors were collected at transphenoidal surgery according to an approved Institutional Review Board protocol. Normal anterior pituitary controls were obtained at surgery or from fresh autopsy specimens.

Details for techniques and procedures can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

Acknowledgments.

We thank Fabio Redondo, Tamar Eigler, and Drs. Run Yu and Martha Cruz-Soto for valuable technical assistance, and the staff of the Cedars Sinai Comparative Medicine Department for exemplary animal care. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA75979 (to S.M.) and The Doris Factor Molecular Endocrinology Laboratory.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0804810105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Farrell WE. Pituitary tumours: Findings from whole genome analyses. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13:707–716. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheithauer BW, et al. Pathobiology of pituitary adenomas and carcinomas. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:341–353. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000223437.51435.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vidal S, et al. Reversible transdifferentiation: Interconversion of somatotrophs and lactotrophs in pituitary hyperplasia. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:20–28. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melmed S. Mechanisms for pituitary tumorigenesis: The plastic pituitary. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1603–1618. doi: 10.1172/JCI20401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ezzat S, Asa SL. Mechanisms of disease: The pathogenesis of pituitary tumors. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2006;2:220–230. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fedele M, et al. HMGA2 induces pituitary tumorigenesis by enhancing E2F1 activity. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:459–471. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou Y, et al. Activation of p53 by MEG3 non-coding RNA. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24731–24742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lania AG, Mantovani G, Spada A. Mechanisms of disease: Mutations of G proteins and G-protein-coupled receptors in endocrine diseases. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2006;2:681–693. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carbia-Nagashima A, et al. RSUME, a small RWD-containing protein, enhances SUMO conjugation and stabilizes HIF-1alpha during hypoxia. Cell. 2007;131:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pei L, Melmed S. Isolation and characterization of a pituitary tumor-transforming gene (PTTG) Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:433–441. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.4.9911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zou H, McGarry TJ, Bernal T, Kirschner MW. Identification of a vertebrate sister-chromatid separation inhibitor involved in transformation and tumorigenesis. Science. 1999;285:418–422. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5426.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu R, et al. Pituitary tumor transforming gene causes aneuploidy and p53-dependent and p53-independent apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36502–36505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000546200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Z, Yu R, Melmed S. Mice lacking pituitary tumor transforming gene show testicular and splenic hypoplasia, thymic hyperplasia, thrombocytopenia, aberrant cell cycle progression, and premature centromere division. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1870–1879. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.11.0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abbud RA, et al. Early multipotential pituitary focal hyperplasia in the alpha-subunit of glycoprotein hormone-driven pituitary tumor-transforming gene transgenic mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1383–1391. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernal JA, et al. Human securin interacts with p53 and modulates p53-mediated transcriptional activity and apoptosis. Nat Genet. 2002;32:306–311. doi: 10.1038/ng997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tong Y, Tan Y, Zhou C, Melmed S. Pituitary tumor transforming gene interacts with Sp1 to modulate G1/S cell phase transition. Oncogene. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romero F, et al. Human securin, hPTTG, is associated with Ku heterodimer, the regulatory subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1300–1307. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.6.1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heaney AP, et al. Early involvement of estrogen-induced pituitary tumor transforming gene and fibroblast growth factor expression in prolactinoma pathogenesis. Nat Med. 1999;5:1317–1321. doi: 10.1038/15275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vlotides G, Eigler T, Melmed S. Pituitary tumor-transforming gene: Physiology and implications for tumorigenesis. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:165–186. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim DS, et al. Securin induces genetic instability in colorectal cancer by inhibiting double-stranded DNA repair activity. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:749–759. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim D, et al. Pituitary tumour transforming gene (PTTG) induces genetic instability in thyroid cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:4861–4866. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu R, et al. Overexpressed pituitary tumor-transforming gene causes aneuploidy in live human cells. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4991–4998. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chesnokova V, et al. Senescence mediates pituitary hypoplasia and restrains pituitary tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10564–10572. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernal JA, et al. Proliferative potential after DNA damage and non-homologous end joining are affected by loss of securin. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:202–212. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z, et al. Pituitary tumor transforming gene-null male mice exhibit impaired pancreatic beta cell proliferation and diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3428–3432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0638052100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chesnokova V, et al. Pituitary hypoplasia in Pttg−/− mice is protective for Rb+/− pituitary tumorigenesis. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2371–2379. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brugarolas J, et al. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 by p21 is necessary for retinoblastoma protein-mediated G1 arrest after gamma-irradiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1002–1007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gartel AL, Tyner AL. The growth-regulatory role of p21 (WAF1/CIP1) Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 1998;20:43–71. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-72149-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharpless NE, DePinho RA. Telomeres, stem cells, senescence, and cancer. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:160–168. doi: 10.1172/JCI20761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. Oncogene-induced cell senescence-halting on the road to cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1037–1046. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra062285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michaloglou C, et al. BRAFE600-associated senescence-like cell cycle arrest of human naevi. Nature. 2005;436:720–724. doi: 10.1038/nature03890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. CDK inhibitors: Positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1501–1512. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen KC, et al. ATM and p21 cooperate to suppress aneuploidy and subsequent tumor development. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8747–8753. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barboza JA, et al. p21 delays tumor onset by preservation of chromosomal stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19842–19847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606343104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rowland BD, Peeper DS. KLF4, p21 and context-dependent opposing forces in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:11–23. doi: 10.1038/nrc1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vooijs M, Berns A. Developmental defects and tumor predisposition in Rb mutant mice. Oncogene. 1999;18:5293–5303. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacks T, et al. Effects of an Rb mutation in the mouse. Nature. 1992;359:295–300. doi: 10.1038/359295a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinberg RA. The retinoblastoma protein and cell cycle control. Cell. 1995;81:323–330. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartek J, Lukas C, Lukas J. Checking on DNA damage in S phase. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:792–804. doi: 10.1038/nrm1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sedelnikova OA, et al. Senescing human cells and ageing mice accumulate DNA lesions with unrepairable double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:168–170. doi: 10.1038/ncb1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McManus KJ, Hendzel MJ. ATM-dependent DNA damage-independent mitotic phosphorylation of H2AX in normally growing mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:5013–5025. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dimri GP, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9363–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurz DJ, Decary S, Hong Y, Erusalimsky JD. Senescence-associated (beta)-galactosidase reflects an increase in lysosomal mass during replicative ageing of human endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 20):3613–3622. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.20.3613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uccella S, et al. Aneuploidy, centrosome alteration and securin overexpression as features of pituitary somatotroph and lactotroph adenomas. Anal Quant Cytol Histol. 2005;27:241–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rubinek T, et al. Discordant proliferation and differentiation in pituitary tumor-transforming gene-null bone marrow stem cells. Am J Physiol. 2007;293:C1082–C1092. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00145.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Decesse JT, Medjkane S, Datto MB, Cremisi CE. RB regulates transcription of the p21/WAF1/CIP1 gene. Oncogene. 2001;20:962–971. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin-Caballero J, Flores JM, Garcia-Palencia P, Serrano M. Tumor susceptibility of p21(Waf1/Cip1)-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6234–6238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adnane J, et al. Loss of p21WAF1/CIP1 accelerates Ras oncogenesis in a transgenic/knockout mammary cancer model. Oncogene. 2000;19:5338–5347. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niedernhofer LJ, et al. A new progeroid syndrome reveals that genotoxic stress suppresses the somatotroph axis. Nature. 2006;444:1038–1043. doi: 10.1038/nature05456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Darzy KH, Shalet SM. Hypopituitarism following radiotherapy. Pituitary. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s11102–008-0088–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chandrashekar V, et al. Age-related alterations in pituitary and testicular functions in long-lived growth hormone receptor gene-disrupted mice. Endocrinology. 2007;148:6019–6025. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Halazonetis TD, Gorgoulis VG, Bartek J. An oncogene-induced DNA damage model for cancer development. Science. 2008;319:1352–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1140735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]