Abstract

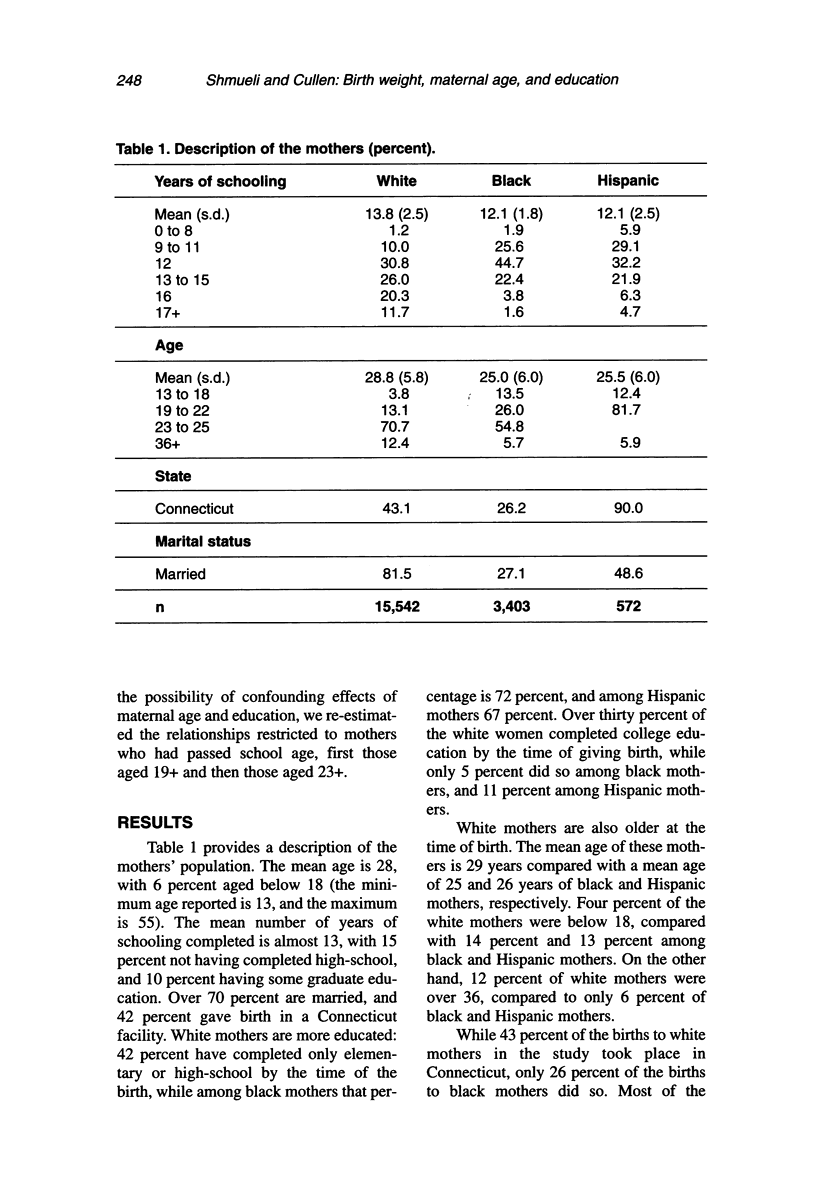

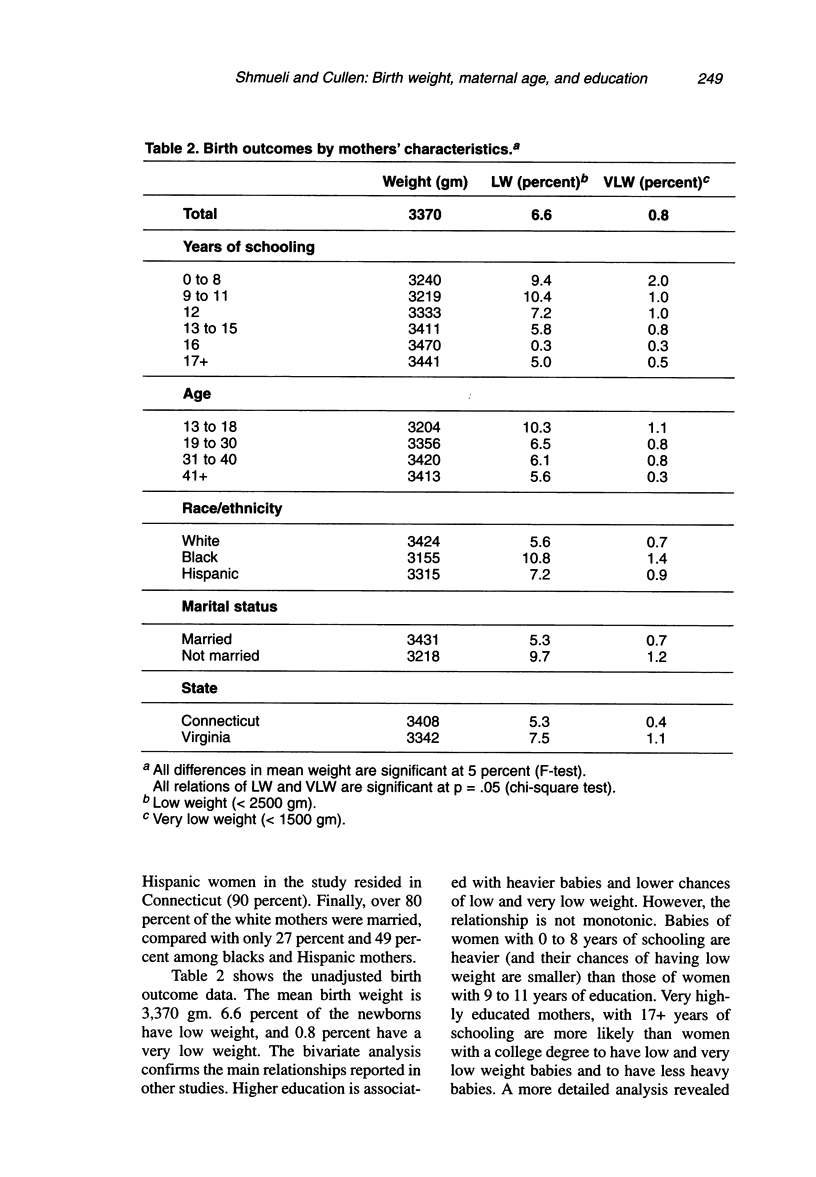

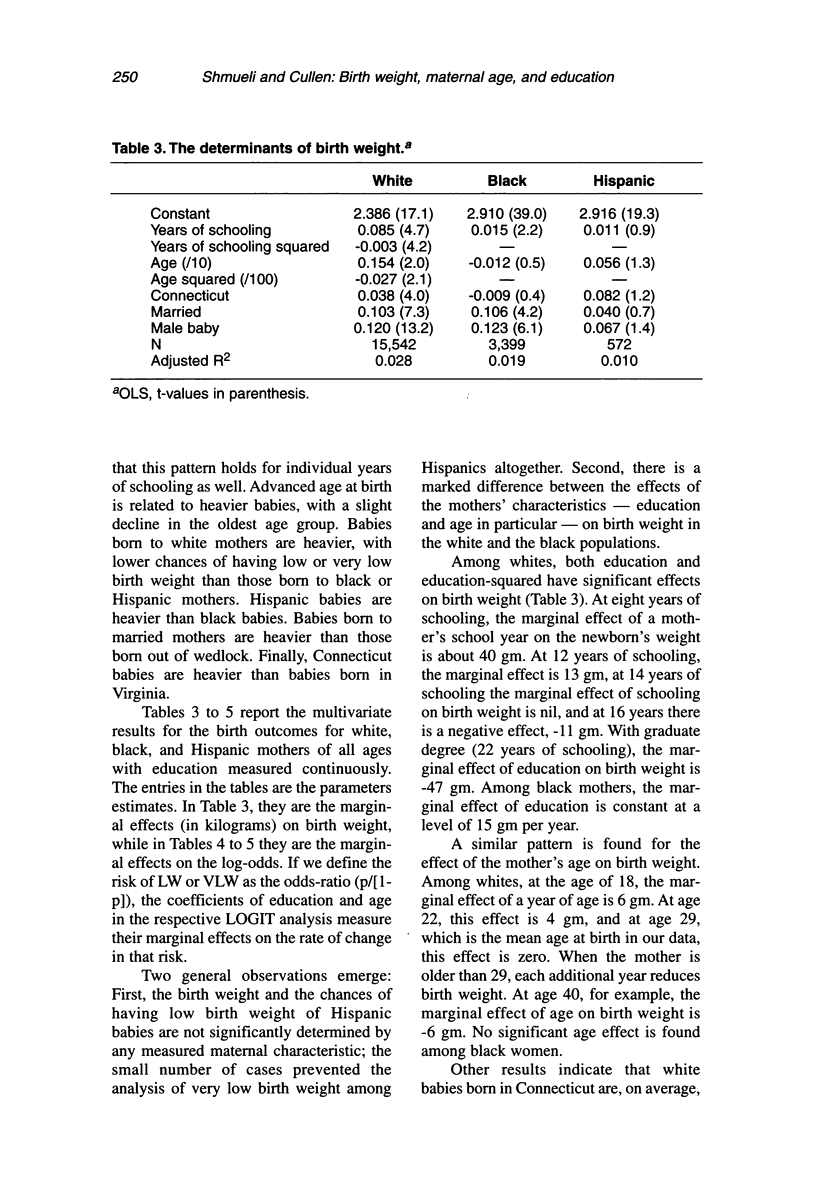

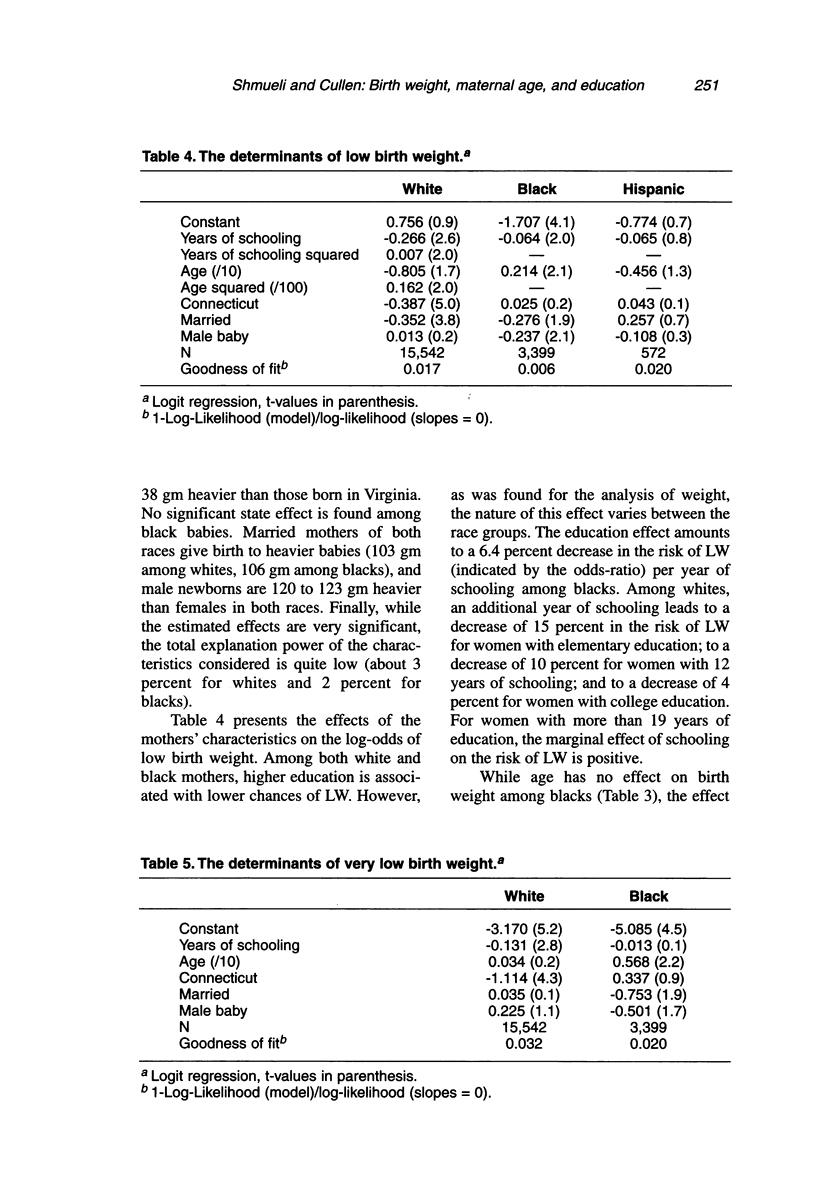

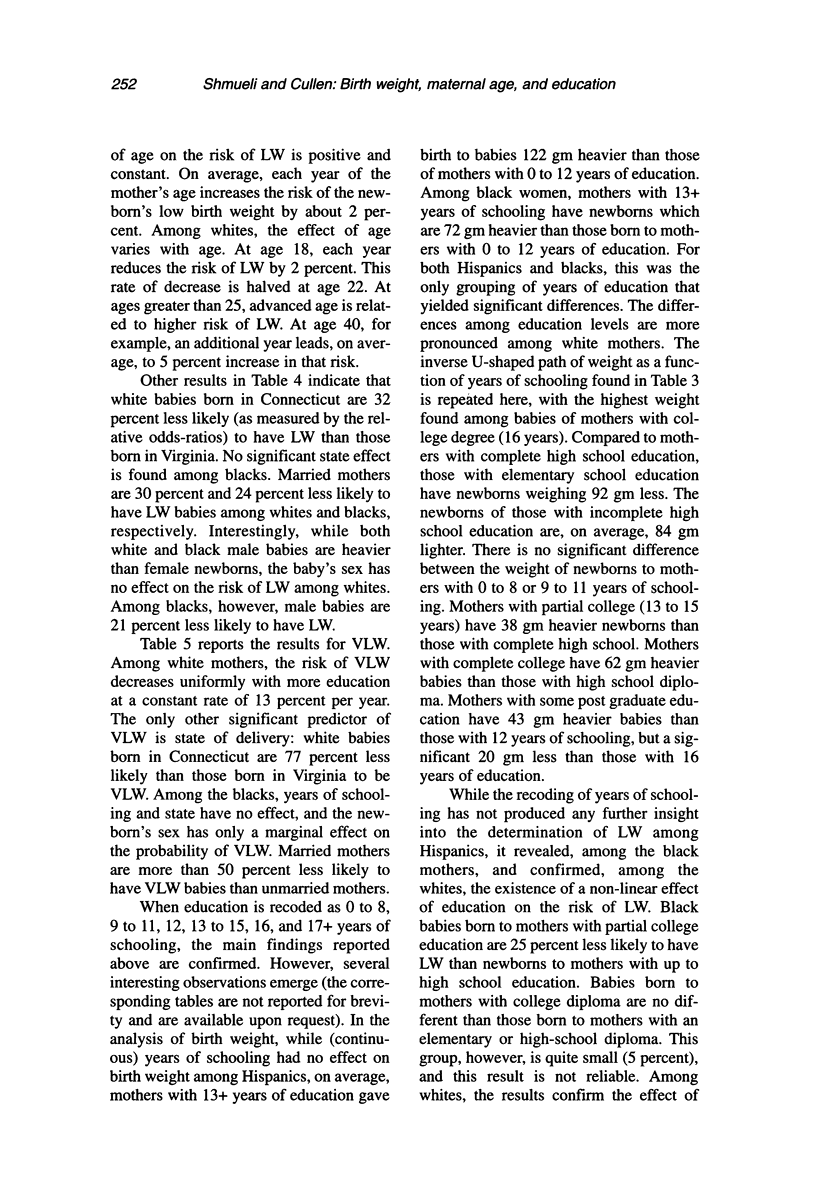

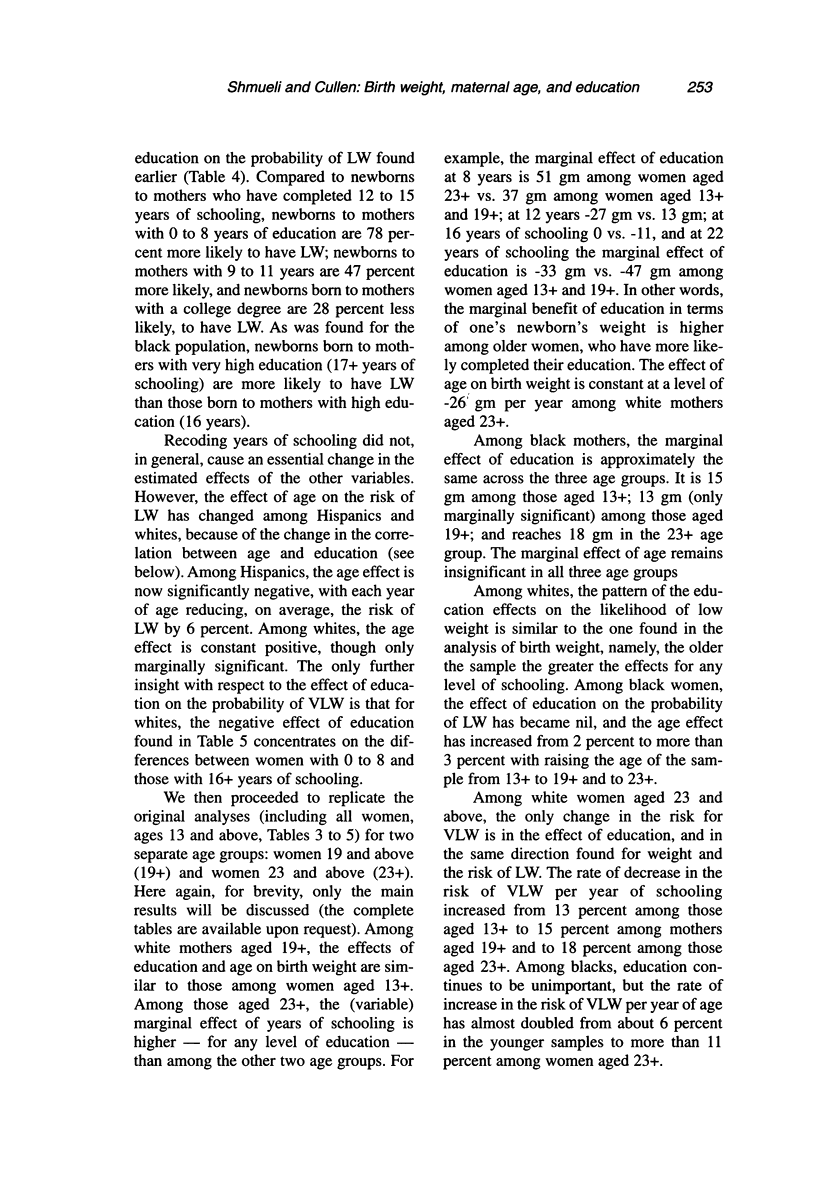

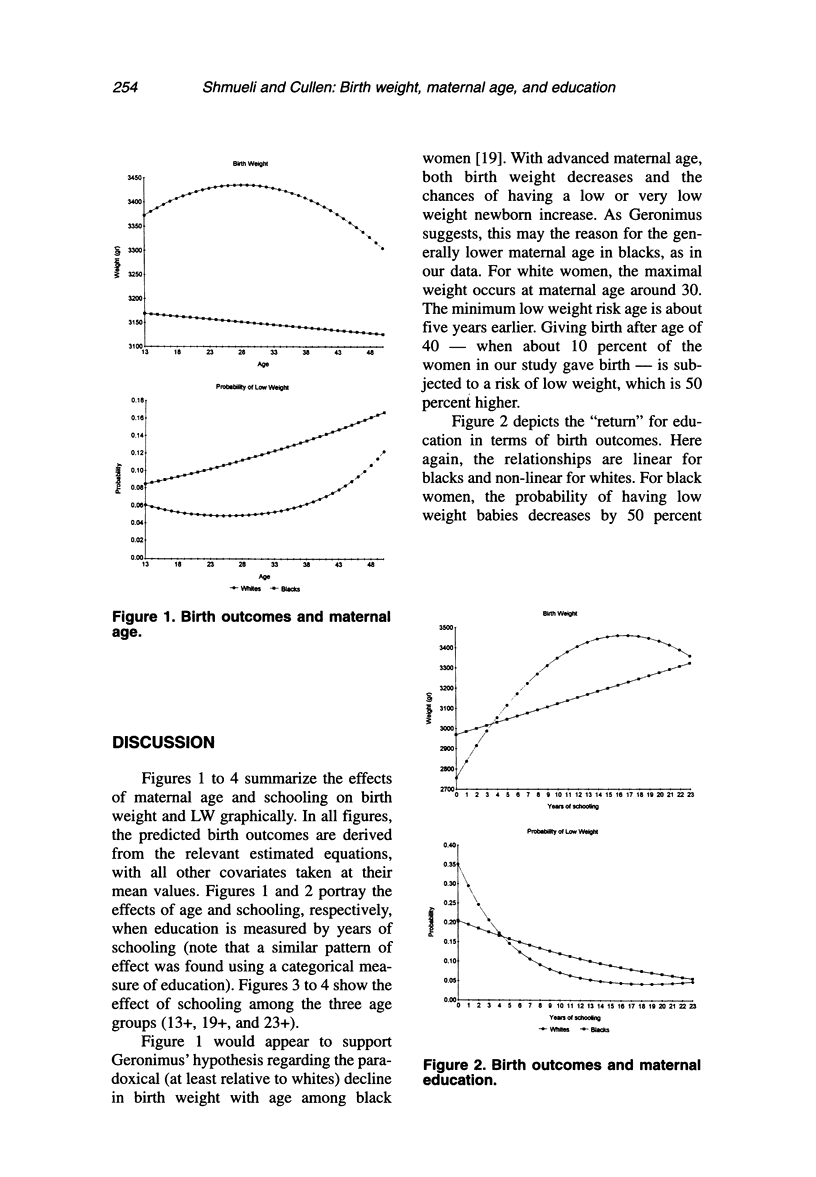

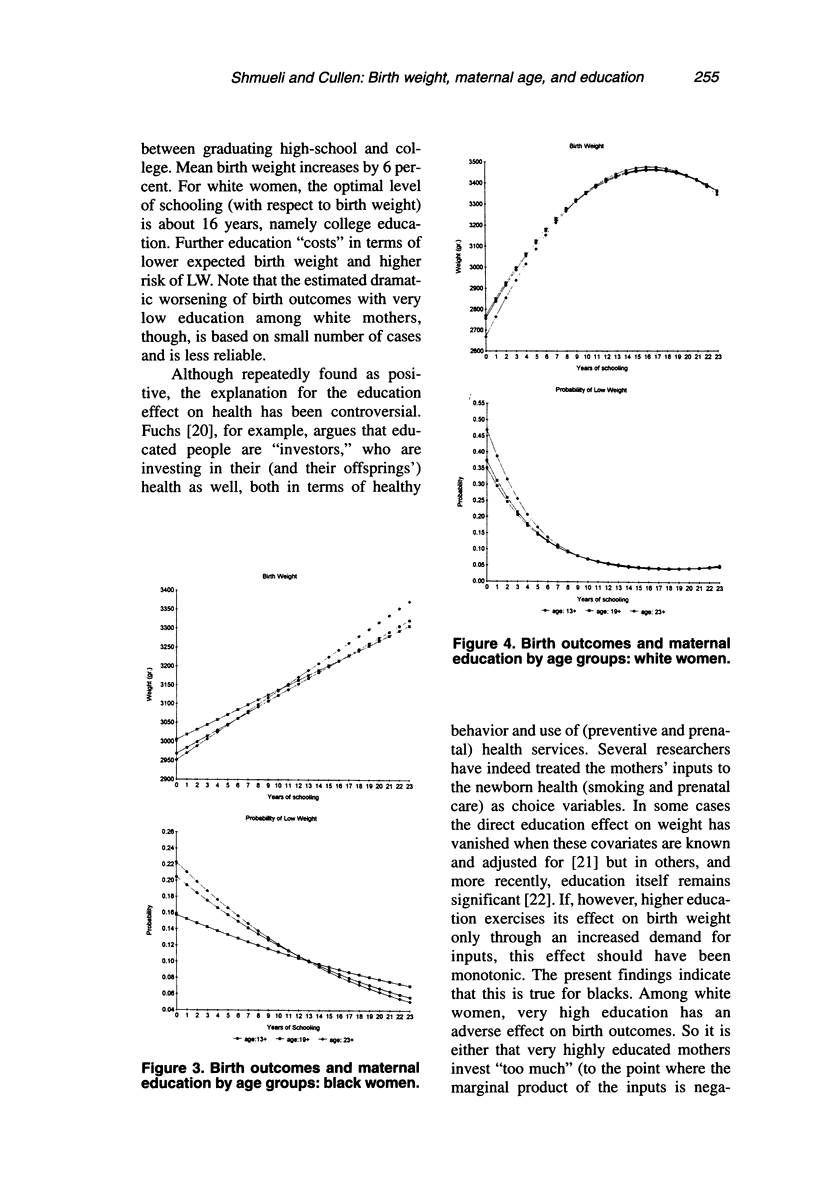

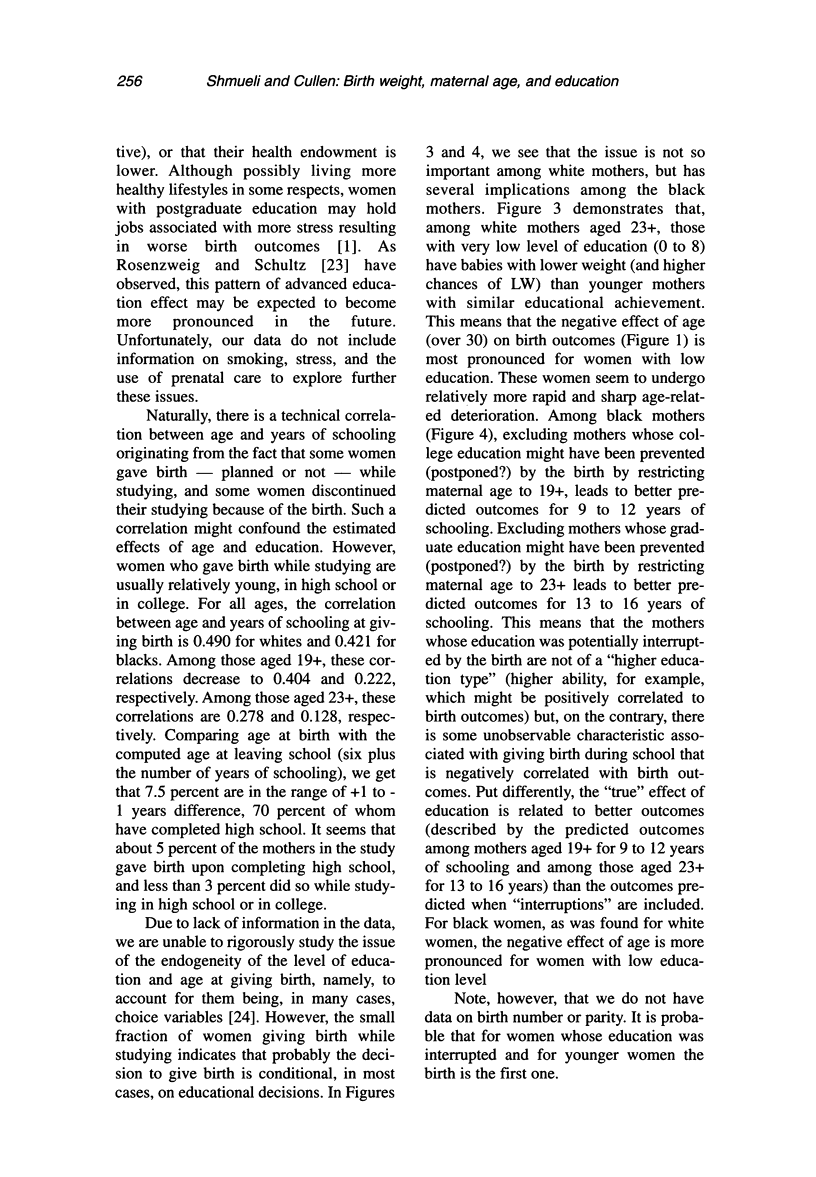

It has been well established that increased maternal education, income, and social status contribute to increased birth weight, as well as reduced risk for low or very low birth weight offspring. However, there remains controversy about the mechanism(s) for this effect, as well as the interactions between these factors, maternal age, and race. Presented here is the analysis of a large, recent sample of over 20,000 consecutive live births in 12 hospitals, about half in Connecticut and half in Virginia, including a maternal population that is educationally and racially diverse. Although information on potentially relevant details such as prenatal care, smoking, occupation, and neighborhood is lacking the data set, there is sufficient information to explore the previously noted strong effect of maternal education on birth weight, as well as the large racial difference in outcome at every educational level after adjustment for the effects of age, marital status, state of residence, and gender of the offspring. However, this relationship was not monotonic, and there were differences in the effect between the white and black families, with black women showing a linear and consistent benefit from education across the range, while whites show a sharp benefit from completion of primary education, less from subsequent schooling. A surprising result was the apparent negative impact of very advanced education (>16 years), with lowered birth weights and higher risk of low birth weight offspring in the women with post-college training. The data also shed some addition light on the effect of age and birth weight. Whites show established improvement in birth outcome to about age 30, with slight decline thereafter, whereas in blacks there was progressive decline in birth weight with rising age starting in adolescence, as previously demonstrated by Geronimus. An additional unexpected observation was a sizable difference between births in Connecticut (larger, fewer low birth weight) than Virginia, correcting for all other covariates. It is hypothesized that this may reflect differences in services used, prenatal care in particular given similarities in smoking rates and other predictors. Because of the non-representativeness of and the limited information available in the present study, the conclusions should be taken as hypotheses for further research rather than definitive.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barker D. J., Martyn C. N. The maternal and fetal origins of cardiovascular disease. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1992 Feb;46(1):8–11. doi: 10.1136/jech.46.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker D. J. The foetal and infant origins of inequalities in health in Britain. J Public Health Med. 1991 May;13(2):64–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N., DelDotto J. E., Brown G. G., Kumar S., Ezhuthachan S., Hufnagle K. G., Peterson E. L. A gradient relationship between low birth weight and IQ at age 6 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994 Apr;148(4):377–383. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1994.02170040043007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins J. W., Jr, Herman A. A., David R. J. Very-low-birthweight infants and income incongruity among African American and white parents in Chicago. Am J Public Health. 1997 Mar;87(3):414–417. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.3.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer J. C. Racial and ethnic differences in birthweight: the role of income and financial assistance. Demography. 1995 May;32(2):231–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson A., Eriksson M., Källén B., Zetterström R. Secular trends in the effect of socio-economic factors on birth weight and infant survival in Sweden. Scand J Soc Med. 1993 Mar;21(1):10–16. doi: 10.1177/140349489302100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus A. T. Black/white differences in the relationship of maternal age to birthweight: a population-based test of the weathering hypothesis. Soc Sci Med. 1996 Feb;42(4):589–597. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff C., Wertelecki W., Reyes E., Zansky S., Dutt J., Stumpe A., Till D., Butler R. M. Maternal sociomedical characteristics and birth weights of firstborns. Soc Sci Med. 1985;21(7):775–783. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsey T. C., Levkoff A. H., Alexander G. R., Tompkins M. Differences in black and white infant birth weights: the role of maternal demographic factors and medical complications of pregnancy. South Med J. 1991 Apr;84(4):443–446. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199104000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallan J. E. Race, intervening variables, and two components of low birth weight. Demography. 1993 Aug;30(3):489–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketterlinus R. D., Henderson S. H., Lamb M. E. Maternal age, sociodemographics, prenatal health and behavior: influences on neonatal risk status. J Adolesc Health Care. 1990 Sep;11(5):423–431. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(90)90090-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchen W. H., Ryan M. M., Rickards A., McDougall A. B., Billson F. A., Keir E. H., Naylor F. D. A longitudinal study of very low-birthweight infants. IV: An overview of performance at eight years of age. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1980 Apr;22(2):172–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1980.tb04326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M. S. Determinants of low birth weight: methodological assessment and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65(5):663–737. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick M. C., Brooks-Gunn J., Workman-Daniels K., Turner J., Peckham G. J. The health and developmental status of very low-birth-weight children at school age. JAMA. 1992 Apr 22;267(16):2204–2208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Campo P., Xue X., Wang M. C., Caughy M. Neighborhood risk factors for low birthweight in Baltimore: a multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health. 1997 Jul;87(7):1113–1118. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.7.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J. D., Schoendorf K. C., Kiely J. L. Associations between measures of socioeconomic status and low birth weight, small for gestational age, and premature delivery in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 1994 Jul;4(4):271–278. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shopland D. R., Hartman A. M., Gibson J. T., Mueller M. D., Kessler L. G., Lynn W. R. Cigarette smoking among U.S. adults by state and region: estimates from the current population survey. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996 Dec 4;88(23):1748–1758. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.23.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora C. G., Huttly S. R., Barros F. C., Lombardi C., Vaughan J. P. Maternal education in relation to early and late child health outcomes: findings from a Brazilian cohort study. Soc Sci Med. 1992 Apr;34(8):899–905. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90258-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Ding H., Ryan L., Xu X. Association between air pollution and low birth weight: a community-based study. Environ Health Perspect. 1997 May;105(5):514–520. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner G. L. Prenatal care demand and birthweight production of black mothers. Am Econ Rev. 1995 May;85(2):132–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]