Abstract

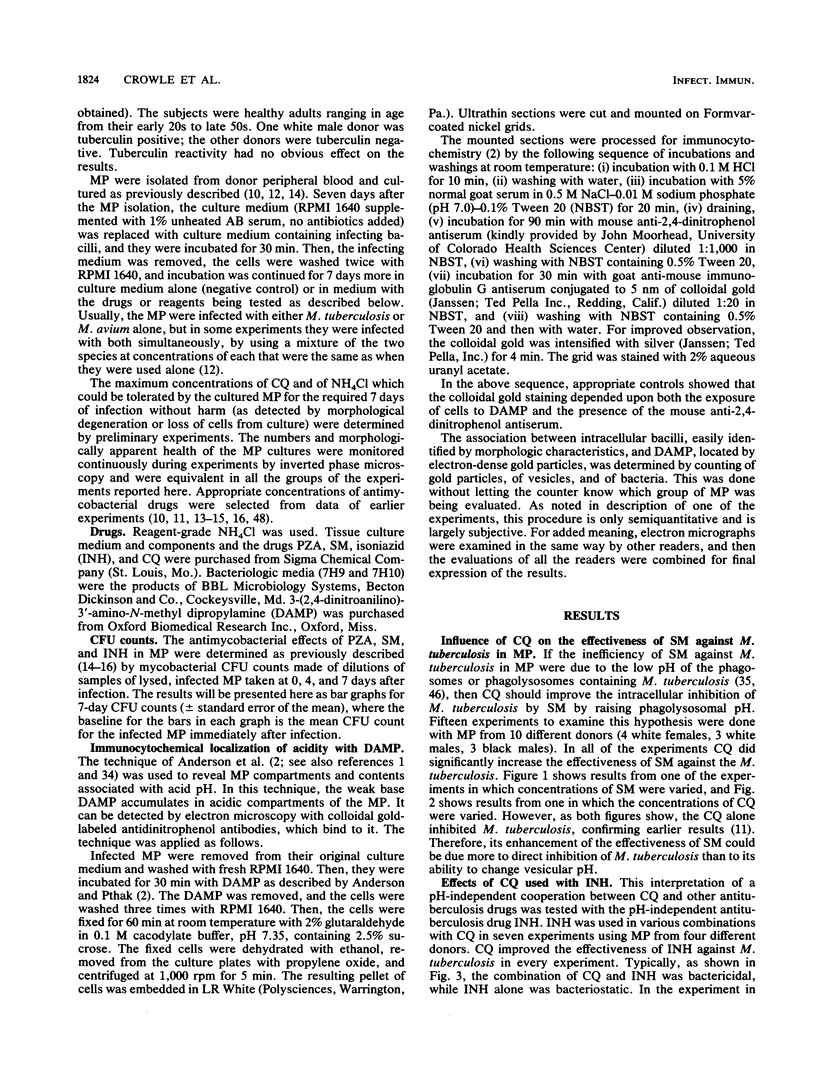

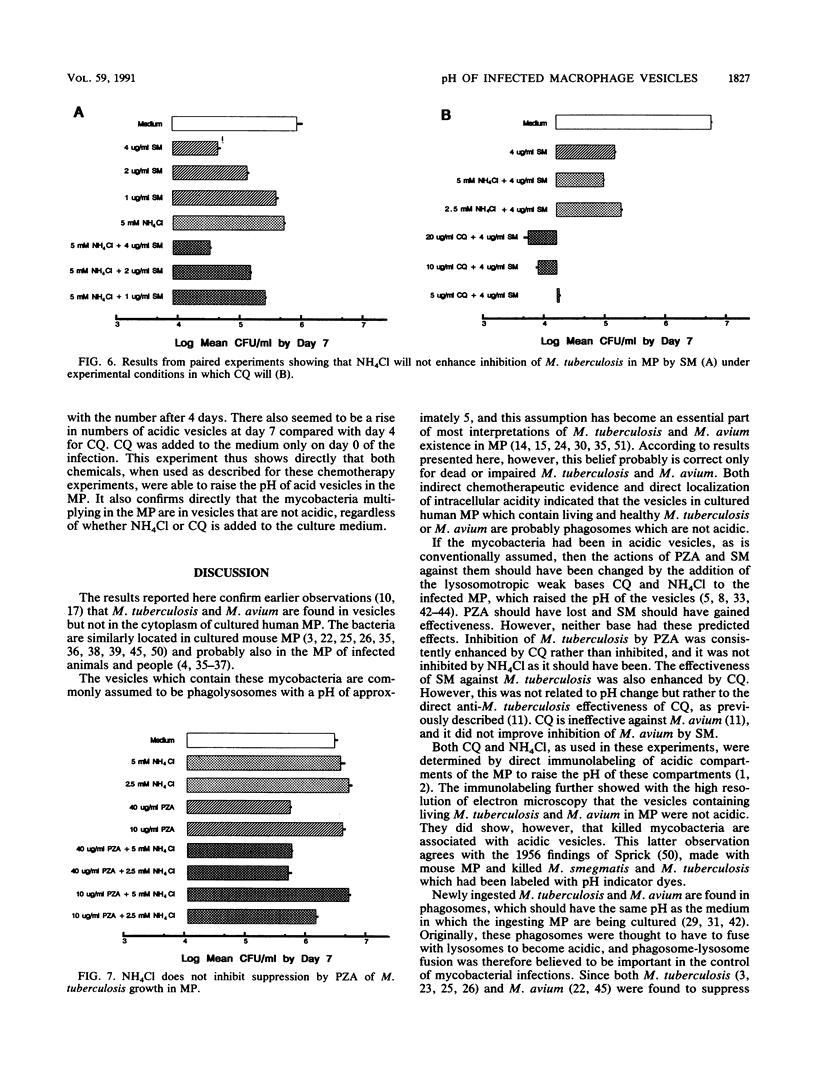

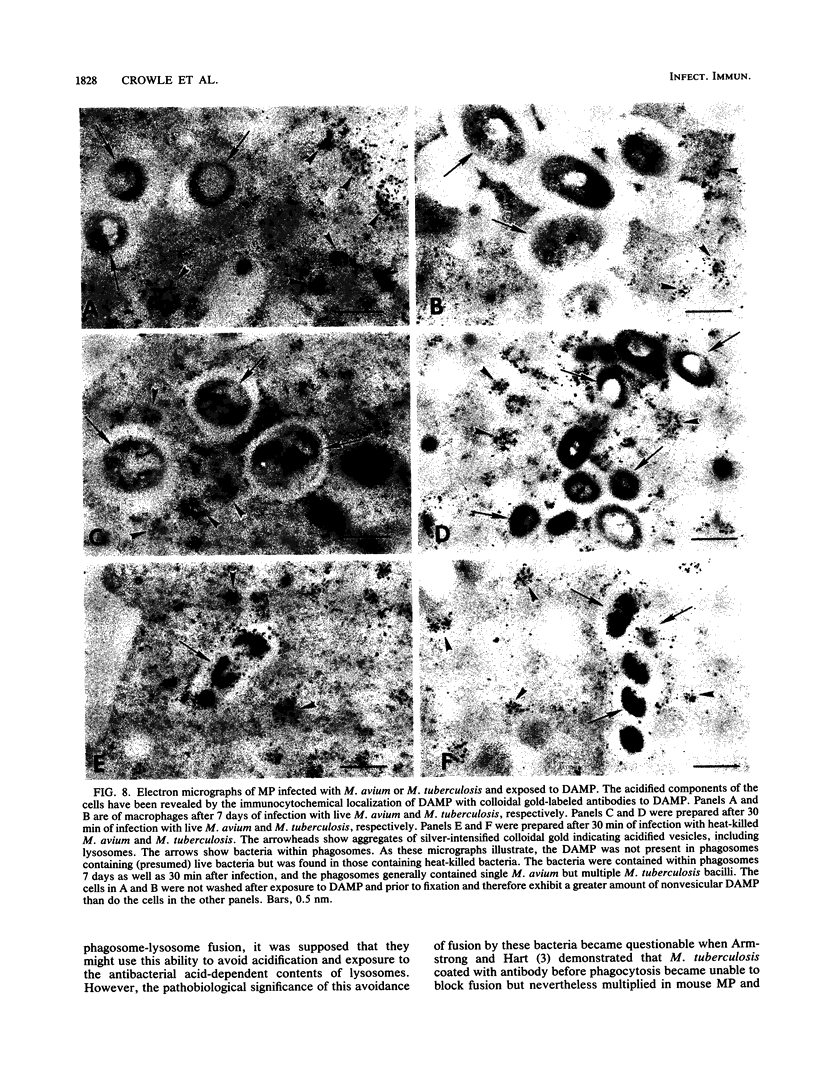

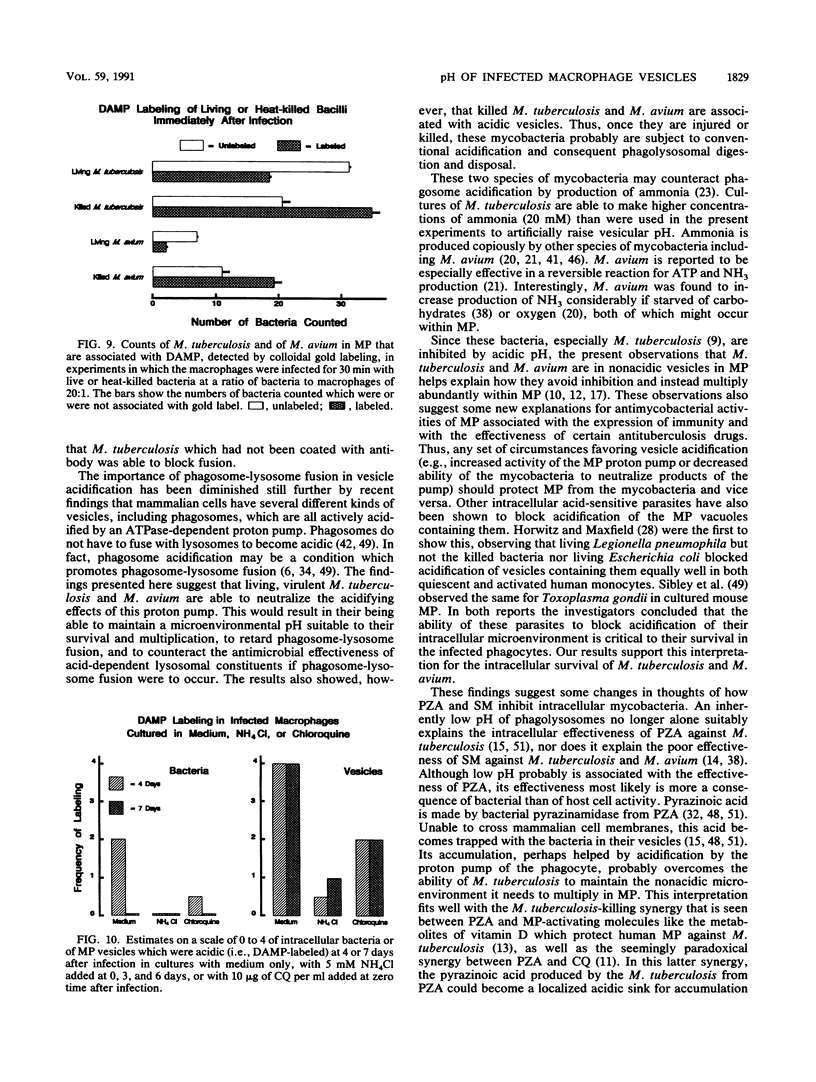

Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium multiply in cultured human macrophages (MP) within membrane-enclosed vesicles. These vesicles are generally assumed to be acidic. The evidence most frequently cited for this assumption is that pyrazinamide, which requires an acid pH to be effective, is effective and streptomycin, which loses most of its activity at a low pH, is poorly effective against tubercle bacilli. This assumption was tested by using the two weak bases chloroquine and NH4Cl to raise the pH of acidic vesicles in MP experimentally infected with M. tuberculosis or M. avium. An immunocytochemical locator of acidic regions in the MP was used to monitor the association of intracellular bacilli with acidity. MP were infected with M. tuberculosis or M. avium and incubated with various combinations of the drugs and the weak bases. Replication of the bacteria in the MP was measured by culture counts. Intracellular associations of the mycobacteria with acidity were assessed by electron micrographs and by using the weak base 3-(2,4-dinitroanilino)-3'-amino-N-methyl dipropylamine, which was detected with colloidal gold-labeled antibodies. It was confirmed by immunocytochemistry that both chloroquine and NH4Cl raise the pH of acidic vesicles in the infected MP. However, neither caused any pH-related change in the antimycobacterial activities of pyrazinamide or streptomycin or of the pH-independent drug isoniazid. Immunochemical analyses showed acidity to be associated with killed but not living mycobacteria in the MP. These findings suggest that living M. tuberculosis and M. avium are located in human MP in vesicles which are not acidic.

Full text

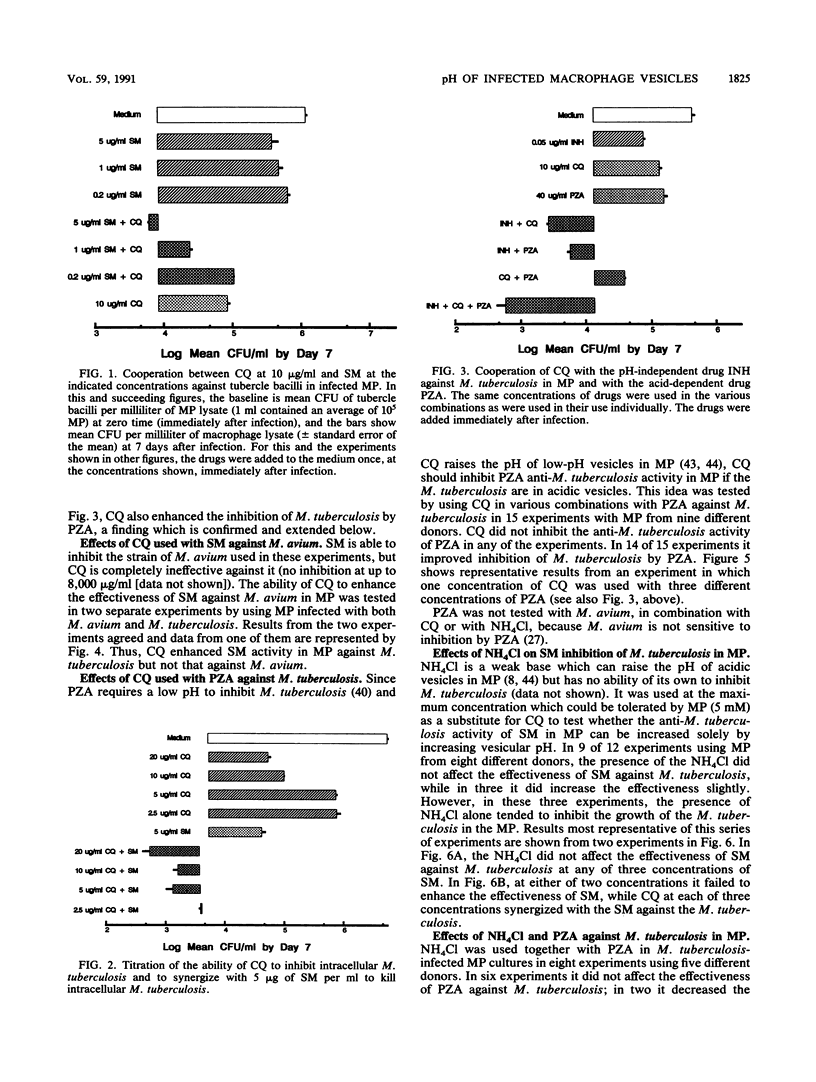

PDF

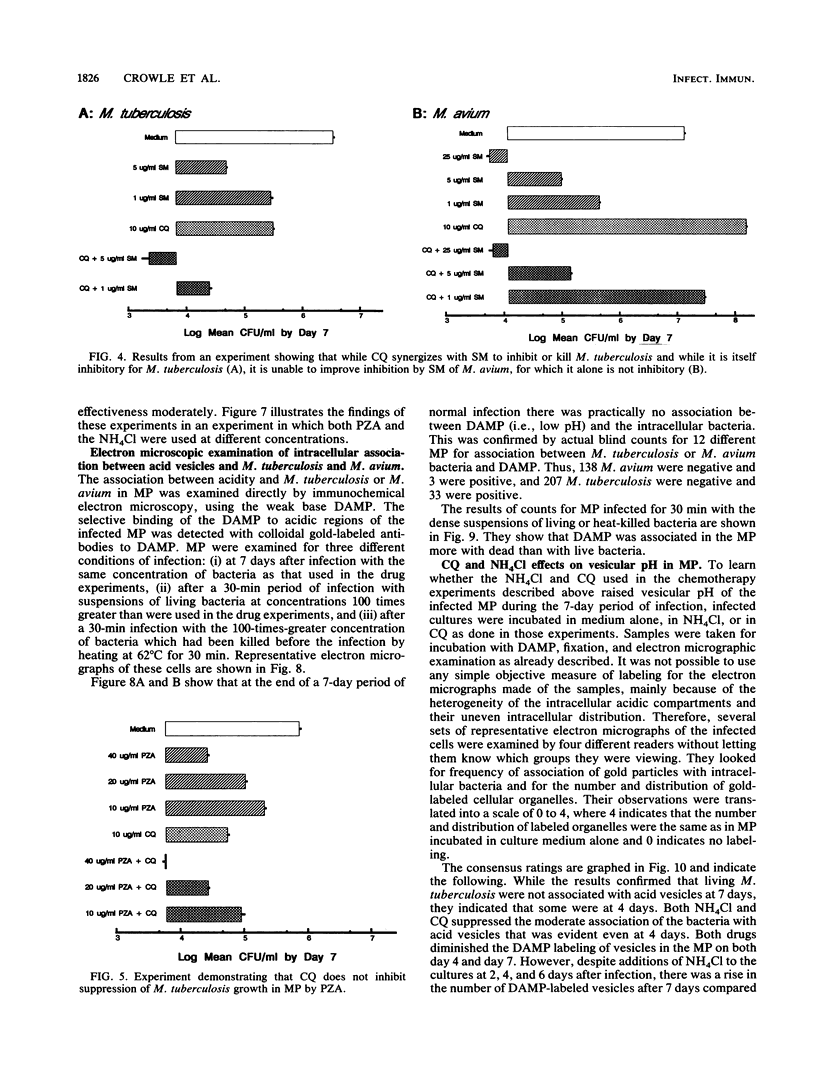

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson R. G., Falck J. R., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S. Visualization of acidic organelles in intact cells by electron microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Aug;81(15):4838–4842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.15.4838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R. G., Pathak R. K. Vesicles and cisternae in the trans Golgi apparatus of human fibroblasts are acidic compartments. Cell. 1985 Mar;40(3):635–643. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong J. A., Hart P. D. Response of cultured macrophages to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, with observations on fusion of lysosomes with phagosomes. J Exp Med. 1971 Sep 1;134(3 Pt 1):713–740. doi: 10.1084/jem.134.3.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj V., Colston M. J. The processing and presentation of mycobacterial antigens by human monocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1988 May;18(5):691–696. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830180506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black C. M., Paliescheskey M., Beaman B. L., Donovan R. M., Goldstein E. Acidification of phagosomes in murine macrophages: blockage by Nocardia asteroides. J Infect Dis. 1986 Dec;154(6):952–958. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.6.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonventre P. F., Imhoff J. G. Uptake of h-dihydrostreptomycin by macrophages in culture. Infect Immun. 1970 Jul;2(1):89–95. doi: 10.1128/iai.2.1.89-95.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAPMAN J. S., BERNARD J. S. The tolerances of unclassified mycobacteria. I. Limits of pH tolerance. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1962 Oct;86:582–583. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1962.86.4.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang P. L., Ameen M., Yu C. Z., Kelly B. M. Effect of ammonium chloride on subcellular distribution of lysosomal enzymes in human fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 1988 Jun;176(2):258–267. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(88)90329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowle A. J., May M. H. Inhibition of tubercle bacilli in cultured human macrophages by chloroquine used alone and in combination with streptomycin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and two metabolites of vitamin D3. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990 Nov;34(11):2217–2222. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.11.2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowle A. J., Poche P. Inhibition by normal human serum of Mycobacterium avium multiplication in cultured human macrophages. Infect Immun. 1989 Apr;57(4):1332–1335. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1332-1335.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowle A. J., Salfinger M., May M. H. 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 synergizes with pyrazinamide to kill tubercle bacilli in cultured human macrophages. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989 Feb;139(2):549–552. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.2.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowle A. J., Sbarbaro J. A., Judson F. N., Douvas G. S., May M. H. Inhibition by streptomycin of tubercle bacilli within cultured human macrophages. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984 Nov;130(5):839–844. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.130.5.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowle A. J., Sbarbaro J. A., May M. H. Effects of isoniazid and of ceforanide against virulent tubercle bacilli in cultured human macrophages. Tubercle. 1988 Mar;69(1):15–25. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(88)90036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowle A. J., Sbarbaro J. A., May M. H. Inhibition by pyrazinamide of tubercle bacilli within cultured human macrophages. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986 Nov;134(5):1052–1055. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.5.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowle A. J., Tsang A. Y., Vatter A. E., May M. H. Comparison of 15 laboratory and patient-derived strains of Mycobacterium avium for ability to infect and multiply in cultured human macrophages. J Clin Microbiol. 1986 Nov;24(5):812–821. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.5.812-821.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDSON N. L. The intermediary metabolism of the mycobacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1951 Sep;15(3):147–182. doi: 10.1128/br.15.3.147-182.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLFOLK N., KATUNUMA N. The occurrence of ammonia-activiating enzyme in various organisms. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959 Apr;81(2):521–522. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frehel C., de Chastellier C., Lang T., Rastogi N. Evidence for inhibition of fusion of lysosomal and prelysosomal compartments with phagosomes in macrophages infected with pathogenic Mycobacterium avium. Infect Immun. 1986 Apr;52(1):252–262. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.252-262.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon A. H., Hart P. D., Young M. R. Ammonia inhibits phagosome-lysosome fusion in macrophages. Nature. 1980 Jul 3;286(5768):79–80. doi: 10.1038/286079a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart P. D., Armstrong J. A., Brown C. A., Draper P. Ultrastructural study of the behavior of macrophages toward parasitic mycobacteria. Infect Immun. 1972 May;5(5):803–807. doi: 10.1128/iai.5.5.803-807.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart P. D., Armstrong J. A. Strain virulence and the lysosomal response in macrophages infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1974 Oct;10(4):742–746. doi: 10.1128/iai.10.4.742-746.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heifets L. B., Iseman M. D., Crowle A. J., Lindholm-Levy P. J. Pyrazinamide is not active in vitro against Mycobacterium avium complex. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986 Dec;134(6):1287–1288. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.6.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz M. A., Maxfield F. R. Legionella pneumophila inhibits acidification of its phagosome in human monocytes. J Cell Biol. 1984 Dec;99(6):1936–1943. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.6.1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacques Y. V., Bainton D. F. Changes in pH within the phagocytic vacuoles of human neutrophils and monocytes. Lab Invest. 1978 Sep;39(3):179–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindani A., Aber V. R., Edwards E. A., Mitchison D. A. The early bactericidal activity of drugs in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980 Jun;121(6):939–949. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.121.6.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. C. Macrophages and intracellular parasitism. J Reticuloendothel Soc. 1974 May;15(5):439–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno K., Feldmann F. M., McDermott W. Pyrazinamide susceptibility and amidase activity of tubercle bacilli. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1967 Mar;95(3):461–469. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1967.95.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad D. J., Schlesinger P. H. Acid-vesicle function, intracellular pathogens, and the action of chloroquine against Plasmodium falciparum. N Engl J Med. 1987 Aug 27;317(9):542–549. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198708273170905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley V., Robbins E. S., Nussenzweig V., Andrews N. W. The exit of Trypanosoma cruzi from the phagosome is inhibited by raising the pH of acidic compartments. J Exp Med. 1990 Feb 1;171(2):401–413. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.2.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowrie D. B. The macrophage and mycobacterial infections. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1983;77(5):646–655. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(83)90193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACKANESS G. B. The action of drugs on intracellular tubercle bacilli. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952 Jul;64(3):429–446. doi: 10.1002/path.1700640302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACKANESS G. B. The intracellular activation of pyrazinamide and nicotinamide. Am Rev Tuberc. 1956 Nov;74(5):718–728. doi: 10.1164/artpd.1956.74.5.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDERMOTT W., TOMPSETT R. Activation of pyrazinamide and nicotinamide in acidic environments in vitro. Am Rev Tuberc. 1954 Oct;70(4):748–754. doi: 10.1164/art.1954.70.4.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellman I., Fuchs R., Helenius A. Acidification of the endocytic and exocytic pathways. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:663–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.003311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill M. H. CARBOHYDRATE METABOLISM OF ORGANISMS OF THE GENUS MYCOBACTERIUM. J Bacteriol. 1930 Oct;20(4):235–286. doi: 10.1128/jb.20.4.235-286.1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkuma S., Poole B. Cytoplasmic vacuolation of mouse peritoneal macrophages and the uptake into lysosomes of weakly basic substances. J Cell Biol. 1981 Sep;90(3):656–664. doi: 10.1083/jcb.90.3.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole B., Ohkuma S. Effect of weak bases on the intralysosomal pH in mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Cell Biol. 1981 Sep;90(3):665–669. doi: 10.1083/jcb.90.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi N., David H. L. Mechanisms of pathogenicity in mycobacteria. Biochimie. 1988 Aug;70(8):1101–1120. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(88)90272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPRICK M. G. Phagocytosis of M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis stained with indicator dyes. Am Rev Tuberc. 1956 Oct;74(4):552–565. doi: 10.1164/artpd.1956.74.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salfinger M., Crowle A. J., Reller L. B. Pyrazinamide and pyrazinoic acid activity against tubercle bacilli in cultured human macrophages and in the BACTEC system. J Infect Dis. 1990 Jul;162(1):201–207. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley L. D., Weidner E., Krahenbuhl J. L. Phagosome acidification blocked by intracellular Toxoplasma gondii. 1985 May 30-Jun 5Nature. 315(6018):416–419. doi: 10.1038/315416a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele M. A., Des Prez R. M. The role of pyrazinamide in tuberculosis chemotherapy. Chest. 1988 Oct;94(4):845–850. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.4.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]