Abstract

Subunit a plays a key role in promoting H+ transport and the coupled rotary motion of the subunit c ring in F1F0-ATP synthase. H+ binding and release occur at Asp-61 in the middle of the second transmembrane helix (TMH) of F0 subunit c. H+ are thought to reach Asp-61 via aqueous pathways mapping to the surfaces of TMHs 2–5 of subunit a. TMH4 of subunit a is thought to pack close to TMH2 of subunit c based upon disulfide cross-link formation between Cys substitutions in both TMHs. Here we substituted Cys into the fifth TMH of subunit a and the second TMH of subunit c and tested for cross-linking using bis-methanethiosulfonate (bis-MTS) reagents. A total of 62 Cys pairs were tested and 12 positive cross-links were identified with variable alkyl length linkers. Cross-linking was achieved near the middle of the bilayer for the Cys pairs a248C/c62C, a248C/ c63C, a248C/c65C, a251C/c57C, a251C/c59C, a251C/c62C, a252C/c62C, and a252C/c65C. Cross-linking was achieved near the cytoplasmic side of the bilayer for Cys pairs a262C/c53C, a262C/c54C, a262C/c55C, and a263C/c54C. We conclude that both aTMH4 and aTMH5 pack proximately to cTMH2 of the c-ring. In other experiments we demonstrate that aTMH4 and aTMH5 can be simultaneously cross-linked to different subunit c monomers in the c-ring. Five mutants showed pH-dependent cross-linking consistent with aTMH5 changing conformation at lower pH values to facilitate cross-linking. We suggest that the pH-dependent conformational change may be related to the proposed role of aTMH5 in gating H+ access from the periplasm to the cAsp-61 residue in cTMH2.

The F1F0-ATP synthases of oxidative phosphorylation utilize the energy of a transmembrane electrochemical gradient of H+ or Na+ to mechanically drive the synthesis of ATP via two coupled rotary motors in the F1 and F0 sectors of the enzyme (1–3). In the intact enzyme, ATP synthesis or hydrolysis takes place in the F1 sector at the surface of the membrane, synthesis being coupled to H+ transport through the transmembrane F0 sector. Homologous enzymes are found in mitochondria, chloroplasts, and many bacteria (4). In Escherichia coli and other eubacteria, F1 consists of five subunits in an α3β3γδε stoichiometry (4). F0 is composed of three subunits in a likely ratio of a1b2c10 in E. coli and Bacillus subtilis PS3 or a1b2c11 in the Na+ translocating Ilyobacter tartaricus ATP synthase (3, 5–7), and may contain as many as 15 c subunits in other bacterial species (8). Subunit c spans the membrane as a helical hairpin with the first TMH2 on the inside and the second TMH on the outside of the c-ring (7, 9, 10). A high resolution x-ray structure of the I. tartaricus c11-ring has revealed the sodium binding site at the periphery of the ring with chelating groups to the bound Na+ extending from two interacting subunits (7). The essential I. tartaricus Glu-65 in the Na+ chelating site corresponds to E. coli Asp-61. In the H+-transporting E. coli enzyme, Asp-61 at the center of the second TMH is thought to undergo protonation and deprotonation as each subunit of the c ring moves past a stationary subunit a. In the complete membranous enzyme, the rotation of the c ring is proposed to be driven by H+ transport at the subunit a/c interface, with ring movement then driving rotation of subunit γ within the α3β3 hexamer of F1 to cause conformational changes in the catalytic sites leading to synthesis and release of ATP (1–3).

Subunit a folds in the membrane with 5 TMHs and is thought to provide aqueous access channels to the proton-binding Asp-61 residue on the c-ring (11–14). Interaction of the conserved Arg-210 residue in aTMH4 with cTMH2 is thought to be critical during the deprotonation-protonation cycle of cAsp-61 (14–17). Previously, we probed Cys residues introduced into the 5 TMHs of subunit a for aqueous accessibility based upon their reactivity with Ag+ (18–20). Two regions of aqueous access were found with distinctly different properties. One region in TMH4, extending from Asn-214 and Arg-210 at the center of the membrane to the cytoplasmic surface, contains Cys residues that are sensitive to inhibition by NEM and Ag+. A second set of Ag+-sensitive and NEM-insensitive residues mapped to the opposite face and periplasmic side of aTMH4. Ag+-sensitive and NEM-insensitive residues extending from the center of the membrane to the periplasmic surface were also found in TMHs 2, 3, and 5.

Little is known about the structure or three-dimensional arrangement of the TMHs in subunit a. Based initially upon the position of several sets of second site suppressor mutations, we recently introduced pairs of Cys into putatively apposing TMHs and tested for zero-length cross-linking with disulfide bond formation catalyzed by Cu2+ (21). Cross-links were found with eight different Cys pairs and define a juxtaposition of TMHs 2–3, 2–4, 2–5, 3–4, 3–5, and 4–5 packing in a proposed four-helix bundle (21). The Ag+-sensitive and NEM-insensitive residues in TMHs 2, 3, 4, and 5 cluster at the interior of the predicted four-helix bundle, and could interact to form a continuous aqueous pathway extending from the periplasmic surface to the center of the membrane (14, 20, 21). In the cross-linking supported model, the NEM-sensitive residues in TMH4 pack on the peripheral face and cytoplasmic side of the four-helix bundle (14, 18). Cu2+-catalyzed cross-links were also observed between Cys pairs introduced into aTMH4 and cTMH2 (22). Seven high yield cross-links were identified over a span of 19 amino acids, i.e. a span that would nearly traverse the bilayer. The cross-linkable faces of these helices would include Asp-61 in cTMH2 and the NEM- and Ag+-sensitive residues of aTMH4. The proximal placement of aTMH4 next to the c-ring dictated by these cross-links might also suggest that aTMH5 is close to cTMH2. A proximal interaction had previously been suggested because the essential Arg-210 residue in aTMH4 could be replaced by an Arg in aTMH5 in the aR210Q/Q252R suppressor strain with partial retention of function (16, 23). The function of the suppressor strain clearly suggested that cAsp-61, aArg-210, and aGln-52 should pack proximally to each other in the membrane. However, zero-length cross-links between aTMH5 and cTMH2 were not identified in a previous survey of 32 Cys pairs.3

In this study we have attempted to determine the distance between aTMH5 and cTMH2 using bis-MTS reagents that react to insert variable length spacers between cross-linkable Cys pairs. The bis-MTS derivatives react preferentially with the ionized, thiolate form of the Cys side chain (24, 25). Cross-linking was attempted in 62 Cys substituted pairs in aTMH5 and cTMH2 and positive cross-links were observed in 12 cases. The lack of cross-linking for the 50 surrounding Cys-Cys pairs indicates the structural specificity of the cross-links formed. Cross-linking for most pairs was largely pH insensitive. However, certain cross-links demonstrated a pH dependence that would be consistent with aTMH5 rotating in response to acidification of the local environment. We suggest from these results that aTMH5 packs next to the c-ring and could play a role in gating H+ transport to cAsp-61 in response to acidification of the periplasmic half-channel in F0.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construction of Cys-substituted Mutants—Cys substitutions were initially introduced into subunit a or subunit c by a two-step PCR method using a synthetic oligonucleotide, which contained the codon change, and two wild type primers (26). To generate the double mutant, plasmids containing single Cys substitutions in subunit a were digested with HindIII and BsrGI, and the insert containing the subunit a mutation was ligated into the vector containing the subunit c mutation. All mutations were confirmed by sequencing through the ligation sites. In the initial screen for cross-linkable Cys pairs, the double Cys mutants were transferred into plasmid pDF163, which encodes subunits a, b, c, and δ, and transformed into strain JWP109 that carries a chromosomal deletion for the genes of these subunits (22). All of the double Cys substitutions showing positive cross-links were eventually transferred into plasmid pCMA113, which contains a His6 tag on the C terminus of subunit a and an F1F0 where all native Cys have been substituted by Ala or Ser (18), and the biochemical characterization was carried out in this background. Each of the doubly Cys-substituted mutants grew on succinate minimal medium agar plates within the range of colony sizes seen for the singly substituted Cys mutants (20, 22, 27), i.e. 1.0–2.5 mm. The function of double Cys substitutions showing cross-linking was further evaluated by determining the growth yield on glucose and the capacity to pump protons as assessed by ATP-driven quenching of ACMA fluorescence (25).

Membrane Preparation—Inside-out membrane vesicles were prepared as follows. Plasmid transformant strains were grown in M63 minimal medium containing 0.6% glucose, 2 mg/liter thiamine, 0.2 mm uracil, 1 mm l-arginine, 0.02 mm dihydroxybenzoic acid, and 0.1 mg/ml ampicillin, supplemented with 10% LB medium, and harvested in the late exponential phase of growth (5). Cells were suspended in TMG buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 5 mm magnesium chloride, 10% glycerol, pH 8.5) containing 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.1 mg/ml DNase I and disrupted by passage through a French press at 1.38 × 108 newtons/m2 and membranes prepared as described (28). The final membrane preparation was suspended in TMG buffer and stored at -80 °C. Protein concentrations were determined using a modified Lowry assay (28).

Cross-linking with Bis-MTS Reagents—Membranes of a mutant were diluted to 10 mg/ml in TMG buffer at pH 6.5, 7.5, or 8.5. The bis-MTS reagents were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and added to the membranes to a final concentration of 2 mm. The reaction was incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The reaction was treated with 5 μl of 0.5 m Na2EDTA, pH 8.0, and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. βMSH was added to a final concentration of 4% by volume or alternatively DTT was added to a concentration of 20 mm to reduce the cross-link. The reduced samples were incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. Membranes were dissolved by addition of an equal volume of 2× SDS sample buffer (0.125 m Tris, 20% glycerol, 4% SDS, pH 6.8) before analyzing by SDS electrophoresis.

Cross-linking with Cu2+—Membranes of a mutant were diluted to 10 mg/ml in TMG buffer at the indicated pH value. A 15 mm CuSO4 and 45 mm o-phenanthroline solution was made in TMG at the same pH value as the membranes. Then, 5 μl of Cu2+-phenanthroline solution was added to 50 μl (0.5 mg) of membranes to begin cross-linking. The reaction was incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 5 μl of 0.5 m Na2EDTA, pH 8.0, and was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. To some samples βMSH was also added to a final concentration of 4% by volume. Membranes were dissolved by addition of an equal volume of 2× SDS sample buffer before analyzing by SDS electrophoresis.

SDS Electrophoresis and Immunoblotting—Samples were run on 15% Bio-Rad Criterion® gels. The gels were run for 60–90 min at 200 volts. The protein was transferred to PVDF membrane paper by applying 75 volts for 1.5 h in Towbin buffer (0.192 m glycine, 0.025 m Tris, 20% MeOH) (29). Western blotting was performed by incubating with 5 mg/ml of GE® Blocking Agent in 1× PBS-Tween (137 mm NaCl, 6.5 mm Na2HPO4, 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature or alternatively overnight at 4 °C. Rabbit antiserum made to the first 10 amino acids of subunit a was pre-absorbed to membranes lacking F0 to reduce immunoartifacts (30). The 1° antisera against subunit a was diluted 1:5,000 in 1× PBS-Tween with 2% bovine serum albumin and incubated with the PVDF membrane for 1 h at room temperature. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit 2° antibody was diluted 1:40,000 in 1× PBS-Tween and incubated with the PVDF membrane for 1 h at room temperature. The PVDF membrane was incubated for 4.5 min with equal volumes of SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrates (Pierce). The PVDF membrane was then exposed to film to visualize the protein.

Purification of a–c Complexes—Subunit a or the a–c dimer was purified using a method similar to that described (18). Samples were prepared as described above except 300 μl (3 mg) of membranes were used for each reaction and no EDTA was added at the end of the reaction. To the 300 μl of membranes, 10 μl of 62 mm bis-MTS reagent in dimethyl sulfoxide was added and the reaction incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Then, 660 μl of wash buffer (50 mm Tris, 0.3 m NaCl, 1% SDS, pH 8) and 40 μl of nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose beads (Qiagen) were added to each sample. The mixture was gently mixed on a rocker platform for 1 h at room temperature. The beads were harvested by centrifuging in a microcentrifuge for 7 s at a maximum of 10,000 rpm. The beads were washed twice with 1 ml of wash buffer. The protein was eluted from the beads with 100 μl of elution buffer (62.5 mm Tris, 10% glycerol, 20 mm Na2EDTA, 2% SDS, pH 6.75). To reduce some samples, 50 μl of the eluted protein was moved to a new tube and 1 μl of 100% βMSH was added. Samples were analyzed by SDS electrophoresis.

RESULTS

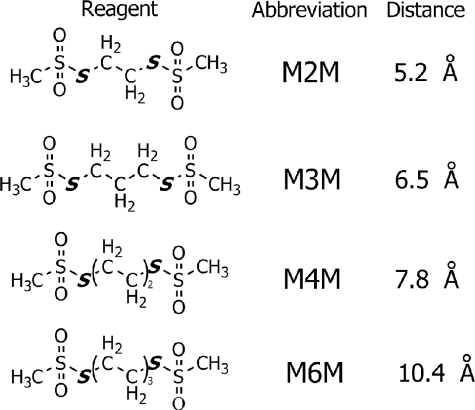

Cross-linking between aTMH5 and cTMH2—In a previous study from this laboratory, extensive Cu2+-catalyzed cross-linking between Cys substitutions in aTMH4 and cTMH2 was observed over a span of 19 amino acid residues in the two TMHs (22). However, no cross-linking between Cys introduced into aTMH5 and the cTMH2 substitutions was observed with 32 double Cys substitutions using the same method.4 These results suggest that aTMH4 may pack close to the periphery of the c-ring and that aTMH5 may pack at a greater distance. To investigate the proximity of aTMH5 to the c-ring, we utilized bis-MTS reagents with variable length spacers to probe for cross-linking in the current study (Fig. 1). The four reagents used in this study have a methanethiosulfonate moiety on both ends that reacts specifically with the thiolate form of a Cys side chain (24). These highly specific reagents have been used previously as “molecular rulers” to describe the packing of TMHs in P-glycoprotein (25), as perhaps the most definitive example.

FIGURE 1.

Structure of the four bis-MTS reagents used in this study. The theoretical distances between the sulfurs (S) forming disulfide bonds with Cys side chains is indicated (from Ref. 25).

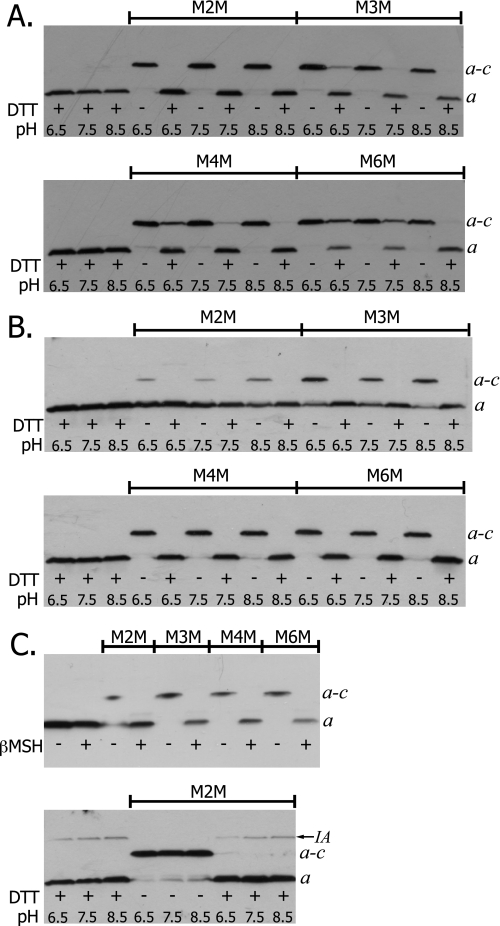

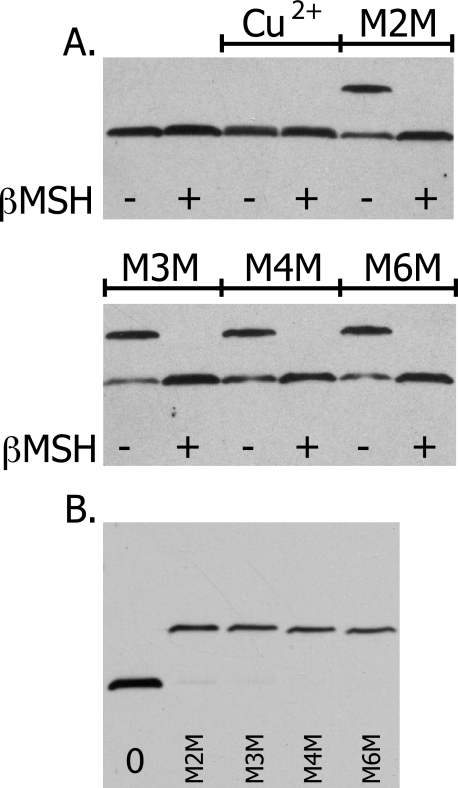

Based upon the positive a–c cross-links formed with the aN214C and cA62C or cM65C in cTMH2 (22), and because an efficient intrasubunit a cross-link can be achieved between aG218C and aI248C (21), we initiated experiments assuming that aI248C might also be close to cTMH2. Initially, cross-linking was attempted from position aI248C in TMH5 of subunit a to positions cV60C, cA62C, cI63C, and cM65C in cTMH2. Nearly quantitative cross-linking was achieved for the aI248C/cA62C double Cys mutant when membranes were treated with any of the four bis-MTS reagents (Fig. 2A). Cross-linking was indicated by the appearance of a slower migrating band that is shown by experiments described below to correspond to an a–c dimer. The cross-link was largely reversed upon the addition of the reductant DTT. Because the linkers require the thiolate form of Cys for reaction, the pH of the buffer was varied to determine the effect of pH on the cross-link product formation. Surprisingly, there was no discernable decrease in cross-link formation upon lowering the pH from 8.5 to 6.5. Cross-link formation with the M4M and M6M reagents was incompletely and inconsistently reversed by DTT treatment at the lower pH values in this and several other experiments (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Bis-MTS reagent catalyzed cross-link formation between Cys at position 248 in subunit a and at positions 62, 63, and 65 in subunit c. Membranes were treated with the indicated bis-MTS reagent according “Experimental Procedures.” The effect of pH on cross-link formation was determined by resuspending membrane pellets in TMG buffer at the indicated pH. Solubilized membranes were analyzed by SDS electrophoresis and Western blots were used to visualize subunit a. The bands corresponding to subunit a and the a–c dimer are indicated. A, aI248C/cA62C; B, aI248C/cI63C; and C, aI248C/cM65C. IA indicates immunoartifact.

Limited cross-linking was obtained for the aI248C/cI63C double Cys mutant with M2M but higher yields were achieved with the longer linkers (Fig. 2B). Dimer formation increased to near 100% efficiency as the linker length was further increased with the M4M and M6M reagents (Fig. 2B). As with aI248C/cA62C, varying the pH in the range of 6.5 to 8.5 had no effect on the efficiency of cross-link formation. The cross-link was completely reversed by DTT treatment. Nearly 100% cross-linking was obtained for the aI248C/cM65C double Cys mutant with all four bis-MTS reagents (Fig. 2C). As with aI248C/cA62C and aI248C/cI63C, no effect on the cross-link formation was seen upon varying the pH. An immunoartifact band that migrates slower than the a–c dimer upon reduction with DTT was observed in this experiment and in other experiments with βMSH reduction. This immunoartifact, marked IA in Fig. 2C, is occasionally seen and has greater intensity at higher pH values. The aI248C/cV60C double Cys mutant was not cross-linked with M2M, M4M, or M6M and indicated the specificity of cross-link formation for the aI248C/cA62C, aI248C/cI63C, and aI248C/cM65C mutants (Tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 1.

Cys pairs forming cross-links between cTMH2 and aTMH5 with M2 M at pH 8.5 Symbols indicate: 0, no cross-link formed; + approximately 10–25% cross-link formation; ++ approximately 25–60% cross-link formation; +++ approximately 75% cross-link formation; ++++ approximately 90–100% cross-link formation.

|

Subunit c

|

Subunit a

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trp-241 | Phe-244 | Leu-247 | Ile-248 | Ile-249 | Thr-250 | Leu-251 | Gln-252 | Val-262 | Tyr-263 | Met-266 | |

| Ala-39 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Ala-40 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Gln-42 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Pro-43 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Asp-44 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Arg-50 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Thr-51 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Phe-53 | ++ | 0 | |||||||||

| Phe-54 | ++++ | ++ | |||||||||

| Ile-55 | +++ | 0 | |||||||||

| Val-56 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Met-57 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | |||||||

| Gly-58 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Leu-59 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ++ | 0 | ||||||

| Val-60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Ala-62 | 0 | ++++ | 0 | 0 | ++ | ++ | |||||

| Ile-63 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Met-65 | +++ | 0 | 0 | 0 | ++ | ||||||

| Val-68 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Gly-71 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Tyr-73 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Val-74 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Met-75 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Phe-76 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Ala-77 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Val-78 | 0 | ||||||||||

TABLE 2.

Cys pairs forming cross-links between aTMH5 and cTMH2 using bis-MTS reagents of varying length Cross-linking at pH 8.5 was scored as in Table I.

| Mutant | M2M | M3M | M4M | M6M |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 248/62 | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| 248/63 | + | ++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| 248/65 | +++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| 251/57 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 251/59 | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| 251/62 | ++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| 252/62 | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| 252/65 | ++ | ++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| 262/53 | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| 262/54 | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| 262/55 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| 263/54 | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ |

To ensure specificity of the cross-links at aI248C, Cys mutants were constructed and tested between residues on opposite sides of the proposed helices of aTMH5 and cTMH2. A total of 15 mutants were tested for cross-linking between residues aL247C, aI248C, aI249C, or aT250C to cM57C, cL59C, cV60C, cA62C, cI63C, or cM65C. All 18 of the tested mutants were negative indicating that the cross-links were confined to one side of aTMH5 and one side of cTMH2 (Table 1).

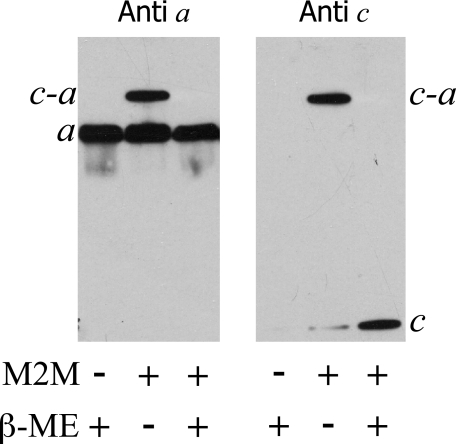

To verify the presence of both subunit a and subunit c in the proposed a–c dimer band, the His tag on subunit a was used to purify subunit a as described under “Experimental Procedures” before and after cross-linking. The purified protein from membranes of aI248C/cM65C treated with M2M exhibited two bands when analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Immunoblotting of the purified His-tagged subunit a or a–c products with antisera to both subunit a and subunit c separately confirmed that the lower band is non-cross-linked subunit a and the upper band is an a–c dimer (Fig. 3). When the purified, cross-linked products were treated with βMSH and probed with either antisera, one band was visible corresponding to either subunit a or subunit c (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Purified a–c dimer formed with M2M bis-MTS cross-linker. Membranes of the mutant aI248C/cM65C were treated with M2M and His-tagged subunit a or a–c dimer was purified as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A single gel was run with duplicate loading of samples to probe with both subunit a antibody and subunit c antibody. β-ME, mercaptoethanol.

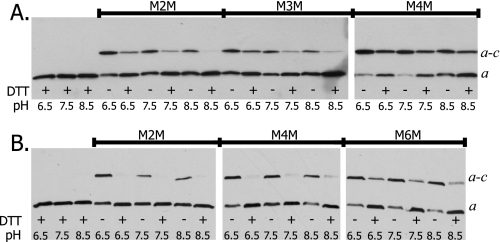

To continue the scan, Cys mutants were constructed and tested for cross-linking from aL251C to cM57C, cL59C, cV60C, cA62C, cI63C, and cM65C. The aL251C/cL59C double Cys mutant exhibited ∼50% cross-linking efficiency with the M2M linker (Fig. 4A). The amount of dimer formation for aL251C/cL59C decreased considerably when mutant membranes were treated with the M4M and M6M reagents (Fig. 4A). The aL251C/cA62C double Cys mutant exhibited ∼50% cross-linking efficiency with small linkers and greatly reduced cross-linking with M6M at pH 8.5 (Fig. 4B). The aL251C/cM57C pair showed 25% cross-linking with M2M at pH 8.5 and negligible cross-linking with the longer linkers (Table 2, and data not shown). Thus, unlike other cross-links identified in this study, the aL251C/cM57C, aL251C/cL59C, and aL251C/cA62C substitutions demonstrated a lower cross-linking efficiency with longer linkers. This could indicate that the space between the Cys pairs is limited and constrains the size of the linker. Cross-linking was not achieved between the aL251C and the cV60C, cI63C, or cM65C substitutions (Table 1). The M2M cross-linking of the aL251C/cL59C pair showed an unusual pH dependence where cross-link formation increased as the pH was decreased from 8.5 to 6.5 (Fig. 4A). The increase in cross-link formation with decreasing pH is less striking for the M4M and M6M linkers. A similar pH dependence with M2M was seen with the aL251C/cM57C substituted pair. Possible explanations for the pH dependence are discussed below.

FIGURE 4.

Bis-MTS reagent catalyzed cross-link formation between Cys at position 251 in subunit a and positions 59 and 62 in subunit c. Membranes were treated at the pH indicated in A or at pH 8.5 in B. Electrophoresis and Western blotting were carried out as described in the legend to Fig. 2. A, aL251C/cL59C; and B, aL251C/cA62C.

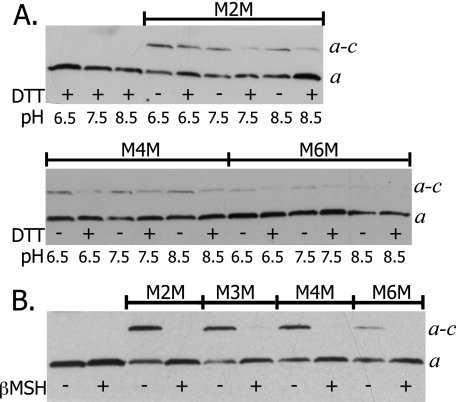

Cross-linking between aTMH5 and cTMH2 at the Cytoplasm—To further define the interaction of aTMH5 with cTMH2, cross-linking was attempted between residues that are proposed to be located at the cytoplasmic side of the membrane. Cross-linking was attempted from aV262C to cR50C, cQ51C, cF53C, cF54C, cI55C, and cV56C. The aV262C/cI55C double Cys mutant cross-linked efficiently with bis-MTS reagents at a range of pH values (Fig. 5A). A high yield cross-link was also achieved with Cu2+ at a range of pH values (Fig. 5B). The Cu2+ cross-link with the 262/55 Cys pair was unique in that the other 11 bis-MTS cross-linkable Cys pairs reported in this study were not cross-linkable with Cu2+ (data not shown). The aV262C/cF53C double Cys mutant exhibited 50–75% cross-link formation with all linkers and no cross-linking with Cu2+ (Fig. 6A). The aV262C/cF54C double Cys mutant cross-linked efficiently with all bis-MTS reagents at pH 8.5 (Fig. 6B). The efficiency of cross-link formation was unaffected by varying the pH from 8.5 to 6.5 with both mutants (data not shown). The 3 double Cys mutants from residues aV262C to cR50C, cQ51C, or cV56C showed no cross-linking with any linker (Table 1).

FIGURE 5.

Bis-MTS reagent and Cu2+ catalyzed cross-link formation between Cys at position 262 in subunit a and position 55 in subunit c at various pH values. aV262C/cI55C membranes were treated with bis-MTS (A) reagents or 1.5 mm Cu2+-phenanthroline (B) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Electrophoresis and Western blotting were carried out as described in the legend to Fig. 2.

FIGURE 6.

Bis-MTS reagent catalyzed cross-link formation between Cys at position 262 in subunit a and positions 53 and 54 in subunit c. Membranes were treated at pH 8.5 and electrophoresis and Western blotting were carried out as described in the legend to Fig. 2. A, aV262C/cF53C; and B, aV262C/cF54C.

Cross-linking between aTMH5 and cTMH2 at the Periplasm—Several attempts were made to cross-link between aTMH5 and cTMH2 at the periplasmic side of the membrane. A total of 10 mutants were tested. No cross-linking was achieved from aW241C to cV68C, cG71C, cV74C, cM75C, cF76C, cA77C, and cV78C (Table 1). In addition no cross-linking was achieved from aF244C to cV68C, cY73C, and cF76C (Table 1). A possible reason for these negative results is inaccessibility to these residues to the bis-MTS reagents. In support of this possibility, the Cu2+-catalyzed cross-linkable pairs aL224C/cY73C, aI225C/cL72C, and aI225C/cY73C identified previously (22) between aTMH4 and cTMH2 at the periplasmic side of the membrane were also resistant to forming dimers when treated with the M2M, M3M, M4M, and M6M linkers (data not shown). However, the 10 Cys pairs constructed here at the periplasmic side of aTMH5 and cTMH2 proved to be resistant to cross-linking with Cu2+ at pH 8.5 (data not shown), so factors other than aqueous access may be responsible for the negative results.

pH-dependent Cross-links—As previously mentioned, the position of residue 252 in subunit a is of functionally significance because loss of the essential aArg-210 residue in aTMH4 can be compensated in the double mutant suppressor strain aR210Q/Q252R (16, 23). To investigate the proximity of aGln-252 to cAsp-61, Cys mutants were constructed to test cross-linking between aQ252C and cL59C, cV60C, cA62C, cI63C, or cM65C. Cross-linking proved possible for two of the five mutant combinations.

The aQ252C/cA62C double Cys mutant cross-linked with M2M, M3M, and M4M linkers (Fig. 7A). When the pH was varied, treatment with the M2M linker generated noticeably more a–c dimer when the pH was lowered from 8.5 to 6.5 (Fig. 7A). A similar effect was seen with the M3M and M4M reagent (Fig. 7A). The increase in cross-linking at acidic pH was unusual in that, with the exception of the aL251C/cM57C and aL251C/cL59C pairs, other positive cross-linkable Cys pairs had shown no pH dependence with respect to cross-linking (Figs. 2 and 5). The aQ252C/cM65C double Cys mutant cross-linked with moderate product formation with the M2M and M4M reagents and greater than 75% product formation with the M6M reagent (Fig. 7B). As with the aQ252C/cA62C pair, product formation was increased when the pH was decreased from 8.5 to 6.5 (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

pH-dependent cross-link formation between Cys at position 252 in subunit a and positions 62 and 65 in subunit c with bis-MTS reagents. Membranes were treated and electrophoresis and Western blotting were carried out as described in the legend to Fig. 2. A, aQ252C/cA62C; and B, aQ252C/cM65C.

Because the bis-MTS reagents react exclusively with the thiolate form of the Cys side chain, the cross-linked products shown in Fig. 7 would have been expected to decrease rather than increase at the lower pH. A possible explanation is that at acidic pH, aL251C and aQ252C of aTMH5 assume a position that is in closer proximity to cTMH2, which would allow for more efficient cross-linking at the lower pH values. To further investigate this and test a possible swiveling of the helix toward cTMH2, cross-linking was attempted between aY263C and cR50C, cQ51C, cF53C, cF54C, cI55C, or cV56C. The aTyr-263 residue was chosen based on its placement at the interior of the proposed four-helical bundle of subunit a along with aGln-52 (21). Positive cross-links between aY263C and any subunit c residue might also be sensitive to a conformational change brought about by lowering the pH. Of the 6 mutants tested, only the aY263C/cF54C double Cys mutant demonstrated positive cross-linking with the M2M, M4M, and M6M cross-linkers (Fig. 8). The amount of cross-linked product increased as the pH was decreased from 8.5 to 6.5. The increase in cross-link formation at pH 6.5 was consistently most apparent for the M4M cross-linker, with only minor differences being seen in the extent of cross-linking with M2M and M6M (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

pH-dependent cross-link formation between Cys at position 263 in subunit a and position 54 in subunit c with bis-MTS reagents. aY263C/cF54C membranes were treated and electrophoresis and Western blotting was carried out as described in the legend to Fig. 2.

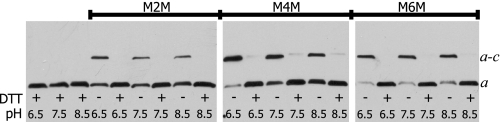

aTMH4 and aTMH5 Can Be Cross-linked to Different Monomers—Preliminary modeling of the cross-links identified in this study and in Jiang and Fillingame (22) suggested that aTMH4 and aTMH5 could be cross-linking to different subunit c monomers. The possibility that different subunit c monomers could be cross-linked to aTMH4 and aTMH5 was tested by combining cross-linkable pairs from aTMH4 to cTMH2 and from aTMH5 to cTMH2 in a single mutant strain and then testing for c—a–c trimer formation. A quadruple Cys mutant was generated that combines cross-linkable residues aL224C/cY73C, which cross-links with Cu2+ (22), and cross-linkable residues aV262C/cF54C, which cross-links with the bis-MTS reagents as shown above. These cross-links occur at the periplasmic and cytoplasmic sides of the membrane, respectively. When this quadruple Cys mutant was treated with Cu2+, dimers were formed that were reduced upon the addition of βMSH (Fig. 9A). When mutant membranes were treated with M3M, the predicted a–c dimer was formed along with a minor amount of a second band that is identified as a c–a–c trimer in additional experiments below (Fig. 9B). Both the dimer and trimer complexes were reduced upon the addition of βMSH (Fig. 9A). When mutant membranes were treated sequentially with M3M and then Cu2+, extensive c—a–c trimer formation was observed with the simultaneous disappearance of the a–c dimers (Fig. 9A). The presence of subunit a and subunit c in the cross-linked bands was verified by purifying the His-tagged subunit a, a— c, and c—a–c products before and after cross-linking (Fig. 9B). Antisera to both subunits a and c were used to visualize the individual subunits and the a–c and c—a–c products. The a–c product was consistently detected more readily by the anti-a versus anti-c antibodies in this and other experiments. These experiments demonstrate that aTMH4 and aTMH5 can be cross-linked to two different subunit c monomers.

FIGURE 9.

A c—a–c trimer is formed by sequential treatment with M3M and Cu2+. A, membranes of the aL224C/cF54C and aV262C/cY73C quadruple mutant were treated with Cu2+, M3M, or both M3M and Cu2+ to catalyze cross-link formation. B, the His-tagged subunit a, a–c, or c—a–c products were purified as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A single gel was run with duplicate loading of samples to probe with both subunit a antibody and subunit c antibody as described in the legend to Fig. 3.

Function of Cross-linkable Double Cys Mutants—The mutations used here could disrupt native structure, and if so, the cross-linking results described above would have to be evaluated with that consideration. The functional capacities of mutants showing positive cross-linking were assayed by measuring the growth yield in glucose minimal liquid medium, colony sizes on succinate minimal medium agar plates, and the ATP-driven H+-pumping capacity (Table 3). Each of the doubly Cys substituted mutants grew on succinate minimal medium agar plates within the range of colony sizes seen for the singly substituted Cys mutants (20, 22, 27), i.e. 1.4–3.0 mm. Of the 12 double Cys mutants analyzed, 7 demonstrated growth yields on glucose that were ≥95% relative to wild type. Five mutants showed significantly lower growth yields. The capacity of each double Cys F1F0 to pump protons was assayed by ATP-driven quenching 9-amino-6-chloro-2-methoxyacridine fluorescence. Of the 12 Cys mutants showing positive cross-linking, 9 mutants demonstrated relatively robust quenching responses in the range of the component singly substituted Cys (34–74%). Three double Cys mutants showed significantly reduced quenching responses in the range of 10–12%. The quadruple Cys mutant composed of cross-linkable pairs aL224C/cY73C with aV262C/cF54C formed small colonies of <0.1 mm on succinate and grew with a growth yield on glucose that was comparable with the unc deletion strain JWP292. The quadruple Cys mutant showed a negligible quenching response of ≤5%. The lack of function in this mutant could be due to a structural perturbation, or to the cumulative effects of the four Cys substitutions, each of which by themselves cause minor loss of function.

TABLE 3.

Properties of subunit a and subunit c double Cys substitutions

| a/c Mutation | Growth yield on glucosea | Growth on succinateb | % Quenching with ATPc |

|---|---|---|---|

| mm | |||

| Wild type | 100 | 2.0–2.5 | 86 ± 3 |

| aI248C/cA62C | 100 | 2.2–3.0 | 65 ± 2 |

| aI248C/cI63C | 102 | 2.2–3.0 | 74 ± 1 |

| aI248C/cM65C | 81 | 1.8–2.0 | 51 ± 2 |

| aL251C/cM57C | 83 | 2.0–2.4 | 45 ± 7 |

| aL251C/cL59C | 71 | 1.5–2.0 | 35 ± 5 |

| aL251C/cA62C | 103 | 2.2–3.0 | 63 ± 6 |

| aQ252C | 92 | 1.8±2.2 | 54 ± 7 |

| aQ252C/cA62C | 77 | 1.5–2.0 | 12 ± 3 |

| aQ252C/cM65C | 68 | 1.4–1.8 | 11 ± 3 |

| aV262C/cF53C | 97 | 2.0–3.0 | 72 ± 2 |

| aV262C/cF54C | 96 | 2.0–3.0 | 34 ± 7 |

| aV262C/cI55C | 97 | 2.2–3.0 | 11 ± 2 |

| aY263C/cF54C | 95 | 2.0–2.4 | 34 ± 1 |

| aL224C/cY73C/ aY263C/cF54C | 60 | <0.1 | ≤5 |

Growth yield in liquid minimal media containing 0.04% glucose, expressed as a percentage of growth relative to the cysteine-less control. The values given are the average of two or more determinations. The growth yield of the unc deletion strain JWP292 was 59%

Colony size after incubation for 72 h on minimal medium plates containing 22 mm succinate. Colonies from the cysteine-less control strain show average colony sizes of 2.2 ± 0.3 mm

Membranes were diluted to 1 mg/ml in 10 mm Hepes-KOH, pH 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2, 300 mm KCl for assay. The values given are the relative quenching 9-amino-6-chloro-2-methoxyacridine fluorescence following addition of ATP (±S.D. for two or more determinations)

DISCUSSION

Prior to this study, we reported that aTMH4 could be cross-linked to cTMH2 via Cu2+-catalyzed disulfide bond formation over a span of 19 amino acids, which suggested that these helices packed in close proximity and possibly in parallel to each other (22). Zero-length cross-links generated with Cu2+ were also used to define the packing of TMHs 2–5 of subunit a in what is likely a four-helix bundle (21). A model has been proposed placing the aTMH 2–5 four-helix bundle at the periphery of the c-ring with cTMH2 next to aTMH4, which suggested a possible close proximity of aTMH5 and cTMH2 (18). Such a proximity was supported by the function of the aR210Q/Q252R double mutant where the essential Arg of subunit a was exchanged between aTMH4 and aTMH5. The essential Arg is thought to interact with Asp-61 of cTMH2 during proton translocation. Despite the likely proximity, attempts to cross-link 32 pairs of Cys between aTMH5 and cTMH2 with Cu2+ were unsuccessful.3 In this study, we have used bis-MTS reagents to increase the distance and flexibility of a potential cross-link and have demonstrated cross-linking between aTMH5 and cTMH2 for 12 double Cys pairs. The specificity of cross-linking is demonstrated by the 50 pairs of Cys in neighboring residues that do not cross-link (Table 1). Nearly 100% cross-linking was obtained with various linkers for aI248C/cA62C, aI248C/cI63C, and aI248C/cM65C in the middle of the membrane and aV262C/cF54C and aV262C/cI55C at the cytoplasmic side of the membrane (Table 2). Slightly less efficient cross-linking was observed with the aL251C/cL59C, and aL251C/cA62C pairs at the center of the membrane and the aV262C/cF53C pair at the cytoplasmic surface (Table 2). The aV262C/cI55C mutant also formed dimers when treated with Cu2+, whereas the other 11 cross-linkable pairs did not.

Several of the Cys pairs showed increasing cross-linking as the length of the linker was increased, e.g. aI248C/cI63C (Table 2), which is consistent with the side chains packing at a distance greater than that required for zero-length cross-linking with Cu2+. The aL251C/cM57C, aL251C/cL59C, and aL251C/cA62C pairs were unusual in that cross-linking occurred most efficiently with the smallest cross-linkers, suggesting that the space between side chains may limit access of the cross-linking agent.

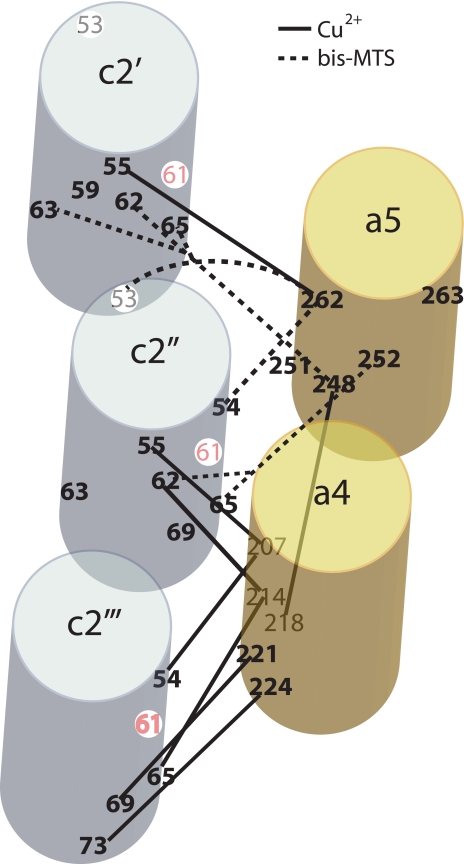

The structural modeling of the cross-linkable residues identified in this study and in Jiang and Fillingame (22) proves to be somewhat ambiguous because many cross-links could be depicted as occurring between aTMH4 or aTMH5 and two possible cTMH2s in the c-ring (Fig. 10). For example, Cys at positions 248 or 252 in aTMH5 could cross-link to Cys at positions 62 or 65 in either the c2′ or c2″ subunits shown in Fig. 10. On the other hand, the aI248C/cI63C cross-link seems much more probable with c2′ than with c2″. An attempt to limit the number of possible models that could be generated was made by combining cross-linkable pairs from aTMH4 to cTMH2 and from aTMH5 to cTMH2 in a quadruple Cys mutant. The Cys pairs aL224C/cY73C and aV262C/cF54C cross-link specifically with Cu2+ and bis-MTS reagents, respectively, to cause a–c dimer formation. When membranes were treated sequentially with both reagents, two cross-links were formed from subunit a to two separate subunit c monomers generating a c–a–c trimer. This verified that aTMH4 and aTMH5 can cross-link to different subunit c monomers. A possible model consistent with these results is shown in Fig. 10 where aTMH4 cross-links with the c2″ and the c2′″ subunits and aTMH5 within the same subunit a cross-links with the c2′ and c2″ subunits. The model needs to be considered with caution because the quadruple mutant used in direct support proved to be non-functional, and the loss of function therein could result from disruption of the normal a–c structural interaction.

FIGURE 10.

Schematic representation of TMH4 and TMH5 of subunit a docked next to three copies of TMH2 of subunit c based on available cross-linking data. aTMH4 and aTMH5 (yellow cylinders) were placed next to three identically oriented copies of cTMH2, the cTMH2 orientation being based upon the I. tartaricus x-ray structure (7). Residues involved in cross-linking in this study and Jiang and Fillingame (22) are indicated. The schematic illustrates how the helices might pack next to subunit c and indicate one possible means by which aTMH5 and aTMH4 interact with different cTMH2s. The helices are assumed to pack in parallel. aTMH4 and aTMH5 are oriented relative to each other based upon the aG218C/I248C zero-length cross-link catalyzed by Cu2+-phenanthroline (21).

Five cross-linkable Cys pairs, i.e. aL251C/cM57C, aL251C/cL59C, aQ252C/cA62C, aQ252C/cM65C, and aY263C/cF54C, showed pH-dependent cross-linking where cross-link formation was increased by decreasing the pH from 8.5 to 6.5. This pH dependence was opposite to expectations because one would predict that cross-linking should decrease at more acid pH because the Cys thiolate is the reactive species (24). For the other seven Cys pairs, cross-linking did not change over the range of pH 6.5–8.5 (Figs. 2 and 5, and data not shown for the aL251C/cA62C, aV262C/cF53C, and aV262C/cF54C Cys pairs). All of the pH-dependent, cross-linkable mutants exhibited at least partial function as reflected by growth on glucose and succinate carbon sources and by ATP-driven H+-pumping, although function did vary considerably (Table 3). The retention of partial function in these mutants suggests that the key structural interactions at the subunit a–c interface of these mutants are likely to be largely preserved.

We have suggested previously that TMHs 4 and 5 may rotate in response to acidification of the periplasmic half-channel that is thought to be located at the center of the four-helix bundle of TMHs 2–5 (14, 19–21). The movements were proposed as part of a gating mechanism to allow for protonation of the cAsp-61 from the periplasm during proton translocation. During ATP synthesis, Asp-61 in cTMH2 must sequentially undergo protonation and deprotonation. Arg-210 in aTMH4 is proposed to interact with cAsp-61 to lower its pKa to promote proton release. Following deprotonation, all or part of aTMH4 could rotate counterclockwise to move aArg-210 away from cAsp-61 to facilitate its reprotonation, and with the simultaneous rotation of aTMH5 clockwise, gate access to protons at the interior of the four-helix bundle to facilitate reprotonation from the periplasm. Based upon the model shown in Fig. 10, a clockwise rotation of aTMH5 would bring aGln-52 and aTyr-263 closer to cTMH2. This could explain why cross-linking is increased in the mutants involving these residues when the pH is lowered. A local pH change at the interior of the four-helix bundle on the reduction of the medium pH from 8.5 to 6.5 could cause aTMH5 to rotate as postulated from other studies (14, 20).

Acknowledgments

We thank Hun Sun Chung for assistance in some of the experiments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM23105. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: TMH, transmembrane helix; bis-MTS, bis-methanethiosulfonate; βMSH, β-mercaptoethanol; M2M, 1,2-ethanediyl bis-MTS; M3M, 1,3-propanediyl bis-MTS; M4M, 1,4-butanediyl bis-MTS; M6M, 1,6-hexanediyl bis-MTS; PVDF, polyvinylidene difluoride; DTT, dithiothreitol; NEM, N-ethylmaleimide; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

B. E. Schwem and R. H. Fillingame, unpublished data.

B. E. Schwem, unpublished data.

References

- 1.Yoshida, M., Muneyuki, E., and Hisabori, T. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2 669-677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capaldi, R. A., and Aggeler, R. (2002) Trends Biochem. Sci. 27 154-160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimroth, P., von Ballmoos, C., and Meier, T. (2006) EMBO Rep. 7 276-282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Senior, A. E. (1988) Physiol. Rev. 68 177-231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang, W., Hermolin, J., and Fillingame, R. H. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 4966-4971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitome, N., Suzuki, T., Hayashi, S., and Yoshida, M. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 12159-12164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meier, T., Polzer, P., Diederichs, K., Welte, W., and Dimroth, P. (2005) Science 308 659-662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pogoryelov, D., Yu, J., Meier, T., Vonck, J., Dimroth, P., and Muller, D. J. (2005) EMBO Rep. 6 1040-1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones, P. C., Jiang, W., and Fillingame, R. H. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 17178-17185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dmitriev, O. Y., Jones, P. C., and Fillingame, R. H. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 7785-7790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valiyaveetil, F. I., and Fillingame, R. H. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 16241-16247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long, J. C., Wang, S., and Vik, S. B. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 16235-16240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wada, T., Long, J. C., Zhang, D., and Vik, S. B. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 17353-17357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fillingame, R. H., Angevine, C. M., and Dmitriev, O. Y. (2003) FEBS Lett. 555 29-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cain, B. D. (2000) J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 32 365-371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatch, L. P., Cox, G. B., and Howitt, S. M. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 29407-29412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valiyaveetil, F. I., and Fillingame, R. H. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 32635-32641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angevine, C. M., and Fillingame, R. H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 6066-6074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angevine, C. M., Herold, K. A., and Fillingame, R. H. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 13179-13183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angevine, C. M., Herold, K. A., Vincent, O. D., and Fillingame, R. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 9001-9007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwem, B. E., and Fillingame, R. H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 37861-37867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang, W., and Fillingame, R. H. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95 6607-6612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishmukhametov, R. R., Pond, J. B., Al-Huqail, A., Galkin, M. A., and Vik, S. B. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777 32-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roberts, D. D., Lewis, S. D., Ballou, D. P., Olson, S. T., and Shafer, J. A. (1986) Biochemistry 25 5595-5601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loo, T. W., and Clarke, D. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 36877-36880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barik, S. (1996) Methods Mol. Biol. 57 203-215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steed, P. R., and Fillingame, R. H. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 12365-12372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosher, M. E., White, L. K., Hermolin, J., and Fillingame, R. H. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260 4807-4814 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Towbin, H., Staehelin, T., and Gordon, J. (1979) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 76 4350-4354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hermolin, J., and Fillingame, R. H. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 2815-2817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]