Abstract

Translocations in chromosomes alter genetic information. Although the frequent translocations observed in many tumors suggest the altered genetic information by translocation could promote tumorigenesis, the mechanisms for how translocations are suppressed and produced are poorly understood. The smc6-9 mutation increased the translocation class gross chromosomal rearrangement (GCR). Translocations produced in the smc6-9 strain are unique because they are non-reciprocal and dependent on break-induced replication (BIR) and independent of non-homologous end joining. The high incidence of translocations near repetitive sequences such as δ sequences, ARS, tRNA genes, and telomeres in the smc6-9 strain indicates that Smc5-Smc6 suppresses translocations by reducing DNA damage at repetitive sequences. Synergistic enhancements of translocations in strains defective in DNA damage checkpoints by the smc6-9 mutation without affecting de novo telomere addition class GCR suggest that Smc5-Smc6 defines a new pathway to suppress GCR formation.

Keywords: Smc5-6, Gross chromosomal rearrangement, Break-induced replication, checkpoints, translocations

1. Introduction

Cancer is a genetic disorder requiring multiple mutations across the entire genome. Widespread genomic mutations can be facilitated by a mutation that affects key processes related to DNA metabolisms such as DNA replication, repair, and recombination. Such mutations are sometimes referred to as “mutator mutations” to reflect their ability to enhance mutation rates [1,2]. One of the most common alterations in the genomes of cancer cells is the alteration of normal chromosome size, often referred to as gross chromosomal rearrangements (GCRs). GCR arises through defects in the repair of DNA damage caused either by internal sources, such as defects in DNA replication and telomere erosion, or by exposure to exogenous toxic agents [1]. Recent progress in identification of genes responsible for cancer susceptible syndromes and studies of animal models has begun to reveal the importance of GCR during carcinogenesis [1,3].

To study GCR in more tractable way, the chromosome V GCR assay that can detect interstitial deletions or non-reciprocal translocations with micro-homology, non-homology, or divergent homology (referred as homeology) at the rearrangement breakpoint, chromosome fusions as well as deletion of a chromosome arm with addition of a new telomere referred to de novo telomere addition was developed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [4-6]. Studies using this GCR assay have begun to elucidate mechanisms underlying GCR formation [1,5]. Several studies using this approach have demonstrated that there are eight pathways for suppressing these chromosomal aberrations, while six pathways promote GCR formation. The suppression mechanisms include cell cycle checkpoints [7-12], post-replication [13,14] and mismatch repair [15,16], recombination pathways, an anti-de novo telomere addition mechanism [17,18], chromatin assembly factors [11,19], mechanisms that prevent end-to-end chromosome fusions [17,18,20] and a pathway detoxifying reactive oxygen species [14,21,22]. In contrast, the promoters of GCRs include telomerase-related factors [17,23], a mitotic checkpoint network [24], the Rad1-Rad10 endonuclease [25], non-homologous end-joining proteins including Lig4 and Nej1 [17], a pathway generating inappropriate recombination via sumoylation and the Srs2 helicase [13] and the Bre1 ubiquitin ligase [13].

Eukaryotic cells have three protein complexes containing chromosomal ATPases of the Structural Maintenance of Chromosomes (SMC) family that function in various aspects of chromosome metabolism [26-29]. SMC complexes are characterized by the presence of a heterodimer of Smc proteins at the core with additional non-Smc subunits. The Smc complexes include cohesin, with the Smc1-Smc3 dimer, to provide sister-chromatid cohesion, condensin, with the Smc2-Smc4 dimer, important to mediate mitotic chromosome condensation, and the Smc5-Smc6 complex, with roles in DNA repair [27,30]. Although the main role of the Smc5-Smc6 complex is still unclear, recent studies have shown that this complex is recruited to the induced DNA double-strand-breaks (DSBs) [31,32] to enhance their repair by sister-chromatid recombination [31,32]. Smc5-6 heterodimer makes a multi-protein complex with six additional subunits in budding yeast (Nse1-6) [28]. Nse2 also known as Mms21 is an E3 SUMO ligase and several studies suggested that Mms21 links Smc5-6 to DNA repair role through sumoylation [33,34].

Temperature-sensitive mutants of Smc6 have been shown to affect the stability of repetitive sequences in budding yeast by influencing their repair [35,36]. These observations have been recently extended to human cells, where the Smc5-Smc6 complex has been shown to play a role in alternative lengthening of telomeres ALT pathways, which are mediated by homologous recombination events [37].

Recently, we reported that a conditional allele of SMC6 in budding yeast, smc6-9 increased GCR rate in a HR dependent manner [31]. In the present study, we further examined how GCR formation by the smc6-9 mutation interacts with other known GCR pathways. Smc5-Smc6 complex suppresses translocation class GCRs dependent on break-induced replication (BIR) that is different from other non-homologous end joining dependent translocations observed in other GCR mutator strains. Furthermore, GCR rates in the smc6-9 strain were synergistically increased with mutations causing defects in cell cycle checkpoints and telomerase inhibition suggesting that the Smc5-Smc6 complex defines a novel pathway for suppression of translocation class GCRs. Interestingly, some of the GCR events in the smc6-9 strain occurred in close proximity to repetitive sequences, consistent with the known role of Smc5-Smc6 in the stability of repetitive genomic region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General genetic methods

Methods for the construction and propagation of gene-disrupted strains were described previously [10,14]. The sequences of primers used to generate gene-knockout cassettes and to confirm correct disruption are available upon request. All S. cerevisiae strains used in this study were derived from the S288c strain RDKY3615 [MATa, ura3-52, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63, his3Δ200, lys2ΔBgl, hom3-10, ade2Δ1, ade8, hxt13∷URA3]. Genotypes of each strain used for this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in this study.

| Strains | Relevant Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| RDKY3615 | Wild type | [4] |

| RDKY3633 | mre11∷TRP1 | [4] |

| RDKY3636 | rad51∷HIS3 | [4] |

| RDKY3639 | yku70∷TRP1 | [4] |

| RDKY3641 | lig4∷HIS3 | [17] |

| RDKY3719 | rad9∷HIS3 | [10] |

| RDKY3721 | rad17∷HIS3 | [10] |

| RDKY3723 | rad24∷HIS3 | [10] |

| RDKY3727 | rfc5-1 | [10] |

| RDKY3729 | pds1∷TRP1 | [10] |

| RDKY3731 | tel1∷HIS3 | [10] |

| RDKY3735 | sml1∷KAN, mec1∷HIS3 | [10] |

| RDKY3739 | dun1∷HIS3 | [10] |

| RDKY3745 | chk1∷HIS3 | [10] |

| RDKY3749 | sml1∷KAN rad53∷HIS3 | [10] |

| RDKY3814 | sgs1∷HIS3 | [15] |

| RDKY3815 | top3∷KAN | [15] |

| RDKY4224 | tlc1∷TRP1 | [17] |

| RDKY4343 | pif1-m2 | [17] |

| RDKY4347 | est2∷TRP1 | [17] |

| RDKY4421 | rad52∷HIS3 | [17] |

| RDKY4423 | rad59∷TRP1 | [17] |

| YKJM1385 | rad5∷HIS3 | [14] |

| YKJM1405 | elg1∷HIS3 | [14] |

| YKJM1560 | pol32∷TRP1 | [13] |

| YKJM2179 | siz1∷TRP1 | [13] |

| YKJM3088 | smc6-9 | This study |

| YKJM3539 | nse3-2 | This study |

| YKJM3091 | pif1-m2 smc6-9 | This study |

| YKJM3115 | smc6-9 elg1∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3117 | smc6-9 pds1∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3118 | smc6-9 lig4∷KAN | This study |

| YKJM3134 | smc6-9 chk1∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3136 | smc6-9 dun1∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3787 | smc6-9 est1∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3137 | smc6-9 est2∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3788 | smc6-9 est3∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3139 | smc6-9 rad5∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3141 | smc6-9 rad51∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3143 | smc6-9 tlc1∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3146 | smc6-9 sml1∷KAN mec1∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3203 | smc6-9 mre11∷KAN | This study |

| YKJM3207 | smc6-9 rad52∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3575 | smc6-9 ddc1∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3576 | smc6-9 yku70∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3611 | smc6-9 tel1∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3612 | smc6-9 sgs1∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3622 | smc6-9 siz1∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3626 | smc6-9 rad24∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3758 | pif1-m2 nse3-2 | This study |

| YKJM3760 | ddc1∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3767 | smc6-9 rad59∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3796 | smc6-9 rad9∷KAN | This study |

| YKJM3816 | smc6-9 sml1∷KAN rad53∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3819 | smc6-9 rfc5-1 | This study |

| YKJM3825 | smc6-9 rad17∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM3833 | smc6-9 top3∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM5039 | siz2∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM5041 | smc6-9 siz2∷TRP1 | This study |

| YKJM5057 | mms21-11 | This study |

| YKJM5061 | smc6-9 mms21-11 | This study |

| YKJM5063 | smc6-9 pol32∷KAN | This study |

| YJL092 | Wild type for BIR assay | [40] |

| YKJM5044 | smc6-9 for BIR assay | This study |

All strains used for GCR assay are isogenic to RDKY3615 [ura3-52, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63, his3Δ200, lys2ΔBgl, hom3-10, ade2Δ1, ade8, YEL069∷URA3]. Strains used for BIR assay are isogenic to JL092 [mata∷HOcsΔ∷hisG ura3Δ851 trp1Δ63 sup53Δ∷leu2ΔKANMX hmlΔ∷hisG HMRa-stk ade3∷GAL10∷HO can1, 1-1446∷HOcs∷HPH∷ΔAVT2 ykl215c∷LEU2∷can1Δ1-289].

2.2. Characterization of spontaneous GCR rates and chromosomal breakpoints

All GCR rates were determined by fluctuation analysis using the method of the median with at least two independent clones [5,38]. The average GCR rates from at least two or more independent experiments using either 5 or 11 cultures for each strain are reported as previously described [10,14]. The sequences of breakpoints from mutants carrying GCR were determined as described [10,14].

2.3. Pulse Field Gel Electrophoresis

Genomic DNA samples were prepared in low melting agarose plugs containing 5×107 cells as described [39]. The plugs were inserted in a 1% agarose-TBE gel and chromosomes were separated by pulse field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) CHEF II DR system (BioRad). Electrophoresis was performed for 30 hours at 180V with 120 seconds pulses in 0.5× TBE at 14 °C. The gel was then stained for 30 minutes with 0.5μg/ml ethidium bromide and visualized using a UV illuminator.

2.4. Break-induced replication (BIR) assay

BIR assay was performed following exactly same procedures as previously described [40]. Briefly, exponentially growing yeast cells in yeast-peptone (YP) with 2% succinic acid and 1% glycerol were plated on YP with 2% glucose or YP with 2% galactose and incubated for two days until visible colonies were grown. After counting numbers of colonies, yeast cells were replica plated on plates having canavanine or hygromycin. The percentage of cells repairing by BIR was calculated by the number of colonies sensitive to canavanie and hygromycine on YP-galactose plate divided by the number of colonies resistant to canavanine and hygromycine on YP-glucose plate.

3. Results

3.1. Translocations by break-induced replications (BIR) are preferentially generated by the smc6-9 mutation

The impaired chromosome segregation of repetitive DNA sequences such as rDNA or telomeres was observed by defects in the Smc5-Smc6 complex [35,41]. Some of these defects due to incorrect repair during the G2/M phases likely cause an increase in spontaneous double strand breaks (DSBs) [36]. To further gain an insight into the mechanisms of GCR formation when the Smc5-Smc6 complex is impaired, we measured GCR rates in strains defective in different subunits of Smc5-6 complex. The smc6-9, nse3-2, or mms21-11 mutation increased the GCR rate 76, 54, or 80 fold compared to wild type, respectively (Table 2). The strain having both smc6-9 and mms21-11 mutations increased the GCR rate similar to strains with each mutation (Table 2 footnote).

Table 2.

The impairment of Smc5-Smc6 increased the GCR rates

| Relevant genotype | Wild type | |

|---|---|---|

| Strain | Mutation rate

(Canr 5-FOAr) |

|

| Wild type | RDKY3615 | 3.5×10-10 (1) |

| smc6-9 | YKJM3088 | 2.7×10-8 (76) |

| nse3-2 | YKJM3539 | 1.9×10-8 (54) |

| mms21-11 | YKJM5057 | 2.8×10-8 (80) |

All strains are isogenic with the wild type strain, RDKY3615 [ura3-52, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63, his3Δ200, lys2ΔBgl, hom3-10, ade2Δ1, ade8, YEL069∷URA3] with the exception of the indicated mutations. The GCR rate of strain having both smc6-9 and mms21-11 (YKJM5061) was 2.9×10-8 (83). The numbers in parenthesis indicate the fold induction of GCR rate relative to wild type GCR rate. Canr 5-FOAr indicates resistant to canavanine and 5-FOA.

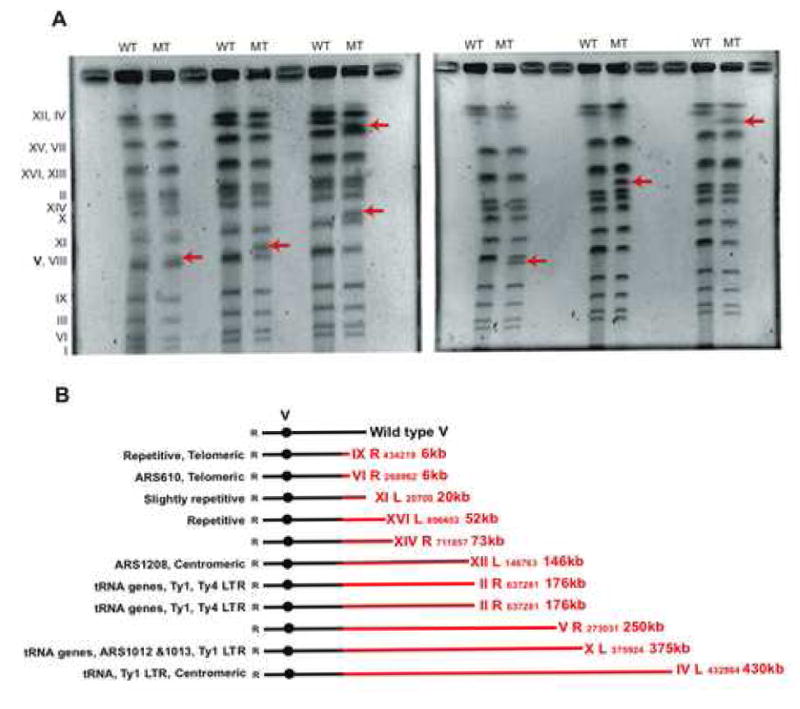

Breakpoint junctions often leave signatures of GCRs that suggest putative mechanism of GCR formation. We determined breakpoint junction structures of GCRs from fifteen independent clones came from the smc6-9 strain (Table 3 and Fig. 1). The smc6-9 mutation mainly generated translocations having micro-homology signatures at the breakpoint junction (67% of total break point junction analyzed) compared to wild-type cells, which preferentially produced terminal deletion with de novo telomere addition class GCR in the chromosome V GCR assay used in this study. To determine the nature of translocations generated by the smc6-9 mutation, we further investigated these rearrangements by PFGE (Fig. 1). Yeast chromosomes VIII and V are very similar in size and difficult to resolve by PFGE making the visualization of chromosome V loss, where the GCR assay resides problematic. Nevertheless, chromosomes from the clones carrying a GCR collected from the smc6-9 strain exhibited the appearance of a new sized chromosome except in one case, (third mutant clone in Fig. 1A) which had two new sized chromosomes (Fig. 1A).

Table 3.

GCR breakpoint spectra in different mutant strains

| Relevant genotype | Strain | Telomere addition | Translocation | Chromosome fusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-homology | Micro-homology | ||||

| Wild type | RDKY3615 | 12 (2.8×10-10) | 3 (7.0×10-11) | 0 | 0 |

| smc6-9 | YKJM3088 | 4 (7.2×10-9) | 1 (1.8×10-9) | 10 (1.8×10-8) | 0 |

| lig4Δ2 | RDKY3641 | 6 (1.6×10-9) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| smc6-9 lig4Δ | YKJM3118 | 2 (1.7×10-8) | 2 (1.7×10-8) | 73 (5.9×10-8) | 0 |

| smc6-9 yku70Δ | YKJM3576 | 2 (7.0×10-9) | 1 (3.5×10-9) | 6 (2.1×10-8) | 1 (3.5×10-9) |

| rad52Δ2 | RDKY4421 | 3 (1.1×10-8) | 0 | 7 (2.5×10-8) | 0 |

| smc6-9 rad52Δ | YKJM3207 | 9 (1.1×10-9) | 0 | 1 (6.0×10-10) | 0 |

| smc6-9 pol32Δ | YKJM5063 | 6 (3.2×10-8) | 4 (2.2×10-8) | 0 | 0 |

| mec1Δ1 | RDKY3735 | 9 (4.6×10-8) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| smc6-9 mec1Δ | YKJM3146 | 4 (5.3×10-8) | 0 | 5 (6.7×10-8) | 0 |

| tel1Δ1 | RDKY3731 | 0 | 0 | 6 (2.0×10-10) | 0 |

| smc6-9 tel1Δ | YKJM3611 | 2 (7.5×10-8) | 4 (1.5×10-7) | 5 (1.9×10-7) | 0 |

| pif1-m22 | RDKY4343 | 17 (4.8×10-8) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| smc6-9 pif1-m2 | YKJM3090 | 12 (5.4×10-7) | 0 | 2 (9.0×10-9) | 0 |

| tlc1Δ | YKJM3137 | 1 (2.8×10-11) | 0 | 2 (5.6×10-11) | 8 (1.1×10-10) |

| smc6-9 est2Δ | YKJM3137 | 0 | 2 (2.6×10-8) | 6 (7.8×10-8) | 2 (2.6×10-8) |

| smc6-9 tlc1Δ | YKJM3143 | 1 (2.9×10-8) | 2 (5.8×10-8) | 4 (1.7×10-7) | 4 (1.7×10-7) |

The number of individual GCR structures from different strains is presented. The rate in the parenthesis is calculated by dividing the GCR rates observed in Table 2, 4, 5, and 6 with different GCR types observed. 1. Data from [10]. 2. Data from [17]. 3. One translocation event with vector sequences.

Fig. 1.

GCRs in the smc6-9 strain are mainly non-reciprocal translocations through the break-induced replication mechanism. (A) Chromosomes from six independent clones were separated by PFGE. Arrows indicate new size chromosomes only observed in mutant clones carrying GCR. Roman numbers in the left side of gel indicate Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome numbers. WT and MT are wild type and mutant clone carrying GCR, respectively. (B) Graphic presentations of translocated chromosomes observed in the smc6-9 strain. Red colored line represents chromosomes translocated into broken chromosome V, drawn as black line. Black circle represents the centromere of chromosome V. Roman numbers represent the number of chromosome translocated. Following R and L represent right and left arm of chromosome translocated. The numbers followed represent the starting nucleotide position of translocated chromosome and size (kb) increased after translocation. The coordinates of nucleotide positions were based on the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD: http://www.yeastgenome.org/).

The chromosome translocated to chromosome V in each case was determined by linker-mediated PCR as previously described [14]. The sizes of the new chromosomes observed by PFGE matched the expected size obtained by adding the size of the broken chromosome V and the size of the translocated chromosome from the breakpoint to its end (Fig. 1B). In addition, even though there was a change in the size of chromosome V, it did not affect the electrophoretic mobility of the donor chromosomes suggesting all translocations were non-reciprocal translocations. The appearance of a new sized chromosome can only be explained through break-induced replication (BIR), where a DSB is repaired by undergoing recombination-dependent DNA replication with the re-establisment of a unidirectional replication fork that proceeds to the end of the chromosome or until it meets a converging fork [42]. Therefore, most major translocations in the smc6-9 strain seem to be produced by BIR.

3.2. Translocations produced in the smc6-9 strain are dependent on homologous recombination (HR) and independent of non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)

The rad52, rfa1-t33, or mre11 mutation also enhanced translocation types of GCRs. However, translocations in these mutator strains are largely dependent on the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) proteins, Lig4-Nej1-yKu70-yKu80 [17]. In contrast, translocations observed in the smc6-9 strain exhibited different genetic interactions (Table 3 and 4). The smc6-9 lig4 strain showed more than three-fold increase in GCR rate compared to the smc6-9 strain (Table 4). When we investigated the class of GCR in the smc6-9 lig4 strain, the rates of translocations carrying both non- and micro-homology at the breakpoint junction were enhanced (Table 3), thus confirming that the lig4 mutation did not suppress any types of GCR formation in the smc6-9 strain. We also investigated the effect of yku70 mutation on the GCR rate and class in the smc6-9 strain. Deletion of yku70 has been shown to inhibit de novo telomere addition as well as NHEJ-dependent translocations [17]. Similar to the lig4 mutation, the yku70 mutation in the smc6-9 strain did not change substantially either the rate or the type of GCR events (Table 3 and 4). These results again confirm that translocations in the smc6-9 strain do not require the NHEJ machinery.

Table 4.

The GCR formation enhanced by the smc6-9 mutation requires Rad51-dependent BIR, while it is synergistically increased with defects in NHEJ or Rad59-dependent HR

| Relevant genotype | Wild type | smc6-9 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Mutation rate

(Canr 5-FOAr) |

Strain | Mutation rate

(Canr 5-FOAr) |

|

| Wild type | RDKY3615 | 3.5×10-10 (1) | YKJM3088 | 2.7×10-8 (76) |

| lig4Δ | RDKY3641 | 1.6×10-9 (5) | YKJM3118 | 9.3×10-8 (265) |

| yku70Δ | RDKY3639 | 4.1×10-10 (1) | YKJM3576 | 3.5×10-8 (100) |

| rad52Δ | RDKY4421 | 3.5×10-8 (100) | YKJM3207 | 6.0×10-9 (17) |

| rad51Δ | RDKY3636 | 3.5×10-9 (10) | YKJM3141 | 3.7×10-9 (11) |

| rad59Δ | RDKY4423 | 7.5×10-9 (21) | YKJM3767 | 5.1×10-8 (145) |

| pol32Δ | RDKY4349 | 1.5×10-10 (0.4) | YKJM3788 | 1.1×10-7 (300) |

| siz1Δ | RDKY4345 | 1.5×10-10 (0.4) | YKJM3787 | 6.2×10-8 (177) |

| siz2Δ | RDKY4347 | 1.2×10-10 (0.3) | YKJM3137 | 1.2×10-7 (339) |

All strains are isogenic with the wild type strain, RDKY3615 [ura3-52, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63, his3Δ200, lys2ΔBgl, hom3-10, ade2Δ1, ade8, YEL069∷URA3] with the exception of the indicated mutations. The numbers in parenthesis indicate the fold induction of GCR rate relative to wild type GCR rate. Canr 5-FOAr indicates resistant to canavanine and 5-FOA.

BIR events are dependent on HR [42]. Since the GCRs observed in the smc6-9 strain are suspected to be BIR-induced translocations, they sould be dependent on the HR machinery. In budding yeast, there are two BIR pathways, both dependent on the recombination protein Rad52, but one of the pathways is Rad51-dependent whereas the other is Rad51-independent but requiring other recombination genes (besides Rad52) such as Rad59 [42]. To investigate whether translocations generated by the smc6-9 mutation are dependent on BIR, we tested whether GCR events in smc6-9 mutants indeed require Rad52. The GCR formation rates enhanced by the smc6-9 mutation was reduced five-folds by the rad52 mutation (Table 4). In addition, the micro-homology mediated translocations that are the major classes of GCRs found in the smc6-9 strain were almost absent in the smc6-9 rad52 strain (Table 3). Similarly, the rad51 mutation also suppressed GCR formation in the smc6-9 mutant background (Table 4). These results confirm that Rad51-dependent BIR is responsible for translocations produced in the smc6-9 strain. In addition, the mutation of the recombination gene RAD59 in smc6-9 mutants did not suppress GCR rates but on the contrary it showed an additive effect (Table 3), consistent with the fact that the Rad51-dependent BIR pathway promoted GCRs in the smc6-9 strain.

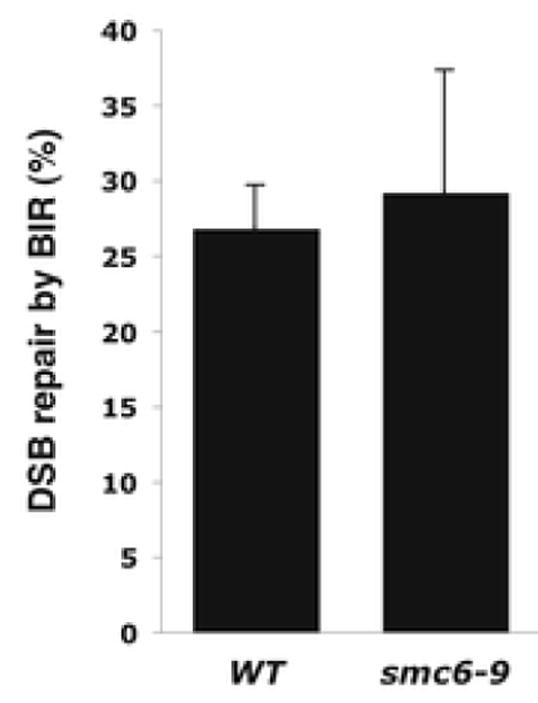

To determine whether the smc6-9 mutation affects the BIR efficiency, the BIR efficiency was measured by using the recently developed BIR assay [40]. The smc6-9 mutation did not show any significant difference in the BIR efficiency (Fig. 2). In addition, the additional pol32 mutation that abolishes almost all BIR [40] increased the GCR rate synergistically in the smc6-9 strain (Table 4). We hypothesized that the smc6-9 mutation would increase the appearance of DNA lesions that could become substrates for BIR-dependent GCR formation. In the absence of BIR, the same DNA lesions could become substrates for other pathway that will produce GCRs having different breakpoint junction signatures. To test this hypothesis, we determined the breakpoint structures of GCRs produced in the smc6-9 pol32 strain (Table 3). Consistent to our hypothesis, translocations having micro-homology at breakpoint junctions preferentially produced in the smc6-9 strain were not observed in the smc6-9 pol32 strain (Table 3). There were high increases of de novo telomere addition and translocations having non-homology at breakpoint junctions in GCRs from the smc6-9 pol32 strain. Therefore, the smc6-9 mutation seems to increase the appearance of DNA lesions at repetitive DNA sequences and BIR preferentially changes them to translocations with micro-homology signature at breakpoints.

Fig. 2.

Efficiency of BIR is not affected by the smc6-9 mutation. The BIR efficiency was measured by viability following a DSB.

The Rad52 protein is sumoylated largely by Siz2 [43] and PCNA sumoylation by Siz1 is important to promote GCR [13]. We asked whether GCRs enhanced by the smc6-9 mutation could be affected by the siz1 or siz2 mutation (Table 4). The siz1 or siz2 mutation synergistically increased GCR rates in the smc6-9 strain suggesting the Rad52 regulation by sumoylation could be important for suppression of GCR formation.

3.3. Inactivation of DNA damage checkpoints in the smc6-9 strain synergistically enhances GCR formation

The inactivation of the Smc5-Smc6 complex does not activate the DNA damage checkpoint [41]. Nevertheless, we questioned whether lack of checkpoint activity in smc6-9 mutants affects GCR formation. To test this question, different cell cycle checkpoint genes were disrupted in the smc6-9 strain and GCR rates were monitored. The smc6-9 strains carrying an additional mutation in sensors of the RAD24 branch DNA damage checkpoint such as rad24, rad17, or ddc1 [44], all increased the GCR rates synergistically compared to strains carrying each mutation (Table 5). An additional smc6-9 mutation in the rfc5-1 strain, which is defective in the DNA replication checkpoint [45,46] showed GCR formation rate comparable to the one caused by the rfc5-1 single mutation (Table 5). The replication defects of rfc5-1 could be suppressed by multicopy PCNA expression [47]. We hypothesized that the epistatic interaction between rfc5-1 and smc6-9 could be due to their link to PCNA ubiquitination. To test this hypothesis, we measured the GCR rate of the rad5 smc6-9 strain. Consistent with our hypothesis, the GCR rate of rad5 smc6-9 was comparable to strains having each mutation (Table 5). Lastly, an additional mutation of elg1, which activates DNA damage checkpoint and enhances GCR [7,48], in the smc6-9 strain, synergistically increased the GCR rate (Table 5).

Table 5.

Mutations of genes functioning in DNA damage checkpoints synergistically increased GCR rates with the smc6-9 mutation

| Relevant genotype | Wild type | smc6-9 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Mutation rate

(Canr 5-FOAr) |

Strain | Mutation rate

(Canr 5-FOAr) |

|

| Wild type | RDKY3615 | 3.5×10-10 (1) | YKJM3088 | 2.7×10-8 (76) |

| rad24Δ | RDKY3723 | 4.0×10-9 (11) | YKJM3626 | 6.7×10-8 (191) |

| rad17Δ | RDKY3721 | 3.0×10-9 (9) | YKJM3825 | 9.6×10-8 (274) |

| ddc1Δ | YKJM3760 | 2.0×10-9 (6) | YKJM3575 | 1.3×10-7 (378) |

| rfc5-1* | RDKY3727 | 6.6×10-8 (189) 25°C | YKJM3819 | 5.6×10-8 (160) 25°C |

| rad5Δ | RDKY1385 | 2.4×10-8 (68) | YKJM3139 | 3.4×10-8 (97) |

| elg1Δ | YKJM1405 | 1.7×10-8 (49) | YKJM3115 | 1.3×10-7 (383) |

| mec1Δ sml1Δ | RDKY3735 | 4.6×10-8 (131) | YKJM3146 | 1.2×10-7 (339) |

| rad9Δ | RDKY3719 | 2.0×10-9 (6) | YKJM3796 | 7.5×10-8 (215) |

| rad53Δ sml1Δ | RDKY3749 | 9.5×10-9 (27) | YKJM3816 | 2.4×10-7 (690) |

| chk1Δ | RDKY3745 | 1.3×10-8 (37) | YKJM3134 | 2.8×10-8 (80) |

| dun1Δ | RDKY3739 | 3.4×10-8 (97) | YKJM3136 | 8.4×10-8 (239) |

| pds1Δ* | RDKY3729 | 6.7×10-8 (190) 25°C | YKJM3117 | 1.2×10-7 (345) 25°C |

| tel1Δ | RDKY3731 | 2.0×10-10 (0.6) | YKJM3611 | 2.5×10-7 (798) |

| mre11Δ | RDKY3633 | 2.2×10-7 (629) | YKJM3203 | 5.5×10-7 (1559) |

| sgs1Δ | RDKY3814 | 7.7×10-9 (22) | YKJM3612 | 2.1×10-7 (609) |

| top3Δ | RDKY3815 | 9.5×10-9 (27) | YKJM3833 | 7.9×10-7 (2269) |

All strains are isogenic with the wild type strain, RDKY3615 [ura3-52, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63, his3Δ200, lys2ΔBgl, hom3-10, ade2Δ1, ade8, YEL069∷URA3] with the exception of the indicated mutations. The numbers in parenthesis indicate the fold induction of GCR rate relative to wild type GCR rate.

GCR rates of strains carrying either rfc5-1 or pds1 were determined at 25°C, but the rates determined at 30°C did not show significant difference. Canr 5-FOAr indicates resistant to canavanine and 5-FOA.

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Mec1 and Tel1, the yeast orthologues of ATR and ATM in higher eukaryotes, respectively, phosphorylate target proteins, including the Chk1 and Rad53 kinases, on Ser/Thr-Gln (S/T-Q) motifs and regulate several aspects of the cellular response to DNA damage and stalled replication forks [49,50]. Several studies in yeast have shown that the ends of DSBs are subjected to nucleolytic degradation to generate 3′-ended single-stranded DNA that recruits Mec1 and activates DNA damage checkpoint. The mutation of MEC1 or its downstream kinase, RAD53 in the smc6-9 strain synergistically increased the GCR formation rates (Table 5). We need to point out that both strains having mec1 or rad53 mutations had the suppressor of lethality mutation, sml1. We obtained similar synergistic increases of GCR rates when downstream targets of Mec1 such as Rad9 and Dun1 were mutated (Table 5). In contrast, the mutation in CHK1, which encodes another downstream kinase of Mec1 [51], did not show any synergistic interaction with the smc6-9 mutation (Table 5). Therefore, GCR formation in the smc6-9 strain is mainly suppressed by the Rad24-Mec1-Rad53/Rad9-Dun1 checkpoint. The inactivation of Pds1 that is a direct downstream target of Chk1, in the smc6-9 strain synergistically increased the GCR rate (Table 5). Because Rad53 also regulates Pds1 stability, the synergistic interaction of the pds1 mutation with smc6-9 could possibly be due to a role of Pds1 independent from the Chk1 regulation [52].

Another DNA damage checkpoint suppressing GCR formation is the Tel1-dependent checkpoint [53]. Like Mec1, the mutation of TEL1 in the smc6-9 strain also induced GCR rate considerably (Table 5). The Mre11 complex is required for the enrichment of the Mec1 kinase to DSB sites and the recruitment of Tel1 kinase and Mec1 interacting protein, Ddc2 to DSB sites [54-56]. Consistently, the mre11 mutation in the smc6-9 strain caused a synergistic increase in GCR rates similarly to the mec1 or tel1 mutation (Table 5). The synergistic effect between the Mec1- and Tel1-dependent branch of the DNA damage checkpoint and the smc6-9 mutation suggests that aberrant HR would initiate more GCRs in the smc6-9 strain if the DNA damage checkpoints were nonfunctional.

The inactivation of Mms21, a protein in the Smc5-Smc6 complex results in the accumulation of X molecules [33] that resemble pseudo-double Holliday junctions (dHJs) or hemicatenane-like molecules, and they occur specifically when forks encounter a damaged template [57]. Cells lacking the helicase Sgs1 or Topoisomerase III also accumulate these pseudo-dHJs. Sgs1 and Top3 mutants suffer from GCR [15]. Deletion of either SGS1 or TOP3 in the smc6-9 mutant synergistically increased the GCR rate (Table 5), raising the possibility that such hemicatenane-like molecules might generate breaks or be substrates for the generation of GCR.

The inactivation of the Mec1 kinase preferentially increases de novo telomere addition class GCRs [10,58]. In contrast, the smc6-9 mutation generated preferentially BIR-dependent translocation class GCRs (Table 3). To investigate whether the smc6-9 mutation specifically enhances translocation class GCRs even in strains defective in cell cycle checkpoints, we analyzed the breakpoint junction structures of GCRs from the smc6-9 mec1 strain. In contrast to 100% de novo telomere addition class GCR observed in the mec1 strain, the smc6-9 mec1 strain produced de novo telomere addition and translocations with micro-homology at breakpoints, 44% and 56%, respectively (Table 3). When the GCR rate of smc6-9 mec1 is divided by different GCR structures, the de novo telomere addition rate of smc6-9 mec1 (5.3 × 10-8) was not significantly different from that of mec1 (4.6 × 10-8). Therefore, the major enhancement of GCR in smc6-9 mec1 was due to the increase in the rate of translocation with micro-homology at breakpoints as observed in 6.7 × 10-8 of the smc6-9 mec1 strain compared to no translocation in the mec1 strain. Similarly, the tel1 mutation synergistically increased translocation class GCRs in the smc6-9 strain (Table 3). It should be pointed out that less homology at the breakpoint junctions seems to be required in the smc6-9 tel1 strain because there was a large increase of non-homology mediated translocations in the smc6-9 tel1 strain compared to the smc6-9 strain. These results are consistent with observations that the Smc5-Smc6 complex specifically suppresses BIR-mediated translocations.

3.4. Defects in telomere maintenance enhance GCR formation synergistically in the smc6-9 strain

The Smc5-Smc6 complex binds to telomeric regions [35] and it is important to regulate the maintenance of telomeres [37,59]. We have shown that despite de novo telomere addition being the preferred choice of GCR in yeast chromosome V GCR assay [10,17], most GCRs in the smc6-9 mutant occur through BIR-mediated translocations (Table 3). One possibility is that the Smc5-Smc6 complex plays a direct role in the de novo telomere GCR pathway. The PIF1 gene encodes a transcript that translates into two helicases by alternative initiations [60]. In contrast to the unique function to mitochondria by one translated Pif1, the nuclear Pif1 is a telomerase inhibitor that blocks the recruitment of telomerase to the telomere [61]. The pif1-m2 mutation specifically inactivates nuclear Pif1 and increases de novo telomere addition class GCRs [17].

The GCR rate of the smc6-9 pif1-m2 strain showed a synergistic enhancement compared to strains having each mutation (Table 6). A mutation in a non-Smc subunit of the Smc5-Smc6 complex, nse3-2 showed a similar effect (Table 6, footnote). Next we characterized the nature of the GCR events in these strains. We found that while chromosomal translocations were still present in the smc6-9 pif1-m2 strain, a high increase in de novo telomere addition class GCRs was also observed (Table 3). Conversely, when the de novo telomere addition pathway was inactivated in the smc6-9 strain by deletion of TLC1 or EST2, which encode the RNA subunit and catalytic subunit of telomerase, respectively [62], the translocation class GCRs were synergistically increased (Table 3 and 6). These translocations showed both non-homology and micro-homology at the breakpoint junctions. We also detected chromosome fusion events likely mediated by NHEJ. Interestingly we found one case of de novo telomere addition GCR in the smc6-9 tlc1 mutant. It is not statistically significant (p=0.27) and was most likely generated by a BIR event where the broken chromosome invaded very close to the telomere sequence of another chromosome. Even though there was strong genetic interaction between the smc6-9 mutation and mutations in telomere maintenance gene, the smc6-9 mutation did not affect telomere length (Supplement Fig. 1).

Table 6.

The smc6-9 mutation synergistically increased GCRs with mutations affecting telomere maintenance

| Relevant genotype | Wild type | smc6-9 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Mutation rate

(Canr 5-FOAr) |

Strain | Mutation rate

(Canr 5-FOAr) |

|

| Wild type | RDKY3615 | 3.5×10-10 (1) | YKJM3088 | 2.7×10-8 (76) |

| pif1-m2 | RDKY4343 | 4.8×10-8 (137) | YKJM3091 | 6.3×10-7 (1808) |

| tlc1Δ | RDKY4224 | 3.1×10-10 (0.9) | YKJM3143 | 3.2×10-7 (914) |

| est1Δ | RDKY4345 | 1.5×10-10 (0.4) | YKJM3787 | 6.2×10-8 (177) |

| est2Δ | RDKY4347 | 1.2×10-10 (0.3) | YKJM3137 | 1.2×10-7 (339) |

| est3Δ | RDKY4349 | 1.5×10-10 (0.4) | YKJM3788 | 1.1×10-7 (300) |

All strains are isogenic with the wild type strain, RDKY3615 [ura3-52, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63, his3Δ200, lys2ΔBgl, hom3-10, ade2Δ1, ade8, YEL069∷URA3] with the exception of the indicated mutations. The nse3-2 and nes3-2 pif1-m2 mutations increased GCR rates 1.9 × 10-8 (54) and 3.0×10-7 (868), respectively). The numbers in parenthesis indicate the fold induction of GCR rate relative to wild type GCR rate. Canr 5-FOAr indicates resistant to canavanine and 5-FOA.

Our results on the genetic interactions of smc6-9 and mutations in different telomere maintenance genes demonstrate that the pathways for de novo telomere addition are functional in smc6-9 cells, and confirm that the BIR-dependent translocations (Fig. 1) are likely due to a defect of a specific role of the Smc5-Smc6 complex. Therefore, the Smc5-Smc6 complex defines a new pathway for the suppression of GCRs mediated by BIR.

4. Discussion

Defects in Smc5-Smc6 cause delayed DNA replication of repetitive sequences, such as rDNA and lead to mitosis before the completion of replication in these regions [41]. It would cause an increase in DNA DSBs during mitosis [35], which could provide potential substrates for GCR. Indeed, we have found that the smc6-9 strain preferentially enhanced translocations type GCR (Table 2 and 3). Translocations observed in the smc6-9 strain have unique features. All translocations seem to be produced by Rad51-Rad52 dependent BIR (Table 4 and Fig. 1) and are independent of NHEJ (Table 4). In addition, translocations seem to be generated close to repetitive sequences including δ sequences, autonomously replication sequences (ARS), tRNA genes and other sequences that are repeated many times in genome (Fig. 1B). The δ sequences are Ty recombination hot spot and were found as a putative hot spot for DSB induced non-reciprocal translocations [63,64]. ARS are used as a DNA replication origin and the deletion of ARS sequence in meiotic recombination showed the reduction of both gene conversions and reciprocal crossovers in the hotspot region [65]. In additioin, these sequences could cause pausing of DNA replication. Therefore, higher instability of these repetitive sequences in the smc6-9 strain could result in translocations.

Because the Smc5-Smc6 complex has many roles during DNA replication and chromosome segregation [35,41], it is difficult to ascertain which defects by the smc6-9 mutation cause DNA damage to translocations. For example, the cohesion defect impairs sister chromatid recombination [31,66], increasing intra-chromatid recombination in the tandem array of ribosomal repeats [36]. Recent work even suggested that Smc5-Smc6 would be required for the efficient loading of cohesin to DSB sites [67,68]. Smc5-Smc6 could restrain the initiation of strand invasions between different chromosomes that lead to BIR-mediated translocation events. Furthermore, the fact that Smc5-Smc6 interacting proteins possess enzymatic activity, such as the E3 SUMO ligase Mms21 [59] raises the possibility that DSBs are generated by defects in the regulation of Mms21 during DNA repair and replication. To support this, the mms21-11 mutation increased the GCR rate similar to smc6-9 (Table 2). Further analysis of Smc5-Smc6 protein functions is necessary to reveal a solid mechanism for how DNA damage is generated to produce translocations.

Many mutations affecting GCR rates preferentially increased de novo telomere addition in the chromosome V GCR assay [1,5]. In contrast, the smc6-9 mutation preferentially enhanced translocation (Table 3). Furthermore, the translocations in the smc6-9 strain depend on the HR machinery proteins, Rad51 and Rad52 (Table 4) that also block telomerase access to DSBs [69]. The smc6-9 mutation affects certain types of HR during the G2/M phase. It is possible that the smc6-9 mutation allows Rad51 and/or Rad52 to associate or bind with higher affinity to DSBs at the G2/M phase thus blocking telomerase access. Prolonged Rad51 association with DSB would eventually initiate BIR with other chromosomes to produce a translocation event. Intriguingly, the Rad52 protein and its S. pombe homolog Rad22 protein are sumoylated [43,70]. Although it is still unclear whether the sumoylation of Rad52 affects HR efficiency, it could at least affect the kinetics of the removal of Rad51 from DSB. Consistent with this, the siz1 or siz2 mutation that would affect Rad52 sumoylation synergistically increased GCR rate in the smc6-9 strain (Table 4). The defect in the Smc5-Smc6 complex could result in a longer association of Rad51 with the DSB and allow initiation of BIR.

There are three different cell cycle checkpoints redundantly suppressing GCR formation. Even though a mutation of the DNA replication checkpoint by rfc5-1 was epistatic with the smc6-9 mutation in GCR rates (Table 5), the GCRs produced by these two mutations were different. In contrast to de novo telomere addition class GCRs by the rfc5-1 mutation [10], the smc6-9 mutation preferentially produced translocations (Table 3). Therefore, there is a complex genetic interaction between rfc5-1 and smc6-9 that is currently not clearly understood. Genetic interactions regarding GCR suppression between defects in DNA damage checkpoint and the smc6-9 mutation imply that both DNA damage checkpoints, Rad24-Mec1-Rad53/Rad9-Dun1 and Mre11-Tel1 pathways function to suppress GCRs from DNA damage caused in the smc6-9 strain.

The helicase Sgs1 and its binding partner Top3 are known to be crucial in the maintenance of genomic stability. In addition to the loss of cell cycle checkpoint function [71], the loss of Sgs1 or Top3 increases sister chromatid exchange rate and HR [72]. Similar to the mms21-11 mutation, the sgs1 mutation accumulates pseudo-dHJ like structures upon exposure to the DNA damaging agent methylmethane sulfonate [33,57]. We found synergistic increases of GCR rates by either the sgs1 or top3 mutation with the smc6-9 mutation (Table 5). Thus, one possibility is that an increased level of hemicatenane-like molecules causes the observed increment in GCR rates seen in the double mutants.

High enhancement of GCR formation in the smc6-9 strain by an additional mutation in telomerase subunits (TLC1 or EST2), TEL1, or yKU70 suggested that unprotected or unusual telomeres could be a good substrate for GCR formation. Although we did not see the telomere size change in the smc6-9 strain (Supplement Fig. 1), it is possible that mutations in the SMC5-SMC6 complex genes and one of the telomere maintenance genes could produce more DNA damage at telomeres to generate GCR formation. Intriguingly, human SMC5-SMC6 functions in telomere maintenance, especially in the alternative telomere length mechanism through the sumoylation of telomere component such as TRF1 and RAP1 [37].

One interesting observation in GCR structures identified among these strains was chromosome fusions observed only when telomerase subunits or yKu70 was inactivated (Table 3). Previously, we observed chromosome fusions when the TLC1 gene is mutated together with checkpoint genes (rfc5-1, mec1, or tel1) [17]. In this study, it was not clear whether further decrease of telomere size by the tlc1 mutation in the checkpoint defective strains facilitated chromosome fusions. However, the presence of chromosome fusion in the smc6-9 tlc1 and smc6-9 est2 strains suggests that decreased telomere size is not a major cause of chromosome fusion. Furthermore, because the smc6-9 mutation did not cause any cell cycle checkpoint defect, checkpoint inactivation is not an absolute requirement for chromosome fusion. Lastly, there were no chromosome fusions in the smc6-9 tel1 strain despite a marked enhancement of GCR formation (Table 3 and 5). Therefore, telomerase itself or recruitment of telomerase to DNA damage by yKu are extremely important for the protection of chromosome ends from fusion to other broken chromosomes.

The studies presented here have extended the identification of GCR suppression pathways by defining the role of the Smc5-Smc6 complex. In addition, the detailed analysis of GCRs produced by the defect in this pathway revealed Smc5-Smc6's putative roles to prevent DNA damage from repetitive sequences to initiate BIR-dependent translocation. Lastly, high incidences of translocations in the δ sequence, ARS, tRNA gene, and other repetitive sequences strongly argue that some genomic sequences are more prone to becoming substrates for GCR formation.

Supplementary Material

Supplement Fig. 1. The smc6-9 mutation does not affect telomere size. Telomere size was determined by Southern hybridization of yeast genomic DNA digested with XhoI with TG repeated probe as previously described [7].

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Lee (U. Texas San Antonio) for helpful discussion; X. Zhao (Sloan Kettering Cancer Center) for the mms21-11 strain; the NIH fellows editorial board for comments on the manuscript. J. Fekecs (NHGRI) for Figure preparation. K.M. especially thanks E. Cho. This research was supported by the intramural research program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health (to K.M.) and the Medical Research Council UK (to L.A.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kolodner RD, Putnam CD, Myung K. Maintenance of genome stability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2002;297:552–557. doi: 10.1126/science.1075277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loeb LA, Loeb KR, Anderson JP. Multiple mutations and cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:776–781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0334858100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khanna KK, Jackson SP. DNA double-strand breaks: signaling, repair and the cancer connection. Nat Genet. 2001;27:247–254. doi: 10.1038/85798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C, Kolodner RD. Gross chromosomal rearrangements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae replication and recombination defective mutants. Nat Genet. 1999;23:81–85. doi: 10.1038/12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motegi A, Myung K. Measuring the rate of gross chromosomal rearrangements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: A practical approach to study genomic rearrangements observed in cancer. Methods. 2007;41:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt KH, Pennaneach V, Putnam CD, Kolodner RD. Analysis of gross-chromosomal rearrangements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 2006;409:462–476. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)09027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banerjee S, Myung K. Increased genome instability and telomere length in the elg1-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant are regulated by S-phase checkpoints. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:1557–1566. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.6.1557-1566.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banerjee S, Smith S, Myung K. Suppression of gross chromosomal rearrangements by yKu70-yKu80 heterodimer through DNA damage checkpoints. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1816–1821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504063102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lengronne A, Schwob E. The yeast CDK inhibitor Sic1 prevents genomic instability by promoting replication origin licensing in late G(1) Mol Cell. 2002;9:1067–1078. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myung K, Datta A, Kolodner RD. Suppression of spontaneous chromosomal rearrangements by S phase checkpoint functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell. 2001;104:397–408. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myung K, Pennaneach V, Kats ES, Kolodner RD. Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromatin-assembly factors that act during DNA replication function in the maintenance of genome stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232239100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka S, Diffley JF. Deregulated G1-cyclin expression induces genomic instability by preventing efficient pre-RC formation. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2639–2649. doi: 10.1101/gad.1011002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Motegi A, Kuntz K, Majeed A, Smith S, Myung K. Regulation of gross chromosomal rearrangements by ubiquitin and SUMO ligases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:1424–1433. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.4.1424-1433.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith S, Hwang JY, Banerjee S, Majeed A, Gupta A, Myung K. Mutator genes for suppression of gross chromosomal rearrangements identified by a genome-wide screening in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9039–9044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403093101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myung K, Datta A, Chen C, Kolodner RD. SGS1, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologue of BLM and WRN, suppresses genome instability and homeologous recombination. Nat Genet. 2001;27:113–116. doi: 10.1038/83673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt KH, Wu J, Kolodner RD. Control of translocations between highly diverged genes by Sgs1, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homolog of the Bloom's syndrome protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:5406–5420. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00161-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myung K, Chen C, Kolodner RD. Multiple pathways cooperate in the suppression of genome instability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2001;411:1073–1076. doi: 10.1038/35082608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pennaneach V, Kolodner RD. Recombination and the Tel1 and Mec1 checkpoints differentially effect genome rearrangements driven by telomere dysfunction in yeast. Nat Genet. 2004;36:612–617. doi: 10.1038/ng1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kats ES, Albuquerque CP, Zhou H, Kolodner RD. Checkpoint functions are required for normal S-phase progression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae RCAF- and CAF-I-defective mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3710–3715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511102103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan SW, Blackburn EH. Telomerase and ATM/Tel1p protect telomeres from nonhomologous end joining. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1379–1387. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00174-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang ME, Rio AG, Nicolas A, Kolodner RD. A genomewide screen in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for genes that suppress the accumulation of mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11529–11534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2035018100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ragu S, Faye G, Iraqui I, Masurel-Heneman A, Kolodner RD, Huang ME. Oxygen metabolism and reactive oxygen species cause chromosomal rearrangements and cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9747–9752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703192104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Putnam CD, Pennaneach V, Kolodner RD. Chromosome healing through terminal deletions generated by de novo telomere additions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13262–13267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405443101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myung K, Smith S, Kolodner RD. Mitotic checkpoint function in the formation of gross chromosomal rearrangements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15980–15985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407010101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang JY, Smith S, Myung K. The Rad1-Rad10 complex promtes the production of gross chromosomal rearrangements from spontaneous DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2005;169:1927–1937. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.039768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cortes-Ledesma F, de Piccoli G, Haber JE, Aragon L, Aguilera A. SMC proteins, new players in the maintenance of genomic stability. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:914–918. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.8.4107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lehmann AR. The role of SMC proteins in the responses to DNA damage. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4:309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Losada A, Hirano T. Dynamic molecular linkers of the genome: the first decade of SMC proteins. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1269–1287. doi: 10.1101/gad.1320505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nasmyth K, Haering CH. The structure and function of SMC and kleisin complexes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:595–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lehmann AR, Walicka M, Griffiths DJ, Murray JM, Watts FZ, McCready S, Carr AM. The rad18 gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe defines a new subgroup of the SMC superfamily involved in DNA repair, Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:7067–7080. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.7067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Piccoli G, Cortes-Ledesma F, Ira G, Torres-Rosell J, Uhle S, Farmer S, Hwang JY, Machin F, Ceschia A, McAleenan A, Cordon-Preciado V, Clemente-Blanco A, Vilella-Mitjana F, Ullal P, Jarmuz A, Leitao B, Bressan D, Dotiwala F, Papusha A, Zhao X, Myung K, Haber JE, Aguilera A, Aragon L. Smc5-Smc6 mediate DNA double-strand-break repair by promoting sister-chromatid recombination. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1032–1034. doi: 10.1038/ncb1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindroos HB, Strom L, Itoh T, Katou Y, Shirahige K, Sjogren C. Chromosomal association of the Smc5/6 complex reveals that it functions in differently regulated pathways. Mol Cell. 2006;22:755–767. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Branzei D, Sollier J, Liberi G, Zhao X, Maeda D, Seki M, Enomoto T, Ohta K, Foiani M. Ubc9- and mms21-mediated sumoylation counteracts recombinogenic events at damaged replication forks. Cell. 2006;127:509–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santa Maria SR, Gangavarapu V, Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S. Requirement of Nse1, a subunit of the Smc5-Smc6 complex, for Rad52-dependent postreplication repair of UV-damaged DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:8409–8418. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01543-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torres-Rosell J, Machin F, Farmer S, Jarmuz A, Eydmann T, Dalgaard JZ, Aragon L. SMC5 and SMC6 genes are required for the segregation of repetitive chromosome regions. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:412–419. doi: 10.1038/ncb1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torres-Rosell J, Sunjevaric I, De Piccoli G, Sacher M, Eckert-Boulet N, Reid R, Jentsch S, Rothstein R, Aragon L, Lisby M. The Smc5-Smc6 complex and SUMO modification of Rad52 regulates recombinational repair at the ribosomal gene locus. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:923–931. doi: 10.1038/ncb1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Potts PR, Yu H. The SMC5/6 complex maintains telomere length in ALT cancer cells through SUMOylation of telomere-binding proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:581–590. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lea DE, Coulson CA. The distribution of the numbers of mutants in bacterial populations. J Genet. 1948;49:264–285. doi: 10.1007/BF02986080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lengronne A, Pasero P, Bensimon A, Schwob E. Monitoring S phase progression globally and locally using BrdU incorporation in TK(+) yeast strains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1433–1442. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.7.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lydeard JR, Jain S, Yamaguchi M, Haber JE. Break-induced replication and telomerase-independent telomere maintenance require Pol32. Nature. 2007;448:820–823. doi: 10.1038/nature06047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torres-Rosell J, De Piccoli G, Cordon-Preciado V, Farmer S, Jarmuz A, Machin F, Pasero P, Lisby M, Haber JE, Aragon L. Anaphase onset before complete DNA replication with intact checkpoint responses. Science. 2007;315:1411–1415. doi: 10.1126/science.1134025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McEachern MJ, Haber JE. Break-induced replication and recombinational telomere elongation in yeast. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:111–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sacher M, Pfander B, Hoege C, Jentsch S. Control of Rad52 recombination activity by double-strand break-induced SUMO modification. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1284–1290. doi: 10.1038/ncb1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weinert T. DNA damage checkpoints update: getting molecular. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:185–193. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naiki T, Shimomura T, Kondo T, Matsumoto K, Sugimoto K. Rfc5, in cooperation with rad24, controls DNA damage checkpoints throughout the cell cycle in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5888–5896. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.16.5888-5896.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shimomura T, Ando S, Matsumoto K, Sugimoto K. Functional and physical interaction between Rad24 and Rfc5 in the yeast checkpoint pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5485–5491. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Branzei D, Seki M, Enomoto T. Rad18/Rad5/Mms2-mediated polyubiquitination of PCNA is implicated in replication completion during replication stress. Genes Cells. 2004;9:1031–1042. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2004.00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kanellis P, Agyei R, Durocher D. Elg1 forms an alternative PCNA-interacting RFC complex required to maintain genome stability. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1583–1595. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00578-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allen JB, Zhou Z, Siede W, Friedberg EC, Elledge SJ. The SAD1/RAD53 protein kinase controls multiple checkpoints and DNA damage-induced transcription in yeast. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2401–2415. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.20.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanchez Y, Desany BA, Jones WJ, Liu Q, Wang B, Elledge SJ. Regulation of RAD53 by the ATM-like kinases MEC1 and TEL1 in yeast cell cycle checkpoint pathways. Science. 1996;271:357–360. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanchez Y, Bachant J, Wang H, Hu F, Liu D, Tetzlaff M, Elledge SJ. Control of the DNA damage checkpoint by chk1 and rad53 protein kinases through distinct mechanisms. Science. 1999;286:1166–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agarwal R, Tang Z, Yu H, Cohen-Fix O. Two distinct pathways for inhibiting pds1 ubiquitination in response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45027–45033. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306783200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.D'Amours D, Jackson SP. The Mre11 complex: at the crossroads of dna repair and checkpoint signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:317–327. doi: 10.1038/nrm805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lisby M, Barlow JH, Burgess RC, Rothstein R. Choreography of the DNA damage response: spatiotemporal relationships among checkpoint and repair proteins. Cell. 2004;118:699–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakada D, Hirano Y, Sugimoto K. Requirement of the Mre11 complex and exonuclease 1 for activation of the Mec1 signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:10016–10025. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.10016-10025.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakada D, Matsumoto K, Sugimoto K. ATM-related Tel1 associates with double-strand breaks through an Xrs2-dependent mechanism. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1957–1962. doi: 10.1101/gad.1099003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liberi G, Maffioletti G, Lucca C, Chiolo I, Baryshnikova A, Cotta-Ramusino C, Lopes M, Pellicioli A, Haber JE, Foiani M. Rad51-dependent DNA structures accumulate at damaged replication forks in sgs1 mutants defective in the yeast ortholog of BLM RecQ helicase. Genes Dev. 2005;19:339–350. doi: 10.1101/gad.322605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Myung K, Kolodner RD. Suppression of genome instability by redundant S-phase checkpoint pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4500–4507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062702199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao X, Blobel G. A SUMO ligase is part of a nuclear multiprotein complex that affects DNA repair and chromosomal organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4777–4782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500537102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schulz V, Zakian VA. The Saccharomyces PIF1 DNA helicase inhibits telomere elongation and de novo telomere formation. Cell. 1994;76:145–155. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou J, Monson EK, Teng S, Schulz VP, Zakian VA. Pif1p helicase, a catalytic inhibitor of telomerase in yeast. Science. 2000;289:771–774. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lingner J, Cech TR. Telomerase and chromosome end maintenance. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:226–232. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lemoine FJ, Degtyareva NP, Lobachev K, Petes TD. Chromosomal translocations in yeast induced by low levels of DNA polymerase a model for chromosome fragile sites. Cell. 2005;120:587–598. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith CE, Llorente B, Symington LS. Template switching during break-induced replication. Nature. 2007;447:102–105. doi: 10.1038/nature05723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rattray AJ, Symington LS. Stimulation of meiotic recombination in yeast by an ARS element. Genetics. 1993;134:175–188. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cortes-Ledesma F, Aguilera A. Double-strand breaks arising by replication through a nick are repaired by cohesin-dependent sister-chromatid exchange. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:919–926. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Potts PR, Porteus MH, Yu H. Human SMC5/6 complex promotes sister chromatid homologous recombination by recruiting the SMC1/3 cohesin complex to double-strand breaks. Embo J. 2006;25:3377–3388. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Strom L, Karlsson C, Lindroos HB, Wedahl S, Katou Y, Shirahige K, Sjogren C. Postreplicative formation of cohesion is required for repair and induced by a single DNA break. Science. 2007;317:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.1140649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vega LR, Mateyak MK, Zakian VA. Getting to the end: telomerase access in yeast and humans. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:948–959. doi: 10.1038/nrm1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ho JC, Warr NJ, Shimizu H, Watts FZ. SUMO modification of Rad22, the Schizosaccharomyces pombe homologue of the recombination protein Rad52. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4179–4186. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.20.4179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cobb JA, Bjergbaek L, Gasser SM. RecQ helicases: at the heart of genetic stability. FEBS Lett. 2002;529:43–48. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03269-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rothstein R, Gangloff S. Hyper-recombination and Bloom's syndrome: microbes again provide clues about cancer. Genome Res. 1995;5:421–426. doi: 10.1101/gr.5.5.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement Fig. 1. The smc6-9 mutation does not affect telomere size. Telomere size was determined by Southern hybridization of yeast genomic DNA digested with XhoI with TG repeated probe as previously described [7].