Abstract

Epigenetics studies factors related to the organism and environment that modulate inheritance from generation to generation. Molecular epigenetics examines non-coding DNA (ncdDNA) vs. coding DNA (cdDNA), and pertains to every domain of physiology, including immune and brain function. Molecular cartography, including genomics, proteomics, and interactomics, seeks to recognize and to identify the multi-faceted and intricate array of interacting genes and gene products that characterize the function and specialization of each individual cell in the context of cell-cell interaction, tissue, and organ function. Molecular cartography, epigenetics, and chromatin assembly, repair and remodeling (CARR), which, together with the RNA interfering signaling complex (RISC), is responsible for much of the control and regulation of gene expression, intersect.

We describe current and ongoing studies aimed to apply these overlapping areas of research, CARR and RISC, to a novel understanding of the immuno-neuropathology of HIV-1 infection, as an example. Taken together, the arguments presented here lead to a novel working hypothesis of molecular immune epigenetics as it pertains to HIV/AIDS, and the immunopathology of HIV-1-infected CD4+ cells. Specifically, we discuss these views in the context of the structure-function relationship of chromatin, the cdDNA/ncdDNA ratio, and possible nucleotide divergence in the untranslated regions (UTRs) of mature mRNA intronic and intergenic DNA sequences, and putative catastrophic consequences for immune surveillance and the preservation of health in HIV/AIDS. Here, we discuss the immunopathology of HIV Infection, with emphasis on CARR in cellular, humoral and molecular immune epigenetics.

Keywords: epigenetics, hologenomics, coding and noncoding DNA, human T cells, Tregs, HIV-1, AIDS, neuroAIDS, immunopathology, translational evidence-based decision-making

Background

Close to 98-99% of the eukaryotic genome consists of DNA that is not translated (i.e., non-coding). A proportion of non-coding DNA may have regulatory functions, and seem to control developmental and physiological pathways, and responses to pathological processes [1]. But the function of the remaining non-coding portions is unclear. Peptides, hormones, and other biological molecules (e.g., drugs of abuse) probably bind to specific elements of chromatin, hence altering its structure and its function. This may modify the coding DNA/non-coding DNA ratio and regions, and our current working hypothesis states that these epigenetic changes, as minuscule as they may be, have significant outcomes for the cell and the organism.

Case in point, we propose, infection of immune cells that express the cluster of differentiation (CD) 4 by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1, and integration of viral genomic structures into the DNA of its host most likely alters the structure-function relationship of chromatin. One putative outcome is a significant degree of nucleotide divergence in the untranslated regions (UTRs) of mature mRNA intronic as well as intergenic DNA sequences. The rationale and salient supporting literature are discussed in Part I and II of this hypothesis. HIV-1 infects CD4+ cells, and chemokine receptors serve as co-receptors for infection by binding to certain HIV-1 envelope proteins (e.g., CXCR4 favors X4 HIV-1 strain T cell tropism, CCR5 favors R5 strain tropism). A subpopulation of CD4+ T lymphocytes involved in regulatory processes of cellular immune responses, regulatory T cells (Tregs), express CCR5, are CXCR4/CXCL12+, and are highly susceptible to HIV-1 infection. Tregs harbors viral replication [2-4].

Depletion of Tregs enhances the proliferation of the remaining CD4+ population Sub-sets of Tregs vary in their expression of the homing receptor, CD62L, and their ability to migrate to peripheral lymph nodes [5]. These subsets are activated CD4+CD25+ cells that also express FoxP3, a transcriptional repressor that targets composite NF-AT/AP-1 sites in cytokine gene promoters. The expression of FoxP3 is stabilized by epigenetic modifications to allow the establishment of Tregs into a long-term cell lineage [6]. FoxP3-transduced T-cells are markedly more susceptible to HIV-1 infection, and HIV-positive individuals with a low percentage of CD4+ and higher levels of activated T-cells have greatly reduced levels of FoxP3+CD4+CD25+ T-cells [3,7].

Methodology

As methodological research approaches are devised to test the role of epigenetic modulation in the immunopathology of HIV/AIDS, it must be considered that Neuropilin-1 (Nrp1) is a plasma trans-membrane receptor (120 kDa) involved in axon guidance, angiogenesis, and the activation of T cells. CD4+CD25+ Tregs are constitutively Nrp1+. Nrp1 binds to the class 3 semaphorin subfamily and the heparin-binding forms of vascular endothelial growth factor and placenta growth factor. By mediating contact between dendritic and T cells via homotypic interactions, Nrp-1 is critical to the initiation of the primary immune response, but it is down-regulated in naïve CD4+CD25- T cells following TcR stimulation. Molecular cartography demonstrates that Nrp-1 signaling is mediated through its C-terminal domain and downstream molecules, including phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Specific and effective silencing of the regulators of G-protein signaling(RGS)- Gα-interacting protein (GAIP)-interacting protein C terminus (GIPC) domain in vascular endothelium results in inhibition of Nrp1-mediated migration [3,8].

Epigenetic studies show that, in the case of human papilloma virus (HPV), HPV-18 E6 renders cells less sensitive to the cytostatic effect of tumor necrosis factor (TGF)-β by lowering the intracellular amount of TIP-2/GIPC [9]. Whether or not similar observations might apply to HIV-1 infection remains to be elucidated.

Discussion

Taken together, these lines of evidence indicate that Tregs are premier candidates for epigenetic studies of non-coding DNA in HIV/AIDS, and NeuroAIDS. We hypothesize that, by inserting itself in the host genome, HIV alters the chromatin in such a manner as to unveil otherwise non-coding DNA, thus favoring, for instance, the expression of CD62L. The suppressive function of the CD62L+ subset of Tregs is by far more potent on a per cell basis, than its CD62L- Tregs cohort, and it avidly proliferates, expands readily, and is very responsive to chemokine-driven migration [10]. CD62L+ Tregs are most likely to migrate across the blood-brain barrier [11] and to contribute profoundly to the in situ immunopathology of NeuroAIDS.

That Treg are susceptible to HIV-1 infection is also pertinent to clinical decision-making for treatment intervention, and opens the way to an emerging field that may be termed translational evidence-based epigenetic medicine. Patients with HIV/AIDS with a low percentage of CD4+, typically have greatly reduced numbers of FoxP3+CD4+CD25+ T cells. CD25+ T cells expand significantly in peripheral blood of HIV-seropositive patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), and exhibit phenotypic (e.g., CD25, CXCR4), molecular (e.g., FoxP3), and functional characteristics (e.g., impaired proliferative and IL-2 production responses) of Tregs [7]. This response appears specific since recent local immunity studies have established that the frequency and the absolute number of mucosal, but not of peripheral blood FoxP3+ Tregs significantly increase in untreated HIV-seropositive patients, but normalize following HAART treatment [12].

Cytokines, through signal transduction pathways, elicit homeostatic mechanisms that regulate the survival and proliferation of immune cells. Dendritic cells and other antigen presenting cells produce regulatory amounts of interleukin (IL)-10, IL-12, IL-15 and IL-4, which lead T cells either to a TH1 or a TH2 pattern of cytokines [3,13]. The regulatory contribution of non-coding DNA to this process is emerging [13]. Recent data have established, during both TH1 and TH2 differentiation of human neonatal CD4+ T cells, characteristic alterations in chromatin architecture at specific loci. Specifically, cis-regulatory elements that pointed to the acquisition of permissive chromatin structure at the proximal promoter were seen in TH2 cells, rather than the formation of locus-wide repressive chromatin in TH1 cells [14].

Infection of CD4+ immune cells by HIV-1 alters TH1/TH2 modulation, and the TH1/TH2 ratio [3], which, under normal conditions, is kept under control in part by Tregs, and counter-modulated by cytokines, including interferon (IFN)-γ, IL-10 and IL-4 [3]. That Tregs are putatively involved in suppressing TH1 cytokine responses to ensure polarization of the TH2 pattern of cytokines during an immune response is questionable, in light of recent data. The Tregs population is complex in nature and function, as indicated above. It is composed of several overlapping sub-populations with specialized regulatory functions. The defining principle of Tregs is the lack of effector functions due to a partial or incomplete differentiation to either TH1 or TH2. The role of non-coding regions in actualizing this fine functional modulation of Tregs must now be explored.

Additional patterns of cytokines are involved in the regulatory arm of the cellular immunopathology of HIV/AIDS, including the IL-10 family (i.e., IL-20 and related cytokines) [15], and the inflammatory arm of the response. It is now clear that certain growth factors (e.g., granulocyte/macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) modulate the increase the production of bone marrow-derived antigen-presenting dendritic cells, and the production of IL-23 by these cells. IL-23, a member of the IL-12 cytokine family, shares p40, and binds to the IL12b1/IL-23R receptor complex. It plays a critical role in end-stage inflammation via signaling of the Janus tyrosine kinases (Jak) and signal transducers and activators of transcription (Stat) (JAK/STAT) pathway. This pattern of cytokine is an “inflammatory helper T cell differentiation” (i.e., inflammatory Thelper cells, THi) [3,16].

Administration of IL-11 down-regulates IL-12. IL-23 augments production of IL-17 by T cells, which becomes the significant cytokine in the involvement of T cells in mediating and regulating the inflammatory process. IL-17 down-regulates neutrophils, and in vitro it synergizes the effects of TNFa for GM-CSF induction, for increased intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 (CD54) expression by CD34+ progenitors, for increased neutrophil maturation, and for increased pro-inflammatory IL-6 and prostaglandin (PG)E2 and G-CSF growth factor production by keratinocytes and endothelial cells. IL-17 thus favors increased secretion of the migration-inducing cytokine, IL-8. Whether or not these processes are mediated through GIPC is speculative at present, and remains to be tested. In human U937 cells, and probably in all lymphoid and myeloid cells, the JAK/STAT signaling pathway is responsible for transducing signals from the IL-17 receptor. Human vascular embryonic cells (HUVEC) express a homologue of IL-17R, as do ductal epithelial cells of human salivary glands, suggesting a significant role for IL-17 in mucosal immunity. In fact, in inflamed gingival tissue, IL-17 is the predominant cytokine in tissue proximal to 4-5 mm diseased periodontal pockets. IL-17 plays a critical role in immunity and mucosal inflammation, by modulating the effects of GM-CSF and other growth factors [3,16].

Non-coding DNA plays an important role in regulating cytokine patterns. It is clear that genomic manipulation of T cells in vitro, such as the introduction of FoxP3 into conventional mouse T cells, has the critical outcome of converting these cells to the Tregs phenotype. Patients with mutations at the FoxP3 site show significant impairments in Tregs function [17].

It is also established that CD4+ cells can manifest extensive changes in chromatin structure and architecture. The chromatin in the TH1 and TH2 lineages undergo locus-specific remodeling during cytokine pattern polarization [14,18,19]. THi produce IL-17 and IL-17F, two highly homologous cytokines that have genes located in the same chromosomal region, undergo a series of chromatin remodeling events during their lineage polarization similar to that which characterize TH1 and TH2 cells, such that epigenetic modifications such as histone H3 acetylation and Lys-4 tri-methylation are specifically associated with IL-17 and IL-17F gene promoters in the THi lineage. Early during the T cell activation state, histone acetylation on these promoters is synergized by TGFβ and IL-6, suggesting a role for these cytokines is permitting chromatin accessibility for transcription factors. Multiple noncoding sequences exist within the IL-17-IL-17F locus that appear to be conserved across species, and that also are associated with hyper-acetylated histone 3 in a lineage-specific manner, confirming the stringency of these regulatory regions [20].

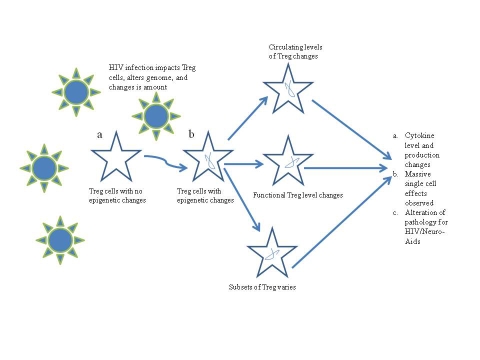

In brief, it is conceivable that, mechanistically, these and other epigenetic transformations of the chromatin structure, putatively following the insertion of infecting HIV-1, lead to an important imbalance in the proportion of circulating and functional Tregs, and to cytokine imbalance (Figure 1). This hypothesis is timely in view of the observations that in latently infected resting CD4+ lymphocytes, HIV-1 transcription appears repressed by de-acetylation events mediated by histone de-acetylases. Reactivation of HIV-1 from latency engages a displacement of these histone de-acetylases by means of histone acetyl-transferases in an NF-κB-mediated mechanism, and leads to viral transcriptional activator Tat and multiple acetylation events. Following this chromatin remodeling in the domain of the viral promoter region, transcription is initiated and leads to the formation of the trans-acting response element (TAR) element. The complex of Tat with the human positive transcription elongation factor (p-TEF)b then binds the loop structures of TAR RNA. p-TEFb is composed of Cdk9 and cyclin T1, and acts a general transcription elongation factor that phosphorylates the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Thus, CDK9 is positioned by this chromatin remodeling to phosphorylate the cellular RNA polymerase II. The Tat-TAR-dependent phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II contributes significantly to transcriptional elongation and post-transcriptional events [21].

Figure 1.

Representation of our hypothetical model of epigenetic modification of Tregs following infection by HIV-1.

Prior to coining the term, “single nucleotide polymorphism” (SNP), variations in coding and non-coding sequences of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) were used to delineate ancestral haplotypes [22]. Ongoing systematic analyses aimed to verify SNPs across MHC are critical for vaccine development. That short antigen oligopeptides bind specifically to different human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles representing varying ethnic populations, and are combinatorial in selection, helps to differentiate between self and non-self [3]. Advances in Bioinformatics yield algorithms for HLA specific short antigen peptide binding [4,23], and functional overlap across alleles at multiple levels as HLA super-types is complex given the over 2000 known HLA alleles and the extensive diversity across peptide constructs, and under continuing research [24]. For example, HLA-A to HLA-E genes, located in chromosome region 6p21.3, are associated with a large variety of diseases (e.g., vascular dementia, epilepsy, schizophrenia, diabetes, viral pathogenesis, cancer, graft vs. host disease). Additional conditions are distributed elsewhere on the same chromosome (cf., Table 1 under supplementary material)) [25]. In fact there seems to be a concentration of neuropsychiatric diseases located on this chromosome, whose collection of genes may interact in the NeuroAIDS process.

Conclusion

Taken together, the literature discussed above emphasizes the critical role of Tregs in the immunopathology of HIV/AIDS, and opens new potential modes of intervention based on manipulations of non-coding portions of the genome. It suggests the timely development of translational evidence-based epigenetic medicine [26], whose implications are discussed in the following paper from the specific viewpoint of the viropathology of AIDS and NeuroAIDS, and translational implications.

It is therefore important to note, in conclusion, that translational evidence-based decision-making in epigenetic medicine will in fact pertain beyond HIV/AIDS, including cancer and related pathologies. Case in point, the 100-1000X increased prevalence of carcinoma at the site of Oral Lichen Planus [27], an oral condition whose neuro-immunopathology we have examined extensively [28]. Cancer development at the sites of the lesions is particularly aggressive in proximity to recently placed titanium dental implant [27]. Whereas titanium is considered inert in most patients, it can produce significant epigenetic modulation in patients at risk, and it was proposed that such altered gene expression leads to the development of neoplasia [29].

The concepts articulated here in the domain of TH1/Th2 cytokine shift [30] and related immunopathological consequences of HIV/AIDS are coherent with the emergent principle of recursive genome function [31] further examined in the context of the viropathology of neuroAIDS [32].

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge advice from David Segal, PhD (University of Central Florida, Orlando, Florida); Eddy Rios, PhD (University of the Carribe, San Juan, Puerto Rico); Susan Plaeger, Ph.D. (NIH, Bethesda, MD). Support is acknowledged: FC: Alzheimer Association, University of California Senate, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Cuneo, and NIH (AI 07126 = CA16042, DA07683, DA10442); DC: NIH (NS 038841); and PS: NIH (DA14533, GM056529).

References

- 1.Rigoutsos I, et al. PNAS USA. 2006;103:6605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601688103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zou L, et al. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8451. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiappelli F. Immunity: In Encyclopeadia of Stress II. Oxford: Academic Press; 2007. p. 485. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng Y, et al. Nature. 2007;445:936. doi: 10.1038/nature05563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godfrey WR, et al. Blood. 2005;105:750. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Floess S, et al. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss L, et al. Blood. 2004;104:3249. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang L, et al. FASEB J. 2006;20:1513. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5504fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Favre-Bonvin A, et al. J Virol. 2005;79:4229. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4229-4237.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu S, et al. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:65. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2003.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girard JP, Springer TA. Immunol Today. 1995;16:449. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epple HJ, et al. Blood. 2006;108:3072. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lund RJ, et al. J Immunol. 2007;178:3648. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webster RB, et al. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609501200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Commins S, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1108. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watford WT, et al. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:139. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacchetta R, et al. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1713. doi: 10.1172/JCI25112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaneko T, et al. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:2249. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyatake S, et al. IUBMB Life. 2000;49:473. doi: 10.1080/15216540050166990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akimzhanov AM, et al. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens M, et al. Med Res Rev. 2006;26:595. doi: 10.1002/med.20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawkins R, et al. Immunol Rev. 1999;167:275. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kangueane P, Sakharkar MK. Bioinformation. 2005;1:21. doi: 10.6026/97320630001021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kangueane P, et al. Front Bioscience. 2005;10:879. doi: 10.2741/1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tiwari JL, Terasaki PI. HLA and Disease Associations. Berlin: Springer; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiappelli F. The Science of Research Synthesis: A Manual of Evidence-Based Research for the Health Sciences. NovaScience Publisher Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallego L, et al. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1061. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiappelli F, et al. Frontiers in Bioscence. 2005;10:3034. doi: 10.2741/1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGuff HS, et al. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1052. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Becker Y. Virus Genes. 2004;28:5. doi: 10.1023/B:VIRU.0000012260.32578.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pellionisz AJ. The Cerebellum. 2008;7:348. doi: 10.1007/s12311-008-0035-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shapshak P, et al. Bioinformation. 2008;3:53. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.