Abstract

Slits are a group of secreted glycoproteins that play a role in the regulation of cell migration. Previous studies suggested that Slit2 might be a tumor-suppressor gene. However, it remained to be determined whether Slit2 suppressed tumor growth and metastasis in animal models. We showed that Slit2 expression was decreased or abolished in human esophageal squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) compared to normal tissues by in situ hybridization. Stable transfection of human SCC A431 and fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells with Slit2 gene suppressed tumor growth in athymic nude mice. Apoptosis in Slit2-transfected tumors was increased, whereas proliferating cells were decreased, suggesting a mechanism for Slit2-mediated tumor suppression. This was supported by further analysis indicating that antiapoptotic molecules Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl and cell cycle molecules Cdk6 and Cyclin D1 were down-regulated in Slit2-transfected tumors. Furthermore, wound healing and Matrigel invasion assays showed that the transfection with Slit2 inhibited tumor cell migration and invasion. Slit2-transfected tumors showed a high level of keratin 8/18 and a low level of N-cadherin expression compared to empty vector-transfected tumors. More importantly, Slit2 transfection suppressed the metastasis of HT1080 tumor cells in lungs after intravenous inoculation. Collectively, our study has demonstrated that Slit2 inhibits tumor growth and metastasis of fibrosarcoma and SCC and that its effect on cell cycle and apoptosis signal pathways is an important mechanism for Slit2-mediated tumor suppression.

Introduction

Slits are secreted proteins that regulate axon guidance, branching, and neuronal migration during development of the central nervous system [1–5]. The Slit gene family consists of three genes, Slit1, Slit2, and Slit3. All are expressed in the nervous system but Slit2 and Slit3 can also be found in other tissues such as skin, lungs, and lymphoid organs [6,7]. Slits are ligands for transmembrane receptors, the Robo (round-about) gene family [8]. The interaction of Slits with Robos plays important roles in the regulation of cell migration in brain development and inflammatory responses [6,7,9].

A number of studies have demonstrated that Slit2 is epigenetically silenced in lung, breast, cervical, and colon cancers [10–13]. Ectopic expression of Slit2 suppresses colony formation of tumor cells in agarose cultures. The conditioned medium from Slit2-transfected cells reduces cell growth and induces apoptosis of colorectal carcinoma cell lines, implicating that Slit2 has tumor-suppressor activities [12]. However, some reports indicated that Slit2 expression was increased in prostate cancer, malignant melanoma, rectal mucinous adenocarcinoma, invasive breast carcinoma, gastric cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma [14,15]. Moreover, it was reported that tumor-derived Slit2 enhanced tumor angiogenesis, whereas neutralization of tumor-derived Slit2 suppressed human melanoma growth in animals [15]. Several issues remain to be determined. First, Slit2 is also expressed in normal tissues and its expression level can be increased by inflammations [6]. Because inflammations are commonly present in many tumors, the expression level of Slit2 in tumor samples, which may include normal tissues, may not be directly related to the expression of Slit2 by tumor cells, as assessed by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and Western blot analyses. Second, it is unknown whether Slit2 suppresses tumor growth in animal models, although Slit2 has been reported to inhibit the colony formation of tumor cells in cultures. Last, neutralization of Slits in the animal experiments might block not only the effect of tumor-derived Slit2 but also the endogenous Slit2 produced by normal tissues and cells [15]. It might lead to additive effects, which complicate the interpretation for the effect of tumor-derived Slit2.

A recent article reported that Slit2 inhibited CXCR4-mediated migration of breast cancer cells, suggesting that Slit2 may regulate tumor invasion and metastasis [16]. Another report showed that Slit2 suppressed the invasion of medulloblastoma cells [17]. However, it remains to be proven whether Slit2 affects tumor metastasis in vivo.

In the current study, we examined the Slit2 expression in human esophageal cancers including adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) by in situ hybridization to directly compare Slit2 expression level in normal and cancerous tissues. To examine the effect of Slit2 on tumor development, Slit2 gene was stably transfected into the human fibrosarcoma HT1080 and SCC A431 cells that were originally negative for Slit2. In vitro and in vivo data showed that Slit2 suppressed tumor growth and metastasis of human fibrosarcoma and SCC. In addition, further experiments indicated that Slit2-mediated effects on cell cycle, proliferation, and apoptosis signal pathways may be important mechanisms for its suppressive effects on tumors.

Materials and Methods

Tumor Specimens

Tissue specimens included a total of 211 tumor samples: 95 esophageal SCCs and 116 esophageal adenocarcinomas. Some of the tumor samples included adjacent or distant normal tissues; that is, there were 66 cases of normal esophageal mucosa. These samples were obtained from the Department of Pathology, University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center and from InnoGenex (San Ramon, CA). All samples were routinely fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 4-µm sections. Tumor samples were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for classification. Our institutional review board has approved a protocol for the use of the patient samples in an anonymous fashion for the study.

In Situ Hybridization

To detect Slit2 mRNA expression level, a nonradioactive in situ hybridization was performed as described previously [6,18]. Briefly, Slit2 cDNA fragment between 955 and 1685 bp was cloned into pGEM vector (Promega, Madison, WI). The plasmid was linearized by Apa I, and digoxigenin-labeled sense and antisense cRNA were generated by using SP6 polymerase in the presence of digoxigenin-UTP. Human retinoid X receptor-α (RXR-α) was used as a positive control for the intact tissue mRNA as described previously [18]. For in situ hybridization, the tissue sections were treated with 0.2 N HCl and proteinase K, respectively, after deparaffinization and rehydration. The slides were then postfixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and were acetylated in freshly prepared 0.25% acetic anhydride in a 0.1-M triethanolamine buffer. The slides were then prehybridized at 42°C with a hybridization solution containing 50% deionized formamide, 2x standard saline citrate (SSC), 2x Denhardt's solution, 10% dextran sulfate, 400 µg/ml yeast tRNA, 250 µg/ml salmon-sperm DNA, and 20 mM dithiothreitol in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water. Next, the slides were incubated in 50-µl per slide hybridization solution containing 20 ng of a freshly denatured dig-cRNA probe at 42°C for 4 hours. The slides were washed for 2 hours in 2x SSC containing 2% sheep serum and 0.05% Triton X-100 and then for 20 minutes at 42°C in 0.1x SSC. For color reaction, the slides were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature in 0.1 M maleic acid and 0.15 M NaCl containing 2% sheep serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 and then incubated overnight at 4°C with a sheep anti-digoxigenin antibody. After washing, color was developed in a solution containing 45 µl of nitroblue tetrazolium and 35 µl of an X-phosphate solution in 10 ml of buffer, which consisted of 0.1 M Tris, 0.1 M NaCl, and 0.05 M MgCl2 (pH 9.5) for 4 hours. The slides were then mounted with cover glass in Aqua mounting medium (Fisher, Houston, TX).

Section Review and Statistical Analysis

The stained sections were assigned as having positive or negative staining. Positive staining was defined as 10% or more of the epithelial cells stained positively. Statistical analysis was performed using the χ2 test to determine the association between normal and tumor tissues. The differences between normal and cancerous tissues were analyzed using χ2 test with Statistica (version 4.01) for PowerMac computer (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK).

Cell Culture and Transfection

The human fibrosarcoma HT1080 and SCC A431 cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Corporation (Manassas, VA) and cultured in minimum essential medium and Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, respectively. The plasmids encoding the full-length human Slit2 with a cMyc tag and empty control vector were reported in previous studies [6,19]. To establish stable transfectants of tumor cells, the Slit2 and control plasmids were transfected into HT1080 and A431 cells by electroporation using Nucleofector II (Amaxa, Cologne, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instruction. The human Slit2-transfected cells (HT1080/Slit2, A431/Slit2) and the control vector-transfected cells (HT1080/Vector, A431/Vector) were selected in cultures with graded concentrations of G418 (0.5–1.5 mg/ml). Stable transfectants were analyzed for the expression of Slit2 by RT-PCR and Western blot analyses.

Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

The expression of Slit2 and Robo4 mRNA in parental and transfected cells was determined by RT-PCR. Briefly, total RNA was isolated from tumor cells using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. First-strand DNA was synthesized using an Omniscript Reverse Transcriptase kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the instructions. The cDNA was then subjected to PCR amplification with the PLATINUM.PCR Supermix kit (Invitrogen). The following primers for human genes were used in the studies: Slit2: 5′-gacgactgccaagacaacaa-3′ and 5′-tgatagccaggcaaacactg-3′; Robo4: 5′-aaccacttctcctgtccacc-3′ and 5′-tcctccacttcctgtgatcc-3′. Reaction mixtures were subjected to the following amplification protocol: 1 cycle at 94°C for 4 minutes and 30 cycles at 94°C for 45 seconds, 58°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 60 seconds. The PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and the results were analyzed using a gel documentation system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). As controls, RNA samples without reverse transcription were subject to PCR to exclude DNA contamination.

Western Blot

To detect Slit2 proteins, parental HT1080, A431, and transfected cells were cultured until confluent. Cell culture supernatants were collected and filtered with a 0.22-µm filter. Samples were loaded onto 7.5% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked for 1 hour with phosphate-buffered saline containing 5% nonfat dry milk and 0.1% NP-40. The membranes were probed with anti-cMyc (9E10) monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). After washing, the blots were incubated with appropriate horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies. Protein bands were revealed by an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL).

To detect levels of Cdk6, Cyclin D1, and Bcl-xl in tumor tissues, tumor samples were harvested and ground in the RIPA buffer. Tumor lysates were subjected to Western blot using anti-Cdk6 (B-10), anti-Cyclin D1 (HD11; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-Bcl-xl antibodies (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Blots were quantified using Quantity one 1-D Analysis Software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The relative expression level of proteins was normalized to GAPDH in each sample.

Colony Formation Assay

Tissue culture plates (six-well plates) were precoated with 0.5% low-melting point agarose. Tumor cells were suspended in 0.35% agarose and were placed on top of the precoated agarose. After the agarose was solidified, 2 ml of complete growth medium was overlaid, and plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were fed weekly with complete growth medium. The number of colonies was counted microscopically approximately 3 weeks after culture.

Tumor Growth in Animals

Female athymic nude mice, 6 to 8 weeks old, were purchased from Frederick Cancer Research (Frederick, MD). Mice were injected subcutaneously with 2 x 106 HT1080 cells that were suspended in 50% Matrigel or 1 x 106 A431 in 30% Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Tumor growth was measured every 3 to 4 days using electronic calipers. Tumor volume was calculated as follows:

TUNEL Assay

Tumor samples were fixed in 10% formalin and sections (5 µm) were made. TUNEL assay was performed using a commercial apoptosis detection kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Sections were counterstained with DAPI, mounted, and photographed microscopically with a 10x objective. For negative control purposes, TdT enzyme was omitted from the reaction mixture. Samples treated with DNase I served as positive controls. The number of apoptotic cells was counted microscopically, and results from five fields of each group were calculated for statistical analysis.

Immunohistochemical Staining

Tumors tissues were fixed in formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Sections (7 µm) were cut by a Microtome, deparaffinized, and rehydrated as routines. Briefly, tissue sections were first incubated with blocking buffers to avoid nonspecific binding of antibodies and then incubated with antibodies specific to proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA; sc-9857), E-cadherin (sc7870), N-cadherin (sc-7939), Bcl-2 (sc-783), and Ck8/18 (MS-977; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Proliferating cell nuclear antigen-positive cells were detected by a peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody (Pierce) and visualized with Fast 3′3-Diaminobenzidine Tablet Set (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Sections were counterstained with H&E. Alexa Fluor 594-coupled secondary antibody (Invitrogen) was used to detect the other molecules. Sections were counterstained with a fluorescence DNA dye DAPI. Results were evaluated and pictures were taken microscopically with a digital camera using software from the manufacturer (Olympus, Pittsburgh, PA). The percent of PCNA-positive cells (PCNA+/total cells per field) was analyzed statistically from results of 10 fields in each sample.

Wound Healing Assay

Tumor cells were synchronized in serum free medium for 24 hours after confluence. The monolayers of cells were wounded by manual scratching with a 200-µl pipette tip, washed with PBS, placed in complete growth medium, and photographed with a digital camera connected to a phase-contrast microscope (4x objective). Matched pair-marked wound regions were photographed again after 6 hours. The distance of the scratch at the same position was measured by using the Image-Pro Plus software (4 points per well and 3 wells per sample, total measurement points: 12 points per sample). The migration index was calculated by the following formula: % Migration = (the length of initial wound - the length of wound after 6 h) x 100/the length of initial wound.

Matrigel Invasion Assay

Tumor cell invasion was measured with a Biocoat Matrigel invasion chamber (Becton Dickinson Labware, Bedford, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, tumor cells (2.5 x 104) in 0.5 ml of DMEM containing 0.1% BSA were seeded into the upper chamber, which had Matrigel-coated membrane, and 0.75 ml of DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum was added into the lower chamber. Epidermal growth factor was added as a chemokine in the lower chamber at 1 ng/ml in the assay for A431. After incubating for 24 hours at 37°C, membranes were collected and noninvading cells were removed from the upper surface of the membrane using a cotton swab. The membranes were then fixed with methanol, stained with 0.1% crystal violet, and photographed microscopically with a 10x objective. The number of invaded cells on the lower surface of the membrane was counted in 20 fields of four wells (HT1080) or 40 fields of four wells (A431).

Tumor Metastasis in Lungs

One million of parental, control vector-transfected, or Slit2-transfected HT1080 cells were injected intravenously in athymic nude mice through the tail vein. Five weeks after tumor injection, mice were killed and lungs were collected. Lungs were inflated and fixed in alcoholic formalin (10% of formalin and 63% of alcohol). Paraffin-embedded tissues were step-sectioned and sections were stained with H&E. Metastatic tumor nodules in the lungs were counted microscopically (24 sections of eight mice per group). The diameter of tumor nodules was measured with the Image-Pro Plus software (14 images of HT1080, 17 images of HT1080/Vector, and 5 images of HT1080/Slit2).

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in at least three independent assays, which yielded comparable results. Data are summarized as means ± SEM. Statistical analysis of the results was performed by Student's t test for unpaired samples. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression of Slit2 Is Reduced in Human Esophageal Cancers

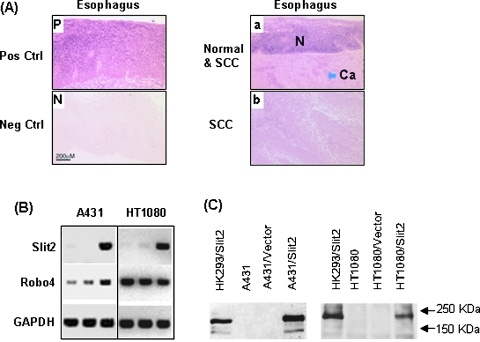

The expression level of Slit2 mRNA was examined in a total 211 cases of human tumor specimens and 66 cases of normal counterpart tissues by in situ hybridization. Slit2 was expressed in 83.3% (55/66) of normal esophageal mucosa, whereas its expression was significantly reduced in esophageal (92/211, 43%) cancers. Statistical analysis showed that the difference is significant between normal and esophageal SCC tissues (P = .00001). A representative figure (Figure 1A) shows that the adjacent normal tissues express a higher level of Slit2 than the cancerous tissues. We did further statistical analyses on the esophageal cancers, including sex, age, pathologic stage, lymph node and distant metastasis, tumor location, size, and differentiation of adenocarcinoma, SCC, and the combination. A statistically significant correlation was found between Slit2 expression with tumor differentiation status of SCC (P = .0025). These data indicate that the expression of Slit2 is inhibited in human esophageal cancers.

Figure 1.

Expression of Slit2 mRNA in normal and malignant esophageal tissues. (A) Slit2 mRNA was detected by in situ hybridization using digoxigenin-labeled antisense cRNA and positive cells are blue (Pos Ctrl). Sense cRNA was used as a negative control (Neg Ctrl). The normal esophageal epithelium (N) and SCC (Ca) are shown on the same section. Pictures were taken microscopically with a 10x objective. (B) Transcriptions of Slit2 and Robo4 in tumor cell lines HT1080 and A431 were detected by RT-PCR. The sample order of each cell line is parental, control vector-transfected, and Slit2-transfected cells. (C) Detection of cMyc-tagged Slit2 proteins. Slit2 proteins in culture supernatants of parental and transfected tumor cell lines were detected by Western blot using an anti-cMyc antibody. The supernatant of Slit2-transfected HK293 (HK293/Slit2) cells served as a positive control.

Human fibrosarcoma HT1080 and SCC A431 cells did not express Slit2 mRNA but did express Robo4, one of membrane ligands for Slit2 (Figure 1B). To evaluate the role of Slit2 on tumors, HT1080 and A431 cells were transfected with a vector-encoding human Slit2 gene or the empty control vector without insertion of Slit2 gene. Stable transfectants with Slit2 gene (HT1080/Slit2, A431/Slit2) or the control vector (HT1080/Vector, A431/Vector) were established in a selection medium containing G418. The expression of Slit2 mRNA was confirmed by RT-PCR. The Slit2 proteins in culture supernatants, which were tagged with a cMyc fragment, were detected by Western blot using a monoclonal antibody against cMyc (Figure 1C). The supernatant of Slit2-transfected 293 cells, which was reported in previous studies [6,19], was used as a positive control.

Slit2 Inhibits Tumor Growth

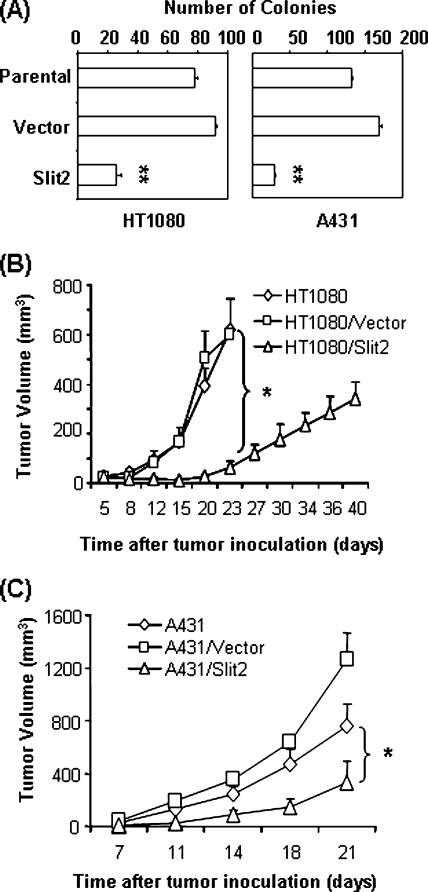

To examine the effects of Slit2 on the anchorage-dependent growth of tumor cells, parental and Slit2- or control vector-transfected tumor cells were cultured in tissue culture plates, and cell growth was evaluated by cell counting and ATPLite assay (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA). No significant difference was observed between the tumor cells (data not shown). To determine the effect of Slit2 on the anchorage-independent growth, the tumor cells were cultured in soft agar, and colony formation was measured in six-well plates (Figure 2A). Parental and control vector-transfected HT1080 cells had 77.5 ± 2.5 and 91.5 ± 1.5 colonies per well, respectively, whereas Slit2-transfected HT1080 cells formed 26 ± 3.0 colonies per well. Similarly, Slit2-transfected A431 cells had 29.33 ± 1.76 colonies per well compared to 132 ± 2.08 and 169 ± 4.04 colonies per well in cultures of parental and control vector-transfected A431 cells, respectively. The difference in the number of colonies is significant between Slit2-transfected and parental or control vector-transfected tumor cells (P < .01). These data demonstrate that Slit2 inhibits tumor cell growth in an anchorage-independent manner.

Figure 2.

Slit2 inhibits tumor growth. (A) Slit2 transfection inhibits colony formation of HT1080 and A431 cells in soft agar cultures. In the assessment of tumor growth in vivo, tumor cells were injected subcutaneously in athymic nude mice, and tumor growth was monitored. Transfection with Slit2 suppresses tumor growth of HT1080 (B) and A431 (C). Tumor volume is calculated as length x width x height x 0.63. Data are shown as mean ± SEM of four to five mice per group. *P < .05.

To test whether Slit2 inhibits tumor growth in vivo, parental, control vector-, or Slit2-transfected HT1080 and A431 cells were injected subcutaneously in athymic nude mice (four to five mice per group) and tumor growth was measured (Figure 2, B and C). Slit2 transfection significantly inhibited the growth of HT1080 and A431 tumors. At 23 days after injection, the volumes of parental and control vector-transfected HT1080 tumors reached 619.39 ± 130.4 and 600.43 ± 144.6 mm3, respectively. However, the volume of Slit2-transfected HT1080 tumors was only 64.25 ± 21.68 mm3 at the same time (Figure 2B). About a quarter of mice, which were injected with Slit2-transfected HT1080 cells, developed visible necrosis when the tumor volume reached approximately 400 mm3 at 34 days after injection. Thereafter, the tumor size shrank. Similar results were observed in mice that were injected with parental, control vector-, or Slit2-transfected A431 tumor cells (Figure 2C). At 21 days after injection, the tumor volume of mice injected with Slit2-transfected A431 cells was 201 ± 162 mm3 compared to 762.7 ± 160.3 and 1257 ± 205.7 mm3 in tumors of mice injected with parental and control vector-transfected A431 cells, respectively (P < .05). These results indicate that the forced expression of Slit2 inhibits tumor growth in animal models and support that Slit2 has tumor-suppressor effects on fibrosarcoma and SCC.

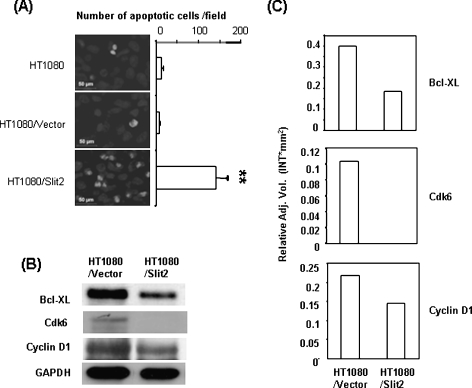

Slit2 Enhances the Apoptosis of Tumors

The regulation of apoptosis and angiogenesis has been suggested for Slit2-mediated effects on tumors [12,15]. Our initial experiments did not show a significant difference in apoptotic cells between Slit2-transfected and control cells in cultures, as assessed by staining with Annexin V and 7-AAD in a flow cytometer (data not shown). It was not in consistent with the report, which showed Slit2-mediated apoptosis of tumor cells in cultures [12]. However, a significantly higher number of apoptotic cells was observed in Slit2-transfected HT1080 tumors than in the control tumors, which were collected from nude mice (Figure 3A). In a further analysis of tumor lysates, antiapoptotic Bcl-xl and cell cycle signal molecules Cdk6 and Cyclin D1 were found to be down-regulated in Slit2-transfected HT1080 tumors compared to the controls (Figure 3, B and C). These data implicate that Slit2-mediated regulation of apoptosis and cell cycle signal pathways are important mechanisms for its tumor-suppressive effects. A significant change in the density of blood vessels was not observed between Slit2-transfected and control HT1080 tumors by immunohistochemical staining with anti-CD31 antibodies (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Slit2 enhances tumor apoptosis. (A) Athymic mice were injected subcutaneously with HT1080 tumor cells. Tumors were removed 2 weeks after inoculation, and paraffin-embedded sections were made. Apoptotic cells of tumor samples were determined by TUNEL assay. The number of apoptotic cells was counted microscopically in five fields. **P < .005. (B) HT1080 tumor tissues were collected, and tumor lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis. Bcl-xl, Cdk6, and Cyclin D1 were down-regulated in tumors of mice injected with Slit2-transfected HT1080 cells. (C) The relative levels of proteins in each sample were determined by Quantity one 1-D Analysis Software and were normalized to GAPDH.

Slit2 Inhibits Tumor Metastasis

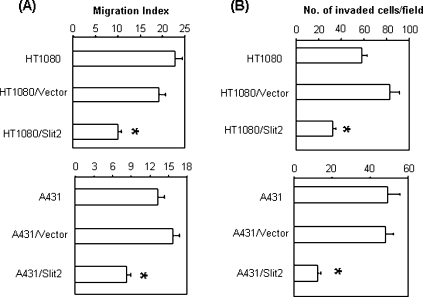

Increased cell motility is associated with malignancy and metastatic potential of tumor cells [20]. There were reports indicating that Slit2 inhibited the migration of tumor cells in vitro [16,17]. To examine whether Slit2 inhibited tumor metastasis, in vitro and in vivo experiments were conducted with the Slit2-transfected HT1080 and A431 tumor cells.

In a wound healing assay that measures cell migration, Slit2 transfection significantly inhibited the migration of tumor cells compared to the controls (Figure 4A). In further experiments that examined the invasiveness of tumor cells, we found that parental and control vector-transfected tumor cells efficiently penetrated the Matrigel-coated membrane, whereas the penetration rate of Slit2-transfected tumor cells was significantly reduced (Figure 4B). Identical results were observed with both HT1080 and A431 tumor cells, implicating that Slit2 inhibits the migration and invasiveness of both tumor cells.

Figure 4.

Slit2 inhibits tumor cell migration and invasion. (A) Migration of tumor cells was assessed by wound healing assay. Migration index was calculated as described in the Materials and Methods section. *P < .001. (B) Invasiveness of tumor cells was determined by using a two-chamber Matrigel system. Tumor invasion was evaluated at 24 hours after culture. The number of invaded cells was counted microscopically in 20 (HT1080) or 40 fields (A431). *P < .001.

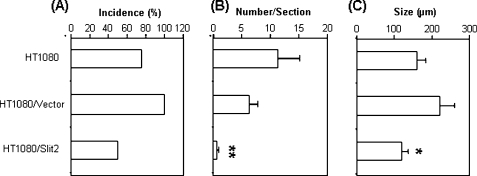

To further determine the effect of Slit2 on tumor metastasis in vivo, parental, control vector-, or Slit2-transfected HT1080 cells were injected intravenously in athymic nude mice [21]. Pulmonary metastatic nodules were found in six of eight and in all seven mice that were injected with parental and control vector-transfected HT1080 cells, respectively. In contrast, four of eight mice that were injected with Slit2-transfected HT1080 cells developed lung metastasis (Figure 5A). Slit2-transfected HT1080 cells also formed significantly less pulmonary metastatic nodules than the parental and control vector-transfected cells (Figure 5B). Moreover, the size of the metastatic tumor nodules in mice that were injected with Slit2-transfected HT1080 tumor cells was significantly smaller than those of mice that were injected with parental or control vector-transfected cells (Figure 5C). These results provide evidence that Slit2 inhibits tumor metastasis in our animal models.

Figure 5.

Slit2 inhibits tumor metastasis in lungs. Athymic mice were injected intravenously with HT1080 tumor cells and lungs were harvested 4 to 5 weeks later for the assessment of tumor metastasis. Paraffin-embedded lung sections were stained with H&E. Tumor nodules were evaluated microscopically. (A) Incidence of mice with metastatic tumors in lungs. Data indicate the percentage of mice with metastatic tumor nodules in lungs (eight mice per group). (B) The number of metastatic tumor nodules per section was counted microscopically. Analysis of data is based on 24 sections per group (mean ± SEM). **P < .01 compared to both control groups. (C) Size of metastatic tumor nodules in lungs. Data indicate the average size (diameter) of tumor nodules of eight mice (mean ± SEM). *P < .05 compared to the size of tumor nodules in lungs of mice injected with control vector-transfected cells.

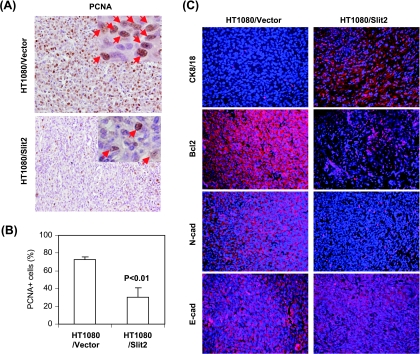

To examine the mechanisms by which Slit2 reduces the invasive and metastatic phenotype of tumors, we detected the expression of keratin-8/18, E-cadherin (the markers of epithelial phenotype) and N-cadherin (a marker of mesenchymal phenotype), PCNA (a marker of proliferation), and Bcl-2 (an antiapoptosis molecule) [22,23]. Results showed that the number of PCNA-positive cells was significantly lower in Slit2-transfected than in control vector-transfected HT1080 tumors (Figure 6, A and B). The expression of keratin-8/18 was remarkably increased, whereas the expression N-cadherin was drastically reduced in Slit2-transfected compared to vector-transfected HT1080 tumors (Figure 6C). The expression of the antiapoptotic molecule Bcl-2 was also decreased, whereas E-cadherin was not altered (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Slit2 regulates the expression of molecules related to growth, apoptosis, invasiveness, and metastasis of tumors. Athymic mice were injected subcutaneously with tumor cells. Tumors were removed 2 weeks after inoculation, and paraffin-embedded sections were made and stained. (A) Proliferating cells of tumor samples were detected by anti-PCNA antibody. Sections were counterstained with H&E, and PCNA-positive cells were brown as indicated by arrows in the islets. (B) The number of PCNA-positive cells was counted microscopically in 10 fields and was statistically analyzed. (C) Keratin-8/18 (Ck8/18), Bcl-2, N-cadherin (N-cad), and E-cadherin (E-cad) were stained with fluorescence-labeled antibodies (red). Sections were counterstained with a fluorescence DNA dye DAPI (blue).

Discussion

In the current study, we have demonstrated that the expression of Slit2 in human esophageal adenocarcinoma and SCC is reduced compared to normal tissues in a large group of clinical samples. Forced expression of Slit2 suppresses the growth andmetastasis of human fibrosarcoma HT1080 and SCC A431 cells in vitro and in animal models.

Our in situ hybridization analysis has shown that the expression of Slit2 mRNA is decreased in esophageal tumors compared to the normal tissues and even adjacent normal tissues within tumor samples. Previous studies showed that Slit2 promoter region was hypermethylated in colorectal, lung, and breast cancers and gliomas and that the treatment of these tumor cell lines with demethylating agents increased the expression of Slit2 mRNA [12,13,24,25]. In contrast, Wang et al. [15] reported that Slit2 expression was increased in some tumors including melanoma as assessed by RT-PCR and Western blot analyses using an anti-Slit2 antibody. One explanation for the discrepancy is that Slit2 is expressed constitutively by normal tissues, primarily by endothelial and epithelial cells [6,7,19]. This is confirmed by in situ hybridization in the current study (Figure 1A). Tumor samples applied in the previous report might contain some normal tissues. Therefore, the Slit2 mRNA level in a tumor sample may be affected by the portion of normal tissues within a tumor sample. In the current study, using in situ hybridization, direct comparison of cancerous with normal adjacent tissues in tumor samples revealed that Slit2 expression was decreased in tumor cells. In our initial experiments examining Slit2 mRNA levels by RT-PCR, virtually all tumor samples expressed Slit2 at different levels (data not shown). In addition, our previous studies indicated that Slit2 could be up-regulated by inflammatory stimulation [6]. Leukocyte infiltration and inflammation in tumor tissues, which are common features in tumors, may have effects on the expression of Slit2 by normal cells in tumor samples. We tried four different commercially available anti-Slit2 antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to detect Slit2 proteins in human tissues and our Slit2-transfected tumor lines by immunohistochemical staining. None of them could yield positive signals (data not shown). Therefore, in situ hybridization technique provides a direct comparison between normal and cancerous tissues and may yield more accurate results of Slit2 expression by tumor cells than detection of Slit2 in whole tumor tissue samples by RT-PCR or Western blot. Certainly, application of specific antibodies, when they are available, will provide further confirmation for the conclusion.

It was reported that the transfection of tumor cells with Slit2 gene inhibited the colony formation in a selection culture medium containing zeocin [12,13,25]. Moreover, conditioned medium from Slit2- transfected COS-7 cells reduced cell growth and induced apoptosis of colorectal tumor cells [12]. However, it remains to be determined whether Slit2 affected tumor growth in vivo. Our study indicated that the stable transfection of tumor cells with Slit2 did inhibit colony formation in agarose cultures. Most importantly, our data have indicated that in nude mice, the growth of Slit2-transfected fibrosarcoma HT1080 and SCC A431 cells is significantly inhibited compared to that of parental or the control vector-transfected tumor cells. Because our results showed that most human tumor cells, including HT1080 and A431, expressed Robo4, Slit2 may mediate effects on tumor cells through interactions with Robo4. Robo1, 2, and 3 were detected only in a few cell lines (data not shown). Our ongoing studies will further determine how interactions of Slit2 with Robo4 regulate tumors.

The inhibition of tumor growth by Slit2 transfection is not in consistent to the report by Wang et al. [15] wherein neutralization of Slit2 inhibited tumor growth. In their report, A375 human melanoma cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding RoboN, a soluble form of Robo1 receptor that could bind to Slit2 and block its activities. They found that transfection with RoboN inhibited tumor growth in nude mice compared to controls. Furthermore, they found that Slit2 increased the migration of endothelial cells and enhanced angiogenesis in tumors. Therefore, neutralization of Slit2 by RoboN inhibited angiogenesis and suppressed tumor growth [15]. Our study used fibrosarcoma HT1080 and SCC A431 cells that originally did not express Slit2 and differed from the reported study in several ways. First, our study show that Slit2 has a direct inhibitory effect on tumors as indicated by the reduction of colony formation in the agarose cultures. In the reported study, Slit2 did not have a direct effect on tumor cells. Instead, Slit2-mediated effects were to induce the migration of normal endothelial cells and increase tumor angiogenesis by Slit2-Robo1 signaling. However, conflicting results were reported in a study indicating that Slit2 inhibited the migration of endothelial cells [26]. In our experiments, we could not detect a significant change in the density of blood vessels between Slit2-transfected and control tumor tissues (data not shown). Second, our findings demonstrate that Slit2 affects tumor invasion and metastasis. This adds support to previous reports indicating that Slit2 inhibited the migration and invasion of tumor cells in in vitro studies [16,17]. Third, our data show that the number of PCNA-positive cells, which represents proliferating cells, is significantly lower in Slit2-transfected than in control vector-transfected tumors. Finally, it is not excluded that Slit2 may have different effects on different types of tumor cell lines. Certainly, further studies are required for clarification of the issue.

Previous reports indicated that conditioned medium from Slit2-transfected cells induced apoptosis of colorectal tumor cells in cultures [12]. Although we could not detect a significant increase of apoptosis in Slit2-transfected tumor cells compared to the controls in cultures, apoptosis in the tumors of Slit2-transfected HT1080 cells was significantly increased (Figure 3A). Moreover, antiapoptotic molecules Bcl-xl and Bcl2 and cell cycle regulators Cdk 6 and Cyclin D1 were reduced in Slit2-transfected HT1080 tumors compared to controls. Bcl-xl belongs to the Bcl-2 family of proteins and has been known to inhibit apoptosis signal pathways [27,28]. Cyclin D1 is a proto-oncogenic regulator of the G1-S phase checkpoint in the cell cycle, which has been implicated as a potential oncogene in the pathogenesis of several types of cancers [29,30]. Cyclin D1 in cooperation with its major catalytic partners, Cdk4 and Cdk6, facilitates progression through the G1 phase of the cell cycle. The activity or amount of Cdk6 was reported to be elevated in cancer cells [31,32]. Our data indicate that Slit2-mediated regulation of apoptosis and cell cycle signaling pathways may be an important mechanism for Slit2-induced tumor suppression. Because cell cycle and apoptosis are closely related, further studies are required for the dissection of Slit2-mediated specific molecular mechanisms for the signal pathways.

Tumor metastasis is a process involving complexes of cascade events, which include migration, invasion, and growth in distal organs [33]. Our data indicate that Slit2 inhibits the migration and invasion of fibrosarcoma (HT1080) and SCC (A431). Similar results have been reported in studies of breast cancer and medulloblastoma cells [16,17], supporting that Slit2 inhibits the mobility of tumor cells. Furthermore, Slit2 transfection increases the expression of epithelial differentiation markers (keratin 8 and keratin 18) but decreases the level of mesenchymal marker (N-cadherin) of HT1080 tumors. This indicates that Slit2 suppresses the invasive mesenchymal phenotype of HT1080 tumors to a less invasive epithelial phenotype, a phenomenon reported in recent studies [22,23]. Slit2 transfection not only decreases the number but also reduces the size of metastatic tumors in lungs. This implies that Slit2-mediated inhibition of tumor growth and increase of tumor apoptosis may also be involved in the development of metastatic tumor cells in distal organs. Therefore, Slit2 suppresses tumor metastasis by a mechanism that involves the regulation of tumor migration, invasion, apoptosis, and growth.

In summary, our study demonstrates that Slit2 is a tumor-suppressor gene that inhibits the growth and metastasis of human fibrosarcoma and SCC. Slit2 is expressed by normal esophageal tissues, and its expression level is decreased in esophageal adenocarcinoma and SCC. Introduction of Slit2 gene into HT1080 and A431 cells, which are defect in Slit2 production, suppresses tumor growth and metastasis in cultures and in animal models. Furthermore, Slit2 inhibits the expression of anti-apoptosis and cell cycle signal molecules in tumor cells, which represent important mechanisms for Slit2-mediated suppression and apoptosis of tumors. The current studies provide new insights into the mechanisms of Slit2-mediated effects on tumors, and these may be exploited to new therapeutic strategies for tumors.

Abbreviations

- Robo

roundabout proteins

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- SCC

squamous cell carcinoma

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AR46256, AI52920, and DOD to H.X. and R01-ES-015323 to M.A.

References

- 1.Yuan W, Zhou L, Chen JH, Wu JY, Rao Y, Ornitz DM. The mouse SLIT family: secreted ligands for ROBO expressed in patterns that suggest a role in morphogenesis and axon guidance. Dev Biol. 1999;212:290–306. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guthrie S. Axon guidance: Robos make the rules. Curr Biol. 2001;11:R300–R303. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zinn K, Sun Q. Slit branches out: a secreted protein mediates both attractive and repulsive axon guidance. Cell. 1999;97:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80707-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giger RJ, Kolodkin AL. Silencing the siren: guidance cue hierarchies at the CNS midline. Cell. 2001;105:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brose K, Bland KS, Wang KH, Arnott D, Henzel W, Goodman CS, Tessier-Lavigne M, Kidd T. Slit proteins bind Robo receptors and have an evolutionarily conserved role in repulsive axon guidance. Cell. 1999;96:795–806. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan H, Zu G, Xie Y, Tang H, Johnson M, Xu X, Kevil C, Xiong WC, Elmets C, Rao Y, et al. Neuronal repellent Slit2 inhibits dendritic cell migration and the development of immune responses. J Immunol. 2003;171:6519–6526. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu JY, Feng L, Park HT, Havlioglu N, Wen L, Tang H, Bacon KB, Jiang Z, Zhang X, Rao Y. The neuronal repellent Slit inhibits leukocyte chemotaxis induced by chemotactic factors. Nature. 2001;410:948–952. doi: 10.1038/35073616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein E, Tessier-Lavigne M. Hierarchical organization of guidance receptors: silencing of netrin attraction by slit through a Robo/DCC receptor complex. Science. 2001;291:1928–1938. doi: 10.1126/science.1058445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong K, Park HT, Wu JY, Rao Y. Slit proteins: molecular guidance cues for cells ranging from neurons to leukocytes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:583–591. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh R, Indra D, Mitra S, Mondal R, Basu P, Roy A, Roychowdhury S, Panda C. Deletions in chromosome 4 differentially associated with the development of cervical cancer: evidence of slit2 as a candidate tumor suppressor gene. Hum Genet. 2007;122:71. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narayan G, Goparaju C, Arias-Pulido H, Kaufmann AM, Schneider A, Durst M, Mansukhani M, Pothuri B, Murty VV. Promoter hypermethylation-mediated inactivation of multiple Slit-Robo pathway genes in cervical cancer progression. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dallol A, Morton D, Maher ER, Latif F. SLIT2 axon guidance molecule is frequently inactivated in colorectal cancer and suppresses growth of colorectal carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1054–1058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dallol A, Da Silva NF, Viacava P, Minna JD, Bieche I, Maher ER, Latif F. SLIT2, a human homologue of the Drosophila Slit2 gene, has tumor suppressor activity and is frequently inactivated in lung and breast cancers. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5874–5880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Latil A, Chene L, Cochant-Priollet B, Mangin P, Fournier G, Berthon P, Cussenot O. Quantification of expression of netrins, slits and their receptors in human prostate tumors. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:306–315. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang B, Xiao Y, Ding BB, Zhang N, Yuan X, Gui L, Qian KX, Duan S, Chen Z, Rao Y, et al. Induction of tumor angiogenesis by Slit-Robo signaling and inhibition of cancer growth by blocking Robo activity. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prasad A, Fernandis AZ, Rao Y, Ganju RK. Slit protein-mediated inhibition of CXCR4-induced chemotactic and chemoinvasive signaling pathways in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9115–9124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Werbowetski-Ogilvie TE, Seyed Sadr M, Jabado N, Angers-Loustau A, Agar NY, Wu J, Bjerkvig R, Antel JP, Faury D, Rao Y, et al. Inhibition of medulloblastoma cell invasion by Slit. Oncogene. 2006;25:5103–5112. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu H, Zhang W, El-Naggar AK, Lippman SM, Lin P, Lotan R, Xu X-C. Loss of retinoic acid receptor-{beta} expression is an early event during esophageal carcinogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1519–1523. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65467-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li HS, Chen JH, Wu W, Fagaly T, Zhou L, Yuan W, Dupuis S, Jiang ZH, Nash W, Gick C, et al. Vertebrate slit, a secreted ligand for the transmembrane protein roundabout, is a repellent for olfactory bulb axons. Cell. 1999;96:807–818. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poste G, Fidler IJ. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis. Nature. 1980;283:139–146. doi: 10.1038/283139a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chao TC, Greager JA. Experimental pulmonary sarcoma metastases in athymic nude mice. J Surg Oncol. 1997;65:123–126. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199706)65:2<123::aid-jso9>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo Y, Xie J, Rubin E, Tang Y-X, Lin F, Zi X, Hoang BH. Frzb, a secreted Wnt antagonist, decreases growth and invasiveness of fibrosarcoma cells associated with inhibition of Met signaling. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3350–3360. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christiansen JJ, Rajasekaran AK. Reassessing epithelial to mesenchymal transition as a prerequisite for carcinoma invasion and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8319–8326. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Astuti D, Da Silva NF, Dallol A, Gentle D, Martinsson T, Kogner P, Grundy R, Kishida T, Yao M, Latif F, et al. SLIT2 promoter methylation analysis in neuroblastoma, Wilms' tumour and renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:515–521. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dallol A, Krex D, Hesson L, Eng C, Maher ER, Latif F. Frequent epigenetic inactivation of the SLIT2 gene in gliomas. Oncogene. 2003;22:4611–4616. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park KW, Morrison CM, Sorensen LK, Jones CA, Rao Y, Chien CB, Wu JY, Urness LD, Li DY. Robo4 is a vascular-specific receptor that inhibits endothelial migration. Dev Biol. 2003;261:251–267. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gross A, McDonnell JM, Korsmeyer SJ. BCL-2 family members and the mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1899–1911. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.15.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boise LH, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Postema CE, Ding L, Lindsten T, Turka LA, Mao X, Nunez G, Thompson CB. bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 1993;74:597–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90508-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motokura T, Bloom T, Kim HG, Juppner H, Ruderman JV, Kronenberg HM, Arnold A. A novel cyclin encoded by a bcl1-linked candidate oncogene. Nature. 1991;350:512–515.. doi: 10.1038/350512a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vermeulen K, Van Bockstaele DR, Berneman ZN. The cell cycle: a review of regulation, deregulation and therapeutic targets in cancer. Cell Prolif. 2003;36:131–149. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2184.2003.00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corcoran MM, Mould SJ, Orchard JA, Ibbotson RE, Chapman RM, Boright AP, Platt C, Tsui LC, Scherer SW, Oscier DG. Dysregulation of cyclin dependent kinase 6 expression in splenic marginal zone lymphoma through chromosome 7q translocations. Oncogene. 1999;18:6271–6277. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lien HC, Lin CW, Huang PH, Chang ML, Hsu SM. Expression of cyclin-dependent kinase 6 (cdk6) and frequent loss of CD44 in nasalnasopharyngeal NK/T-cell lymphomas: comparison with CD56-negative peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Lab Invest. 2000;80:893–900. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steeg PS. Tumor metastasis: mechanistic insights and clinical challenges. Nat Med. 2006;12:895. doi: 10.1038/nm1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]