Abstract

Propagation of intercellular calcium waves (ICW) between astrocytes depends on the diffusion of signaling molecules through gap junction channels and diffusion through the extracellular space of neuroactive substances acting on plasmalemmal receptors. The relative contributions of these two pathways vary in different brain regions and under certain pathological conditions. We have previously shown that in wild-type spinal cord astrocytes, ICW are primarily gap junction-dependent, but that deletion of the main gap junction protein (Cx43) by homologous recombination results in a switch in mode of ICW propagation to a purinoceptor-dependent mechanism. Such a compensatory mechanism for ICW propagation was related to changes in the pharmacological profile of P2Y receptors, from an adenine-sensitive P2Y1, in wild-type, to a uridine-sensitive P2U receptor subtype, in Cx43 knockout (KO) astrocytes. Using oligonucleotide antisense to Cx43 mRNA for acute downregulation of connexin43 expression levels, we provide evidence for the molecular nature of such compensatory mechanism. Pharmacological studies and Western blot analysis indicate that there is a reciprocal regulation of P2Y1 and P2Y4 expression levels, such that downregulation of Cx43 leads to decreased expression of the adenine-sensitive P2Y1 receptor and increased expression of the uridine-sensitive P2Y4 receptor. This change in functional expression of the P2Y receptor subtype population in acutely downregulated Cx43 was paralleled by changes in the mode of ICW propagation, similar to that previously observed for Cx43 KO spinal cord astrocytes. On the basis of these results, we propose that Cx43 regulates both modes of ICW by altering P2Y receptor subtype expression in addition to providing intercellular coupling.

Keywords: gap junction, purinoceptor, calcium waves, antisense oligonucleotides, dye coupling, electrical coupling

INTRODUCTION

One prominent way by which astrocytes regulate their own activity and influence neuronal behavior is via Ca2+ signals, which may be restricted within one cell or transmitted throughout the interconnected syncytium via the propagation of intercellular calcium waves (ICW). There are two main routes by which calcium waves can propagate from one cell to another: (1) through intercellular gap junction channels involving the diffusion of signaling molecules (e.g., IP3, Ca2+, cADP ribose) generated in one cell to the adjacent ones (Saez et al., 1989; Christ et al., 1992; Churchill and Louis, 1998); and (2) through the extracellular space involving the release of pharmacologically active substances (e.g., ATP) from one cell activating plasmalemmal receptors on neighboring cells (Osipchuk and Cahalan, 1992; Hassinger et al., 1996; Guthrie et al., 1999).

Connexin43 (Cx43) is the main gap junction protein expressed between astrocytes (Dermietzel, 1996; Spray, 1996; Spray et al., 1998; Dermietzel et al., 2000), with Cx43 channels contributing 95–70% of total junctional conductance (Spray et al., 1998; Scemes et al., 2000). It is also more permissive to diffusion of negatively charged molecules such as IP3 than are the channels formed by other connexins (Cx45, Cx30, Cx26:Veenstra et al., 1994; Beblo et al., 1995; Beblo and Veenstra, 1997; Wang and Veenstra, 1997) expressed in these cells (Kunzelmann et al., 1999; Dermietzel et al., 2000; Nagy et al., 2001). At least four metabotropic P2Y receptors subtypes are expressed in astrocytes: one selective for purine nucleotides (P2Y1: Neary et al., 1988; Neary et al., 1991; Pearce et al., 1989; Pearce and Langley, 1994; Bruner and Murphy, 1990; Shao and McCarthy, 1993; Ciccarelli et al., 1994; Idestrup and Salter, 1998; Jimenez et al., 2000) and three sensitive to pyrimidine nucleotides (P2Y2/4, P2Y6: Pearce and Langley, 1994; Ho et al., 1995; Wu and Sun, 1997; Jimenez et al., 2000; Lenz et al., 2000). Each of these receptors is coupled through phospholipase C (PLC) to IP3 generation (Salter and Hicks, 1995; Idestrup and Salter, 1998; Jimenez et al., 2000).

Under different pathological conditions, such as inflammation and neurodegenerative disorders, the expression levels of connexins and purinergic receptors are altered, thus affecting the relative contribution of the two pathways for Ca2+ signaling between astrocytes (John et al., 1999). Similarly, a shift in mode of Ca2+ transmission, paralleled by changes in pharmacological profile of the population of P2Y receptors from an adenine-sensitive P2Y1-like to an uridine-sensitive P2Y2/4-like receptor subtype, was observed to occur in spinal cord astrocytes from mice in which Cx43 was deleted by homologous recombination (Scemes et al., 2000). These observations led us to propose that there is a compensatory mechanism for intercellular calcium signaling involving gap junction proteins (connexins) and P2Y receptors. To evaluate the nature of such interplay between connexins and P2Y receptors, we have acutely downregulated Cx43 expression levels and analyzed the expression levels of P2Y receptors. This report shows that the changes in P2Y receptor pharmacology that occur when Cx43 is acutely down-regulated are related to reciprocal changes in the expression levels of P2Y1 and P2Y4 receptors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Astrocyte Cultures

Spinal cord astrocytes from wild-type (WT) and Cx43 knockout (KO) neonatal mice (C57BL/6J-Gja1strain, heterozygotes were originally obtained from Jackson Laboratories and from colonies maintained at the Albert Einstein Animal Facility; all experimental procedures were approved by the AECOM Animal Care and Use Committee). Cervical to lumbar vertebrae were dissected and spinal cord segments extruded from the vertebrae using fine forceps. After removal of meninges, spinal cord tissues were digested in 0.025% collagenase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) for 10 min at 37°C. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 2,000 rpm for 2 min at room temperature. The final pellet was suspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotics and cells seeded on tissue culture dishes. About 95–98% of cells in cultures were immunopositive for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). Cortical astrocytes when used were prepared as previously described (Scemes and Spray, 1998). Studies were performed on astrocytes maintained for 2–3 weeks in culture.

Acute Regulation of Astrocytic Coupling

Antisense oligonucleotide treatments

Phosphorothioated oligonucleotides (ONs) were synthesized using phosphoramidite chemistry and specific reagents (Gene Link, Hawthorne, NY). The antisense (AS)-ONs were added at a final concentration of 3.0 μM (a dose that maximally decreased dye coupling and Cx43 expression levels; see Figs. 1 and 5) and Lipofectamine2000 used to introduce the oligonucleotides into the cells. Untreated (control), mock-treated (exposed to Lipofectamine reagent), and sense (S)-ON-treated cultures were established in parallel. Petri dishes containing the cells were stored at 37°C in 5% CO2 until use (48 h after the addition of ONs). To selectively reduce expression of Cx43, AS-ONs (19 mers) to sequences of mouse Cx43 mRNA that are unique for this connexin were employed. The two oligonucleotides antisense to the RNA corresponding to exon1 and exon2 of the mouse connexin43 DNA used were, respectively: 5′TACTTCCCTCACGCCTTTC3′ and 5′ATTCAGAGCGAGAGACACC3′. Two Cx43 sense oligonucleotides (S-ONs; termed S1 and S2) with the same but inverted sequence of nucleotides as the two AS-ONs (AS1, AS2) were employed as negative controls.

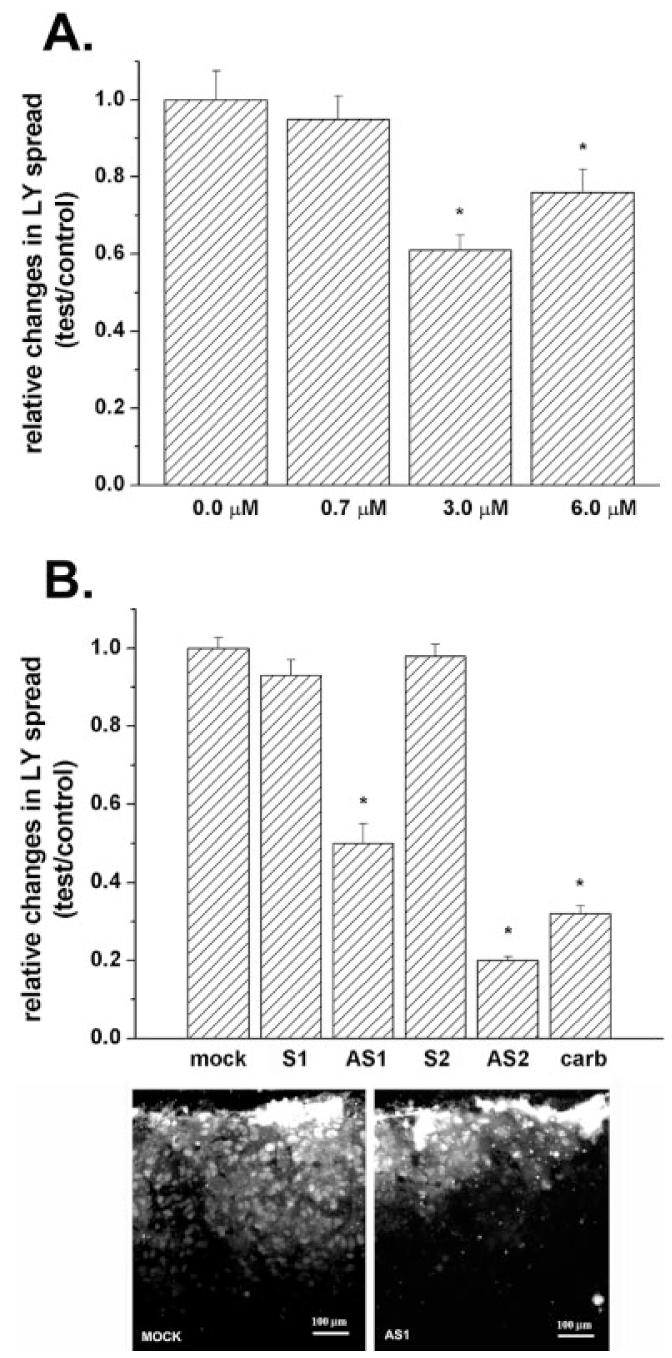

Fig. 1.

Decreased dye coupling between cortical astrocytes induced by treatment with Cx43 antisense oligonucleotides. A: Mean values of the relative changes in LY spread between astrocytes exposed for 48 h to increased concentrations of oligonucleotide antisense to the mRNA corresponding to the exon1 of Cx43 DNA; note that only at 3.0 μM did the antisense induce a significant reduction (about 40%) in dye coupling and that increasing antisense concentration to 6.0 μM did not further decrease LY spread. Changes in LY spread were normalized against the distance of LY spread obtained under control (untreated) conditions. B: Mean values of the relative changes in LY spread induced by 48-h exposure of cortical astrocytes to 3.0 μM oligonucleotides, one antisense to the mRNA corresponding to exon1 (AS1) and the other to exon2 (AS2) of Cx43 DNA; the two sense-oligonucleotides (S1 and S2) employed to control for nonspecific effects had the same but inverted sequence of nucleotides as the two antisense oligonucleotides (AS-ONs). Note that dye coupling between mock- and sense-treated astrocytes was not significantly different from that obtained for control, untreated cultures and that both AS-ONs significantly reduced LY spread to levels comparable to that observed in untreated cultures exposed to 100 μM carbenoxolone (carb; a gap junction channel blocker). An example of dye coupling observed in control and in AS1-treated cultures is shown on the micrograph below. The histograms bars correspond to the mean values and standard errors of 30 measurements of LY spread. *P < 0.001 (one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA], followed by the Tukey test).

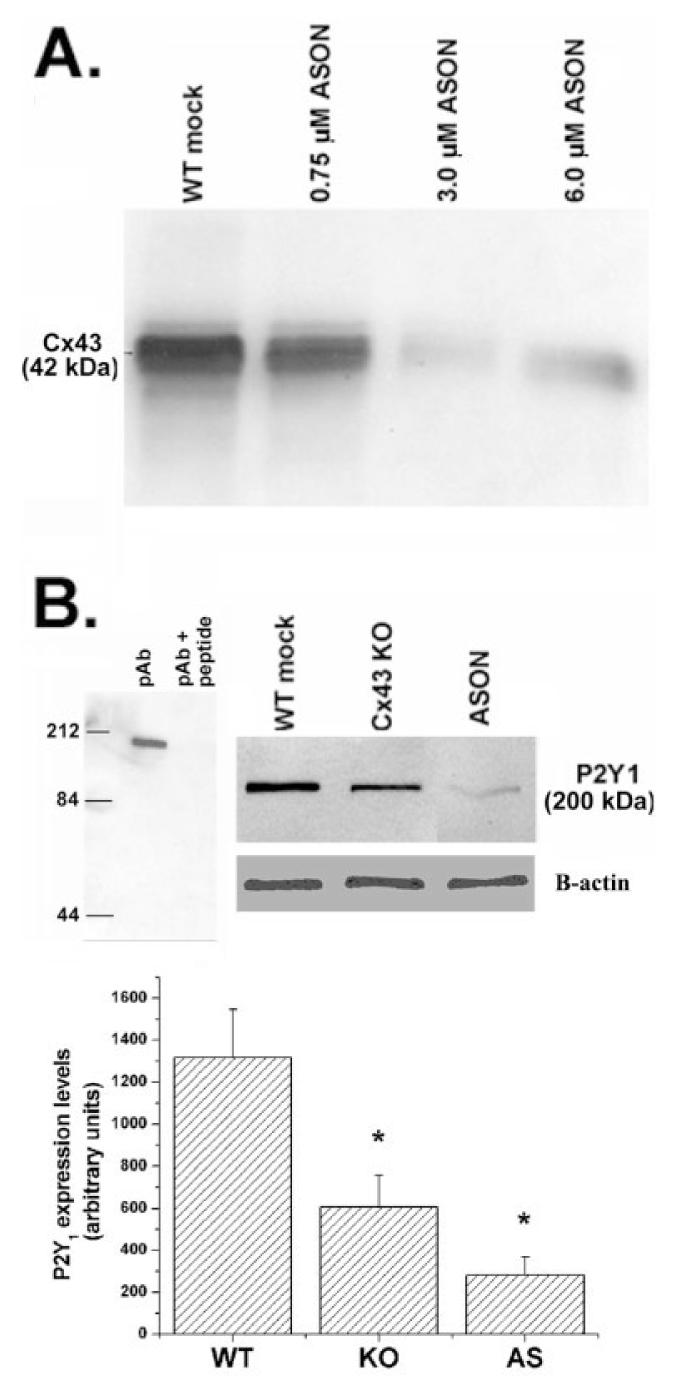

Fig. 5.

Decreased expression levels of P2Y1 receptors in spinal cord astrocytes after Cx43 downregulation. A: Representative Cx43 immunoblot obtained from whole cell homogenate of confluent cultures of spinal cord astrocytes treated for 48 h with indicated concentrations of oligonucleotides antisense to the mRNA corresponding to exon1 of Cx43 DNA. Note that 3.0 μM was the most effective concentration of AS1 to reduce Cx43 expression levels. B: Upper portion (left) shows immunoblot demonstrating that preabsortion of P2Y1 antibody (pAb) with immunogenic peptide abolishes the 200-kDa band; upper right shows an immunoblot with P2Y1 and β-actin antibodies under different conditions. Bar histogram (below) representing the mean values and standard errors of three to four independent experiments obtained after densitometric analysis of P2Y1 immunoblots obtained from whole cell lysates of mock-treated wild-type (WT), Cx43 knockout (KO), and antisense 1 (AS1)-treated (3.0 μM for 48 h) spinal cord astrocytes. Note that in Cx43 KO and AS1-treated astrocytes P2Y1 expression levels were decreased by about 55% and 75%, respectively. *P < 0.05 (One-way ANOVA, followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test).

Dye and electrical coupling

Scrape loading (el-Fouly et al., 1987) and dual whole-cell voltage-clamp recording (Spray et al., 1981; see Srinivas et al., 1999) techniques were used as previously described (for details, see De Pina-Benabou et al., 2001) to evaluate changes in the degree of gap junctional communication between cortical astrocytes after AS-ON treatments. Briefly, to evaluate changes in dye coupling, cortical astrocytes plated in 60-mm dishes and grown to confluency were bathed in PBS containing Lucifer Yellow (0.5 mg/ml; Sigma) and three parallel scrapes per dish allowed the dye to enter the damaged cells. At 5 min after scraping, preparations were washed 5–6 times with PBS and then fixed in 4% p-formaldehyde and photographed to determine the extent of LY spread from the scrape to adjacent cells. Junctional conductance was characterized in freshly dissociated pairs of cortical astrocytes; cells were voltage clamped at a holding potential of 0 mV and 8–10-s duration command steps in 20-mV increments from −100 mV to +100 mV were presented to one cell and junctional currents recorded in the unstepped cell, using Pclamp-6 software (Axon Instruments, CA). Patch pipettes were filled with 140 mM CsCl; 10 mM EGTA; 5mM Mg2ATP (pH 7.3). Cells were bathed in solution containing 140 mM NaCl; 2 mM KCl; 2 mM CaCl2;1 mM BaCl2; 2 mM CsCl; 1 mM MgCl2; 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.2).

Connexin43 and P2Y Receptor Expression Levels

Western blot

Whole cell lysates were prepared from cultured Cx43 KO and from AS-ON-treated and untreated WT cortical and spinal cord astrocytes grown in 35-mm dishes. Equal amounts of total protein were electrophoresed on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA), and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Schleider & Schuell, Keene, NH), which were incubated overnight at 4°C with blocking buffer (PBS with 5% nonfat dry milk) and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with primary antibodies (anti-P2Y1 and anti-P2Y4 diluted 1:200, Alomone Laboratories, Jerusalem, Israel; anti-Cx43 18A antibodies diluted 1:2,000, a gift from Dr. E.L. Hertzberg at Albert Einstein College of Medicine; anti-β-actin diluted 1:5,000, Sigma). After several washes, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antirabbit or antimouse IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 h at room temperature. Detection was performed on x-ray film after incubation of the membranes with the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK). Quantification of Cx43 and P2Y protein levels was performed by densitometric analysis using Scion NIH-Image software; at least three independent samples were analyzed.

Pharmacological Behavior of P2Y Receptor Subtypes After Acute Downregulation of Cx43 Expression

Intracellular calcium levels

Changes in cytosolic Ca2+ levels induced by P2Y receptor agonists were measured as previously described (Scemes et al., 2000; De Pina-Benabou et al., 2001) in spinal cord astrocytes loaded with Fura-2-AM (10 μM; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The ratio of Fura-2 fluorescence emitted at two excitation wavelengths (340 and 380 nm) was obtained using a combined system of optical filter wheel (Sutter Instruments, Burlingame, CA) and a shutter (Uniblitz, Rochester, NY) driven by an OEI computer (Universal Imaging). The images were acquired using a cooled CCD camera (Quantex) and analyzed using Metafluor Imaging System software (Universal Imaging). Noncumulative dose-response curves were obtained for two P2 receptor agonists; the EC50 values (effective concentration that induced half-maximal increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels) for the agonists were calculated from the sigmoidal fittings of the dose-response curves using Prism 3.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Crossdesensitization experiments to evaluate possible coexpression of adenine and uridine nucleotide sensitive P2Y receptor subtypes were performed by pre-stimulating the cells with an agonist (e.g., adenine nucleotide) at a maximal effective concentration and then analyzing the Ca2+ responses to application of a second agonist (e.g., uridine nucleotide) in the presence of the first. The P2 receptor agonists employed were UTP (uridine 5′-triphosphate) and 2-MeS-ATP (2-methylthioadenosine 5′-triphosphate).

Intercellular calcium waves

Properties of Ca2+ wave propagation

Calcium waves in Indo-1-AM (Molecular Probes) loaded spinal cord astrocytes were evoked by mechanical stimulation, as previously described (Scemes et al., 1998, 2000). The ratio of Indo-1 fluorescence intensity emitted at two wavelengths (390–440 nm and >440 nm) was imaged using ultraviolet (UV) laser excitation at 351 nm. Ratio images were continuously acquired at 1 Hz after background and shading corrections using a Nikon real time confocal microscope (RCM 8000) with UV large pinhole and Nikon 40x water-immersion objective (NA 1.15; working distance 0.2 mm). The velocity of calcium waves was calculated as the distance (μm) between the stimulated cell and nonstimulated cells divided by the time interval (in seconds) between half-maximal calcium increases within the stimulated and responding cells. Amplitudes of calcium waves were considered to be the maximal increments in intracellular Ca2+ in relation to basal levels observed in responding cells. The efficacy of calcium spread between astrocytes was calculated as the proportion of cells responding with Ca2+ increases in relation to the total number of cells within the confocal field (171 × 128 μm). To describe the overall changes in the properties of calcium waves we used the EVA factor (product of the relative values (test/control) obtained for efficacy, velocity, and amplitude of the waves: Scemes et al., 2000).

RESULTS

It has been reported that P2Y expression levels change during CNS development (Zhu and Kimelberg, 2001) and after denervation or crush of motor nerve (Choi et al., 2001; James and Butt, 2001a). To evaluate whether changes in P2Y receptor pharmacology observed in Cx43 KO astrocytes (Scemes et al., 2000) were related to Cx43 expression or attributable to other factors that might occur during astrocyte development (such as preferred survival of cells expressing one type of P2Y receptor subtype), we have employed an antisense oligonucleotide strategy for acute downregulation of Cx43 expression levels and have evaluated the changes in P2Y receptor function and expression.

Acute Downregulation of Cell Coupling and Cx43 Expression Levels by AS-ONs

All mammalian connexin genes, with the exception of that encoding Cx36, consist of two exons separated by an intron where exon2 contains the entire coding sequence (Fishman et al., 1991; Condorelli et al., 1998; Belluardo et al., 1999; Cicirata et al., 2000). For Cx43, the 5′ untranslated region of the mRNA in exon1 contains a functional internal ribosome entry site (IRES) element (located within the first 164 nucleotides) that seems to be required for efficient translation (Schiavi et al., 1999; Hudder and Werner, 2000).

Based on the known nucleotide sequence of the mouse Cx43 gene (accession no. gi: 192850; 192849), we constructed oligonucleotides antisense to the mRNA corresponding to exon1 (at position 40–59 of the first 5′ UTR nucleotide of exon1) and exon2 (at position 654–663 from the start codon) of Cx43 DNA in order to selectively inhibit expression of Cx43. To establish the optimal conditions that maximally reduced junctional communication, we performed experiments using cortical rather than spinal cord astrocytes because brain astrocytes express higher levels of Cx43 (unpublished observation) and display higher junctional conductance (Scemes et al., 1998, 2000). Evaluation of the effective concentration of AS-ON that reduced cell coupling was performed in confluent cultures of cortical astrocytes exposed for 48 h to 0.7, 3.0, and 6.0 μM of the oligonucleotide antisense to the mRNA corresponding to exon-1 (AS1) of Cx43 DNA and the scrape loading technique employed to measure the degree of dye coupling. After 48-h exposure of astrocytes to AS1, a significant decrease in dye coupling to 0.61 ± 0.038 and 0.76 ± 0.06 from control levels (untreated cultures) was observed in cultures treated with 3.0 and 6.0 μM AS1, respectively (Fig. 1A). [No significant difference (Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test) was observed when comparing Cx43 expression levels obtained from 3.0 and 6.0 μM AS-ON—treated cultures]. Because 3.0 μM AS1 was sufficient to maximally decrease dye coupling, all subsequent experiments were performed using oligonucleotides at that final concentration.

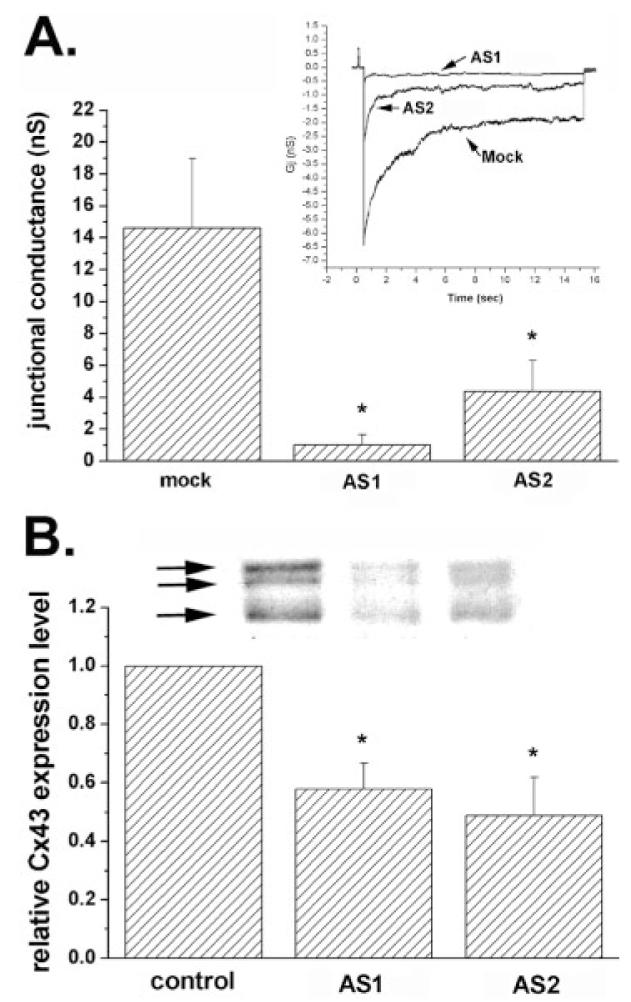

To evaluate the efficiency of the other antisense oligonucleotide (AS2) on cell coupling and to control for the nonspecific effects of AS-ONs, dye coupling assays were employed using cultures exposed for 48 h to 3.0 μM AS2 and two sense oligonucleotides (S1 and S2). The distance of LY spread from the scrape was compared with that obtained for AS1-treated, untreated, and mock-treated astrocyte cultures. When exposed for 48 h to 3.0 μM AS1 and AS2, LY spread decreased to 0.5 ± 0.05 and 0.2 ± 0.1, respectively (Fig. 1B); the reduction in dye transfer obtained for the two AS-ONs was as effective as that observed in cells exposed to 100 μM carbenoxolone (a gap junction channel blocker) (Fig. 1B). No significant change in the degree of dye coupling was observed between cortical astrocytes exposed to the two sense-oligonucleotides (S1, S2; Fig. 1B) when compared with control and mock-treated cultures. The AS-ON induced decrease in dye coupling was paralleled by a significant decrease in electrical coupling; 48 h exposure of cortical astrocyte cultures to 3 μM AS1 and AS2 greatly reduced electrical coupling between cell pairs from 14.5 ± 2 nS to 1.0 ± 0.5 nS and 4.5 ± 1.5 nS, respectively (Fig. 2A); no significant difference (P > 0.05, Tukey’s multiple comparison test) was obtained when comparing the effects of the two AS-ONs on junctional conductance. The decrease in cell coupling observed by treating cortical astrocytes with AS-ONs was accompanied by a 55% decrease in expression levels of all three bands of Cx43 (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Changes in electrical coupling and in Cx43 expression levels induced by antisense oligonucleotides (AS-ONs). A: Histogram showing the mean values of junctional conductance measured from 10–12 pairs of cortical astrocytes derived from cultures that were mock- and AS-ON-treated. Note the dramatic decrease in junctional conductance in cell pairs exposed to the two antisense oligonucleotides (3.0 μM for 48 h). *P < 0.05 (one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA], followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test). Inset: Junctional current responses to transjunctional voltages of 100 mV with abscissa representing the conversion to conductance units; peak responses for mock, AS1-, and AS2-treated cells are 6.5, 0.7, and 2.5 nS, respectively. B: Mean values of the relative changes in Cx43 expression levels after 48 h exposure of confluent cultures of cortical astrocytes to 3.0 μM AS1 and AS2. Cx43 expression levels were normalized against control (untreated cultures: first bar); mean values and standard errors were obtained from three independent experiments; *P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA, followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test). An example of Cx43 immunoblot is shown on the top of the bar histogram; the arrows indicate the phosphorylated (top two arrows) and the nonphosphorylated (bottom arrow) slates of Cx43; quantification was performed comparing total Cx43 expression within each group.

Based on these results indicating that both AS-ONs were similarly effective in reducing Cx43-mediated cell-cell coupling, the experiments aimed to evaluate changes in P2Y receptor function/expression were therefore performed on spinal cord astrocytes exposed for 48 h to 3 μM AS1.

Acute Downregulation of Cx43 Alters the Pharmacological Profile of P2Y Receptors in Spinal Cord Astrocytes

To evaluate the extent to which Cx43 expression levels alter P2Y receptor function, we exposed spinal cord astrocytes for 48 h to 3 μM AS1 and calculated the half-maximal responses (EC50 values) for two agonists (2-MeS-ATP and UTP: selective for the P2Y1 and P2Y2/4 receptors, respectively) by measuring the changes in intracellular calcium levels in Fura-2-AM loaded cells. Parallel experiments were also performed on mock-treated Cx43 KO and WT spinal cord astrocytes obtained from 10 different litters.

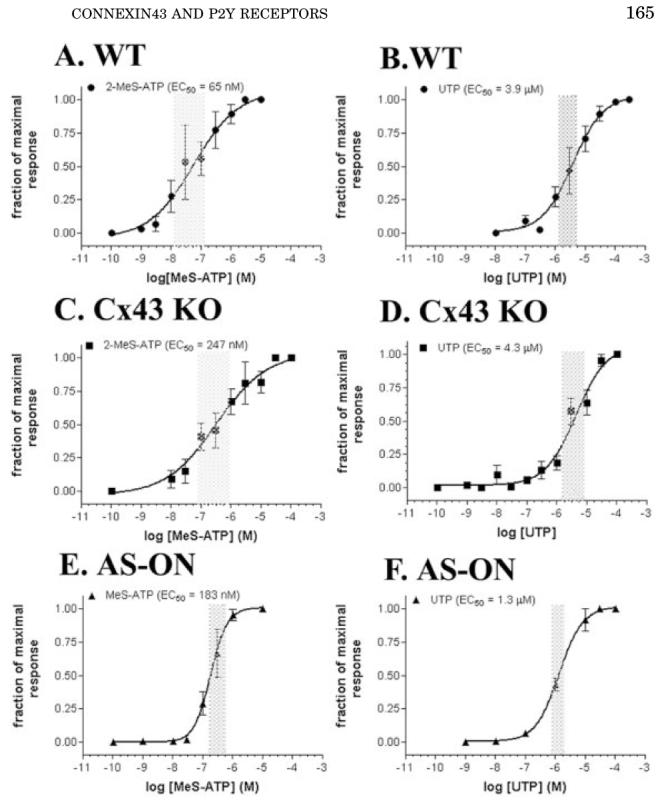

The dose-response curves and respective EC50 values obtained for the P2 agonists are shown in Figure 3. The half-maximal responses obtained for 2-MeS-ATP and UTP in mock-treated WT spinal cord astrocytes were 65 nM and 3.9 μM, respectively (Fig. 3A,B); the difference between these EC50 values with those previously obtained from untreated WT spinal cord astrocytes (280 nM for 2-MeS-ATP and 32.2 μM for UTP: Scemes et al., 2000) is likely due to nonspecific effects on the P2Y receptors of lipofectamine used in mock-treated cells. No significant changes in the EC50 values for UTP were observed in mock-treated Cx43 KO and in AS1-treated WT cells (4.3 μM and 1.3 μM, respectively: Fig. 3D,F) when compared with mock-treated WT astrocytes (3.9 μM: Fig. 3B); however, a significant shift in the EC50 value for 2-MeS-ATP was observed in both mock-treated Cx43 KO and AS1-treated WT spinal cord astrocytes, which in both cases increased by threeto fivefold (247 nM and 183 nM, respectively: Fig. 3C,E). These data indicating that acute downregulation of Cx43 alters the responses of the adenine-sensitive P2Y1 receptor to agonist are in agreement with our previous observation showing a dramatic shift in the EC50 value for 2-MeS-ATP in Cx43 KO spinal cord astrocytes when compared with WT siblings (Scemes et al., 2000).

Fig. 3.

Dose-response curves obtained for 2-MeS-ATP (A,C,E) and UTP (B,D,F) measured in Fura-2-AM-loaded mock-treated wild-type (WT) (A,B) and Cx43 KO (C,D), and anti-sense oligonucleotide (AS-ON)-treated WT (E,F) spinal cord astrocytes. Note that the EC50 values obtained for 2-MeS-ATP are significantly higher in Cx43 knockout (KO) and AS-ON-treated (247 nM and 183 nM, respectively) than in mock-treated WT astrocytes (65 nM). No significant changes in the EC50 values for UTP were observed. Each point in the graphs represents the mean values and standard errors obtained for 10 different litters of WT and Cx43 KO mice and for five independent experiments on AS-treated WT spinal cord astrocytes. The shaded bars on each graph indicate the 95% confidence interval of the EC50 values obtained by nonlinear curve fitting using GraphPad, Prism 3.0 software.

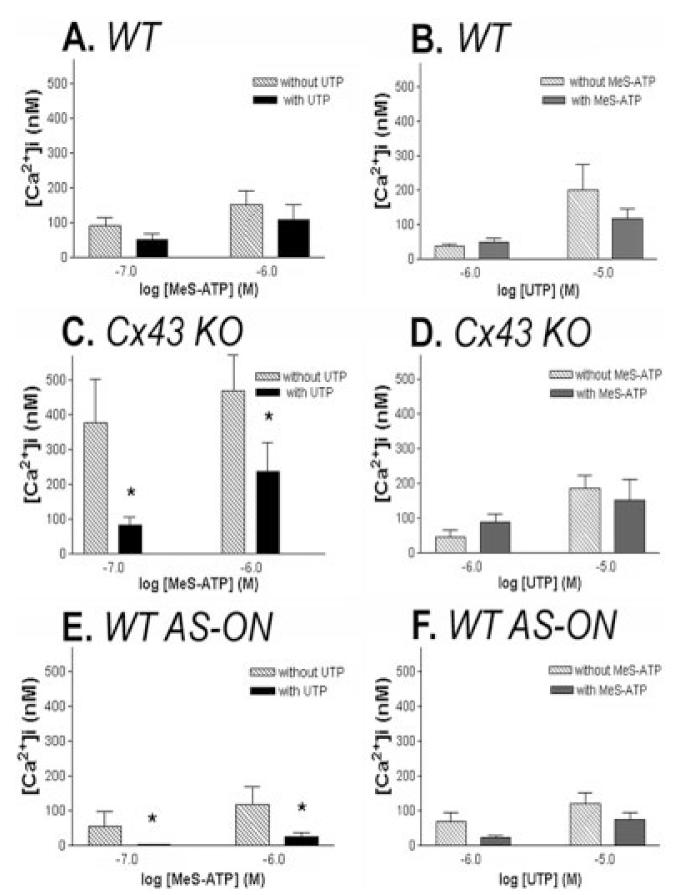

For the desensitization experiments, Fura-2-AM loaded mock-treated WT and Cx43 KO and in AS1-treated WT spinal cord astrocytes were exposed for 5 min to a supra-maximal concentration of UTP (100 μM) to desensitize the uridine-sensitive P2Y2/4 receptor subtypes and intracellular calcium increases measured in response to bath application of two submaximal concentrations (0.1 and 1 μM) of 2-MeS-ATP applied in the continuous presence of UTP; reverse experiments were performed in parallel, i.e., application of two submaximal doses (1 and 10 μM) of UTP after the desensitization of the adenine-sensitive P2Y1 receptor subtype with 100 μM 2-MeS-ATP. When the uridine-sensitive receptor was desensitized by prolonged exposure to 100 μM UTP, bath application of 2-MeS-ATP induced similar cytosolic calcium changes in mock-treated WT as those observed in the absence of UTP (Fig. 4A); no significant changes in intracellular Ca2+ levels in response to UTP were observed in mock-treated WT astrocytes in the presence or absence of 100 μM 2-MeS-ATP (Fig. 4B). These data indicate that WT mouse spinal cord astrocytes express at least two P2Y receptor subtypes, the adenine-sensitive P2Y1 and the uridine-sensitive P2Y2/4 receptor subtypes, as was recently reported for rat astrocytes (Jimenez et al., 2000; Zhu and Kimelberg, 2001). Significantly different responses to 2-MeS-ATP were obtained in mock-treated, Cx43 KO and AS1-treated WT spinal cord astrocytes; in the presence of 100 μM UTP the amplitudes of Ca2+ transients elicited by 2-MeS-ATP were greatly attenuated when compared with the responses obtained in the absence of UTP (cf. Fig. 4C and 4E), indicating that in these cases, a P2 receptor other than the P2Y1 subtype responding to 2-MeS-ATP is functionally expressed. [2-MeS-ATP has been shown to be a partial agonist of the rodent P2Y4 receptor (Bogdanov et al., 1998); furthermore, the participation of a P2X receptor is also likely given that the larger amplitudes of Ca2+ responses to 2-MeS-ATP obtained in Cx43 KO astrocytes (Fig. 4C) were greatly attenuated when the cells were bathed in a Ca2+-free solution (data not shown)]. No significant changes in cytosolic Ca2+ transients in response to UTP were observed in mock-treated Cx43 KO and in AS1-treated WT astrocytes when in the presence or absence of 2-MeS-ATP (Fig. 4D,F).

Fig. 4.

Changes in functional expression of the adenine-sensitive P2Y1 receptor subtype by downregulation of Cx43 expression levels. Changes in intracellular Ca2+ levels measured in wild-type (WT) (A,B), Cx43 KO (C,D), and antisense oligonucleotide (AS-ON)-treated (E,F) spinal cord astrocytes induced by 0.1 and 1.0 μM 2 MeS-ATP (A,C,E) in the absence (dashed bars) and presence (black bars) of 100 μM UTP to desensitize the uridine-sensitive P2Y2/4 receptors and by 1.0 and 10 μM UTP (B,D,F) in the absence (dashed bars) and presence (black bars) of 100 μM 2-MeS-ATP to desensitize the adenine-sensitive P2Y1 receptors. Note that the amplitudes of Ca2+ responses to 2-MeS-ATP were greatly attenuated in Cx43 KO and AS-ON-treated cells that were pre-incubated with UTP and that no significant changes in Ca2+ amplitudes induced by UTP were measured in these cells when pre-treated with 2-MeS-ATP. Bar histograms represent the mean values and standard errors of three to six independent experiments. *P < 0.001 (one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA], followed by Tukey test).

These results thus strongly indicate that the population of adenine-sensitive P2Y1 receptor subtype, in relation to the uridine-sensitive P2Y2/4, is decreased in Cx43 KO and AS1-treated WT spinal cord astrocytes, and support our previous observation indicating a switch from a P2Y1- to a P2Y2/4-like receptor when Cx43 is downregulated (Scemes et al., 2000).

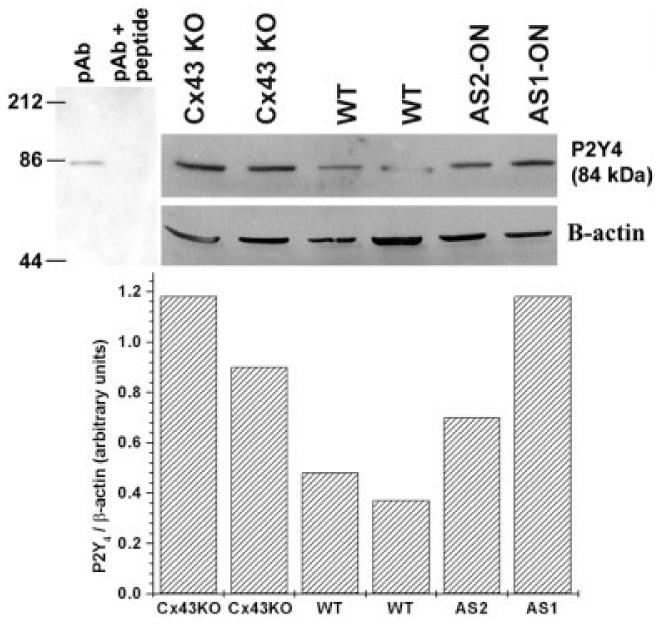

P2Y Receptor Expression Levels Are Altered When Cx43 Is Downregulated

To evaluate whether the changes in P2Y receptor function observed to occur when Cx43 is downregulated was related to altered expression levels of the adenine- and uridine-sensitive P2Y receptor subtypes, we performed Western blot analyses on WT, Cx43 KO, and WT treated with AS-ONs. As was observed in cortical astrocytes (Fig. 2), Cx43 expresssion levels in AS1-ON-treated spinal cord astrocytes decreased in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 5A), being maximally reduced to 0.45 ± 0.12 at 48 h after treatment with 3.0 μM AS1. For the P2Y receptor experiments, we used commercially available polyclonal antibodies to P2Y1 and P2Y4 receptors. The P2Y1 receptor antibody has been shown by the manufacturer to detect a single band near 66 kDa in rat brain membranes and a single band of ∼100 kDa in human platelets, whereas the P2Y4 antibody detects a 85-kDa band (information provided by Alomone Laboratories). Although the apparent molecular weights of these bands are much higher than the 42 kDa predicted from the amino acid sequence (Ayyanathan et al., 1996), it has been reported that posttranslational modifications such as glycosylation and phosphorylation as well as homo- and hetero-oligomerization affect the migration pattern of P2 receptors in SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) with bands detected ≤250 kDa (Torres et al., 1998; Moore et al., 2000; Rettinger et al., 2000; Yoshioka et al., 2002). Western blotting of cultured spinal cord astrocyte whole cell lysates with P2Y1 and P2Y4 antibodies produced single bands at 200 and 84 kDa, respectively, which were abolished by pre-absorption of P2Y antibodies with an equal amount of the respective antigenic peptides (Figs. 5B and 6). Experiments with P2Y2 antibodies demonstrated multiple bands that were not completely abolished by preabsorption with immunogenic peptide and that displayed no detectable difference between WT and Cx43 KO astrocytes.

Fig. 6.

Increased expression levels of P2Y4 receptors in spinal cord astrocytes after downregulation of Cx43. Upper portion (left) shows immunoblot demonstrating that preabsortion of P2Y4 antibody (pAb) with immunogenic peptide abolishes the 84-kDa band. Bar histogram below represents the relative densitometric values (in arbitrary units) obtained from Scion-NIH Image software for the immunoblot performed using P2Y4 and β-actin antibodies (see example at left side of inset). Note the increased expression of P2Y4 receptor in whole cell lysates from Cx43 KO and antisense 1 (AS1)-, AS2-oligonucleotide (ON)-treated cells when compared with wild-type (WT) astrocytes. Cell cultures were obtained from two different litters. Anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (Sigma) was diluted 1:5,000 and the anti-P2Y4 polyclonal antibody (Alomone) diluted 1:200.

Densitometric analysis of P2Y1 immunoblots of whole cell homogenates derived from Cx43 KO and AS1-ON-treated (3.0 μM for 48 h) spinal cord astrocytes indicated that P2Y1 expression levels were reduced to 46% and 23% of control (mock-treated WT cells), respectively (Fig. 5B, histogram below blots). The reduction in P2Y1 expression level, however, was not proportional to the levels of Cx43 expression obtained in AS-ON-treated cultures and in Cx43 KO astrocytes (Fig. 5B). These results may indicate either that although there is a direct relationship between the expression levels of these two proteins they are not proportional and/or that other pathways partially compensate for the reduction of the metabotropic receptor, leading to partial recovery of P2Y1 in Cx43 KO.

Figure 6 shows a Western blot obtained from whole cell lysates of cultured spinal cord astrocytes derived from two independent litters of WT and Cx43 KO mice. Note that P2Y4 expression levels are greatly increased when Cx43 is downregulated (KO, AS1-, and AS2-ON) when compared with WT astrocytes.

These data show that there is a reciprocal change in P2Y1 and P2Y4 expression levels in spinal cord astrocytes when Cx43 is downregulated, such that the decreased expression of adenine-sensitive P2Y1 is accompanied by an increase in the uridine-sensitive P2Y4 receptor. It is therefore likely that the altered pharmacological profile of purinoceptors, observed in astrocytes after acute downregulation of Cx43 (Figs. 3 and 4) is related to the changes in the expression levels of these P2Y receptor subtypes.

Intercellular Calcium Wave Propagation: Interplay Between Gap Junctions and P2Y Receptors

We have previously shown that calcium wave propagation between WT spinal cord astrocytes is supported mainly by a gap junction-dependent mechanism, whereas waves spreading through Cx43 KO spinal cord astrocytes are supported by the extracellular component involving diffusion of an agent acting on P2 receptors. Furthermore, we proposed that such change in the relative contribution of these two pathways was related to the switch in P2Y pharmacology that occurred when Cx43 was deleted by homologous recombination (Scemes et al., 2000).

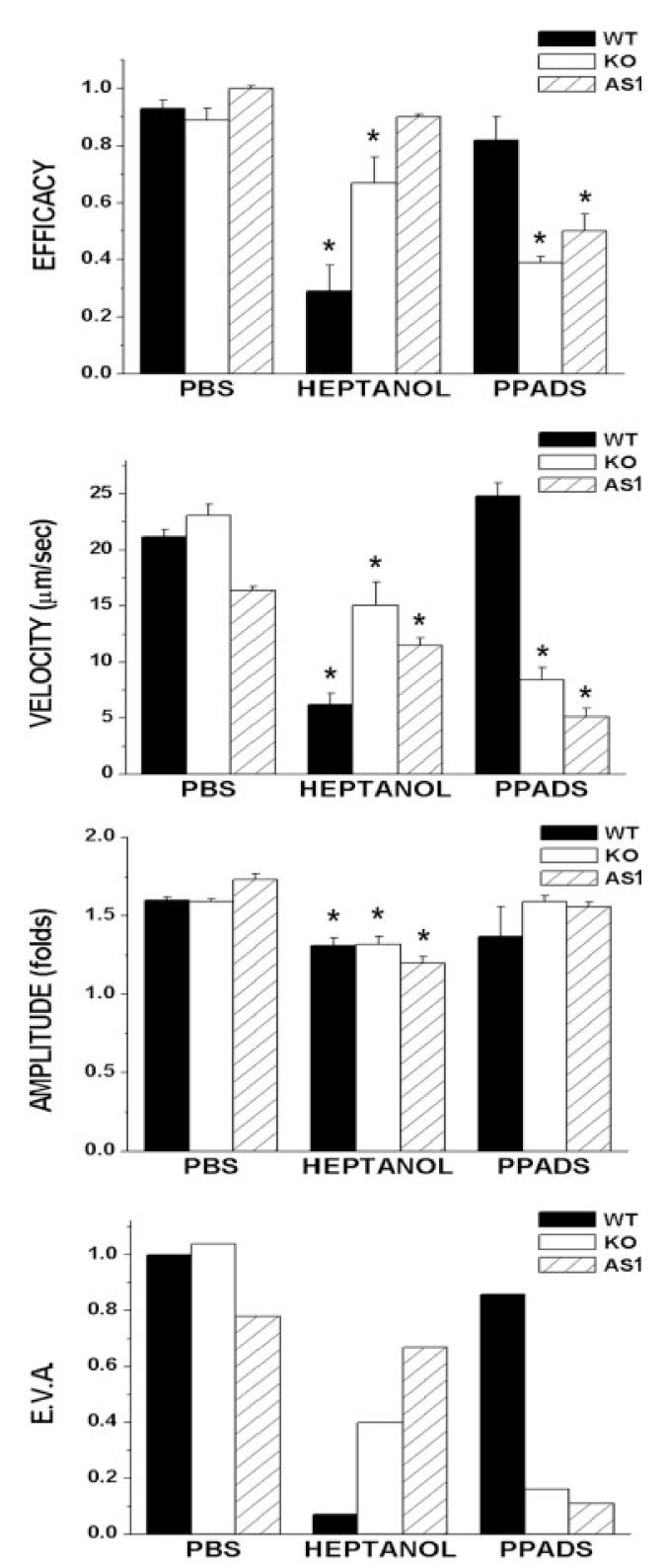

To evaluate further the interplay between Cx43 and P2Y receptors on intercellular Ca2+ signaling, we analyzed the properties of calcium wave propagation in AS1-ON-treated spinal cord astrocytes, in the presence and absence of a gap junction channel blocker (heptanol) and of a P2 receptor antagonist (PPADS) and compared these properties with those obtained from Cx43 KO and WT cells. When bathed in PBS, mechanically induced calcium waves spread between AS1-ON-treated spinal cord astrocytes with efficacy, velocity and amplitude similar to those spreading between WT and Cx43 KO cells (Fig. 7). Although 3 mM heptanol reduced the efficacy, velocity and amplitude of calcium wave propagation between AS-1-treated astrocytes (Fig. 7), the reduction induced by the gap junction channel blocker was more severe in WT that in either AS1-treated or Cx43 KO cells (for WT, EVA factor of 0.07 as compared with EVA factor of 0.4 and 0.67 for Cx43 KO- and AS-1-treated astrocytes, respectively; Fig. 7). By contrast, in the presence of PPADS (100 μM), Ca2+ wave-spread between AS1-ON-treated cells was greatly attenuated (EVA factor of 0.11), while in WT cells this P2 antagonist caused only a minor effect (EVA factor of 0.86; Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Properties of intercellular calcium waves propagating between wild-type (WT) (black bars), Cx43 knockout (KO) (white bars), and antisense 1 (AS1)-treated (dashed bars) spinal cord astrocytes when bathed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 3 mM heptanol, and 100 μM of the P2 receptor antagonist PPADS. The bar histograms represent the mean values and standard errors of independent experiments obtained for the efficacy, velocity, and amplitude (EVA) of calcium wave spread (from top to bottom); the overall property of calcium waves, measured by the EVA factor is also displayed. Note that for both Cx43 KO and WT AS1-treated spinal cord cultures, the P2 antagonist (PPADS) was more effective than the gap junction channel blocker, heptanol, in reducing intercellular Ca2+ signaling, while for WT cells, heptanol was more effective than PPADS in reducing wave spread. *P < 0.05 (one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA], followed by Tukey).

These data thus indicate that in WT spinal cord astrocytes gap junction-dependent and -independent mechanisms contribute about 85% and 15%, respectively, to the overall property of calcium wave propagation and that the relative contribution of the extracellular pathway is increased to 90% when Cx43 is acutely downregulated, as was observed for Cx43 KO spinal cord astrocytes (Scemes et al., 2000) (Fig. 7). Such increased contribution of the extracellular component of intercellular calcium signaling in AS-ON-treated cells, a condition shown in the present study to cause a decrease in P2Y1 receptor expression levels, is likely to be related to increased expression levels of the P2Y4 receptor, which is equally sensitive to ATP and UTP in mouse (Suarez-Huerta et al., 2001; Marcus and Scofield, 2001). Thus, for calcium wave propagation, the increased expression of P2Y4 receptor subtype that parallels the decrease in ATP sensitive P2Y1 receptor subtype expression levels when Cx43 is downregulated would provide the necessary machinery for the cells to respond to both ATP and UTP released from the mechanically stimulated cell (the release of ATP and UTP from mechanically stimulated cells has been directly demonstrated by Lazarowski et al., 1997).

DISCUSSION

Several lines of evidence have recently provided support for the notion that glial cells, specifically astrocytes, are not only able to detect and respond to neuronal activity but can also have an active role in CNS function, controlling neuronal excitability (Bacci et al., 1999; Parpura et al., 1994; Kang et al., 1998). Although many ions and small molecules may ultimately be involved in relaying intracellular signals, spatial and temporal alterations in intracellular Ca2+ levels in the form of Ca2+ spikes, oscillations, and waves are major events in astrocyte-neuronal communication (Newman and Zahs, 1997, 1998; Araque et al., 1998a,b, 1999; Hassinger et al., 1996; Bezzi et al., 1998; Parpura and Haydon, 2000).

Calcium signals can be propagated from one astrocyte to another by the diffusion of signaling molecules through intercellular gap junction channels and/or through the extracellular space, involving the release of substances acting on plasmalemmal membrane P2 receptors (for review, see Giaume and Venance, 1998; Scemes, 2000). The relative contribution of these two pathways for intercellular Ca2+ wave propagation may vary in different CNS regions depending on the strength of gap junction-mediated coupling (Scemes et al., 2000; Blomstrand et al., 1999; Batter et al., 1992; Lee et al., 1994) and on the subtypes of P2 receptors responding to purine and pyrimidine nucleotides (Scemes et al., 2000; Pearce and Langley, 1994; Ho et al., 1995; King et al., 1996; Jimenez et al., 2000; Lenz et al., 2000). Furthermore, under certain pathological conditions the mode of calcium wave propagation between astrocytes can switch from a gap junction-dependent to a gap junction-independent mechanism due to downregulation of the gap junction protein Cx43 and upregulation of P2Y2 receptor mRNA, as seen in interleukin-1β-treated human astrocytes (John et al., 1999). For Cx43 KO spinal cord astrocytes, the change in mode by which intercellular calcium waves propagate was shown to be related to a switch in P2Y pharmacological profile from an adenine-sensitive P2Y1 to an uridine-sensitive P2Y2/4 receptor observed to occur in Cx43 KO astrocytes (Scemes et al., 2000).

Astrocytes express a multitude of P2Y receptor subtypes (P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, and P2Y6: Jimenez et al., 2000; James and Butt, 2001b), each with a different sensitivity to P2 agonists and antagonists. For instance, ADP, 2-MeS-ADP, and 2-MeS-ATP are strong agonists of P2Y1 receptors (EC50 at the nM range), but not at P2Y2 and P2Y4 receptors (for review, see Kugelgen and Wetter, 2000; King et al., 1998). Although UTP and ATP are equally potent agonists (EC50 in the μM range) of the rodent P2Y2 and P2Y4 receptors (Suarez-Huerta et al., 2001), these two P2Y receptor subtypes can be distinguished based on their response to two P2 antagonists: suramin and PPADS. P2Y2 receptors are suramin sensitive, while PPADS, but not suramin, has been shown to block the mouse P2Y4 receptor (Charlton et al., 1996a,b; King et al., 1998; Suarez-Huerta et al., 2001).

It is possible that the expression of a multitude of P2Y receptor subtypes displaying such a broad spectrum of sensitivities to adenine and uridine nucleotides would provide the sufficient machinery to sustain longrange Ca2+ signaling when gap junctional communication is reduced or absent. In this regard, we have shown that intercellular calcium waves between Cx43 KO spinal cord astrocytes spread with the same efficiency as in WT littermates; interestingly, however, these Cx43 KO cells displayed P2Y receptors with altered pharmacological profiles in response to agonists and antagonists indicating that the adenine-sensitive P2Y1 receptor subtype was absent in the Cx43 KO cells (Scemes et al., 2000). Because our previous work was solely based on functional studies, we extended our studies to evaluate the nature of such changes by analyzing the function and expression levels of P2Y receptors when Cx43 is acutely downregulated. Using Cx43 antisense oligonucleotides, the present study shows that acute downregulation of Cx43 expression levels leads, as observed for Cx43 KO spinal cord astrocytes, to alteration in pharmacological profile of P2Y receptors expressed in cultured spinal cord astrocytes, from an adenine-sensitive P2Y1 to an uridine-sensitive P2Y2/4-like receptor and to a switch in mode by which intercellular calcium waves propagate, from a gap junction-dependent to a gap junction-independent mechanism. Furthermore, it is demonstrated that such changes in P2Y receptor behavior are accompanied by a change in the expression levels of two purinoceptor subtypes such that downregulation of Cx43 leads to decreased expression levels of the P2Y1 receptor and to increased expression of the P2Y4 receptor.

In agreement with our previous studies, the data presented in the present work provide the molecular identity of the P2Y receptor subtypes that are altered when Cx43 is downregulated and lead us propose that such compensatory mechanism for intercellular Ca2+ signaling would depend on a finely tuned interaction between gap junctions and P2Y receptors, such that Cx43 would regulate both modes of intercellular calcium signaling. The mechanism involved in the interplay between Cx43 and P2Y receptors remains unknown. Some recent reports have suggested that the function of Cx43 in calcium wave transmission is to provide the route (hemichannels) by which ATP is released from the cells to activate purinoceptors expressed in neighboring ones (Arcuino et al., 2002; Stout et al., 2002). However, our present and previous work (Scemes et al., 2000) on spinal cord astrocytes lacking Cx43 showing an enhanced contribution of the extracellular route for Ca2+ signal transmission do not support the hypothesis that Ca2+ signaling is sustained by the release of ATP through Cx43 hemichannels. Instead, we propose that remodeling of junctional complexes after the loss of Cx43 gap junction channels leads to altered expression of P2Y receptors, as has been reported to occur for protein components of adhesive junctions, desmosomes and tight junctions (Matsushita et al., 1999; Ai et al., 2000; Duffy et al., 2000).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants NS-41023 (to E.S.) and NS-41282 (to D.C.S).

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Grant numbers: NS-41023 NS-41282.

REFERENCES

- Ai Z, Fischer A, Spray DC, Brown AMC, Fishman GI. Wnt-1 regulation of connexin43 in cardiac myocytes. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:161–171. doi: 10.1172/JCI7798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A, Sanzgiri RP, Parpura V, Haydon PG. Calcium elevation in astrocytes causes an NMDA receptor-dependent increase in the frequency of miniature synaptic currents in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1998a;18:6822–6829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06822.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A, Parpura V, Sanzgiri RP, Haydon PG. Glutamate-dependent astrocyte modulation of synaptic transmission between cultured hippocampal neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1998b;10:2129–2142. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A, Parpura V, Sanzgiri RP, Haydon PG. Tripartite synapses: glia, the unacknowledged partner. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:208–213. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcuino G, Lin JH, Takano T, Liu C, Jiang L, Gao Q, Kang J, Nedergaard M. Intercellular calcium signaling mediated by point-source burst release of ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9840–9845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152588599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyanathan K, Webb TE, Sandhu AK, Athwal RS, Barnard EA, Kunapuli SP. Cloning and chromosomal localization of the human P2Y1 purinoceptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;218:783–788. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacci A, Verderio C, Pravetonni E, Mateoli M. The role of glial cells in synaptic function. Philos Trans R Soc Lond. 1999;354:403–409. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batter DK, Corpina RA, Roy C, Spray DC, Hertzberg EL, Kessler JA. Heterogeneity in gap junction expression in astrocytes cultured from different brain regions. Glia. 1992;6:213–221. doi: 10.1002/glia.440060309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beblo DA, Veenstra RD. Monovalent cation permeation through the connexin40 gap junction channel, Cs+, Rb+, K+, Li+, TEA, TMA, TBA, and effects of anions Br-,Cl-, F-, acetate, aspartate, glutamate, and NO3- J Gen Physiol. 1997;109:509–522. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.4.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beblo DA, Wang HZ, Beyer EC, Westphale EM, Veenstra RD. Unique conductance, gating, selective permeability properties of gap junction channels formed by connexin40. Circ Res. 1995;77:813–822. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.4.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belluardo N, Trovato-Salinaro A, Mudo G, Hurd YL, Condorelli DF. Structure, chromosomal localization, and brain expression of human Cx36 gene. J Neurosci Res. 1999;57:740–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezzi P, Carmignoto G, Pasti L, Vesce S, Rossi D, Rizzini BL, Pozzan T, Volterra A. Prostaglandins stimulate calcium-dependent glutamate release in astrocytes. Nature. 1998;391:281–285. doi: 10.1038/34651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomstrand E, Aberg ND, Eriksson PS, Hansson E, Ronnback L. Extent of intercellular calcium wave propagation is related to gap junction permeability and level of connexin43 expression in astrocytes in primary cultures from four brain regions. Neuroscience. 1999;92:255–265. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00738-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov YD, Wildman SS, Clements MP, King BF, Burnstock G. Molecular cloning and characterization of rat P2Y4 nucleotide receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;1247:428–430. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner G, Murphy S. ATP-evoked arachnoid acid mobilization in astrocytes via P2Y purinergic receptor. J Neurochem. 1990;55:1569–1575. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton SJ, Brown CA, Weisman GA, Turner JT, Erb L, Boarder MR. PPADS and suramin as antagonists of cloned P2Y- and P2U-purinoceptors. Br J Pharmacol. 1996a;118:704–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15457.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton SJ, Brown CA, Weisman GA, Turner JT, Erb L, Boarder MR. Cloned and transfected P2Y4 receptors: characterization of a suramin and PPADS-insensitive response to UTP. Br J Pharmacol. 1996b;119:1301–1303. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi RCY, Man MLS, Ling KKY, Ip NY, Simon J, Barnard EA, Tsim KWK. Expression of the P2Y1 nucleotide receptor in chick muscle: its functional role in the regulation of acetylcholinesterase and acetylcholine receptor. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9224–9234. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09224.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ GJ, Moreno AP, Melman A, Spray DC. Gap junction-mediated intercellular diffusion of Ca2+ in cultured human corporal smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:C373–C383. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.263.2.C373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill G, Louis C. Roles of Ca2+, inositol trisphosphate, and cyclic ADP-ribose in mediating intercellular Ca2+ signaling in sheep lens cells. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:1217–1223. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.9.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli R, Di Iorio P, Ballerini P, Ambrosio G, Giuliani P, Tiboni GM, Caciaglia F. Effects of exogenous ATP and related analogs on the proliferation rate of dissociated primary cultures of rat astrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 1994;39:556–566. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490390507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicirata F, Parenti R, Spinella F, Giglio S, Tuorto F, Zuffardi O, Gulisano M. Genomic organization and chromosomal localization of the mouse connexin36 (mCx36) gene. Gene. 2000;251:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condorelli DF, Parenti R, Spinella F, Trovato-Salinaro A, Belluardo N, Cardile V, Cicirata F. Cloning a new gap junction gene (Cx36) highly expressed in mammalian brain neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:1202–1208. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pina-Benabou MH, Srinivas M, Spray DC, Scemes E. Calmodulin kinase pathway mediates the K+-induced increase in gap junctional communication between mouse spinal cord astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6635–6643. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06635.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermietzel R. Molecular diversity and plasticity of gap junctions in the nervous system. In: Spray DC, Dermietzel R, editors. Gap junctions in the nervous system. RG Landes; Austin, TX: 1996. pp. 13–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dermietzel R, Gao Y, Scemes E, Vieira D, Urban M, Kremer M, Bennett MVL, Spray DC. Connexin43 null [Cx43(-/-)] mice reveal that astrocytes express multiple connexins. Brain Res Rev. 2000;32:45–56. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy HS, John GR, Lee SC, Brosnan C, Spray DC. Reciprocal regulation of the junctional proteins claudin-1 and connexin43 by interleukin-1β in primary human fetal astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2000;RC114(1–6) doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-j0004.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Fouly MH, Trosko JE, Chang CC. Scrape-loading and dye transfer: a rapid and simple technique to study gap junctional intercellular communication. Exp Cell Res. 1987;168:422–430. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(87)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman GI, Eddy RL, Shows TB, Rosenthal L, Leinwand LA. The human connexin gene family of gap junction proteins: distinct chromosomal locations but similar structures. Genomic. 1991;10:250–256. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90507-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaume C, Venance L. Intercellular calcium signaling and gap junctional communication in astrocytes. Glia. 1998;24:50–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie PB, Knappenherger J, Segal M, Bennett MVL, Charles AC, Kater SB. ATP released from astrocytes mediates glial calcium waves. J Neurosci. 1999;19:520–528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00520.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassinger TD, Guthrie PB, Atkinson PB, Bennett MV, Kater SB. An extracellular component in propagations of astrocytic calcium waves. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13268–13273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassinger TD, Atkinson PB, Streker GI, Whalen IR, Dudek FE, Koseel AH, Kater SB. Evidence for glutamate-mediated activation of hippocampal neurons by glial calcium waves. J Neurobiol. 1996;28:159–170. doi: 10.1002/neu.480280204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C, Hicks J, Salter MW. A novel P2-purinoceptor expressed by a subpopulation of astrocytes from dorsal spinal cord of the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;116:2909–2918. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15944.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudder A, Werner R. Analysis of a Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease mutation reveals an essential internal ribosome entry site element in the connexin32 gene. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34586–34591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005199200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idestrup CP, Salter MW. P2Y and P2U receptors differentially release intracellular Ca2+ via phospholipase C/inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate pathway in astrocytes from dorsal spinal cord. Neuroscience. 1998;86:913–923. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James G, Butt AM. Changes in P2Y and P2X purinoceptors in reactive glia following axonal degeneration in rat optic nerve. J Neurosci Lett. 2001a;312:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James G, Butt AM. P2X and P2Y purinoceptors mediate ATP-evoked calcium signaling in optic nerve glia in situ. Cell Calcium. 2001b;30:251–259. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2001.0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez AI, Castro E, Communi D, Boeynaems JM, Delicado EG, Miras-Portugal MT. Coexpression of several types of metabotropic nucleotide receptors in single cerebellar astrocytes. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2071–2079. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John GR, Scemes E, Suadicani SO, Liu JS, Charles PC, Lee SC, Spray DC, Brosnan CF. Interleukin-1β differentially regulates calcium wave propagation between primary human fetal astrocytes via pathways involving P2 receptors and gap junction channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;98:11613–11618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Jiang L, Goldman AS, Nedergaard M. Astrocyte-mediated potentiation of inhibitory synaptic transmission. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:683–692. doi: 10.1038/3684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BF, Neary JT, Zhu Q, Wang S, Norenberg MD, Burnstock G. P2 purinoceptors in rat cortical astrocytes: expression, calcium imaging, and signaling studies. Neuroscience. 1996;74:1187–1196. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BF, Townsend-Nicholson A, Burnstock G. Metabotropic receptor for ATP and UTP: exploring the correspondence between native and recombinant nucleotide receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:506–514. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugelgen I, Wetter A. Molecular pharmacology of P2Y-receptors. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg Arch Pharmacol. 2000;362:310–323. doi: 10.1007/s002100000310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann P, Schroder W, Traub O, Steinhauser C, Dermietzel R, Willecke K. Late onset and increasing expression of the gap junction protein connexin30 to adult murine brains and long-term cultured astrocytes. Glia. 1999;25:111–119. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(19990115)25:2<111::aid-glia2>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarowski ER, Homolya L, Boucher RC, Harden TK. Direct demonstration of mechanically induced release of cellular UTP and its implication for uridine nucleotide receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24348–24354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Kim WY, Cornell-Bell AH, Sontheimer H. Astrocytes exhibits regional specificity in gap junction coupling. Glia. 1994;11:315–325. doi: 10.1002/glia.440110404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz G, Gottfried C, Luo Z, Avruch J, Rodnight R, Nie WJ, Kang Y, Neary JT. P2Y purinoceptor subtypes recruit different Mek activators in astrocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:927–936. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus DC, Scofield MA. Apical P2Y4 purinergic receptor control K+ secretion by vestibular dark cell epithelium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C282–289. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.1.C282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita T, Oyamada M, Fujimoto K, Yasuda Y, Masuda S, Wada Y, Oka T, Takamatsu T. Remodeling of cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions at the border zone of rat myocar-dial infarcts. Circ Res. 1999;85:1046–1055. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.11.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore D, Chamber J, Waldvogel H, Faull R, Emson P. Regional and cellular distribution of the P2Y1 purinergic receptor in the human brain: striking neuronal localization. J Comp Neurol. 2000;421:374–384. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000605)421:3<374::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy JI, Li X, Rempel J, Stelmack G, Patel D, Staines WA, Yasumura T, Rash JE. Connexin26 in adult rodent central nervous system: Demonstration at astrocytic gap junctions and colocalization with connexin30 and connexin43. J Comp Neurol. 2001;441:302–323. doi: 10.1002/cne.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary JT, Van Breemen C, Forster E, Norenberg MD. ATP stimulates calcium influx in primary astrocyte cultures. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;157:1410–1416. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary JT, Laskey R, Van Breemen C, Blicharska J, Norenberg LOB, Norenberg MD. ATP-evoked calcium signal stimulates protein phosphorylation in astrocytes. Brain Res. 1991;566:89–94. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91684-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman EA, Zahs KR. Calcium waves in retinal glial cells. Science. 1997;278:844–847. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5301.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman EA, Zahs KR. Modulation of neuronal activity by glial cells in the retina. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4022–4028. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-11-04022.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osipchuk Y, Cahalan M. Cell-to-cell spread of calcium signals mediated by ATP in mast cells. Nature. 1992;359:241–244. doi: 10.1038/359241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parpura V, Haydon PG. Physiological astrocytic calcium levels stimulate glutamate release to modulate adjacent neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8629–8634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parpura V, Basarsky TA, Liu F, Jeftinija S, Haydon PG. Glutamate-mediated astrocyte-neuron signaling. Nature. 1994;369:744–747. doi: 10.1038/369744a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce B, Langley D. Purine- and pyrimidine-stimulated phosphoinositide breakdown and intracellular calcium mobilization in astrocytes. Brain Res. 1992;660:329–332. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91307-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce B, Langley D. Purine- and pyrimidine-stimulated phosphoinositide breakdown and intracellular calcium mobilization in astrocytes. Brain Res. 1994;660:329–332. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91307-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce B, Murphy S, Jeremy J, Morrow C, Dandona P. ATP-evoked Ca2+ mobilization and protanoid release from astrocytes: P2-purinergica linked to phosphoinositide hydrolysis. J Neurochem. 1989;52:971–977. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb02549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettinger J, Aschrafi A, Schmalzing G. Roles of individual N-glycans for ATP potency and expression of rat P2X1 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33542–33547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002918200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez JC, Connor JA, Spray DC, Bennett MVL. Hepatocyte gap junctions are permeable to the second messenger, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and to calcium ions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2708–2712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter MW, Hicks JL. ATP causes release of intracellular Ca2+ via the phospholipase C beta/IP3 , pathway in astrocytes from the dorsal spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2961–2971. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02961.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scemes E. Components of astrocytic intercellular calcium signaling. Mol Neurobiol. 2000;22:167–179. doi: 10.1385/MN:22:1-3:167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scemes E, Spray DC. Increased intercellular communication in mouse astrocytes exposed to hyposmotic shocks. Glia. 1998;24:74–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scemes E, Dermietzel R, Spray DC. Calcium waves between astrocytes from Cx43 knockout mice. Glia. 1998;24:65–73. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199809)24:1<65::aid-glia7>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scemes E, Suadicani SO, Spray DC. Intercellular communication in spinal cord astrocytes: Fine tuning between gap junctions and P2 nucleotide receptors in calcium wave propagation. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1435–1445. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01435.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiavi A, Hudder A, Werner R. Connexi43 mRNA contains a functional internal ribosome entry site. FEBS Lett. 1999;464:118–122. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01699-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y, McCarthy KD. Regulation of astroglial responsiveness to neuroligands in primary culture. Neuroscience. 1993;55:991–1001. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spray DC. Physiological properties of gap junction channels. In: Spray DC, Dermietzel R, editors. Gap junctions in the nervous system. RG Landes; Austin, TX: 1996. pp. 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Spray DC, Harris AI, Bennett MV. Equilibrium properties of a voltage-dependent junctional conductance. J Gen Physiol. 1981;77:77–93. doi: 10.1085/jgp.77.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spray DC, Vink MJ, Scemes E, Suadicani SO, Fishman GI, Dermietzel R. Characteristics of coupling in cardiac myocytes and CNS astrocytes cultured from wild-type and Cx43-null mice. In: Werner R, editor. Gap junctions. IOS; The Netherlands: 1998. pp. 281–285. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas M, Costa M, Gao Y, Fort A, Fishman GI, Spray DC. Voltage dependence of macroscopic and unitary currents of gap junction channels formed by mouse connexin50 expressed in rat neuroblastoma cells. J Physiol Lond. 1999;517:673–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0673s.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Huerta N, Pouillon V, Boeynaems JM, Robaye B. Molecular cloning and characterization of the mouse P2Y4 nucleotide receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;416:197–202. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00875-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres GE, Egan TM, Voigt MM. N-linked glycosylation is essential for the functional expression of the recombinant P2X2 receptor. Biochemistry. 1998;37:14845–14851. doi: 10.1021/bi981209g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra RD, Wang HZ, Beyer EC, Brink PR. Selective dye and ionic permeability of gap junction channels formed by connexin45. Circ Res. 1994;75:483–490. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HZ, Veenstra RD. Monovalent ion selectivity sequences of the rat connexin43 gap junction channel. J Gen Physiol. 1997;109:491–507. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.4.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JM, Sun GY. Effects of IL-1β on receptor mediated polyphosphoinositide signaling pathway in immortalized astrocytes (DITNC) Neurochemistry Res. 1997;22:1309–1315. doi: 10.1023/a:1021949417127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka K, Saitoh O, Nakata H. Agonist-promoted heteromeric oligomerization between adenosine A1 and P2Y1 receptors in living cells. FEBS Lett. 2002;523:147–151. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02965-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Kimelberg HK. Developmental expression of metabo-tropic P2Y1 and P2Y2 receptors in freshly isolated astrocytes from rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2001;77:530–541. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]