Abstract

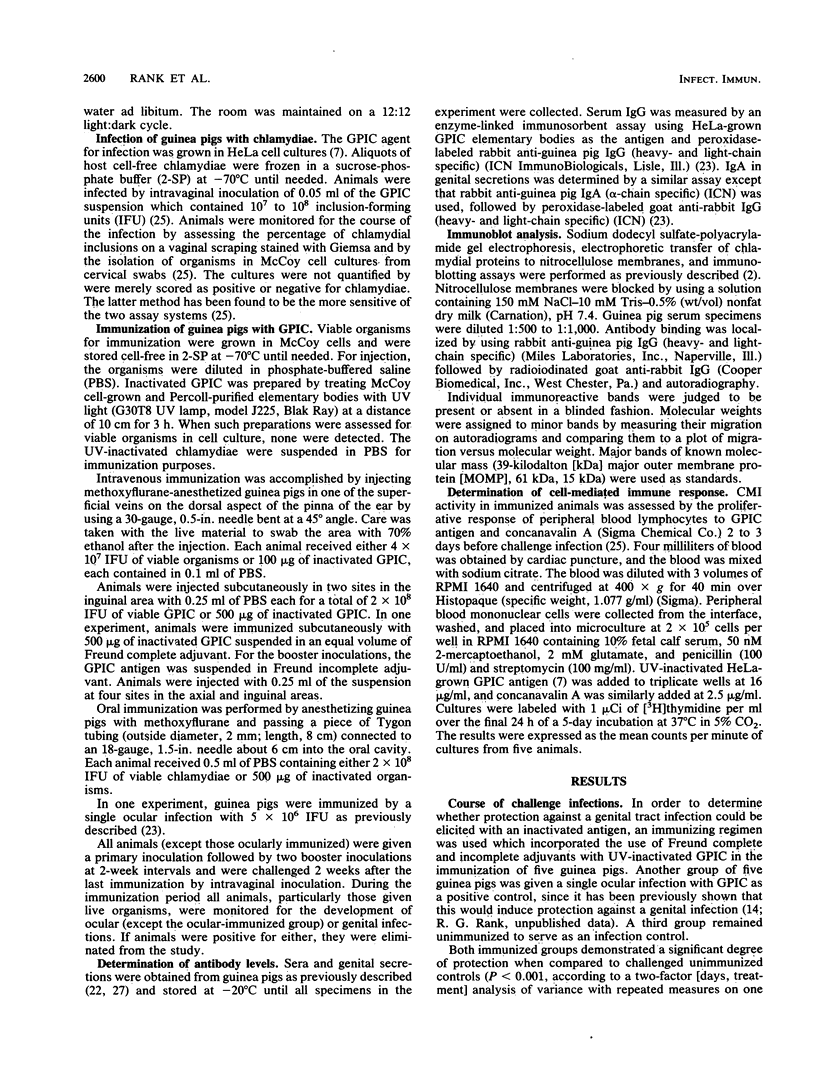

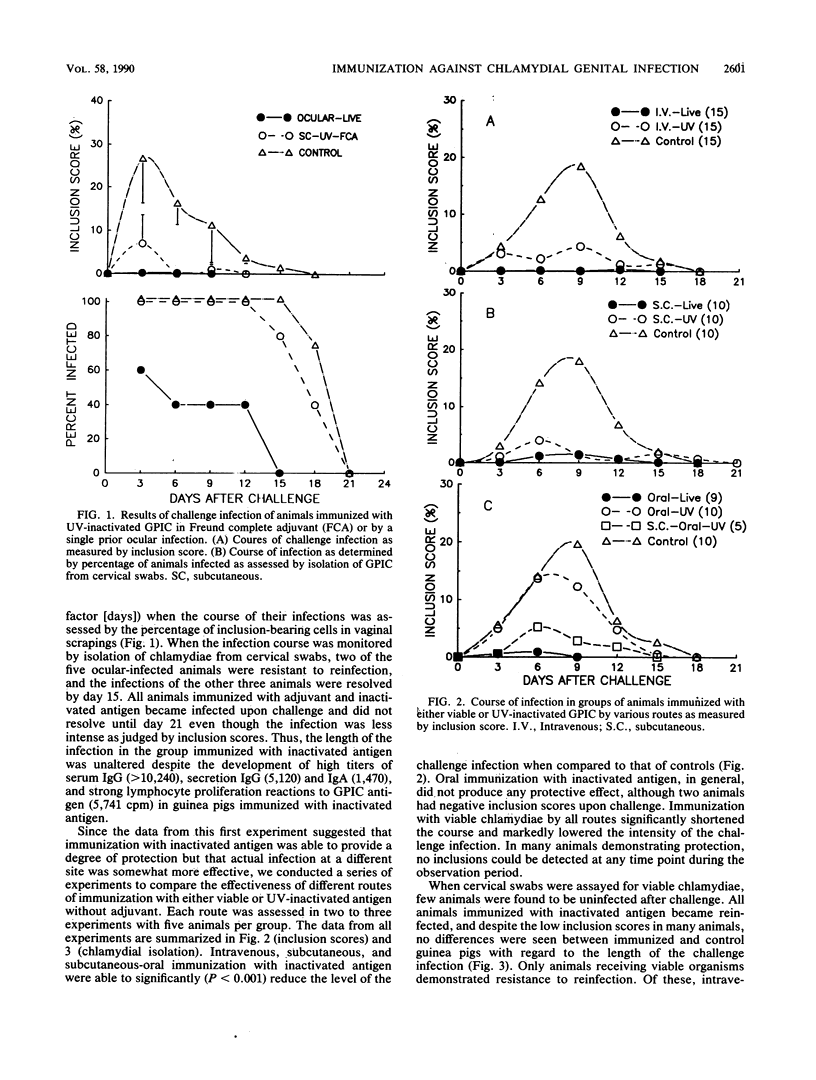

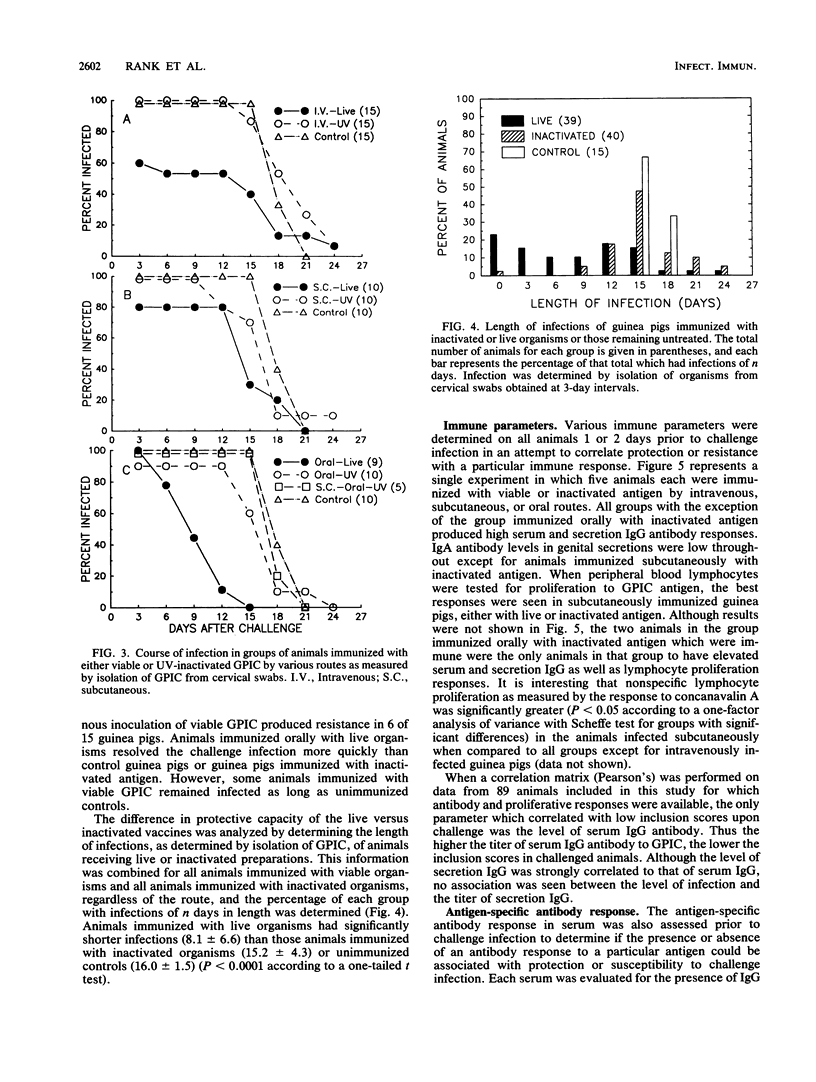

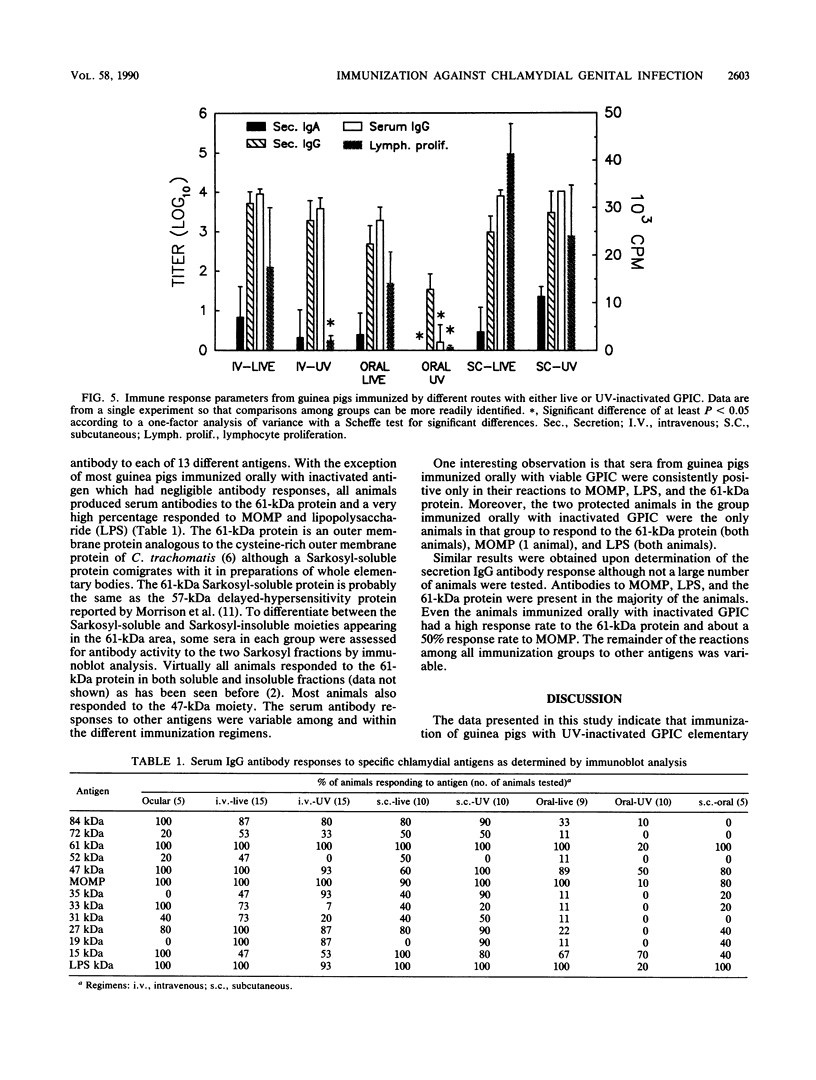

Female guinea pigs were immunized with viable or UV light-inactivated chlamydiae (agent of guinea pig inclusion conjunctivitis), belonging to the species Chlamydia psittaci, by intravenous, subcutaneous, oral, or ocular routes. All animals were then inoculated vaginally with viable chlamydiae to determine the extent of protection against challenge infection induced by the various regimens. The course of genital infection was significantly reduced in intensity in all groups of animals except the unimmunized controls and those animals immunized orally with inactivated antigen. Guinea pigs immunized with viable antigen were more likely to develop resistance to challenge infection and, in general, had a significantly greater degree of protection than animals immunized with inactivated antigen. No one route seemed superior in producing a protective response. Animals in all groups demonstrating protection developed serum and secretion immunoglobulin G antibody responses to chlamydiae. Lymphocyte proliferative reactions to chlamydial antigen were variable among groups. Immunoblot analysis of serum and secretions indicated a wide range of antibody specificities, but most protected animals produced antibodies to the major outer membrane protein, lipopolysaccharide, and the 61-kilodalton protein. No definitive associations could be made between the increased ability of immunization with viable organisms to produce resistance to challenge infection and a particular immune parameter. These data indicate that viable chlamydiae given by various routes are able to induce a strong immune response which can provide resistance against reinfection in some cases or at least reduce the degree of infection to a greater degree than inactivated antigen. However, complete resistance to genital tract infection may be difficult to obtain and alternate immunizations strategies may have to be developed.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Batteiger B. E., Rank R. G. Analysis of the humoral immune response to chlamydial genital infection in guinea pigs. Infect Immun. 1987 Aug;55(8):1767–1773. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.8.1767-1773.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan T. M., Eschenbach D. A., Knapp J. S., Holmes K. K. Gonococcal salpingitis is less likely to recur with Neisseria gonorrhoeae of the same principal outer membrane protein antigenic type. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980 Dec 1;138(7 Pt 2):978–980. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(80)91091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne G. I., Moulder J. W. Parasite-specified phagocytosis of Chlamydia psittaci and Chlamydia trachomatis by L and HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 1978 Feb;19(2):598–606. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.2.598-606.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell H. D., Perry L. J. Neutralization of Chlamydia trachomatis infectivity with antibodies to the major outer membrane protein. Infect Immun. 1982 Nov;38(2):745–754. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.2.745-754.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch T. P., Allan I., Pearce J. H. Structural and polypeptide differences between envelopes of infective and reproductive life cycle forms of Chlamydia spp. J Bacteriol. 1984 Jan;157(1):13–20. doi: 10.1128/jb.157.1.13-20.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hough A. J., Jr, Rank R. G. Induction of arthritis in C57B1/6 mice by chlamydial antigen. Effect of prior immunization or infection. Am J Pathol. 1988 Jan;130(1):163–172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard L. V., O'Leary M. P., Nichols R. L. Animal model studies of genital chlamydial infections. Immunity to re-infection with guinea-pig inclusion conjunctivitis agent in the urethra and eye of male guinea-pigs. Br J Vener Dis. 1976 Aug;52(4):261–265. doi: 10.1136/sti.52.4.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B. P., Batteiger B. E., Jones R. B. Effect of prior sexually transmitted disease on the isolation of Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Dis. 1987 Jul-Sep;14(3):160–164. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198707000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestecky J. The common mucosal immune system and current strategies for induction of immune responses in external secretions. J Clin Immunol. 1987 Jul;7(4):265–276. doi: 10.1007/BF00915547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison R. P., Belland R. J., Lyng K., Caldwell H. D. Chlamydial disease pathogenesis. The 57-kD chlamydial hypersensitivity antigen is a stress response protein. J Exp Med. 1989 Oct 1;170(4):1271–1283. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.4.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulder J. W., Hatch T. P., Byrne G. I., Kellogg K. R. Immediate toxicity of high multiplicities of Chlamydia psittaci for mouse fibroblasts (L cells). Infect Immun. 1976 Jul;14(1):277–289. doi: 10.1128/iai.14.1.277-289.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray E. S., Radcliffe F. T. Immunologic studies in guinea pigs with guinea pig inclusion conjunctivitis (GP-IC) Bedsonia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967 May;63(5 Suppl):1263–1269. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(67)94108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller I., Louis J. A. Immunity to experimental infection with Leishmania major: generation of protective L3T4+ T cell clones recognizing antigen(s) associated with live parasites. Eur J Immunol. 1989 May;19(5):865–871. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols R. L., Murray E. S., Nisson P. E. Use of enteric vaccines in protection against chlamydial infections of the genital tract and the eye of guinea pigs. J Infect Dis. 1978 Dec;138(6):742–746. doi: 10.1093/infdis/138.6.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton D. L., Kuo C. C. Histopathology of Chlamydia trachomatis salpingitis after primary and repeated reinfections in the monkey subcutaneous pocket model. J Reprod Fertil. 1989 Mar;85(2):647–656. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0850647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton D. L., Kuo C. C., Wang S. P., Halbert S. A. Distal tubal obstruction induced by repeated Chlamydia trachomatis salpingeal infections in pig-tailed macaques. J Infect Dis. 1987 Jun;155(6):1292–1299. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.6.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeling R., Maclean I. W., Brunham R. C. In vitro neutralization of Chlamydia trachomatis with monoclonal antibody to an epitope on the major outer membrane protein. Infect Immun. 1984 Nov;46(2):484–488. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.2.484-488.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank R. G., Barron A. L. Effect of antithymocyte serum on the course of chlamydial genital infection in female guinea pigs. Infect Immun. 1983 Aug;41(2):876–879. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.2.876-879.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank R. G., Barron A. L. Humoral immune response in acquired immunity to chlamydial genital infection of female guinea pigs. Infect Immun. 1983 Jan;39(1):463–465. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.1.463-465.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank R. G., Barron A. L. Specific effect of estradiol on the genital mucosal antibody response in chlamydial ocular and genital infections. Infect Immun. 1987 Sep;55(9):2317–2319. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2317-2319.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank R. G., Batteiger B. E. Protective role of serum antibody in immunity to chlamydial genital infection. Infect Immun. 1989 Jan;57(1):299–301. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.1.299-301.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank R. G., Batteiger B. E., Soderberg L. S. Susceptibility to reinfection after a primary chlamydial genital infection. Infect Immun. 1988 Sep;56(9):2243–2249. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.9.2243-2249.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank R. G., Soderberg L. S., Sanders M. M., Batteiger B. E. Role of cell-mediated immunity in the resolution of secondary chlamydial genital infection in guinea pigs infected with the agent of guinea pig inclusion conjunctivitis. Infect Immun. 1989 Mar;57(3):706–710. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.3.706-710.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank R. G., White H. J., Barron A. L. Humoral immunity in the resolution of genital infection in female guinea pigs infected with the agent of guinea pig inclusion conjunctivitis. Infect Immun. 1979 Nov;26(2):573–579. doi: 10.1128/iai.26.2.573-579.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor H. R., Johnson S. L., Prendergast R. A., Schachter J., Dawson C. R., Silverstein A. M. An animal model of trachoma II. The importance of repeated reinfection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1982 Oct;23(4):507–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor H. R., Johnson S. L., Schachter J., Caldwell H. D., Prendergast R. A. Pathogenesis of trachoma: the stimulus for inflammation. J Immunol. 1987 May 1;138(9):3023–3027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor H. R., Young E., MacDonald A. B., Schachter J., Prendergast R. A. Oral immunization against chlamydial eye infection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987 Feb;28(2):249–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. X., Stewart S. J., Caldwell H. D. Protective monoclonal antibodies to Chlamydia trachomatis serovar- and serogroup-specific major outer membrane protein determinants. Infect Immun. 1989 Feb;57(2):636–638. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.2.636-638.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. X., Stewart S., Joseph T., Taylor H. R., Caldwell H. D. Protective monoclonal antibodies recognize epitopes located on the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Immunol. 1987 Jan 15;138(2):575–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]