Abstract

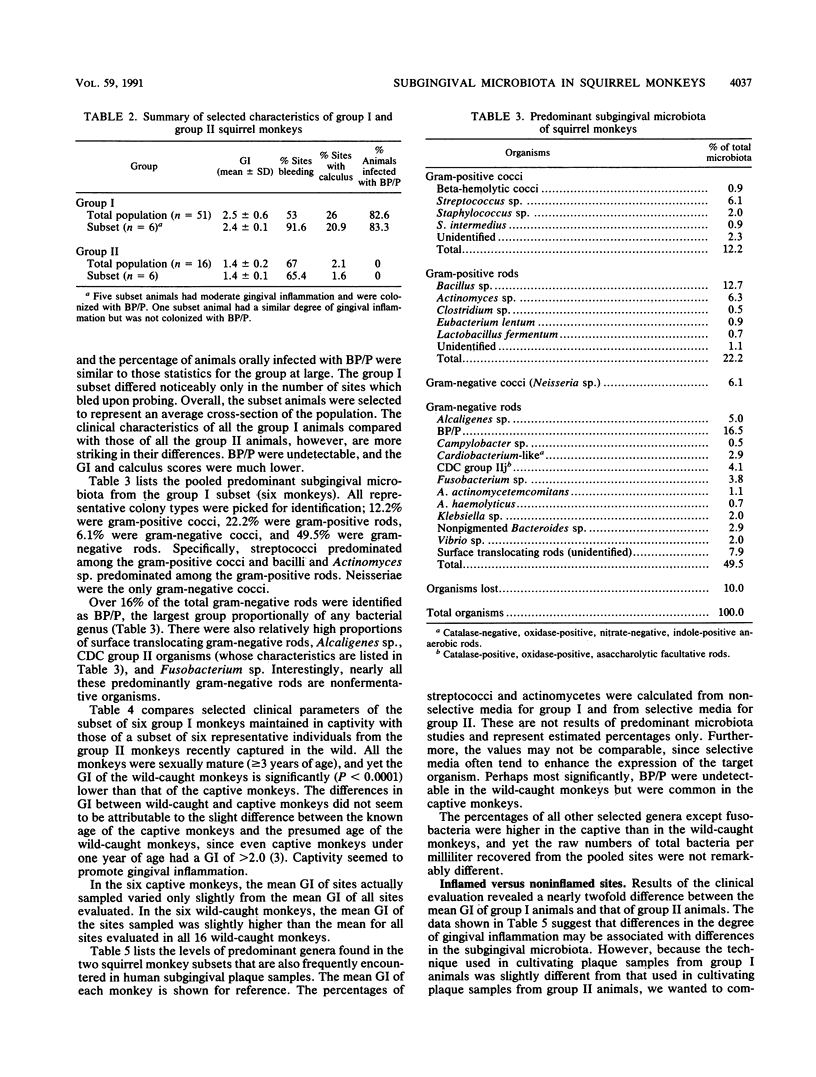

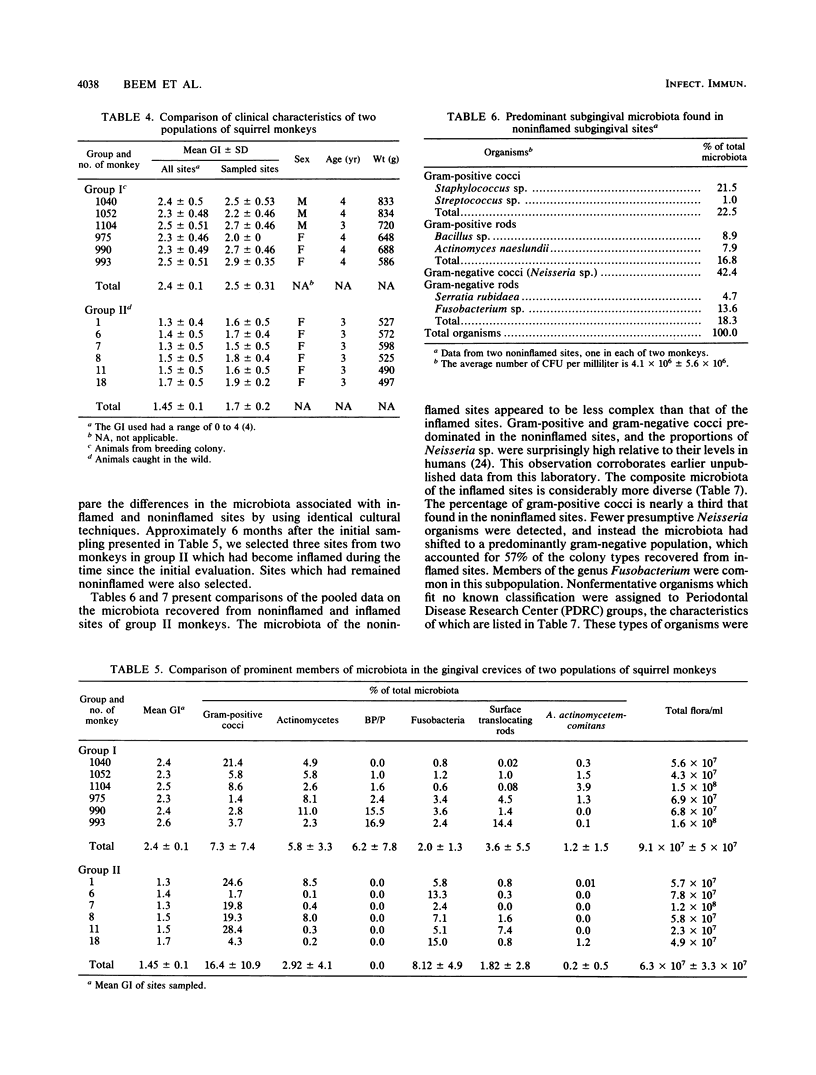

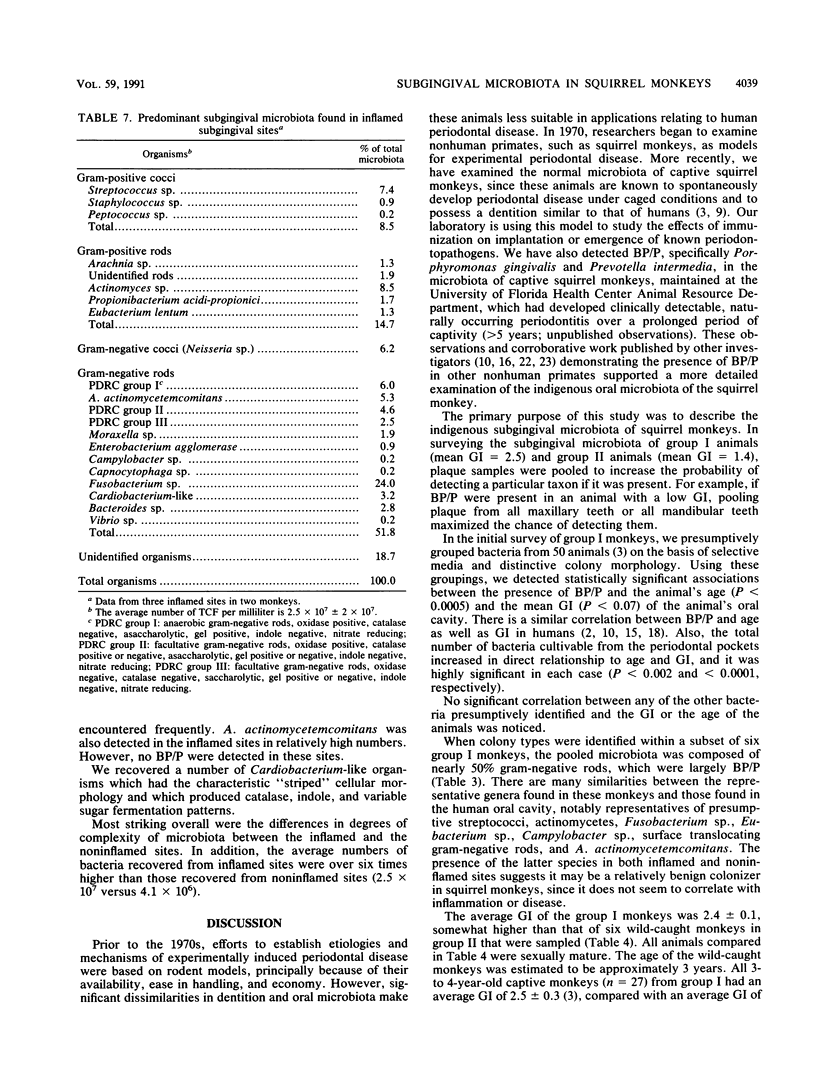

The squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus) has been proposed as an in vivo model for the study of subgingival colonization by suspected periodontopathogens, such as black-pigmented porphyromonads and prevotellas (BP/P). However, the indigenous microbiota of the squirrel monkey has not been well described. Therefore, in order to more fully characterize the oral microbiota of these animals, we studied two groups of squirrel monkeys from widely different sources. Group I consisted of 50 breeding colony monkeys ranging in age from 9 months to over 6 years which had been raised in captivity; group II consisted of 16 young sexually mature monkeys recently captured in the wild in Guyana. Group I animals in captivity had developed moderate to severe gingivitis, with a mean gingival index (GI) of 2.6; 52% of the sites bled, 26% had detectable calculus, and 83% had detectable BP/P. A group I subset (six animals), for which predominant cultivable microbiota was described, had a mean GI of 2.4. Colony morphology enumeration revealed that five of the six subset animals were detectably colonized with BP/P (range, 0 to 16.9%) and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (range, 0 to 3.9%); all subset animals were colonized with Fusobacterium species (range, 0.8 to 3.6%), Actinomyces species (range, 2.3 to 11%), and gram-positive cocci (range, 1.4 to 21.4%). Predominant cultivable microbiota results revealed the presence of many bacterial species commonly found in the human gingival sulcus. At baseline, group II animals were clinically healthy and had a mean GI of 1.4; 67% of the sites bled and 2.1% had calculus, and none of the animals had detectable BP/P. Neisseriae were very common in noninflamed sites. Subsequently, when inflamed sites were compared with noninflamed sites in group II animals after they had been maintained in captivity for 6 months, inflamed sites exhibited a more complex microbiota and increased proportions of gram-negative rods and asaccharolytic bacteria.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adams R. A., Zander H. A., Polson A. M. Interproximal and buccal cell populations apical to the sulcus before and during experimental periodontitis in squirrel monkeys. J Periodontol. 1981 Aug;52(8):416–419. doi: 10.1902/jop.1981.52.8.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAILIT H. L., BALDWIN D. C., HUNT E. E., Jr THE INCREASING PREVALENCE OF GINGIVAL BACTEROIDES MELANINOGENICUS WITH AGE IN CHILDREN. Arch Oral Biol. 1964 Jul-Aug;9:435–438. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(64)90028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark W. B., Magnusson I., Abee C., Collins B., Beem J. E., McArthur W. P. Natural occurrence of black-pigmented Bacteroides species in the gingival crevice of the squirrel monkey. Infect Immun. 1988 Sep;56(9):2392–2399. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.9.2392-2399.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J. M., Lamster I. B., Seiger M. C. Efficacy of Listerine antiseptic in inhibiting the development of plaque and gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1985 Sep;12(8):697–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1985.tb00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijl L., Rifkin B. R., Zander H. A. Conversion of chronic gingivitis to periodontitis in squirrel monkeys. J Periodontol. 1976 Dec;47(12):710–716. doi: 10.1902/jop.1976.47.12.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman J. D., Socransky S. S., Shivers M. The relationships between streptococcal species and periodontopathic bacteria in human dental plaque. Arch Oral Biol. 1985;30(11-12):791–795. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(85)90133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt S. C., Ebersole J., Felton J., Brunsvold M., Kornman K. S. Implantation of Bacteroides gingivalis in nonhuman primates initiates progression of periodontitis. Science. 1988 Jan 1;239(4835):55–57. doi: 10.1126/science.3336774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy J. E., Polson A. M. Experimental marginal periodontitis in squirrel monkeys. J Periodontol. 1973 Mar;44(3):140–144. doi: 10.1902/jop.1973.44.3.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornman K. S., Holt S. C., Robertson P. B. The microbiology of ligature-induced periodontitis in the cynomolgus monkey. J Periodontal Res. 1981 Jul;16(4):363–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1981.tb00987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krygier G., Genco R. J., Mashimo P. A., Hausmann E. Experimental gingivitis in Macaca speciosa monkeys: clinical, bacteriologic and histologic similarities to human gingivitis. J Periodontol. 1973 Aug;44(8):454–463. doi: 10.1902/jop.1973.44.8.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOE H., SILNESS J. PERIODONTAL DISEASE IN PREGNANCY. I. PREVALENCE AND SEVERITY. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963 Dec;21:533–551. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggott P. J., Anderson A. W., Punwani I., Sabet T., Murphy R., Crawford J. Phase contrast microscopy of microbial aggregates in the gingival sulcus of Macaca mulatta. Subgingival plaque bacteria in macaca mulatta. J Clin Periodontol. 1983 Jul;10(4):412–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1983.tb01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansheim B. J., Stenstrom M. L., Low S. B., Clark W. B. Measurement of serum and salivary antibodies to the oral pathogen Bacteroides asaccharolyticus in human subjects. Arch Oral Biol. 1980;25(8-9):553–557. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(80)90067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashimo P. A., Ellison S. A., Slots J. Microbial composition of monkey dental plaque (Macaca arctoides and Macaca fascicularis). Scand J Dent Res. 1979 Feb;87(1):24–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1979.tb01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur W. P., Magnusson I., Marks R. G., Clark W. B. Modulation of colonization by black-pigmented Bacteroides species in squirrel monkeys by immunization with Bacteroides gingivalis. Infect Immun. 1989 Aug;57(8):2313–2317. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.8.2313-2317.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin B. R., Heijl L. The occurrence of mononuclear cells at sites of osteoclastic bone resorption in experimental periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1979 Dec;50(12):636–640. doi: 10.1902/jop.1979.50.12.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slots J., Hausmann E. Longitudinal study of experimentally induced periodontal disease in Macaca arctoides: relationship between microflora and alveolar bone loss. Infect Immun. 1979 Feb;23(2):260–269. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.2.260-269.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slots J. Rapid identification of important periodontal microorganisms by cultivation. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1986 Nov;1(1):48–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1986.tb00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slots J. Selective medium for isolation of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Clin Microbiol. 1982 Apr;15(4):606–609. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.4.606-609.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed S. A., Loesche W. J. Bacteriology of human experimental gingivitis: effect of plaque age. Infect Immun. 1978 Sep;21(3):821–829. doi: 10.1128/iai.21.3.821-829.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed S. A., Svanberg M., Svanberg G. The predominant cultivable dental plaque flora of beagle dogs with gingivitis. J Periodontal Res. 1980 Mar;15(2):123–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1980.tb00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zylber L. J., Jordan H. V. Development of a selective medium for detection and enumeration of Actinomyces viscosus and Actinomyces naeslundii in dental plaque. J Clin Microbiol. 1982 Feb;15(2):253–259. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.2.253-259.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]