Abstract

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes undergo directed movement to sites of infection, a complex process known as chemotaxis. Extension of the polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) leading edge toward a chemoattractant in association with uropod retraction must involve a coordinated increase/decrease in membrane, redistribution of cell volume, or both. Deficits in PMN phagocytosis and trans-endothelial migration, both highly motile PMN functions, suggested that the anion transporters, ClC-3 and IClswell, are involved in cell motility and shape change (Moreland, J. G., Davis, A. P., Bailey, G., Nauseef, W. M., and Lamb, F. S. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 ,12277 -12288). We hypothesized that ClC-3 and IClswell are required for normal PMN chemotaxis through regulation of cell volume and shape change. Using complementary chemotaxis assays, EZ-TAXIScan™ and dynamic imaging analysis software, we analyzed the directed cell movement and morphology of PMNs lacking normal anion transporter function. Murine Clcn3-/- PMNs and human PMNs treated with anion transporter inhibitors demonstrated impaired chemotaxis in response to formyl peptide. This included decreased cell velocity and failure to undergo normal cycles of elongation and retraction. Impaired chemotaxis was not due to a diminished number of formyl peptide receptors in either murine or human PMNs, as measured by flow cytometry. Murine Clcn3-/- and Clcn3+/+ PMNs demonstrated a similar regulatory volume decrease, indicating that the IClswell response to hypotonic challenge was intact in these cells. We further demonstrated that IClswell is essential for shape change during human PMN chemotaxis. We speculate that ClC-3 and IClswell have unique roles in regulation of PMN chemotaxis; IClswell through direct effects on PMN volume and ClC-3 through regulation of IClswell.

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs)2 play an essential role in the innate immune system and undergo directed movement to sites of infection or inflammation, a process known as chemotaxis. Mobilized by chemoattractant (CA) gradients, PMNs move out of the vasculature, across the endothelium, and into infected tissues. Seven-transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptors transduce the CA stimulus into intracellular signals that initiate polymerization of F-actin and extension of the PMN leading edge (2). Specific downstream intracellular signals control subcellular localization of the cytoskeleton, prevent random pseudopod extension, and induce retraction of the myosin-enriched uropod (3). In this way, PMNs achieve directed movement toward a CA source.

During the classical chemotaxis movement cycle, PMNs transform from nearly spherical to a flattened and elongated shape (4). Repetitive phases of PMN cell polarization, with leading edge extension toward a CA stimulus and uropod retraction, must involve a directed increase/decrease in membrane surface area, a redistribution of cytoplasmic volume, or both. Although much is known about the role of the actin cytoskeleton in cell motility, less is understood about the mechanism by which a cell regulates its membrane/volume balance to promote efficient motility. In the Schwab ion transport model of cell migration, ion channels involved in volume regulation are spatially polarized in motile cells, thus promoting a volume increase at the leading edge for pseudopod protrusion and a volume decrease at the trailing edge for retraction of the uropod (5). Cell volume increases have been described in PMNs responding to CA gradients (6), but a requirement for anion transporters in this process has not previously been described.

Although the role of cell volume regulation in PMN chemotaxis is unknown, the process is well characterized in response to hypotonic stress (7). As with all mammalian cells, ion flux and osmotic pressure gradients across the plasma membrane maintain cytoplasmic volume. Hypotonic challenge activates the swelling-induced chloride conductance, IClswell, as well as a K+ conductance (8). These parallel effects mediate Cl- and K+ efflux, which drives water out of the cell, a process termed the regulatory cell volume decrease (RVD). PMNs exhibit a volume-activated chloride conductance similar to the IClswell found in other mammalian cells (9). Although the electrophysiological characteristics of the IClswell have been well defined (10), the molecular identity of the IClswell channel responsible for the RVD remains to be determined.

Of significance, PMNs maintain an intracellular Cl- concentration (∼80 meq/liter) that is 4 times higher than would be expected for passive diffusion of Cl- at the estimated PMN membrane potential (∼-53 mV); this implies that accumulation of intracellular Cl- requires active energy expenditure (11). Stimulation of PMNs by several different CAs, including formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLF), C5a, and interleukin-8, is associated with a marked Cl- efflux (12), indicating a role for anion/Cl- flux during cell motility. Multiple Cl- transporters and channels have been functionally characterized in PMNs, including, among others, Ca2+-activated channels (13), the Na+-K+-2Cl- exchanger (11), the Cl--HCO3 exchanger (14), and swelling-induced chloride channels (9). We have recently described the expression of and requirement for the voltage-gated chloride/proton antiporter, ClC-3 (chloride channel-3) (15), in PMN function (1).

We became interested in the role of ClC-3 in PMN motility after finding dramatic inhibition of trans-endothelial migration by niflumic acid, a nonselective inhibitor of ClC-3 function (1). PMNs treated with tamoxifen, which does not inhibit ClC-3 but does block the IClswell (15), also demonstrate failure of transendothelial migration. In addition, PMNs with absent or impaired ClC-3 function have decreased phagocytosis compared with controls (1). We have recently proposed that ClC-3 and IClswell are distinct anion pathways that are functionally linked, because ClC-3 participates in the regulation of IClswell by hydrogen peroxide (15). ClC-3 is required for reactive oxygen species generation via the NADPH oxidase in vascular smooth muscle cells (16) and appears to play a regulatory role in priming-induced oxidant signaling in PMNs (17). Taken together, the observed deficits in PMN phagocytosis and transendothelial migration suggested that ClC-3 and IClswell are involved in cell motility and shape change.

We hypothesized that ClC-3 and IClswell are required for normal PMN chemotaxis through regulation of cell volume and shape change. In order to investigate possible motility defects in PMNs with absent or impaired anion transporter function, we employed two complementary methods to analyze directed cell movement, the EZ-TAXIScan™ chemotaxis assay and the dynamic imaging analysis software (DIAS) chemotaxis assay. Murine Clcn3-/- and human PMNs treated with anion transporter inhibitors demonstrated impaired chemotaxis and failed to elongate and retract normally during stimulation with an fMLF spatial gradient. We conclude that anion transporter function plays an important role in PMN cell motility and that ClC-3 and IClswell have unique roles in PMN chemotaxis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents—Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) and Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline were obtained from BioWhittaker (Walkersville, MD). HBSS-BG was prepared by adding 0.1% bovine serum albumin and 1% d-glucose to HBSS without divalent cations (Ca2+ and Mg2+) and was used for murine bone marrow isolation. EZ-TAXIScan™ buffer (EZT buffer) was composed of 20 mm HEPES and 0.1% human serum albumin in HBSS with divalent cations, pH 7.40. DIAS buffer was composed of 20 mm HEPES in HBSS with divalent cations, pH 7.40. Unless otherwise specified, reagents were obtained from Sigma. fMLF was diluted to 10 mm stock solution in DMSO and stored at -20 °C. Niflumic acid (NFA) was dissolved in DMSO and used at a final concentration of 1 mm, as described. Tamoxifen was dissolved in DMSO and used at concentrations of 1, 5, and 10 μm, as described. The estrogen receptor antagonist ICI 182,780 was purchased from Tocris Bioscience Co. (Ellisville, MO).

Clcn3-/- Mice Generation—Generation of Clcn3-/- mice has been previously described (18). All animals had free access to food and water. Experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Iowa.

Murine Bone Marrow Leukocyte Isolation—Murine bone marrow leukocyte isolation was performed using a modification of a previously described protocol, and cells were kept on ice prior to use (19). Briefly, mice were anesthetized using inhaled isoflurane, and cervical dislocation was performed. Skin was cleansed with alcohol and resected. Iliac, femur, and tibia were removed bilaterally, cleaned of debris, and washed in buffer twice, and bone marrow cavities were flushed with HBSS-BG. Marrow collections were pelleted at 450 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. PMNs were then resuspended in 45% Percoll-Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline solution and aspirated twice through a 22-gauge needle and syringe to break up dense bone marrow collections. PMN-Percoll solutions were layered atop a Percoll density gradient (prepared by underlaying 2 ml of 50, 55, and 62% and 3 ml of 81% Percoll-Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline solutions) and centrifuged at 1800 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. PMNs were collected from the 81-62% Percoll solution interface, washed twice with 10 ml of HBSS-BG (450 × g for 5 min at 4 °C), and resuspended in buffer. Cell counts were obtained from bone marrow isolates by hemocytometer, and differential analysis was performed using Diff Quick cytospin staining.

Human PMN Purification—Human PMNs were isolated from the heparin anticoagulated venous blood of healthy consenting adults using standard techniques and in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects at the University of Iowa. PMN purification included dextran sedimentation and Hypaque-Ficoll density gradient separation, followed by hypotonic lysis of erythrocytes as previously described (1). Purified PMNs were resuspended in divalent cation-free HBSS and kept on ice prior to use in experimental assays.

Cell Viability—Trypan blue exclusion was performed to determine cell viability after treatment with phloretin, as previously described (1). Human PMNs were diluted to 2 × 106 PMN/ml and incubated with the inhibitor for 10, 30, and 60 min. Equal volumes of 0.4% trypan blue and treated cells were incubated together for 3 min before counting on a hemocytometer to assess the percentage of trypan blue-stained cells. A minimum of 400 cells/condition was counted.

Chemotaxis Assays—For the EZ-TAXIScan™ and DIAS chemotaxis assays, we chose to use fMLF as the CA, because it has been studied extensively in both human and murine PMN chemotaxis. Although murine PMNs lack receptors for human PMN CAs, such as CXCR1, CXCL8 (interleukin-8 receptor), and neutrophil-activating peptide-2 receptors, both species have receptors responsible for sensing fMLF spatial gradients (20, 21).

EZ-TAXIScan™ Assays—EZ-TAXIScan™ assays (Effector Cell Institute, Tokyo) were performed at 37 °C using the assembled chemotaxis apparatus, composed of the chip holder and silicone chip perfused in EZT buffer, as described (22). Briefly, PMNs were kept at a concentration of 1 × 107 in divalent cation-free HBSS and then diluted to 1 × 106/ml in EZT buffer (control) or treated with DMSO (vehicle control), NFA (1 mm), or tamoxifen (1, 5, or 10 μm), and PMNs were incubated for 5 min at 37 °C. In each of six separate channels, a PMN suspension (∼5 μl of 1 × 106 PMN/ml) was injected with a 10-μm microsyringe, and cells were aligned along the edge of the chamber using the fluid flow technique. Buffer menisci were leveled and provided the osmotic pressure required to develop the spatial CA gradient. Based on our loading concentration curves, 1 μl of fMLF was then injected in the stimulus chamber opposite to the PMN chamber, and the chemotactic spatial gradient was allowed to form. Data were recorded channel by channel at 1-s time lapse intervals between channels, using an XY stage robot (Torii Systems, Tokyo, Japan) and a high performance ×9 objective lens connected to a charge-coupled device camera, time lapse video recorder (Nikon, Kawasaki, Japan) with a coaxial episcopic illumination system (Watec America, Las Vegas, NV). The amount of fMLF loaded into the chemotaxis chamber (1 μl) was rapidly dispersed and created a stable spatial CA gradient based on the osmotic pressure of the chamber. Uniformity and reproducibility of CA spatial gradients in the EZ-TAXIScan™ system have been described using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) diffusion as well as a computer simulation for small molecular weight peptides (22). Chemotaxis assays were filmed for 60 min, with an image collection rate of 3 frames/min for each of the six channels. Movies were analyzed using Image J software. Cells moving at a velocity of less than 3 μm/min were considered nonmotile and were not included in the calculation of average chemotaxis parameters, except in the case of 10 μm tamoxifen treatment, after which nearly all the cells moved less than 3 μm/min. Cells were manually tracked, and the percentage of motile cells from each experimental condition was calculated. The chemotactic index (CI) was calculated as the ratio of net path length toward the CA to total path length. Average instantaneous velocity for individual cells was also assessed using Image J software, with xy coordinates scaled for 1 μm in accordance with the manufacturer's specifications. Chemotaxis parameters were computed using data obtained from individual cell tracks from at least five separate experiments, with at least 50 cells analyzed per condition.

Two-dimensional DIAS Chemotaxis Assay—PMN behavior in an fMLF spatial gradient was evaluated as previously described (23). Briefly, 60 μl of the above 1 × 106/ml PMN treatment solutions was applied to a 24 × 50-mm rectangular glass coverslip, and PMNs were allowed to adhere for 5 min at room temperature. Using a Zigmond chemotaxis chamber composed of a glass bridge with two bordering troughs, the coverslip was inverted onto the chamber with PMNs aligned over the chamber's bridge (24, 25). One trough was filled with buffer alone, the other trough was filled with buffer containing fMLF, and the gradient was formed by completing the chamber with a second coverslip. Cells were incubated for 5 min at 37 °C to allow formation of the steep spatial gradient. PMNs were video-recorded for 10 min using bright field optics at ×25 magnification. Cell images were recorded directly onto the hard drive of a Macintosh G4 computer (Apple Computers, Cupertino, CA), using Quick Time or iStop Motion software with an analog to digital converter (ADVC55 converter from Canopus, Co., San Jose, CA) and two-dimensional DIAS software (26-28) at a rate of 15 frames/min (4-s intervals). As with the EZ-TAXIScan™ assay, cells moving at a velocity less than 3 μm/min were considered nonmotile and were not included in the calculation of average cell morphology parameters, except in the case of 10 μm tamoxifen treatment, which caused nearly all of the cells to move less than 3 μm/min. Cell image perimeters were automatically traced, manually verified, and converted to β-spline replacement images. Replacement images were used to compute the cell centroid, and measurements of cell motility and dynamic morphology were calculated based on the position of the centroid and the cell contour (26, 28). “Percentage roundness” was computed by the formula 100 × 4π × (area/perimeter2). The computation “mean width” was the average of all chords perpendicular to the maximum length chord. “Maximum length” was computed as the longest chord between any two points on the cell perimeter. Radial deviation was computed as the ratio of the S.D. of the mean radial length to the mean radial length itself, expressed as a percentage. Mean radial length was computed as the average distance from individual boundary pixels on the cell image perimeter to the centroid of the cell image. Convexity and concavity were computed by drawing line segments connecting the vertices of the final shape. Angles of turning from one segment to the next were measured. Convexity was defined as the total sum of the positive turning angles, whereas concavity was defined as the absolute value of the sum of the negative turning angles. Difference pictures were generated by superimposing the outline at frame n - 3 over frame n. The area into which the cell expanded during that interval was color-coded green, the area from which it retracted was color-coded red, and the common area remained gray. Morphology parameters were computed using measurements obtained from individual cell tracings from at least three separate experiments, with at least 50 cells analyzed per condition.

Analysis of Cell Swelling by Coulter Counter—Murine and human PMNs were analyzed for mean cell volume at room temperature using the Beckman Coulter Z2 Particle Count and Size Analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA) with a 100-μm orifice, calibrated to count all particles with a cell volume greater than 80 fl. Murine and human PMNs were maintained at a concentration of 5 × 103/ml to obtain cell size measurements. Initial measurements were obtained to show that human PMN anion transporter inhibitors did not cause an increase in cell size prior to the addition of water. Murine Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3-/- PMNs and human PMNs treated with DMSO (control), 1 mm NFA, and 100 μm phloretin were then subjected to hypotonic challenge with the addition of sterile water at 25 or 50% of the final volume, and cell size was followed for 35 min. The mean cell volume was calculated for each cell population using the Coulter Channelyzer C1000 with Accucomp software and normalized to base-line volumes.

Analysis of Cell Swelling by Flow Cytometry—Murine and human PMNs were analyzed for forward scatter contours (FSC) by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences), as described (1). Human PMNs were maintained at 1 × 106/ml to obtain base-line FSC histograms. Following determination of base-line forward and side scatter profiles for 2 min, DMSO-treated control and NFA-treated PMNs in isotonic buffer were subjected to hypotonic challenge with the addition of sterile water at 25% of the final volume. Forward and side scatter histograms were then obtained at 30 s posthypotonic challenge, followed by 1-min intervals for 10 min and then 10-min intervals up to 30 min. Murine PMNs were maintained at a concentration of 6 × 105/ml in HBSS with divalent cations for 2 min to obtain base-line FSC contours. Murine PMNs were then subjected to 25% hypotonic challenge with the addition of sterile water. Murine cell swelling was analyzed with a kinetic program that permitted continuous measurement of FSC at 1-s intervals for 18 min. At each time point analyzed, individual FSC profiles were normalized as a percentage of base-line FSC measurements and averaged across experiments.

Analysis of fMLF Receptor Expression by Flow Cytometry—PMN fMLF receptor surface expression was determined by FACS analysis using a described protocol (29). Briefly, murine and human PMNs were stimulated with fMLF (100 nm) or were maintained at rest. Human PMNs were also stimulated with the calcium ionophore ionomycin (500 nm) to mobilize surface expression of the fMLF receptor as a positive control. PMNs were then fixed for 30 min in ice-cold paraformaldehyde (4% (w/v) in phosphate-buffered saline) and washed. To determine surface expression of the fMLF receptor (fMLF-R), an FITC-conjugated, formylated peptide (FITC-FNLPNTL; 10 nm final concentration) was added to a PMN suspension (1 × 106 of paraformaldehyde-fixed cells in 400 μl) with or without an excess amount (5 μm) of unlabeled fMLF, which inhibited FITC-FNLPNTL binding. Unlabeled fMLF-treated samples were incubated at 22 °C for 15 min to equilibrate. FITC-FNLPNTL was then added and allowed to incubate at 22 °C for 30 min, with no washing performed after labeling. The amount of FITC-FNLPNTL specifically bound to the PMNs (corresponding to the amount of surface fMLF-R expression) was determined by flow cytometry. fMLF-R surface density was calculated using the geometric mean intensity of FITC signal of fMLF-R ligand-treated PMNs compared with untreated PMNs.

Statistical Analysis—Results are expressed as means ± S.E. Statistical comparisons were performed by Student's t test, Mann-Whitney test, or two-way analysis of variance with the Bonferroni test to analyze data with unequal variance between groups as appropriate. A probability level of 0.05 was considered significant. Percentage motility of PMN populations was assessed using χ2 analysis.

RESULTS

Absence of ClC-3 Impaired Chemotaxis in Murine PMN—Based on our findings that Clcn3-/- PMNs have defective phagocytosis and that inhibition of anion transporter function in human PMNs impairs phagocytosis and trans-endothelial migration (1), we reasoned that ClC-3 may be required for normal PMN chemotaxis. We used the EZ-TAXIScan™ system to assess chemotaxis in murine Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3-/- PMNs. Cell isolates prepared from bone marrow of Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3-/- mice were 85 ± 4% and 88 ± 3% PMNs, respectively, and the remaining cells were evenly distributed between lymphocyte and monocyte lineages, (n = 6 experiments with paired mice, 100 cells/sample). We studied PMN chemotaxis in response to fMLF, a prototypical CA and bacterial peptide analog, since it has been widely characterized in both human and murine PMN chemotaxis. Because no prior chemotaxis studies had been published using murine PMNs in the EZ-TAXIScan™ system, we performed a dose-response analysis across a wide range of loading concentrations of fMLF. Optimal chemotactic response was determined by the maximal average chemotactic index of cells responding to a given fMLF spatial gradient. Based on their location in the spatial gradient, PMNs were exposed to a CA concentration ∼2 logs lower than the loading concentration of fMLF (22). Our data, which demonstrated an optimal response at 100 μm fMLF loading concentration, were therefore consistent with published reports of murine PMN optimal chemotactic response to 1 μm fMLF in a Boyden chamber model (30).

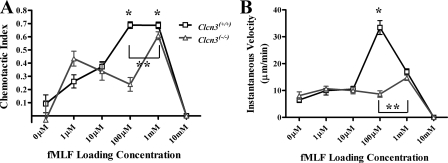

Compared with Clcn3+/+ PMNs, murine PMNs lacking ClC-3 demonstrated an impaired peak response to fMLF. As is typical of the PMN response to chemotactic agents, the Clcn3+/+ PMNs response to a range of fMLF concentrations was distributed in a skewed curve, with lower levels of chemotaxis in response to 1 μm fMLF, peak response at 100 μm fMLF, and complete inhibition of chemotaxis in response to excess CA, 10 mm fMLF (Fig. 1A). Clcn3+/+ PMNs responding to 1 mm fMLF had an average chemotactic index similar to those of PMNs responding to 100 μm fMLF, meaning that they moved in a straight line toward the CA source. However, the average instantaneous velocity was significantly decreased in Clcn3+/+ PMNs responding to 1 mm fMLF as opposed to 100 μm fMLF (Fig. 1B), as was the average net path length of the cells (76.0 ± 6.0 versus 135.9 ± 10.8 μm, respectively, p < 0.05). These data indicated that 1 mm fMLF was also an excess CA loading concentration, inhibitory to chemotaxis, and that 100 μm fMLF was the optimal loading concentration for Clcn3+/+ PMNs. In contrast, murine PMNs lacking ClC-3 required a 10-fold higher fMLF concentration (1 mm) to achieve a maximal chemotactic response (CI 0.61 ± 0.03) than did Clcn3+/+ PMNs and did not achieve the same degree of directed movement reached by wild type cells. Although the shape of the chemotactic response curve observed in ClC-3-deficient PMNs appeared complex, with increased variability at suboptimal CA concentrations, the Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3-/- PMN CI curves were not significantly different at low concentrations of fMLF or during random movement in the absence of CA (0 μm).

FIGURE 1.

Chemotactic index and velocity of Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3-/- PMNs in response to increasing fMLF spatial gradients using the EZ-TAXIScan™ chemotaxis assay. A, Clcn3-/- PMNs had a significantly diminished average chemotactic index in response to 100 μm (n = 6) and 1 mm (n = 8) loading concentrations of the CA fMLF compared with Clcn3+/+ PMNs. *, p ≤ 0.05. Clcn3-/- PMNs required a 10-fold higher fMLF concentration to achieve maximal chemotaxis and never reached the peak chemotactic index seen with Clcn3+/+ PMNs. **, p ≤ 0.05. B, Clcn3-/- PMNs had a significantly diminished average instantaneous velocity in response to 100 μm (n = 6) loading concentration of fMLF compared with Clcn3+/+ PMNs; *, p ≤ 0.05. Clcn3-/- PMNs required a 10-fold higher fMLF concentration to achieve maximal velocity and never reached the peak velocity seen with Clcn3+/+ PMNs. **, p ≤ 0.05. Values are means ± S.E.

Absence of ClC-3 Inhibited Cell Velocity in Murine PMNs—The impaired response to fMLF seen in PMNs lacking ClC-3 function was also demonstrated by diminished average instantaneous velocity compared with Clcn3+/+ PMNs (Fig. 1B). In response to the optimal concentration of fMLF (100 μm), Clcn3+/+ PMNs moved with an average speed of 33.4 ± 2.6 μm/min, as compared with 8.7 ± 1.2 μm/min for Clcn3-/- PMNs responding to the same CA concentration (p < 0.0001). In response to the optimal fMLF concentration for Clcn3-/- PMN chemotaxis (1 mm), the maximal average instantaneous velocity of Clcn3-/- PMNs (14.74 ± 1.0 μm/min) was less than half the maximal velocity of the Clcn3+/+ PMNs. The velocity of Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3-/- PMNs did not differ at low concentrations of fMLF or during random movement in the absence of CA (0 μm).

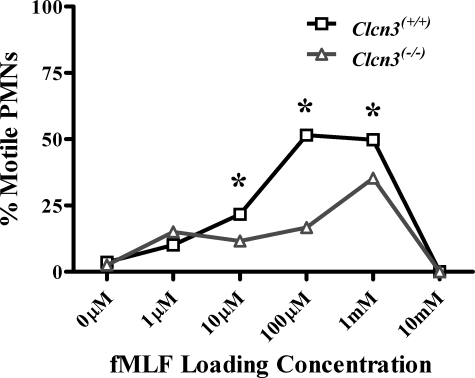

Fewer Motile PMNs in Clcn3-/- Population—In addition to the specific defects in CI and velocity demonstrated by Clcn3-/- PMNs, population analysis revealed a significantly lower percentage of motile cells among Clcn3-/- PMNs compared with Clcn3+/+ PMNs. In order to be inclusive, we selected a low velocity, 3.0 μm/min, as the definition of a motile cell. An average instantaneous velocity of 3.0 μm/min was less than one-tenth of the average velocity of Clcn3+/+ PMNs migrating in response to the optimal fMLF loading concentration. Only 35.3% of Clcn3-/- PMNs responding to their optimal fMLF concentration (1 mm) met the criterion of a motile cell, compared with 51.5% of the Clcn3+/+ PMNs responding to their optimal fMLF concentration (100 μm) (Fig. 2). There were significantly fewer motile Clcn3-/- PMNs than Clcn3+/+ PMNs at three different fMLF spatial gradients (10 μm, 100 μm, and 1 mm loading concentration). Taken together, these data indicated that ClC-3 function was required for normal cell motility and chemotaxis.

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3-/- PMNs motile response to increasing fMLF spatial gradients using the EZ-TAXIScan™ chemotaxis assay. By χ2 analysis, a significantly reduced number of motile cells was seen in the Clcn3-/- PMN population in response to 10 μm (n = 8), 100 μm (n = 6), and 1 mm (n = 8) loading concentrations of fMLF compared with Clcn3+/+. *, p ≤ 0.05. Values are the percentage of motile cells in the entire population, with ≥200 total cells/condition.

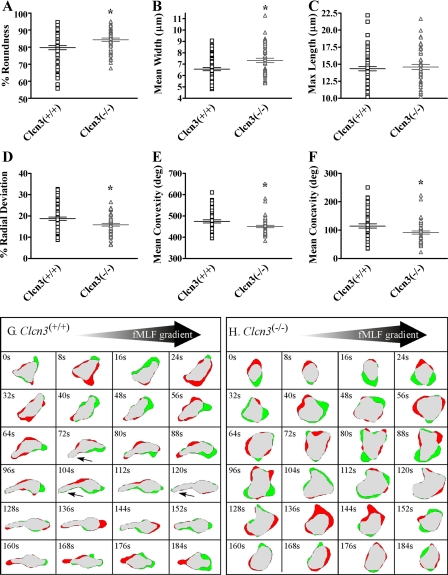

Absence of ClC-3 Impaired PMN Elongation and Retraction—We hypothesized that if ClC-3 were involved in cell volume regulation, then the anion transporter would be required for normal shape change during chemotaxis, and, as a consequence, the chemotactic and velocity deficits observed in Clcn3-/- PMNs would be associated with impaired pseudopod extension and uropod retraction. To test this hypothesis, we used high resolution two-dimensional DIAS to explore the morphology of PMNs during chemotaxis. In response to the optimal concentration of fMLF in this assay (500 μm), the average cell roundness of Clcn3-/- PMNs was significantly increased compared with Clcn3+/+ PMNs (Fig. 3A). Clcn3-/- PMNs also demonstrated a significantly increased average mean width compared with Clcn3+/+ PMNs (Fig. 3B), although no difference was seen in average maximum length between Clcn3-/- and Clcn3+/+ PMNs (Fig. 3C). Further assessment of cell shape complexity revealed that Clcn3-/- PMNs were less able to undergo shape change from a round, spread configuration, with a significantly lower average percentage of radial deviation (Fig. 3D). In addition, Clcn3-/- PMNs demonstrated less convexity and concavity than Clcn3+/+ PMNs, indicating an overall decrease in cell shape complexity in the absence of ClC-3 (Fig. 3, E and F). As seen in the two-dimensional DIAS-generated difference pictures of a representative Clcn3+/+ PMN (Fig. 3G), normal PMNs elongated and polarized in the direction of the fMLF gradient. During chemotactic migration, major expansion areas (green) protruded toward the fMLF source (56, 88, and 184 s), and the cell exhibited a distinct tapered uropod (small arrows) that retracted between 160 and 180 s (red zone). In contrast, the representative Clcn3-/- cell presented in Fig. 3H was significantly rounder with a greater diameter and lacked a distinct uropod. In addition, expansion zones were distributed randomly around the cell periphery. Considered in combination, these data demonstrated impaired PMN shape change during chemotaxis with decreased elongation and retraction in the absence of ClC-3.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of ClC-3 on murine PMN elongation in response to an fMLF spatial gradient using the DIAS chemotaxis assay. Murine PMNs were stimulated with an fMLF spatial gradient generated by a 500 μm fMLF peak concentration using the Zigmond chamber. Clcn3-/- PMNs demonstrated a significant increase in average percentage of cell roundness (A) and in average mean cell width (B) as compared with Clcn3+/+. C, no difference was seen in average maximum cell length between Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3-/- PMNs. D-F, Clcn3-/- PMNs demonstrated a significant decrease in average percentage of radial deviation, convexity, and concavity compared with Clcn3+/+. G and H, two-dimensional DIAS difference pictures generated at 8-s intervals for a representative Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3-/- cell, respectively. The large arrow at the top of each panel points toward the fMLF source in the chamber, and small arrows in G indicate the uropod (tail) in the Clcn3+/+ cell. Expansion zones are green, retraction zones are red, and common areas in the overlay are gray. *, p ≤ 0.05. n = 4 experiments, at least 50 cells/condition.

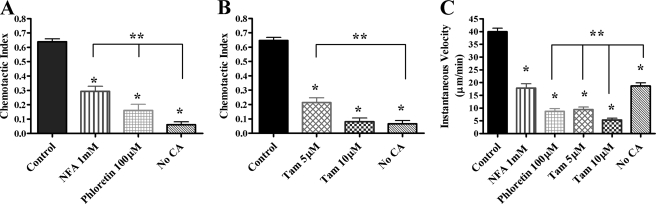

Anion Transporter Inhibition Decreased Human PMN Chemotaxis—Given the novel finding that ClC-3 was required for normal chemotaxis and shape change in murine PMNs, we assessed the role of ClC-3 in human PMN motility, since murine PMN chemotaxis does not perfectly parallel that of human PMNs. To evaluate the effect of anion transporter inhibition on human PMN chemotaxis, PMNs were assessed using the EZ-TAXIScan™ system. Untreated control PMNs and DMSO-treated vehicle control PMNs showed no difference in chemotaxis, as measured by CI (n = 5; data not shown). As we have previously reported, NFA (1 mm) significantly inhibits ClC-3 current in HEK293 cells treated with an adenoviral ClC-3 overexpression system (17). Chemotaxis of human PMNs treated with 1 mm NFA was markedly reduced (CI 0.29 ± 0.04, n = 6) compared with control PMNs (CI 0.64 ± 0.02, n = 11) (Fig. 4A). Since there are no specific blockers of ClC-3, we also evaluated chemotaxis in PMNs treated with another anion transporter inhibitor known to inhibit ClC-3 function, phloretin. In HEK293 cells, phloretin inhibits ClC-3 function by ∼89% (15). Phloretin-treated PMNs demonstrated a significantly impaired chemotactic response (CI 0.16 ± 0.04, n = 5), similar to that of NFA-treated PMNs. There was no effect of phloretin treatment on cell viability, as assessed by trypan blue exclusion. We have previously shown similar data for NFA treatment (1). Given our finding that ClC-3-deficient murine PMNs required a higher fMLF spatial gradient for optimal chemotaxis, we evaluated the chemotactic response of NFA-treated PMNs to a range of fMLF loading concentrations (10 μm, 1 μm, and 100 nm fMLF). Human PMNs treated with NFA demonstrated complete impairment in chemotaxis rather than a shift in the CA concentration response curve (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Effect of anion transporter inhibition on human PMN chemotactic index and velocity in response to fMLF spatial gradient using the EZ-TAXIScan™ chemotaxis assay. Human PMNs were stimulated with an optimal fMLF spatial gradient generated by a 1 μm fMLF loading concentration using the EZ-TAXIScan™ chamber. A, PMNs treated with NFA and phloretin had a significantly decreased average chemotactic index compared with control PMNs. *, p ≤ 0.05 (control, n = 11; NFA, n = 6; phloretin, n = 5 experiments; 50-110 cells/condition). PMNs treated with NFA and phloretin had significantly higher average chemotactic indices than unstimulated PMNs (No CA). **, p ≤ 0.05. B, PMNs treated with tamoxifen (10 μm) had a significantly decreased average chemotactic index compared with control PMNs. Tamoxifen (5 μm) had an intermediate effect on chemotaxis; *, p ≤ 0.05, n = 9 experiments, at least 90 cells/condition. PMNs treated with tamoxifen (5 μm) had significantly higher average chemotactic indices than unstimulated PMNs (No CA); **, p ≤ 0.05. C, PMNs treated with NFA, phloretin, and tamoxifen had significantly diminished average instantaneous velocity compared with control PMNs; *, p ≤ 0.05. The instantaneous velocity of the treated cells was similar to (NFA) or less than that of unstimulated PMNs (No CA); **, p ≤ 0.05.

We recognized that NFA and phloretin are nonspecific anion transporter inhibitors, with known inhibitory effects on both ClC-3 and IClswell (31, 32). To determine the involvement of IClswell in PMN chemotaxis, we employed tamoxifen, a specific IClswell inhibitor (33). The tamoxifen concentration response curve from 1 to 10 μm correlates tightly with electrophysiological inhibition of IClswell, and this inhibitor has been shown to have no effect on other anion transporters (34). Pertinent to the current study, we recently demonstrated that tamoxifen has no effect on ClC-3 current in HEK293 cells overexpressing ClC-3 (15). Tamoxifen treatment had a significant, concentration-dependent, inhibitory effect on PMN chemotaxis. At 5 μm, tamoxifen significantly impaired PMN chemotaxis, whereas at 10 μm, tamoxifen completely inhibited chemotaxis (CI 0.08 ± 0.03, n = 9) compared with control PMNs (CI 0.65 ± 0.02, n = 9) (Fig. 4B). Treatment with 1 μm tamoxifen caused no impairment in PMN chemotaxis (data not shown). To control for the well characterized effects of tamoxifen on estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ), PMN chemotaxis was assessed in the presence of ICI 182,780, a pure estrogen receptor antagonist. ICI 182,780 (1 μm), a concentration that should completely impair PMN estrogen receptor function (35), had no effect on PMN chemotaxis compared with control PMNs (n = 3; data not shown). Following 10 μm tamoxifen treatment, visual evidence of active membrane ruffling and previously reported viability testing with propidium iodide staining (1) indicated that PMNs were viable and intact but unable to change shape or undergo normal movement in response to fMLF. If the decrease in directed movement toward fMLF in tamoxifen-treated PMNs were due exclusively to an inability to sense the CA gradient, we would have expected to see random movement with a chemotactic index near zero. However, compared with unstimulated PMN (no CA), PMNs treated with anion transporter inhibitors had significantly greater chemotaxis than control PMNs moving in the absence of an fMLF spatial gradient. These results suggested that PMNs treated with anion transporter inhibitors were able to sense CA gradients but were unable to move normally in response to fMLF.

Anion Transporter Inhibition Decreased Human PMN Cell Velocity—To further define the nature of the chemotactic defect noted in PMNs treated with NFA, phloretin, or tamoxifen, we evaluated PMN average instantaneous velocity during chemotaxis. All of these agents caused significant decreases in PMN velocity. Compared with control PMN (40.0 ± 1.4 μm/min), both 1 mm NFA and 100 μm phloretin treatment significantly reduced PMN velocity (17.8 ± 1.7 and 8.7 ± 1.1 μm/min, respectively). Treatment with 5 and 10 μm tamoxifen caused a concentration-dependent reduction in cell velocity (9.4 ± 1.0 and 5.3 ± 0.7 μm/min, respectively) (Fig. 4C). Cells undergoing random movement, unstimulated by fMLF, had an intermediate average instantaneous velocity of 18.7 ± 1.2 μm/min. Taken together, the impairments in chemotactic index and velocity suggested that anion transporter inhibition, particularly inhibition of IClswell, caused a defect in cell movement, but not in CA gradient sensing. We hypothesized that IClswell may be required for control of the surface membrane to cytoplasmic volume ratio following CA stimulation. If cell volume regulation is required during PMN chemotaxis, the transition of PMNs from a spherical to elongated shape in response to fMLF would be impaired by IClswell inhibition.

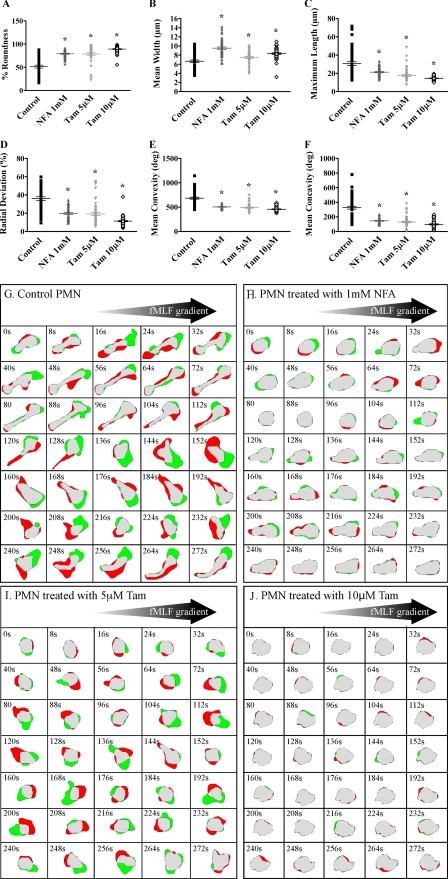

Anion Transporter Inhibition Impaired PMN Elongation and Retraction—To evaluate the effect of anion transporter inhibition on the ability of human PMN to change shape, we employed the Zigmond chemotaxis chamber and two-dimensional DIAS single-cell analysis software, as described above. The basic motile behavior of normal human PMNs had been described using this assay, and the optimal fMLF concentration (500 nm) had been determined previously (23, 36). Overall cell shape was analyzed as the average percentage of roundness. During the 15-min observation periods, DMSO-treated control PMNs were able to elongate and retract rapidly, whereas treatment with 1 mm NFA, 5 μm tamoxifen, or 10 μm tamoxifen impaired shape change significantly, from 51.4% roundness in control PMN to 79.1, 78.5, and 89.2% roundness, respectively (Fig. 5A). Compared with control PMNs, treatment with 1 mm NFA caused a 42% increase in mean width (from 6.7 ± 0.3 to 9.5 ± 0.3 μm) and a 31% reduction in maximum length (from 30.7 ± 2.0 to 21.3 ± 0.7 μm) during chemotaxis (Fig. 5, B and C). Complete inhibition of IClswell with 10 μm tamoxifen caused the most profound changes in PMN shape parameters, with a 24% increase in mean width (from 6.7 ± 0.3 to 8.3 ± 0.2 μm) and a 53% reduction in maximum length (from 30.7 ± 2.0 to 14.5 ± 0.3 μm). PMNs treated with anion transporter inhibitors demonstrated significantly decreased average percentage radial deviation compared with control PMNs (Fig. 5D) as well as significantly diminished convexity and concavity in response to fMLF (Fig. 5, E and F). PMNs with impaired anion transporter function were unable to move out of a round, spread morphology during the response to fMLF, as seen in murine ClC-3-deficient PMNs. The shape anomalies in NFA- and tamoxifen-treated cells during migration in a fMLF gradient were evident in the two-dimensional DIAS difference pictures showing a representative control PMN, a 1 mm NFA-treated PMN, a 5 μm tamoxifen-treated PMN, and a 10 μm tamoxifen-treated PMN, respectively (Fig. 5, G-J). Similar to the wild-type Clcn3+/+ murine PMN presented in Fig. 3G, the control human PMN in Fig. 5G cycled through phases of elongation (48-112 s) and rounder morphology (200 s) as it retracted the uropod. It is also evident that the majority of the control PMN expansion (green) was in the direction of the fMLF source. Transitions between elongate and round morphology were considerably less pronounced in the treated cells. Expansion toward the CA source and uropod retraction was significantly reduced in the NFA-treated cell (Fig. 5H), was more random in the 5 μm tamoxifen-treated PMN (Fig. 5I) and was almost absent in the 10 μm tamoxifen-treated cell (Fig. 5J). Tamoxifen treatment again exhibited a concentration-dependent response consistent with the expected inhibition of IClswell.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of anion transporter inhibitors on human PMN elongation in response to fMLF spatial gradient using the DIAS chemotaxis assay. Human PMNs were stimulated with an optimal fMLF spatial gradient generated by a 500 nm fMLF peak concentration using the Zigmond chamber. A, PMNs treated with NFA and tamoxifen had a significantly increased average percentage of roundness compared with control cells, sham-treated with DMSO. PMNs treated with NFA and tamoxifen demonstrated an increase in average mean cell width (B) and a significantly reduced average maximum cell length (C) as compared with control cells. D-F, PMNs treated with NFA and tamoxifen demonstrated a significant decrease in average percentage of radial deviation, convexity, and concavity compared with control cells. G-J, two-dimensional DIAS difference pictures generated at 8-s intervals for representative control and NFA- and tamoxifen-treated cells as described for Fig. 3; *, p ≤ 0.05, n = 3 experiments, at least 50 cells/condition.

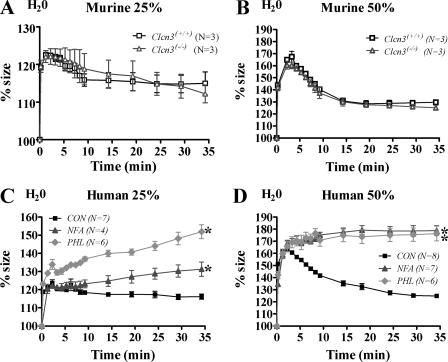

Absence of ClC-3 Had No Effect on PMN Cell Volume Response to Hypotonic Challenge—Given the finding that ClC-3 was required for normal cell shape change during chemotaxis and given the prior controversy over the relationship of ClC-3 to IClswell (37, 38), we investigated the RVD in response to hypotonic challenge in ClC-3-deficient PMNs. Complementary assays were performed using Coulter counter and flow cytometry techniques to assess a change in mean cell volume in response to hypotonic challenge. Base-line mean cell volume measurements were obtained on Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3-/- PMNs, and then cells were subjected to 25 or 50% hypotonic challenge with the addition of water. Murine PMNs underwent an expected RVD, similar to that of earlier studies done by Downey et al. (39) on human PMNs. No difference was seen in the RVD between Clcn3-/- and Clcn3+/+ PMNs (Fig. 6, A and B). Human PMNs treated with NFA and phloretin demonstrated a different phenotype in response to hypotonic challenge than the murine ClC-3 deficient PMNs. NFA- and phloretin-treated PMNs showed significantly impaired RVD, with continued swelling at 20 and 30 min (Fig. 6, C and D), and a percentage of these cells could not be accounted for, presumably secondary to cell lysis. Whereas all tamoxifen-treated PMNs subjected to hypotonic challenge undergo immediate cell lysis (1), NFA and phloretin only partially impaired the RVD. Flow cytometry FSC measurements of both murine and human PMNs recapitulated our findings on the RVD response to 25% hypotonic challenge, with no difference in RVD between Clcn3-/- and Clcn3+/+ PMNs and a 50% return toward base line from peak cell volume by 30 min in murine and control human PMNs. As seen with the Coulter counter assay, NFA-treated PMNs demonstrated a significant impairment in RVD by flow cytometry and continued swelling compared with DMSO-treated control PMNs (n = 5, p < 0.05) (data not shown).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of ClC-3 on murine and human PMN response to 25 and 50% hypotonic challenge using mean cell volume measured by a Coulter counter. Following base-line measurements in isotonic buffer, PMNs were subjected to hypotonic challenge with sterile water at 25 or 50% of the final volume. Control cells rapidly swelled to maximal size by 2.25 min post-treatment, followed by an RVD. Percentage size represents mean cell volume in femtoliters normalized to base line. A and B, no difference was seen in the RVD in response to 25 and 50% hypotonic challenge between Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3-/- PMNs; n = 3. C and D, although DMSO-treated control PMNs demonstrated a return toward base line in response to 25 and 50% hypotonic challenge, NFA- and phloretin-treated PMNs had an abnormal RVD and continued to swell, with significantly different percentage size curves over time compared with control PMNs; *, p ≤ 0.05, n = 4-8.

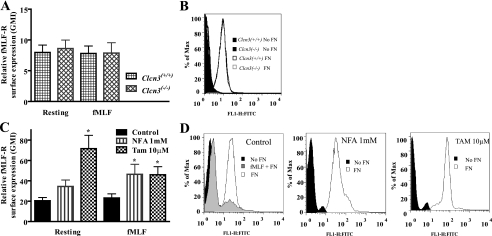

fMLF Receptor Surface Expression in Murine and Human PMN—Since we saw no difference in the RVD between Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3-/- PMNs, indicating that the IClswell response to hypotonic challenge was intact in these cells, we reasoned that the impairment in chemotactic index, velocity, and shape change after simulation with fMLF might be due to a defect in surface expression of the fMLF receptor (fMLF-R). In resting PMNs, direct analysis of fMLF-R using immunoblotting techniques has been difficult (29, 40, 41). We elected to use the FITC-conjugated fMLF-R ligand, FITC-FNLPNTL, to assess fMLF-R surface expression (42). Base-line surface expression of fMLF-R was assessed in resting and fMLF-stimulated murine and human PMNs by FACS. Ionomycin treatment was performed as a positive control, since this has been shown to enhance fMLF-R surface expression (41), and ionomycin caused an increase in FITC signal in human PMNs (data not shown). No significant difference was seen in fMLF-R surface expression between Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3-/- PMNs at rest or after a 15-min treatment with 100 nm fMLF (Fig. 7A). Human PMNs treated with NFA and tamoxifen demonstrated increased fMLF-R surface expression relative to DMSO-treated control PMNs at rest and following fMLF stimulation (Fig. 7C). FITC signal could be partially competed away through pretreatment with unconjugated fMLF, as shown in the representative histogram (Fig. 7D). These results do not preclude a defect in the intracellular signaling response to fMLF but do indicate that the impairment in chemotaxis seen with anion transporter inhibition was not due to a decrease in fMLF-R surface expression.

FIGURE 7.

Murine and human PMN surface expression of fMLF-R measured by flow cytometry using the FITC-conjugated fMLF-R ligand, FITC-FNLPNTL. A, no difference in fMLF-R surface expression was seen between resting Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3-/- PMNs or between Clcn3+/+ and Clcn3-/- PMNs stimulated with fMLF (100 nm) to simulate chemotaxis treatment conditions, n = 6. B, representative histogram of resting fMLF-R surface expression by FITC-conjugated fMLF-R ligand, showing FITC-FNLPNTL-stained (FN) versus unstained (No FN) murine PMNs. C, tamoxifen treatment enhanced fMLF-R surface expression in resting PMNs. fMLF-stimulated PMNs treated with NFA and tamoxifen demonstrated an increase in fMLF-R surface expression compared with DMSO-treated control PMNs; *, p ≤ 0.05, n = 7. D, representative histogram of resting fMLF-R surface expression by FITC-conjugated fMLF-R ligand, FITC-FNLPNTL-stained (FN) versus unstained (No FN) human PMNs. FITC-FNLPNTL staining was partially competed away by pretreatment with fMLF to block receptor-ligand interactions.

DISCUSSION

Normal PMN chemotaxis is one of the essential functions of an intact host defense system. The current investigation is the first to study the role of the anion transporters, ClC-3 and IClswell, in PMN chemotaxis and suggests two novel findings. First, the absence of ClC-3 is associated with significantly impaired chemotaxis and cell shape change in response to fMLF, using murine ClC-3-deficient PMNs. Second, IClswell is essential for chemotaxis and shape change in human PMNs.

Four key findings were observed in our chemotaxis studies on ClC-3-deficient PMNs compared with wild type control PMNs: 1) a decrease in peak chemotaxis; 2) a decrease in average PMN velocity; 3) an alteration in cell shape change during chemotaxis with impaired elongation and retraction; and 4) a population-based impairment in the percentage of motile cells. Morphology differences in the absence of ClC-3 function included increased cell roundness and decreased percentage of radial deviation, concavity, and convexity. Taken together, our analyses indicate that, compared with Clcn3+/+ PMNs, Clcn3-/- PMNs do not undergo normal chemotactic movement cycles. If ClC-3 affected only cell elongation during motility, we would have expected to see impaired cell shape change but an intact directional response to the fMLF spatial gradient. Our results indicate that the absence of ClC-3 not only impaired cell shape change but also altered the PMN chemotactic response to fMLF, as measured by the chemotactic index. One potential mechanism to explain the 10-fold shift in peak chemotaxis seen in Clcn3-/- PMNs involves failure to mobilize the fMLF-R to the cell surface in response to the CA signal. Our studies showed similar levels of fMLF-R surface expression in Clcn3-/- PMNs compared with Clcn3+/+ PMNs at rest and in response to fMLF stimulation, indicating that a difference in fMLF-R expression was not the cause of impaired chemotaxis in ClC-3-deficient PMNs. These results led us to speculate that ClC-3 was involved both in chemotaxis signaling and in cell shape change during chemotaxis.

After finding these abnormalities in ClC-3-deficient PMN chemotaxis, human PMN chemotaxis was studied using anion transporter inhibitors. We noted differences between ClC-3-deficient murine PMNs and human PMNs treated with anion transporter inhibitors. Most notably, Clcn3-/- PMNs displayed a concentration response to fMLF, whereas NFA- and phloretin-treated human PMNs were unable to respond well to any of the fMLF gradients tested. The intensified phenotypes suggested that NFA and phloretin caused a more severe inhibition of cell motility than that seen in the absence of ClC-3, potentially through inhibition of another anion transporter involved in PMN motility (i.e. IClswell).

Using a specific inhibitor of IClswell that does not affect ClC-3 (15), we obtained direct evidence that IClswell is required for normal PMN shape change during chemotaxis. The most likely mechanism for the effect of IClswell on chemotaxis is through cell volume regulation at the whole cell or local membrane level. Inhibition of IClswell has been shown to impair cell motility in other cell types, most notably in monocytes (43), nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells (44), and malignant glioma cells (45, 46). Our findings are also consistent with the Schwab ion transport model, in which NaCl movement and water influx at the leading edge contribute to projection of the cell pseudopod in transformed renal epithelial (MDCK-F) cells. In this model, a functional RVD is required for uropod shrinkage and support of myosin retraction processes necessary for efficient directional movement (5). PMNs with partial or complete inhibition of IClswell demonstrated impaired elongation and retraction. At this time, the molecular identity of the IClswell conductance is unknown, and its cellular localization has not been defined. Future studies are needed to establish a potential link between pseudopod extension/uropod retraction and IClswell function during PMN chemotaxis.

The biophysical nature of ClC-3 and its relationship to the IClswell have been controversial. It was proposed that ClC-3 is a swelling-induced chloride conductance in NIH/3T3 cells stably transfected with ClC-3 cDNA (37). In addition, anti-ClC-3 antibodies and ClC-3 RNA interference strategies elicit impaired IClswell activity in several cell types (38, 47). However, the overexpression or absence of ClC-3 has no impact on the RVD in multiple cell types, including neurons (48), cardiac myocytes (38), and epithelial cells (49), indicating that ClC-3 is not IClswell (50, 51). Most recently, Picollo and Pusch (52) reported that ClC-4 and -5, proteins in a subbranch of the ClC (chloride channel) gene superfamily that have 90% sequence homology to ClC-3, are in fact chloride/proton antiporters (52, 53). We demonstrated that ClC-3 overexpression produces a pH-dependent current similar to that of ClC-4 and ClC-5, providing strong support for the notion that ClC-3 is also a Cl-/H+ antiporter (15). ClC-3 current is readily distinguishable from IClswell in these studies.

Since ClC-3 is not the IClswell, the impairment in chemotaxis and shape change seen with inhibition of ClC-3 and IClswell are distinct effects. The mechanism whereby IClswell blockade impaired PMN chemotaxis was clear from our data; PMNs were unable to elongate and retract normally, presumably due to an inability to regulate the cell volume changes that accompany chemotaxis. The mechanism whereby ClC-3 affects PMN elongation and retraction is less clear. We have previously demonstrated that ClC-3 is involved in regulation of the PMN NADPH oxidase (Nox2). ClC-3-deficient PMNs produce significantly less Nox2-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) than litter-mate control PMNs during phagocytosis (1) and during endotoxin-mediated PMN priming (17). In addition, we have shown in vascular smooth muscle cells that Nox1-derived ROS generation and hydrogen peroxide production are impaired in the absence of ClC-3 (16). Furthermore, multiple laboratories have shown that the IClswell conductance is regulated by stimuli other than hypotonic challenge, including cytokines and ROS. Hydrogen peroxide directly activates IClswell current in two epithelial cell lines (49) and is associated with angiotensin-II activation of IClswell in cardiac ventricular myocytes (54). We have observed activation of IClswell in vascular smooth muscle cells by the cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α. This effect was dependent on hydrogen peroxide production, since it was blocked by catalase.3 We speculate that a regulatory link between ClC-3 and IClswell could occur through ROS signaling downstream of the fMLF-R and might explain the impairment in IClswell conductance seen in some cell types in the absence of ClC-3 (15).

As we and others have shown, PMNs generate low levels of intracellular ROS following stimulation with fMLF (17, 55, 56) that would be predicted to activate the IClswell independent of volume changes. As has been shown in other cell types (49, 50), ClC-3-deficient PMNs had no diminution in the RVD following hypotonic challenge, indicating that this aspect of cell volume regulation and IClswell function is intact in Clcn3-/- PMNs. We postulate that ClC-3 modulates Nox2-derived intracellular ROS levels that control IClswell activation through a mechanism distinct from that of hypotonic challenge. Following fMLF stimulation in this model, chloride efflux via IClswell would be impaired in PMNs deficient in ClC-3 function, but the response to hypotonic challenge would be intact, consistent with our findings. Further studies are needed to confirm a direct relationship between ClC-3 and IClswell function during PMN chemotaxis.

Several potential limitations to our study could confound our understanding of the role of ClC-3 in PMN chemotaxis. 1) We recognize that the absence of ClC-3 in murine PMN may alter expression of other cellular components important for motility and shape change. In the absence of ClC-3, bone marrow-derived PMNs may have impaired differentiation that might also alter expression of proteins required for PMN chemotaxis in the Clcn3-/- cells. Either of these processes might lead us to attribute the observed chemotactic defect in Clcn3-/- PMNs to ClC-3 function by mistake. 2) A defect in exocytosis or membrane recycling in PMNs lacking ClC-3 could also explain the impairment of shape change seen in response to fMLF, and this remains to be investigated. 3) The absence of a selective ClC-3 inhibitor impairs our ability to define the role of ClC-3 in human PMNs.

We have defined the contribution of two distinct anion transporters to PMN chemotaxis and shape change. ClC-3 is required for normal PMN chemotaxis and morphology changes in response to fMLF. In addition, the swelling-induced chloride conductance is required for cell elongation and retraction during PMN chemotaxis. The absence of ClC-3 has no effect on cell volume regulation in response to hypotonic challenge. We speculate that ClC-3 functions as an indirect regulator of IClswell. The fact that PMNs lacking ClC-3 function had an altered fMLF concentration response indicates that ClC-3 may play a proximal role in chemotaxis signaling. We speculate that the requirement for ClC-3 in chemotaxis signaling may be mediated by its obligatory role in activation of Nox2 in intracellular vesicles.

Our investigation is among the first to establish a role for the anion transporters ClC-3 and IClswell in PMN motility and chemotaxis. Although our primary goal with this work is to understand the role of anion transporters in neutrophil chemotaxis, the results of this study have implications beyond host defense. Understanding the basic mechanisms involved in PMN shape change and chemotaxis will inform our understanding of cell motility in general and will provide insight for new investigations into such diverse disease processes as wound healing (57), inflammation (1, 43), and cancer metastasis (44, 45).

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Kuhl, W. B. Mosher, M. Bailey, G. Bailey, J. Hook, and N. Davis for technical assistance and support. We acknowledge the use of the W. M. Keck Dynamic Image Analysis Facility at the University of Iowa.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HD-041922 and HD-047349 (to A. P. D. V.), HD-18577 (to D. R. S.), AI-34879 (to W. M. N.), HL-62483 (to F. S. L.), and AI-067533 and AI-073872 (to J. G. M.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocyte; CA, chemoattractant; RVD, regulatory volume decrease; fMLF, formyl-Met-Leu-Phe; fMLF-R, formyl-Met-Leu-Phe receptor; NFA, niflumic acid; ROS, reactive oxygen species; DIAS, dynamic imaging analysis software; HBSS, Hanks' buffered saline solution; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; CI, chemotactic index; FSC, forward scatter contour(s).

J. J. Matsuda, M. S. Filali, K. A. Volk, and F. S. Lamb, unpublished observations (presented in abstract form in Ref. 58).

References

- 1.Moreland, J. G., Davis, A. P., Bailey, G., Nauseef, W. M., and Lamb, F. S. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 28112277 -12288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cicchetti, G., Allen, P. G., and Glogauer, M. (2002) Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 13 220-228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parent, C. A. (2004) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 164 -13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kay, R. R., Langridge, P., Traynor, D., and Hoeller, O. (2008) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9 455-463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwab, A. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 280F739 -F747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosengren, S., Henson, P. M., and Worthen, G. S. (1994) Am. J. Physiol. 267C1623 -1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lang, F., Busch, G. L., and Volkl, H. (1998) Cell Physiol. Biochem. 8 1-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simchowitz, L., Textor, J. A., and Cragoe, E. J., Jr. (1993) Am. J. Physiol. 265C143 -C155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoddard, J. S., Steinbach, J. H., and Simchowitz, L. (1993) Am. J. Physiol. 265C156 -C165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cala, A. (1990) Chloride channels and carriers in nerve, muscle and glioma cells, Plenium Press, New York

- 11.Simchowitz, L., and De Weer, P. (1986) J. Gen. Physiol. 88167 -194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimizu, Y., Daniels, R. H., Elmore, M. A., Finnen, M. J., Hill, M. E., and Lackie, J. M. (1993) Biochem. Pharmacol. 451743 -1751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krause, K. H., and Welsh, M. J. (1990) The Journal of clinical investigation 85 491-498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simchowitz, L., Textor, J. A., and Vogt, S. K. (1991) Am. J. Physiol. 261C906 -C915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuda, J. J., Filali, M. S., Volk, K. A., Collins, M. M., Moreland, J. G., and Lamb, F. S. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 294C251 -C262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller, F. J., Jr., Filali, M., Huss, G. J., Stanic, B., Chamseddine, A., Barna, T. J., and Lamb, F. S. (2007) Circ. Res. 101663 -671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreland, J. G., Davis, A. P., Matsuda, J. J., Hook, J. S., Bailey, G., Nauseef, W. M., and Lamb, F. S. (2007) J. Biol. Chem.

- 18.Dickerson, L. W., Bonthius, D. J., Schutte, B. C., Yang, B., Barna, T. J., Bailey, M. C., Nehrke, K., Williamson, R. A., and Lamb, F. S. (2002) Brain Res. 958227 -250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, S., Yamauchi, A., Marchal, C. C., Molitoris, J. K., Quilliam, L. A., and Dinauer, M. C. (2002) J. Immunol. 1695043 -5051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lavigne, M. C., Murphy, P. M., Leto, T. L., and Gao, J. L. (2002) Cellular immunology 218 7-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mestas, J., and Hughes, C. C. (2004) J. Immunol. 1722731 -2738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanegasaki, S., Nomura, Y., Nitta, N., Akiyama, S., Tamatani, T., Goshoh, Y., Yoshida, T., Sato, T., and Kikuchi, Y. (2003) J. Immunol. Methods 2821 -11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geiger, J., Wessels, D., and Soll, D. R. (2003) Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 56 27-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varnum, B., and Soll, D. R. (1984) J. Cell Biol. 991151 -1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zigmond, S. H. (1977) J. Cell Biol. 75606 -616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soll, D. R. (1995) Int. Rev. Cytol. 16343 -104 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wessels, D., Voss, E., Von Bergen, N., Burns, R., Stites, J., and Soll, D. R. (1998) Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 41225 -246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soll, D. R., Voss, E., Varnum-Finney, B., and Wessels, D. (1988) J. Cell Biochem. 37 177-192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu, L., Harbecke, O., Elwing, H., Follin, P., Karlsson, A., and Dahlgren, C. (1998) J. Immunol. 1602463 -2468 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugawara, T., Miyamoto, M., Takayama, S., and Kato, M. (1995) J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 33 91-100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nobles, M., Higgins, C. F., and Sardini, A. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 287C1426 -C1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly, M., Dixon, S., and Sims, S. (1994) J. Physiol. (Lond) 475377 -389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valverde, M. A., Mintenig, G. M., and Sepulveda, F. V. (1993) Pflugers Arch. 425552 -554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greenwood, I. A., and Large, W. A. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. 275H1524 -H1532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia-Duran, M., de Frutos, T., Diaz-Recasens, J., Garcia-Galvez, G., Jimenez, A., Monton, M., Farre, J., Sanchez de Miguel, L., Gonzalez-Fernandez, F., Arriero, M. D., Rico, L., Garcia, R., Casado, S., and Lopez-Farre, A. (1999) Circ. Res. 851020 -1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stepanovic, V., Wessels, D., Goldman, F. D., Geiger, J., and Soll, D. R. (2004) Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 57 158-174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duan, D., Winter, C., Cowley, S., Hume, J. R., and Horowitz, B. (1997) Nature 390417 -421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, J., Xu, H., Morishima, S., Tanabe, S., Jishage, K., Uchida, S., Sasaki, S., Okada, Y., and Shimizu, T. (2005) Jpn. J. Physiol. 55379 -383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Downey, G. P., Grinstein, S., Sue, A. Q. A., Czaban, B., and Chan, C. K. (1995) J. Cell Physiol. 163 96-104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borregaard, N., Lollike, K., Kjeldsen, L., Sengelov, H., Bastholm, L., Nielsen, M. H., and Bainton, D. F. (1993) Eur. J. Haematol. 51187 -198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lala, A., Sojar, H. T., and De Nardin, E. (1997) Biochem. Pharmacol. 54381 -390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sengelov, H., Kjeldsen, L., and Borregaard, N. (1993) J. Immunol. 1501535 -1543 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim, M. J., Cheng, G., and Agrawal, D. K. (2004) Clin. Exp. Immunol. 138453 -459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mao, J., Wang, L., Fan, A., Wang, J., Xu, B., Jacob, T. J., and Chen, L. (2007) Cell Physiol. Biochem. 19 249-258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soroceanu, L., Manning, T. J., Jr., and Sontheimer, H. (1999) J. Neurosci. 195942 -5954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ransom, C. B., O'Neal, J. T., and Sontheimer, H. (2001) J. Neurosci. 217674 -7683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hermoso, M., Satterwhite, C. M., Andrade, Y. N., Hidalgo, J., Wilson, S. M., Horowitz, B., and Hume, J. R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 27740066 -40074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stobrawa, S. M., Breiderhoff, T., Takamori, S., Engel, D., Schweizer, M., Zdebik, A. A., Bosl, M. R., Ruether, K., Jahn, H., Draguhn, A., Jahn, R., and Jentsch, T. J. (2001) Neuron 29185 -196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Varela, D., Simon, F., Riveros, A., Jorgensen, F., and Stutzin, A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 27913301 -13304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang, P., Liu, J., Di, A., Robinson, N. C., Musch, M. W., Kaetzel, M. A., and Nelson, D. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 27620093 -20100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weylandt, K. H., Valverde, M. A., Nobles, M., Raguz, S., Amey, J. S., Diaz, M., Nastrucci, C., Higgins, C. F., and Sardini, A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 27617461 -17467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Picollo, A., and Pusch, M. (2005) Nature 436420 -423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scheel, O., Zdebik, A. A., Lourdel, S., and Jentsch, T. J. (2005) Nature 436424 -427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Browe, D. M., and Baumgarten, C. M. (2004) J. Gen. Physiol. 124273 -287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hayashi, H., Aharonovitz, O., Alexander, R. T., Touret, N., Furuya, W., Orlowski, J., and Grinstein, S. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 294C526 -C534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Demaurex, N., Downey, G. P., Waddell, T. K., and Grinstein, S. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 1331391 -1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kirsner, R. S., and Eaglstein, W. H. (1993) Dermatol. Clin. 11629 -640 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matsuda, J. J., Filali, M. S., Volk, K. A., and Lamb, F. S. (2008) FASEB J. 22 937.18 [Google Scholar]