Abstract

The human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) tegument protein pp71, encoded by gene UL82, stimulates viral immediate-early (IE) transcription. pp71 interacts with the cellular protein hDaxx at nuclear domain 10 (ND10) sites, resulting in the reversal of hDaxx-mediated repression of viral transcription. We demonstrate that pp71 displaces an hDaxx-binding protein, ATRX, from ND10 prior to any detectable effects on hDaxx itself and that this event contributes to the role of pp71 in alleviating repression. Introduction of pp71 into cells by transfection, infection with a pp71-expressing herpes simplex virus type 1 vector, or by generation of transformed cell lines promoted the rapid relocation of ATRX from ND10 to the nucleoplasm without alteration of hDaxx levels or localization. A pp71 mutant protein unable to interact with hDaxx did not affect the intranuclear distribution of ATRX. Infection with HCMV at a high multiplicity of infection resulted in rapid displacement of ATRX from ND10, the effect being observed maximally by 2 h after adsorption, whereas infection with the UL82-null HCMV mutant ADsubUL82 did not affect ATRX localization even at 7 h postinfection. Cell lines depleted of ATRX by transduction with shRNA-expressing lentiviruses supported increased IE gene expression and virus replication after infection with ADsubUL82, demonstrating that ATRX has a role in repressing IE transcription. The results show that ATRX, in addition to hDaxx, is a component of cellular intrinsic defenses that limit HCMV IE transcription and that displacement of ATRX from ND10 by pp71 is important for the efficient initiation of viral gene expression.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is an important human pathogen. It is a major cause of fetal damage, organ transplant rejection, and disease in immunocompromised individuals. The HCMV genome encodes approximately 165 proteins that are synthesized in a coordinated manner, in which immediate-early (IE) genes are transcribed prior to early and late genes (11). IE gene expression is controlled by a complex DNA element, the major immediate-early promoter (MIEP), which contains multiple sequence motifs that constitute binding sites for cellular proteins that regulate transcription, both positively and negatively. An additional level of regulation is provided by the tegument phosphoprotein pp71, encoded by gene UL82. This protein activates expression from the MIEP and other promoters, and the available evidence suggests that pp71 stimulates expression from the entire HCMV genome in addition to its effect on the MIEP (4, 10, 23, 34). An HCMV mutant that lacks UL82 is severely impaired for IE gene expression, especially during infection at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI), demonstrating the functional importance of pp71 for the initiation of HCMV replication (7).

Shortly after infection, pp71 is released from the virion and transported to the nucleus, where it is detected at nuclear domain 10 (ND10) (20, 21, 30). These intranuclear structures contain cellular proteins involved in many functions, including regulation of transcription and gene expression, and they are closely associated with the incoming HCMV genome and the predominant locations of viral IE transcription (26, 36, 48). Many DNA virus genomes are initially found at ND10, and in the case of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) it is clear that the viral DNA forms a template for the assembly of new ND10 structures (15). This rapid cell response appears to represent an intrinsic defense mechanism that is employed against many DNA viruses (55), and viral products synthesized shortly after infection interact with and neutralize the cellular components (12, 13, 18). After infection with HCMV, IE1 protein rapidly associates with ND10 and directs the dissociation of the promyelocytic leukemia (PML) protein, the major ND10 constituent, and other proteins from the structures (1, 2, 29, 30, 58). This effect is a consequence of IE1-mediated removal of covalently attached small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 protein from PML (31, 61).

The cell protein Daxx (or hDaxx as the human form) is an important interaction partner of pp71 and is crucial for localization of the viral protein to ND10 (9, 21, 27, 45). Although hDaxx is present in the cytoplasm, where it has various activities in the regulation of apoptosis, it is also a major component of ND10 (25, 38, 43, 51, 57). Within the nucleus, hDaxx can act as a repressor of gene expression and is thought to form a bridge that targets other chromatin-associated proteins, such as histone deacetylases (HDACs), to relevant promoters (22, 32, 33, 59). Consistent with these findings, hDaxx is an important component of a cellular intrinsic defense that inhibits HCMV IE transcription. Overexpression of hDaxx reduces viral IE gene expression, an effect that can be overcome by inhibition of HDACs (8, 59). Conversely, reduction of hDaxx levels, by use of small interfering RNA, increases IE gene expression and virus replication after infection at a low MOI (8, 56). More dramatically, depleting cells of hDaxx very substantially overcomes the defect in IE gene expression after infection with HCMV UL82-null mutants (8, 45, 56). These observations suggest that pp71 antagonizes a repressive mechanism that requires hDaxx, thereby enabling IE transcription to proceed. This activity of pp71 is thought to depend on proteolytic degradation of hDaxx, through a process that is proteasome dependent but ubiquitin independent (24, 49, 50). Although hDaxx has a central role in repressing HCMV IE gene expression, it would be expected, by analogy with observations in other cellular systems, that additional proteins are important for mediating the repression. A role for HDACs, and consequent modification of chromatin structure, has been suggested by the finding that treatment with the HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A increases IE expression after infection with wild-type HCMV or UL82-null mutants (50, 59).

The study reported here deals with the effects of pp71 on the hDaxx-binding protein ATRX, so named because it is mutated in the X-linked α-thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome (19). This large (ca. 280-kDa) protein has many features that suggest a role in chromatin structure and control of gene expression. It has an ATPase/helicase domain with homology to the SNF2 family of chromatin remodeling proteins, and ATRX has indeed been shown to exhibit ATPase activity and to alter the nucleosomal arrangement on chromatin in vitro (54, 62). The protein also has a zinc-finger domain that is implicated in DNA binding (3). ATRX is found predominantly at ND10 and heterochromatin, and these localizations are dependent upon its interaction with hDaxx (5, 6, 16, 28, 47, 54, 62). The available functional studies, together with the association of ATRX with heterochromatin, suggest that ATRX is involved in repressing gene expression (54). In HeLa cells, most ATRX is complexed with hDaxx, but there remains a pool of hDaxx that is not associated with ATRX (62). No precise function has been demonstrated for ATRX in normal cells, although it has been suggested that its interaction with the methylated CpG-binding protein MeCP2 is important for maintaining chromatin structure (41). We describe here studies showing that pp71 displaces ATRX from ND10 shortly after HCMV infection and that this event is important for viral IE gene expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

Plasmid pCP4241 was constructed by insertion of a cassette consisting of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-tagged pp71 (YFPpp71), derived from plasmid pYFPpp71 (35), plus HCMV MIEP and simian virus 40 polyadenylation signals, into pcDNA5/FRT (Invitrogen). The lentivirus vector expressing a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting ATRX was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Mission-shRNAs) and was named pLKO-shATRX90. The sense-strand oligonucleotide sequence of the shRNA expressed by this plasmid is 5′-CGACAGAAACTAACCCTGTAA-3′. The target site of shATRX90 within the ATRX sequence is shown below in Fig. 1A.

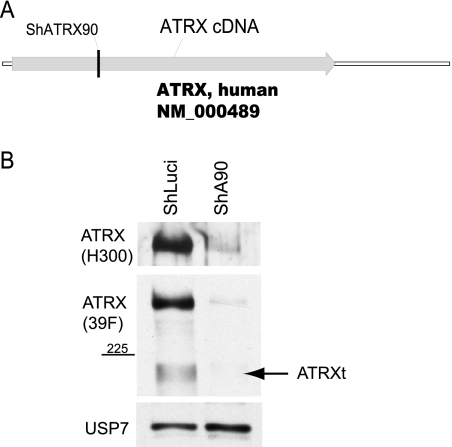

FIG. 1.

ATRX depletion in fibroblasts. The site within the hATRX gene from which the shA90 sequence was derived (A) and the level of depletion determined in a Western blot assay (B) are shown. Anti-ATRX antibodies H300 and 39F, specific for the C terminus or N terminus, respectively, were used. USP7 acted as a loading control.

Cells and viruses.

Human fetal foreskin fibroblasts (HFFF2) were obtained from the European Collection of Cell Cultures. CV-1(F) cells were obtained from Invitrogen. Cell line C4N was produced by transfection of pCP4241 and pOG44, which encodes the Flp recombinase (Invitrogen), into CV-1(F) cells and selection in 200 μg/ml hygromycin. Although this procedure should result in recombination of the transgene into a unique genomic FRT site, in our experience insertions also occurred at other loci. The C4N line fortuitously expressed YFPpp71 at relatively low levels and was viable, whereas other YFPpp71-expressing cell lines usually degenerated during culture. All of the above cells were propagated in Dulbecco's modified Glasgow minimal essential medium supplemented with nonessential amino acids, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and either 10% fetal calf serum or 5% fetal and 5% newborn calf serum. HF human fibroblasts (a gift of Thomas Stamminger, University of Erlangen) and HEK-293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Puromycin was used for selection of lentivirus-transduced cells at 2 μg/ml initially, followed by maintenance of cells at 0.5 μg/ml puromycin.

Wild-type HCMV was strain AD169. HCMV mutant ADsubUL82 and rescuant ADrevUL82 were kindly supplied by T. Shenk (Princeton University) and propagated and quantified as described elsewhere, with amounts of ADsubUL82 expressed as infectious units after complementation with UV-irradiated HCMV (7, 45). HCMV virions were purified from noninfectious enveloped particles and dense bodies by glycerol-tartrate gradient centrifugation, as described previously (53). For UV irradiation, an HCMV stock was diluted 10-fold in medium lacking calf serum and phenol red and subjected to three rounds of irradiation (80 mJ each) in a Stratalinker (Stratagene), with mixing between exposures. After irradiation, fetal calf serum was added to 10%. The UV treatment reduced infectivity by a factor of >105 and IE protein synthesis to below detectable levels.

The HSV-1 mutant in1316 has mutations that inactivate the transcriptional activities of VP16, ICP0, and ICP4 and an insertion encoding YFPpp71, controlled by the HCMV MIEP, at the thymidine kinase locus (35). Derivative in0125, in which the C-terminal 61 amino acids have been removed from the pp71 coding region, and mutant in1360, which encodes untagged pp71, have been described previously (44).

Transfection.

HFFF2 cells were transfected using ExGen 500 (Fermentas Life Sciences), and plasmids were introduced into CV-1(F) cells by using a nucleofector (Amaxa).

Isolation of human fibroblasts depleted of ATRX or hDaxx.

Lentiviral vectors were used to generate cells expressing shRNAs targeting ATRX or hDaxx essentially as described previously (16, 17). Briefly, HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with lentiviral vector pLKO-shATRX90, helper plasmid pCMV.DR8.91, and envelope-expressing plasmid pVSV-G, and cell culture supernatants were harvested 3 days later. HF cells transduced with this vector were named HF-shA90. These cells were checked for ATRX levels and regenerated frequently because of a tendency to recover ATRX expression. HFs depleted of hDaxx were produced by transduction with lentiviruses prepared using plasmid pLKO-shDaxx-2, which expresses an shRNA based on the hDaxx-2 small interfering RNA described previously (39, 45). To produce an shRNA control cell line, plasmid pLKO-shLuci (16, 17) was used to generate the cell line HF-shLuci.

Antibodies.

Rabbit anti-hDaxx antisera were from Upstate, Sigma-Aldrich, or serum r1866 (43). Rabbit anti-ATRX (H-300) was supplied by Santa Cruz Biotechnology, mouse anti-ATRX clone 39F was a gift from Richard Gibbons, University of Oxford, and clone D-5 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Goat anti-ATRX was clone C-16 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Mouse anti-PML clone 5E10 (52) was a gift from Roel van Driel, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and PG-M3 was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Rabbit anti-PML serum was clone H-238 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Mouse monoclonal anti-HCMV IE1 and IE2 (clone E13) was supplied by Serotec Laboratories. HCMV pp65 was detected by use of ab2595 (Abcam). Anti-USP7 (BL851) was obtained from Bethyl Laboratories. Rabbit anti-pp71 was described previously (44). Mouse anti-actin (AL-40) was from Sigma-Aldrich. Secondary antibodies were fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated sheep anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG; Sigma-Aldrich), Cy3- or Cy5-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (GE Healthcare), or Alexa 488-conjugated chicken anti-rabbit, Alexa 555-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit, or Alexa 647-conjugated donkey anti-goat antibody (all from Invitrogen).

Protein blotting.

Protein samples were prepared for blotting and analyzed as described previously (35).

Immunofluorescence.

Coverslips were prepared and analyzed by confocal microscopy as described previously (14). For analysis of intranuclear distributions of ATRX and hDaxx, coverslips were visually scanned systematically, with the microscope set slightly out of focus so that ND10 foci could not be discerned under UV illumination, and images were captured at high resolution after laser excitation.

RESULTS

hDaxx targets ATRX to ND10.

The cell proteins ATRX and hDaxx are located at ND10 structures in many cell types, including human fibroblasts (16, 28, 54, 62), and the two proteins can be isolated in a complex that is thought to affect chromatin structure (54, 62). To investigate the relationship between the two proteins, HFs depleted of ATRX (named HF-shA90) were isolated as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 1A). After puromycin selection and expansion of cell lines, depletion of ATRX was confirmed by Western blotting and immunofluorescence (IF), using antibodies that recognized either the C-terminal (H-300) or N-terminal (39F) portions of the protein (Fig. 1B and 2). Figure 1B demonstrates that shRNA A90 depleted both major and truncated (ATRXt) isoforms of the protein to levels that were barely detectable. IF analysis demonstrated that approximately 90% of the HF-shA90 cells had background levels of ATRX staining compared to the normal punctate ATRX staining pattern, colocalizing with PML (Fig. 2). The control cell line (HF-shLuci) did not show any abnormalities in protein expression or localization of ATRX (Fig. 1B and 2). However, we noted a gradual recovery of ATRX expression during passage of HF-shA90 cells, and therefore they were regenerated on a regular basis.

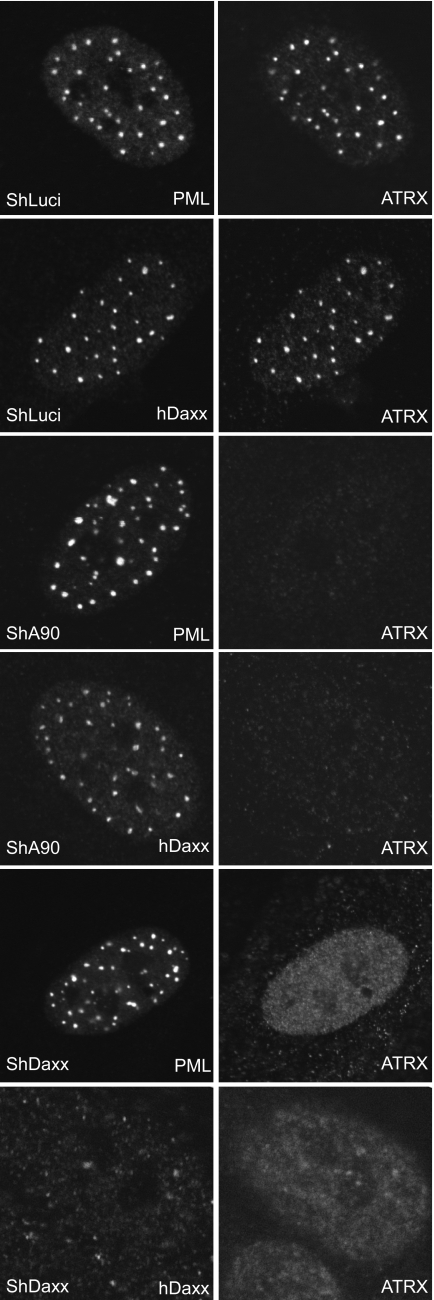

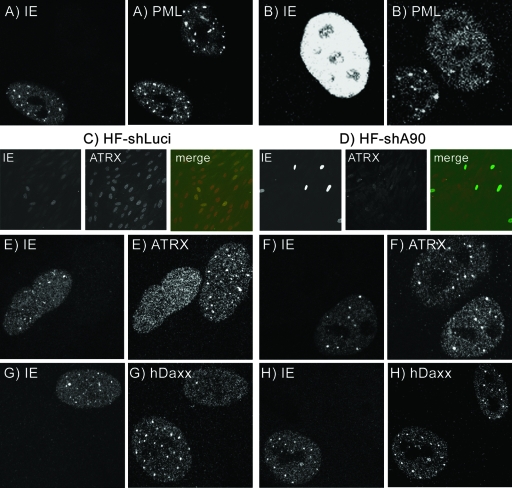

FIG. 2.

Effects of depleting ATRX or hDaxx on the localization of ND10 proteins. Control (ShLuci), ATRX-depleted (ShA90), or hDaxx-depleted (ShDaxx) cell cultures were analyzed by IF, using antibodies specific for PML, ATRX, or hDaxx.

Depletion of ATRX did not affect the location of hDaxx within ND10, since in HF-shA90 cells hDaxx displayed a normal punctate localization (Fig. 2). On the other hand, depletion of hDaxx using a similar approach to generate HF-shDaxx-2 cells resulted in dispersal of ATRX from ND10 such that it adopted an entirely nuclear diffuse staining pattern (Fig. 2). This confirms the conclusion of other studies that the distribution of ATRX is dependent on that of hDaxx (28) and provides support for the hypothesis that ATRX and hDaxx are components of a multiprotein complex (22, 54, 62).

Expression of pp71 results in the dissociation of ATRX from ND10.

To investigate the effects of pp71 on ATRX and hDaxx, HFFF2 monolayers were infected at an MOI of 0.1 with the HSV-1 recombinant in1316. This virus has mutations that inactivate the HSV-1 proteins VP16, ICP0, and ICP4 at 38.5°C and additionally contains an insertion of a gene encoding YFP-tagged pp71 (YFPpp71), controlled by the HCMV MIEP. Multiple mutants of this type enable transgenes to be expressed in human fibroblasts without detectable HSV-1 protein synthesis or cytopathology. At 3 h after infection with in1316, HFFF2 cells expressing YFPpp71 were identified, and at this early time the protein was found to be located exclusively at ND10. In such cells, hDaxx colocalized with YFPpp71 at ND10 (Fig. 3C), but the intranuclear distribution of ATRX was altered. Many YFPpp71-positive cells (ca. 70%) exhibited a dispersed distribution of ATRX with no obvious concentration at ND10 (Fig. 3A), similar to that observed upon depletion of hDaxx (Fig. 2), and in the remainder the foci of ATRX were fainter than in uninfected cells, superimposed on a higher-than-normal background of dispersed signal (Fig. 3B). Cells expressing YFPpp71 showed no observable alteration in the localization of hDaxx at ND10 even when ATRX was fully dispersed, as demonstrated by IF that simultaneously detected YFPpp71, ATRX, and hDaxx (Fig. 3E). Therefore, expression of low levels of YFPpp71 resulted in the release of ATRX from ND10 before any effects on hDaxx were detectable. Longer times of infection resulted in greater production of YFPpp71, and at 7 h postinfection, although most nuclei still exhibited punctate YFPpp71, those with the highest levels showed this protein and hDaxx in a more dispersed distribution (Fig. 3D). To ensure that the YFP tag did not affect the behavior of pp71, analogous experiments were carried out with the HSV-1 recombinant in1360, which expresses authentic pp71. By use of an antibody specific for pp71, it was again found that ATRX was dispersed, or partially dispersed, in HFFF2 cells expressing pp71, whereas hDaxx was colocalized with pp71 in a punctate distribution (Fig. 3F and G). In summary, low levels of YFPpp71 resulted in relocation of ATRX from ND10 before there was any detectable effect on hDaxx; subsequently, as the levels of YFPpp71 increased, both hDaxx and YFPpp71 exhibited an increasingly dispersed distribution within the nucleus. The colocalization of YFPpp71 and hDaxx suggests a stable interaction between the two proteins. However, in some cells at late times (e.g., 24 h) after infection with in1316, YFPpp71 was found in intensely fluorescent aggregates within the nucleus and hDaxx, where detectable, was present in an abnormal distribution, distinct from the aggregates (results not shown).

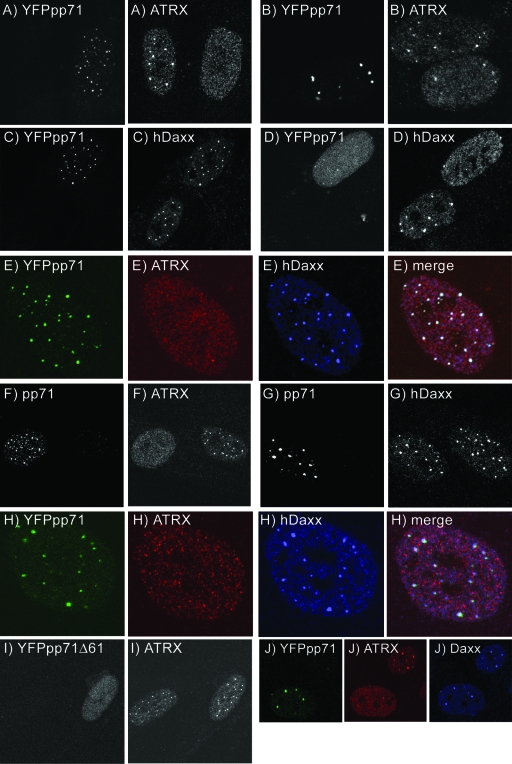

FIG. 3.

Dissociation of ATRX from ND10 by pp71. HFFF2 monolayers were infected or transfected and analyzed by IF. (A and B) Dispersal and partial dispersal, respectively, of ATRX in cells at 3 h postinfection at 38.5°C with in1316 (MOI, 0.1). (C) Colocalization of YFPpp71 with hDaxx at 3 h after infection at 38.5°C with in1316. (D) Dispersal of both YFPpp71 and hDaxx in an in1316-infected cell expressing greater amounts of YFPpp71 at 7 h postinfection. (E) Simultaneous detection of YFPpp71, ATRX, and hDaxx at 3 h postinfection at 38.5°C with in1316, demonstrating dispersal of ATRX but punctate hDaxx. (F and G) Distributions of ATRX and Daxx, respectively, in cells expressing untagged pp71 3 h postinfection at 38.5°C with in1360 (MOI of 0.1). (H) Dispersal of ATRX but punctate hDaxx 4 h posttransfection of pYFPpp71 into HFFF2 cells. (I) ATRX remains in punctate foci at 3 h postinfection at 38.5°C with in0125. (J) A mixture of C4N and CV-1(F) cultures. In cells with low-level expression of YFPpp71, the protein colocalized with Daxx foci but ATRX was dispersed.

Input HSV-1 genomes become templates for the assembly of ND10 structures very shortly after infection (15). Two control experiments were carried out to eliminate the possibility that input HSV-1 genomes recruit hDaxx but not ATRX to the new structures. First, plasmid pYFPpp71 was transfected into HFFF2 cells and IF was carried out after 4 h. Although the pattern of expression of YFPpp71 within the culture was more heterogeneous than after infection with in1316, cells containing the lowest amounts of YFPpp71 exhibited a punctate distribution of the protein which colocalized with that of hDaxx, whereas ATRX was dispersed (Fig. 3H). Analogous results were obtained after transfection of a plasmid expressing myc-tagged pp71 (results not shown). As a second control, cells were infected with recombinant in0125, which is identical to in1316 apart from the removal of the C-terminal 61 amino acids from YFPpp71 and an insertion of Escherichia coli lacZ at the UL43 locus. The protein expressed by in0125 enters the nucleus but is nonfunctional and does not localize to ND10, presumably because it fails to interact with hDaxx (44). Cells infected with in0125 retained ATRX at ND10 (Fig. 3I), demonstrating that the presence of an HSV-1 genome was not a determining factor in altering the distribution of ATRX.

As a further demonstration that pp71 dissociates ATRX from ND10, the CV-1 cell line C4N, which constitutively expresses YFPpp71, was examined. Approximately 50% of cells in the culture expressed low levels of YFPpp71 with the protein concentrated in foci, whereas in the remaining cells greater amounts of the protein were produced. ATRX was dispersed within the nuclei of virtually all cells in the C4N culture, whereas Daxx localized to ND10 in those cells expressing low levels of YFPpp71 and throughout the nucleus in those with higher levels. In the parental cell line CV-1(F), ATRX and Daxx were detected in ND10 foci [images of C4N and CV-1(F) cultures are available at ftp://gamma.vir.gla.ac.uk/pub/lukashchuk (Fig. S1)]. Analysis of a 1:1 mixture of C4N and CV-1(F) emphasized the specific effect of YFPpp71 on the localization of ATRX. Cells expressing low levels of YFPpp71 exhibited dispersed ATRX but punctate Daxx (Fig. 3J), whereas cells with higher levels of YFPpp71 contained all three proteins in a dispersed distribution (results not shown).

The possibility that ATRX is important for the initial interaction of pp71 with hDaxx was considered but was eliminated by the observation that YFPpp71 colocalized with hDaxx at ND10 in ATRX-depleted HF-shA90 cells infected with in1316 (results not shown).

ATRX dissociates from ND10 at early times after HCMV infection.

The above results demonstrate that exogenous expression of pp71 promotes the rapid dissociation of ATRX from hDaxx, with a subsequent slower release of hDaxx from ND10 as the levels of pp71 increase. During infection with HCMV, pp71 is delivered to the cell nucleus in a single event shortly after entry of virus particles, in contrast to the steady increase in levels that occurs after infection with in1316 or transfection of pYFPpp71. To investigate whether ATRX is released from ND10 after infection with HCMV, virus was allowed to adsorb to cells by incubation at 4°C for 1 h and cultures were then rapidly warmed to 37°C (taken as 0 h postadsorption [pa]). Monolayers of HFFF2 cells were infected with HCMV AD169 at an MOI of 2 and fixed at various times postadsorption. IF was carried out with antibodies specific for pp71, plus either anti-ATRX or anti-hDaxx. The earliest change observed was dispersal of ATRX in a portion of the cells. This was first detected at 0.5 h pa and became more widespread throughout the culture as the infection progressed to 2 h pa (Fig. 4A and C) (see also our supplementary Fig. S2C and D available at ftp://gamma.vir.gla.ac.uk/pub/lukashchuk). Dispersal of ATRX correlated with the amount of pp71 detected in nuclei. Visual scanning of coverslips revealed rare cells that had no pp71 signal; it is not clear whether these were uninfected or contained pp71 at undetectable levels, but ATRX remained in a punctate distribution in such cells. Our supplementary Fig. S2E and F (available at ftp://gamma.vir.gla.ac.uk/pub/lukashchuk) show four nuclei at 1 h pa, demonstrating dispersal of ATRX in the two with the greatest amounts of pp71, partial dispersal in a nucleus containing lower amounts of pp71, and no obvious change in ATRX when pp71 was undetectable. At times up to 1 h pa, hDaxx remained in foci (Fig. 4B) at levels that were not detectably different from those observed in mock-infected cells, which were analyzed separately. This generally remained the case at 2 h (Fig. 4D), although at that time hDaxx was dispersed from ND10 in a small proportion of cells. Simultaneous detection of pp71, ATRX, and hDaxx confirmed the dispersal of ATRX but retention of hDaxx at ND10, colocalized with pp71, at 1 h pa (Fig. 4E). At times later than 2 h pa hDaxx was observed in many cells to be present in smaller, more numerous foci, often at apparently lower levels than in nuclei of control cells. This could be an effect of virion components, but it is also possible that de novo-synthesized IE1 protein had begun to affect the ND10 structures, since IF analysis indicated that approximately 4% of cells were weakly positive for IE1/IE2 by 2 h pa. A detailed understanding of the subtle changes in the intranuclear distribution of hDaxx that occurred from 2 h pa onward is beyond the scope of the work presented here.

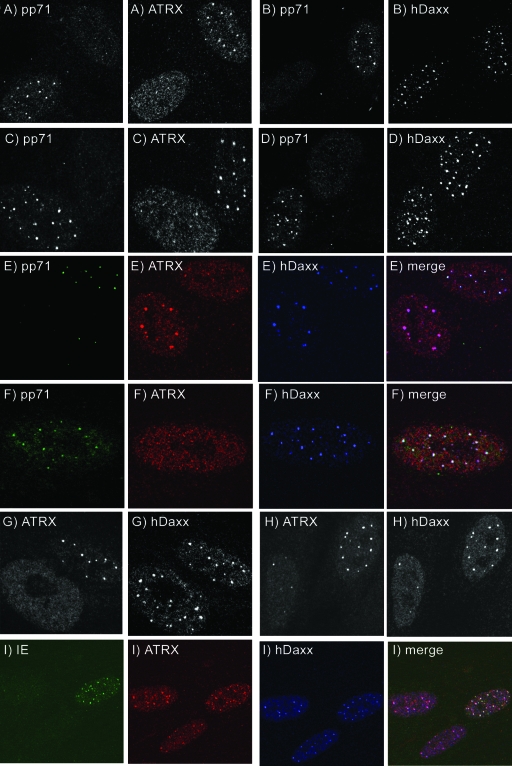

FIG. 4.

Dissociation of ATRX from ND10 in HCMV-infected cells. (A to D) HFFF2 cells at 1 h pa (A and B) and at 2 h pa (C and D) after infection with HCMV at an MOI of 2. (E) Cells at 1 h pa after infection with HCMV, at an MOI of 2, detecting pp71, ATRX, and hDaxx, demonstrating dispersed ATRX but punctate hDaxx in a cell containing pp71. (F and G) Cells infected with UV-irradiated HCMV at 1 h pa. (H) Cells infected with HCMV, at an MOI of 0.25, at 3 h pa. (I) HFFF2 cells infected with ADsubUL82 at 7 h postinfection, demonstrating punctate ATRX and hDaxx in an IE protein-expressing cell.

Various control experiments were carried out to verify that ATRX was dissociated from ND10 prior to any detectable effects on hDaxx localization. The effect was reproduced using different primary and secondary antibodies for the detection of ATRX and hDaxx (results not shown). Virions purified by glycerol-tartrate gradient centrifugation (53) gave the same effects as virus stocks prepared from infected cell medium, demonstrating that neither noninfectious enveloped particles nor dense bodies were required for the effect (results not shown). UV-irradiated HCMV also dispersed ATRX, while leaving hDaxx in foci, at 1 h pa (Fig. 4F and G) and 2 h pa (not shown). It is noteworthy, however, that an increasingly dispersed localization of hDaxx was observed in many cells at later times after infection with UV-irradiated HCMV, similar to the changes observed after infection with unirradiated virus. This observation supports the view that virion components, including pp71, initiate a progressive disruption of ND10. Infection with the pp71-null mutant ADsubUL82 did not disperse ATRX from ND10 foci, even in IE-positive cells at 7 h postinfection (Fig. 4I), confirming that pp71 is required for the effect. At 7 h postinfection with ADsubUL82 at the low MOI used, the majority of IE-positive nuclei (28 of 29 counted) exhibited the punctate, ATRX intact, fluorescence pattern shown in Fig. 4I, whereas >90% of AD169-infected cells had dispersed ATRX and hDaxx. The preponderance of ADsubUL82-infected cells expressing low levels of IE proteins without apparent disruption of ND10 was surprising but reproducible. This observation was confirmed and extended by experiments depicted in Fig. 9 and Table 1, below. The rescuant of ADsubUL82, ADrevUL82, behaved in the same way as wild-type HCMV (results not shown).

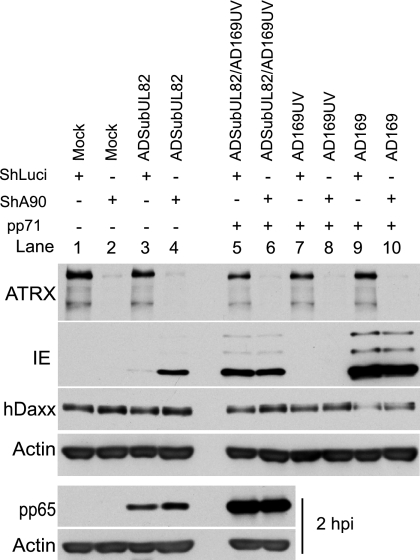

FIG. 9.

HCMV IE gene expression and ATRX localization. (A and B) HFFF2 cells infected with ADsubUL82 at 17 h postinfection, giving examples of low-level (A) and high-level (B) IE expression. (C and D) HF-shLuci and HF-shA90 cultures 12 h after infection with ADsubUL82 (0.2 infectious units per cell); the images are representative of those used to generate the data in Table 1. (E to H) HFFF2 cells infected with wild-type HCMV, at an MOI of 0.5, analyzed at 2.5 h pa. Images were selected to include cells with both low-level and undetectable IE protein content. (E and F) IE production in cells with dispersed or punctate ATRX, respectively; (G and H) IE production in cells with dispersed or punctate hDaxx, respectively.

TABLE 1.

IE gene expression in ATRX-depleted cellsa

| Cells | Virus(es) | No. of cellsb

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High IE | Low IE | Total | IE positive (%) | ||

| HF-shLuci | Sub82 | 5 | 66 | 779 | 9.1 |

| HF-shA90 | Sub82 | 78 | 36 | 766 | 14.8 |

| HF-shLuci | Sub82 + AD169UV | 94 | 6 | 383 | 26.1 |

| HF-shA90 | Sub82 + AD169UV | 113 | 9 | 439 | 27.8 |

| HF-shLuci | AD169 | 69 | 6 | 158 | 47.5 |

| HF-shA90 | AD169 | 54 | 6 | 169 | 35.5 |

HF-shLuci or HF-shA90 cultures were infected with ADsubUL82 (Sub82; 0.2 infectious units/cell), ADsubUL82 plus UV-irradiated HCMV (AD169UV; MOI of 3, based on original titer), or wild-type HCMV (AD169; MOI of 0.3). At 12 h postinfection, coverslips were fixed and reacted with antibodies specific for HCMV IE proteins and ATRX.

IE-positive cells were classified as present in low or high amounts, as shown in Fig. 9A and B, respectively.

To quantify the effect of infection at early times, nuclei were scored as exhibiting punctate or dispersed ATRX and hDaxx, taking detection of one or no distinct foci as the criterion for “dispersed.” This approach does not take into account changes in the overall number or intensity of ATRX and hDaxx foci; nonetheless, the combined results from three experiments demonstrated a multiplicity dependence of ATRX dissociation from ND10 and relatively unchanged overall localization of hDaxx at 1 and 2 h pa (Fig. 5).

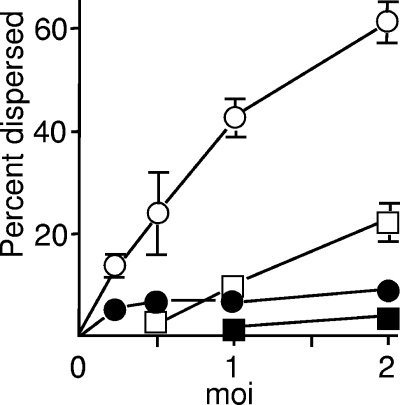

FIG. 5.

Multiplicity dependence of ATRX dispersal. Cells were infected with HCMV and stained for ATRX and hDaxx. Fluorescence patterns were scored as dispersed if one or no discrete foci were detectable. Open squares, ATRX at 1 h pa; filled squares, hDaxx at 1 h pa; open circles, ATRX at 2 h pa; filled circles, hDaxx at 2 h pa. The data were taken from three independent experiments, one of which used different primary antibodies.

To confirm that the dispersal of ATRX occurred prior to any detectable effects on hDaxx levels, protein blot assays were carried out on cultures infected with HCMV at an MOI of 2 or 0.5 (Fig. 6). No reduction was observed in the levels of hDaxx or ATRX during the first 4 hours pa, with IE protein production detectable at 3 h pa in cultures infected at an MOI of 2.

FIG. 6.

ATRX and hDaxx levels in HCMV-infected cells. HFFF2 monolayers were mock infected (lane 5) or infected with HCMV at an MOI of 2 (lanes 1 to 4) or 0.5 (lanes 6 to 9). Extracts were prepared at 1, 2, 3, or 4 h pa and protein contents analyzed.

The data presented in Fig. 4 and 5 show dissociation of ATRX from ND10 in the absence of significant effects on hDaxx at early times after infection at a high MOI. When investigating infection at a lower MOI, such that most infected cells received only a single PFU of HCMV, fewer cells than expected exhibited dispersed ATRX and focal hDaxx at 2 h pa. Continuing the experiment for longer periods did not result in a disparity in the localization of the two proteins. Instead, a coordinated dispersal and apparent diminution of nuclear IF signal for both ATRX and hDaxx was observed in a proportion of cells at 3 and 4 h pa (Fig. 4H). Therefore, the differential effects on ATRX and hDaxx were dependent on the amount of pp71 delivered to the cell, since after infection at a low MOI the two proteins appeared to respond in an equivalent manner, remaining in foci but at levels that decreased in concert until they were dispersed throughout the nucleus.

ATRX contributes to the repression of HCMV immediate-early transcription in the absence of pp71.

If the dispersal of ATRX is functionally important for HCMV IE gene expression, it follows that, by analogy with the situation regarding hDaxx, removal of ATRX should result in greater IE protein production by the pp71-null mutant ADsubUL82. Accordingly, HF-shLuci and HF-shA90 cells were infected with either AD169, ADsubUL82 alone, or UV-inactivated AD169 (AD169UV) or coinfected with ADsubUL82 and AD169UV. Samples were prepared for analysis 18 h after infection (Fig. 7). AD169UV was inactivated to the extent that it failed to express detectable levels of IE protein (Fig. 7, lanes 7 and 8) but contained functional pp71 and thus complemented ADsubUL82 (Fig. 7, lanes 5 and 6). Therefore, coinfection with ADsubUL82 and AD169UV provided a measure of the maximum potential of ADsubUL82 to express IE proteins at the MOI used.

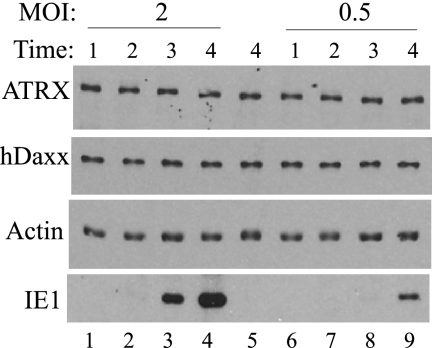

FIG. 7.

IE production after infection of ATRX-depleted cultures with ADsubUL82. Control (ShLuci) and ATRX-depleted (ShA90) cells were mock infected or infected with ADsubUL82 (0.2 infectious units per cell), AD169 (MOI of 0.3), AD169UV (MOI of 3 based on the original titer) alone, or coinfected with ADsubUL82 and AD169UV, and harvested for Western blot analysis of ATRX, HCMV IE proteins, hDaxx, and actin at 18 h postinfection or pp65 and actin at 2 h postinfection.

As expected, ATRX depletion did not affect the capability of pp71 to transactivate IE gene expression, since the levels of IE protein expressed in the AD169-infected and ADsubUL82/AD169UV-coinfected cells were essentially equivalent in both HF-shLuci and HF-shA90 cells (Fig. 7, lanes 5, 6, 9, and 10). The equivalence of pp65 content at 2 h postinfection confirms that HF-shLuci and HF-shA90 cells were equally susceptible to infection with ADsubUL82 and AD169UV (Fig. 7, lower panels, lanes 3 to 6). When cells were infected with ADsubUL82, a very low amount of IE protein was produced at 18 h postinfection in HF-shLuci cells (Fig. 7, lane 3), and this was significantly greater in HF-shA90 cells (Fig. 7, lane 4). The increase was observed consistently but to a variable extent in the analysis of independently derived cell lines, depending on the level of ATRX depletion, and did not always attain the levels seen in ADsubUL82/AD169UV-coinfected samples. These data indicate that depletion of ATRX allows increased IE protein expression in the absence of pp71. To ensure that the increased IE protein synthesis in HF-shA90 cells was not due to an unexpected loss of hDaxx, the samples from the above experiment were analyzed for hDaxx levels. The increased IE protein expression in ADsubUL82-infected HF-shA90 cells could not be attributed to an effect on hDaxx, since this protein was present at equivalent amounts in the HF-shLuci mock-infected or ADsubUL82-infected cells (Fig. 7, lanes 1 to 4). In cells infected with either AD169 or AD169UV, the levels of hDaxx were reduced in both HF-shLuci and HF-shA90 cells compared with the levels in mock-infected cells, presumably through the activity of pp71 at this time after infection, showing that ATRX is not required for pp71 to degrade hDaxx during HCMV infection.

In addition to increased IE protein synthesis, depletion of ATRX permitted more efficient replication of ADsubUL82. Plaques were detectable from 7 days postinfection onwards in HF-shA90, but not HF-shLuci, cultures (Fig. 8), and yields of ADsubUL82 after 11 days were 140 to 560 infectious units/culture (five determinations) in HF-shA90 cells, whereas only 0 to 5 infectious units were produced in HF-shLuci cells. Wild-type AD169 replicated to titers of (6.2 ± 0.5) × 104 and (2.8 ± 0.7) × 104 PFU/ml (means ± standard variations) after 6 days in HF-shA90 and HF-shLuci cultures, respectively.

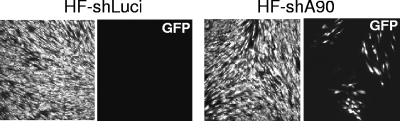

FIG. 8.

Increased replication of ADsubUL82 in ATRX-depleted cells. HF-shLuci or HF-shA90 cells were infected with ADsubUL82 (0.2 infectious units per cell) and incubated at 37°C for 11 days. Replicating virus was detected by fluorescence due to the green fluorescent protein (GFP) sequences inserted into the UL82 coding region, and cultures were also stained with propidium iodide.

To investigate further the role of ATRX in repression of HCMV IE gene expression, HF-shLuci and HF-shA90 cells were infected and analyzed by IF at 12 h postinfection. At this and later times, the distribution of IE proteins could readily be classified as low level and punctate or high level and dispersed (Fig. 9A and B). PML was present in intact ND10 foci in cells with a punctate IE protein distribution (Fig. 9A), whereas it was dispersed in those with a high-level IE signal (Fig. 9B). Quantification revealed that most IE-positive cells (66 of 71 identified) exhibited the low-level, punctate pattern after ADsubUL82 infection of HF-shLuci cultures, whereas the majority (69/75), as expected, showed high-level expression after infection with wild-type HCMV (Fig. 9C and Table 1). This finding is consistent with that described above for HFFF2 cells at 7 h after infection with ADsubUL82 (Fig. 4I). In cultures infected with ADsubUL82, the proportion of nuclei positive for IE expression was less than twofold greater for HF-shA90 cells than the HF-shLuci controls (14.8% compared with 9.1%). The pattern of expression was very different, however, since most (78/114) HF-shA90 IE-positive cells exhibited high-level expression but only a small minority (5/71) of HF-shLuci IE-positive cells had this distribution (Fig. 9C and D and Table 1; see also supplementary Fig. S3, available at ftp://gamma.vir.gla.ac.uk/pub/lukashchuk). The greater IE protein production in ATRX-depleted cells was therefore predominantly due to increased expression per infected cell rather than a major change in the number of cells initiating IE gene expression. A similar conclusion was reached when considering the effect of pp71, provided by coinfection with AD169UV. In HF-shLuci cultures, the increase in proportion of cells positive for IE proteins was only threefold (26.1% compared with 9.1%) but, of these, 94% exhibited the high-level pattern. Therefore, the main effect of pp71 was an increase in IE protein expression per infected cell and a consequent disruption of ND10. Infection with AD169, or ADsubUL82 plus AD169UV, was comparable in terms of proportions of positive cells and pattern of IE protein distribution, confirming that HF-shLuci and HF-shA90 cell lines were permissive for HCMV to equivalent extents (Table 1).

Dispersal of ATRX is important but not essential for initiation of IE gene expression.

To confirm the functional significance of ATRX dispersal, HFFF2 cultures infected with wild-type HCMV (MOI, 0.5) were screened at an early time (2.5 h pa) for the presence of IE proteins and ATRX. The small number of IE-positive cells detected at this time exhibited a weak, punctate signal, indicating that although IE protein synthesis had commenced, disruption of ND10 through effects on PML had not occurred. In the majority of such cells, ATRX was dispersed (Fig. 9E), confirming that the observed effects on ATRX localization were correlated with the initiation of IE gene expression. Surprisingly, however, a minority (<5%) of IE-positive cells retained ATRX foci that were indistinguishable from those in uninfected cells (Fig. 9F). Examination of hDaxx revealed an analogous finding: the majority of IE-positive cells contained the protein in a dispersed or partially dispersed distribution (Fig. 9G), but it was possible to detect cells, again at low frequency, with apparently normal foci of hDaxx (Fig. 9H). Therefore, HCMV-mediated alteration of ATRX and hDaxx localization is important, but not indispensable, for the initiation of viral IE gene expression.

DISCUSSION

In common with many DNA viruses, HCMV has evolved mechanisms to overcome host nuclear intrinsic defenses (12, 13). The HCMV structural protein pp71 is involved in the earliest stages of viral transcription, and we show here that it promotes the rapid displacement of ATRX from ND10 structures, followed by a more gradual removal of hDaxx. We also demonstrate that ATRX contributes to cellular intrinsic defenses against HCMV infection.

Displacement of ATRX from ND10 was observed by 3 h after infection with the HSV-1 recombinant in1316, whereas significant release of hDaxx was only detectable at later times, commencing at 7 h postinfection. Previous studies have shown that activation of gene expression, using HSV-1 recombinants as reporters, can be detected after a time period of 9 h, including a 2-h preincubation with a pp71-expressing virus such as in1316, a period during which pp71 is colocalized with hDaxx in ND10 foci (23, 35). Therefore, in this assay system the functional activity of pp71 correlated more closely with the dissociation of ATRX from ND10 than with major effects on the localization of hDaxx. The observation that dispersal of ATRX occurred in cells infected with in1316 or transfected with pYFPpp71 demonstrates that pp71 alone can mediate the effect.

During infection with HCMV at an MOI of 2, dispersal of ATRX occurred at very early times, before any effects on hDaxx were detectable. This was also observed in cultures infected with UV-irradiated HCMV, but not in those infected with ADsubUL82, confirming that pp71 is required for the early effect and that de novo-synthesized viral proteins do not contribute to it. The dispersal of hDaxx, observed later than the dissociation of ATRX after infection at an MOI of 2, was more rapid than in cells infected with in1316, suggesting that other factors, specified or induced by HCMV, contribute to the relocation of hDaxx from ND10. The observation that UV irradiation did not prevent the effect indicates that the additional factors are components of the virion, rather than viral proteins synthesized de novo.

The alterations in nuclear localization of ATRX and hDaxx were readily observable by microscopy, but quantification of the effects was difficult. In particular, the apparent fragmentation of the hDaxx signal in some cells after 2 h pa could not readily be measured objectively because parameters such as number and intensity of foci varied considerably even in uninfected cells. We took detection of one or no discernible foci as the criterion for dispersal of ATRX or hDaxx, an endpoint measure that did not take into account partial effects that were observed in some cells in the cultures. This approach revealed a good correlation between MOI and proportion of nuclei with dispersed ATRX but a less clear relationship with the effects on hDaxx at 2 h pa (Fig. 5) or later (results not shown). The findings are consistent with a stoichiometric relationship between pp71 and ATRX, suggesting that pp71 acts by displacing ATRX from hDaxx. The binding sites on hDaxx for the two proteins are not identical: it has been reported that ATRX interacts with the N-terminal portion of hDaxx (54), and although the two relevant studies reached different conclusions regarding the pp71-interacting domains of hDaxx, they concurred that residues in the central region are important (21, 27). Displacement of ATRX may therefore be a consequence of pp71 binding to adjacent regions of hDaxx rather than competition for the same site. Following the dissociation of ATRX from ND10, hDaxx gradually exhibited a more dispersed localization within the nucleus, and it is possible that this change predisposes hDaxx to proteolysis (24, 50). At the early times examined in our study, extensive degradation was not detected, in agreement with the recent findings of others (37, 56), although a reduction in the amount of hDaxx was evident at 18 h postinfection.

Although dissociation of ATRX from ND10 occurred sooner than any detectable effects on hDaxx localization after infection with HCMV at an MOI of 2, the temporal separation of the two responses was much less clear at an MOI of 0.25. This observation suggests that HCMV-induced changes to hDaxx localization are not dependent on complete removal of ATRX from ND10. If, as proposed above, the dispersal of ATRX is due to dissociation of the protein from hDaxx, it follows that complete removal of ATRX from ND10 would not be observed microscopically when amounts of pp71 were below those of ATRX. If pp71 exerted a catalytic effect on hDaxx, such as stimulating its removal from ND10 and/or degradation, a gradual loss of IF signal, as observed experimentally, would occur. Under such circumstances, ATRX and hDaxx would be lost from ND10 simultaneously, since the former protein's location depends on that of the latter.

The functional significance of ATRX as a component of cellular defenses was confirmed by the observation that cells depleted of the protein supported higher levels of IE gene expression and virus replication in the absence of pp71. The complementation of ADsubUL82 may not be complete, since provision of pp71 by coinfection with AD169UV often gave a further increase in IE protein levels, but the magnitude of the effect appeared to be similar to that achieved by reducing hDaxx levels (8, 9, 45). In view of the dependence of ATRX on hDaxx for localization to ND10, it is likely that the release of repression by depletion of hDaxx is at least partly due to the resulting dispersal of ATRX, but it must be emphasized that other partners of hDaxx are known repressors of eukaryotic transcription and may also contribute to cell defenses against HCMV (22, 33, 59).

A minority of HCMV-infected cells were IE positive yet harbored ATRX and hDaxx localized at ND10 at apparently normal levels. This observation emphasizes that neither cellular protein is able to repress transcription totally from incoming genomes, a fact that is corroborated by studies with ADsubUL82. This mutant is able to initiate IE gene expression, albeit at low efficiency, but does not affect ATRX or hDaxx nuclear localization until IE1 protein causes disruption of ND10 through its effects on PML (7). Significantly, ADsubUL82 initiates IE transcription at nuclear sites distinct from ND10 (27) and it is not clear whether intrinsic defenses involving hDaxx operate on these non-ND10 associated genomes, nor is it known if these genomes are able to progress to full expression. It is therefore possible that the cells exhibiting IE expression and intact ND10 after infection with wild-type HCMV represent a minor population in which input genomes that are not localized to ND10 initiate IE transcription through an alternative pathway, analogous to that used by ADsubUL82.

It was surprising that depletion of ATRX resulted in only a modest (<2-fold) increase in the number of IE-positive cells observed after infection with ADsubUL82. There was, however, a significant rise in the proportion of cells expressing high levels of IE proteins, and this response largely accounted for the increased amount of protein detected on blots. Indeed, provision of pp71 by coinfection with AD169UV only raised the number of positive cells by threefold but altered the profiles of infected cells such that most exhibited high-level IE protein production. These observations suggest that a major consequence of the absence of pp71 is failure of IE proteins to disrupt ND10, rather than an absolute block to IE gene expression. Recently, Tavalai et al. showed that PML and hDaxx exert independent roles in repression of incoming HCMV genomes, since depletion of either protein resulted in increased IE expression from both pp71 and IE1 null mutants (56). Our results support this view but show further complexity, since the prior effects of pp71 on ATRX and hDaxx influenced the efficacy with which IE1 subsequently dispersed PML.

Dispersal of ATRX by pp71 is an important step in the activation of viral IE gene expression, and we propose two basic models to explain its role in the early events of infection. The most obvious interpretation is that ATRX contributes to the repression of incoming HCMV genomes by remodeling chromatin, following its predicted repressive effects on transcription of cellular genes. It is known that chromatin structure at the MIEP is an important determinant of IE gene expression (40, 42, 46, 59, 60), and therefore the reported ATRX-mediated alterations in histone deposition might be an initial step toward the establishment of a repressive nucleosomal arrangement at the MIEP and elsewhere on the genome (62). As an alternative model, repression by ATRX may not depend on the protein's effects on chromatin assembly but, in a less specific manner, through stabilization of ND10. Removing ATRX and/or hDaxx from ND10 may enable IE1 to target PML more readily and thus dismantle the structures more efficiently, resulting in robust expression from the entire HCMV genome.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council and European Union project FP6-037517 “TargetHerpes.” V.L. was supported by a Medical Research Council studentship.

We thank Duncan McGeoch for helpful comments on the manuscript, Carlos Parada for input, Mary Jane Nicholl for assistance, and Richard Gibbons, Roel van Driel, Tom Shenk, and Thomas Stamminger for providing reagents.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 October 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, J. H., and G. S. Hayward. 2000. Disruption of PML-associated nuclear bodies by IE1 correlates with efficient early stages of viral gene expression and DNA replication in human cytomegalovirus infection. Virology 27439-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn, J.-H., and G. S. Hayward. 1997. The major immediate-early proteins IE1 and IE2 of human cytomegalovirus colocalize with and disrupt PML-associated nuclear bodies at very early times in infected permissive cells. J. Virol. 714599-4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Argentaro, A., J.-C. Yang, L. Chapman, M. S. Kowalczyk, R. J. Gibbons, D. R. HIggs, D. Neuhaus, and D. Rhodes. 2007. Structural consequences of disease-causing mutations in the ATRX-DNMT3L (ADD) domain of the chromatin-associated protein ATRX. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10411939-11944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldick, C. J., A. Marchini, C. E. Patterson, and T. Shenk. 1997. Human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp71 (ppUL82) enhances the infectivity of viral DNA and accelerates the infectious cycle. J. Virol. 714400-4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumann, C., A. Schmidtmann, K. Muegge, and R. De La Fuente. 2008. Association of ATRX with pericentric heterochromatin and the Y chromosome of neonatal mouse spermatogonia. BMC Mol. Biol. 929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berube, N. G., J. Healy, C. F. Medina, S. Wu, T. Hodgson, M. Jagla, and D. J. Picketts. 2007. Patient mutations alter ATRX targeting to PML nuclear bodies. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 16192-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bresnahan, W. A., and T. E. Shenk. 2000. UL82 virion protein activates expression of immediate early viral genes in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9714506-14511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cantrell, S. R., and W. A. Bresnahan. 2006. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) UL82 gene product (pp71) relieves hDaxx-mediated repression of HCMV replication. J. Virol. 806188-6191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cantrell, S. R., and W. A. Bresnahan. 2005. Interaction between the human cytomegalovirus UL82 gene product (pp71) and hDaxx regulates immediate-early gene expression and viral replication. J. Virol. 797792-7802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chau, N. H., C. D. Vanson, and J. A. Kerry. 1999. Transcriptional regulation of the human cytomegalovirus US11 early gene. J. Virol. 73863-870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolan, A., C. Cunningham, R. D. Hector, A. F. Hassan-Walker, L. Lee, C. Addison, D. J. Dargan, D. J. McGeoch, D. Gatherer, V. C. Emery, P. D. Griffiths, C. Sinzger, B. P. McSharry, G. W. G. Wilkinson, and A. J. Davison. 2004. Genetic content of wild-type human cytomegalovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 851301-1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Everett, R. D. 2001. DNA viruses and viral proteins that interact with PML nuclear bodies. Oncogene 207266-7273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Everett, R. D. 2006. Interactions between DNA viruses, ND10 and the DNA damage response. Cell Microbiol. 8365-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Everett, R. D., W. C. Earnshaw, J. Findlay, and P. Lomonte. 1999. Specific destruction of kinetochore protein CENP-C and disruption of cell division by herpes simplex virus immediate-early protein Vmw110. EMBO J. 181526-1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Everett, R. D., and J. Murray. 2005. ND10 components relocate to sites associated with herpes simplex virus type 1 nucleoprotein complexes during virus infection. J. Virol. 795078-5089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Everett, R. D., J. Murray, A. Orr, and C. M. Preston. 2007. Herpes simplex virus type 1 genomes are associated with ND10 nuclear substructures in quiescently infected human fibroblasts. J. Virol. 8110991-11004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Everett, R. D., C. Parada, P. Gripon, H. Sirma, and A. Orr. 2008. Replication of ICP0-null mutant herpes simplex virus type 1 is restricted by both PML and Sp100. J. Virol. 822661-2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Everett, R. D., S. Rechter, P. Papior, N. Tavalai, T. Stamminger, and A. Orr. 2006. PML contributes to a cellular mechanism of repression of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection that is inactivated by ICP0. J. Virol. 807995-8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibbons, R. J., D. J. Picketts, and D. R. Higgs. 1995. Mutations in a putative global transcriptional regulator cause X-linked mental retardation with α-thalassemia (ATR-X syndrome). Cell 80837-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hensel, G. M., H. H. Meyer, I. Buchmann, D. Pommerehne, S. Schmolke, B. Plachter, K. Radsak, and H. F. Kern. 1996. Intracellular localization and expression of the human cytomegalovirus matrix phosphoprotein pp71 (ppUL82): evidence for its translocation into the nucleus. J. Gen. Virol. 773087-3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofmann, H., H. Sindre, and T. Stamminger. 2002. Functional interaction between the pp71 protein of human cytomegalovirus and the PML-interacting protein human Daxx. J. Virol. 765769-5783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hollenbach, A. D., C. J. McPherson, E. J. Mientjes, R. Lyengar, and G. Grosveld. 2002. Daxx and histone deacetylase II associate with chromatin through an interaction with core histones and the chromatin-associated protein Dek. J. Cell Sci. 1153319-3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Homer, E. G., A. Rinaldi, M. J. Nicholl, and C. M. Preston. 1999. Activation of herpesvirus gene expression by the human cytomegalovirus protein pp71. J. Virol. 738512-8518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hwang, J. W., and R. F. Kalejta. 2007. Proteasome-dependent, ubiquitin-independent degradation of Daxx by the viral pp71 protein in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells. Virology 367334-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishov, A. M., A. G. Sotnikov, D. Negerov, O. V. Vladimirova, N. Neff, T. Kamitani, E. T. Yeh, J. F. Strauss III, and G. G. Maul. 1999. PML is critical for ND10 formation and recruits the PML-interacting protein Daxx to this nuclear structure when modified by SUMO-1. J. Cell Biol. 138221-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishov, A. M., R. M. Stenberg, and G. G. Maul. 1997. Human cytomegalovirus immediate early interaction with host nuclear structures: definition of an immediate transcript environment. J. Cell Biol. 1385-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishov, A. M., O. V. Vladimirova, and G. G. Maul. 2002. Daxx-mediated accumulation of human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp71 at ND10 facilitates initiation of viral infection at these nuclear domains. J. Virol. 767705-7712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishov, A. M., O. V. Vladimirova, and G. G. Maul. 2004. Heterochromatin and ND10 are cell-cycle regulated and phosphorylation-dependent alternate nuclear sites of the transcription repressor Daxx and SWI/SNF protein ATRX. J. Cell Sci. 1173807-3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly, C., R. van Driel, and G. W. G. Wilkinson. 1995. Disruption of PML-associated nuclear bodies during human cytomegalovirus infection. J. Gen. Virol. 762887-2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korioth, F., G. G. Maul, B. Plachter, T. Stamminger, and J. Frey. 1996. The nuclear domain 10 (ND10) is disrupted by the human cytomegalovirus gene product IE1. Exp. Cell Res. 229155-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, H.-R., D.-J. Kim, J.-M. Lee, C. Y. Choi, B.-Y. Ahn, G. S. Hayward, and J.-H. Ahn. 2004. Ability of the human cytomegalovirus IE1 protein to modulate sumoylation of PML correlates with its functional activities in transcriptional regulation and infectivity in cultured fibroblast cells. J. Virol. 786527-6542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, H., C. Lieo, J. Zhu, X. Wu, J. O'Neill, E.-J. Park, and J. D. Chen. 2000. Sequestration and inhibition of Daxx-mediated transcriptional repression by PML. Mol. Cell. Biol. 201784-1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, R., H. Pei, D. K. Watson, and T. S. Papas. 2000. EAP1/Daxx interacts with ETS1 and represses transcriptional activation of ETS1 target genes. Oncogene 19745-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu, B., and M. F. Stinski. 1992. Human cytomegalovirus contains a tegument protein that enhances transcription from promoters with upstream ATF and AP-1 cis-acting elements. J. Virol. 664434-4444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marshall, K. R., K. V. Rowley, A. Rinaldi, I. P. Nicholson, A. M. Ishov, G. G. Maul, and C. M. Preston. 2002. Activity and intracellular localization of the human cytomegalovirus protein pp71. J. Gen. Virol. 831601-1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maul, G. G. 1998. Nuclear domain 10, the site of DNA virus transcription and replication. Bioessays 26660-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maul, G. G., and D. Negerov. 2008. Differences between mouse and human cytomegalovirus interactions with their respective hosts at immediate early times of the replication cycle. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 197241-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michaelson, J. S. 2000. The Daxx enigma. Apoptosis 5217-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michaelson, J. S., and P. Leder. 2003. RNAi reveals anti-apoptotic and transcriptionally repressive activities of DAXX. J. Cell Sci. 116345-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy, J. C., W. Fischle, E. Verdin, and J. H. Sinclair. 2002. Control of cytomegalovirus lytic gene expression by histone acetylation. EMBO J. 211112-1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nan, X., J. Hou, A. Maclean, J. Nasir, M. J. Lafuente, X. Shu, S. Kriaucionis, and A. Bird. 2007. Interaction between chromatin proteins MECP2 and ATRX is disrupted by mutations that cause inherited mental retardation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1042709-2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nevels, M., C. Paulus, and T. Shenk. 2004. Human cytomegalovirus immediate-early 1 protein facilitates viral replication by antagonizing histone deacetylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10117234-17239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pluta, A. F., W. C. Earnshaw, and I. G. Goldberg. 1998. Interphase-specific association of intrinsic centromere protein CENP-C with HDaxx, a death domain-binding protein implicated in Fas-mediated cell death. J. Cell Sci. 1112029-2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Preston, C. M., and M. J. Nicholl. 2005. Human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp71 directs long-term gene expression from quiescent herpes simplex virus genomes. J. Virol. 79525-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Preston, C. M., and M. J. Nicholl. 2006. Role of the cellular protein hDaxx in human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene expression. J. Gen. Virol. 871113-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reeves, M. B., P. A. MacAry, P. J. Lehner, J. P. G. Sissons, and J. H. Sinclair. 2005. Latency, chromatin remodeling, and reactivation of human cytomegalovirus in the dendritic cells of healthy carriers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1024140-4145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ritchie, K., C. Seah, J. Moulin, F. Isaac, and N. G. Berube. 2008. Loss of ATRX leads to chromosome cohesion and congressional defects. J. Cell Biol. 180315-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosenke, K., and E. A. Fortunato. 2004. Bromodeoxyuridine-labeled viral particles as a tool for visualization of the immediate-early events of human cytomegalovirus infection. J. Virol. 787818-7822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saffert, R. T., and R. F. Kalejta. 2007. Human cytomegalovirus gene expression is silenced by Daxx-mediated intrinsic immune defense in model latent infections established in vitro. J. Virol. 819109-9120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saffert, R. T., and R. F. Kalejta. 2006. Inactivating a cellular intrinsic defense mediated by Daxx is the mechanism through which the human cytomegalovirus pp71 protein stimulates viral immediate-early gene expression. J. Virol. 803863-3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salomoni, P., and A. F. Khelifi. 2006. Daxx: death or survival protein? Trends Cell Biol. 1697-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stuurman, N., A. de Graaf, A. Floore, A. Josso, B. Humbel, L. de Jong, and R. van Driel. 1992. A monoclonal antibody recognizing nuclear matrix-associated nuclear bodies. J. Cell Sci. 101773-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Talbot, P., and J. P. Almeida. 1977. Human cytomegalovirus: purification of enveloped virions and dense bodies. J. Gen. Virol. 36345-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang, J., S. Wu, H. Liu, R. Stratt, O. G. Barak, R. Shiekhatter, D. J. Picketts, and X. Yang. 2004. A novel transcription regulatory complex containing death domain-associated protein and the ATR-X syndrome protein. J. Biol. Chem. 27920369-20377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tavalai, N., P. Papior, S. Rechter, M. Leis, and T. Stamminger. 2006. Evidence for a role of the cellular ND10 protein PML in mediating intrinsic immunity against human cytomegalovirus infections. J. Virol. 808006-8018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tavalai, N., P. Papior, S. Rechter, and T. Stamminger. 2008. Nuclear domain 10 components promyelocytic leukaemia protein and hDaxx independently contribute to an intrinsic antiviral defense against human cytomegalovirus infection. J. Virol. 82126-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Torii, S., D. A. Egan, R. A. Evans, and J. C. Reed. 1999. Human Daxx regulates Fas-induced apoptosis from nuclear PML oncogenic domains (PODs). EMBO J. 186037-6049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilkinson, G. W., C. Kelly, J. H. Sinclair, and C. Rickards. 1998. Disruption of PML-associated nuclear bodies mediated by the human cytomegalovirus major immediate early gene product. J. Gen. Virol. 791233-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woodhall, D. L., I. J. Groves, M. B. Reeves, G. W. Wilkinson, and J. H. Sinclair. 2006. Human Daxx-mediated repression of human cytomegalovirus gene expression correlates with a repressive chromatin structure around the major immediate early promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 28137652-37660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wright, E., M. Bain, L. Teague, J. Murphy, and J. Sinclair. 2005. Ets-2 repressor factor recruits histone deacetylase to silence human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene expression in non-permissive cells. J. Gen. Virol. 86535-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu, Y., J.-H. Ahn, M. Cheng, C. M. apRhys, C.-J. Chiou, J. Zong, M. J. Matunis, and G. S. Hayward. 2001. Proteasome-independent disruption of PML oncogenic domains (PODs), but not covalent modification by SUMO-1, is required for human cytomegalovirus immediate-early protein IE1 to inhibit PML-mediated transcriptional repression. J. Virol. 7510683-10695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xue, Y., R. Gibbons, Z. Yan, D. Yang, T. L. McDowell, S. Sechi, J. Qin, S. Zhou, D. Higgs, and W. Wang. 2003. The ATRX syndrome protein forms a chromatin-remodeling complex with Daxx and localizes in promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10010635-10640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]