Abstract

Objectives To report the sensitivities of the faecal occult blood test, screening episode, and screening programme for colorectal cancer and the benefits of applying a randomised design at the implementation phase of a new public health policy.

Design Experimental design incorporated in public health evaluation using randomisation at individual level in the target population.

Setting 161 of the 431 Finnish municipalities in 2004-6.

Participants 106 000 adults randomised to screening or control arms. In total, 52 998 adults aged 60-64 in the screening arm received faecal occult blood test kits.

Main outcome measures Test, episode, and programme sensitivities estimated by the incidence method and corrected for selective attendance and overdiagnosis.

Results The response for screening was high overall (70.8%), and significantly better in women (78.1%) than in men (63.3%). The incidence of cancer in the controls was somewhat higher in men than in women (103 v 93 per 100 000 person years), which was not true for interval cancers (42 v 49 per 100 000 person years). The sensitivity of the faecal occult blood test was 54.6%. Only a few interval cancers were detected among those with positive test results, hence the episode sensitivity of 51.3% was close to the test sensitivity. At the population level the sensitivity of the programme was 37.5%.

Conclusions Although relatively low, the sensitivity of screening for colorectal cancer with the faecal occult blood test in Finland was adequate. An experimental design is a prerequisite for evaluation of such a screening programme because the effectiveness of preventing deaths is likely to be small and results may otherwise remain inconclusive. Thus, screening for colorectal cancer using any primary test modality should be launched in a public health programme with randomisation of the target population at the implementation phase.

Introduction

Screening for colorectal cancer using the faecal occult blood test has been shown to reduce mortality in four randomised screening trials.1 2 3 4 However, effectiveness at reducing mortality has not been shown routinely within a public health policy. Finland started an organised screening programme for colorectal cancer in 2004, with individuals randomised at the implementation phase of the programme. Although the effect on mortality will not be known for several years we monitored the programme using intermediate indicators. We estimated the sensitivity of screening in identifying unrecognised disease at three levels; the faecal occult blood test, the screening episode, and the entire programme. We also determined the benefits of the experimental design using randomisation at the implementation phase of the programme.

Methods

Health services in Finland are the responsibility of local municipalities. The implementation of the screening programme for colorectal cancer was started in September 2004 as a public health policy in 22 volunteer municipalities. Randomisation at individual level into screening and control groups was done at the time of the first screening round, when adults aged 60, 62, and 64 were sampled. The programme will gradually expand both geographically and by age to eventually cover adults aged 60 to 69.5 By 2006, the programme covered 161 of the 431 municipalities in Finland.

The overall design and coordination of the programme was the responsibility of the national Mass Screening Registry, a division of the Finnish Cancer Registry. One of the tasks of the Mass Screening Registry is to monitor and evaluate national screening programmes for cancer in Finland.

The practical organisation of the programme was based on centralised population sampling and invitation procedures. The population was sampled through the Population Register Centre, which keeps records including a unique personal identifier on every Finnish citizen. The identifier enables individual linkage to health registers, such as the cancer registry. People eligible for screening were defined on the basis of their home municipality and year of birth and sampled from the population register. After sampling, people were stratified into groups according to municipality, year of birth, and sex. Within each group individuals were alternately randomly allocated to screening or control groups. Those in the screening arm were invited to respond by post whereas those in the control arm were identified but not contacted. The control population received routine health services available in Finland.

A national screening centre was established in the city of Tampere at the local cancer society to deal with the invitations, responses, and recommendations for referrals and to analyse the faecal samples. Faecal occult blood test kits (Hemoccult; Beckman Coulter, USA) were posted to those offered screening along with a letter of invitation to participate in the programme and advice on how to take the sample. The kits were also returned by post. Dietary advice included avoiding raw meat, liver, food containing blood (for example, blood sausages) and large amounts of supplementary vitamin C (>250 mg/day) three days before and during sampling. After analysing the kits, the centre posted the findings to the respondents independently of the result. If any blood was detected in the sample, the respondent was given the contact details of their local municipal health centre. Simultaneously, a notification letter was sent to the person at the local health centre responsible for arranging a colonoscopy. Thereafter, diagnostic confirmation, treatment, and follow-up of people who had screened positive followed current national guidelines for normal care. Ninety per cent of these people had a colonoscopy. Of those remaining, some refused the procedure, some were not eligible (for example, they had recently had a colonoscopy), and a few had moved away.

The aim of screening for cancer is to detect the disease in the preclinical phase, when unrecognised disease can be detected by the screening test. We estimated sensitivity at three levels: the faecal occult blood test, the screening episode, and the entire programme.6 Test sensitivity measures how well the faecal occult blood test identifies the disease in the detectable preclinical phase, episode sensitivity also takes into account the diagnostic confirmation after a positive screening test result, and programme sensitivity indicates the proportion of patients with cancers in the total target population detected by screening. We corrected each of these estimates for bias caused by overdiagnosis and selective attendance.6

We estimated sensitivity using the incidence method.7 No direct observation of the disease in the detectable preclinical phase is available, even in principle, and therefore the estimate was based on the failure of screening. To estimate the proportion of false negative test results we measured failure by the incidence of interval cancer—that is, the incidence of colorectal cancer between two screening rounds—and compared this with the incidence of colorectal cancer in the control arm and in non-responders.

The formulas6 used for these three sensitivities were: test sensitivity=1–αP11/[P0–(1–α)P10], episode sensitivity=1–αP1/[P0–(1–α)P10], and programme sensitivity=episode sensitivity–episode sensitivity×P10(1–α)/P0, where α is the attendance rate, P0 is the annual incidence among controls (during the screening interval), P1 is the annual incidence between screens in people with a negative result during the screening episode, P10 is the annual incidence between screens in those not attending (non-responders), and P11 is the annual incidence between screens in people with negative test results.

We estimated the incidence rates for people invited to take part in the first round of screening and for controls from 2004 to 2006. Follow-up was through routine measures by the cancer registry. The latest linkage was run in June 2008, when cancers diagnosed in 2007 had almost been reported to the Finnish cancer registry. Follow-up started from the date of random sampling of the population, including linkage of postal addresses. The follow-up ended at the date of the next (second round) linkage of addresses, the date of diagnosis of colorectal cancer, or 31 December 2007 (the latest date with follow-up for cancer incidence), whichever came first. Screening is offered every second year, but owing to different policies and decision dates by municipality, the first screening interval varied between 1.5 and 2.7 years. In case linkage for the second round had not been done by the end of 2007 (those in the first round in 2006), the follow-up ended on 31 December 2007 (at the end of follow-up for cancer). In addition, 2461 people missed the second round of sampling (moved away or the municipality changed its policy), and in these individuals the follow-up ended two years from the start. We recorded the number of colorectal cancers diagnosed during follow-up. Patients with colorectal cancer already diagnosed before random sampling or at the first screen did not contribute to any follow-up time in the present analysis, neither did those patients for whom the date of diagnosis was the month of random sampling. We excluded those patients with cancer but with no follow-up time, as well as screen detected cancers, from the estimation of incidence of interval cancer.

Results

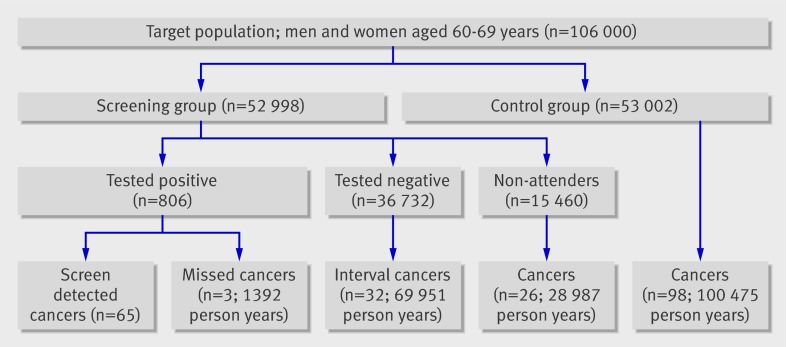

Overall, 106 000 adults were randomised in 2004-6: 52 998 to the screening arm and 53 002 to the control arm (table 1). Attendance was 70.8%, better in women than in men (78.1% v 63.3%). Of 806 people with a positive test result 65 were diagnosed as having cancer (figure). During a mean follow-up of 1.9 years 35 interval cancers and 26 cancers in non-responders were diagnosed (table 2). Of the interval cancers, 32 were in people who tested negative and three in those who tested positive but with a negative colonoscopy result. The number of colorectal cancers diagnosed in the control population was 98 during a mean follow-up of 1.9 years.

Table 1.

Number of people invited for screening, responders, and controls in Finnish organised screening programme for colorectal cancer, 2004-6

| Year and sex | No invited for screening | No of responders | Response rate (%) | No of controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004: | ||||

| Men | 2143 | 1464 | 68.3 | 2148 |

| Women | 2396 | 1925 | 80.3 | 2391 |

| Total | 4539 | 3389 | 74.7 | 4539 |

| 2005: | ||||

| Men | 11 646 | 7617 | 65.4 | 11 639 |

| Women | 11 916 | 9408 | 79.0 | 11 923 |

| Total | 23 562 | 17 025 | 72.3 | 23 562 |

| 2006: | ||||

| Men | 12 461 | 7546 | 60.6 | 12 462 |

| Women | 12 436 | 9557 | 76.8 | 12 435 |

| Total | 24 897 | 17 103 | 68.7 | 24 897 |

| Total: | ||||

| Men | 26 250 | 16 627 | 63.3 | 26 250 |

| Women | 26 748 | 20 890 | 78.1 | 26 752 |

| Overall total | 52 998 | 37 517 | 70.8 | 53 002 |

Flow chart of Finnish colorectal cancer screening programme. Screen detected cancers provide no follow-up time in current analysis

Table 2.

Cancers in responders, non-responders, and controls; person years; and incidence in Finnish organised screening programme for colorectal cancer, 2004-6

| Arm and sex | No of cancers | Person years | Incidence per 100 000 person years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Responders*: | |||

| Test negative: | |||

| Men | 13 | 30 787 | 42 |

| Women | 19 | 39 164 | 49 |

| Total | 32 | 69 951 | 46 |

| Episode negative: | |||

| Men | 15 | 31 643 | 47 |

| Women | 20 | 39 701 | 50 |

| Total | 35 | 71 344 | 49 |

| Non-responders | |||

| Men | 16 | 17 997 | 89 |

| Women | 10 | 10 990 | 91 |

| Total | 26 | 28 987 | 90 |

| Controls | |||

| Men | 51 | 49 707 | 103 |

| Women | 47 | 50 768 | 93 |

| Total | 98 | 100 475 | 98 |

*Sixty five screen detected cancers were excluded.

Incidence of colorectal cancer in the control population was 98 per 100 000 person years and the incidence of interval cancer in those with a negative result at first screening episode was 49 per 100 000 person years (table 2). About every second case of colorectal cancer in the detectable preclinical phase was identified by the faecal occult blood test (test sensitivity 54.6%; table 3). The incidence of cancer in the controls was somewhat higher in men than in women (103 v 93 per 100 000 person years), which was not true for interval cancers (42 v 49 per 100 000 person years). Only three interval cancers were diagnosed among those with a positive test result but no cancer at colonoscopy. Therefore episode sensitivity at 51.3% was close to test sensitivity. Despite a high attendance rate (70.8% overall) programme sensitivity remained low, at 37.5%.

Table 3.

Sensitivities in Finnish screening programme for colorectal cancer, 2004-6

| Indicator (%) | Men | Women | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test sensitivity | 61.8 | 47.8 | 54.6 |

| Episode sensitivity | 57.1 | 45.8 | 51.3 |

| Programme sensitivity | 39.0 | 36.0 | 37.5 |

Discussion

We found high attendance in the screening programme for colorectal cancer that was run as a public health policy in Finland. The faecal occult blood test was able to detect a major proportion (55%) of cancers in the detectable preclinical phase and more than one third (38%) in the total target population.

Only the faecal occult blood test has been evaluated for effect on mortality when screening for colorectal cancer.8 9 With screening every two years the reduction in mortality from colorectal cancer varies between 25% at 18 years of follow-up10 and 12% at eight years of follow-up.4 In one trial with a follow-up of 18 years, a 20% reduction in incidence of colorectal cancer was also seen.11 In light of these results several organisations recommend screening for colorectal cancer as a public health policy.12 Finland was, to the best of our knowledge, the first country to start a national organised screening programme, in 2004. In several other countries, pilot projects or regional programmes were started13 and in the United Kingdom a large scale pilot began in 2000.14 Spontaneous faecal occult blood testing is well established in the United States and in many central European countries.15

Public health policies that include screening are generally evaluated by non-experimental means. Such approaches are likely to result in inconclusive evidence, especially if the effect is expected to be small.16 Therefore a sensitive and unbiased design including randomisation at the implementation phase of the programme was the approach chosen in Finland.5

We investigated the sensitivity of the colorectal cancer screening programme at the level of the faecal occult blood test, the screening episode, and the entire programme. Traditionally, sensitivity has been regarded as an indicator of the test. Improvements in sensitivity have been proposed by introducing other tests, such as immunochemical faecal tests,17 18 19 with the potential for a higher specificity at the same analytical threshold as the guaiac based test used in Finland. Therefore, increased sensitivity using the immunochemical test would assume a lower value for the analytical threshold. Molecular markers identifying cancer DNA in stools, and endoscopic screening with sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy are new tests proposed to improve sensitivity.20 21 None of these, except for a small trial using sigmoidoscopy,22 were evaluated for their effect on mortality. Therefore routine screening with tests other than guaiac based faecal tests would not be evidence based and are not yet recommended.

Test sensitivity and episode sensitivity could be expected to be identical, because colonoscopy is considered the ideal investigation in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. This was not true, however, even if the sensitivities were close (54.6% and 51.3%). Health authorities in Finland and experts in many other countries expressed concern about sufficient capacity for colonoscopy when routine screening with the faecal occult blood test was planned.23 This was not a problem eventually as the 2% test positivity rate did not radically increase the need for resources. Instead, proper targeting may reduce the number of unnecessary colonoscopies in the future. That colonoscopy failed to detect cancer in some people who tested positive for faecal occult blood, leading to interval cancers, pinpoints the need for a higher quality service.

Attendance is a main determinant in the success of a screening programme. Compared with other countries24 and screening programmes for other primary sites,25 the response rate in Finland was high (70.8%), especially in women (78.1%). The sensitivity of the programme remained low, however, at 37.5% overall, similar in both sexes. It has been proposed that screening in women should be started at an older age than in men to give a similar yield.26 It is not clear whether using different target ages by sex would be feasible in practice.

Limitations

Follow-up in this study was for a mean 1.9 years (median 2.0 years), slightly less than one full screening interval. As reliable data on cancer incidence were available only until the end of 2007, some people randomised in 2006 had been followed-up for only part of the full interval at the end of follow-up in December 2007. However, the mean follow-up time for those starting in 2006 was 1.7 years. If anything, the completed follow-up data up to two years is likely to show a decrease rather than an improvement in the sensitivity estimates, since the incidence of interval cancer in the first interval is at its highest close to the second round.

Not all cancers diagnosed in Finland in 2007 had been reported to the Finnish cancer registry by the time of linkage in June 2008. We estimated the number of possible missing cases from the first screening round by comparing data on screen detected cases from the screening centre with the files of the Finnish cancer registry. No cases of colorectal cancer were unknown to the registry from the first screening round in 2004-6, with diagnostic confirmation done by the end of 2007.

Implications

The sensitivity of the Finnish screening programme for colorectal cancer at the first round was adequate even if relatively low. Two trials reported episode sensitivities only.1 3 The estimates were 49.5% and 44.2%. Although the analyses of the two trials are not totally comparable with ours, it seems that our episode (and test) sensitivities are slightly higher than those from the trials in the United Kingdom and Denmark. Furthermore, on the basis of the participation rates it seems that the sensitivity of our programme is somewhat better than that of these trials. Thus, programme sensitivity in Finland was sufficient to justify continuation of the programme.

The design of the Finnish programme allows for specific changes such as the screening interval, the primary test, or the age at starting screening if that turns out to be reasonable later on. Regardless, a rigorous design is a prerequisite for evaluating the process and outcome—that is, to estimate sensitivity and subsequently the effectiveness of the programme on the number of deaths prevented from colorectal cancer, which is likely to remain relatively small. Thus routine screening for colorectal cancer using any primary screening test should only be launched as an organised programme, including randomisation at the implementation phase.

What is already known on this topic

Randomised controlled trials using faecal occult blood tests to screen for colorectal cancer have shown a reduction in mortality in those invited compared with controls

Several countries have started screening, many as spontaneous activity or non-organised screening

Many organisations recommend screening through public programmes although no conclusive evidence on their effectiveness is available

What this study adds

Four of 10 cases of colorectal cancer were detected by a public screening programme in Finland

This programme provides a model on how to implement a new screening programme using the principles of experimental design with randomisation to obtain conclusive evidence on effectiveness

Definitions of sensitivities

Test sensitivity—measures how much of the disease the screening test is able to identify in those screened

Episode sensitivity—measures how much of the disease the screening test and diagnostic confirmation combined are able to identify in those screened

Programme sensitivity—measures how much of the disease from invitation to diagnostic confirmation screening is able to identify in the total target population (those screened and non-responders)

We thank Minna Merikivi and Hilkka Laasanen from the Finnish cancer registry for coding and linking cases of colorectal cancer among the study population, the steering committee of the colorectal cancer screening programme at the Cancer Society of Finland, and the steering committee for screening of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland for advice and administrative support in the planning of the programme.

Contributors: NM and MH designed the programme and analysed the data. TO and OM ran the screening centre. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version for publication. NM is guarantor.

Funding: The Finnish Cancer Foundation established a scientific post at the Mass Screening Registry The screening programme was funded by municipalities within the standard primary healthcare budget. The evaluation and analysis was done at the Finnish Cancer Registry.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health gave permission for implementation of the programme and registration of data in December 2003.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Cite this as: BMJ 2008;337:a2261

References

- 1.Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jorgensen OD, Sondergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet 1996;348:1467-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, Snover DC, Bradley GM, Schuman LM, et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota colon cancer control study. N Engl J Med 1993;328:1365-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, Moss SM, Amar SS, Balfour TW, et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet 1996;348:1472-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kewenter J, Brevinge H, Engaras B, Haglind E, Ahren C. Results of screening, rescreening, and follow-up in a prospective randomized study for detection of colorectal cancer by fecal occult blood testing. Results for 68,308 subjects. Scand J Gastroenterol 1994;29:468-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malila N, Anttila A, Hakama M. Colorectal cancer screening in Finland: details of the national screening programme implemented in Autumn 2004. J Med Screen 2005;12:28-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hakama M, Auvinen A, Day NE, Miller AB. Sensitivity in cancer screening. J Med Screen 2007;14:174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.IARC Handbooks of cancer prevention. Vol 7. Breast cancer screening. Lyon: IARC, 2002.

- 8.Towler B, Irwig L, Glasziou P, Kewenter J, Weller D, Silagy C. A systematic review of the effects of screening for colorectal cancer using the faecal occult blood test, hemoccult. BMJ 1998;317:559-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scholefield JH, Moss S, Sufi F, Mangham CM, Hardcastle JD. Effect of faecal occult blood screening on mortality from colorectal cancer: results from a randomised controlled trial. Gut 2002;50:840-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandel JS, Church TR, Ederer F, Bond JH. Colorectal cancer mortality: effectiveness of biennial screening for fecal occult blood. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:434-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandel JS, Church TR, Bond JH, Ederer F, Geisser MS, Mongin SJ, et al. The effect of fecal occult-blood screening on the incidence of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Council recommendation of 2 December 2003 on cancer screening. Official J Eur Union 2003;2003/878/EC(L327):34-8.

- 13.Benson VS, Patnick J, Davies AK, Nadel MR, Smith RA, Atkin WS. Colorectal cancer screening: a comparison of 35 initiatives in 17 countries. Int J Cancer 2008;122:1357-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steele RJ, Parker R, Patnick J, Warner J, Fraser C, Mowat NA, et al. A demonstration pilot trial for colorectal cancer screening in the United Kingdom: a new concept in the introduction of healthcare strategies. J Med Screen 2001;8:197-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hakama M, Hoff G, Kronborg O, Pahlman L. Screening for colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol 2005;44:425-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hakama M, Pukkala E, Soderman B, Day N. Implementation of screening as a public health policy: issues in design and evaluation. J Med Screen 1999;6:209-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allison JE, Sakoda LC, Levin TR, Tucker JP, Tekawa IS, Cuff T, et al. Screening for colorectal neoplasms with new fecal occult blood tests: update on performance characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99:1462-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allison JE, Tekawa IS, Ransom LJ, Adrain AL. A comparison of fecal occult-blood tests for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med 1996;334:155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guittet L, Bouvier V, Mariotte N, Vallee JP, Arsene D, Boutreux S, et al. Comparison of a guaiac based and an immunochemical faecal occult blood test in screening for colorectal cancer in a general average risk population. Gut 2007;56:210-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahlquist DA. Molecular stool screening for colorectal cancer. Using DNA markers may be beneficial, but large scale evaluation is needed. BMJ 2000;321:254-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoff G, Bretthauer M. The science and politics of colorectal cancer screening. PLoS Med 2006;3(1):e36; quiz e104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoff G, Thiis-Evensen E, Grotmol T, Sauar J, Vatn MH, Moen IE. Do undesirable effects of screening affect all-cause mortality in flexible sigmoidoscopy programmes? Experience from the Telemark polyp study 1983-1996. Eur J Cancer Prev 2001;10:131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scholefield JH, Moss SM. Faecal occult blood screening for colorectal cancer. J Med Screen 2002;9:54-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.UK Colorectal Cancer Screening Pilot Group. Results of the first round of a demonstration pilot of screening for colorectal cancer in the United Kingdom. BMJ 2004;329:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.IARC Handbooks of cancer prevention. Cervix cancer screening. Lyon: IARC Press, 2005.

- 26.Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Arndt V, Haug U. Gender differences in colorectal cancer: implications for age at initiation of screening. Br J Cancer 2007;96:828-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]