Abstract

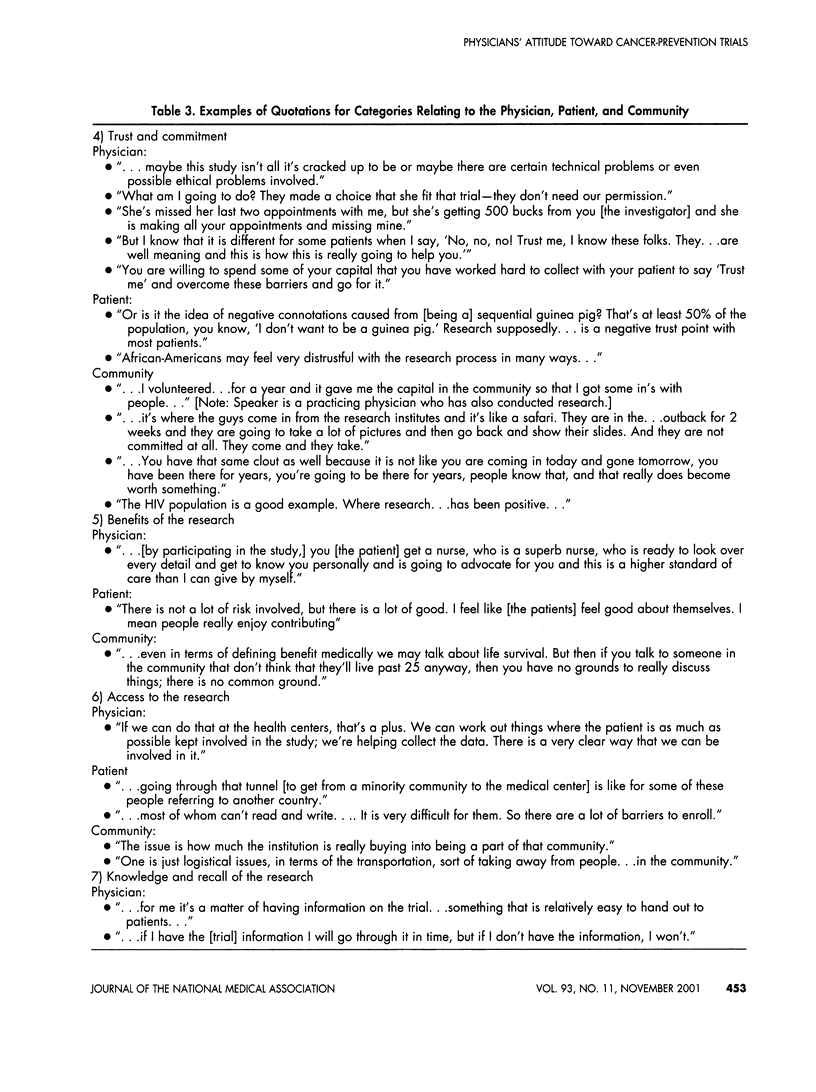

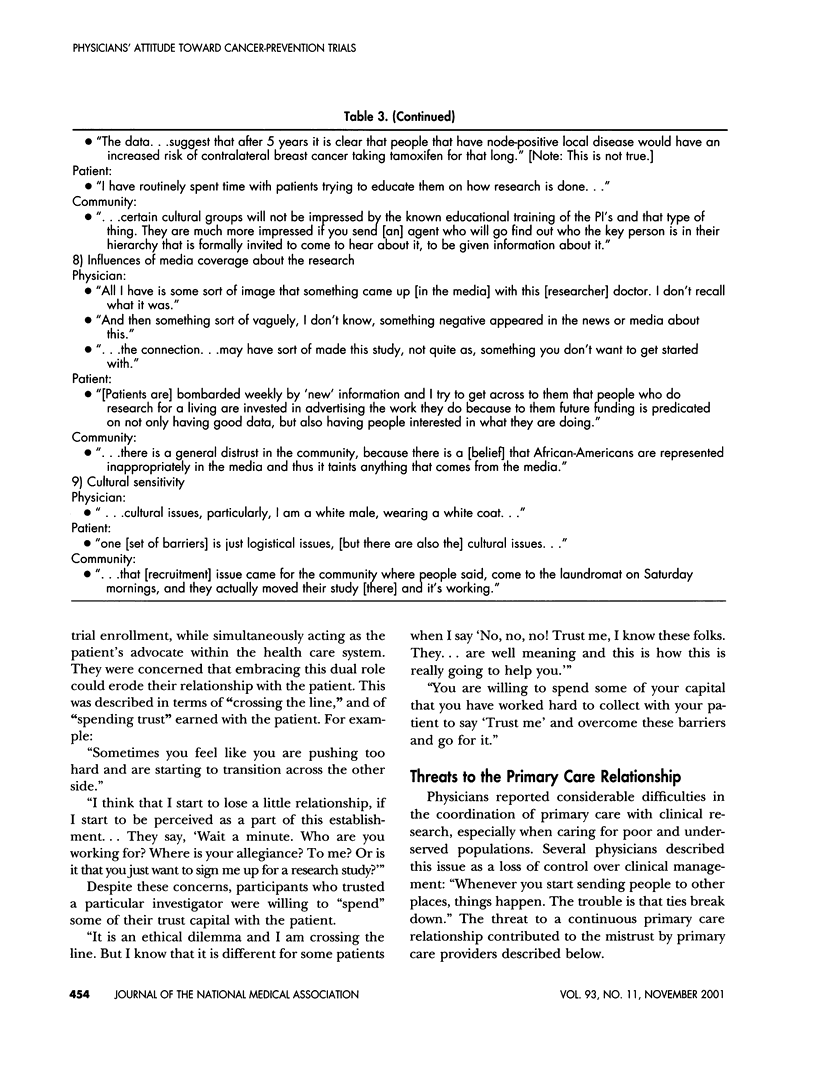

PURPOSE: Recruitment of low-income and minority women to cancer-prevention trials requires a joint effort from specialists and primary care providers. We sought to assess primary care providers' attitudes toward participating in cancer-prevention trial recruitment. PROCEDURES: We conducted a focus group with seven Boston-based primary care providers serving low-income and minority women. Providers discussed knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding their role in recruitment to prevention trials. FINDINGS: A qualitative analysis of the focus group transcript revealed nine categories. Three categories related specifically to the primary care physician: 1) the dual role physicians play as advocates for both patient and research; 2) threats to maintaining the primary care relationship; and 3) general philosophy toward prevention. An additional six categories could be subdivided as they apply to the primary care physician, the patient, and the community: 4) trust/commitment; 5) benefits of the research; 6) access to the research; 7) knowledge and recall of the research; 8) influences of media coverage about the research; and 9) cultural sensitivity. CONCLUSIONS: Investigators conducting cancer-prevention trials must address the concerns of primary care physicians to optimize recruitment of subjects- especially low-income and minority women-into trials.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Corbie-Smith G. The continuing legacy of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study: considerations for clinical investigation. Am J Med Sci. 1999 Jan;317(1):5–8. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton P. Is there still too much extrapolation from data on middle-aged white men? JAMA. 1990 Feb 23;263(8):1049–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresser R. Wanted. Single, white male for medical research. Hastings Cent Rep. 1992 Jan-Feb;22(1):24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frayne S. M., Burns R. B., Hardt E. J., Rosen A. K., Moskowitz M. A. The exclusion of non-English-speaking persons from research. J Gen Intern Med. 1996 Jan;11(1):39–43. doi: 10.1007/BF02603484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick P. B., Harris Y., Burnett B., Bonecutter F. J. The recruitment triangle: reasons why African Americans enroll, refuse to enroll, or voluntarily withdraw from a clinical trial. An interim report from the African-American Antiplatelet Stroke Prevention Study (AAASPS). J Natl Med Assoc. 1998 Mar;90(3):141–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurwitz J. H., Col N. F., Avorn J. The exclusion of the elderly and women from clinical trials in acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1992 Sep 16;268(11):1417–1422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris Y., Gorelick P. B., Samuels P., Bempong I. Why African Americans may not be participating in clinical trials. J Natl Med Assoc. 1996 Oct;88(10):630–634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunninghake D. B., Darby C. A., Probstfield J. L. Recruitment experience in clinical trials: literature summary and annotated bibliography. Control Clin Trials. 1987 Dec;8(4 Suppl):6S–30S. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(87)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaluzny A., Brawley O., Garson-Angert D., Shaw J., Godley P., Warnecke R., Ford L. Assuring access to state-of-the-art care for U.S. minority populations: the first 2 years of the Minority-Based Community Clinical Oncology Program. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993 Dec 1;85(23):1945–1950. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.23.1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovato L. C., Hill K., Hertert S., Hunninghake D. B., Probstfield J. L. Recruitment for controlled clinical trials: literature summary and annotated bibliography. Control Clin Trials. 1997 Aug;18(4):328–352. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(96)00236-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour E. G. Barriers to clinical trials. Part III: Knowledge and attitudes of health care providers. Cancer. 1994 Nov 1;74(9 Suppl):2672–2675. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941101)74:9+<2672::aid-cncr2820741815>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouton C. P., Harris S., Rovi S., Solorzano P., Johnson M. S. Barriers to black women's participation in cancer clinical trials. J Natl Med Assoc. 1997 Nov;89(11):721–727. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinn V. W. Women's health research. Prescribing change and addressing the issues. JAMA. 1992 Oct 14;268(14):1921–1922. doi: 10.1001/jama.268.14.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poses R. M., Isen A. M. Qualitative research in medicine and health care: questions and controversy. J Gen Intern Med. 1998 Jan;13(1):32–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00005.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson N. L. Clinical trial participation. Viewpoints from racial/ethnic groups. Cancer. 1994 Nov 1;74(9 Suppl):2687–2691. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941101)74:9+<2687::aid-cncr2820741817>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt R. A., Hart L. G., Baldwin L. M., Chan L., Schneeweiss R. The generalist role of specialty physicians: is there a hidden system of primary care? JAMA. 1998 May 6;279(17):1364–1370. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone V. E., Mauch M. Y., Steger K. A. Provider attitudes regarding participation of women and persons of color in AIDS clinical trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998 Nov 1;19(3):245–253. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199811010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson C. K. Representation of American blacks in clinical trials of new drugs. JAMA. 1989 Jan 13;261(2):263–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson G. M., Ward A. J. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: toward a participant-friendly system. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995 Dec 6;87(23):1747–1759. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waitzkin H. On studying the discourse of medical encounters. A critique of quantitative and qualitative methods and a proposal for reasonable compromise. Med Care. 1990 Jun;28(6):473–488. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199006000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger N. K. Exclusion of the elderly and women from coronary trials. Is their quality of care compromised? JAMA. 1992 Sep 16;268(11):1460–1461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu K., Hunter S., Bernard L. J., Payne-Wilks K., Roland C. L., Levine R. S. Recruiting elderly African-American women in cancer prevention and control studies: a multifaceted approach and its effectiveness. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000 Apr;92(4):169–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Sadr W., Capps L. The challenge of minority recruitment in clinical trials for AIDS. JAMA. 1992 Feb 19;267(7):954–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]