Abstract

Delayed T-cell recovery is an important complication of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT). We demonstrate in murine models that donor BM-derived T cells display increased apoptosis in recipients of allogeneic BMT with or without GVHD. Although this apoptosis was associated with a loss of Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL expression, allogeneic recipients of donor BM deficient in Fas-, tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)- or Bax-, or BM-overexpressing Bcl-2 or Akt showed no decrease in apoptosis of peripheral donor-derived T cells. CD44 expression was associated with an increased percentage of BM-derived apoptotic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Transplantation of RAG-2-eGFP–transgenic BM revealed that proliferating eGFPloCD44hi donor BM-derived mature T cells were more likely to undergo to apoptosis than nondivided eGFPhiCD44lo recent thymic emigrants in the periphery. Finally, experiments using carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester–labeled T cells adoptively transferred into irradiated syngeneic hosts revealed that rapid spontaneous proliferation (as opposed to slow homeostatic proliferation) and acquisition of a CD44hi phenotype was associated with increased apoptosis in T cells. We conclude that apoptosis of newly generated donor-derived peripheral T cells after an allogeneic BMT contributes to delayed T-cell reconstitution and is associated with CD44 expression and rapid spontaneous proliferation by donor BM-derived T cells.

Introduction

Immune deficiency after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) is a major cause of posttransplantation morbidity and mortality. In contrast to the early recovery of innate immunity (myeloid and NK cells), all recipients of allogeneic BMT experience various degrees of posttransplantation deficiency in B- and T-cell reconstitution.1,2 In particular, T-cell deficiency in adult recipients of a T cell–depleted (TCD) or unrelated BMT can negatively affect the clinical outcome of transplantation by increasing the risk of infection or malignant relapse.1,3 Posttransplantation T-cell recovery is slower in adult BMT recipients than in pediatric BMT recipients, most probably because of a decreased capacity for thymic regeneration after puberty.3,4

Naive T cells can expand in lymphopenic recipients, and this homeostatic T-cell proliferation contributes to the regulation of the size of the T-cell pool.5,6 Homeostatic proliferation is controlled by cytokines (including interleukin 7 [IL-7] and IL-15) and interactions of the T-cell receptor with self-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules.7–9 Studies in experimental BMT models have shown that homeostatic proliferation of T cells contributes to peripheral T-cell reconstitution after allogeneic BMT in addition to de novo T-cell generation in the thymus of the recipient.10

However, in addition to potential defects in posttransplantation thymopoiesis and impaired homeostatic proliferation, 2 clinical studies have suggested that peripheral apoptosis may also retard peripheral T-cell reconstitution after BMT.11,12 We have previously demonstrated that administration of IL-7 and IL-15 can decrease posttransplantation peripheral T-cell apoptosis10,13 and increase Bcl-2 and BCL-XL levels in T cells13–18. However, the underlying mechanisms of increased peripheral posttransplantation T-cell apoptosis remain poorly understood.

T-cell apoptosis can occur via 2 known pathways: (1) agonism of death receptors, such as the Fas (CD95)/Fas ligand (CD95L) pathway, important for the regulation of activation induced cell death, and (2) the loss of trophic factors (eg, IL-7 or IL-15) or nutrient deprivation,19 leading to a shift in balance toward the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members such as Bax and Bad.20

In this study, we demonstrate for the first time, in murine experimental bone marrow transplantation models, that newly generated donor T cells in BMT recipients are particularly susceptible to peripheral T-cell apoptosis and that this process is strongly correlated with expression of the activation marker CD44 and with rapid spontaneous proliferation.

Methods

Bone marrow transplantation

Female C57BL/6 (B6, H-2Kb), C3FeB6F1 (H-2Kb/k), LP (H-2Kb), BALB/c (H-2Kd), and C57BL/6 (H-2Kb Ly5.1+) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). For some experiments, RAG2-eGFP– transgenic mice (FVB, H-2K) were kindly provided Dr Michel Nussenzweig (Rockefeller University, New York, NY). Mice used in BMT experiments were between 8 and 10 weeks of age. BMT protocols were approved by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Bone marrow (BM) cells were removed aseptically from femurs and tibias and TCD by incubation with anti-Thy 1.2 antibody for 30 minutes at 4°C, followed by incubation with Low-TOX-M rabbit complement (Cedarlane Laboratories, Hornby, ON) for 40 minutes at 37°C, or alternatively via anti-CD5 magnetic bead depletion (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Typical levels of contaminating T cells after complement depletion ranged from 0.1% to 0.2% of all bone marrow leukocytes.

For selected experiments, lineage depletion of BM was performed with StemSep (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC). Lineage depletion resulted in a leukocyte population that was ∼95% lineage-negative.

Splenic T cells were obtained either by purification over a nylon wool column or by positive selection with anti-CD5 antibodies conjugated to magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells (5 × 106 BM cells with or without splenic T cells) were resuspended in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) and transplanted by tail vein infusion (0.25-mL total volume) into lethally irradiated recipients on day 0. On day 0 before transplantation, recipients received 850 to 1300 cGy of total body irradiation (strain-dependent) from a 137Cs source as a split dose with a 3-hour interval between doses to reduce gastrointestinal toxicity. Mice were housed in sterilized microisolator cages; they received normal chow and autoclaved hyperchlorinated drinking water, pH 3.0.

Reagents and antibodies

Anti-murine CD16/CD32 FcR block (2.4G2) and all of the following fluorochrome-labeled antibodies against murine antigens were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA): Ly-9.1 (30C7), CD3 (145-2C11), CD4 (RM4-5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD62L (MEL-14), CD122 (TM-B1), CD44 (IM7), CD45R/B220 (RA3-6B2), NK1.1 (PK136), CD11b (M1/70), CD25 (PC61), Bcl-2 (3F11), BCL-XL (44) T-cell receptor (TCR) αβ (H57-597), H2-Kb annexin V, isotype controls; rat IgG2a-κ (R35-95), rat IgG2a-λ (B39-4), rat IgG2b-κ(A95-1), rat IgG1-κ(R3-34), hamster IgG-group 1-κ(A19-3), hamster IgG-group 1-λ(Ha4/8), streptavidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate, streptavidin-phycoerythrin (PE), and streptavidin-peridinin chlorophyll protein. Caspase 8 and 9 fluorometric kit, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI), and carboxyfluoroscein succinidyl ester (CFSE) were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Tissue-culture medium consisted of RPMI-1640 medium or DMEM supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mmol/L l-glutamine.

CFSE labeling

Cells were labeled with CFSE as described previously.21 In brief, purified T cells were incubated with CFSE at a final concentration of 2.5 μM in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37°C for 15 minutes. Cells were then washed 3 times with PBS before intravenous injection.

Preparation of purified stem cells

Bone marrow from donor mice was obtained as described above, and cells were stained with an antibody cocktail to a complete panel of lineage markers. Lineage-positive cells were then magnetically depleted with StemSep (StemCell Technologies) per the manufacturer's protocols. Resulting lineage-negative cells were stained with anti-Sca-1 and c-Kit antibodies and lineage−Sca-1+c-kit+ cells were obtained by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS; MoFlo; Dako Colorado, Fort Collins, CO) as described previously.22 Post-sort purities were more than 96% lineage−Sca-1+c-kit+ cells.

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells were washed in FACS buffer (PBS with 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% sodium azide) and 106 cells/mL were incubated for 15 minutes at 4°C with CD16/CD32 FcR block. Subsequently, cells were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with antibodies and washed twice with FACS buffer. The stained cells were resuspended in FACS buffer and analyzed on a FACSCalibur, LSR I, or LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) with CellQuest Pro, DiVA (BD Biosciences), or FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

Analysis of apoptosis with annexin V

Annexin V staining was used to determine apoptotic cells per the manufacturer's recommended protocol (BD Biosciences). Cells were also stained with DAPI to exclude dead cells.

Intracellular staining

Splenocytes were washed and stained with primary (surface) fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies. Cells were then fixed and permeabilized with the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit (BD Biosciences) and subsequently stained with intracellular antibodies.

Intracellular staining-II

For some intracellular stainings, an alternate protocol was used. Splenocytes were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 minutes at 37°C, pelleted by centrifugation (350g for 5 minutes), resuspended in 90% methanol while vortexing, and incubated on ice for 30 minutes. Samples were washed 3 times with PBS and then incubated for 15 minutes at 4°C with CD16/CD32 FCR block (clone 2.4G2). Subsequently, cells were incubated in 50 μL FACS buffer for 20 minutes at 4°C with cell-surface and intracellular antibodies.

Statistics

All values are expressed as mean plus or minus SEM. Statistical comparison of experimental data were performed with the nonparametric unpaired Mann-Whitney U test. A P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

T-cell reconstitution is delayed by peripheral T-cell apoptosis in recipients of an allogeneic TCD-BMT

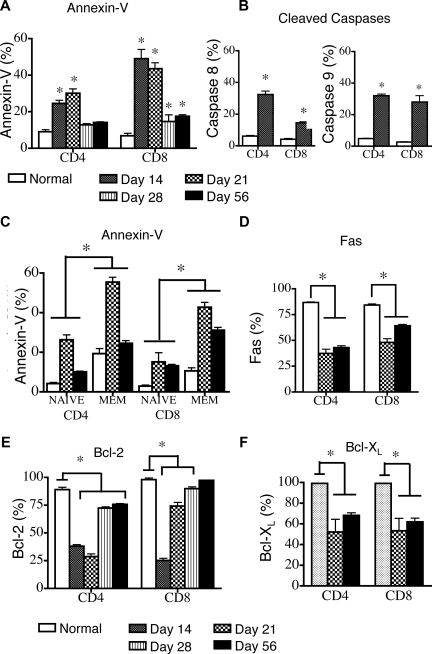

We used a clinically relevant, TCD allogeneic BMT model (B6→LP/J; H-2Kb) with a disparity in minor histocompatibility antigens to examine peripheral T-cell apoptosis after allogeneic BMT. A kinetic analysis in recipients of TCD-BMT revealed that compared with animals that did not receive transplants, the percentage of apoptotic cells, as measured by annexin-V, was significantly increased in both donor-derived CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations, specifically in the first 3 weeks after BMT (Figure 1A). By day 56 after BMT, CD4+ T-cell apoptosis had returned to normal levels, whereas CD8+ T-cell apoptosis remained slightly elevated. Elevated percentages of apoptotic cells early after transplantation, with return to normal or near-normal levels by day 56 after BMT correlates with profound lymphopenia in the first 3 weeks after transplantation and a gradual recovery of peripheral CD4 and CD8 T cells over the next several weeks (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Figure 1.

Peripheral apoptosis delays T-cell reconstitution after allogeneic TCD-BMT. Lethally irradiated (1100 cGy) 8- to 10-week-old LP mice were transplanted with 5 × 106 TCD B6 BM and harvested at various intervals after transplantation. LP mice that did not receive transplants were also analyzed. Values represent mean (± SEM). n = 5-10 mice per group, results from 2 or more independent experiments. Donor B6 cells were gated as Ly9.1-negative because of the allelic difference between the B6 and LP strains. (A) Splenic donor T cells were gated as Ly9.1− cells, and apoptosis was determined by annexin-V staining on days 14, 21, 28, and 56 after transplantation and in control animals that did not receive transplants. (B) Cleaved caspase 8 and 9 activity in donor Ly9.1− T cells and control animals that did not receive transplants was determined on day 14 after transplantation. (C) Donor-derived Ly9.1− naive (CD44lo) and effector/memory (CD44hi) T cells were analyzed by annexin-V staining on days 14 and 56 after transplantation. Control animals that did not receive transplants were also analyzed. (D) Cell surface Fas expression on donor-derived Ly9.1− splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was determined at days 21 and 56 after transplantation. Control animals that did not receive transplants were also analyzed. (E) Intracellular levels of Bcl-2 in donor Ly9.1− CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were determined on days 14, 21, 28, and 56 after transplantation. Control animals that did not receive transplants were also analyzed. (F) Intracellular levels of Bcl-XL in donor Ly9.1− CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were determined at days 14 and 56 after transplantation. Control animals that did not receive transplants were also analyzed.

We verified an increase in peripheral T-cell apoptosis by measuring levels of cleaved caspases. We found increased percentages of donor-derived splenic T cells with cleaved caspase 8 and 9 (Figure 1B) compared with control animals that did not receive transplants.

Further analysis of naive and effector/memory T cells, as determined by CD44 expression, revealed that CD44hi T cells contained a significantly higher percentage of apoptotic cells in both animals that did and did not receive transplants compared with CD44lo naive T cells (Figure 1C). However, apoptosis was elevated in both CD44lo and CD44hi T cells in animals that received transplants compared with those that did not.

The percentages of apoptotic CD44hi CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were significantly higher on day 21 than on day 56 (55.4% ± 3.0% vs 24.5% ± 1.4%, P < .05 and 42.7% ± 2.4% vs. 31.1% ± 1.4%, P < .05, respectively). It is noteworthy that the percentages of apoptotic CD44loCD8+ T cells were similar on days 21 and 56 after BMT (13.1% ± 0.7% and 15.1 %± 4.6%, respectively), whereas the percentage of apoptotic CD44loCD4+ T cells was significantly higher on day 21 than on day 56 (26.4% ± 3.2% vs 10.1% ± 0.3%).

To assess the roles of activation-induced cell death versus trophic factor withdrawal or nutrient loss in posttransplantation T-cell apoptosis, we examined the expression levels of Fas, Bcl-2, and Bcl-XL in donor-derived T cells after transplantation. It is noteworthy that the number of T cells that expressed Fas was lower in BMT recipients at days 21 and 56 than in mice that did not receive transplants (Figure 1D).

The percentage of donor-derived T cells that expressed the antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL was significantly decreased in the first weeks after BMT in both CD4 and CD8 T-cell populations compared with T cells in mice that did not receive transplants (Figure 1E,F). The percentage of Bcl-2–expressing CD8+ T cells returned to normal levels by day 56 after BMT, whereas the percentage of Bcl-2–expressing CD4+ T cells remained low even at this time point. In addition, the percentages of Bcl-XL–expressing T cells were decreased at days 14 and 56 after BMT (Figure 1F) compared with control animals that did not receive transplants.

We also evaluated T-cell apoptosis in recipients of syngeneic BMT. In these experiments, we observed a increase in DAPI−annexin V+ apoptotic cells (especially of CD8+ T cells) at day 21 after transplantation (13.2% ± 0.8% for CD4+ T cells and 28.3% ± 1.1% for CD8+ T cells) compared with corresponding populations in control B6 mice that did not receive transplants, although percentages of apoptotic cells were still significantly lower than that of donor peripheral T cells in allogeneic BMT. However, by day 50, levels of T-cell apoptosis had returned to completely normal levels (data not shown). Again, further subset analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells revealed that CD44hi cells had a particularly high level of apoptosis (25.0% ± 1.3% and 25.2% ± 1.1% respectively).

We conclude that peripheral T-cell apoptosis is significantly increased in TCD-BMT recipients after transplantation and correlates with the expression of CD44, and decreased levels of the antiapoptotic molecules Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL.

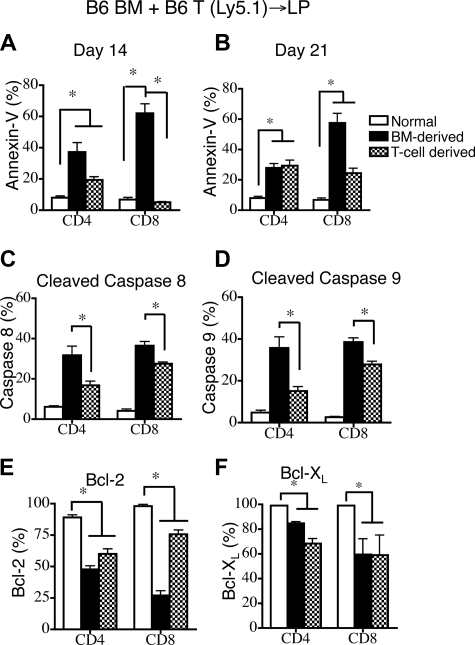

GVHD increases donor BM-derived T-cell apoptosis

Thymopoiesis and T-cell reconstitution after BMT are known to be severely suppressed in patients with GVHD.10,23,24 To assess the impact of GVHD on peripheral T-cell apoptosis in allogeneic BMT, we added congenic donor T cells (B6 Ly5.1) to the TCD allograft. This allowed us to differentiate among donor BM-derived T cells (Ly9.1−CD45.1−), infused alloreactive donor T cells (Ly9.1−CD45.1+), and residual host T cells (Ly9.1+CD45.1−). We found that the infused donor T cell–derived population expanded early after BMT and represented more than 75% of all CD4+ T cells by day 14 and CD8+ T cells by day 7 after BMT (Figure S2A). Mice receiving donor T cells exhibited significant weight loss but relatively little mortality (0%-10%) after transplantation (Figure S2B).

Upon evaluating T-cell apoptosis in the periphery, we observed that the highest percentages of apoptotic cells, as measured by annexin V staining (Figure 2A,B) and levels of cleaved caspases 8 and 9 (Figure 2C,D) were found in the donor BM-derived T cells. However, apoptosis in alloreactive T cells was also elevated compared with animals that did not receive transplants, though to a lesser extent (Figure 2A-D). The percentages of cells expressing Bcl-2 or Bcl-XL were decreased in both donor BM-derived T cells and infused (alloreactive) donor T cells compared with T cells from mice that did not receive transplants (Figure 2E,F).

Figure 2.

GVHD exacerbates donor BM-derived peripheral T-cell apoptosis in recipients of allogeneic T cell–replete BMT. Lethally irradiated (1100 cGy) LP mice were transplanted with 5 × 106 TCD B6 Ly5.2+ BM and 0.5 × 106 B6 Ly5.1+ T cells. Values represent mean (± SEM). n = 5-10 mice per group, combined from 2 or more independent experiments. (A,B) Apoptosis of donor BM-derived and infused T cell–derived populations was determined on days 14 and 21 after transplantation by annexin-V staining. Donor cells were all negative for Ly9.1; donor BM was Ly5.2+ and donor T cells were Ly5.1+. B6 mice that did not receive transplants were analyzed as the control group. (C,D) Cleaved caspase 8 and 9 levels in donor BM-derived and infused T cell–derived populations (gated as in A,B) were measured on days 14 and 21 after transplantation. LP mice that did not receive transplants were also analyzed. (E,F) Intracellular Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL levels were determined in donor BM-derived and infused T cell–derived populations (gated as in A,B) were measured on days 14 and 21 after transplantation. LP mice that did not receive transplants were also analyzed.

We conclude that donor BM-derived peripheral T cells contain a higher percentage of apoptotic cells than alloreactive T cells in BMT recipients with GVHD. This sensitivity to apoptosis correlates with a decrease in the expression of the antiapoptotic molecules Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL.

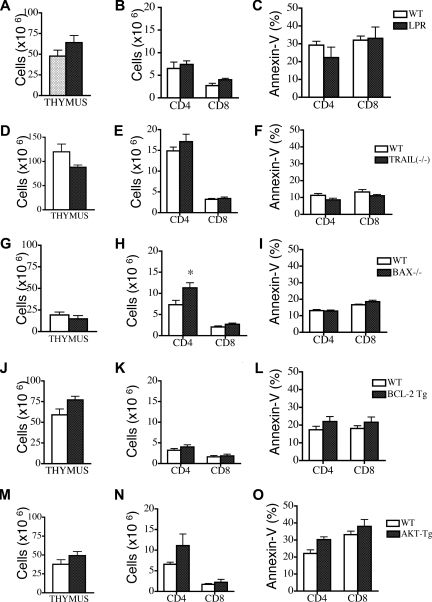

Deficiency of Fas, TRAIL, or Bax or overexpression of Bcl-2 or Akt cannot individually modulate peripheral T-cell apoptosis after allogeneic BMT

Having demonstrated the particular susceptibility of donor BM-derived T cells to peripheral apoptosis after allogeneic BMT and outlined potential correlations with the levels of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members, we used Fas-, tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)–, and Bax-deficient mice and Bcl-2– and Akt- transgenic mice as BM donors in our allogeneic TCD-BMT experiments to determine whether any of these molecules were directly involved as regulators of posttransplantation T-cell apoptosis.

We first used Fas-deficient lpr mice as BM donors and compared them with wild-type (WT) B6 donors. Although we found increased thymopoiesis in recipients of Fas-deficient TCD-BM, there was no difference in peripheral T-cell numbers or apoptosis between recipients of WT and Fas-deficient BM (Figure 3A-C). We also evaluated the effects of Fas-deficient BM on donor BM-derived T-cell apoptosis in recipients with GVHD. These recipients received either Fas deficient BM or WT BM in addition to WT T cells. Again, we noted a slight increase in thymopoiesis in the recipients of Fas-deficient BM group but no differences in peripheral T-cell numbers or apoptosis (Figure S3A-C). We next analyzed the effects of TRAIL−/− donor TCD-BM and found no differences in thymic cellularity, peripheral T-cell numbers, and apoptosis compared with recipients of WT TCD BM (Figure 3D-F).

Figure 3.

Deficiency in Fas, TRAIL, or Bax or overexpression of Bcl-2 and Akt cannot modulate peripheral T-cell apoptosis in recipients of allogeneic TCD-BMT. Lethally irradiated (1100 cGy) LP or (1300 cGy) C3FeB6F1 mice were transplanted either with 5 × 106 TCD B6 BM (WT) or TCD BM from B6 background Fas-, Bax-, and TRAIL-deficient or Bcl-2– and Akt-transgenic mice. All recipients were analyzed on day 28 after transplantation. Values represent mean (± SEM). n = 5-15 mice per group. (A-O) Thymic cellularity, numbers of peripheral donor-derived CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and levels of peripheral T-cell apoptosis were determined. Donor cells were defined as Ly9.1− cells.

We followed up by analyzing Bcl-2 family members and Akt/PKB, proteins involved in T-cell apoptosis secondary to trophic factor withdrawal and nutrient loss. Evaluation of the role of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bax25,26 revealed no difference in posttransplantation thymic cellularity in recipients of Bax−/− TCD-BM versus WT TCD-BM (Figure 3G). Although we observed a significant increase in peripheral CD4+ T-cell counts, there were no differences in the percentage of apoptotic peripheral T cells (Figure 3H,I).

We then performed allogeneic TCD-BMT experiments with TCD-BM from Bcl-2–transgenic (Bcl-2 Tg) mice27 and Akt- transgenic mice (Akt-Tg).28 Recipients of Bcl-2 Tg TCD-BM had increased thymic cellularity and numbers of thymic subpopulations at day 28 after BMT (Figure 3J and data not shown), but peripheral T-cell numbers and apoptosis were comparable with recipients of WT TCD-BM (Figure 4K,L). We noted similar results in recipients of Bcl-2 Tg allografts with GVHD: increased thymopoiesis but no effect on peripheral T-cell numbers and apoptosis (Figure S3D-F). Finally, our analyses of Akt-Tg TCD-BM showed no effects on posttransplantation thymic cellularity, peripheral T-cell numbers, and apoptosis (Figure 3M-O). We conclude that although there was a modest effect of Bax deficiency on peripheral posttransplantation T-cell numbers, Fas, TRAIL, Bax, Bcl-2, or Akt/PKB are individually insufficient to affect posttransplantation T-cell apoptosis.

Figure 4.

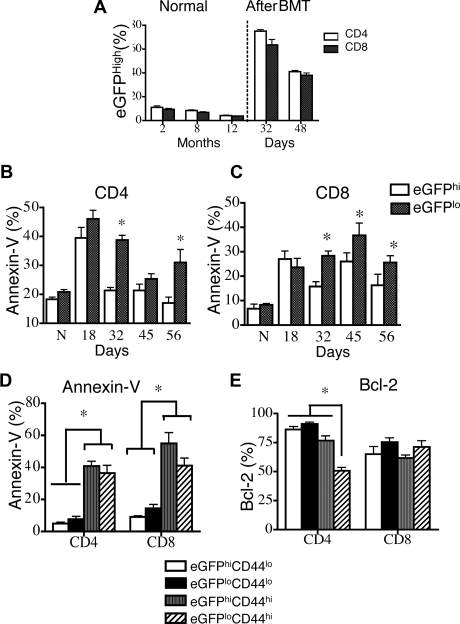

Recent thymic emigrants and CD44lo T cells are less sensitive to peripheral apoptosis. Lethally irradiated (850 cGy) 8- to 10-week-old BALB/c mice were transplanted with 5 × 106 TCD Rag2-eGFP Tg BM. n = 5. DATA are representative of 1 of 3 independent experiments. (A) Percentages of eGFPhi splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in 2-, 8-, and 12-month-old RAG2-eGFP animals that did not receive transplants, and percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ donor-derived eGFPhi splenic T cells in animals that received transplants at days 32 and 48 were determined. Donor cells were defined as H-2Dd negative. (B,C) Donor CD4+ and CD8+ splenocytes (H-2Dd–negative cells) from TCD-BMT recipients were subsetted according to eGFP expression and analyzed for apoptosis by annexin-V staining on days 18, 32, 45, and 56 after transplantation. Mice that did not receive transplants were also analyzed and are denoted by “N” in these figures. (D) Donor splenocytes (H-2Dd–negative cells) from TCD-BMT recipients were subsetted according to eGFP and CD44 expression. T-cell apoptosis was evaluated by annexin-V staining. (F) Donor splenocytes (H-2Dd–negative cells) from TCD-BMT recipients were subsetted according to eGFP and CD44 expression. Intracellular Bcl-2 levels were measured.

Recent thymic emigrants are less susceptible to peripheral T-cell apoptosis

We next sought to determine whether T-cell maturation after thymic export can affect posttransplantation peripheral T-cell apoptosis. In these experiments, we used RAG-2-eGFP–transgenic mice to distinguish recent thymic emigrants from mature peripheral T cells. Proper T-cell development requires the rearrangement of the V, D, and J genes and is regulated by recombinant activating genes (RAG), which are expressed during the CD4−CD8− double-negative (DN) and CD4+CD8+ double-positive (DP) stages of T-cell development in the thymus. In RAG-2-eGFP mice, most DP, CD4+CD8−, and CD4−CD8+ single-positive (SP) thymocytes express high levels of eGFP29,30 (Figure S4A). eGFPhi and eGFPlo T cells can be detected in the periphery. As previously documented,29,30 eGFPhi T cells are CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that have not divided in the periphery and represent recent thymic emigrants. By contrast, eGFPlo T cells have divided and represent mature peripheral T cells.

We first analyzed splenic T cells in RAG-2-eGFP Tg mice that did not receive transplants and found that eGFPhiCD4+ and CD8+ T cells constituted approximately 10% of peripheral T cells in 2-month-old mice that did not receive transplants (Figure 4A). As expected, nearly all eGFPhi T cells had a naive T-cell phenotype (CD44loCD62L+) and did not express activation markers such as CD25 (data not shown). By contrast, the eGFPlo population included T cells with both naive and effector/memory phenotypes (CD44lo and CD44hi, respectively). It is noteworthy that eGFPlo CD44hi T cells contained higher numbers of apoptotic cells, whereas eGFPlo CD44lo naive T cells displayed very low levels of apoptosis in normal RAG-2-eGFP Tg mice (Supplemental Figure 4B-C). Surprisingly, however, the rare eGFPhi CD44hi recent thymic emigrants had increased levels of apoptosis, again suggesting CD44 as an important predictor of peripheral apoptosis.

We then analyzed recipients of TCD-BM allografts from RAG-2-eGFP Tg mice and found a significant increase of the percentage of eGFPhi T cells during T-cell reconstitution (Figure 4A). A kinetic analysis of posttransplantation peripheral T-cell apoptosis in this model revealed that after 1 month, CD4+ and CD8+ eGFPlo T cells had significantly elevated levels of apoptosis compared with eGFPhi T cells (Figure 4B,C). Similar to mice that did not receive transplants, eGFPlo CD44hi effector/memory T cells had a high percentage of apoptotic cells (Figure 4D). It is noteworthy that even eGFPhi CD44hi recent thymic emigrants had increased percentages of apoptosis, suggesting again a correlation between CD44 expression and peripheral T-cell apoptosis. Analysis of Bcl-2 expression demonstrated an overall decrease in percentage of Bcl-2–expressing CD8+ T cells and a significant decrease in eGFPloCD44hi CD4+ T cells (Figure 4E). We conclude that in both TCD-BMT recipients and in mice that did not receive transplants (1) recent thymic emigrants are less susceptible to apoptosis and (2) T cells with a CD44hi activated/memory phenotype are more susceptible to peripheral T-cell apoptosis.

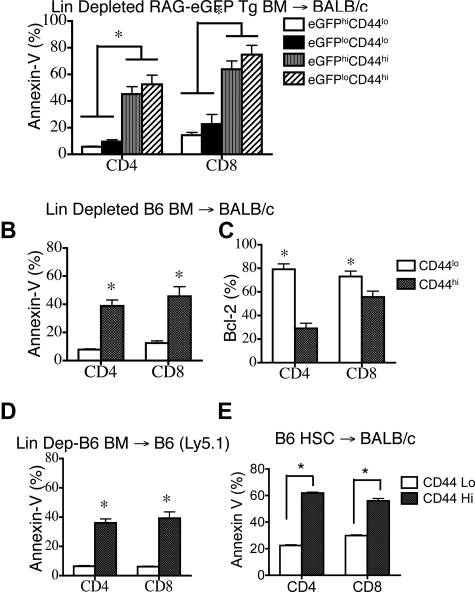

CD44hi apoptotic T cells are donor BM-derived and present in syngeneic, MHC-mismatched, and MHC-matched allogeneic transplantation

We hypothesized that CD44hi T cells could arise by 2 different mechanisms. They could represent residual mature T cells in the TCD-BM allograft that escaped T-cell depletion and underwent alloactivation and expansion upon transfer into the lethally irradiated allogeneic host. Alternatively, they could be de novo–generated T cells, which are derived from donor HSCs and develop in the thymus of the recipient. These cells would be tolerant but can still undergo peripheral expansion in the lymphopenic environment after BMT.

To eliminate residual mature T cells, we depleted all lineage-positive cell populations in RAG2-eGFP Tg BM and infused 105 lineage-negative BM cells into allogeneic recipients. These animals did not exhibit signs of clinical GVHD. At 6 weeks after BMT, we found that 14% ± 3.8% of CD4+ T cells and 23.3% ± 2.3% of CD8+ T cells were CD44hi and predominantly eGFPlo, consistent with the peripheral expansion of de novo BM-generated T cells (data not shown). However, both CD44hieGFPlo and CD44hieGFPhi T cells had higher percentages of apoptotic cells than CD44loeGFPhi and CD44loeGFPlo T cells (Figure 5A). We repeated this experiment in another MHC-disparate BMT model and again found that apoptosis in both CD4+ and CD8+ CD44hi T cells was higher than in CD44lo naive T cells (Figure 5B) and correlated with fewer Bcl-2–expressing cells (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

CD44hi T cells are donor BM-derived and persistently apoptotic in recipients of MHC-mismatched or MHC-matched allogeneic TCD-BMT or syngeneic TCD-BMT. (A) Lethally irradiated (850 cGy) 8- to 10-week-old BALB/c mice were transplanted with 105 lineage-depleted RAG2-eGFP Tg BM and harvested on day 42. Donor-derived (H-2Dd negative) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were analyzed. Data representative of 2 independent experiments is shown. (B) Lethally irradiated (850 cGy) 8- to 10-week-old BALB/c mice were transplanted with 105 lineage-depleted B6 BM and harvested at day 42. Donor-derived (H-2Dd negative) CD4+ and CD8+ splenic T cells were analyzed for apoptosis with annexin-V staining. (C) Mice received transplants and were harvested as in (B), and the intracellular levels of Bcl-2 in donor CD44hi and CD44lo, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets were determined. (D) Lethally irradiated (850 cGy) 8- to 10-week-old B6 mice were transplanted with 105 lineage-depleted B6 Ly5.1+ BM and harvested at day 42. Percentages of apoptotic donor-derived (H-2Dd negative) T cells were determined by annexin-V staining. n = 5. (E) Lethally irradiated (850 cGy) 8- to 10-week-old BALB/c mice were transplanted with 104 purified B6 LSK stem cells and analyzed on day 52. Percentages of apoptotic donor-derived (H-2Dd negative) T cells were determined by annexin-V staining (n = 5).

To rule out the possibility that susceptibility to apoptosis was associated with MHC disparity between donor and host, we repeated these experiments with lineage-depleted syngeneic BM. We found again that 10.2% ± 0.7% of donor CD4+ T cells and 39.7% ± 2.0% of CD8+ T cells displayed an effector/memory CD44hi phenotype and contained a higher percentage of apoptotic cells than donor-derived CD44lo naive T cells (Figure 5D).

Because it is difficult to totally exclude residual T-cell contamination after simple T-cell or lineage depletion, we performed experiments with purified hematopoietic stem cells to further exclude any potential contribution of residual mature T cells in the allograft. We thus sorted c-kit+Sca-1+ and lineage-negative stem cells (LSK) from B6 bone marrow after lineage depletion and transplanted 104 LSK cells into lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients. Mice were harvested at day 52 after BMT.

We found that 67.9% ± 1.9% of CD4+ T cells and 78.2% ± 1.6% of CD8+ T cells were of donor origin. It is noteworthy that 14.2% of donor-derived CD4+ T cells and 22.4% of CD8+ T cells expressed high levels of CD44, and these populations were more likely to undergo apoptosis (Figure 5E). These data suggest that de novo–generated donor stem cell–derived T cells can gain CD44 expression and that these CD44hi cells may contribute to T-cell apoptosis in the periphery. We conclude that the CD44hi T cells found in TCD BMT and HSCT represent predominantly donor BM-derived T cells and not alloactivated T cells, and that the increased susceptibility to posttransplantation peripheral T-cell apoptosis is independent of MHC disparity.

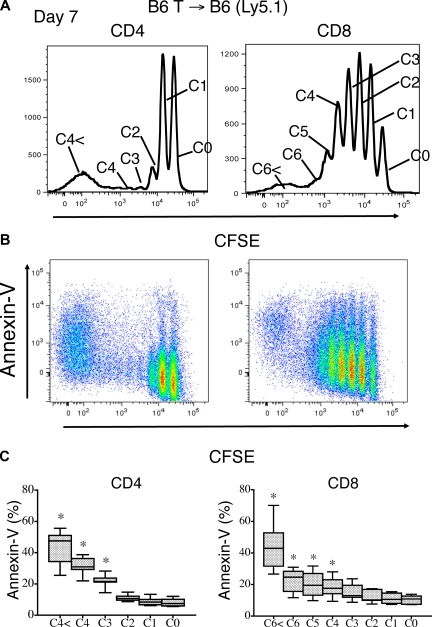

Rapid spontaneously proliferating T cells in the periphery are particularly susceptible to apoptosis

Having established an association between CD44 expression and posttransplantation peripheral T-cell apoptosis, we further explored the peripheral expansion of these T cells and associations with apoptosis by infusing CFSE-labeled T cells into lethally irradiated syngeneic and allogeneic recipients.

We have shown previously in allogeneic recipients that CFSE-labeled T cells can be separated into 3 different populations after infusion according to their phenotype and proliferation kinetics.10 Three days after infusion, alloreactive fast-proliferating T cells are CFSElo and display markedly increased apoptosis compared with the slower proliferating nonalloreactive CFSEint cells and nondividing CFSEhi T-cell populations (Figure S5A). However, we also observed a modest increase in apoptosis in nonalloreactive, proliferating T cells after the infusion of CFSE labeled T cells into syngeneic recipients (Figure S5B).

To better analyze T-cell proliferation-associated apoptosis in the absence of alloreactive T cells, we extended the syngeneic CFSE experiment to analyze recipients at day 7 to evaluate more cell divisions. This allowed for the further division of the proliferating nonalloreactive T cells into 2 groups as reported by Min et al31: rapid (24-hour cycle time) spontaneously proliferating T cells and slow (72-hour cycle time) homeostatically proliferating T cells.

Based on this division, we found that T cells that had divided more than 2 to 3 times (eg, rapid spontaneously proliferating T cells) had a higher percentage of apoptotic cells compared with the slow homeostatically proliferating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which had undergone few or no divisions (Figure 6A-C).

Figure 6.

Rapid spontaneous proliferation of nonalloreactive donor T cells enhances peripheral apoptosis. Lethally irradiated (1100 cGy) B6 Ly5.1 recipients were transplanted with 2 × 107 CFSE-labeled B6 purified T cells. (A) Apoptosis of donor (Ly5.2+) T cells as defined by annexin V staining was measured on day 7 after adoptive transfer. Top histograms reveal the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell proliferation pattern. (B) Annexin V staining on proliferating donor CD4+ and CD8+ T cells is shown. (C) The mean percentages of apoptotic, annexin V+ T cells with data from 5 combined independent experiments is shown (n = 7).

In agreement with previous studies regarding the phenotype of homeostatically proliferating T cells,10,32,33 these rapid spontaneously proliferating T cells (> 2-3 divisions) expressed high levels of CD44 and low levels CD62L. In contrast to fast-proliferating alloreactive T cells, they did not up-regulate CD25 expression (Figure S6) or down-regulate their IL-7Rα expression10,34 (Figure S7A), exhibiting a “partially activated” phenotype. No changes in the level of Fas expression with cell cycling was observed (Figure S7B) Finally, we found again that the increased apoptosis of these rapid spontaneously proliferating T cells correlated with a modest decrease in Bcl-2 expression (Figure S7C). We conclude from these experiments that only a subset of the nonalloreactive, peripherally expanding T cells (ie, the rapid spontaneously proliferating T cells) is particularly susceptible to apoptosis.

Finally, we further extended the syngeneic CFSE experiment to analyze recipients at day 14 to evaluate the stability of the phenotypes of rapid spontaneous proliferating T cells and slow homeostatically proliferating T cells. We observed more apoptosis of rapid spontaneous proliferating T cells compared with slow homeostatically proliferating T cells, in agreement with what we observed on day 7, as well as the maintenance of a partially activated phenotype in rapid spontaneous proliferating T cells but not slow homeostatically proliferating T cells, again in agreement with what we observed on day 7 (data not shown).

Discussion

The role of impaired thymopoiesis in delaying T-cell reconstitution after allogeneic-BMT has been well demonstrated.1,3,10,35 Yet peripheral T-cell apoptosis also hinders reconstitution after allogeneic BMT11,12,36 and chemotherapy, but the process has not been well characterized. In clinical studies, Lin et al12 observed that increased apoptosis in T cells from allogeneic BMT patients was associated with GVHD and HLA disparity, and suggested associations with activation-induced cell death. Hebib et al11 also found increased peripheral T-cell apoptosis in patients who received allogeneic BMT, which was specifically associated with CD8+ CD45RO+ memory cells and decreased Bcl-2 expression. Brugnoni et al36 observed, in pediatric patients who had received a transplant, decreased Bcl-2 expression and increased Fas levels correlated with activation-induced cell death of CD4 T cells after transplantation. Hakim et al37 found that the increased susceptibility to apoptosis of CD4 T cells after dose-intense chemotherapy was associated with elevated expression of HLA-DR, signifying activation.

In this study, we correlated posttransplantation peripheral T-cell apoptosis with the expression of CD44, resulting in a “partially activated” phenotype, and with the rapid spontaneous proliferation of nonalloreactive T cells in lymphopenic recipients. Our results in experimental mouse models are in agreement with the association of peripheral T-cell apoptosis with a memory-like phenotype and decreased expression of Bcl-2.

However, we did not find a correlation with activation-induced cell death through the Fas/Fas ligand pathway. In addition, apoptosis of helpless CD8+ T cells via the TRAIL pathway did not seem to play a role in controlling posttransplantation donor T-cell apoptosis. Yet 2 interesting reports from the Nagarkatti38,39 group elucidated the role of CD44 expression on activation-induced cell death in T cells. Splenocytes from CD44−/− mice showed resistance to conalbumin and TCR-mediated apoptosis, and signaling through CD44 led to increased apoptosis without affecting Fas expression.

Our findings parallel the results of these studies in the tight link we observed between expression of CD44 and peripheral T-cell apoptosis, independent of Fas/FasL. In our study however, the majority of donor-derived peripheral T cells have been generated de novo and selected in the recipient thymus and are thus unlikely to be truly alloreactive. It is therefore unclear whether expression of CD44 represents a link to “activation-induced” cell death in our murine models. We explored the importance of CD44 up-regulation and its relationship to peripheral T-cell apoptosis by treating recipients of allogeneic and syngeneic BMT with anti-CD44 blocking antibody or control antibody. We observed no differences between anti-CD44 antibody-treated recipients and the control group (data not shown), suggesting that although CD44 is a marker for peripheral T-cell apoptosis after transplant, blockade of CD44 alone is not able to influence this apoptotic process.

Programmed death 1 (PD-1) is a CD28 family molecule that is expressed on activated T, B, and myeloid cells. PD-1 ligands (PD-1L) are expressed on T cells, B cells, antigen-presenting cells, endothelial cells, and tumor tissues. PD-1/PD-1L interactions leads to inhibitory signals, and ligation of PD-1 occurs during autoimmunity, allergy, allograft rejection, antitumor immunity, and chronic virus infection.40–42 PD-1/PD-L interaction has been recently shown to play a role in homeostatic proliferation of T cells.43 Therefore, we examined the expression of PD-1 on donor T cells on day 42 after allogeneic and syngeneic HSCT; we observed that PD-1 expression was largely confined to the CD44hi population (data not shown). Because these CD44hi cells are more susceptible to apoptosis, PD-1 may be implicated for posttransplantation peripheral apoptosis.

We were surprised to find that attempts to modulate posttransplantation T-cell apoptosis by changing levels of Bcl-2, Bax, and Akt, all known to be influential in mediating peripheral T-cell apoptosis via trophic factor withdrawal and nutrient deprivation, also did not significantly influence apoptosis in our models. Several studies have implicated the Bcl-2 family members as regulators of T-cell death, especially via the intrinsic or mitochondrial pathway. The balance between survival and apoptosis of T cells is maintained by protectors (ie, Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL), executioners (ie, Bak and Bax), and proapoptotic messengers such as Bim (reviewed by Alves et al20). We found that donor-derived T cells in recipients of allogeneic BMT had lower Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL levels compared with T cells in healthy control subjects. This association between levels of Bcl-2 expression and apoptosis was also reported in 2 clinical studies.11,36 However, we observed no difference in peripheral T-cell apoptosis in either recipients of Bcl-2 Tg BM or Bax-deficient BM compared with recipients of WT BM. It is possible that overexpression of or interference with a single Bcl-2 family member has no effect on T-cell apoptosis because of redundancies in the apoptotic pathways.

We have demonstrated that during the early lymphopenic posttransplantation period, donor BM-derived thymic emigrants can undergo proliferation, acquire a CD44hi memory-like phenotype, and become more sensitive to peripheral apoptosis than naive undivided T cells. We confirmed this association between activation, proliferation, and apoptosis in experiments with the adoptive transfer of CFSE-labeled T cells into lymphopenic recipients. Moreover, we found that CFSE-labeled, rapidly expanding T cells adoptively transferred into lymphopenic syngeneic recipients are more likely to undergo apoptosis than slow-cycling T cells. Indeed, a recent study by Min et al31 has demonstrated that T cells in a lymphopenic environment can undergo 2 types of proliferation: a rapid spontaneous proliferation and a slower homeostatic proliferation. Rapid proliferation is IL-7–independent and associated with a division time of 24 hours and the acquisition of a memory-like phenotype (including CD44 expression and CD62L down-regulation). In contrast, homeostatic proliferation is IL-7–dependent and associated with a slower proliferation kinetics (24-48 h/cell cycle) and retention of a naive phenotype. We confirmed these 2 distinct types of lymphopenia-driven T-cell proliferation. Our data suggest that in recipients of allogeneic BMT, the spontaneously proliferating donor T cells, which have acquired a memory-like phenotype (ie, CD44) are more vulnerable to apoptosis, whereas slower-proliferating homeostatically expanding T cells are relatively less susceptible to apoptosis.

We finally assessed the potential importance of radioresistant regulatory T cells (Treg) in modulating peripheral T-cell apoptosis after bone marrow transplantation.

Treg mediate their suppressive effects either in a contact-dependent fashion or via releasing inhibitory cytokines such as IL-10 and tumor growth factor-β (TGF-β).44,45 The presence of Treg has also been shown to result in diminished accumulation of T cells and enhanced apoptosis in murine disease models.46 The mechanism of the induction of apoptosis may be perforin-dependent, granzyme B–dependent, or perforin-independent.47,48 A study by Pandiyan et al49 demonstrated that Treg can induce apoptosis in effector CD4+ T cells via cytokine deprivation.

We performed several experiments to better understand the role of radioresistant host regulatory T cells in posttransplantation apoptosis. In Treg depletion experiments, we did not observe significant differences in donor T-cell apoptosis in anti-CD25 versus control IgG-treated recipients of allogeneic and syngeneic BMT (data not shown). Moreover, in studies with the adoptive transfer of CFSE-labeled syngeneic T cells into lethally irradiated wild-type or perforin-deficient host mice, we again observed similar percentages of donor-derived apoptotic T cells (data not shown). These studies suggest that host regulatory T cells do not directly modulate donor T-cell apoptosis in early posttransplantation period in our model systems.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that newly derived donor T cells in BMT recipients display a remarkable susceptibility to apoptosis, which is associated with activation (as determined by CD44 expression) and rapid spontaneous proliferation. The mechanism for this clinically relevant type of T-cell apoptosis remains unclear, and future studies could result in novel strategies to enhance posttransplantation T-cell reconstitution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants HL69929, CA33049, CA107096 (M.R.M.v.d.B.) and P20-CA103694 (S.O.A.) from the National Institutes of Health and awards from the Emerald Foundation, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, the Elsa U. Pardee Foundation, the Ryan Gibson Foundation, the Byrne Foundation, and The Experimental Therapeutics Center of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, funded by Mr William H. Goodwin and Mrs Alice Goodwin, and the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research (M.R.M.v.d.B.). S.O.A. is the recipient of Amy Strelzer Manasevit Scholar Award from The National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP) and The Marrow Foundation.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: S.O.A. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; N.P., S.M., D.S., T.B.A., J.G., C.K., G.L.G., V.M.H., and A.A.K. performed experiments; S.X.L. and O.M.S. performed experiments and wrote the manuscript; and M.R.M.v.d.B. designed experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing ing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marcel R. M. van den Brink, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Zuckerman Research Building 1404, Box 111, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10021; e-mail: vandenbm@mskcc.org.

References

- 1.Small TN, Papadopoulos EB, Boulad F, et al. Comparison of immune reconstitution after unrelated and related T-cell-depleted bone marrow transplantation: effect of patient age and donor leukocyte infusions. Blood. 1999;93:467–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Storek J, Joseph A, Espino G, et al. Immunity of patients surviving 20 to 30 years after allogeneic or syngeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2001;98:3505–3512. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.13.3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Small TN, Avigan D, Dupont B, et al. Immune reconstitution following T-cell depleted bone marrow transplantation: effect of age and posttransplant graft rejection prophylaxis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 1997;3:65–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewin SR, Heller G, Zhang L, et al. Direct evidence for new T cell production in patients after either T cell depleted or unmodified allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants. Blood. 2000;96:555a. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rocha B, Dautigny N, Pereira P. Peripheral T lymphocytes: expansion potential and homeostatic regulation of pool sizes and CD4/CD8 ratios in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:905–911. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanchot C, Rocha B. The organization of mature T-cell pools. Immunol Today. 1998;19:575–579. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan JT, Ernst B, Kieper WC, LeRoy E, Sprent J, Surh CD. Interleukin (IL)-15 and IL-7 jointly regulate homeostatic proliferation of memory phenotype CD8+ cells but are not required for memory phenotype CD4+ cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1523–1532. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan JT, Dudl E, LeRoy E, et al. IL-7 is critical for homeostatic proliferation and survival of naive T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8732–8737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161126098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surh CD, Sprent J. Homeostatic T Cell Proliferation. How far can t cells be activated to self-ligands? J Exp Med. 2000;192:F9–F14. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alpdogan O, Muriglan SJ, Eng J, Willis L, Greenberg A, van Den Brink MR. Interleukin-7 enhances peripheral T cell reconstitution after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1095–1107. doi: 10.1172/JCI17865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hebib NC, Deas O, Rouleau M, et al. Peripheral blood T cells generated after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: lower levels of bcl-2 protein and enhanced sensitivity to spontaneous and CD95-mediated apoptosis in vitro. Abrogation of the apoptotic phenotype coincides with the recovery of normal naive/primed T-cell profiles. Blood. 1999;94:1803–1813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin MT, Tseng LH, Frangoul H, et al. Increased apoptosis of peripheral blood T cells following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2000;95:3832–3839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alpdogan O, Eng JM, Muriglan SJ, et al. Interleukin-15 enhances immune reconstitution after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2005;105:865–873. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rathmell JC, Farkash EA, Gao W, Thompson CB. IL-7 enhances the survival and maintains the size of naive T cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:6869–6876. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.6869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang Q, Li WQ, Hofmeister RR, et al. Distinct regions of the interleukin-7 receptor regulate different Bcl2 family members. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6501–6513. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6501-6513.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soares MV, Borthwick NJ, Maini MK, Janossy G, Salmon M, Akbar AN. IL-7-dependent extrathymic expansion of CD45RA+ T cells enables preservation of a naive repertoire. J Immunol. 1998;161:5909–5917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berard M, Brandt K, Bulfone-Paus S, Tough DF. IL-15 promotes the survival of naive and memory phenotype CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:5018–5026. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alpdogan O, van den Brink MR. IL-7 and IL-15: therapeutic cytokines for immunodeficiency. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khaled AR, Durum SK. Lymphocide: cytokines and the control of lymphoid homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:817–830. doi: 10.1038/nri931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alves NL, van Lier RA, Eldering E. Withdrawal symptoms on display: Bcl-2 members under investigation. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyons AB, Parish CR. Determination of lymphocyte division by flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 1994;171:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okada S, Nakauchi H, Nagayoshi K, Nishikawa S, Miura Y, Suda T. Enrichment and characterization of murine hematopoietic stem cells that express c-kit molecule. Blood. 1991;78:1706–1712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollander GA, Widmer B, Burakoff SJ. Loss of normal thymic repertoire selection and persistence of autoreactive T cells in graft vs host disease. J Immunol. 1994;152:1609–1617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van den Brink MR, Moore E, Ferrara JL, Burakoff SJ. Graft-versus-host-disease-associated thymic damage results in the appearance of T cell clones with anti-host reactivity [In Process Citation]. Transplantation. 2000;69:446–449. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200002150-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chao DT, Korsmeyer SJ. BCL-2 family: regulators of cell death. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:395–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khaled AR, Durum SK. Death and Baxes: mechanisms of lymphotrophic cytokines. Immunol Rev. 2003;193:48–57. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strasser A, Harris AW, Cory S. bcl-2 transgene inhibits T cell death and perturbs thymic self-censorship. Cell. 1991;67:889–899. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90362-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bommhardt U, Chang KC, Swanson PE, et al. Akt decreases lymphocyte apoptosis and improves survival in sepsis. J Immunol. 2004;172:7583–7591. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu W, Misulovin Z, Suh H, et al. Coordinate regulation of RAG1 and RAG2 by cell type-specific DNA elements 5′ of RAG2. Science. 1999;285:1080–1084. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yannoutsos N, Wilson P, Yu W, et al. The role of recombination activating gene (RAG) reinduction in thymocyte development in vivo. J Exp Med. 2001;194:471–480. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Min B, Yamane H, Hu-Li J, Paul WE. Spontaneous and homeostatic proliferation of CD4 T cells are regulated by different mechanisms. J Immunol. 2005;174:6039–6044. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldrath AW, Bogatzki LY, Bevan MJ. Naive T cells transiently acquire a memory-like phenotype during homeostasis-driven proliferation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:557–564. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho BK, Rao VP, Ge Q, Eisen HN, Chen J. Homeostasis-stimulated proliferation drives naive T cells to differentiate directly into memory T cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:549–556. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alpdogan O, Schmaltz C, Muriglan SJ, et al. Administration of interleukin-7 after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation improves immune reconstitution without aggravating graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2001;98:2256–2265. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.7.2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van den Brink MR, Alpdogan O, Boyd RL. Strategies to enhance T-cell reconstitution in immunocompromised patients. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:856–867. doi: 10.1038/nri1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brugnoni D, Airo P, Pennacchio M, et al. Immune reconstitution after bone marrow transplantation for combined immunodeficiencies: down-modulation of Bcl-2 and high expression of CD95/Fas account for increased susceptibility to spontaneous and activation-induced lymphocyte cell death. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;23:451–457. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hakim FT, Cepeda R, Kaimei S, et al. Constraints on CD4 recovery postchemotherapy in adults: thymic insufficiency and apoptotic decline of expanded peripheral CD4 cells. Blood. 1997;90:3789–3798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Do Y, Nagarkatti PS, Nagarkatti M. Role of CD44 and hyaluronic acid (HA) in activation of alloreactive and antigen-specific T cells by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. J Immunother (1997) 2004;27:1–12. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKallip RJ, Do Y, Fisher MT, Robertson JL, Nagarkatti PS, Nagarkatti M. Role of CD44 in activation-induced cell death: CD44-deficient mice exhibit enhanced T cell response to conventional and superantigens. Int Immunol. 2002;14:1015–1026. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blattman JN, Greenberg PD. PD-1 blockade: rescue from a near-death experience. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:227–228. doi: 10.1038/ni0306-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keir ME, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-1 regulates self-reactive CD8+ T cell responses to antigen in lymph nodes and tissues. J Immunol. 2007;179:5064–5070. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okazaki T, Honjo T. The PD-1-PD-L pathway in immunological tolerance. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin SJ, Peacock CD, Bahl K, Welsh RM. Programmed death-1 (PD-1) defines a transient and dysfunctional oligoclonal T cell population in acute homeostatic proliferation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2321–2333. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bluestone JA, Abbas AK. Natural versus adaptive regulatory T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:253–257. doi: 10.1038/nri1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells: key controllers of immunologic self-tolerance. Cell. 2000;101:455–458. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80856-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen S, Ding Y, Tadokoro CE, et al. Control of homeostatic proliferation by regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3517–3526. doi: 10.1172/JCI25463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gondek DC, Lu LF, Quezada SA, Sakaguchi S, Noelle RJ. Cutting edge: contact-mediated suppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory cells involves a granzyme B-dependent, perforin-independent mechanism. J Immunol. 2005;174:1783–1786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grossman WJ, Verbsky JW, Barchet W, Colonna M, Atkinson JP, Ley TJ. Human T regulatory cells can use the perforin pathway to cause autologous target cell death. Immunity. 2004;21:589–601. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pandiyan P, Zheng L, Ishihara S, Reed J, Lenardo MJ. CD4(+)CD25(+)Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells induce cytokine deprivation-mediated apoptosis of effector CD4(+) T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1353–1362. doi: 10.1038/ni1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.