Abstract

Family caregivers of older individuals in rehabilitation have unique needs and concerns that should be addressed in rehabilitation and in community-based programs. Their concerns have a direct bearing on their health and on the health and well-being of their care-recipients. In this paper, we review the major problems facing many caregivers of older individuals who may receive rehabilitation services, and we discuss implications from relevant research. We conclude with recommendations for interventions, services and program development.

Keywords: Caregivers, older age, rehabilitation

1. Introduction

With the aging of the baby-boom generation and longer life expectancies, the number of older adults in the United States is expected to grow significantly in the coming years. The population of adults over age 65 increased from 4% to almost 13% just in the last decade, and the number of older adults is expected to increase to 23% within the next fifty years. Whereas adults over the age of 85 currently comprise only 1% of the U.S. population, that number is expected to grow by four times within the next fifty years. Because older adults are more prone to chronic illnesses such as strokes and various forms of cancers and dementias, the prevalence of chronically ill older adults can be expected to rise in relation to the increasing older adult population [2]. The challenges and opportunities to the field of rehabilitation to address the healthcare needs of this growing segment of the population are immense [5].

The increase in the number of persons living into older age as well as the increased frequency of chronic and debilitating health conditions they experience have resulted in an increasing number of family caregivers. Indeed, family caregivers have been recognized as the “…backbone of our country's long-term, home-based, and community-based care systems” [7] and they are the largest group of care providers in the United States [38]. The market value of their activity far exceeds that spent on formal health care and nursing home care [52]. The role of the family caregiver is often studied as an aspect of adjustment in rehabilitation programs, but few systematic services have been developed and evaluated in the rehabilitation literature. Fortunately, considerable research has examined the situation of family caregiving in older age, and considerable evidence exists concerning various ways to assist family caregivers in these situations.

In this paper, we will review the major problems facing many caregivers of older individuals who may receive rehabilitation services, and we discuss implications from relevant research. We conclude with recommendations for interventions, services and program development.

2. Family caregiving, health and rehabilitation

Family caregivers operate as extensions of health care systems (performing complex medical and therapeutic tasks and ensuring care recipient adherence to therapeutic regimens) [10], yet they typically do not receive adequate training, preparation, or ongoing support from these systems [45]. The responsibilities of caregiving (and corresponding lack of preparation, guidance and support) erode their physical and emotional health [53] and their financial resources [34]. Consequently, many caregivers experience considerable burden, depression, and disruption of their own well being and social activities [42] and are at risk for physical health problems [53] and premature mortality [43].

Older adults acting as caregivers may be particularly vulnerable because caregiving demands may tax their health and physical abilities and compromise their immune response systems, and the stress associated with caregiving can exacerbate existing chronic health conditions [53]. Most persons caring for frail elders are age 65 and older, and persons in this age group have a higher incidence of heart disease, cancer, arthritis, hypertension, and diabetes. Declines in personal health are associated with older age among caregivers, and older caregivers in poor health are especially vulnerable to the strains of caregiving [35]. Aging caregivers also face considerable risks in managing the physical demands of adult children with disabilities, and they have lingering concerns about who will care for their loved one if they are unable to do so [4].

The health and well-being of caregivers and care recipients may be particularly jeopardized following care recipient discharge to the community. Caregivers of persons with stroke are at risk for unintentional injuries (such as falls, cuts, scrapes, bruises) that can range from minor to serious [26]. Caregivers who experience problems with depression and burden may be more likely to institutionalize dependent family members and caregiver burnout, as opposed to the care recipient's physical condition, appears to be a primary reason why individuals are admitted to nursing homes [1]. Depressed caregivers may display potentially harmful and abusive behaviors toward care recipients [55]. There is also evidence that greater caregiver burden is associated with increased falls among elderly care recipients [29].

Many of the health conditions that necessitate the involvement of a family caregiver are treated in rehabilitation facilities. In one statewide surveillance project funded by the Centers for Disease Control, the majority of care recipients were older than the national average and the most frequent health conditions identified were heart disease (12.8%), cancer (11.7%), stroke (9.1%), diabetes (9%), dementia (8.8%), arthritis/rheumatism (5.1%), lung disease (3%), cerebral palsy (2.6%), and hypertension (2.4%) (out of 5,859 survey respondents) [36]. The functional limitations of care recipients that necessitated the most assistance for the caregiver included moving around (41.7%), self-care (eating, dressing, bathing, toileting, etc.; 41%), learning, memory and confusion (17%), and anxiety or depression (16.4%) [36].

However, research also indicates that there is considerable variance in adjustment reported by caregivers of older individuals and this finding has implications for clinical practice. For example, caregivers who are able to find a sense of meaning in their circumstances [50] and who enjoy high levels of social support [22] appear particularly resilient. The quality of the caregiver-care recipient relationship is also very important. Evidence indicates that caregivers who were satisfied in their pre-disability relationship with a care recipient report more optimal adjustment than those who lacked in relationship satisfaction [54]. Interpersonal dynamics also have a pronounced effect on older care recipients: Spousal criticism and hostility has been associated with greater care recipient distress and maladaptive coping behaviors [33] and health-compromising behaviors [19], and with increased primary care utilization [18] among older care recipients. Older care recipients have been found to be resentful of overprotective caregivers [50] and there is evidence that they report greater depression if their caregiver has an ineffective, dysfunctional problem-solving style [27].

3. Interventions for caregivers of older persons

Given the pressing needs of an aging society, the extant literature is replete with various intervention strategies to assist caregivers of older individuals with debilitating conditions. Several reviews have conceptualized these interventions in terms of support groups, individual counseling, family counseling, case management, respite services, and knowledge and skill training. Generally, these reviews have concluded that “more is better” for these caregivers: programs that provide services, support, information and skill building with a relative intensity (in terms of frequency and duration) have a greater positive effect than circumscribed, infrequent and educationally-based programs [3,45,47]. Psychoeducational and psychotherapeutic interventions that integrate diverse and multiple components of assistance specific to caregiver needs are recommended [20].

Much of this evidence relies on studies of caregivers of persons with dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Intervention research conducted with caregivers of persons with stroke has yielded respectable support for coping skills training with problem-solving training (PST) having particular utility for many of these caregivers [31]. PST can be conveniently provided in long-distance technologies in the home [23] and it can be integrated into self-care and health promotion activities for the caregiver and care recipient [14]. Randomized clinical trials indicate that PST may effectively lower caregiver distress following discharge into the community [23] and it can have beneficial effects for community-residing caregivers regardless of caregiver age [12], of the degree of care recipient functional impairment [12,40], or of the length of time spent in the caregiver role [40].

4. Developing services for family caregivers of older persons in rehabilitation

The needs of family caregivers in our society have progressed to the extent that their health and well-being is now considered a stated priority in public health [49] and mental health policy [48]. Healthy People 2010 [51] recommends the development of behavioral and social initiatives to promote the health and quality of family members who provide assistance in the home to a loved one with a disability. It is doubtful that any single service provider or institution can adequately and efficiently address caregiver needs, as these needs are dynamic and evolving, subject to change related to the physical, psychological, social and financial resources of the caregiver and in the resources and status of the care recipient [45]. Thus, services that are traditionally and understandably circumscribed to rehabilitation needs, as defined by the setting and the treatment team, may have little relevance to family caregivers over time, depending on the unique trajectory of their caregiving scenario and the resources that may be available (or depleted) over time.

In a recent essay, Elliott and Parker [15] argue that family caregivers require a coordinated, comprehensive and sustainable care plan – crafted by a partnership between trusted and involved professional providers with the family caregiver – that recognizes and accommodates the fluctuating, dynamic needs of the caregiver and care recipient over time. These care plans would take necessary steps to (a) understand the landscape of caregiving tasks specific to the dyad (e.g., medical needs would require maintaining contact a specific medical specialist), (b) assess and monitor the health of the caregiver as well as their legal and financial needs, (c) identify the specific tasks and problems reported and experienced by the caregiver at any given point in time, and (d) maintain ongoing contact with the caregiver to assess their changing needs and challenges [15].

Rehabilitation programs routinely develop post-discharge plans for the patient receiving specialized services determined by the expertise of the participating professions and by the rehabilitation needs of the patient. The care plans recommended by Elliott and Parker, and by the public health priorities noted above, focus on the needs and well-being of the caregiver, in light of the risks of caregiving to the caregiver and to the care recipient. Thus, this kind of plan has several features that can be distinguished from the usual caregiver programs typically provided in rehabilitation settings.

First, these recommendations recognize that the needs of the caregiver cannot be addressed in brief, educationally-based training during the inpatient rehabilitation program or in brief, infrequent outpatient visits arranged with the patient's care providers. Research to date clearly indicates that family caregivers need an array of community-based services that address their unique problems over time. Family caregivers face enormous difficulties in accessing health care that requires travel, including mobility problems, compromised health status, and prohibitive distances to hospitals or clinics. Older individuals are known to under-utilize mental health services [41] and caregivers often ignore their own personal mental and physical health needs [53]. To increase access, professionals must rely on nontraditional long-distance technologies to provide services to caregivers in their home. Evidence from several randomized trials indicates that counseling sessions provided in telephone sessions [23], computerized programs [21], videoconferencing [13] and an integration of face-to-face and telephone sessions [40] can effectively reduce caregiver distress, and these effects are significantly greater than those attributable to educational programs delivered in the same manner.

Second, providers should focus on developing “partnerships” with family caregivers that recognize the active and essential role these individuals have in our health care systems, and respect their needs for ongoing training, support and assistance [24]. This collaborative model also recognizes and promotes the ability of caregivers to identify and articulate their unique needs and problems as they perceive them and as they experience them. This perspective runs counter to many service delivery programs, in which a “top-down” approach is promulgated by service providers. This perspective also diverges from traditional rehabilitation programs: Although rehabilitation programs promote a collaborative approach, the patient is usually considered the viable, active member in this activity, inadvertently marginalizing the family caregiver as an ancillary member of the team and overlooking the necessity for their ongoing support, training and well-being.

To achieve this collaborative partnership, and to facilitate an informed understanding of caregiver needs and concerns, it is necessary to examine the ways in which information is gathered from family caregivers who usually have little or no formal preparation for the varied and complex roles they will encounter. Most services rely on professional care providers' anticipation of problems routinely encountered with specific rehabilitation populations. But interventions that address the specific needs of families and their members, as they perceive them, are more likely to succeed [6]. Typically, professionals assume that changes and assistance in basic self-care and activities of daily living constitute the sources of burden on family caregivers. However, qualitative research indicates that many family caregivers experience more problems with interpersonal, relationship and family dynamics than with problems specific to a particular disability [16].

For many family caregivers, many problems will become apparent following their return home. In a thorough qualitative study of family caregiving and stroke, Grant and colleagues [25] found that while safety issues remained a constant concern for caregivers in the first three months following the discharge home of their loved one from inpatient stroke rehabilitation, at 12 weeks post-discharge concerns about managing cognitive, behavioral and emotional changes were more frequent with concerns about managing functional deficits and activities of daily living also considerably diminished.

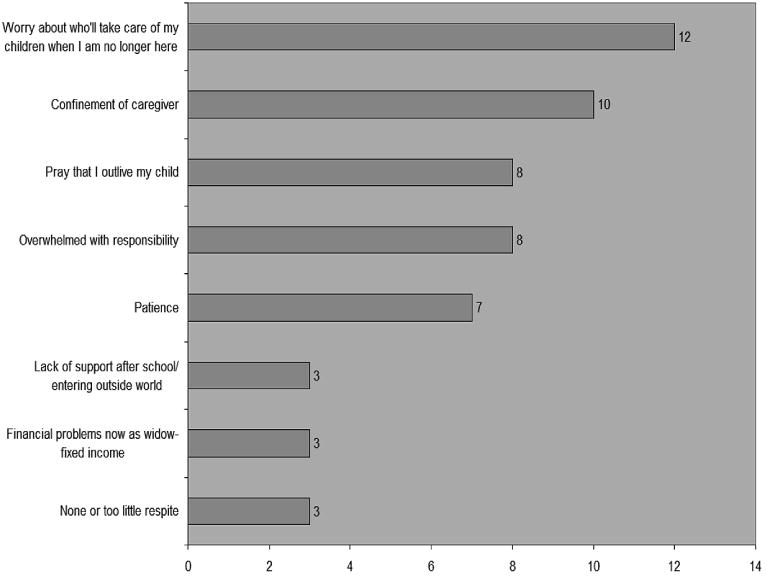

In contrast, caregivers who make life-long commitments to assist a family member with a severe disability face unique problems as they age. The number of these “forgotten” caregivers has steadily increased with noted advances in medical and emergency technologies that have dramatically increased the life expectancies of many persons with acquired and developmental disabilities [30]. For example, Figure 1 presents results from a focus group conducted with nine aging mothers (average age = 56.77; range 44 – 77 years of age) of adult women with cerebral palsy (average age = 33.55; range 23 – 58 years of age). These caregivers identified and voted on the top problems they experienced, and the problem receiving the most votes clearly reveals their awareness of the lack of social and community supports available to their care recipients (“worry about who'll take care of my children when I am no longer here”). Other problems receiving votes reflect their psychological stress, their isolation from others and the lack of services available to their adult child (e.g., “lack of support after school/entering the outside world”), and the financial problems imposed by a fixed income. Although some of these issues may be addressed in home-based counseling programs, others require solutions from social and health services that are lacking in many communities. A limited and specific focus on the medical and functional needs of the care recipient would be insensitive to the presence and consequences of these problems to the health and well-being of the caregiver and, by extension, to the care recipient.

Fig. 1.

Problems receiving the most votes in a focus group of aging mothers (N = 9) of adult women with cerebral palsy. Each of the nine caregivers could cast up to 6 votes among the problems nominated by the group.

5. Therapeutic strategies

There are several clinical and pragmatic implications for rehabilitation teams working with family caregivers of older persons. Specifically, we see several implications for assessment, counseling and training during inpatient programs, and for developing counseling and support programs with long-distance technologies.

5.1. Standardized and phenomenological assessments

Informed assessment is a hallmark of expert rehabilitation. We recommend a specific focus on the assessment of caregiver assets, abilities, and limitations. This may not always be possible or thorough, as financial resources, mobility problems, and distance often limit the degree to which caregivers can participate in inpatient rehabilitation therapies.

Standardized, self-report measures can be efficiently administered to assess caregiver adjustment. Evidence indicates that caregivers who are depressed during the inpatient rehabilitation program are more likely to have problems with emotional adjustment and physical health in the first year of caregiving [46]. Caregiver reports of their personal health are also important for similar reasons [46]. Clinical observations should attend to possible problems with visual or cognitive impairments and for possible difficulties with balance and strength among older caregivers.

We suggest a more refined and strategic use of subjective, phenomenological measures to understand the assets and concerns of each individual caregiver. Previous work has demonstrated the use of card-sort tasks in interviews with caregivers to identify and prioritize the problems they experience [17,28]. The card-sort exercise lists various problems presented by other caregivers, and the interviewer asks a caregiver to review the cards, recognize problems that they experience, and discuss prior coping attempts, possible solutions, and state their goals for coping. In this process, valuable information about the quality of relationships, coping abilities and other personal and social resources will become apparent.

5.2. Inpatient Counseling and Training Programs for Caregivers

Few caregivers can devote the time and energy necessary for comprehensive education and training prior to assuming their role as primary caregiver. Most rehabilitation programs have printed educational materials available for caregivers to read. Staff should ensure that older caregivers are able to read the print size of these materials and provide assistance with comprehending materials as needed. Older care recipients may have multiple health problems (e.g., diabetes, visual impairments pain): In these situations demands on the caregiver will likely escalate with the overlay of additional self-care regimens and functional impairments in the wake of an acquired disability. Although educational programs for caregivers are relatively standard practice in rehabilitation programs, these programs typically do not adequately prepare most caregivers for the issues and roles they will face at home.

It is recommended that rehabilitation staff develop a working partnership with the caregiver during the inpatient stay. Although many caregivers may not seek mental health services, an active partnership with a skilled rehabilitation team member may initiate a partnership during the assessment process and this activity can establish meaningful conversation about caregiver assets, priorities, and concerns. Caregivers may be receptive to strategies that help them develop skills and perspective without exclusively focusing on mental health issues. Along these lines, interventions such as reminisce and narrative therapy and the development of a partnership may decrease feelings of hopelessness and provide a collaborative rapport for eventual training in problem-solving skills.

Narrative therapy, which includes examination of a person's account of their past as well as their perceived skills, beliefs, and principles, may be particularly helpful in fostering collaborative relationships with caregivers and identifying solutions to the problems they may encounter. This approach is best applied with a “not-knowing” stance that utilizes empathy, understanding, and curiosity to create a nurturing environment for caregivers to explore the problems they face. By eliciting key stories from caregivers, narrative therapy can offer insight into the caregiver's sense of self. A clinician can subsequently assist caregivers to appreciate how the problems they face are issues to be solved and that they are not inherently characteristic of the caregiver [11].

By employing gentle inquiry to extract primary self-stories [11], narrative therapy strives to help caregivers develop healthier alternative stories to form meaning in their lives. Because older adults tend to reminisce about past life events to a greater degree than younger adults, therapists may benefit from using these occurrences as a therapeutic tool. Allowing older adults to reminisce and actively engage in structured reviews of life stories may serve as an effective way to recognize both positive and negative themes within in their lives and in their relationship with the care recipient. Once a partnership with the caregiver is established, explicit focus can be turned to promoting problem-solving skills.

5.3. Post-discharge partnerships and long-distance technologies

Post-discharge plans should include regular and scheduled telephone contacts to monitor caregiver needs and adjustment in the community. Most outpatient rehabilitation programs are predicated on the identified needs of the care recipient. From our perspective, caregiver issues are best addressed in the home environment. As discussed earlier, long-distance technologies (ranging from telephone sessions to web downloads) can be used effectively to provide training and support to family caregivers.

Telephone sessions should build upon the partnership formed during the inpatient stay, as these maintain a sense of continuity with the rehabilitation staff member. We also recommend following a scripted protocol that guides the staff member in several steps for collecting important information and prompting the staff member on the key elements of problem-solving training. Several scripts are available in the extant literature, including one used in a large-scale intervention study of family caregivers of persons with Alzheimer's disease [8]. We recommend the scripts developed by Grant et al. [24] because these have been successfully employed in several clinical trials with other caregivers. These scripts also provide detailed instruction on how to train caregivers in developing a proper orientation toward solving problems in everyday situations and how to regulate emotions during problem-solving situations. This component is deemed theoretically [37] and methodologically [32] essential for PST to be effective.

6. Summary

To meet the needs of an aging population, a growing number of family caregivers will be realized in the coming years. During this period, public and health care policy will be compelled to identify and provide strategic, community-based services to these individuals and their care recipients. Many of these caregiving scenarios will involve older care recipients with health conditions that could benefit from rehabilitation services. To adequately address the ongoing and dynamic needs of these caregivers, rehabilitation professionals should explore ways to expand existing services to families in the community and utilize long-distance technologies. These services will likely require greater co-ordination with public health and community agencies that can focus on the specific and unique needs of each family caregiver. As these services are developed and implemented, ongoing evaluation of their efficacy and opportunities to meet subsequently identified needs of caregivers and their care recipients should be a priority.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by grants from the National Institute on Child Health and Human Development (# R01HD37661), from the National Institute for Disability and Rehabilitation Research (H133A020509), and from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – National Center for Injury Prevention and Control to the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Injury Control Research Center (R49/CE000191).

References

- 1.Aneshensel C, Pearlin L, Mullan J, et al. Profiles in Caregiving: The Unexpected Ccareer. San Diego: Academic Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berk LE. Development Through the Lifespan. 3rd. Boston: Pearson; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourgeois MS, Schulz R, Burgio L. Intervention for caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease: A review and analysis of content, process, and outcomes. International J of Human Develop. 1996;43:35–92. doi: 10.2190/AN6L-6QBQ-76G0-0N9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braddock D. Aging and developmental disabilities: Demographic and policy issues affecting American families. Mental Retardation. 1999;37:155–161. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(1999)037<0155:AADDDA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown KS, DeLeon PH, Loftis CW, Scherer M. Rehabilitation psychology: What is psychology's true potential? Rehabil Psychol. in Press. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burman B, Margolin G. Analysis of the association between marital relationships and health problems: An interactional perspective. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:39–63. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter R. Addressing the caregiver crises. [February 8, 2008];Preventing Chronic Disease. 2008 5(1):1–2. http://www.cdc.gov/issues/2008/jan/07_0162.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Cotter EM, Stevens AB, Vance DE, Burgio L. Caregiver skills training in problem solving. Alzheimer's Disease Quarterly. 2000;1:50–61. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donelan K, Falik M, DesRoches C. Caregiving: Challenges and implications for women's health. Women's Health Issues. 2001;11:185–200. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(01)00080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donelan K, Hill CA, Hoffman C, Scoles K, Hoffman PH, Levine C, Gould D. Challenged to care: informal caregivers in a changing health system. Health Affairs. 2002;21:222–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.4.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dwivedi KN, Gardner D. Theoretical perspectives and clinical approaches. In: Dwivedi KN, editor. The Therapeutic Use of Stories. New York: Routledge; 1997. pp. 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliott TR, Berry JW, Grant J. Problem-Solving Training for Family Caregivers of Women with Disabilities: A Randomized Clinical Trial. 2008. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott TR, Brossart D, Fine PR. Problem-solving Training Via Videoconferencing for Family Caregivers of Persons with Spinal Cord Injuries: A Randomized Clinical Trial. 2008. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elliott TR, Hurst M. Social problem solving and health. In: Walsh WB, editor. Biennial Review of Counseling Psychology. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Press; in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott T, Parker MW. Family caregivers and health care providers: Developing partnerships for a continuum of care and support. In: Talley RC, Crews JE, editors. Caregiving and Disabilities. New York: Springer; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott T, Rivera P. The experience of families and their carers in healthcare. In: Llewelyn S, Kennedy P, editors. Handbook of Clinical Health Psychology. Oxford: Wiley & Sons; 2003. pp. 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elliott T, Shewchuk R. Problem solving therapy for family caregivers of persons with severe physical disabilities. In: Radnitz C, editor. Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions for Persons with Disabilities. New York: Jason Aronson, Inc.; 2000. pp. 309–327. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiscella K, Franks P, Shields CG. Perceived family criticism and primary care utilization: Psychosocial and biomedical pathways. Family Process. 1997;36:25–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1997.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franks P, Campbell TL, Shields CG. Social relationships and health: The relative roles of family functioning and social support. Social Science and Medicine. 1992;34:779–788. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90365-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallagher-Thompson D, Coon DW. Evidence-based psychological treatments for distress in family caregivers of older adults. Psychol Aging. 2007;22:37–51. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gitlin LN, Burgio LD, Mahoney D, Burns R, Zhang S, Schulz R, Belle SH, Czaja SJ, Gallagher-Thompson D, Hauck WW, Ory M. Effect of multicomponent interventions on caregiver burden and depression: The REACH multisite initiative at 6-month follow-up: Resources for enhancing Alzheimer's caregiver health (REACH) Psychol Aging. 2003;18:361–374. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant JS, Elliott T, Weaver M, Glandon G, Giger J. Social problem-solving abilities, social support, and adjustment of family caregivers of stroke survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant JS, Elliott T, Weaver M, Bartolucci A, Giger J. A telephone intervention with family caregivers of stroke survivors after rehabilitation. Stroke. 2002;33:2060–2065. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000020711.38824.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grant JS, Elliott T, Giger J, Bartolucci A. Social problem solving telephone partnerships with family caregivers. Internat J Rehabil Research. 2001;24(3):181–189. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200109000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grant JS, Glandon G, Elliott T, Giger JN, Weaver M. Problems and associated feelings experienced by family caregivers of stroke survivors the second and third month postdischarge. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. 2006;13(3):66–74. doi: 10.1310/6UL6-5X89-B05M-36TH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartke RJ, King R, Heinemann A, Semik P. Accidents in older caregivers of persons surviving stroke and their relation to caregiver stress. Rehabil Psychol. 2006;51:150–156. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurylo M, Elliott T, DeVivo L, Dreer L. Caregiver social problem-solving abilities and family member adjustment following congestive heart failure. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2004;11:151–157. doi: 10.1023/B:JOCS.0000016265.62022.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurylo M, Elliott T, Shewchuk R. FOCUS on the family caregiver: A problem-solving training intervention. J Counsel Develop. 2001;79:275–281. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuzuya M, Masuda Y, Hirakawa Y, Iwata M, Enoki H, Hasegawa J, Izawa S, Iguchi A. Falls of the elderly are associated with burden of caregivers in the community. International J Geriatric Psych. 2006;21:740–745. doi: 10.1002/gps.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lollar DE, Crews J. Redefining the role of public health in disability. Ann Rev Public Health. 2003;24:195–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.140844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lui MHL, Ross FM, Thompson DR. Supporting family caregivers in stroke care: A review of the evidence for problem solving. Stroke. 2005;36:2514–2522. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000185743.41231.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malouff JM, Thorsteinsson E, Schutte N. The efficacy of problem solving therapy in reducing mental and physical health problems: A meta-analysis. Clini Psychol Rev. 2007;27:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manne SL, Zautra AJ. Spouse criticism and support: Their association with coping and psychological adjustment among women with rheumatoid arthritis. J Personality Soc Psychol. 1989;56:608–617. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.4.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Metlife Mature Market Institute. The Metlife Caregiving Cost Study: Productivity Losses to US Businesses. Metlife Mature Market Institute; Westport, CT: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Navaie-Waliser M, Feldman PH, Gould D, Levine C, Kuerbis A, Donelan K. When the caregiver needs care: The plight of vulnerable caregivers. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:409–413. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neugaard B, Andresen EM, DeFries EL, Talley RC, Crews JE. Characteristics and Health of Caregivers and Care Recipients – North Carolina. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2005;56:529–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nezu A. Problem solving and behavior therapy revisited. Behav Therapy. 2004;35:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parish SL, Pomeranz-Essley A, Braddock D. Family support in the United States: Financing trends and emerging initiatives. Mental Retardation. 2003;41(3):174–187. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2003)41<174:FSITUS>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Differences between caregivers and non-caregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2003;18:250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rivera P, Elliott T, Berry J, Grant J. Problem-solving training for family caregivers of persons with traumatic brain injuries: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.12.032. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robertson S, Mosher-Ashley P. Patterns of confiding and factors influencing mental health service use in older adults. Clin Gerontol. 2002;26:101–116. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schulz R. Handbook on dementia caregiving, evidence-based interventions for family caregivers. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulz R, Beach S. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The caregiver health effects study. J of the Am Med Assoc. 1999;282:2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shulz R, Matire LM, Klinger JN. Evidence-based caregiver interventions in geriatric psychiatry. Psychiatric Clinics North America. 2005;28:1007–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shewchuk R, Elliott T. Family caregiving in chronic disease and disability: Implications for rehabilitation psychology. In: Frank RG, Elliott T, editors. Handbook of Rehabilitation Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press; 2000. pp. 553–563. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shewchuk R, Richards J, Elliott T. Dynamic processes in the first year of a caregiving career. Health Psychol. 1998;17:125–129. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sorensen S, Pinquart M, Duberstein P. How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2002;42:356–372. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Workshop Report; Surgeon General's Workshop on Women's Mental Health; November 30 –December 1, 2005; Washington, D.C.: Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Talley RC, Crews JE. Framing the public health of caregiving. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:224–228. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thompson SC, Medvene LJ, Freedman D. Caregiving in the close relationships of cardiac patients: Exchange, power, and attributional perspectives on caregiver resentment. Personal Relationships. 1995;2:125–142. [Google Scholar]

- 51.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. Available at http://www.health-gov.healthypeople. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vitaliano PP, Young H, Zhang J. Is caregiving a risk factor for illness? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13:13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan J. Is caregiving hazardous to one's physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:946–972. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williamson GM, Shaffer DR, Schulz R. Activity restriction and prior relationship history as contributors to mental health outcomes among middle-aged and older spousal caregivers. Health Psychol. 1998;17:152–162. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williamson GM, Shaffer DR, et al. Relationship quality and potentially harmful behaviors by spousal caregivers: How we were then, how we are now. Psychol Aging. 2001;16:217–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]