Abstract

One expectation when computationally solving an Earth system model is that a correct answer exists, that with adequate physical approximations and numerical methods our solutions will converge to that single answer. With such hubris, we performed a controlled numerical test of the atmospheric transport of CO2 using 2 models known for accurate transport of trace species. Resulting differences were unexpectedly large, indicating that in some cases, scientific conclusions may err because of lack of knowledge of the numerical errors in tracer transport models. By doubling the resolution, thereby reducing numerical error, both models show some convergence to the same answer. Now, under realistic conditions, we identify a practical approach for finding the correct answer and thus quantifying the advection error.

Keywords: biogeochemical cycles, model errors, source inversions, uncertainties

The importance of accurate transport of trace species in the atmosphere and ocean with realistic time-varying, 3D flows has been investigated (1–11). Many of these studies demonstrate improvements in the circulation as well as the tracer distribution with increased resolution or better numerics. Fewer studies have attempted to quantify the overall error associated with model resolution (9, 10). Choice of numerical method can mean more than just a refinement of errors but can dramatically alter the scientific results (4–7). In general, the use of more accurate numerical methods or higher resolution yields better results, yet the measure of improvement is based on reproducing expected results for smooth 1D and 2D flows with analytic solutions and does not truly quantify the error in realistic scientific applications. We take another approach with 2 numerical methods (1, 2) to determine the correct answer, and thus absolute error, in tracer transport under realistic conditions.

Chemistry-Transport Models (CTMs) are the basic tool for simulations of atmospheric chemistry and composition in applications from climate change to ozone depletion to air quality. CTMs include a wide range of processes that alter the distribution of trace gases and aerosols, such as surface and in situ emissions, photochemistry, gas-phase and surface chemistry, cloud processing, precipitation scavenging, convection and boundary-layer mixing, exchange with the land and oceans, and long-range transport. CTMs solve for the abundances of trace species on a 3D grid but also include tracer transport and mixing processes that are inherently below the horizontal grid resolution, such as convection. At the core of these models is the link between sources and sinks by transport of trace species in a time-varying, 3D wind field (a.k.a. advection).

As part of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Global Modeling Initiative (GMI), 2 modern CTMs undertook a numerical experiment of realistic 3D transport with no analytic solution to demonstrate that they would produce results that were effectively identical at the level of accuracy required for the scientific problems being addressed. Early CTMs (12, 13) were a breakthrough in merging the general circulation of the atmosphere with chemistry and composition, but their numerical methods have known weaknesses. The GMI CTM (14–16) is based on the Lin and Rood (LR) tracer transport algorithm (2), and the University of California, Irvine (UCI) CTM (10, 17, 18) is based on the Prather Second-Order Moments (SOM) algorithm (1). Both LR and SOM are regarded as highly accurate numerical methods (19, 20), and both are regarded as adequately accurate for their many published scientific applications. The UCI CTM has recently pursued the questions of resolution, errors, and convergence in tropospheric ozone production (10).

Test Case of CO2.

The numerical experiment is straightforward. With a specified pattern of constant surface emissions, we follow the buildup and dispersion of fossil-fuel CO2 (21) as a conserved tracer throughout the atmosphere for 10 years by cycling 1 year of archived meteorological fields from the Goddard Institute for Space Studies middle atmosphere model (14, 22). Two scientific applications are addressed. First, surface gradients in CO2 abundance from fossil fuel sources are critical data needed in deriving the biospheric sources and sinks as shown in the TransCom3 studies (T3: 23–26). Latitudinal and longitudinal gradients predicted from the T3 CTMs differ greatly and are a primary source of uncertainty in the inversions. Such large differences are blamed on the use of different meteorological fields and possibly poor numerical methods in the CTMs. Second, the transport of a linearly increasing tracer like fossil-fuel CO2 tests the stratospheric circulation. The time since stratospheric air was last in the troposphere can be measured with CO2 and other trace gases such as SF6. This age-of-air has been used to identify weaknesses in our understanding of the stratosphere (27–30). Systematically, CTMs predict too-rapid stratospheric mixing (i.e., too young an age by 1–2 years), and this is usually blamed on errors in the meteorology.

Given that both GMI and UCI CTMs are using identical meteorological fields, and both have among the best numerics, we expected nearly identical results when compared with the typical spread in published results. This test case was highly constrained: Both used the 3-hour averaged meteorological data at the native resolution of 5° (longitude) by 4° (latitude) by 23 (vertical hybrid-coordinate layers); both had identical grid boundaries and air masses; both implemented the specified subgrid mixing (boundary-layer and convection, nothing in the stratosphere) to be as similar as possible; both calculated the same vertical mass fluxes from the convergence of the specified horizontal mass fluxes. In tests, we found that subgrid mixing, even though implemented slightly differently in the CTMs, reduced differences near the surface.

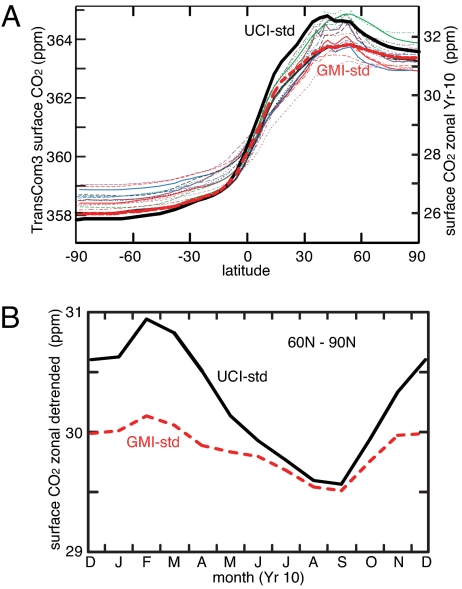

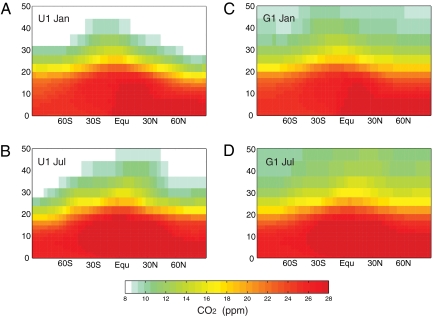

Differences were much larger than expected; indeed, they were almost as large as the published range. In Fig. 1A, the annual-average latitudinal gradient of the surface abundance of fossil-fuel CO2 is compared with the spread of T3 CTMs for a nearly identical experiment (figure 3 of ref. 24). In the southern hemisphere, the GMI and UCI results were nearly identical, as hoped for, but over the source regions in the northern hemisphere the 2 CTMs using the same meteorology differ by >1 ppm (micromoles per mole), comparable with the variance of the T3 CTMs by using different meteorologies. The UCI CTM retains greater CO2 abundances over the continental source regions, but differences extend to the remote stations used for CO2 inversions. For example, the UCI CTM shows a large seasonal cycle in the high-latitude CO2 (60°N–90°N) remote from fossil fuel sources (Fig. 1B), mimicking the biological photosynthesis–respiration cycle. The corresponding GMI cycle is barely discernible. Thus, we conclude that a large source of model error found by T3 in inverting for CO2 could be due to CTM numerical methods. Stratospheric CO2 patterns, shown as latitude-by-height maps for January and July in Fig. 2, are also notably different. The GMI CTM transports more CO2 into the stratosphere and thus has a younger age than the UCI CTM, by 1–2 years over most of the stratosphere. Given that this difference is typical of the model-measurement differences (30), we conclude that an important source of error in stratospheric modeling also includes numerics.

Fig. 1.

Modeled surface abundances of CO2. (A) Zonal mean, surface (Layer = 1) CO2 abundance (ppm = micromoles per mole) calculated by CTMs from surface fossil-fuel emissions. The range of thin colored lines (left axis) are from the TransCom3 study (figure 3 of ref. 24) for the final year of an experiment beginning with 1990 emissions and ending with 1995 emissions (21). From this study (right axis), the UCI CTM (thick black line) and GMI CTM (thick red dashed line) show the Year-10 means following uniform emissions of the 1995 fossil fuel CO2 emissions (2.92 ppm per year). (B) The detrended seasonal variation of high-latitude (60°N–90°N) surface CO2 from Year 10 of this study with the UCI and GMI CTMs.

Fig. 3.

Longitude × latitude color plots of monthly mean, surface CO2 abundance (ppm). (A and B) Data for July Year 10 from U1 (A) and G1 (B). The maximum differences (G1 − U1 in ppm) over the 3 source regions are given in B. An extrapolated estimate of the correct answer is calculated from the doubled resolution U2 and quadrupled resolution U4: Uext = 2 × U4 − U2. (C–F) Difference plots for July Year 10 of dU1 = U1 − Uext (C), dG1 = G1 − Uext (D), dU2 = U2 − Uext (E), and the doubled resolution dG2 = G2 − Uext (F). The rms, area-weighted difference (ppm) for each plot is given in brackets.

Fig. 2.

Latitude × height color plots of zonal mean CO2 abundance (ppm) from GMI and UCI CTMs. (A and B) January (A) and July (B) from Year 10 of UCI advection-only CTM at standard resolution (U1). (C and D) January (C) and July (D) from Year 10 of GMI advection-only CTM at standard resolution (G1).

Quantifying Model Error.

The first experiments with these CTMs included all tracer processes such as advection, convection, and boundary layer mixing. We found numerous minor errors or poor parameterization choices in both CTMs, which were repaired [see supporting information (SI)]. We ascertained that most of the CTM differences (e.g., Fig. 1) were not caused by different implementations of boundary-layer mixing and convection, and thus we continued our experiments (Figs. 2–4) in advection-only mode with no subgrid diffusion and transport of CO2 by the resolved wind field being the only process in the CTM. Assuming that both models have errors related to grid size, we pursued a series of resolution-doubling experiments using the same, fixed-resolution Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) meteorology. For the UCI CTM, we take the GISS wind fields (i.e., air mass fluxes) specified across the boundaries of the 5° × 4° × 23-layer grid (i.e., 72 × 46 × 23 = U1 grid) and assume that they are uniform at higher resolutions of 2.5° × 2° (144 × 90 × 46 = U2 grid) and 1.25° × 1° (288 × 178 × 92 = U4 grid). New interior edges are interpolated linearly in air mass to assure uniform convergence–divergence, and thus the same vertical winds in each subgrid box. To avoid unnecessarily short time steps with doubled resolution, the polar boxes (88°–90°) were not split by latitude. For the GMI CTM we have results for G1 (original 72 × 46 × 23) and G2 (144 × 91 × 46). With GMI LR numerics, the latitudinal grid cannot be simply divided in 2, and we are forced to chose a 2.5° × 2° grid that is offset from the original with 1°-latitude polar boxes. In all cases, the emission pattern is defined as uniform on the original 5° × 4° grid. All comparisons here using different resolutions are made with the mean value predicted for the original 5° × 4° grid and with the average across the split layers. The G1, G2, U1, U2, and U4 results are from the advection-only CTMs.

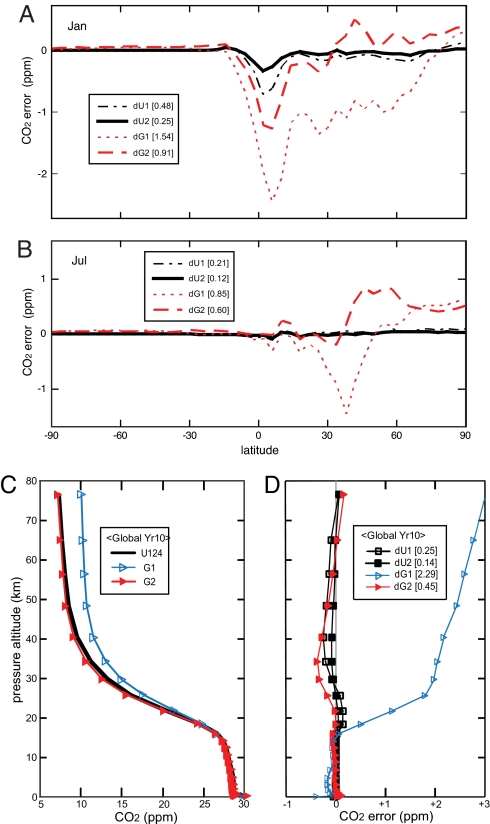

Fig. 4.

Errors in the original (G1, U1) and doubled resolution (G2, U2). (A and B) Latitude pattern of zonal mean errors of the monthly average surface CO2 for January (A) and July (B) of Year 10. Errors are calculated with respect to Uext (see Fig. 3). Results are shown for U1 (thin dashed-dotted black line), U2 (thick solid black line), G1 (thin short-dashed red line), and G2 (thick long-dashed redline). The rms, area-weighted difference (ppm) for each model is given in the legend. (C) Altitude profiles of the Year 10, annual-average, area-weighted global-mean CO2 profiles (ppm) for U1, U2, U4 (thick black line, indistinguishable), G1 (thin blue line, open triangles), and G2 (thin red line, filled triangles). (D) Altitude profile of the errors in these curves (see Fig. 3): dU1 (black open squares), dU2 (black filled squares), dG1 (blue open triangles), and dG2 (red filled triangles). Markers represent the middle of layers in the standard resolution CTM. The rms errors (ppm) of the latitude × altitude annual zonal mean are given in the legend.

Average July surface CO2 abundances for G1 and U1 are shown in Fig. 3 A and B. The surface CO2 patterns in both U1 and G1 are similar, reflecting the sources and prevailing winds. From these figures, one can discern that the G1 simulation is more diffusive. G1 peak abundances over the 3 main source regions are less than those in U1 by 6–8 ppm (not visible with this color scale, but annotated). On a zonal average over most of the northern hemisphere (0–60°N) the G1 simulation is 0.8–1.8 ppm less than the U1 simulation. These differences are consistent with the accepted view that SOM has less numerical diffusion than LR. What is worrisome is the magnitude of these differences, which at a minimum, reflects the error in at least one, if not both, of the models. Further, we accept the possibility that, because of the parameterizations in advection schemes, the 2 CTMs are actually solving different numerical problems, and each CTM might converge to a different answer.

The UCI CTM and its related CTM at Frontier Research Center for Global Change in Yokohama, Japan, demonstrated convergence of CTM results with increasing resolution (10). A U8 grid (576 × 354 × 184) was used to show stable geometric convergence via Aitken's acceleration for the U1–U2–U4 and U2–U4–U8 sequences with a factor of ≈0.5. Therefore, we define an extrapolated answer for the U1–U2–U4 sequence of simulations here as Uext = U4 + (U4 − U2). The differences, U1 − Uext and U2 − Uext, in surface CO2 are shown for July of year 10 in Fig. 3 C and E. Peak differences are small, and the convergence is clear. The differences, G1 − Uext and G2 − Uext, are shown in Fig. 3 D and F. As expected, the peak differences are large for the G1 simulation (Fig. 3B). Although the G1–G2 sequence shows improvement, it overshoots near source regions and lacks the clean convergence of the U1–U2 sequence.

The area-weighted root-mean-square (rms) of the differences of the monthly mean surface CO2 with respect to Uext are given in brackets in the lower corner of Fig. 3 C–F. Although Uext is clearly the converged solution for the UCI CTM, we cannot be sure that it is the correct answer. The reduced differences in G2 − Uext relative to G1 − Uext (Fig. 4) are encouraging. The zonal-mean differences of surface CO2 with respect to Uext are shown for January and July in Fig. 4 A and B, with the rms differences (of full-surface maps) given in the legend. For GMI, there appears to be a general convergence to Uext, the overshoot at the northern edge of source regions ≈45N is likely a property of the GMI LR algorithm, but a systematic difference in north polar regions indicates convergence to a different answer. The approximate convergence of these zonal-mean differences over most of the domain for the advection-only CTMs can be compared with the full-CTM differences in Fig. 1 for the annual-mean surface CO2. Monthly rms differences vary by almost a factor of 2 (minimum in July, maximum in January), and for the UCI CTM the rms error in the annual mean is approximately half of the average for the 12 individual months.

The annual-mean altitude profiles of CO2 for year 10 are shown in Fig. 4C. Differences in U1, U2, and U4 are not discernible in this plot; G1 is very different from U1 (consistent with Fig. 2); but G2 nearly matches U1. The difference profiles with respect to Uext are shown in Fig. 4D along with the rms differences (area-weighted, stratosphere only) in the legend. Here, the general convergence of G2 to Uext is clear, but there is overshoot in the middle stratosphere.

The polar-region differences indicate convergence to 2 different answers and are seen only in the north and for surface CO2 where large gradients in tracer abundance persist. The GMI CTM uses an LR version with poor treatment of the poles, viz., on a given layer the CTM calculates a single abundance for all grid boxes in the 2 latitudes adjacent to the pole (84°–90° in this case). In the early stages of this work, the UCI CTM also averaged the tracer into larger, multigrid zones near the poles. This feature was obviously incorrect, and we rewrote the SOM algorithm on a sphere to include realistic, over-the-pole flow (see SI). The GMI CTM could not be corrected, and the faulty parameterization at the poles results in convergence to an incorrect answer. Nevertheless, the seasonality in the north-polar region dramatically improves with doubled resolution (data not shown): The seasonality of G2 matches that of Uext with a small positive offset (Figs. 3F and 4 A and B); in contrast, G1 has the same incorrect seasonality found in the full CTM (Fig. 1B).

Conclusions

These tests demonstrate that the respective advection errors in each CTM are greatly reduced with a doubling of resolution. Over much of the domain both CTMs are calculating the same, presumably correct, answer with an error proportional to the grid size. An obvious exception for GMI is the polar caps, where an incorrect approximation in the LR algorithm causes the CTM to converge to the wrong answer. A remaining uncertainty with the GMI convergence is the apparent overshoot of the G1–G2 sequence in regions with large, sustained tracer gradients (i.e., northern midlatitude surface, middle stratosphere). We conclude that the sequence U1–U2–U4 converges, defining the correct answer to high accuracy, but that the sequence G1–G2, although greatly reducing the original error, is not proven to converge in all regions. In these tests, the GMI doubled resolution, G2, still has twice the error of the UCI original resolution, U1. If required, the computational costs of achieving the same accuracy with the GMI tracer transport (i.e., G4 or better) would be prohibitive.

For the most part, the UCI CTM converges monotonically with a geometric convergence factor of ≈0.5. Thus, the results from a single doubling experiment, U1–U2, can be used to estimate the error in the original solution and to project the converged solution. Assuming that the GMI CTM converges to the same answer (except at the poles), the geometric factor is variable and sometimes negative. Thus, a single doubling experiment does not project a converged solution, and G1–G2–G4 sequences will be needed to develop an error-quantifying strategy for the GMI CTM. It would be valuable to pursue these experiments with a trajectory-based Lagrangian CTM to determine the number of parcels to achieve similar accuracy.

Understanding and quantifying tracer-transport error is critical for the scientific applications in which these models are used. Based on the evidence, e.g., CO2 emissions and the stratospheric age-of-air, numerical errors can be large enough to impact the scientific results. We must develop an approach for quantifying CTM errors, of which tracer transport is only one.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank 2 referees for their insightful comments. This work was supported at the University of California, Irvine, by National Aeronautics and Space Administration Grants NNG06GB84G and NNG04GA09G, National Science Foundation Grant NSF ATM-0550234, and the Kavli Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0806541106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Prather MJ. Numerical advection by conservation of second-order moments. J Geophys Res. 1986;91:6671–6681. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin SJ, Rood RB. Multi-dimensional flux form semi-Lagrangian transport schemes. Mon Weather Rev. 1996;124:2046–2070. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Searle KR, Chipperfield MP, Bekki S, Pyle JA. The impact of spatial averaging on calculated polar ozone loss, 1, Model experiments. J Geophys Res. 1988;103:25397–25408. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thuburn J, McIntyre ME. Numerical advection schemes, cross-isentropic random walks, and correlations between chemical species. J Geophys Res. 1997;102:6775–6797. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ge XZ, Li F, Ge M. Numerical analysis and case experiment for forecasting capability by using high accuracy moisture advectional algorithm. Meteorol Atmos Phys. 1997;63:131–148. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ginoux P. Effects of nonsphericity on mineral dust modeling. J Geophys Res. 2003;108:4052. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofmann M, Maqueda MAM. Performance of a second-order moments advection scheme in an Ocean General Circulation Model. J Geophys Res. 2006;111:C05006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strahan SE, Polansky BC. Meteorological implementation issues in chemistry and transport models. Atmos Chem Phys. 2006;6:2895–2910. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esler JG, Roelofs GJ, Koehler MO, O'Connor FM. A quantitative analysis of grid-related systematic errors in oxidizing capacity and ozone production rates in chemistry transport models. Atmos Chem Phys. 2004;4:1781–1795. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wild O, Prather MJ. Global tropospheric ozone modeling: Quantifying errors due to grid resolution. J Geophys Res. 2006;111:D11305. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasch PJ, et al. Characteristics of atmospheric transport using three numerical formulations for atmospheric dynamics in a single GCM framework. J Climate. 2007;19:2243–2266. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahlman JD, Moxim WJ. Tracer simulation using a global general circulation model: Results from a mid-latitude instantaneous source experiment. J Atmos Sci. 1978;35:1340–1374. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell GL, Lerner JA. A new finite-differencing scheme for the tracer transport equation. J Appl Meteorol. 1981;20:1483–1498. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douglass AR, et al. Selecting the best meteorology for the global modeling initiative's assessment of stratospheric aircraft. J Geophys Res D. 1999;104:27545–27564. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rotman DA, et al. The Global Modeling Initiative assessment model: Model description, integration and testing of the transport shell. J Geophys Res D. 2001;106:1669–1691. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strahan SE, Duncan BN, Hoor P. Observationally derived transport diagnostics for the lowermost stratosphere and their application to the GMI chemistry and transport model. Atmos Chem Phys. 2007;7:2435–2445. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prather MJ, McElroy MB, Wofsy SC, Russell G, Rind D. Chemistry of the global troposphere: Fluorocarbons as tracers of air motion. J Geophys Res. 1987;92:6579–6613. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall TM, Prather MJ. Seasonal evolution of N2O, O3, and CO2: Three-dimensional simulations of stratospheric correlations. J Geophys Res. 1995;100:16699–16720. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rood RB. Numerical advection algorithms and their role in atmospheric transport and chemistry models. Rev Geophys. 1987;25:71–100. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hourdin F, Armengaud A. The use of finite-volume methods for atmospheric advection of trace species. Part I: Test of various formulations in a general circulation model. Mon Weather Rev. 1999;127:822–837. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brenkert AL. Carbon dioxide emission estimates from fossil-fuel burning, hydraulic cement production, and gas flaring for 1995 on a one-degree grid-cell basis. [accessed October, 1998];1998 http://cdiac.esd.ornl.gov/ndps/ndp058a.htmli.

- 22.Rind D, Shindell D, Lonergan P, Balachandran NK. Climate change and the middle atmosphere. III. The doubled CO2 climate revisited. J Climate. 1998;11:876–894. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gurney KR, et al. Towards robust regional estimates of CO2 sources and sinks using atmospheric transport models. Nature. 2002;415:626–630. doi: 10.1038/415626a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gurney KR, et al. TransCom3 CO2 inversion intercomparison: 1. Annual mean control results and sensitivity to transport and prior flux information. Tellus. 2003;55B:555–579. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Law RM, et al. TransCom3 CO2 inversion intercomparison: 2. Sensitivity of annual mean results to data choices. Tellus. 2003;55B:580–595. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker DF, et al. TransCom3 inversion intercomparison: Impact of transport model errors on the interannual variability of regional CO2 fluxes, 1988–2003. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2006;20:GB1002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall TM, Plumb RA. Age as a diagnostic of stratospheric transport. J Geophys Res. 1994;99:1059–1070. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall TM, Prather MJ. Simulations of the trend and annual cycle in stratospheric CO2. J Geophys Res. 1993;98:10573–10581. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boering KA, et al. Tracer–tracer relationships and lower stratospheric dynamics: CO2 and N2O correlations during SPADE. Geophys Res Lett. 1994;21:2567–2570. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall TM, Waugh DW. Stratospheric residence time and its relationship to mean age. J Geophys Res. 2000;105:6773–6782. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.