Abstract

Common methods to identify yeast cells containing the prion form of the Sup35 translation termination factor, [PSI+], involve a nonsense suppressor phenotype. Decreased function of Sup35p in [PSI+] cells leads to readthrough of certain nonsense mutations in a few auxotrophic markers, for example, ade1-14. This readthrough results in growth on adenine deficient media. While this powerful tool has dramatically facilitated the study of [PSI+], it is limited to a narrow range of laboratory strains and cannot easily be used to screen for cells that have lost the [PSI+] prion. Therefore we have engineered a nonsense mutation in the widely used URA3 gene, termed the ura3-14 allele. Introduction of the ura3-14 allele into an array of genetic backgrounds, carrying a loss-of-function URA3 mutation and [PSI+], allows for growth on media lacking uracil, indicative of decreased translational termination efficiency. This ura3-14 allele is able to distinguish various forms of the [PSI+] prion, called variants and is able to detect the de novo appearance of [PSI+] in strains carrying the prion form of Rnq1p, [PIN+]. Furthermore, 5-fluoorotic acid, which kills cells making functional Ura3p, provides a means to select for [psi−] derivatives in a population of [PSI+] cells marked with the ura3-14 allele, making this system much more versatile than previous methods.

Keyword list: nonsense suppression, [PIN+], prion, [PSI+], Saccharomyces cerevisiae, SUP35, ura3-14

Introduction

[PSI+] is the misfolded infectious prion form of the Sup35 protein (Sup35p) and converts properly folded, functional Sup35p into an aggregated, non-functional form. Sup35p, in conjunction with Sup45p, is required for translational termination at stop codons (UAA, UGA, UAG) [Stansfield et al., 1995; Zhouravleva et al., 1995]. Partial inactivation of Sup35p, by the presence of [PSI+], leads to translational readthrough or suppression of some premature stop codons (nonsense mutations).

Many Mendelian mutations in tRNA or ribosomal protein genes lead to the suppression of a large number of nonsense mutations. Suppression of several nonsense mutations in [PSI+] cells was initially only observed in the presence of the weak tRNA suppressor, SUQ5 [Cox, 1965; Liebman et al., 1975]. However, it was later realized that [PSI+] suppresses a limited number of alleles without SUQ5 [Liebman and Sherman; 1979] and the ability of an allele to be suppressed and the efficiency of suppression depends upon the context surrounding the premature stop codon [Liebman and Sherman, 1979; Firoozan et al., 1991].

In recent years, readthrough of a few nonsense alleles in auxotrophic markers has been exploited in order to score for the presence of the [PSI+] prion. For example, in the presence of SUQ5 and the ade2-1 (UAA) allele, or the ade1-14 (UGA) allele by itself, [PSI+] cells are white on rich media and grow on synthetic media lacking adenine (-Ade), whereas cells that lack [PSI+], called [psi−], are red on rich media and do not grow on –Ade [Cox, 1965; Inge-Vechtomov et al., 1988; Chernoff et al., 1995].

The N-terminal region of the Sup35 protein (Sup35N) is required for the maintenance of [PSI+], and overproduction leads to the de novo appearance of the prion [Ter Avenesyan et al., 1993; Chernoff et al., 1993; Wickner, 1994; Derkatch et al., 1996]. Different [PSI+] variants, distinguished on the basis of the efficiency with which they suppress the ade1-14 allele, were induced by Sup35N overproduction: strong [PSI+] promotes more rapid growth than weak [PSI+] on –Ade [Derkatch et al., 1996; Zhou et al., 1999]. Additionally, there is less soluble Sup35p found in strong [PSI+] than in weak [PSI+] cells [Zhou et al., 1999; Uptain et al., 2001]. Thus, strong [PSI+] cells, with less Sup35p available for use in proper translational termination, readthrough nonsense codons more efficiently. Not only are these phenotypic differences heritable but they are also associated with distinct structural forms of aggregated Sup35p [Tanaka et al., 2005; Krishnan and Lindquist, 2005; Liebman 2005].

[PIN+], which stands for [PSI+] inducibility, is the prion form of the Rnq1 protein that enhances the de novo appearance of [PSI+] [Derkatch et al., 2001; Sondheimer and Lindquist, 2000]. Overexpression of Sup35N in [PIN+], but not [pin−], strains leads to the appearance of [PSI+] [Derkatch et al., 1997]. Like [PSI+], the [PIN+] prion can exist in different variant states: low [PIN+], medium [PIN+], high [PIN+] and very high [PIN+] [Bradley et al., 2002]. The [PIN+] variants promote the de novo appearance of [PSI+] with the efficiencies indicated by their names. In strains carrying the ade1-14 mutation, these differences are detected by the level of growth on –Ade media.

The use of the ade1-14 or ade2-1 mutations to score for [PSI+] and to detect [PIN+] through the appearance of [PSI+], has dramatically facilitated the study of prions in yeast. On the other hand, [PSI+] detection has been limited to a few laboratory yeast strains containing a [PSI+] suppressible allele. Therefore, we have engineered a [PSI+] suppressible nonsense mutation in the URA3 gene, which not only provides a means to screen for [PSI+] in a wide range of strains but also allows one to select for cells that have lost the [PSI+] prion.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and construction

The pCI-HA(URA3)-2 plasmid was kindly provided by Chikashi Ishioka [Ishioka et al., 1997]. This plasmid (ori AmpR CEN ARS LEU2 URA3) contains a PGK promoter followed by a start codon (ATG), a BamHI site, the URA3 coding sequence from amino acid 5 to the wild type stop codon, and the PGK terminator. Sequences can be inserted into the BamHI site to identify mutations that produce truncated products. We took advantage of this system and inserted the nonsense mutation found in ade1-14, and surrounding sequences, into this region (Figure 1). Two reverse complimentary primers were designed to make a double stranded adapter (primer A. TTTTTTGGATCCGAGGTGCTAACGCCAGACTCCTCTAGATTCTGAAACGGTGC CTCTTATAAGGTAGGAGAATCCAAGCTTGGATCCTTTTTT; primer B AAAAAAGGATCCAAGCTTGGATTCTCCTACCTTATAAGAGGCACCGTTTCAGA ATCTAGAGGAGTCTGGCGTTAGCACCTCGGATCCAAAAAA). Primers, added together in equimolar amounts, boiled for 10 min, and allowed to cool to room temperature were cut with BamHI and inserted into pCI-HA(URA3)-2. Insertion of the adapter was detected by digestion with HindIII, and the insert sequence and orientation was verified by Automated DNA sequencing (University of Chicago). The new plasmid is called pLEU2ura3-14.

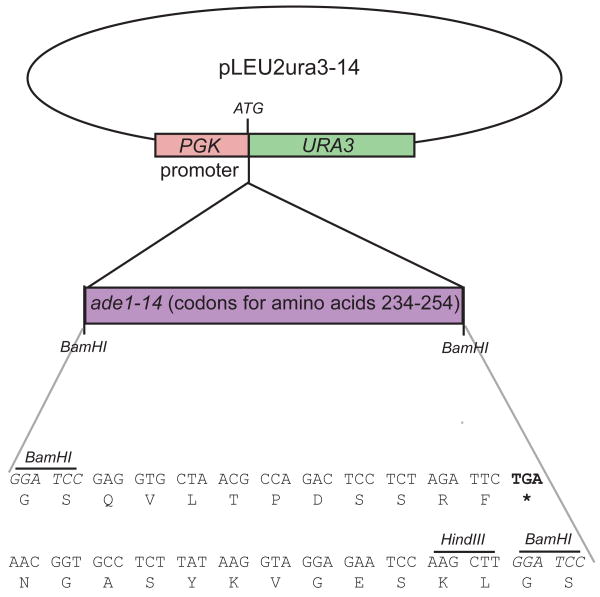

Figure 1.

Construction of the ura3-14 allele. An 81 nucleotide region from the ade1-14 allele was inserted into the BamHI site of pCI-HI(URA3)-2 from Ishioka et al. (2002). Codons from ade1-14 were placed in frame with the URA3 gene starting at codon 5 as shown. The nonsense codon (TGA) within the ade1-14 region is indicated in bold.

Overexpression of the N-terminal and middle domains of Sup35 (Sup35NM) fused to GFP was used to induce [PSI+]. p1181 is a copper inducible plasmid carrying the fusion (CEN HIS3 ori ARS AmpR pCup-Sup35NM:GFP) [Sondheimer and Lindquist, 2000; Derkatch et al., 2001].

Cultivation procedures

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains were subjected to standard media and cultivation protocols [Sherman et al., 1986]. Cells were grown at room temperature (21°C). Suppression of the ura3-14 allele by [PSI+] appeared to be less efficient at 30°C than at 21°C. Synthetic complete media contained dextrose and the required amino acids.

Strains (leu2 his3 ura3) transformed with pLEU2ura3-14 or both pLEU2ura3-14 and p1181 were maintained on synthetic complete media lacking leucine (–Leu) or lacking leucine and histidine (–Leu-His), respectively, and assayed for [PSI+] suppression on –Ura-Leu media. [psi−] derivatives of the strains grew on -Leu 5′ FOA media made according to Rose et al. (1990).

Strains

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The ade1-14 mutation was introduced into the W303 background by Osherovich and Weissman (2001). BY4742 strains were obtained from Open Biosystems. [psi−] [pin−], [PSI+] [pin−] and [psi−] [PIN+] versions of the 74-D694 strain were made by Bradley et al. (2002).

Table 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Lab Name | Genotype |

|---|---|---|

| W303 | GF657 | Mataade1-14 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 trp1-1 his3-11,15 can1-100 |

| SL1010-1A | L1832 | Mataade1-14 leu2-1 ura3-52 trp1-1 his5-2 met8-1 |

| 74-D694 | L1751 | Mataade1-14 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 trp1-289 his3-200 |

| 64-D697 | L1754 | Matα ade1-14 leu2-3, 112 ura3-52 trp1-289 lys9-A21 |

| BY4742 | L2792 | Matα his3 leu2 ura3 lys2 met15::KanMX |

[PSI+] versions of BY4742 were made by cytoduction of cytoplasm from a [rho+] donor cell to a [rho°] recipient cell, where the donor carries the kar1-1 allele to inhibit nuclear fusion [Conde and Fink, 1976]. Donor strains (C10H49a Matα ade2-1 SUQ leu1 his3-11, 15 kar1 lys1-1 cyhR) were mated to recipients in excess overnight. Cytoductants and diploids were selected by growth on synthetic media using glycerol as the sole carbon source but lacking amino acids required by the donor. Cytoductants were distinguished from diploids based on auxotrophic markers.

Induction of [PSI+]

[psi−] [pin−], [psi−] low [PIN+], [psi−] medium [PIN+], [psi−] high [PIN+], and [psi−] very high [PIN+] versions of 74-D694 were co-transformed with pLEU2ura3-14 and p1181 (pCup-Sup35NM:GFP HIS3) plasmids. Cells initially grown on -Leu-His were induced twice by replica plating onto –Leu-His plus 50 μM copper sulfate plates for two days and then velveteen replica plated to –Ura-Leu at room temperature for up to two weeks to score for growth, which indicates [PSI+] appearance.

Distinguishing [PSI+] from Mendelian suppressor mutants

Mendelian suppressor mutations can be conveniently distinguished from [PSI+] since they cannot be cured by guanidine hydrochloride, a chaotropic agent that appears to eliminate prions through the inactivation of Hsp104 [Tuite et al., 1981; Jung and Masison, 2001; Bradley et al., 2003]. Cells were cured by streaking on YPD plus 5mM guanidine hydrochloride twice and then plating on –Ura and –Ade media to check for suppression.

Results

Obtaining a [PSI+] suppressible allele in the URA3 gene

Previous studies indicated that the context in which a nonsense codon exists affects the efficiency that it can be readthrough [Namy et al., 2003]. Therefore, it is likely that many site-directed stop codon mutations may not be [PSI+] suppressible. Thus, we randomly mutagenized the URA3 gene with ultraviolet light and designed a screen to uncover [PSI+] suppressible nonsense mutations (unpublished). When these screens failed, we took another approach. Knowing that fusions to the N-terminus of the URA3 gene do not inactivate function [Ishioka et al., 1997], we fused a piece of the ade1-14 locus containing the [PSI+] suppressible nonsense mutation to the 5′ end of URA3 (see Materials and Methods; Figure 1). The ade1-14 allele contains a substitution at nucleotide 732, changing the coding tryptophan (TGG) to a TGA stop codon [Inge-Vectomov et al., 1988; Nakayashiki et al., 2001]. The nonsense mutation and ten adjacent upstream and downstream codons were fused to the URA3 gene and we have termed this allele ura3-14.

[PSI+] causes suppression of the ura3-14 allele

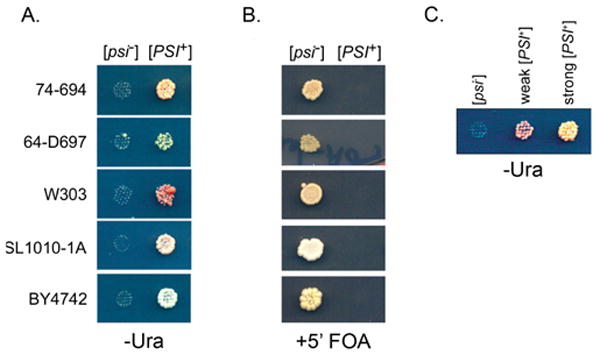

The plasmid was transformed into [PSI+] and [psi−] versions of four strains: 74-D694, 64D-697, W303 and SL1010-1A. Each of these strains contains the ade1-14 allele and a ura3 mutation. As expected, [PSI+], but not [psi−], strains grew on –Ade media (data not shown). Similarly, only [PSI+] strains grew on –Ura (Figure 2a). Thus, the ura3-14 allele is suppressed by [PSI+]. Likewise, when BY4742, the MATα ura3 yeast deletion library strain carrying the ura3-14 plasmid was tested, only [PSI+], and not [psi−], versions grew on –Ura.

Figure 2.

The presence and absence of [PSI+] can be scored by the ura3-14 allele. A. [psi−] and [PSI+] versions of five different ura3 strains carrying the pLEU2ura3-14 plasmid were replica plated on –Ura-Leu media at 21°C. Pictures shown were taken at 7 days of growth for 74-D694 and SL1010-1A, 11 days for 64D-697 and W303, and two weeks for BY4742. It should be noted that the same 74D-694 strain took about five days to grow on –Ade under similar conditions (data not shown). B. [PSI+] or [psi−] derivatives carrying the pLEU2ura3-14 plasmid were plated on + 5′FOA media. Plate shown after 7 days of growth. C. [psi−], weak [PSI+] and strong [PSI+] versions of 74-D694 (ade1-14 ura3-52 leu2-3,112) carrying the pLEU2ura3-14 plasmid were replica plated onto –Ura-Leu plates. It should be noted that while strong [PSI+] showed growth after 7 days, weak [PSI+] did not appear until approximately 14 days (as shown in picture). Strong [PSI+] also grew better than weak [PSI+] in the 64D-697 and BY4742 genetic backgrounds (data not shown).

Screening for the absence of [PSI+]

The suppressible ura3-14 allele now makes it possible to directly select for cells that have lost the [PSI+] prion. The wild type URA3 gene converts 5′fluoroorotic acid (5′FOA) into the toxic compound, 5-fluorouracil [Boeke et al., 1984]. Therefore, [PSI+] strains that suppress the ura3-14 allele will produce Ura3p and die on 5′FOA media, as they produce the toxin; [psi−] cells will not make Ura3p and will grow on media containing 5′FOA as shown in Figure 2b.

Characterization of [PSI+] variants using the ura3-14 allele

As mentioned earlier, different variants of [PSI+] suppress the ade1-14 allele with different efficiencies. Likewise, strong [PSI+] can be distinguished from weak [PSI+] variants with the ura3-14 allele. The strong [PSI+] versions grew better on –Ura than weak [PSI+] versions in the same genetic background (Figure 2c).

Identification of the de novo appearance [PSI+] in [PIN+] strains

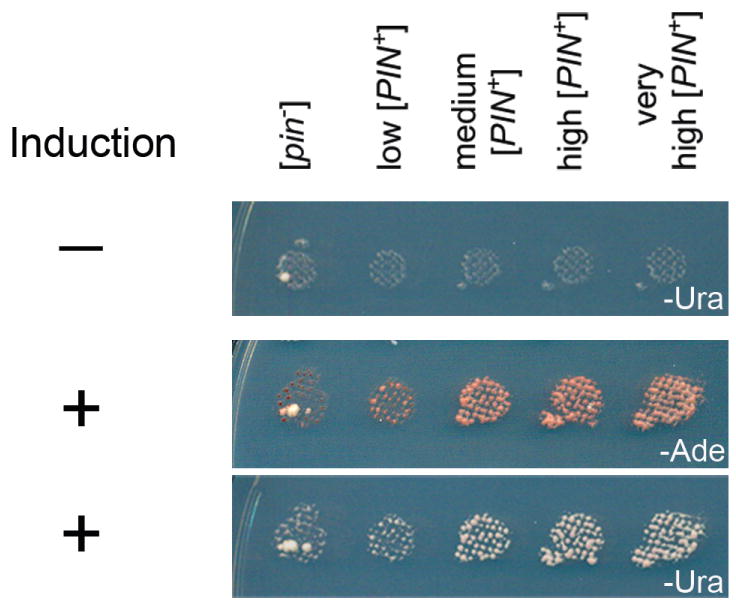

Four [PIN+] variant and [pin−] versions of 74-D694 were co-transformed with the ura3-14 plasmid and a plasmid that has Sup35NM under the control of a CUP1 promoter. As shown previously, following overproduction of Sup35NM, [PIN+] strains, but not [pin−] strains, grew on –Ade, indicative of [PSI+] induction [Bradley et al., 2002]. Control cells in which Sup35NM was not overproduced did not show significant growth on –Ade [Derkatch et al., 1997]. Similar results were obtained using the ura3-14 allele, instead of ade1-14 to score for [PSI+] appearance (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The ura3-14 allele can be used to screen for the induction of [PSI+] in strains carrying different variants of [PIN+]. [psi−] 74-D694 strains carrying the indicated variants of [PIN+], the pLEU2ura3-14 plasmid and the Sup35NM:GFP plasmid, were either plated directly onto –Ura-Leu media without copper induction (−), or induced on copper and then plated onto –Ade or –Ura-Leu media (+). Pictures of uninduced and induced strains were taken after 7 days of growth. Ura+ colonies appearing in [pin−], and not [PIN+] strains, continued to grow on –Ura media after curing on guanidine hydrochloride, indicating that these colonies were Mendelian suppressors and not [PSI+]. Cells growing in induced [PIN+] strains were confirmed to be [PSI+] since they did not grow on –Ura-Leu after curing (see Materials and Methods, data not shown).

Discussion

The method described above using the ura3-14 allele in a ura3 mutant strain provides several advantages when compared to traditional methods for scoring for [PSI+]. This allele is not only suppressed by [PSI+] in a range of strain backgrounds, but does not require a secondary suppressor like SUQ5, and therefore can be transformed into any ura3 mutant or deletion that does not grow on uracil. In addition, the plasmid can be used to screen for [PSI+] in libraries available to the yeast community including the Yeast disruption library [Winzeler et. al., 1999], the HA-tagged library [Ross-Macdonald, et. al., 1999] and the GFP tagged library [Huh, et al., 2003].

A genomically integrated version of this allele is expected to be functional, since the [PSI+] suppressed ura3-14 allele on a plasmid used is able to compensate for a mutated or fully deleted URA3 gene like those found in the 74-D694 and BY4742 strains, respectively. The construction of a [PSI+] suppressible marker is not limited to the URA3 gene. By placing the nonsense mutation and surrounding codons of the ade1-14 gene into any other gene, one can potentially engineer other genes that can be suppressed by [PSI+].

Previously, there were few genetic methods to select or screen for the loss of the [PSI+] prion from a [PSI+] population. The can1-100 allele (UAA) confers resistance to the drug canavanine. In the presence of SUQ5, this allele is [PSI+] suppressible, allowing for the selection of [psi−] derivatives that are canavanine resistant. However, this method is limited to a small number of strains bearing both the SUQ5 and can1-100 mutations [Liebman et al., 1975; Cox et al., 1980; Wilson et al., 2005]. In strains carrying the ade1-14 mutation, cells that have lost [PSI+] can be scored by spreading cells on rich media and manually selecting red colored colonies. This method is both labor intensive and cumbersome for screening a large number of samples and requires cells to carry the ade1-14 allele. Since ura3 mutations are prevalent in laboratory strains, introduction of the ura3-14 allele easily allows for [psi−] cells to be directly selected from a population by growth on 5′FOA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM56350 (to S.W.L) and National Institutes of Health NSRA F32 postdoctoral fellowship GM072340 (to A.L.M).

References

- Boeke JD, LaCroute F, Fink GR. A positive selection for mutants lacking orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase activity in yeast: 5-fluoro-orotic acid resistance. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;197:345–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00330984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley ME, Edskes HK, Hong JY, Wickner RB, Liebman SW. Interactions among prions and prion “strains” in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16392–16399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152330699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley ME, Bagriantsev S, Vishveshwara N, Liebman SW. Guanidine reduces stop codon read-through caused by missense mutations in SUP35 or SUP45. Yeast. 2003;20:625–32. doi: 10.1002/yea.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff YO, Lindquist SL, Ono B, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Liebman SW. Role of the chaperone protein Hsp104 in propagation of the yeast prion-like factor [PSI+] Science. 1995;12:880–884. doi: 10.1126/science.7754373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde J, Fink GR. A mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae defective for nuclear fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:3651–3655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox BS. [PSI+] A cytoplasmic suppressor of super-suppressors in yeast. Heredity. 1965;20:505–521. [Google Scholar]

- Cox BS, Tuite MF, Mundy CJ. Reversion from suppression to nonsuppression in SUQ5 [psi+] strains of yeast: The classfication of mutations. Genetics. 1980;95:589–609. doi: 10.1093/genetics/95.3.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkatch IL, Chernoff YO, Kushnirov VV, Inge-Vectomov SG, Liebman SW. Genesis and variability of [PSI+] prion factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1996;144:1375–1386. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkatch IL, Bradley ME, Zhou P, Chernoff YO, Liebman SW. Genetic and environmental factors affecting the de novo appearance of the [PSI+] prion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1997;147:507–519. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkatch IL, Bradley ME, Hong JY, Liebman SW. Prions affect the appearance of other prions: the story of [PIN+] Cell. 2001;93:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firoozan M, Grant CM, Duarte JA, Tuite MF. Quantitation of readthrough of termination codons in yeast using a novel gene fusion assay. Yeast. 1991;7:173–83. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh WK, Falvo JV, Gerke LC, Carroll AS, Howson RW, Weissman JS, O'Shea EK. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003;425:686–691. doi: 10.1038/nature02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inge-Vechtomov SG, Tikhodeev ON, Karpova TS. Selective systems for obtaining recessive ribosomal suppressors in Saccharomyces yeasts. Genetika. 1988;24:1159–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishioka C, Suzuki T, FitzGerald M, Krainer M, Shimodaira H, Shimada A, Nomizu T, Isselbacher KJ, Haber D, Kanamaru R. Detection of heterozygous truncating mutations in the BRCA1 and APC genes by using a rapid screening assay in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;18:2449–2453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung G, Masison DC. Guanidine hydrochloride inhibits Hsp104 activity in vivo: a possible explanation for its effect in curing yeast prions. Current Microbiology. 2001;43:7–10. doi: 10.1007/s002840010251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan R, Lindquist SL. Structural insights into a yeast prion illuminate nucleation and strain diversity. Nature. 2005;435:765–72. doi: 10.1038/nature03679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebman SW, Stewart JW, Sherman F. Serine substitutions caused by an ochre suppressor in yeast. J Mol Biol. 1975;94:595–610. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebman SW, Sherman F. Extrachromosomal PSI+ determinant suppresses nonsense mutations in yeast. J Bacteriol. 1979;139:1068–1071. doi: 10.1128/jb.139.3.1068-1071.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebman SW. Structural clues to prion mysteries. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:567–568. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0705-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayashiki T, Ebihara K, Bannai H, Nakamura Y. Yeast [PSI+] “prions” that are cross transmissible and susceptible beyond a species barrier through a quasi-prion state. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1121–30. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namy O, Duchateau-Nguyen G, Hatin I, Hermann-Le Denmat S, Termier M, Rousset JP. Identification of stop codon readthrough genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nuclear Acids Res. 2003;106:2289–2296. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osherovich LZ, Weissman JS. Multiple Gln/Asn-rich prion domains confer susceptibility to induction of the yeast [PSI(+)] prion. Cell. 2001;106:183–194. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose MD, Winston F, Hieter P. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ross-Macdonald P, Coelho PS, Roemer T, Agarwal S, Kumar A, Jansen R, Cheung KH, Sheehan A, Symoniatis D, Umansky L, Heidtman M, Nelson FK, Iwasaki H, Hager K, Gerstein M, Miller P, Roeder GS, Snyder M. Large-scale analysis of the yeast genome by transposon tagging and gene disruption. Nature. 1999;402:413–418. doi: 10.1038/46558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F, Fink GR, Hicks JB. Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sondheimer N, Lindquist SL. Rnq1: an epigenetic modifier of protein function in yeast. Mol Cell. 2000;5:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansfield I, Jones KM, Kushnirov VV, Dagkesamanskaya AR, Poznyakovski AI, Paushkin SV, Nierras CR, Cox BS, Ter-Avanesyan MD, Tuite MF. The products of the SUP45 (eRF1) and SUP35 genes interact to mediate translation termination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1995;14:4365–73. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Chien P, Yonekura K, Weissman JS. Mechanism of cross-species prion transmission: an infectious conformation compatible with two highly divergent yeast prion proteins. Cell. 2005;121:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ter-Avanesyan A, Kushnirov VV, Dagkesamanskaya AR, Didichenko SA, Chernoff YO, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Smirnov VN. Deletion analysis of the SUP35 gene of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals two non-overlapping functional region sin the encoded protein. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:683–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuite MF, Mundy CR, Cox BS. Agents that cause a high frequency of genetic change from [psi+] to [psi−] in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1981;98:691–711. doi: 10.1093/genetics/98.4.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uptain SM, Sawicki GJ, Caughey B, Lindquist SL. Strains of [PSI+] are distinguished by their efficiencies of prion-mediated conformational conversion. EMBO J. 2001;20:6236–6245. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.22.6236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner RB. [URE3] as an altered URE2 protein: evidence for a prion analog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 1994;264:566–569. doi: 10.1126/science.7909170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner RB, Liebman SW, Saupe SJ. Prion Biology and Disease. 2nd. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2004. Prions of yeast and filamentous fungi: [URE3], [PSI+], [PIN+] and [Het-s] pp. 305–372. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MA, Meaux S, Parker R, van Hoof A. Genetic interactions between [PSI+] and nonstop mRNA decay affect phenotypic variation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;109:10244–10249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504557102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzeler EA, Shoemaker DD, Astromoff A, Liang H, Anderson K, Andre B, Bangham R, Benito R, Boeke JD, Bussey H, Chu AM, Connelly C, Davis K, Dietrich F, Dow SW, El Bakkoury M, Foury F, Friend SH, Gentalen E, Giaever G, Hegemann JH, Jones T, Laub M, Liao H, Liebundguth N, Lockhart DJ, Lucau-Danila A, Lussier M, M'Rabet N, Menard P, Mittmann M, Pai C, Rebischung C, Revuelta JL, Riles L, Roberts CJ, Ross-MacDonald P, Scherens B, Snyder M, Sookhai-Mahadeo S, Storms RK, Veronneau S, Voet M, Volckaert G, Ward TR, Wysocki R, Yen GS, Yu K, Zimmermann K, Philippsen P, Johnston M, Davis RW. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science. 1999;285:901–906. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P, Derkatch IL, Uptain SM, Patino MM, Lindquist SL, Liebman SW. The yeast non-mendelian factor [ETA+] is a variant of [PSI+], a prion-like form of release factor eRF3. EMBO J. 1999;18:1182–1191. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhouravleva G, Frolova L, Le Goff X, Le Guellec R, Inge-Vechtomov S, Kisselev L, Philippe M. Termination of translation in eukaryotes is governed by two interacting polypeptide chain release factors, eRF1 and eRF3. EMBO J. 1995;14:4065–72. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]