Abstract

F1-ATPase is a rotary molecular motor driven by ATP hydrolysis that rotates the γ-subunit against the α3β3 ring. The crystal structures of F1, which provide the structural basis for the catalysis mechanism, have shown essentially 1 stable conformational state. In contrast, single-molecule studies have revealed that F1 has 2 stable conformational states: ATP-binding dwell state and catalytic dwell state. Although structural and single-molecule studies are crucial for the understanding of the molecular mechanism of F1, it remains unclear as to which catalytic state the crystal structure represents. To address this issue, we introduced cysteine residues at βE391 and γR84 of F1 from thermophilic Bacillus PS3. In the crystal structures of the mitochondrial F1, the corresponding residues in the ADP-bound β (βDP) and γ were in direct contact. The βE190D mutation was additionally introduced into the β to slow ATP hydrolysis. By incorporating a single copy of the mutant β-subunit, the chimera F1, α3β2β(E190D/E391C)γ(R84C), was prepared. In single-molecule rotation assay, chimera F1 showed a catalytic dwell pause in every turn because of the slowed ATP hydrolysis of β(E190D/E391C). When the mutant β and γ were cross-linked through a disulfide bond between βE391C and γR84C, F1 paused the rotation at the catalytic dwell angle of β(E190D/E391C), indicating that the crystal structure represents the catalytic dwell state and that βDP is the catalytically active form. The former point was again confirmed in experiments where F1 rotation was inhibited by adenosine-5′-(β,γ-imino)-triphosphate and/or azide, the most commonly used inhibitors for the crystallization of F1.

Keywords: ATP synthase, cross-link

The FoF1-ATP synthase is widely found in biological membranes such as the mitochondrial inner membrane, thylakoid membrane, and bacterial plasma membrane. It catalyzes ATP synthesis from ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pi) at the cost of the electrochemical potential of proton or sodium ion across the membrane (1–6). The synthase is composed of a water-soluble part, F1, and a membrane-embedded part, Fo. F1 is a rotary motor driven by ATP hydrolysis. The subunit composition of bacterial F1 is α3β3γδε. The minimum complex of the rotary motor is the α3β3γ subcomplex that is hereinafter referred to as F1αβγ. Hydrolyzing ATP, F1 rotates the γ-subunit against the α3β3 stator ring in a counterclockwise direction when viewed from the Fo (7). Fo is also a rotary motor that is driven by proton translocation across the membrane, down the electrochemical potential (8, 9). The subunit composition of bacterial Fo is ab2c10–15 in which the c10–15 oligomer ring rotates against the ab2 stator. These 2 rotary motors are connected through the central and peripheral stalks. Under ATP synthesis conditions where the proton electrochemical potential is dominant, Fo forcibly rotates the γ-subunit of F1 in the reverse direction (clockwise when viewed from Fo). This reverse rotation of F1 results in the reverse chemical reaction of ATP hydrolysis, i.e., ATP synthesis. Conversely, under ATP hydrolysis conditions, F1 rotates γ in the anticlockwise direction with the c10–15 ring, forcing Fo to pump protons against the proton electrochemical potential.

The atomic-level structure of F1 was first described in 1994, using a crystal of bovine mitochondrial F1 (MF1) prepared in the presence of ADP, adenosine-5′-(β,γ-imino)-triphosphate (AMP-PNP), and sodium azide (NaN3) (10). This structure, referred to as the “reference structure,” revealed that 3 α-subunits and 3 β-subunits are alternately aligned to form a hetero hexamer ring and the γ-subunit is set into the central cavity of the α3β3 ring. The catalytic sites are located at each αβ interface, mainly on the β-subunit. Each β is in a different conformational state depending on the bound substrate; one binds to AMP-PNP (βTP), another to ADP (βDP), and the third to none (βempty). Both βTP and βDP are in the closed conformation where the C-terminal domain swings toward the nucleotide-binding domain to close the cleft between these domains. As a result, these β-subunits wrap the bound nucleotide tightly. In contrast, βempty adopts an open conformation to weaken the affinity to the nucleotide. These structural features agree well with the binding change mechanism (5), which assumes that each catalytic site is in a different catalytic state and the interconversion of catalytic states drives the rotary motion of the γ-subunit, although there are some inconsistencies (11). Since this work, many crystal structures of MF1 with different chemical inhibitors have been reported. The crystal structure that differs most from the reference structure is that which has ADP·AlF4−, where βempty binds to ADP to adopt the half-closed conformation and the γ is twisted by −20° (12). However, all other MF1 structures have very similar conformations to the reference structure. Thus, the crystal structures of MF1 essentially represent a certain stable conformational state of F1 except for the ADP·AlF4−-bound MF1 structure.

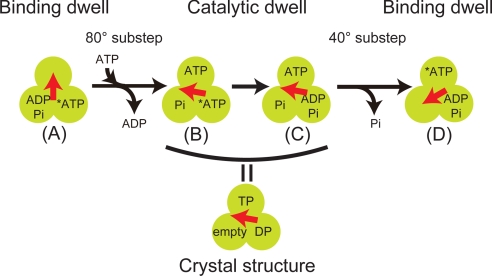

In contrast, single-molecule studies on the γ rotation of F1 have revealed that F1 has 2 distinct stable conformations. Since the observation that F1 performs a 120° step rotation of γ upon hydrolysis of 1 ATP, intensive attempts have been made to resolve the 120° step into multiple substeps to allow better understanding of how the elementary catalytic steps are coupled with the mechanical rotation. In many of these studies including this one, F1αβγ from thermophilic Bacillus PS3 (TF1) have been used because TF1 is stable under the harsh conditions of the single-molecule experiments and can be genetically modified. Thus far, 2 substeps have been found: the 80° and 40° substeps. High-speed imaging of the rotation (13) and a study of a mutant F1 having a noticeably low ATP hydrolysis rate (14) revealed that the 80° substep is induced by ATP binding and that the 40° substep was initiated after hydrolysis of bound ATP. Hereinafter, the 2 conformational states before the 80° or 40° substeps are referred to as the “binding dwell state” and “catalytic dwell state,” respectively. Recent studies have suggested that ADP release and Pi release occur at the binding dwell angle and catalytic dwell angle, respectively (15, 16). More recently, a temperature-sensitive reaction was found at the binding dwell angle in a rotation assay at low temperature (16).

Thus, single-molecule studies have revealed that F1 has 2 stable conformational states, whereas F1 adopts essentially 1 specific stable conformation in the crystal structure. Which conformational state do the crystal structures of F1 represent, binding dwell state, catalytic dwell state, or another new state? On this issue, there are some interesting results. The analysis of fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between fluorescent probes attached to β and γ suggests that the crystal structure probably corresponds to the catalytic dwell state (17). However, FRET measurement provides the relative distance between the fluorophores, but not the precise position in the 3D structure. Therefore, this result is not conclusive. The reference structure was recently revised to show that βDP binds to N3− at the γ-phosphate binding position (18), implying that F1 in the crystal structure is in the azide-stabilized form, while the feature of this structure was later revealed to be almost consistent with that of the catalytic ground state MF1 (19). Taking into account that F1 pauses at the catalytic angle when in the ADP-inhibited form (20), it seems plausible that the crystal structure is in the catalytic dwell state. However, there are no experimental results that clarify this point. In fact, a common view on the nature of crystal structure of the F1 has not been established yet: some postulate it to be in the binding dwell state (21, 22) and others think it is the catalytic dwell state (23, 24).

With an aim to addressing this issue, we generated a mutant F1αβγ from Bacillus PS3 in which cysteine residues were introduced at βE391 and γR84, respectively (25). In the crystal structures of bovine MF1, corresponding residues in the ADP-bound β (βDP) and the γ are in direct contact (18, 19, 22, 26). The residue of γR84 is a part of the “ionic track” (25, 27), which is the distinctive zonation of positively-charged residues around the axis of γ. It is postulated that β bends and unbends its conformation, tracing the ionic track with the negative charges of βD394 and βE395 (for MF1) so as to convert the bending motion of β into the rotary motion of γ (27). The importance of the ionic track is supported by the analysis of mutant F1αβγ in which βE391 and γR84 are substituted with cysteine (25). Thus, the direct contact between βE391 and γR84 is the representative βDP–γ interaction in the conformational state of the crystal structure. In this study, F1αβγ with βE391C and γR84C mutations was investigated in a single-molecule rotation assay to observe where it pauses when the introduced cysteine residues form a disulfide bond, thereby fixing the motor in the conformational state corresponding to the conformational state of the crystal structures. In addition to the cross-link experiment, the correlation between the crystal structures and the single-molecule experiment was studied by investigating at which angle F1αβγ stops rotation in the presence of AMP-PNP and/or NaN3, the most commonly used chemicals for the crystallization of F1.

Results

A Chimera F1αβγ, α3β2β(E190D/E391C)γ(R84C).

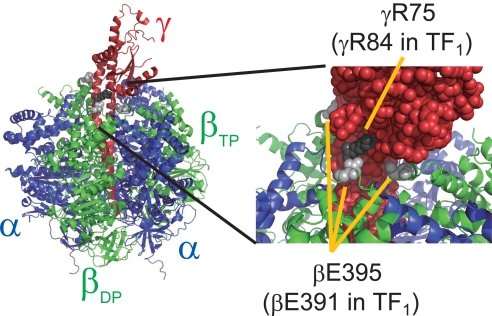

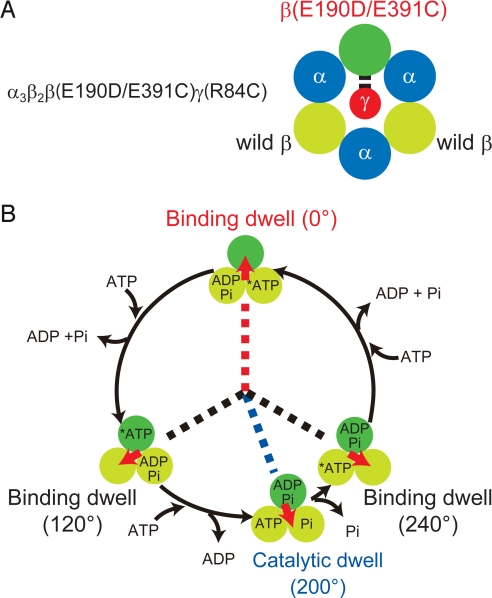

A mutant F1αβγ from Bacillus PS3 was prepared in which cysteine residues were introduced at βE391 and γR84, which correspond to the βE395 and γR75 of bovine MF1, respectively. In the crystal structure of bovine MF1, these 2 residues are in direct contact (Fig. 1). Although the whole structure of TF1 has not been solved, it is most likely that TF1 structure is very similar to MF1, and that βE391 and γR84 of TF1 are also in a very close proximity when TF1 takes the conformational state corresponding to the crystal structure of MF1. This is because F1 from other species shows structural features essentially identical to that of MF1 even if the amino acid sequence is not highly homologous to that of MF1, as seen in the γ subunit of F1 from Escherichia coli (EF1): The structure of the γ of EF1 is very similar to that of MF1 (28), although the sequence homology against the γ of MF1 is low (only ≈30%) the same as the γ of TF1. Furthermore, the sequences around βE391 and γR84 are highly conserved in many species, suggesting the high structural conservation of these regions (Figs. S1 and S2). When βE391 and γR84 of F1αβγ from Bacillus PS3 were replaced with cysteine residues, they efficiently (≈90%) formed a disulfide bond under oxidizing conditions within only a few minutes (25). Thus, it is reasonable to assume that TF1 has the essentially identical structural features to MF1. In the MF1 crystal structure, the β that has direct contact with γR75 adopts the βDP form. The γ-carbons of these residues that are in equivalent positions to the sulfur atoms of cysteine residue are only 5.9 Å away (Table 1), which is sufficiently close for disulfide bond formation. In contrast, the distances in the βTP– or βempty–γ pairs are 11 and 23 Å, respectively. Thus, the disulfide bond would be formed in the βDP–γ pair. In the single-molecule rotation assay, γ was actually cross-linked to β only when the β was in a specific catalytic state, revealed to be the catalytic dwell state (see below). Furthermore, E190D mutation was introduced to the β-subunit in addition to E391C mutation. The mutant β(E190D/E391C)* was reconstituted with the wild-type β to build a chimera F1αβγ, α3β2β(E190D/E391C)γ(R84C), which has a single copy of β(E190D/E391C) (Fig. 2A). Here, the βE190D mutation was used as an angular position marker to determine the pause angle of cross-linked F1αβγ. Shimabukuro et al. (14) showed that the βE190D mutation severely slows the hydrolysis step and causes the long pause (τ = 320 ms) at the catalytic angle. When a single copy of β with E190D mutation is incorporated in F1αβγ, the reconstituted chimera F1αβγ exhibits a transient pause at the catalytic dwell angle of βE190D that is +200° from the angle at which the βE190D subunit binds to ATP (Fig. 2B) (29). Thus, a chimera F1αβγ with a single β(E190D) enables us to determine the pause angle of the cross-linked F1αβγ relative to the catalytic angle of β(E190D). It should be noted that a chimera F1αβγ with 1 β(E190D) was reported to exhibit another short pause at +120° from the catalytic dwell angle of β(E190D) (29). In this study, the short pause is neglected because the time constant of the short pause is too short (τ ≈15 ms) for the recording rate in this study (33 ms per frame).

Fig. 1.

Spatial positions of βE395 (light gray spheres) and γR75 (dark gray spheres) of MF1 in the crystal structure (Protein Data Bank ID code 1e79) (26). These residues correspond to βE391 and γR84 of TF1. The protruding part of the γ is the Fo binding side. The α-subunit is shown in blue, the β-subunit is green, and the γ-subunit is red. To show the βE395 and γR75 residues, R33, D74, D110, R113, R133, R134, and P135 residues of the γ were removed. The figure was produced with Pymol.

Table 1.

Distance between γ-carbons of βE395 and γR75 in crystal structures of MF1

| Protein Data Bank ID code | Ref. | Distance, Å | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| βTP | βDP | βempty | ||

| 1e79 | 26 | 11.2 | 6.1 | 25.1 |

| 1h8e | 12 | 11.1 | 6.0 | 17.8 |

| 1w0j | 22 | 11.2 | 6.0 | 24.8 |

| 2ck3 | 18 | 10.8 | 5.7 | ND |

| 2jdi | 19 | 11.0 | 5.8 | ND |

| 11.0 ± 0.2* | 5.9 ± 0.2* | 22.6 ± 4.1* | ||

ND, not determined because E395 in βempty was not visible in these structures.

*Average ± SD.

Fig. 2.

The chimera F1αβγ, α3β2β(E190D/E391C)γ(R84C). (A) Schematic image of the chimera F1αβγ, α3β2β(E190D/E391C)γ(R84C) used in the cross-link experiment. Short black prongs denote cysteine residues at βE391 and γR84 for disulfide bond formation. (B) Circular diagram of the reaction and rotation of the chimera F1αβγ. At 0°, the mutated β, β(E190D/E391C), binds ATP (red dotted line) and makes the long catalytic dwell at 200° (blue dotted line) casued by slowed ATP hydrolysis by the βE190D mutation (29). The wild-type β-subunits bind ATP at 120° or 240° (black dotted lines). The catalytic dwells by the wild-type β-subunits at 80° or 320° were too short (only 1 ms) to detect with the present recording system (33 ms per frame) and are not shown.

Pausing Position of the Cross-Linked F1αβγ.

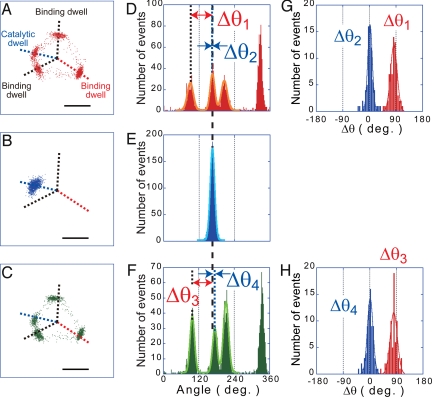

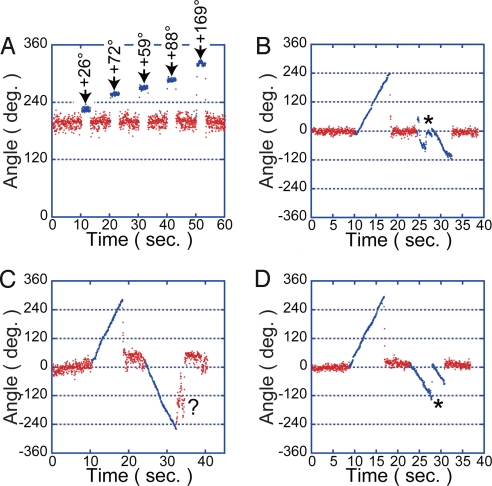

The rotation assay of α3β2β(E190D/E391C)γ(R84C) was carried out under a substrate-limiting condition, at 200 nM ATP. Because the other kinds of chimera F1αβγ, which carry 2, 3, or 0 of β(E190D/E391C) contaminated in the rotation assay, α3β2β(E190D/E391C)γ(R84C) was identified based on 2 criteria. (i) The existence of obvious pauses in every turn at the 3 binding angles, 120° apart from each other. (ii) The existence of the clear pause in every turn at a catalytic angle, which divides 1 of 3 120° steps into the 80° and 40° substeps in this order (not 40° and 80° substeps) (Fig. 3 A and C) (29). In the selection based on the first criterion, >95% of molecules were omitted from the further analysis because of ambiguous stepping. Among selected molecules, 50% showed the clear pausing at a catalytic angle and were identified as the chimera, α3β2β(E190D/E391C)γ(R84C). The remaining were mostly α3β3γ(R84C), of which all β-subunits were wild type, because the other chimera F1αβγ molecules carrying 2 or 3 mutant β-subunits were difficult to find out because of their slow rotary motion and the reconstitution efficiency of the mutant β was lower than that of the wild type as reported (29). Fig. 3 A–F shows a single dataset of the cross-link experiment. First, the free rotation of a α3β2β(E190D/E391C)γ(R84C) molecule was observed to determine the angular position of the catalytic dwell of β(E190D/E391C) and the 3 binding dwell angles (Fig. 3 A and D). Then, an oxidizing buffer containing 3-carboxy-4-nitrophenyl disulfide (DTNB) was injected to the flow chamber to promote a disulfide bond formation between βE391C and γR84C. After the buffer exchange, which took several minutes, a significant fraction of the molecules (≈70%) stopped rotation (Fig. 3 B and E). The remaining would be molecules in which cysteine residue was modified with a biotin that blocks the disulfide bond formation. After observing a pause, a pausing F1αβγ molecule was manipulated with magnetic tweezers to confirm the β–γ cross-linkage (Fig. 4). Unlike ADP-inhibited F1αβγ, cross-linked F1αβγ never resumes rotation, even when forcibly rotated more than +80°, which is sufficient to reactivate ADP-inhibited F1αβγ with nearly 100% efficiency (Fig. 4A) (30). Instead, cross-linked F1αβγ behaved as a twisted spring: when forcibly rotated and released, it just returned to the original pausing position. The angular velocity of return was always very fast (3.8 revolutions per s) and comparable with the ATP-driven rotation velocity at high ATP concentration (≈5 revolutions per s). In rare cases, F1αβγ exhibited irregular behaviors such as large fluctuations at an irregular position (Fig. 4 B–D). Such irregular behaviors were observed in some cases where cross-linked F1αβγ was rotated more than ±120° with the magnetic tweezers. This phenomenon is probably caused by the partial unfolding of the γ- or β-subunits. When the buffer was exchanged with a reducing one, the disulfide bond was cleaved and F1αβγ molecules resumed active rotation (Fig. 3 C and F). Molecules that did not resume rotation or significantly changed their binding dwell angles were omitted from our data analysis. The angle differences of the cross-link angle (Fig. 3E) from the nearest binding angle on the clockwise side (Δθ1 in Fig. 3D) or the catalytic angle of β(E190D/E391C) (Δθ2 in Fig. 3D) were determined. These values were also determined by the comparison with the binding and catalytic dwell angles after reduction (Δθ3 and Δθ4 in Fig. 3F). For this analysis, the set of the experiments was repeated a total of 72 times with 36 molecules. The histograms of Δθ1 and Δθ2 showed a single peak and gave mean values of 82.7 ± 15.9° for Δθ1 and 2.0 ± 11.0° for Δθ2 (Fig. 3G). The histograms of Δθ3 and Δθ4 also gave essentially the same values, 81.3 ± 17.0° for Δθ3 and 1.4 ± 13.5° for Δθ4, showing the reproducibility of the experiment (Fig. 3H). These results show that the cross-linked F1αβγ pauses at the catalytic dwell angle of β(E190D/E391C). This means that the reference structure of MF1 represents the conformational state of F1 in the catalytic dwell state, and that βDP conformation represents the catalytically active state that executes ATP hydrolysis. Considering that the standard deviations are much smaller than the magnitude of the 40° substep, cross-linked F1αβγ will not be stable at the binding angle.

Fig. 3.

β-γ cross-linking experiment in the single-molecule rotation assay. (A–C) The centroid traces of the rotation of a α3β2β(E190D/E391C)γ(R84C) molecule. Data are derived from 60-s recordings. (A) The rotation at 200 nM ATP with 3 binding dwells by all β-subunits and 1 catalytic dwell caused by the β(E190D/E391C). (B) Pause of rotation after cross-linking by disulfide bond between βE391C and γR84C. (C) Rotation resumed after the reduction of the disulfide bond. (Scale bars: 100 nm.) (D–F) Histograms of rotary angle of traces shown in A–C. The angular positions of the pauses were determined by fitting the data with Gaussian curves (orange, light blue, and yellow green lines in D, E, and F, respectively). Then, the angular distance of the cross-link pause (dashed line in E) from the binding dwell angle on the clockwise side (Δθ1) or the catalytic dwell angle of βE391C (Δθ2) of the rotation before cross-link were determined. These distances were again determined by comparison with the rotation after reduction as Δθ3 and Δθ4. (G and H) Histograms of the angular distances (Δθ1 to Δθ4). n = 72 (36 molecules). The means ± SD for Δθ1, Δθ2, Δθ3, and Δθ4 were determined by Gaussian curve fitting (red and blue lines) to be 82.7 ± 15.9°, 2.0 ± 11.0°, 81.3 ± 17.0°, and 1.4 ± 13.5°, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Manipulation of cross-linked F1αβγ with the magnetic tweezers. (A) Time course of the manipulation. Blue dots represent the period for the manipulation. The molecule was clamped at the indicated angle for 3 s in the forward direction and released. (B–D) F1αβγ was rotated at the rate of 36° per s for near or >120° in both directions. When twisted in the backward direction, F1αβγ showed irregular responses. Some resisted the external magnetic field, inversed the magnetic moment of the beads instantaneously (at the point indicated by * in B and D), and then rotated back to the inversed angle of the original magnetic field (B and D), or some paused at irregular positions (indicated by a mark in C) after being released from the field.

Other chimera F1αβγ molecules, α3β(E190D)2β(E391C)γ(R84C) and α3β(E190D)β(E391C)2γ(R84C), were also examined to confirm that γR84C can form a disulfide bond with βE391C, which does not have the βE190D mutation. The rotation of α3β(E190D)2β(E391C)γ(R84C) was rarely seen because of the low reconstitution efficiency of β(E190D) as described above. The cross-linked chimera paused at either of the 2 catalytic angles that did not correspond to the catalytic angle of βE190D (Fig. S3). Thus, it was verified that βE190D mutation does not affect the pause position of cross-linked F1αβγ.

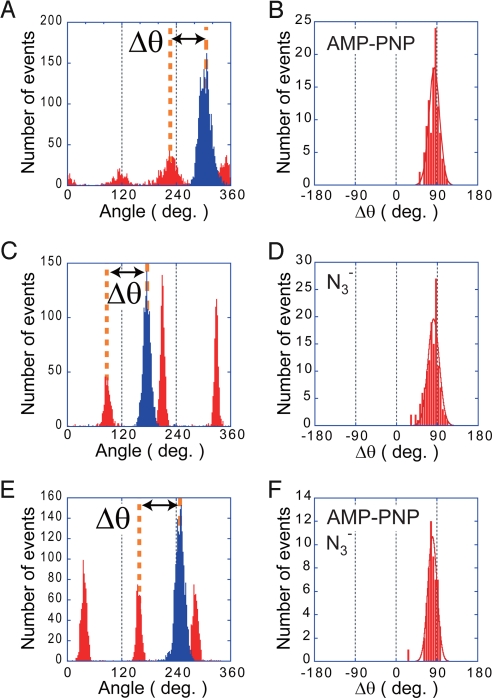

Pause Angle of F1αβγ Inhibited by AMP-PNP or N3−.

To crystallize F1, chemical inhibitors are often used to stabilize it in a specific conformational state. Another complementary method to correlate the crystal structure of F1 and the substeps found in the single-molecule rotation assay is to analyze the pausing angle of F1αβγ inhibited by these inhibitors in the rotation assay. AMP-PNP and N3− are the chemical inhibitors most often used for the crystallization of F1. Therefore, AMP-PNP and N3− were used to stop the rotation of F1αβγ in this experiment (Fig. 5). As in the cross-linking experiment, the 120° stepping rotation of a wild-type F1αβγ molecule was first observed under substrate-limiting conditions (60 nM ATP) to determine the 3 binding dwell angles. Then, the buffer containing an inhibitor (1 μM AMP-PNP or 1 mM NaN3) was introduced into the flow chamber with 60 nM ATP for the AMP-PNP inhibition or 200 μM ATP for N3− inhibition. When the motor exhibited a long pause (>3 min), it was verified that the pause was not caused by ADP inhibition by forcibly rotating the motor through +80° with the magnetic tweezers; when inhibited by AMP-PNP or N3−, F1αβγ was never activated by this manipulation. However, when AMP-PNP- or N3−-inhibited F1αβγ was forcibly rotated well over +80°, for example +180°, some molecules resumed rotation and stopped after a few turns. Such harsh manipulation would repel the tightly bound AMP-PNP- or N3−-ADP from F1αβγ. After determining the pause position of inhibited F1αβγ, the buffer was replaced with the inhibitor-free ATP buffer to confirm the molecule was still active by observing the resumption of ATP-driven rotation. Fig. 5A shows the pause position under AMP–PNP inhibition. The red bars represent the angle distribution during the 120° stepping rotation, and blue bars represent the angle distribution when inhibited by the inhibitor mixture. The angular distance (Δθ) of the AMP-PNP pause from the nearest binding angle on the clockwise side was determined (Fig. 5B) as in the above cross-link experiment. The mean angular distance was 84.2° ± 16.3°. This position corresponds to the catalytic dwell angle, consistent with the results of the cross-link experiment. The same result was obtained in the N3− inhibition experiments, and the mean angular distance of 81.9° ± 16.3° was obtained (Fig. 5 C and D). The pause angle of F1αβγ inhibited by 200 μM AMP-PNP, 5 μM ADP, and 1 mM NaN3, which mimics the crystallization buffer of the reference structure, was also examined. The mean angular distance was 80.2° ± 14.5° (Fig. 5 E and F), essentially the same as the above experiments. Thus, many lines of experiments confirmed that the crystal structure of F1 represents the catalytic dwell state found in the rotation assay.

Fig. 5.

Pausing position of F1αβγ stalled by chemical inhibitors. (A) Histogram of the angular position from a single experimental dataset of the AMP-PNP inhibition experiment. After observing active rotation of a molecule at 60 nM ATP, 1 μM AMP-PNP was infused into the reaction chamber with 60 nM ATP to stop the rotation. Red bars represent the angular position of free rotation; blue bars represent AMP-PNP inhibition. (B) Histogram of the angular deviation of the position of AMP-PNP inhibition from the binding dwell angle on the clockwise side (Δθ in A). The mean was 84.2 ± 16.3°. n = 107 (15 molecules). (C and D) The angular position of azide (N3−) inhibition. The rotation was inhibited by infusing 1 mM NaN3 with 200 μM ATP. The mean value of Δθ was 81.9 ± 16.3°. n = 129 (29 molecules). (E and F) The angular position when inhibited by 200 μM AMP-PNP, 5 μM ADP, and 1 mM NaN3. The mean value of Δθ was 80.2 ± 14.5°. n = 54 (9 molecules).

Discussion

The crystal structure of F1 was experimentally shown to represent the conformation of the catalytic dwell state found in single-molecule rotation assay. This means each β-subunit is in the βTP, βDP, or βempty conformations during the catalytic dwell state. The β-γ cross-link using a chimera F1αβγ carrying 1 copy of β(E190D/E391C) showed that the catalytic angle of β(E190D/E391C) coincides with the pause position of F1αβγ where βDP is cross-linked with γ. This finding means that the βDP corresponds to the conformational state of the β that executes ATP hydrolysis reaction, consistent with theoretical works on quantum mechanics and molecular mechanics (31) or free-energy difference simulations (32). The crystal structure of BeF3−-F1, which is thought to mimic the catalytic intermediate state, also supports this result (22).

Fig. 6 shows the present reaction scheme of F1, in which there are 2 chemical states during the catalytic dwell: prehydrolysis (state B) and posthydrolysis states (state C). Both states have the corresponding crystal structures. The recently reported structures (19, 33), the so-called “ground state” structures, in which both βTP and βDP bind with AMP-PNP correspond to the prehydrolysis state. However, the ADP·AlF3-bound structure (34) would represent the posthydrolysis state. The azide-bound structures (10, 18) would also correspond to this state. Considering that βDP represents the state that hydrolyzes ATP, βDP corresponds to the β before and after executing hydrolysis (the β at the right bottom in states B and C). Consequently, βTP conformation represents the ATP-bound state that was the ATP-waiting state in the prior binding dwell sate (state A in Fig. 6), and βempty corresponds to the state after ADP release.

Fig. 6.

The proposed reaction scheme of F1 and correlation with the crystal structure. State A represents the binding dwell state. After ATP binding and ADP release, F1 makes an 80° substep. Thereafter, F1 hydrolyzes the tightly bound ATP (denoted by *) in the state transition from B to C. These states correspond to the crystal structure of F1. After releasing Pi, F1 makes a 40° substep to complete a cycle of ATP hydrolysis reaction coupled with 120° rotation. State D is the next binding dwell state.

Thus, this study established the correlation between the conformational states of F1 found in the crystal structures and the single-molecule rotation assay. However, there is one uncertain point in the reaction scheme, the timing of Pi release. The present model assumes that βempty is the Pi-bound state, and after βempty releases Pi, the 40° substep is triggered (state C to state D). This assumption is based on the recent study of the crystal structure of yeast MF1 (33) in which Pi binds to βempty. The Pi-binding residues in the structure are consistent with those that biochemical studies have identified as the Pi binding site (35), supporting our reaction model. However, considering the other crystal structures that do not show an obvious electron density of Pi in the putative Pi-binding site, an alternative model is still possible; Pi is released from the βDP immediately after hydrolysis. A clarification of this issue is the next challenging task in the study of the mechanochemical-coupling mechanism of F1-ATPase.

Another issue is the structure of the binding dwell state. Although the ADP·AlF4−-bound MF1 shows obvious structural differences, the direction of the twist in the γ is opposite to our expectations. Therefore, ADP·AlF4−-bound MF1 is not in the binding dwell state. Rather, it might represent the intermediate state between state A and B of our reaction scheme in Fig. 6. Thus, there are no structural data about the binding dwell state. Because it is crucial for the understanding of the mechanochemical coupling mechanism of F1, a crystallographic study of F1 in the binding dwell state is one of the most important tasks for the understanding of the mechanism of F1-ATPase. However, the fact that the crystal structures identified so far are comparable with the reference structure implies that the crystallization of F1 in the binding dwell state is very difficult. One possible way is to crystallize F1 at low temperature (16) or F1 inhibited by tentoxin (36), where it spends most of the catalytic turnover time pausing at the binding dwell angle.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of F1αβγ.

Throughout this work, α3β3γ subcomplex of F1-ATPase from thermophilic Bacillus PS3 (TF1) was used. For inhibition by AMP-PNP or N3−, wild-type F1αβγ modified for the rotation assay α(His6 at N terminus/C193S)3β(His10 at N terminus)3γ(S108C/I211C) was used. For simplicity, this F1αβγ was referred to as wild-type F1αβγ or α3β3γ. For the β-γ cross-link experiment, cysteine residues were introduced into γR84 and/or βE391 of wild-type F1αβγ and α3β(E190D)3γ (14) to construct 4 mutants: α3β3γ(R84C), α3β(E190D)3γ(R84C), α3β(E391C)3γ(R84C), and α3β(E190D/E391C)3γ(R84C). Mutagenesis to construct the expression vectors of these mutants was performed as per the previous report on β-γ cross-linking (25). The mutants of F1αβγ were expressed in E. coli, purified, and biotinylated as reported (37). For the reconstitution of the chimera, α3β2β(E190D/E391C)γ(R84C), solutions of α3β3γ(R84C) and α3β(E190D/E391C)3γ(R84C) were mixed in a molar ratio of 2:1 and incubated for >2 days in the presence of 200 mM NaCl and 100 mM DTT at 4 °C and pH 7.0. The chimera α3β(E190D)2β(E391C)γ(R84C) was prepared by mixing solutions of α3β(E190D)3γ(R84C) and α3β(E391C)3γ(R84C) in a molar ratio of 2:1.

Rotation Assay.

The rotary motion of F1αβγ was visualized by attaching a magnetic bead (<0.2 μm; Seradyn) onto the γ-subunit of F1αβγ and immobilizing the α3β3 ring on a Ni-NTA-modified glass surface. Phase-contrast images of the rotating bead were obtained with an inverted optical microscope (IX-70; Olympus) equipped with magnetic tweezers (30). The image was captured with a CCD camera (FC300M; Takenaka) and recorded with a DV-CAM (DSR-11; Sony) at 30 fps. The recorded images were analyzed with image analysis software (Celery; Library) or a custom-made program (K. Adachi, Waseda University). The experimental procedures of the rotation assay for β-γ cross-linking were mostly the same as those reported (16), except for the content of the buffer. The basal buffer for the rotation assay contained 50 mM Hepes-KOH at pH 8.0, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM phospho(enol)pyrubate, 0.1 mg/ml pyrubate kinase, 5 mg/ml BSA, and 1 mM DTT. For β-γ cross-linking, 200 μM DTNB was added to the basal buffer, from which DTT and BSA were omitted. The rotation assay for AMP-PNP and/or NaN3 inhibition was carried out in the buffer containing 50 mM Mops-KOH at pH 7.0, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mg/ml BSA, and the indicated amount of nucleotides and NaN3.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank R. Hasegawa and Y. Iko-Tabata for technical assistance, W. Allison (University of California, San Diego) for plasmid vectors of mutant TF1αβγ from Bacillus PS3, M. Yoshida for discussion, and K. Adachi for the custom image analysis program. This work was partly supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 18074005 (to H.N.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0805828106/DCSupplemental.

The designation subunit name (mutation name) indicates the subunit with the indicated mutations. The designation without parentheses indicates a mutation.

References

- 1.Cross RL. The rotary binding change mechanism of ATP synthases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1458:270–275. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dimroth P, von Ballmoos C, Meier T. Catalytic and mechanical cycles in F-ATP synthases: Fourth in the Cycles Review Series. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:276–282. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Senior AE. ATP synthase: Motoring to the finish line. Cell. 2007;130:220–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida M, Muneyuki E, Hisabori T. ATP synthase: A marvelous rotary engine of the cell. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:669–677. doi: 10.1038/35089509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyer PD. The ATP synthase: A splendid molecular machine. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:717–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oster G, Wang H. Reverse engineering a protein: The mechanochemistry of ATP synthase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1458:482–510. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noji H, Yasuda R, Yoshida M, Kinosita K., Jr Direct observation of the rotation of F1-ATPase. Nature. 1997;386:299–302. doi: 10.1038/386299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diez M, et al. Proton-powered subunit rotation in single membrane-bound F0F1-ATP synthase. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:135–141. doi: 10.1038/nsmb718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsunoda SP, Aggeler R, Yoshida M, Capaldi RA. Rotation of the c-subunit oligomer in fully functional F1Fo ATP synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:898–902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031564198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrahams JP, Leslie AG, Lutter R, Walker JE. Structure at 2.8-Å resolution of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria. Nature. 1994;370:621–628. doi: 10.1038/370621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber J, Senior AE. Catalytic mechanism of F1-ATPase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1319:19–58. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(96)00121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menz RI, Walker JE, Leslie AG. Structure of bovine mitochondrial F(1)-ATPase with nucleotide bound to all three catalytic sites: Implications for the mechanism of rotary catalysis. Cell. 2001;106:331–341. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00452-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasuda R, Noji H, Yoshida M, Kinosita K, Jr, Itoh H. Resolution of distinct rotational substeps by submillisecond kinetic analysis of F1-ATPase. Nature. 2001;410:898–904. doi: 10.1038/35073513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimabukuro K, et al. Catalysis and rotation of F1 motor: Cleavage of ATP at the catalytic site occurs in 1 ms before 40 degree substep rotation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14731–14736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2434983100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adachi K, et al. Coupling of rotation and catalysis in F(1)-ATPase revealed by single-molecule imaging and manipulation. Cell. 2007;130:309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe R, Iino R, Shimabukuro K, Yoshida M, Noji H. Temperature-sensitive reaction intermediate of F1-ATPase. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:84–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yasuda R, et al. The ATP-waiting conformation of rotating F1-ATPase revealed by single-pair fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9314–9318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1637860100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowler MW, Montgomery MG, Leslie AG, Walker JE. How azide inhibits ATP hydrolysis by the F-ATPases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8646–8649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602915103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowler MW, Montgomery MG, Leslie AG, Walker JE. Ground-state structure of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria at 1.9-Å resolution. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14238–14242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700203200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirono-Hara Y, et al. Pause and rotation of F(1)-ATPase during catalysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13649–13654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241365698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao YQ, Yang W, Karplus M. A structure-based model for the synthesis and hydrolysis of ATP by F1-ATPase. Cell. 2005;123:195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kagawa R, Montgomery MG, Braig K, Leslie AG, Walker JE. The structure of bovine F1-ATPase inhibited by ADP and beryllium fluoride. EMBO J. 2004;23:2734–2744. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koga N, Takada S. Folding-based molecular simulations reveal mechanisms of the rotary motor F1-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5367–5372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509642103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun SX, Wang H, Oster G. Asymmetry in the F1-ATPase and its implications for the rotational cycle. Biophys J. 2004;86:1373–1384. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74208-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandyopadhyay S, Allison WS. The ionic track in the F1-ATPase from the thermophilic Bacillus PS3. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2533–2540. doi: 10.1021/bi036058i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibbons C, Montgomery MG, Leslie AG, Walker JE. The structure of the central stalk in bovine F(1)-ATPase at 2.4-Å resolution. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:1055–1061. doi: 10.1038/80981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma J, et al. A dynamic analysis of the rotation mechanism for conformational change in F(1)-ATPase. Structure (London) 2002;10:921–931. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00789-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodgers AJ, Wilce MC. Structure of the gamma-epsilon complex of ATP synthase. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:1051–1054. doi: 10.1038/80975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ariga T, Muneyuki E, Yoshida M. F1-ATPase rotates by an asymmetric, sequential mechanism using all three catalytic subunits. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:841–846. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirono-Hara Y, Ishizuka K, Kinosita K, Jr, Yoshida M, Noji H. Activation of pausing F1 motor by external force. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4288–4293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406486102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dittrich M, Hayashi S, Schulten K. ATP hydrolysis in the βTP and βDP catalytic sites of F1-ATPase. Biophys J. 2004;87:2954–2967. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.046128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang W, Gao YQ, Cui Q, Ma J, Karplus M. The missing link between thermodynamics and structure in F1-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:874–879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337432100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kabaleeswaran V, Puri N, Walker JE, Leslie AG, Mueller DM. Novel features of the rotary catalytic mechanism revealed in the structure of yeast F1 ATPase. EMBO J. 2006;25:5433–5442. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braig K, Menz RI, Montgomery MG, Leslie AG, Walker JE. Structure of bovine mitochondrial F(1)-ATPase inhibited by Mg2+ ADP and aluminium fluoride. Structure (London) 2000;8:567–573. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmad Z, Senior AE. Identification of phosphate binding residues of Escherichia coli ATP synthase. J Bionenerg Biomembr. 2005;37:437–440. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-9486-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meiss E, Konno H, Groth G, Hisabori T. Molecular processes of inhibition and stimulation of ATP synthase caused by the phytotoxin tentoxin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:24594–24599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802574200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rondelez Y, et al. Highly coupled ATP synthesis by F1-ATPase single molecules. Nature. 2005;433:773–777. doi: 10.1038/nature03277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.