Abstract

Objective To determine the relative benefits and risks of laparoscopic fundoplication surgery as an alternative to long term drug treatment for chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD).

Design Multicentre, pragmatic randomised trial (with parallel preference groups).

Setting 21 hospitals in the United Kingdom.

Participants 357 randomised participants (178 surgical, 179 medical) and 453 preference participants (261, 192); mean age 46; 66% men. All participants had documented evidence of GORD and symptoms for >12 months.

Intervention The type of laparoscopic fundoplication used was left to the discretion of the surgeon. Those allocated to medical treatment had their treatment reviewed and adjusted as necessary by a local gastroenterologist, and subsequent clinical management was at the discretion of the clinician responsible for care.

Main outcome measures The disease specific REFLUX quality of life score (primary outcome), SF-36, EQ-5D, and medication use, measured at time points equivalent to three and 12 months after surgery, and surgical complications.

Main results Randomised participants had received drugs for GORD for median of 32 months before trial entry. Baseline REFLUX scores were 63.6 (SD 24.1) and 66.8 (SD 24.5) in the surgical and medical randomised groups, respectively. Of those randomised to surgery, 111 (62%) actually had total or partial fundoplication. Surgical complications were uncommon with a conversion rate of 0.6% and no mortality. By 12 months, 38% (59/154) randomised to surgery (14% (14/104) among those who had fundoplication) were taking reflux medication versus 90% (147/164) randomised medical management. The REFLUX score favoured the randomised surgical group (14.0, 95% confidence interval 9.6 to 18.4; P<0.001). Differences of a third to half of 1 SD in other health status measures also favoured the randomised surgical group. Baseline scores in the preference for surgery group were the worst; by 12 months these were better than in the preference for medical treatment group.

Conclusion At least up to 12 months after surgery, laparoscopic fundoplication significantly increased measures of health status in patients with GORD.

Trial registration ISRCTN15517081.

Introduction

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) causes some of the most commonly seen symptoms in both primary and secondary care.1 Most have only mild symptoms and require little if any medication. A small minority have severe reflux and, despite full medical treatment, have complications or persistent symptoms requiring surgical intervention. For the remainder, control of symptoms requires regular or intermittent medical treatment, usually with proton pump inhibitors, and it is from this intermediate group that most of the treatment costs arise. While there is wide agreement that proton pump inhibitors, sometimes combined with prokinetic agents, are the most effective treatment for moderate to severe GORD, they can cause a spectrum of short term symptoms,2 and there are concerns about the impact of long term use through profound acid suppression.3

Interest in surgery as an alternative to long term medical treatment has been considerable since the introduction of the minimal access laparoscopic approach in the early 1990s. The operation (fundoplication) involves partial or total wrapping of the fundus of the stomach around the lower oesophagus to recreate a high pressure zone. Although fundoplication produces resolution of reflux symptoms in up to 90% of patients,4 we do not know whether exchanging symptoms associated with best medical management for those of the side effects of surgery is advantageous for the patient and a good use of healthcare resources.

We carried out a multicentre pragmatic randomised trial (with parallel non-randomised preference groups to contextualise the results and augment them, particularly in respect of surgical complications),5 evaluating the clinical effectiveness, safety, and costs of a policy of relatively early laparoscopic surgery compared with optimised medical management of GORD for people judged suitable for both policies.

Methods

Participants

Patients were eligible if they had more than 12 months’ symptoms requiring maintenance treatment with a proton pump inhibitor (or alternative) for reasonable control; they had endoscopic or 24 hour pH monitoring evidence of GORD, or both; they were suitable for either policy (including American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade I or II); and the recruiting doctor was uncertain which management policy to follow. Exclusion criteria were morbid obesity (BMI >40); Barrett’s oesophagus of more than 3 cm or with evidence of dysplasia; para-oesophageal hernia; and oesophageal stricture.

We invited any eligible patient who did not want to take part in the randomised trial because of a strong preference about treatment to join a non-randomised preference arm. An independent data monitoring committee recommended continued recruitment on each of the three occasions that it confidentially reviewed accumulating data.

Clinical management

Clinical management aimed to optimise current care in participating centres. Participating clinical centres had local partnerships between surgeons (who had performed at least 50 laparoscopic fundoplication operations) and gastroenterologists with whom they shared the secondary care of patients with GORD. They, supported by local research nurses, informed participants about the randomised trial and invited them to take part. It was only at this point that participants who declined to take part in the randomised trial, because of a strong preference either for remaining on medical treatment or for undergoing surgery, were informed about, and given the opportunity to take part in, the preference study.

For all participants in either the randomised or preference surgical group, surgery could be subsequently deferred or declined, by either the participant or surgeon (that is, even after trial entry). In the absence of erosive oesophagitis on endoscopy, and when necessary to exclude achalasia, manometry or pH studies were performed before surgery. A lead surgeon (or a less experienced surgeon working under supervision) undertook the surgery. Routine crural repair and non-absorbable synthetic sutures were recommended. The type of fundoplication was left to the discretion of the surgeon, who recorded intraoperative details on a specially designed study form. For the purposes of the main comparisons, we considered the different fundoplication techniques as a single policy. Those allocated to medical treatment had their treatment reviewed and adjusted as necessary by a local gastroenterologist to be “best medical management,” based on the Genval workshop report.6 The medical protocol included the option of surgery if a clear indication developed after randomisation. In all other respects, clinical management was at the discretion of the clinician responsible for care.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures were those judged important to patients and health services. The primary outcome was the REFLUX questionnaire score, a validated “disease specific” measure incorporating assessment of reflux and other gastrointestinal symptoms and the side effects and complications of both treatments (score range 0 to 100, the higher the score the better the patients felt).7 The score was derived from the weighted average of six questions on quality of life (heartburn; acid reflux; eating and swallowing; bowel movements; sleep; and work, physical, and social activities). Five symptom scores were also developed as secondary measures (general discomfort; wind and frequency; nausea and vomiting; limitation in activity; constipation and swallowing). Participants were followed up by postal questionnaire three and 12 months after surgery or at an equivalent time among those who did not have surgery; the medical participants were linked to surgical participants who had been randomised at about the same time. Issues related to long, variable length, waiting lists prohibited timing of follow-up from randomisation. Other prestated outcome measures were health status (EQ-5D, based on UK public preference values, and SF-36); serious morbidity, such as operative complications; and mortality.

Sample size

We originally intended to recruit 300 participants to each trial group to identify a difference between the randomised groups of 0.25 of 1 SD in the disease specific REFLUX score (80% power; α=0.05) 12 months after surgery. In January 2003, however, in part prompted by a lower rate of recruitment than expected, we revised this target in consultation with the data monitoring committee and representatives of the funders. It was agreed that a slightly larger but still moderate sized benefit (0.3 of 1 SD, equivalent to seven points on the REFLUX quality of life score) was clinically plausible based on improvements reported in other studies8 9 after surgery among more severely affected people. We calculated that this required 196 in each group to give 80% power (α=0.05), assuming 10% attrition (that is, 176 per group with 12 month follow-up).

Randomisation

Random allocation was organised centrally by a secure system, using a computer generated sequence, stratified by clinical site, with balance in respect of age (18-49 or ≥50), sex (men or women), and BMI (≤28 or >29) secured by minimisation. Staff in the central trial office entered details of participants on the secure database, then notified participants and respective clinical sites of their allocation. There was no subsequent blinding.

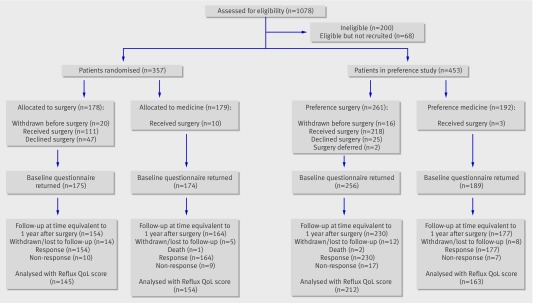

The figure summarises the stages of the trial. The first 146 randomised participants (70 allocated to surgery and 76 allocated to medical management) were sent details of their allocation at the same time as the baseline questionnaires. This was changed at the request of the data monitoring committee such that subsequent allocations were generated only once completed baseline forms had been returned. The committee were concerned that if patients were to receive their allocation before completing the questionnaire this could potentially affect their responses.

Flow of participants through trial

Statistical methods

Our primary analysis in the randomised trial was by intention to treat. General linear models adjusted for the minimisation covariates (age, BMI, and sex) and, when appropriate, for baseline score and interaction between baseline score and treatment. We also included a covariate to adjust for the change in practice regarding the baseline questionnaires. All analyses used 95% confidence intervals. Because a relatively large proportion of the randomised surgical participants did not receive surgery, we also performed per protocol analyses and analyses adjusted for treatment received10 11 to estimate efficacy of treatment. For the preference groups, we analysed statistically only the primary outcome, the REFLUX score. This analysis compared the group who preferred surgery with the group who preferred medical treatment and adjusted for the minimisation factors. We did not plan to adjust for the baseline score using analysis of covariance methods in the analysis of the preference groups given the anticipated non-random imbalances at baseline.

Results

Recruitment took place in 21 centres in the United Kingdom from March 2001 to June 2004: 357 participants were in the randomised arm (178 allocated to surgery and 179 to medical management) and 453 in the preference arm (261 chose surgery and 192 chose medical management) (figure). The three and 12 month follow-ups were conducted an average of 86 and 360 days after surgery, respectively, and this was equivalent to 300 and 570 days (580 and 540 days in the randomised surgical and medical groups, respectively) after randomisation across all the trial groups; three and 12 month follow-up questionnaires were received from 86% and 89% participants, respectively. Three participants died, two in the preference for surgery group and one in the randomised medical group; none had surgery. All deaths were unrelated to trial participation.

Description of the groups at trial entry

The characteristics of the randomised participants (table 1, baseline rates for medication in table 2, and table A on bmj.com) were similar and lay between those in the preference groups; participants in the preference for surgery group were younger and had been prescribed medication for GORD for longer; participants in the preference for medical treatment group were older, more likely to be women, and had been prescribed medication for a shorter time.

Table 1.

Description of groups at trial entry. Figures are number (percentage*) unless stated otherwise

| Randomised participants | Preference participants | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical | Medical | Surgical | Medical | ||||||||

| ITT (n=178) | PP (n=111) | ITT (n=179) | PP (n=169) | ITT (n=261) | PP (n=218) | ITT (n=192) | PP (n=189) | ||||

| Baseline questionnaire returned | 175 (98) | 111 (100) | 174 (97) | 165 (98) | 256 (98) | 216 (99) | 189 (98) | 186 (98) | |||

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 46.7 (10.3) | 46.3 (10.2) | 45.9 (11.9) | 45.9 (11.9) | 44.4 (12.0) | 44.5 (12.2) | 49.9 (11.8) | 50 (11.7) | |||

| Men | 116 (65) | 68 (61) | 120 (67) | 115 (68) | 170 (65) | 139 (64) | 111 (58) | 110 (58) | |||

| Mean (SD) BMI | 28.5 (4.3) | 28.7 (4.1) | 28.4 (4.0) | 28.3 (4.0) | 27.7 (4.0) | 27.5 (3.7) | 27.4 (4.1) | 27.4 (4.1) | |||

| Median duration (months) of prescribed medication for GORD (IQR) | 33 (15-83) | 30 (16-76) | 31 (16-71) | 30 (15-71) | 35 (14-71) | 36 (14-65) | 27 (13-60) | 26.5 (13-60) | |||

| In full time paid employment | 116 (66) | 72 (66) | 110 (62) | 104 (62) | 168 (65) | 138 (64) | 100 (52) | 97 (52) | |||

| Current smoker | 46 (26) | 29 (26) | 40 (22) | 36 (21) | 71 (27) | 61 (28) | 39 (20) | 39 (21) | |||

ITT=intention to treat; PP=per protocol; BMI=body mass index; IQR=interquartile range.

*Calculated excluding missing data from returned forms.

Table 2.

Use of antireflux medication in previous two weeks. Figures are number (percentage*) unless stated otherwise

| Randomised participants | Preference participants | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical | Medical | Surgical | Medical | ||||||||

| ITT (n=178) | PP (n=111) | ITT (n=179) | PP (n=169) | ITT (n=261) | PP (n=218) | ITT (n=192) | PP (n=189) | ||||

| Taking any drug related to reflux | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 170 (97) | 108 (97) | 169 (97) | 160 (97) | 235 (92) | 198 (92) | 184 (97) | 181 (9) | |||

| 3 months after surgery | 50 (33) | 10 (9) | 146 (92) | 139 (93) | 45 (20) | 17 (8) | 176 (97) | 161 (90) | |||

| 12 months after surgery | 59 (38) | 15 (14) | 147 (90) | 144 (93) | 46 (20) | 22 (11) | 165 (93) | 163 (94) | |||

| Taking any proton pump inhibitors | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 161 (92) | 105 (95) | 162 (93) | 153 (93) | 225 (88) | 191 (88) | 173 (92) | 170 (91) | |||

| 3 months after surgery | 47 (31) | 8 (7) | 140 (89) | 133 (89) | 41 (18) | 13 (6) | 167 (92) | 152 (85) | |||

| 12 months after surgery | 56 (36) | 13 (13) | 142 (87) | 139 (90) | 42 (18) | 19 (9) | 156 (88) | 154 (89) | |||

ITT=intention to treat; PP=per protocol.

*Calculated excluding missing data from returned forms.

Surgical management

In total, 111 (62%) of those randomised to surgery and 218 (84%) participants in the preference for surgery group actually received fundoplication (table 3). The most common clinical reasons for not having surgery were a surgeon’s decision that symptoms were not sufficiently severe or that a patient was not fit for surgery (such as being overweight). The most common personal reasons were participants’ change of mind for work or home related reasons, concerns about surgery, a wish to avoid preoperative tests, and improved symptoms.

Table 3.

Details of surgery for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Figures are number (percentage) unless stated otherwise

| Surgical participants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Randomised (n=178) | Preference (n=261) | |

| Received surgery | 111 (62) | 218 (84) |

| Declined surgery for clinical reasons | 25 (14) | 13 (5) |

| Declined surgery for personal reasons | 22 (12) | 11 (4) |

| Other/withdrawn/lost to follow-up before surgery | 20 (11) | 19 (7) |

| Management of those who actually had surgery | ||

| Type of fundoplication*: | ||

| Total wrap | 52 (47) | 158 (73) |

| Partial-anterior | 51 (46) | 35 (16) |

| Partial-posterior | 8 (7) | 24 (11) |

| Grade of operating surgeon†: | ||

| Consultant | 100 (92) | 174 (81) |

| Other | 9 (8) | 42 (19) |

| Mean (SD) operation time (mins) | 113 (38) | 123 (64) |

| Conversion | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Visceral injury | 2 (2) | 6 (3) |

| Reoperation within 12 months | 0 (0) | 3 (1) |

| Stricture dilatation or food disimpaction required within 12 months | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Median (IQR) length of stay (days) | 2 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) |

IQR=interquartile range.

* Data missing for one patient in preference group.

†Data missing for two patients in randomised group and two in preference group.

Table 3 shows details of the surgery. Two (1%) of the 329 participants who had surgery had conversions to an open procedure (95% confidence interval 0.2% to 2.2%), and eight (2%) had a visceral injury (1.2% to 4.7%). Most of those who had fundoplication were discharged home within two days. Three (1%) required reoperation (0.3% to 2.6%)—all in the preference group—and three had dilatation of an oesophageal stricture or for food disimpaction within 12 months of their initial surgery.

Antireflux medication

Table 2 also shows actual use of antireflux medication during the previous two weeks at baseline, first follow-up, and second follow-up. By 12 months after surgery, 38% (59/154) of the randomised surgical participants were taking medication compared with 90% (147/164) of the randomised medical participants (nearly all of whom were taking proton pump inhibitors). Among those who had surgery, use of antireflux medication dropped to 9% at three months and 14% (14/104) at 12 months after surgery. Improvements in the scores in the medical group might reflect changes in management; lansoprazole was the predominant proton pump inhibitor used at study entry, whereas at follow-up omeprazole and lansoprazole were the most commonly reported.

Health status

Table 4 shows REFLUX scores at baseline and at three and 12 months (see also tables B and C on bmj.com). There were substantial differences between the randomised intention to treat groups in the REFLUX score (a third to a half of 1 SD at follow up), with the surgery group having better scores than the medical group. This reflected improvements across all symptom domains within the measure (see tables B, C, and D on bmj.com). The differences between groups were larger when we considered only the per protocol participants.

Table 4.

Health status at baseline and at three and 12 months after surgery. Figures are means (SD)

| Randomised participants | Preference participants | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical | Medical | Surgical | Medical | ||||||||

| Randomised (n=178) | Per protocol (n=111) | Randomised (n=179) | Per protocol (n=169) | Preference (n=261) | Per protocol (n=218) | Preference (n=192) | Per protocol (n=189) | ||||

| Primary outcome (REFLUX QoL) | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 63.6 (24.1) | 61.9 (24.5) | 66.8 (24.5) | 68.2 (24.2) | 55.8 (23.2) | 55.9 (23.2) | 77.5 (19.7) | 78.0 (19.1) | |||

| 3 months | 83.9 (19.4) | 85.9 (19.0) | 70.6 (24.6) | 70.8 (24.4) | 80.4 (21.6) | 82.5 (20.3) | 80.2 (18.2) | 80.6 (17.7) | |||

| 12 months | 84.6 (17.9) | 88.3 (15.6) | 73.4 (23.3) | 73.1 (23.7) | 83.3 (20.7) | 86.0 (17.9) | 79.2 (19.2) | 79.4 (19.0) | |||

| Secondary outcome (EQ-5D index) | |||||||||||

| Baseline | 0.71 (0.26) | 0.72 (0.24) | 0.72 (0.25) | 0.73 (0.25) | 0.68 (0.26) | 0.68 (0.26) | 0.75 (0.22) | 0.75 (0.22) | |||

| 3 months | 0.79 (0.23) | 0.81 (0.24) | 0.69 (0.30) | 0.70 (0.30) | 0.81 (0.25) | 0.82 (0.24) | 0.76 (0.23) | 0.77 (0.23) | |||

| 12 months | 0.75 (0.25) | 0.78 (0.23) | 0.71 (0.27) | 0.71 (0.27) | 0.79 (0.26) | 0.80 (0.25) | 0.74 (0.24) | 0.74 (0.24) | |||

Statistical analyses for the primary outcome (REFLUX score 12 months after surgery) showed strong evidence of increases in scores favouring surgery (table 5). Both the per protocol analyses and analyses adjusted for treatment received (providing estimates of treatment efficacy) suggested larger differences between the randomised groups. For the intention to treat analysis, the mean difference in favour of surgery was 11.2 between the groups with adjustment for only the minimisation variables (model I) and this increased to 14.1 when we included the baseline score (model II). There was strong evidence of an interaction effect between randomised group and baseline REFLUX score (interaction term: −0.35, −0.53 to −0.17; P<0.001). This implied that as baseline REFLUX score decreased (baseline symptoms were more severe) the treatment effect of surgery increased. For example, estimating the treatment difference at baseline mean REFLUX score of 65.4 resulted in a trial effect size of 14.0 (9.6 to 18.4; P<0.001; model III, the most parsimonious model). If the average patient had a lower mean REFLUX score at baseline of 56.0, the effect size increased to 17.2 (12.6 to 21.9). If the patient had a higher baseline score of 78.0, the treatment effect decreased to 9.5 (4.5 to 14.5).

Table 5.

Difference* (95% confidence interval) in REFLUX quality of life score† at 12 months after surgery in randomised participants

| Model | Intention to treat | Per protocol | Adjusted for treatment received |

|---|---|---|---|

| I: adjusted for minimisation variables | 11.2 (6.4 to 16.0) | 15.4 (10.0 to 20.9) | 16.7 (9.7 to 23.6) |

| II: adjusted for minimisation variables and baseline REFLUX QoL score | 14.1 (9.6 to18.6) | 19.1 (14.0 to 24.1) | 20.3 (13.8 to 26.8) |

| III: adjusted for minimisation variables, baseline score, and interaction between treatment and baseline REFLUX QoL score | 14.0 (9.6 to18.4) | 18.4 (13.6 to 23.2) | 19.4 (13.0 to 25.8) |

*Surgery group minus medical group, all P<0.001.

†Higher scores mean patient felt better (range 0-100).

Similar patterns in the randomised groups were seen in the SF-36 scores, where the biggest differences favouring surgery were observed in the general health and bodily pain dimensions and in the EQ-5D score (see tables B, C, and D on bmj.com), although with some evidence of attenuation at 12 months. Three participants died, one in the randomised medical group (road traffic incident) and two in the preference surgical group, neither of whom had surgery (alcoholic liver disease and cause unknown).

Possible side effects of surgery

No differences were detected between the trial groups in their questionnaire responses at 12 months regarding “difficulty swallowing” and “bloatedness/trapped wind,” but there was some evidence of more frequent “wind from the lower bowel” after surgery.

Preference groups

The participants in the preference for surgery group had lower mean REFLUX scores at baseline than those in the preference for medical treatment group (55.8 v 77.5). Despite this, at follow-up at 12 months, according to intention to treat analysis (difference 3.9, −0.2 to 8.0; P=0.064) and per protocol analysis (6.3, 2.4 to 10.2; P=0.002) the REFLUX score favoured the preference surgical group.

For participants in the preference group, other quality of life scores also tended to favour the surgical group. The differences between the preference groups, however, were less marked than the differences between the randomised groups, mainly because the preference for medical treatment group had better scores than the randomised medical group at baseline and follow-up.

Discussion

Principal findings

In patients with GORD, laparoscopic fundoplication results in better symptom relief and improved quality of life compared with optimised medical treatment. There were highly significant differences between the randomised groups in the REFLUX scores three months after surgery (a half to a third of 1 SD) favouring surgery, and these were broadly sustained nine months later. The lower the REFLUX scores at entry—that is, the worse the symptoms—the larger were the improvements after surgery. Similar differences were seen in most of the other measures of health status. There was, however, some evidence of a narrowing of the differences between three and 12 months, particularly for the EQ-5D. Data on drug treatment were consistent with this, showing more use in the surgical groups at 12 months than at three months. There were small improvements in scores in the medical groups; this might reflect their having specialist review at trial entry to optimise their drug treatment.

Those who agreed to join the randomised trial had baseline characteristics between the two preference groups. The results in the preference groups were consistent with the randomised comparison: scores after surgery in those who preferred surgery were somewhat higher than in those who preferred medical treatment, despite starting from much lower baseline levels. None of the three participants who died had surgery and complications were uncommon; but confidence intervals around estimated frequencies were wide despite inclusion of all 319 surgical participants, leaving important uncertainty about the magnitude of surgical risk.

Strengths and weaknesses

We used a pragmatic trial design, with many UK patients, centres and experienced surgeons, thus allowing the results to be interpreted within a “real life” NHS context. The addition of the preference groups gives an indication of probable behaviour if surgery were to become more freely available.

We explored the impact of a third of those randomised to surgery not having fundoplication: firstly, through per protocol analyses limited to those randomised who received their allocated management, and, secondly, through an adjusted approach10 11 in an attempt to circumvent the probable selection bias of per protocol analyses. In the event, these two approaches gave similar results. The direction of effects was so clear that we observed significant differences even in the most conservative intention to treat analyses. While the intention to treat analyses estimate unbiased average effects on compliers and non-compliers, the adjusted analyses estimate bias adjusted average treatment effects on those who comply with treatment. In general, an adjusted analysis is preferable to a per protocol analysis as it is less likely to be biased.

The protocol allowed surgeons to use the type of fundoplication with which they were familiar, principally to avoid any learning effects. There is mixed evidence for the use of a total wrap or partial wrap.12 We explored possible differential effects of total versus partial wrap fundoplication in an observational analysis and found no evidence of a difference within either the randomised, preference, or per protocol groups (difference in 12 month REFLUX score −1.3 (−7.9 to 5.2), P=0.687).

Our study was limited to patients who were on long term acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors, who had symptoms that were reasonably controlled, and who were clinically suitable for either policy; it is to these sorts of patients with GORD that the results are generalisable. Potential participants were not easy to identify and recruit, and this led to slow recruitment. Most patients taking long term proton pump inhibitor treatment are managed in general practice, often through a repeat prescription system, whereas our trial was based in secondary care. We used three approaches to identify potentially eligible patients: retrospective review of hospital case notes; prospective identification, especially through endoscopy clinics; and (in selected centres) public advertisements. All potentially eligible patients then had to be assessed clinically, often through specially established monthly clinics, before being formally approached about the trial. Those approached often expressed clear preferences, reflecting the marked differences between the policies being compared.

The trial was conducted at a time when there was great pressure on surgical services in the NHS, with long delays for elective surgery for non-life threatening benign conditions. Indeed, the average time between trial entry and surgery was eight to nine months. Some participants experienced long delays before being formally offered surgery, and this was an important factor in their eventual decision to choose not to have surgery after all. While patient’s choice was the commonest reason for not having surgery, about a third of those who did not have fundoplication after allocation to surgery were refused surgery for clinical reasons: most commonly, the surgeon disagreed with the recruiting doctor that symptoms were sufficient to justify surgery or judged that the patient was not sufficiently fit (such as overweight) or the symptoms had improved since randomisation,

The standard rule in most trials is to time follow-up from randomisation. This was not appropriate in our trial because of the variable time between randomisation and surgery, exacerbated by the waiting list problem. The protocol specified follow-up at a time equivalent to three and 12 months after surgery. It was important to have follow-up in the medical groups at an equivalent time. We arranged this by setting the follow-up of medical participants at time points equivalent to three months and 12 months after surgery.

We focused directly on subjective measures of outcome (patient reported measures) rather than on objective measures of outcome. This was intentional and appropriate for the pragmatic evaluation of the interventions. In clinical practice, pH is not routinely measured after surgery. If we had included such objective outcome measures, this would have entailed our changing the regular management practices for these patients, thus jeopardising the generalisability of both our intervention and our findings.

Comparison with other studies

We identified two other randomised trials comparing laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with continued medical management.13 14 They were less pragmatic in design with fewer participants (21713 and 10414), centres (two13 and one14), and surgeons (two13 and four14) and reported postoperative 24 hour pH measurement. The results of the two trials were consistent with ours. Across all trials, there were significantly greater improvements after surgery in measures of gastrointestinal and general wellbeing. While no major intraoperative complications were reported among the 52 patients who had surgery in one trial,14 in the other trial there were four major complications and four reoperations, including one case of gastric resection, among the 109 patients who had fundoplication,13 illustrating the potential risks of the procedure.

Conclusions

Laparoscopic fundoplication significantly increased health status at least to 12 months after surgery. Surgery does carry costs, however, and we will report investigation of cost effectiveness elsewhere. The narrowing of differences in health status between three and 12 months could reflect a postoperative placebo effect or could indicate decreasing effectiveness of surgery over time from surgery (as has been observed after open fundoplication9). We have therefore instituted annual follow-up using similar questionnaires and plan to report long term effectiveness after five years of follow-up.

What is already known on this topic

Many people require regular proton pump inhibitors to control symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, and there are concerns regarding the impact of long term use

Laparoscopic fundoplication can relieve symptoms of reflux, but side effects of surgery might be worse than symptoms associated with the best medical management

What this study adds

At one year follow-up reflux specific symptoms and general quality of life were better in patients who underwent laparoscopic fundoplication compared with those receiving optimised medical treatment

We thank Maureen G C Gillan, Marie Cameron, and Christiane Pflanz-Sinclair for their assistance in study coordination, recruitment of participants, and follow-up; Sharon McCann, who was involved in piloting the practical arrangements of this trial; Allan Walker for database and programming support; and Janice Cruden and Pauline Garden for their secretarial support and data management.

Trial coordination team

Garry Barton (1999-2002), Laura Bojke, Marion Campbell, David Epstein, Adrian Grant, Sue Macran, Craig Ramsay, Mark Sculpher, Samantha Wileman.

Trial steering group

Wendy Atkin (chair, independent of trial), John Bancewicz, Ara Darzi, Robert Heading, Janusz Jankowski (independent of trial), Zygmunt Krukowski, Richard Lilford (independent of trial), Iain Martin (1997-2000), Ashley Mowat, Ian Russell, Mark Thursz.

Data monitoring committee

Jon Nicholl, Chris Hawkey, Iain MacIntyre (all independent of trial)

Members of the REFLUX trial group responsible for recruitment in the clinical centres

A Mowat, Z Krukowski, E El-Omar, P Phull, T Sinclair, L Swan (Aberdeen Royal Infirmary); B Clements, J Collins, A Kennedy, H Lawther (Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast); D Bennett, N Davies, S Toop, P Winwood (Royal Bournemouth Hospital); D Alderson, P Barham, K Green, R Mittal (Bristol Royal Infirmary); M Asante, S El Hasani (Princess Royal University Hospital, Bromley); A De Beaux, R Heading, L Meekison, S Paterson-Brown, H Barkell (Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh); G Ferns, M Bailey, N Karanjia, TA Rockall, L Skelly (Royal Surrey County Hospital, Guildford); M Dakkak, C Royston, P Sedman (Hull Royal Infirmary); K Gordon, L F Potts, C Smith, PL Zentler-Munro, A Munro (Raigmore Hospital, Inverness); S Dexter, P Moayeddi (General Infirmary at Leeds); DM Lloyd (Leicester Royal Infirmary); V Loh, M Thursz, A Darzi (St Mary’s Hospital, London); A Ahmed, R Greaves, A Sawyerr, J Wellwood, T Taylor (Whipps Cross Hospital, London); S Hosking, S Lowrey, J Snook (Poole Hospital); P Goggin, T Johns, A Quine, S Somers, S Toh (Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth); J Bancewicz, M Greenhalgh, W Rees (Hope Hospital, Salford); CVN Cheruvu, M Deakin, S Evans, J Green, F Leslie (North Staffordshire Hospital, Stoke-on-Trent); J N Baxter, P Duane, M M Rahman, M Thomas, J Williams (Morriston Hospital, Swansea); D Maxton, A Sigurdsson, M S H Smith, G Townson (Princess Royal Hospital, Telford); C Buckley, S Gore, RH Kennedy, Z H Khan, J Knight (Yeovil District Hospital); D Alexander, G Miller, D Parker, A Turnbull, J Turvill (York District Hospital).

Contributors: AMG was the principal grant holder and contributed to development of the trial protocol and preparation of the paper and had overall responsibility for the conduct of the trial. SMW contributed to development of the trial design, was responsible for the day to day management of the trial, monitored data collection and assisted in the preparation of the paper. CRR contributed to the grant application and trial design and conducted the statistical analysis. ZHK, NAM, RCH, and MRT advised on clinical aspects of the trial design and the conduct of the trial and commented on the draft paper. MKC contributed to the development of the trial design, commented on all aspects of the conduct of the trial, and contributed to the preparation of the paper. AMG is guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme (as part of project No 97/10/99), and the full project report is published in Health Technology Assessment 2008;12:1-181. The Health Services Research Unit is funded by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorates. The funders of this study (NCCHTA), other than the initial peer review process before funding and six monthly progress reviews, did not have any involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Health or the funders that provide institutional support for the authors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Scottish multicentre research ethics committee and the appropriate local research ethics committees. All participants gave informed consent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Cite this as: BMJ 2008;337:a2664

References

- 1.Kay L, Jorgensen T, Hougaard Jensen K. Epidemiology of abdominal symptoms in a random population: prevalence, incidence, and natural history. Eur J Epidemiol 1994;10:559-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leufkens H, Claessens A, Heerdink E, Van Eijk J, Lamers CBHW. A prospective follow-up study of 5669 users of lansoprazole in daily practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1997;11:887-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laine L, Ahnen D, McClain C, Solcia E, Walsh JH. Potential gastrointestinal effects of long-term acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000;14:651-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zacharoulis D, O’Boyle CJ, Sedman PC, Brough WA, Royston CMS. Laparoscopic fundoplication: a 10-year learning curve. Surg Endosc 2006;20:1662-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torgerson D, Sibbald B. Understanding controlled trials: What is a patient preference trial? BMJ 1998;316:360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dent J, Jones R, Kahrilas PJ, Talley NJ. Management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in general practice. BMJ 2001;322:344-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macran S, Wileman S, Barton G, Russell I. The development of a new measure of quality of life in the management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: the Reflux questionnaire. Qual Life Res 2007;16:331-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross S, Jabbar A, Ramsay CR, Watson AJM, Grant AM, Krukowski ZH. Symptomatic outcome following laparoscopic anterior partial fundoplication: follow-up of a series of 200 patients. J R Coll Surg Edinb 2000;45:363-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spechler JS, Lee E, Ahnen D, Goyal RK, Hirano I, Ramirez F, et al. Long-term outcome of medical and surgical therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease: follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;285:2331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagelkerke N, Fidler V, Bersen R, Borgdorff M. Estimating treatment effects in randomised clinical trials in the presence of non-compliance. Stat Med 2000;19:1849-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White IR. Uses and limitations of randomization-based efficacy estimators. Stat Methods Med Res 2005;14:327-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neufeld M, Graham A. Levels of evidence for techniques in antireflux surgery. Dis Esophagus 2007;20:161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahon D, Rhodes M, Decadt B, Hindmarsh A, Lowndes R, Beckingham I, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication compared with proton-pump inhibitors for treatment of chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux. Br J Surg 2005;92:695-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anvari M, Allen C, Marshall J, Armstrong D, Goeree R, Ungar W, et al. A randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitors for treatment of patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease: one-year follow-up. Surg Innov 2006;13:238-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]