Abstract

The antibiotics fosmidomycin and FR900098 are members of a unique class of phosphonic acid natural products that inhibit the nonmevalonate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis. Both are potent anti-bacterial and anti-malarial compounds, but despite their efficacy, little is known regarding their biosynthesis. Here we report the identification of the Streptomyces rubellomurinus genes required for the biosynthesis of FR900098. Expression of these genes in Streptomyces lividans results in production of FR900098, demonstrating their role in synthesis of the antibiotic. Analysis of the putative gene products suggests that FR900098 is synthesized by metabolic reactions analogous to portions of the tricarboxylic acid cycle. These data greatly expand our knowledge of phosphonate biosynthesis and enable efforts to overproduce this highly useful therapeutic agent.

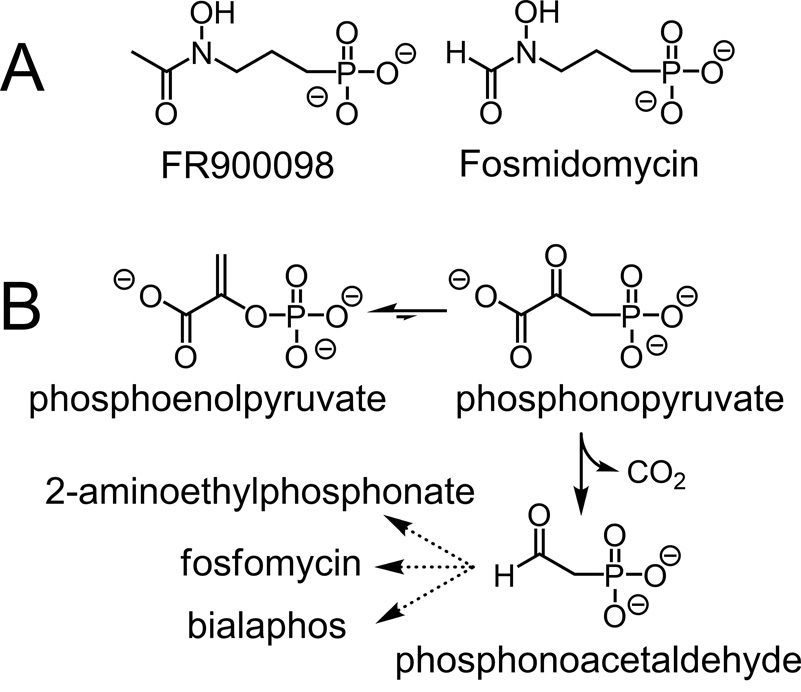

Afflicting an estimated 500 million people and causing over one million deaths per year, malaria exacts a terrible toll in tropical and subtropical regions(Snow et al., 2005). Although a number of antimalarial treatments exist, resistance is increasingly common, creating an urgent need for new drugs(Schlitzer, 2007). Among the most promising of such new antimalarial therapies are the phosphonic acid antibiotics FR900098 and fosmidomycin (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) The structures of the antimalarial compounds FR900098 and fosmidomycin. Both inhibit DXR, an essential enzyme in the isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway in malaria-causing parasites. (B) The initial reactions in the biosynthesis of 2-aminoethylphosphonic acid, fosfomycin, and bialaphos. In the first step, catalyzed by PEP mutase, phosphoenolpyruvate is rearranged to phosphonopyruvate, which is then decarboxylated to yield phosphonoacetaldehyde in a reaction catalyzed by phosphonopyruvate decarboxylase.

These two compounds were originally identified as antibiotics produced by Streptomyces rubellomurinus and Streptomyces lavendulae, respectively(Okuhara et al., 1980). Subsequent studies showed that both act as potent inhibitors of 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR), the first enzyme in the nonmevalonate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis(Kuzuyama et al., 1998; Rohmer, 1999). The identification of this pathway in the malaria-causing parasite Plasmodium falciparum renewed interest in these phosphonate antibiotics as potential anti-malarial drugs(Jomaa et al., 1999). Both FR900098 and fosmidomycin are effective against P. falciparum in vitro and against the closely related P. vinckei in mice(Jomaa et al., 1999). Importantly, these drugs are active even against multidrug-resistant strains of P. falciparum(Jomaa et al., 1999).

Given the importance of this new class of antimalarial compounds, we aimed to identify the FR900098 biosynthetic genes from S. rubellomurinus. To date, complete biosynthetic gene clusters have been identified for only three phosphonate compounds: aminoethylphosphonate(Barry et al., 1988), fosfomycin(Hidaka et al., 1995), and bialaphos(Blodgett et al., 2005; Schwartz et al., 2004). These and other studies led to the proposal that the initial step in all phosphonate biosyntheses is the rearrangement of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) to form phosphonopyruvate, catalyzed by the enzyme PEP mutase(Seidel et al., 1988) (Fig. 1B). Consistent with this idea, PEP mutase activity was detected in cell free extracts of S. rubellomurinus(Hidaka et al., 1989). We therefore developed a PEP mutase gene-targeted approach to identify the FR900098 biosynthetic genes, which is reported here along with heterologous expression and production of the antibiotic in S. lividans. These results provide significant new insight into the biosynthesis of phosphonic acid antibiotics and make possible efforts to enhance bioproduction of this important antimalarial compound.

Results and Discussion

A PCR based strategy was used to clone the FR900098 biosynthetic gene cluster. Based on the precedent of other phosphonate biosyntheses, we assumed that the initial step in FR900098 biosynthesis is the PEP mutase-catalyzed rearrangement to form phosphonopyruvate. Using degenerate primers designed to anneal to conserved sequences within known PEP mutase genes(Blodgett et al., 2005), we were able to amplify a 406 bp fragment from S. rubellomurinus genomic DNA which encodes a peptide homologous to known PEP mutases. On the assumption that the biosynthetic genes for FR900098 are clustered on the chromosome, we constructed a large insert fosmid library from S. rubellomurinus genomic DNA. PCR screening of the library using PEP mutase-specific primers allowed identification of four clones encoding the putative PEP mutase. We transferred one of these clones (designated 4G7) to the chromosome of Streptomyces lividans, a genetically tractable organism that is not known to produce phosphonic acid compounds, in an attempt to determine if fosmid 4G7 contained all the genes necessary for production of FR900098. Production of FR900098 by the recombinant S. lividans strain was confirmed by four lines of evidence (Fig. 2).

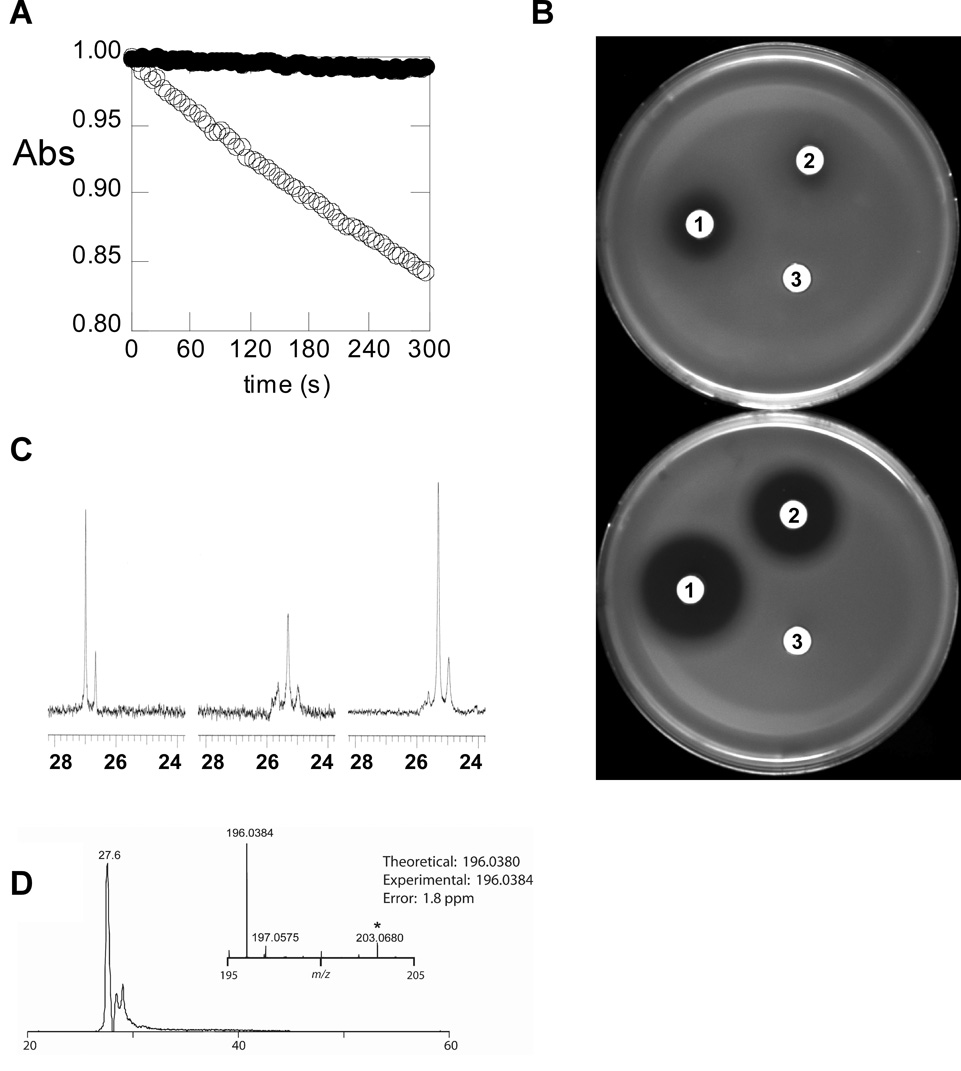

Figure 2.

Evidence for the heterologous production of FR900098. (A) Detection of FR900098 by enzymatic assay. Culture supernatant from the non-producing S. lividans parent strain (open circles) does not affect the reaction catalyzed by E. coli DXR, as measured by observing the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm that results from oxidation of NADPH during the reaction. Culture supernatant from S. lividans 4G7 (filled circles) results in complete inhibition. The initial absorbance has been normalized to 1 for both reactions for ease of comparison. (B) Detection of FR900098 by a phosphonate specific bioassay. The phosphonate-sensitive E. coli indicator strain WM6242 was assayed either uninduced (top) or induced (bottom) allowing for detection of phosphonate containing antibiotics. Disks labeled (1) were soaked with authentic FR900098 (50 µg/ml). Disks labeled (2) were soaked with supernatant from S. lividans 4G7. Disks labeled (3) were soaked with supernatant from the parent S. lividans strain without a cosmid. (C) 31P-NMR spectra of commercial FR900098 (left), culture supernatant from S. lividans 4G7 (center), and the same culture supernatant after addition of commercial FR900098 (right). (D) Selected ion chromatogram for FR900098 +/− 2 ppm from an injection of culture supernatant with summed mass spectrum (inset).

First, supernatant from cultures of S. lividans 4G7 inhibited purified E. coli DXR. This enzyme is the known target of the antibiotic(Kuzuyama et al., 1998) and can be completely inhibited by concentrations of FR900098 as low as 100 nM (data not shown). Supernatant from cultures of S. lividans 4G7 eliminated DXR activity, whereas supernatant from cultures of the parent S. lividans strain grown under the same conditions had no effect (Fig. 2A).

Second, we developed a two plate assay system utilizing an engineered E. coli bioassay strain (desribed in Supplementary Methods) with an IPTG-inducible hypersensitivity to phosphonate antibiotics. In the presence of inducer, both authentic FR900098 (50 µg/ml) and supernatant from S. lividans 4G7 produced substantial zones of inhibition, whereas the parent S. lividans strain did not (Fig. 2B).

Third, 31P-NMR spectroscopy of concentrated S. lividans 4G7 culture supernatant revealed a signal at ca. 25 ppm that was intensified when authentic FR900098 was added to the sample. No new signal was observed, indicating that the phosphonate species in the supernatant is FR900098 or a very closely related compound (Fig. 2C). No peaks are observed in this region of the spectrum in supernatant from cultures of the S. lividans parent strain.

Fourth, the presence of FR900098 in the S. lividans 4G7 culture supernatant was further confirmed by coupled liquid chromatography high-resolution mass spectrometry (LCMS; Fig. 2D). In addition to FR900098, we detected N-acetyl-3-aminophosphonate, suggesting that this compound may be an intermediate in the synthesis of the antibiotic (Fig. S1).

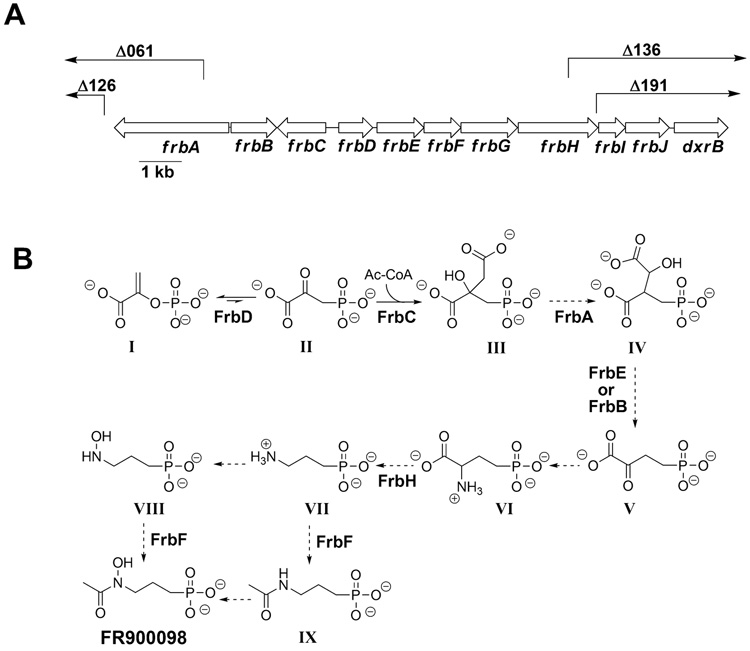

Fosmid 4G7 was sequenced using a transposon-based strategy as described in the Supplementary Methods. The mini-MuAE5 transposon used in this effort also allowed facile construction of deletion sub-clones lacking the region between the site of transposon insertion and the cloning junction with the fosmid vector. We tested a series of progressively larger deletion plasmids for their ability to confer FR900098 production upon S. lividans, resulting in the identification of a minimal 11.3 kb region required for antibiotic synthesis (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) The arrangement of the FR900098 biosynthetic genes. The end points of largest deletions that do not eliminate antibiotic production (Δ126 and Δ191) and smallest deletions that do (Δ061 and Δ136) are also shown. Δ126 ends 117 bp before the end of frbA, Δ191 removes 2233 of 2660 bp of frbA, Δ136 removes 934 of 1886 bp of frbH, and Δ191 removes 51 of 1886 bp of frbH. The region from frbA to frbH is sufficient for production of FR900098 in the heterologous host S. lividans. (B) The proposed biosynthetic pathway for FR900098. The assignment of ORFs to chemical steps is based on the proposed functions as deduced from sequence comparisons. Intermediates in the production of FR900098: I. phosphoenolpyruvate, II. 3-phosphonopyruvate, III. 2-phosphonomethylmalate, IV. 3-phosphonomethylmalate, V. 2-oxo-4-phosphonobutryate, VI. 2-amino-4-phosphonobutyrate, VII. 3-aminopropylphosphonate, VIII. N-hydroxy-3-aminopropylphosphonate, IX. N-acetyl-3-aminopropylphosphonate.

Analysis of the minimal DNA sequence revealed eight open reading frames (ORFs), which were designated frbA-H for FR900098 biosynthesis, including the expected PEP mutase homolog (frbD). In addition, two ORFs (designated frbI and frbJ) immediately downstream of frbH appear to be part of the same operon, although they are not required for successful antibiotic production in S. lividans. Downstream of frbJ and separated from it by a region containing a 38-bp inverted repeat is an ORF that is homologous to the gene for DXR. We have designated this ORF dxrB. Possible functions of the Frb proteins were assigned based on homology to proteins of known function (Table S1).

The initial step in FR900098 biosynthesis is presumed to be the PEP mutase-catalyzed formation of phosphonopyruvate, a highly unfavorable reaction (equilibrium is ≥ 500:1 in favor of PEP(Bowman et al., 1990)). In known phosphonate biosynthetic pathways, the second step is an irreversible decarboxylation of phosphonopyruvate, which provides a thermodynamic driving force to overcome the unfavorable initial step (Fig. 1B). Surprisingly, there is no recognizable homolog of phosphonopyruvate decarboxylase in the FR900098 gene cluster. A clue to the fate of phosphonopyruvate is suggested by the presence of three putative ORFs (frbA, frbB, and frbE, Table S1, Fig. 3A) that are related to genes encoding enzymes in the TCA cycle. A fourth (frbC) is homologous to homocitrate synthase, which catalyzes an acetyl-CoA condensation similar to that catalyzed by citrate synthase. Considering that phosphonopyruvate is a structural analog of oxaloacetate, we proposed that the initial steps in biosynthesis of FR900098 parallel the TCA cycle (Fig. 3B). Thus, the thermodynamically favorable reactions catalyzed by the homocitrate synthase and isocitrate dehydrogenase homologs would provide the necessary thermodynamic driving force. Hemmi et al.(1982) have previously suggested that such a pathway would be feasible, and there is a precedent in the bialaphos biosynthetic pathway in which phosphinopyruvate is converted to the phosphinic acid analog of α-ketoglutarate (αKG) by an analogous series of reactions (reviewed by Seto and Kuzuyama(1999)).

To test the prediction that frbC and frbD encode phosphonomethylmalate synthase and PEP mutase, respectively, recombinant FrbC and FrbD were purified and assayed. Using an in vitro assay based on a method commonly used to assay citrate synthase, we observed CoASH formation from acetyl-CoA and phosphonopyruvate in the presence of FrbC (Fig. 4A), suggesting that FrbC catalyzes condensation of the two molecules driven by CoA thioester hydrolysis. We could further detect CoASH formation starting from PEP and acetyl-CoA if both FrbC and FrbD were present, confirming that FrbD is a PEP mutase. 31P-NMR analysis of the reaction products revealed the presence of a new phosphonic acid (data not shown), which was confirmed to be 2-phosphonomethylmalate by LCMS (Fig. 4B).

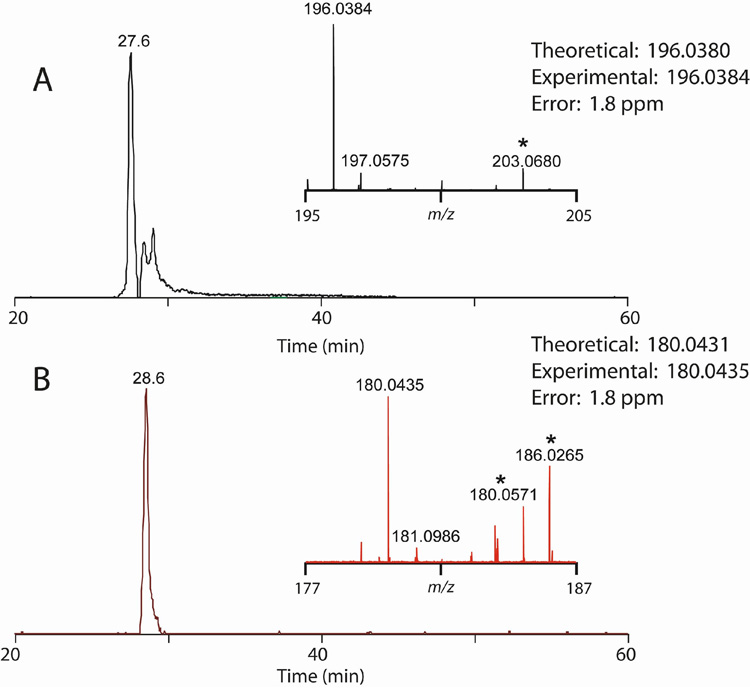

Figure 4.

(A) In vitro CoASH formation from acetyl-CoA and phosphonopyruvate or phosphoenolpyruvate depends on the presence of FrbC or FrbC + FrbD respectively. (B) Selected ion chromatogram for 2-phosphonomethylmalate +/− 1 ppm from an injection of reaction mixture (20 µL) with summed mass spectrum (inset). (C) High resolution MS2 spectrum for the precursor ion at negative m/z 227 showing the predictable losses of water and the added acetyl group.

The product of the three TCA cycle analog reactions, 2-oxo-4-phosphonobutyrate, would be a phosphonate analog of αKG, which could be converted into 3-aminopropylphosphonate by consecutive amination and decarboxylation reactions. FrbH is a homolog of PLP-dependent enzymes that are known to catalyze both reaction types (e.g. histidinol phosphate aminotransferase and threonine phosphate decarboxylase) and could be involved in either reaction.

To complete the biosynthesis of FR900098, the amino group of 3-aminopropylphosphonate would need to be both acetylated and hydroxylated. Because we detect N-acetyl-3-aminophosphonate and not N-hydroxy-3-aminophosphonate by LCMS of the heterologous producer, we suggest the order is acetylation followed by hydroxylation. FrbF shows high identity to N-acetyltransferases and likely performs that reaction here. The identity of the enzyme responsible for the subsequent hydroxylation reaction is less clear. FrbJ is homologous to αKG-dependent dioxygenases, a class of enzymes that may be capable of N-hydroxylation, but catalysis of that type of reaction by an enzyme of this class is without precedent. We propose no role for FrbG, which shows only very weak homology to the small subunit of glutamate synthase. More definitive assignment of the function of these enzymes will have to await in vitro biochemical and in vivo genetic experiments.

Although dxrB is not required for production of FR900098, its presence near the biosynthetic genes suggests a role in self-resistance. The use of resistant forms of target enzymes has been observed in other organisms. For example, a cycloserine-producing S. lavendulae strain has been shown to also produce a cycloserine-resistant variant of alanine racemase, the target of that inhibitor(Noda et al., 2004). We are currently investigating whether the DXR encoded within the FR900098 cluster is indeed resistant to FR900098.

Because we propose a role for the dxrB gene in self-resistance, we have tentatively defined the FR900098 biosynthetic gene cluster as comprising the entire region from frbA to dxrB, although the frbA-H fragment alone is sufficient for production of FR900098 in S. lividans.

Significance

Our data suggest that the pathway for biosynthesis of this antibiotic may have evolved from the tricarboxylic acid cycle of central metabolism and utilizes an unusual thermodynamic driving reaction distinct from other phosphonate biosynthetic pathways. Heterologous production of FR900098 is possible using the identified genes, allowing for creation of engineered strains that greatly overproduce the antibiotic. It is also worth noting that our proposed FR900098 biosynthetic pathway includes two potent bioactive compounds as intermediates: 2-amino-4-phosphonobutyrate and 3-aminopropylphosponate, which are known mimics of the major neurotransmitters glutamate and gamma-aminobutyrate respectively(Jane, 2000). Thus in addition to the biosynthesis of the antimalarial compound FR900098, elucidation of this pathway in S. rubellomurinus has uncovered a biosynthetic route to these two well-known neuroactive compounds.

Experimental procedures

Cloning of the FR900098 gene cluster from S. rubellomurinus

S. rubellomurinus strain 5818 (ATCC 31215) was provided by the Fujisawa Pharmaceutical Co. (Osaka, Japan). S. lividans 66 was obtained from the USDA Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection (Peoria, IL). See Supplementary Methods for details on the strains and plasmids (Fig. S2) used for cloning. The PEP mutase gene in S. rubellomurinus was identified by PCR amplification with degenerate primers (see Supplementary Methods), which were designed using CODEHOP(Rose et al., 1998) based on known PEP mutase sequences. Specific primers were designed to the S. rubellomurinus PEP mutase gene based on the sequence of the amplification product. A genomic library of S. rubellomurinus was prepared using genomic DNA obtained by a modification of the method of Kieser et al.(2000) and is described in detail in the Supplementary Methods. This genomic DNA was partially digested to yield fragments of ~20–60 kb, which were then ligated into pJK050. E. coli WM3118 cells were transfected with the resulting fosmids. The E. coli library was screened by PCR for clones containing the PEP mutase sequence. To add the functions necessary for transfer and integration into S. lividans, the purified fosmids were individually recombined in vitro with pAE4 using BP clonase according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Fosmid:pAE4 cointegrants were isolated after transformation of E. coli DH5α and subsequently moved into the conjugal donor strain E. coli WM3608(Blodgett et al., 2005) for transfer to S. lividans 66. Conjugal transfer was performed as described by Martinez et al.(2004) with modifications as detailed in the Supplementary Methods.

Heterologous expression of the FR900098 gene cluster in S. lividans

To check for production of FR900098, S. lividans 4G7 was plated on Hickey-Tresner agar (Kieser et al., 2000) or ISP4. After 4 days, the agar-solidified medium was liquefied by freezing and subsequent thawing, and the liquid portion was decanted from the remaining agar residue. To determine the presence or absence of FR900098 in this supernatant, 5 µL was added to a DXR enzyme reaction, and the reaction rate was compared to a control with 5 µL of supernatant from a non-producing strain. Purified recombinant E. coli DXR used in the assays was prepared as described in the Supplementary Methods.

The biosassay strain E. coli WM6242, which expresses the phosphonate uptake system encoded by phnCDE under the control of a Ptac promoter was constructed and used as described in Supplementary Methods. Filter discs (6 mm) were impregnated with 9 µl of the test solutions and placed on the surface of the solidified plates. The bioassay plates were incubated for 12 h, and the size of the growth inhibition zone scored. To confirm the heterologous production of FR900098, inhibition zones from S. lividans 4G7 culture supernatant were compared to supernatant from the S. lividans parent strain and a solution of authentic FR900098 (50µg/ml).

For 31P-NMR detection of FR900098, culture supernatant was concentrated approximately 10-fold by evaporation. 31P-NMR spectra were externally referenced to an 85 % phosphoric acid standard set at 0 ppm. To confirm that the observed peak corresponded to FR900098, an authentic sample of FR900098 was added to a concentration of 100 µg/mL, and the spectrum of the sample was recorded again under identical conditions. For the mass spectrometric detection of FR900098 and N-acetyl-3-aminophosphonate, samples were prepared, separated on an Atlantis HILIC silica column, and infused into a LTQ-FT mass spectrometer for negative ion FTMS detection as described in detail in Supplementary Methods. The identities of FR900098 and N-acetyl-3-aminophosphonate were confirmed by both accurate mass analysis (< 2 ppm) and tandem MS fragmentation.

DNA sequencing and deletion analysis of cosmid 4G7

To sequence fosmid 4G7 a library of transposon insertions was generated using the mini-Mu transposon encoded in pAE5 and sequenced as described in Supplementary Methods. Potential open-reading frames were identified using BLAST analysis (Altschul et al., 1990), GeneMark(Borodovsky and McIninch, 1993), and visual inspection. To determine the portion of the cosmid required for antibiotic production, various deletions were made by site-specific recombination between frt or loxP sites present adjacent to the cloning site of the fosmid vector and the matching site on selected mini-Mu transposon insertions. These deletions remove all DNA between the site of the transposon insertion (chosen based on the DNA sequencing results) and the cloning junction in fosmid 4G7. The resulting recombinant plasmids were integrated into S. lividans 66, and exconjugants were assayed for the ability to produce FR900098 using the E. coli DXR inhibition assay and by mass spectrometry. The complete sequence of this 14.4 kb region has been deposited in GenBank with accession number DQ267750.

Determination of enzymatic activity of FrcB and FrbD

The N-His6-tagged-FrbC and FrbD proteins were purified after recombinant expression of genes were obtained by PCR amplification from the fosmid 4G7 as described in Supplementary Methods. Phosphonomethylmalate synthase activity was assayed by tracking CoASH formation in a reaction similar to that used for phosphinomethylmalate synthase (Shimotohno et al., 1988) starting from either phosphoenolpyruvate or phosphonopyruvate, using FrbD + FrbC or FrbC, respectively. Phosphonomethylmalate formation was confirmed using LCMS by both accurate mass analysis (< 2 ppm) and tandem MS fragmentation (see Supplementary Methods for a detailed description of the enzyme assay conditions and analytical methods).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Fujisawa Co. for providing S. rubellomurinus 5818, Adam Guss for constructing strain WM3118, and Jun Kai Zhang for constructing plasmid pJK050. We are also grateful to Deborah Dunaway-Mariano for providing phosphonopyruvate and Chris Wright and Laura Guest of the UIUC Biotechnology Center for their help with sequencing. This work was supported by NIGMS Grants GM059334B to W.W.M., GM077596 to H.Z., and GM077596 to W.W.M., W.A.V., H.M.Z. and N.L.K., US National Institutes of Health Chemical Biology Interface Training Grant 5T32 GM070421, and a National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellowship to A.C.E. B.M.G. was supported by the Institute for Genomic Biology Fellows Program.

Abbreviations

- AEP

2-aminoethylphosphonate

- DXR

1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase

- αKG

α-ketoglutarate

- ORF

open reading frame

- PEP

phosphoenolpyruvate

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PLP

pyridoxal 5’-phosphate

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry RJ, Bowman E, McQueney M, Dunaway-Mariano D. Elucidation of the 2-aminoethylphosphonate biosynthetic pathway in Tetrahymena pyriformis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988;153:177–182. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blodgett JA, Zhang JK, Metcalf WW. Molecular cloning, sequence analysis, and heterologous expression of the phosphinothricin tripeptide biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces viridochromogenes DSM 40736. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:230–240. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.1.230-240.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodovsky M, McIninch J. GeneMark: parallel gene recognition for both DNA strands. Comp. Chem. 1993;17:123–133. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman ED, McQueney MS, Scholten JD, Dunaway-Mariano D. Purification and characterization of the Tetrahymena pyriformis P-C bond forming enzyme phosphoenolpyruvate phosphomutase. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7059–7063. doi: 10.1021/bi00482a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmi K, Takeno H, Hashimoto M, Kamiya T. Studies on phosphonic acid antibiotics. IV. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of analogs of 3-(N-acetyl-N-hydroxyamino)-propylphosphonic acid (FR-900098) Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1982;30:111–118. doi: 10.1248/cpb.30.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka T, Goda M, Kuzuyama T, Takei N, Hidaka M, Seto H. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of fosfomycin biosynthetic genes of Streptomyces wedmorensis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1995;249:274–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00290527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka T, Mori M, Imai S, Hara O, Nagaoka K, Seto H. Studies on the biosynthesis of bialaphos (SF-1293). 9. Biochemical mechanism of C-P bond formation in bialaphos: discovery of phosphoenolpyruvate phosphomutase which catalyzes the formation of phosphonopyruvate from phosphoenolpyruvate. J. Antibiot. 1989;42:491–494. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jane DE. Neuroactive Aminophosphonic and Aminophosphinic Acid Derivatives. In: Kukjar VP, Hudson HR, editors. Aminophosphonic and Aminophosphinic Acids. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2000. pp. 483–535. [Google Scholar]

- Jomaa H, Wiesner J, Sanderbrand S, Altincicek B, Weidemeyer C, Hintz M, Turbachova I, Eberl M, Zeidler J, Lichtenthaler HK, et al. Inhibitors of the nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis as antimalarial drugs. Science. 1999;285:1573–1576. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA. Practical Streptomyces Genetics. Norwich, England: The John Innes Foundation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzuyama T, Shimizu T, Takahashi S, Seto H. Fosmidomycin, a Specific Inhibitor of 1-Deoxy-D-Xylulose 5-Phosphate Reductoisomerase in the Nonmevalonate Pathway for Terpenoid Biosynthesis. Tet. Lett. 1998;39:7913–7916. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez A, Kolvek SJ, Yip CL, Hopke J, Brown KA, MacNeil IA, Osburne MS. Genetically modified bacterial strains and novel bacterial artificial chromosome shuttle vectors for constructing environmental libraries and detecting heterologous natural products in multiple expression hosts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:2452–2463. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2452-2463.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda M, Kawahara Y, Ichikawa A, Matoba Y, Matsuo H, Lee DG, Kumagai T, Sugiyama M. Self-protection mechanism in D-cycloserine-producing Streptomyces lavendulae. Gene cloning, characterization, and kinetics of its alanine racemase and D-alanyl-D-alanine ligase, which are target enzymes of D-cycloserine. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:46143–46152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404603200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuhara M, Kuroda Y, Goto T, Okamoto M, Terano H, Kohsaka M, Aoki H, Imanaka H. Studies on new phosphonic acid antibiotics. I. FR-900098, isolation and characterization. J. Antibiot. 1980;33:13–17. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.33.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohmer M. The discovery of a mevalonate-independent pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis in bacteria, algae and higher plants. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1999;16:565–574. doi: 10.1039/a709175c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose TM, Schultz ER, Henikoff JG, Pietrokovski S, McCallum CM, Henikoff S. Consensus-degenerate hybrid oligonucleotide primers for amplification of distantly related sequences. Nuc. Acids Res. 1998;26:1628–1635. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.7.1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlitzer M. Malaria chemotherapeutics part 1: History of antimalarial drug development, currently used therapeutics, and drugs in clinical development. Chem. Med. Chem. 2007;2:944–986. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Berger S, Heinzelmann E, Muschko K, Welzel K, Wohlleben W. Biosynthetic gene cluster of the herbicide phosphinothricin tripeptide from Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tu494. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:7093–7102. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7093-7102.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel HM, Freeman S, Seto H, Knowles JR. Phosphonate biosynthesis: isolation of the enzyme responsible for the formation of a carbon-phosphorus bond. Nature. 1988;335:457–458. doi: 10.1038/335457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto H, Kuzuyama T. Bioactive natural products with carbon-phosphorus bonds and their biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1999;16:589–596. doi: 10.1039/a809398i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimotohno KW, Seto H, Otake N, Imai S, Murakami T. Studies on the Biosynthesis of Bialaphos (Sf-1293) .8. Purification and Characterization of 2-Phosphinomethylmalic Acid Synthase from Streptomyces Hygroscopicus Sf-1293. J. Antibiot. 1988;41:1057–1065. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow RW, Guerra CA, Noor AM, Myint HY, Hay SI. The global distribution of clinical episodes of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2005;434:214–217. doi: 10.1038/nature03342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.