Abstract

Intravenous delivery of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) prepared from bone marrow (BMSCs) reduces infarction volume and ameliorates functional deficits in a rat cerebral ischemia model. MSC-like multipotent precursor cells (PMSCs) have also been suggested to exist in peripheral blood. To test the hypothesis that treatment with PMSCs may have a therapeutic benefit in stroke, we compared the efficacy of systemic delivery of BMSCs and PMSCs. A permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) in rat was induced by intraluminal vascular occlusion with a microfilament. Rat BMSCs and PMSCs were prepared in culture and intravenously injected into the rats 6 h after MCAO. Lesion size was assessed at 6 h, and 1, 3, and 7 days using MR imaging and histology. The hemodynamic change of cerebral blood perfusion on stroke was assessed the same times using perfusion-weighted image (PWI). Functional outcome was assessed using the treadmill stress test. Both BMSCs and PMSCs treated groups had reduced lesion volume, improved regional cerebral blood flow, and functional improvement compared to the control group. The therapeutic benefits of both MSC-treated groups were similar. These data suggest that PMSCs derived from peripheral blood could be an important cell source of cell therapy for stroke.

Keywords: regeneration, stem cells, stroke, transplantation

INTRODUCTION

Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from bone marrow (BMSCs) after ischemia onset can reduce infarction size and improve functional outcome in rodent cerebral ischemia models (Chen et al., 2001; Honma et al., 2006; Horita et al., 2006; Iihoshi et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2006; Nomura et al., 2005). Improved function after BMSCs delivery has also been reported in experimental model of spinal cord injury (Chopp et al., 2000). Although MSCs can differentiate into cells of neuronal and glial lineage under appropriate conditions (Honma et al., 2006; Kobune et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2006; Prockop, 1997; Woodbury et al., 2000), the beneficial effects of MSCs in cerebral ischemia are thought to be primarily the result of angiogenesis and neuroprotective effects (Chen et al., 2001; Horita et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2006; Nomura et al., 2005). Exogenously applied MSCs have been shown to home to injured tissues and repair them by producing chemokines, differentiating into specific cell types, or possibly by cell or nuclear fusion with host cells (Prockop et al., 2003).

Multipotent precursor cells have also been suggested to exist in peripheral bloods. Normal individuals had CD34− mononuclear cells in a fraction of elutriated blood cells that fulfilled criteria for mesenchymal stem cells (Huss et al., 2000; Zvaifler et al., 2000). These cells can be expanded in culture and have a capacity for differentiation into fibroblast, osteoblast, and adipocyte lineages.

While intravenous injection of BMSCs reduces infarction size and improves functional outcome in a rat stroke model (Honma et al., 2006; Horita et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2006; Nomura et al., 2005), the therapeutic benefit of MSC-like multipotent precursor cells derived from peripheral blood (PMSCs) transplantation in cerebral ischemia is still uncertain. In the present study, we isolated and expanded PMSCs from rat peripheral blood. PMSCs and BMSCs were delivered intravenously in a cerebral ischemia model to compare the relative efficacy of these two types of MSCs on infarction size, cerebral blood flow and functional outcome.

METHODS

Preparation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Prepared from Rat Bone Marrow

The use of animals in this study were approved by the animal care and use committee of Sapporo Medical University, and all procedures were carried out in accordance with institutional guidelines. Bone marrow was obtained from femoral bones of adult Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 200–250 g. Rats were anesthetized with ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) i.p. A small hole (2 × 3 mm) in the femoral bone was made with an air drill following skin incision (1 cm), and 0.5 mL of bone marrow was aspirated with an 18-gauge needle. Bone marrow (0.5 mL) was mixed with 10 mL of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Sigma, USA St. Louis, MD) + 10% FBS (Gibco, USA) + 0.2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma, USA) + penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma, USA) solution, plated in 100-cm2 plastic tissue culture flasks, and incubated for 3 days. After washing away the free cells, the adherent cells were cultured in the same medium in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. After reaching confluence, they were harvested and cryopreserved as primary BMSCs.

Preparation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Rat Peripheral Blood

Peripheral blood was obtained from adult Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 200–250 g. Rats were anesthetized with ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) i.p. Peripheral blood (7–10 mL) was aspirated from vena cava superior with an 18-gauge needle. The peripheral blood was mixed with 30 mL of red blood cell (RBC) lysis solution (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN), was reacted for 5 min at room temparature, and was centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 2 min. The RBC lysate supernatant was poured off, and the mononuclear cell fraction was resuspended with DMEM + 10 % FBS + 0.2 mM L-glutamine + penicillin/streptomycin solution. Cells were plated in 100-cm2 plastic tissue culture flasks, and the adherent cells were cultured in the same medium in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. After reaching confluence, they were harvested and cryopreserved as PMSCs.

Phenotypic Characterization of the Primary BMSCs and PMSCs

Flow cytometric analysis of BMSCs and PMSCs was performed as previously described (Honma et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2006). Briefly, cell suspensions were washed twice with PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). For direct assays, 1 million cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated CD45 (Leukocyte Common Antigen; BD Bioscience pharmingen, San Jose, CA), and PE-conjugated CD73 (Ecto-5′-nucleotidase; BD Bioscience Pharmingen), PE-CD90 (Thy-1; eBioscience, San Diego, CA), and PE-CD106 (VCAM-1; BD Bioscience pharmingen) at 4°C for 30 min, and then washed twice with PBS containing 0.1% BSA. The cells were analyzed by cytometric analysis using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) with the use of CellQuest software.

Cerebral Ischemic Model

The rat middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model was used as a stroke model. We induced permanent MCAO by using a previously described method of intraluminal vascular occlusion (Longa et al., 1989; Nomura et al., 2005). Adult female Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 250–300 g were initially anesthetized with ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) i.p. A length of 20.0–22.0-mm 4-0 surgical suture (Dermalon, Sherwood Davis and Geck, UK), with the tip rounded by heating near a flame, was advanced from the external carotid artery into the lumen of the internal carotid artery until it blocked the origin of the middle cerebral artery (MCA).

Transplantation Procedures

Experiments consisted of three groups (n = 85). In group 1 (control), rats were given medium alone (without donor cell administration) injected i.v. at 6 h after MCAO (just after the initial magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] measurement; n = 15). In group 2, rats were given rat BMSCs (1.0 × 106) in 1 mL of total fluid volume (DMEM) injected i.v. at 6 h after MCAO (n = 15). In group 3, rats were given rat PMSCs (1.0 × 106) injected i.v. at 6 h after MCAO (n = 15). All rats were daily injected with cyclosporine (10 mg/kg) i.p. Five rats in each group were used to calculate the infarct lesion volume, and the remaining rats were used for the additional histological, behavior, and other analysis.

In some experiments, Adex1CAlacZ adenovirus was used to transduce the LacZ gene into the MSCs. Details of the construction procedures are described elsewhere (Iihoshi et al., 2004; Nakagawa et al., 1998; Nakamura et al., 1994; Takiguchi et al., 2000). This adenoviral vector carries an adenovirus serotype-5 genome lacking the E1A, E1B, and E3 regions to prevent virus replication, and contains the Escherichia coli β-galactosidase gene, lacZ gene, between the CAG promoter, composed of the cytomegalovirus enhancer plus the chicken β-actin promoter, and the rabbit β-globin polyadenylation signal in the place of the E1A and E1B regions. The recombinant adenovirus was propagated and isolated in 293 cells. Viral solutions were stored at −80°C until use. For in vitro adenoviral infection, 1.0 × 106 rat MSCs were placed with Adex1CAlacZ at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50 pu/cell for 1 h and incubated at 37°C in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Rats were anesthetized with ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) i.p. The femoral vein of rats was cannulated for contrast agent injection. Each rat was placed in an animal holder/MRI probe apparatus and positioned inside the magnet. The animal’s head was held in place inside the imaging coil. All MRI measurements were performed using a 7-Tesla, 18-cm-bore superconducting magnet (Oxford Magnet Technologies) interfaced to a UNITYINOVA console (Oxford Instruments, UK, and Varian, Inc., Palo Alto, CA).

T2-weighted images (T2WI) were obtained from a 1.0-mm-thick coronal section with a 0.5-mm gap using a 30 mm × 30 mm field of view, TR = 3000 msec, TE = 37 msec, and reconstructed using a 256 × 128 image matrix. Diffusion-weighted images (DWI) were obtained at the same condition as T2WI except b value (b value = 966) and image matrix (128 × 128). Accurate positioning of the brain was performed to center the image slice 5 mm posterior to the rhinal fissure with the head of the rat held in a flat skull position. MRI measurements were obtained 6 h, 1, 3, and 7 days after MCAO.

The ischemic lesion area was calculated from both T2WI and DWI using imaging software (Scion Image, Version Beta 4.0.2, Scion Corp.), based on the previously described method (Neumann-Haefelin et al., 2000; Nomura et al., 2005). For each slice, the higher intensity lesions in both T2WI and DWI where the signal intensity were 1.25 times higher than the counterpart in the contralateral brain lesion were marked as the ischemic lesion area, and infarct volume was calculated taking slice thickness (1 mm/slice) into account.

Dynamic Susceptibility Contrast-Enhanced Perfusion-Weighted Imaging (PWI)

Perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI) was acquired using T2*-weighted (TR = 13 msec, TE = 6.0 msec) gradient echo sequence. A dynamic image series of 30 measurements resulted in a total scan time of 26 sec, with a field of vision (FOV) of 30 mm, and image acquisition matrix of 128 × 64, which was interpolated by zero-filling to 512 × 512. During the dynamic series, a triple dose (0.6 mL/kg) bolus injection of Magnevist (Schering AG, Germany) was started after the 5th acquired volume to ensure a sufficient pre-contrast baseline. Images were reconstructed by an Inova Vision. PWI measurements were obtained 6 h, 1, 3, and 7 days after MCAO. For the PWI and PWI-derived parameter maps, only one representative slice (involving cortex and stria terminalis) with the maximum lesion involving both cortex and striatum was chosen for cerebral blood flow (CBF) quantification. The readout of abnormal regional CBF (rCBF) from the regions of perfusion deficiency as a percentage of that measured in the contralateral brain was generated using Perfusion Solver software. Regions of interest (ROI) consist of four groups, based on the results of DWI, T2WI, and PWI. ROI-1 is defined as abnormal in all images, ROI-2 as normal in only T2WI and abnormal in others, and ROI-3 as abnormal in only PWI and normal in others, and ROI-4 as normal in all images (see Fig. 5 below).

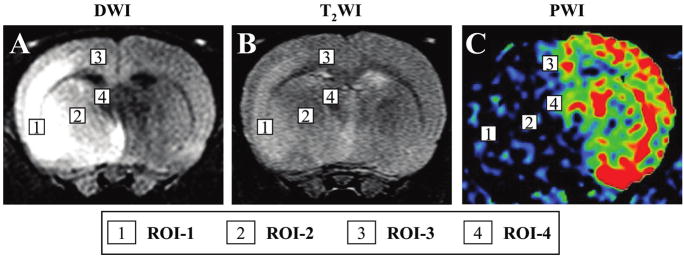

FIG. 5.

Region of interest (ROI) for dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI) analysis (C). PWI analysis was carried out at four regions of interest (ROI) indicated by the boxed numbered areas on the lesion side of the brain (A, B).

Histological Analysis

TTC staining and quantitative analysis of infarct volume

One week after transplantation, the rats were anesthetized with ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) i.p. The brains were removed carefully and dissected into coronal 1-mm sections using a vibratome. The fresh brain slices were immersed in a 2% solution of 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) in normal saline at 37°C for 30 min (Bederson et al., 1986). The cross-sectional area of infarction in each brain slice was examined with a dissection microscope and was measured using an image analysis software (Adobe Photoshop). The total infarct volume for each brain was calculated by summation of the infracted area of all brain slices.

Hematoxylin and Eosin staining

The rats were anesthetized with ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) i.p. and perfused through the heart, first with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then with a fixative solution containing 10% paraformaldehyde in 0.14 M Sorensen’s phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Brains were removed and placed in 10% paraformaldehyde in PBS overnight, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Transverse sections (1.5 μm) were cut, and were counter-stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Detection of Donor MSCs and Phenotypic Analysis In Vivo

X-gal staining

One week after transplantation, brains of the deeply anesthetized rats were removed and fixed in 0.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 1 h. Brains were removed, brain slices (1000 μm) were cut with a vibratome, and β-galactosidase expressing cells were detected by incubating the sections at 37°C overnight with X-gal to a final concentration of 1 mg/mL in X-Gal developer (35 mM K3Fe(CN)6/35 mM K4Fe(CN)63H2O/2 mM MgCl2 in PBS) to form a blue reaction product within the cell.

Immunohistochemistry

One week after transplantation, analysis of the transplanted cells in vivo was carried out using laser scanning confocal microscopy. Brains of the deeply anesthetized rats were removed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, dehydrated with 30% sucrose in 0.1 M PBS for overnight, and frozen in powdered dry ice. Coronal cryostat sections (10 μm) were processed for immunohistochemistry. To identify the cells derived from the donor peripheral blood, immunolabeling studies were performed with the use of antibodies to beta-galactosidase (rhodamine-labeled polyclonal rabbit anti-beta-galactosidase antibody; DAKO). To excite the rhodamine fluorochrome (red), a 543-nm laser line from a HeNe laser was used. Confocal images were obtained using a Zeiss laser scanning confocal microscope with the use of Zeiss software.

Capillary Vessels in Ischemic Brain

To examine capillary vessels in ischemic brain, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) dextran (2 × 106 molecular weight, Sigma; 0.1 mL of 50 mg/mL) was administered intravenously to the ischemic rats subjected to 7 days of MCAO. Brains were removed, and brain slices (100 μm) were cut with a vibratome. To excite the FITC (green), a 488-nm laserline generated by an argon laser was used. Confocal images were obtained using a Zeiss laser scanning confocal microscope with the use of Zeiss software, and vessel volumes were measured in the three dimensions using the software of Zeiss LSM.

Treadmill Stress Test

Rats were trained 20 min per day for 2 days a week to run on a motor-driven treadmill at a speed of 20 m/min. Rats were placed on a moving belt facing away from the electrified grid and induced to run in the direction opposite of the movement of the belt. Thus, to avoid foot-shocks (with intensity in 1.0 mA), the rats had to move forward. Only the rats that had leaned to avoid the mild electrical shock were included in this study (n = 15). The maximum speed at which the rats could run on a motor-driven treadmill was recorded.

Statistical Analysis

The lesion volume, the rCBF ratio, the capillary vascular volume, and the behavior scores (treadmill stress test) recorded were statistically analyzed. Data are presented as mean values ± SD. Differences among groups were assessed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Scheffe’s post hoc test or Kruskal-Wallis test to identify individual group differences. Differences were deemed statistically significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of BMSCs and PMSCs

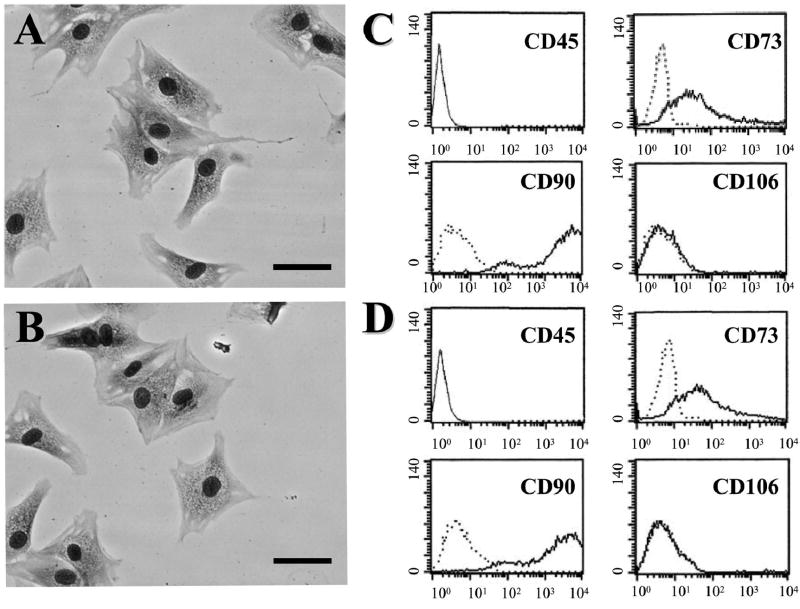

BMSCs and PMSCs cultured as plastic adherent cells could be maintained in vitro. The morphological features of the BMSCs are shown in Figure 1A. Characteristic flattened and spindle-shaped cells can be recognized. An antigenic characteristic feature of BMSCs is a CD45−, CD73+, CD90+, CD106− cell surface phenotype (Fig. 1C). The morphological (Fig. 1B) and antigenic (Fig. 1D) characteristics of PMSCs are very similar to those of BMSCs.

FIG. 1.

May–Giemsa staining of BMSCs (A) and PMSCs (B). Scale bar = 20 μm. Flow cytometric analysis of surface antigen expression on BMSCs (C) and PMSCs (D). The cells were immunolabeled with FITC-conjugated and PE-conjugated monoclonal antibody specific for the indicated surface antigen. Dead cells were eliminated by forward and side scatter.

Characterization of Ischemic Lesion Size by Magnetic Resonance Image Analysis

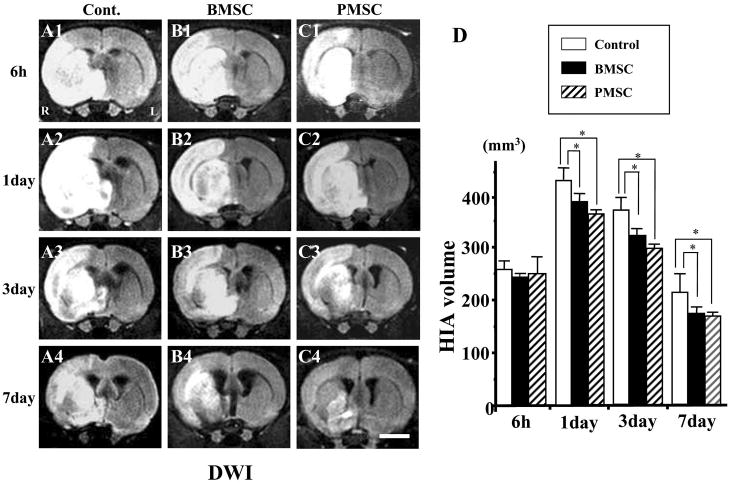

An estimate of lesion size was obtained using in vivo MRI. Brain images (DWI and T2WI) were collected from all experimental animals at 6 h, and 1, 3, and 7 days after MCAO. The cells were intravenously delivered immediately after the 6-h MRI. The upper row in Figure 2A corresponds to 6-h DWI post-MCAO for control (A1), BMSCs (B1), and PMSCs (C1) injected rats. Respective images are shown at 1, 3, and 7 days for each group. These coronal forebrain sections were obtained at the level of caudato-putamen complex. Note the reduction in density in lesions on the right side of the brains that were subjected to ischemic injury. Lesion volume (mm3) was determined by analysis of high intensity areas on serial images collected through the cerebrum.

FIG. 2.

Evaluation of the ischemic lesion volume with diffusion-weighted images (DWI). BMSCs or PMSCs were intravenously injected immediately after the initial MRI scanning (6 h after MCAO). Images obtained 6 h, and 1, 3, and 7 days MCAO in medium-injected (A1–4), BMSC-treated (B1–4), and PMSC-treated group (C1–4). Summary of lesion volumes evaluated with DWI in each groups (D). Scale bar = 3 mm. *p < 0.05.

At 6-h post-MCAO, lesion volume of DWI was similar for the three groups (Fig. 2D). Lesion volume increased at 1 day, but was less for both the BMSC and PMSC groups. The control lesion group showed a reduced lesion volume at 3 and 7 days, but the MSC groups showed greater reduction in lesion volume (Fig. 2D).

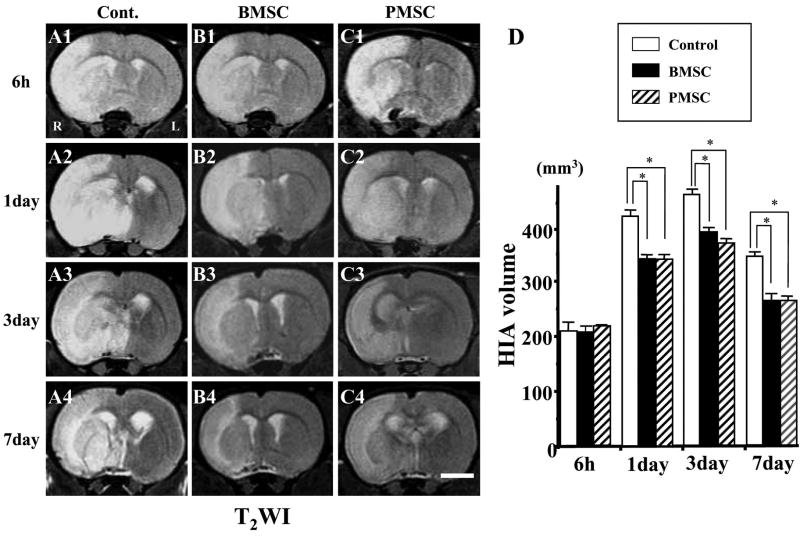

Using T2WI (Fig. 3), infarction volume was similar in the three groups at 6-h post-MCAO (Fig. 3D). Both the BMSC and PMSC injected groups showed reduced lesion volume at 1, 3, and 7 days post-MCAO.

FIG. 3.

Evaluation of the ischemic lesion volume with T2-weighted images (T2WI). BMSCs or PMSCs were intravenously injected immediately after the initial MRI scanning (6 h after MCAO). Images obtained 6 h, and 1, 3, and 7 days MCAO in medium-injected (A1–4), BMSC-treated (B1–4), and PMSC-treated group (C1–4). Summary of lesion volumes evaluated with T2WI in each groups (D). Scale bar = 3 mm. *p < 0.05.

A difference between DWI and T2WI was observed. Lesion volume decreased after 1 day in the three groups in the DWI analysis. Using T2WI, lesion volume increased from 1 to 3 days. However, the BMSC and PMSC groups showed reduced volumes in both DWI and T2WI analysis.

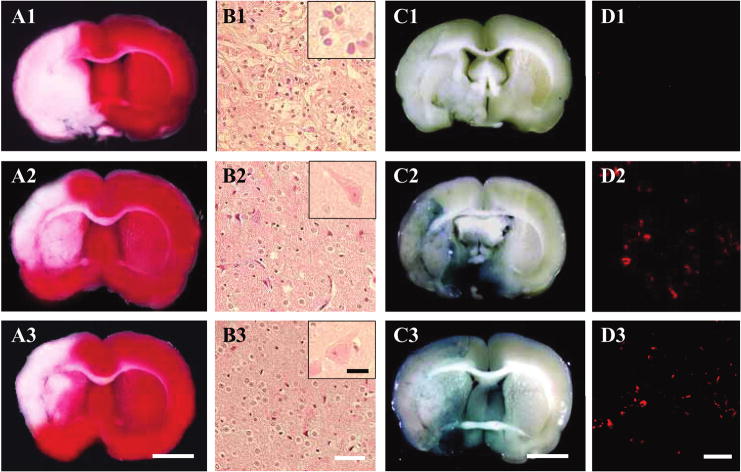

Histological Determination of Infarction Volume

After completion of the MRI analysis to estimate lesion volume, before and after cell delivery, the animals were perfused and stained with TTC to obtain a second independent measure of infarction volume. Normal brain (gray matter) tissue typically stains with TTC, but infracted lesions show no or reduced staining (Bederson et al., 1986). TTC staining that was obtained 1 week after MCAO without cell transplantation is shown in Figure 4A-1. Note the reduced staining on the lesion side. Lesion volume was calculated by measuring the area of reduced TTC staining in the forebrain. As with MRI analysis, there was a progressive reduction in infarction size with both BMSCs (Fig. 4A-2) and PMSCs (Fig. 4A-3) treatment. Lesion volume was 263.0 ± 35.26 mm3 (control group; n = 5), 180.0 ± 5.89 mm3 (BMSCs transplantation; n = 5), and 185.86 ± 19.12 mm3 (PMSCs; n = 5, p < 0.05).

FIG. 4.

TTC brain section slices stained with 2,3,5–triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) to visualize the ischemic lesions 7 days after MCAO. TTC-stained brain slices from medium-injected MCAO model rats (A1), following BMSC-treated (A2), and PMSC-treated (A3) groups. The Sections were also stained with hematoxylin and eosin at 7 days post-MCAO. Although a larger number of apparent inflammatory cells were obvious in the lesion without cell transplantation (B1), parenchymal brain tissue was greatly preserved in the BMSC-treated (B2) and PMSC-treated group (B3). Inflammatory cells in the lesion were shown in insert of B1. On the other hand, preserved neurons in the lesion were shown in insert of B2 and B3. Intravenously administrated BMSCs and PMSCs accumulated in and around the ischemic lesion hemisphere. BMSCs and PMSCs were transfected with the reporter gene LacZ. Transplanted LacZ-positive MSCs (blue cells) were present in the ischemic lesion (BMSCs, C2; PMSCs, C3). Brain from control (MSC transplantation without LacZ transfection) injected animals with comparable X-gal staining is shown in C1. Confocal images (BMSCs, D2; PMSCs, D3) demonstrating a large number of LacZ-positive cells in the lesion hemisphere. Confocal image of non-treated group is shown in D1. Scale bar = 3 mm (A, C), 40 μm (B), 10 μm (insert of B), 50 μm (D). (Color images can be found online at www.liebertpub.com/jon)

H&E-stained sections from the sham lesion cortex (Fig. 4B-1), and cortex from BMSCs (Fig. 4B-2) and PMSCs (Fig. 4B-3) groups indicated more neuron preservation and fewer small, round, and extensively stained cells were present in the cell infusion groups. These cells are apparently inflammatory cells, but their precise nature was not determined.

Identification and Characterization of Donor Cells In Vivo

LacZ-transfected BMSCs and PMSCs that had been i.v. administered (1.0 × 106 cells) at 6 h after MCAO were identified in vivo. Transduction efficiency of the LacZ gene with the present protocol was over 90% in vitro. The LacZ-expressing MSCs were found primarily in the lesion. The transmitted light images in the LacZ-transfected BMSCs and PMSCs are shown in Figures 4C-2 and 4C-3, respectively. Note the abundance of LacZ-positive blue-cellular-like elements in and around the lesion, indicating that systemic deliver of both types of cells reached the lesion site. There was a paucity of blue staining in the non-treated group (Fig. 4C-1). Immunohistochemical studies were carried out to identify LacZ-positive cells in and around the lesion zone in animals transplanted with LacZ-transfected MSCs. The microphotographs of BMSCs (Fig. 4D-2) and PMSCs (Fig. 4D-3) demonstrated a large number of LacZ-positive cells in the lesion. The numbers of LacZ-positive cells were obtained from one section per rat, and five separated rats (n = 5) were analyzed, demonstrating a large number of LacZ-positive cells (300 ± 30 cells/mm3, n = 5) in the penumbra lesion in PMSC-treated rats, which were very similar to those (29 ± 77 cells/mm3, n = 5) in the BMSC-treated rats, although there was virtually no LacZ-positive cells in the non-treated group (Fig. 4D-1).

The density of LacZ-positive cells estimated from the immunohistochemical analysis was about 300 cells/mm3 in the lesion. Transduction efficiency of Lac-Z gene was about 90%. Infarcted volume was about 200 mm3. The number of intravenously injected cells was 106 cells. Thus, the percentage of intravenously injected cells accumulating in the lesion was about 6.7%.

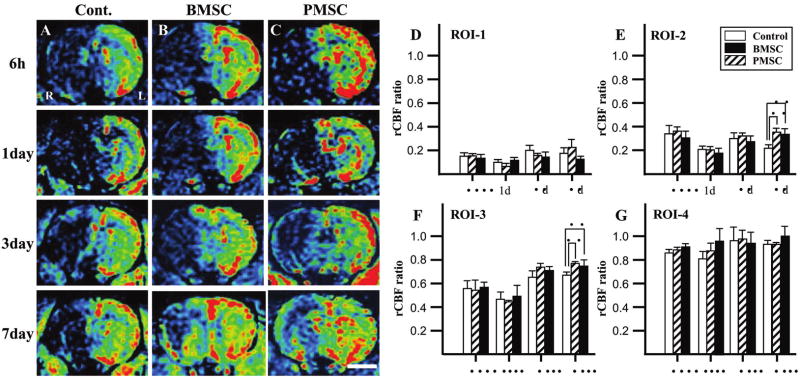

Dynamic Susceptibility Contrast-Enhanced PWI

The PWI-derived parameter maps to assess rCBF allowed further quantitative analysis for the hemodynamic changes of the lesions. Figure 6A–C shows images obtained at 6 h (row 1), 1 day (row 2), 3 days (row 3), and 7 days (row 4). Control, and BMSC- and PMSC-injected groups are in columns A, B, and C, respectively.

FIG. 6.

Evaluation of hemodynamic state (rCBF maps) with perfusion-weighted images (PWI). BMSCs or PMSCs were intravenously injected immediately after the initial MRI scanning (6 h after MCAO). Images obtained 6 h, and 1, 3, and 7 days after MCAO in medium-injected (A), BMSC-treated (B), and PMSC-treated group (C). Summary of rCBF evaluated with PWI in each group: ROI-1 (D), ROI-2 (E), ROI-3 (F), and ROI-4 (G). rCBF ratio (ischemic lesion/contralateral lesion) at 6 h, and 1, 3, and 7 days after MCAO is summarized in D–G. Scale bar = 3 mm. *p < 0.05.

The four ROI for the analysis are shown in Figure 5. The severity of the lesion was greatest in ROI-1, and progressively less in ROI-2 through ROI-4. A rCBF ratio was calculated at each ROI from PWI obtained in the infarction hemisphere divided by that of the non-infarcted hemisphere. In ROI-1, the rCBF ratio of control, BMSC-treated, and PMSC-treated groups was similar and decreased to less than 20% at 6-h post-MCAO, and remained low at 3 and 7 days (Fig. 6D). The rCBF ratio in ROI-2 of the three groups was similar at 6 h, and 1 and 3 days post-MCAO. However, the rCBF ratio of both BMSC-treated and PMSC-treated groups was increased at 7 days after MCAO as compared to control (Fig. 6E). The rCBF ratio in ROI-3 was similar for the three groups at 6 h, and 1 and 3 days, but again the MSC groups had a greater rCBF ratio at 7 days (Fig. 6F). In ROI-4, the rCBF ratio slightly decreased in all groups at all time points, but not more than 20% (Fig. 6G).

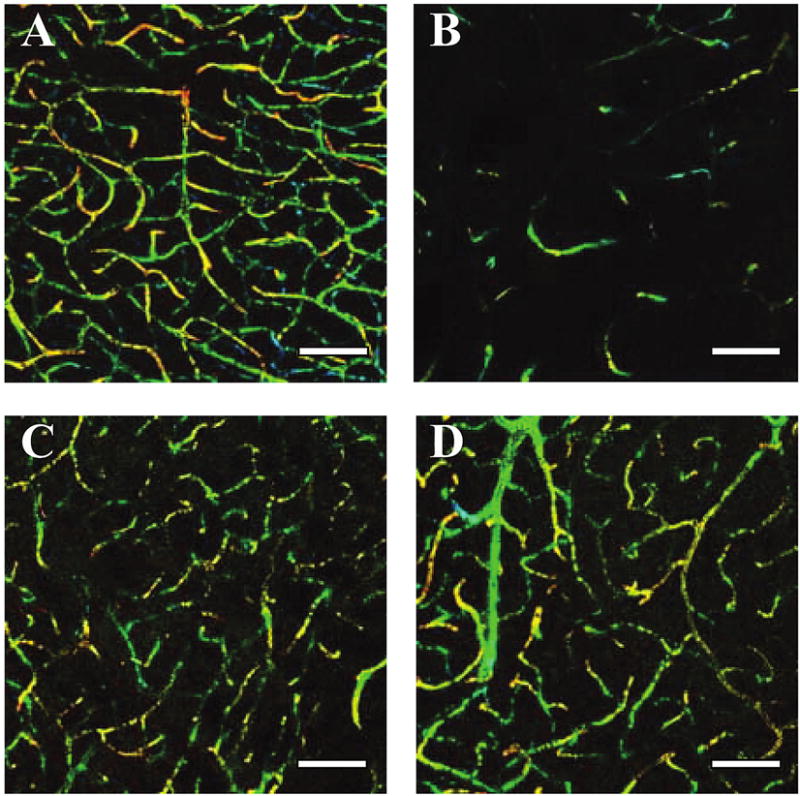

Analysis of Capillary in Confocal Images

To examine whether the administration of BMSCs and PMSCs induces angiogenesis, three-dimensional analysis of capillary vessels in the lesion was performed using Zeiss LSM5 PASCAL software. Figure 7A shows the three-dimensional capillary image in the normal rat brain. The capillary vascular volume in ROI-3 at 7 days after MCAO was increased in both BMSC-treated (Fig. 7C) and PMSC-treated groups (Fig. 7D) compared to the medium-treated group (Fig. 7B). The capillary vascular volume was expressed as a ratio by dividing that obtained from the ischemic hemisphere by that of the contralateral control hemisphere. The ratio was significantly higher in both the BMSC-treated (0.62 ± 0.05, n = 5; p < 0.05) and the PMSC-treated (0.61 ± 0.05, n = 5; p < 0.05) groups as compared to the medium-treated group (0.30 ± 0.02, n = 5).

FIG. 7.

Seven days after MCAO, the angiogenesis in boundary zone was analyzed using a three-dimensional analysis system. (A) Three-dimensional capillary image with systemically perfused FITC-dextran in the normal rat brain. The total volume of the microvessels in the sampled lesion site decreased 7 days after MCAO (B), but was greater in the BMSC-treated group (C) and the PMSC-treated group (D). Scale bar = 100 μm.

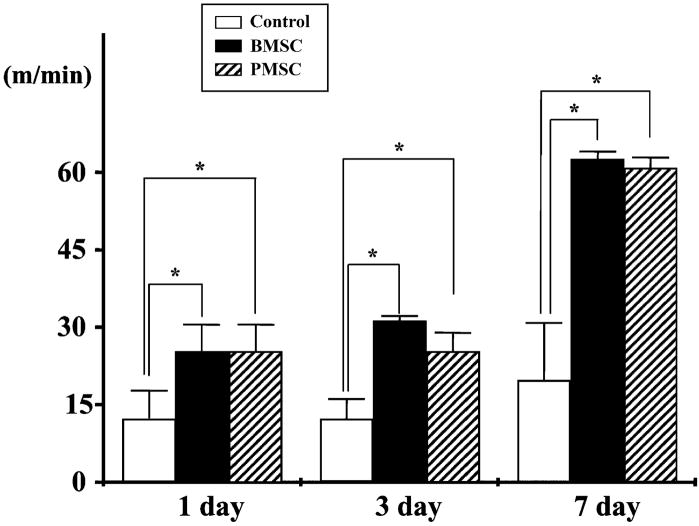

Functional Analysis

To access behavioral performance in the lesioned and transplanted animals, the treadmill stress test was used (Fig. 8). Behavioral testing began 24 h after lesion induction alone or with cell transplantation. In the treadmill stress test, control animals (no lesion) reach a maximum treadmill velocity of about 70 m/min.2 At 24 h after MCAO without transplantation, maximum velocity on the treadmill test was 10.0 ± 6.54 m/min (n = 5). Non-treated animals showed increased treadmill velocity with slow improvement up to 7 days (20.8 ± 10.9 m/min, n = 5). In both BMSCs and PMSCs transplantation groups, the improvement in velocity was greater over the time course up to 7 days.

FIG. 8.

The treadmill stress test demonstrated that the maximum speed at which the rats could run on motor-driven treadmill was faster in the BMSCs and PMSCs rats than control. Velocity is plotted for three times after MCAO induction.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that intravenous infusion of MSCs, derived from either bone marrow or peripheral blood, at 6 h after permanent MCAO in the rat results in reduction in infarction volume, improvement in cerebral blood flow, induction of angiogenesis, MSC accumulation in the ischemic brain, and improvement in behavioral performance. These results are consistent with previous studies showing beneficial effects of BMSCs on cerebral infarction (Chen et al., 2001; Horita et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2006; Nomura et al., 2005), but additionally demonstrate that MSCs derived from peripheral blood show similar efficacy.

A characteristic feature of the BMSCs derived from rat bone marrow in this study is a CD45−, CD73+, CD90+, CD106− cell surface phenotype, which is consistent with previous studies (Rochefort et al., 2005). PM-SCs derived from peripheral blood expressed a similar pattern of cell surface antigens and cellular morphology (flattened and spindle-shaped adherent cells) in culture, suggesting similarity of the two cell populations.

Precursors that fulfilled criteria for mesenchymal stem cells are present in the peripheral blood of humans (Villaron et al., 2004; Zvaifler et al., 2000) and dogs (Huss et al., 2000) can be mobilized by granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) (Tondreau et al., 2005). Intravenous injection of G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood mononuclear cells in rat MCAO models, resulting in therapeutic benefits (Willing et al., 2003). These results are consistent with our observations that PMSCs derived from peripheral blood, expanded in culture and intravenously infused contributed to the therapeutic benefits in the rat MCAO model. While G-CSF showed some beneficial effects (Willing et al., 2003), the relatively large effect we observed may have resulted from the administration of a large number of isolated and cultured MSCs.

The mechanisms of therapeutic benefits of MSCs transplantation for stroke, which are not completely understood, may result from neuroprotection and angiogenesis (Chen et al., 2001; Horita et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2006; Nomura et al., 2005). A number of neurotrophic factors have been reported to have therapeutic effects on cerebral infarction (Hirouchi and Ukai, 2002). These include BDNF, GDNF, NGF, EGF, and bFGF (Chen et al., 2002; Kurozumi et al., 2004). Mechanisms proposed for the neuroprotective effect of these agents include anti-apoptotic activity, free radical scavenging, anti-inflammatory activity, and anti-glutamate excitotoxicity (Hirouchi and Ukai, 2002). Recent reports using olfactory ensheathing cell (OEC) transplantation in the injured spinal cord demonstrate that OECs may confer a neuro-protective effect on corticospinal tract neurons projecting through the injured spinal cord (Sasaki et al., 2006). Indeed, beneficial effects of cell transplantation of a variety of cell types may operate through common mechanisms. Transplanted cells may provide neurotrophic support for endogenous cell survival (Kurozumi et al., 2004), but additionally may contribute to neural repair by, for example, remyelination (Akiyama et al., 2001; Honmou et al., 1996; Inoue et al., 2003; Kato et al., 2000; Keirstead et al., 1999; Oka et al., 2004; Pluchino et al., 2005; Sasaki et al., 2001).

An advantage of BMSCs and PMSCs for transplantation studies is that they can be easily and safely obtained in large numbers from autologous bone marrow aspirates or blood. The prospect that intravenous delivery of these cells could lead to a global neuroprotection with subsequent repair such as remyelination is intriguing and should be further explored.

MSCs also provide several angiogenic growth factors such as VEGF and bFGF (Hamano et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2006), which may prevent endothelial cells from ischemic damage or stimulate angiogenesis. These cells produce soluble mediators that down-regulate immune responses that could also contribute to neuroprotection (Bernstein and Shearer, 1988). In the present study, hemodynamic changes of cerebral blood flow after MCAO with and without MSCs transplantation were analyzed by PWI. While both control and MSCs transplantation groups showed improvement of rCBF in the lesion, recovery of rCBF was greater in the MSC transplantation groups than control groups. Moreover, histological examination of capillary vessels in ischemic lesion indicated that MSCs transplantation group showed greater angiogenesis. These data suggest that the improvement of cerebral blood perfusion plays an important role in the mechanism of therapeutic effects of MSC transplantation.

Cell-based therapeutic approaches are being used in clinical studies for a number of neurological diseases, including Krabbe’s disease (Escolar et al., 2005), Hurler’s syndrome (Staba et al., 2004), metachromatic leukodystrophy (Koc et al., 2002), and stroke (Bang et al., 2005). Improved neurological function in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) has been reported following intravenous infusion of human MSCs and neurosphere-derived multipotent precursors (Pluchino et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2005). Suggested mechanisms include reduction of inflammatory infiltration, remyelination, and elevation of trophic factors that may be neuroprotective or stimulate oligodendrogliosis. A systemically delivered cell-based therapy may have the advantage of exerting multiple therapeutic effects at various sites and times within the lesion as the cells respond to a particular pathological microenvironment. PMSCs or their precursors exist in peripheral blood in normal individuals and proliferate in culture (Zvaifler et al., 2000), which suggests the prospect of future use of PMSC for clinical studies in stroke. Thus, autologous peripheral blood might provide an important source of stem/precursor cells for clinical use.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture (16390414, 16591450, 16659393), JST (Japan Science and Technology Corporation) Innovation Plaza Hokkaido Project, Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance Welfare Foundation, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (RG2135; CA1009A10), the National Institutes of Health (NS43432), and the Medical and Rehabilitation and Development Research Services of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- AKIYAMA Y, HONMOU O, KATO T, UEDE T, HASHI K, KOCSIS JD. Transplantation of clonal neural precursor cells derived from adult human brain establishes functional peripheral myelin in the rat spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 2001;167:27–39. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BANG OY, LEE JS, LEE PH, LEE G. Autologous mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in stroke patients. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:874–882. doi: 10.1002/ana.20501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEDERSON JB, PITTS LH, GERMANO SM, NISHIMURA MC, DAVIS RL, BARTKOWSK HM. Evaluation of 2,3,5–triphenyltetrazolium chloride as a stain for detection and quantification of experimental cerebral infarction in rats. Stroke. 1986;17:1304–1308. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.6.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERNSTEIN DC, SHEARER GM. Suppression of human cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses by adherent peripheral blood leukocytes. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1988;532:207–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb36339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN J, LI Y, WANG L, et al. Therapeutic benefit of intracerebral transplantation of bone marrow stromal cells after cerebral ischemia in rats. J Neurol Sci. 2001;189:49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00557-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN X, LI Y, WANG L, et al. Ischemic rat brain extracts induce human marrow stromal cell growth factor production. Neuropathology. 2002;22:275–279. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2002.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOPP M, ZHANG XH, LI Y, et al. Spinal cord injury in rat: treatment with bone marrow stromal cell transplantation. Neuroreport. 2000;11:3001–3005. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200009110-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESCOLAR ME, POE MD, PROVENZALE JM, et al. Transplantation of umbilical-cord blood in babies with infantile Krabbe’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2069–2081. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMANO K, LI TS, KOBAYASHI T, KOBAYASHI S, MATSUZAKI M, ESATO K. Angiogenesis induced by the implantation of self-bone marrow cells: a new material for therapeutic angiogenesis. Cell Transplant. 2000;9:439–443. doi: 10.1177/096368970000900315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIROUCHI M, UKAI Y. Current state on development of neuroprotective agents for cerebral ischemia. Nippon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 2002;120:81–90. doi: 10.1254/fpj.120.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HONMA T, HONMOU O, IIHOSHI S, et al. Intravenous infusion of immortalized human mesenchymal stem cells protects against injury in a cerebral ischemia model in adult rat. Exp Neurol. 2006;199:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HONMOU O, FELTS PA, WAXMAN SG, KOCSIS JD. Restoration of normal conduction properties in demyelinated spinal cord axons in the adult rat by transplantation of exogenous Schwann cells. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3199–3208. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03199.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HORITA Y, HONMOU O, HARADA K, HOUKIN K, HAMADA H, KOCSIS JD. Intravenous administration of GDNF gene-modified human mesenchymal stem cells protects against injury in a cerebral ischemia model in adult rat. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84:1495–1504. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUSS R, CLAUDIA L, WEISSINGER EM, KOLB HJ, THALMEILER K. Evidence of peripheral blood-derived, plastic-adherent CD34−/low hematopoietics stem cell clones with mesenchymal stem cell characteristics. Stem Cells. 2000;18:252–260. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.18-4-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IIHOSHI S, HONMOU O, HOUKIN K, HASHI K, KOCSIS DJ. A therapeutic window for intravenous administration of autologous bone marrow after cerebral ischemia in adult rats. Brain Res. 2004;1007:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.09.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INOUE M, HONMOU O, OKA S, HOUKIN K, HASHI K, KOCSIS JD. Comparative analysis of remyelinating potential of focal and intravenous administration of autologous bone marrow cells into the rat demyelinated spinal cord. Glia. 2003;44:111–118. doi: 10.1002/glia.10285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATO T, HONMOU O, UEDE T, HASHI K, KOCSIS JD. Transplantation of human olfactory ensheathing cells elicits remyelination of demyelinated rat spinal cord. Glia. 2000;30:209–218. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(200005)30:3<209::aid-glia1>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEIRSTEAD HS, BEN-HUR T, ROGISTER B, O’LEARY MT, DUBOIS-DALCQ M, BLAKEMORE WF. Polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule-positive CNS precursors generate both oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells to remyelinate the CNS after transplantation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7529–7536. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07529.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOBUNE M, KAWANO Y, ITO Y, et al. Telomerized human multipotent mesenchymal cells can differentiate into hematopoietic and cobblestone area-supporting cells. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:715–722. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOC ON, DAY J, NIEDER M, GERSON SL, LAZARUS HM, KRIVIT W. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell infusion for treatment of metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) and Hurler syndrome(MPS-IH. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;30:215–222. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUROZUMI K, NAKAMURA K, TAMIYA T, et al. BDNF gene-modified mesenchymal stem cells promote functional recovery and reduce infarct size in the rat middle cerebral artery occlusion model. Mol Ther. 2004;9:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU H, HONMOU O, HARADA K, et al. Neuroprotection by PlGF gene–modified human mesenchymal stem cells after cerebral ischemia. Brain. 2006;129:2734–2745. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LONGA EZ, WEINSTEIN PR, CARLSON S, CUMMIN R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20:84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAGAWA I, MURAKAMI M, IJIMA K, et al. Persistent and secondary adenovirus-mediated hepatic gene expression using adenovirus vector containing CTLA4IgG. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:1739–1745. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.12-1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAMURA Y, WAKIMOTO H, ABE J, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy with murine tumor-specific T lymphocytes engineered to secrete interleukin 2. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5757–5760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEUMANN-HAEFELIN T, KASTRUP A, DE CRESPIGNY A, et al. Serial MRI after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats: dynamics of tissue injury, blood–brain barrier damage, and edema formation. Stroke. 2000;31:1965–1972. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.8.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOMURA T, HONMOU O, HARADA K, HOUKIN K, KOCSIS JD. Intravenous infusion of BDNF gene–modified human mesenchymal stem cells protects against injury in a cerebral ischemia model in adult rat. Neuroscience. 2005;136:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKA S, HONMOU O, AKIYAMA Y, et al. Autologous transplantation of expanded neural precursor cells into the demyelinated monkey spinal cord. Brain Res. 2004;1030:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PLUCHINO S, QUATTRINI A, BRAMBILLA E, et al. Injection of adult neurospheres induces recovery in a chronic model of multiple sclerosis. Nature. 2003;422:688–694. doi: 10.1038/nature01552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PLUCHINO S, ZANOTTI L, ROSSI B, et al. Neurosphere-derived multipotent precursors promote neuroprotection by an immunomodulatory mechanism. Nature. 2005;436:266–271. doi: 10.1038/nature03889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PROCKOP DJ, GREGORY CA, SPEES JL. One strategy for cell and gene therapy: harnessing the power of adult stem cells to repair tissues. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11917–11923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834138100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PROCKOP DJ. Marrow stromal cells as stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissues. Science. 1997;276:71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROCHEFORT GY, VAUDIN P, BONNET N, et al. Influence of hypoxia on the domiciliation of mesenchymal stem cells after infusion into rats: possibilities of targeting pulmonary artery remodeling via cells therapies? Respir Res. 2005;6:125. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SASAKI M, HAINS BC, LANKFORD KL, WAXMAN SG, KOCSIS JD. Protection of corticospinal tract neurons after dorsal spinal cord transection and engraftment of olfactory ensheathing cells. Glia. 2006;53:352–359. doi: 10.1002/glia.20285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SASAKI M, HONMOU O, AKIYAMA Y, UEDE T, HASHI K, KOCSIS DJ. Transplantation of an acutely isolated bone marrow fraction repairs demyelinated adult rat spinal cord axons. Glia. 2001;35:26–34. doi: 10.1002/glia.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STABA SL, ESCOLAR ML, POE M, et al. Cord–blood transplants from unrelated donors in patients with Hurler’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1960–1969. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKIGUCHI M, MURAKAMI M, NAKAGAWA I, SAITO I, HASHIMOTO A, UEDE T. CTLA4IgG gene delivery prevents autoantibody production and lupus nephritis in MRL/lpr mice. Life Sci. 2000;66:991–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00664-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TONDREAU T, MEULEMAN N, DELFORGE A, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from CD133-positive cells in mobilized peripheral blood and cord blood: proliferation, Oct4 expression, and plasticity. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1105–1112. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VILLARON EM, ALMEID AJ, LOPEZ-HOLGADO N, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells are present in peripheral blood and can engraft after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2004;89:1421–1427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLING AE, VENDRAME M, MALLERY J, et al. Mobilized peripheral blood cells administered intravenously produce functional recovery in stroke. Cell Transplant. 2003;12:449–454. doi: 10.3727/000000003108746885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOODBURY D, SCHWARZ EJ, PROCKOP DJ, BLACK IB. Adult rat and human bone marrow stromal cells differentiate into neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:364–370. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000815)61:4<364::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG J, LI Y, CUY Y, et al. Human bone marrow stromal cell treatment improves neurological functional recovery in EAE mice. Exp Neurol. 2005;195:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZVAIFLER JN, MARINOVA-MUTAFCHIEVA L, ADAMS G, et al. Mesenchymal precursor cells in the blood of normal individuals. Arthritis Res. 2000;2:477–488. doi: 10.1186/ar130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]