Abstract

The PRH (proline-rich homeodomain) [also known as Hex (haematopoietically expressed homeobox)] protein is a transcription factor that functions as an important regulator of vertebrate development and many other processes in the adult including haematopoiesis. The Groucho/TLE (transducin-like enhancer) family of co-repressor proteins also regulate development and modulate the activity of many DNA-binding transcription factors during a range of diverse cellular processes including haematopoiesis. We have shown previously that PRH is a repressor of transcription in haematopoietic cells and that an Eh-1 (Engrailed homology) motif present within the N-terminal transcription repression domain of PRH mediates binding to Groucho/TLE proteins and enables co-repression. In the present study we demonstrate that PRH regulates the nuclear retention of TLE proteins during cellular fractionation. We show that transcriptional repression and the nuclear retention of TLE proteins requires PRH to bind to both TLE and DNA. In addition, we characterize a trans-dominant-negative PRH protein that inhibits wild-type PRH activity by sequestering TLE proteins to specific subnuclear domains. These results demonstrate that transcriptional repression by PRH is dependent on TLE availability and suggest that subnuclear localization of TLE plays an important role in transcriptional repression by PRH.

Keywords: co-repressor, Groucho, haematopoiesis, haematopoietically expressed homeobox (Hex), nuclear retention, proline-rich homeodomain (PRH), transcriptional repression, trans- dominant negative, transducin-like enhancer (TLE)

Abbreviations: CIP, calf intestinal phosphatase; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DTT, dithiothreitol; Eh-1, Engrailed homology motif; eIF-4E, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility-shift assay; GFP, green fluorescent protein; Hex, haematopoietically expressed homeobox; PML, promyelocytic leukaemic; PRH, proline-rich homeodomain; pTK, thymidine kinase promoter; TLE, transducin-like enhancer; TRITC, tetramethylrhodamine β-isothiocyanate

INTRODUCTION

Transcription factors that bind to DNA are important regulators of multiple processes in the cell and often act in conjunction with non-DNA-binding co-repressors and co-activators to bring about changes in gene expression. Generally the role of the co-regulatory proteins is to recruit chromatin remodelling enzymes or chromatin-binding proteins in order to set up more open or closed chromatin configurations. Most co-activators and co-repressors are able to interact with a variety of DNA-bound factors to regulate gene expression. The PRH (proline-rich homeodomain) [also known as Hex (haematopoietically expressed homeobox)] protein is a DNA-binding transcription factor that can regulate gene expression in a number of tissues using multiple mechanisms (reviewed in [1]). PRH forms oligomers in cells and can bind to DNA in the oligomeric state [2]. When bound to DNA, PRH generally functions as a repressor of transcription [3–6] and we have shown previously that PRH can recruit members of the Groucho/TLE (transducin-like enhancer) family of co-repressor proteins [7]; however, in some contexts, PRH functions as a DNA-bound activator of transcription [8]. PRH can also regulate transcription without binding to DNA by regulating the activity of other DNA-binding transcription factors [9–11]. In addition, PRH can regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally by regulating the transport of specific mRNAs from the nucleus to the cytoplasm [12].

PRH regulates embryonic development in all vertebrates and is necessary for the development of embryonic forebrain, thyroid, lungs, liver and heart [13–15]. PRH also plays a role in the early development of vascular tissues and the formation of haematopoietic lineages [13,16–20]. In the adult, PRH is expressed in thyroid, liver and lungs [21] and may play a role in the maintenance of differentiation of these tissues. Moreover this protein regulates haematopoiesis in the embryo and in the adult [13,22]. PRH is strongly expressed in pluripotent haematopoietic progenitors, in erythromyeloid and B-cell progenitors, but not in T-cell lineages [20,23–25]. In general, the gradual down-regulation of PRH is associated with differentiation of most haematopoietic lineages [24,26]. PRH interacts with the growth control proteins PML (promyelocytic leukaemic) and translation initiation factor eIF-4E (eukaryotic initiation factor 4E) [27], and has been shown to regulate cell growth or differentiation in haematopoietic cells as well as in a number of different tissues [16,28,29]. Decreased PRH expression and loss of nuclear localization of PRH is implicated in a number of human myeloid leukaemias [30,31]. In addition, a chromosomal translocation resulting in a PRH fusion protein that can activate transcription and has trans-dominant-negative activity over wild-type PRH has been shown to be a causative agent in acute myeloid leukaemia [32].

The PRH protein consists of three regions: a proline-rich N-terminal domain, a central homeodomain and an acidic C-terminal domain. The proline-rich N-terminal domain of PRH can make multiple protein–protein interactions and binds to several proteins including PML [27], eIF-4E [12], proteosome subunit HC8 [33] and members of the Groucho/TLE [7] family of co-repressor proteins. PRH forms foci in haematopoietic cells and exists as oligomeric complexes in vivo and in vitro [2]. The N-terminal domain of PRH is required for oligomerization and transcriptional repression and can influence the DNA-binding activity of the PRH homeodomain [2,34]. As well as binding to DNA [6], the PRH homeodomain is important in PRH oligomerization [2] and forms protein–protein interactions with other transcription factors [11]. The C-terminal domain of PRH is rich in acidic residues but appears to play no role in repression [6]; however, both the homeodomain and C-terminal domain are reported to play a role in transcription activation by PRH [35].

The TLE proteins are members of a family of transcription co-repressors that includes the archetypical Drosophila protein Groucho. Like PRH, Groucho/TLE family proteins are involved in many developmental decisions including: neuronal and epithelial cell differentiation, segmentation and sex determination, and the differentiation of haematopoietic, osteoblast and pituitary cells [36–40]. Members of the Groucho/TLE family do not have DNA-binding activity, but are instead recruited to DNA by interactions with DNA-binding proteins. Once recruited to a promoter, these proteins can bring about long-range transcriptional repression by recruiting histone deacetylases [41–43] and by interacting directly with histones [44]. TLE proteins form tetramers and larger oligomeric complexes and oligomerization is essential for co-repression [45,46]. The TLE proteins are phosphoproteins and are hyperphosphorylated during the cell cycle and during cell differentiation [45,47,48]. A subset of the DNA-binding transcription factors that interact with Groucho/TLE proteins in the haematopoietic compartment, including Hes1, Runx-1 and Pax5, have been shown to play a role in regulating TLE phosphorylation and modulating its activity [49,50]. For example, Hes1- and Runx-1-dependent phosphorylation of nuclear TLE1 by CK2 (casein kinase 2) has been shown to increase its co-repressor activity and its association with chromatin [49]. In contrast, phosphorylation of TLE by HIPK2 (homeodomain interacting protein kinase 2) decreases its co-repression ability [51].

We have shown previously that endogenous PRH and TLE are present in both the cytoplasmic and the nuclear compartments of K562 cells [7]. We have also shown that a short sequence of amino acids in the PRH N-terminal domain, known as the Eh-1 (Engrailed homology) motif, mediates the binding of PRH to TLE proteins. Moreover we have demonstrated that a direct interaction between TLE1 and PRH is required for co-repression of transcription [7]. In the present study, we demonstrate that PRH brings about nuclear retention of endogenous TLE proteins in early myeloid progenitors (K562 cells). Furthermore we show that a mutated form of PRH that is defective in DNA binding can function as a trans-dominant negative of wild-type PRH by sequestering TLE proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL

Mammalian expression and reporter plasmids

The mammalian expression plasmid pMUG1-Myc–PRH expresses Myc-tagged human PRH (amino acids 7–270). pMUG1-Myc–PRH and pMUG1-Myc–PRHF32E have been described previously [7]. A QuikChange® kit (Stratagene) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol for the mutagenesis of pMUG1-Myc–PRH to produce pMUG1-Myc–PRH R188A, R189A and pMUG1-Myc–PRH N187A, and for the mutagenesis of pMUG1-Myc–PRH F32E to produce pMUG1-Myc–PRH F32E/R188A, R189A and pMUG1-Myc–PRH F32E/N187A. The resulting mutants were fully sequenced to confirm the sequence change. pcDNA3-Myc–PRH-HD 130–198 was created by cloning a BamHI-EcoRI fragment encoding the PRH homeodomain (amino acids 130–198 followed by an in-frame stop) into the pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen). The fragment was generated using PCR and a 5′ primer that contains the Myc epitope (the Myc tag is underlined): the 5′ primer is 5′-CGGGAATCCATGGAACAAAAACTCATCTCAGAAGAGGATCTGTTGCAGAGGCCTCTGCATAAAAGG-3′ and the 3′ primer is 5′-AGAGAATTCCTACTCCTGTTTTAGTCTCCTCCA-3′. The GFP (green fluorescent protein)–PRH plasmid was constructed by inserting the PRH cDNA from a BlueScipt clone into the EcoRI and KpnI sites of eGFPc1 (Clontech).

The pTK (thymidine kinase promoter)–PRH reporter plasmid has been described previously [6]. The pSV-β-galactosidase control vector (pSV-lacZ) was obtained from Promega. The mammalian expression plasmid pCMV2-FLAG–TLE1 contains the TLE1 coding sequence in-frame with the FLAG epitope [7].

Bacterial expression plasmids

The plasmid pTrcHisA-hPRH expresses recombinant full-length histidine-tagged and Myc-tagged human PRH7–270 in bacteria and has been described previously [2]. pTrcHisA-PRH-hHD expresses a histidine-tagged truncated PRH construct consisting of the human PRH homeodomain. This construct was generated by cloning a PCR fragment carrying the PRH human homeodomain (amino acids 130–198 followed by an in-frame stop) between the XhoI and EcoRI sites of pTrcHisA using the primers 5′-AGACTCGAGTTGCAGAGGCCTCTGCATAAAAGG-3′ and 5′-AGAGAATTCCTACTCCTGTTTTAGTCTCCTCCA-3′ (the restriction sites are underlined). The expression plasmids pTrcHisA-Myc–PRHF32E, pTrcHisA-Myc–PRH R188A,R189A, pTrcHisA-Myc–PRH N187A, pTrcHisA-Myc–PRH F32E/R188A,R189A and pTrcHisA-Myc–PRH F32E/N187A were created by cloning BamHI-EcoRI fragments encoding the mutated human PRH cDNAs from the corresponding pMUG1 series of plasmids (described above) into pTrcHisA.

Expression and purification of tagged-PRH proteins

The His–PRH fusion proteins were expressed in BL21 pLysS cells (Novagen). Fusion protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside). Cells were harvested after 4 h at 37 °C, resuspended in lysis buffer [100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 5 μg/ml DNase and 10 μg/ml RNase) and lysed by the addition of 100 μl of lysozyme (1 mg/ml) for 20 min, followed by four bursts of sonication at 60% amplitude. After centrifugation for 30 min at 39000 g in ss34 rotor (Sorval RC-3B) the His–PRH fusion proteins contained in the supernatant were purified over a HiTrap chelating column charged with nickel ions (1 ml, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) using an ÄKTA FPLC system and UNICORN 3.10 software. Proteins were eluted with a 250 mM imidazole buffer. Aliquots of these proteins were assayed for purity by SDS/PAGE followed by staining with Coomassie Blue. Proteins were quantified using the Bio-Rad phosphoric acid protein assay and were stored at −80 °C after dialysis into PBS containing 20% glycerol.

EMSA (electrophoretic mobility-shift assay)

A double-stranded oligonucleotide carrying a PRH-binding site was produced by heating the complementary single-stranded oligonucleotides shown below at 90 °C for 1 min and then slow cooling to 20 °C: 5′-GCTTCTGGGAAGCAATTAAAAAATGGCTCGAGCT-3′ and 3′-AGACCCTTCGTTAATTTTTTACCGAGC-5′.

This oligonucleotide (400 ng) was labelled with [α-32P]dATP using Klenow enzyme at 30 °C for 30 min. Unincorporated [α-32P]-dATP was then removed using a Micro Bio-Spin 6 column (Bio-Rad). The labelled oligonucleotide (100 pM) was incubated with purified His-tagged proteins in 20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT (dithiothreitol), 80 ng/ml poly(dI-dC)·(dI-dC), 0.5 mg/ml BSA and 10% glycerol at 4 °C for 30 min. Free and bound DNA was then separated on 6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels run in 0.5×TBE (1×TBE=45 mM Tris/borate and 1 mM EDTA) and quantified using a PhosphoImager with Molecular Dynamics ImageQuant software (version 3.3). All experiments were repeated three times.

Cell culture and transfection assays

K562 cells were maintained in DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) supplemented with 10% FCS (foetal calf serum), 100 units/ml penicillin and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2, 20% O2 and 80% N2. For transient-transfection assays, cells were transferred to 0.4 cm electroporation cuvettes at a density of 1×107 cells in 200 μl of medium. The cells and 5 μg of the luciferase reporter plasmid and 5 μg of the β-galactosidase reporter plasmid were mixed by pipetting and were electroporated at 250 V, 975 μF. In repression experiments, the cells were co-transfected with either pMUG1 vector or the pMUG1-Myc–PRH series of plasmids as detailed in the Results section below. Electroporated cells were incubated for 24 h as described above. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation [1800 g for 5 min at room temperature (24 °C)] and the luciferase activity was assayed using the Promega Luciferase Assay System according to the manufacturer's protocol. A β-galactosidase assay was performed as an internal control for transfection efficiency: 40 μl of cell lysate was mixed with 900 μl of Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4 and 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) and 200 μl of ONPG (o-nitrophenyl β-D-galactopyranoside; 4 mg/ml) and incubated at 37 °C for at 1 h. The reaction was stopped by adding 200 μl of 1 M Na2CO3 and the absorbance was measured at 420 nm. After subtraction of the background, the luciferase counts were normalized against the β-galactosidase value.

Whole-cell extracts and cell fractionation

Whole-cell extracts from 2×107 K562 cells were made as follows. The cell pellet was collected by centrifugation for 5 min at 1800 g in a Centurion bench-top centrifuge. The cell pellet was washed twice in PBS and then resuspended in 400 μl of lysis buffer [150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 0.1% SDS and 0.1% Nonidet P40]. The cell suspension was drawn up and down six times through a 3×Monojet needle (1.1 mm×50 mm, 19G×2′), incubated on ice for 20 min, and then centrifuged at maximum speed for 15 min at 4 °C in a microcentrifuge.

Nuclear and post-nuclear extracts were made as follows: 2×107 K562 cells were centrifuged at 1800 g in a Centurion bench-top centrifuge (IEC Centra 4B) and the pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of buffer [20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM DTT containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)] at 4 °C for 10 min. Then, 15 μl of 10% (v/v) Nonidet P40 was added to the lysate and mixed by vortexing. The lysate was centrifuged for 1 min at 16000 g in a microcentrifuge and the supernatant was removed and stored at −80 °C as the soluble post-nuclear fraction. The nuclei in the pellet were resuspended in 200 μl of 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) Nonidet P40 and 0.1% SDS, containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) for 20 min at 4 °C and then centrifuged for 1 min at 16000 g at 4 °C in a microcentrifuge. The supernatant was removed and stored at −80 °C as the soluble nuclear extract.

Phosphatase experiments

CIP (calf intestinal phosphatase) and CIP buffer was obtained from (Fermentas). K562 nuclear extracts prepared from cells expressing Myc–PRH were incubated with a cocktail of phosphatase inhibitors in CIP buffer for 30 min at 4 °C or 37 °C. The phosphatase inhibitor cocktail contained 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM sodium β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM EDTA and 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate). CIP (1 or 2 μl) was added to nuclear extracts either containing phosphatase inhibitors or without phosphatase inhibitors for 30 min at 37 °C.

Co-immunopreciptitation assays

K562 cells (2×107) were co-transfected with pCMV2-FLAG–TLE1 and either pMUG1-Myc-PRH or one of the pMUG1-Myc–PRH derivatives as described above. Whole-cell extracts were prepared by resuspending the cell pellet into 150 μl of lysis buffer [50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8), 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM NaF, 10 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM DTT, 1% (v/v) Triton and 10% glycerol] for 30 min at 4 °C. An equivalent volume of binding buffer [50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8), 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 0.2% Nonidet P40, 0.1% BSA and 2.5% glycerol] was added to the lysate before incubation with a monoclonal anti-Myc9E10 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h at 4 °C under agitation. Protein G beads (Sigma) were then washed with the binding buffer and incubated with the extracts for a further 2 h at 4 °C. After this time, the beads were collected by centrifugation in an Eppendorf microcentrifuge (16000 g for 1 min), washed three times in 1 ml of buffer [50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8), 200 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT and 0.5% Nonidet P40], and then resuspended in SDS-loading buffer. All operations were carried out at 4 °C and in the presence of protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). After SDS/PAGE, the proteins were immunoblotted on to Immobilon-P membrane, and tagged TLE1 and PRH were detected using an anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) and anti-Myc9E10 antibody respectively.

Western blot analysis

Post-nuclear and nuclear fractions were collected as described above and separated by SDS/PAGE. Immunoblot analyses were performed using appropriate antibodies to detect endogenous PRH (mouse polyclonal antibody, [6,26]), Myc-tagged PRH (mouse anti-Myc9E10 antibody), endogenous TLE proteins (pan-TLE goat polyclonal sc13373; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), FLAG-tagged TLE1 (rabbit anti-FLAG polyclonal antibody; Sigma), HC8 (mouse monoclonal antibody; Affiniti), tubulin (mouse monoclonal MS-581-P1; NeoMarkers) and lamin A/C (rabbit polyclonal sc-20688; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Immunofluorescence

K562 cells were adhered to coverslips coated with poly-lysine. After washing in PBS the cells were fixed by incubating the coverslips with 4% (w/v) parafomaldehyde for 30 min. The cells were then rinsed with PBS and incubated with PBSA [3% (v/v) donkey serum in PBS] for 40 min to block non-specific antibody binding. After rinsing in PBS, antibody staining was performed for 1 h with an optimized dilution for each different antibody used either alone or in combination [rabbit anti-FLAG polyclonal antibody (Sigma) 1:200 and/or a mouse anti-Myc9E10 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) 1:50]. The cells were then rinsed twice in PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at 22 °C. PRH and TLE1 were detected with a TRITC (tetramethylrhodamine β-isothiocyanate) donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody (Stratec) and an Alexa Fluor® 488-labelled donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Molecular Probes) respectively, both at a 1:100 dilution. The coverslips were mounted on slides with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole)-containing mounting medium (Vectashield) and immunostained cells were viewed on a Leica DM IRBE confocal microscope. Imaging was performed using Leica Confocal Software Version 2.00.

RESULTS

PRH increases the retention of TLE proteins within the nucleus

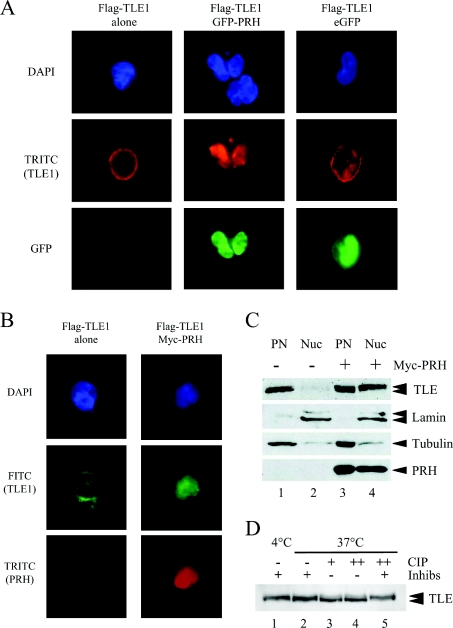

To determine whether PRH alters the subcellular localization of TLE in haematopoietic cells, we transfected K562 cells with plasmids expressing pFLAG–TLE1 alone or pFLAG–TLE1 together with GFP or GFP–PRH. We examined the subcellular localization of these proteins using immunofluorescent staining and confocal microscopy. A TRITC-labelled anti-FLAG antibody was used to detect FLAG–TLE1, the intrinsic fluorescence of the GFP proteins was used to detect GFP and GFP–PRH, and DAPI was used to detect DNA. Results from representative transfected cells are shown in Figure 1(A). When expressed alone FLAG–TLE1 (red) was present in the cytoplasm and nucleus of K562 cells (Figure 1A, middle left-hand panel); however co-expression with GFP–PRH resulted in the majority of FLAG–TLE1 appearing in the nucleus (Figure 1A, middle panel), whereas co-expression with GFP resulted in the majority of TLE1 remaining in the cytoplasm (Figure 1A, middle right-hand panel). This experiment was repeated using a Myc-tagged PRH protein to rule out any effects of the GFP tag on PRH activity. Immunofluorescence results from representative transfected cells are shown in Figure 1(B). In the absence of Myc–PRH, FLAG–TLE1 (green) was present in the nucleus, but was predominantly present in the cytoplasm of K562 cells. Co-expression of Myc–PRH with FLAG–TLE1 resulted in the majority of TLE1 appearing in the nucleus (Figure 1A, middle right-hand panel) together with Myc–PRH (Figure 1A, bottom right-hand panel). Taken together these results suggest that PRH influences the localization of TLE proteins in the cell.

Figure 1. PRH alters the distribution of TLE proteins in the cell.

(A) K562 cells were transiently transfected with vectors expressing FLAG–TLE1, FLAG–TLE1 and GFP–PRH or FLAG–TLE1 and GFP and then adhered to poly-lysine-coated coverslips. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). FLAG–TLE1 was visualized using an anti-FLAG antibody and a TRITC-labelled secondary antibody (red). GFP–PRH and GFP were visualized directly (green). The cells were viewed using a Leica DM IRBE confocal microscope. (B) K562 cells were transiently transfected with vectors expressing FLAG–TLE1 or FLAG–TLE1 and Myc–PRH and then adhered to poly-lysine-coated coverslips. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). FLAG–TLE1 was visualized using an anti-FLAG antibody and a FITC-labelled secondary antibody (green). Myc–PRH was visualized using an anti-Myc9E10 antibody and a TRITC-labelled secondary antibody (red). The cells were viewed using confocal microscopy as above. (C) Untransfected K562 cells and cells transiently transfected with a vector expressing Myc–PRH were fractionated into post-nuclear (PN) and nuclear (Nuc) extracts. The proteins were then separated by SDS/PAGE and Western blotted for endogenous TLE proteins using a pan-TLE antibody (top panel), lamin A/C using a rabbit polyclonal anti-lamin antibody (second panel), tubulin using a mouse monoclonal anti-tubulin antibody (third panel) and Myc–PRH using an anti-Myc9E10 antibody (bottom panel). (D) K562 nuclear extracts from cells expressing Myc–PRH were incubated with a cocktail of phosphatase inhibitors in CIP buffer for 30 mins at 4 °C (lane 1) or 37 °C (lane 2). In lanes 3 and 4, CIP was added to nuclear extracts without phosphatase inhibitors for 30 min at 37 °C [1 μl (lane 3) or 2 μl (lane 4)]. In lane 5, CIP (2 μl) was added to nuclear extracts containing phosphatase inhibitors for 30 min at 37 °C.

To examine whether endogenous TLE proteins are also retained in the nucleus by expression of Myc–PRH we first examined the subcellular localization of TLE proteins using immunofluorescent staining and confocal microscopy. A FITC-labelled pan-TLE polyclonal antibody was used to detect the expression of endogenous TLE proteins; however, these experiments were not conclusive as the expression of Myc–PRH in the nucleus hindered detection of the endogenous TLE proteins (weak FITC signal) in the cell. Therefore to address this question we next examined the subcellular localization of endogenous TLE proteins using subcellular fractionation and Western blot analysis. K562 cells or K562 cells expressing Myc–PRH were fractionated into the post-nuclear fraction consisting of cytoplasmic and loosely held nuclear proteins and nuclear fractions consisting of tightly held nuclear proteins. To compare the endogenous TLE protein levels in each subcellular compartment an equal amount of protein from each fraction was loaded on to SDS/PAGE and the TLE proteins were detected using the pan-TLE antibody. Fractionation and equal loading in each fraction was assessed by the expression of tubulin in the post-nuclear fraction and lamin A/C in the nuclear fraction. Figure 1(C) shows that endogenous TLE proteins were predominantly localized to the post-nuclear fraction although a faint band was present in the nuclear fraction (compare lanes 1 and 2). In contrast, in the presence of Myc–PRH, endogenous TLE was strongly present in the nuclear fraction (Figure 1C, compare lanes 3 and 4). The blot was stripped and reprobed with the Myc-antibody to detect Myc–PRH. Myc–PRH was present in both the post-nuclear and nuclear fractions (Figure 1C, lanes 3 and 4 lower panel). We conclude that PRH increases the nuclear retention of TLE proteins. Our previous immunofluoresence experiments with Myc–PRH have shown that PRH is present in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm [7]. This is in agreement with the fractionation experiments presented in Figure 1. However PRH localization in the presence of TLE appears strongly nuclear in the immunofluorescence experiments shown above. This suggests that co-expression of PRH with TLE has an influence on the localization of PRH and vice versa.

TLE runs as a doublet on SDS/PAGE due to phosphorylation [49]. The upper TLE band in Figure 1(C) (lane 4) very probably corresponds to hyperphosphorylated TLE, and expression of PRH brings about an increase in the intensity of this band suggesting that PRH induces TLE phosphorylation (Figure 1C, compare lane 1 with lane 4). To establish that the TLE proteins of retarded mobility correspond to TLE phosphoproteins induced by PRH expression, we incubated K562 nuclear extracts transfected with Myc–PRH with CIP. There is a predominance of the TLE band of retarded mobility (Figure 1D, lanes 1 and 2) after incubation at 4 °C or 37 °C in the presence of a cocktail of phosphatase inhibitors. Incubation of nuclear extracts with CIP in the absence of phosphatase inhibitors resulted in a decrease in the intensity of this upper band and an increase in intensity of the lower TLE band (lanes 3 and 4). In contrast, incubation of the extracts with CIP in the presence of phosphatase inhibitors does not lead to a change in the TLE band (lane 5). These results show that the TLE band of reduced mobility observed in the presence of Myc–PRH corresponds to phosphorylated TLE.

Mutations in the PRH homeodomain block nuclear relocalization of TLE

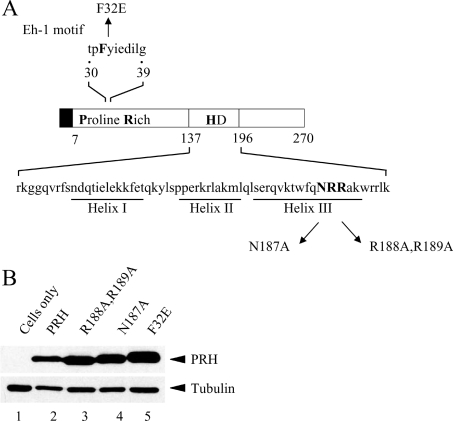

To investigate whether the DNA-binding and nuclear-localization activities of PRH are required for the relocalization of TLE proteins we designed two mutations in the Myc–PRH protein: PRH N187A and PRH R188A,R189A. These mutations lie in the homeodomain of the PRH protein and are shown in Figure 2(A). The N187A mutation is predicted to significantly reduce the DNA-binding activity of PRH since we have shown previously that mutation of asparagine to alanine at the equivalent position in the highly conserved avian PRH homeodomain prevents DNA binding [6]. The R188A,R189A double mutation is predicted to prevent the nuclear localization of PRH as mutation of these arginine residues to alanine has been reported to block the nuclear localization of PRH in NIH 3T3 cells [12]. To create these mutations we performed site-directed mutagenesis of PRH in the expression plasmid pMUG1-Myc–PRH (as described in the Experimental section). To check that the mutated Myc-tagged PRH proteins were expressed at similar levels, K562 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing Myc–PRH or each of the mutant Myc–PRH proteins and cell extracts were produced. Western blot analysis with the anti-Myc antibody and tubulin antibodies showed that these proteins are expressed at equivalent levels in K562 cells (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. PRH mutants used in the present study.

(A) A schematic representation of the PRH protein and the PRH mutants used in the present study. The Myc tag is represented by the filled box. The proline-rich domain and homeodomain (HD) are indicated. (B) Whole-cell extracts were prepared from untransfected K562 cells (lane 1) and cells transiently transfected with vectors expressing Myc–PRH (lane 2), Myc–PRH R188A,R189A (lane 3), Myc–PRH N187A (lane 4) or Myc–PRH F32E (lane 5). The proteins were then separated by SDS/PAGE and Western blotted for PRH using an anti-Myc9E10 antibody and a mouse monoclonal anti-tubulin antibody as a control for protein loading.

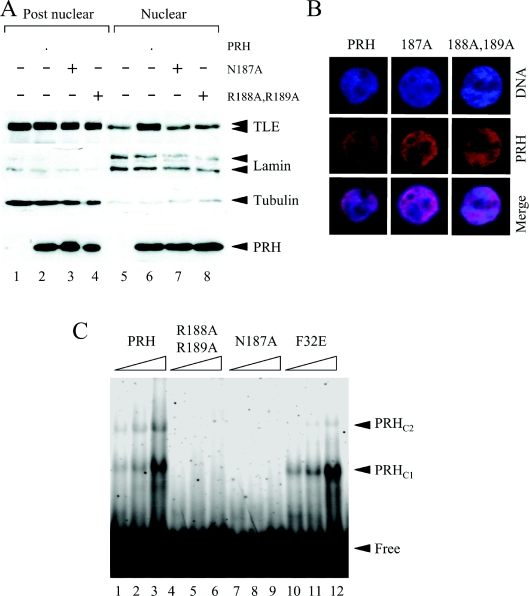

To determine whether PRH proteins that carry these mutations can alter the retention of TLE proteins, K562 cells or K562 cells expressing Myc–PRH or the mutated proteins were fractionated into nuclear and post-nuclear extracts. Equal amounts of total protein from each fraction were loaded on to SDS/PAGE and Western blotted with a pan-TLE antibody (Figure 3A, top panel) or an anti-Myc antibody (Figure 3A, bottom panel). The blots were stripped and reprobed for lamin A/C and tubulin to examine fractionation quality and loaded as before. As expected, wild-type PRH was able to alter the distribution of TLE proteins in each fraction and to induce TLE hyperphosphorylation (Figure 3A, compare lanes 1 and 5 with lanes 2 and 6). However both mutant PRH proteins were unable to influence the distribution of endogenous TLE (Figure 3A, top panel, lanes 7 and 8). Although these results suggest that both the DNA-binding activity of PRH and the nuclear localization of PRH are required in order to retain nuclear TLE proteins, it is clear that the nuclear localization mutant Myc–PRH R188A,R189A is present in both the post-nuclear and nuclear extracts (Figure 3A, bottom panel).

Figure 3. Mutations in the PRH homeodomain block nuclear retention of TLE.

(A) Untransfected K562 cells and cells transiently transfected with vectors expressing Myc–PRH, Myc–PRH N187A or Myc–PRH R188A,R189A were fractionated into post-nuclear and nuclear extracts. The proteins were then separated by SDS/PAGE and Western blotted for endogenous TLE (top panel), lamin A/C (second panel), tubulin (third panel) or Myc–PRH proteins (bottom panel) as described in Figure 1(C). (B) K562 cells growing on coverslips were transiently transfected with vectors expressing Myc–PRH, Myc–PRH N187A or Myc–PRH R188A,R189A. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue) and Myc–PRH was visualized using an anti-Myc9E10 antibody and a TRITC-labelled secondary antibody (red). The cells were viewed using a Leica DM IRBE confocal microscope. (C) A labelled oligonucleotide carrying a PRH-binding site was incubated with increasing concentrations (125, 250 and 500 nM) of His-tagged PRH (lanes 1–3), His-tagged PRH R188A,R189A (lanes 4–6), PRH N187A (lanes 7–9) and PRH F32E (lanes 10–12) under the conditions described in the main text. Free and bound DNA was then resolved on a 6% polyacrylamide gel and visualized using a PhosphoImager. Two retarded complexes (PRHC1 and PRHC2) are formed when PRH binds to the DNA.

To further examine the localization of the mutant PRH proteins we used immunofluorescence microscopy. Figure 3(B) shows high-magnification pictures of K562 cells stained with DAPI to visualize the DNA (blue) and with TRITC (red) to visualize the PRH proteins. When the DAPI stain and the TRITC stain were merged the cells appeared pink, demonstrating that wild-type PRH and the mutant PRH proteins were present in the nucleus of K562 cells. These results demonstrate that, in these cells, PRH N187A and PRH R188A,R189A are able to localize in the nucleus like wild-type PRH. We conclude that in K562 cells PRH R188A,R189A are not defective in nuclear localization.

PRH R188A,R189A has a defect in DNA binding

We next investigated the DNA-binding properties of the mutated proteins. The mutated PRH cDNAs present in the mammalian expression constructs were transferred to the pTrc-HisA bacterial expression vector (see the Experimental section). The resulting constructs inducibly express His-tagged mutated PRH proteins in bacterial cells. Bacterial extracts expressing the mutated PRH proteins or the wild-type protein were used to partially purify His-tagged PRH proteins over a nickel-charged affinity column and these partially purified proteins were used in EMSAs with a labelled PRH-binding site as described previously [2,34]. Figure 3(C) shows that full length His–PRH was able to bind to DNA in the EMSA and form two retarded DNA–PRH complexes. In contrast, neither His–PRH N187A nor His–PRH R188A,R189A form PRH–DNA complexes.

In summary, we have demonstrated that both PRH N187A and PRH R188A,R189A can localize to the nucleus and that they are both defective in DNA binding and influencing the nuclear retention of TLE proteins. Since both mutations in the homeodomain block DNA binding and the nuclear retention of TLE proteins, but do not appear to significantly affect the nuclear retention of PRH, we conclude that DNA binding by PRH is necessary for the retention of TLE within the nucleus.

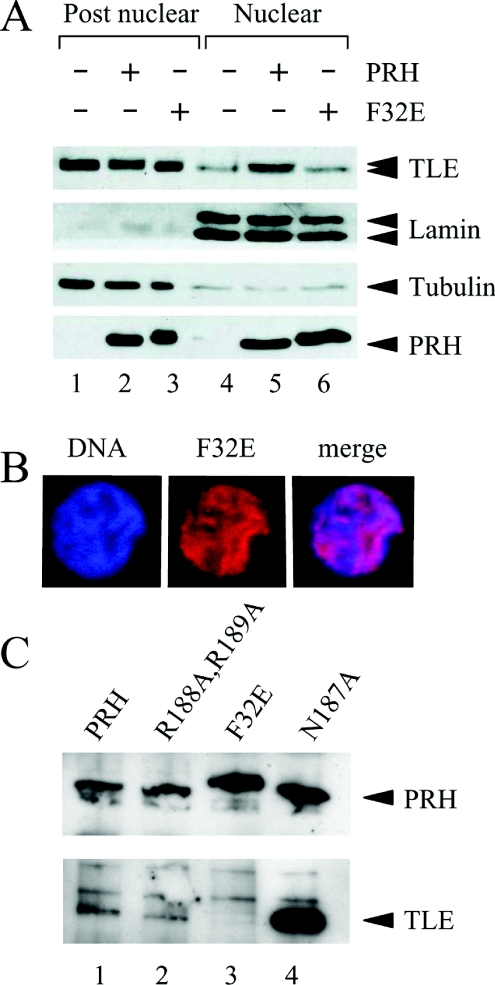

Mutation of the PRH Eh-1 motif blocks nuclear retention of TLE

To investigate whether the PRH–TLE interaction is required for the nuclear retention of TLE proteins we examined the subcellular distribution of TLE proteins in the presence of Myc–PRH F32E (see Figure 2). A plasmid expressing Myc–PRH F32E was produced in our previous study [7]. The PRH F32E mutation was designed to inhibit the binding of PRH to TLE1. This mutation lies in the N-terminal Eh-1 motif in PRH and our previous studies have shown that this mutation eliminates the interaction between TLE1 and the PRH N-terminal domain [7]. K562 cells, or cells expressing Myc–PRH or Myc–PRH F32E were fractionated and Western blotted as described above. Figure 4(A) (top panel) shows that PRH F32E is unable to alter the nuclear retention of endogenous TLE proteins (lanes 3 and 6). These fractionation experiments also demonstrate that the mutant PRH F32E protein is not altered in its ability to be retained in the nucleus compared with wild-type PRH and is expressed at a similar level to wild-type PRH (Figure 4A, bottom panel). The mutant protein shows a slightly retarded mobility compared with wild-type PRH (Figure 4A, bottom panel). The changed mobility of the protein is also apparent in a fusion protein consisting of GST (glutathione transferase) fused to the PRH N-terminal domain carrying the F32E mutation [7]. The reason for this apparent change in mobility is not known at present. We confirmed that the nuclear localization of the PRH F32E was not altered compared with wild-type PRH, using immunostaining experiments and confocal microscopy (Figure 4B, middle panel). Thus the F32E mutation in the Eh-1 domain of PRH does not appear to alter nuclear localization of PRH but does block the influence of PRH on the retention of TLE proteins.

Figure 4. Mutation of the PRH Eh-1 motif blocks the nuclear retention of TLE.

(A) Untransfected K562 cells and cells transiently transfected with vectors expressing Myc–PRH or Myc–PRH F32E were fractionated into post-nuclear and nuclear extracts. The proteins were then separated by SDS/PAGE and Western blotted for endogenous TLE (top panel), Myc–PRH proteins (bottom panel), lamin A/C (second panel) or tubulin (third panel) as described in Figure 1(C). (B) K562 cells growing on coverslips were transiently transfected with a vector expressing Myc–PRH F32E. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue) and Myc–PRH F32E (red) was visualized exactly as described in Figure 3(B). (C) Whole-cell extracts were prepared from K562 cells transiently co-transfected with a vector expressing FLAG–TLE1 and vectors expressing Myc–PRH (lane 1), Myc–PRH R188A,R189A (lane 2), Myc–PRH N187A (lane 3) or Myc–PRH F32E (lane 4). The Myc-tagged proteins were then immunoprecipitated using an anti-Myc9E10 antibody. The immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and Western blotted for PRH using an anti-Myc9E10 antibody (top panel) and co-immunoprecipitated TLE using an anti-FLAG antibody (lower panel).

To check that the DNA-binding properties of PRH are not altered by the F32E mutation in the Eh-1 domain we transferred the mutated PRH cDNA present in the mammalian expression constructs to a bacterial expression vector downstream of a His-tag. The His-tagged proteins were then partially purified and used in EMSAs in parallel with the EMSA carried out previously for the wild-type PRH protein and the PRH proteins carrying mutations in the homeodomain. Figure 3(C) shows that PRH F32E was able to bind DNA and formed the same PRH–DNA complexes as wild-type PRH (compare lanes 3 and 12). Therefore the PRH F32E mutation did not significantly alter the DNA-binding properties of PRH.

The F32E mutation blocked the binding of the isolated PRH N-terminal domain to TLE in pulldown experiments. To confirm that the F32E mutation inhibited the binding of PRH to TLE in the context of full-length PRH protein in vivo, we carried out co-immunoprecipitation experiments with Myc-tagged PRH and FLAG-tagged TLE1. Cell extracts were made from K562 cells expressing Myc–PRH and FLAG–TLE1 or each of the mutant Myc–PRH proteins and FLAG–TLE1 and immunoprecipitated with an anti-Myc antibody bound to Protein G beads. After extensive washing, the proteins were loaded on to SDS/PAGE and Western blotted with the anti-Myc antibody to detect Myc–PRH, and with a FLAG antibody to detect FLAG–TLE1. Figure 4(C) (top panel) shows that the Myc-tagged PRH proteins were all immunoprecipitated by the anti-Myc antibody to approximately the same extent. PRH and the PRH N187A and PRH R188A,R189A mutants all co-immunoprecipitated FLAG-tagged TLE, whereas PRH F32E failed to co-immunoprecipitate TLE (bottom panel). These results demonstrate that the F32E mutation in the PRH Eh-1 domain prevents the interaction of PRH and TLE in cells. In this experiment the PRH N187A appears to immunoprecipitate much more TLE than the corresponding wild-type PRH protein, which may reflect an increased binding affinity between PRH N187A and TLE proteins.

Repression by PRH requires retention of TLE proteins in the nuclear fraction

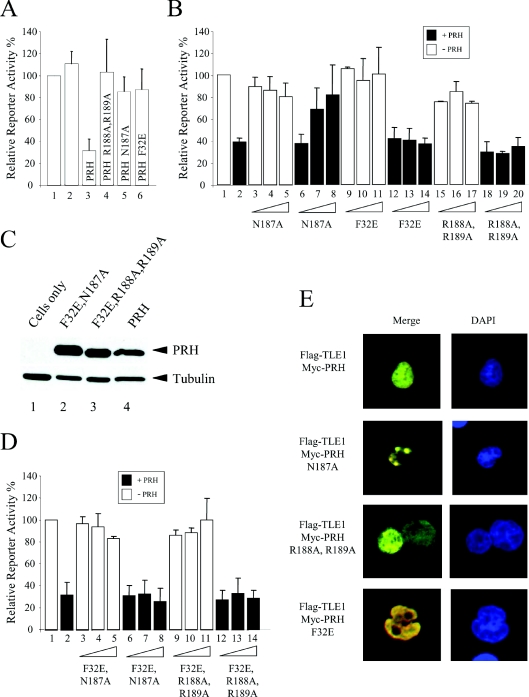

In order to study the transcription repression properties of these mutated PRH proteins, a reporter plasmid carrying the luciferase gene under the control of the TK promoter and five PRH-binding sites was transiently transfected into K562 cells with vectors expressing PRH or the PRH mutants. In addition, all cells were co-transfected with a plasmid expressing β-galactosidase to act as a control for transient transfection efficiency. Figure 5(A) shows that although PRH represses reporter activity to approx. 30% of the unrepressed level, the DNA-binding-deficient mutants PRH N187A and PRH R188A,R189A showed little or no repression activity. In this assay PRH F32E was a very poor repressor and had no more repression activity than the DNA-binding-defective protein PRH N187A (Figure 5A, column 6). PRH is able to repress transcription by several mechanisms, including binding to the TATA box, and we have shown previously that at high expression levels PRH F32E has some ability to repress transcription, presumably via binding to the TATA box or because of residual binding to TLE. In the present study we have directly compared the repression activity of PRH F32E with that of wild-type PRH, and Western blot analysis confirmed that in this assay the proteins were expressed at equivalent levels in the transfected cells (Figure 2B). We have demonstrated that PRH F32E does not influence the retention of TLE proteins in the nucleus and that this protein can bind to DNA such as wild-type PRH. We conclude that the direct interaction between PRH and TLE is essential for the enhanced nuclear retention of TLE proteins brought about by PRH and plays an important role in transcriptional repression by PRH.

Figure 5. PRH N187A is trans-dominant over PRH in transcription repression assays.

The histograms show the relative promoter activity found in K562 cell extracts 24 h after transient co-transfection with a reporter plasmid containing the luciferase gene under the control of the TK promoter and five PRH-binding sites (pTK–PRH), a β-galactosidase expression plasmid (pSV-lacZ) and PRH expression vectors. Relative promoter activity is the luciferase activity normalized with respect to transfection efficiency using the co-transfected β-galactosidase plasmid. Each transfection was performed a minimum of three times and the values shown are the means±S.D. (A) K562 cells were transfected with 5 μg of pTK–PRH alone (lane 1), pTK–PRH and 1 μg of an empty expression vector (lane 2), or pTK–PRH and 1 μg of pMUG1-PRH (lane 3), pMUG1-PRH R188A,R189A (lane 4), pMUG1-PRH N187A (lane 5) or pMUG1-PRH F32E (lane 6). (B) K562 cells were transfected with 5 μg of pTK–PRH alone (lane 1), pTK–PRH and 1 μg of pMUG1-PRH (lane 2), or pTK–PRH and increasing amounts (0.5, 1 and 2 μg) of the expressor plasmids indicated either with (filled bars) or without (empty bars) 1 μg of co-transfected pMUG1-PRH. (C) Whole-cell extracts were prepared from untransfected K562 cells (lane 1) and cells transiently transfected with vectors expressing Myc–PRH F32E,N187A (lane 2), Myc–PRH F32E,R188A,R189A (lane 3) or Myc–PRH (lane 4). The proteins were then separated by SDS/PAGE and Western blotted for PRH using an anti-Myc9E10 antibody. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with an anti-tubulin antibody as a control for protein loading. (D) The experiment described in (B) was repeated using vectors expressing the PRH double mutants PRH F32E,N187A and PRH F32E,R188A,R189A. (E) K562 cells were transiently transfected with vectors expressing FLAG–TLE1 and Myc–PRH or Myc-tagged PRH mutant proteins and then adhered to poly-lysine-coated coverslips. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). FLAG–TLE1 was visualized using an anti-FLAG antibody and a FITC-labelled secondary antibody (green). Myc–PRH was visualized using an anti-Myc9E10 antibody and a TRITC-labelled secondary antibody (red). The cells were viewed using confocal microscopy. Co-localized proteins produce a yellow colour.

PRH N187A is trans-dominant over PRH

The results presented above demonstrate that PRH N187A, PRH R188A,R189A and PRH F32E are all defective in repression. In order to further dissect the mechanisms whereby PRH represses transcription, we next examined whether any of these mutant PRH proteins would have a trans-dominant-negative activity over transcriptional repression by wild-type PRH. The pTK–PRH reporter plasmid described above was transfected into K562 cells with plasmids expressing wild-type PRH and increasing amounts of each of the plasmids expressing mutant PRH proteins. As before, all cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing β-galactosidase to control for transfection efficiency. Figure 5(B) shows that, as expected, PRH repressed transcription to approx. 40% of unrepressed promoter activity (lane 2). Increasing amounts of PRH N187A (lanes 3–5), PRH F32E (lanes 9–11) or PRH R188A,R189A (lanes 15–17) did not result in transcriptional repression (as shown previously in Figure 5A); however, co-expression of PRH with increasing amounts of PRH N187A resulted in a significant decrease in repression by PRH (lanes 6–8) and at a 2:1 ratio of PRH N187/PRH there was almost a complete loss of repression. In contrast, co-expression of PRH with increasing amounts of PRH F32E (lanes 12–14) or PRH R188A,R189A (lanes 18–20) did not alter the repression activity of PRH. Thus these results demonstrate that PRH N187A has a trans-dominant-negative activity over wild-type PRH for transcriptional repression.

To investigate the mechanism of this trans-dominant inhibition of PRH repression activity we used site-directed mutagenesis to make two PRH expression plasmids that carried either a combination of the F32E and N187A mutations or the F32E and R188A,R189A mutations. K562 cells were transfected with the reporter plasmid, the PRH expression vector and increasing amounts of plasmids expressing these double mutants. Western blot analysis confirmed that the double mutants were expressed at equivalent levels to wild-type PRH (Figure 5C). Figure 5(D) shows that PRH repressed transcription to approx. 30% of unrepressed promoter activity (lane 2) and that increasing amounts of PRH F32E,N187A (lanes 3–5) or PRH F32E,R188A,R189A (lanes 9–11) did not result in transcriptional repression. Co-expression of PRH with increasing amounts of PRH F32E,N187A (lanes 6–8) or PRH F32E,R188A,R189A (lanes 12–14) did not result in a decrease in repression activity. Since PRH N187A has trans-dominant negative activity but PRH F32E,N187A does not, we infer that titration of TLE is essential for the trans-dominant-negative activity of PRH N187A.

We have previously shown that Myc–PRH expression is cytoplasmic and diffuse nuclear [7], and that the accumulation of this protein in nuclear foci is apparent at lower levels of expression [2]. We have also shown that co-expression of PRH with FLAG–TLE1 protein results in their co-localization. Both proteins show diffuse nuclear staining but, in addition, there is co-localization in subnuclear foci [7]. To determine whether the trans-dominant-negative protein PRH N187A is able to sequester TLE proteins away from wild-type PRH and into a particular subnuclear compartment we expressed FLAG–TLE1 protein in K562 cells. The FLAG–TLE protein showed a diffuse nuclear staining pattern (Figure 1A). We also expressed each of the Myc–PRH proteins in K562 cells (Figures 3B and 4B) and these proteins also showed diffuse nuclear staining. Interestingly, the co-expression of Myc–PRH N187A and FLAG–TLE1 showed strong co-localization of the two proteins in subnuclear foci (Figure 5E) in immunofluorescent staining experiments (large yellow dots). In contrast, the co-expression of TRITC-labelled Myc–PRH (wild-type) or Myc–PRH F32E with FLAG–TLE1 resulted in co-localization in the nucleus in a predominantly diffuse nuclear staining pattern (Figure 5E). We conclude that the subnuclear localization of PRH N187A and TLE1 are altered when the proteins are co-expressed. Thus the interaction of PRH N187A with TLE results in the sequestration of TLE in a subnuclear compartment that is not the same as the subnuclear compartment occupied by wild-type PRH and TLE1. We infer that the inability of PRH to bind to DNA prevents PRH N187A from taking TLE1 to the DNA/chromatin or alternatively prevents TLE1 from taking PRHN187A to the DNA/chromatin. In any event we conclude that sequestration of TLE proteins to a different subnuclear localization is involved in the trans-dominant-negative activity of this protein.

DISCUSSION

PRH is a transcriptional repressor protein that plays important roles in the regulation of several cellular processes including haematopoiesis. PRH is present in both the cytoplasm and nucleus of haematopoietic cells from myeloid lineages [7,27,31]. Aberrant expression of PRH or loss of nuclear localization of PRH contributes to leukaemia [31]. K562 cells are blast cells that can spontaneously differentiate along myeloid and erythroid lineages. In the main, these cells contain a very large nucleus and relatively little cytoplasm. Immunofluorescent staining of PRH and TLE proteins in these cells has shown that PRH and TLE can be present in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm [7]. We have used biochemical fractionation to examine the nuclear retention of TLE proteins. We have shown that endogenous nuclear TLE proteins are not tightly bound in the nuclei of K562 cells and fractionate into the post-nuclear fraction; however, in the presence of exogenous PRH, endogenous TLE proteins become strongly retained in the nuclear fraction. In other cell types the Hes1 and Runx-1 repressor proteins have been shown to bind to TLE and increase the nuclear retention of TLE by increasing the association of TLE with chromatin [49]. Further experiments are required to establish whether the mechanism of nuclear retention of TLE in the presence of PRH is similar to that effected by Hes1 and involves chromatin association of TLE proteins or other subnuclear compartments such as the nuclear matrix.

The mutation of asparagine to alanine (N187A) in the DNA recognition helix of the PRH homeodomain and mutation of adjacent arginine residues (R188A,R189A) results in proteins that are unable to bind to DNA. These mutants are both unable to influence the nuclear retention of TLE proteins, although they are able to bind to TLE. In fractionation studies both PRH N187A and PRH R188A,R189A show both post-nuclear and nuclear distribution. PRH N187A acts as a trans-dominant-negative protein in repression assays with wild-type PRH. In contrast, PRH R188A,R189A does not act as a trans-dominant-negative protein. In the present study we have shown that PRH N187A and TLE co-localize in subnuclear foci, whereas PRH R188A,R189A and TLE do not co-localize in these foci. Presumably this difference accounts for the trans-dominant repression activity of PRH N187A; however the difference in the ability of these proteins to have trans-dominant activity over wild-type PRH may be because PRH N187A has a higher affinity for TLE or because the PRH R188A,R189A has a subtle defect in nuclear retention. It is also possible that the higher affinity of PRH N187A for TLE and/or the subtle defect of PRH R188A,R189A in nuclear retention are responsible for the difference in subnuclear localization. Finally we cannot rule out the possibility that sequestration of TLE is not wholly responsible for the trans-dominant-negative activity of PRH N187A. PRH is known to form oligomers and it may be that PRH N187A, but not the PRH R188A,R189A mutant, is able to form hetero-oligomers with wild-type PRH and thereby block repression. Interestingly, it is clear that in complete contrast with previous reports, PRH R188A,R189A is able to enter the nucleus of K562 cells, suggesting that this mutation does not strongly affect the nuclear localization of PRH in these cells although this mutation does inhibit the nuclear localization of PRH in NIH 3T3 cells [12]. One reason for this discrepancy could be that K562-cell-specific proteins might aid the nuclear import of this mutant.

As might be expected, a mutation in the Eh1 motif (F32E) located within the N-terminal domain of PRH reduces binding to TLE and blocks nuclear retention of TLE. Thus the retention of TLE proteins within the nucleus requires two properties of the PRH protein: a direct protein–protein interaction between PRH and TLE and DNA binding by PRH. Neither DNA binding alone, nor TLE binding alone by PRH is sufficient for nuclear retention of TLE or in fact for transcriptional repression by PRH. Presumably the nuclear retention of TLE proteins is necessary for transcriptional repression by PRH. We have reported previously that although PRH F32E is defective in binding to TLE and defective in repression compared with wild-type PRH, it retains some repression activity when expressed at high levels. We suggest that this is because the mutant is not completely unable to bind TLE and retains weak TLE-binding activity which may become apparent at very high expression levels.

Since a defect in binding TLE blocks repression as effectively as a defect in DNA binding, we conclude that most of the PRH-dependent repression observed at the pTK–PRH promoter is TLE-dependent; however, it is possible that mutation of the Eh-1 domain might also affect the conformation of the PRH protein and hence also decrease the interaction of PRH with other PRH-interacting proteins. The trans-dominant-negative activity of the DNA-binding mutant PRH N187A together with the loss of this trans-dominant-negative activity in the PRH F32E,N187A double mutant (cannot bind to DNA and TLE) reinforces the idea that transcriptional repression is very sensitive to the availability of TLE. PRH N187A may prove to be a useful tool for understanding the direct and indirect transcriptional activities of PRH. Clearly the ability of PRH N187A to act as a trans-dominant negative for PRH repression activity occurs through a very different mechanism from that inferred for the trans-dominant-negative activity of a Nup–Hex/PRH fusion protein identified recently in a patient with acute myeloid leukaemia. In the Nup–Hex/PRH fusion protein, the N-terminus of the nucleoporin protein Nup98 is fused in-frame with the homeodomain and C-terminus of PRH. In this case the N-terminus (TLE-binding region) of PRH is absent in the fusion protein and it is thought that the trans-dominant-negative function of Nup–Hex/PRH derives from the ability of the fusion protein to compete with PRH for PRH-binding sites [32]. The experiments outlined above demonstrate that there is more than one way to block PRH repression activity and suggest that acute myeloid leukaemic patients might harbour a variety of PRH mutations.

We have shown in the present study that PRH directly affects nuclear retention of TLE and presumably, as a consequence, availability of TLE in discrete subnuclear domains. Thus it is very likely that TLE-dependent genes may be equally sensitive to PRH levels. Further work is required to determine whether alterations in PRH expression impact on the plethora of TLE-repressed genes that do not appear to contain binding sites for PRH. Our studies have shown that PRH can influence the amount of available TLE proteins in the nucleus; however, it is not known whether binding of TLE to PRH results in PRH sequestering TLE away from other transcription factors in the nucleus or whether PRH simply increases the amount of free TLE proteins in the nucleus. The Wnt signalling pathway functions in haematopoietic progenitors to promote self renewal [52]. TLE proteins are important antagonists for Wnt signalling [53,54]. The Notch signalling pathway also functions in haematopoietic progenitors to inhibit differentiation along myeloid lineages and thereby increase the amount of undifferentiated progenitors [55,56]. TLE proteins mediate the Notch signalling pathway and thereby promote the inhibition of differentiation [55,56]. Thus an increase in available TLE in the nucleus might be expected to inhibit self renewal and decrease differentiation. Interestingly PRH functions as an inhibitor of cell proliferation in early haematopoietic progenitors and in differentiated myeloid cells. Although the effect of PRH on cell proliferation has been shown to be through the regulatory effect of PRH on the translation factor eIF-4E [12], the anti-proliferative effects of PRH could also be a consequence of PRH altering the amount of available nuclear TLE.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor Stefano Stifani (Montreal Neurological Institute, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) for useful discussions.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust [grant number WT076527]; and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council [grant number BB/D005094/1] (to P.-S. J. and K. G.).

References

- 1.Soufi A., Jayaraman P.-S. PRH/Hex: an oligomeric transcription factor and multifunctional regulator of cell fate. Biochem. J. 2008;412:399–413. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soufi A., Smith C., Clarke A. R., Gaston K., Jayaraman P.-S. Oligomerisation of the developmental regulator proline rich homeodomain (PRH/Hex) is mediated by a novel proline-rich dimerisation domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;358:943–962. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka T., Inazu T., Yamada K., Myint Z., Keng V. W., Inoue Y., Taniguchi N., Noguchi T. cDNA cloning and expression of rat homeobox gene, Hex, and functional characterization of the protein. Biochem. J. 1999;339:111–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pellizzari L., D'Elia A., Rustighi A., Manfioletti G., Tell G., Damante G. Expression and function of the homeodomain-containing protein Hex in thyroid cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2503–2511. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.13.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brickman J. M., Jones C. M., Clements M., Smith J. C., Beddington R. S. Hex is a transcriptional repressor that contributes to anterior identity and suppresses Spemann organiser function. Development. 2000;127:2303–2315. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.11.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guiral M., Bess K., Goodwin G., Jayaraman P.-S. PRH represses transcription in hematopoietic cells by at least two independent mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:2961–2970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004948200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swingler T. E., Bess K. L., Yao J., Stifani S., Jayaraman P.-S. The proline-rich homeodomain protein recruits members of the Groucho/transducin-like enhancer of split protein family to co-repress transcription in hematopoietic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:34938–34947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404488200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denson L. A., Karpen S. J., Bogue C. W., Jacobs H. C. Divergent homeobox gene hex regulates promoter of the Na+-dependent bile acid cotransporter. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G347–G355. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.2.G347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minami T., Murakami T., Horiuchi K., Miura M., Noguchi T., Miyazaki J., Hamakubo T., Aird W. C., Kodama T. Interaction between hex and GATA transcription factors in vascular endothelial cells inhibits flk-1/KDR-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:20626–20635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308730200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sekiguchi K., Kurabayashi M., Oyama Y., Aihara Y., Tanaka T., Sakamoto H., Hoshino Y., Kanda T., Yokoyama T., Shimomura Y., et al. Homeobox protein Hex induces SMemb/non-muscle myosin heavy chain-B gene expression through the cAMP-responsive element. Circ. Res. 2001;88:52–58. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaefer L. K., Shuguang W., Schaefer T. S. Functional interaction of Jun and homeodomain proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:43074–43082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Topisirovic I., Culjkovic B., Cohen N., Perez J. M., Skrabanek L., Borden K. L. The proline-rich homeodomain protein, PRH, is a tissue-specific inhibitor of eIF4E-dependent cyclin D1 mRNA transport and growth. EMBO J. 2003;22:689–703. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bogue C. W., Zhang P. X., McGrath J., Jacobs H. C., Fuleihan R. L. Impaired B cell development and function in mice with a targeted disruption of the homeobox gene Hex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:556–561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0236979100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hallaq H., Pinter E., Enciso J., McGrath J., Zeiss C., Brueckner M., Madri J., Jacobs H. C., Wilson C. M., Vasavada H., et al. A null mutation of Hex results in abnormal cardiac development, defective vasculogenesis and elevated Vegfa levels. Development. 2004;131:5197–5209. doi: 10.1242/dev.01393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez Barbera J. P., Clements M., Thomas P., Rodriguez T., Meloy D., Kioussis D., Beddington R. S. The homeobox gene Hex is required in definitive endodermal tissues for normal forebrain, liver and thyroid formation. Development. 2000;127:2433–2445. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.11.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo Y., Chan R., Ramsey H., Li W., Xie X., Shelley W. C., Martinez-Barbera J. P., Bort B., Zaret K., Yoder M., Hromas R. The homeoprotein Hhex is required for hemangioblast differentiation. Blood. 2003;102:2428–2435. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubo A., Chen V., Kennedy M., Zahradka E., Daley G. Q., Keller G. The homeobox gene HEX regulates proliferation and differentiation of hemangioblasts and endothelial cells during ES cell differentiation. Blood. 2005;105:4590–4597. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liao W., Ho C. Y., Yan Y. L., Postlethwait J., Stainier D. Y. Hhex and scl function in parallel to regulate early endothelial and blood differentiation in zebrafish. Development. 2000;127:4303–4313. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.20.4303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newman C. S., Chia F., Krieg P. A. The XHex homeobox gene is expressed during development of the vascular endothelium: overexpression leads to an increase in vascular endothelial cell number. Mech. Dev. 1997;66:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas P. Q., Brown A., Beddington R. S. Hex: a homeobox gene revealing peri-implantation asymmetry in the mouse embryo and an early transient marker of endothelial cell precursors. Development. 1998;125:85–94. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hromas R., Radich J., Collins S. PCR cloning of an orphan homeobox gene (PRH) preferentially expressed in myeloid and liver cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;195:976–983. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mack D. L., Leibowitz D. S., Cooper S., Ramsey H., Broxmeyer H. E., Hromas R. Down-regulation of the myeloid homeobox protein Hex is essential for normal T-cell development. Immunology. 2002;107:444–451. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01523.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bedford F. K., Ashworth A., Enver T., Wiedemann L. M. HEX: a novel homeobox gene expressed during haematopoiesis and conserved between mouse and human. Nucleic Acids. Res. 1993;21:1245–1249. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.5.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manfioletti G., Gattei V., Buratti E., Rustighi A., De Iuliis A., Aldinucci D., Goodwin G. H., Pinto A. Differential expression of a novel proline-rich homeobox gene (Prh) in human hematolymphopoietic cells. Blood. 1995;85:1237–1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bogue C. W., Ganea G. R., Sturm E., Ianucci R., Jacobs H. C. Hex expression suggests a role in the development and function of organs derived from foregut endoderm. Dev. Dyn. 2000;219:84–89. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1028>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jayaraman P., Frampton J., Goodwin G. The homeodomain protein PRH influences the differentiation of haematopoietic cells. Leuk. Res. 2000;24:1023–1031. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(00)00072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Topcu Z., Mack D. L., Hromas R. A., Borden K. L. The promyelocytic leukemia protein PML interacts with the proline-rich homeodomain protein PRH: a RING may link hematopoiesis and growth control. Oncogene. 1999;18:7091–7100. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakagawa T., Abe M., Yamazaki T., Miyashita H., Niwa H., Kokubun S., Sato Y. HEX acts as a negative regulator of angiogenesis by modulating the expression of angiogenesis-related gene in endothelial cells in vitro. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003;23:231–237. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000052670.55321.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Obinata A., Akimoto Y., Omoto Y., Hirano H. Expression of Hex homeobox gene during skin development: increase in epidermal cell proliferation by transfecting the Hex to the dermis. Dev. Growth Differ. 2002;44:281–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.2002.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.George A., Morse H. C., III, Justice M. J. The homeobox gene Hex induces T-cell-derived lymphomas when overexpressed in hematopoietic precursor cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:6764–6773. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Topisirovic I., Guzman M. L., McConnell M. J., Licht J. D., Culjkovic B., Neering S. J., Jordan C. T., Borden K. L. Aberrant eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-dependent mRNA transport impedes hematopoietic differentiation and contributes to leukemogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:8992–9002. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.8992-9002.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jankovic D., Gorello P., Liu T., Ehret S., La Starza R., Desjobert C., Baty M., Brutsche M., Jayaraman P.-S., Santoro A., et al. Leukemogenic mechanisms and targets of a NUP98/HHEX fusion in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Blood. 2008;111:5672–5682. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-108175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bess K. L., Swingler T. E., Rivett J., Gaston K., Jayaraman P.-S. The transcriptional repressor protein PRH interacts with the proteasome. Biochem. J. 2003;374:667–675. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soufi A., Gaston K., Jayaraman P.-S. Purification and characterisation of the PRH homeodomain: removal of the N-terminal domain of PRH increases the PRH homeodomain–DNA interaction. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2006;39:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kasamatsu S., Sato A., Yamamoto T., Keng V. W., Yoshida H., Yamazaki Y., Shimoda M., Miyazaki J., Noguchi T. Identification of the transactivating region of the homeodomain protein, hex. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 2004;135:217–223. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvh025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Courey A. J., Jia S. Transcriptional repression: the long and the short of it. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2786–2796. doi: 10.1101/gad.939601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dasen J. S., Barbera J. P., Herman T. S., Connell S. O., Olson L., Ju B., Tollkuhn J., Baek S. H., Rose D. W., Rosenfeld M. G. Temporal regulation of a paired-like homeodomain repressor/TLE corepressor complex and a related activator is required for pituitary organogenesis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3193–3207. doi: 10.1101/gad.932601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dehni G., Liu Y., Husain J., Stifani S. TLE expression correlates with mouse embryonic segmentation, neurogenesis, and epithelial determination. Mech. Dev. 1995;53:369–381. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eastman Q., Grosschedl R. Regulation of LEF-1/TCF transcription factors by Wnt and other signals. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1999;11:233–240. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levanon D., Goldstein R. E., Bernstein Y., Tang H., Goldenberg D., Stifani S., Paroush Z., Groner Y. Transcriptional repression by AML1 and LEF-1 is mediated by the TLE/Groucho corepressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:11590–11595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen G., Fernandez J., Mische S., Courey A. J. A functional interaction between the histone deacetylase Rpd3 and the corepressor groucho in Drosophila development. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2218–2230. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.17.2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boddy M. N., Freemont P. S., Borden K. L. The p53-associated protein MDM2 contains a newly characterized zinc-binding domain called the RING finger. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1994;19:198–199. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi C. Y., Kim Y. H., Kwon H. J., Kim Y. The homeodomain protein NK-3 recruits Groucho and a histone deacetylase complex to repress transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:33194–33197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palaparti A., Baratz A., Stifani S. The Groucho/transducin-like enhancer of split transcriptional repressors interact with the genetically defined amino-terminal silencing domain of histone H3. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:26604–26610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen G., Nguyen P. H., Courey A. J. A role for groucho tetramerization in transcriptional repression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:7259–7268. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song H., Hasson P., Paroush Z., Courey A. J. Groucho oligomerization is required for repression in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:4341–4350. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4341-4350.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Husain J., Lo R., Grbavec D., Stifani S. Affinity for the nuclear compartment and expression during cell differentiation implicate phosphorylated Groucho/TLE1 forms of higher molecular mass in nuclear functions. Biochem. J. 1996;317:523–531. doi: 10.1042/bj3170523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nuthall H. N., Joachim K., Palaparti A., Stifani S. A role for cell cycle-regulated phosphorylation in Groucho-mediated transcriptional repression. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:51049–51057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nuthall H. N., Husain J., McLarren K. W., Stifani S. Role for Hes1-induced phosphorylation in Groucho-mediated transcriptional repression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:389–399. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.2.389-399.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eberhard D., Jimenez G., Heavey B., Busslinger M. Transcriptional repression by Pax5 (BSAP) through interaction with corepressors of the Groucho family. EMBO J. 2000;19:2292–2303. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choi C. Y., Kim Y. H., Kim Y. O., Park S. J., Kim E. A., Riemenschneider W., Gajewski K., Schulz R. A., Kim Y. Phosphorylation by the DHIPK2 protein kinase modulates the corepressor activity of Groucho. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:21427–21436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500496200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reya T., Duncan A. W., Ailles L., Domen J., Scherer D. C., Willert K., Hintz L., Nusse R., Weissman I. L. A role for Wnt signalling in self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:409–414. doi: 10.1038/nature01593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brantjes H., Roose J., van de Wetering M., Clevers H. All Tcf HMG box transcription factors interact with Groucho-related co-repressors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1410–1419. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.7.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roose J., Molenaar M., Peterson J., Hurenkamp J., Brantjes H., Moerer P., van de Wetering M., Destree O., Clevers H. The Xenopus Wnt effector XTcf-3 interacts with Groucho-related transcriptional repressors. Nature. 1998;395:608–612. doi: 10.1038/26989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Artavanis-Tsakonas S., Rand M. D., Lake R. J. Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science. 1999;284:770–776. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ohishi K., Katayama N., Shiku H., Varnum-Finney B., Bernstein I. D. Notch signalling in hematopoiesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2003;14:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1084-9521(02)00183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]