Abstract

Recent years have witnessed major upheavals in views about early eukaryotic evolution. One very significant finding was that mitochondria, including hydrogenosomes and the newly discovered mitosomes, are just as ubiquitous and defining among eukaryotes as the nucleus itself. A second important advance concerns the readjustment, still in progress, about phylogenetic relationships among eukaryotic groups and the roughly six new eukaryotic supergroups that are currently at the focus of much attention. From the standpoint of energy metabolism (the biochemical means through which eukaryotes gain their ATP, thereby enabling any and all evolution of other traits), understanding of mitochondria among eukaryotic anaerobes has improved. The mainstream formulations of endosymbiotic theory did not predict the ubiquity of mitochondria among anaerobic eukaryotes, while an alternative hypothesis that specifically addressed the evolutionary origin of energy metabolism among eukaryotic anaerobes did. Those developments in biology have been paralleled by a similar upheaval in the Earth sciences regarding views about the prevalence of oxygen in the oceans during the Proterozoic (the time from ca 2.5 to 0.6 Ga ago). The new model of Proterozoic ocean chemistry indicates that the oceans were anoxic and sulphidic during most of the Proterozoic. Its proponents suggest the underlying geochemical mechanism to entail the weathering of continental sulphides by atmospheric oxygen to sulphate, which was carried into the oceans as sulphate, fuelling marine sulphate reducers (anaerobic, hydrogen sulphide-producing prokaryotes) on a global scale. Taken together, these two mutually compatible developments in biology and geology underscore the evolutionary significance of oxygen-independent ATP-generating pathways in mitochondria, including those of various metazoan groups, as a watermark of the environments within which eukaryotes arose and diversified into their major lineages.

Keywords: mitochondria, hydrogenosomes, mitosomes, anoxic oceans, sulphidic oceans, Canfield oceans

1. Introduction

Ever since biologists accepted the idea that mitochondria arose by endosymbiosis, two hefty assumptions have pervaded thinking about the early evolution of eukaryotes. The first of these is that the origin of mitochondria coincided with, or was possibly causally linked to, the onset of oxygen accumulation in the atmosphere ca 2.3 Ga ago. The second is that the origin of mitochondria marked an evolutionary divide that separated anaerobic eukaryotes, the ones then thought to lack mitochondria, from oxygen-respiring eukaryotes. Both notions stem from the 1970s and probably seemed quite reasonable given what was known at that time about eukaryotic diversity, eukaryotic evolution, the diversity of mitochondria in various eukaryotic lineages and Earth history (Margulis et al. 1976).

But a lot has happened since the 1970s. The discovery of hydrogenosomes (Lindmark & Müller 1973)—the hydrogen- and ATP-producing organelles of many anaerobic eukaryotes—initially had little impact on those mainstream notions, because the evolutionary origin of hydrogenosomes was long viewed as uncertain. Not until the late 1990s did it become clear that hydrogenosomes are anaerobic forms of mitochondria, placing the origin of mitochondria deeper in eukaryotic history than anyone had imagined. Then came the more recent discoveries of very highly reduced forms of mitochondria, mitosomes (Tovar et al. 1999), in those eukaryotic lineages that possessed neither classical mitochondria nor hydrogenosomes, placing the origin of mitochondria as deep in eukaryotic history as any other trait that separates the eukaryotes from the prokaryotes. On top of that came the realization that eukaryotic anaerobes are distributed all across the eukaryotic tree, not just in obscure, restricted or suspectedly primitive groups.

Parallel to those developments in biology, geochemists have been reporting since the mid-1990s that the rise of oxygen in the atmosphere preceded the oxygenation of the oceans by ca 1.7 Ga: the advent of oxygen caused oxidation of continental sulphide deposits to sulphate, leading to anoxic and sulphidic Proterozoic oceans where evolution was taking place, during the time from ca 2.3 to ca 0.6 Ga ago. That was the time (and almost certainly the place) where eukaryotes arose and diversified.

The widespread occurrence of eukaryotic anaerobes in current views of eukaryote phylogeny fits very well with the newer view of Proterozoic ocean chemistry. Together they provide the framework for a fuller understanding of the evolution of energy metabolism in eukaryotes, one in which specialized aerobes, specialized anaerobes and facultative anaerobes all (finally) make sense. The purpose of this paper is to briefly summarize the diversity of energy metabolism in eukaryotes, to consider the widespread occurrence of the anaerobic lifestyle across various eukaryotic lineages, to summarize some of the underlying biochemistry and the involvement of mitochondria therein and to show how well this set of observations fits with what geochemists have been reporting with regard to the very late appearance (ca 580 Myr ago) of sulphide-free and oxygenated oceans (Canfield 1998; Anbar & Knoll 2002; Dietrich et al. 2006; Fike et al. 2006; Canfield et al. 2007).

2. Mitochondria: anaerobic in many lineages

Because this issue is mainly about oxygen, the present paper on eukaryotic anaerobes and their mitochondria might seem altogether out of place. Indeed, when most biologists, biochemists or geochemists hear the term ‘mitochondria’ they think about oxygen, and they might even vaguely recall having heard or read somewhere that oxygen was supposedly the driving force for the origin of mitochondria along the evolutionary path that led to eukaryotes and ultimately to humans. Few readers of this paper will have ever heard that the mitochondria of many eukaryotic lineages function without oxygen. Fewer still will know that the idea that oxygen had anything to do with the origin of mitochondria, though contained in most (but not all) formulations of endosymbiotic theory (Martin et al. 2001), might be just plain wrong or worse, seductively misleading until thought through in full (Lane 2006; Martin 2007). Hence we ask the reader to bear with us in subsequent sections where we report a few observations about anaerobically functioning forms of mitochondria.

Our argument in this paper, condensed to a sentence, will be that ‘nothing in the evolution of eukaryotic anaerobes makes sense except in light of Proterozoic ocean chemistry.’ In order to develop this argument, we need to confront the reader with a few aspects of energy metabolism (ATP synthesis) in eukaryotic anaerobes. For those readers who have heard or read little or anything about anaerobic eukaryotes, that will serve to establish the case that (i) eukaryotic anaerobes do indeed exist, (ii) in some cases something is known about how they produce their ATP and (iii) more often than not, their mitochondria are involved in anaerobic ATP synthesis. Thus we will aim to make it clear to the non-specialist reader that eukaryotic anaerobes occur throughout the full spectrum of eukaryotic lineages, even within the animals. The example of the animals is instructive in that animals are usually not viewed as an early diverging or otherwise primitive lineage of eukaryotes, helping to make the point that anaerobic lineages among eukaryotes are nothing odd or otherwise exceptional. Hence the animals are a good example to start the discussion.

Owing to the interdisciplinary nature of this issue, we will try to keep the text very general in the following sections, avoid technical terms such as enzyme names wherever possible and refer to many reviews. The main evidence behind our argument has been published by others and is summarized in table 1, where reference is provided to the published metabolic maps of anaerobic energy metabolism in eukaryotes from five of the six ‘supergroups’ that are currently at the focus of much attention in newer views of eukaryote phylogeny (Simpson & Roger 2004; Adl et al. 2005; Keeling et al. 2005; Embley & Martin 2006; Parfrey et al. 2006).

Table 1.

Published maps of energy metabolism based on biochemical data and end-product measurements for various eukaryotic anaerobes and facultative anaerobes under anaerobic conditions (see also Fenchel & Finlay 1995). (Higher level classification as in Adl et al. (2005).)

| ‘supergroup’ | group | genus | references |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opisthokonts (animals) | Helminthes | Ascaris lumbricoides | Barrett (1991) |

| Helminthes | Fasciola hepatica | van Hellemond et al. (2003) | |

| Annelids | Arenicola marina | Schöttler & Bennet (1991) | |

| Molluscs | Mytilus edulis | de Zwaan (1991) | |

| Sipunculids | Sipunculus nudus | Grieshaber et al. (1994) | |

| Opisthokonts (fungi) | Chytridiomycetes | Neocallimastix patriciarum | Yarlett et al. (1986) and Yarlett (1994) |

| Piromyces sp. | Boxma et al. (2004) | ||

| Amoebozoa | Entamoebida | Entamoeba histolytica | Reeves (1984) and Müller (2003) |

| Excavata | Parabasalia | Tritrichomonas foetus | Müller (1976, 2003) and Kulda (1999) |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | Kulda (1999) and Müller (2003) | ||

| Diplomonadina | Giardia intestinalis | Müller (2003) | |

| Euglenozoa | Euglena gracilis | Schneider & Betz (1985) | |

| Archaeplastida | Chlorophyta | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | Mus et al. (2007) |

| Chromalveolata | Ciliates | Dasytricha ruminantium | Yarlett et al. (1982) |

| Nyctotherus ovalisa | Boxma et al. (2005) |

Map not shown but end products determined.

Anaerobic and hypoxic (oxygen-poor) environments are replete with eukaryotes (Livingstone 1983; Bryant 1991; Grieshaber et al. 1994; Fenchel & Finlay 1995; Tielens & van Hellemond 1998; Bernhard et al. 2000, 2006; Tielens et al. 2002; Levin 2003; van Hellemond et al. 2003). The basic biochemistry of mitochondrial ATP synthesis in eukaryotes that use oxygen as the terminal acceptor can be found in textbooks. Obligate aerobes like ourselves donate the electrons from glucose oxidation to oxygen, producing water as the main end product of energy metabolism (along with CO2, a ubiquitous end product in eukaryotes). Anaerobic eukaryotes do not use oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor in ATP synthesis; hence they produce end products other than water. How do eukaryotes in anaerobic environments generate ATP without oxygen and what do their mitochondria have to do with it?

3. Animals (opisthokonts)

Among the animals that belong to the eukaryotic supergroup called opisthokonts in newer phylogenetic schemes, many free-living marine invertebrates including various worms, mussels and crustaceans inhabit anaerobic environments or must survive under anaerobic conditions for prolonged periods of time. Their energy metabolism has been summarized in various extensive reviews (de Zwaan 1991; Schöttler & Bennet 1991; Zebe 1991; Grieshaber et al. 1994). The anaerobic energy metabolism of these animals very often entails the excretion of succinate as an end product, whereby succinate is usually accompanied by propionate and acetate, and mixtures thereof are more the rule than the exception (Livingstone 1983; Grieshaber et al. 1994).

The anaerobic ATP-generating biochemistry of various marine invertebrates serves as an example here (Livingstone 1983; de Zwaan 1991; Schöttler & Bennet 1991; Zebe 1991), it closely parallels that characterized for several parasitic worms (Tielens 1994; Tielens et al. 2002; van Hellemond et al. 2003). In anaerobically functioning mitochondria that produce succinate, malate enters the mitochondrion and is converted to fumarate, which serves as the terminal electron acceptor. Fumarate reductase (FRD) donates electrons from glucose oxidation to fumarate, yielding succinate. FRD requires a particular electron donor, rhodoquinone (RQ), that is reduced at complex I (Tielens & van Hellemond 1998; Tielens et al. 2002). Complex I pumps protons out of the matrix into the intermembrane space, allowing ATP synthesis via the mitochondrial ATPase. Succinate can either be excreted as the end product or it can participate in further reactions involving additional ATP gain through substrate-level phosphorylation, in which case two additional end products, acetate and propionate, are produced (de Zwaan 1991; Tielens et al. 2002; van Hellemond et al. 2003).

4. Trichomonads (Excavata)

Trichomonads are anaerobic eukaryotes belonging to the large and diverse group of eukaryotes currently called Excavata, or excavate taxa (Adl et al. 2005). They possess hydrogenosomes that are anaerobic forms of mitochondria that produce molecular hydrogen as an end product of ATP synthesis (Müller 1993; Tachezy 2008). Hydrogenosomes were discovered in the anaerobic flagellate Tritrichomonas foetus (Lindmark & Müller 1973) and were subsequently found among ciliates (Yarlett et al. 1982), chytridiomycete fungi (Yarlett et al. 1986) and amoeboflagellates (Broers et al. 1990). The paradigm for hydrogenosomal metabolism stems from the work on the hydrogenosomes of the parabasalian flagellates Trichomonas vaginalis, the causative agent of sexually transmitted disease in humans, and T. foetus (Müller 1988, 1993, 2003, 2007).

The typical end products of energy metabolism in trichmonad hydrogenosomes are one mol each of H2, CO2 and acetate along with one mol of ATP per mol of pyruvate that enters the organelle (Steinbüchel & Müller 1986). ATP is synthesized in hydrogenosomes from ADP and Pi (inorganic phosphate) during the conversion of succinyl-CoA to succinate via substrate-level phosphorylation. The enzyme involved, succinate thiokinase (STK, also called succinyl-CoA synthase), is a citric acid cycle enzyme (Dacks et al. 2006). The acetate-generating enzyme of hydrogenosomes, called ASCT (acetate:succinate CoA transferase), was originally described from Trichomonas (Lindmark 1976) and was only recently characterized at the molecular level (van Grinsven et al. 2008). It is distinct from the ASCT enzyme that generates acetate as an end product in trypanosome mitochondria (van Hellemond et al. 1998; van Weelden et al. 2005). Trichomonad hydrogenosomes contain components derived from complex I of the mitochondrial respiratory chain that help to maintain redox balance by reoxidizing NADH from the malic enzyme reaction (Hrdy et al. 2004).

Trichomonad hydrogenosomes contain two enzymes that were once thought to be specific to hydrogensosomes and anaerobes—pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase (PFO) and iron-only hydrogenase ([Fe]-HYD)—the latter being the enzyme that produces H2. More recent work has shown, however, that both enzymes occur in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Atteia et al. 2006; Mus et al. 2007), an organism that would typically be seen as possessing normal mitochondria. Both enzymes also occur in eukaryotes that were once thought to lack mitochondria altogether, such as Giardia lamblia (Lloyd et al. 2002; Embley et al. 2003; Tovar et al. 2003) or Trimastix pyriformis (Hampl et al. 2008). PFO also occurs in Euglena gracilis mitochondria and in the apicomplexan Cryptosporidium parvum, but as a fusion protein that uses NADP+ as the electron acceptor, rather than ferredoxin (Rotte et al. 2001; Nakazawa et al. 2003).

5. Fungi (opisthokonts): hydrogenosomes, denitrification and sulphur reduction

The fungi, like the animals, belong to the opisthokont group. Some chytridiomycete fungi that live in anaerobic environments possess hydrogenosomes. The energy metabolism of representatives from the genus Neocallimastix (Yarlett et al. 1986; Marvin-Sikkema et al. 1993) and Piromyces (Boxma et al. 2004) has been studied. Typical end products for the chytrids are acetate, lactate, hydrogen, ethanol and formate (Mountfort & Orpin 1994; Boxma et al. 2004). The production of formate is a main difference relative to trichomonads (Mountfort & Orpin 1994), which entails the activity of pyruvate:formate lyase (PFL). Also, chytrids produce ethanol from acetyl-CoA by a bifunctional aldehyde/alcohol dehydrogenase (ADHE). The presence of PFL and ADHE distinguish chytrids from trichomonads, but both enzymes also occur in Chlamydomonas (Atteia et al. 2006; Mus et al. 2007), while ADHE is also found in a colourless relative of Chlamydomonas, Polytomella (Atteia et al. 2003). ATP is thought to be generated in fungal hydrogenosomes by the same acetate-producing STK–ASCT route as in parabasalids, and acetate is a major end product (Boxma et al. 2004).

In Fusarium oxysporum, an ascomycete fungus, an interesting anaerobic respiratory pathway of ATP synthesis occurs, denitrification (Kobayashi et al. 1996; Tsuruta et al. 1998; Morozkina & Kurakov 2007), which has also been reported for benthic foraminifera (Risgaard-Petersen et al. 2006). In Fusarium, denitrification involves mitochondria and entails the oxidation of reduced carbon sources, such as ethanol, to acetate with the deposition of the electrons onto nitrate to generate N2O or NH3, depending upon growth conditions (Zhou et al. 2002; Takaya et al. 2003; Abe et al. 2007). Recently, Abe et al. (2007) showed that Fusarium will grow under anaerobic conditions on a variety of reduced carbon sources using elemental sulphur, S8, as the terminal electron acceptor, generating H2S as the reduced end product in a 2 : 1 molar ratio relative to acetate. The use of elemental sulphur as a terminal electron acceptor is unique among eukaryotes studied so far.

6. Other eukaryotes with hydrogenosomes

The ciliates belong to a third major eukaryotic group, the ‘chromalveolates’. Several lineages of anaerobic ciliates possess hydrogenosomes (van Bruggen et al. 1983; Ellis et al. 1991; Fenchel & Finlay 1995), and the hydrogenosome-containing lineages are dispersed across the phylogenetic diversity of the group (Embley et al. 1995). Major metabolic end products measured for the anaerobic ciliate Trimyema compressa included acetate, lactate, ethanol, formate and hydrogen along with traces of succinate (Goosen et al. 1990). The biochemistry and ecology of the rumen ciliates Dasytricha ruminantium and Isotricha spp. was reviewed by Williams (1986).

One hydrogenosome-bearing ciliate Nyctotherus ovalis that inhabits the hindgut of the cockroaches (van Hoek et al. 1998) attained considerable notoriety of late for being the only organism known so far whose hydrogenosomes still possesses a genome (Boxma et al. 2005). Features of this mitochondrial genome, such as coding for respiratory chain components, together with hydrogen production and biochemical characteristics, indicate that the N. ovalis hydrogenosome is an intermediate organelle type between typical mitochondria and typical hydrogenosomes (Boxma et al. 2005). The major metabolic end products of Nyctotherus—acetate, lactate, succinate and ethanol (Boxma et al. 2005)—suggest a means of ATP synthesis via substrate-level phosphorylation as is observed for chytrid and trichomonad hydrogenosomes.

The free-living anaerobic amoeboflagellate Psalteriomonas lanterna (Broers et al. 1990) belongs to a group of eukaryotes called heteroloboseans, which are, like the trichomonads, the members of the Excavata. The presence of methanogenic endosymbionts within P. lanterna (Broers et al. 1990) serves as a positive bioassay that the organelles are producing hydrogen (Embley & Finlay 1994). Two additional heteroloboseans living in anoxic environments were suggested to possess hydrogenosomes: Monopylocystis visvesvarai and Sawyeria marylandensis (O'Kelly et al. 2003). In addition to those mentioned so far, several other eukaryotic groups are currently suspected to possess hydrogenosomes (Barberà et al. 2007).

The foraminifera belong to the supergroup Rhizaria and are common inhabitants of anoxic sediments (Bernhard & Alve 1996; Bernhard et al. 2000, 2006) but it is not yet known what they are doing biochemically. Importantly, environmental sequences from anoxic habitats continue to reveal the presence of diverse eukaryotes that thrive anaerobically, but cluster phylogenetically within known groups that also contain aerobic forms (Takishita et al. 2007).

7. Groups with mitosomes

Mitosomes are the most highly reduced forms of mitochondria known. They were discovered independently by Mai et al. (1999) and Tovar et al. (1999) in the human intestinal parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Mai et al. called the organelle a crypton, but the name suggested by Tovar et al. has stuck. They are smaller than mitochondria or hydrogenosomes and have been subsequently found among microsporidia (Williams et al. 2002), in Giardia (Tovar et al. 2003), with the list of organisms having previously overlooked forms of mitochondria growing rapidly (van der Giezen & Tovar 2005; van der Giezen et al. 2005; Barberà et al. 2007; Tovar 2007; Hampl et al. 2008; Tachezy 2008). Although both hydrogenosomes and mitosomes are mitochondrion-derived organelles (see Tachezy 2008), there is one important difference between them—mitosomes appear to have no direct involvement in ATP synthesis. In some organisms, like Giardia (Tovar et al. 2003), a member of the excavate taxa, and the microsporidian Encephalitozoon cuniculi (Goldberg et al. 2008), a member of the opisthokonts, mitosomes are involved in the assembly of iron–sulphur clusters (Tachezy & Dolezal 2007).

In two biochemically well-studied taxa that possess mitosomes, Entamoeba (Reeves et al. 1977; Reeves 1984) and Giardia, the enzymes of energy metabolism are localized to the cytosol (Müller 2003). The main end products are acetate and ethanol (Müller 1988), although Giardia can also produce hydrogen under highly anoxic conditions (Lloyd et al. 2002). The enzymes involved in the end product formation are PFO (Townson et al. 1996), ADHE (Sanchez 1998) and acetyl-CoA synthase (ADP forming; ACS-ADP; Sanchez & Müller 1996; Sanchez et al. 2000). AHDE allows electrons from glucose oxidation to be excreted as ethanol while ACS-ADP yields ATP through the substrate-level phosphorylation. In Entamoeba, ethanol can also be produced via two additional alcohol dehydrogenases, ADH1 and ADH3 (Kumar et al. 1992; Bruchhaus & Tannich 1994; Rodríguez et al. 1996).

8. Two facultative anaerobes that produce oxygen

Chlamydomonas belongs to the group of eukaryotes bearing primary plastids, called Archaeplastida in newer schemes (Adl et al. 2005). It provides an example of a generalist facultative anaerobe among eukaryotes. When grown aerobically, C. reinhardtii, a typical soil inhabitant, respires oxygen with a normal manifestation of oxidative decarboxylation via pyruvate dehydrogenase and oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria (Cardol et al. 2005). But when grown anaerobically, it rapidly expresses PFO, PFL, [Fe]-Hyd, ADHE, acetate kinase and phosphotransacetylase and produces acetate, formate, ethanol and hydrogen as major end products (Mus et al. 2007). Chlamydomonas thus expresses many of the enzymes mentioned above that were once thought to be specific to anaerobic eukaryotes lacking typical mitochondria.

Another facultative anaerobe is E. gracilis that belongs to the Excavata. Euglena has secondary plastids and can produce oxygen, which it can respire using a slightly modified citric acid cycle (Green et al. 2000). In Euglena grown under anaerobic conditions, acetyl-CoA serves as the terminal electron acceptor for the production of an unusual end product: wax esters (Inui et al. 1982; Tucci et al. 2007). In this wax ester fermentation, PFO is expressed but as a fusion protein (Rotte et al. 2001; Nakazawa et al. 2003), and a trans-2-enoyl-CoA reductase (NADPH dependent) circumvents the reversal of an O2-dependent step in β-oxidation (Hoffmeister et al. 2005; Tucci & Martin 2007). Similar to the situation in anaerobic mitochondria of metazoa, Euglena's wax ester fermentation involves mitochondrial fumarate reduction, and thus uses RQ (Hoffmeister et al. 2004) for the synthesis of propionyl-CoA (Schneider & Betz 1985) via the same route that the mitochondria of anaerobic animals use to excrete propionate.

The presence and use of typical components of anaerobic energy metabolism in two distantly related eukaryotes, Chlamydomonas (Archaeplastida group) and Euglena (excavate group), which both not only consume but also produce oxygen in the light, indicate that there is no evolutionary divide between aerobic and anaerobic eukaryotes. The divide is primarily one of ecological preferences, not of evolutionary wherewithal.

9. All eukaryotes, in comparison with a single prokaryote

The pathways summarized in the previous sections might appear, at first sight, to provide evidence for diversity in energy metabolism among eukaryotes, but in fact quite the opposite is true. What eukaryotes have is a dramatic lack of diversity in energy metabolism in comparison with prokaryotes, even in comparison with a single prokaryote. The biochemical machinery that anaerobic eukaryotes use for energy metabolism involves a comparatively skimpy handful of enzymes, the occurrences of which are by no means restricted to individual groups. The same few enzymatic components occur over and over again in various independent lineages, sometimes in new combinations, and with minimal variation on a theme in comparison with prokaryotes.

The point is this: the whole spectrum of eukaryotes encompasses less energy metabolic diversity than can be found in one individual generalist purple non-sulphur bacterium (α-proteobacterium), the group from which mitochondria arose. That statement can be substantiated with the example of species, such as Rhodospirillum rubrum or Rhodobacter capsulatus, where aerobic respiration (Bauer & Bird 1996; Aklujkar et al. 2005) occurs, where anaerobic respiration and fermentations with the same spectrum of end products as is found among eukaryotes during anaerobic heterotrophy occur (Schultz & Weaver 1982) and where FRD and RQ occur (Hiraishi 1988). But on top of that, these individual purple non-sulphur bacteria are also capable of photolithoautotrophy (Wang et al. 1993; Tabita et al. 2007), photoheterotrophy (Berg et al. 2000), dimethylsulphoxide respiration (Saeki & Kumagai 1998) or growth on carbon monoxide (Kerby et al. 1995), to name a few of the possibilities, let alone nitrogen fixation in the light or in the dark (Saeki & Kumagai 1998). Looking beyond a bacterium at the literally hundreds of different redox couples that prokaryotes can harness for their ATP synthesis (Amend & Shock 2001) helps to underscore the point that eukaryotes do not boast diversity in energy metabolism, they lack it—and the diversity they have is evolutionarily linked to the mitochondrion.

The significance of that point, in our view, is this: diversity in energy metabolism among eukaryotes is an extremely narrow sample of prokaryotic diversity about one genome's worth at best. The narrowness, not the breadth, of biochemical diversity that underpins energy metabolism in eukaryotes is the remarkable aspect. It suggests, in our view, two things. First, it clearly suggests that eukaryotes have not undergone levels of lateral gene transfer to the extent that shapes the contours of metabolic and genomic diversities among prokaryotes (Dagan & Martin 2007; Doolittle & Bapteste 2007; Shi & Falkowski 2008). Second, the narrow sample of prokaryote gene diversity for energy metabolism bears the distinct imprint, in our view, of endosymbiosis through single acquisition. As the simplest alternative, that single acquisition was via the mitochondrial endosymbiont, as suggested in the hydrogen hypothesis (Martin & Müller 1998). Although the hydrogen hypothesis has many outspoken critics (Cavalier-Smith 2002; Kurland et al. 2006; Margulis et al. 2006; de Duve 2007), it is still the only articulated version of endosymbiotic theory that simultaneously (i) directly accounts for the common ancestry of mitochondria, hydrogenosomes and mitosomes, (ii) predicted the ubiquity of mitochondria among all eukaryotes, (iii) does not entail the assumption that primitively amitochondriate eukaryotes (Archezoa) ever existed and (iv) directly accounts for the evolutionary interleaving of aerobic and anaerobic eukaryotic lineages by virtue of the facultatively anaerobic state inferred for the mitochondrion-bearing ancestor of eukaryotes. In particular, the common ancestry of mitochondria and hydrogenosomes and the wide phylogenetic distribution of eukaryotic anaerobes are issues that critics of the hydrogen hypothesis, who tend to focus their attention on oxygen, generally fail to address. Substantial evidence for the common ancestry of mitochondria, hydrogenosomes and mitosomes is compiled in Martin & Müller (2007) and Tachezy (2008).

10. Anoxic is often sulphidic: eukaryotes in such environments

Modern anoxic marine environments very often exhibit high concentrations of sulphide, H2S or HS− that usually stems from biological sulphate reduction (BSR). The physiology of animals that inhabit sulphidic environments has been reviewed by Grieshaber & Völkel (1998). Deep-sea hydrothermal vents can harbour rich eukaryotic fauna in the presence of up to 0.3 mM sulphide (Van Dover 2000). Various invertebrates, for example, the lugworm Arenicola marina or the ribbed mussel Geukensia demissa, inhabit sulphidic marine sediments where sulphide concentrations can reach 3 μM to 2 mM (Fenchel & Riedl 1970; Völkel & Grieshaber 1992; Völkel et al. 1995) or even up to 8 mM (Lee et al. 1996).

Animals that live in sulphidic environments are dependent upon means to deal with sulphide that inhibits the mitochondrial respiratory chain at cytochrome c oxidase. Many species of mussels simply close their shells in response to sulphide exposure (Grieshaber & Völkel 1998). The oligochaete Tubificoides benedii precipitates FeS in the outer mucous layer, making the animals black (Dubilier et al. 1995). Some worms harbour ectosymbiotic bacteria on their body surface that oxidize sulphide as an energy source (Oeschger & Schmaljohann 1988; Oeschger & Janssen 1991). The gutless oligochaete worm Olavius algarvensis hosts sulphide-oxidizing bacterial symbionts that functionally replace the digestive tract (Dubilier et al. 2001) and possesses extracellular haemoglobins that bind and transport both oxygen and sulphide (Arp et al. 1985; Zal et al. 1998).

The lugworm Arenicola and the mussel Geukensia inhabit sulphidic environments (marine sediments) but host no intracellular endosymbionts; these animals oxidize sulphide themselves, producing thiosulphate (Völkel & Grieshaber 1992; Doeller et al. 2001). In Geukensia, sulphide oxidation occurs in gill mitochondria and is directly linked to ATP synthesis: sulphide-supported oxygen consumption matches the energy demand of ciliary beating (Doeller et al. 2001). In these mitochondria, the electrons for ATP synthesis via the respiratory chain thus stem from an inorganic donor (sulphide). In Arenicola, sulphide oxidation also occurs in mitochondria (Völkel & Grieshaber 1994). The sulphide-oxidizing enzyme of Arenicola, sulphide:quinone reductase (SQR), was recently characterized (Theissen & Martin 2008). Although the in vivo acceptor of the suspected cysteinyl persulphide reaction intermediate is not yet known, nor is the enzyme that generates the end product thiosulphate, the active Arenicola SQR reduces quinones with electrons from HS−, as expected on the basis of known prokaryotic homologues (Schütz et al. 1997), and shares catalytically important residues with the Rhodobacter SQR enzyme (Theissen & Martin 2008). Sulphide oxidation has been shown for vertebrate mitochondria (Yong & Searcy 2001) and for ciliates (Searcy 2006). SQR homologues show a very widespread occurrence among eukaryotic genomes, including human (Theissen et al. 2003). Very little information is available about sulphide metabolism in anaerobic protists, although many do inhabit sulphidic environments (Finlay et al. 1991; Bernhard et al. 2006).

The possible significance of H2S in early eukaryotic evolution has long been discussed, both in the context of mitochondrial origins (Searcy & Lee 1998) and in other contexts (Margulis et al. 2006). Curiously, H2S has been recently found to prolong lifespan in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (Miller & Roth 2007) and has been identified as an endogenously produced gaseous second messenger that, not unlike NO, modulates neurological (Abe & Kimura 1996) and cardiovascular functions in vertebrates (Elrod et al. 2007). One cannot help but wonder whether the role of H2S (and NO) in modulating the transport of oxygen to vertebrate cells might be a molecular relict from our not-so-distant and rather sulphidic past. How distant, and how sulphidic, are the topics of the next section.

11. In light of Proterozoic ocean chemistry

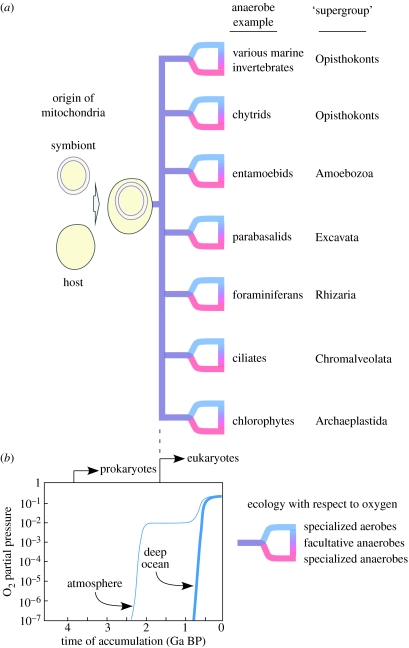

The foregoing passages have served to establish the points that anaerobic energy metabolism in eukaryotes is widespread across lineages (figure 1a) that (i) mitochondria are more often than not integral to the anaerobic lifestyle, (ii) very few components are involved in anaerobic energy metabolism among eukaryotes in comparison with prokaryotes, (iii) the diversity of energy metabolism in eukaryotes as a group falls short of that which can be found in an individual α-proteobacterium and (iv) various eukaryotes have the ability to deal with sulphide, sometimes by virtue of their mitochondria. Keeping that small forest of observations in focus and without getting lost among individual gene trees, we now ask: can we make sense of the anaerobic lifestyle among eukaryotes in terms of ecological history on Earth?

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic distribution of anaerobes among the six ‘supergroups’ currently considered in higher level eukaryotic phylogeny in relation to (b) current views about the timing of ocean oxygenation (redrawn with kind permission from Dietrich et al. 2006). Figure (a) embraces the classification of Adl et al. (2005) and avoids any statement about the position of the root or the possible branching order for those groups; for the purposes of this paper, the position of the root and the branching order are irrelevant because anaerobes occur in all of the supergroups. Energy metabolism for the examples shown are discussed in the text, with the exception of foraminiferans that inhabit anaerobic environments (Bernhard et al. 2006), where little information about energy metabolism is available. It schematically indicates the origin of mitochondria from a symbiosis of a eubacterium with an archaebacterial host (Pisani et al. 2007). For a discussion of whence the prokaryotes arose based on energy metabolic considerations, see Martin & Russell (2007). The age of eukaryotes indicated (ca 1.5 Ga ago) is based on Javaux et al. (2001). The dotted line linking (a) and (b) schematically links the evidence for the earliest eukaryotes and the diversification of major groups to the timing of oxygen accumulation in the oceans (see text). The specialization to aerobic and anaerobic lifestyles from a facultatively anaerobic ancestral state (Martin & Müller 1998) is indicated and schematically shown to temporally correspond with the end of anoxic and sulphidic Proterozoic oceans (see text).

The answer is yes, but to simplify matters a bit, it is better to view it from two polarized and opposing perspectives: (i) the traditional view of oxygen in Earth history that was present until the mid-1990s and (ii) the newer view of Proterozoic ocean chemistry that has emerged since the mid-1990s.

Under the traditional view, present at the time when Lynn Margulis was breathing new life into endosymbiotic theory against much fierce resistance, the early Earth was seen as devoid of O2, with atmospheric O2 stemming from photosynthesis accumulating in the atmosphere ca 2–2.3 Ga ago as evidenced by the disappearance of particular uranium minerals and the appearance of red beds (iron oxidized on continents) at that time (Holland & Beukes 1990; Kasting 1993). An important aspect of that model was that the transition from anoxic oceans to oxic oceans occurred in a very narrow window of time (less than 100 Myr) and coincided temporally with the appearance of atmospheric O2 (Kasting 1993). Under that view, the oceans were chemically much like today's (oxic through and through) for approximately the last 2 Ga. That is not a very detailed account from the geological perspective, but it is the account and level of detail that most (not all) biologists are familiar with in 2008. Because the oceans were where eukaryotic evolution was taking place and because mitochondria were thought to be all about oxygen, anaerobes only fit on the evolutionary map if they lacked mitochondria, and the anaerobic mitochondria of the animals made no evolutionary sense whatsoever, other than as some late and evolutionarily insignificant adaptation to anaerobic habitats. Without citing anyone, this is the underlying message in many shelves of literature about the evolutionary position of eukaryotic anaerobes under the traditional view of ocean oxygen history. The same message, often implicit or subliminal, persists into modern papers on the topic, sometimes with a label of the sorts ‘aerobic mitochondriate ancestor’ or with causal links suggested between the origin of mitochondria and an ‘oxygen catastrophe’. It is true that under the traditional view of oxic marine environments for the last 2 Ga, the widespread occurrence of eukaryotic anaerobes that we know today from many different lineages, and always possessing the same enzymatic machinery or minor variations thereof, make no evolutionary sense at all. That leads to a relatively simple crossroads in evolutionary thinking: either the eukaryotic anaerobes are indeed an insignificant and uninterpretable curiosity or maybe the traditional geochemical model and traditional views on the origin of eukaryotes and their mitochondria embedded therein are off the mark. That brings us to the dénouement.

In the mid-1990s, at the same time as biologists were observing that some hydrogenosomes might be mitochondria on the basis of newer data (Horner et al. 1996), geochemists started rethinking the traditional model of Proterozoic ocean chemistry, also on the basis of newer data (Logan et al. 1995; Canfield 1998). The new model of Proterozoic ocean chemistry departs from the old in that there is a significant lag of well over a billion years between the time that oxygen started accumulating in the atmosphere and the time that the oceans were fully oxidized (figure 1b). In the new model, designated here as ‘sulphidic oceans’ for convenience, the ancient Earth was devoid of O2, O2 stems from photosynthesis and O2 started accumulating in the atmosphere ca 2.3 Ga ago, as in the traditional view. But then comes a big departure. The O2 that was accumulating in the atmosphere began oxidizing continental sulphide deposits via weathering ca 2.3 Ga ago, carrying very substantial amounts of sulphate into the oceans, providing the substrate required for sulphate-reducing prokaryotes, hence marine BSR (Anbar & Knoll 2002; Poulton et al. 2004). Marine BSR became a globally significant process, as evidenced by the sedimentary sulphur isotope record (Canfield et al. 2000; Anbar & Knoll 2002; Johnston et al. 2005). Marine BSR produces marine sulphide, lots and lots of it, and that sulphide means that the oceans were not only sulphidic but also anoxic, both for chemical reasons and because sulphate reducers are strict anaerobes. Although the photic zone (the upper 200 m or so) was producing oxygen during that time, below the photic zone, the oceans were anoxic and sulphidic (Logan et al. 1995; Hurtgen 2003; Shen et al. 2003; Arnold et al. 2004; Brocks et al. 2005). That anoxic and sulphidic conditions, sometimes called Canfield oceans or the intermediate oxidation state, remained more or less stable until ca 600 Myr ago, when the deep ocean water also became oxic sulphidic oceans came to an end and the oceans started to look, geochemically speaking, much like they do today (Dietrich et al. 2006). Two independent reports provided evidence indicating that the end of anoxic sulphidic oceans occurred only ca 580 Myr ago, at the same time as the first animal macrofossils appear in the geological record (Fike et al. 2006; Canfield et al. 2007), one eminently sensible interpretation being that oxygenation of the oceans allowed pre-existing and diversified animal lineages to increase in size (Shen et al. 2008).

In a model of Proterozoic ocean chemistry entailing anoxic oceans between ca 2.3 and ca 0.58 Ga ago, the anaerobic eukaryotes finally make sense and are furthermore significant in the larger picture of Earth history. The eukaryotes arose more than 1.4 Ga ago (Javaux et al. 2001) and had diversified into at least some major lineages (the plants) by 1.2 Ga ago (Butterfield 2000). That occurred in anoxic and sulphidic oceans, hence the widespread occurrence of anaerobic energy metabolism (and sulphide metabolism) among eukaryotes no longer is a curious puzzle, nor does it require some kind of special explanation. The broad phylogenetic distribution of a uniform and recurrently conserved energy metabolic repertoire among anaerobic eukaryotes no longer has to be explained away as some adaptation to anaerobic niches from an assumed aerobic-specialized ancestral state. In many different lineages, the anaerobic lifestyle in eukaryotes can be readily understood as a direct holdover among diversified descendants of a kingdom's anaerobic youth. The new model of Proterozoic ocean chemistry and models for eukaryote origins that accommodate the ubiquity of mitochondriate eukaryotes in anaerobic and sulphidic habitats fit together about as well as two independently developed concepts about the intermediate history of Earth and life possibly could.

12. Conclusion

The presence of mitochondria in the common ancestor of all eukaryotes, the latter's ability to thrive in anaerobic environments using biochemistry germane to the organelle, a facultatively anaerobic lifestyle for the mitochondrial symbiont and many independent specializations among eukaryotic lineages to the strictly aerobic and strictly anaerobic lifestyle from the facultatively anaerobic ancestral state are suggestions that were put forward in a hypothesis designed to account for the origin of energy metabolism among eukaryotes (Martin & Müller 1998). Those predictions have fared well so far. Biologists have yet to agree on what the host was that acquired the mitochondrion (Pisani et al. 2007) or whether the nucleus arose before or after the acquisition of mitochondria (Martin & Koonin 2006). But our understanding of the evolutionary position of eukaryotic anaerobes and the evolutionary significance of mitochondria in eukaryotic anaerobes has improved. The ubiquity of mitochondria among eukaryotic anaerobes is now well accepted and underscores the significance of endosymbiosis in eukaryote origins (Lane 2006).

It is just and fitting that obligate aerobes like ourselves are now best understood as oddballs in the larger evolutionary picture of Earth's oxygen history: specialized adaptations to recently colonized, strictly aerobic terrestrial environments above soil level and in permanent contact with the atmosphere. This kind of specialized aerobic lifestyle as is found in textbooks, which mainly present the mitochondrial biochemistry of humans and rats, is still viewed by some biologists as the ancestral state among eukaryotes. In that view, anaerobes can only be interpreted as some kind of evolutionarily insignificant specialization to (implicitly) late-arising anaerobic environments (Cavalier-Smith 2004; Gill et al. 2007). However, eukaryotes that thrive in contemporary anaerobic aquatic environments (Bernhard et al. 2000; Levin 2003; Takishita et al. 2007) can hardly be the result of recent ‘adaptations’ to anaerobic ‘niches’, because such habitats have an uninterrupted history that is as at least old as, and probably older than, eukaryotes themselves that arose in anaerobic and sulphidic oceans. Modern anaerobic and sulphidic marine environments provide a window in time into the ecology of eukaryotic heterotrophs during the Proterozoic. Nothing in the evolution of eukaryotic anaerobes makes sense except in the light of Proterozoic ocean chemistry.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for a postdoctoral stipend (M.M.) and for supporting work in the laboratory (W.M.). Part of this work was completed in the laboratory of Pete Lockhart at Massey University, New Zealand, who was the kind host of W.M. during a Julius von Haast Fellowship of the New Zealand Ministry of Science Research and Technology. We thank Dianne Newman for permission to reproduce a part of a published figure and also Joan Bernhard, Louis Tielens, Katrin Henze, Ursula Theissen, Manfred Grieshaber, Roger Summons, and Nick Lane for many of their helpful discussions.

Footnotes

One contribution of 15 to a Discussion Meeting Issue ‘Photosynthetic and atmospheric evolution’.

Supplementary Material

References

- Abe K, Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:1066–1071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01066.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe T, Hoshino T, Nakamura A, Takaya N. Anaerobic elemental sulfur reduction by fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007;71:2402–2407. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70083. doi:10.1271/bbb.70083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adl S.M, et al. The new higher level classification of eukaryotes with emphasis on the taxonomy of protists. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2005;52:399–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aklujkar M, Prince R.C, Beatty J.T. The puhE gene of Rhodobacter capsulatus is needed for optimal transition from aerobic to photosynthetic growth and encodes a putative negative modulator of bacteriochlorophyll production. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005;437:186–198. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.03.012. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2005.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amend J.P, Shock E.L. Energetics of overall metabolic reactions of thermophilic and hyperthermophilic Archaea and Bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2001;25:175–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00576.x. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00576.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anbar A.D, Knoll A.H. Proterozoic ocean chemistry and evolution: a bioinorganic bridge? Science. 2002;297:1137–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.1069651. doi:10.1126/science.1069651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold G.L, Anbar A.D, Barling J, Lyons T.W. Molybdenum isotope evidence for widespread anoxia in mid-Proterozoic oceans. Science. 2004;304:87–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1091785. doi:10.1126/science.1091785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arp A.J, Childress J.J, Fisher C.R. Blood gas transport in Riftia pachyptila. Bull. Biol. Soc. Wash. 1985;6:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Atteia A, van Lis R, Mendoza-Hernández G, Henze K, Martin W, Riveros-Rosas H, González-Halphen D. Bifunctional aldehyde/alcohol dehydrogenase (ADHE) in chlorophyte algal mitochondria. Plant Mol. Biol. 2003;53:175–188. doi: 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000009274.19340.36. doi:10.1023/B:PLAN.0000009274.19340.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atteia A, van Lis R, Gelius-Dietrich G, Adrait A, Garin J, Joyard J, Rolland N, Martin W. Pyruvate:formate lyase and a novel route of eukaryotic ATP-synthesis in anaerobic Chlamydomonas mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:9909–9918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507862200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M507862200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberà M.J, Ruiz-Trillo I, Leigh J, Hug L.A, Roger A.J. The diversity of mitochondrion-related organelles amongst eukaryotic microbes. In: Martin W.F, Müller M, editors. Origin of mitochondria and hydrogenosomes. Springer; Heidelberg, Germany: 2007. pp. 239–276. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J. Parasitic helminths. In: Bryant C, editor. Metazoan life without oxygen. Chapman and Hall; London, UK: 1991. pp. 146–164. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer C.E, Bird T.H. Regulatory circuits controlling photosynthesis gene expression. Cell. 1996;85:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81074-0. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81074-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg I.A, Krasilnikova E.N, Ivanovsky R.N. Investigation of the dark metabolism of acetate in photoheterotrophically grown cells of Rhodospirillum rubrum. Microbiology. 2000;69:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard J.M, Alve E. Survival, ATP pool, and ultrastructural characterization of benthic foraminifera from Drammensfjord (Norway): response to anoxia. Mar. Micropaleontol. 1996;28:5–17. doi:10.1016/0377-8398(95)00036-4 [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard J.M, Buck K.R, Farmer M.A, Bowser S.S. The Santa Barbara Basin is a symbiosis oasis. Nature. 2000;403:77–80. doi: 10.1038/47476. doi:10.1038/47476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard J.M, Habura A, Bowser S.S. An endobiont-bearing allogromiid from the Santa Barbara Basin: implications for the early diversification of foraminifera. J. Geophys. Res. 2006;111:G03002. doi:10.1029/2005JG000158 [Google Scholar]

- Boxma B, et al. The anaerobic chytridiomycete fungus Piromyces sp. E2 produces ethanol via pyruvate:formate lyase and an alcohol dehydrogenase E. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;51:1389–1399. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03912.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03912.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxma B, et al. An anaerobic mitochondrion that produces hydrogen. Nature. 2005;434:74–79. doi: 10.1038/nature03343. doi:10.1038/nature03343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocks J.J, Love G.D, Summons R.E, Knoll A.H, Logan G.A, Bowden S.A. Biomarker evidence for green and purple sulphur bacteria in a stratified Palaeoproterozoic sea. Nature. 2005;437:866–870. doi: 10.1038/nature04068. doi:10.1038/nature04068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broers C.A, Stumm C.K, Vogels G.D, Brugerolle G. Psalteriomonas lanterna gen. nov., sp. nov., a free-living amoeboflagellate isolated from freshwater anaerobic sediments. Eur. J. Protistol. 1990;25:369–380. doi: 10.1016/S0932-4739(11)80130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruchhaus I, Tannich E. Purification and molecular characterization of the NAD(+)-dependent acetaldehyde/alcohol dehydrogenase from Entamoeba histolytica. Biochem. J. 1994;303:743–748. doi: 10.1042/bj3030743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant C, editor. Metazoan life without oxygen. Chapman and Hall; London, UK: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield N.J. Bangiomorpha pubescens n. gen., n. sp.: implications for the evolution of sex, multicellularity, and the Mesoproterozoic/Neoproterozoic radiation of eukaryotes. Paleobiology. 2000;26:386–404. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0386:BPNGNS>2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Canfield D.E. A new model for Proterozoic ocean chemistry. Nature. 1998;396:450–453. doi:10.1038/24839 [Google Scholar]

- Canfield D.E, Habicht K.S, Thamdrup B. The Archean sulfur cycle and the early history of atmospheric oxygen. Science. 2000;288:658–661. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.658. doi:10.1126/science.288.5466.658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canfield D.E, Poulton S.W, Narbonne G.M. Late-Neoproterozoic deep-ocean oxygenation and the rise of animal life. Science. 2007;315:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.1135013. doi:10.1126/science.1135013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardol P, Gonzalez-Halphen D, Reyes-Prieto A, Baurain D, Matagne R.F, Remacle C. The mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation proteome of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii deduced from the genome sequencing project. Plant Physiol. 2005;137:447–459. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.054148. doi:10.1104/pp.104.054148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smith T. The phagotrophic origin of eukaryotes and phylogenetic classification of Protozoa. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002;52:297–354. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-2-297. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02058-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smith T. Only six kingdoms of life. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2004;271:1251–1262. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2705. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacks J.B, Dyal P.L, Embley T.M, van der Giezen M. Hydrogenosomal succinyl-CoA synthetase from the rumen-dwelling fungus Neocallimastix patriciarum; an energy-producing enzyme of mitochondrial origin. Gene. 2006;373:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.01.012. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2006.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagan T, Martin W. Ancestral genome sizes specify the minimum rate of lateral gene transfer during prokaryote evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:870–875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606318104. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606318104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Duve C. The origin of eukaryotes: a reappraisal. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:395–403. doi: 10.1038/nrg2071. doi:10.1038/nrg2071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zwaan A. Molluscs. In: Bryant C, editor. Metazoan life without oxygen. Chapman and Hall; London, UK: 1991. pp. 186–217. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich L.E, Tice M.M, Newman D.K. The co-evolution of life and Earth. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:R395–R400. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.017. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doeller J.E, Grieshaber M.K, Kraus D.W. Chemolithoheterotrophy in a metazoan tissue: thiosulfate production matches ATP demand in ciliated mussel gills. J. Exp. Biol. 2001;204:3755–3764. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.21.3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle W.F, Bapteste E. Pattern pluralism and the tree of life hypothesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:2043–2049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610699104. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610699104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubilier N, Giere O, Grieshaber M.K. Morphological and ecophysiological adaptations of the marine oligochaete Tubificoides benedii to sulfidic sediments. Am. Zool. 1995;35:163–173. doi:10.1093/icb/35.2.163 [Google Scholar]

- Dubilier N, et al. Endosymbiotic sulphate-reducing and sulphide-oxidizing bacteria in an oligochaete worm. Nature. 2001;411:298–302. doi: 10.1038/35077067. doi:10.1038/35077067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J.E, McIntyre P.S, Saleh M, Williams A.G, Lloyd D. Influence of CO2 and low concentrations of O2 on fermentative metabolism of the rumen ciliate Dasytricha ruminantium. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1991;137:1409–1417. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-6-1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod J.W, et al. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:15 560–15 565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705891104. doi:10.1073/pnas.0705891104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embley T.M, Finlay B.J. The use of small subunit rRNA sequences to unravel the relationships between anaerobic ciliates and their methanogen endosymbionts. Microbiology. 1994;140:225–235. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-2-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embley T.M, Martin W. Eukaryotic evolution, changes and challenges. Nature. 2006;440:623–630. doi: 10.1038/nature04546. doi:10.1038/nature04546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embley T.M, Finlay B.J, Dyal P.L, Hirt R.P, Wilkinson M, Williams A.G. Multiple origins of anaerobic ciliates with hydrogenosomes within the radiation of aerobic ciliates. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1995;262:87–93. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1995.0180. doi:10.1098/rspb.1995.0180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embley T.M, van der Giezen M, Horner D.S, Dyal P.L, Bell S, Foster P.G. Hydrogenosomes, mitochondria and early eukaryotic evolution. IUBMB Life. 2003;55:387–395. doi: 10.1080/15216540310001592834. doi:10.1080/15216540310001592834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenchel T, Finlay B.J. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1995. Ecology and evolution in anoxic worlds. [Google Scholar]

- Fenchel T.M, Riedl R.J. The sulfide system: a new biotic community underneath the oxidized layer of marine sand bottoms. Mar. Biol. 1970;7:255–268. doi:10.1007/BF00367496 [Google Scholar]

- Fike D.A, Grotzinger J.P, Pratt L.M, Summons R.E. Oxidation of the Ediacaran ocean. Nature. 2006;444:744–747. doi: 10.1038/nature05345. doi:10.1038/nature05345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay B.J, Clarke K.J, Vicente E, Miracle M.R. Anaerobic ciliates from a sulfide-rich solution lake in Spain. Eur. J. Protistol. 1991;27:148–159. doi: 10.1016/S0932-4739(11)80337-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill E.E, Diaz-Triviño S, Barberà M.J, Silberman J.D, Stechmann A, Gaston D, Tamas I, Roger A.J. Novel mitochondrion-related organelles in the anaerobic amoeba Mastigamoeba balamuthi. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;66:1306–1320. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05979.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05979.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg A.V, et al. Localization and functionality of microsporidian iron–sulphur cluster assembly proteins. Nature. 2008;452:624–628. doi: 10.1038/nature06606. doi:10.1038/nature06606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosen N.K, van der Drift C, Stumm C.K, Vogels G.D. End products of metabolism in the anaerobic ciliate Trimyema compressum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1990;69:171–175. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04195.x [Google Scholar]

- Green L.S, Li Y, Emerich D.W, Bergersen F.J, Day D.A. Catabolism of α-ketoglutarate by a sucA mutant of Bradyrhizobium japonicum: evidence for an alternative tricarboxylic acid cycle. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:2838–2844. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.10.2838-2844.2000. doi:10.1128/JB.182.10.2838-2844.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieshaber M.K, Völkel S. Animal adaptations for tolerance and exploitation of poisonous sulfide. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 1998;60:30–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.33. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieshaber M.K, Hardewig I, Kreutzer U, Pörtner H.O. Physiological and metabolic responses to hypoxia in invertebrates. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994;125:43–147. doi: 10.1007/BFb0030909. doi:10.1007/BFb0030909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampl V, Silberman J.D, Stechmann A, Diaz-Trivino S, Johnson P.J, Roger A.J. Genetic evidence for a mitochondriate ancestry in the ‘amitochondriate’ flagellate Trimastix pyriformis. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001383. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraishi A. Fumarate reduction systems in members of the family Rhodospirillaceae with different quinone types. Arch. Microbiol. 1988;150:56–60. doi:10.1007/BF00409718 [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmeister M, van der Klei A, Rotte C, van Grinsven K.W, van Hellemond J.J, Henze K, Tielens A.G, Martin W. Euglena gracilis rhodoquinone:ubiquinone ratio and mitochondrial proteome differ under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:22 422–22 429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400913200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M400913200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmeister M, Piotrowski M, Nowitzki U, Martin W. Mitochondrial trans-2-enoyl-CoA reductase of wax ester fermentation from Euglena gracilis defines a new family of enzymes involved in lipid synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:4329–4338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411010200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M411010200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland H, Beukes N. A paleoweathering profile from Griqualand West, South Africa: evidence for a dramatic rise in atmospheric oxygen between 2.2 and 1.9 BYBP. Am. J. Sci. 1990;290:1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner D.S, Hirt R.P, Kilvington S, Lloyd D, Embley T.M. Molecular data suggest an early acquisition of the mitochondrion endosymbiont. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1996;263:1053–1059. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0155. doi:10.1098/rspb.1996.0155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrdy I, Hirt R.P, Dolezal P, Bardonova L, Foster P.G, Tachezy J, Embley T.M. Trichomonas hydrogenosomes contain the NADH dehydrogenase module of mitochondrial complex I. Nature. 2004;432:618–622. doi: 10.1038/nature03149. doi:10.1038/nature03149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtgen M.T. Biogeochemistry: ancient oceans and oxygen. Nature. 2003;423:592–593. doi: 10.1038/423592a. doi:10.1038/423592a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui H, Miyatake K, Nakano Y, Kitaoka S. Wax ester fermentation in Euglena gracilis. FEBS Lett. 1982;150:89–93. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13276. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(82)81310-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javaux E.J, Knoll A.H, Walter M.R. Morphological and ecological complexity in early eukaryotic ecosystems. Nature. 2001;412:66–69. doi: 10.1038/35083562. doi:10.1038/35083562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D.T, Wing B.A, Farquhar J, Kaufman A.J, Strauss H, Lyons T.W, Kah L.C, Canfield D.E. Active microbial sulfur disproportionation in the Mesoproterozoic. Science. 2005;310:1477–1479. doi: 10.1126/science.1117824. doi:10.1126/science.1117824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasting J.F. Earth's early atmosphere. Science. 1993;259:920–926. doi: 10.1126/science.11536547. doi:10.1126/science.11536547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling P.J, Burger G, Durnford D.G, Lang B.F, Lee R.W, Pearlman R.E, Roger A.J, Gray M.W. The tree of eukaryotes. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005;20:670–676. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.09.005. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerby R.L, Ludden P.W, Roberts G.P. Carbon monoxide-dependent growth of Rhodospirillum rubrum. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:2241–2244. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2241-2244.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Matsuo Y, Takimoto A, Suzuki S, Maruo F, Shoun H. Denitrification, a novel type of respiratory metabolism in fungal mitochondrion. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:16 263–16 267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16263. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.27.16263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulda J. Trichomonads, hydrogenosomes and drug resistance. Int. J. Parasitol. 1999;29:199–212. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(98)00155-6. doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(98)00155-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Shen P.S, Descoteaux S, Pohl J, Bailey G, Samuelson J. Cloning and expression of an NADP(+)-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase gene of Entamoeba histolytica. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:10 188–10 192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10188. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.21.10188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurland C.G, Collins L.J, Penny D. Genomics and the irreducible nature of eukaryote cells. Science. 2006;312:1011–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1121674. doi:10.1126/science.1121674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane N. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2006. Power, sex, suicide: mitochondria and the meaning of life. [Google Scholar]

- Lee R.W, Kraus D, Doeller J.E. Sulfide-stimulation of oxygen consumption rate and cytochrome reduction in gills of the estuarine mussel Geukensia demissa. Biol. Bull. 1996;191:421–430. doi: 10.2307/1543015. doi:10.2307/1543015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin L.A. Oxygen minimum zone benthos: adaptation and community response to hypoxia. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. 2003;41:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lindmark D.G. Acetate production in Tritrichomonas foetus. In: Van den Bossche H, editor. Biochemistry of parasites and host–parasite relationships. North-Holland; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 1976. pp. 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lindmark D.G, Müller M. Hydrogenosome, a cytoplasmic organelle of the anaerobic flagellate Tritrichomonas foetus, and its role in pyruvate metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 1973;25:7724–7728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone D.R. Invertebrate and vertebrate pathways of anaerobic metabolism: evolutionary considerations. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 1983;140:27–37. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.140.1.0027 [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd D, Ralphs J.R, Harris J.C. Giardia intestinalis, a eukaryote without hydrogenosomes, produces hydrogen. Microbiology. 2002;148:727–733. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-3-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan G.A, Hayes J.M, Hieshima G.B, Summons R.E. Terminal Proterozoic reorganization of biogeochemical cycles. Nature. 1995;376:53–56. doi: 10.1038/376053a0. doi:10.1038/376053a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai Z.M, Ghosh S, Frisardi M, Rosenthal B, Rogers R, Samuelson J. Hsp60 is targeted to a cryptic mitochondrion-derived organelle (“crypton”) in the microaerophilic protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999;19:2198–2205. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulis L, Walker J.C, Rambler M. Reassessment of roles of oxygen and ultraviolet light in Precambrian evolution. Nature. 1976;264:620–624. doi:10.1038/264620a0 [Google Scholar]

- Margulis L, Chapman M, Guerrero R, Hall J. The last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA): acquisition of cytoskeletal motility from aerotolerant spirochetes in the Proterozoic Eon. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:13 080–13 085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604985103. doi:10.1073/pnas.0604985103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W. Eukaryote and mitochondrial origins: two sides of the same coin and too much ado about oxygen. In: Falkowski P.G, Knoll A.H, editors. Evolution of primary producers in the Sea. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2007. pp. 37–73. [Google Scholar]

- Martin W, Koonin E.V. Introns and the origin of nucleus-cytosol compartmentalization. Nature. 2006;440:41–45. doi: 10.1038/nature04531. doi:10.1038/nature04531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W, Müller M. The hydrogen hypothesis for the first eukaryote. Nature. 1998;392:37–41. doi: 10.1038/32096. doi:10.1038/32096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W, Müller M, editors. Origin of mitochondria and hydrogenosomes. Springer; Heidelberg, Germany: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Martin W, Russell M.J. On the origin of biochemistry at an alkaline hydrothermal vent. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2007;362:1887–1925. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1881. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W, Hoffmeister M, Rotte C, Henze K. An overview of endosymbiotic models for the origins of eukaryotes, their ATP-producing organelles (mitochondria and hydrogenosomes), and their heterotrophic lifestyle. Biol. Chem. 2001;382:1521–1539. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.187. doi:10.1515/BC.2001.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin-Sikkema F.D, Pedro Gomes T.M, Grivet J.P, Gottschal J.C, Prins R.A. Characterization of hydrogenosomes and their role in glucose metabolism of Neocallimastix sp. L2. Arch. Microbiol. 1993;160:388–396. doi: 10.1007/BF00252226. doi:10.1007/BF00252226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D.L, Roth M.B. Hydrogen sulfide increases thermotolerance and lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:20 618–20 622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710191104. doi:10.1073/pnas.0710191104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozkina E.V, Kurakov A.V. Dissimilatory nitrate reduction in fungi under conditions of hypoxia and anoxia: a review. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2007;43:544–549. doi:10.1134/S0003683807050079 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountfort D.O, Orpin C.G. Marcel Dekker Inc; New York, NY: 1994. Anaerobic fungi: biology, ecology and function. [Google Scholar]

- Müller M. Carbohydrate and energy metabolism of Tritrichomonas foetus. In: Van den Bossche H, editor. Biochemistry of parasites and host–parasite relationships. Elsevier/North-Holland; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 1976. pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Müller M. Energy metabolism of protozoa without mitochondria. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 1988;42:465–488. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.002341. doi:10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.002341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M. The hydrogenosome. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1993;139:2879–2889. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-12-2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M. Energy metabolism. Part I: anaerobic protozoa. In: Marr J, editor. Molecular medical parasitology. Academic Press; London, UK: 2003. pp. 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Müller M. The road to hydrogenosomes. In: Martin W.F, Müller M, editors. Origin of mitochondria and hydrogenosomes. Springer; Heidelberg, Germany: 2007. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mus F, Dubini A, Seibert M, Posewitz M.C, Grossman A.R. Anaerobic acclimation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii—Anoxic gene expression, hydrogenase induction, and metabolic pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:25 475–25 486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701415200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M701415200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa M, Takenaka S, Ueda M, Inui H, Nakano Y, Miyatake K. Pyruvate: NADP(+) oxidoreductase is stabilized by its cofactor, thiamin pyrophosphate, in mitochondria of Euglena gracilis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2003;411:183–188. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00749-x. doi:10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00749-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oeschger R, Janssen H.H. Histological studies on Halicryptus spinulosus (Priapulida) with regard to environmental hydrogen sulfide resistance. Hydrobiologia. 1991;222:1–12. doi:10.1007/BF00017494 [Google Scholar]

- Oeschger R, Schmaljohann R. Association of various types of epibacteria with Halicryptus spinulosus (Priapulida) Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1988;48:285–293. doi:10.3354/meps048285 [Google Scholar]

- O'Kelly C.J, Silberman J.D, Amaral Zettler L.A, Nerad T.A, Sogin M.L. Monopylocystis visvesvarai n. gen., n. sp. and Sawyeria marylandensis n. gen., n. sp.: two new amitochondrial heterolobosean amoebae from anoxic environments. Protist. 2003;154:281–290. doi: 10.1078/143446103322166563. doi:10.1078/143446103322166563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfrey L.W, Barbero E, Lasser E, Dunthorn M, Bhattacharya D, Patterson D.J, Katz L.A. Evaluating support for the current classification of eukaryotic diversity. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020220. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani D, Cotton J.A, McInerney J.O. Supertrees disentangle the chimerical origin of eukaryotic genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:1752–1760. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm095. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulton S.W, Fralick P.W, Canfield D.E. The transition to a sulphidic ocean approximately 1.84 billion years ago. Nature. 2004;431:173–177. doi: 10.1038/nature02912. doi:10.1038/nature02912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves R.E. Metabolism of Entamoeba histolytica Schaudin, 1903. Adv. Parasitol. 1984;23:105–142. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves R.E, Warren L.G, Susskind B, Lo H.S. An energy-conserving pyruvate-to-acetate pathway in Entamoeba histolytica, Pyruvate synthase and a new acetate thiokinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1977;252:726–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risgaard-Petersen N, et al. Evidence for complete denitrification in a benthic foraminifer. Nature. 2006;443:93–96. doi: 10.1038/nature05070. doi:10.1038/nature05070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez M.A, Báez-Camargo M, Delgadillo D.M, Orozco E. Cloning and expression of an Entamoeba histolytica NAPD+(−)dependent alcohol dehydrogenase gene. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1996;1306:23–26. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(96)00014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotte C, Stejskal F, Zhu G, Keithly J.S, Martin W. Pyruvate:NADP+ oxidoreductase from the mitochondrion of Euglena gracilis and from the apicomplexan Cryptosporidium parvum: a fusion of pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase and NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2001;18:710–720. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeki K, Kumagai H. The rnf gene products in Rhodobacter capsulatus play an essential role in nitrogen fixation during anaerobic DMSO-dependent growth in the dark. Arch. Microbiol. 1998;169:464–467. doi: 10.1007/s002030050598. doi:10.1007/s002030050598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez L.B. Aldehyde dehydrogenase (CoA-acetylating) and the mechanism of ethanol formation in the amitochondriate protist, Giardia lamblia. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998;354:57–64. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0664. doi:10.1006/abbi.1998.0664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez L.B, Müller M. Purification and characterization of the acetate forming enzyme, acetyl-CoA synthetase (ADP-forming) from the amitochondriate prostist, Giardia lamblia. FEBS Lett. 1996;378:240–244. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01463-2. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(95)01463-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez L.B, Galperin M.Y, Müller M. Acetyl-CoA Synthetase from the Amitochondriate eukaryote Giardia lamblia belongs to the newly recognized superfamily of acyl-CoA synthetases (nucleoside diphosphate-forming) J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:5794–5803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5794. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.8.5794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T, Betz A. Wax ester fermentation in Euglena gracilis T. Factors favouring the synthesis of odd-numbered fatty acids and alcohols. Planta. 1985;166:67–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00397387. doi:10.1007/BF00397387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöttler U, Bennet E.M. Annelids. In: Bryant C, editor. Metazoan life without oxygen. Chapman and Hall; London, UK: 1991. pp. 165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J.E, Weaver P.F. Fermentation and anaerobic respiration by Rhodospirillum rubrum and Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J. Bacteriol. 1982;149:181–190. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.1.181-190.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schütz M, Shahak Y, Padan E, Hauska G. Sulfide quinone reductase from Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:9890–9894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9890. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.15.9890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searcy D.G. Rapid hydrogen sulfide consumption by Tetrahymena pyriformis and its implications for the origin of mitochondria. Eur. J. Protistol. 2006;42:221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2006.06.001. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2006.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searcy D.G, Lee S.H. Sulfur reduction by human erythrocytes. J. Exp. Zool. 1998;282:310–322. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-010x(19981015)282:3<310::aid-jez4>3.0.co;2-p. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(19981015)282:3<310::AID-JEZ4>3.0.CO;2-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Knoll A.H, Walter M.R. Evidence for low sulphate and anoxia in a mid-Proterozoic marine basin. Nature. 2003;423:632–635. doi: 10.1038/nature01651. doi:10.1038/nature01651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen B, Dong L, Xiao S.H, Kowalewski M. The Avalon explosion: evolution of Ediacara morphospace. Science. 2008;319:81–84. doi: 10.1126/science.1150279. doi:10.1126/science.1150279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi T, Falkowski P.G. Genome evolution in cyanobacteria: the stable core and the variable shell. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:2510–2515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711165105. doi:10.1073/pnas.0711165105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson A.G, Roger A.J. The real ‘kingdoms’ of eukaryotes. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:R693–R696. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.038. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbüchel A, Müller M. Anaerobic pyruvate metabolism of Tritrichomonas foetus and Trichomonas vaginalis hydrogenosomes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1986;20:57–65. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(86)90142-8. doi:10.1016/0166-6851(86)90142-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabita F.R, Hanson T.E, Li H, Satagopan S, Singh J, Chan S. Function, structure, and evolution of the RubisCO-Like proteins and their RubisCO homologs. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007;71:576–599. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00015-07. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00015-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachezy J, editor. Hydrogenosomes and mitosomes: mitochondria of anaerobic eukaryotes. Springer; Heidelberg, Germany: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tachezy J, Dolezal P. Iron–sulfur proteins and iron–sulfur cluster assembly in organisms with hydrogenosomes and mitosomes. In: Martin W.F, Müller M, editors. Origin of mitochondria and hydrogenosomes. Springer; Heidelberg, Germany: 2007. pp. 105–134. [Google Scholar]

- Takaya N, Kuwazaki S, Adachi Y, Suzuki S, Kikuchi T, Nakamura H, Shiro Y, Shoun H. Hybrid respiration in the denitrifying mitochondria of Fusarium oxysporum. J. Biochem. 2003;133:461–465. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg060. doi:10.1093/jb/mvg060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takishita K, Tsuchiya M, Kawato M, Oguri K, Kitazato H, Maruyama T. Genetic diversity of microbial eukaryotes in anoxic sediment of the saline meromictic lake Namako-ike (Japan): on the detection of anaerobic or anoxic-tolerant lineages of eukaryotes. Protist. 2007;158:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2006.07.003. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2006.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theissen U, Martin W. Sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase (SQR) from the lugworm Arenicola marina shows cyanide- and thioredoxin-dependent activity. FEBS J. 2008;275:1131–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06273.x. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06273.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theissen U, Hoffmeister M, Grieshaber M, Martin W. Single eubacterial origin of eukaryotic sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase, a mitochondrial enzyme conserved from the early evolution of eukaryotes during anoxic and sulfidic times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003;20:1564–1574. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg174. doi:10.1093/molbev/msg174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tielens A.G. Energy generation in parasitic helminths. Parasitol. Today. 1994;10:346–352. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(94)90245-3. doi:10.1016/0169-4758(94)90245-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tielens A.G, van Hellemond J.J. The electron transport chain in anaerobically functioning eukaryotes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1365:71–78. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00045-0. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(98)00045-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tielens A.G, Rotte C, van Hellemond J.J, Martin W. Mitochondria as we don't know them. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002;27:564–572. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02193-x. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(02)02193-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovar J. Mitosomes of parasitic protozoa: biology and evolutionary significance. In: Martin W.F, Müller M, editors. Origin of mitochondria and hydrogenosomes. Springer; Heidelberg, Germany: 2007. pp. 277–280. [Google Scholar]

- Tovar J, Fischer A, Clark C.G. The mitosome, a novel organelle related to mitochondria in the amitochondrial parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;32:1013–1021. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01414.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]