Abstract

The diversity of life on Earth raises the question of whether it is possible to have a single theoretical description of the quantitative aspects of the organization of metabolism for all organisms. However, similarities between organisms, such as von Bertalanffy's growth curve and Kleiber's law on metabolic rate, suggest that mechanisms that control the uptake and use of metabolites are common to all organisms. These and other widespread empirical patterns in biology should be the ultimate test for any metabolic theory that hopes for generality. The present study (i) collects empirical evidence on growth, stoichiometry, feeding, respiration and energy dissipation and exhibits it as stylized biological facts; (ii) formalizes assumptions and propositions in a metabolic theory that is fully consistent with the Dynamic Energy Budget theory; and (iii) proves that these assumptions and propositions are consistent with the stylized facts.

Keywords: Dynamic Energy Budget theory, metabolic theory, Kleiber's law, von Bertalanffy growth, stoichiometry, growth

1. Introduction

In the literature, two main approaches are followed to obtain insights into metabolic phenomena: (i) the study of the complex set of biochemical reactions occurring at different rates and (ii) the study of the organization of metabolism described by the mass and energy flows inside the organisms. We believe that the modelling of the biochemical networks of reactions that are taking place in the organism is useful but will not, by itself, lead to an understanding of life because the set of biochemical reactions occurring in the organism can be species specific and too complex, especially for multicellular organisms. Also, the standard modelling of biochemical networks neglects the spatial structure and the complex transport and allocation processes in the organism.

By contrast, this paper builds on the premise that the mechanisms that are responsible for the organization of metabolism are not species specific (Kooijman 2000). This hope for generality is supported by (i) the universality of physics and evolution and (ii) the existence of widespread biological empirical patterns among organisms.

The road map of this paper is as follows. In §2, the empirical patterns that characterize metabolism are discussed and presented as stylized facts. They are of the utmost importance because any biological non-species-specific metabolic theory should be compatible with these facts. We believe that such a theory has already been developed, the Dynamic Energy Budget (DEB) theory. This theory aims to capture the quantitative aspects of the organization of metabolism at the organism level with implications for the sub- and supra-organismic levels (Kooijman 2000, 2001; Nisbet et al. 2000). In §3, the DEB theory is formalized for its standard model, which considers an isomorphic organism, with one reserve and one structure. This model is assumed to be appropriate for most heterotrophic unicellular organisms and animals. This theory is formalized such that (i) the assumptions are highlighted and separated from the propositions, (ii) the assumptions are supported by the stylized facts or the universal laws and (iii) the importance and validity of the propositions are discussed. Using the DEB theory, the difference between species can be reduced to differences in the set of parameter values. In §4, the DEB theory for the relationship between parameters among different species is formalized. Section 5 presents the links between empirical patterns, assumptions and propositions, and concludes.

2. Empirical patterns

In this section, we summarize the stylized empirical patterns essential for a theoretical description of metabolic organization in biology (tables 1 and 2). They are related to (i) the metabolic processes common to all organisms, namely feeding, growth, reproduction, maturation and maintenance; (ii) the life stages, i.e. embryo, juvenile and adult; and (iii) the stoichiometry of organisms.

Table 1.

Stylized facts and empirical evidence on feeding, growth and respiration.

| stylized facts | empirical evidence | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| feeding | F1 | starving organisms may reproduce | animals (Kjesbu et al. 1991; Hirche & Kattner 1993; Kirk 1997) |

| F2 | starving organisms may grow | animals (Stromgren & Cary 1984; Russell & Wootton 1992; Roberts et al. 2001; Dou et al. 2002; Gallardo et al. 2004; Zheng et al. 2005) | |

| F3 | starving organisms survive for some time | animals (Stockhoff 1991; Letcher et al. 1996) | |

| bacteria (Kunji et al. 1993) | |||

| growth | G1 | the growth of isomorphic organisms at abundant food is well described by the von Bertalanffy growth curve (Putter 1920; von Bertalanffy 1938) | animals (Frazer et al. 1990; Strum 1991; Chen et al. 1992; Schwartz & Hundertmark 1993; Ferreira & Russ 1994; Ross et al. 1995) |

| G2 | many species do not stop growing after reproduction has started, i.e. they exhibit indeterminate growth (Kozlowski 1996; Heino & Kaitala 1999) | animals (Shine & Iverson 1995; Jorgensen & Fiksen 2006) | |

| holometabolic insects are an exception | |||

| G3 | foetuses increase in weight proportional to cubed time (Huggett & Widdas 1951) | animals (Huggett & Widdas 1951; Zonneveld & Kooijman 1993) | |

| G4 | the logarithm of the von Bertalanffy growth rate of different species corrected for a common body temperature decreases almost linearly with the logarithm of the species maximum size | bacteria (Kooijman 2000, pp. 276–282)yeasts (Kooijman 2000, pp. 276–282)animals (Kooijman 2000, pp. 276–282) | |

| G5 | the logarithm of the von Bertalanffy growth rate for organisms of the same species at different food availabilities decreases linearly with ultimate length | animals (Galluci & Quinn 1979; Kooijman 2000, pp. 96) | |

| G6 | egg size covaries with the nutritional status of the mother | animals (Rossiter 1991a,b; Glazier 1992; Bertram & Strathmann 1998; Heath et al. 1999; McIntyre & Gooding 2000; Yoshinaga et al. 2001; Loman 2002; Nager et al. 2006) | |

| respiration | R1 | freshly laid eggs do not use dioxygen in significant amounts | animals (Romijn & Lokhorst 1951; Pettit 1982; Bucher 1983; Whitehead 1987) |

| R2 | the use of dioxygen increases with decreasing mass in embryos and increases with mass in juveniles and adults | animals (Romijn & Lokhorst 1951; Richman 1958; Pettit 1982; Bucher 1983; Whitehead 1987; Clarke & Johnston 1999; Savage et al. 2004) | |

| R3 | the use of dioxygen scales approximately with body weight raised to power 0.75 (Kleiber 1932) | animals (Richman 1958; Clarke & Johnston 1999; Savage et al. 2004) | |

| R4 | organisms show a transient increase in metabolic rate independent of their body mass after ingesting food—the heat increment of feeding | animals (Janes & Chappell 1995; Chappell et al. 1997; Hawkins et al. 1997; Rosen & Trites 1997; Nespolo et al. 2005) |

Table 2.

Stylized facts and empirical evidence on stoichiometry, energy dissipation and cells.

| stylized facts | empirical evidence | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| stoichiometry | S1 | well-fed organisms have a different body chemical composition than poorly fed organisms | animals (Chen et al. 1981; Hirche & Kattner 1993; Du & Mai 2004; Molnar et al. 2006)yeasts (Hanegraaf et al. 2000) |

| S2 | organisms growing with constant food density converge to a constant chemical composition | animals (Chilliard et al. 2005; Krol et al. 2005; Fink et al. 2006; Ingenbleek 2006; Steenbergen et al. 2006) | |

| energy dissipation | I1 | dissipating heat is a weighted sum of three mass flows: carbon dioxide, dioxygen and nitrogenous waste—indirect calorimetry | animals (Seale et al. 1991) |

| cells | C1 | cells in a tissue are metabolically very similar independent of the size of the organisms (Morowitz 1968) |

These patterns apply to most organisms in many (not all) circumstances. In particular, the behaviour of organisms deviates from the empirical patterns presented here. Some of these deviations are well understood and can be captured by the extensions of the present theory (Kooijman 2000).

The theory that describes the metabolism of organisms should also be compatible with physics and evolution. The physical principles considered here are: (P1) mass and energy are conserved quantities; (P2) any energy conversion process leads to dissipation; (P3) mass and energy flows depend only on intensive properties; and (P4) mass and energy transport are proportional to surface areas because they occur across surfaces.

The evolutionary principles taken into account are: (P5) organisms have increased their control over their metabolism during evolution allowing for some adaptation to environmental changes in short periods and (P6) organisms inherit parents' characteristics in a sloppy way allowing for some adaptation to environmental changes across generations.

3. Theory on metabolic organization

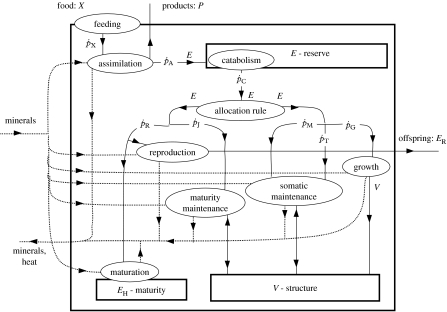

The standard DEB model considers an isomorphic organism, i.e. an organism whose surface area is proportional to volume raised to the power 2/3, with one reserve and one structure. Figure 1 shows the standard DEB model, and tables 3–5 summarize the notation.

Figure 1.

Metabolism in a DEB organism. Square, organism; ovals, processes; rectangles, state variables; arrows are flows of reserve (E), structure (V), minerals, food (X), products (P) or offspring (ER).

Table 3.

List of symbols of variables. (Dimensions: —, no dimension; L, length; T, time; #, moles or C-moles; , energy. Symbols with [ ] are per unit structural volume and dots above are per unit time.)

| dimensions | interpretation | |

|---|---|---|

| state variable | ||

| V | L3 | structural volume |

| E | energy in reserve | |

| EH | energy allocated to maturation | |

| variable | ||

| t | T | time |

| [E] | L−3 | reserve density |

| e | — | scaled reserve density |

| X | # L−3 | substrate density |

| L | L | volumetric length |

| f | — | scaled functional response |

| T−1 | feeding power | |

| T−1 | assimilation power | |

| T−1 | catabolic power | |

| T−1 | volume-related maintenance power | |

| T−1 | maturity maintenance power | |

| T−1 | growth power | |

| T−1 | reproduction power | |

| T−1 | specific growth rate |

Table 4.

List of symbols of parameters. (Dimensions: —, no dimension; L, length; M, mass; T, time; , energy. Symbols with { } are per unit surface area, [ ] are per unit structural volume and dots above are per unit time. Chemical compounds and process specifiers appear as subscripts to other variables.)

| parameter | dimensions | interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| L−2T−1 | surface-specific assimilation power | |

| [Em] | L−3 | maximum reserve density |

| L−3T−1 | volume-specific maintenance power | |

| L−3T−1 | specific maintenance power | |

| L−2T−1 | surface-specific maintenance power | |

| [EG] | L−3 | volume-specific growth costs |

| LT−1 | energy conductance | |

| κ | — | fraction of catabolic power spent on maintenance plus growth |

| κR | — | fraction of reproduction power fixed in eggs |

| g | — | investment ratio |

| T−1 | maintenance rate coefficient | |

| T−1 | maturity rate coefficient | |

| Lm | L | maximum length |

| Lh | L | heating length |

| threshold of energy investment at birth | ||

| threshold of energy investment at puberty | ||

| E0 | energy cost of one egg | |

| μE | M−1 | chemical potential |

Table 5.

List of symbols of compounds and processes.

| interpretation | |

|---|---|

| compound specifier | |

| X | substrate (food) |

| E | reserve |

| V | structure |

| P | products |

| Mi | mineral compound i |

| process specifier | |

| A | assimilation |

| C | catabolism |

| M | maintenance (volume related) |

| T | maintenance (surface related) |

| G | growth |

| R | reproduction or maturation |

The state of the organism is completely described by the volume of the structure V, the amount of energy in the reserve E and the amount of energy invested into maturation EH. The structure and the reserve are generalized compounds, i.e. mixtures of a large number of compounds that compose the biomass of the organism.

Empirical evidence on the variable chemical composition of the organisms (S1) justifies the need for at least two aggregate chemical compounds, i.e. structure V and reserve E to describe the organism.

Empirical evidence on the different life stages that an organism goes through during its life cycle justifies the need for an additional variable, the level of maturity. Although maturity represents neither mass nor energy, it is quantified as the cumulative energy investment into maturation because an organism has to spend energy to increase its complexity (P2).

Life-stage events are linked with maturity, i.e. they occur when EH exceeds certain thresholds. Feeding begins when and allocation to reproduction coupled to the ceasing of maturation begins when . The dynamics of EH is given by

(3.1) where is the power allocated to maturation if and the power allocated to reproduction if .

Other life-history events, such as cell division, metamorphosis or other stage transitions (e.g. to the pupal stage), also occur at threshold values for EH.

The rationale for this assumption is the following: an organism that develops and produces offspring increases its complexity (or maturity) from the embryo to the adult stage. It is reasonable to assume that the amount of energy invested to achieve the degrees of maturity that organisms need to start feeding or allocating to reproduction are intraspecies constants, because the levels of maturity at the onset of these behaviours are the same among the organisms of the same species.

When the multicellular organisms have three life stages: they start as an embryo or foetus that does not feed; become juveniles when feeding starts; and reproduce as adults. The life history of organisms that reproduce by fission is well described by a single life stage, the juvenile.

The structure V and the reserve E do not change in chemical composition and thermodynamic properties. The organism feeds on a resource X and produces products P, also of fixed chemical compositions and constant thermodynamic properties.

The rationale for strong homeostasis is (P5). A stable internal chemical composition means that organisms have a higher control over their own metabolism (P5) because the rate of chemical reactions depends on the chemical composition of the surrounding environment.

Metabolism can be characterized by the following processes:

feeding, i.e. the uptake of food by the organism, where is the energy of the food flow;

assimilation, i.e. the set of reactions that transform food into reserve, where is the reserve energy flow; and

The mobilized reserve is allocated to

(3.2) where is the reserve energy flow allocated to growth and [EG] is the specific cost of growth;

(3.3) somatic maintenance, i.e. the energy necessary to fuel the set of processes that keep the organism alive, where is the reserve energy flow;

maturity maintenance, i.e. the use of reserve to maintain the complexity of the structure, where is the reserve energy flow; and

maturation, i.e. the use of reserve to increase the complexity of the structure called maturity, where is the reserve energy flow; or

(3.4) The fraction of catabolic power allocated to somatic maintenance and growth is a general function , i.e.

(3.5) The remaining fraction is allocated to maturity maintenance, maturation or reproduction

(3.6) The processes of somatic maintenance, maturity maintenance, maturation and dissipation in reproduction consist in an aggregate chemical reaction that transforms reserve plus minerals into minerals. For this reason, the sum of these powers is identified as the dissipation power

(3.7) where κR=0 for the embryo and juvenile stages.

All metabolic processes depend only on V, E and DEB parameters with the exception of feeding and assimilation that also depend on X.

Empirical evidence (R4) shows that there are processes associated with food processing only, which suggests that food goes through a set of chemical reactions that transform it into reserves, assimilation. Organisms have to spend energy on growth, maintenance and reproduction (P2). The fact that organisms are capable of spending energy on these metabolic processes in the absence of food (F1, F2, F3) shows that the energy mobilized is obtained from the reserve and not directly from food. The energy mobilized for maturation is also obtained from the reserve because eggs do not take up food from the environment but they must allocate energy to maturation (assumption 3.2). Maturity maintenance includes maintaining regulating mechanisms and defence systems. The need to allocate energy to maturity maintenance is intimately related with the second law of thermodynamics (P2) because the level of maturity, i.e. the complexity of the organism, would decrease in the absence of energy spent in its maintenance. Also, the existence of an overhead cost of the reproduction process is consistent with the dissipation principle (P2).

This assumption on metabolic organization considers that there is a flow of energy , which is first allocated to maturation and then to reproduction because reproduction starts only when the maturation level reaches (assumption 3.2).

Reserve has no maintenance needs while structure has (positive) maintenance needs.

Structure maintenance costs are

(3.8) where specific maintenance costs are a general function of volume

(3.9) where is the volumetric length and and are the constant volume and the surface-specific maintenance costs, respectively.

The rationale for this assumption is that the organism does not invest in the reserve compounds because they are used for metabolism, i.e. they have a limited lifetime, while the structure compounds are much more permanent implying maintenance costs.

Structure-specific maintenance needs, and , are considered to be constant because the chemical composition and thermodynamic properties of the structure are constant (assumption 3.3). Surface-related maintenance costs are associated with heating (endotherms) and osmosis (fresh water organisms).

Maturity maintenance costs are proportional to the cumulative amount of energy invested into maturation

(3.10) where and is a positive maturity rate coefficient.

In an adult, the maturity maintenance costs are constant because maturity does not increase after the onset of reproduction, while in a juvenile they increase with the level of maturity.

The amount of energy allocated to maturation in a juvenile is

(3.11) and to reproduction in an adult is

(3.12)

All proofs are in the electronic supplementary material, appendix I.

The flow of energy a juvenile allocates to maturation is invested by an adult in reproduction. Thus, an organism kept at a low food density such that the accumulated amount of energy invested into maturation never reaches the threshold will never reproduce.

The amount of energy invested continuously into reproduction is accumulated in a buffer and then it is converted into eggs providing the initial endowment of the reserve to the embryo. This conversion is species specific and typically linked to the seasons in species with a relatively large body size.

Embryos start their development with a negligible amount of structure and a significant amount of reserve.

The stoichiometries of assimilation, growth and dissipation are, respectively,

(3.13)

(3.14)

(3.15) where M1 to Mz are the mineral compounds and yA, yG and yD are the yield coefficients in the assimilation, growth and dissipation processes, respectively, e.g. is the number of C-moles of the reserve produced per each C-mole of food processed in the assimilation process.

Yield coefficients of the assimilation (resp. growth, dissipation) process are constant if the number of chemical elements that participate is more than or equal to z+2 (resp. z+1, z). If the yield coefficient is constant, then the yield coefficient between mass flow *1 and energy flow *2 is also constant.

This proposition means that if the number of chemical elements that participate in the chemical reactions occurring in the organism is higher than the number of mineral compounds, then the yield coefficients are constant.

The stoichiometry of the aggregate chemical transformation that describes the functioning of the organism has 3 d.f. More specifically, any flow produced or consumed in the organism is a weighted average of any three other flows.

The method of indirect calorimetry (I1) is a particular case of proposition 3.10, i.e. the flow of heat is a weighted average of carbon dioxide, dioxygen and nitrogenous waste.

Ingestion at abundant food is proportional to surface area , where is the maximum surface-specific feeding rate. Thus,

(3.16) where the non-dimensional functional response

(3.17) is an increasing function of food with ; is the rate of ingestion at food density X; and is the chemical potential of food, which converts the mass flow to the energy flow .

Feeding is proportional to surface area within the same species because acquisition processes and digestion and other food processing activities depend on mass transport processes that occur through surfaces (P4).

The assimilation power is proportional to surface area,

(3.18) where is the maximum surface-specific assimilation rate.

The organism's reserve E is partitioned in the organism among the categories of chemical compounds, with , with constant energy fractions λi such that

(3.19) The specific somatic maintenance costs and the specific cost of growth paid by each category Ei are proportional to its amount, i.e. and . Also, the catabolic power mobilized from each category Ei is proportional to its amount, i.e. , while the fraction of allocated to growth and maintenance is the same for all the categories, i.e. .

Therefore, the relationship between the overall metabolic power and the metabolic power mobilized from each category is as follows:

(3.20)

The sum of the dynamics of the partitioned reserves is identical to that of the lumped reserve (equation (3.19)). Thus, the reserve can be described with only one state variable (assumption 3.1).

The κ function, i.e. the fraction of the catabolic power allocated to maintenance and growth, is independent of E, i.e.

(3.21)

The κ function is independent of V.1

Note that assumption 3.15 together with proposition 3.14 imposes that κ is constant. This means that reproduction does not compete with growth, which is in agreement with the fact that many organisms do not stop growing after reproduction has started (G2), e.g. daphnia grows a lot during reproduction. The fact that the simplifying assumption that kappa is a constant can match this pattern as well as the pattern that reproduction occurs after growth (as in most mammals and birds) is a good support for this assumption because simple direct competition between growth and reproduction (a variable κ) cannot explain the daphnia case.

Maintenance has priority over growth and maturity maintenance has priority over maturation or reproduction.

For adults and juveniles at any constant food level, , there is a reserve density, , which remains constant along the growth process.

The weak homeostasis assumption says that growing biomass converges to a constant chemical composition as long as the food density remains constant. This is supported by the empirical evidence (S2).

The specific catabolic power, , is given by

(3.22) where is the energy conductance and .

The mobilization of reserves given by equation (3.22) is independent of the environment (food). This is essential because (i) the mobilization of reserves occurs inside the organism at a molecular level, and at that level no information concerning the external environment is available (P3) and (ii) it provides the organism an increased protection against environmental fluctuations and an increased control over its own metabolism (P5). Also, the mobilization of reserves should be uncoupled from the metabolic functions of feeding and assimilation. If the metabolic functions were dependent on each other, then it would be much more difficult to change a particular node at random in the metabolic network (P6) while avoiding complex consequences for the whole organism. The result would be that evolutionary progress would stop, while the environment would continue to change.

The specific catabolic flux is constant for a fully grown organism at constant food level (dV/dt=0 and [E]=[E]*) implying a higher degree of control over its metabolism (P5).

Parameter is an energy conductance because it is the proportionality constant between the flux of reserves per unit structural volume of a fully grown organism and the reserve density gradient

| (3.23) |

Organisms of the same species have a maximum reserve density

(3.24) Organisms achieve maximum reserve density [E]*≡[Em] at abundant food, i.e. .

Organisms of the same species have a maximum (structural) length:

(3.25) Organisms grow to Lm when specific surface maintenance costs are null, i.e. .

Somatic maintenance competes directly with and has priority over growth (see proposition 3.16) implying that somatic maintenance increases proportionally to size (see assumption 3.6), which imposes a maximum size on the organism. In the literature, the existence of a maximum size (including reserve and structure) is generally accepted (G4, G5) implying that the structure also has a maximum size Vm, and that the maximum amount of energy in the reserve Em is limited. Therefore, the maximum reserve density is also limited.

The reserve density under weak homeostasis is given by

(3.26)

The reserve density that growing organisms achieve for any constant food level (assumption 3.15) is proportional to the scaled functional response, i.e. the higher the constant food level the higher the reserve density at equilibrium.

The initial amount of reserve is such that the embryo reserve density at birth equals that of the mother at egg formation.

This assumption is supported by the empirical evidence (G6). The reasoning is the following: if the egg is big, then it has a higher amount of reserve. This will fuel a higher catabolic flux (equation (3.22)) implying that the maturity level is reached sooner when the amount of reserve is higher.

The DEB of an organism and the change in structural length are

(3.27)

(3.28) where is the scaled reserve density and is the volumetric length.

(3.29) is the investment ratio, i.e. the ratio of the costs of growth to the maximum amount of energy allocated to growth and maintenance and is the heating length.

If an organism has no surface maintenance costs, i.e. and Lh=0, then its ultimate length is (see equation (3.28)). For endotherms, the surface maintenance costs are associated mainly with heating, where Lh is the reduction in length due to the energy allocated to these costs. In this case, the ultimate length is (see equation (3.28))

| (3.30) |

The growth curve of an isomorphic juvenile or adult individual at constant food availability X* or at abundant food (f≈1) is

(3.31) The von Bertalanffy growth rate is given by

(3.32) where is the maintenance rate coefficient, i.e. the ratio between the costs of maintenance and growth of structure.

von Bertalanffy's law (equation (3.31)) is one of the most universal biological patterns (G1). Also, organisms of the same species at different food availabilities exhibit von Bertalanffy growth rates that are inversely proportional to ultimate length in accordance with the behaviour predicted by equation (3.32) (G5).

This proposition provides a strong support for assumption 3.15 because (i) the growth rate is constant only if g is constant and (ii) g is constant if κ is independent of V (equation (3.29)).

If the reserves of the mother, continuously supplied to the embryo via the placenta, are considered very large, i.e. e=∞, then foetal growth is given by

(3.33)

According to equation (3.33), the structural volume of the foetus is proportional to cubed time

| (3.34) |

Equation (3.34) is validated by the empirical data that suggest that foetal weight is proportional to cubed time (G3) because the structural volume of the foetus is proportional to weight when the reserve density is constant (see electronic supplementary material, appendix II).

The metabolic rate measured by the dioxygen consumption of fasting animals is proportional to wα with α∈[0.66,1]. If animals have the same reserve density e, then the proportionality constant is the same.

Empirical evidence on Kleiber's law is amply available in the literature (R3).

4. Theory on parameter values

In the DEB theory, the set of parameter values is individual specific. Individuals differ in parameter values and selection leads to evolution characterized by a change in the (mean) value of these parameters (P6). The differences between species are just an evolutionary amplification of the differences between individuals, i.e. they are reduced to differences in the mean value of DEB parameters. In this section, the theory for the covariation of (mean) parameter values among the species is presented.

Constant parameters are identical to related species and independent of the ultimate size of the organism. These parameters include , , , , κ, κR and .

Constant parameters characterize molecular-based processes and do not vary between related species because cells are very similar, independent of the size of the organism (C1). Cells of about equal size have similar growth, maintenance and maturation costs, i.e. , , , and κR are equal for related species. The partitioning of energy mobilized from the reserves is done at the level of the somatic and reproductive cells, and therefore κ is also a molecular-based process. Kooijman & Troost (2007) presented a possible molecular mechanism that makes clear that is a molecular-based parameter. A simpler but less precise argument to justify this is the following. Two fully grown organisms with the same V and the same [E], which belong to different but related species with different maximum lengths, have similar metabolic needs. Therefore, they must have a similar rate of mobilization of reserves, i.e. the same (see equation (3.22)).

Design parameters depend on the maximum length of the species, Lm. These parameters include and , which are proportional to .

Cells of about equal size have similar specific maturation thresholds, i.e. and . Thus, life-stage parameters and are proportional to .

The maximum surface-specific assimilation rate is proportional to Lm.

Parameters that are functions of primary parameters depend on Lm in predictable ways. Examples are:

Lh is independent of Lm, [Em] is proportional to Lm and g is proportional to 1/Lm.

where all parameters with the exception of are for a reference species.

(4.1) Kleiber's law. The metabolic rate measured by the dioxygen consumption of fasting fully grown adult animals that belong to the species with different maximum body sizes is proportional to wα with α∈[0.5,1].

The interspecies comparison of von Bertalanffy growth rate corrected for a common body temperature is supported by empirical data (G4) (for a comparison between empirical data and DEB model predictions see (Kooijman 2000, fig. 8.3).

Dodds et al.'s (2001) re-analyses of datasets supported the fact that the power in Kleiber's law is in the interval [0.5,1] instead of having a unique value of 3/4. These authors tested whether the power is 3/4 or 2/3 finding little evidence for rejecting the power 2/3. Also, Vidal & Whitledge (1982) found powers of 0.72 and 0.85 for crustaceans and Phillipson (1981) found values of 0.66 for unicellular organisms and 0.88 for ectotherms.

5. Conclusions

The DEB theory considers that biomass is partitioned into structure and reserve, which is supported by the empirical evidence that organisms can have a variable stoichiometry (S1). The reserve does not require maintenance because it is continuously used and replenished, while the structure requires maintenance because it is continuously degraded and reconstructed. This is supported by the fact that freshly laid eggs (composed only of reserve) do not use dioxygen in significant amounts and that the use of dioxygen increases with decreasing mass in the embryo as the reserves are transformed into structure and with increasing structure in the juvenile and adult (R1, R2).

Feeding is considered to be proportional to surface area within a species because transport occurs across surfaces (P4). In the organism, (i) food is transformed into the reserve and (ii) the reserve is mobilized to fuel growth, maturation, maintenance and reproduction. This internal organization is suggested by the empirical evidence on the heat increment of feeding (R4) and by the fact that starving organisms survive, grow and reproduce (F1–F3). Additionally, to the processes of growth, maturation, maintenance and reproduction, organisms also allocate energy to maturity maintenance, which is imposed by the need to spend energy to keep the organism far away from equilibrium (P2). The assumption on metabolic organization considers that the flow of energy allocated to reproduction, in an adult, was allocated to maturation in a juvenile instead of being allocated to growth because many organisms do not stop growing after reproduction has started (G2).

The amount of energy invested into maturation is the third state variable. It controls life-history events such as the initiation of feeding and reproduction coupled to the ceasing of maturation.

Metabolic organization is further restricted by the κ rule and the weak homeostasis assumption. The κ rule imposes that (i) the allocations of energy to reproduction and growth do not compete with each other, which is suggested by the laws of mass and energy transfer (P3) and (ii) the energy allocation to growth competes with the energy allocation to somatic maintenance imposing a maximum size within a species (G4, G5). The weak homeostasis assumption imposes that organisms tend to a constant chemical composition in an environment with constant food availability; this is supported by the empirical evidence on a constant stoichiometry under certain conditions (S2) and motivated by evolutionary theory (P5).

The propositions obtained explain the following empirical findings: (i) the method of indirect calorimetry (I1), (ii) von Bertalanffy growth curves (G1), (iii) the variation of von Bertalanffy growth rates within (G5) and across species (G4), (iv) Kleiber's law on metabolic rate (R3) and (v) the pattern of foetal growth (G3).

In physics, it is easy to enforce simplicity in experiments bringing observations closer to theory. In biology, this is more difficult because simple organisms are still very complex and need to live in environments that are not homogeneous. Therefore, organisms deviate from the DEB theory more substantially than the real objects do from physics. In the context of DEB theory, deviations are treated as case-specific modifications that provide important insights into the evolutionary adaptations and the physical–chemical details of that particular species. The DEB theory strategy to deal with exceptions is the following. First, the DEB theory on metabolic organization is used to develop a quantitative expectation for the eco-physiological behaviour of a generalized species. Then, the parameters are estimated for a specific case and their values are compared with the expectations based on the DEB theory on parameter values. Differences highlight the evolutionary adaptations of this particular species. Deviations between the behaviour of this species and the DEB behaviour that is predicted using the estimated parameters are due to physical–chemical details that turn out to be important in this particular case. Although these details are ignored in the DEB theory because they do not always apply, it is still useful to detect the deviations and to provide guidance as to what physical–chemical details were missing in that particular case.

In this paper, we have focused on the standard DEB model for isomorphs with one reserve and one structure. They are ideal to explain the concepts and demonstrate the importance of surface area–volume interactions, which is an important organizing principle, in combination with mass and energy conservation. However, from an evolutionary perspective, they represent an advanced state that evolved from the systems with more reserves and, therefore, less homeostatic control. The evolution of metabolism as a dynamic system is discussed by Kooijman & Troost (2007). Extensions to the standard DEB model, which were not discussed in this paper, include (i) shape corrections for the surface area of the organisms that do not behave as isomorphs but deviate from this in predictable ways Kooijman (2000, pp. 26–29); (ii) the dependence of physiological rates on body temperature (Kooijman 2000); (iii) the inclusion of more reserves (for organisms feeding on simple substrates) and more structures (plants; Kooijman 2000, pp. 168); (iv) an ageing model that explains the phenomenological Weibull (Kooijman 2000, pp. 141) and Gompertz laws (Leeuwen et al. 2002); (v) shrinking whenever the catabolic power mobilized from the reserves is not enough to pay maintenance (Tolla et al. 2007); and (vi) implications for cellular levels (Kooijman & Segel 2005), trophic chains and population dynamics (Muller et al. 2001; Kuijper et al. 2003, 2004a,b; Kooi et al. 2004) and ecosystem dynamics (Kooijman & Nisbet 2000; Kooijman et al. 2002; Omta et al. 2006).

The DEB theory and discussions of the underlying concepts have already been presented in the literature (Nisbet et al. 2000; Kooijman 2001; van der Meer 2006a,b). However, in this paper, we prove that (i) the DEB theory is fully supported by empirical biological patterns and the universal laws of physics and evolution and (ii) it is a theory on metabolic organization that is as formal as physics. Also, we (i) propose a set of stylized empirical patterns that are the ultimate test for any metabolic theory and (ii) use these facts to establish a set of assumptions and obtain the propositions. The validity of each assumption and the empirical fact considered can be independently discussed, leading to a wider consensus in the metabolic field.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from PRODEP III (T.S.) and FCT (grant no. POCI/AMB/55701/2004; T.S. and T.D.). The authors thank João Rodrigues, the members of the research group AQUAdeb and the referees for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Endnote

Deviations from this assumption are necessary in special cases like prolonged starvation.

Supplementary Material

The appendices contain (i) the proofs of the propositions presented in sections III and IV of the paper (appendix I); (ii) an auxiliary proposition on the conversion of structural volume to weight (appendix II), and (iii) an approximation for polynomials (appendix III).

References

- Bertram D.F, Strathmann R.R. Effects of maternal and larval nutrition on growth and form of planktotrophic larvae. Ecology. 1998;79:315–327. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher T.L. Parrot eggs, embryos, and nestlings—patterns and energetics of growth and development. Physiol. Zool. 1983;56:465–483. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell M.A, Bachman G.C, Hammond K.A. The heat increment of feeding in house wren chicks: magnitude, duration, and substitution for thermostatic costs. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 1997;167:313–318. doi:10.1007/s003600050079 [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Jackson D.A, Harvey H.H. A comparison of von Bertalanffy and polynomial functions in modeling fish growth data. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1992;49:1228–1235. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Ke C.H, Zhou S.Q, Li F.X. Effects of food availability on feeding and growth of cultivated juvenile Babylonia formosae habei (Altena and Gittenberger 1981) Aquac. Res. 2005;36:94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chilliard Y, Delavaud C, Bonnet M. Leptin expression in ruminants: nutritional and physiological regulations in relation with energy metabolism. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2005;29:3–22. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2005.02.026. doi:10.1016/j.domaniend.2005.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A, Johnston N.M. Scaling of metabolic rate with body mass and temperature in teleost fish. J. Anim. Ecol. 1999;68:893–905. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2656.1999.00337.x [Google Scholar]

- Dodds P.S, Rothman D.H, Weitz J.S. Re-examination of the ‘3/4-law’ of metabolism. J. Theor. Biol. 2001;209:9–27. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2000.2238. doi:10.1006/jtbi.2000.2238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou S, Masuda R, Tanaka M, Tsukamoto K. Feeding resumption, morphological changes and mortality during starvation in Japanese flounder larvae. J. Fish Biol. 2002;60:1363–1380. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2002.tb02432.x [Google Scholar]

- Du S.B, Mai K.S. Effects of starvation on energy reserves in young juveniles of abalone Haliotis discus hannai Ino. J. Shellfish Res. 2004;23:1037–1039. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira B.P, Russ G.R. Age validation and estimation of growth-rate of the coral trout, Plectropomus leopardus, (Lacepede 1802) from Lizard Island, Northern Great Barrier Reef. Fish. Bull. 1994;92:46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fink P, Peters L, Von Elert E. Stoichiometric mismatch between littoral invertebrates and their periphyton food. Arch. Hydrobiol. 2006;165:145–165. doi:10.1127/0003-9136/2006/0165-0145 [Google Scholar]

- Frazer N.B, Gibbons J.W, Greener J.L. Exploring Fabens' growth interval model with data on a long-lived vertebrate, Trachemys scripta (Reptilia: Testudinata) Copeia. 1990;1:112–118. doi:10.2307/1445827 [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo C.S, Manque C, Filun M. Comparative resistance to starvation among early juveniles of some marine muricoidean snails. Nautilus. 2004;118:121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Galluci V.F, Quinn T.J. Reparameterizing, fitting, and testing a simple growth-model. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1979;108:14–25. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1979)108<14:RFATAS>2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Glazier D.S. Effects of food, genotype, and maternal size and age on offspring investment in Daphnia magna. Ecology. 1992;73:910–926. doi:10.2307/1940168 [Google Scholar]

- Hanegraaf P.P.F, Stouthamer A.H, Kooijman S.A.L.M. A mathematical model for yeast respiro-fermentative physiology. Yeast. 2000;16:423–437. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(20000330)16:5<423::AID-YEA541>3.0.CO;2-I. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(20000330)16:5<423::AID-YEA541>3.0.CO;2-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins P.A.J, Butler P.J, Woakes A.J, Gabrielsen G.W. Heat increment of feeding in Brunnich's guillemot Uria lomvia. J. Exp. Biol. 1997;200:1757–1763. doi: 10.1242/jeb.200.12.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath D.D, Fox C.W, Heath J.W. Maternal effects on offspring size: variation through early development of chinook salmon. Evolution. 1999;53:1605–1611. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1999.tb05424.x. doi:10.2307/2640906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heino M, Kaitala V. Evolution of resource allocation between growth and reproduction in animals with indeterminate growth. J. Evol. Biol. 1999;12:423–429. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.1999.00044.x [Google Scholar]

- Hirche H.J, Kattner G. Egg production and lipid content of Calanus glacialis in spring: indication of a food-dependent and food-independent reproductive mode. Mar. Biol. 1993;117:615–622. doi:10.1007/BF00349773 [Google Scholar]

- Huggett A.S, Widdas W.F. The relationship between mammalian foetal weight and conception age. J. Physiol. 1951;114:306–317. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1951.sp004622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingenbleek Y. The nutritional relationship linking sulfur to nitrogen in living organisms. J. Nutr. 2006;136:1641–1651. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.6.1641S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes D.N, Chappell M.A. The effect of ration size and body-size on specific dynamic action in adelie penguin chicks, Pygoscelis adeliae. Physiol. Zool. 1995;68:1029–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen C, Fiksen O. State-dependent energy allocation in cod (Gadus morhua) Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2006;63:186–199. doi:10.1139/f05-209 [Google Scholar]

- Kirk K.L. Life-history responses to variable environments: starvation and reproduction in planktonic rotifers. Ecology. 1997;78:434–441. [Google Scholar]

- Kjesbu O.S, Klungsoyr J, Kryvi H, Witthames P.R, Walker M.G. Fecundity, atresia, and egg size of captive atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) in relation to proximate body-composition. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1991;48:2333–2343. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiber M. Body size and metabolism. Hilgardia. 1932;6:315–353. [Google Scholar]

- Kooi B.W, Kuijper L.D.J, Kooijman S.A.L.M. Consequences of symbiosis for food web dynamics. J. Math. Biol. 2004;3:227–271. doi: 10.1007/s00285-003-0256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooijman S.A.L.M. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2000. Dynamic energy and mass budgets in biological systems. [Google Scholar]

- Kooijman S.A.L.M. Quantitative aspects of metabolic organization: a discussion of concepts. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2001;356:331–349. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0771. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooijman S.A.L.M, Nisbet R.M. How light and nutrients affect life in a closed bottle. In: Jørgensen S.E, editor. Thermodynamics and ecological modelling. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2000. pp. 19–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kooijman S.A.L.M, Segel L.A. How growth affects the fate of cellular metabolites. Bull. Math. Biol. 2005;67:57–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bulm.2004.06.003. doi:10.1016/j.bulm.2004.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooijman S.A.L.M, Troost T.A. Quantitative steps in the evolution of metabolic organization as specified by the dynamic energy budget theory. Biol. Rev. 2007;82:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2006.00006.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2006.00006.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooijman S.A.L.M, Dijkstra H.A, Kooi B.W. Light-induced mass turnover in a mono-species community of mixotrophs. J. Theor. Biol. 2002;214:233–254. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2458. doi:10.1006/jtbi.2001.2458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski J. Optimal allocation of resources explains interspecific life-history patterns in animals with indeterminate growth. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1996;263:559–566. doi:10.1098/rspb.1996.0084 [Google Scholar]

- Kuijper L.D.J, Kooi B.W, Zonneveld C, Kooijman S.A.L.M. Omnivory and food web dynamics. Ecol. Model. 2003;163:19–32. doi:10.1016/S0304-3800(02)00351-4 [Google Scholar]

- Kuijper L.D.J, Kooi B.W, Anderson T.R, Kooijman S.A.L.M. Stoichiometry and food chain dynamics. Theor. Popul. Biol. 2004a;66:323–339. doi: 10.1016/j.tpb.2004.06.011. doi:10.1016/j.tpb.2004.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijper L.D.J, Anderson T.R, Kooijman S.A.L.M. C and N gross efficiencies of copepod egg production studies using a dynamic energy budget model. J. Plankton Res. 2004b;26:213–226. doi:10.1093/plankt/fbh020 [Google Scholar]

- Kunji E.R.S, Ubbink T, Matin A, Poolman B, Konings W.N. Physiological-responses of lactococcus-lactis ML3 to alternating conditions of growth and starvation. Arch. Microbiol. 1993;159:372–379. doi:10.1007/BF00290920 [Google Scholar]

- Krol E, Redman P, Thomson P.J, Williams R, Mayer C, Mercer J.G, Speakman J.R. Effect of photoperiod on body mass, food intake and body composition in the field vole, Microtus agrestis. J. Exp. Biol. 2005;208:571–584. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01429. doi:10.1242/jeb.01429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeuwen I.M.M, Kelpin F.D.L, Kooijman S.A.L.M. A mathematical model that accounts for the effects of caloric restriction on body weight and longevity. Biogerontology. 2002;3:373–381. doi: 10.1023/a:1021336321551. doi:10.1023/A:1021336321551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letcher B.H, Rice J.A, Crowder L.B, Binkowski F.P. Size-dependent effects of continuous and intermittent feeding on starvation time and mass loss in starving yellow perch larvae and juveniles. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1996;125:14–26. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1996)125<0014:SDEOCA>2.3.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Loman J. Microevolution and maternal effects on tadpole Rana temporaria growth and development rate. J. Zool. 2002;257:93–99. doi:10.1017/S0952836902000687 [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre G.S, Gooding R.H. Egg size, contents, and quality: maternal-age and-size effects on house fly eggs. Can. J. Zool./Rev. Can. Zool. 2000;78:1544–1551. doi:10.1139/cjz-78-9-1544 [Google Scholar]

- Molnar T, Szabo A, Szabo G, Szabo C, Hancz C. Effect of different dietary fat content and fat type on the growth and body composition of intensively reared pikeperch Sander lucioperca (L.) Aquac. Nutr. 2006;12:173–182. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2095.2006.00398.x [Google Scholar]

- Morowitz H.J. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1968. Energy flow in biology. [Google Scholar]

- Muller E.B, Nisbet R.M, Kooijman S.A.L.M, Elser J.J, McCauley E. Stoichiometric food quality and herbivore dynamics. Ecol. Lett. 2001;4:519–529. doi:10.1046/j.1461-0248.2001.00240.x [Google Scholar]

- Nager R.G, Monaghan P, Houston D.C, Arnold K.E, Blount J.D, Berboven N. Maternal effects through the avian egg. Acta Zool. Sin. 2006;52(Suppl.):658–661. [Google Scholar]

- Nespolo R.F, Castaneda L.E, Roff D.A. The effect of fasting on activity and resting metabolism in the sand cricket, Gryllus firmus: a multivariate approach. J. Insect Physiol. 2005;51:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2004.11.005. doi:10.1016/j.jinsphys.2004.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet R, Muller E, Lika K, Kooijman S.A.L.M. From molecules to ecosystems through dynamic energy budget models. J. Anim. Ecol. 2000;69:913–926. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2656.2000.00448.x [Google Scholar]

- Omta A.W, Bruggeman J, Kooijman S.A.L.M, Dijkstra H.A. The biological carbon pump revisited: feedback mechanisms between climate and the Redfield ratio. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006;33:L14613. doi:10.1029/2006GL026213 [Google Scholar]

- Pettit T.N. Embryonic oxygen-consumption and growth of Laysan and black-footed albatross. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1982;242:121–128. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1982.242.1.R121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson J. Bioenergetic options and phylogeny. In: Townsend C.R, Calow P, editors. Physiological ecology: an evolutionary approach to resource use. Blackwell Scientific Publications; Oxford, UK: 1981. pp. 20–50. [Google Scholar]

- Putter A. Studies on the physiological similarity. VI. Similarities in growth. Pflugers Archiv für die Gesamte Physiologie des Menschen und der Tiere. 1920;180:280. [Google Scholar]

- Richman S. The transformation of energy by Daphnia pulex. Ecol. Monogr. 1958;28:273. doi:10.2307/1942243 [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R.D, Lapworth C, Barker R.J. Effect of starvation on the growth and survival of post-larval abalone (Haliotis iris) Aquaculture. 2001;200:323–338. doi:10.1016/S0044-8486(01)00531-2 [Google Scholar]

- Romijn C, Lokhorst W. Foetal respiration in the hen—the respiratory metabolism of the embryo. Physiol. Comp. Oecol. 1951;2:187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen D.A.S, Trites A.W. Heat increment of feeding in Steller sea lions, Eumetopias jubatus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 1997;118:877–881. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9629(97)00039-x. doi:10.1016/S0300-9629(97)00039-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J.L, Stevens T.M, Vaughan D.S. Age, growth, mortality, and reproductive-biology of red drums in North Carolina waters. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1995;124:37–54. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1995)124<0037:AGMARB>2.3.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter M.C. Maternal effects generate variation in life history: consequences of egg weight plasticity in the gypsy moth. Funct. Ecol. 1991a;5:386–393. doi:10.2307/2389810 [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter M.C. Environmentally-based maternal effects: a hidden force in insect population dynamics? Oecologia. 1991b;87:288–294. doi: 10.1007/BF00325268. doi:10.1007/BF00325268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell N.R, Wootton R.J. Appetite and growth compensation in the European minnow, Phoxinus phoxinus (Cyprinidae), following short periods of food restriction. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 1992;34:277–285. doi:10.1007/BF00004774 [Google Scholar]

- Savage V.M, Gillooly J.F, Woodruff W.H, West G.B, Allen A.P, Enquist B.J, Brown J.H. The predominance of quarter-power scaling in biology. Funct. Ecol. 2004;18:257–282. doi:10.1111/j.0269-8463.2004.00856.x [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz C.C, Hundertmark K.J. Reproductive characteristics of Alaskan moose. J. Wildl. Manage. 1993;57:454–468. doi:10.2307/3809270 [Google Scholar]

- Seale J.L, Rumpler W.V, Moe P.W. Description of a direct-indirect room-sized calorimeter. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 1991;260:E306–E320. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.260.2.E306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shine R, Iverson J.B. Patterns of survival, growth and maturation in turtles. Oikos. 1995;72:343–348. doi:10.2307/3546119 [Google Scholar]

- Steenbergen R, Nanowski T.S, Nelson R, Young S.G, Vance J.E. Phospholipid homeostasis in phosphatidylserine synthase-2-deficient mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2006;1761:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockhoff B.A. Starvation resistance of gipsy moth, Lymantria dispar (l.) (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae): tradeoffs among growth, body size and survival. Oecologia. 1991;88:422–429. doi: 10.1007/BF00317588. doi:10.1007/BF00317588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromgren T, Cary C. Growth in length of Mytilus edulis-l fed on different algal diets. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1984;76:23–34. doi:10.1016/0022-0981(84)90014-5 [Google Scholar]

- Strum S.C. Weight and age in wild olive baboons. Am. J. Primatol. 1991;25:219–237. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350250403. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350250403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolla C, Kooijman S.A.L.M, Poggiale J.C. A kinetic inhibition mechanism for maintenance. J. Theor. Biol. 2007;244:576–587. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.09.001. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer J. An introduction to dynamic energy budget (DEB) models with special emphasis on parameter estimation. J. Sea Res. 2006a;56:85–102. doi:10.1016/j.seares.2006.03.001 [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer J. Metabolic theories in ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2006b;21:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.11.004. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal J, Whitledge T.E. Rates of metabolism of planktonic crustaceans as related to body weight and temperature of habitat. J. Plankton Res. 1982;4:77–84. doi:10.1093/plankt/4.1.77 [Google Scholar]

- von Bertalanffy L. A quantitative theory of organic growth (inquiries on growth laws.II.) Hum. Biol. 1938;10:181–213. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead P.J. Respiration of Crocodylus johnstoni embryos. In: Webb G.J.W, Manolis S.C, Whitehead P.J, editors. Wildlife management: crocodiles and alligators. Beatty; Sydney, Australia: 1987. pp. 173–497. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaga T, Hagiwara A, Tsukamoto K. Effect of periodical starvation on the survival of offspring in the rotifer Brachionus plicatilis. Fish. Sci. 2001;67:373–374. doi:10.1046/j.1444-2906.2001.00256.x [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H.P, Ke C.H, Zhou S.Q, Li F.X. Effects of starvation on larval growth, survival and metamorphosis of Ivory shell Babylonia formosae habei Altena et al., 1981 (Neogastropoda: Buccinidae) Aquaculture. 2005;243:357–366. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.10.010 [Google Scholar]

- Zonneveld C, Kooijman S.A.L.M. Comparative kinetics of embryo development. Bull. Math. Biol. 1993;55:609–635. doi: 10.1007/BF02460653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The appendices contain (i) the proofs of the propositions presented in sections III and IV of the paper (appendix I); (ii) an auxiliary proposition on the conversion of structural volume to weight (appendix II), and (iii) an approximation for polynomials (appendix III).