Abstract

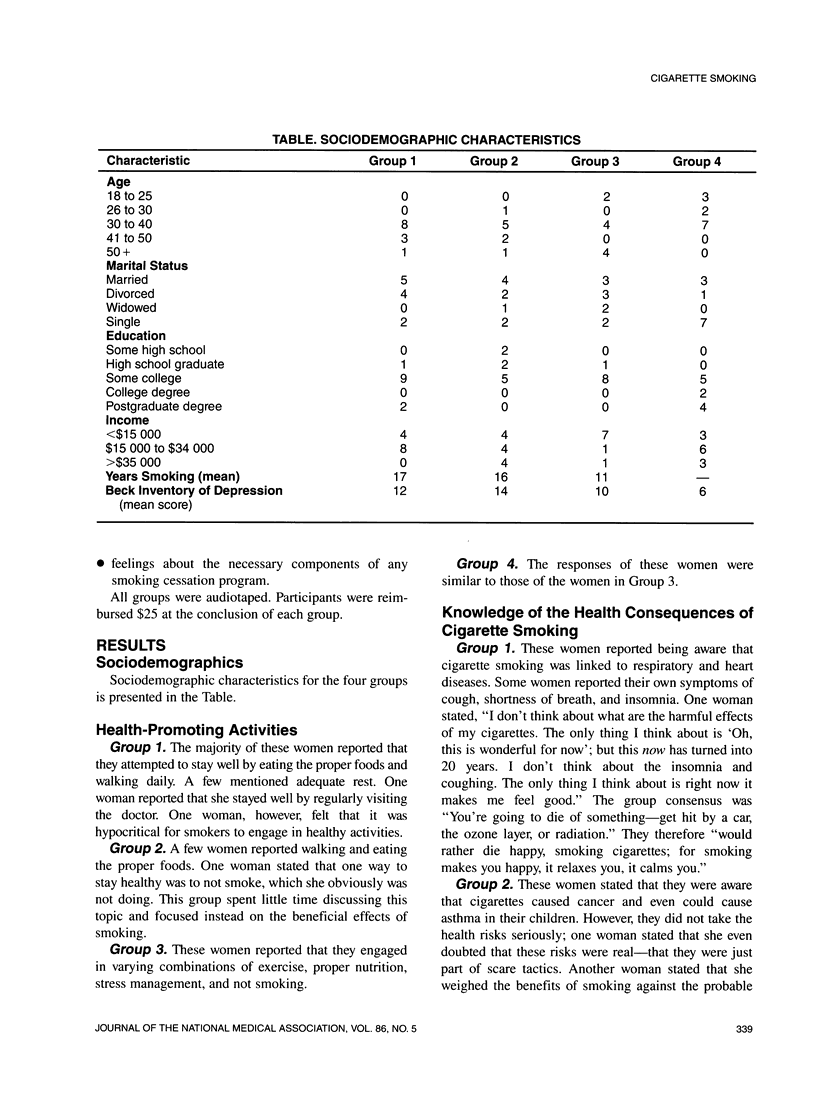

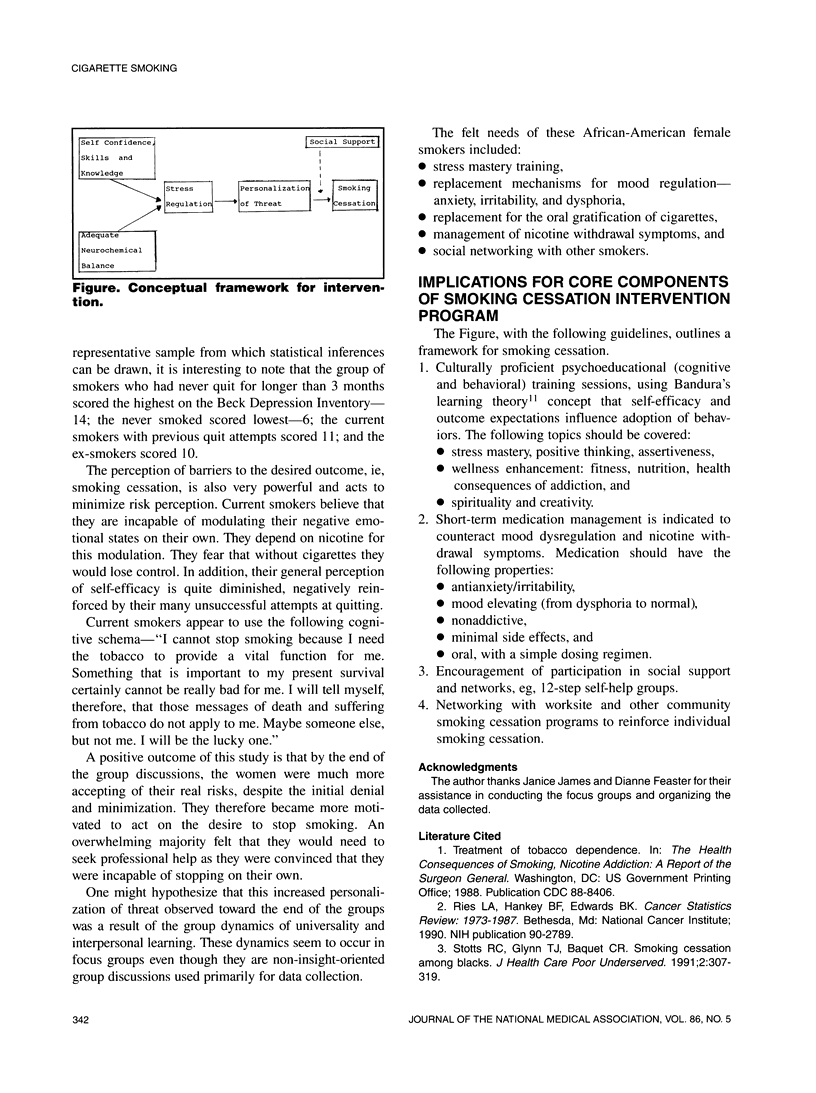

It has been projected that beyond 1995, African-American women will have the highest prevalence of tobacco smoking. This study, therefore, was undertaken to explore the beliefs, attitudes, and practices among African Americans regarding tobacco smoking so as to design more culturally appropriate smoking cessation interventions. Focus group discussions were conducted with 42 African-American women (31 ever smokers and 11 never smoked) exploring in-depth: 1) knowledge of the health consequences of smoking, 2) attitudes about the acceptability of smoking and personal reasons for smoking, 3) smoking practices, and 4) opinions about the necessary components of smoking cessation programs. Compared with nonsmokers, current smokers have not yet personalized the distant threat of smoking due to the very powerful immediate benefit obtained from the nicotine present in tobacco--the decrease in anxiety, tension, and depression, ie, "stress reduction." There is also a perception of powerful barriers to smoking cessation, ie, no internal mechanisms for stress modulation. Smoking cessation intervention programs must have culturally proficient psychoeducational components to address the cognitive and behavioral dysfunction associated with smoking. For those smokers with evidence of difficulty modulating dysphoria or tension, they also must address the possible underlying biochemical dysregulation.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Breslau N., Kilbey M. M., Andreski P. Nicotine withdrawal symptoms and psychiatric disorders: findings from an epidemiologic study of young adults. Am J Psychiatry. 1992 Apr;149(4):464–469. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.4.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch-Lyon E., Trost J. F. Conducting focus group sessions. Stud Fam Plann. 1981 Dec;12(12 Pt 1):443–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman A. H., Helzer J. E., Covey L. S., Cottler L. B., Stetner F., Tipp J. E., Johnson J. Smoking, smoking cessation, and major depression. JAMA. 1990 Sep 26;264(12):1546–1549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat G. C., Morabia A., Wynder E. L. Comparison of smoking habits of blacks and whites in a case-control study. Am J Public Health. 1991 Nov;81(11):1483–1486. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.11.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K., Kabat G., Wynder E. Progress in decreasing cigarette smoking. Important Adv Oncol. 1991:205–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royce J. M., Hymowitz N., Corbett K., Hartwell T. D., Orlandi M. A. Smoking cessation factors among African Americans and whites. COMMIT Research Group. Am J Public Health. 1993 Feb;83(2):220–226. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.2.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotts R. C., Glynn T. J., Baquet C. R. Smoking cessation among blacks. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1991 Fall;2(2):307–319. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]