Abstract

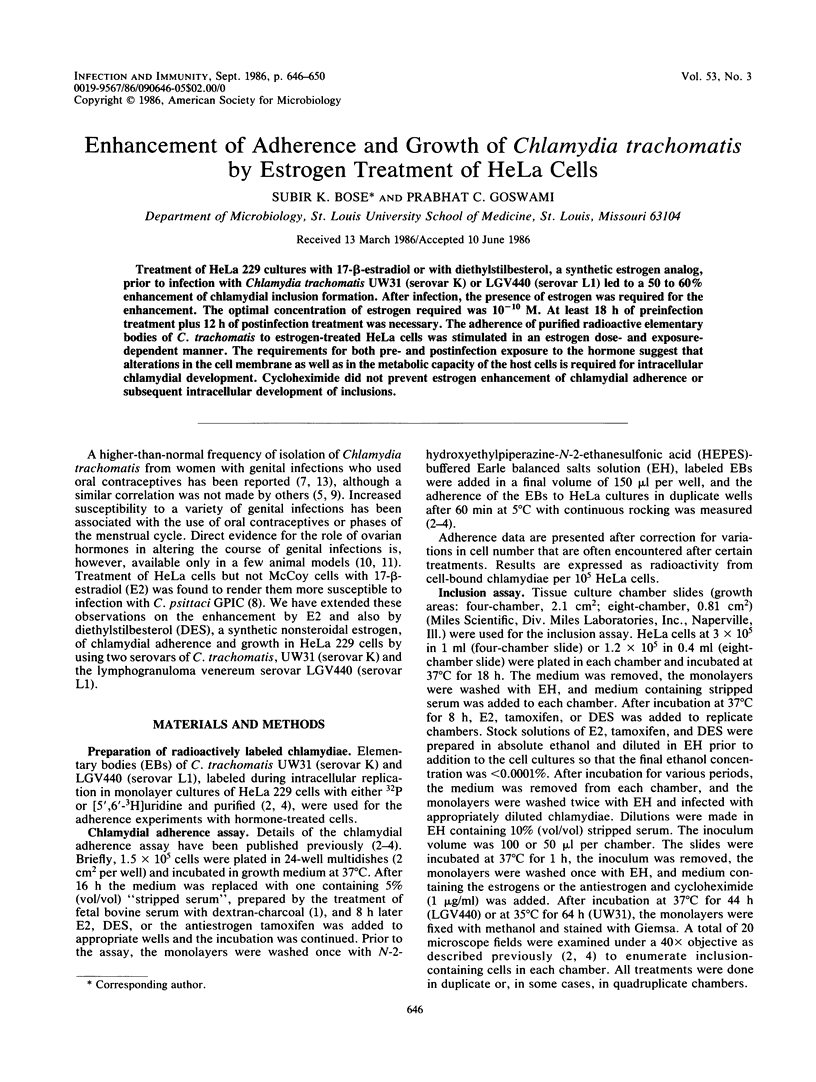

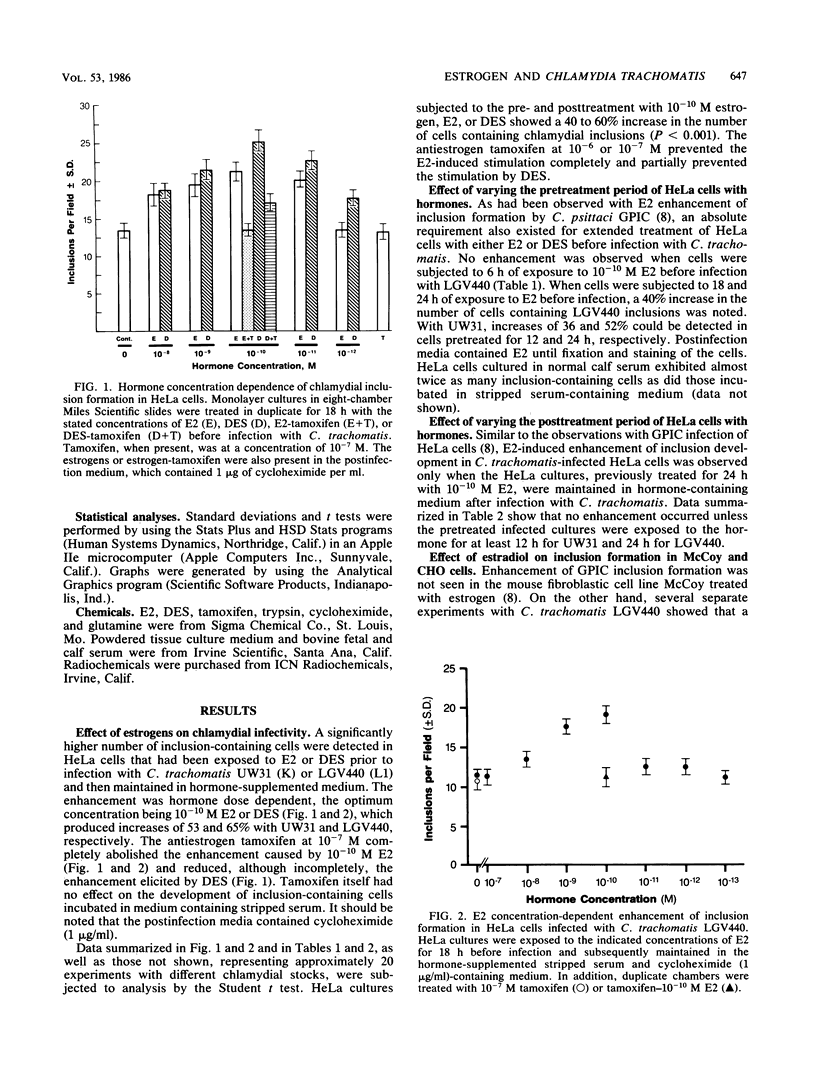

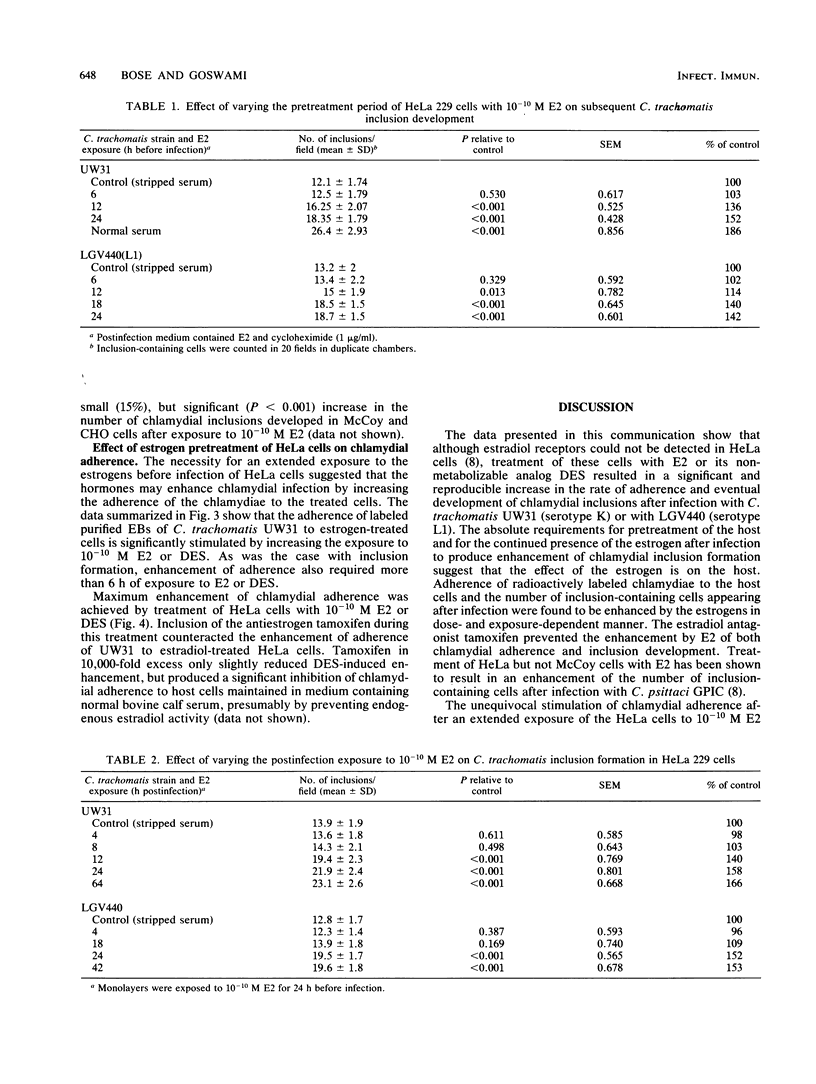

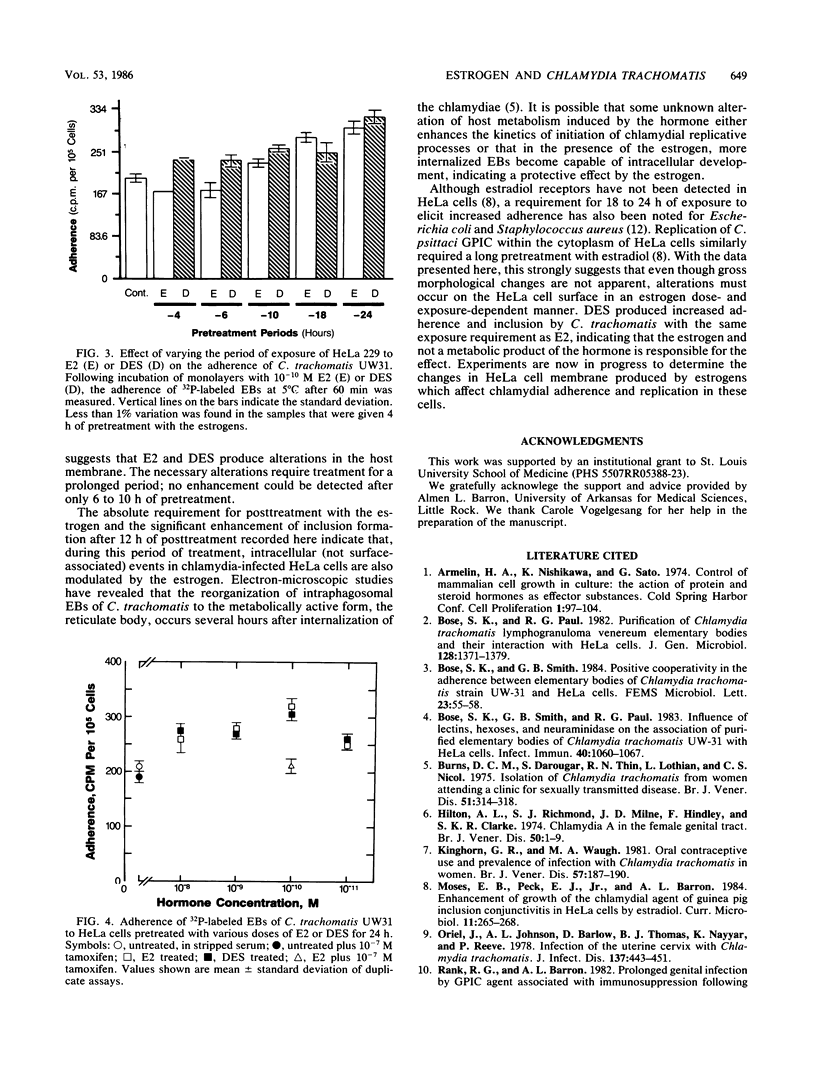

Treatment of HeLa 229 cultures with 17-beta-estradiol or with diethylstilbestrol, a synthetic estrogen analog, prior to infection with Chlamydia trachomatis UW31 (serovar K) or LGV440 (serovar L1) led to a 50 to 60% enhancement of chlamydial inclusion formation. After infection, the presence of estrogen was required for the enhancement. The optimal concentration of estrogen required was 10(-10) M. At least 18 h of preinfection treatment plus 12 h of postinfection treatment was necessary. The adherence of purified radioactive elementary bodies of C. trachomatis to estrogen-treated HeLa cells was stimulated in an estrogen dose- and exposure-dependent manner. The requirements for both pre- and postinfection exposure to the hormone suggest that alterations in the cell membrane as well as in the metabolic capacity of the host cells is required for intracellular chlamydial development. Cycloheximide did not prevent estrogen enhancement of chlamydial adherence or subsequent intracellular development of inclusions.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bose S. K., Paul R. G. Purification of Chlamydia trachomatis lymphogranuloma venereum elementary bodies and their interaction with HeLa cells. J Gen Microbiol. 1982 Jun;128(6):1371–1379. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-6-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose S. K., Smith G. B., Paul R. G. Influence of lectins, hexoses, and neuraminidase on the association of purified elementary bodies of Chlamydia trachomatis UW-31 with HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 1983 Jun;40(3):1060–1067. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.3.1060-1067.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns D. C., Darougar S., Thin R. N., Lothian L., Nicol C. S. Isolation of Chlamydia from women attending a clinic for sexually transmitted disease. Br J Vener Dis. 1975 Oct;51(5):314–318. doi: 10.1136/sti.51.5.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton A. L., Richmond S. J., Milne J. D., Hindley F., Clarke S. K. Chlamydia A in the female genital tract. Br J Vener Dis. 1974 Feb;50(1):1–10. doi: 10.1136/sti.50.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinghorn G. R., Waugh M. A. Oral contraceptive use and prevalence of infection with Chlamydia trachomatis in women. Br J Vener Dis. 1981 Jun;57(3):187–190. doi: 10.1136/sti.57.3.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oriel J. D., Johnson A. L., Barlow D., Thomas B. J., Nayyar K., Reeve P. Infection of the uterine cervix with Chlamydia trachomatis. J Infect Dis. 1978 Apr;137(4):443–451. doi: 10.1093/infdis/137.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank R. G., White H. J., Hough A. J., Jr, Pasley J. N., Barron A. L. Effect of estradiol on chlamydial genital infection of female guinea pigs. Infect Immun. 1982 Nov;38(2):699–705. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.2.699-705.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman B., Epps L. R. Effect of estrogens on bacterial adherence to HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 1982 Feb;35(2):633–638. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.2.633-638.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson L., Weström L., Mårdh P. A. Chlamydia trachomatis in women attending a gynaecological outpatient clinic with lower genital tract infection. Br J Vener Dis. 1981 Aug;57(4):259–262. doi: 10.1136/sti.57.4.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]