Abstract

Although developmental exposures of rats to low levels of the organophosphate pesticides (OPs), chlorpyrifos (CPF) or diazinon (DZN), both cause persistent neurobehavioral effects, there are important differences in their neurotoxicity. The current study extended investigation to parathion (PTN), an OP that has higher systemic toxicity than either CPF or DZN. We gave PTN on postnatal days (PND) 1–4 at doses spanning the threshold for systemic toxicity (0, 0.1 or 0.2 mg/kg/day, s.c.) and performed a battery of emotional and cognitive behavioral tests in adolescence through adulthood. The higher PTN dose increased time spent on the open arms and the number of center crossings in the plus maze, indicating greater risk-taking and overall activity. This group also showed a decrease in tactile startle response without altering prepulse inhibition, indicating a blunted acute sensorimotor reaction without alteration in sensorimotor plasticity. T-maze spontaneous alternation, novelty suppressed feeding, preference for sweetened chocolate milk, and locomotor activity were not significantly affected by neonatal PTN exposure. During radial arm maze acquisition, rats given the lower PTN dose committed fewer errors compared to controls and displayed lower sensitivity to the amnestic effects of the NMDA receptor blocker, dizocilpine. No PTN effects were observed with regard to the sensitivity to blockade of muscarinic and nicotinic cholinergic receptors, or serotonin 5HT2 receptors. This study shows that neonatal PTN exposure evokes long-term changes in behavior, but the effects are less severe, and in some incidences opposite in nature, to those seen earlier for CPF or DZN, findings consistent with our neurochemical studies showing different patterns of effects and less neurotoxic damage with PTN. Our results reinforce the conclusion that low dose exposure to different OPs can have quite different neurotoxic effects, obviously unconnected to their shared property as cholinesterase inhibitors.

Keywords: Parathion, Organophosphates, Cognitive function, Emotional function, Development, Non-cholinergic effects

Introduction

The developmental neurotoxicity of organophosphate (OP) pesticides is of great concern because human exposures appear to be nearly ubiquitous [8]. Although the acute, high dose toxic effects of OPs involve cholinergic hyperstimulation consequent to inhibition of acetylcholinesterase, the persisting adverse effects of low dose exposure on brain development arise from a variety of mechanisms that impact brain development, including impairments of neural cell proliferation, differentiation, axonogenesis and synaptogenesis [20,26–28]. Importantly, the neurodevelopmental effects occur at doses below the threshold for systemic toxicity or even for acetylcholinesterase inhibition, so that the outcomes can differ among the various OPs. In a series of studies, we compared the long-term neurochemical and behavioral effects after exposure of neonatal rats to chlorpyrifos (CPF) or diazinon (DZN) in doses spanning the threshold for barely-detectable cholinesterase inhibition and found some similarities, but also major differences in outcome [2,13,16,17,19,21,23,33]. More recently, we have begun to examine parathion (PTN), a more systemically toxic OP that has been far less studied. Because the maximum tolerated dose of PTN is much lower than that of the other agents, we postulated that there might be less long-term neurotoxic damage from low doses, given the fact that systemic toxicity and developmental neurotoxicity involve separate mechanisms [23,28]. In particular, we found less initial neural damage and a smaller impact on developing acetylcholine and serotonin (5HT) systems.

In the current study, we evaluated the long-term cognitive and emotional effects in adolescent and adult rats exposed to PTN during the early postnatal period, using treatment paradigms and behavioral tests comparable to those in our earlier work with CPF and DZN. Our objectives were to find out whether early postnatal exposure to low doses of PTN can cause persistent behavioral impairments, and to compare the effects of PTN to those of CPF and DZN.

Methods

Animal Subjects

All experiments were carried out in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and in accordance with federal and state guidelines. Timed-pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, Raleigh, NC, USA) were housed in plastic breeding cages under a 12-hr light/dark cycle and free access to food and water. On the day of birth, the postnatal day (PND) 0, all pups were randomized and redistributed to the dams with a litter size of 12 (6 males and 6 females) to maintain a standard nutritional status. Same-sexed rats from each litter were weighed in a group and given daily subcutaneous injections of 0, 0.1, or 0.2 mg/kg PTN (Chem Service, West Chester, PA, USA) on PND 1–4, a time period for peak sensitivity to OPs [17,23]. Because of its poor water solubility, PTN was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide to provide consistent absorption [34] and was injected at a volume of 1 ml/kg once daily. Control rats received equivalent injections of the dimethylsulfoxide vehicle. There were 12 dams per treatment group. These doses span the threshold for minimally-detectable cholinesterase inhibition (ca. 10%) and emergence of systemic toxicity as defined by decreased viability [23,28]. Rats were randomized within treatment groups at intervals of several days, and in addition, dams were rotated among litters every 2–3 days to distribute any maternal caretaking differences randomly across litters and treatment groups.

Pups were weaned on PND 21 and transferred to another room with a reversed dark-light cycle (lights off at 8:00 AM) and weighed at least weekly. Weaned pups were originally housed in same-sex and same-exposure groups of 6/cage, but as they grew, they were subdivided into smaller groups in accordance with the federal guidelines. By the time of behavioral testing, the males were housed in pairs whereas the females were housed three to a cage. All behavioral testing was carried out during the dark phase, the active period for rats, but in lighted environments so that the rats could access the visual cues necessary to perform the tasks. To facilitate comparisons across OPs, the test battery was substantially the same as we have previously used to assess the persisting behavioral effects of chlorpyrifos and diazinon [2,13,16,17,19,33]. Detailed methods are given in those papers with brief descriptions given below. The tests were performed during adolescence through adulthood beginning with T-maze spontaneous alternation (PND 35–45), Elevated Plus Maze (PND 50–53), Figure-8 locomotor activity (PND 58–61), Novelty Suppressed Feeding (PND 64–72), Home Cage Feeding (PND 73–78), Prepulse Inhibition (PND 78–81), Chocolate Milk Anhedonia Test (PND 81–94), followed by radial-arm maze (RAM) training (PND 112–182) and drug challenges (PND 181–328). All rats were exposed to these tests in a sequential order, thirty-one of which (16 males and 15 females) served as controls, 36 (18 males and 18 females) were treated with low and 34 (16 males and 18 females) with high dose of PTN.

T-maze spontaneous alternation

A T-maze, constructed of black painted wood, elevated 1 m from the floor was used. Alleys were 10-cm wide with a 65 cm long stem and 40 cm long choice arms. After 10 s in the start area the rat was permitted to roam about the maze, allowing 30 s to enter one of the arms. After a choice the rat was kept in the choice arm for 30 s and then placed back in the start area. Five trials were run during the single session. Percent of alternation between left and right arms and average response latency (time between the moment of raising the barrier in the start area and the moment when rat enters one of the arms) were calculated. The spontaneous alternation test is without explicit reward other than the motivation to explore a new area. Normally rats will alternate choices approximately 85% of the time in such a test.

Elevated Plus Maze

The maze was constructed of black-painted wood with arms 55 cm long and 10.2 cm wide, 50.8 cm above the floor. Two opposed arms had walls that were 15.2 cm high (closed arms), and the other two opposed arms, had railings 2 cm tall (open arms). Rats were placed in the center of the maze facing an open arm and allowed to roam freely for a total of 300 s. The time spent on the closed arms and the number of open and closed arm entries were the dependent measures.

Figure-8 locomotor activity

The maze consisted of a continuous enclosed alley 10×10 cm in the shape of figure-8 and two blind alleys extending from either side. Eight infrared photobeams crossing the maze alleys were used to assess locomotor activity. The number of photobeam breaks was tallied in 5-minute time blocks during a single 1-h session. The linear and quadratic trends across the twelve blocks were calculated to test the hypothesis that PTN exposure affects the rate of habituation. Four of such mazes were assigned for males only, and four for females.

Novelty-Suppressed Feeding

The methods for novelty-suppressed feeding were modified from [5–7]. Rats were food deprived for approximately 24 hours prior to testing. A novel environment was created by placing a plastic rectangular cage that was slightly different from their home cage in the middle of the test room without any bedding or cage top. Each rat was tested in a clean novel cage. Twelve food pellets same as those used in their regular diet (Purina Rodent Chow Diet 5001; Ralston-Purina, St. Louis, MO, USA) and approximately 2.5 cm in length were weighed prior to testing and spread across the floor. Each rat was tested for 10 min in the novel cage, and the experimenter recorded the latency to begin eating, the number of eating bouts, the total time spent eating and the amount of food eaten.

Previous reports of novelty-suppressed feeding have evaluated home cage feeding to determine if the experimental condition alters appetite or motivation to eat [4,7]. Thus, home cage feeding was evaluated in rats one week following the novelty-suppressed feeding. Rats were food deprived for approximately 24 hours and tested with their cage mates in their home cage within the cage bank. Twelve pellets/rat were weighed and placed in the home cage in rows for the 10 min test session, and the amount of food eaten in the home cage was determined.

Chocolate Milk Anhedonia Test

Methods were modified from [2]. One hour after the start of the dark cycle, rats were placed in individual clean cages in the test room. The rats had ad lib food and water prior to testing, but food was not available during the test session. Rats were presented with a choice of two bottles. One bottle contained tap water, and the other contained Hunter Farms Truly Chocolate Milk (High Point, NC, USA). The amount of fluid consumed from each bottle in the 2-hour test was determined. The rats had no prior experience with drinking from bottle spouts as their home cages had an automatic watering system.

Prepulse inhibition (PPI)

Startle reflex and prepulse inhibition were measured using an adaptation of the classic acoustic method outlined by Swerdlow et al., [30–32] to assess sensorimotor gating. The currently used test had an acoustic prepulse and a tactile startle stimulus. The test apparatus was in a sound-attenuating box within which the rat was placed inside a clear Plexiglas tube on top of a force tranducing response platform. The startle reflex amplitude and PPI were measured using San Diego Instruments Startle Reflex System (San Diego, CA, USA). To habituate the rats to the holding tube they were placed in the Plexiglas tube for 5-min one-two days before testing. There was a continuous 65-dB background white noise during the session. After a 5-min acclimation period inside the box testing began. The startle response was measured in three test blocks and was elicited by a 4 pounds per square inch (27.6 kilopascals) air puff to the back of the rat. The first block had six trials of startle alone. Block two had 12 trials of startle alone, and 36 prepulse plus startle trials, with prepulse/startle delay of 100 ms. The intertrial duration was 10–20 s with a null period of 100 ms. Trials were conducted in a random order with respect to startle and prepulse startle. There were three prepulse levels administered randomly in the prepulse startle trials (68, 71, and 77 dB pure tone). In the third block of trials, the rats were given additional trials of the startle response. The auditory and tactile stimuli had 2 ms rise/fall time.

Radial-arm maze (RAM)

During the RAM training and drug testing, rats had ad libitum access to water with daily feeding after testing, to maintain body weight at a lean health weight with a target of approximately 85% of free feeding level. This was determined of the weight growth in rats having free access to food and water, matching in age.

The black-painted wood maze was at an elevation of 30 cm. The central platform had a diameter of 50 cm and 16 arms (10 × 60 cm) projected radially outward. Each arm contained a food cup 2 cm from the distal end. The test areas contained numerous visual cues. Rats were given 2 shaping sessions in which they were placed individually in a large, opaque cylinder on the platform of the maze, given food reinforcement (halves of sugar coated cereal, Froot Loops®, Kellogg’s, Battle Creek, MI, USA), and allowed 10 min to eat. The rats were then trained in the radial-arm maze. The same 12 arms were baited for each rat once at the beginning of each session to assess working memory, while the other four arms were left unbaited to test reference memory in subsequent sessions. The pattern of baited and unbaited arms was consistent throughout testing for each rat but differed among rats. Each trial began by placing the rat in an opaque cylinder on the central platform for 10 s to allow for orientation and thus avoid introducing bias as to which arm would be entered first. The rat was then allowed to freely enter any arm. The session lasted for up to 10 min, or until all 12 baited arms were entered. Arms were baited only once and a repeated entry into a baited arm was counted as a working memory error. Entrance into an unbaited arm was recorded as reference memory error. Latency (seconds per arm entry) was calculated as the total session time in seconds divided by the total number of the arm entries. Choice accuracy was recorded as the number of working and reference errors. The animals were trained for 18 sessions on the maze, twice per week. Males and females were tested in alternating order. The maze was cleaned between animals with a damp paper towel.

Drug challenges in the radial-arm maze

After RAM training, the rats were tested with drug challenges. Each rat received each drug dose in a repeated measures counterbalanced order, with at least 2 days between doses. A muscarinic receptor antagonist, scopolamine HCl (0, 0.4, 0.8, and 1.6 mg/kg), 5-HT2 receptor antagonist, ketanserin maleate (0, 0.04, 0.08, and 0.16 mg/kg), NMDA receptor antagonist, dizocilpine ((+) MK-801 maleate at doses 0, 12.5, 25 and 50 μg/kg,), or nicotinic receptor antagonist, mecamylamine HCl (0, 2, 4, 8 mg/kg), were administered s.c. 20 min before the beginning of the RAM test. Drugs were dissolved in isotonic saline vehicle. Scopolamine, dizocilpine and mecamylamine were injected in a volume of 1 ml/kg, and ketanserin was administered in a volume of 2 ml/kg due to the lower solubility of this compound. To reduce potential carryover effects, at least a 2-week drug-free period was interposed between drug phases, during which the rats were tested with saline injections. The drug effects were investigated in the following order: scopolamine (PND 181-210), ketanserin (PND 253-260), dizocilpine (PND 276-290), and mecamylamine (PND 310-328).

Data analysis

Data are presented as means and standard errors, with effects of PTN established by multivariate analysis of variance (ANOVA), involving factors both between subjects (dose and sex) and within subjects (test session, period within session, drug dose). A value of p<0.05 was considered the threshold for significance. However, for interaction terms at p<0.1, values were separated according to the interactive factors and the data reexamined for lower-order main effects [29]; that is, the p<0.1 criterion for interactions was not defined as “significant,” but rather was used to trigger the lower-order testing. When interactions of treatment with other variables were not significant, only main effects were tabulated. In situations where there was no treatment × sex interaction, values for males and females were combined for presentation but the factor of sex was retained in the statistical calculations. Linear and quadratic trend analyses were used to assess progressive effects across repeated measures such as time blocks and drug doses.

Results

Although the higher PTN dose caused a small degree of initial systemic toxicity, approximately 5% mortality, without growth retardation in the survivors [23]. By the time of testing, neither dose of PTN showed any persistent signs of systemic toxicity such as reduced viability, impaired weight gain, abnormalities of gait or weakened motor activity. Nevertheless, selective significant behavioral abnormalities were found in adolescence and adulthood after neonatal exposure to either PTN dose. The detected behavioral effects did not seem to be due to generalized impairment as evidenced by lasting alterations of some particular tasks but not others.

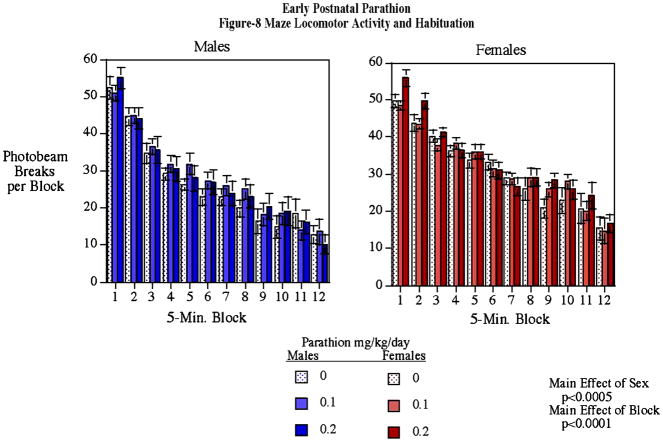

Neonatal PTN exposure did not evoke significant differences in either the percent of spontaneous alternation or the response latency in rats tested in the T-maze. The percent alternation for controls was 80.9±8.4 for controls, 86.6±5.5 for 0.1 mg/kg parathion and 77.8±8.1 for 0.2 mg/kg parathion. There was also no discernible PTN effect on locomotor activity in the Figure-8 apparatus. PTN-exposed animals showed normal habituation of motor activity over the course of the one-hour test, with the same gender differences as seen in controls (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Motor activity in the parathion-treated animals did not significantly differ from controls (mean±sem).

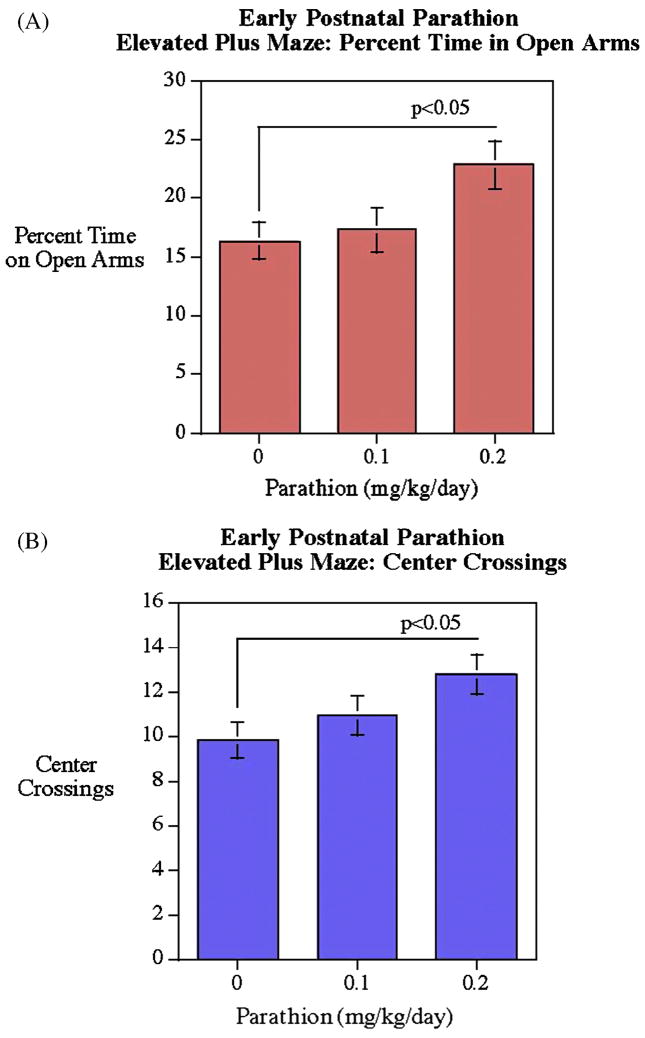

In the Elevated Plus Maze the higher PTN dose (0.2 mg/kg/day) significantly (p<0.05) increased the time spent on the open arms (Fig. 2A) and the number of center crossings (p<0.05) relative to vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 2B), without significant sex differences in the PTN effect.

Figure 2.

Elevated plus maze. The higher dose PTN group had significant increases in the both percent open arm choice and center crossings (mean±sem).

Novelty suppressed feeding and chocolate milk preference was not found to be affected by neonatal PTN exposure. The latency to begin feeding in the novelty suppressed feeding test for controls was 208.5±22.2 seconds; for the 0.1 mg/kg parathion group it was 179.7±22.4 seconds; and for the 0.2 mg/kg parathion group it was 226.4±26.8 seconds. For the chocolate milk test the ration of chocolate milk to water was 1.2±0.1 for controls, 3.8±2.6 for 0.1 mg/kg parathion and 1.4±0.2 for 0.2 mg/kg parathion.

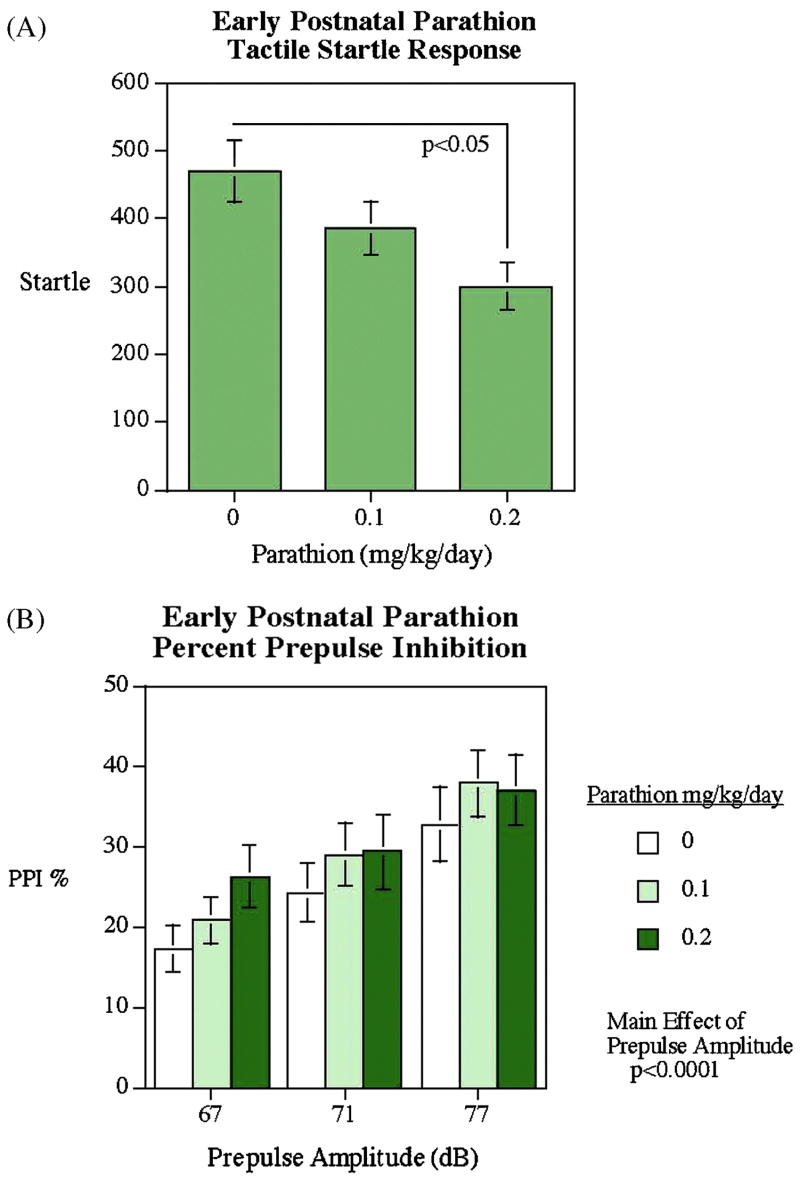

There was a significant (p<0.05) PTN-induced decrease in tactile sensorimotor startle response when no warning prepulse was given (Fig. 3A), without any sex-selectivity of the effect. Prepulse inhibition of the startle response was unaffected by PTN, although in all the groups there was a clear increase in PPI with louder prepulses, demonstrating the validity of the test (Fig. 3B, p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Prepulse inhibition test. The higher PTN group showed a significantly reduced tactile startle response. PPI was not significantly changed by PTN exposure (mean±sem).

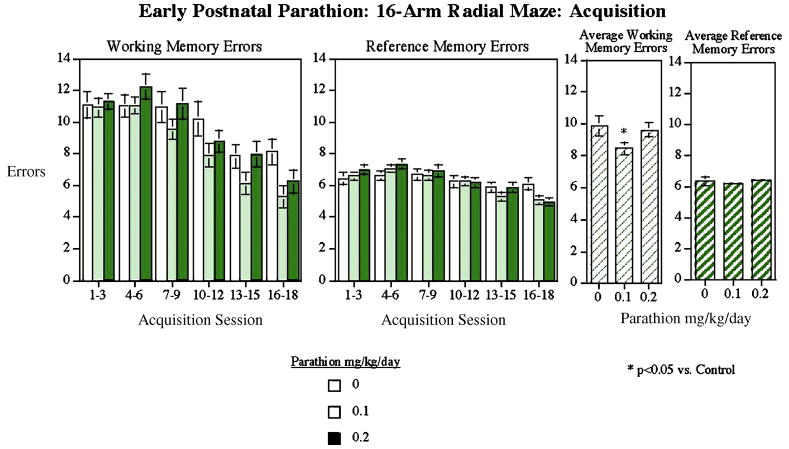

During the RAM acquisition phase, control animals showed the normal sex difference in performance, with males committing fewer errors than females (sex × block interaction, p<0.01, data not shown), in agreement with our earlier studies [16,17]. PTN exposure produced significant alterations in working memory performance without sex-selectivity (no sex × treatment interaction), so values for males and females are shown combined (Fig. 4). The main effect of PTN was restricted to the group receiving 0.1 mg/kg/d (p<0.05), thus comprising a non-monotonic effect of PTN on working memory acquisition. Animals exposed to the lower PTN dose demonstrated a significant improvement in the radial maze learning relative to controls whereas the higher PTN dose group did not significantly differ.

Figure 4.

Radial-arm maze. The low dose PTN group had a significantly reduced average number of working memory errors during training sessions 1–18 (mean±sem).

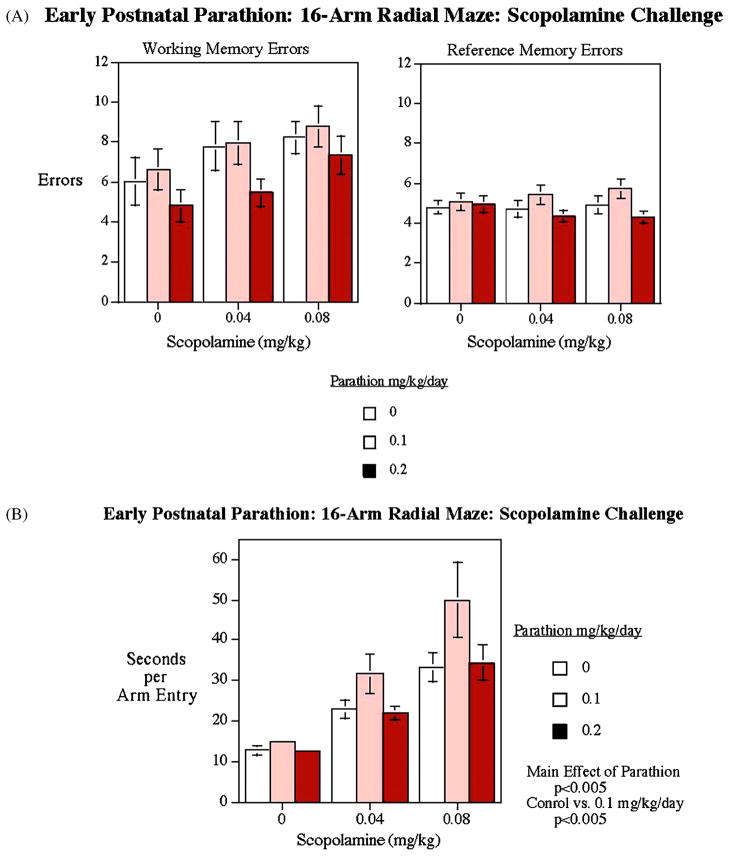

Drug challenges of cholinergic, serotonergic and glutamatergic systems were performed after completion of the RAM training to explore the neural basis underlying these changes. The muscarinic cholinergic antagonist, scopolamine evoked a significant (p<0.001) increase in working memory errors, providing a positive control validating the RAM test [10]. The scopolamine effect was not significantly different in control and PTN treatment groups (Fig. 5A). As expected, reference memory was not affected by scopolamine in any of the groups. However, scopolamine significantly (p<0.0001) increased the choice latency, with a larger effect in the low-dose PTN group (Fig. 5B, p<0.05, low-dose vs. control). There was excessive non-response at the highest scopolamine dose, such that choice accuracy could not be assessed. Latency was analyzed for all doses.

Figure 5.

Radial-arm maze. Scopolamine challenge. There was no significant difference in the working and reference memory errors between PTN-treated and control groups in response to scopolamine challenge. The lower dose PTN group showed significantly higher latency during this phase of testing (mean±sem).

In our earlier work with CPF, we found that over the dose range of 0.5–2 mg/kg ketanserin, a 5HT2 receptor antagonist, caused increasing working memory impairments in the CPF group but not in controls [2]. Using the same ketanserin protocol, in the current study, we did not see any impairment in the PTN group, matching our previous negative finding for DZN [33]. Working memory errors averaged 4.2±0.4 after saline injections to 4.9±0.5 after 2 mg/kg of ketanserin the highest dose tested.

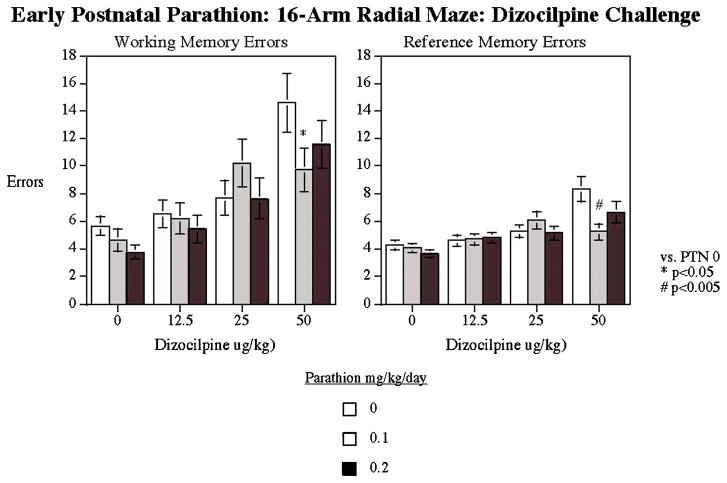

As expected, NMDA receptor blockade with dizocilpine significantly (p<0.0001) increased both working and reference memory errors (Fig. 6). The animals exposed to 0.1 mg/kg/d of PTN and challenged with the highest dizocilpine dose (50 μg/kg, known to cause most reliable amnestic effect) showed significantly less impairment of working (p<0.05) and reference (p<0.005) memory compared to controls.

Figure 6.

Radial-arm maze: Dizocilpine challenge. The low dose PTN group had a significant reduction of the working and reference memory errors compared to controls in response to dizocilpine challenge (mean±sem).

Nicotinic cholinergic receptor blockade with mecamylamine significantly increased (p<0.05) working memory errors over all groups (Saline=3.1±0.5, 2 mg/kg=4.3±0.6, 4 mg/kg=4.1±0.4 and 8 mg/kg=4.1±0.4 errors) and increased (p<0.0001) choice latency, with effects in the control and both PTN groups not being different (Saline=13.8±0.6 and 8 mg/kg mecamylamine=47.9±4.6 seconds per entry).

Discussion

The current study demonstrates the divergent neurobehavioral effects of early neonatal exposure to PTN as compared to CPF and DZN. While it is true that all three OPs have long-lasting neurobehavioral effects, the outcomes are actually quite different for each compound [2,13,16,17,19–21,23,26–28,33]. In general, PTN affected a smaller number of behaviors than did CPF or DZN, showed a smaller magnitude of effect in most tests, and lacked the prominent sex-selectivity seen with the other two agents. Further, some of the outcomes for PTN exposure were even in a different direction from those produced by CPF or DZN. These findings are consistent with the view that the OPs differ substantially in their long-term neurobehavioral effects, reflecting the participation of neurodevelopmental mechanisms other than their shared property of cholinesterase inhibition [2,13,16,17,19–21,23,26–28,33].

Similar to early postnatal exposure to CPF [17] or DZN [33], PTN did not affect locomotor activity in the Figure-8 apparatus. This is a key finding, since it indicates that impairments found in the other behavioral tests are not secondary to depressed motor function. The absence of significant motor deficits was further confirmed by the lack of impairment of response latencies in RAM performance. By itself, this reflects a major difference between the effects of OP exposure in the neonate as compared to the adult, where delayed peripheral neuropathies are a characteristic that affects gait and other motor functions [1]. Indeed, whereas developing animals are more sensitive to adverse effects of OPs on brain development and function, earlier work has shown that they are resistant to delayed peripheral neuropathies [11].

Neonatal PTN exposure failed to elicit any detectable performance deficits in a number of key behavioral tests: T-maze spontaneous alternation, novelty-suppressed feeding, chocolate milk anhedonia test, prepulse inhibition, working and reference memory in the radial-arm maze, and the responses to scopolamine, ketanserin, and mecamylamine challenge. The negative findings stand in stark contrast to the positive effects of CPF or DZN in our earlier studies [2,13,16,17,19,33]. This reinforces the view that the neurobehavioral deficits elicited by neonatal exposure differ substantially among the various OPs, reflecting the predominant role played by mechanisms other than their shared property as cholinesterase inhibitors. Indeed, PTN is an order of magnitude more potent than CPF or DZN as a cholinesterase inhibitor in neonatal rats, producing a parallel reduction in the maximum tolerated dose [28]. In turn, this reduces its ability to disrupt brain development and behavioral performance precisely because the lower doses are less likely to activate the other, cholinesterase-independent mechanisms that participate in OP neurodevelopmental toxicity. This view is reinforced by our earlier neurochemical findings that found substantially smaller initial neural cell damage as well as less substantial long-term alterations in acetylcholine and 5HT synaptic function [22,24,28]. It should be noted that we also did not find any effect of neonatal PTN exposure on the amnestic effect of mecamylamine, but this particular challenge was not studied in our previous work with CPF or DZN, so that we cannot make any direct comparison for the potential role of nicotinic receptors in cognitive performance deficits with those two OPs as compared to PTN.

Animals exposed to the higher PTN dose showed a diminished tactile sensorimotor startle response without changes in sensorimotor gating or motor activity. The mechanism for such a reduction is unknown, but could reflect a reduction in tactile sensory sensitivity. The results for PTN stand in contrast to our prior findings for DZN, which significantly impaired sensorimotor plasticity (reduced PPI), but did not affect tactile startle response. Also, unlike DZN, the effect of PTN was not sex-selective [33].

PTN differentially affected elevated plus maze behavior compared with the other OPs. Exposure to the higher neonatal PTN dose caused a significant increase in the time spent in the open arms, as well as evoking a greater number of center crossings in both sexes. In comparison, for CPF there are similar effects, but restricted to males [2], and DZN evokes a selective decrease in open arm time in males, without affecting center crossings [19]. An increased time spent in the open arms and an increased number of center crossings are typically thought to reflect reduced anxiety, effects that are highly associated with 5HT systems. We recently showed that neonatal exposure to PTN, CPF or DZN all evoke profound alterations in 5HT function [3,24,25], but with major differences among the various agents in terms of overall effect, peak period of sensitivity, sex-selectivity and brain regions affected [28]. We recently compared the ability of the three OPs to elicit immediate changes in 5HT systems after exposure of early postnatal rats to doses spanning the threshold of barely detectable cholinesterase inhibition [28]. Importantly, whereas CPF evoked upregulation of 5HT receptor expression, DZN tended to reduce receptor levels, in keeping with their differences in behavioral effects linked to 5HT systems [2,19]. More recently, we found that comparable exposure to PTN specifically up-regulates 5HT1A receptors in the frontal/parietal cortex, peaking by PND 60 [24], the age at which we tested behavior in the elevated plus maze in our current study. These findings thus demonstrate a strong link between neurochemical and behavioral alterations caused by different OPs, reinforcing the major differences in outcomes evoked by various agents in the same pesticide class.

Perhaps surprisingly, we observed a significant improvement in RAM choice accuracy in the low dose PTN group in both sexes. Again, this differs substantially from the effects of the other OPs. CPF tends to impair performance in males while enhancing performance in females, thus eliminating the normal sex difference in visuospatial memory [2,17]. In contrast, DZN impairs accuracy in both sexes [33], the opposite effect from that of PTN. Notably, though, all three OPs share the same feature of a nonmonotonic dose-effect relationship, where the significant effect occurs at a lower dose, disappearing once the dose is raised to the point where there is significant cholinesterase inhibition [33]. Here, the lower dose of PTN produces only a barely-detectable cholinesterase inhibition (ca. 5–15%) without systemic toxicity, whereas the higher dose produces some loss of viability [28]. A small degree of cholinergic enhancement is known to have a positive trophic effect on neuronal development and plasticity [12,15,18], effects that are likely to be offset by systemic toxicity at the higher PTN dose.

Neonatal exposure to the low dose of PTN elicited a reduction in the amnestic effect of NMDA receptor blockade: at the highest (50 μg/kg) dose of dizocilpine, the PTN-exposed group made fewer working and reference memory errors than controls, without affecting the latency of performance. Numerous investigations consistently demonstrate a critical role of NMDA receptors in working memory performance [9]. While the biologic significance of this loss of sensitivity remains to be explored, there are two likely explanations. PTN exposure could produce a lowered dependence of memory performance on NMDA receptor function, which could account for the lessened responsivity to dizocilpine challenge. In that case, function might be maintained through increased dependence on other mechanisms, which have not yet been characterized in this model. Previously, we have found a similar type of shift in the neural substrate for memory function after developmental OP exposure to CPF, where the loss of cholinergic function involved in RAM performance produced a lowered sensitivity to scopolamine, while at the same time the sensitivity to ketanserin increased because cholinergic function was replaced by serotonergic inputs [2,17]. Alternatively, there may be increased resistance to amnestic effect of the NMDA receptor antagonist dizocilpine, because of increased functional reserve in this system (for example, increased number of NMDA receptors on hippocampal/cortical neurons).

Parathion induced body weight effects were not detected in the current study. The subjects were on food restriction during the appetitive radial-arm maze tests for the majority of the time of the study during which the rats were adults with their full weights. In a companion study, litter mates of the rats in the current study were kept free feeding for the entire period of the study and half of the rats went through a high fat dietary challenge. In that study parathion-induced changes in weight regulation were documented [14].

In conclusion, early postnatal exposure to PTN at doses that elicit barely-detectable cholinesterase inhibition and that span the first signs of systemic toxicity, nevertheless produces lasting behavioral alterations in adolescence and adulthood. However, the effects are far less widespread and distinctly smaller than those elicited by comparable exposures to CPF or DZN. Because neurodevelopmental deficits entail mechanisms unrelated to cholinesterase inhibition, the lower maximum tolerated dose for PTN means that systemic toxicity limits nonsymptomatic exposures to levels substantially lower than those achieved with either CPF or DZN. In conjunction with our earlier neurochemical findings [21,23,28], this reinforces the complete dichotomy between the systemic toxicity of OPs and their propensity to elicit developmental neurotoxicity. Our results thus support the idea that, in the developing brain, the various OPs target specific neurotransmitter systems differently from each other, involving mechanisms over and above their shared property as cholinesterase inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH ES10356.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Abou-Donia MB. Organophosphorus ester-induced delayed neurotoxicity. Annual Review of Pharmacology & Toxicology. 1981;21:511–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.21.040181.002455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldridge JE, Levin ED, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Developmental exposure of rats to chlorpyrifos leads to behavioral alterations in adulthood, involving serotonergic mechanisms and resembling animal models of depression. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:527–531. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aldridge JE, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Developmental exposure to chlorpyrifos elicits sex-selective alterations of serotonergic synaptic function in adulthood: critical periods and regional selectivity for effects on the serotonin transporter, receptor subtypes, and cell signaling. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:148–155. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharya SK, Satyan KS, Chakrabarti A. Anxiogenic action of caffeine: an experimental study in rats. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 1997;11:219–224. doi: 10.1177/026988119701100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodnoff SR, Suranyi-Cadotte B, Aitken DH, Quirion R, Meaney MJ. The effects of chronic antidepressant treatment in an animal model of anxiety. Psychopharmacology. 1988;95:298–302. doi: 10.1007/BF00181937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bodnoff SR, Suranyi-Cadotte BE, Quirion R, Meaney MJ. Role of the central benzodiazepine receptor system in behavioral habituation to novelty. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1989;103:209–212. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.103.1.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Britton DR, Britton KT. A sensitive open field measure of anxiolytic drug activity, Pharmacology. Biochemistry & Behavior. 1981;15:577–582. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(81)90212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casida JE, Quistad GB. Organophosphate toxicology: safety aspects of nonacetylcholinesterase secondary targets. Chem Res Toxicol. 2004;17:983–998. doi: 10.1021/tx0499259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castellano C, Cestari V, Ciamei A. NMDA receptors and learning and memory processes. Current Drug Targets. 2001;2:273–283. doi: 10.2174/1389450013348515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crofton KM, Foss JA, Hass U, Jensen K, Levin ED, Parker SL. Undertaking positive control studies as part of developmental neurotoxicity testing. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2008;30:266–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funk KA, Henderson JD, Liu CH, Higgins RJ, Wilson BW. Neuropathology of organophosphate-induced delayed neuropathy (OPIDN) in young chicks. Arch Toxicol. 1994;68:308–316. doi: 10.1007/s002040050074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hohmann CF. A morphogenetic role for acetylcholine in mouse cerebral neocortex. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:351–363. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Icenogle LM, Christopher NC, Blackwelder WP, Caldwell DP, Qiao D, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA, Levin ED. Behavioral alterations in adolescent and adult rats caused by a brief subtoxic exposure to chlorpyrifos during neurulation. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2004;26:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lassiter TL, Ryde IT, MacKillop EA, Bodwell BE, Brown KK, Levin ED, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Early-life exposure to parathion elicits sex-selective reprogramming of metabolic function and alters the response to a high-fat diet in adulthood. Environ Health Perspect. 2008 doi: 10.1289/ehp.11673. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauder JM, Schambra UB. Morphogenetic roles of acetylcholine. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107(Suppl 1):65–69. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107s165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levin ED, Addy N, Baruah A, Elias A, Christopher NC, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Prenatal chlorpyrifos exposure in rats causes persistent behavioral alterations. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2002;24:733–741. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(02)00272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin ED, Addy N, Nakajima A, Christopher NC, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Persistent behavioral consequences of neonatal chlorpyrifos exposure in rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2001;130:83–89. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(01)00215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meck WH, Williams CL. Characterization of the facilitative effects of perinatal choline supplementation on timing and temporal memory. Neuroreport. 1997;8:2831–2835. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199709080-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roegge CS, Timofeeva OA, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA, Levin ED. Developmental diazinon neurotoxicity in rats: later effects on emotional response. Brain Res Bull. 2008;75:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy TS, Sharma V, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Quantitative morphological assessment reveals neuronal and glial deficits in hippocampus after a brief subtoxic exposure to chlorpyrifos in neonatal rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2005;155:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slotkin TA, Bodwell BE, Levin ED, Seidler FJ. Neonatal exposure to low doses of diazinon: long-term effects on neural cell development and acetylcholine systems. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:340–348. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slotkin TA, Bodwell BE, Ryde IT, Levin ED, Seidler FJ. Exposure of neonatal rats to parathion elicits sex-selective impairment of acetylcholine systems in brain regions during adolescence and adulthood. Environ Health Perspect. 2008 doi: 10.1289/ehp.11451. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slotkin TA, Levin ED, Seidler FJ. Comparative developmental neurotoxicity of organophosphate insecticides: effects on brain development are separable from systemic toxicity. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:746–751. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slotkin TA, Levin ED, Seidler FJ. Developmental neurotoxicity of parathion: Progressive effects on serotonergic systems in adolescence and adulthood. Neurotoxicology and Teratology under review. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slotkin TA, Ryde IT, Levin ED, Seidler FJ. Developmental neurotoxicity of low-dose diazinon exposure of neonatal rats: Effects on serotonin systems in adolescence and adulthood. Brain Res Bull. 2008;75:640–647. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slotkin TA, Seidler FJ. Comparative developmental neurotoxicity of organophosphates in vivo: transcriptional responses of pathways for brain cell development, cell signaling, cytotoxicity and neurotransmitter systems. Brain Res Bull. 2007;72:232–274. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slotkin TA, Seidler FJ, Fumagalli F. Exposure to organophosphates reduces the expression of neurotrophic factors in neonatal rat brain regions: similarities and differences in the effects of chlorpyrifos and diazinon on the fibroblast growth factor superfamily. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:909–916. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slotkin TA, Tate CA, Ryde IT, Levin ED, Seidler FJ. Organophosphate insecticides target the serotonergic system in developing rat brain regions: Disparate effects of diazinon and parathion at doses spanning the threshold for cholinesterase inhibition. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1542–1546. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical Methods. Iowa State University Press; Ames, Iowa: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swerdlow N, Geyer M, Braff D. Neural circuit regulation of prepulse inhibition o startle in the rat: Current knowledge and future challenges. Psychopharmacology. 2001;156:194–215. doi: 10.1007/s002130100799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swerdlow NR, Braff DL, Geyer MA. Animal models of deficient sensorimotor gating: what we know, what we think we know, and what we hope to know soon. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2000;11:185–204. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200006000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swerdlow NR, Martinez ZA, Hanlon FM, Platten A, Farid M, Auerbach P, Braff DL, Geyer MA. Toward understanding the biology of a complex phenotype: rat strain and substrain differences in the sensorimotor gating-disruptive effects of dopamine agonists. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4325–4336. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04325.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Timofeeva OA, Roegge CS, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA, Levin ED. Persistent cognitive alterations in rats after early postnatal exposure to low doses of the organophosphate pesticide, diazinon. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2008;30:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitney KD, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Developmental neurotoxicity of chlorpyrifos: Cellular mechanisms. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1995;134:53–62. doi: 10.1006/taap.1995.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]