Abstract

One of the most commonly used recombinant antibody formats is the single-chain variable fragment (scFv) that consists of the antibody variable heavy chain connected to the variable light chain by a flexible linker. Since disulfide bonds are often necessary for scFv folding, it can be challenging to express scFvs in the reducing environment of the cytosol. Thus, we sought to develop a method for antigen-independent selection of scFvs that are stable in the reducing cytosol of bacteria. To this end, we applied a recently developed genetic selection for protein folding and solubility based on the quality control feature of the Escherichia coli twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway (Fisher et al., 2006 Protein Sci). This selection employs a tripartite sandwich fusion of a protein-of-interest with an N-terminal Tat-specific signal peptide and C-terminal TEM1 β-lactamase, thereby coupling antibiotic resistance with Tat pathway export. Here, we adapted this assay to develop intrabody selection after Tat export (ISELATE), a high-throughput selection strategy for the identification of solubility-enhanced scFv sequences. Using ISELATE for three rounds of laboratory evolution, it was possible to evolve a soluble scFv from an insoluble parental sequence. We also show that ISELATE enables focusing of an scFv library in soluble sequence space prior to functional screening and thus can be used to increase the likelihood of finding functional intrabodies. Finally, the technique was used to screen a large repertoire of naïve scFvs for clones that conferred significant levels of soluble accumulation. In these ways, we show that the Tat quality control mechanism can be harnessed for molecular evolution of scFvs that are soluble in the reducing cytoplasm of E. coli.

Introduction

Antibodies and engineered antibody fragments play a prominent role in research and therapeutic applications.1 One of the most commonly used recombinant antibody formats is the single-chain variable fragment (scFv) that consists of the antibody variable heavy (VH) and variable light (VL) chains connected by a flexible linker.2; 3 It has been established that intradomain disulfides contribute about 4-6 kcal/mol to the stability of an scFv molecule4 and are normally formed only after the scFv is exported from the cytoplasm to a more oxidative environment such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of eukaryotes or the periplasm of bacteria. In the bacterial periplasm, enzymes maintain an oxidizing environment via electron flow between the periplasmic protein DsbA and the inner membrane protein DsbB.5 From a production standpoint, periplasmic scFv yields are often low6; 7 due to limitations of the transport process and a lack of ATP dependent chaperones to aid in protein folding. The cytoplasm is often the compartment of choice for protein expression but is insufficient for biosynthesis of scFvs and other disulfide-containing proteins because it is maintained as a highly reducing environment that disfavors the formation of disulfide bonds.8 Indeed, most scFvs exhibit poor stability and solubility when expressed in the cytoplasm.9; 10; 11 However, a number of reports have identified intracellular antibody (intrabody) sequences that retain their structure and function in the face of this reducing environment.12; 13; 14 Intrabodies have garnered considerable attention recently because ectopic expression of these molecules inside of living cells enables highly-specific binding to target antigens and the exertion of a specific biological effect (e.g., visualization or inhibition of a target).15; 16; 17; 18 Thus, intrabodies hold promise in the area of functional genomics - as a protein analog to interfering RNA (RNAi)19 - and in the treatment of human disease through gene therapy, stem cell therapy, and via direct therapeutic delivery to cells.12; 20; 21

In reports where intrabodies exerted biological effects, it has been demonstrated that performance correlated positively with in vitro stability whereas binding affinity appeared to play only a minor role.11; 22 However, since most intrabodies are isolated based on their affinity for a given target and not on their folding properties per se, further optimization of intracellular stability is usually required. Indeed, even after targeting to the ER, a compartment containing protein disulfide isomerase and chaperones, intrabodies can still exhibit defects in stability that in some cases prevented phenotypic knockout.23; 24 An unfortunate bottleneck in the discovery of soluble intrabodies is the fact that most affinity-based selection systems, such as phage,25 ribosome,26 yeast,27 and bacterial28 display, do not account for folding stability in a reducing environment during the selection process and thus are of limited utility for the isolation of soluble intrabodies.

A variety of techniques have been developed to overcome the difficulties associated with stable expression of intrabodies. One strategy is to modify the cytoplasmic redox potential of the host strain by mutating components of the thioredoxin and glutaredoxin pathways.29 However, while accumulation of soluble antibody fragments has been observed,30; 31; 32 this approach results in low scFv yields and requires the use of a unique strain of E. coli (e.g., FÅ113) that is not practical for isolating intrabodies that will eventually be applied in other cell types. Alternatively, C-terminal fusions to the mature portion of E. coli maltose binding protein (MBP) have been shown to stabilize scFvs expressed in the bacterial and mammalian cytoplasm.33; 34 However, the utility of a fusion protein is limited to bacterial expression and non-therapeutic applications. In fact, bacterial MBP is highly immunogenic in humans, and elicits both B-cell and T-cell responses.35 A third strategy is to perform rounds of mutation and selection to identify scFv sequences that fold efficiently in an intracellular compartment. The challenge here is the development of selections based on the intracellular folding properties of a protein, independent of specific ligand binding. It is imperative that these selections are able to search large volumes of sequence space because mutations stabilizing the structure of scFvs in the cytoplasm are rare events.36; 37; 38 In one notable example, Barberis and coworkers developed a modified yeast 2-hybrid approach whereby a selectable marker was fused to a target scFv as an antigen-independent reporter of solubility.39 This selection tool was subsequently used to screen scFv libraries for the identification of stable and soluble frameworks.40 Similar laboratory evolution approaches using folding reporter enzymes have been employed in E. coli to increase soluble expression of foreign proteins,41; 42; 43; 44 however, these methods have shown limited success when applied to the selection of solubility-enhanced scFv variants from large combinatorial libraries.7; 45 Thus, there remains a general lack of bacterial methods for antigen-independent selection of scFvs that are stable in the reducing cytosol.36; 38; 46 To address this shortcoming, we employed a recently developed selection assay based on the intrinsic protein folding quality control mechanism of the bacterial twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway47 to engineer intrabodies. This selection assay employed a tripartite sandwich fusion of a protein-of-interest (POI) with an N-terminal Tat-specific signal peptide (ssTorA) and C-terminal TEM1 β-lactamase (Bla), thereby coupling antibiotic resistance with Tat pathway export (see Fig.1a). We adapted this assay to develop intrabody selection after Tat export (ISELATE), a high-throughput selection strategy for facile identification of solubility-enhanced scFv sequences. The rationale for this strategy is that improved substrate solubility,47 folding rate,48 and surface hydrophilicity49 results in enhanced export by the Tat pathway. Thus, ISELATE is a method for selecting clones with greatly enhanced Tat export efficiency, to which correct folding and solubility are key contributors. By employing laboratory evolution using ISELATE, we were able to successfully identify soluble intrabodies in the cytoplasm of E. coli from large libraries of insoluble scFvs.

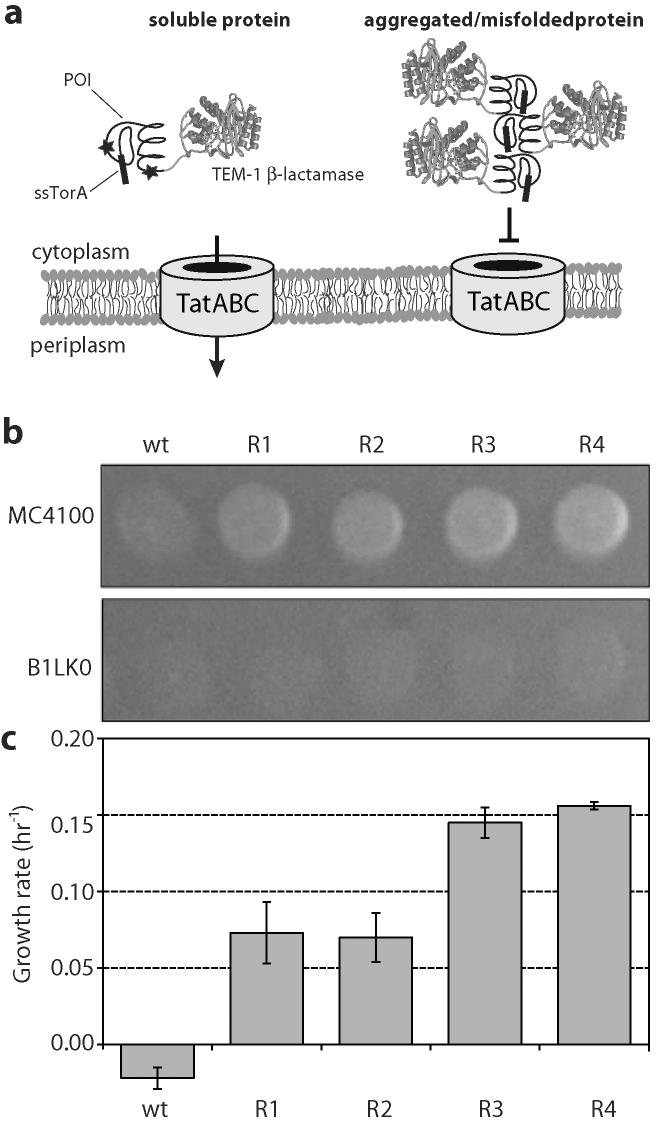

Figure 1. Ampicillin resistant phenotypes and scFv solubility.

(a) Cartoon of a sandwich fusion of a protein-of-interest (POI) to an N-terminal Tat specific signal peptide (ssTorA) and a C-terminal TEM1 β-lactamase (Bla) (b) Spot plates of 5-μL aliquots of MC4100 and B1LK0 cells expressing ssTorA-scFv13-Bla variants (WT, R1, R2, R3, and R4; plus BL1 isolated for intracellular function) on LB media. Overnight cultures were diluted and spotted on plates supplemented with 100 μg/mL Amp. (c) Growth rate in liquid LB supplemented with 100 μg/mL Amp. Error bars represent the standard error of 6 independent trials.

Results

Assaying the solubility of engineered scFvs using the Tat folding reporter

As proof-of-concept, we began with four well-characterized mutants of an anti β-galactosidase scFv (scFv13), engineered previously for high-level soluble expression in the cytoplasm of E. coli.38 These mutants display increasing levels of solubility, in the order: wild-type (wt) scFv13, scFv13-R1, scFv13-R2, scFv13-R3, and scFv13-R4. The wt scFv13 was originally isolated based on its affinity for E. coli β-galactosidase (β-gal) and its ability to activate a mutant β-gal known as AMEF 959 β-gal. Clones R1-R4 were subsequently evolved from wt scFv13 following 1-4 rounds, respectively, of functional in vivo selection (i.e., cells with AMEF 959 β-gal plated on limiting lactose).38 Although functional intrabodies were successfully isolated, this method was specific to only one very unique antigen. Furthermore, it was recently reported that a folding selection using complementing β-gal fragments as a reporter was incapable of antigen-independent isolation of soluble scFv13 variants.46 Thus, we sought to develop a universal antigen-independent strategy for intrabody isolation. We opted to use a genetic selection for protein folding and solubility based on the intrinsic quality control feature of the Tat pathway that was developed previously in our laboratory.47 This selection employed a tripartite sandwich fusion of an N-terminal Tat specific signal peptide (ssTorA) followed by a protein-of-interest (POI) fused to a C-terminal TEM1 β-lactamase (Bla) (Fig. 1a). If the POI folds properly in the cytoplasm, the fusion is transported to the periplasm where it confers an ampicillin (Amp) resistant phenotype to cells. To determine whether isolation of soluble scFv13 variants might be possible via Tat selection, we first examined each of the scFv13 variants R1-R4 as the POI and characterized the Amp resistance phenotype conferred to cells. Consistent with our earlier findings,47 we observed increasing Amp resistance in cells expressing increasingly more soluble scFv13 fusions (Fig. 1b and c). The most soluble clone, scFv13-R4, conferred the greatest resistance to cells. Cell expressing the scFv13 variants were significantly less resistant to Amp when expressed as the POI in a ΔtatC strain (B1LK050) lacking a functional Tat pathway (Fig. 1b), suggesting Tat-dependent routing for each of these constructs.

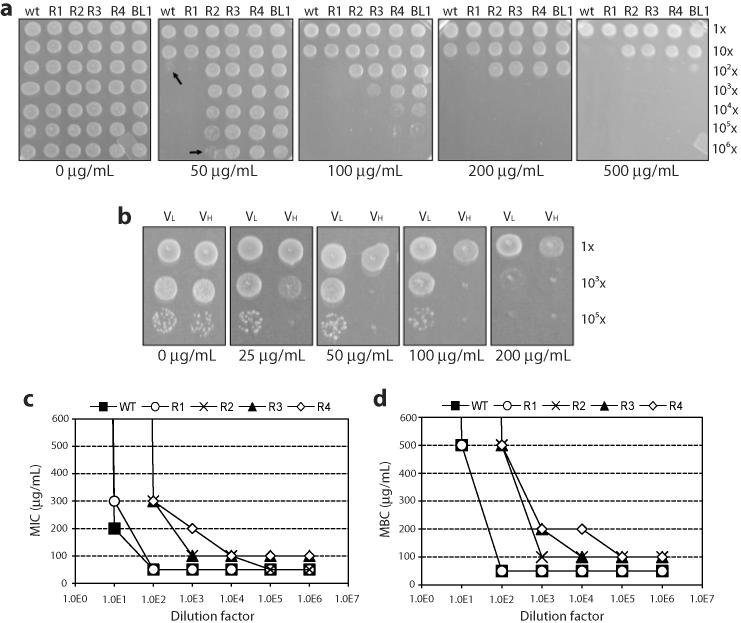

Further, it has been hypothesized38 and there is some experimental evidence to suggest36 that the VH domain limits the soluble expression of scFv13. To determine which chain was limiting scFv solubility, we examined the resistance phenotype of cells independently expressing either the VH or VL domain of wt scFv13 in the POI position of our Tat folding reporter. As hypothesized, cells expressing the VH domain exhibited low soluble expression as evidenced by sensitivity of dilute cells to 25 μg/mL Amp (Fig. 2b), while cells expressing the VL domain exhibited resistance up to 100 μg/mL Amp. This provides further evidence that the VH domain limits soluble expression of scFv13.

Figure 2. Quantitative ampicillin resistance as an indicator of scFv solubility.

(a) Spot plates of 5-μL aliquots of MC4100 cells expressing ssTorA-scFv13-Bla variants on LB media. Overnight cultures were diluted in successive 10-fold dilutions (top-to-bottom) and spotted on increasing concentrations of Amp (left-to-right). Step diagram of both the (b) MIC and (c) MBC resistance profiles plotted as Amp concentration vs. dilution factor. (d) Spot plates of 5- μL aliquots of MC4100 cells expressing ssTorA-VL-Bla and ssTorA-VH-Bla variants on LB media. Overnight cultures from a 96-well plate were diluted 10-fold and then in successive 100-fold dilutions (top-to-bottom) and spotted on increasing concentrations of Amp (left-to-right).

Development of ISELATE, an empirical scFv selection strategy

Since Amp resistance correlated with scFv solubility, we expected that molecular evolution of a soluble scFv13 would be possible with Tat selection. Since this evolution would be performed in an affinity-independent context, we desired an empirical method for antibiotic selection. As opposed to a screen, the benefits of a selection include greatly increased throughput, ease and low cost. The argument against selections is that, by definition, they apply tremendous pressure to evolutionary systems and can promote false positives.51; 52 Indeed, we observed several times in early generation libraries and thereafter that a significant fraction (>>50%) of mutants selected at elevated Amp concentrations (100-500 μg/mL) contained either none or very small segments (encoding <30 amino acids) of the scFv coding region (data not shown). We believe this may be the result of an intracellular phenomenon as numerous attempts by us and others (G. Guntas and B. Kuhlman, personal communication) to eliminate these false-positive clones during library construction were unsuccessful. We consistently isolated these artifacts with a frequency of ~1/105 (0.001%) in the naïve library and they conferred resistance up to 1.5 mg/mL Amp. While this representation in the naïve library is relatively low compared to other published reports,53 we believe that it is unavoidable and problematic for selections of 106-107 library members with rare true positives (~1 in 105).38

To avoid false positives, we developed an empirical scheme of evolution based on a quantitative method of selection and counter-screening that in theory can be applied universally to selection-based evolution. First, we reasoned that the antibiotic resistance of a cell population on plates is not only dependent on antibiotic concentration, but also on the number of colony forming units (CFUs) and surface area. To examine the relationship between these variables, we evaluated spot plates in which surface area was fixed by the volume of the spot (5 μL), and both the dilution factor of the cell culture (i.e., CFU) and the antibiotic concentration were varied (Fig. 2a). We then plotted the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bacteriocidal concentration (MBC) of each dilution to generate a resistance profile for each variant (Fig. 2c and d). From the quantitative data gained from these diagrams, we reasoned that the two best ways to avoid abundant false positives were to: (1) select for positive clones using modest increases in antibiotic concentration during evolution (i.e., including true positives and false positives) and (2) counter-screen against clones that conferred antibiotic resistance significantly beyond the continuum distribution (i.e., excluding false positives). For the former, we reasoned that our first-round evolution experiments should be performed by selecting on 50 μg/mL Amp at <1.8 ×105 CFU/cm2. This is because a dilution factor of 102 represents ~1.8 ×105 CFU/cm2 (see Fig. 2a). Dilute cells expressing fusions of R2, R3, and R4 were resistant whereas concentrated cells expressing wt and R1 were sensitive to this concentration of Amp (see black arrows, Fig. 2a). For the latter, we reasoned that in this instance we were unlikely to isolate variants exhibiting high-level Amp resistance (e.g., ≥200 μg/mL Amp) in a single round of selection, as none of the soluble scFv13 variants conferred resistance to even concentrated cells (dilution factor 103 ~1.8×104 CFU/cm2) on this level of Amp. Since there is a balance between selection pressure and the rate of false positives, these counter-screening conditions put an effective upper limit on the improvements achievable during a single round of evolution.

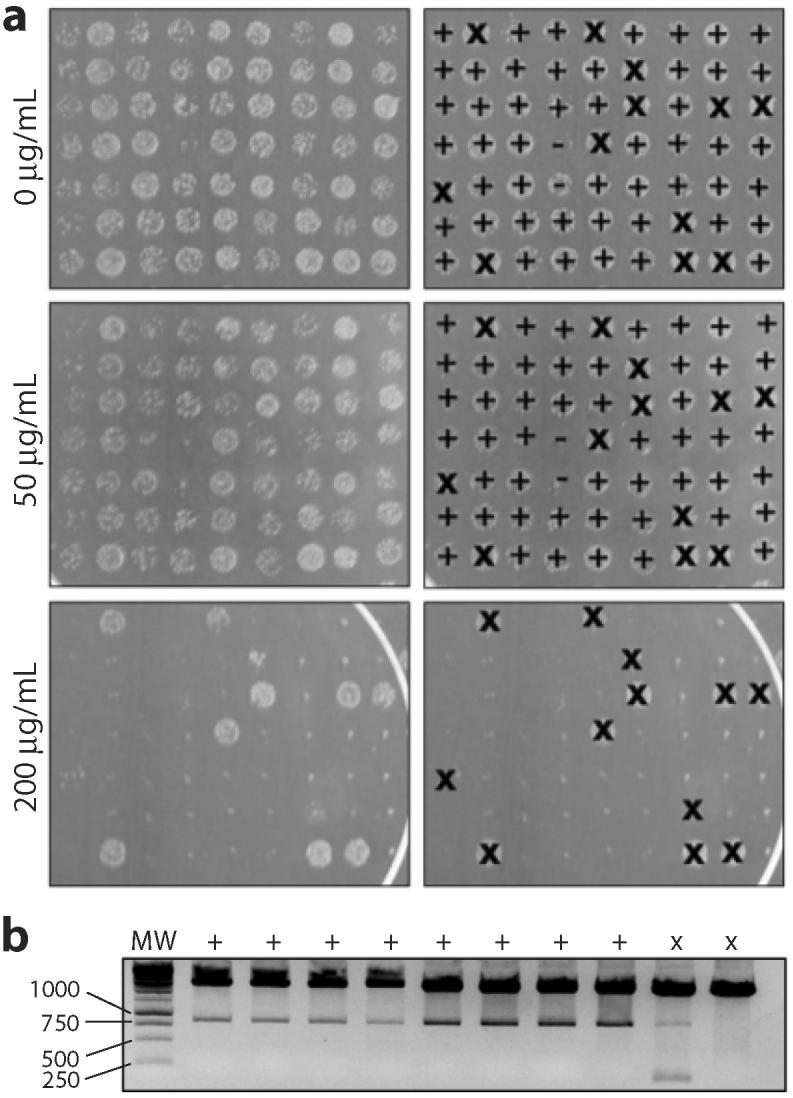

To test our selection logic, we synthesized a library of randomized scFv13 variants in the POI position of the Tat selection vector. This resulted in a library of ~1.1×106 members with ~1% amino acid error rate (Table 1). We plated ~1.0×106 CFUs from the library on 150 mm diameter plates (<1.0×104 CFU/cm2) supplemented with 50 μg/mL Amp and found 249 viable colonies following overnight incubation (0.025% of the naïve library). We picked 96 of these colonies in a 96-well plate for simultaneous phenotypic confirmation and counter-screening. For initial confirmation, clones from the 96-well plate were spotted at a dilution of <1.0×104 CFU/cm2 on 50 μg/mL Amp to confirm the original resistance phenotype (Fig. 3a). For counter-screening, we replica spotted these clones on 200 μg/mL Amp plates (Fig. 3a) to identify and eliminate false positives. Of the 96 colonies, 17 were resistant to 200 μg/mL Amp while 76 were resistant to only 50 μg/mL Amp. According to this same ratio, we picked 8 colonies that we predicted to be true positives and 2 colonies that we predicted to be false positives containing no inserts or very small segments corresponding to the scFv coding region. Following isolation of the plasmids and digestion with restriction enzymes, it was revealed that the 8 putative true positives carried full-length scFv13 inserts and the 2 putative false positives did not (Fig. 3b). Thus, by selecting empirically we increased the number of true positives that were isolated from <<50% to ~80% and by counter-screening we identified contaminating false positives. Collectively, these steps ensured that selections were made along the continuum distribution of the library population, and through the course of these experiments we never came across another small fragment false positive. Importantly, this simple ISELATE protocol took no longer than the normal confirmation of library results and greatly enriched the quality of isolated clones.

Table 1.

Summary of scFv library construction, diversity and selection conditions.

| Amp concentration (μg/mL) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Library | Method | ~Diversitya | ~CFU/cm2b | Selection | Counter-screen |

| Round 1 | Doped Mg | 1.1×106 | 5.7×103 | 50 | 200 |

| Round 2 | Mutazyme II | 7.1×106 | 8.9×103 | 200 | 400 |

| Round 3 | Mutazyme II | 5.1×106 | 1.1×104 | 400 | 600 |

~1% error rate at the DNA level in each library

Selected on 150 mm diameter plates

Figure 3. Confirmation of phenotype and counter-screening of false positives.

(a) Spot plates of 5-μL aliquots of MC4100 cells expressing selected variants on LB media. Overnight cultures were diluted 104-fold and spotted on 0, 50, 200 μg/mL Amp. Spots were identified by phenotype as true positives (+), false positives (×), or unconfirmed (-). Note that cultures were not normalized by 600 nm absorbance prior to spotting. (b) Plasmids isolated from eight true positives and two false positives were restriction digested. The true positives (+) showed the presence of full-length genes while the false positives (×) showed either the presence of a small fragment or no gene insertion.

Antigen-independent molecular evolution of a solubility-enhanced scFv

Of the 8 true positives identified above in the first round of selection, 7 contained an E6V substitution in the VH domain (H6 E-V; Table 2). Clone T1 was chosen for further rounds of evolution. Specifically, we subjected T1 to two further rounds of mutagenesis followed by selection/counter-screening on 200/400 μg/mL during round 2 and 400/600 μg/mL during round 3 (Fig. 4a-c; for library details see Table 1). Analysis of the chosen clones from each round revealed the following: clone T1 carried the mutations H6 E-V / L51 G-D / L79 Q-R; clone T2 picked up the additional mutations H97 I-N / H100 G-S; and clone T3 acquired the additional mutations H18 L-M / H19 R-I / H82 N-D. None of these selected clones showed increased resistance when expressed in Tat-deficient B1LK0 cells (data not shown).

Table 2.

Summary of solubility-enhanced scFv13-T3 mutations.

| Hydrophobicitv scoreb | Side chain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | Kabata | Secondary structure | Framework | Solvent accessible (>30%) | WT residue | Mut residue | WT residue | Mut residue |

| E-V | H6 | Strand 1 | FR1 | N | -3.5 | 4.2 | Acidic | Neutral |

| L-M | H18 | Strand 2 | FR1 | N | 3.8 | 1.9 | Neutral | Neutral |

| R-I | H19 | Strand 2 | FR1 | Y | -4.5 | 4.5 | Basic | Neutral |

| N-D | H82 | Strand 7 | FR3 | N | -3.5 | -3.5 | Neutral | Acidic |

| I-N | H97 | Loop 8/9 | CDR3 | Y | 4.5 | -3.5 | Neutral | Neutral |

| G-S | H100 | Loop 8/9 | CDR3 | N | -0.4 | -0.8 | Neutral | Neutral |

| G-D | L51 | Loop 5/6 | CDR2 | N | -0.4 | -3.5 | Neutral | Acidic |

| Q-R | L79 | Strand 8; Loop 8/9 | FR3 | N | -3.5 | -4.5 | Neutral | Basic |

Wu and Kabat (1970) J Exp Med: 132, 211-250.

Kyte and Doolittle (1982) J Mol Biol 157:105.

Figure 4. Evolution of a soluble scFv13 variant.

(a) Spot plates of 5-μL aliquots of MC4100 cells expressing ssTorA-scFv13-Bla variants on LB media. Overnight cultures were diluted in successive 10-fold dilutions (top-to-bottom) and spotted on increasing concentrations of Amp (left-to-right). Step diagram of both the (b) MIC and (c) MBC resistance profiles plotted as Amp concentration vs. dilution factor.

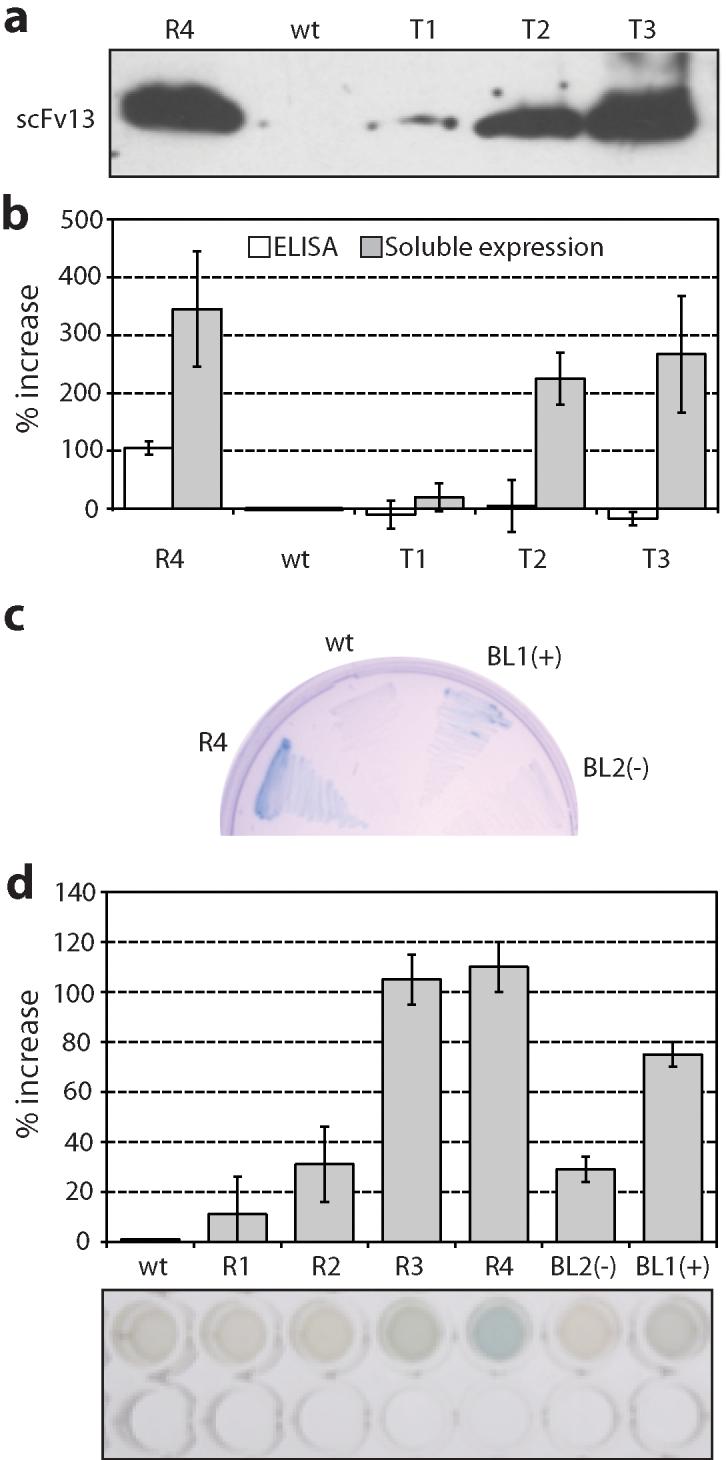

We hypothesized that these evolved variants would display increased soluble expression in the E. coli cytoplasm. To test this, we examined the soluble accumulation of the scFvs during high-level expression without the N-terminal Tat signal peptide or the C-terminal Bla fusion. Specifically, each variant was subcloned into pET28a and expressed in BL21(DE3) cells. As expected, the soluble expression of the clones increased following each round of evolution (Fig. 5a and b) in a manner that directly coincided with the Amp resistance conferred by each clone (Fig. 4a-c). To our knowledge, this represents the first antigen-independent selection of soluble scFvs expressed in the E. coli cytoplasm. Interestingly, when clones T1, T2, and T3 were expressed from the pPM160 vector in AMEF 959 cells to assay for in vivo function, AMEF β-gal activation was indistinguishable from that observed for the same cells expressing wt scFv13 (data not shown). This observation suggests that the antigen binding activity of these scFv variants was not improved by the introduction of solubility-enhancing mutations. ELISA analysis of soluble whole cell lysates from cells expressing clones T1, T2 and T3 indicates that these solubility-enhancing mutations did not improve scFv function (Fig. 5b) and corroborates our in vivo observations. We believe this is due to an intrinsic tradeoff between folding and function that is independent of method and a byproduct of evolutionary folding pressure.

Figure 5. Activity of affinity-independent and affinity-dependent evolved scFv13s.

(a) A Western blot of the soluble lysate from BL21(DE3) cells expressing the indicated scFv13s appended with a c-myc affinity tag. (b) Densitometry of bands from three separate Western blots on the soluble cell lysate reported as percent increase relative to wt (gray bars) and percent increase in ELISA signal relative to wt on β-gal plates (white bars). (c) AMEF 959 cells expressing scFv13 R4, WT, BL1 (selected as a positive during functional screen, +), and a clone BL2 selected as nonfunctional (-) plated on X-gal. (d) AMEF 959 cells expressing scFv13 mutants in liquid culture supplemented with X-gal. In vivo activity is measured as the percent increase in 595 nm absorbance relative to wt. Error bars represent the standard error of 6 independent trials. (e) Image of a representative 96-well plate β-gal assay; top lane corresponds to samples as in (d) and bottom lane corresponds to empty control wells for comparison.

Solubility focusing of an scFv library prior to affinity selection

Unlike the antigen-dependent isolation of scFv13 variants R1-R4 by Martineau et al.,38 we observed no measurable improvement in binding activity for clones T1-T3 relative to wt scFv13 despite their improved solubility profile. This was not entirely unexpected considering that our folding selection was performed on scFvs in the absence of their cognate antigen. Therefore, we next explored whether Tat-based selection could be used as a tool to focus a naïve scFv library in soluble sequence space prior to affinity selection. Such focusing would be advantageous considering the likelihood of finding a functional intracellular scFv13 from a randomized library is low (~1/105).38 We hypothesized that functional scFv13 sequences could be efficiently identified by first passing a randomized library through the Tat selection prior to applying a functional screen. To test this notion, ~2.8×107 cells of the Round 1 library, representing >25-fold library coverage, were plated at ~1.6×105 CFU/cm2 directly onto a highly selective (500 μg/mL Amp) medium and the resulting collection of 713 colonies was pooled directly from selection plates. Although a high portion of these clones (~90%) were predicted to be false positives for reasons explained above, we postulated that a functional screening step should eliminate these contaminants. The genes encoding the scFv13 clones from the solubility focusing step were subcloned in an unfused format in the pPM160 vector. The resulting sublibrary was transformed into AMEF 959 cells and in vivo functional screening was performed by plating on X-gal indicator plates. In AMEF 959 cells, functional intracellular scFvs bind and activate mutant β-gal conferring a blue color to colonies on X-gal indicator plates. Of 625 plated colonies whereby each putative full-length mutant was overrepresented (~9x coverage), three clones were isolated for their observed blue color above background (Fig. 5c and d). All three clones were identical (H6 E-V / H40 A-V / L51 G-D) encoding the scFv13 variant we termed BL1 that differed from scFv13-T1 by only the presence of the H40 A-V substitution and the absence of the L79 Q-R substitution. This suggests that L79 Q-R may compromise the activity of the scFv while H40 A-V conserves and/or enhances it. It is also noteworthy that the L51 G-D mutation is present in clones BL1, T1 and R4. Importantly, the BL1 variant not only displayed intracellular activity enhancement, but also conferred increased Amp resistance when back-checked in the Tat selection assay (Fig. 2a). Taken together, this experiment suggests that evolution for solubility and affinity can be done sequentially to ensure both properties are maintained in an evolved scFv.

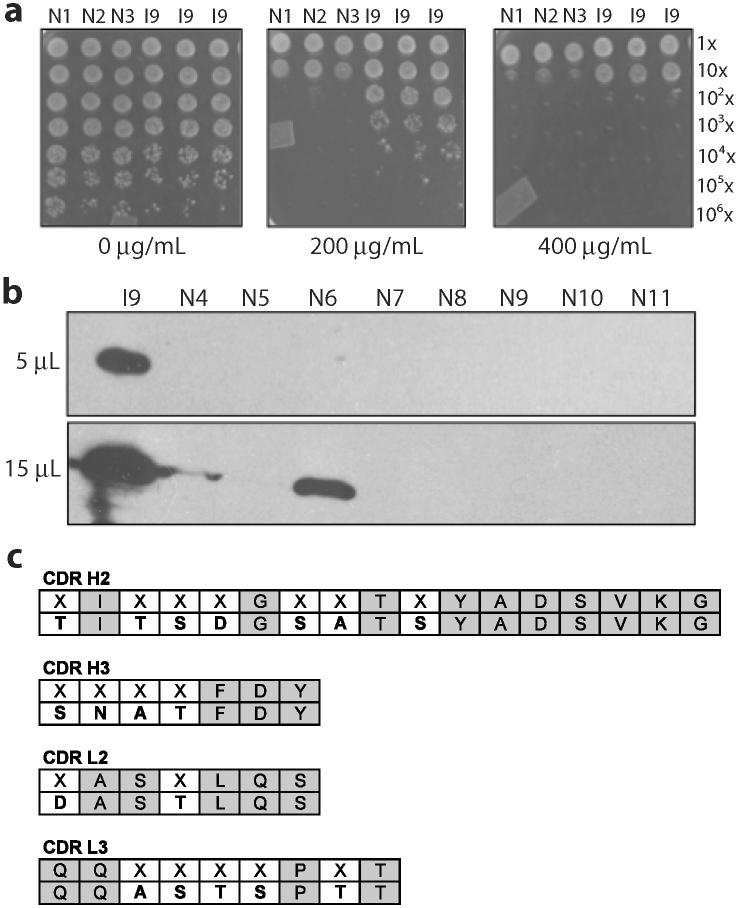

Using ISELATE to identify soluble scFvs from the Tomlinson library

scFv13 was an ideal candidate for solubility evolution because there was a known evolutionary trajectory to soluble sequence space. The behavior of wt scFv13 and R4 informed our selections. However, as a true test of the selection assay, we next attempted to select a soluble scFv from the Tomlinson I library. The Tomlinson I library is a repertoire of 1.5×108 human scFvs with diversity enabled by degenerate codons (by the mixed bases, DVT) in 18 diverse positions in antigen binding sites.54 While the diversity is constrained to discrete structural regions within the antigen binding site, we were optimistic of isolating soluble clones because scFv13-T3 above contained 3 out of 8 mutations in the complementarity determining regions (CDRs) (see Table 2). For this experiment, we constructed a library of Tomlinson I scFvs encoded in pSALect and plated 5.2×106 transformed cells on 150 mm agar plates. Since we did not have negative and positive controls to inform the selection, we supplemented the agar plates with varying concentrations of Amp (50, 100, 200, 400 and 600 μg/mL). We observed a light lawn on the 100 μg/mL plate, 658 colonies on the 200 μg/mL plate and only 173 colonies on the 400 μg/mL plate. We picked 24 colonies from each of the 100 and 200 μg/mL plates to confirm phenotype and counter-screen. Following 200/400 μg/mL Amp selection/counter-screening, we successfully sequenced 6 clones that exhibited the desired phenotypic behavior. Sequencing revealed that 5 out of 6 encoded only 18 amino acids of the heavy chain followed by the (Gly4Ser)3 linker and the light chain in its entirety. Since there were no notable amino acid patterns in any of these clones, we concluded that the light chain alone is reasonably soluble. Indeed, this was the case for wt scFv13 (Fig. 2b; see also the Discussion). Importantly, we did recover a full-length scFv (scFvI9) that behaved as expected during selection/counter-screening (Fig. 6a). To examine the soluble accumulation of scFvI9 during high-level expression without the N-terminal Tat signal peptide or C-terminal Bla fusion, we cloned this scFv into pET28a and expressed it in BL21(DE3) cells. For comparison, we selected 8 scFvs at random from the naïve Tomlinson I library and examined their soluble expression in an identical manner. As expected, scFvI9 was significantly more soluble than any of the naïve scFvs (Fig. 6b). In fact, only in overloading the gel with soluble lysate were any naïve scFvs detectable (N6, Fig. 6b). Relative to the naïve population, scFvI9 has an abundance of the neutral, polar amino acids serine and threonine (Fig. 6c). These residues may be preferred in solvent exposed CDR loops and thus confer increased solubility to the scFv.

Figure 6. Isolation of a soluble scFv from the Tomlinson I library.

(a) Spot plates of 5-μL aliquots of three cultures of MC4100 cells expressing scFvI9 spotted next to three cultures expressing arbitrary scFvs from the naïve Tomlinson I library in pSALect on LB media. Overnight cultures were diluted in successive 10-fold dilutions (top-to-bottom) and spotted on increasing concentrations of Amp (left-to-right). (b) Western blot analysis of 5 μL and 15 μL of soluble lysate from BL21(DE3) cells expressing scFvI9 and eight naïve scFvs from the Tomlinson I library appended with a c-myc affinity tag. (c) Sequence of clone I9 with diversity encoded at 18 positions, indicated with Xs, in four CDRs.

Discussion

We have shown that ISELATE is a highly effective protocol for evolving solubility-enhanced scFvs from large libraries. The assay builds on our earlier selection strategy using the Tat pathway as a biosynthetic filter for protein sequences that are correctly folded and soluble. In this earlier work, we were able to isolate soluble variants of the Aβ42 peptide in a single round of selection, which was relatively straightforward because the parental Aβ42 sequence did not confer any measurable growth to cells. Here, we have significantly advanced the selection strategy by demonstrating two important but untested concepts. First, we show that the assay can be used to evolve globular proteins that have a folded structure. In the case of the Aμ42 peptide, the evolved target was a short (42 residues), aggregation-prone peptide that does not have a folded state per se. Thus, the demonstration that solubility-enhanced variants of a large, globular protein can be “proofread” and exported by the Tat system is a significant advance over the early work. Second, selection of soluble variants from a completely insoluble starting sequence, such as in the case of Aβ42, was relatively easy due to the simplicity of discriminating between the growth/no growth phenotypes. However, an open question was whether increased selection pressure could be used to further evolve solubility, especially in cases where the starting sequence already had measureable solubility (i.e., conferred growth to cells). This is important not only for solubility maturation, as we showed here for the scFv13 sequence, but also for cases where one desires to create a “super-soluble” protein from a starting protein that already exhibits moderate in vivo solubility. By properly identifying selection conditions relative to a wild-type clone and counter-screening to eliminate contaminating fragments, we showed that it was possible to perform antigen-independent solubility maturation of scFvs directly in the E. coli cytoplasm.

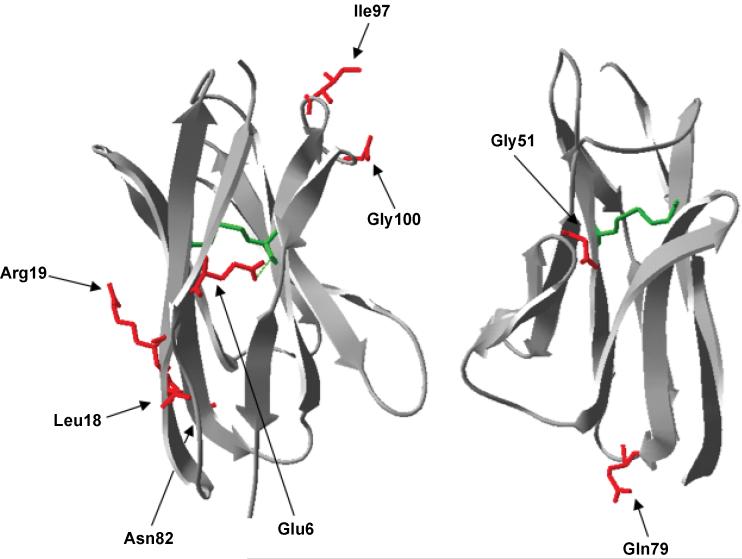

In parallel, by selecting prior to functional screening, we showed that it was also possible to focus scFv sequences in regions of sequence space that facilitated isolation of functional intrabodies. The substitutions found in the scFv13 variants have led to several interesting observations (see Table 2 and Fig. 7). For instance, the soluble clone T3 possesses 6 out of 8 mutations in the VH domain. Further, 6 out of 7 mutations in scFv13-R4 are located in the VH domain. In light of this it was hypothesized38 and suggested36 that this domain limits the soluble expression of the scFv. Here, we examined the resistance phenotype of cells independently expressing either the VH or VL domain of wt scFv13 in the POI position of our Tat folding reporter. As hypothesized, cells expressing the VH domain exhibited low soluble expression as evidenced by sensitivity to low concentrations of Amp (Fig. 2b). This provides further evidence that the VH domain limits soluble expression of scFv13. It is interesting, though, that T3, BL1, and R4 carry the L51 G-D mutation that falls in CDR2 (Loop 5/6) of the VL domain.38 Previously, it was thought that this mutation increased the affinity of scFv13 for antigen,36 but here we uncovered this mutation in an antigen-independent context suggesting that the residue at position L51 also plays a significant role in determining the overall solubility of the scFv. As CDRs primarily dictate affinity, it stands to reason that these regions are not optimized for proper folding, especially in the absence of the stabilizing disulfide bonds.

Figure 7. Structure of scFv13.

The structure of scFv13 heavy chain (right) and light chain (left) is shown with the ribbon structure in gray and the disulfide bonds in green. A hydrogen bond is shown with a dashed green line. The amino acid substitutions in variant T3 are indicated with red side chains.

The area surrounding the putative disulfide bond in the VH domain, between Cys residues at positions H22 and H92, harbors a number of the other mutations uncovered. The most obvious substitution that affects this area is the H6 E-V mutation found in both T3 and BL1. Immunoglobulin VH domain frameworks can be grouped into four distinct types, depending on the main-chain conformation of framework 1 (FR1). H6 is an FR1 core residue that is nearly invariant in Type II immunoglobulin VH domains55 and the sidechain forms four predicted H-bonds including one with the amine of the H92 Cys (see green dashed line in Fig. 7). Since the H6 mutations to scFv13 were isolated in a reducing cell environment, the free thiols of the Cys residues at positions H22 and H92 may render the buried, charged, hydrophilic Glu and the corresponding hydrogen bonding network unfavorable. Thus, mutation of the H6 position to Val may disrupt the hydrogen bonding network in the vicinity of the free thiols in a manner that is more favorable for folding. Interestingly, this residue has been conserved absolutely and is required for the correct folding of class IIA VH domains under normal oxidizing conditions.56; 57

The next observation in the area surrounding the VH disulfide bond regards substitutions occurring to β-strand interfaces in scFv13-T3; particularly the consecutive VH substitutions of H18 L-M and H19 R-I that occur just prior to H22 Cys on the second β-strand in the heavy chain. H18 Leu is a key residue that helps classify Type II domains into subtypes55 and H19 Arg is solvent exposed and within 8Å of H92 Cys. The R-I mutation at H19 is a dramatic substitution that replaces the most hydrophilic side chain with the most hydrophobic and suggests a reorientation or disruption of Strand 2, which may be necessary in the face of reduced Cys residues.

The rest of the substitutions uncovered in our scFv13 variants occur in or immediately surrounding surface loops of the protein. Particularly the H97 and H100 residues both fall in Loop 8/9 in CDR3. It is possible that these two mutations were uncovered due to the fact that both H98 and H99 are predicted to fall outside of the core Phi/Psi region. Particularly, H97 Ile is solvent exposed and extremely hydrophobic. The replacement with hydrophilic Asn might ease some of the tension in this loop region, although the H100 G-S substitution would seem to remove some flexibility. However, if there is a preference for serines and threonines in CDRs, as we found for scFvI9, this could explain the substitution. Regardless, it appears likely that mutations introduced to Loop8/9 have conferred a more favorable conformation. Additionally, L79 Gln occurs immediately prior to Loop 8/9 in the light chain FR3. While this residue is spatially isolated from the other mutated residues, we uncovered this mutation in T3 and also in functional BL1 highlighting its relative importance to scFv13 solubility.

During the selection, an unexpected observation was that antibiotic resistance in the folding assay does not directly correlate with solubility. For example, R4 has a higher level of soluble expression than any of the Tat-evolved variants that we isolated here (Fig. 5a and b). Yet, the antibiotic resistance profile of cells expressing R4 in the POI position lags behind that of any of our Tat-isolated variants (Fig. 4a-c). We suspect that this phenomenon is due to contributions from solubility-independent folding properties such as speed48 and surface hydrophilicity58 that have been shown to play a role in Tat-dependent translocation and may be selected for during laboratory evolution.

Finally, it should be noted that a trade-off between folding and function for scFvs, as well as for many other proteins, is likely to exist especially when selection is performed in an activity-independent context. Thus, it seems that selection for solubility-enhancing mutations might yield target proteins with diminished activity. While this may be acceptable for certain applications, certain others may require a two-tiered selection whereby solubility focusing using the Tat selection is performed initially followed by the application of a functional screen. Along these lines, when we selected scFvs for solubility and then screened for affinity, a functional intrabody was recovered. This suggests that by initially selecting for solubility, a combinatorial library can become focused in ‘soluble sequence space’ prior to functional screening, thus greatly increasing the likelihood of finding a functional intrabody.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

E. coli strain MC4100 was used for all selection experiments, strain DH5α was used for all library constructions, strain BL21(DE3) (Novagen) was used for all protein expression experiments, and strain AMEF 95959 was used for all in vivo activity experiments. For selection, pSALect60 was first modified by adding SfiI sites upstream and downstream from the POI coding region. The initial library was randomized using the doped Mg PCR method61 and cloned between these SfiI sites, while the second and third generation libraries were synthesized using the GeneMorph II Kit (Stratagene) and cloned between the original NdeI and SpeI sites, but still retained the SfiI coding regions. The Tomlinson I library was cloned between NdeI and SpeI with no SfiI coding region. In each round, scFv13 was randomized from the start codon through to the c-myc tag coding region. For expression, the scFv coding regions were amplified from the start codon and appended with the coding region for a C-terminal 6xHis tag and cloned between NcoI and HindIII of pET28a (Novagen). For in vivo experiments, the scFv13 coding regions were cloned between NcoI and NotI in pPM163.38 Variant T3 acquired an L-F mutation at the first leucine in the c-myc tag that hindered Western blotting and was removed with a Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). Plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Unless otherwise noted, antibiotic selection was maintained at: Amp, 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol (Cm), 20 μg/ml, kanamycin (Kan), 50 mg/mL. Growth rate in liquid culture was determined as described previously.47

Spot plating assay

MC4100 cells expressing pSALect with the scFv13 variants in the POI position were cultured overnight in Luria Bertani (LB) broth with Cm, spun down, resuspended in fresh LB with Cm, and serially diluted 10-fold into fresh LB with Cm. 5 μL of each dilution was plated on LB agar plates with appropriate Amp and incubated at 30°C overnight.

Library transformation, selection and counter-screening

Plasmid libraries were transformed into DH5α following construction. Library clones were serially diluted to quantify the library size and 10 randomly chosen clones were sequenced to confirm the diversity of the library prior to selection. The transformed DH5α was cultured overnight in 300 mL LB with Cm and midiprepped the next morning. Library plasmid was then transformed into MC4100, plated in serial dilutions to ensure the diversity of the library and cultured overnight in 200 mL LB with Cm. Cultures were then diluted to the appropriate cell density for selections, as determined by absorbance at 600 nm, and plated on 150 mm diameter plates with the appropriate concentration of Amp. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C and colonies were picked into 200 μL LB with Cm in 96-well plates and recovered overnight at 37°C with shaking. Plates were then diluted by a factor of 104 and 5 μL was spotted onto 150 mm LB plates with Amp at the appropriate concentration. Plasmids were recovered and sequenced from selected clones.

Protein immunoblotting

BL21(DE3) cultures were grown overnight, diluted 1:100 into 15 mL fresh LB with Kan, induced by 100 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside in early exponential phase, normalized by absorbance (600 nm) after 6 hours and lysed via sonication into 500 μL PBS buffer. Western blotting of these soluble lysates was performed with anti-c-myc primary antibody (Zymed) and anti-mouse secondary antibody (Promega).62 5 μL was loaded from three different samples isolated independently on three separate days and developed images were analyzed for densitometry by Scion Image software (Scion, NIH). ELISA was also performed on 2-fold serial dilutions of these lysates with immobilized 10 μg/mL β-gal as antigen, 0.5% BSA as blocking solution, detected using SigmaFAST o-Phenylenediamine (Sigma) tablets, and background was subtracted, determined by incubating wells with no scFv.

In vivo activity screen

After selecting from the initial library, the plates were scraped, miniprepped, a PCR was performed, and the scFv13 coding regions were subcloned into pPM163. This new library was transformed into AMEF 959 cells and plated directly on M9 minimal media supplemented with 20 μM 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-gal). Following overnight incubation, the bluest colonies were selected and streaked on M9 minimal agar with X-gal to confirm phenotype. Plasmids were recovered from successful streaks and sequenced. Plasmids were then re-transformed into AMEF 959 cells, streaked on M9 minimal agar with X-gal plates and photographed. AMEF 959 cultures in the stationary phase were incubated in 96-well plates in the presence of 200 μM X-gal overnight at 30°C and the increase in absorbance at 595 nm was used as a measure of in vivo activity.

Structural analysis

All analysis was performed manually in Swiss PDB View from a hypothetical model of scFv13 kindly provided by Dr. Pierre Martineau.

Acknowledgements

We thank Matthew Nitzberg and Sheela Damle for their technical assistance. We thank Pierre Martineau for his generous gifts of strains and plasmids used in this study. This material is based upon work supported an NSF CAREER Award and a NYSTAR James D. Watson Young Investigator Award (both to M.P.D.).

References

- 1.Holliger P, Hudson PJ. Engineered antibody fragments and the rise of single domains. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1126–36. doi: 10.1038/nbt1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bird RE, Hardman KD, Jacobson JW, Johnson S, Kaufman BM, Lee SM, Lee T, Pope SH, Riordan GS, Whitlow M. Single-chain antigen-binding proteins. Science. 1988;242:423–6. doi: 10.1126/science.3140379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huston JS, Levinson D, Mudgett-Hunter M, Tai MS, Novotny J, Margolies MN, Ridge RJ, Bruccoleri RE, Haber E, Crea R, et al. Protein engineering of antibody binding sites: recovery of specific activity in an anti-digoxin single-chain Fv analogue produced in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:5879–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frisch C, Kolmar H, Schmidt A, Kleemann G, Reinhardt A, Pohl E, Uson I, Schneider TR, Fritz HJ. Contribution of the intramolecular disulfide bridge to the folding stability of REIv, the variable domain of a human immunoglobulin kappa light chain. Fold Des. 1996;1:431–40. doi: 10.1016/s1359-0278(96)00059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kadokura H, Katzen F, Beckwith J. Protein disulfide bond formation in prokaryotes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:111–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koch H, Grafe N, Schiess R, Pluckthun A. Direct selection of antibodies from complex libraries with the protein fragment complementation assay. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:427–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Philibert P, Martineau P. Directed evolution of single-chain Fv for cytoplasmic expression using the beta-galactosidase complementation assay results in proteins highly susceptible to protease degradation and aggregation. Microb Cell Fact. 2004;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prinz WA, Aslund F, Holmgren A, Beckwith J. The role of the thioredoxin and glutaredoxin pathways in reducing protein disulfide bonds in the Escherichia coli cytoplasm. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15661–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biocca S, Ruberti F, Tafani M, Pierandrei-Amaldi P, Cattaneo A. Redox state of single chain Fv fragments targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum, cytosol and mitochondria. Biotechnology (N Y) 1995;13:1110–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt1095-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proba K, Honegger A, Pluckthun A. A natural antibody missing a cysteine in VH: consequences for thermodynamic stability and folding. J Mol Biol. 1997;265:161–72. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Worn A, Auf der Maur A, Escher D, Honegger A, Barberis A, Pluckthun A. Correlation between in vitro stability and in vivo performance of anti-GCN4 intrabodies as cytoplasmic inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2795–803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heng BC, Kemeny DM, Liu H, Cao T. Potential applications of intracellular antibodies (intrabodies) in stem cell therapeutics. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:191–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00348.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller TW, Messer A. Intrabody applications in neurological disorders: progress and future prospects. Mol Ther. 2005;12:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stocks M. Intrabodies as drug discovery tools and therapeutics. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:359–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emadi S, Liu R, Yuan B, Schulz P, McAllister C, Lyubchenko Y, Messer A, Sierks MR. Inhibiting aggregation of alpha-synuclein with human single chain antibody fragments. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2871–8. doi: 10.1021/bi036281f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lecerf JM, Shirley TL, Zhu Q, Kazantsev A, Amersdorfer P, Housman DE, Messer A, Huston JS. Human single-chain Fv intrabodies counteract in situ huntingtin aggregation in cellular models of Huntington's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4764–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071058398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu R, McAllister C, Lyubchenko Y, Sierks MR. Proteolytic antibody light chains alter beta-amyloid aggregation and prevent cytotoxicity. Biochemistry. 2004;43:9999–10007. doi: 10.1021/bi0492354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paganetti P, Calanca V, Galli C, Stefani M, Molinari M. beta-site specific intrabodies to decrease and prevent generation of Alzheimer's Abeta peptide. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:863–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200410047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao T, Heng BC. Intracellular antibodies (intrabodies) versus RNA interference for therapeutic applications. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2005;35:227–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colby DW, Chu Y, Cassady JP, Duennwald M, Zazulak H, Webster JM, Messer A, Lindquist S, Ingram VM, Wittrup KD. Potent inhibition of huntingtin aggregation and cytotoxicity by a disulfide bond-free single-domain intracellular antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17616–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408134101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heng BC, Cao T. Making cell-permeable antibodies (Transbody) through fusion of protein transduction domains (PTD) with single chain variable fragment (scFv) antibodies: potential advantages over antibodies expressed within the intracellular environment (Intrabody) Med Hypotheses. 2005;64:1105–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu Q, Zeng C, Huhalov A, Yao J, Turi TG, Danley D, Hynes T, Cong Y, DiMattia D, Kennedy S, Daumy G, Schaeffer E, Marasco WA, Huston JS. Extended half-life and elevated steady-state level of a single-chain Fv intrabody are critical for specific intracellular retargeting of its antigen, caspase-7. J Immunol Methods. 1999;231:207–22. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gennari F, Mehta S, Wang Y, Clair Tallarico A, Palu G, Marasco WA. Direct phage to intrabody screening (DPIS): demonstration by isolation of cytosolic intrabodies against the TES1 site of Epstein Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) that block NF-kappaB transactivation. J Mol Biol. 2004;335:193–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grim JE, Siegal GP, Alvarez RD, Curiel DT. Intracellular expression of the anti-erbB-2 sFv N29 fails to accomplish efficient target modulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;250:699–703. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benhar I. Biotechnological applications of phage and cell display. Biotechnol Adv. 2001;19:1–33. doi: 10.1016/s0734-9750(00)00054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanes J, Jermutus L, Weber-Bornhauser S, Bosshard HR, Pluckthun A. Ribosome display efficiently selects and evolves high-affinity antibodies in vitro from immune libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14130–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldhaus MJ, Siegel RW, Opresko LK, Coleman JR, Feldhaus JM, Yeung YA, Cochran JR, Heinzelman P, Colby D, Swers J, Graff C, Wiley HS, Wittrup KD. Flow-cytometric isolation of human antibodies from a nonimmune Saccharomyces cerevisiae surface display library. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:163–70. doi: 10.1038/nbt785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daugherty PS, Olsen MJ, Iverson BL, Georgiou G. Development of an optimized expression system for the screening of antibody libraries displayed on the Escherichia coli surface. Protein Eng. 1999;12:613–21. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.7.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritz D, Lim J, Reynolds CM, Poole LB, Beckwith J. Conversion of a peroxiredoxin into a disulfide reductase by a triplet repeat expansion. Science. 2001;294:158–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1063143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jurado P, Ritz D, Beckwith J, de Lorenzo V, Fernandez LA. Production of functional single-chain Fv antibodies in the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 2002;320:1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00405-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levy R, Weiss R, Chen G, Iverson BL, Georgiou G. Production of correctly folded Fab antibody fragment in the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli trxB gor mutants via the coexpression of molecular chaperones. Protein Expr Purif. 2001;23:338–47. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venturi M, Seifert C, Hunte C. High level production of functional antibody Fab fragments in an oxidizing bacterial cytoplasm. J Mol Biol. 2002;315:1–8. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bach H, Mazor Y, Shaky S, Shoham-Lev A, Berdichevsky Y, Gutnick DL, Benhar I. Escherichia coli maltose-binding protein as a molecular chaperone for recombinant intracellular cytoplasmic single-chain antibodies. J Mol Biol. 2001;312:79–93. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaki-Loewenstein S, Zfania R, Hyland S, Wels WS, Benhar I. A universal strategy for stable intracellular antibodies. J Immunol Methods. 2005;303:19–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martineau P, Leclerc C, Hofnung M. Modulating the immunological properties of a linear B-cell epitope by insertion into permissive sites of the MalE protein. Mol Immunol. 1996;33:1345–58. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(96)00091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laden JC, Philibert P, Torreilles F, Pugniere M, Martineau P. Expression and folding of an antibody fragment selected in vivo for high expression levels in Escherichia coli cytoplasm. Res Microbiol. 2002;153:469–74. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(02)01347-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martineau P, Betton JM. In vitro folding and thermodynamic stability of an antibody fragment selected in vivo for high expression levels in Escherichia coli cytoplasm. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:921–9. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martineau P, Jones P, Winter G. Expression of an antibody fragment at high levels in the bacterial cytoplasm. J Mol Biol. 1998;280:117–27. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Auf der Maur A, Escher D, Barberis A. Antigen-independent selection of stable intracellular single-chain antibodies. FEBS Lett. 2001;508:407–12. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Auf der Maur A, Tissot K, Barberis A. Antigen-independent selection of intracellular stable antibody frameworks. Methods. 2004;34:215–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cabantous S, Terwilliger TC, Waldo GS. Protein tagging and detection with engineered self-assembling fragments of green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:102–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maxwell KL, Mittermaier AK, Forman-Kay JD, Davidson AR. A simple in vivo assay for increased protein solubility. Protein Sci. 1999;8:1908–11. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.9.1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waldo GS, Standish BM, Berendzen J, Terwilliger TC. Rapid protein-folding assay using green fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:691–5. doi: 10.1038/10904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wigley WC, Stidham RD, Smith NM, Hunt JF, Thomas PJ. Protein solubility and folding monitored in vivo by structural complementation of a genetic marker protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:131–6. doi: 10.1038/84389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwalbach G, Sibler AP, Choulier L, Deryckere F, Weiss E. Production of fluorescent single-chain antibody fragments in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 2000;18:121–32. doi: 10.1006/prep.1999.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Philibert P, Stoessel A, Wang W, Sibler AP, Bec N, Larroque C, Saven JG, Courtete J, Weiss E, Martineau P. A focused antibody library for selecting scFvs expressed at high levels in the cytoplasm. BMC Biotechnol. 2007;7:81. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-7-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fisher AC, Kim W, DeLisa MP. Genetic selection for protein solubility enabled by the folding quality control feature of the twin-arginine translocation pathway. Protein Sci. 2006;15:449–58. doi: 10.1110/ps.051902606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ribnicky B, Van Blarcom T, Georgiou G. A scFv antibody mutant isolated in a genetic screen for improved export via the twin arginine transporter pathway exhibits faster folding. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:631–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richter S, Lindenstrauss U, Lucke C, Bayliss R, Bruser T. Functional Tat transport of unstructured, small, hydrophilic proteins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33257–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703303200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bogsch EG, Sargent F, Stanley NR, Berks BC, Robinson C, Palmer T. An essential component of a novel bacterial protein export system with homologues in plastids and mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18003–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.You L, Arnold FH. Directed evolution of subtilisin E in Bacillus subtilis to enhance total activity in aqueous dimethylformamide. Protein Eng. 1996;9:77–83. doi: 10.1093/protein/9.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao H, Arnold FH. Combinatorial protein design: strategies for screening protein libraries. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:480–5. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waldo GS. Improving Protein Folding Efficiency by Directed Evolution Using the GFP Folding Reporter. In: Arnold FH, Georgiou G, editors. Directed Enzyme Evolution: Screening and Selection Methods. Vol. 230. Humana Press, Inc.; Totowa, NJ: 2003. pp. 343–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Wildt RM, Mundy CR, Gorick BD, Tomlinson IM. Antibody arrays for high-throughput screening of antibody-antigen interactions. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:989–94. doi: 10.1038/79494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Honegger A, Pluckthun A. The influence of the buried glutamine or glutamate residue in position 6 on the structure of immunoglobulin variable domains. J Mol Biol. 2001;309:687–99. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Haard HJ, Kazemier B, van der Bent A, Oudshoorn P, Boender P, van Gemen B, Arends JW, Hoogenboom HR. Absolute conservation of residue 6 of immunoglobulin heavy chain variable regions of class IIA is required for correct folding. Protein Eng. 1998;11:1267–76. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.12.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jung S, Spinelli S, Schimmele B, Honegger A, Pugliese L, Cambillau C, Pluckthun A. The importance of framework residues H6, H7 and H10 in antibody heavy chains: experimental evidence for a new structural subclassification of antibody V(H) domains. J Mol Biol. 2001;309:701–16. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Richter S, Bruser T. Targeting of unfolded PhoA to the TAT translocon of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42723–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509570200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Melchers F, Messer W. The activation of mutant beta-galactosidase by specific antibodies. Purification of eleven antibody activatable mutant proteins and their subunits on sepharose immunosorbents. Determination of the molecular weights by sedimentation analysis and acrylamide gel electrophoresis. Eur J Biochem. 1970;17:267–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb01163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lutz S, Fast W, Benkovic SJ. A universal, vector-based system for nucleic acid reading-frame selection. Protein Eng. 2002;15:1025–30. doi: 10.1093/protein/15.12.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fromant M, Blanquet S, Plateau P. Direct random mutagenesis of gene-sized DNA fragments using polymerase chain reaction. Anal Biochem. 1995;224:347–53. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DeLisa MP, Tullman D, Georgiou G. Folding quality control in the export of proteins by the bacterial twin-arginine translocation pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6115–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937838100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]