Abstract

Immediate early viral protein IE1 is a potent transcriptional activator encoded by baculoviruses. Although the requirement of IE1 for multiplication of Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) is well established, the functional roles of IE1 during infection are unclear. Here, we used RNA interference to ablate IE1, plus its splice variant IE0, and thereby define in vivo activities of these early proteins, including gene-specific regulation and induction of host cell apoptosis. Confirming an essential replicative role, simultaneous ablation of IE1 and IE0 by gene-specific double-stranded RNAs inhibited AcMNPV late gene expression, reduced yields of budded virus by more than 1,000-fold, and blocked production of occluded virus particles. Depletion of IE1 and IE0 had no effect on early expression of the envelope fusion protein gene gp64 but abolished early expression of the caspase inhibitor gene p35, which is required for prevention of virus-induced apoptosis. Thus, IE1 is a positive, gene-specific transactivator. Whereas an AcMNPV p35 deletion mutant caused widespread apoptosis in permissive Spodoptera frugiperda cells, ablation of IE1 and IE0 prevented this apoptosis. Silencing of ie-1 also prevented AcMNPV-induced apoptosis in nonpermissive Drosophila melanogaster cells. Thus, de novo synthesis of IE1 is required for virus-induced apoptosis. We concluded that IE1 causes apoptosis directly or contributes indirectly by promoting virus replication events that subsequently trigger cell death. This study reveals that IE1 is a gene-selective transcriptional activator which is required not only for expedition of virus multiplication but also for blocking of its own proapoptotic activity by upregulation of baculovirus apoptotic suppressors.

The baculoviruses are prolific insect pathogens that have been engineered as highly productive gene expression vectors. Multiplicative success of these large DNA viruses depends on coordinated and regulated expression of viral genes, as well as the inhibition of host defense mechanisms that include apoptosis (reviewed in references 6, 12, 39, and 43). Immediate early protein IE1 is thought to be a critical mediator of baculovirus gene expression due to its potency as a transcriptional activator. Although IE1 is required for multiplication of Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV), the prototype species of Baculoviridae, the exact replicative functions of this highly conserved protein are poorly understood (57). It is unclear, for example, whether IE1 regulates transcription of every gene within the 128-kb double-stranded AcMNPV genome and whether it contributes to the widespread apoptosis that is associated with AcMNPV infection (7, 23, 46). Defining the replicative functions of IE1 during the course of a normal infection is critical for an understanding of the multiplicative competency of AcMNPV and thus its efficiency as a viral expression vector (reviewed in reference 20).

AcMNPV IE1 is a 67-kDa dimeric DNA-binding protein that stimulates transcription in plasmid transfection assays through the activity of its N-terminal acidic domains (3, 5, 9, 13, 14, 21, 22, 29, 38, 41, 42, 44, 50, 51, 55). Synthesized very early during infection, IE1 accumulates within the nucleus, where it is maintained through late times (4, 40, 47, 57). Transactivation by IE1 is enhanced by its binding as a homodimer to the baculovirus homologous region (hr) sequences, which function as transcriptional enhancers and origins of viral DNA replication (5, 22, 28, 42, 45, 50). The capacities of IE1 to interact with origins of viral DNA replication and to associate with DNA replication factories are consistent with the postulated role of IE1 in baculovirus DNA replication (5, 19, 28, 36, 50). Thus, IE1 appears to have multiple in vivo functions, as originally suggested by the variety of behaviors displayed by a temperature-sensitive mutant of IE1 (49).

AcMNPV immediate early protein IE0 (74 kDa) is identical to IE1 except for an additional 54 amino acid residues at its N terminus. Also synthesized early, IE0 is produced from an RNA splicing event in which a single exon (exon0) is fused to the 5′ end of the ie-1 open reading frame (ORF) (4, 47, 56). Presumably due to their common sequences, IE0 and IE1 share biochemical activities, including hr enhancer binding and transcriptional activation (9, 21, 22). Nonetheless, either IE1 or IE0 is sufficient for AcMNPV multiplication; the presence of both genes is not required (30, 56). Thus, the potential regulatory role of IE0 during infection is an interesting unknown.

Importantly, IE1 has been implicated in triggering apoptosis during infection (23, 46). Apoptosis induced by AcMNPV mutants lacking apoptotic inhibitors causes vigorous and widespread cell death that can severely limit virus multiplication (reviewed in references 6 and 12). Nonetheless, the mechanisms by which baculoviruses trigger apoptosis and the viral genes required for this dramatic pathogenesis are unknown. IE1 may contribute directly by transactivation of host prodeath genes, by induction of a host DNA damage response, or by alteration of the cell cycle. Indeed, ectopic overexpression of ie-1 causes low-level apoptosis in cultured cells through an unknown mechanism (46). Alternatively, IE1 may contribute indirectly by promoting virus replicative events, including viral DNA synthesis or inhibition of host biosynthetic processes, which can trigger host cell suicide (7, 23). Here, we have defined the role of IE1 in AcMNPV-induced apoptosis by using RNA interference (RNAi) to ablate IE1 during infection.

RNAi is an invaluable tool for defining functions of virus and host genes in lepidopteran and dipteran cells (18, 25, 34, 48, 54, 58). The success of RNAi-mediated inhibition of virus gene expression is due in part to the efficiency with which in vitro-synthesized double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) enters cultured insect cells and subsequently engages the host's RNA silencing machinery (reviewed in reference 33). Moreover, RNAi provides a distinct advantage in that gene function can be evaluated during virus infection initiated by normal host cell receptor-mediated entry. Here, we report that RNAi effectively silenced ie-1 and ie-0 during AcMNPV inoculation of permissive lepidopteran and nonpermissive dipteran cells. Confirming critical roles in replication (56, 58), RNAi ablation of IE1 and IE0 severely inhibited multiple facets of AcMNPV multiplication. Surprisingly, loss of IE1 had dissimilar effects on expression of early viral genes, demonstrating that IE1 is a transcriptional regulator that differentially regulates viral promoters. Importantly, loss of IE1 prevented AcMNPV-induced apoptosis in lepidopteran and dipteran cells. Thus, our study suggests that IE1 triggers this antiviral response through a mechanism that is conserved between insects from different orders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Spodoptera frugiperda IPLB-SF21 (SF21) cells (60) were propagated in TC100 growth medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone Laboratories). Drosophila melanogaster Schneider DL-1 cells (52) were propagated in Schneider's growth medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 15% heat-inactivated FBS. Described previously (32), SF21Op-iap cells were derived from parental SF21 cells by stable transfection with the inhibitor-of-apoptosis gene Op-iap from Orygia pseudotsugata MNPV; the AcMNPV ie-1 promoter directs constitutive expression of influenza hemaglutinin epitope-tagged Op-iap (Op-iapHA).

Viruses.

All viruses were plaque purified, and their genotypes (Fig. 1) were confirmed by analyses of PCR-amplified genomic segments. Wild-type (wt) AcMNPV strain L-1 (27) and AcMNPV recombinants wt/lacZ (p35+, polyhedrin gene [polh] negative, lacZ+), vIE1FL-FCAT (p35+, cat+, polh+), v35K-CAT (p35+, cat+, polh+), vΔ35K/lacZ (p35 negative, polh negative, lacZ+), and vOpIAP (p35 negative, Op-iap+, lacZ+) were described previously (16, 25, 47, 62). Recombinant vIE1prm-EGFP/lacZ (p35+, egfp+, lacZ+) was created by allelic replacement in which the polh of parent wt AcMNPV was replaced with the lacZ gene fused to the polh promoter, which was linked to the enhanced green fluorescence protein gene (egfp) and fused to the ie-1 promoter (prm). vIE1prm-EGFP (p35+, egfp+, polh+) was generated by replacing lacZ of parent vIE1prm-EGFP/lacZ with polh. The ie-1 promoter (IE1prm), extending from positions −531 to +138 relative to the ie-1 transcriptional start site (+1), directs expression of egfp, AcMNPV p35, and Op-iapHA, each of which was inserted at the polh locus of recombinant vIE1prm-EGFP, vIE1prm-EGFP/lacZ, vP35, and vOpIAP, respectively (Fig. 1). vP35prm-EGFP (p35+, egfp+, polh+) was created by replacing lacZ of parent wt/lacZ with polh, which was linked to egfp fused to the p35 promoter extending from positions −226 to +55 relative to the p35 transcriptional start site (+1).

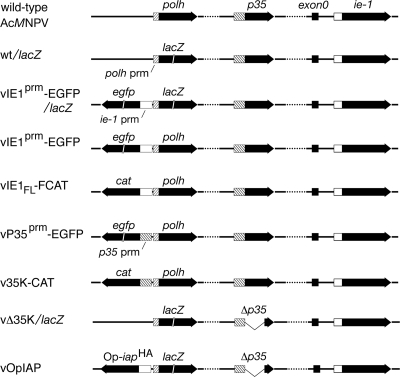

FIG. 1.

Gene organization of AcMNPV recombinants. The genes encoding polyhedrin (polh), P35 (p35), IE1 (ie-1), and the first exon (exon0) of the ie-0 gene are indicated on the linear representation of the wt AcMNPV genome; black arrows denote protein-coding regions. In recombinant lacZ-carrying viruses, the polh gene was replaced with a lacZ reporter gene under the control of the polh promoter (prm; cross-hatched box). The enhanced green fluorescence protein gene (egfp) and CAT gene (cat) were fused to the ie-1 promoter (open box) or the p35 promoter (cross-hatched box) and inserted at the polh locus. Recombinants vΔ35K/lacZ and vOpIAP lack p35. The inhibitor-of-apoptosis gene Op-iapHA fused to the ie-1 promoter was inserted adjacent to lacZ at the polh locus of vOpIAP.

For inoculations, 10 PFU per cell (unless stated otherwise) of extracellular budded virus (BV) in TC100-10% FBS was added to SF21 or DL-1 monolayers. After being subjected to gentle rocking for 1 h at room temperature, the inoculum was replaced with FBS-supplemented medium, and the cells were incubated at 27°C. Phase-contrast photography was conducted by using an Axiovert 135TV microscope (Zeiss) equipped with a Microfire camera (Optronics). Enhanced green fluorescent protein fluorescence was photographed by using the X-Cite 120 fluorescence illumination system attached to the same microscope. Images were generated with Pictureframe software (Optronics) and Adobe Photoshop.

dsRNA transfection.

The complete egfp ORF (25), nucleotides 855 to 2390 of AcMNPV gp64 (GenBank accession number M25420), nucleotides 63 to 173 of AcMNPV exon0 (GenBank accession number M22231), and nucleotides 439 to 2409 of AcMNPV ie-1 (GenBank accession number M21884) were inserted into plasmid pBluescript K/S(+) (Invitrogen). RNA was synthesized by using in vitro transcription reactions (Ampliscribe T3 and T7 kits; Epicentre) with these template plasmids. dsRNA was generated from complementary single-stranded RNAs that were heated to 65°C and cooled 1°C per min. For transfection of SF21 cells, dsRNA (80 μg) was incubated for 2 h with cationic liposomes (40 μl) consisting of DOTAP-DOPE {N-[1-(2,3-dioleoyloxy)propyl]-N,N,N-trimethylammonium methylsulfate)-l-phosphatidylethanolamine, dioeoyl (C18:1,[cis]-9)}. The RNAs were diluted with serum-free TC100 to give a final volume of 1 ml and mixed with 2 × 106 SF21 cells. The RNA-cell suspension was gently agitated for 4 h at 27°C and transferred to 60-mm-diameter plates. After cell attachment, the overlay was replaced with TC100-10% FBS. For DL-1 transfections, conditions were identical except that dsRNA (20 μg) was incubated with DOTAP-DOPE (20 μl) and the transfected cells were overlaid with Schneider's medium-15% FBS in 35-mm-diameter plates.

Immunoblots and antisera.

Intact cells and apoptotic bodies, if present, were collected by centrifugation, lysed in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-1% β-mercaptoethanol, and subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Osmonics, Inc.) and incubated with the following antisera (diluted as indicated in parentheses): polyclonal anti-IE1 (1:10,000) (41), monoclonal AcV5 anti-GP64 (a gift from Gary Blissard) (1:500) (17), monoclonal anti-P35 (1:1,000) (a gift from Yuri Lazebnik), monoclonal antiactin (1:5,000 dilution) (BD Biosciences), polyclonal anti-Spodoptera frugiperda caspase-1 (anti-Sf-caspase-1) (1:1,000) (24), or polyclonal anti-DrICE (1:1,000) (25). Signal development was performed with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (anti-IE1 or anti-DrICE) or goat anti-mouse (anti-GP64, anti-P35, or antiactin) immunoglobulin G (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) and the CDP-Star chemiluminescence detection system (Roche). Films were scanned at 300 dots per inch by using an Epson Twain Pro scanner and prepared by using Adobe Photoshop CS2 and Adobe Illustrator CS2.

β-Galactosidase and CAT assays.

SF21 cell monolayers transfected 24 h previously with dsRNA were infected with AcMNPV recombinant vIE1prm-EGFP/lacZ (multiplicity of infection [MOI], 10). Cells were collected 48 h later, washed, and lysed by suspension in Tropix lysis buffer (Galacto-Light Plus kit; Applied Biosystems). β-Galactosidase activity was measured by using a Monolight 3010 luminometer per the manufacturer's instructions and is reported as the average activity ± standard deviation determined from triplicate infections. To measure chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) activity, SF21 monolayers were infected (MOI, 10) with recombinant vIE1FL-FCAT or v35K-CAT, collected at the indicated times, and lysed in 0.25 M Tris (pH 7.8)-0.5% Triton X-100. CAT activity was measured by phase extraction (53), for which samples of clarified lysate were incubated at 37°C for 25 min in a 90-μl reaction mix containing 4.4 nCi/μl [3H]chloramphenicol (43.4 Ci/mmol; Perkin Elmer Inc.) and 0.25 μg/μl n-butyryl coenzyme A (Promega). The desired reaction product, butyrylated [3H]chloramphenicol, was extracted with one volume of xylene. After three extractions with one volume of 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0)-1 mM EDTA to remove residual substrate, the butyrylated [3H]chloramphenicol was quantified by liquid scintillation counting. Intracellular CAT activity is reported as averages ± standard deviations determined from duplicate assays and triplicate infections.

Caspase assays.

Mock- or virus-infected cells were collected and lysed in caspase activity buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 2 mM EDTA, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1% CHAPS {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate}) containing 1× protease inhibitor (Roche). The lysates were clarified by centrifugation, and caspase activity was measured by using the substrate DEVD-amc (N-acetyl-DEVD-7-amido-4-methylcoumarin) (Sigma) as previously described (24). Values are reported as the average rates of fluorescent product accumulation (relative light units) ± standard deviations for cells harvested 24 h after infection from three independent plates.

RESULTS

IE1 and IE0 are depleted by gene-specific RNAi.

To evaluate the effect of IE1 and IE0 on AcMNPV replication, we used an RNAi approach to selectively silence gene expression. To this end, we generated gene-specific dsRNAs which, when transfected into cultured cells, would target virus-transcribed ie-1 and ie-0 mRNAs (ie-1/ie-0 mRNAs). Transcription of the ie-1/ie-0 locus of AcMNPV yields spliced ie-0 and unspliced ie-1 mRNAs that overlap significantly at their 3′ ends (Fig. 2A). Only the 5′ end of the ie-0 mRNA, which includes a portion of the ac141 gene for the late protein EXON0, is unique. We therefore generated a small dsRNA complementary to the first exon of ie-0 (exon0 dsRNA) and a separate dsRNA complementary to both ie-1 and ie-0 (designated ie-1/ie-0 dsRNA) for use in our RNAi strategy (Fig. 2A). Because of the overlapping nature of these dsRNAs, we expected exon0 dsRNA to interfere with ie-0 and ac141 expression, whereas ie-1/ie-0 dsRNA would interfere with ie-0 and ie-1 expression. No other genes are known to overlap the ie-1 ORF.

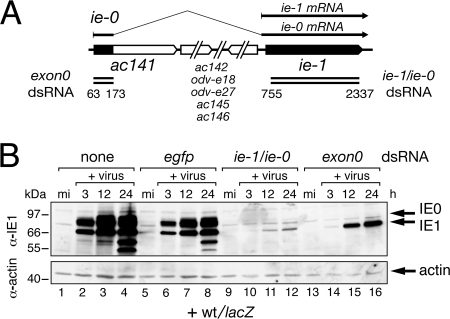

FIG. 2.

RNAi depletion of IE1 and IE0. (A) Organization of the AcMNPV ie-0/ie-1 locus. The ie-1 mRNA, which encodes IE1 (582 residues), is initiated immediately upstream from the ie-1 ORF (black arrow). The ie-0 mRNA, which encodes IE0 (636 residues), begins upstream of the ac141 (exon0) gene and is spliced to remove an intron encompassing at least six genes (white arrows). The N terminus of IE0 contains 38 residues from the ac141 protein, 16 residues encoded by sequences immediately upstream of the ie-1 ORF, and all ie-1 ORF residues (4, 8). The exon0 and ie-1/ie-0 dsRNAs (double bars) used here extend from nucleotides 63 to 173 and 755 to 2337 relative to the ie-0 and ie-1 RNA start sites (+1), respectively. (B) Immunoblots. SF21Op-iap cells were transfected without dsRNA (none) or with egfp, ie-1/ie-0, or exon0 dsRNA and infected 24 h later with AcMNPV recombinant wt/lacZ. Total cell lysates prepared at the indicated hours (h) after mock infection (mi) or infection (+virus) were subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-IE1 (top) or antiactin (bottom). The actin blot indicated comparable levels of protein loaded. Protein size standards (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left. α, anti.

We first tested the effect of in vitro-generated dsRNAs on viability of SF21 cells. Upon transfection, ie-1/ie-0 dsRNA, a dsRNA specific to the AcMNPV envelope fusion protein GP64 gene (gp64 dsRNA), and dsRNAs specific for genes encoding enhanced green fluorescence protein (egfp dsRNA), luciferase, or CAT had no effect on cell viability or morphology (data not shown). However, transfection with exon0 dsRNA caused a small fraction (<20%) of the cells to fragment and undergo membrane blebbing that was reminiscent of apoptosis. Treatment of exon0 dsRNA-transfected cells with a cell-permeable caspase inhibitor blocked the morphological signs of apoptosis (data not shown). Thus, to avoid potential toxic effects of dsRNAs, we subsequently used the SF21Op-iap cell line, an SF21-derived clonal line that stably expresses the apoptotic inhibitor Op-iap (32). SF21Op-iap cells showed no deleterious effects when transfected with any of the dsRNAs used here, including exon0 dsRNA (see below). Furthermore, this cloned cell line was indistinguishable from parental SF21 cells with respect to multiple criteria, including AcMNPV gene expression and multiplication.

To assess the capacity of dsRNA to silence ie-1 and ie-0, we first monitored steady-state levels of IE1 and IE0 during AcMNPV infection. To this end, SF21Op-iap cells were transfected with dsRNA and infected 24 h later with wt/lacZ, an AcMNPV recombinant in which a polh promoter-driven lacZ reporter replaced the polh gene (Fig. 1). Immunoblot analysis indicated that control egfp dsRNA had no effect on the timing of IE1 and IE0 synthesis (Fig. 2B) and caused only minor reductions in the steady-state levels of both proteins. In contrast, ie-1/ie-0 dsRNA eliminated IE0 and caused a dramatic reduction in IE1 (lanes 9 to 12); only trace levels of IE1 were detected at 12 and 24 h after infection. IE0 was fully depleted by exon0 dsRNA (lanes 14 to 16) and IE1 levels were reduced, especially early in infection. We concluded that RNAi is effective for knockdown of ie-0 and ie-1. Importantly, it was determined that uptake of dsRNA did not affect virus entry, because production of other early viral proteins was normal (see below).

RNAi-mediated depletion of IE1 and IE0 inhibits viral multiplication.

As demonstrated by gene deletion, IE1 is required for AcMNPV multiplication (56). Thus, to quantify the effectiveness of ie-1/ie-0 silencing, we monitored aspects of AcMNPV multiplication in dsRNA-transfected SF21Op-iap cells. Upon transfection with control egfp dsRNA, production of polyhedra by vIE1prm-EGFP (Fig. 1) was indistinguishable from that of untreated cells (Fig. 3A). Quantitation with stained gels indicated that intracellular levels of polyhedrin in these cells were reduced only slightly compared to those of untreated cells (Fig. 3B). In contrast, ie-1/ie-0 dsRNA-transfected cells produced no detectable polyhedra (Fig. 3A) or polyhedrin (Fig. 3B) after infection. exon0 dsRNA caused only minor reductions in accumulation of polyhedrin and polyhedra. To better quantify the effects of silencing on very late viral gene expression, we measured polh promoter activity of AcMNPV recombinant vIE1prm-EGFP/lacZ (Fig. 1). exon0 dsRNA decreased polh promoter activity by only threefold in comparison to the level for untreated cells (Fig. 3C). Conversely, ie-1/ie-0 dsRNA reduced promoter activity to background levels. These data confirmed that ie-1 is required for very late gene (polh) expression and that ie-0 is dispensable for this function. It is noteworthy that late gene expression was reduced fivefold by control egfp dsRNA, suggesting that dsRNA has a modest repressive effect on AcMNPV replication (see below).

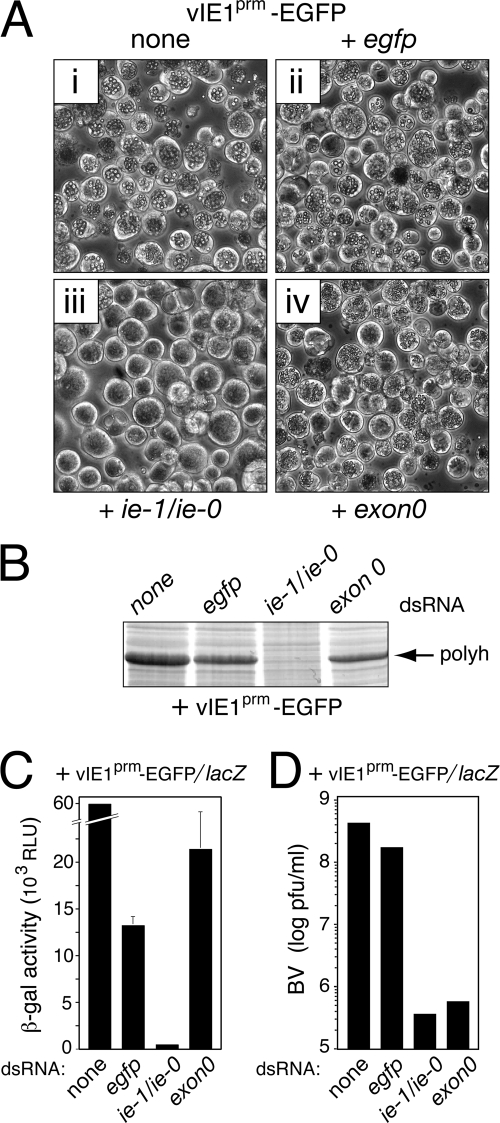

FIG. 3.

Effect of ie-1/ie-0 silencing on virus production. (A) Polyhedra. SF21Op-iap cells were transfected without dsRNA (none) or with (+) the indicated dsRNAs and infected 24 h later with polh+ virus vIE1prm-EGFP. Photographs (500× magnification) were taken 48 h after infection. (B) Intracellular polyhedrin. Total lysates from the cells described for panel A were electrophoresed and stained with Coomassie blue. Polyhedrin (polyh) is indicated. (C) polh promoter activity. SF21Op-iap cells were transfected with the indicated dsRNAs and infected with vIE1prm-EGFP/lacZ (MOI, 10) in which the polh promoter directs lacZ expression. Promoter activity was quantified by measuring β-galactosidase in cell extracts prepared 48 h after infection. Values reported are the average relative light units (RLU) ± standard deviations determined from triplicate infections. Results from a representative experiment are shown. (D) BV yields. Extracellular BV produced by triplicate plates of dsRNA-treated SF21Op-iap cells infected with virus vIE1prm-EGFP/lacZ (MOI, 40) was quantified 48 h after infection by 50% tissue culture infective doses. Results from a representative experiment are shown.

RNAi-mediated silencing also reduced yields of infectious extracellular BV. When transfected with ie-1/ie-0 dsRNA, vIE1prm-EGFP/lacZ-infected SF21Op-iap cells produced ∼1,000-fold less BV than untreated cells (Fig. 3D). Likewise, exon0 dsRNA caused a comparable reduction in BV yield. However, because protein EXON0 is required for efficient BV production (8, 11), we attributed the negative effect of exon0 dsRNA to silencing of ac141, the essential gene that encodes EXON0 (Fig. 2). Collectively, these studies confirmed the essential nature of the ie-1/ie-0 locus in AcMNPV multiplication and that RNA silencing is an effective means to interfere with the function of these immediate early genes.

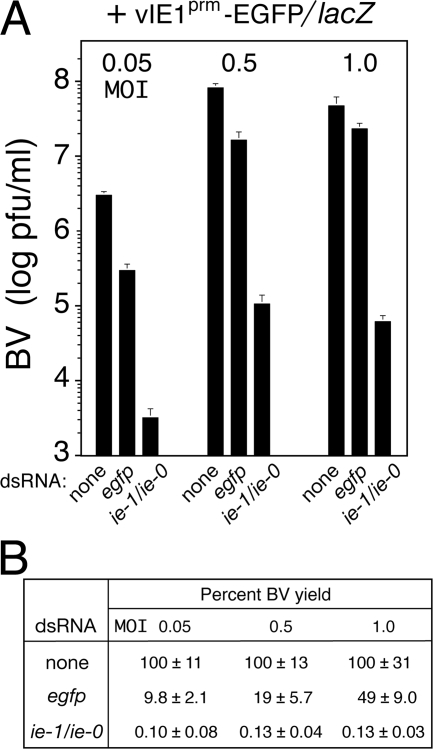

RNAi-mediated silencing of ie-1 is independent of MOI.

In initial experiments, we observed that heterologous dsRNAs had a nonspecific, negative effect on AcMNPV replicative events that was influenced by the MOI of the infecting virus. Thus, to determine if ie-1/ie-0 silencing was also influenced by MOI and thus affected by potential artifacts of RNA transfection, we tested the impact of RNAi on BV production as a function of MOI. To this end, dsRNA-transfected SF21 cells were inoculated with increasing MOIs of vIE1prm-EGFP/lacZ and 48-h yields of BV were measured (Fig. 4A). egfp dsRNA caused a 10-fold reduction in BV at the lowest MOI (0.05 PFU per cell) but only twofold at the highest MOI (1 PFU per cell) (Fig. 4B). Unrelated heterologous dsRNAs caused comparable MOI-dependent reductions in BV production (data not shown), suggesting that this negative effect was nonspecific. In contrast, ie-1/ie-0 dsRNA reduced BV yields by ∼1,000-fold at each MOI (Fig. 4B). Thus, ie-1/ie-0 silencing was independent of MOI. This finding confirmed the effectiveness of RNAi for defining the roles of IE1 and IE0 during infection and ruled out possible artifacts due to dsRNA transfection. The mechanism by which heterologous dsRNA negatively affects AcMNPV multiplication is unclear, but it involves an early step, because accumulation of early virus proteins was also reduced (see below). Such effects should be considered when using RNAi to define baculovirus gene function.

FIG. 4.

Effect of MOI on RNAi effectiveness. SF21Op-iap cells were transfected without dsRNA (none) or with egfp or ie-1/ie-0 dsRNA and inoculated 24 h later with vIE1prm-EGFP/lacZ using the indicated MOI (PFU per cell). Extracellular BV was quantified 48 h after infection by 50% tissue culture infective doses. Reported values are the average virus yields (PFU per ml) ± standard deviations determined from triplicate infections (A) and were normalized to those obtained in the absence of dsRNA (B).

IE1 and IE0 regulate early protein synthesis during infection.

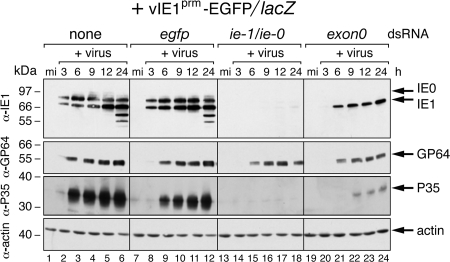

Due to their transcriptional stimulatory activity, it is likely that IE1 and IE0 regulate transcription of AcMNPV genes. However, to date, the contributions of both transactivators have not been evaluated in the context of an infection initiated by receptor-mediated entry of normal virus. Here, RNAi-mediated ablation of IE1 and IE0 enabled us to define functions of these transactivators in the infected cell. We first monitored the effects of IE1 and IE0 on synthesis of early AcMNPV proteins during infection of SF21Op-iap cells with vIE1prm-EGFP/lacZ. As expected, ie-1/ie-0 dsRNA reduced the amounts of IE1 and IE0 below the level of immunoblot detection (Fig. 5, lanes 14 to 18) and exon0 dsRNA fully depleted IE0 (lanes 20 to 24). In contrast, ie-1/ie-0 or exon0 dsRNA had a minimal effect on synthesis of envelope fusion protein GP64, which accumulated with the same kinetics as that in untreated (lanes 2 to 6) or egfp dsRNA-treated (lanes 8 to 12) cells. Thus, IE1 and IE0 had little effect on expression of gp64. This finding also indicated that dsRNA did not interfere with virus entry or genome uncoating. In contrast, levels of protein P35 were decreased below the level of detection in ie-1/ie-0-silenced cells (lanes 14 to 18) and were significantly reduced in exon0-silenced cells (lanes 20 to 24). Thus, these data suggested that expression of p35, unlike that of gp64, requires IE1 and is positively influenced by IE0 during infection. We concluded that early gene expression, typified by that of p35 and gp64, exhibit surprisingly dissimilar regulations by IE1 and/or IE0.

FIG. 5.

Effect of RNAi on AcMNPV early proteins GP64 and P35. SF21Op-iap cells were transfected without dsRNA (none) or with egfp, ie-1/ie-0, or exon0 dsRNA and inoculated with vIE1prm-EGFP/lacZ. Total cell lysates prepared at the indicated hours (h) after mock infection (mi) or infection (+virus) were subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-IE1 (first row), anti-GP64 (second row), anti-P35 (third row), or antiactin (fourth row). Actin levels indicated comparable loading of cell lysates. Protein size standards (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left. Caspase-mediated cleavage of P35 was prevented by the cellular Op-IAP. α, anti.

IE1 and IE0 regulate early gene expression during infection.

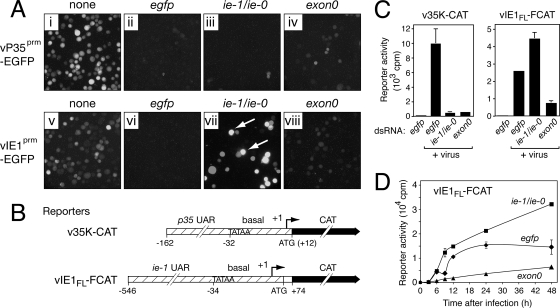

To quantify effects of IE1 and IE0 on promoter activity in vivo, we generated AcMNPV recombinants with reporter genes under the control of viral early promoters. Recombinant vP35prm-EGFP (Fig. 1) carries egfp fused to the full-length p35 promoter, which exhibits wt activity when inserted at the polh locus (10, 38). Fluorescence microscopy was used to monitor promoter activity within individual living cells. In the absence of dsRNA, the p35 promoter produced a strong fluorescent signal in >90% of the cells by 48 h after infection (Fig. 6A, panel i). As expected, this signal was lost upon egfp silencing (panel ii). Silencing of ie-1/ie-0 caused a comparable loss of signal (panel iii). In contrast, a low level of egfp fluorescence was detected in exon0-silenced cells (panel iv). In each case, normal intracellular accumulation of GP64 demonstrated that these cells were infected (data not shown). We quantified p35 promoter activity by measuring CAT activity in cells infected with AcMNPV recombinant v35K-CAT (Fig. 1), in which the full-length p35 promoter directs cat reporter expression (Fig. 6B). By 24 h after infection, p35 promoter activity was reduced 16- to 20-fold upon ie-1/ie-0 or exon0 dsRNA silencing in comparison to the level for egfp-silenced cells (Fig. 6C). We concluded that IE1 is required for p35 promoter activation and that IE0 contributes directly or indirectly.

FIG. 6.

Effects of RNAi on AcMNPV early promoter activity. (A) Live-cell fluorescence images. SF21Op-iap cells were transfected with the indicated dsRNAs, infected with either vP35prm-EGFP (panels i to iv) or vIE1prm-EGFP (panels v to viii), and photographed 48 h later by using fluorescence microscopy (250× magnification). Arrows denote intense fluorescence of specific vIE1prm-EGFP-infected cells. (B) CAT reporter genes. The p35 and ie-1 promoters, consisting of the indicated nucleotides of the upstream activating region (UAR) and the TATA box-containing basal promoter, were fused to the cat reporter (CAT) and inserted at the polh locus of AcMNPV recombinants v35K-CAT and vIE1FL-FCAT, respectively (Fig. 1). The RNA start sites (+1) and initiating codons (ATG) are indicated. (C) Promoter activities. SF21Op-iap cells transfected with the indicated dsRNAs were infected with v35K-CAT or vIE1FL-FCAT. Intracellular CAT activity was measured 24 h after infection. Values reported are the butyrylated [3H]chloramphenicol counts per min (cpm; averages ± standard deviations) for triplicate infections. Results from representative experiments are shown. (D) Time course of ie-1 promoter activity. CAT activity within dsRNA-transfected SF21Op-iap cells was measured at the indicated times (h) after infection with vIE1FL-FCAT and reported as described for panel C.

Previous studies have suggested that IE1 and IE0 can regulate their own expression. For example, when overproduced in transfection assays, IE0 stimulates the ie-1 promoter but not its own promoter, whereas IE1 stimulates its own promoter and represses the ie-0 promoter (21, 47). To investigate autoregulation by IE1 and IE0 in vivo, we first monitored activity of the ie-1 promoter by using AcMNPV recombinant vIE1prm-EGFP. The full-length ie-1 promoter, which directs egfp expression, behaves in a manner identical to that of the native ie-1 gene promoter (47) and was not overlapped by the dsRNAs used here. In the absence of dsRNA, ie-1 promoter-directed fluorescence was detected in >90% of the cells by 48 h after infection (Fig. 6A, panel v). Upon ie-1/ie-0 silencing, egfp fluorescence disappeared from a majority (>80%) of the cells. Thus, in most cells, IE1, IE0, or both are required for normal ie-1 transcription. Interestingly, fluorescence intensified in cells representing a minority (5 to 17%) of the ie-1/ie-0-silenced population (Fig. 6A, panel vii). This unique pattern, which suggested hyperactivity of the ie-1 promoter, was highly reproducible and not due to inefficient silencing, because the same ie-1/ie-0 dsRNA preparation eliminated p35 promoter-directed fluorescence (Fig. 6A, panel iii). Moreover, upon exon0 silencing, ie-1 promoter-directed fluorescence was dramatically reduced and more uniformly distributed (Fig. 6A, panel viii). We concluded that IE0 stimulates ie-1 transcription and that IE1 and IE0 cooperatively regulate ie-1, except in a minority of cells wherein the ie-1 promoter is subject to alternative controls (see below).

To better quantify ie-1 promoter activity, we used the CAT reporter of recombinant vIE1FL-FCAT (Fig. 1), in which the same full-length ie-1 promoter directs cat expression (Fig. 6B). By 24 h after infection, ie-1 promoter activity in exon0-silenced cells was reduced threefold in comparison to that in egfp-silenced cells (Fig. 6C). In contrast, ie-1 promoter activity was enhanced twofold in ie-1/ie-0-silenced cells; we attributed this increase to the hyperactivity of the ie-1 promoter in select cells. These trends were confirmed by monitoring ie-1 promoter activity throughout infection (Fig. 6D). At both early and late times, ie-1 promoter activity was highest in ie-1/ie-0-silenced cells and lowest in exon0-silenced cells. Because ie-1 promoter activity was reduced in the absence of IE0, our findings suggested that IE0 is a positive regulator of ie-1 expression in vivo. Furthermore, because ablation of both IE1 and IE0 reduced ie-1 promoter activity in most (>80%) cells, we concluded that both IE1 and IE0 positively regulate ie-1 expression. Nonetheless, in an interesting subpopulation of ie-1/ie-0-silenced cells in which the ie-1 promoter is hyperactive, other transcriptional regulatory mechanisms are dominant (see below).

IE1 is required for AcMNPV-induced apoptosis in permissive cells.

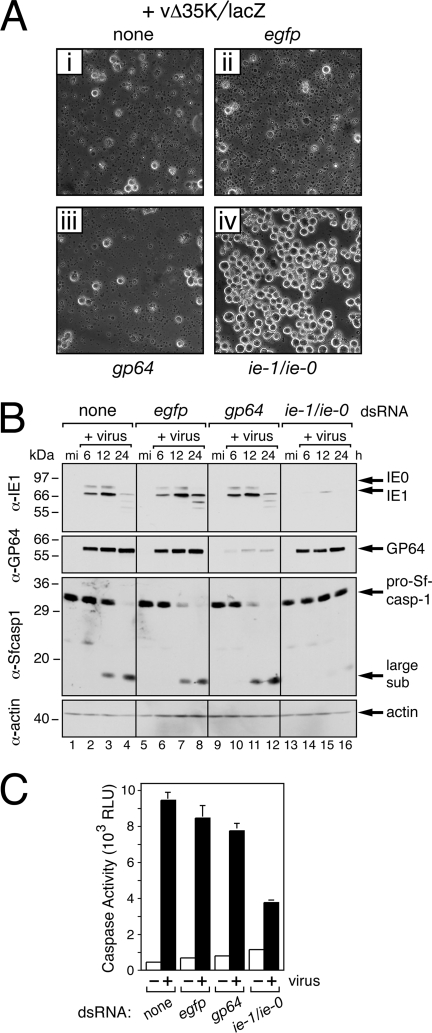

Previous studies have implicated IE1, either directly or indirectly, in triggering apoptosis during AcMNPV infection (23, 46). By silencing ie-1 and ie-0 in normal unmodified SF21 cells, we evaluated the apoptotic role of IE1 and IE0 during infection. Transfection of control egfp dsRNA or AcMNPV gp64 dsRNA had no effect on the capacity of the AcMNPV p35-null mutant vΔ35K/lacZ (Fig. 1) to trigger widespread apoptosis in normal SF21 cells (Fig. 7A, panels ii and iii). By 24 h after infection, apoptotic blebbing and cytolysis encompassed >90% of the culture, a result which was comparable to results in the absence of dsRNA (Fig. 7A, panel i). In the absence of caspase inhibitor P35, apoptosis induced by vΔ35K/lacZ was not prevented, because the host death proteases known as caspases function unabated to proteolytically execute the infected cell. The principal Spodoptera effector caspase, Sf-caspase-1, is processed from an inactive proform (pro-Sf-caspase-1) to its active large/small subunit complex during apoptosis (24). Indeed, Sf-caspase-1 was processed to its subunit form in vΔ35K/lacZ-infected cells treated with egfp or gp64 dsRNA (Fig. 7B, lanes 6 to 8 and 10 to 12) at a rate comparable to that in untreated cells (lanes 2 to 4). As measured by in vitro cleavage of the sensitive effector caspase substrate DEVD-amc, caspase activity within these cells was 10- to 20-fold higher than that within mock-infected cells and comparable to that within infected cells not treated with dsRNA (Fig. 7C). Thus, control dsRNAs had no effect on the capacity of AcMNPV to trigger apoptosis.

FIG. 7.

Effect of RNAi on AcMNPV-induced apoptosis of Spodoptera cells. (A) Inhibition of apoptotic cytolysis. Normal SF21 cells were transfected without (none) or with the indicated dsRNAs, infected with p35 deletion mutant vΔ35K/lacZ (MOI, 10), and photographed 24 h later (250× magnification). (B) Immunoblots. Normal SF21 cells transfected with the indicated dsRNAs were lysed at the indicated hours (h) after infection with vΔ35K/lacZ or mock infection (mi) and subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-IE1 (first row), anti-GP64 (second row), anti-Sf-caspase-1 (Sfcasp1; third row), or antiactin (fourth row). Protein size standards (in kilodaltons) are indicated. α, anti. (C) Intracellular caspase activity. CHAPS-treated lysates of SF21 cells transfected with the indicated dsRNAs were prepared 24 h after mock infection (−) or infection (+) with vΔ35K/lacZ (MOI, 10) and assayed for intracellular caspase activity by using the fluorogenic substrate DEVD-amc. Values are reported in relative light units (RLU) and represent the average caspase activities ± standard deviations determined from triplicate infections. sub, subunit.

In contrast, SF21 cells treated with ie-1/ie-0 dsRNA failed to undergo vΔ35K/lacZ-induced apoptosis. By 24 h after infection, >90% of these cells remained intact (Fig. 7A, panel iv). Pro-Sf-caspase-1 levels remained constant, and little or no processing of the large/small subunit was detected (Fig. 7B, lanes 13 to 16). Caspase activity was correspondingly reduced in ie-1/ie-0-silenced cells (Fig. 7C). Levels of GP64 were similar in ie-1/ie-0 and egfp dsRNA-treated cells (Fig. 7B, lanes 2 to 4 and 14 to 16, respectively), indicating that the infections were comparable. We concluded that de novo-synthesized IE1 and/or IE0 is required for AcMNPV-induced apoptosis of permissive SF21 cells. Due to the toxicity of exon0 dsRNA, we could not assess the proapoptotic contribution of IE0 alone.

IE1 is required for AcMNPV-induced apoptosis of nonpermissive cells.

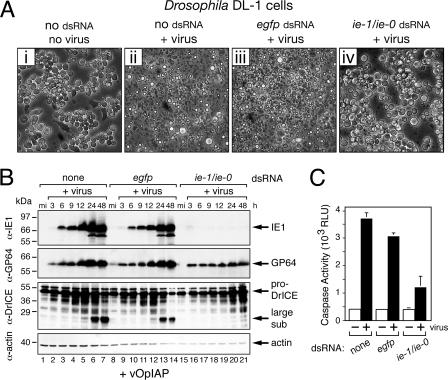

To confirm the role of IE1 in baculovirus-induced apoptosis, we used RNAi to ablate IE1 in DL-1 cells, a Drosophila melanogaster cell line that is readily transfected with dsRNA (25, 54). Even though DL-1 cells are not permissive for AcMNPV (35), they undergo widespread, caspase-mediated apoptosis upon inoculation with p35-null mutants (25, 62). Interestingly, IE1, but not IE0, is synthesized in infected DL-1 cells (see below). Thus, these cells also provided an opportunity to assess proapoptotic functions of IE1 in the absence of IE0.

To trigger apoptosis, we inoculated DL-1 cells with AcMNPV recombinant vOpIAP, which lacks p35 but carries an inserted copy of inhibitor-of-apoptosis gene Op-iap (Fig. 1). Op-iap prevents apoptosis in SF21 cells and thus facilitates production of high-titered virus stock for inoculation of DL-1 cells, where Op-iap is nonfunctional (25, 61, 62). Transfection of DL-1 cells with control dsRNA had no effect on vOpIAP-induced apoptosis; >95% of the cells underwent membrane blebbing and cytolysis by 24 h after inoculation with or without egfp dsRNA (Fig. 8A, panels ii and iii). In contrast, vOpIAP failed to cause apoptosis of ie-1/ie-0 dsRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 8A, panel iv); these cells remained intact with little or no cytolysis by 24 h after inoculation. IE1 was produced at normal levels in the presence of egfp dsRNA but was reduced below the levels of detection in ie-1/ie-0 dsRNA-treated cells (Fig. 8B, lanes 16 to 21). IE0 was not detected in treated or untreated cells after infection with vOpIAP (Fig. 8B) or other AcMNPV recombinants (data not shown). Infection of each dsRNA-treated culture was confirmed by the nearly normal accumulation of GP64 (Fig. 8B). We concluded that IE1, not IE0, is required to induce apoptosis upon infection of Drosophila cells.

FIG. 8.

Effect of RNAi on AcMNPV-induced apoptosis of Drosophila cells. (A) DL-1 cells were transfected without (no dsRNA) or with the indicated dsRNAs, inoculated 24 h later with apoptosis-inducing recombinant vOpIAP (+virus) (panels ii to iv), and photographed (500× magnification) 24 h after infection. Uninfected cells (no virus, no dsRNA) were included (panel i). (B) Immunoblots. DL-1 cells transfected as described for panel A were collected and lysed at the indicated hours (h) after infection with vOpIAP (+virus) and subjected to immunoblot analysis by using anti-IE1 (first row), anti-GP64 (second row), anti-DrICE (third row), or antiactin (fourth row). Protein size standards (in kilodaltons) are indicated. Lysates from mock-infected (mi) cells were included. α, anti. (C) Intracellular caspase activity. CHAPS-treated lysates of DL-1 cells transfected with the indicated dsRNAs were prepared 24 h after mock infection (−) or infection (+) with p35-deficient vOpIAP (MOI, 20) and assayed for intracellular caspase activity by using DEVD-amc as substrate. Values are reported in relative light units (RLU) and represent the average caspase activities ± standard deviations determined from triplicate infections.

To define the step at which apoptosis was blocked upon ie-1 silencing, we monitored the activation of endogenous DrICE, the principal Drosophila effector caspase that is required for AcMNPV-induced apoptosis (25). Whereas pro-DrICE was proteolytically processed to its active large/small subunit form in untreated and egfp dsRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 8B, lanes 2 to 7 and 9 to 14), little if any processing was detected in ie-1-silenced cells through 48 h (lanes 16 to 21). Only low levels of intracellular caspase activity were detected in these cells (Fig. 8C), confirming the lack of DrICE activation. By comparison, intracellular caspase activity 24 h after infection of untreated cells or egfp dsRNA-transfected cells was threefold to fourfold greater (Fig. 8C). We concluded that IE1 triggers apoptosis at a step prior to the activation of host Drosophila caspases. Moreover, because de novo expression of ie-1 is required, the trigger for apoptosis is IE1 itself, an IE1-dependent gene, or an IE1-required replicative event occurring after virus entry.

DISCUSSION

IE1 is a transcriptional activator that is essential for virus multiplication and conserved among lepidopteran baculoviruses (15). Here, for the first time, we have used an RNAi approach to define and quantify the functional roles of IE1 in the AcMNPV life cycle when initiated by receptor-mediated entry of infectious virus. We report that IE1 is necessary for transcriptional activation of AcMNPV genes, including its own gene, to promote virus replication. Nonetheless, IE1 and its relative IE0 differentially activate early AcMNPV promoters to ensure proper levels of gene expression. Our study also demonstrates a critical role for IE1 in triggering the widespread apoptosis associated with AcMNPV. Remarkably, IE1 counteracts its own proapoptotic activity by timely transactivation of the apoptotic suppressor p35 to prevent cell death prior to virus maturation. Thus, IE1 has multifaceted roles in promoting multiplicative success and blocking antiviral responses that contribute to the effectiveness of baculoviruses as viral vectors for foreign gene expression.

IE1 is essential for AcMNPV multiplication.

RNAi that was accomplished by gene-specific dsRNA transfection proved to be an efficient means to ablate IE1 and IE0 during infection (Fig. 2, 5, and 7). By monitoring gene expression and replicative events in the absence of either transactivator, we confirmed the critical nature of IE1 and the accessory role of IE0 for baculovirus multiplication (30, 56, 58). A previously used genetic knockout approach demonstrated that the ie-1/ie-0 complex is essential for AcMNPV multiplication (56). Moreover, either IE1 or IE0 alone is sufficient to support virus multiplication, albeit at less-than-wt levels. Here, we found that simultaneous ablation of IE1 and IE0 severely limited production of BV and occluded virus (Fig. 3). In contrast, selective loss of IE0 had only a minor effect on expression of polh, which is required for occluded virus production. Thus, IE0 is dispensable for those replicative events that activate very late virus gene expression. Although BV yields decreased upon ie-0 silencing (Fig. 3D), this negative effect was attributed to cosilencing of exon0 (AcMNPV ORF ac141), which overlaps ie-0 (Fig. 2) and is necessary for BV production (11, 59).

Early AcMNPV genes are differentially regulated by IE1.

The promoters of numerous baculovirus early genes and some host genes respond positively to IE1 in transient expression assays (3, 13, 21, 22, 31, 38, 44, 49). Thus, IE1 appeared to be a broad-spectrum, nonspecific transcriptional activator. However, our study here revealed that IE1 differentially regulates promoters during infection. For example, early expression of AcMNPV p35 was highly sensitive to loss of IE1 and IE0 (Fig. 5 and 6). p35 promoter activity decreased dramatically in the absence of IE1, indicating that IE1 positively regulates p35 at the transcriptional level. Selective ablation of IE0 also reduced p35 expression. Thus, IE0 may exert a positive effect on p35 transcription, but this activity could be an indirect effect of IE0 on IE1 (see below). Unlike p35, early gp64 expression was less dependent on IE1 and IE0. In both SF21 and DL-1 cells (Fig. 5 and 8), GP64 levels were minimally affected by ie-1/ie-0 silencing. These data suggested that despite the sensitivity of the gp64 promoter to upregulation by IE1 in transfection assays (3), IE1 has little impact on gp64 expression during infection. It is noteworthy that the gp64 promoter is active in uninfected cells in the absence of viral factors, whereas the p35 promoter is not (3, 38). Thus, it is likely that the two promoters possess different cis-acting regulatory elements, including those responsive to IE1. Indeed, AcMNPV may gain a significant multiplicative advantage by requiring IE1 for activation of p35. Because the p35-encoded caspase inhibitor P35 prevents IE1-triggered apoptosis (see below), use of an IE1-dependent promoter to direct timely early expression of p35 provides an efficient fail-safe mechanism by which to block the host's apoptotic response and thereby ensure maximum replicative potential.

IE0 regulates ie-1 transcription.

Despite its similarity to IE1 and the ability to partially substitute for IE1 in engineered baculoviruses (56), the functional role of IE0 during infection is unknown. We found here that selective ablation of IE0 delayed the appearance of IE1 and reduced IE1 steady-state levels (Fig. 2 and 5). Furthermore, ie-1 promoter activity was reduced fivefold upon ie-1/ie-0 silencing (Fig. 6). We concluded that IE0 stimulates transcription of ie-1 early during infection. Consistent with this conclusion, IE0 enhanced ie-1 promoter activity in plasmid transfection assays (21). These findings suggest that IE0 functions to accelerate the build-up of intracellular IE1 early in infection to promote the replicative program of the virus. Consequently, IE0 may indirectly activate IE1-responsive genes by upregulating IE1, a possibility that accounts for the apparent stimulation of p35 expression by IE0 (Fig. 6).

IE1 autoregulation is cell specific.

The ie-1 promoter is highly active in uninfected cells from a variety of insects and does not require AcMNPV-specific factors (21, 25, 47). Thus, it was unexpected that, when embedded within the AcMNPV genome, the ie-1 promoter was inactive in a majority (80 to 90%) of ie-1/ie-0-silenced cells (Fig. 6A, panel vii). This finding suggested that IE1, IE0, or both are required for ie-1 expression during infection. Alternatively, viral or host negative regulatory factors may prevail in the absence of IE1 or IE0 to repress the ie-1 promoter. However, this is not the case for all cells, because the ie-1 promoter remained active in a small fraction (<20%) of ie-1/ie-0-silenced vIE1prm-EGFP-infected cells (Fig. 6A, panel vii). This unique expression pattern accounted for the increased reporter activity of virus vIE1FL-FCAT (Fig. 6D), which indicated high-level ie-1 promoter activity in these few cells. We initially speculated that the continued activity of the ie-1 promoter was due to a block in the normal transition from early to late stages of AcMNPV replication. However, this possibility is unlikely, because the same disparate pattern of ie-1 promoter activity was not observed when RNA silencing of viral DNA replication factors was used to block the normal transition from early to late phases (K. Schultz and P. Friesen, unpublished data). As an alternative possibility, IE1 may negatively regulate its own promoter in a strategy to limit ie-1 expression late in infection in some cells. Thus, RNAi-mediated reduction of IE1 would cause an increase in ie-1 promoter activity. Lastly, because the ie-1 promoter responds to host-specific transcription factors, it is possible that cell cycle-dependent differences in the availability of such factors affect promoter activity when IE1 levels are lower early during infection. Additional study is required to distinguish these interesting possibilities.

IE1 is required for AcMNPV-induced apoptosis.

Among DNA viruses, AcMNPV is an unusually potent inducer of apoptosis. Within a 24-h period, AcMNPV mutants lacking apoptotic suppressors cause apoptotic death of >90% of the cells of susceptible cell lines (Fig. 7 and 8). As such, baculoviruses have provided an advantageous model for defining the molecular mechanisms by which animal viruses trigger apoptosis and associated pathologies (6, 12). IE1 has been implicated as a proapoptotic factor by virtue of its capacity to cause low-level apoptosis upon overexpression (46) and the contribution of early AcMNPV replication events in apoptosis (7, 23). Here, we found that ie-1/ie-0 silencing was sufficient to block apoptosis induced by p35-deficient AcMNPV mutants in permissive SF21 cells (Fig. 7A). Although virus entry and IE1-independent gene expression occurred in ie-1/ie-0-silenced cells, the biochemical hallmarks of apoptosis, including host caspase activation, failed to appear (Fig. 7). We concluded that de novo-synthesized IE1 is required either directly or indirectly (see below) for virus-induced apoptosis. This study provides the first direct evidence that IE1 contributes to apoptosis in the context of the baculovirus-infected cell. Thus, our findings support the conclusion that receptor engagement during AcMNPV entry is insufficient to trigger apoptosis and that virus-specific gene expression or replication events are required (7, 23).

The proapoptotic role of IE1 was confirmed by using Drosophila DL-1 cells. Although Drosophila (order Diptera) is not permissive for AcMNPV, inoculation of Drosophila cells causes widespread apoptosis that is caspase dependent (25, 61, 62). RNAi-mediated silencing of ie-1 blocked AcMNPV-mediated cytolysis, caspase activation, and proteolytic processing of effector caspase DrICE (Fig. 8), which is required for virus-induced apoptosis (25). Because IE0 was not produced during infection of DL-1 cells (Fig. 8B), we concluded that this transactivator is not required for the triggering of apoptosis. Due to its dispensability for AcMNPV multiplicative functions (56), we also suspect that IE0 is not required for virus-induced apoptosis of permissive SF21 cells.

IE1 may play a direct or indirect role in promoting AcMNPV-induced apoptosis. Virus-encoded transcription factors, including adenovirus E1A and human immunodeficiency virus Tat, are proapoptotic, and some DNA viruses induce transcription factors that contribute to viral DNA replication or perturb the cell cycle to trigger apoptosis (reviewed in references 1, 2, 26, and 37). Thus, IE1 might activate prodeath genes or alter the cell cycle of the host. Several lines of evidence also suggest that AcMNPV DNA replication contributes to virus-induced apoptosis (7, 23). Indeed, initiation of AcMNPV DNA synthesis coincides with caspase activation (23, 24). Thus, by activating genes required for viral DNA synthesis or by participating in DNA replication, IE1 may indirectly trigger apoptosis. In support of this possibility, preliminary RNAi experiments indicated that AcMNPV DNA replication factors are required for virus-induced apoptosis in Spodoptera and Drosophila cells (Schultz and Friesen, unpublished). Further studies on the role of viral DNA replication in the host apoptotic response will clarify the proapoptotic activity of IE1. Importantly, defining the mechanisms by which baculoviruses trigger apoptosis will lead to a greater understanding of how arthropods respond to viral infections and thereby transmit viral disease to humans.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yuri Lazebnik (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory) and Gary Blissard (Cornell University) for the gifts of P35 and GP64 monoclonal antibodies, respectively.

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grants AI25557 and AI40482 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (P.D.F.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 October 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alimonti, J. B., T. B. Ball, and K. R. Fowke. 2003. Mechanisms of CD4+ T lymphocyte cell death in human immunodeficiency virus infection and AIDS. J. Gen. Virol. 841649-1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berk, A. J. 2005. Recent lessons in gene expression, cell cycle control, and cell biology from adenovirus. Oncogene 247673-7685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blissard, G. W., and G. F. Rohrmann. 1991. Baculovirus gp64 gene expression: analysis of sequences modulating early transcription and transactivation by IE1. J. Virol. 655820-5827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chisholm, G. E., and D. J. Henner. 1988. Multiple early transcripts and splicing of the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus IE-1 gene. J. Virol. 623193-3200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi, J., and L. A. Guarino. 1995. A temperature-sensitive IE1 protein of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus has altered transactivation and DNA binding activities. Virology 20990-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clem, R. J. 2007. Baculoviruses and apoptosis: a diversity of genes and responses. Curr. Drug Targets 81069-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clem, R. J., and L. K. Miller. 1994. Control of programmed cell death by the baculovirus genes p35 and iap. Mol. Cell. Biol. 145212-5222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dai, X., T. M. Stewart, J. A. Pathakamuri, Q. Li, and D. A. Theilmann. 2004. Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus exon0 (orf141), which encodes a RING finger protein, is required for efficient production of budded virus. J. Virol. 789633-9644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dai, X., L. G. Willis, I. Huijskens, S. R. Palli, and D. A. Theilmann. 2004. The acidic activation domains of the baculovirus transactivators IE1 and IE0 are functional for transcriptional activation in both insect and mammalian cells. J. Gen. Virol. 85573-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickson, J. A., and P. D. Friesen. 1991. Identification of upstream promoter elements mediating early transcription from the 35,000-molecular-weight protein gene of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J. Virol. 654006-4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang, M., X. Dai, and D. A. Theilmann. 2007. Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus EXON0 (ORF141) is required for efficient egress of nucleocapsids from the nucleus. J. Virol. 819859-9869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friesen, P. D. 2007. Insect viruses, p. 707-736. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed., vol. 1. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guarino, L. A., and M. Smith. 1992. Regulation of delayed-early gene transcription by dual TATA boxes. J. Virol. 663733-3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guarino, L. A., and M. D. Summers. 1987. Nucleotide sequence and temporal expression of a baculovirus regulatory gene. J. Virol. 612091-2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayakawa, T., G. F. Rohrmann, and Y. Hashimoto. 2000. Patterns of genome organization and content in lepidopteran baculoviruses. Virology 2781-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hershberger, P. A., J. A. Dickson, and P. D. Friesen. 1992. Site-specific mutagenesis of the 35-kilodalton protein gene encoded by Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus: cell line-specific effects on virus replication. J. Virol. 665525-5533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hohmann, A. W., and P. Faulkner. 1983. Monoclonal antibodies to baculovirus structural proteins: determination of specificities by Western blot analysis. Virology 125432-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanginakudru, S., C. Royer, S. V. Edupalli, A. Jalabert, B. Mauchamp, S. V. Prasad, G. Chavancy, P. Couble, and J. Nagaraju. 2007. Targeting ie-1 gene by RNAi induces baculoviral resistance in lepidopteran cell lines and in transgenic silkworms. Insect Mol. Biol. 16635-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kool, M., C. H. Ahrens, R. W. Goldbach, G. F. Rohrmann, and J. M. Vlak. 1994. Identification of genes involved in DNA replication of the Autographa californica baculovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9111212-11216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kost, T. A., J. P. Condreay, and D. L. Jarvis. 2005. Baculovirus as versatile vectors for protein expression in insect and mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 23567-575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovacs, G. R., L. A. Guarino, and M. D. Summers. 1991. Novel regulatory properties of the IE1 and IE0 transactivators encoded by the baculovirus Autographa californica multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J. Virol. 655281-5288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kremer, A., and D. Knebel-Morsdorf. 1998. The early baculovirus he65 promoter: on the mechanism of transcriptional activation by IE1. Virology 249336-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LaCount, D. J., and P. D. Friesen. 1997. Role of early and late replication events in induction of apoptosis by baculoviruses. J. Virol. 711530-1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaCount, D. J., S. F. Hanson, C. L. Schneider, and P. D. Friesen. 2000. Caspase inhibitor P35 and inhibitor of apoptosis Op-IAP block in vivo proteolytic activation of an effector caspase at different steps. J. Biol. Chem. 27515657-15664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lannan, E., R. Vandergaast, and P. D. Friesen. 2007. Baculovirus caspase inhibitors P49 and P35 block virus-induced apoptosis downstream of effector caspase DrICE activation in Drosophila melanogaster cells. J. Virol. 819319-9330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lavia, P., A. M. Mileo, A. Giordano, and M. G. Paggi. 2003. Emerging roles of DNA tumor viruses in cell proliferation: new insights into genomic instability. Oncogene 226508-6516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee, H. H., and L. K. Miller. 1978. Isolation of genotypic variants of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J. Virol. 27754-767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leisy, D. J., C. Rasmussen, H.-T. Kim, and G. F. Rohrmann. 1995. The Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus homologous region 1a: identical sequences are essential for DNA replication activity and transcriptional enhancer function. Virology 208742-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu, A., and L. K. Miller. 1995. The roles of eighteen baculovirus late expression factor genes in transcription and DNA replication. J. Virol. 69975-982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu, L., H. Rivkin, and N. Chejanovsky. 2005. The immediate-early protein IE0 of the Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus is not essential for viral replication. J. Virol. 7910077-10082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu, M. L., R. R. Johnson, and K. Iatrou. 1996. Trans-activation of a cell housekeeping gene promoter by the IE1 gene product of baculoviruses. Virology 218103-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manji, G. A., R. R. Hozak, D. J. LaCount, and P. D. Friesen. 1997. Baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis functions at or upstream of the apoptotic suppressor P35 to prevent programmed cell death. J. Virol. 714509-4516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matzke, M. A., and J. A. Birchler. 2005. RNAi-mediated pathways in the nucleus. Nat. Rev. Genet. 624-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Means, J. C., I. Muro, and R. J. Clem. 2003. Silencing of the baculovirus Op-iap3 gene by RNA interference reveals that it is required for prevention of apoptosis during Orgyia pseudotsugata M nucleopolyhedrovirus infection of Ld652Y cells. J. Virol. 774481-4488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris, T. D., and L. K. Miller. 1993. Characterization of productive and non-productive AcMNPV infection in selected insect cell lines. Virology 197339-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagamine, T., Y. Kawasaki, T. Iizuka, and S. Matsumoto. 2005. Focal distribution of baculovirus IE1 triggered by its binding to the hr DNA elements. J. Virol. 7939-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen, M. L., and J. A. Blaho. 2007. Apoptosis during herpes simplex virus infection. Adv. Virus Res. 6967-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nissen, M. S., and P. D. Friesen. 1989. Molecular analysis of the transcriptional regulatory region of an early baculovirus gene. J. Virol. 63493-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okano, K., A. L. Vanarsdall, V. S. Mikhailov, and G. F. Rohrmann. 2006. Conserved molecular systems of the Baculoviridae. Virology 344:77-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olson, V. A., J. A. Wetter, and P. D. Friesen. 2002. Baculovirus transregulator IE1 requires a dimeric nuclear localization element for nuclear import and promoter activation. J. Virol. 769505-9515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olson, V. A., J. A. Wetter, and P. D. Friesen. 2001. Oligomerization mediated by a helix-loop-helix-like domain of baculovirus IE1 is required for early promoter transactivation. J. Virol. 756042-6051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olson, V. A., J. A. Wetter, and P. D. Friesen. 2003. The highly conserved basic domain I of baculovirus IE1 is required for hr enhancer DNA binding and hr-dependent transactivation. J. Virol. 775668-5677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Passarelli, A. L., and L. A. Guarino. 2007. Baculovirus late and very late gene regulation. Curr. Drug Targets 81103-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Passarelli, A. L., and L. K. Miller. 1993. Three baculovirus genes involved in late and very late gene expression: ie-1, ie-n, and lef-2. J. Virol. 672149-2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pearson, M., R. Bjornson, G. Pearson, and G. Rohrmann. 1992. The Autographa californica baculovirus genome: evidence for multiple replication origins. Science 2571382-1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prikhod'ko, E. A., and L. K. Miller. 1996. Induction of apoptosis by baculovirus transactivator IE1. J. Virol. 707116-7124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pullen, S. S., and P. D. Friesen. 1995. Early transcription of the ie-1 transregulator gene of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus is regulated by DNA sequences within its 5′ noncoding leader region. J. Virol. 69156-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quadt, I., J. W. van Lent, and D. Knebel-Morsdorf. 2007. Studies of the silencing of baculovirus DNA binding protein. J. Virol. 816122-6127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ribeiro, B. M., K. Hutchinson, and L. K. Miller. 1994. A mutant baculovirus with a temperature-sensitive IE-1 transregulatory protein. J. Virol. 681075-1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rodems, S. M., and P. D. Friesen. 1995. Transcriptional enhancer activity of hr5 requires dual-palindrome half sites that mediate binding of a dimeric form of the baculovirus transregulator IE1. J. Virol. 695368-5375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodems, S. M., S. S. Pullen, and P. D. Friesen. 1997. DNA-dependent transregulation by IE1 of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus: IE1 domains required for transactivation and DNA binding. J. Virol. 719270-9277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schneider, I. 1972. Cell lines derived from late embryonic stages of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 27353-365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seed, B., and J. Y. Sheen. 1988. A simple phase-extraction assay for chloramphenicol acyltransferase activity. Gene 67271-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Settles, E. W., and P. D. Friesen. 2008. Flock house virus induces apoptosis by depletion of Drosophila inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein DIAP1. J. Virol. 821378-1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Slack, J. M., and G. W. Blissard. 1997. Identification of two independent transcriptional activation domains in the Autographa californica multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus IE1 protein. J. Virol. 719579-9587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stewart, T. M., I. Huijskens, L. G. Willis, and D. A. Theilmann. 2005. The Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus ie0-ie1 gene complex is essential for wild-type virus replication, but either IE0 or IE1 can support virus growth. J. Virol. 794619-4629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Theilmann, D. A., and S. Stewart. 1993. Analysis of the Orgyia pseudotsugata multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus trans-activators IE-1 and IE-2 using monoclonal antibodies. J. Gen. Virol. 741819-1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valdes, V. J., A. Sampieri, J. Sepulveda, and L. Vaca. 2003. Using double-stranded RNA to prevent in vitro and in vivo viral infections by recombinant baculovirus. J. Biol. Chem. 27819317-19324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vanarsdall, A. L., M. N. Pearson, and G. F. Rohrmann. 2007. Characterization of baculovirus constructs lacking either the Ac 101, Ac 142, or the Ac 144 open reading frame. Virology 367187-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vaughn, J. L., R. H. Goodwin, G. J. Tompkins, and P. McCawley. 1977. The establishment of two cell lines from the insect Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera; Noctuidae). In Vitro 13213-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wright, C. W., J. C. Means, T. Penabaz, and R. J. Clem. 2005. The baculovirus antiapoptotic protein Op-IAP does not inhibit Drosophila caspases or apoptosis in Drosophila S2 cells and instead sensitizes S2 cells to virus-induced apoptosis. Virology 33561-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zoog, S. J., J. J. Schiller, J. A. Wetter, N. Chejanovsky, and P. D. Friesen. 2002. Baculovirus apoptotic suppressor P49 is a substrate inhibitor of initiator caspases resistant to P35 in vivo. EMBO J. 215130-5140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]