Abstract

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) is a transcriptional activator that promotes death or survival in neurons. The regulators and targets of HIF-1α–mediated death remain unclear. We found that prodeath effects of HIF-1 are not attributable to an imbalance in HIF-1α and HIF-1β expression. Rather, the synergistic death caused by oxidative stress and by overexpression of an oxygen-resistant HIF-VP16 in neuroblasts was attributable to transcriptional upregulation of BH3-only prodeath proteins, PUMA or BNIP3. By contrast, overexpression of BNIP3 was not sufficient to potentiate oxidative death. As acidosis is known to activate BNIP3-mediated death, we examined other secondary stresses, such as oxidants or prolyl hydroxylase activity are necessary for exposing the prodeath functions of HIF in neurons. Antioxidants or prolyl hydroxylase inhibition prevented potentiation of death by HIF-1α. Together, these studies suggest that antioxidants and PHD inhibitors abrogate the ability of HIF-mediated transactivation of BH3-only proteins to potentiate oxidative death in normoxia. The findings offer strategies for minimizing the prodeath effects of HIF-1 in neurologic conditions associated with hypoxia and oxidative stress, such as stroke and spinal cord injury. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 1989–1998.

Introduction

During the past decade, hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) has attracted the attention of many investigators because of its ability to mediate adaptive cellular responses to a change in oxygen tension. HIF-1 is a transcription factor that is composed of two subunits, HIF-1α and HIF-1β [also known as aryl hydrocarbon nuclear translocator ARNT)] (21). Both subunits are expressed constitutively; however, whereas HIF-1β protein levels are relatively constant, HIF-1α is subject to ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation under normoxic conditions. An oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODD) located at amino acids 401–603 is responsible for the protein instability in HIF-1α. Under normoxic conditions, prolyl-4 hydroxylases (PHDs) that are specific toward HIF-1α hydroxylate two proline residues in the ODD domain of HIF-1α. The von Hippel-Lindau protein (VHL) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex associates with a hydroxylated proline residue and targets HIF-1α for proteosomal degradation (7–11, 19). PHD is an oxygen-dependent enzyme that also requires Fe2+, ascorbate, and 2-oxoglutarate for its activity. During hypoxia, oxygen becomes rate limiting, and HIF-1α accumulates, migrates to the nucleus, associates with HIF-1β, and the complex binds to a hypoxia-response element of target genes. Besides HIF-1α, a number of other BHLH/PAS family proteins are also able to form heterodimers with HIF-1β. Dimerization with aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), formed in response to xenobiotics, results in activation of P4501A1, quinine reductase, and glutathione S-transferase genes (15, 16). Dimerization with SIM (single-minded) protein leads to repression of HIF-1β (15, 16). The role of homodimeric HIF-1β remains unclear.

HIF-1 upregulates a number of responses important for adaptation to low oxygen tension, including erythropoietin, glycolytic enzymes, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Previous studies from our laboratory demonstrated that pharmacological activators of HIF-1 could also protect cultured neurons from oxidative stress-induced death (29). While examining whether HIF-1 activation is sufficient to abrogate neuronal death due to oxidative stress, we found that the stable expression of HIF-1α potentiates cell death induced by glutamate toxicity but protects cells from ER stress–and DNA damage–induced death (1).

A number of models exist showing how HIF-1α could enhance death. First, HIF-1α could induce cell death by stimulating expression of key proapoptotic Bcl2-family BH3-only proteins, such as BNIP3 (Bcl2/Adenovirus E1B 19-kD interaction protein 3), NIX (BNIP3L), and NOXA (2, 5, 25). Proapoptotic members of the Bcl2 family can be separated into two subfamilies. The first includes the “multidomain” proteins (Bax and Bak) that share three BH regions contained in antiapoptotic proteins but lack the BH4 domain. The second group described earlier includes the “BH3-only” proteins (BNIP3, NIX/BNIP3L, NOXA, PUMA, Bid, and Bad). In contrast to multidomain proteins, BH3-only proteins are structurally diverse. HIF-1 stabilization is believed to lead to the transcriptional upregulation of BH3-only–containing proteins via at least two defined mechanisms. First, heterodimeric HIF-1 can bind to hypoxia response elements in the promoters of proteins such as BNIP3 and increase the BNIP3 message (2, 4, 13, 26). Second, if HIF-1α is induced out of proportion to its dimeric partner HIF-1β, it may also binds to p53 and stabilizes it, leading to transcriptional upregulation of p53-dependent BH3-only family members, including NOXA or PUMA (3, 5, 28).

The most investigated BH3-only family member that is known to be induced by hypoxia, mimics of hypoxia, or hypoxia/ischemia is BNIP3. It was shown that BNIP3 causes cell death via apoptotic, autophagic, or necrotic pathways (24, 25, 27). Cellular localization of BNIP3 is important for induction of cell death. In cardiac myocytes, hypoxia-induced expression of BNIP3 does not lead to cell death; concomitant acidosis is required to activate the death pathway via necrosis (14). BNIP3 was also found to be insufficient to cause death in fibroblasts and tumor lines. Acidosis is believed to change the conformation of BNIP3 protein, increase its association with mitochondrial membranes, and stimulate aberrant membrane permeability (25). By contrast, BNIP3 overexpession in ventricular myocytes caused apoptotic death via a caspase-regulated pathway (18). It was shown, that in rat hippocampus, global brain ischemia results in the nuclear localization of BNIP3, raising the intriguing possibility that BNIP3 could mediate deleterious responses in neurons via nuclear rather than mitochondrial pathways (20). These data support a role for BNIP3 in ischemic neuronal death, but its role in oxidative normoxic death remains poorly explored.

We show that BNIP3 and PUMA are transcriptionally upregulated in response to HIF overexpression and that both are necessary for the potentiation of oxidative death. The transcriptional upregulation of BH3-only proteins and enhancement of oxidative death is unlikely related to the imbalance between HIF-1α and HIF-1β. Finally, consistent with prior results that indicate that a secondary state change is necessary in the cell to activate BH3-only proteins-induced cell death, we show that antioxidants or HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors abolish the increased death induced by forced HIF expression. Together, these studies establish strategies to limit the prodeath effects of HIF in the nervous system.

Experimental Procedures

Plasmids and retroviruses

Plasmids encoding a fusion protein that comprises aa 1-529 of HIF-1α and the herpes simplex virus VP16 transactivation domain, pBABE-puro-HIF-1α-VP16, and a control plasmid encoding only VP16, pBABE-puro-VP16, have been described previously. The retroviral vector MSCV-IRES-GFP-ARNT expressing human ARNT1 (HIF-1β1) protein was the kind gift of Dr. Oliver Hankinson (University of California). The coding region of murine BNIP3 was generated by RT-PCR (AB-gene) from total RNA of HT22 cells treated with DFO at the concentration of 100 μM overnight and cloned into the pBabe retroviral vector between the BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites. For immunofluorescence studies, the BNIP3 coding region was cloned into pEGFP (Clontech) plasmid and expressed as GFP-BNIP3 fusion protein in mammalian cells. A short interfering RNA (shRNA) was cloned into the pSuper-Retro vector (OligoEngine, Seattle, WA) under the control of a polymerase-III H1-RNA gene promoter. RNAis that correspond to the BNIP3 and GFP genes were designed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Target sequences for shRNA against BNIP3 were 5'-TGGCAATGGGAGCAGCGTT, against shGFP 5'-GCAAGCTGACCCTGAAGTTC, and against PUMA, 5'-GGGTCATGTACAATCTCTTCA. Oligonucleotides were annealed and cloned into the BglII/HindIII site of the vector. The MLV-based viruses were generated by tripartite transfection of 293T cells, and viral supernatant was concentrated by using Amicon Ultra-15 100-kDa membrane (Cat#UFC910008, Millipore). The viruses also were purchased from Harvard Gene Therapy Initiative (Boston, MA).

Cell culture and virus infection

HT22 murine hippocampal cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen). Cells were plated on a 12-well plate at the density of 5 × 104 cells/ml for 16 h before infection. Cells were infected with retroviruses in the presence of hexadimethrine bromide (4 μg/ml) (Sigma) at MOI 10 and, after 24-h incubation, were selected with puromycin (4 μg/ml) (Sigma).

Immunoblotting

After washing in cold PBS, the cell pellets were used for nuclear extract preparation with the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction kits (Pierce) or lysed with the lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1% SDS, 1% P-40, 0.55 oxycholate, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)]. After 20-min incubation on ice, the extracts were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined with the Protein Assay Reagent (Bio-Rad) by using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Protein extracts were electrophoresed and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher and Schuell) by using the standard procedure. Primary monoclonal antibodies against HIF-1β (100–124) were obtained from Novus Biologicals. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against BNIP3 were kindly provided by Dr. R. Bruick. The bands were visualized with the ECL system (Amersham Biosciences). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Primary antibody against PUMA was obtained from cell signaling technology, Inc. (Cat#4976). Secondary fluorophore conjugated odyssey IRDye-680 or IRD-800 antibodies from LI-COR Biosciences. Immunoreactive proteins were detected by using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences).

Immunofluorescence staining

HT22 cells were transfected with pEGFP-BNIP3 and pDsRed2-mito (Clontech) or with pBabe encoding HIF-VP16 or VP16 only and pDsRed2-Mito for 24 h and then fixed and permeabilized according to standard protocol. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated for 1 h in blocking solution containing PBS, 5% goat serum (Invitrogen), and 1% BSA. In case of BNIP3 induction using HIF-1α-VP16 expression, the cells were stained with antibodies against BNIP3 for 1 h at 37°C and then washed 3 times with PBS and incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody coupled with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen). High-resolution images were obtained with a DMI4000 Leica microscope, ×63 oil objective (Image Pro Plus, MedlaCybernetics)

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA from control and infected cells was isolated 1 week after infection and selection with puromycin by using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen), followed by in-column treatment with DNase (Qiagen). Reverse-transcription reaction (30 min at 50°C) and PCR amplification were carried out with the Reverse-IT One-step Kit (ABgene) in a thermal cycler PTC-100 (MJ Research, Inc.) with transcript-specific primers. Total RNA at concentrations of 1, 10, and 50 ng was used for cDNA amplification to confirm the linear range of amplification. cDNA synthesis was carried out at 50°C for 30 min followed by PCR with 4 min of initial denaturation and by 25 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min for amplification with BNIP3-, NIX-, and PUMA-specific primers. For β-actin amplification, a two-step PCR reaction was used with 30 s at 94°C and 1 min at 60°C for 25 cycles.

Viability

The viability of cells was assayed by using the CellTitre 96 Aqueous Assay (Promega, Madison, WI). To ensure that the cells have the same density at the time of treatment (1), they were plated onto a 96-well plate at the density of 2.5 × 104 cells/ml for the VP16-infected cells and at 5 × 104 cells/ml for the HIF-VP16–infected cells and incubated as described earlier. After 24 h of incubation, cells were treated with butylated hydroxyanisole (BH) (10 μM), N-acetyl cysteine (100 μM), dihydroxybenzoate (DHB) (10 μM), deferoxamine mesylate (DFO) (10 μM), dimethyloxylglycine (DMOG) (2.5 mM), Tat-HIF/ODD/wt (HIF-wt) (100 μM), and Tat-HIF/ODD/mut (HIF-mut) (100 μM) peptides (22) in the presence or absence of l-glutamic acid (Sigma) at concentrations from 2 to 20 mM or homocysteic acid (HCA) (5 mM) and assayed for viability as described earlier.

Statistics

Data were subjected to two-way ANOVA or multivariate analysis. The statistical significance of differences between means was assessed by using Neumann–Keuls post hoc tests, as indicated in table and figure legends. The analyses were done by using the Statistica 6.1 software (StatSoft Inc.).

Results

Co-expression with HIF-1β

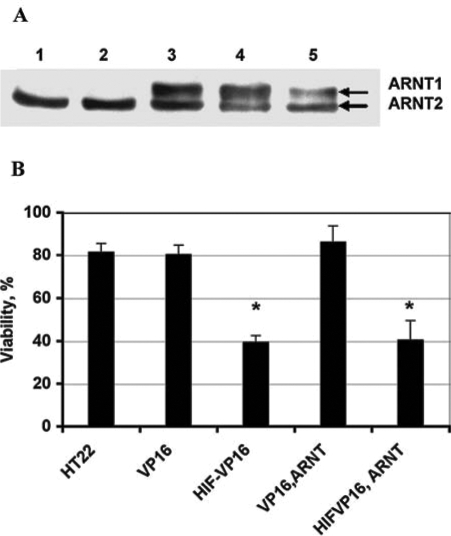

Prior studies from our laboratory demonstrated that forced expression of an oxygen-stabilized form of HIF-1α (HIF-VP16) potentiated oxidative death induced by glutamate in a mouse hippocampal neuronal line (1). The potentiation was unlikely related to the nonphysiologic effects of overexpressing a toxic protein in neurons, as molecular reduction in endogenous HIF-1α via RNA interference protected hippocampal neurons from oxidative death. The prodeath effects of HIF-1α are now well described, but the molecular mediators of this effect are less clear (1). One proposed model has been that HIF-1α induces death when a stoichiometric imbalance exists between it and its heterodimeric partner HIF-1β. To determine whether the enhanced sensitivity of HIF-VP16-expressing cells to glutamate toxicity is caused by the imbalance due to forced HIF-1α expression and low, endogenous expression of HIF-1β, we infected HT22 cells with the virus encoding human HIF-1β1 (ARNT1). After the infection, cells were sorted by FACS by using green fluorescence. Selected green fluorescent cells were further infected with viruses encoding VP16 or HIF-VP16. HT22 cells do not express the HIF-1β1 isoform, but only the HIF-1β2. Western blotting confirmed heterologous HIF-1β1 expression in cells infected with the MSCV-IRES-ARNT1 virus (Fig. 1A). Cells expressing VP16 or HIF-VP16 only or coexpressing them together with the HIF-1β1 were plated onto a 96-well plate for the viability assay. The results demonstrated that the coexpression of HIF-1β1 and HIF-VP16 at stoichiometrically similar levels does not protect cells from glutamate-induced toxicity. Cells expressing the fusion protein HIF-VP16 were hypersensitive to glutamate, even in the presence or absence HIF-1β1 (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Effect of HIF-1β expression on HT22 cell sensitivity to glutamate toxicity. HT22 cells were infected with MSCV-ARNT-IRES-GFP retrovirus at MOI of 10 and collected based on their green fluorescence by using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS). FACS-selected cells were infected with pBabe-VP16 or pBabe HIF-VP16 and further selected with puromycin. (A) HIF-1β protein expression. (1) HT22-control, (2) HT22 treated with DFO, (3) HT22 infected with MSCV-ARNT-IRES-GFP retrovirus, (4) HT22 co-infected with MSCV-ARNT-IRES-GFP and VP16 retroviruses, (5) HT22 co-infected with MSCV-ARNT-IRES-GFP and HIF-VP16 retroviruses. (B) The viability of HT22 cells carrying different viral constructs after treatment with 5 mM glutamate. HT22 cells were infected with MSCV-ARNT-IRES-GFP and sorted by FACS for green fluorescence. After cell stabilization, they were infected with pBabe-puro-VP16 or pBabe-puro-HIF-VP16 and selected with puromycin. HT22, control cells; VP16, HT22 cells infected with VP16 retrovirus; HIF-VP16, HT22 cells infected with HIF-VP16 retrovirus; ARNT-VP16, HT22 cells co-infected with MSCV-ARNT-IRES-GFP and VP16 retroviruses; ARNT-HIF, HT22 cells infected with MSCV-ARNT-IRES-GFP and HIF-1α-VP16 retroviruses. *p < 0.0001.

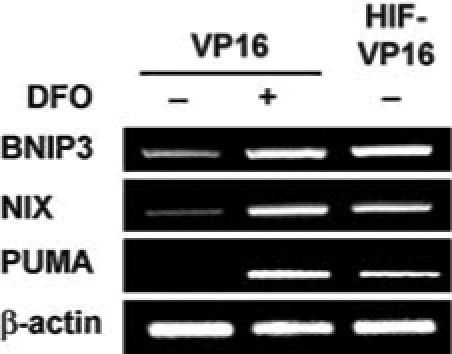

BH3-only protein expression in HIF-VP16-infected cells

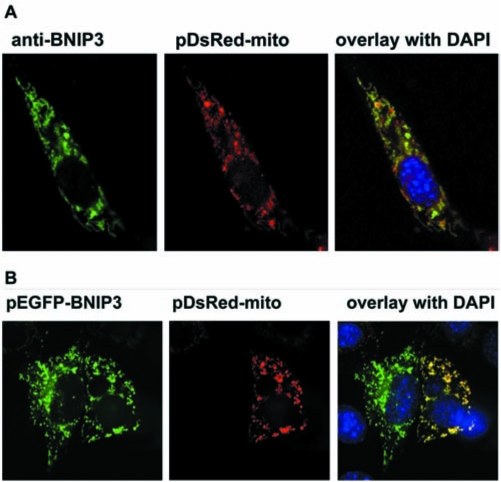

Another model for the elevated sensitivity of HIF-VP16–expressing cells to glutamate involves the increased transcription of prodeath Bcl-2 family proteins such as BNIP3. A number of proteins of this family possess hypoxia-responsive element(s) in their promoter regions (26). To verify that forced expression of HIF-VP16 changes message levels of prodeath proteins, we used semiquantitative RT-PCR. DFO, a canonical stabilizer of HIF-1 and inducer of HIF-mediated transcription, increased the mRNA level of at least three “BH3-only” prodeath family members, BNIP3, NIX, and PUMA (Fig. 2). Expression of HIF-VP16 in hippocampal neuroblasts led to a similar increase of the mRNA levels of the three genes (Fig. 2). In each case, the expression of these genes was not sufficient to induce death, as the viabilities of the samples were near 100% (data not shown). Thus, HIF-VP16–expressing cells may be hypersensitive to glutamate because oxidative stress posttranslationally enhances the apoptotic activities of BH3-only proteins. Among these proteins, we focused our attention on the BNIP3 protein. Consistent with a prior report from our group and others on BNIP3 message (1, 24), DFO or HIF-VP16 increased BNIP3 protein expression, as monitored by immunofluorescence. As shown in Fig. 3A and B, in mouse hippocampal cells, both endogenous BNIP3 induced by stable HIF-VP16 protein and recombinant GFP-BNIP3 protein localized predominantly to mitochondria.

FIG. 2.

Forced expression of HIF-VP16 induces the expression of several prodeath BH3-only family genes. RT-PCR of BH3-only, prodeath proteins BNIP3, NIX, and PUMA. Lane 1, control HT22 cells infected with VP16; lane 2, HT22 cells infected with VP16 and treated with DFO; and lane 3, HT22 cells infected with HIF-VP16 and treated with DFO. β-Actin mRNA level (known not to change with hypoxia or hypoxia mimetics) was used as a loading control.

FIG. 3.

BNIP3 localization in mouse HTT hippocampal neuroblasts. (A) BNIP3 expression induced by HIF-VP16. (B) Cells co-transfected with plasmid expressed EGFP-BNIP3 fusion protein and pDsRed-mito. Nucleus is stained with DAPI.

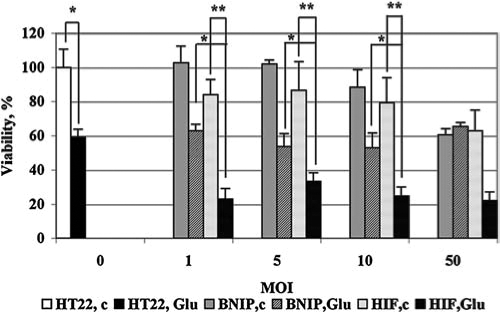

BNIP3 expression is not sufficient to induce death, nor is it sufficient to reproduce the increased sensitivity to oxidative death imposed by HIF-VP16 expression

To evaluate whether BNIP3 itself is sufficient to induce neuronal death, we used a range of multiplicities of infection (MOI, 1–50) to infect HT22 cells with retroviruses pBabe-puro VP16, pBabe-puro BNIP3, or pBabe-puro- HIF-1α-VP16. The viability of cells was analyzed by MTS assay 40 h after infection and 16 h after treatment with glutamate. At MOIs from 1 to 10, the control cells infected with the BNIP3-encoding virus showed no significant decrease in viability (Fig. 4). The viability of cells treated with glutamate was also at the same level as that in the BNIP3-noninfected cells. At the same MOI range, the cells expressing fusion protein HIF-VP16 were much more sensitive to the glutamate-induced toxicity (Fig. 4). From these experiments, we conclude that the increased sensitivity of HIF-VP16-expressing cells to glutamate is not the consequence of an increased expression of BNIP3 alone.

FIG. 4.

Enhanced sensitivity of HIF-VP16-expressing HT22 cells but not BNIP3-expressing HT22 cell to glutamate-induced oxidative stress. HT22 cells were plated onto a 96-well plate at the density of 5 × 104 cells/ml and infected with retroviruses expressing murine BNIP, VP16, or fusion protein HIF-VP16 at MOI from 1 to 50. Twenty-four hours after infection, cells were treated with 10 mM glutamate overnight. HT22, c, HT22 cells noninfected and nontreated; HT22, Glu-noninfected cells treated with glutamate; BNIP, c, cells infected with retrovirus expressing BNIP3, nontreated; BNIP, Glu, cells infected with retrovirus expressing BNIP3, treated with glutamate; HIF, c, cells infected with retrovirus expressing HIF-VP16, nontreated; HIF, Glu, cells infected with retrovirus expressing BNIP3, treated with glutamate. Data were normalized to the untreated and noninfected cells (100%). *p < 0.002. **p < 0.02.

BNIP3 expression is necessary for the potentiation of death by HIF-VP16

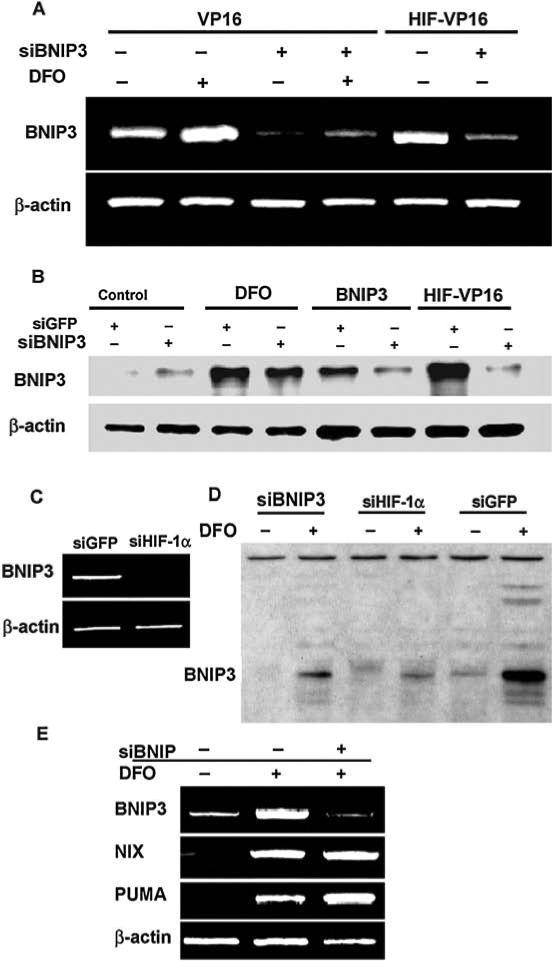

To examine whether BNIP3 is necessary for the potentiation of death by HIF-1α overexpression, we reduced BNIP3 expression by using shRNA. To reduce BNIP3 expression, we used a retrovirus to encode an shRNA sequence to BNIP3 in the hippocampal HT22 neuroblast genome. As a control, shRNA against the GFP was used. To confirm the functionality of these constructs, HT22 cells were first infected with pBabe-puro-VP16 and pBabe-puro-HIF-VP16 at MOI of 10. At this MOI, the transduction efficiency was nearly 100%. After selection with puromycin, cells were infected with pSuperRetro-shBNIP3 or pSuperRetro-shGFP. Six days later, cells were plated onto a 100-mm dish at the density of 5 × 104 cells/ml. As a control, the BNIP3 expression was induced by overnight treatment with 100 μM DFO, a concentration that we previously established to induce HIF and HIF target genes. Total RNA from these cells was used in semiquantitative RT-PCR. The low basal level of BNIP3 expression was detected in nontreated cells as well as in cells not transformed with pBabe-puro-HIF-VP16 (Fig. 5A). The effect of treatment with DFO or the expression of the HIF-VP16 fusion was similar and led to a significant increase in the level of BNIP3 mRNA (Fig. 5A). Expression of shRNA against BNIP3 resulted in suppression of BNIP3 mRNA induction by DFO or HIF-VP16 (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Downregulation of BNIP3 expression by shRNA in mouse HT22 cells. (A) BNIP3 mRNA level in cells infected with the viral construct encoding shRNA against BNIP3. BNIP3 message was induced by 100 μM DFO or by infection with an HIF-VP16-encoding virus. (B) BNIP3 protein level as determined by immunoblot. (C) BNIP3 mRNA level in cells infected with viral construct encoding shRNA against GFP or HIF-1α and treated with 100 μM DFO overnight. (D) BNIP3 protein expression in cells infected with retrovirus encoding shRNA against BNIP3, HIF-1α, or GFP, treated (+) or nontreated (-) with DFO. (E) BH-3–only protein mRNA level in cells infected with VP16 alone (lane 1), treated with 100 μM DFO (lane 2), or infected with VP16 and virus-encoded shRNA against BNIP3 and treated with DFO (lane 3). β-Actin is used as a housekeeping gene.

Downregulation of BNIP3 at the protein level by shRNA against BNIP3 was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 5B). In this case, cells were infected with pSuperRetro shBNIP3 or pSuperRetro-shGFP alone or in combination with pBabe-puro-BNIP3 or pBabe-puro-HIF-VP16. For BNIP3 induction, cells also were treated with DFO overnight. Cell lysate containing 5 μg of total protein was used for SDS-PAGE separation. When probing with the BNIP3-specific antibody, BNIP3 protein from HT22 cells is detected as a protein band of ~30 kDa. No BNIP3 expression was detected in control cells, but the protein level dramatically increased after the treatment with DFO or expression of the HIF-VP16 fusion protein (Fig. 5B). As a positive control, cells infected with pBabe-puro-BNIP3 were used (Fig. 5B). For some reason, shB-NIP3 expression was not able completely to reduce the protein expression in cells treated with DFO (∼50% reduction). In contrast, downregulation of HIF-1α significantly blocked BNIP3 induction after DFO treatment in both RNA (Fig. 5C) and protein (Fig. 5D) levels. However, in the case of induction by HIF-VP16 fusion protein and by direct expression of BNIP3, the level of BNIP3 protein was substantially reduced in cells with shRNA against BNIP3 expression (Fig. 5B). To confirm the specificity of this effect, total RNAs from the cells infected with pBabe-puro-VP16, nontreated or treated with DFO, as well as the cells infected with pBabe-puro-VP16 and pSuperRetro-shBNIP3 and treated with DFO, were analyzed with semiquantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 5E). The level of BNIP3 mRNA in the case of shBNIP3 expression is comparable with the control, whereas the level of mRNA of two other BH3-only proteins, NIX and PUMA, was not altered.

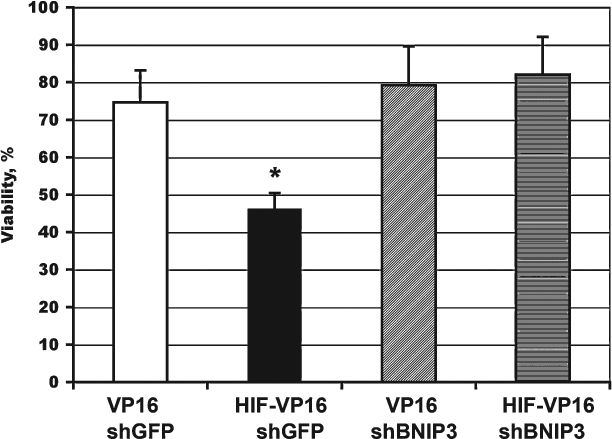

These experiments establish our ability to reduce selectively the expression of the BNIP3 but not functionally related proteins NIX or PUMA in response to HIF activation in HT22 hippocampal neuroblasts. We then examined the viability of cells expressing stabilized HIF-1α and siBNIP3 or shGFP under the condition of oxidative stress imposed by glutamate. Downregulation of BNIP3 expression restored the viability of HIF-VP16–expressing cells to the control levels, whereas shGFP had no effect on BNIP3 or viability (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Effect of BNIP3 downregulation on cell death induced by glutathione depletion. HT22 cells were plated at the density of 5 × 104 cells/ml onto a 96-well plate, incubated overnight, and infected with retroviruses encoding VP16 or HIF-VP16 in combination with virus encoding shRNA against BNIP3 or GFP (MOI 5 for each virus). Twelve hours after infection, cells were treated with 5 mM glutamate. The viability of cells was measured 12 h after treatment. Data are normalized relative to the untreated cells (100%). *p < 0.002.

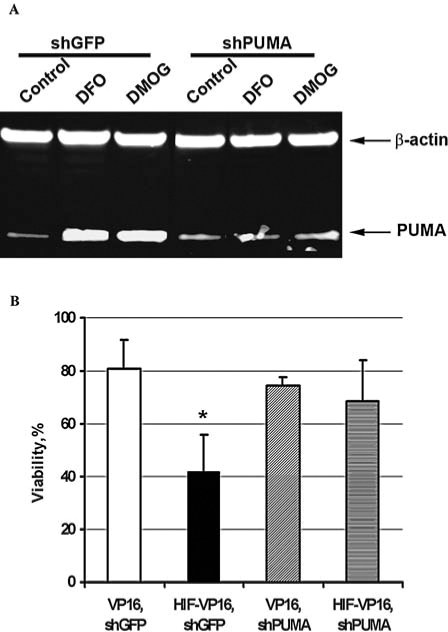

Downregulation of PUMA by shRNA has the same effect as BNIP3 downregulation on HT22

Recent investigations showed that PUMA also plays an important role in neuronal apoptosis, which is induced by oxidative or ER stress (12, 23). In addition to BNIP3, HIF-VP16 also induces PUMA. To establish the role of PUMA in cell-death potentiation by HIF-1, we reduced PUMA expression by shRNA. First, we infected HT22 cells with retro-viruses expressing shPUMA or shGFP and induced PUMA expression with DFO or DMOG. Western blot analysis indicated a significant increase of PUMA protein level after induction when cells were infected by the virus carrying shGFP. At the same time, in cells infected with shPUMA, the level of PUMA protein was comparable with that of the non-induced control (Fig. 7A).

FIG. 7.

Downregulation of PUMA expression by shRNA in mouse HT22 cells and its effect on cell viability under oxidative stress. (A) PUMA protein expression in cells infected with retrovirus encoding shRNA against GFP or PUMA, nontreated control, or treated with DFO or DMOG. (B) HT22 cells were plated at the density of 5 × 104 cells/ml onto a 96-well plate, incubated overnight, and infected with retroviruses encoding VP16 or HIF-VP16 in combination with virus encoding shRNA against PUMA or GFP (MOI 5 for each virus). Twelve hours after infection, cells were treated with 10 mM HCA. The viability of cells was measured 12 h after treatment. Data are normalized relative to the untreated cells (100%). *p < 0.0001.

Next we analyzed the viability of cells under oxidative stress induced by 10 mM HCA. As shown in Fig. 7, B cells infected with retrovirus encoding shPUMA together with retrovirus encoding HIF-VP16 or VP16 only have the same viability as control cells infected with retrovirus encoding VP16 and shGFP. When cells were infected with the virus expressing HIF-VP16 and shGFP, they had significantly lower viability (Fig. 7B).

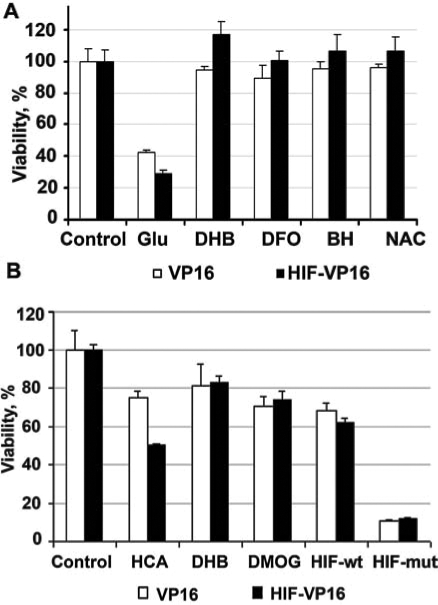

Antioxidants prevent the prodeath effects of HIF-1α overexpression

Prior studies suggested that secondary state changes such as acidosis are critical in “activating” BNIP3 to trigger cell death. We therefore considered the possibility that oxidative stress could directly or indirectly induce a physiologic state that makes BNIP3 “competent” to induce cell death. To test this hypothesis, we evaluated whether two structurally distinct antioxidants (N-acetylcysteine, butylated hydroxyanisole) could abrogate the ability of glutamate or its analogues to potentiate death by HIF-1α-driven BNIP3. Consistent with previous observations, both of these compounds effectively protected the cells from glutamate-induced toxicity. Moreover, both agents prevented potentiation of glutamate-induced death by HIF-VP16 overexpression (Fig. 8A). Future studies will determine whether antioxidants abrogate the prodeath effects of HIF-1α by reducing BNIP3 levels or by preventing a conformational change in the BNIP3 protein. It is unlikely that antioxidants alter levels of HIF-VP16, as others have shown (17).

FIG. 8.

Effects of antioxidants, low-molecular-weight HIF PHD inhibitors, or peptide HIF PHD inhibitors on cell survival in the presence of 10 m M glutamate. Cells with the stable expression of the fusion protein HIF-VP16 or of VP16 only as a control were plated onto a 96-well plate at the density of 5 × 104 cells/ml for HIF-VP16 expression or at 2.5 × 104 cells/ml for VP16 expression. (A) Twenty-four hours after the plating, cells were treated with either 10 mM glutamate, 10 μM DFO, 10 μM BH, or 100 μM NAC or a combination of glutamate with one of these compounds; these compounds are known to be effective in deterring the glutamate-induced toxicity. (B) Cells were treated with either HCA, DHB, DMOG, short HIF ODD wild-type peptide (HIF-wt), or mutated (HIF-mut). Data are normalized relative to the untreated cells (100%). Values between VP16 and HIF-VP16 infected and treated with glutamate or HCA, p < 0.001.

Low-molecular-weight or peptide inhibitors of the HIF prolyl 4 hydroxylases prevent the prodeath effects of HIF-VP16 overexpression

Prior studies from our group showed that low-molecular-weight and peptide inhibitors of the HIF prolyl hydroxylases (HIF-PHDs) prevent oxidative death in vitro or ischemic death in vivo (22). Two low-molecular-weight prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors, DHB and DMOG, significantly increased cell survival in both VP16 and HIF-VP16-expressing neuroblasts (Fig. 8B). To verify that DHB and DMOG are acting via the HIF-PHDs and not via an “off-target” effect, we used a more-specific peptide inhibitor of the HIF-PHDs. This peptide inhibitor contains 19 amino acids surrounding the C-terminal oxygen-dependent domain of HIF-1α. The remaining 11 amino acids derive from the membrane transduction domain of the protein, Tat. We previously verified that a peptide representing a fusion of the HIF ODD and the Tat transduction domain can spontaneously enter neurons in culture, can stabilize HIF-1α, increase activation of HIF target genes, and protect neurons from oxidative death. A mutant peptide that differs only in two critical prolines (ODD mut), can also enter cells, but fails to stabilize HIF and protect neurons (22). We examined the effect of the wild-type PHD inhibitor peptide and its nonactive mutant in HT22 cells expressing VP16 alone of HIF-VP16. As expected from our DHB and DMOG results, the wild-type but not mutant prevented the prodeath effects of HIF-VP16 overexpression (Fig. 8B). Together these findings indicate that antioxidants or PHD inhibitors can abrogate the prodeath effects of HIF-1α overexpression.

Discussion

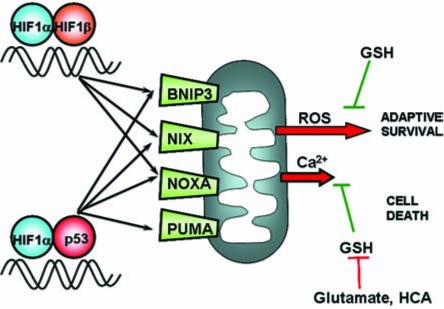

Stress-responsive transcription factors such as HIF-1 possess the remarkable ability to activate a large number of genes whose biological effect is to enhance survival. “Adaptive” transcription factors such as HIF-1 also possess the somewhat paradoxical ability to induce genes that execute death or autophagy. The Janus faces of HIF-1 and other stress-responsive transcription factors represent another piece of evidence that suggests that death of a single cell can be adaptive to a whole organism. Nonetheless, a high priority for experimental therapeutics is the identification of strategies that optimize the ability of transcription factors to mediate survival of an organism in the absence of death of individual cells. Such strategies are particularly important for organs such as the brain that harbor billions of postmitotic cells critical to the function of the organ. These postmitotic cells can be replaced only via evolving but as yet undefined strategies such as endogenous proliferation of a subset of neuroblasts. We identified several molecular and pharmacological strategies for minimizing the prodeath effects of forced expression of the hypoxia-sensitive transcription factor, HIF-1α, in immortalized cortical neuroblasts. We demonstrate that a biochemical imbalance between HIF-1α and HIF-1β is unlikely to explain the prodeath effects of HIF-1α overexpression. Rather, HIF-VP16 is stable under normoxic conditions; it then partners with HIF-1β and transactivates a host of genes capable of mediating neuronal death, including BNIP3, NIX, NOXA, and PUMA (1) (Fig. 9). Although BNIP3 is not sufficient to mediate death, it is necessary for potentiation of oxidative death by forced expression of HIF-VP16. BNIP3 localization to mitochondria in HT22 mouse neuroblasts occurs in the absence of oxidative stress, but its ability to participate in death appears to require oxidants and prolyl hydroxylase. Indeed, antioxidants or prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors abrogate the potentiation of death by HIF-VP16. Our results do not distinguish whether oxidants potentiate neuronal death directly by posttranslationally modifying BNIP3, NOXA, NIX, and/or PUMA; directly by stimulating the ability of another protein to partner with HIF-1 to increase BNIP3, NOXA, NIX, or PUMA expression; or indirectly by inducing a cellular state change (e.g., acidosis) known to activate BNIP3. We intend to address these distinct possibilities in future studies.

FIG. 9.

Model of HIF-1–induced activation of BH3-only Bcl2 family members. At least two models exist for HIF-1α transcriptional participation to promote cell death. One model proposes that an imbalance of HIF-1α and HIF-1β results in the dimerization of HIF-1α with p53, leading to stabilization of p53 and upregulation of its known prodeath genes, such as PUMA, NOXA, NIX, and BNIP3. The results herein do not support this model. A second model supported by the data herein is that HIF-1α and HIF-1β dimerize and regulate the expression of prodeath (and prosurvival) genes in living neurons. These neurons are triggered to commit death only when a secondary stress such as oxidative stress (or acidosis) is imposed on the cell. Such a secondary stress could induce death directly by modifying BNIP3 or indirectly by inducing the expression of an additional prodeath protein (PUMA).

Recent in vivo studies have suggested a role for BNIP3 in aberrant ventricular remodeling after cardiac ischemia, with an effect on early or late infarct size. BNIP3-null mice have reduced apoptotic cell death 2 days and 3 weeks after ischemia/reperfusion (6). Reduction in apoptotic death after cardiac ischemia culminates in preserved left ventricular performance, diminished left ventricular dilation, and decreased ventricular sphericalization (6). A prodeath role also has been attributed to BNIP3 after focal cerebral ischemia. Increased levels of BNIP3 localized to mitochondria have been shown in neurons 48 to 72 h after ischemia, but not at earlier time points (0, 12, 24 h) (31). These studies, in conjunction with the data herein, are consistent with the notion that BNIP3 is transcriptionally induced after hypoxia/ischemia, and as such, it is poised to execute neuronal death. In those cells in which oxidative stress becomes extant, cell death ensues. However, recent exciting data suggest that the transcriptional regulation of BNIP3 is far more interesting and complex than previously considered. Moreover, a more definitive statement regarding the role of BNIP3 in vivo after stroke requires further study. Recent data from several groups suggest that BNIP3 is induced early as part of the cascade of adaptive changes to hypoxia to induce mitochondrial autophagy. In this scheme, mitochondrial autophagy facilitates the transition of the cell to anaerobic glycolysis and removes free radical–generating mitochondria from the cellular organellar lineup (24, 30).

The finding in the current study that small molecule or peptide inhibitors of the HIF prolyl 4 hydroxylases abrogate the ability of HIF-VP16 to potentiate death provides a model to reconcile prior, apparently paradoxic findings. Specifically, we previously showed that inhibitors of the HIF PHDS stabilize HIF-1α and protect neurons from oxidative cell death (22). By contrast, forced overexpression of HIF-1α potentiates oxidative death (1). The ability of inhibitors of the HIF PHDs to abrogate the prodeath effects of HIF-1α suggests that PHD inhibition must modify other proteins in addition to or exclusive of HIF-1α that divert this transcription factor or its gene targets away from its prodeath functions. The findings have therapeutic importance, as they suggest that low-molecular-weight inhibitors of the HIF PHDs are better for preventing neuronal death in acute or chronic neurodegenerations as compared with gene therapy involving oxygen stabilized forms of HIF-1α. We are currently developing small-molecule inhibitors of the HIF PHDs that are optimal for neuroprotection (22). We anticipate that small-molecule or peptide inhibitors of HIF PHDs (HPHi) will be superior to antioxidants (e.g., N-acetylcysteine or butylated hydroxyanisole) that also abrogate the prodeath effects of HIF-1α because of the greater potential specificity of HPHi. FDA-approved HPHi may be available for human clinical testing in short order.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by New York State Department of Health Center of Research Excellence in Spinal Cord Injury (CO19772), Adelson Foundation, NIH RO1 (NS 40591, NS 46239, and NS37060).

Abbreviations

ARNT, aryl hydrocarbon nuclear translocator; BH, butylated hydroxyanisole; DFO, deferoxamine mesylate; DMOG, dimethyloxylglycine; Glu, l-glutamic acid; HCA, homocysteic acid; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; HPHi, HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; ODD, oxygen-dependent degradation domain; PHDs, prolyl-4-hydroxylases.

References

- 1.Aminova LR. Chavez JC. Lee J. Ryu H. Kung A. Lamanna JC. Ratan RR. Prosurvival, prodeath effects of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha stabilization in a murine hippocampal cell line. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3996–4003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409223200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruick RK. Expression of the gene encoding the proapoptotic Nip3 protein is induced by hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9082–9087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen D. Li M. Luo J. Gu W. Direct interactions between HIF-1 alpha and Mdm2 modulate p53 function. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13595–13598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conkright MD. Guzman E. Flechner L. Su AI. Hogenesch JB. Montminy M. Genome-wide analysis of CREB target genes reveals a core promoter requirement for cAMP responsiveness. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1101–1108. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cregan SP. Arbour NAK. Maclaurin JG. Callaghan SM. Fortin A. Cheung EC. Guberman DS. Park DS. Slack RS. p53 Activation domain 1 is essential for PUMA upregulation and p53-mediated neuronal cell death. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10003–10012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2114-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diwan A. Krenz M. Syed FM. Wansapura JR. Koesters AG. Li AG. Kirshenbaum H. Robbins J. Jones K. Dorn GW. Inhibition of ischemic cardiomyocyte apoptosis through targeted ablation of Bnip3 restrains postinfarction remodeling in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2825–2828. doi: 10.1172/JCI32490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang LE. Arany Z. Livingston M. Dunn HF. Activation of hypoxia-inducible transcription factor depends primarily upon redox-sensitive stabilization of its alpha subunit. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2253–2253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang LE. Gu J. Schau P. Bunn HF. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha is mediated by an O2-dependent degradation domain via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:987–999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.7987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivan M. Kondo K. Yang H. Kim W. Valiando J. Ohh M. Salic A. Asara JM. Lane WS. Kaelin WG., Jr HIFalpha targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science. 2001;292:464–468. doi: 10.1126/science.1059817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaakkola P. Mole DR. Tian YM. Wilson MI. Gielbert J. Gaskell SJ. Kriegsheim A. Hebestreit HF. Mukherji M. Schofield CJ. Maxwell PH. Pugh CW. Ratcliffe PJ. Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science. 2001;292:468–472. doi: 10.1126/science.1059796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kallio PJ. Wilson WJ. O'Brien S. Makino Y. Poellinger L. Regulation of the hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1alpha by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6519–6525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kieran D. Woods I. Villunger A. Strasser A. Prehn JH. Deletion of the BH3-only protein puma protects motoneurons from ER stress-induced apoptosis and delays motoneuron loss in ALS mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20606–20611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707906105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JY. Ahn HJ. Ryu JH. Suk K. Park JH. BH3-only protein noxa is a mediator of hypoxic cell death induced by hypoxia-inducible factor 1{alpha} J Exp Med. 2004;199:113–124. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubasiak LA. Hernandez OM. Bishopric NH. Webster KA. Hypoxia and acidosis activate cardiac myocyte death through the Bcl-2 family protein BNIP3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12825–12830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202474099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsushita N. Sogawa K. Ema M. Yoshida A. Fujii-Kuriyama Y. A factor binding to the xenobiotic responsive element (XRE) of P-4501A1 gene consists of at least two helix-loop-helix proteins, Ah receptor and Arnt. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21002–21006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mimura J. Fujii-Kuriyama Y. Functional role of AhR in the expression of toxic effects by TCDD. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1619:263–268. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00485-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishi K. Oda T. Takabuchi S. Oda S. Fukuda K. Adachi T. Semenza GL. Shingu K. Hirota K. LPS induces hypoxia-inducible factor 1 activation in macrophage-differentiated cells in a reactive oxygen species-dependent manner. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:983–995. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Regula KM. Ens K. Kirshenbaum LA. Inducible expression of BNIP3 provokes mitochondrial defects and hypoxia-mediated cell death of ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2002;91:226–231. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000029232.42227.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salceda S. Caro J. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) protein is rapidly degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system under normoxic conditions: its stabilization by hypoxia depends on redox-induced changes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22642–22647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt-Kastner R. Aguirre-Chen C. Kietzmann T. Saul I. Busto R. Ginsberg MD. Nuclear localization of the hypoxia-regulated pro-apoptotic protein BNIP3 after global brain ischemia in the rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2004;1001:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Semenza GL. Roth PH. Fang HM. Wang GL. Transcriptional regulation of genes encoding glycolytic enzymes by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23757–23763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siddiq A. Ayoub IA. Chavez JC. Aminova L. Shah S. LaManna JC. Patton SM. Connor JR. Cherny RA. Volitakis I. Bush AI. Langsetmo I. Seeley T. Gunzler V. Ratan RR. Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl 4-hydroxylase inhibition: a target for neuroprotection in the central nervous system. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41732–41743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504963200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steckley D. Karajgikar M. Dale LB. Fuerth B. Swan P. Drummond-Main C. Poulter MO. Ferguson SS. Strasser A. Cregan SP. Puma is a dominant regulator of oxidative stress induced Bax activation and neuronal apoptosis. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12989–12999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3400-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tracy K. Dibling BC. Spike BT. Knabb JR. Schumacker P. Macleod KF. BNIP3 is an RB/E2F target gene required for hypoxia-induced autophagy. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6229–6242. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02246-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vande Velde C. Cizeau J. Dubik D. Alimonti J. Brown T. Israels S. Hakem R. Greenberg AH. BNIP3 and genetic control of necrosis-like cell death through the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5454–5468. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.15.5454-5468.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Webster KA. Hypoxia: life on the edge. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:1303–1307. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Webster KA. Graham RM. Thompson JW. Spiga MG. Frazier DP. Wilson A. Bishopric NH. Redox stress and the contributions of BH3-only proteins to infarction. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1667–1676. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu J. Zhang L. Hwang PM. Kinzler KW. Vogelstein B. PUMA induces the rapid apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2001;7:673–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaman K. Ryu H. Hall D. O'Donovan K. Lin KI. Miller MP. Marquis JC. Baraban JM. Semenza GL. Ratan RR. Protection from oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in cortical neuronal cultures by iron chelators is associated with enhanced DNA binding of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and ATF-1/CREB and increased expression of glycolytic enzymes, p21(waf1/cip1), and erythropoietin. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9821–9830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-22-09821.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang H. Bosch-Marce M. Shimoda LA. Tan YS. Baek JH. Wesley JB. Gonzalez FJ. Semenza GL. Mitochondrial autophagy is an HIF-1-dependent adaptive metabolic response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10892–10903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800102200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Zhang Z. Yang X. Zhang S. Ma X. Kong J. BNIP3 upregulation and EndoG translocation in delayed neuronal death in stroke and in hypoxia. Stroke. 2007;38:1606–1613. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.475129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]