Abstract

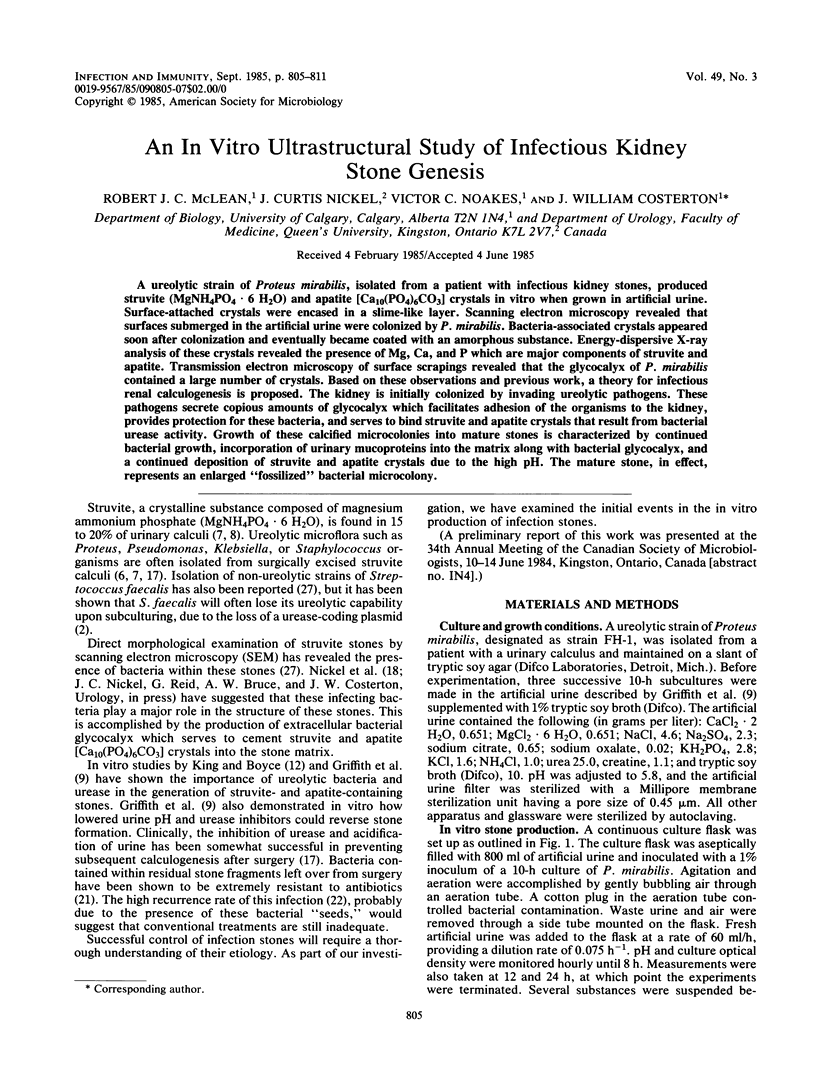

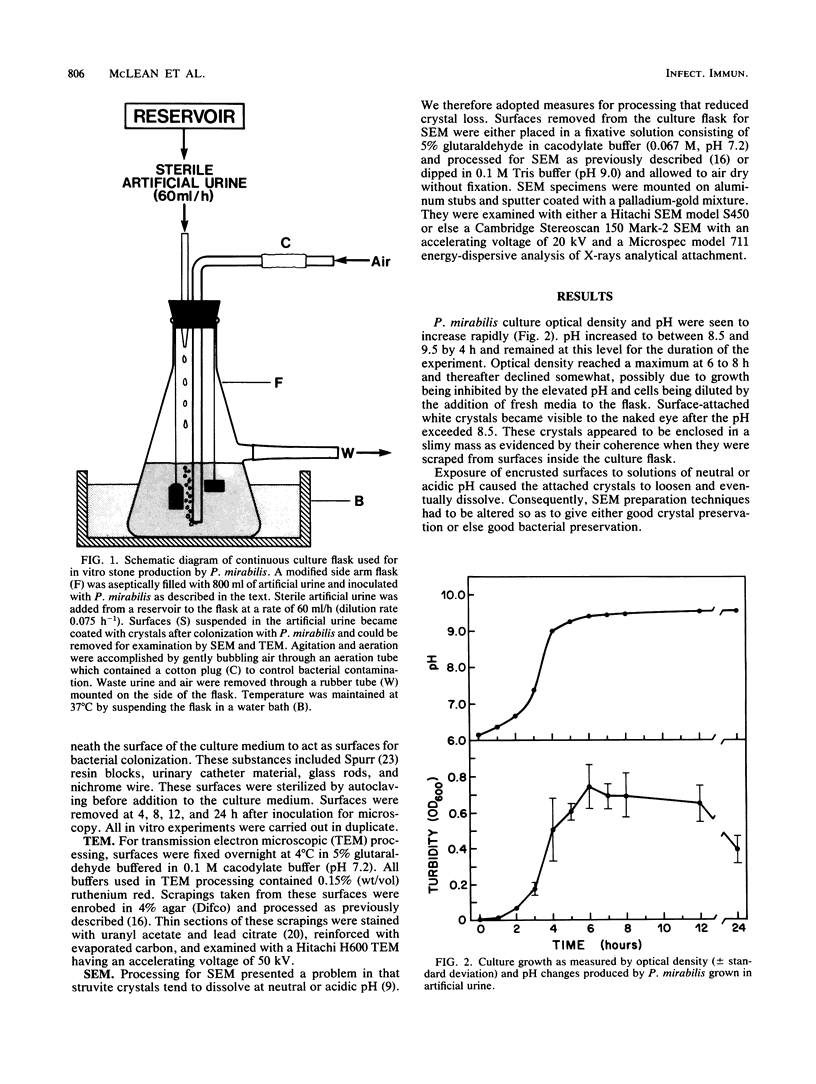

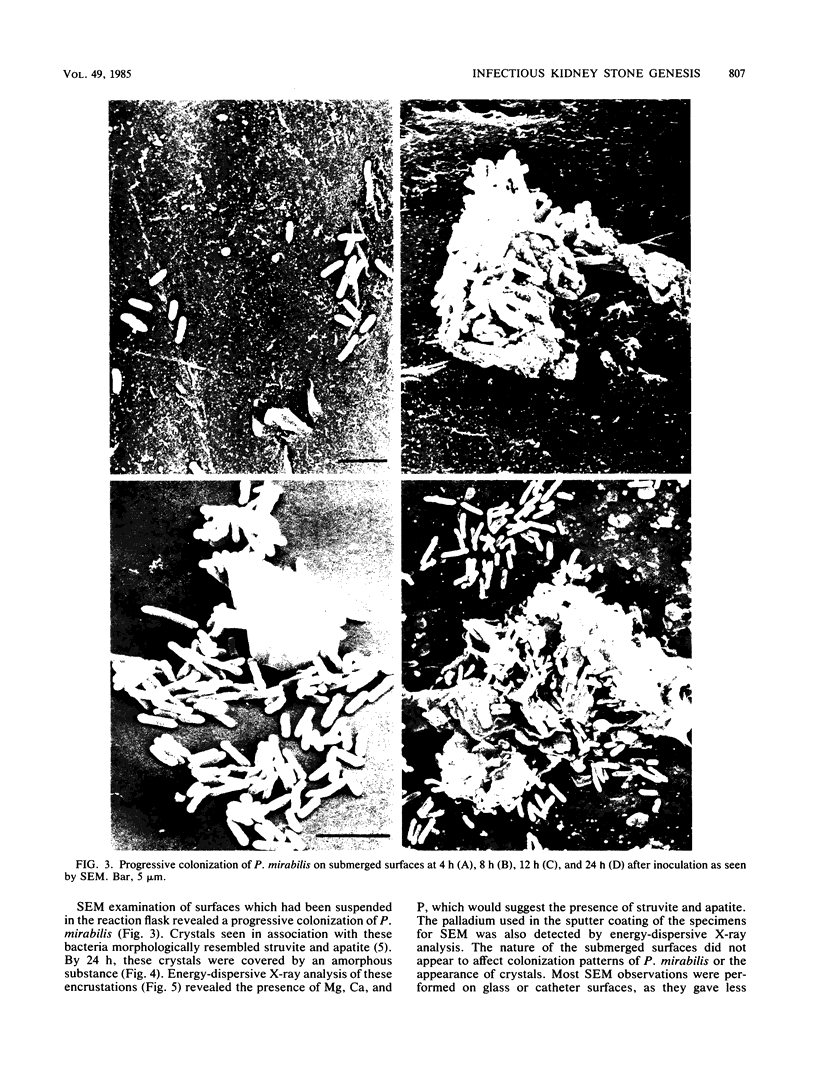

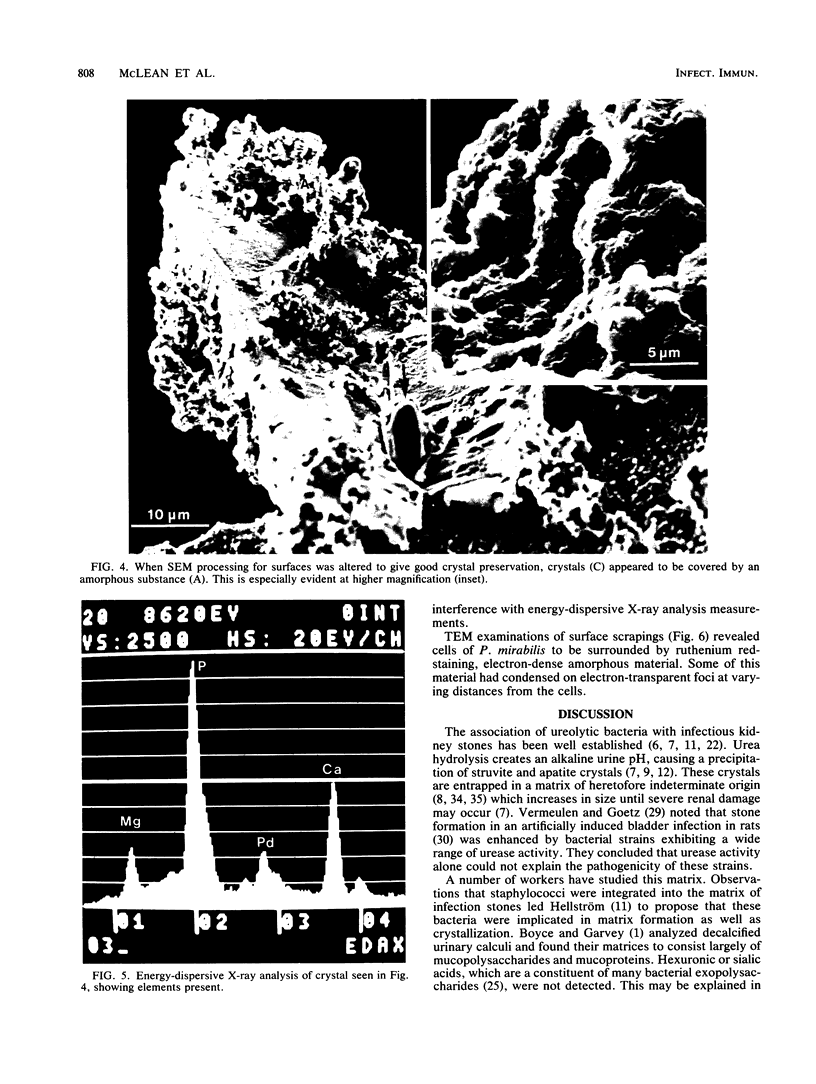

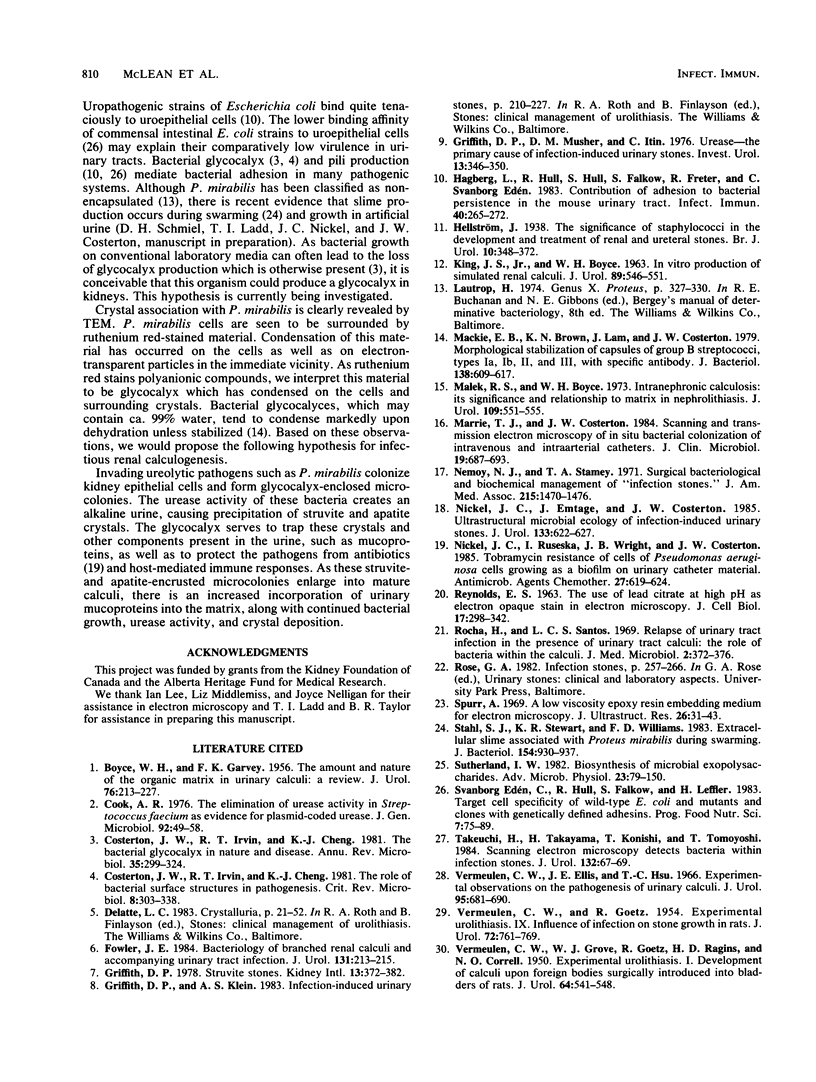

A ureolytic strain of Proteus mirabilis, isolated from a patient with infectious kidney stones, produced struvite (MgNH4PO4 X 6 H2O) and apatite [Ca10(PO4)6CO3] crystals in vitro when grown in artificial urine. Surface-attached crystals were encased in a slime-like layer. Scanning electron microscopy revealed that surfaces submerged in the artificial urine were colonized by P. mirabilis. Bacteria-associated crystals appeared soon after colonization and eventually became coated with an amorphous substance. Energy-dispersive X-ray analysis of these crystals revealed the presence of Mg, Ca, and P which are major components of struvite and apatite. Transmission electron microscopy of surface scrapings revealed that the glycocalyx of P. mirabilis contained a large number of crystals. Based on these observations and previous work, a theory for infectious renal calculogenesis is proposed. The kidney is initially colonized by invading ureolytic pathogens. These pathogens secrete copious amounts of glycocalyx which facilitates adhesion of the organisms to the kidney, provides protection for these bacteria, and serves to bind struvite and apatite crystals that result from bacterial urease activity. Growth of these calcified microcolonies into mature stones is characterized by continued bacterial growth, incorporation of urinary mucoproteins into the matrix along with bacterial glycocalyx, and a continued deposition of struvite and apatite crystals due to the high pH. The mature stone, in effect, represents an enlarged "fossilized" bacterial microcolony.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BOYCE W. H., GARVEY F. K. The amount and nature of the organic matrix in urinary calculi: a review. J Urol. 1956 Sep;76(3):213–227. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)66686-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A. R. The elimination of urease activity in Streptococcus faecium as evidence for plasmid-coded urease. J Gen Microbiol. 1976 Jan;92(1):49–58. doi: 10.1099/00221287-92-1-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerton J. W., Irvin R. T., Cheng K. J. The bacterial glycocalyx in nature and disease. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1981;35:299–324. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.35.100181.001503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerton J. W., Irvin R. T., Cheng K. J. The role of bacterial surface structures in pathogenesis. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1981;8(4):303–338. doi: 10.3109/10408418109085082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler J. E., Jr Bacteriology of branched renal calculi and accompanying urinary tract infection. J Urol. 1984 Feb;131(2):213–215. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)50311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. P., Musher D. M., Itin C. Urease. The primary cause of infection-induced urinary stones. Invest Urol. 1976 Mar;13(5):346–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. P. Struvite stones. Kidney Int. 1978 May;13(5):372–382. doi: 10.1038/ki.1978.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg L., Hull R., Hull S., Falkow S., Freter R., Svanborg Edén C. Contribution of adhesion to bacterial persistence in the mouse urinary tract. Infect Immun. 1983 Apr;40(1):265–272. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.1.265-272.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KING J. S., Jr, BOYCE W. H. In vitro production of simulated renal calculi. J Urol. 1963 Apr;89:546–551. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)64591-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie E. B., Brown K. N., Lam J., Costerton J. W. Morphological stabilization of capsules of group B streptococci, types Ia, Ib, II, and III, with specific antibody. J Bacteriol. 1979 May;138(2):609–617. doi: 10.1128/jb.138.2.609-617.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek R. S., Boyce W. H. Intranephronic calculosis: its significance and relationship to matrix in nephrolithiasis. J Urol. 1973 Apr;109(4):551–555. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)60477-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrie T. J., Costerton J. W. Scanning and transmission electron microscopy of in situ bacterial colonization of intravenous and intraarterial catheters. J Clin Microbiol. 1984 May;19(5):687–693. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.5.687-693.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoy N. J., Staney T. A. Surgical, bacteriological, and biochemical management of "infection stones". JAMA. 1971 Mar 1;215(9):1470–1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel J. C., Emtage J., Costerton J. W. Ultrastructural microbial ecology of infection-induced urinary stones. J Urol. 1985 Apr;133(4):622–627. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel J. C., Ruseska I., Wright J. B., Costerton J. W. Tobramycin resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells growing as a biofilm on urinary catheter material. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985 Apr;27(4):619–624. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha H., Santos L. C. Relapse of urinary tract infection in the presence of urinary tract calculi: the role of bacteria within the calculi. J Med Microbiol. 1969 Aug;2(3):372–376. doi: 10.1099/00222615-2-3-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurr A. R. A low-viscosity epoxy resin embedding medium for electron microscopy. J Ultrastruct Res. 1969 Jan;26(1):31–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(69)90033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl S. J., Stewart K. R., Williams F. D. Extracellular slime associated with Proteus mirabilis during swarming. J Bacteriol. 1983 May;154(2):930–937. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.2.930-937.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland I. W. Biosynthesis of microbial exopolysaccharides. Adv Microb Physiol. 1982;23:79–150. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svanborg Edén C., Hull R., Falkow S., Leffler H. Target cell specificity of wild-type E. coli and mutants and clones with genetically defined adhesins. Prog Food Nutr Sci. 1983;7(3-4):75–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi H., Takayama H., Konishi T., Tomoyoshi T. Scanning electron microscopy detects bacteria within infection stones. J Urol. 1984 Jul;132(1):67–69. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49466-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERMEULEN C. W., GOETZ R. Experimental urolithiasis. IX. Influence of infection on stone growth in rats. J Urol. 1954 Nov;72(5):761–769. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)67665-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERMEULEN C. W., GROVE W. J., GOETZ R., RAGINS H. D., CORRELL N. O. Experimental urolithiasis. I. Development of calculi upon foreign bodies surgically introduced into bladders of rats. J Urol. 1950 Oct;64(4):541–548. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)68674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERMEULEN C. W., LYON E. S., FRIED F. A. ON THE NATURE OF THE STONE-FORMING PROCESS. J Urol. 1965 Aug;94:176–186. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)63596-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERMEULEN C. W., LYON E. S., GILL W. B. ARTIFICIAL URINARY CONCRETIONS. Invest Urol. 1964 Jan;1:370–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen C. W., Ellis J. E., Hsu T. C. Experimental observations on the pathogenesis of urinary calculi. J Urol. 1966 May;95(5):681–690. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)63518-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen C. W., Lyon E. S. Mechanisms of genesis and growth of calculi. Am J Med. 1968 Nov;45(5):684–692. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(68)90204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham J. E. Matrix and the infective renal calculus. Br J Urol. 1975;47(7):727–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1975.tb04049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]