Abstract

Acute ethanol exposure affects the nervous system as a stimulant at low concentrations and as a depressant at higher concentrations, eventually resulting in motor dysfunction and uncoordination. A recent genetic study of two mouse strains with varying ethanol preference indicated a correlation with a polymorphism (D216N) in the synaptic protein Munc18-1. Munc18-1 functions in exocytosis via a number of discrete interactions with the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) protein syntaxin-1. We report that the mutation affects binding to syntaxin but not through either a closed conformation mode of interaction or through binding to the syntaxin N terminus. The D216N mutant instead has a specific impairment in binding the assembled SNARE complex. Furthermore, the mutation broadens the duration of single exocytotic events. Expression of the orthologous mutation (D214N) in the Caenorhabditis elegans UNC-18 null background generated transgenic rescues with phenotypically similar locomotion to worms rescued with the wild-type protein. Strikingly, D214N worms were strongly resistant to both stimulatory and sedative effects of acute ethanol. Analysis of an alternative Munc18-1 mutation (I133V) supported the link between reduced SNARE complex binding and ethanol resistance. We conclude that ethanol acts, at least partially, at the level of vesicle fusion and that its acute effects are ameliorated by point mutations in UNC-18.

INTRODUCTION

Synaptic transmission initially involves the fusion of vesicular and plasma membranes within the presynaptic terminal. Membrane-membrane fusion is driven by the formation of the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex, which is composed at the mammalian synapse of syntaxin-1, vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP)-2 and synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kD (SNAP-25) (Burgoyne and Morgan, 2003; Jahn and Scheller, 2006). Although SNARE proteins are regarded as the minimal machinery required for fusion (Weber et al., 1998), there exists a large degree of overlaying regulation by an abundance of interacting proteins. One such protein is Munc18-1, the mammalian homologue of the nSec-1/Munc18-1 (SM) protein family.

Originally isolated via genetic screens in Caenorhabditis elegans and yeast (Brenner, 1974; Novick and Schekman, 1979), SM proteins are essential exocytotic proteins primarily characterized via their strong interaction with syntaxin. The conserved function for SM proteins remains controversial and includes syntaxin trafficking (Medine et al., 2007; Arunachalam et al., 2008), vesicle recruitment and/or docking (Voets et al., 2001; Weimer et al., 2003), and the fusion process itself (Barclay et al., 2003; Shen et al., 2007). A consensus on SM protein function has been hampered in part due to a lack of consistency in the mechanism of its syntaxin interaction. Munc18-1 was originally described to bind syntaxin only when syntaxin adopted a closed conformation (referred to here as mode 1 binding) (Dulubova et al., 1999; Yang et al., 2000), consequently precluding further association of syntaxin with the other SNAREs and inhibiting fusion. Recent studies have demonstrated, however, that Munc18-1 binds syntaxin in at least two other conformations. Munc18-1 interacts with the N terminus of the syntaxin cytoplasmic domain (mode 2 binding) (Dulubova et al., 2007; Rickman et al., 2007), as described previously for other SM proteins Sly1p and VPS-45p (Bracher and Weissenhorn, 2002; Dulubova et al., 2002). Munc18-1 also binds directly to the assembled SNARE complex (mode 3 binding) (Zilly et al., 2006; Dulubova et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2007). Although a great deal is known about modes 1 and 2 binding through mutational and structural analysis, very little is known about mode 3 binding and there are no known mutations specifically affecting this mode of binding.

Acute exposure to ethanol has concentration-dependent effects on the nervous system, resulting in behavioral alterations. For most organisms, exposure to low concentrations of ethanol provokes an increase in motor activity, whereas high doses are sedative. Within the nervous system, the intoxicating effects of ethanol are both pre- and postsynaptic in origin, acting in GABAergic, glutamatergic, and peptidergic transmission (Siggins et al., 2005). Described molecular targets for the transduction of ethanol effects, however, remain limited. Ethanol directly activates the BK channel slo-1 in C. elegans, and gain-of-function mutants resemble intoxicated animals (Davies et al., 2003). Distinct RhoGAP18B isoforms are involved in hyperactivity and sedation in Drosophila (Rothenfluh et al., 2006), and the acute sensitivity of postsynaptic N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor currents to ethanol are altered in Eps8 knockouts (Offenhauser et al., 2006). In light of the correlation between the individual's level of response to the acute intoxicating effects of ethanol and an increased risk for alcoholism incidence (Schuckit et al., 2004), identification of the molecular determinants of ethanol is of potentially clinical importance.

A recent study comparing two mouse strains with differing ethanol preference in a two-bottle choice paradigm suggested that the phenotypic differences were correlated to a single amino acid polymorphism within Munc18-1 (Fehr et al., 2005). We investigated this polymorphism and determined whether the point mutation reduced the acute intoxicating effects of ethanol. We show that the mutation specifically decreased mode 3 binding of Munc18-1 to the assembled SNARE complex without any effects on modes 1/2 binding to syntaxin. Expression of the mutant protein in adrenal chromaffin cells lengthened the duration of single exocytotic events. Transgenic expression of the orthologous mutant (D214N) in the C. elegans unc-18 null background generated worms that were phenotypically similar to those rescued with the wild-type (W/t) protein. Direct comparison, however, demonstrated that the D214N transgenic worms were strongly resistant to the acute effects of ethanol both to elevate locomotion at low concentrations and to depress locomotion at high concentrations. This study is the first description of an ethanol resistance phenotype conferred at the level of the fusion machinery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid Construction and Recombinant Protein Production

For expression in mammalian cells, Munc18-1 was cloned into pcDNA3.1(−) and pFLAG-CMV-4 (Sigma Chemical. Poole, Dorset, United Kingdom). Munc18-1, syntaxin-1, complexin-II, and the Mint 1-Munc18 binding domain (MBD) were also cloned into pGEX-6p-1 for glutathione transferase (GST) fusion protein production. Recombinant proteins were produced as described previously (Archer et al., 2002; Graham et al., 2004; Ciufo et al., 2005). Point mutations (Munc18-1 D216N, Munc18-1 I133V, UNC-18 D214N, open syntaxin [L165A/E166A], and complexin-II R59H) were introduced using the QuikChange mutagenesis system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

Immunoprecipitation

PC12 cells were plated at a density of 0.75 × 106 cells/well of a 24-well plate coated with collagen and left overnight at 37°C. The following day, cells were transfected with 1 μg of either empty vector, W/t Munc18-1, or D216N Munc18-1 by using 3 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom). Each construct was transfected into duplicate wells. After 48-h incubation, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then lysed with 250 μl ice-cold lysis buffer (PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100, 5 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitor cocktail; Sigma Chemical). Lysates were transferred to microtubes and duplicates were pooled. Samples were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 3 min and the supernatant was removed. To preclear the lysate, 50 μl of True Blot anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig) immunoprecipitation (IP) beads (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA) were added to each sample (now 500 μl) and the incubation proceeded for 30 min at 4°C with mixing. The tubes were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 3 min, and the supernatant was removed. Five micrograms of anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (Sigma Chemical) was added to the precleared lysate which were incubated for 1 h at 4°C with mixing. Then, 50 μl of True Blot anti-mouse Ig IP beads was added to each lysate, and the incubations were continued for a further 1 h. The bead containing lysates were transferred to microfuge tube spin-filters (Sigma Chemical), and the beads were washed five times with lysis buffer. Bead-bound proteins were eluted with 100 μl of SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) buffer and boiled for 5 min. Proteins were subsequently separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose paper for immunoblotting with 1:5000 anti-syntaxin mAb (Sigma Chemical) and 1:1000 anti-Munc18-1 mAb (BD Biosciences, Oxford, United Kingdom). The secondary antibody was 1:1000 True Blue anti-mouse IgG (eBiosciences), which has reduced binding to SDS-denatured, reduced, heavy and light chains of the precipitating antibody.

Binding of Bovine Brain Proteins to Immobilized GST-Fusion Proteins

Extracts of bovine brain were prepared (Okamoto and Sudhof, 1997; Graham et al., 2008), and pull-down assays were performed (Graham et al., 2004; Graham et al., 2008) as described previously. Glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) were washed three times with PBS. Escherichia coli protein extract (150 mg) was incubated per milliliter of a 50% (vol/vol) slurry of beads in binding buffer (20 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.5% mM Triton X-100, pH 7.7) for 1 h at room temperature. Beads were then washed three times in binding buffer. All further incubations were carried out at 4°C with rotation. Recombinant GST or GST-tagged proteins were added to the beads to a final concentration of 2 μM in a total volume of 200 μl and incubated for 30 min. Bovine brain extract (200 μl) was added to the beads and incubated for 2 h. Beads were washed using CytoSignal spin filters (CytoSignal, Irvine, CA), with two initial washes in binding buffer with 1 mg/ml gelatin followed by three washes with binding buffer containing 5% (vol/vol) glycerol. Proteins were eluted with 100 μl of Laemmli buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min, followed by centrifugation. Eluted samples were diluted one fifth in Laemmli buffer, and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (12.5% gels) and transferred to nitrocellulose paper for immunoblotting. Antibodies used for immunoblotting: 1:10,000 monoclonal anti-Munc18-1 (BD Biosciences), 1:10,000 monoclonal anti-syntaxin-1 (Sigma Chemical), and 1:1000 polyclonal anti-VAMP II (a gift from Prof. M. Takahashi, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan).

Binding of 35S-Labeled In Vitro Transcription-Translation–derived Proteins to Immobilized GST-Fusion Proteins

Proteins were produced using the TNT T7 Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation system (Promega, Madison, WI) in the presence of ∼0.6 MBq of [35S]methionine (GE Healthcare) per reaction, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Plasmids encoding W/t and D216N Munc18-1 and granuphilin A were used as a template for production of 35S-labeled proteins. The full-length cytoplasmic domain (1-266) of mouse syntaxin 1A and a truncated (4-266) cytoplasmic domain of rat syntaxin proteins were made by first generating a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product containing a T7 promoter and adding the PCR enhancer supplied in the TNT T7 Quick Coupled kit. GST or GST-fusion proteins of Munc18-1, syntaxin-1 (cytoplasmic domain residues 4-266; gift from Dr. R Scheller, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) or MBD residues 226–314 (Ciufo et al., 2005) were bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads as described above. 35S-labeled in vitro transcription/translation products (5 μl) were added to 50 μl of packed beads in a final volume of 100 μl of binding buffer (150 mM potassium acetate, 20 mM HEPES, 1 mM MgCl2, and 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.4, for Munc18-1 products; 150 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 5% glycerol, 0.05% Tween 20, and 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, pH 7.5, for granuphilin A). Beads were incubated for 2 h at 4°C with rotation and washed five times with binding buffer. Proteins were eluted with 75 μl of Laemmli buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose paper. Radiolabeled bands were visualized by exposing the nitrocellulose to autoradiography film for 3–4 h.

Binding of 35S-Labeled In Vitro Transcription-Translation–derived Munc18-1 to the Assembled SNARE Complex

GST, GST-complexin II, or GST-complexin II R59H (Archer et al., 2002) were bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads as described above in the presence of binding buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, and 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.8). Bovine brain extract (200 μl) was added to 100 μl of packed beads and incubated at 4°C overnight with rotation to allow assembled SNARE complexes to bind to the immobilized protein. Beads were washed five times with binding buffer and 5 μl of radiolabeled TNT-derived Munc18-1 was added to the beads to a final volume of 200 μl with binding buffer and incubated for 2 h at 4°C with mixing. After 2-min microcentrifugation, 50 μl of supernatant was removed and added to an equal volume of Laemmli buffer. The beads were washed five times with binding buffer, and bound proteins were eluted with 100 μl of Laemmli buffer. Proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose paper. The nitrocellulose was exposed to autoradiography film for 3–4 h to visualize radiolabeled bands. The paper was subsequently used for immunoblotting using 1:1000 dilutions of the following antibodies: monoclonal anti-syntaxin 1A, monoclonal anti-SNAP-25 (BD Biosciences) and polyclonal anti-VAMP II.

Amperometric Recording and Analysis

Electrochemical recording was performed as described previously (Graham et al., 2000; Barclay et al., 2003). Briefly, freshly cultured adrenal chromaffin cells were plated onto nontissue culture-treated 10-cm Petri dishes and left overnight at 37°C. Nonattached cells were resuspended in growth medium at a density of 1 × 107 cells/ml. Plasmids encoding Munc18-1 (W/t or D216N) were mixed with an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) plasmid and added to the chromaffin cells at 20 μg/ml. Cells were then electroporated using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), immediately diluted to 1 × 106 cells/ml with fresh growth medium, and maintained in culture for 3–5 d. Cultured cells were incubated in bath buffer (139 mM potassium glutamate, 0.2 mM EGTA, 20 mM PIPES, 2 mM ATP, and 2 mM MgCl2, pH 6.6), and a 5-μm diameter carbon fiber electrode was positioned in direct contact with the target chromaffin cell. Exocytosis was stimulated by a pressure ejection of permeabilization/stimulation buffer (139 mM potassium glutamate, 30 mM PIPES, 5 mM EGTA, 2 mM ATP, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.02 mM digitonin, and 10 mM free calcium, pH 6.5) from a glass pipette on the opposite side of the cell. Amperometric responses were monitored with a VA-10 amplifier (NPI Electronic, Tamm, Germany) and saved to computer by Axoscope 8 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Individual experiments were conducted in parallel on control (untransfected) and transfected cells from the same cell batch in the same cell culture dishes. Recordings of control and transfected cells used the same carbon fiber to eliminate any potential effects of interfiber variability. Transfected cells were identified by EGFP expression. Previous studies have established a 95% rate of coexpression (Graham et al., 2002; Barclay et al., 2003). Amperometric data were exported from Axoscope and analyzed using Origin (Microcal Software, Northampton, MA). Spikes were selected for analysis, provided that the spike amplitude was >40 pA. This amplitude was selected so that analyses were confined to spikes arising immediately underneath the carbon fiber tip, as small amperometric events can reflect exocytotic events having originated from a site distant from the carbon fiber (Hafez et al., 2005). All data are shown as mean ± SE. Significance was tested with nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-tests.

Nematode Culture and Strains

C. elegans were cultured on nematode growth media (NGM) agar plates at 20°C with Escherichia coli OP50 as a food source, by using standard methods (Brenner, 1974). The strains used in this study were wild-type Bristol N2 and the mutations unc-18(e81) and unc-18 (md1401) (a gift from Prof. R. Hosono, Kanazawa University, Kanazawa, Japan).

Transformation of C. elegans

Germline transformation of unc-18(e81) worms with DNA was performed by microinjection (Mello et al., 1991). e81 worms were rescued with a construct carrying the unc-18 cDNA (either wild type or D214N) under the control of the unc-18 genomic flanking regions (gift from Dr. H. Kitayama, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan) (Gengyo-Ando et al., 1996). Rescued cDNA constructs (10 μg/μl) were coinjected with a reporter construct, sur-5::GFP (10 μg/μl), where indicated. Total injected DNA concentration was made up to 130 μg/μl for all injections with empty pcDNA3.1(−) vector. Successful rescue of the e81 allele was determined by restoration of phenotypically wild-type locomotion and green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence, where indicated.

Behavioral Assays

All assays were performed on young adult hermaphrodite animals from sparsely populated plates. Experiments were conducted in a temperature-controlled room at 20°C.

Locomotion Assays

Locomotion rate was quantified by counting thrashes or body bends over a 1-min period as described previously (Miller et al., 1999; Mitchell et al., 2007). A thrash or a body bend was defined as one complete sinusoidal movement from maximum to minimum amplitude and back again. For assaying thrashes in solution, young adult hermaphrodites were removed from NGM plates and placed in a Petri dish containing 200 μl of freshly made of Dent's solution (140 mM NaCl, 6 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, with bovine serum albumin at 0.1 mg ml−1). For assaying body bends on NGM plates, young adult hermaphrodites were removed to fresh unseeded plates before measuring. To correct for any time-dependent changes in locomotion rate, worm movement was measured after the same amount of time in ethanol (10-min exposure). To correct for any variation in environmental factors, the locomotion rates of individual transgenic worm lines (W/t and D214N) were alternately measured. For acute ethanol exposure, measurements of locomotion were made as a percentage of mean locomotion rate in 0 mM ethanol measured each day (at least 10 control worms per transgenic line). All data are expressed as mean ± SE. Significance was tested by Student's t test.

Aldicarb Assays

Acute sensitivity to aldicarb (1 mM; Sigma Chemical) was determined by measuring the time of paralysis onset after acute exposure to the drug (Lackner et al., 1999). For each experiment, 20–25 worms were moved to aldicarb plates and assessed for paralysis every 10 min after drug exposure by prodding with a thin tungsten wire. Where indicated, worms were pretreated with 2 μg/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate for 2 h followed by exposure to aldicarb in combination with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA). Experiments were performed at least three times.

RESULTS

Munc18-1–Syntaxin Binding (Modes 1 and 2)

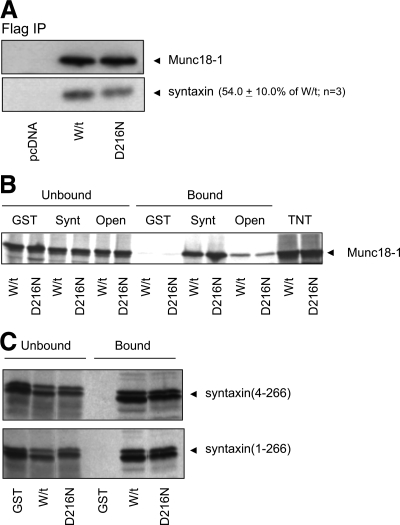

To investigate the effect of the polymorphism implicated in acute ethanol preference (Fehr et al., 2005), we first determined whether the D216N mutation affected binding to syntaxin. As an initial screen for effects on protein interactions, PC12 cells were transfected with either FLAG-tagged wild-type or D216N Munc18-1. After 2 d, the cells were lysed, and FLAG-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated. Blotting for the amount of bound syntaxin revealed a 46% decrease in syntaxin for the D216N precipitates compared with wild type in three separate experiments (Figure 1A). The decrease in D216N Munc18-1 was not due to differences in expression, as there were no differences in the amount of Munc18-1 in the precipitates (Figure 1A). Furthermore, immunofluorescence demonstrated that the extent and localization of expression of wild-type and mutant Munc18-1 were also similar (data not shown). Therefore, we concluded that there was a defect in binding between D216N Munc18-1 and syntaxin; however, these experiments did not indicate whether the binding defect was specific to any or all of the known modes of interaction (Burgoyne and Morgan, 2007).

Figure 1.

A decrease in Munc18-1 D216N and syntaxin interaction is not due to alterations in either binding to the closed conformation (mode 1) or to the N terminus (mode 2) of syntaxin. (A) PC-12 cells were transfected to express empty vector (pcDNA), wild-type (W/t) or mutant (D216N) Munc18-1. The Munc18-1 protein was immunoprecipitated and the amount of associated syntaxin was assessed by Western blotting. Despite equal levels of Munc18-1 recovered, there was a 46% reduction of bound syntaxin for the D216N mutant compared with W/t. (B) GST, GST-syntaxin (Synt) or GST-syntaxin L165A/E166A (Open) were incubated with radiolabeled W/t or D216N Munc18-1. Samples of the supernatant (Unbound) and bound proteins were detected by autoradiography. In a binary binding reaction to assess interaction with syntaxin, both W/t and D216N Munc18-1 bound equally well to GST-Synt in comparison with GST. Binding to the constitutively open syntaxin (Open) was also equal for W/t and D216N, although lower than seen for Synt. Protein input indicated by the TNT lanes. (C) The converse experiment was performed, where GST, GST-Munc18-1 W/t, and GST-Munc18-1 D216N were incubated with radiolabeled cytoplasmic domain of syntaxin, either amino acids 1-266 or 4-266. In a binary binding reaction to assess interaction, there was no difference in binding for W/t or D216N Munc18-1.

Munc18-1/syntaxin binding was originally described to occur as a 1:1 binary interaction only when syntaxin is in a closed conformation (mode 1) thereby precluding SNARE complex formation (Dulubova et al., 1999; Yang et al., 2000). We have previously investigated mutations that are thought to act by an inhibition of mode 1 binding (Fisher et al., 2001; Barclay et al., 2003; Ciufo et al., 2005). The second conformation of Munc18-1/syntaxin binding is also a 1:1 binary interaction (mode 2) with the extreme N terminus of an open conformation syntaxin (Dulubova et al., 2007; Rickman et al., 2007) as exists for other SM proteins (Bracher and Weissenhorn, 2002; Dulubova et al., 2002), although there seems to be some similarity between modes 1/2 binding (Khvotchev et al., 2007). Modes 1/2 binding were assessed here by producing wild-type and D216N Munc18-1 by an in vitro transcription/translation reaction and binding them to GST-syntaxin (cytoplasmic domain residues 4-266) in a binary protein reaction. Binding of Munc18-1 to this syntaxin construct is strongly inhibited by treatments or mutations that affect interaction with the closed conformation of syntaxin (Graham et al., 2004; Palmer et al., 2008), allowing its use in predominantly assaying mode 1 binding. This experiment uses ∼200 nM syntaxin but only 5 pM in vitro produced Munc18-1, which is far below the KD value for this interaction (Craig et al., 2004); thus, any reduction in binding affinity would be detectable in our binding assay.

Despite the reduction in binding in the immunoprecipitation experiment, however, there was no effect on mode 1 binding for D216N Munc18-1 in comparison with wild-type protein (Figure 1B). A lack of effect of the D216N mutation on binding to syntaxin was also apparent when the GST-syntaxin had been mutated (L165A/E166A) to make its conformation predominantly open (Dulubova et al., 1999; Graham et al., 2004). Although the extent of binding of the L165A/E166A syntaxin mutant is greatly reduced in comparison with wild-type syntaxin, there was again no difference in binding for the D216N mutant in comparison to wild-type Munc18-1 (Figure 1B). The GST–syntaxin construct in general use (Bennett et al., 1992) omits the first three amino acids of the syntaxin cytoplasmic domain. To verify that either this omission or the N-terminal GST-tag did not mask any binding defects and to ensure that mode 2 binding of Munc18-1 to the syntaxin N terminus would not be affected, the reciprocal experiment was performed in which in vitro-translated syntaxin (either 4-266 or 1-266) was bound to GST-Munc18-1 (wild type or D216N). As before, we saw no difference in binding for D216N versus wild-type protein (Figure 1C). These experiments demonstrated that despite a decrease in syntaxin binding for Munc18-1 D216N in PC12 cells there did not seem to be any defects for this mutation in either modes 1 or 2 binding. This indicated that the defect in binding could come from the final Munc18-1/syntaxin binding conformation, which is binding to the assembled SNARE complex (mode 3) (Zilly et al., 2006; Dulubova et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2007).

Munc18-1 D216N Specifically Inhibits Mode 3 Binding to the SNARE Complex

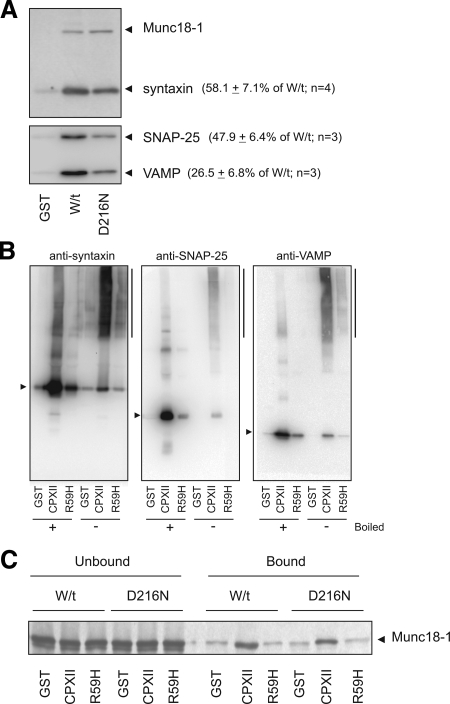

A specific effect on mode 3 binding was addressed in two ways. First, we reasoned that mode 3 binding is the only form of Munc18-1 binding to syntaxin that involves other SNARE proteins. For the D216N mutation to inhibit mode 3 binding, the amount of the other SNAREs (i.e., VAMP and SNAP-25) bound must also be reduced. To test this hypothesis, bovine brain extract was incubated with immobilized GST-fusion proteins, either wild-type or D216N Munc18-1, and bound proteins were identified by immunoblotting. As seen previously with the PC12 cell immunoprecipitates, the amount of bound syntaxin was reduced for the D216N mutant in comparison with wild-type Munc18-1 (Figure 2A). This was quantified as a 42% reduction in binding. The blots were subsequently reexposed to an anti-SNAP-25 and an anti-VAMP antibody to assess the amount of bound SNAREs and found that there was a 53% reduction in the amount of bound SNAP-25 and a 74% reduction in the amount of bound VAMP to Munc18-1 D216N in comparison with wild type (Figure 2A). To confirm this result, an alternative experiment was performed using the exocytotic protein complexin-II because complexin-II binds specifically to the assembled SNARE complex (Pabst et al., 2000; Archer et al., 2002), although there are accounts of possible binding to a VAMP:syntaxin heterodimer (Xue et al., 2007). Recombinant GST–complexin-II readily pulled out the assembled SNARE complex from brain extract (Figure 2B). Introduction of a mutation (R59H) that results in a deficiency in SNARE complex binding (Xue et al., 2007), however, blocked the SNARE complex pull-down. Comparison of boiled versus nonboiled samples (Figure 2B) indicated that at least 90% of each of the SNAREs was present in SDS-resistant SNARE complexes. In vitro produced Munc18-1 (wild type or D216N) was then incubated with the isolated SNARE complex in a binding reaction (Figure 2C). We could demonstrate that this assay predominantly reflects binding of complexin to the assembled SNARE complex (Boyd et al., 2008) as N-ethylmaleimide treatment, which blocks mode 1 Munc18-1 binding to syntaxin (Palmer et al., 2008), did not affect binding to the GST–complexin pull-down (data not shown). There was a 36.0 ± 3.77% (n = 3) reduction in binding of Munc18-1 D216N to the assembled SNARE complex associated with GST-complexin-II in comparison to wild-type protein. Therefore, two separate experiments have demonstrated a specific reduction in mode 3 binding of Munc18-1 D216N to the SNARE complex.

Figure 2.

The Munc18-1 D216N mutation specifically inhibits binding to the assembled SNARE complex (mode 3). (A) Brain extract was incubated with GST, wild-type GST-Munc18-1 (W/t), or mutant GST-Munc18-1 (D216N) and the bound proteins were assessed by Western blotting with various antisera as indicated. Despite equal amounts of Munc18-1, there was a 41.9% reduction in bound syntaxin (n = 4), a 52.1% reduction in bound SNAP-25 (n = 3) and a 73.5% reduction in the vesicle SNARE VAMP (n = 3). (B) Brain extract was incubated with GST, wild-type GST-complexin-II (CPXII), or mutant GST-complexin-II (R59H), and bound samples were either boiled (+) or unboiled (−). The association of native SNARE complexes (syntaxin, SNAP-25, and VAMP; indicated by a vertical line to the right of the blot) with complexin-II was verified by Western blotting with antisera against the individual SNAREs. The R59H complexin-II mutant abolished binding of the SNARE complex (individual SNAREs indicated by arrows). The extent of SNARE monomer in the nonboiled samples was assessed as a percentage of monomer in boiled samples and quantified as 10.5% (syntaxin), 8.1% (SNAP-25), and 11.4% (VAMP). (C) Incubation of the radiolabeled W/t or D216N Munc18-1 with the native SNARE complexes isolated in Figure 3B. Samples of supernatant (Unbound) and bound proteins were detected by autoradiography. The extent of binding of the D216N Munc18-1 to the native SNARE complexes was reduced by 36.0% compared with W/t Munc18-1.

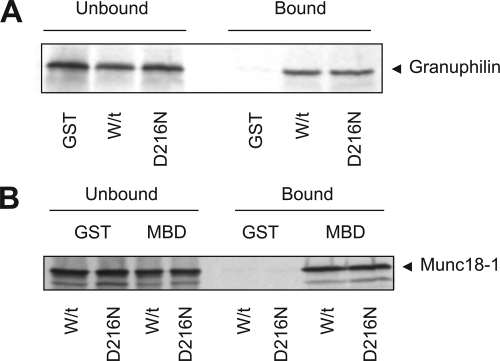

Munc18-1 Interactions with Other Binding Partners

The ability of the mutation to affect other Munc18-1 interacting proteins was also investigated. In binary protein reactions, Munc18-1 readily associates with granuphilin A (Figure 3A) and Mints-1/2 (Figure 3B). There were no apparent differences in the extent of binding of the mutant Munc18-1 in comparison with wild type, indicating that the mutation does not affect protein interactions in general.

Figure 3.

Binding of wild-type and D216N Munc18-1 to granuphilin A and the Mint 1-Munc18 binding domain. (A) Radiolabeled granuphilin A was bound to either immobilized GST, wild-type (W/t), or mutant (D216N) GST-Munc18-1. Samples of supernatant (Unbound) and bound proteins were detected by autoradiography. Extent of binding was not different for the D216N Munc18-1 compared with wild-type protein. (B) GST, wild-type GST-Munc18-1 (W/t), or mutant GST-Munc18-1 (D216N) were incubated with radiolabeled MBD of Mint 1. Extent of binding was not different for W/t versus D216N.

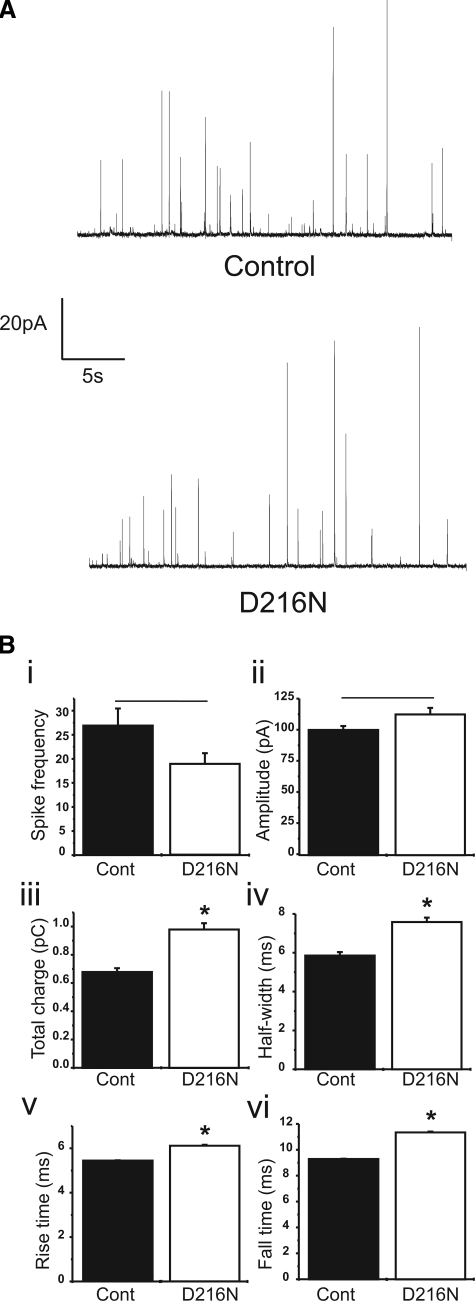

Exocytotic Phenotype of the D216N Mutation

We next investigated the effect of the D216N mutation in exocytosis. In vitro liposome fusion assays have shown that Munc18-1 accelerates fusion via its interaction with the SNARE complex (Shen et al., 2007), in line with similar experiments for mode 3 binding of the SM protein Sec1p (Scott et al., 2004). Because our point mutation specifically reduced SNARE complex binding, we predicted that it should act to slow the fusion process. To verify this prediction, we expressed the Munc18-1 D216N protein in freshly cultured bovine adrenal chromaffin cells and assayed for alterations to dense-core granule exocytosis by carbon fiber amperometry. Amperometry records single fusion events in time by monitoring the electrochemical oxidation of the released neurotransmitter from the underlying fusion event (Figure 4A; Travis and Wightman, 1998). Cells were stimulated with a mixture of digitonin/calcium, a protocol that produces spikes indistinguishable from those evoked by agonists in intact cells (Jankowski et al., 1992) but with uniform cellular calcium concentrations. Expression of wild-type Munc18-1 has no effect on amperometric spikes in our system (Fisher et al., 2001) as is also the case in the mouse knockout (Voets et al., 2001). As predicted, however, transfected cells expressing the D216N mutant had amperometric spikes of increased duration (Figure 4B). There was no obvious effect of D216N Munc18-1 on spike frequency (Figure 4Bi), indicating that recruitment of vesicles was unaffected. Furthermore, there was no difference in spike peak amplitude (Figure 4Bii). Because spike amplitude reflects alterations to granule content (Pothos et al., 2002; Sombers et al., 2004), this indicates that the D216N mutation is unlikely to alter neurotransmitter loading of dense core granules. Cells expressing D216N mutation, however, had amperometric spikes of greater spike charge (Figure 4Biii) and prolonged duration (Figure 4B, iv–vi). These data indicate that the mutation does indeed cause slower individual fusion events as predicted by the biochemistry.

Figure 4.

Expression of Munc18-1 D216N increases quantal size and slows fusion kinetics. (A) Exemplary amperometric traces from an untransfected cell (Control; top trace) and a cell transfected with the Munc18-1 D216N mutant (D216N; bottom trace) after stimulation of regulated exocytosis with digitonin/Ca2+. (B) Both the frequency (i) and amplitude (ii) of amperometric spikes were not different between control and Munc18-1 D216N-expressing cells. (iii) Quantal size of individual amperometric spikes, however, were increased for D216N cells compared with control cells (p < 0.001). (iv–vi) The duration of amperometric spikes were prolonged for cells expressing Munc18-1 D216N. There was an increase in spike half-width, rise time and fall time (p < 0.001) compared with control, untransfected cells. Data were analyzed from 701 spikes from 26 cells (control) and 474 spikes from 25 cells (D216N).

In Vivo Phenotype of the Orthologous D214N Mutation in C. elegans

We wanted next to determine whether the D216N mutation resulted in an in vivo phenotype. To that end, transgenic rescues of the C. elegans unc-18 null mutant e81 were created. We reasoned that using C. elegans as a model system for testing our mammalian mutation in a clean genetic background would be appropriate for the following reasons: 1) UNC-18 carries high sequence homology with synaptic Munc18-1 (85.7% to human Munc18-1); 2) SM proteins show very similar overall structure (Misura et al., 2000; Bracher and Weissenhorn, 2001; Bracher and Weissenhorn, 2002); 3) alterations in biochemical interactions (mode 1) are transferable to the mammalian protein (Sassa et al., 1999; Ciufo et al., 2005); 4) UNC-18 and Munc18-1 are functionally orthologous as the unc-18 null worm is phenotypically rescued by expression of Munc18-1 (Gengyo-Ando et al., 1996); and 5) C. elegans has been used previously as a model for the acute effects of ethanol in mammalian species (Davies et al., 2003, 2004). The e81 allele carries a point mutation that results in a premature stop codon (Sassa et al., 1999), resulting in a null phenotype. The UNC-18 null animals demonstrate acetylcholine accumulation, trichlorfon resistance, retarded locomotion, and severe paralysis (Hosono et al., 1992; Sassa et al., 1999). Electrophysiological recordings show that both evoked and spontaneous neuromuscular transmission is greatly reduced in e81s (Weimer et al., 2003). In the e81s, syntaxin levels are reduced by ∼50% but localized properly (Weimer et al., 2003), which is similar to that seen in the mouse knockout (Toonen et al., 2005).

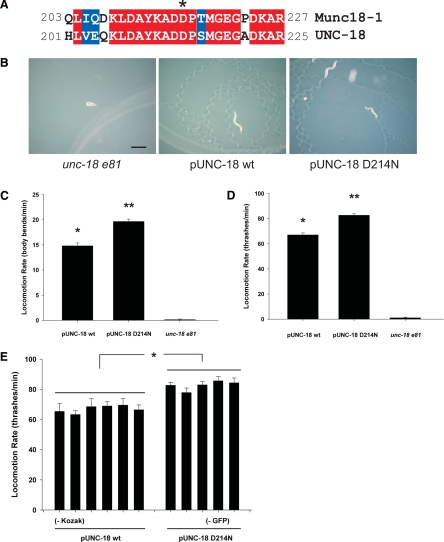

For direct phenotypic comparison, transgenic rescues of the e81 null mutants were made with either wild-type UNC-18 or the D214N mutation (orthologous to D216N in mouse; Figure 5A). To avoid gross overexpression and/or mislocalization the rescuing transgene utilized the endogenous UNC-18 promoter (Gengyo-Ando et al., 1996). Transgenic rescue of the e81 nulls with either wild-type or D214N UNC-18 produced phenotypically normal worms, indicating a lack of severe effect of the mutation on vesicle fusion in the worm. On plates, either transgenic rescue moved with the characteristic sinusoidal body bend movement and with a similar rate of locomotion (Figure 5B and Supplemental Videos 1–3). There were also no obvious differences in egg laying, pharyngeal pumping, growth rate, or lifespan. Quantification of locomotor rate on agar plates, however, did reveal that the D214N mutants moved slightly faster (∼20%) than the wild-type rescues (Figure 5C). This increase in locomotion was consistent for both swimming in solution (Figure 5D) and for movement through OP50 E. coli on agar plates (data not shown). Because both decreases and increases in SM protein level have been shown to be detrimental to neurotransmitter release (Schulze et al., 1994; Wu et al., 1998), it was important to confirm that the phenotypic effects seen here were not dependent upon a differential expression level of wild-type and D214N UNC-18. To that end, multiple independent transgenic lines for both the wild-type and D214N mutant rescues were generated (Figure 5E). Although there were no significant differences in locomotion between any individual wild-type rescues or between any individual D214N rescues, the ∼20% increase in locomotor rate for the mutant in comparison with wild type was consistent for all lines. A lack of effect of the coinjected GFP reporter construct was verified by excluding it from three of the independent transgenic lines, selecting positive rescue by phenotype alone. To assess whether very small differences in protein expression could impart phenotypic effects on locomotion rate, the Kozak consensus sequence was excluded from two of the independent transgenic lines and again found to have no phenotypic effect in comparison with other rescues.

Figure 5.

Transgenic C. elegans expressing UNC-18 D214N move phenotypically as wild type. (A) Sequence alignment of Munc18-1 and UNC-18 proteins. Twenty-five amino acids, centered around the target residue Asp216/214 (*), are shown. Identical amino acids are highlighted in red; similar amino acids in blue. (B) The unc-18 e81 null background was transgenically rescued with either wild-type (wt) or mutant (D214N) UNC-18. The photographs depict trails left from five worms after 10 min moving over an OP50 bacterial lawn. Bar, 0.5 mm. (C) Locomotion rate of the unc-18 e81 transgenic rescues was quantified by counting sinusoidal body bends per minute on unseeded NGM plates. Both wild-type and D214N UNC-18 restored coordinated locomotion compared with e81 (*p < 0.001); however, D214N rescues moved faster than wild types (**p < 0.001). Data were analyzed from 100 pUNC-18 wt, 87 pUNC-18 D214N, and 15 e81 worms. (D) Locomotion rate of the unc-18 e81 transgenic rescues was quantified by counting thrashes per minute in solution. Both wt and mutant (D214N) rescues restored coordinated locomotion compared with e81 worms (*p < 0.001); however, D214N worms moved faster than wild types (**p < 0.001). Data were analyzed from 101 pUNC-18 wt, 83 pUNC-18 D214N, and 25 e81 worms. (E) Locomotion rate, as quantified by thrashes per minute in solution, for individual transgenic rescue lines. For two of the pUNC-18 wt rescues, the Kozak consensus sequence was removed from the rescuing transgene (indicated by − Kozak). For three of the pUNC-18 D214N rescues, the cotransforming marker GFP was excluded (indicated by − GFP). All pUNC-18 wt lines were not different from each other (p > 0.15), and all pUNC-18 D214N lines were also not different from each other (p > 0.15). All pairwise comparisons between individual wild-type and D214N transgenic lines were statistically different (*p < 0.05) except for D214N line 2 versus wild-type lines 3 and 5 (p = 0.13 for each). Data were analyzed from six individual pUNC-18 wt lines (from the left, n = 16, 17, 17, 17, 17, and 17) and five pUNC-18 D214N lines (from the left, n = 17, 17, 16, 17, and 16).

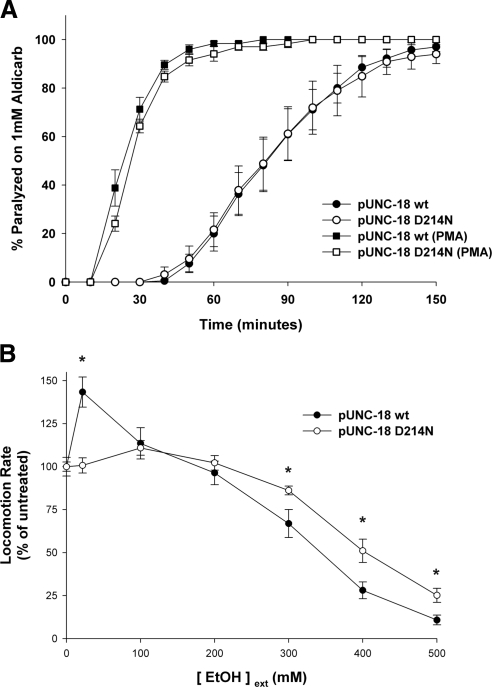

Whole organism locomotion will be a result of both the coordinated patterns of motor activity that are generated by the worm's CNS and the strength of the end-point signal at the body wall neuromuscular junction. One well characterized assay for cholinergic release from C. elegans motorneurons is the aldicarb assay (Mahoney et al., 2006). Aldicarb is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, exposure to which progressively causes paralysis as neurotransmitter builds up in the neuromuscular junction and body wall muscles hypercontract. Most C. elegans uncoordinated mutants exhibit resistance to aldicarb, whereas mutations that grossly increase acetylcholine release are hypersensitive to aldicarb (Nurrish, 2002). Basal neuromuscular junction secretion was quantified in a paralysis assay at 1 mM aldicarb, and it was found that there was no differences in cholinergic release from motorneurons between wild-type and D214N mutant rescues (Figure 6A). In light of a lack of difference in peak current of amperometric spikes (Figure 4) and the mild differences in locomotion (Figure 5) for the D216/214N mutant in comparison to wild-type protein, a lack of discernible effect was perhaps not unexpected. It remained a possibility that a phenotypic difference would become apparent if the neuromuscular junction was challenged with a positive stimulus to enhance release, such as the phorbol ester PMA (Lackner et al., 1999). On incubation with 2 μg/ml PMA, however, there was still no difference in cholinergic release between wild-type and D214N UNC-18 transgenic rescues, although the PMA was confirmed to cause hypersensitivity to aldicarb in both cases (Figure 6A). These data indicate that the effect of the D214N mutation to increase locomotor rate slightly is unlikely to be caused by an enhancement in the strength of synaptic transmission and is more likely a result of changes in signaling within the worm CNS.

Figure 6.

Transgenic rescue with mutant UNC-18 D214N confers resistance to ethanol without affecting acute sensitivity to aldicarb. (A) Individual transgenic rescues, either wild-type (pUNC-18 wt) or mutant (pUNC-18 D214N) were exposed to 1 mM aldicarb. The aldicarb experiments were repeated following a 2-h pre-exposure to either untreated NGM plates or plates containing 2 μg/ml PMA to hypersensitize worms to aldicarb. In all experiments, onset of paralysis was assayed every 10 min after drug exposure by prodding the worms. Data were analyzed from at least 20–25 worms per transgenic line per experiment (at least 3 separate experiments). (B) Locomotion rate of the unc-18 e81 transgenic rescues was quantified by counting thrashes per minute in solution with various concentrations of external ethanol. Measurements of locomotion for either wild-type (pUNC-18 wt) or mutant (pUNC-18 D214N) rescues were made as a percentage of mean locomotion rate in 0 mM ethanol measured each day (at least 10 control worms per transgenic line). Pairwise comparisons between transgenic lines were significantly different (*) at 22 mM (p < 0.001), 300 mM (p = 0.03), 400 mM (p < 0.01), and 500 mM (p < 0.01).

In Vivo Acute Ethanol Phenotype of the D214N Mutation

Because the mouse D216N polymorphism in the Munc18-1 gene was correlated with a phenotypic change in ethanol preference (Fehr et al., 2005), our main aim was to assess this link in our otherwise isogenic background. Exposure of C. elegans to ethanol in the 100–500 mM external concentration range causes a dose-dependent decrease in the rate of locomotion on agar plates and in solution (Davies et al., 2003; Mitchell et al., 2007). The rate of locomotion for both the wild-type and D214N UNC-18 transgenic rescues were assessed in solution, to ensure the worm was exposed to a uniform concentration of external ethanol. Locomotion rates were measured at 10-min postethanol exposure to avoid any development of acute tolerance such as seen with mutations in the npr-1 gene (Davies et al., 2004); however, preliminary time-course experiments did not indicate any effects of the UNC-18 mutation on acute tolerance. As seen previously, increasing ethanol concentration from 100 to 500 mM dramatically decreased the animals locomotion rate and coordinated movement was qualitatively depressed (Figure 6B and Supplemental Videos 4–7). Interestingly, the effects of ethanol to depress activity were significantly decreased for transgenic worms expressing the UNC-18 D214N mutation. The protective effect of the mutation was demonstrated convincingly by an increase in the difference in basal locomotion rate between wild type and D214N from 20% at 0 mM ethanol to 230% at 500 mM.

Exposure to low concentrations of ethanol are known to have stimulatory effects on organismal activity; however, this has not yet been shown for C. elegans. The range of tested external ethanol concentrations was therefore expanded to determine whether C. elegans locomotion exhibited this effect. Indeed, wild-type transgenic rescues had a significant increase in their rate of locomotion at 0.1% external ethanol in comparison to controls (Figure 6B). Surprisingly, transgenic rescues with the D214N UNC-18 mutation completely lost any ethanol-induced hyperactivity. Therefore, the protective effect of the D214N mutation was applicable for both the stimulatory and depressive effects of external ethanol.

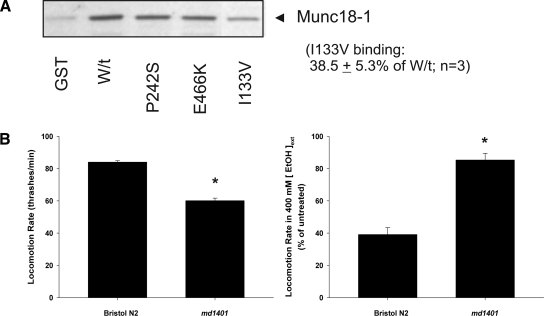

In Vivo Acute Ethanol Phenotype of the unc-18 md1401 Mutation

We have demonstrated previously exocytotic phenotypes for a number of single amino acid mutations in Munc18-1 modeled on those identified in Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Ciufo et al., 2005). Of the mutations investigated, three (P242S, E466K, and I133V) have exocytotic phenotypes, as assayed by carbon fiber amperometry, without any reduction in mode 1 binding to syntaxin. Munc18-1 P242S has a reduction in binding to Mints-1/2 (Ciufo et al., 2005) and Munc18-1 E466K has an increase in binding to Rab3A (Graham et al., 2008); however, there are no known binding deficiencies for the I133V mutation. The I133V mutation confers the same amino acid substitution found in the C. elegans unc-18 (md1401) mutant, but at an isoleucine located two amino acids from the homologous Munc18-1 residue. C. elegans md1401 mutants have mild behavioral defects, including slightly slower locomotion (Sassa et al., 1999). Interestingly, the I133V mutation produces an amperometric phenotype that is similar to that seen with Munc18-1 D216N; chromaffin cells expressing the I133V mutation have amperometric spikes with an increased spike charge and broader spike duration in comparison with control cells (Ciufo et al., 2005). Considering the similar amperometric phenotype to that D216N mutation, we determined whether Munc18-1 I133V had a reduction in mode 3 binding to the assembled SNARE complex. As before, in vitro produced Munc18-1 was incubated with the assembled SNARE complex, pulled out from brain extract by recombinant GST–complexin-II. Neither the P242S or the E466K mutations altered the amount of Munc18-1 binding to the assembled SNARE complex in comparison with wild type; however, there was a 61.5% reduction in binding of Munc18-1 I133V (Figure 7A). The in vivo phenotype of the md1401 mutation was next assessed by comparing the locomotion rate in solution with wild-type Bristol N2 worms in 0 mM external ethanol. Quantification of locomotor rate confirmed that the md1401 mutants moved slightly slower (∼30%) than the wild-type rescues (Figure 7B). Finally, the in vivo ethanol phenotype of the md1401 mutants was assessed by comparing the reduction in locomotion rate conferred at 400 mM external ethanol. Similar to that seen with the D214N mutants, the effects of ethanol to depress behavioral activity was reduced for md1401 worms in comparison with Bristol N2 wild types (Figure 7C). Therefore, the I133V/md1401 data indicate a conservation in amperometric exocytotic phenotype, SNARE complex binding and acute ethanol sensitivity with the D214N mutation, independent of initial locomotion rate of the worm strain.

Figure 7.

UNC-18 I133V inhibits SNARE complex binding and confers resistance to ethanol. (A) Incubation of radiolabeled W/t, P242S, E466K, or I133V Munc18-1 with native SNARE complexes isolated from brain extract with GST-complexin-II. Samples of bound proteins were detected by autoradiography. The extent of binding of the I133V Munc18-1 to the native SNARE complexes was reduced by 61.5% in comparison to W/t Munc18-1. There was no reduction in binding for either P242S or E466K Munc18-1. (B) Locomotion rate of the I133V C. elegans mutant unc-18 (md1401) was quantified by counting thrashes per minute in solution with 0 mM external ethanol. In comparison with Bristol N2 wild-type worms, md1401 mutants moved slower (*p < 0.001). Data were analyzed from 154 N2 and 171 md1401 worms. (C) Effect of acute exposure to external ethanol was determined by quantifying locomotion rate in a solution of 400 mM external ethanol. Measurements were made as a percentage of mean locomotion rate in 0 mM ethanol measured each day (at least 10 control worms per strain). Impairment of locomotion by 400 mM ethanol was significantly reduced in md1401 worms in comparison to Bristol N2 (*p < 0.001). Data were analyzed from 6 individual experiments of at least 10 worms per strain.

DISCUSSION

Previous genetic screens in C. elegans have isolated mutations that alter ethanol effects on locomotion, specifically unc-79, gas-1, gas-2 (Morgan and Sedensky, 1995), slo-1 (Davies et al., 2003), and most recently, rab-3 (Kapfhamer et al., 2008). slo-1 encodes a BK channel that is directly activated by ethanol and loss-of-function mutants are resistant to ethanol at high external concentrations. Intriguingly, the UNC-18 D214N mutation not only produces resistance to the depressive action of ethanol at high concentrations but also to the stimulatory action at low concentrations (Figure 6B). Direct interaction between BK channels and the exocytotic machinery is unlikely due to spatial restriction; however, there are interesting genetic links. Loss-of-function mutants of slo-1 act as suppressors for certain syntaxin hypomorphic mutations (Wang et al., 2001). In addition, mutations in either syntaxin (van Swinderen et al., 1999) or slo-1 (Hawasli et al., 2004) reduce the effect of volatile anesthetics (VAs) to depress locomotion. Sensitivity to VAs is antagonized by expression of a truncated syntaxin fragment or overexpression of UNC-13 (Metz et al., 2007). As some evidence points to UNC-13 binding to the N terminus of syntaxin (Betz et al., 1997) or directly to the SNARE complex (Guan et al., 2008), this may demonstrate a convergence of pathways to transduce the effects of VAs and ethanol at the level of the exocytotic machinery. Consistent with this hypothesis is the similar amperometric (Ciufo et al., 2005), biochemical and behavioral (Figure 7) phenotype evident for Munc18-1 I133V (md1401) and a recent report demonstrating that loss of RAB-3 affects behavioral responses to ethanol (Kapfhamer et al., 2008), because RAB-3 is a synaptic vesicle protein that can bind directly to Munc18-1 (Graham et al., 2008). It remains unclear whether the ethanol-induced BK channel signal and the effects on the SNAREs/UNC-18 are operating in series or in parallel.

There has been some debate over the internal concentration of ethanol in C. elegans in response to external exposure (Davies et al., 2003; Mitchell et al., 2007). It is reassuring, however, that the worm has a typical dose-dependent response to ethanol whereby low concentrations induce hyperactivity and high concentrations are sedative. The UNC-18 D214N mutation counters all effects of acute ethanol on locomotion (Figure 6B), indicating a central role in the transduction of an ethanol signal at the synapse. For slo-1 mutants, alternatively, the BK channel current is increased at both stimulatory and depressive concentrations (Davies et al., 2003), yet there was no reported effect of slo-1 on hyperactivity. Importantly, the effects of a variety of mutants show that an induced resistance to ethanol is uncorrelated with basal locomotor rate. Unlike our coordinated, slightly hyperactive UNC-18 D214N mutants, md1401 (UNC-18 I133V) worms are slightly slower (Figure 7) whereas loss-of-function in slo-1 leads to slow, jerky locomotion (Davies et al., 2003). Conversely, the syntaxin hypomorphic mutants with VA tolerance are very uncoordinated, whereas some of the unc-13 mutants are unaffected (Metz et al., 2007). This is indicative of specific molecular targets for the action of ethanol at the synapse rather than a generalized effect to alter synaptic release and that the resistance of the UNC-18 mutants is not specifically predicated upon the basal locomotor rate of the worms.

A conserved function of Munc18-1 in secretion remains controversial, in part because of the inconsistencies in the conformational mode of binding to syntaxin-1 (Burgoyne and Morgan, 2007). In mode 1 binding, Munc18-1 interacts with the closed conformation of syntaxin, precluding its participation in the assembled SNARE complex (Yang et al., 2000). The functional significance of this interaction has stemmed from mutational (Fisher et al., 2001; Richmond et al., 2001) and structural (Misura et al., 2000) analysis. Recent work has pointed to mode 1 binding being involved upstream of the actual fusion event in vesicle recruitment, bridging Rab- and SNARE-mediated events (Graham et al., 2008) and in vesicle docking (Gulyas-Kovacs et al., 2007). Because this binding conformation is restricted to regulated exocytosis it is thought unlikely to provide the integral evolutionarily conserved function of SM proteins. Alternatively, modes 2/3 represent binding interactions between Munc18-1 and syntaxin that are conserved for SM proteins in yeast indicating a more intrinsic function. In Mode 2 binding Munc18-1 interacts with the extreme N-terminus of syntaxin (Dulubova et al., 2002, 2007; Rickman et al., 2007). Although little is known about the functional significance of this interaction for Munc18-1, inhibition of mode 2 binding in yeast Vps45p (Carpp et al., 2006) and Sly1p (Peng and Gallwitz, 2004) reveals no obvious defects in membrane traffic.

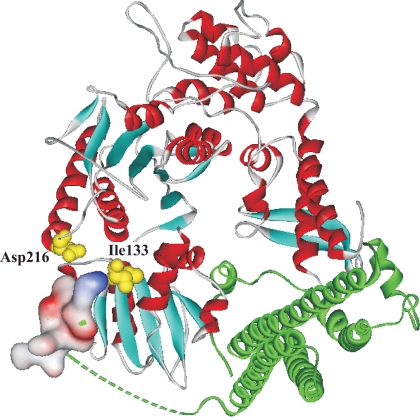

In contrast to modes 1/2, there is no structural information for mode 3 binding and, as such, there are no known mutations that affect this form of binding. We demonstrate here that the D216N polymorphism (Figures 1 and 2) and the I133V mutation (Figure 7) are novel specific inhibitors for mode 3 binding that permits an in vivo dissection of the function of this interaction. The mutations are located close together, structurally in domain 2 of Munc18-1 on the exterior face of the protein (Figure 8). Although the mutations are close to the site of interaction with the N terminus of syntaxin, they did not seem to affect mode 2 binding. Lack of information on mode 3 structure precludes evidence in support of Asp216 or Ile133 directly interacting with syntaxin; however, it could be speculated that the accessibility of the exposed residue may be involved in some interaction with a section of the assembled SNARE complex. Alternatively, the mutations could induce a conformational change in Munc18-1, thereby producing the observed reduction in binding. Overexpression of the mode 3-deficient D216N mutant in mammalian cells produced individual fusion events with increased duration (Figure 4) similar to that for I133V (Ciufo et al., 2005). Liposome fusion assays have shown in vitro that Munc18-1 accelerates fusion via its SNARE complex interaction (Shen et al., 2007). Because changes in amperometric spike parameters are consistent with alterations in fusion pore expansion (Neco et al., 2008) and initial catecholamine release rates (Barclay, 2008) the increased duration of individual fusion events of D216N-expressing cells agrees with the observed decrease in SNARE complex binding.

Figure 8.

Location of mutated residues in Munc18-1. Structure of the Munc18-1/syntaxin 1A complex showing the position of the residues mutated in this study. Both amino acids (Asp216 and Ile133) are highlighted in yellow The N-terminal peptide of syntaxin 1A was rendered as a surface electrostatic potential map and the region of syntaxin between Arg9 and Arg27 has been represented as a dashed green line to reflect the disorder in the crystal structure in that region of the protein. The coordinates of the Munc18-1/syntaxin 1A structure comes from the PDB file 3C98 (Burkhardt et al., 2008).

The in vivo effects of the D216N mutation was tested on a null background in C. elegans. Because the mode 3 Munc18-1/syntaxin interaction is conserved evolutionarily, it was thought that the mutation should be transferable from mammalian to nematode protein. This is supported by the high degree of uniformity in protein homology, structure (Misura et al., 2000; Bracher and Weissenhorn, 2001; Bracher and Weissenhorn, 2002), biochemistry (Sassa et al., 1999; Ciufo et al., 2005), and functional interchangeability (Gengyo-Ando et al., 1996). Expression of the orthologous D214N mutation in unc-18 null worms had no effect on neurotransmitter release measured by the aldicarb assay (Figure 6A). Because the aldicarb assay analyses synaptic transmission in the worm (Lackner et al., 1999; Mahoney et al., 2006; Sieburth et al., 2007) this indicates that the mutation confers no gross defect in exocytosis. This result is consistent with a lack of effect on amperometric spike amplitudes. Although there was a 40% increase in amperometric charge from D216N-expressing cells, the total charge transfer during the recording period was virtually identical for control and D216N-expressing cells (18.31 pC vs. 18.49 pC, respectively); thus, we did not consider it likely that the amperometric alterations would result in an observable phenotype in the aldicarb assay.

The D214N mutation did, however, produce a modest increase in the locomotor output of the worm CNS (Figure 5), as measured by the frequency of body bend or thrashing. It is possible that very small changes in the kinetics or amounts of vesicle release could be overlooked by the aldicarb assay, yet quantifiable by examination of locomotor pattern generation. Indeed, cysteine string protein knockout in Drosophila produces larval paralysis at high temperature; yet, this is correlated to a deficiency in the generation of coordinated motor patterns within the CNS and not a direct result of synaptic failure at neuromuscular junctions (Barclay et al., 2002). C. elegans locomotion is both governed and regulated by numerous excitatory and inhibitory synaptic interactions (de Bono and Maricq, 2005). Because the transgenic worms will express the D214N mutation throughout the organism, it is unknown at what hierarchical level (sensory neuron, interneuron, or motorneuron), the mutation imparts its effect. It remains speculative but not unreasonable to suggest, however, that an increased duration and quantal size of exocytosis within the worm's CNS underlies the mild hyperlocomotion phenotype of the transgenic mutants.

A recent genetic study indicated a correlation between the D216N polymorphism and changes to ethanol preference in mice (Fehr et al., 2005). Ethanol preference and indeed risk of alcoholism is phenotypically linked with a reduced level of response to alcohol (Schuckit et al., 2004). We demonstrate that there is indeed a direct effect of the D216/4N polymorphism on acute ethanol resistance at both stimulatory and depressive concentrations and that this effect is replicated in md1401 (I133V) mutant worms. The synapse has been suggested to be the most ethanol sensitive element of the CNS (Siggins et al., 2005) and the interaction between the SNARE complex and Munc18-1 may well be an important target for the transduction of effects. Intriguingly, rats that have undergone in vivo chronic ethanol exposure to mimic alcoholism have decreased levels of Munc18-1 protein in the brain (Rajgopal and Vemuri, 2001). Our results indicate that ethanol has effects presynaptically at the very heart of the exocytotic machinery and support the argument that the induced reduction in the Munc18-1 and SNARE complex binding conferred by the polymorphism mutation may underlie the robust preservation of C. elegans behavior during acute ethanol exposure.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (to A.M. and R.D.B.) and the Royal Society (to J.W.B.) and a Research Councils UK academic fellowship (to J.W.B.). M.R.E. was supported by a Medical Research Council studentship. The e81 strain used in this work was provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0689) on October 15, 2008.

REFERENCES

- Archer D. A., Graham M. E., Burgoyne R. D. Complexin regulates the closure of the fusion pore during regulated exocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:18249–18252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200166200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arunachalam L., et al. Munc18-1 is critical for plasma membrane localization of Syntaxin1 but not of SNAP-25 in PC12 cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:722–734. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-07-0662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay J. W. Munc-18-1 regulates the initial release rate of exocytosis. Biophys. J. 2008;94:1084–1093. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.111203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay J. W., Atwood H. L., Robertson R. M. Impairment of central pattern generation in Drosophila cysteine string protein mutants. Journal of comparative physiology. 2002;188:71–78. doi: 10.1007/s00359-002-0279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay J. W., Craig T. J., Fisher R. J., Ciufo L. F., Evans G. J., Morgan A., Burgoyne R. D. Phosphorylation of Munc18 by protein kinase C regulates the kinetics of exocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:10538–10545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M. K., Calakos N., Scheller R. H. Syntaxin: a synaptic protein implicated in docking of synaptic vesicle at presynaptic active zones. Science. 1992;257:255–259. doi: 10.1126/science.1321498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz A., Okamoto M., Benseler F., Brose N. Direct interaction of the rat unc-18 homologue Munc13-1 with the N terminus of syntaxin. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:2520–2526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd A., Ciufo L. F., Barclay J. W., Graham M. E., Haynes L. P., Doherty M. K., Riesen M., Burgoyne R. D., Morgan A. A random mutagenesis approach to isolate dominant negative yeast sec1 mutants reveals a functional role for Domain 3a in yeast and mammalian SM proteins. Genetics. 2008;180:165–178. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.090423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracher A., Weissenhorn W. Crystal structures of neuronal squid sec1 implicate inter-domain hinge movement in the release of t-SNAREs. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;306:7–13. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracher A., Weissenhorn W. Structural basis for the Golgi membrane recruitment of Sly1p by Sed5p. EMBO J. 2002;21:6114–6124. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne R. D., Morgan A. Secretory granule exocytosis. Physiol. Rev. 2003;83:581–632. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne R. D., Morgan A. Membrane trafficking: three steps to fusion. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:R255–R258. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt P., Hattendorf D. A., Weis W. I., Fasshauer D. Munc18a controls SNARE assembly through its interaction with the syntaxin N-peptide. EMBO J. 2008;27:923–933. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpp L. N., Ciufo L. F., Shanks S. G., Boyd A., Bryant N. J. The Sec1p/Munc18 protein Vps45p binds its cognate SNARE proteins via two distinct modes. J. Cell Biol. 2006;173:927–936. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciufo L. F., Barclay J. W., Burgoyne R. D., Morgan A. Munc18-1 regulates early and late stages of exocytosis via syntaxin-independent protein interactions. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:470–482. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig T. J., Ciufo L. F., Morgan A. A protein-protein binding assay using coated microtitre plates: increased throughput, reproducibility and speed compared to bead-based assays. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods. 2004;60:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jbbm.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A. G., Bettinger J. C., Thiele T. R., Judy M. E., McIntire S. L. Natural variation in the npr-1 gene modifies ethanol responses of wild strains of C. elegans. Neuron. 2004;42:731–743. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A. G., Pierce-Shimomura J. T., Kim H., VanHoven M. K., Thiele T. R., Bonci A., Bargmann C. I., McIntire S. L. A central role of the BK potassium channel in behavioral responses to ethanol in C. elegans. Cell. 2003;115:655–666. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00979-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bono M., Maricq A. V. Neuronal substrates of complex behaviors in C. elegans. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;28:451–501. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulubova I., Khvotchev M., Liu S., Huryeva I., Sudhof T. C., Rizo J. Munc18-1 binds directly to the neuronal SNARE complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611318104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulubova I., Sugita S., Hill S., Hosaka M., Fernandez I., Sudhof T. C., Rizo J. A conformational switch in syntaxin during exocytosis: role of munc18. EMBO J. 1999;18:4372–4382. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.16.4372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulubova I., Yamaguchi T., Gao Y., Min S.-W., Huryeva I., Sudhof T. C., Rizo J. How TIg2p/syntaxin 16 “snares” Vps45. EMBO J. 2002;21:3620–3631. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr C., Shirley R. L., Crabbe J. C., Belknap J. K., Buck K. J., Phillips T. J. The syntaxin binding protein 1 gene (Stxbp1) is a candidate for an ethanol preference drinking locus on mouse chromosome 2. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2005;29:708–720. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164366.18376.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R. J., Pevsner J., Burgoyne R. D. Control of fusion pore dynamics during exocytosis by Munc18. Science. 2001;291:875–878. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5505.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gengyo-Ando K., Kitayama H., Mukaida M., Ikawa Y. A murine neural specific homolog corrects cholinergic defects in Caenorhabditis elegans unc-18 mutants. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:6695–6702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-06695.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham M. E., Barclay J. W., Burgoyne R. D. Syntaxin/Munc18 interactions in the late events during vesicle fusion and release in exocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:32751–32760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400827200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham M. E., Fisher R. J., Burgoyne R. D. Measurement of exocytosis by amperometry in adrenal chromaffin cells: effects of clostridial neurotoxins and activation of protein kinase C on fusion pore kinetics. Biochimie. 2000;82:469–479. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)00196-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham M. E., Handley M. T., Barclay J. W., Ciufo L. F., Barrow S. L., Morgan A., Burgoyne R. D. A gain of function mutant of Munc18-1 stimulates secretory granule recruitment and exocytosis and reveals a direct interaction of Munc18-1 with Rab3. Biochem. J. 2008;409:407–416. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham M. E., O'Callaghan D. W., McMahon H. T., Burgoyne R. D. Dynamin-dependent and dynamin-independent processes contribute to the regulation of single vesicle release kinetics and quantal size. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:7124–7129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102645099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan R., Dai H., Rizo J. Binding of the Munc13-1 MUN domain to membrane-anchored SNARE complexes. Biochemistry. 2008;47:1474–1481. doi: 10.1021/bi702345m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulyas-Kovacs A., de Wit H., Milosevic I., Kochubey O., Toonen R., Klingauf J., Verhage M., Sorensen J. B. Munc18-1, sequential interactions with the fusion machinery stimulate vesicle docking and priming. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:8676–8686. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0658-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafez I., Kisler K., Berberian K., Dernick G., Valero V., Yong M. G., Craighead H. G., Lindau M. Electrochemical imaging of fusion pore openings by electrochemical detector arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:13879–13884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504098102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawasli A. H., Saifee O., Liu C., Nonet M. L., Crowder C. M. Resistance to volatile anesthetics by mutations enhancing excitatory neurotransmitter release in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2004;168:831–843. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.030502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosono R., Hekimi S., Kamiya Y., Sassa T., Murakami S., Nishiwaki K., Miwa J., Taketo A., Kodaira K. I. The unc-18 gene encodes a novel protein affecting the kinetics of acetylcholine metabolism in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurochem. 1992;58:1517–1525. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb11373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn R., Scheller R. H. SNAREs–engines for membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:631–643. doi: 10.1038/nrm2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski J. A., Schroeder T. J., Holz R. W., Wightman R. M. Quantal secretion of catecholamines measured from individual bovine adrenal medullary cells permeabilized with digitonin. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:18329–18335. doi: 10.21236/ada251716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapfhamer D., Bettinger J. C., Davies A. G., Eastman C. L., Smail E. A., Heberlein U., McIntire S. L. Loss of RAB-3/A in C. elegans and the mouse affects behavioral response to ethanol. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:669–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khvotchev M., Dulubova I., Sun J., Dai H., Rizo J., Sudhof T. C. Dual modes of Munc18-1/SNARE interactions are coupled by functionally critical binding to syntaxin-1 N terminus. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:12147–12155. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3655-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner M. R., Nurrish S. J., Kaplan J. M. Facilitation of synaptic transmission by EGL-30 Gqalpha and EGL-8 PLCbeta: DAG binding to UNC-13 is required to stimulate acetylcholine release. Neuron. 1999;24:335–346. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80848-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney T. R., Luo S., Nonet M. L. Analysis of synaptic transmission in Caenorhabditis elegans using an aldicarb-sensitivity assay. Nat. Protocols. 2006;1:1772–1777. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medine C. N., Rickman C., Chamberlain L. H., Duncan R. R. Munc18-1 prevents the formation of ectopic SNARE complexes in living cells. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:4407–4415. doi: 10.1242/jcs.020230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C. C., Kramer J. M., Stinchcomb D., Ambros V. Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 1991;10:3959–3970. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz L. B., Dasgupta N., Liu C., Hunt S. J., Crowder C. M. An evolutionarily conserved presynaptic protein is required for isoflurane sensitivity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:971–982. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000291451.49034.b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller K. G., Emerson M. D., Rand J. B. Goalpha and diacylglycerol kinase negatively regulate the Gqalpha pathway in C. elegans. Neuron. 1999;24:323–333. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80847-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misura K.M.S., Scheller R. H., Weis W. I. Three-dimensional structure of the neuronal-Sec1-syntaxin 1a complex. Nature. 2000;404:355–362. doi: 10.1038/35006120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P. H., Bull K., Glautier S., Hopper N. A., Holden-Dye L., O'Connor V. The concentration-dependent effects of ethanol on Caenorhabditis elegans behaviour. Pharmacogenomics J. 2007;7:411–417. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan P. G., Sedensky M. M. Mutations affecting sensitivity to ethanol in the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1995;19:1423–1429. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neco P., Fernandez-Peruchena C., Navas S., Gutierrez L. M., de Toledo G. A., Ales E. Myosin II contributes to fusion pore expansion during exocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:10949–10957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709058200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick P., Schekman R. Secretion and cell-surface growth are blocked in a temperature-sensitive mutant of saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1979;76:1858–1862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurrish S. J. An overview of C. elegans trafficking mutants. Traffic. 2002;3:2–10. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.30102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offenhauser N., et al. Increased ethanol resistance and consumption in Eps8 knockout mice correlates with altered actin dynamics. Cell. 2006;127:213–226. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M., Sudhof T. C. Mints, munc18-interacting proteins in synaptic vesicle exocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:31459–31464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabst S., Hazzard J. W., Antonin W., Sudhof T. C., Jahn R., Rizo J., Fasshauer D. Selective interaction of complexin with the neuronal SNARE complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:19808–19818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002571200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer Z. J., et al. S-nitrosylation of syntaxin 1 at Cys(145) is a regulatory switch controlling Munc18-1 binding. Biochem. J. 2008;413:479–491. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng R., Gallwitz D. Multiple SNARE interactions of an SM protein: Sed5p/Sly1p binding is dispensable for transport. EMBO J. 2004 doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pothos E. N., Mosharov E., Liu K.-P., Setlik W., Haburcak M., Baldini G., Gershon M. D., Tamir H., Sulzer D. Stimulation-dependent regulation of the pH, volume and quantal size of bovine and rodent secretory vesicles. J. Physiol. 542. 2002;2:453–476. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.018630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajgopal Y., Vemuri M. C. Ethanol induced changes in cyclin-dependent kinase-5 activity and its activators, P35, P67 (Munc-18) in rat brain. Neurosci. Lett. 2001;308:173–176. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond J. E., Weimer R. M., Jorgensen E. M. An open form of syntaxin bypasses the requirement for UNC-13 in vesicle priming. Nature. 2001;412:338–341. doi: 10.1038/35085583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickman C., Medine C. N., Bergmann A., Duncan R. R. Functionally and spatially distinct modes of Munc18-syntaxin 1 interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:12097–12103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700227200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenfluh A., Threlkeld R. J., Bainton R. J., Tsai L.T.-Y., Lasek A. W., Heberlein U. Distinct behavioral responses to ethanol are regulated by alternate RhoGAP18B isoforms. Cell. 2006;127:199–211. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassa T., Harada S.-I., Ogawa H., Rand J. B., Maruyama I. N., Hosono R. Regulation of the UNC-18-Caenorhabditis elegans syntaxin complex by UNC-13. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:4772–4777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-04772.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit M. A., Smith T. L., Kalmijn J. The search for genes contributing to the low level of response to alcohol: patterns of findings across studies. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2004;28:1449–1458. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000141637.01925.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze K. L., Littleton J. T., Salzberg A., Halachmi N., Stern M., Lev Z., Bellen H. J. rop, a Drosophila homolog of yeast sec1 and vertebrate n-sec1/munc 18 proteins, is a negative regulator of neurotransmitter release in vivo. Neuron. 1994;13:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott B. L., Van Komen J. S., Irshad H., Liu S., Wilson K. A., McNew J. A. Sec1p directly stimulates SNARE-mediated membrane fusion in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 2004;167:75–85. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Tareste D. C., Paumet F., Rothman J. E., Melia T. J. Selective activation of cognate SNAREpins by Sec1/Munc18 (SM) proteins. Cell. 2007;128:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieburth D., Madison J. M., Kaplan J. M. PKC-1 regulates secretion of neuropeptides. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:49–57. doi: 10.1038/nn1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siggins G. R., Roberto M., Nie Z. The tipsy terminal: presynaptic effects of ethanol. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005;107:80–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sombers L. A., Hanchar H. J., Colliver T. L., Wittenberg N., Cans A., Arbault S., Amatore C., Ewing A. G. The effects of vesicular volume on secretion through the fusion pore in exocytotic release from PC12 cells. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:303–309. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1119-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toonen R.F.G., de Vries K. J., Zalm R., Sudhof T. C., Verhage M. Munc18-1 stabilizes syntaxin 1, but is not essential for syntaxin 1 targeting and SNARE complex formation. J. Neurochem. 2005;93:1393–1400. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis E. R., Wightman R. M. Spatio-temporal resolution of exocytosis from individual cells. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1998;27:77–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Swinderen B., Saifee O., Shebester L., Roberson R., Nonet M. L., Crowder C. M. A neomorphic syntaxin mutation blocks volatile-anesthetic action in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:2479–2484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets T., Toonen R., Brian E. C., de Wit H., Moser T., Rettig J., Sudhof T. C., Neher E., Verhage M. Munc-18 promotes large dense-core vesicle docking. Neuron. 2001;31:581–591. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00391-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]