Abstract

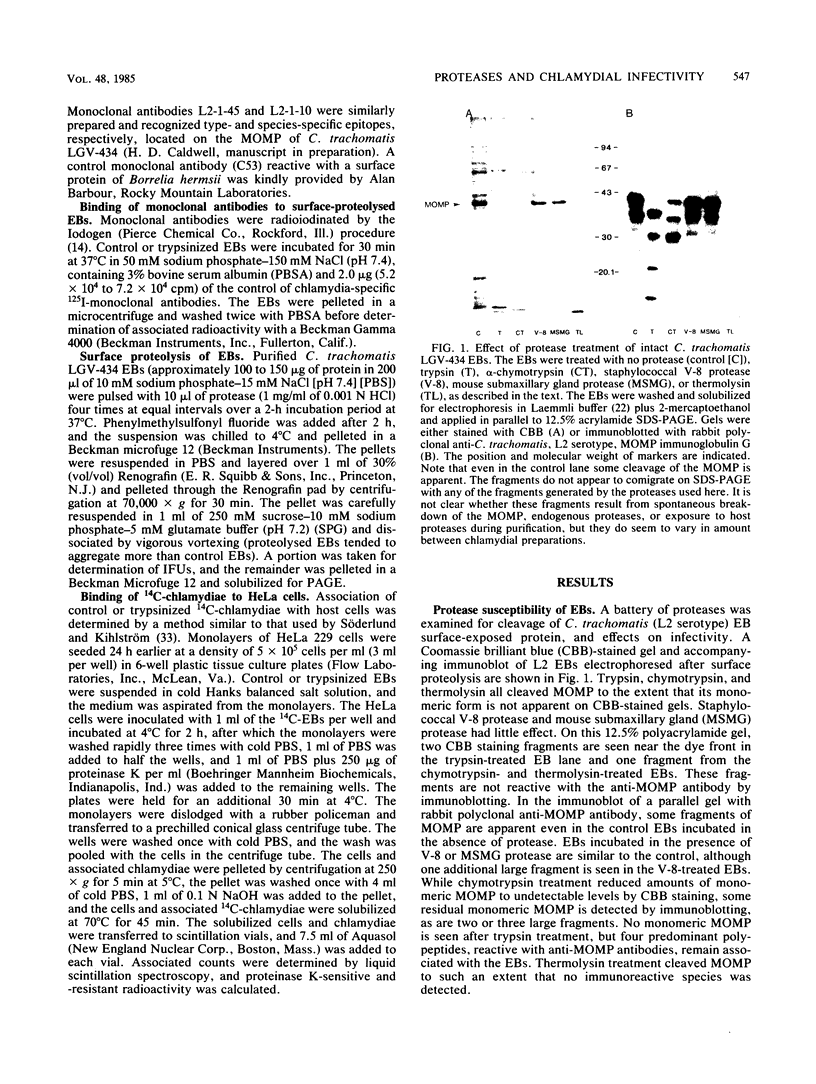

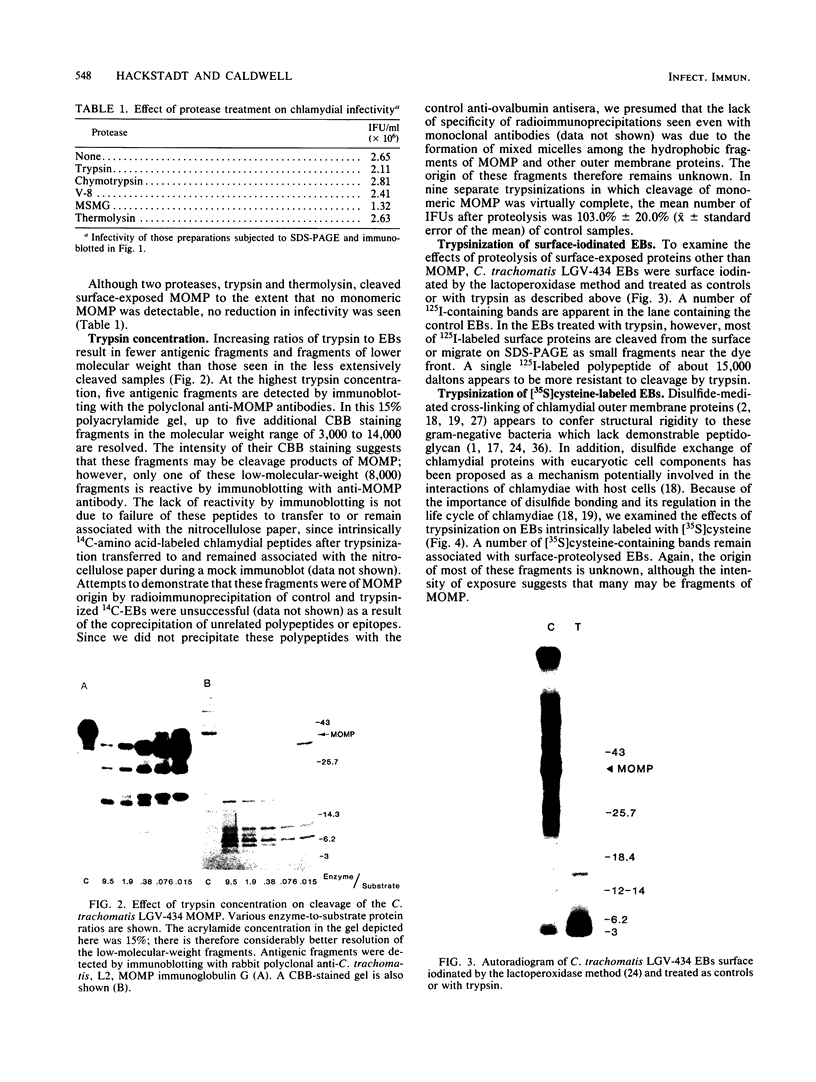

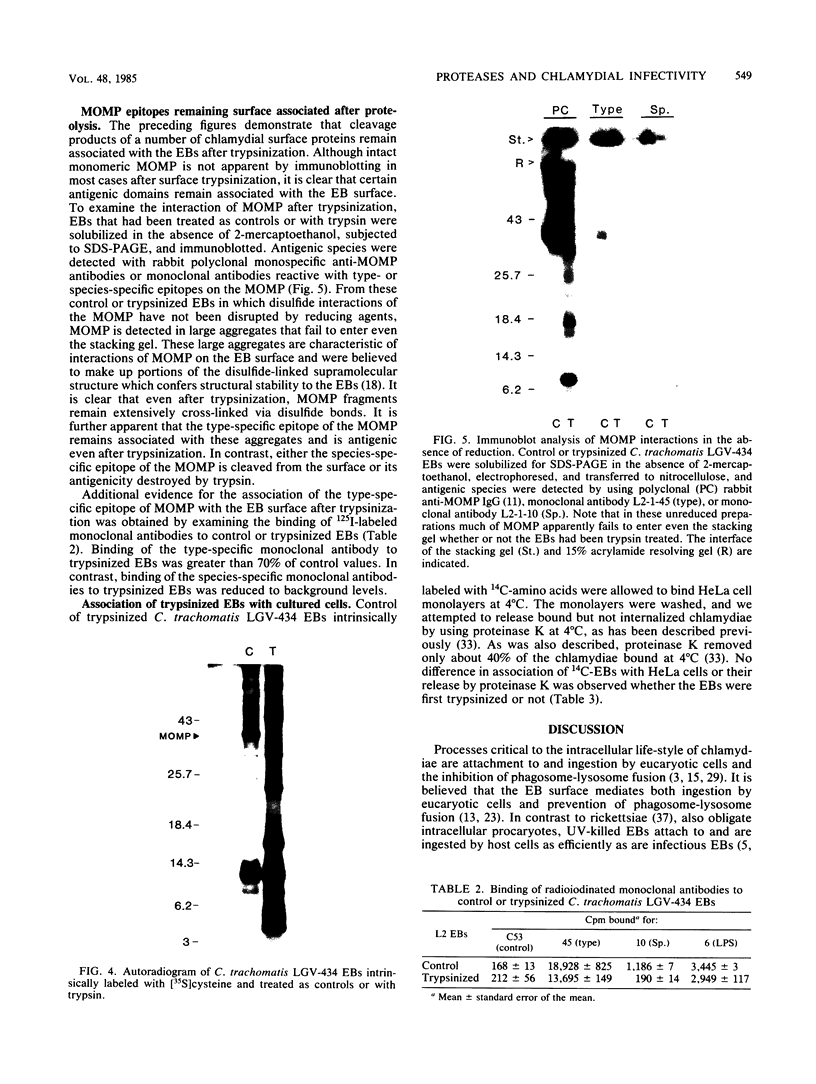

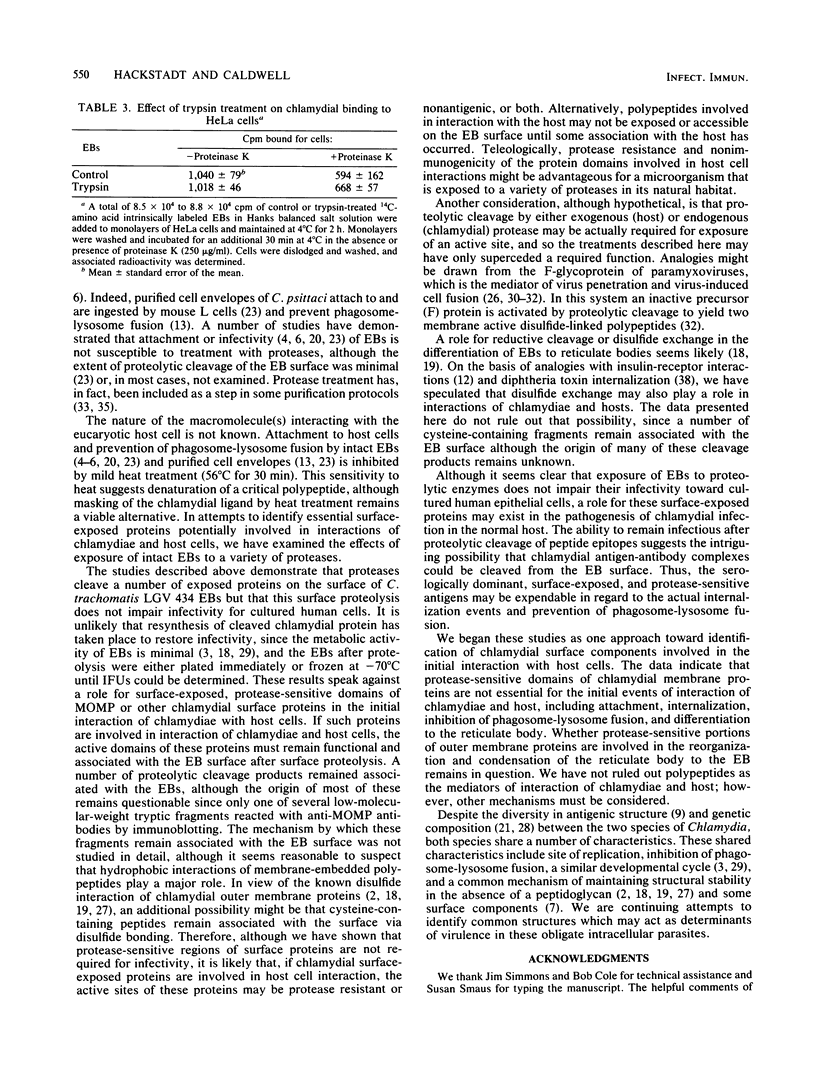

The proteolytic cleavage of Chlamydia trachomatis LGV-434 surface proteins and resultant effects on infectivity and association with cultured human epithelial (HeLa) cells have been examined. Of several proteases examined, trypsin, chymotrypsin, and thermolysin extensively cleaved the chlamydial major outer membrane protein (MOMP). Two proteases, trypsin and thermolysin, cleaved the MOMP to the extent that monomeric MOMP was not detectable by immunoblotting with monospecific polyclonal antibodies. In the case of thermolysin, not even antigenic fragments were detected. Surprisingly, infectivity toward HeLa cells was not diminished. In addition, the association of intrinsically 14C-radiolabeled elementary bodies (EBs) with HeLa cells or their dissociation by proteinase K was not measurably affected by prior trypsinization of the EBs. Trypsinization of lactoperoxidase surface-iodinated elementary bodies demonstrated that most of the 125I-labeled surface proteins were cleaved. In all cases, however, a number of proteolytic cleavage fragments remained associated with the EB surface after surface proteolysis. When trypsinized EBs were electrophoresed under nonreducing conditions and immunoblotted with either polyclonal or type-specific monoclonal MOMP antibodies, MOMP was found in a large oligomeric form that failed to enter the polyacrylamide stacking gel. Additionally, trypsinized viable EBs bound radioiodinated type-specific MOMP monoclonal antibody as efficiently as did the control nontrypsinized organisms. Taken together, the findings indicate that although the MOMP is highly susceptible to surface proteolysis, the supramolecular structure of the protein on the EB surface is apparently maintained by disulfide interactions. Thus, if surface-exposed chlamydial proteins are involved in the initial interaction of chlamydiae with eucaryotic cells, the functional domains of these proteins which mediate this interaction must be resistant to proteolysis and remain associated with the EB surface.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barbour A. G., Amano K., Hackstadt T., Perry L., Caldwell H. D. Chlamydia trachomatis has penicillin-binding proteins but not detectable muramic acid. J Bacteriol. 1982 Jul;151(1):420–428. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.1.420-428.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavoil P., Ohlin A., Schachter J. Role of disulfide bonding in outer membrane structure and permeability in Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1984 May;44(2):479–485. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.2.479-485.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker Y. The chlamydia: molecular biology of procaryotic obligate parasites of eucaryocytes. Microbiol Rev. 1978 Jun;42(2):274–306. doi: 10.1128/mr.42.2.274-306.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose S. K., Paul R. G. Purification of Chlamydia trachomatis lymphogranuloma venereum elementary bodies and their interaction with HeLa cells. J Gen Microbiol. 1982 Jun;128(6):1371–1379. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-6-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne G. I., Moulder J. W. Parasite-specified phagocytosis of Chlamydia psittaci and Chlamydia trachomatis by L and HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 1978 Feb;19(2):598–606. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.2.598-606.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne G. I. Requirements for ingestion of Chlamydia psittaci by mouse fibroblasts (L cells). Infect Immun. 1976 Sep;14(3):645–651. doi: 10.1128/iai.14.3.645-651.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell H. D., Hitchcock P. J. Monoclonal antibody against a genus-specific antigen of Chlamydia species: location of the epitope on chlamydial lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1984 May;44(2):306–314. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.2.306-314.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell H. D., Kromhout J., Schachter J. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1981 Mar;31(3):1161–1176. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.3.1161-1176.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell H. D., Kuo C. C., Kenny G. E. Antigenic analysis of Chlamydiae by two-dimensional immunoelectrophoresis. I. Antigenic heterogeneity between C. trachomatis and C. psittaci. J Immunol. 1975 Oct;115(4):963–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell H. D., Perry L. J. Neutralization of Chlamydia trachomatis infectivity with antibodies to the major outer membrane protein. Infect Immun. 1982 Nov;38(2):745–754. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.2.745-754.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell H. D., Schachter J. Antigenic analysis of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia spp. Infect Immun. 1982 Mar;35(3):1024–1031. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.3.1024-1031.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S., Harrison L. C. Insulin binding leads to the formation of covalent (-S-S-) hormone receptor complexes. J Biol Chem. 1982 Oct 25;257(20):12239–12244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg L. G., Wyrick P. B., Davis C. H., Rumpp J. W. Chlamydia psittaci elementary body envelopes: ingestion and inhibition of phagolysosome fusion. Infect Immun. 1983 May;40(2):741–751. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.2.741-751.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FURNESS G., GRAHAM D. M., REEVE P. The titration of trachoma and inclusion blennorrhoea viruses in cell cultures. J Gen Microbiol. 1960 Dec;23:613–619. doi: 10.1099/00221287-23-3-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraker P. J., Speck J. C., Jr Protein and cell membrane iodinations with a sparingly soluble chloroamide, 1,3,4,6-tetrachloro-3a,6a-diphrenylglycoluril. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1978 Feb 28;80(4):849–857. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friis R. R. Interaction of L cells and Chlamydia psittaci: entry of the parasite and host responses to its development. J Bacteriol. 1972 May;110(2):706–721. doi: 10.1128/jb.110.2.706-721.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett A. J., Harrison M. J., Manire G. P. A search for the bacterial mucopeptide component, muramic acid, in Chlamydia. J Gen Microbiol. 1974 Jan;80(1):315–318. doi: 10.1099/00221287-80-1-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackstadt T., Todd W. J., Caldwell H. D. Disulfide-mediated interactions of the chlamydial major outer membrane protein: role in the differentiation of chlamydiae? J Bacteriol. 1985 Jan;161(1):25–31. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.1.25-31.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch T. P., Allan I., Pearce J. H. Structural and polypeptide differences between envelopes of infective and reproductive life cycle forms of Chlamydia spp. J Bacteriol. 1984 Jan;157(1):13–20. doi: 10.1128/jb.157.1.13-20.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch T. P., Vance D. W., Jr, Al-Hossainy E. Attachment of Chlamydia psittaci to formaldehyde-fixed and unfixed L cells. J Gen Microbiol. 1981 Aug;125(2):273–283. doi: 10.1099/00221287-125-2-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsbury D. T., Weiss E. Lack of deoxyribonucleic acid homology between species of the genus Chlamydia. J Bacteriol. 1968 Oct;96(4):1421–1423. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.4.1421-1423.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy N. J., Moulder J. W. Attachment of cell walls of Chlamydia psittaci to mouse fibroblasts (L cells). Infect Immun. 1982 Sep;37(3):1059–1065. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.3.1059-1065.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manire G. P., Tamura A. Preparation and chemical composition of the cell walls of mature infectious dense forms of meningopneumonitis organisms. J Bacteriol. 1967 Oct;94(4):1178–1183. doi: 10.1128/jb.94.4.1178-1183.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison M. The determination of the exposed proteins on membranes by the use of lactoperoxidase. Methods Enzymol. 1974;32:103–109. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(74)32013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai Y., Ogura H., Klenk H. Studies on the assembly of the envelope of Newcastle disease virus. Virology. 1976 Feb;69(2):523–538. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(76)90482-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhall W. J., Jones R. B. Disulfide-linked oligomers of the major outer membrane protein of chlamydiae. J Bacteriol. 1983 May;154(2):998–1001. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.2.998-1001.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson E. M., de la Maza L. M. Characterization of Chlamydia DNA by restriction endonuclease cleavage. Infect Immun. 1983 Aug;41(2):604–608. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.2.604-608.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter J., Caldwell H. D. Chlamydiae. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1980;34:285–309. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.34.100180.001441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheid A., Choppin P. W. Identification of biological activities of paramyxovirus glycoproteins. Activation of cell fusion, hemolysis, and infectivity of proteolytic cleavage of an inactive precursor protein of Sendai virus. Virology. 1974 Feb;57(2):475–490. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(74)90187-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheid A., Choppin P. W. Protease activation mutants of sendai virus. Activation of biological properties by specific proteases. Virology. 1976 Jan;69(1):265–277. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(76)90213-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheid A., Choppin P. W. Two disulfide-linked polypeptide chains constitute the active F protein of paramyxoviruses. Virology. 1977 Jul 1;80(1):54–66. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(77)90380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens R. S., Tam M. R., Kuo C. C., Nowinski R. C. Monoclonal antibodies to Chlamydia trachomatis: antibody specificities and antigen characterization. J Immunol. 1982 Mar;128(3):1083–1089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderlund G., Kihlström E. Effect of methylamine and monodansylcadaverine on the susceptibility of McCoy cells to Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Infect Immun. 1983 May;40(2):534–541. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.2.534-541.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAMURA A., HIGASHI N. PURIFICATION AND CHEMICAL COMPOSITION OF MENINGOPNEUMONITIS VIRUS. Virology. 1963 Aug;20:596–604. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(63)90284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura A., Manire G. P. Preparation and chemical composition of the cell membranes of developmental reticulate forms of meningopneumonitis organisms. J Bacteriol. 1967 Oct;94(4):1184–1188. doi: 10.1128/jb.94.4.1184-1188.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker T. S., Winkler H. H. Penetration of cultured mouse fibroblasts (L cells) by Rickettsia prowazeki. Infect Immun. 1978 Oct;22(1):200–208. doi: 10.1128/iai.22.1.200-208.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright H. T., Marston A. W., Goldstein D. J. A functional role for cysteine disulfides in the transmembrane transport of diphtheria toxin. J Biol Chem. 1984 Feb 10;259(3):1649–1654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]