Abstract

In this report we describe the genomic sequence of guinea pig cytomegalovirus (GPCMV) assembled from a tissue culture-derived bacterial artificial chromosome clone, plasmid clones of viral restriction fragments, and direct PCR sequencing of viral DNA. The GPCMV genome is 232,678 bp, excluding the terminal repeats, and has a GC content of 55%. A total of 105 open reading frames (ORFs) of > 100 amino acids with sequence and/or positional homology to other CMV ORFs were annotated. Positional and sequence homologs of human cytomegalovirus open reading frames UL23 through UL122 were identified. Homology with other cytomegaloviruses was most prominent in the central ~60% of the genome, with divergence of sequence and lack of conserved homologs at the respective genomic termini. Of interest, the GPCMV genome was found in many cases to bear stronger phylogenetic similarity to primate CMVs than to rodent CMVs. The sequence of GPCMV should facilitate vaccine and pathogenesis studies in this model of congenital CMV infection.

Findings

Guinea pig cytomegalovirus (GPCMV) serves as a useful model of congenital infection, due to the ability of the virus to cross the placenta and infect the fetus in utero [1-3]. This model is well-suited to vaccine studies for prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, a major public health problem and a high-priority area for new vaccine development [4]. However, an impediment to studies in this model has been the lack of detailed DNA sequence data. Although a number of reports have identified specific gene products or clusters of genes [5-11], to date a full genomic sequence has not been available.

We recently reported the construction and preliminary sequence map of a GPCMV bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone maintained in E. coli [12,13], and this clone was used as an initial template for sequence analysis of the full GPCMV genome. BAC DNA was purified using Clontech's NucleoBond® Plasmid Kits as described previously [14] and both strands were sequenced using an ABI PRISM® 377 DNA Sequencer, with primers synthesized, as needed, to 'primer-walk' the nucleotide sequence. In parallel, Hind III- and EcoR I-digested fragments were gel-purified and cloned into pUC and pBR322-based vectors as previously described [15]. Plasmid sequences were determined from overlapping Hind III and EcoR I fragments using the map coordinates originally described by Gao and Isom [16]. These sequences were compared to the BAC sequence to facilitate assembly of a full-length contiguous sequence. Since the cloning of the BAC in E. coli involved insertion of BAC origin sequences into the Hind III "N" region of the viral genome, sequence obtained from this specific restriction fragment cloned in pBR322 was utilized for assembly of the final contiguous sequence; analysis of this sequence confirmed that there were no adventitious deletions in the Hind III "N" region generated during the original BAC cloning process. Since a deletion in the Hind III "D" region occurred during cloning of the GPCMV BAC in E. coli [17], DNA sequence from a plasmid containing the full-length Hind III "D" fragment was similarly obtained, and used for assembly of the final contiguous sequence. The GPCMV genomic sequence has been deposited with GenBank (Accession Number FJ355434).

Sequence analysis of GPCMV revealed a genome length of 232,678 bp with a GC content of 55%. This value is in agreement with the value of 54.1% determined previously by CsCl buoyant density centrifugation [18]. A total of 326 open reading frames (ORFs) were identified that were capable of encoding proteins of ≥ 100 amino acids (aa). For ORFs predicted by the sequence analysis that had substantial overlap with other adjacent or complementary GPCMV ORFs that appeared to encode gene products that were highly conserved in other cytomegaloviruses, only those sequences with < 60% overlap with these highly conserved ORFs were further analyzed. ORFs homologous to those encoded by other CMVs with an e-value of < 0.1 and ≥ 100 aa were identified, based on comparisons analyzed using NCBI Blast (blastall version program 2.2.16). Of the ORFs so identified, 104 had sequence and/or positional homology to one or more ORFs encoded by human (HCMV), murine (MCMV), rat (RCMV), rhesus (RhCMV), chimpanzee (CCMV), or tupaia herpesvirus (THV) cytomegaloviruses (Table 1). Of note, homologs of HCMV ORFs UL23 through UL122 were identified [19]. For ease of nomenclature, we have designated these ORFs using upper case font (GP23 through GP122). ORFs with homologs in other CMVs that do not correspond to HCMV UL23 through UL122 have been designated with a lower case "gp" prefix. Homologs of HCMV UL41a (69 aa; gp38.2), UL51 (99 aa; GP51), and UL91 (87 aa; GP91) were annotated in these initial analyses, based primarily on positional, and not sequence, homology to the respective HCMV ORFs. Three ORFs, homologs of MHC class I genes known to be encoded by multiple other CMVs (gp 147–149, Table 1) were also identified. One ORF, gp1 (homolog of CC chemokines), did not have a positional or sequence homolog when compared to other CMVs, but was included in the annotation because of its previous molecular characterization [9]. Including ORFs with mapped exons, the total number of ORFs annotated in this preliminary analysis was 105 [Table 1].

Table 1.

GPCMV Open Reading Frames (ORFs)

| ORF | Strand | Position | Size (aa) | Protein Characteristics and Cytomegalovirus Homologs | |

| From | To | ||||

| gp1 | C | 12701 | 13006 | 101 | GPCMV MIP 1-alpha; homology to multiple CC chemokines |

| gp2 | 15098 | 15949 | 283 | Homology to MCMV M69a | |

| gp3 | C | 17461 | 19827 | 788 | Homology to THV T5b; US22 superfamily |

| gp4 | C | 21093 | 21416 | 107 | Homology to RCMV r136d |

| gp5 | C | 26985 | 28097 | 370 | Homology to MCMV m32a |

| gp6 | 30089 | 30454 | 121 | Homology to MCMV glycoprotein family m02a | |

| gp7 | C | 32003 | 32308 | 101 | Homology to RhCMV rh42c |

| GP23 | C | 33561 | 34763 | 400 | UL23 homolog; US22 gene superfamily |

| GP24 | C | 35000 | 36217 | 405 | UL24 homolog; US22 superfamily |

| gp24.1 | 36802 | 37224 | 140 | Homology to MCMV M34 proteina | |

| GP25 | 37187 | 38455 | 422 | UL25 homolog; tegument protein | |

| GP26 | C | 38621 | 39058 | 145 | UL26 homolog |

| GP27 | C | 39508 | 41472 | 654 | UL27 homolog |

| GP28 | C | 41572 | 42639 | 355 | UL28 homolog; US22 superfamily |

| GP28.1 | C | 43344 | 44546 | 400 | UL28 homolog; US22 superfamily |

| GP28.2 | C | 44912 | 46099 | 395 | UL28 homolog; US22 superfamily |

| GP29 | C | 46211 | 46882 | 223 | UL29 homolog; US22 superfamily |

| gp29.1 | C | 47579 | 48034 | 151 | Homology to RCMV R36 proteind; potential homolog of viral cell death suppressor |

| GP30 | C | 49363 | 51060 | 565 | UL30 homolog |

| GP31 | 51354 | 52832 | 492 | UL31 homolog | |

| GP32 | C | 53073 | 54626 | 518 | UL32 homolog |

| GP33 | 54846 | 56129 | 427 | UL33 homolog; 7-TMR GPCR superfamily | |

| GP34 | 56482 | 58065 | 527 | UL34 homolog | |

| GP35 | 58269 | 59927 | 552 | UL35 homolog | |

| GP37 | C | 60047 | 60964 | 305 | UL37 homolog |

| GP38 | C | 61321 | 62385 | 354 | UL38 homolog |

| gp38.1 | C | 62960 | 63817 | 436 | Positional homolog of HCMV UL40 |

| gp38.2 | C | 63876 | 65186 | 69 | Positional homolog of HCMV UL41a |

| gp38.3 | C | 65881 | 66735 | 284 | Positional homolog of HCMV UL42 |

| gp38.4 | C | 67254 | 67619 | 121 | Homology to RCMV r42d |

| GP43 | C | 68208 | 69221 | 337 | UL43 homolog |

| GP44 | C | 69209 | 70432 | 407 | UL44 homolog |

| GP45 | C | 71144 | 73933 | 929 | UL45 homolog |

| GP46 | C | 74036 | 74833 | 265 | UL46 homolog |

| GP47 | 75441 | 77846 | 801 | UL47 homolog | |

| GP48 | 78051 | 84332 | 2093 | UL48 homolog | |

| GP49 | C | 84746 | 86386 | 546 | UL49 homolog |

| GP50 | C | 86362 | 87426 | 354 | UL50 homolog |

| GP51 | C | 87551 | 87850 | 99 | UL51 homolog; terminase subunit |

| GP52 | 88170 | 89750 | 526 | UL52 homolog | |

| GP53 | 89743 | 90729 | 328 | UL53 homolog | |

| GP54 | C | 90821 | 94174 | 1117 | UL54 homolog; DNA polymerase |

| GP55 | C | 94216 | 96921 | 901 | UL55 homolog; glycoprotein B |

| GP56 | C | 96818 | 99085 | 755 | UL56 homolog; terminase subunit |

| GP57 | C | 99236 | 102919 | 1227 | UL57 homolog |

| gp57.1 | C | 104872 | 105258 | 128 | Homology to RCMV r23.1d |

| gp57.2 | 107338 | 107712 | 124 | Homology to RCMV R53d | |

| GP69 | C | 108547 | 111678 | 1043 | UL69 homolog |

| GP70 | C | 112387 | 115590 | 1067 | UL70 homolog; helicase-primase |

| GP71 | 115589 | 116365 | 258 | UL71 homolog | |

| GP72 | C | 116528 | 117601 | 357 | UL72 homolog; dUTPase |

| GP73 | 117683 | 118084 | 133 | UL73 homolog; glycoprotein N | |

| GP74 | C | 118031 | 119143 | 370 | UL74 homolog; glycoprotein O |

| GP75 | C | 119595 | 121766 | 723 | UL75 homolog; glycoprotein H |

| GP76 | 121931 | 122770 | 279 | UL76 homolog | |

| GP77 | 122484 | 124343 | 619 | UL77 homolog | |

| GP78 | 124725 | 125969 | 414 | UL78 homolog; 7-TMR GPCR superfamily | |

| GP79 | C | 126164 | 127111 | 315 | UL79 homolog |

| GP80 | 126972 | 129281 | 769 | UL80 homolog; CMV protease | |

| GP82 | C | 129576 | 131141 | 521 | UL82 homolog; pp71 |

| GP83 | C | 131361 | 133058 | 565 | UL83 homolog; pp65 |

| GP84 | C | 133286 | 134737 | 483 | UL84 homolog |

| gp84.1 | 134994 | 135476 | 160 | Homolog of RhCMV rh116e | |

| GP85 | C | 135035 | 135946 | 303 | UL85 homolog |

| GP86 | C | 136227 | 140276 | 1349 | UL86 homolog |

| GP87 | 140657 | 143578 | 973 | UL87 homolog | |

| GP88 | 143481 | 144752 | 423 | UL88 homolog | |

| GP89ex2 | C | 144798 | 145928 | 376 | UL89 homolog; terminase subunit, exon 2 |

| GP91 | 146356 | 146619 | 87 | UL91 homolog | |

| GP92 | 146616 | 147245 | 209 | UL92 homolog | |

| GP93 | 147456 | 148985 | 509 | UL93 homolog | |

| GP94 | 149118 | 149873 | 251 | UL94 homolog | |

| GP89ex1 | C | 150285 | 151166 | 291 | UL89 homolog; terminase subunit, exon 1 |

| GP95 | 151284 | 152489 | 401 | UL95 homolog | |

| GP96 | 152722 | 153084 | 120 | UL96 homolog | |

| GP97 | 153164 | 154981 | 605 | UL97 homolog; protein kinase | |

| GP98 | 155001 | 156788 | 595 | UL98 homolog; alkaline nuclease | |

| GP99 | 156701 | 157222 | 173 | UL99 homolog; pp28 | |

| gp99.1 | 157406 | 158020 | 204 | Homology to RCMV r4d | |

| GP100 | C | 157529 | 158578 | 349 | UL100 homolog; glycoprotein M |

| GP102 | 158908 | 161193 | 761 | UL102 homolog | |

| GP103 | C | 161307 | 162104 | 265 | UL103 homolog |

| GP104 | C | 162067 | 164160 | 697 | UL104 homolog; portal |

| GP105 | 164000 | 166783 | 927 | UL105 homolog; helicase-primase | |

| gp105.1 | 176502 | 176894 | 130 | Homology to RhCMV rh55c | |

| GP112ex1 | 177066 | 177839 | 258 | UL112 homolog; replication accessory protein, exon 1 | |

| GP112ex2 | 178403 | 179257 | 284 | UL112/UL113 homolog; replication accessory protein, exon 2 | |

| GP114 | C | 179168 | 180259 | 363 | UL114 homolog; uracil glycosylase |

| GP115 | C | 180325 | 181101 | 258 | UL115 homolog; glycoprotein L |

| GP116 | C | 181146 | 181994 | 282 | Homology to THV t116b; possible functional homolog of UL119; Fc receptor/immunoglobulin binding domains |

| GP117 | C | 182202 | 182777 | 191 | UL117 homolog |

| GP119.1 | C | 185103 | 185591 | 162 | UL119 homolog; homology to MCMV M119.1a |

| GP121 | C | 186635 | 187681 | 348 | UL121 homolog; homology to THV t121.4b |

| GP122 | C | 188292 | 189260 | 322 | UL122 homolog; HCMV IE2; immediate early transactivator |

| gp123 | 195838 | 196893 | 351 | MCMV IE2 homologa; US22 superfamily | |

| gp138 | C | 201275 | 202750 | 491 | Homology to RCMV r138d |

| gp139 | C | 204624 | 206717 | 697 | Homology to THV T5b; US22 superfamily |

| gp140 | 206446 | 206853 | 135 | Homology to CCMV UL132g | |

| gp141 | C | 206977 | 208584 | 535 | Homology to HCMV US23h; US22 superfamily |

| gp142 | C | 208852 | 210546 | 564 | Homology to HCMV US24h; US22 superfamily |

| gp143 | C | 210799 | 212532 | 577 | Homology to THV T5b; US22 superfamily |

| gp144 | C | 213034 | 215328 | 764 | Homology to US26h; US22 gene superfamily |

| gp145 | C | 215601 | 217499 | 632 | Homology to HCMV IRS1/TRS1h; US22 superfamily |

| gp146 | C | 218106 | 219839 | 577 | Homology to HCMV IRS1/TRS1h; US22 superfamily |

| gp147 | C | 223464 | 225026 | 520 | MHC class I homolog |

| gp148 | C | 225938 | 227389 | 483 | MHC class I homolog |

| gp149 | C | 228845 | 230728 | 627 | MHC class I homolog |

a Genbank NC_004065.1

b Genbank NC_004065.1

c Genbank NC_006150.1

d Genbank AF232689.2

e Genbank YP_068209.1

f Genbank AY486477.1

g Genbank NC_003521.1

h Genbank NC_001347

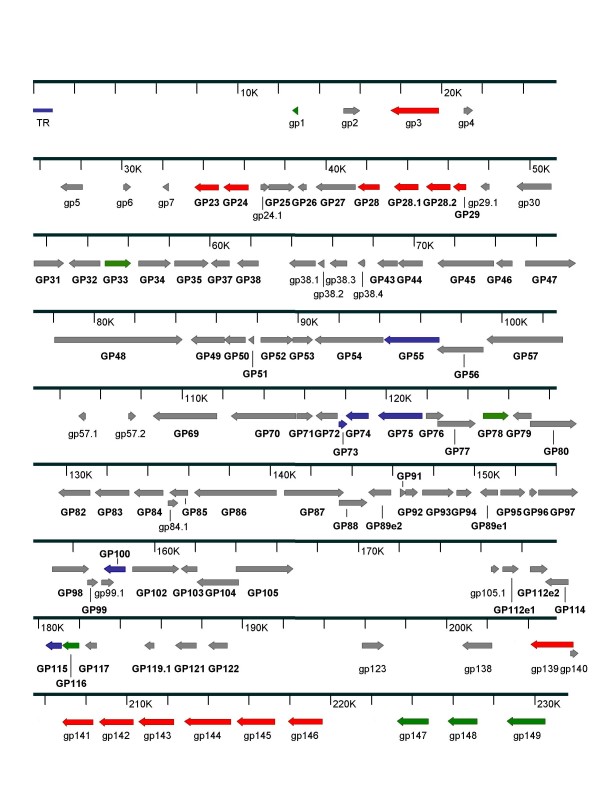

A map of the GPCMV genome illustrating the relative positions of these ORFs is shown in Fig. 1. ORFs that represent homologs of the individual exons of spliced HCMV genes, in particular UL89 (terminase) and UL112/UL113 (replication accessory protein) are annotated separately. The splice junction for the GP89 mRNA was predicted based on comparisons to other CMVs. For the UL112/113 region, further studies will be required to map the precise splicing patterns of the putative transcripts encoded by this region of the GPCMV genome. Similarly, the ORF encoding the sequence homolog of the HCMV IE transactivator, UL122, has been annotated without regard to the splicing events previously shown to take place in this region of the genome [20]; further analyses of cDNA from this and other GPCMV genome regions of IE transcription, including those encoded in the Hind III 'D' region of the genome, will likely result in annotation of multiple heretofore unidentified ORFs. A comprehensive table of all ORFs > 25 aa and their homology to other CMV genomes is provided in additional files 1 and 2. As RNA analyses are completed, the total number of annotated GPCMV ORFs will expand in number.

Figure 1.

Protein Coding Map of GPCMV Genome. Schematic representation of the GPCMV genome demonstrating ORFs described in the text. GPCMV ORFs with positional and/or sequence homology to HCMV ORFs are indicated in bold with upper case prefixes (GP23 through GP122). ORFs that lack sequence or positional homologs in HCMV but share homology with ORFs in other CMVs are indicated with lower case prefixes (see Table 1). Only the 5' terminal repeat (TR) is shown; however, in about 50% of genomes the TR is duplicated at the 3' end [18]. Color-coding indicates ORFs of interest for vaccine and pathogenesis studies: blue, envelope glycoprotein homologs; green, putative immune evasion/immune modulation gene homologs; red, US22 superfamily homologs.

The schematic representation of GPCMV ORFs demonstrated in Fig. 1 highlights several gene families of particular interest. Of particular interest and importance to vaccine studies in the guinea pig model are conserved homologs of the ORFs encoding major envelope glycoproteins gB, gH/gL/gO/, and gM/gN. These glycoproteins are important determinants of humoral immune responses in the setting of CMV infection, and serve as potential subunit vaccine candidates. Of these, the gB homolog has been demonstrated to confer protection against congenital GPCMV infection in subunit vaccine studies [21-23]. Homologs of putative HCMV immune modulation genes, including G-protein coupled receptors and major histocompatibility class I homologs, were also identified [24]. Also of interest was the presence of multiple US22 gene family homologs, heavily clustered near the rightward terminus of the GPCMV genome. These ORFs predict protein products that are analogous to the MCMV dsRNA-binding proteins, M142 and M143, that have been shown to inhibit dsRNA-activated antiviral pathways [25,26]. Members of this family have also been implicated in macrophage tropism in MCMV [27]. Our sequence analysis also confirmed the findings of Liu and Biegalke [8] that the GPCMV genome does not encode a positional homolog of the antiapoptotic HCMV UL36 gene [28]. However, an ORF with homology to R36, which encodes the presumed RCMV cell death suppressor, was identified (gp29.1, Table 1). Further studies will be required to determine whether this putative gene supplies a UL36-like function.

It was also of interest to note the presence of ORFs that have apparent homology to the MCMV M129-133 region. This region has positional homologs in human and primate CMVs [29-31], but is absent in THV [32]. Recently, it was determined that passage of GPCMV in cultured fibroblasts promotes the deletion of a ~1.6-kb locus containing potential positional homologs of this gene cluster. The presence of this 1.6 kb locus was found by Inoue and colleagues to be associated with an enhanced pathogenesis of GPCMV in vivo [33]. We independently confirmed the presence of this locus and its sequence in our salivary gland-derived viral stocks, and have included this sequence in our GenBank annotation (Accession Number FJ355434). Further studies will be required to fully annotate the transcripts encoded by this region of the GPCMV genome. Interestingly, the original GPCMV BAC clone that we sequenced was derived using GPCMV viral DNA obtained after long-term tissue culture passage of ATCC 2122 viral stock, and not surprisingly this BAC was found to lack the 1.6 kb virulence locus [12]. Subsequently, PCR and preliminary sequencing of a more recently obtained GPCMV BAC clone with an excisable origin of replication [17] revealed that the 1.6-kb sequence was retained in this clone. The apparent modifications of this locus that occur following viral passage on fibroblast cells are reminiscent of the mutations and deletions that occurred during fibroblast-passage of HCMV [34] and rhesus CMV [35]. The congruence of these events suggests that the selective pressures that promote mutational inactivation of genes in this region may be similar across viral species. Additional analyses, including sequencing of a full-length GPCMV genome derived from replicating virus in vivo, will be required to determine what other deletions or mutations are present in genomes from tissue culture-passaged viruses. Since additional ORFs are likely to be identified by these analyses, we have annotated the first ORF identified in the BAC sequence to the right of this 1.6 kb region as gp138 (Fig. 1), to allow for ease of nomenclature as ORFs in this virulence locus are better characterized. Application of other genome sequence analysis methods, including identification of small or overlapping genes and further assessment of mRNA splicing or unconventional translation signals, will likely result in identification of other putative ORFs in future studies [36].

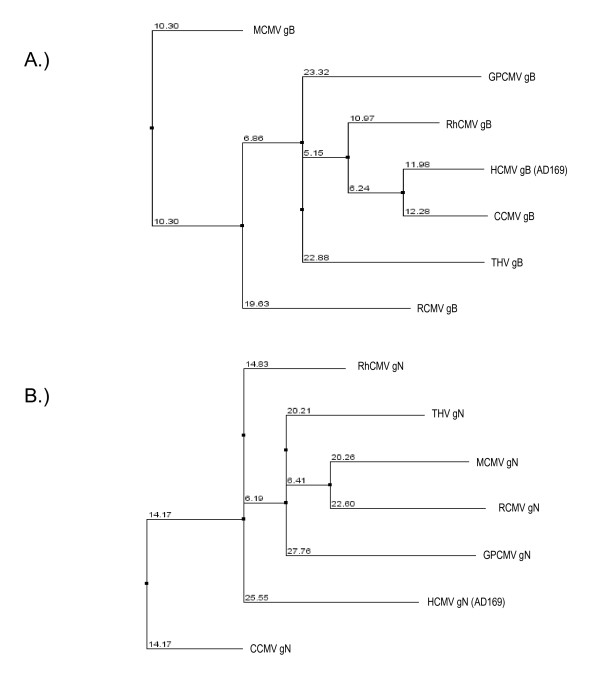

Comparisons of GPCMV ORFs with sequences from other CMV genomes yielded interesting results. ORF translations were compared with all proteins from the 6 sequenced CMV genomes (HCMV, MCMV, RCMV, RhCMV, THV, and CCMV), and hits with e-values less than 1e-5 were aligned individually for each protein, using both ClustalW (version 1.82; [37]) and Muscle (version 3.6; [38]). The alignments were then used to generate trees based on neighbor-joining using JalView. Clustal trees for glycoproteins B (GP55) and N (GP73) are shown in Fig. 2, with distance scores indicated. Overall, comparison of the various glycoproteins (gB, gM, gH, and gO) yielded similar phylogenies, with GPCMV glycoproteins generally appearing closer to primate CMVs than rodent CMVs [39], except for the gN homolog, which appears closer to rodents. ClustalW and Muscle comparisons of GPCMV ORFs with homologous ORFs from the other sequenced CMVs are provided in additional file 3.

Figure 2.

Comparison of GPCMV Glycoproteins with CMV Homologs. Sequences of GPCMV glycoproteins were aligned with glycoproteins from six other CMV genomes (HCMV, MCMV, RCMV, RhCMV, THV, and CCMV) using both ClustalW [37] and Muscle [38] using default parameters. Phylogenetic trees (neighbor joining) were generated from these alignments using Jalview. Numbers at each node indicate mismatch percentages. Interestingly, GPCMV sequences closely match THV sequences (see also, supplementary information), and generally appear closer to primate CMV glycoproteins in pair-wise comparisons than to rodent CMV glycoproteins, as previously observed for gB [39]. Clustal comparisons for conserved glycoproteins gB (GP55; Panel A) and gN (GP73; Panel B) are indicated.

In summary, the complete DNA sequence of GPCMV was determined, using a combination of sequencing of BAC DNA, viral DNA, and cloned Hind III and EcoRI fragments. These analyses identified both conserved ORFs found in all mammalian CMVs, as well as the presence of novel genes apparently unique to the GPCMV. These similarities underscore the usefulness of the guinea pig model, with positive translational implications for development and testing of CMV intervention strategies in humans. Further characterization of the GPCMV genome should facilitate ongoing vaccine and pathogenesis studies in this uniquely useful small animal model of congenital CMV infection.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest. SVD is an employee of Genentech Corporation.

Authors' contributions

MRS cloned viral fragments, performed sequence analysis, analyzed the data and prepared the communication. AM and XC cloned the GPCMV BACs. AM cloned individual genes for sequence analysis. AM, XC and KYC, performed sequence analysis, participated in data analysis, and helped in preparation of the communication. MAM cloned viral DNA fragments, performed sequence analysis, participated in BAC cloning, and aided in preparation of the communication. SVD performed comparative genomic analyses and comparisons and aided in the preparation of the communication.

Supplementary Material

ORFs of ≥ 25 aa (tab A). 50 aa (tab B), or 100 aa (tab C) with Blast analysis against other sequenced CMV genomes; e-value cutoff of 0.1.

ORFs of ≥ 25 aa (tab A). 50 aa (tab B), or 100 aa (tab C) with Blast analysis against other sequenced CMV genomes; e-value cutoff of 1e-5.

Phylogenetic trees for glycoproteins gB, gH, gO, gL, gM and gN, IRS 1–3 family, and GP116 (functional homolog of UL119; Fc receptor/immunoglobulin binding domains). Alignments generated using both ClustalW and Muscle, as described in the text.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Grant support was provided from NIH HD044864-01 and HD38416-01 (to MRS) and R01AI46668 (to MAM). The authors acknowledge helpful discussions and input from Becket Feierbach (Genentech, Inc.). The authors also acknowledge the technical contributions of Yonggen Song and the gift of the Hind III "D" plasmid from HC Isom, Penn State University.

Contributor Information

Mark R Schleiss, Email: schleiss@umn.edu.

Alistair McGregor, Email: mcgre077@umn.edu.

K Yeon Choi, Email: choix207@umn.edu.

Shailesh V Date, Email: date.shailesh@gene.com.

Xiaohong Cui, Email: xcui@vcu.edu.

Michael A McVoy, Email: mmcvoy@vcu.edu.

References

- Kern ER. Pivotal role of animal models in the development of new therapies for cytomegalovirus infections. Antiviral Res. 2006;71:164–71. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleiss MR. Animal models of congenital cytomegalovirus infection: an overview of progress in the characterization of guinea pig cytomegalovirus (GPCMV) J Clin Virol. 2002;25:S37–49. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(02)00100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleiss MR. Comparison of vaccine strategies against congenital CMV infection in the guinea pig model. J Clin Virol. 2008;41:224–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleiss MR. Cytomegalovirus vaccine development. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:361–82. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVoy MA, Nixon DE, Adler SP. Circularization and cleavage of guinea pig cytomegalovirus genomes. J Virol. 1997;71:4209–17. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4209-4217.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox DS, Schleiss MR. Sequence and transcriptional analysis of the guinea pig cytomegalovirus UL97 homolog. Virus Genes. 1997;15:255–64. doi: 10.1023/a:1007988705909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleiss MR, McGregor A, Jensen NJ, Erdem G, Aktan L. Molecular characterization of the guinea pig cytomegalovirus UL83 (pp65) protein homolog. Virus Genes. 1999;19:205–221. doi: 10.1023/a:1008136714136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Biegalke BJ. Characterization of a cluster of late genes of guinea pig cytomegalovirus. Virus Genes. 2001;23:247–56. doi: 10.1023/a:1012536804190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggerty SM, Schleiss MR. A novel CC-chemokine homolog encoded by guinea pig cytomegalovirus. Virus Genes. 2002;25:271–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1020923924471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor A, Liu F, Schleiss MR. Identification of essential and non-essential genes of the guinea pig cytomegalovirus (GPCMV) genome via transposome mutagenesis of an infectious BAC clone. Virus Res. 2004;101:101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2003.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paglino JC, Brady RC, Schleiss MR. Molecular characterization of the guinea-pig cytomegalovirus glycoprotein L gene. Arch Virol. 1999;144:447–62. doi: 10.1007/s007050050517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor A, Schleiss MR. Molecular cloning of the guinea pig cytomegalovirus (GPCMV) genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) in Escherichia coli. Mol Genet Metab. 2001;72:15–26. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleiss MR, Lacayo J. The Guinea-Pig Model of Congenital CMV Infection. In: Reddehase MJ, Lemmermann N, editor. Cytomegaloviruses: Molecular Biology and Immunology. Horizon Scientific Press; 2006. pp. 525–50. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor A, Liu F, Schleiss MR. Molecular, biological, and in vivo characterization of the guinea pig cytomegalovirus (CMV) homologs of the human CMV matrix proteins pp71 (UL82) and pp65 (UL83) J Virol. 2004;78:9872–89. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.18.9872-9889.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleiss MR. Cloning and characterization of the guinea pig cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B gene. Virology. 1994;202:173–85. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Isom HC. Characterization of the guinea pig cytomegalovirus genome by molecular cloning and physical mapping. J Virol. 1984;52:436–47. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.2.436-447.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X, McGregor A, Schleiss MR, McVoy MA. Cloning the complete guinea pig cytomegalovirus genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome with excisable origin of replication. J Virol Methods. 2008;149:231–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isom HC, Gao M, Wigdahl B. Characterization of guinea pig cytomegalovirus DNA. J Virol. 1984;49:426–36. doi: 10.1128/jvi.49.2.426-436.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chee MS, Bankier AT, Beck S, Bohni R, Brown CM, Cerny R, Horsnell T, Hutchison CA, 3rd, Kouzarides T, Martignetti JA, et al. Analysis of the protein-coding content of the sequence of human cytomegalovirus strain AD169. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;154:125–69. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74980-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin CY, Gao M, Isom HC. Guinea pig cytomegalovirus immediate-early transcription. J Virol. 1990;64:1537–48. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.4.1537-1548.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne N, Schleiss MR, Bravo FJ, Bernstein DI. Preconception immunization with a cytomegalovirus (CMV) glycoprotein vaccine improves pregnancy outcome in a guinea pig model of congenital CMV infection. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:59–64. doi: 10.1086/317654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleiss MR, Bourne N, Bernstein DI. Preconception vaccination with a glycoprotein B (gB) DNA vaccine protects against cytomegalovirus (CMV) transmission in the guinea pig model of congenital CMV infection. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1868–74. doi: 10.1086/379839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleiss MR, Bourne N, Stroup G, Bravo FJ, Jensen NJ, Bernstein DI. Protection against congenital cytomegalovirus infection and disease in guinea pigs, conferred by a purified recombinant glycoprotein B vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1374–81. doi: 10.1086/382751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers C, DeFilippis V, Malouli D, Früh K. Cytomegalovirus immune evasion. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:333–59. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valchanova RS, Picard-Maureau M, Budt M, Brune W. Murine cytomegalovirus m142 and m143 are both required to block protein kinase R-mediated shutdown of protein synthesis. J Virol. 2006;80:10181–90. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00908-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child SJ, Hanson LK, Brown CE, Janzen DM, Geballe AP. Double-stranded RNA binding by a heterodimeric complex of murine cytomegalovirus m142 and m143 proteins. J Virol. 2006;80:10173–80. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00905-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ménard C, Wagner M, Ruzsics Z, Holak K, Brune W, Campbell AE, Koszinowski UH. Role of murine cytomegalovirus US22 gene family members in replication in macrophages. J Virol. 2003;77:5557–70. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.10.5557-5570.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaletskaya A, Bartle LM, Chittenden T, McCormick AL, Mocarski ES, Goldmacher VS. A cytomegalovirus-encoded inhibitor of apoptosis that suppresses caspase-8 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:7829–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141108798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagenaur LA, Manning WC, Vieira J, Martens CL, Mocarski ES. Structure and function of the murine cytomegalovirus sgg1 gene: a determinant of viral growth in salivary gland acinar cells. J Virol. 1994;68:7717–7727. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7717-7727.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan A, Cunningham C, Hector RD, Hassan-Walker AF, Lee L, Addison C, Dargan DJ, McGeoch DJ, Gatherer D, Emery VC, Griffiths PD, Sinzger C, McSharry BP, Wilkinson GW, Davison AJ. Genetic content of wild-type human cytomegalovirus. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:1301–1312. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.79888-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckman BJ, Rainish BL, Chase MC, Borton JA, Nelson JA, Jarvis MA, Johnson DC. Characterization of the human cytomegalovirus gH/gL/UL128-131 complex that mediates entry into epithelial and endothelial cells. J Virol. 2008;82:60–70. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01910-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahr U, Darai G. Analysis and characterization of the complete genome of tupaia (tree shrew) herpesvirus. J Virol. 2001;75:4854–70. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.10.4854-4870.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa N, Yamamoto Y, Fukui Y, Katano H, Tsutsui Y, Sato Y, Yamada S, Inami Y, Nakamura K, Yokoi M, Kurane I, Inoue N. Identification of a 1.6 kb genome locus of guinea pig cytomegalovirus required for efficient viral growth in animals but not in cell culture. Virology. 2008;379:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha TA, Tom E, Kemble GW, Duke GM, Mocarski ES, Spaete RR. Human cytomegalovirus clinical isolates carry at least 19 genes not found in laboratory strains. J Virol. 1996;70:78–83. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.78-83.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford KL, Eberhardt MK, Yang KW, Strelow L, Kelly S, Zhou SS, Barry PA. Protein coding content of the ULb' region of wild-type rhesus cytomegalovirus. Virology. 2008;373:181–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocchieri L, Kledal TN, Karlin S, Mocarski ES. Predicting coding potential from genome sequence: application to betaherpesviruses infecting rats and mice. J Virol. 2005;79:7570–96. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7570-7596.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenna R, Sugawara H, Koike T, Lopez R, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG, Thompson JD. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Research. 2003;31:3497–3500. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuken E, Slobbe R, Bruggeman CA, Vink C. Cloning and sequence analysis of the genes encoding DNA polymerase, glycoprotein B, ICP18.5 and major DNA-binding protein of rat cytomegalovirus. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1559–62. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-7-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ORFs of ≥ 25 aa (tab A). 50 aa (tab B), or 100 aa (tab C) with Blast analysis against other sequenced CMV genomes; e-value cutoff of 0.1.

ORFs of ≥ 25 aa (tab A). 50 aa (tab B), or 100 aa (tab C) with Blast analysis against other sequenced CMV genomes; e-value cutoff of 1e-5.

Phylogenetic trees for glycoproteins gB, gH, gO, gL, gM and gN, IRS 1–3 family, and GP116 (functional homolog of UL119; Fc receptor/immunoglobulin binding domains). Alignments generated using both ClustalW and Muscle, as described in the text.