Abstract

The replication and transcription activator (RTA) of gamma-2 herpesvirus is sufficient to drive the entire virus lytic cycle. Hence, the control of RTA activity should play an important role in the maintenance of viral latency. Here, we demonstrate that cellular poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) and Ste20-like kinase hKFC interact with the serine/threonine-rich region of gamma-2 herpesvirus RTA and that these interactions efficiently transfer poly(ADP-ribose) and phosphate units to RTA. Consequently, these modifications strongly repressed RTA-mediated transcriptional activation by inhibiting its recruitment onto the promoters of virus lytic genes. Conversely, the genetic ablation of PARP-1 and hKFC interaction or the knockout of the PARP-1 gene and activity considerably enhanced gamma-2 herpesvirus lytic replication. Thus, this is the first demonstration that cellular PARP-1 and hKFC act as molecular sensors to regulate RTA activity and thereby, herpesvirus latency.

Regulation of cellular gene expression requires not only carefully choreographed binding by multiple transcription cofactors but also various posttranslational modifications that regulate the activity of promoter-specific transcription factors. The important role of phosphorylation in regulating transcription factor activity is now well established. In the past few years, it has become evident that a diverse array of posttranslational modifications, including acetylation, ubiquitination, sumoylation, and ADP-ribosylation, plays an important role in the regulation of transcription factor activity. These modifications lead to the alteration in stability, DNA binding activity, and cofactor recruitment of transcription factors, which ultimately fine-tunes the control of transcription in response to extracellular stimuli.

Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation has been shown to be one of the major regulatory mechanisms to control DNA repair and transcription. A nuclear 110-kDa poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) has been shown to be a multifunctional protein participating in the regulation of both DNA repair and transcription (2, 14). It specifically recognizes and binds to DNA single-strand breaks, and this binding activates the PARP-1 to synthesize polymers of ADP-ribose from NAD (NAD+) and transfer them to specific acceptor proteins for DNA repair. While it is still elusive, PARP-1 is also known to influence gene expression in various ways. When activated, it may inhibit initiation of polymerase II-dependent transcription (42) or stimulate transcriptional elongation (30). In addition, PARP-1 has been shown to act as a coactivator for the specific transcription factors such as AP2 and B-MYB (5, 23, 31). Furthermore, Drosophila melanogaster PARP-1 has recent been shown to induce the relaxation of tight chromatin structure, which enhances the accessibility of transcription factors to the nucleosome (40). Despite these diverse activities, a common feature of PARP-1 in transcriptional control is that poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of its target proteins induces a dissociation of targets from their intact structure through the disruption of either protein-protein or DNA-protein interaction, which leads to a pleiotropic effect on gene expression.

Sterile 20 protein (Ste20p) is a putative Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase kinase kinase (MAP4K) involved in the mating pathway (15). There are over 30 different Ste20-related kinases in humans, which are further divided into the p21-activated kinase (PAK) and germinal center kinase (GCK) families, depending on their structural similarity. The PAK family is characterized by an N-terminal p21-binding domain and is regulated by the small GTP-binding proteins Rac1 and Cdc42Hs (1). The GCK family contains an N-terminal catalytic domain without the p21-binding domain and a C-terminal extension of variable length (24). These kinases are now known to have diverse functions involved in MAP kinase cascade, apoptosis, cell cycle progression, cell shape change, and cell motility. A recent study has identified three members of a novel human STE20-related serine/threonine (ST) kinase, which are homologs of kinase from chicken (KFC), thus designated human KFC A (hKFC-A), hKFC-B, and hKFC-C. hKFC-A has also been known as JNK/SAPK-inhibitory kinase (39). One hKFC member belongs to the GCK family and also shares high homology with 1,001-amino-acid protein kinases 1 and 2 (15). hKFC is able to activate the p38 MAP kinase pathway through the specific activation of the upstream MKK3 kinase (46). Furthermore, the C-terminal coiled-coil region of hKFC induces a homodimerization, which leads to autoinhibition of its kinase activity. However, the detailed function of hKFC in signal transduction remains to be studied.

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), also called human herpesvirus 8, is thought to be an etiologic agent of Kaposi's sarcoma (9). It is also associated with two diseases of B-cell origin: primary effusion lymphoma and an immunoblast variant of Castleman's disease (3, 6). The genomic sequence indicates that KSHV is a gamma-2 herpesvirus that is closely related to herpesvirus saimiri, rhesus monkey rhadinovirus, and murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (γHV68) (8, 33).

An important step in the herpesvirus life cycle is the switch from latency to lytic replication. The KSHV RTA (replication and transcription activator) has been shown to play a central role in the switch of the virus life cycle from latency to lytic replication. Ectopic expression of KSHV RTA is sufficient to disrupt viral latency and activate lytic replication to completion (18, 28, 37). As a typical transcription activator, KSHV RTA contains an amino-terminal basic DNA-binding domain and a carboxy-terminal acidic activation domain and is highly phosphorylated in vivo (27). Its amino-terminal DNA-binding domain is well conserved with other gamma-2 herpesvirus RTA homologs and shows a sequence-specific DNA-binding activity (8, 26, 35). While it is less conserved, a carboxyl acidic activation domain exhibits strong transactivation activity in the heterologous context with yeast Gal4 transcription factor (20, 27). It has been shown that RTA activates the expression of numerous viral genes in the KSHV lytic cycle, including its own promoter, polyadenylated nuclear RNA, open reading frame 57 (ORF57), vOX-2, viral G protein-coupled receptor, and vIRF1 (11, 16, 17, 22, 34, 35). While the detailed mechanism of RTA-mediated transcription activation remains unclear, several pieces of evidence suggest that RTA activates its target promoter activity through direct binding to the specific sequence and/or interaction with various cellular transcriptional factors. In fact, numerous cellular proteins, Stat3, MGC2663, RBPjκ, and CBP, interact with RTA, and these interactions synergize RTA transcriptional activity (20, 21, 34, 43). Furthermore, a recent study has demonstrated that RTA recruits cellular SWI/SNF and TRAP/Mediator complexes through its carboxy-terminal short acidic sequence and that recruitment of SWI/SNF and TRAP/Mediator complexes by RTA onto the virus lytic promoters is essential for their gene expression and thus for KSHV reactivation (19).

Since RTA is sufficient to drive the entire virus lytic cycle, the control of RTA expression and activity should play an important role in the maintenance of viral latency. A recent report has demonstrated the role of promoter methylation in controlling RTA expression (10). A methylation-free zone is required for the initiation of RTA transcription, and gene expression is often associated with demethylation in the vicinity of its promoter, suggesting that DNA methylation can repress viral reactivation by inhibiting the expression of RTA. Here, we demonstrate an additional strategy to regulate RTA-mediated lytic reactivation. Cellular PARP-1 and Ste20-like kinase hKFC interacted with the ST-rich motif of gamma-2 herpesvirus RTA. These interactions efficiently modified RTA protein and repressed its recruitment onto the virus lytic promoter regions, resulting in the inhibition of RTA-mediated viral gene expression and lytic replication. This suggests that the methylation of RTA promoter and the modification of RTA protein may synergistically function as molecular switchers to control the balance between latency and lytic reactivation of gamma-2 herpesvirus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, transient transfection, immunoprecipitation, and immunoblotting.

Detailed procedures for cell culture, transient transfection, immunoprecipitation, and immunoblotting were described in previous reports (19).

Protein purification and mass spectrometry.

To identify RTA-binding proteins, BJAB cells (107 cells) were labeled with medium containing [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine for 12 h, and the cells were collected and resuspended with lysis buffer (0.15 M NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and 50 mM HEPES buffer [pH 8.0]) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. After centrifugation, the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size syringe filter and precleared by mixing with glutathione S-transferase (GST)-bound glutathione beads twice. Precleared lysates were mixed with glutathione beads containing GST and GST-RTA fusion protein for 4 h, and the beads were extensively washed with lysis buffer. Proteins bound to glutathione beads were eluted and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Bulk protein purification was performed with 20 liters of BJAB cells as described above. Purified proteins were subjected to peptide sequencing at the Harvard Mass Spectrometry facility.

Plasmid construction.

RTA and its mutants were subcloned into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) by PCR, as previously described (19). DNA fragments containing RTA, PARP-1, or hKFC were introduced into pGEX4T-1 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden), and the GST fusion proteins were purified according to the manufacturer's instructions.

GST pull-down assays.

RTA, PARP-1, and hKFC were in vitro transcribed and translated with a T7-coupled transcription/translation system (Promega, Madison, Wis.). 35S-labeled protein was incubated with glutathione beads containing GST fusion protein in binding buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl, and 0.1% NP-40 supplemented with protease inhibitors). The reaction mixture was incubated at 4°C for 2 h. The beads were then washed four times with binding buffer, SDS-PAGE sample buffer was added, and the proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and visualized by PhosphorImager (BAS-1500; Fuji Film Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Flow cytometry.

Cells (5 × 105) were washed with complete media and stained with unconjugated K8.1 primary antibody followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody at 4°C. After the final washing, the cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, and flow cytometry was performed by fluorescence-activated cell scan/sorter (Becton Dickinson, Mountainview, Calif.). The appropriate antibodies were used for isotype controls.

ChIP.

A chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Upstate Biotech) with several modifications. Briefly, T75 culture dishes were treated with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. After a brief sonication, immunoprecipitation was performed with the appropriate antibody. After several washings, the immunocomplexes were eluted with 50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, and 1% SDS at 65°C for 10 min, adjusted to 200 mM NaCl, and incubated at 65°C for 5 h to reverse the cross-links. After successive treatments with 10 μg of RNase A/ml and 20 μg of proteinase K/ml, the samples were extracted with phenol-chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. One-tenth of the immunoprecipitated DNAs was analyzed by PCR with the primer sets for Rp (nucleotides 71221 to 71550, KSHV GenBank accession number U75698) and Mp (nucleotides 81661 to 81920). Amplifications (26 cycles) were performed in the presence of 5 μCi of [α-32P]dCTP, and the PCR products were analyzed in 5% polyacrylamide gels.

Construction of recombinant baculoviruses.

Recombinant baculoviruses expressing the PARP-1, hKFC, RTA, or green fluorescent protein (GFP) were constructed with the Bac-to-Bac expression system (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Determination of PARP-1 and hKFC activities.

Recombinant PARP-1 protein was purchased from Trevigen, and the poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation reaction was performed according to the instructions. Briefly, we incubated 1 μg of recombinant PARP-1 and substrates at room temperature for 10 min and added 2× Laemmli buffer to stop the reaction. To measure hKFC kinase activity, cellular extracts from 100-mm-diameter dishes were incubated with GST protein for 4 h. After several washings, the GST complex was subjected to an in vitro kinase reaction with 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP. Reaction products were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography.

Virus and plaque assay.

To determine the viral titer, 105 wild-type (WT) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) and PARP-1 knockout (KO) MEF were infected with γHV68 or ΔK3GFP+ γHV68 (36) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1.0 or 0.05 and were incubated for 6 h with occasional rocking. After being washed 5 times with complete media, the supernatants were harvested at each time point. The virus titer was determined by plaque assay with monolayers of NIH 3T3 cells overlaid with 1% methylcellulose for 5 days as described previously (13, 45). The GFP-positive plaques of ΔK3GFP+ γHV68 were also photographed.

RESULTS

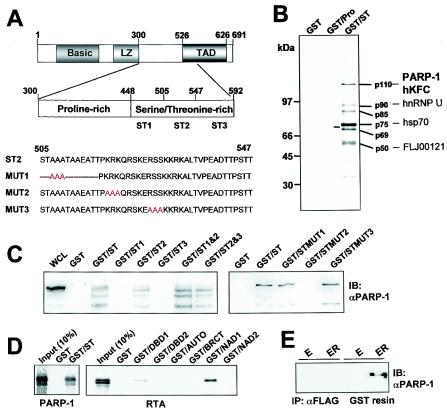

Identification of cellular proteins that interact with the ST-rich region of RTA.

To identify cellular proteins interacting with the central proline-rich and ST-rich regions of RTA, bacterially expressed GST-RTA fusion protein was used as an affinity column for 35S-labeled lysates of BJAB B cells. GST-Pro contains the proline-rich region of RTA (amino acids [aa] 300 to 447) and GST-ST contains the ST-rich region of RTA (aa 448 to 592) (Fig. 1A). Approximately six polypeptides with molecular masses ranging from 50 to 110 kDa were found to specifically interact with the GST-ST fusion protein (Fig. 1B). None of these cellular proteins interacted with GST and GST-Pro proteins under the same conditions (Fig. 1B). To further characterize these cellular proteins, they were purified from 20 liters of BJAB cells and analyzed by mass spectrometry. The resulting proteins were subjected to microsequencing and then matched to known sequences (Fig. 1B). The 110-kDa band was identified as two polypeptides, PARP-1 and hKFC. Each of 90-, 75-, and 50-kDa bands was identified as heterogeneous nuclear riboprotein U, heat shock protein 70 (hsp70), and an uncharacterized FLJ00121 protein. These proteins were often detected in other GST pull-down assays (unpublished data), indicating that they are the potential contaminants. Because of relatively low concentrations, the cellular polypeptides with molecular masses of 69 and 85 kDa could not be further analyzed by mass spectrometry (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Purification and identification of KSHV RTA binding proteins. (A) Schematic diagram of the proline-rich and ST-rich regions of RTA and its mutants. Amino acid numbers indicate the proline-rich and ST-rich regions of RTA. LZ, leucine zipper region; TAD, transcriptional activation domain. Red letters indicate the mutations described in the text. (B) Identification of RTA binding proteins. Glutathione-Sepharose beads containing 5 μg of GST, GST-Pro, or GST-ST fusion protein were mixed with lysates of 35S-labeled BJAB-B cells. RTA binding proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and autoradiographed with a PhosphorImager. Lines indicate the proteins that specifically interacted with GST-ST. The proteins identified by mass spectrometry are indicated at the right side of the figure. (C) Specific interaction of the RTA ST-rich region with PARP-1. BJAB cell lysates were used for pull-down assay with GST, GST-ST, or GST-ST mutant fusion proteins followed by immunoblotting (IB) with an anti-PARP-1 (αPARP-1) antibody. Whole-cell lysates (WCL) were included as a control. (D) Direct interaction between PARP-1 and RTA. [35S]methionine-labeled PARP-1 and RTA proteins from in vitro translation were mixed with GST or GST-ST protein and GST orGST-PARP-1 subdomain fusion protein, respectively. After extensive washing, 35S-labeled polypeptides associated with GST fusion proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. The first lane indicates the 10% input amount of PARP-1 and RTA proteins used for the binding assay. (E) Interaction of PARP-1 and RTA in 293T cells. At 48 h posttransfection, with either EB-GST (E) or EB-GST-RTA vector (ER), 293T cell lysates were used for precipitation (IP) with an anti-FLAG (αFLAG) antibody or glutathione-Sepharose affinity column (GST resin). The polypeptides associated with anti-Flag and GST complex were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with an anti-PARP-1 antibody. (F) Poly(ADP-ribosy)lation of RTA by PARP-1. GST, GST-ST, or GST-ST mutant fusion protein was incubated with 1 μg of recombinant PARP-1 and [32P]NAD+. 32P-labeled GST, GST-ST, or GST-ST mutant fusion protein was separated by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. (G and H) After mixing with recombinant PARP-1, the glutathione beads containing GST, GST-ST, or GST-ST mutant fusion protein were extensively washed, subjected to a ribosylation reaction with NAD+, separated by SDS-PAGE, and reacted with an anti-PAR (αPAR) antibody (G) or an anti-PARP-1 antibody (H). A similar amount of each GST fusion protein was used in this assay (right bottom panel). αGST, anti-GST.

PARP-1 interacts with and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ates RTA.

To confirm the interaction of RTA with PARP-1, we repeated the GST pull-down assay with lysates of BJAB cells and performed immunoblot analysis with an anti-PARP-1 antibody. This showed that PARP-1 was detected in the GST-ST complex but not in the GST complex (Fig. 1C). Additionally, 35S-labeled PARP-1 derived from in vitro translation was found to directly interact with GST-ST protein but not with GST protein (Fig. 1D). To further delineate this interaction, the ST region was subdivided into three smaller fragments, ST1, ST2, and ST3. A pull-down assay with GST fusion proteins containing each subregion of the ST-rich region showed that the ST subregion 2 bound to PARP-1 as efficiently as the ST region, whereas other ST subregions did not (Fig. 1C). In addition, mutations were introduced into the ST subregion 2 to identify the specific motifs required for this interaction. Mutation 1 of ST2 subregion (STMUT1) contains the deletion of all serine and threonine residues, leaving three alanines (507AAA509); mutation 2 (STMUT2) contains the replacement of the basic amino acid sequence 518KRK520 with alanines; mutation 3 (STMUT3) contains the replacement of the amino acid sequence 526RSS528 with alanines. GST-STMUT1, GST-STMUT2, and GST-STMUT3 fusion proteins were used for a pull-down assay with lysates from BJAB cells. It showed that the mutation introduced into the basic amino acids (MUT2) crippled the interaction with PARP-1, whereas the other mutations did not affect this interaction, suggesting the important role of 518KRK520 amino acids within the RTA ST region for PARP-1 interaction (Fig. 1C).

PARP-1 contains multiple domains, each of which contains a specific function (4, 29). These domains are DNA binding domain 1 (DBD1; aa 1 to 213), DNA binding domain 2 (DBD2; aa 214 to 337), automodification domain (AUTO; aa 338 to 523), BRCA1 C-terminal domain (BRCT; aa 384 to 460), NAD binding domain 1 (NAD1; aa 524 to 780), and NAD binding domain 2 (NAD2; aa 764 to 1014). To map the RTA binding region of PARP-1, GST fusion proteins containing each domain of PARP-1 were used for a binding assay with the 35S-labeled RTA derived from in vitro translation. It showed that NAD1, the amino terminal half of the catalytic domain of PARP-1, strongly interacted with RTA, whereas a low level of interaction of RTA was also detected with DBD1 of PARP-1 (Fig. 1D). Finally, the in vivo interaction between PARP-1 and RTA was examined in 293T cells transfected with GST or GST-RTA expression vector. At 48 h posttransfection, cell lysates were used for a GST pull-down assay. An anti-Flag antibody was included as a negative control. It showed that endogenous PARP-1 was detected in the GST-RTA complex but not in the GST complex (Fig. 1E). An anti-Flag antibody did not precipitate PARP-1 under the same conditions (Fig. 1E). These results indicate the specific interaction between RTA and PARP-1.

To test whether RTA was a substrate for PARP-1-mediated poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation, a GST fusion protein containing the RTA ST region and its mutant forms was incubated with [32P]NAD+ and recombinant PARP-1 protein. As shown in Fig. 1F, GST fusion proteins containing the ST, ST2, ST1&2, ST2&3, or STMUT1 subregion were efficiently and equivalently poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated by PARP-1, whereas GST and GST fusion proteins containing the STMUT2, ST1, or ST3 region were not, indicating that PARP-1 efficiently poly(ADP-ribosy)lates the ST region of RTA and that an interaction with PARP-1 is necessary for the poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of RTA (Fig. 1F). To further test this, bacterially purified PARP-1 was mixed with each GST-ST fusion protein. GST complex was precipitated by pull-down assay and incubated with NAD+ in the ADP-ribosylation buffer, and this was followed by immunoblotting with a monoclonal antibody that reacted only with the ADP-ribosylated protein. It showed that a GST fusion protein containing the ST, ST2, ST1&2, ST2&3, or STMUT1 subregion was interacted with and ADP-ribosylated by PARP-1, whereas GST and GST fusion proteins containing the STMUT2, ST1, or ST3 region were not (Fig. 1G). A 110-kDa ADP-ribosylated protein that was detected in the complexes of GST-ST fusion proteins (Fig. 1G) was found to be the auto-ADP-ribosylated PARP-1 (Fig. 1H). In summary, the serine-rich region of RTA specifically interacts with PARP-1 and this interaction mediates an efficient ADP-ribosylation of RTA by PARP-1.

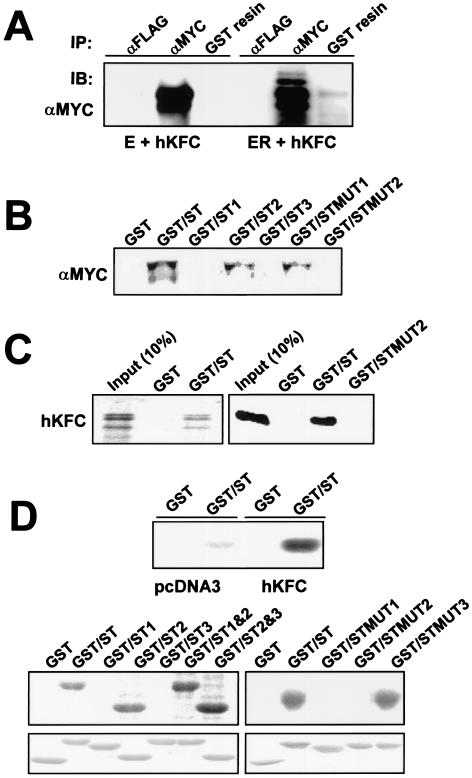

A human Ste20-like kinase, hKFC, interacts with RTA and phosphorylates the ST-rich domain of RTA.

To test the interaction between RTA and hKFC in vivo, lysates of 293T cells transfected with the myc-tagged hKFC expression vector and/or GST-RTA expression vector were used for precipitation with glutathione beads or an anti-myc antibody. It showed that hKFC protein was readily detected in the GST-RTA fusion complex but not in the GST complex (Fig. 2A). To determine the hKFC-interacting domain within RTA, lysates of 293T cells transfected with the myc-tagged hKFC expression vector were incubated with GST or GST-RTA fusion proteins containing the ST-rich region or mutant forms of this region as shown in Fig. 1A. It showed that GST-ST, GST-ST2, and GST-STMUT1 fusion proteins were capable of interacting with hKFC while GST, GST-ST1, GST-ST3, and GST-STMUT2 were not (Fig. 2B). When [35S]methionine-labeled hKFC derived from in vitro translation or bacterially purified hKFC protein was used for a pull-down assay with the GST-ST fusion protein, a direct interaction between GST-RTA and hKFC was readily detected (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

hKFC interacts with and phosphorylates RTA. (A) Interaction of RTA with hKFC in 293T cells. At 48 h posttransfection, with either EB-GST (E) and the myc-tagged hKFC expression vector or EB-GST-RTA vector (ER) with the myc-tagged hKFC expression vector, 293T cell lysates were used for precipitation (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody (αFLAG), anti-myc antibody (αMYC), or glutathione-Sepharose affinity column (GST resin). The polypeptides associated with anti-Flag, anti-myc, or GST complex were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting (IB) with an anti-myc antibody. By comparison with hKFC in the anti-myc complex, approximately 5% of hKFC was detected in the GST-RTA complex. (B) Mutation at the basic amino acids of the RTA ST-rich region abolishes the interaction with hKFC. Lysates of 293T cells transfected with the myc-tagged hKFC expression vector were mixed with GST, GST-ST, and GST-ST mutant proteins. Polypeptides associated with GST complex were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by an anti-myc antibody. (C) Direct interaction between RTA and hKFC. (Left panel) [35S]methionine-labeled hKFC protein from in vitro translation was mixed with GST or GST-ST fusion protein. After extensive washing, 35S-labeled hKFC associated with GST or GST-ST fusion protein was separated by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. (Right panel) Purified hKFC protein was mixed with GST, GST-ST, or GST-STMUT2 fusion protein. After extensive washings, hKFC associated with GST fusion protein was separated by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with an anti-hKFC antibody. The first lane indicates the 10% input amount of hKFC protein used for both binding assays. (D) Phosphorylation of the RTA ST-rich region by hKFC. Lysates of 293T cells transfected with pcDNA3 vector and the myc-tagged hKFC expression vector were mixed with GST or GST-ST fusion protein (top). Lysates of 293T cells transfected with the myc-tagged hKFC expression vector were mixed with GST, GST-ST, or GST-ST mutantfusion protein as indicated above the gels (bottom). After several washings, GST complex was subjected to an in vitro kinase reaction with [γ-32P]ATP. Reaction products were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. A similar amount of each GST fusion protein was used in this assay (lower panel).

Furthermore, the lysates of 293T cells transfected with pcDNA3 vector or pcDNA3-hKFC vector were used for pull-down assays with GST and GST-ST protein, and these GST complexes were then subjected to in vitro kinase assay with [γ-32P]ATP. It showed that GST-ST protein was weakly phosphorylated by an endogenous hKFC in 293T cells transfected with vector alone, whereas its level of phosphorylation was dramatically increased with 293T cells transfected with hKFC expression vector (Fig. 2D). To identify the potential phosphorylation sites of RTA by hKFC, 293T cells transfected with the hKFC expression vector were used for pull-down assays with GST-ST fusion proteins followed by an in vitro kinase assay with [γ-32P]ATP. It showed that GST-ST, GST-ST2, GST-ST1&2, GST-ST2&3, and GST-STMUT3 were efficiently phosphorylated by the associated hKFC while GST, GST-ST1, GST-ST3, GST-STMUT1, and GST-STMUT2 were not (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, GST-STMUT1, which was capable of interacting with hKFC, was not phosphorylated by the associated hKFC (Fig. 2B and D), indicating that the serine (S505) and threonine residues (T506, T510, T515, and T516) of RTA are the potential sites for hKFC-mediated phosphorylation. Thus, the basic amino acids within the ST-rich region of RTA are required for the interaction with hKFC, and the serine and threonine residues upstream of these basic amino acids are the potential sites for hKFC-mediated phosphorylation.

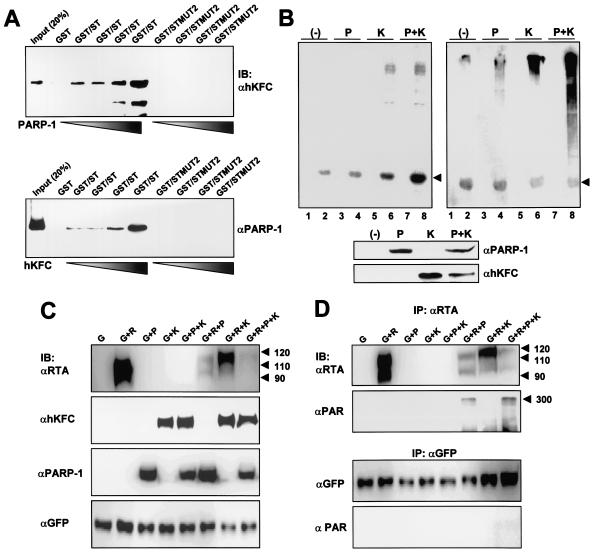

Synergistic effect of PARP-1 and hKFC on RTA binding and its modification.

The fact that the same region of RTA was required for the interaction with PARP-1 and hKFC suggested the potential competition or synergic effect of PARP-1 and hKFC on their RTA binding. To investigate this effect, we incubated the same amounts of GST-ST and hKFC proteins with increasing amounts of PARP-1 or the same amounts of GST-ST and PARP-1 proteins with increasing amounts of hKFC. GST-STMUT2, which did not interact with PARP-1 and hKFC, was included as a negative control. The interaction between GST-ST and hKFC was gradually increased by the addition of PARP-1 (Fig. 3A). In parallel, the interaction between GST-ST and PARP-1 was also gradually increased by the addition of hKFC (Fig. 3A). These results indicate that PARP-1 and hKFC synergistically enhance RTA interaction. Consequently, this additive effect of PARP-1 and hKFC on RTA binding led to the increases in phosphorylation and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of RTA by hKFC and PARP-1, respectively (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Synergistic effect of PARP-1 and hKFC on RTA binding and modification. (A) Synergistic effect of PARP-1 and hKFC on RTA binding. One microgram of hKFC protein and 1 μg of GST-ST or GST-STMUT2 protein were incubated with increasing amounts of PARP-1 (0, 0.1, 0.5, and 1 μg) or 1 μg of PARP-1 and 1 μg of GST-ST or GST-STMUT2 protein were incubated with increasing amounts of hKFC (0, 0.1, 0.5, and 1 μg), and incubation was followed by precipitation with glutathione beads. After several washings, GST complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-PARP-1 (αPARP-1) or anti-hKFC (αhKFC) antibody. (B) Synergistic effect of PARP-1 and hKFC on RTA modification. Lysates of 293T cells transfected with PARP-1 expression and/or hKFC expression were incubated with GST or GST-ST fusion protein. After several washings, the GST complex was subjected to an in vitro kinase reaction with [γ-32P]ATP (left) or a ribosylation reaction with NAD (right). The in vitro kinase reaction was analyzed by autoradiography, and the in vitro ribosylation reaction was analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-PAR antibody. Arrow indicates the GST-ST protein. Lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7, GST; lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8, GST-ST. Expression levels for PARP-1 and hKFC were detected by immunoblotting with anti-PARP-1 and anti-hKFC antibody (lower panel). P, PARP-1; K, hKFC; −, vector alone. (C) Modification of RTA by PARP-1 and hKFC. Sf9 insect cells were coinfected with recombinant baculoviruses as indicated at the top of the figure. Whole-cell extracts were for immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Arrows indicate the RTA protein. G, GFP; R, RTA; αRTA, anti-RTA; αGFP, anti-GFP. (D) In vivo poly(ADP-ribosy)lation of RTA by PARP-1. Extracts of Sf9 insect cells were precipitated with anti-RTA or anti-GFP antibody in 0.1% SDS-containing lysis buffer, and immunoprecipitates (IP) were further used for immunoblotting with anti-RTA, anti-GFP, or anti-PAR (αPAR) antibody. Arrows indicate the poly(ADP ribosy)lated RTA.

To further investigate the effect of PARP-1 and hKFC on RTA modification, recombinant baculoviruses expressing PARP-1, hKFC, RTA, or GFP were constructed. 48 h postinfection, lysates of Sf9 insect cells infected with recombinant baculoviruses in various combinations were used for an immunoblot assay. It showed that full-length RTA migrated as a 90- to 110-kDa protein in SDS-PAGE as shown previously (Fig. 3C) (27). Interestingly, PARP-1 coexpression dramatically reduced the amount of 90- to 110-kDa RTA, and hKFC coexpression induced the migration retardation of RTA, where most RTA was present at a molecular weight of approximately 120 kDa (Fig. 3C). The effect of PARP-1 and hKFC on RTA was specific because it was not detected with GFP and p53 proteins (Fig. 3C and unpublished data). To determine whether the reduction of 90- to 110-kDa RTA was caused by poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by PARP-1, RTA from Sf9 insect cells coinfected with recombinant PARP-1 and RTA baculoviruses was immunoprecipitated with an anti-RTA antibody in SDS-containing lysis buffer and immunoblotted with a monoclonal antibody specific for poly(ADP-ribose) or an anti-RTA antibody. It showed that a large portion of RTA protein was poly(ADP-ribosy)lated by PARP-1 and migrated at a high molecular mass (approximately 300 kDa) (Fig. 3D). In contrast, GFP was not poly(ADP-ribosy)lated by PARP-1 and its migration was not altered under the same conditions (Fig. 3D). These results demonstrate that PARP-1 and hKFC strongly induce the poly(ADP-ribosy)lation and phosphorylation of RTA, which both strongly affect RTA migration in SDS-PAGE.

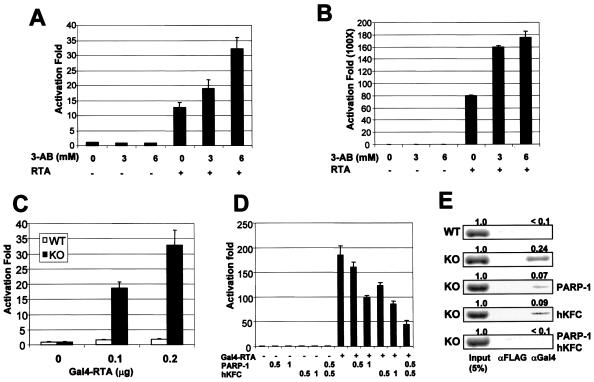

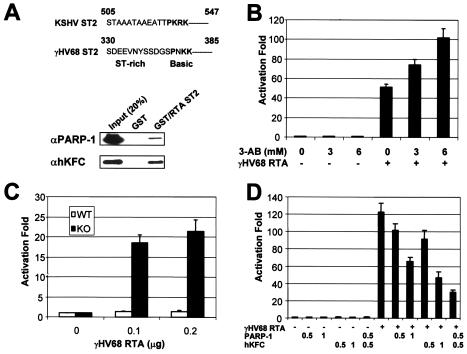

PARP-1 and hKFC act as repressors of RTA activity.

To determine the effect of PARP-1 on RTA activity, 293T cells transfected with RTA expression vector and an Rp-luciferase reporter containing its own promoter (Rp) were treated with increasing amounts of 3-aminobenzamide (3-AB), a specific inhibitor of PARP-1. RTA-mediated activation of Rp promoter activity was significantly enhanced by 3-AB treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). A more dramatic effect of 3-AB treatment on RTA-mediated transcriptional activation was observed with a GAL4-RTA construct, where the Gal4 DNA-binding domain (DBD) was fused in frame to full-length RTA (Fig. 4B). In addition, this effect was specific because the transcriptional activity of Gal4-VP16 was not affected by 3-AB treatment under the same conditions (data not shown). To further demonstrate the effect of PARP-1 on the RTA transcriptional activity, MEFs derived from PARP-1 gene KO and WT mice were transfected with Gal4-RTA and a Gal4-luciferase reporter construct. It showed that the transcriptional activity of Gal4-RTA was approximately 20-fold higher in PARP KO MEFs than in WT MEFs (Fig. 4C). In contrast, GAL4 showed a similar level of transcription activity in both WT and PARP-1 KO MEFs (data not shown). To further investigate the effect of PARP-1 deficiency on RTA activity, Gal4-RTA activity was measured in PARP-1 KO MEFs transfected with the PARP-1 expression vector. The hKFC expression vector was also included to test its effect on RTA activity. Increasing amounts of PARP-1 or hKFC expression vector decreased Gal4-RTA activity (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, coexpression of PARP-1 and hKFC synergistically repressed Gal4-RTA activity (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 4.

Repression of RTA transcription activity by PARP-1 and hKFC. (A) Increase of RTA-mediated R promoter activation by 3-AB treatment. 293T cells were transfected with Rp-luciferase reporter and β-galactosidase control reporter together with (+) or without (−) RTA expression vector. The next day, cells were treated with increasing amounts of 3-AB (0, 3, and 6 mM) for 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured with cell extracts and normalized by β-galactosidase activity. Bars indicate the standard errors. (B) Increase of Gal4-RTA transcription activity by 3-AB treatment. 293T cells were transfected with Gal4-luciferase reporter and β-galactosidase control reporter together with or without Gal4-RTA expression vector. The same procedure as described above was used. (C) Enhanced transcription activity of RTA in PARP-1 KO MEFs. WT MEFs and PARP-1 KO MEFs were transfected with Gal4-luciferase reporter together with increasing amounts of Gal4-RTA expression vector. At 48 h, luciferase activity was measured and normalized by β-galactosidase activity. (D) Repression of RTA transcription activity by expression of PARP-1 and/or hKFC. PARP-1 KO MEFs were transfected with expression and reporter vectors as indicated at the bottom (amounts are in micrograms). At 48 h posttransfection, luciferase activity was measured. Luciferase activity is represented as the average of the results from three independent experiments. (E) Reduction of RTA recruitment onto the Gal4 promoter by PARP-1 and hKFC expression. A ChIP assay was performed with extracts of WT MEFs or PARP-1 KO MEFs transfected with Gal4-RTA and Gal4-luciferase together with or without PARP-1 and/or hKFC expression vectors as indicated at the right side of figure. Anti-Flag (αFLAG) and anti-Gal4 (αGal4) antibodies were used for the ChIP assay. The first lane indicates the 5% input amount of genomic DNA used for the ChIP assay.

To define the detailed mechanism of the inhibitory effect of PARP-1 and hKFC on Gal4-RTA transcription activation activity, we performed a ChIP assay to measure the level of Gal4-RTA recruitment onto the Gal4 promoter in WT MEFs and PARP-1 KO MEFs. It showed that a significantly higher amount of Gal4-RTA was detected on the Gal4 promoter in KO MEFs than in WT MEFs (Fig. 4E). Consistent with the results of RTA transcription activity (Fig. 4D), expression of PARP-1 and/or hKFC in KO MEFs considerably reduced the recruitment of Gal4-RTA onto the Gal4 promoter (Fig. 4E). These results suggest that PARP-1 and hKFC expressions modify Gal4-RTA, which decreases its recruitment onto the promoter region, thereby suppressing Gal4-RTA transcriptional activity. It is also possible that hKFC and/or PARP-1 modified the Gal4 DBD. However, since the transcription activities of Gal4-VP16 and Gal4 were not affected by the PARP-1 inhibitor 3-AB and the PARP-1 KO, respectively, if present, the modification of Gal4 DBD by PARP-1 and/or hKFC minimally affected the recruitment of Gal4-RTA onto the promoter region.

Interaction of RTA with PARP-1 and hKFC suppresses RTA-mediated KSHV lytic reactivation.

RTA has been shown to be sufficient to induce a complete cycle of KSHV lytic reactivation. To examine the role of PARP-1 and hKFC interaction in KSHV lytic replication, the RTA MUT2 mutant that was not able to interact with PARP-1 and hKFC was compared to WT RTA for its activity to induce virus lytic replication. For this assay, we used KSHV-infected BCBL1 cell lines (TRExBCBL1) in which the Myc epitope-tagged WT RTA or RTA MUT2 mutant gene was integrated into the chromosomal DNA under the control of a tetracycline-inducible promoter. The treatment of these cells with doxycycline induced RTA and RTA MUT2 expression at equivalent levels (Fig. 5B). To assay KSHV lytic reactivation induced by WT RTA and RTA MUT2, we treated TRExBCBL1-pcDNA5, TRExBCBL1-RTA, and TRExBCBL1-RTA MUT2 cells with 0.1 μg of doxycycline/ml. The viral reactivation assay used a polyclonal antibody that recognizes the K8.1 envelope glycoprotein expressed with late kinetics as described previously (25). This protein is specific to lytically infected cells since it is expressed only on cells that are committed to viral reactivation. Approximately 3% of TRExBCBL1-pcDNA5 cells showed spontaneous surface expression of K8.1 before doxycycline stimulation and did not increase K8.1 surface expression after 3 days of doxycycline stimulation (Fig. 5). In contrast, TRExBCBL1-RTA cells showed an increase in K8.1 surface expression in response to doxycycline stimulation: approximately 35% of these cells underwent lytic reactivation after 3 days of stimulation (Fig. 5A). TRExBCBCL1-RTA MUT2 cells showed a significantly enhanced increase in K8.1 surface expression: over 90% of cells showed the reactivation after 3 days of doxycycline stimulation (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, more than 45% of TRExBCBL1-RTA MUT2 cells underwent lytic replication after 1 day of doxycycline induction, whereas less than 20% of TRExBCBL1-RTA cells underwent lytic replication under the same conditions (Fig. 5A). In addition, viral interleukin 6 (vIL-6) and K8 proteins, which have been shown to be expressed during lytic replication (38), were expressed with much faster kinetics and at significantly higher extents in TRExBCBL1-RTA MUT2 cells than in TRExBCBL1-RTA cells upon doxycycline induction (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Enhanced KSHV lytic replication by RTA MUT2 mutant. (A) Level of KSHV lytic reactivation. After the stimulation with doxycycline (0.1 μg/ml), TRExBCBL1-pcDNA5, TRExBCBL1-RTA, and TRExBCBL1-MUT2 cells were fixed by paraformaldehyde and reacted with K8.1 rabbit sera followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody. The data were reproduced in three independent experiments. (B) Expression of KSHV vIL-6 and K8 protein induced by RTA and the RTA MUT2 mutant. After doxycycline treatment for 0, 1, 2, and 3 days, KSHV-infected TRExBCBL1-RTA (WT) and TRExBCBL1-RTA MUT2 (MUT2) cells were lysed, and 10 μg of total proteins was subjected to immunoblotting with anti-RTA, anti-vIL-6, and anti-K8 antibodies. (C) ChIP assay of RTA-dependent promoters. KSHV-infected TRExBCBL1-pcDNA5, TRExBCBL1-RTA, and TRExBCBL1-TRA MUT2 cells were collected after 24 h of 0.1-μg/ml doxycycline treatment. ChIP assays were performed with an anti-His (αHis) antibody (Ab). PCR products corresponding to each viral promoter were generated from an aliquot (2%) of total immunoprecipitated material (Input).

Finally, ChIP assays were used to examine the amount of RTA and RTA MUT2 proteins recruited onto the RTA (Rp) and ORF57 (Mp) promoters, which both are dependent on RTA for their activation (16, 26). It showed that a significantly higher level of RTA MUT2 than WT RTA was recruited onto both the Rp and Mp promoter regions, indicating that the faster kinetics and stronger level of lytic replication induced by the RTA MUT2 protein is most likely mediated by its efficient recruitment onto the virus lytic promoters (Fig. 5C). These results indicate a strong reverse correlation between the ability of RTA to activate virus lytic reactivation and the ability of RTA to interact with cellular PARP-1 and hKFC proteins.

PARP-1 and hKFC interact with γHV68 RTA and inhibit virus lytic replication.

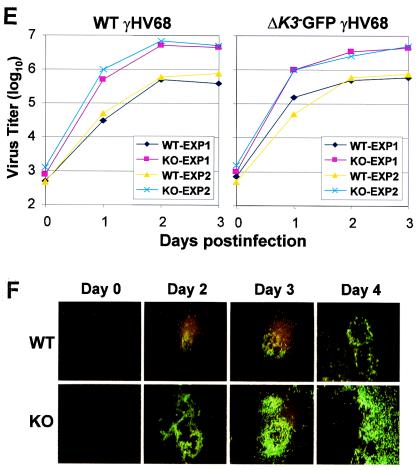

RTA proteins of gamma-2 herpesviruses have been shown to share their sequence, structure, and function (41, 45). To investigate whether PARP-1 and hKFC function as repressors of other gamma-2 herpesvirus RTA, we tested the potential interaction of γHV68 RTA with PARP-1 and hKFC. The computer analysis indicates that the sequences of aa 330 to 385 of the γHV68 RTA protein show a significant homology with the ST2 region of the KSHV RTA (Fig. 6A). In fact, as seen with the KSHV RTA ST2 region (Fig. 1A), this short region of γHV68 RTA contains the ST-rich sequences followed by proline and three basic amino acids; thus, this region was designated γHV68 RTA ST2 (Fig. 6A). GST pull-down and immunoblot assays showed that GST-γHV68 RTA ST2 efficiently interacted with PARP-1 and hKFC in vitro while GST did not (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Interaction of γHV68 RTA with PARP-1 and hKFC. (A) Alignment between KSHV RTA and γHV68 RTA and interaction of the γHV68 RTA ST region with PARP-1 and hKFC. The ST2 regions of KSHV RTA and γHV68 RTA are aligned. GST or GST-RTA ST2 (γHV68RTA amino acids 330 to 385) was incubated with recombinant PARP-1 and hKFC proteins, and GST complexes were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-PARP-1 (αPARP-1) and anti-hKFC (αhKFC) antibodies. (B) Activation of γHV68 RTA-induced ORF57 promoter activity by 3-AB treatment. 293T cells were transfected with ORF57-luciferase and β-galactosidase reporters together with (+) or without (−) γHV68 RTA. The next day, cells were treated with increasing amounts of 3-AB (0, 3, and 6 mM) for 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured with cell extracts and normalized by β-galactosidase activity. Bars indicate the standard errors. (C) Enhanced transcription activity of γHV68 RTA in PARP-1 KO MEFs. WT MEFs and PARP-1 KO MEFs were transfected with ORF57-luciferase reporter together with increasing amounts of γHV68 RTA expression vector. Luciferase activity is represented as the average of the results from three independent experiments. (D) Repression of γHV68 RTA transcription activity by expression of PARP-1 and/or hKFC. PARP-1 KO MEFs were transfected with expression and reporter vectors as indicated at the bottom of figure (amounts are in micrograms). At 48 h posttransfection, luciferase activity was measured. Luciferase activity is represented as the average of the results from three independent experiments. (E) Enhanced level of γHV68 lytic replication in PARP-1 KO MEFs. WT and PARP-1 KO MEFs were infected with WT γHV68 or ΔK3-GFP γHV68 at an MOI of 1. The virus titers were determined by plaque assay. The results from two independent experiments are presented. (F) Size increase of ΔK3-GFP γHV68 plaques in PARP-1 KO MEFs. WT and PARP-1 KO MEFs were infected with ΔK3-GFP γHV68 at an MOI of 0.1. The GFP-positive plaques of ΔK3-GFP γHV68 were photographed.

To examine the effect of PARP-1 on γHV68 RTA activity, 293T cells were transfected with γHV68 RTA and the luciferase reporter construct of the ORF57 promoter that has been shown to be regulated by γHV68 RTA (44). The next day, these cells were treated with increasing amounts of 3-AB. As seen with KSHV RTA (Fig. 4A), γHV68 RTA-mediated activation of ORF57 promoter activity was significantly increased by 3-AB treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6B). To further demonstrate the effect of PARP-1 on γHV68 RTA transcriptional activity, WT MEFs and PARP-1 KO MEFs were transfected with γHV68 RTA and the ORF57-luciferase reporter construct. The transcriptional activity of γHV68 RTA was approximately 20-fold higher in PARP KO MEFs than in WT MEFs (Fig. 4C). Additionally, the expression of PARP-1 and/or hKFC in PARP-1 KO MEFs suppressed the γHV68 RTA activity (Fig. 6D). Thus, these results demonstrate that PARP-1 and hKFC function as repressors of the KSHV RTA and γHV68 RTA.

γHV68 RTA has also been shown to play a critical role in virus lytic replication (45). To test whether the deficiency of the PARP-1 gene affected γHV68 replication, WT MEFs and PARP-1 KO MEFs were infected with WT γHV68 or the ΔK3-GFP γHV68 mutant at a MOI of 1.0. The ΔK3-GFP γHV68 mutant virus has been shown to replicate as WT virus in culture (36). Virus titers were determined by plaque assay. The production of both γHV68 and ΔK3-GFP γHV68 particles was more than 20- to 50-fold higher during the course of lytic replication in PARP-1 KO MEFs than that in WT MEFs (Fig. 6E). In addition, the plaque sizes of ΔK3-GFP γHV68 virus were visually much larger in PARP-1 KO MEFs than in WT cells (Fig. 6F). These results strongly demonstrate that cellular PARP-1 acts as a repressor for de novo replication of γHV68 by inhibiting RTA activity.

DISCUSSION

The previous works have focused on the identification of cellular coactivators that induce RTA transcription activity (19). Here, we report that PARP-1 and hKFC interact with the ST-rich region of gamma-2 herpesvirus RTA and that poly(ADP-ribosy)lation and phosphorylation of RTA by PARP-1 and hKFC, respectively, result in the suppression of its recruitment onto the virus lytic promoters that are regulated by RTA. This suggests that the modification of RTA by PARP-1 and hKFC interferes directly or indirectly with the recruitment of RTA onto the promoter region, which results in the inhibition of RTA-mediated transcriptional activation and thereby, the suppression of virus lytic replication. This is the first demonstration that PARP-1 and hKFC function as cellular sensors to control herpesvirus lytic replication, which should play an important role in the establishment and/or maintenance of herpesvirus latency.

PARP-1 acts as an inhibitor of viral transcription activity.

PARP-1 has been shown to act as an activator or a repressor in transcriptional regulation, depending on target genes and specific cellular environments. Several studies have reported an interesting model of PARP-1 function on transcriptional regulation. In this model, the nucleosomes are remained as a condensed form without PARP-1 activity, which makes it difficult for transcriptional activators to access them (12, 40). The basal activity of PARP-1 is necessary for the initiation of transcription through the addition of ADP-ribose tails to histones, resulting in the decondensation of chromatin. Upon activation, however, PARP-1 adds a long ADP-ribose tail to transcription factors, which leads to the dissociation of these factors from DNA through electrostatic repulsion. We demonstrated that RTA was extensively poly(ADP-ribosy)lated by PARP-1 in in vitro reactions and in cells. In addition, our ChIP assays showed a significant increase of Gal4-RTA recruited on the Gal4 promoter in PARP-1 KO cells compared to that in WT cells and an enhanced recruitment of RTA MUT2 onto the Rp and Mp promoters compared to WT RTA. These results were further supported by the enhanced replication of γHV68 in PARP-1 KO cells compared to WT cells. Finally, our ChIP assay showed that neither cellular PARP-1 nor poly(ADP-ribosy)lated RTA was recruited onto the Rp and Mp promoters (data not shown). Thus, the poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of RTA by PARP-1 likely induces a dissociation of RTA from its intact complex structure through the disruption of either protein-protein or DNA-protein interaction, which leads to the negative effect on RTA-mediated transcription activation. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that, as seen with cellular transcription (40), the basal activity of PARP-1 may give benefits to RTA activity by being recruited to viral promoters independent of the interaction with RTA.

Novel function of hKFC as transcriptional repressor.

According to their structural and functional similarities, mammalian Ste20 family kinases are divided into two groups, the PAK and GCK subfamilies. Both the PAK subfamily and the GCK subfamily function as a MAP4K to induce the activation of p38/SAPK pathways. For example, GCK is recruited into theTRAF2 molecule upon tumor necrosis factor stimulation and then activates the downstream kinases, MAP3Ks (7). hKFC-A, hKFC-B, and hKFC-C, whose kinase domains share a high similarity with the GCK subfamily, have recently been identified. All three forms of hKFC are able to activate the p38 MAP kinase pathways through the specific activation of the upstream MAP3K. Here, we demonstrate that hKFC interacts with and phosphorylates RTA in vitro and in cells and that this phosphorylation inhibits the RTA-mediated transcriptional activation. While the important role of phosphorylation in regulating transcription factor activity is now well established, it is unusual that hKFC, which functions at the upstream signaling pathway, is directly involved in the regulation of transcriptional factor activity. Specifically, hKFC extensively phosphorylated RTA protein, which led to the migration retardation of RTA protein in vivo. The previous report has also shown that RTA is highly phosphorylated in cells and that this phosphorylation contributed to the abnormal migration (27). While the sequence analysis suggests that casein kinase II and protein kinase C (PKC) are potentially enzymes that phosphorylate RTA, we demonstrate that hKFC is likely the major cellular enzyme that phosphorylates RTA. Since stimulation with tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate, a potent activator of PKC kinase activity, has been shown to efficiently induce KSHV lytic replication (32), PKC and hKFC may have the opposite effect on gamma-2 herpesvirus lytic replication: PKC is involved in the induction of virus lytic replication, whereas hKFC is involved in the suppression of virus lytic replication. In addition, hKFC has been shown to locate in the cytoplasm, whereas RTA is present primarily in the nucleus (20, 46). This suggests that the interaction with hKFC and/or the phosphorylation by hKFC potentially affects RTA localization and, thereby, its transcriptional activity. Thus, a detailed study of hKFC signal transduction will provide an important clue for understanding the natural balance between latency and lytic reactivation of gamma-2 herpesvirus.

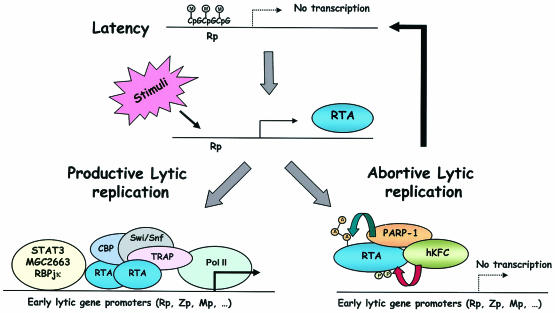

Hypothetical model for gamma-2 herpesvirus lytic replication.

An important step in the gamma-2 herpesvirus life cycle is the switch from latency to lytic replication. Since RTA is sufficient for the completion of the entire virus lytic cycle, the control of RTA expression and activity should play an important role in the maintenance of viral latency. The CpG methylation of the RTA promoter (Rp) sequence during latency is associated with the assembly of repressed chromatin and the decrease in its transcription (10). Upon external stimuli, CpG methylation of the RTA promoter is progressively reversed, resulting in RTA expression. Subsequently, RTA activates its target promoter activity through direct binding to the specific sequence and/or interaction with various cellular transcriptional cofactors, including Stat3, MGC2663, CBP, RBPjκ, SWI/SNF, and TRAP/Mediator, which lead to the productive lytic replication. On the other hand, cellular PARP-1 and hKFC induce the poly(ADP-ribosy)lation and phosphorylation of RTA, respectively, and these modifications synergistically inactivate RTA transcription activity, which ultimately leads to the abortive lytic replication. Thus, this model (Fig. 7) suggests that the methylation of the RTA promoter and the posttranslational modification of RTA protein may provide a comprehensive inhibition for blocking gamma-2 herpesvirus lytic reactivation and to maintain herpesvirus latency. Further study will be directed toward providing evidence for or against this hypothesis.

FIG. 7.

Hypothetical model for gamma-2 herpesvirus lytic replication. M, methylation; P, phosphorylation; A, ADP-ribosylation.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank J. Choe, C. H. Kim, S. Gutkind, V. L. Dawson, K. Yamanish, S. Speck, P. Stevenson, and R. Sun for providing reagents and viruses.

This work was partly supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants CA82057, CA91819, AI38131, and RR00168. J. Jung is a Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Scholar.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bagrodia, S., and R. A. Cerione. 1999. Pak to the future. Trends Cell Biol. 9:350-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein, C., H. Bernstein, C. M. Payne, and H. Garewal. 2002. DNA repair/pro-apoptotic dual-role proteins in five major DNA repair pathways: fail-safe protection against carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res. 511:145-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boshoff, C., T. F. Schulz, M. M. Kennedy, A. K. Graham, C. Fisher, A. Thomas, J. O. McGee, R. A. Weiss, and J. J. O'Leary. 1995. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infects endothelial and spindle cells. Nat. Med. 1:1274-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buki, K. G., P. I. Bauer, A. Hakam, and E. Kun. 1995. Identification of domains of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase for protein binding and self-association. J. Biol. Chem. 270:3370-3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cervellera, M. N., and A. Sala. 2000. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase is a B-MYB coactivator. J. Biol. Chem. 275:10692-10696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cesarman, E., Y. Chang, P. S. Moore, J. W. Said, and D. M. Knowles. 1995. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:1186-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chadee, D. N., T. Yuasa, and J. M. Kyriakis. 2002. Direct activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase MEKK1 by the Ste20p homologue GCK and the adapter protein TRAF2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:737-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang, P. J., D. Shedd, L. Gradoville, M. S. Cho, L. W. Chen, J. Chang, and G. Miller. 2002. Open reading frame 50 protein of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus directly activates the viral PAN and K12 genes by binding to related response elements. J. Virol. 76:3168-3178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang, Y., E. Cesarman, M. S. Pessin, F. Lee, J. Culpepper, D. M. Knowles, and P. S. Moore. 1994. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science 266:1865-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, J., K. Ueda, S. Sakakibara, T. Okuno, C. Parravicini, M. Corbellino, and K. Yamanishi. 2001. Activation of latent Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus by demethylation of the promoter of the lytic transactivator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4119-4124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, J., K. Ueda, S. Sakakibara, T. Okuno, and K. Yamanishi. 2000. Transcriptional regulation of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viral interferon regulatory factor gene. J. Virol. 74:8623-8634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiarugi, A. 2002. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase: killer or conspirator? The "suicide hypothesis' revisited. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 23:122-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clambey, E. T., H. W. Virgin IV, and S. H. Speck. 2000. Disruption of the murine gammaherpesvirus 68 M1 open reading frame leads to enhanced reactivation from latency. J. Virol. 74:1973-1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Amours, D., S. Desnoyers, I. D'Silva, and G. G. Poirier. 1999. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation reactions in the regulation of nuclear functions. Biochem. J. 342:249-268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dan, I., N. M. Watanabe, and A. Kusumi. 2001. The Ste20 group kinases as regulators of MAP kinase cascades. Trends Cell Biol. 11:220-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng, H., A. Young, and R. Sun. 2000. Auto-activation of the rta gene of human herpesvirus-8/Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Gen. Virol. 81:3043-3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duan, W., S. Wang, S. Liu, and C. Wood. 2001. Characterization of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus-8 ORF57 promoter. Arch. Virol. 146:403-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gradoville, L., J. Gerlach, E. Grogan, D. Shedd, S. Nikiforow, C. Metroka, and G. Miller. 2000. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus open reading frame 50/Rta protein activates the entire viral lytic cycle in the HH-B2 primary effusion lymphoma cell line. J. Virol. 74:6207-6212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gwack, Y., H. J. Baek, H. Nakamura, S. H. Lee, M. Meisterernst, R. G. Roeder, and J. U. Jung. 2003. Principal role of TRAP/mediator and SWI/SNF complexes in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus RTA-mediated lytic reactivation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:2055-2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gwack, Y., H. Byun, S. Hwang, C. Lim, and J. Choe. 2001. CREB-binding protein and histone deacetylase regulate the transcriptional activity of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus open reading frame 50. J. Virol. 75:1909-1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gwack, Y., S. Hwang, C. Lim, Y. S. Won, C. H. Lee, and J. Choe. 2002. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus open reading frame 50 stimulates the transcriptional activity of STAT3. J. Biol. Chem. 277:6438-6442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeong, J., J. Papin, and D. Dittmer. 2001. Differential regulation of the overlapping Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus vGCR (orf74) and LANA (orf73) promoters. J. Virol. 75:1798-1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kannan, P., Y. Yu, S. Wankhade, and M. A. Tainsky. 1999. PolyADP-ribose polymerase is a coactivator for AP-2-mediated transcriptional activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:866-874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kyriakis, J. M. 1999. Signaling by the germinal center kinase family of protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 274:5259-5262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, M., J. MacKey, S. C. Czajak, R. C. Desrosiers, A. A. Lackner, and J. U. Jung. 1999. Identification and characterization of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K8.1 virion glycoprotein. J. Virol. 73:1341-1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lukac, D. M., L. Garibyan, J. R. Kirshner, D. Palmeri, and D. Ganem. 2001. DNA binding by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic switch protein is necessary for transcriptional activation of two viral delayed early promoters. J. Virol. 75:6786-6799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukac, D. M., J. R. Kirshner, and D. Ganem. 1999. Transcriptional activation by the product of open reading frame 50 of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is required for lytic viral reactivation in B cells. J. Virol. 73:9348-9361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lukac, D. M., R. Renne, J. R. Kirshner, and D. Ganem. 1998. Reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection from latency by expression of the ORF 50 transactivator, a homolog of the EBV R protein. Virology 252:304-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masson, M., C. Niedergang, V. Schreiber, S. Muller, J. Menissier-de Murcia, and G. de Murcia. 1998. XRCC1 is specifically associated with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and negatively regulates its activity following DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:3563-3571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meisterernst, M., G. Stelzer, and R. G. Roeder. 1997. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase enhances activator-dependent transcription in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:2261-2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plaza, S., M. Aumercier, M. Bailly, C. Dozier, and S. Saule. 1999. Involvement of poly(ADP-ribose)-polymerase in the Pax-6 gene regulation in neuroretina. Oncogene 18:1041-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Renne, R., W. Zhong, B. Herndier, M. McGrath, N. Abbey, D. Kedes, and D. Ganem. 1996. Lytic growth of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in culture. Nat. Med. 2:342-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russo, J. J., R. A. Bohenzky, M. C. Chien, J. Chen, M. Yan, D. Maddalena, J. P. Parry, D. Peruzzi, I. S. Edelman, Y. Chang, and P. S. Moore. 1996. Nucleotide sequence of the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (HHV8). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:14862-14867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakakibara, S., K. Ueda, J. Chen, T. Okuno, and K. Yamanishi. 2001. Octamer-binding sequence is a key element for the autoregulation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus ORF50/Lyta gene expression. J. Virol. 75:6894-6900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song, M. J., X. Li, H. J. Brown, and R. Sun. 2002. Characterization of interactions between RTA and the promoter of polyadenylated nuclear RNA in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8. J. Virol. 76:5000-5013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevenson, P. G., J. S. May, X. G. Smith, S. Marques, H. Adler, U. H. Koszinowski, J. P. Simas, and S. Efstathiou. 2002. K3-mediated evasion of CD8(+) T cells aids amplification of a latent gamma-herpesvirus. Nat. Immunol. 3:733-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun, R., S. F. Lin, L. Gradoville, Y. Yuan, F. Zhu, and G. Miller. 1998. A viral gene that activates lytic cycle expression of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:10866-10871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun, R., S. F. Lin, K. Staskus, L. Gradoville, E. Grogan, A. Haase, and G. Miller. 1999. Kinetics of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus gene expression. J. Virol. 73:2232-2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tassi, E., Z. Biesova, P. P. Di Fiore, J. S. Gutkind, and W. T. Wong. 1999. Human JIK, a novel member of the STE20 kinase family that inhibits JNK and is negatively regulated by epidermal growth factor. J. Biol. Chem. 274:33287-33295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tulin, A., and A. Spradling. 2003. Chromatin loosening by poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase (PARP) at Drosophila puff loci. Science 299:560-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Virgin, H. W., IV, P. Latreille, P. Wamsley, K. Hallsworth, K. E. Weck, A. J. Dal Canto, and S. H. Speck. 1997. Complete sequence and genomic analysis of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 71:5894-5904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vispe, S., T. M. Yung, J. Ritchot, H. Serizawa, and M. S. Satoh. 2000. A cellular defense pathway regulating transcription through poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation in response to DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:9886-9891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, S., S. Liu, M. H. Wu, Y. Geng, and C. Wood. 2001. Identification of a cellular protein that interacts and synergizes with the RTA (ORF50) protein of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in transcriptional activation. J. Virol. 75:11961-11973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu, T. T., L. Tong, T. Rickabaugh, S. Speck, and R. Sun. 2001. Function of Rta is essential for lytic replication of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J. Virol. 75:9262-9273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu, T. T., E. J. Usherwood, J. P. Stewart, A. A. Nash, and R. Sun. 2000. Rta of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 reactivates the complete lytic cycle from latency. J. Virol. 74:3659-3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yustein, J. T., L. Xia, J. M. Kahlenburg, D. Robinson, D. Templeton, and H. J. Kung. 2003. Comparative studies of a new subfamily of human Ste20-like kinases: homodimerization, subcellular localization, and selective activation of MKK3 and p38. Oncogene 22:6129-6141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]