Abstract

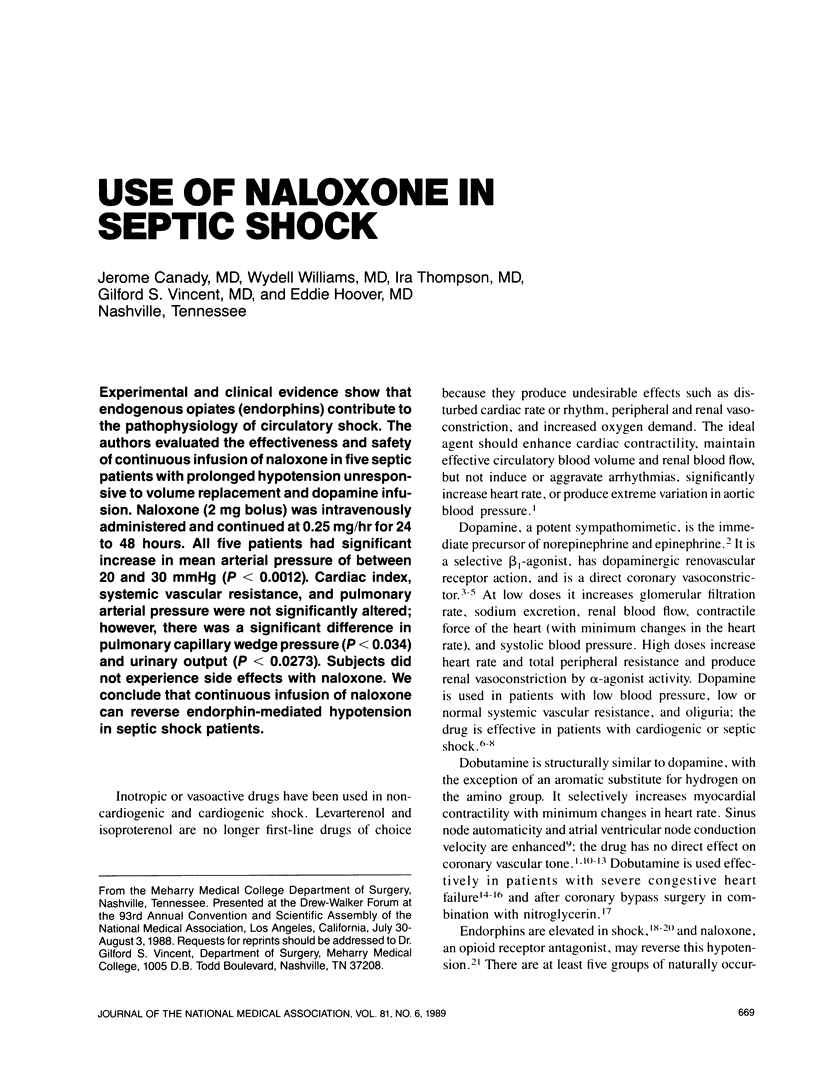

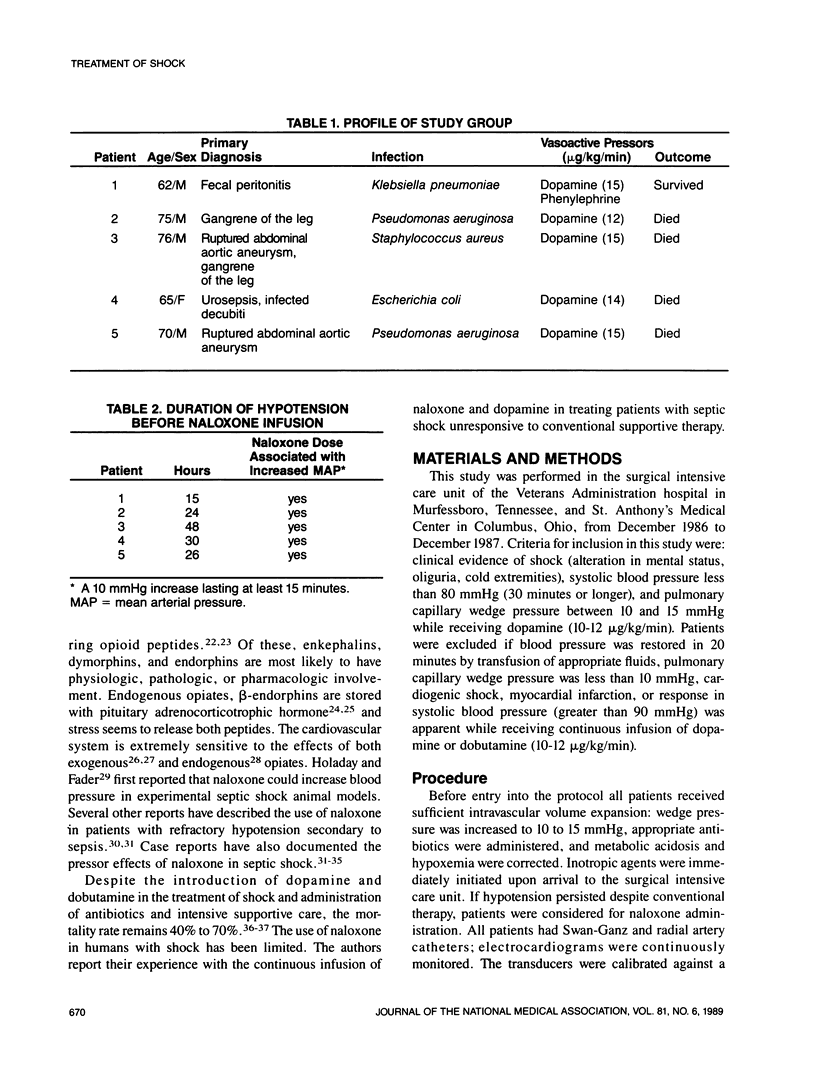

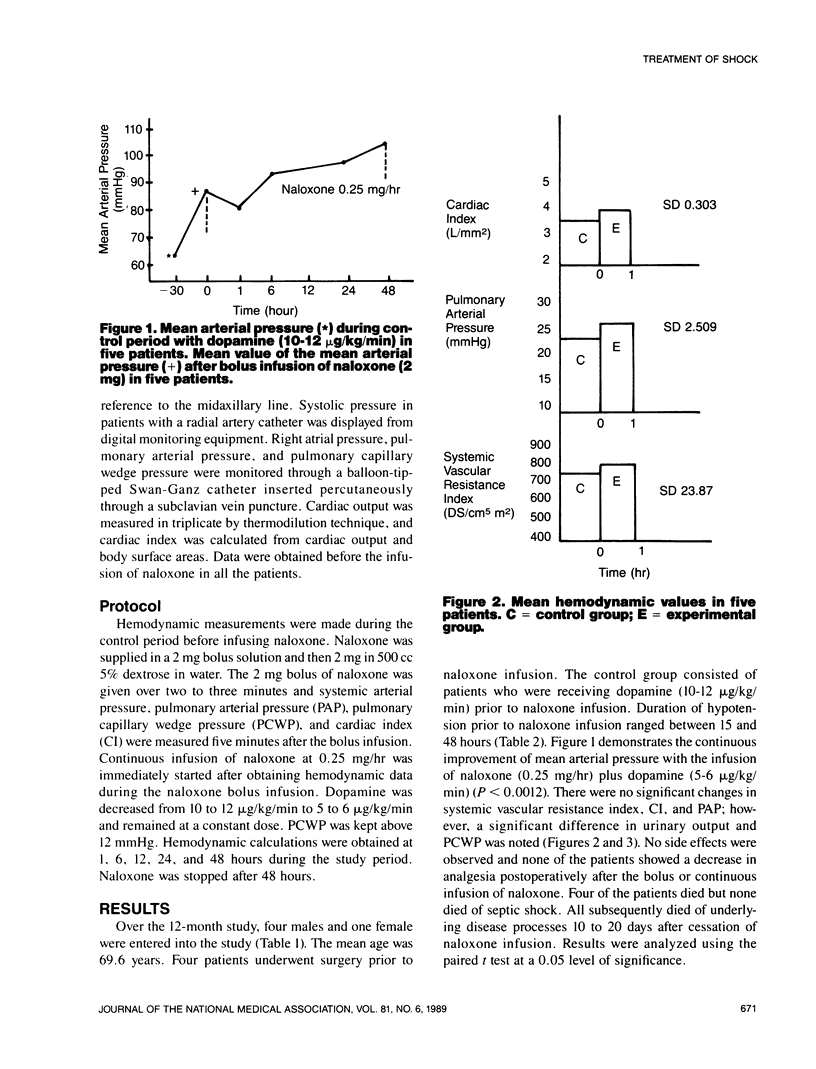

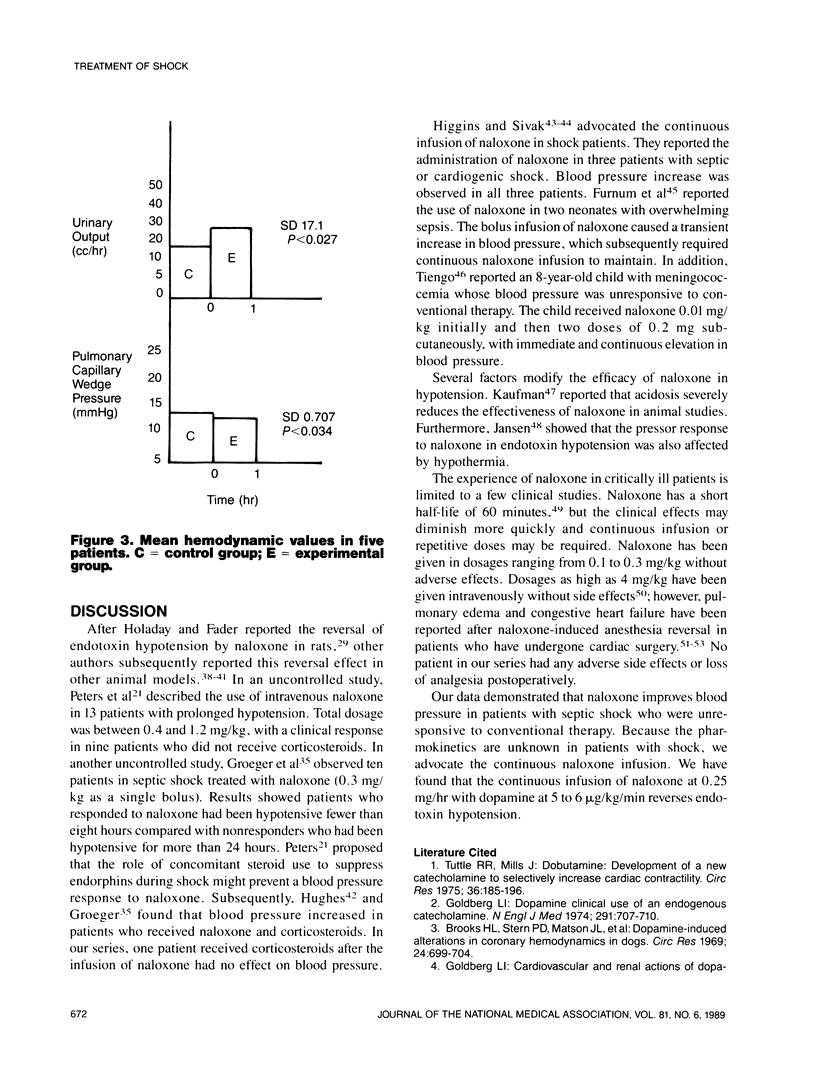

Experimental and clinical evidence show that endogenous opiates (endorphins) contribute to the pathophysiology of circulatory shock. The authors evaluated the effectiveness and safety of continuous infusion of naloxone in five septic patients with prolonged hypotension unresponsive to volume replacement and dopamine infusion. Naloxone (2 mg bolus) was intravenously administered and continued at 0.25 mg/hr for 24 to 48 hours. All five patients had significant increase in mean arterial pressure of between 20 and 30 mmHg (P less than 0.0012). Cardiac index, systemic vascular resistance, and pulmonary arterial pressure were not significantly altered; however, there was a significant difference in pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (P less than 0.034) and urinary output (P less than 0.0273). Subjects did not experience side effects with naloxone. We conclude that continuous infusion of naloxone can reverse endorphin-mediated hypotension in septic shock patients.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brooks H. L., Stein P. D., Matson J. L., Hyland J. W. Dopamine-induced alterations in coronary hemodynamics in dogs. Circ Res. 1969 May;24(5):699–704. doi: 10.1161/01.res.24.5.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EVANS A. G. J., NASMYTH P. A., STEWART H. C. The fall of blood pressure caused by intravenous morphine in the rat and the cat. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1952 Dec;7(4):542–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1952.tb00720.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden A. I., Holaday J. W. Naloxone treatment of endotoxin shock: stereospecificity of physiologic and pharmacologic effects in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1980 Mar;212(3):441–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden A. I., Holaday J. W. Opiate antagonists: a role in the treatment of hypovolemic shock. Science. 1979 Jul 20;205(4403):317–318. doi: 10.1126/science.451606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden A. I., Jacobs T. P., Mougey E., Holaday J. W. Endorphins in experimental spinal injury: therapeutic effect of naloxone. Ann Neurol. 1981 Oct;10(4):326–332. doi: 10.1002/ana.410100403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flacke J. W., Flacke W. E., Williams G. D. Acute pulmonary edema following naloxone reversal of high-dose morphine anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1977 Oct;47(4):376–378. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197710000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flórez J., Mediavilla A. Respiratory and cardiovascular effects of met-enkephalin applied to the ventral surface of the brain stem. Brain Res. 1977 Dec 23;138(3):585–900. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90699-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W. L., Menke J. A., Barson W. J., Miller R. R. Continuous naloxone infusion in two neonates with septic shock. J Pediatr. 1984 Oct;105(4):649–651. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80441-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOKHALE S. D., GULATI O. D., JOSHI N. Y. EFFECT OF SOME BLOCKING DRUGS ON THE PRESSOR RESPONSE TO PHYSOSTIGMINE IN THE RAT. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1963 Oct;21:273–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1963.tb01526.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz W., Swan H. J. Measurement of blood flow by thermodilution. Am J Cardiol. 1972 Feb;29(2):241–246. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(72)90635-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg L. I. Dopamine--clinical uses of an endogenous catecholamine. N Engl J Med. 1974 Oct 3;291(14):707–710. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197410032911405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groeger J. S., Carlon G. C., Howland W. S. Naloxone in septic shock. Crit Care Med. 1983 Aug;11(8):650–654. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198308000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiha N. H., Cohn J. N., Mikulic E., Franciosa J. A., Limas C. J. Treatment of refractory heart failure with infusion of nitroprusside. N Engl J Med. 1974 Sep 19;291(12):587–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197409192911201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin R., Vargo T., Rossier J., Minick S., Ling N., Rivier C., Vale W., Bloom F. beta-Endorphin and adrenocorticotropin are selected concomitantly by the pituitary gland. Science. 1977 Sep 30;197(4311):1367–1369. doi: 10.1126/science.197601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins T. L., Sivak E. D., O'Neil D. M., Graves J. W., Foutch D. G. Reversal of hypotension by continuous naloxone infusion in a ventilator-dependent patient. Ann Intern Med. 1983 Jan;98(1):47–48. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-1-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins T. L., Sivak E. D. Reversal of hypotension with naloxone. Cleve Clin Q. 1981 Summer;48(2):283–288. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.48.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holaday J. W., Faden A. I. Naloxone reversal of endotoxin hypotension suggests role of endorphins in shock. Nature. 1978 Oct 5;275(5679):450–451. doi: 10.1038/275450a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J., Kosterlitz H. W. Opioid Peptides: introduction. Br Med Bull. 1983 Jan;39(1):1–3. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a071781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen H. F., Pugh J. L., Lutherer L. O. Reduced ambient temperature blocks the ability of naloxone to prevent endotoxin-induced hypotension. Adv Shock Res. 1982;7:117–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewitt D., Birkhead J., Mitchell A., Dollery C. Clinical cardiovascular pharmacology of dobutamine. A selective inotropic catecholamine. Lancet. 1974 Aug 17;2(7877):363–367. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91754-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J. J. Acidosis lowers in-vivo potency of narcotics and narcotic antagonists and can even abolish narcotic antagonist activity. Lancet. 1982 Mar 6;1(8271):559–560. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)92064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leier C. V., Heban P. T., Huss P., Bush C. A., Lewis R. P. Comparative systemic and regional hemodynamic effects of dopamine and dobutamine in patients with cardiomyopathic heart failure. Circulation. 1978 Sep;58(3 Pt 1):466–475. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.58.3.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leier C. V., Webel J., Bush C. A. The cardiovascular effects of the continuous infusion of dobutamine in patients with severe cardiac failure. Circulation. 1977 Sep;56(3):468–472. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.56.3.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb H. S., Bredakis J., Gunner R. M. Superiority of dobutamine over dopamine for augmentation of cardiac output in patients with chronic low output cardiac failure. Circulation. 1977 Feb;55(2):375–378. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.55.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan J. E., Jr, Barnes M. W., Finland M. Bacteremia at Boston City Hospital: Occurrence and mortality during 12 selected years (1935-1972), with special reference to hospital-acquired cases. J Infect Dis. 1975 Sep;132(3):316–335. doi: 10.1093/infdis/132.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meretoja O. A. Haemodynamic effects of combined nitroglycerin- and dobutamine-infusions after coronary by-pass surgery. With one nitroglycerin-related complication. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1980 Jun;24(3):211–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1980.tb01536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis L. L., Hickey P. R., Clark T. A., Dixon W. M. Ventricular irritability associated with the use of naloxone hydrochloride. Two case reports and laboratory assessment of the effect of the drug on cardiac excitability. Ann Thorac Surg. 1974 Dec;18(6):608–614. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)64408-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulic E., Cohn J. N., Franciosa J. A. Comparative hemodynamic effects of inotropic and vasodilator drugs in severe heart failure. Circulation. 1977 Oct;56(4 Pt 1):528–533. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.56.4.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley J. S. Chemistry of opioid peptides. Br Med Bull. 1983 Jan;39(1):5–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a071790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naloxone in shock. Lancet. 1980 Dec 20;2(8208-8209):1360–1360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngai S. H., Berkowitz B. A., Yang J. C., Hempstead J., Spector S. Pharmacokinetics of naloxone in rats and in man: basis for its potency and short duration of action. Anesthesiology. 1976 May;44(5):398–401. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197605000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama T., Yao M., Ishihara H., Kudo T., Kudo M., Matsuki A. Effects of hemorrhagic shock and endotoxin shock on plasma levels of beta-endorphin and beta-lipotropin. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1983;111:185–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlroth M. G., Harrison D. C. Cardiogenic shock: a review. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1969 Jul-Aug;10(4):449–467. doi: 10.1002/cpt1969104449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters W. P., Johnson M. W., Friedman P. A., Mitch W. E. Pressor effect of naloxone in septic shock. Lancet. 1981 Mar 7;1(8219):529–532. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92865-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees B. I. Secondary involvement of the penis by rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1975 Jan;62(1):77–79. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800620118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds D. G., Gurll N. J., Vargish T., Lechner R. B., Faden A. I., Holaday J. W. Blockade of opiate receptors with naloxone improves survival and cardiac performance in canine endotoxic shock. Circ Shock. 1980;7(1):39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossier J., French E. D., Rivier C., Ling N., Guillemin R., Bloom F. E. Foot-shock induced stress increases beta-endorphin levels in blood but not brain. Nature. 1977 Dec 15;270(5638):618–620. doi: 10.1038/270618a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoner J. D., 3rd, Bolen J. L., Harrison D. C. Comparison of dobutamine and dopamine in treatment of severe heart failure. Br Heart J. 1977 May;39(5):536–539. doi: 10.1136/hrt.39.5.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn W. R., Phelan P. Response to naloxone in septic shock. Lancet. 1982 Jan 16;1(8264):167–167. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiengo M. Naloxone in irreversible shock. Lancet. 1980 Sep 27;2(8196):690–690. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92723-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuttle R. R., Mills J. Dobutamine: development of a new catecholamine to selectively increase cardiac contractility. Circ Res. 1975 Jan;36(1):185–196. doi: 10.1161/01.res.36.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargish T., Reynolds D. G., Gurll N. J., Lechner R. B., Holaday J. W., Faden A. I. Naloxone reversal of hypovolemic shock in dogs. Circ Shock. 1980;7(1):31–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatner S. F., McRitchie R. J., Braunwald E. Effects of dobutamine on left ventricular performance, coronary dynamics, and distribution of cardiac output in conscious dogs. J Clin Invest. 1974 May;53(5):1265–1273. doi: 10.1172/JCI107673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. F., Sibbald W. J., Jaanimagi J. L. Hemodynamic effects of dopamine in critically ill septic patients. J Surg Res. 1976 Mar;20(3):163–172. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(76)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]