Abstract

Lithiated aryl carbamates (ArLi) bearing methoxy or fluoro substituents in the meta position are generated from lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) in THF, n-BuOMe, Me2NEt, dimethoxyethane (DME), N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA), N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylcyclohexanediamine (TMCDA), and hexamethylphosphoramide (HMPA). The aryllithiums are shown with 6Li, 13C, and 15N NMR spectroscopies to be monomers, ArLi-LDA mixed dimers, and ArLi-LDA mixed trimers, depending on the choice of solvent. Subsequent Snieckus-Fries rearrangements afford ArOLi-LDA mixed dimers and trimers of the resulting phenolates. Rate studies of the rearrangement implicate mechanisms based on monomers, mixed dimers, and mixed trimers.

Introduction

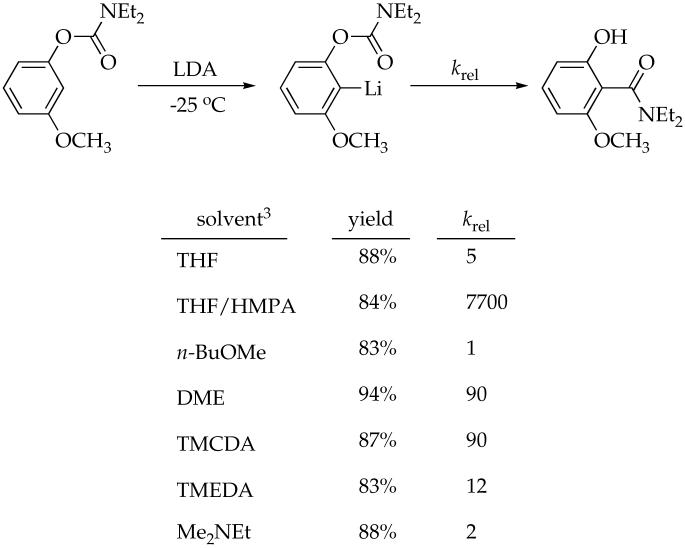

The anionic Snieckus-Fries rearrangement of aryl carbamates (eq 1) is a highly effective means of carrying out orthosubstitutions.1,2 Its popularity stems in large part from the dogged determination of Snieckus and coworkers to optimize the protocol and expand the scope of the reaction (which prompts us to cast a vote for adding Snieckus to the name).3-6

|

(1) |

Our interest in the Snieckus-Fries rearrangement was piqued by its probative value to study organolithium structure-reactivity relationships. Dimethylcarbamates bearing no meta substituent favor rapid intramolecular acyl transfer, affording insight into only the slow (rate limiting) ortholithiation step.7 By contrast, aryl carbamates bearing activating meta substituents (OCH3 or F) and bulky carbamoyl groups rapidly form a relatively stable intermediate aryllithium, allowing the rearrangement step to be examined as well.8

The consistently high yields accompanying eq 1 suggest that the choice of coordinating solvent is unimportant, but yields offer little insight into reactivity.9 The relative rate constants (krel) show that the choice of coordinating solvent markedly influences the rate of acyl transfer. Of course, solvent-dependent relative reactivities do not offer direct insights into underlying organolithium structures and reaction mechanisms.10,11

In a previous study we investigated reactivities and mechanisms of the ortholithiation of aryl carbamates, paying only limited attention to the acyl transfer.7 This paper focuses exclusively on the acyl transfer. We describe herein studies of solvent-dependent structures of the intermediate lithiated aryl carbamates and evidence of monomer-, mixed dimer-, and mixed trimer-based mechanisms for the rearrangement.12 The mixed trimer-based pathway may represent the first documented example of an organolithium reaction in which the rate-limiting transition structure is more highly aggregated than the reactants.13

Results

A series of structural, kinetic, and computational studies are described below. The choice of substrates was not as arbitrary as it might seem. Rate studies demand structural homogeneity to maximize the clarity of the results.11,14 The wide range of solvent-dependent reactivities foreshadowed by eq 1 demanded tinkering with the carbamoyl group and meta substituent to optimize the protocol for characterizing the starting aryllithiums and monitoring the rearrangements. General descriptions of protocols are followed by specific results organized according to solvent.

Structural Studies

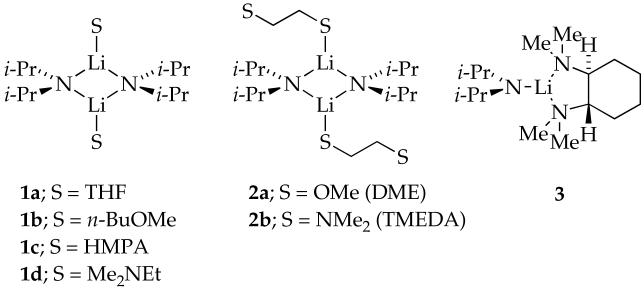

Lithium diisopropylamide (LDA), [6Li]LDA, and [6Li,15N]LDA were prepared as white crystalline solids.15,16 Previous investigations of LDA solvated by THF, n-BuOMe, THF/HMPA, and Me2NEt have revealed dimers 1a-d as the sole observable forms.3,17a,d Bifunctional ligands DME and TMEDA afford non-chelated dimers 2a and 2b, respectively.3,17b,c LDA solvated by TMCDA forms exclusively monomer 3.3,17b

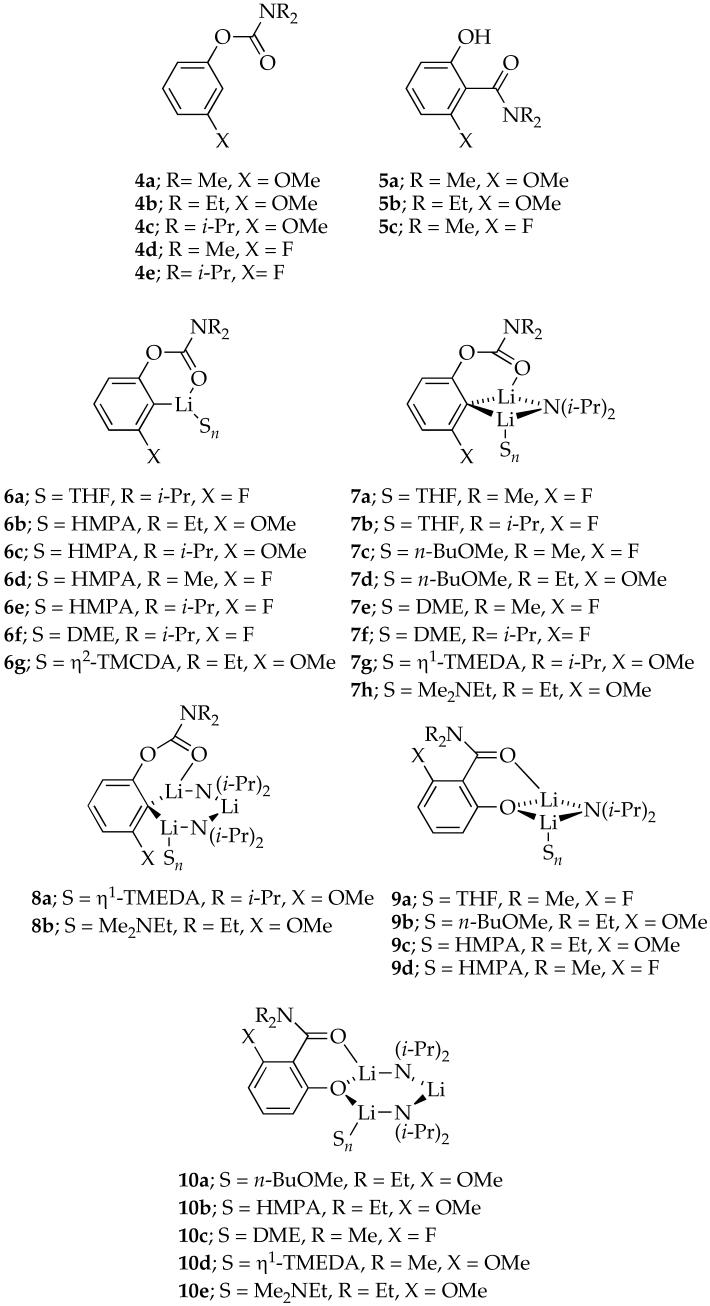

Aryllithiums 6a-g, mixed dimers 7a-h, and mixed trimers 8a-b were generated from aryl carbamates 4a-e18 using [6Li]LDA or [6Li,15N]LDA. Rearrangement in the presence of excess LDA affords phenolate-based mixed dimers 9a-d and mixed trimers 10a-e, which were synthesized independently by lithiating phenols 5a-c with excess [6Li,15N]LDA.

The structural assignments stem from splitting patterns observed using one-dimensional 6Li, 15N, and 13C NMR spectroscopies17a as well as 1J(6Li,15N)-resolved19 and 6Li,15N-HSQC NMR spectroscopies.20 Spectroscopic data are summarized in Table 1, and spectra are archived in supporting information. Although the structures and affiliated equilibria are complex, the methods used are well established. In lieu of detailed descriptions of the assignments for each solvent-substrate-aggregate combination, a few general statements should suffice.

Table 1.

| ArLi | Solvent | R | X | 6Li, δ (mult,1JLiN | 15N, δ(mult) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6ac | THF | i-Pr | F | 1.23 (s) | -- |

| 6cb | HMPA | i-Pr | OMe | 0.91 (s) | -- |

| 6e | HMPA | i-Pr | F | 0.75 (s) | -- |

| 6fc,b | DME | i-Pr | F | 1.65 (s) | -- |

| 6gb | TMCDA | Et | OMe | 2.18 (s) | -- |

| 7bb | THF | i-Pr | F | 1.71 (d, 5.3) | 76.3 (q) |

| 7db | n-BuOMe | Et | OMe | 1.85 (d, 5.8) | 75.8 (q) |

| 7fb | DME | i-Pr | F | 1.60 (d, 5.4) | 75.2 (q) |

| 7g | TMEDA | i-Pr | OMe | 2.01 (d, 4.9) | 75.3 (q) |

| 7h | Me2NEt | Et | OMe | 1.93 (d,5.2) | 75.3 (q) |

| 8a | TMEDA | i-Pr | OMe | 0.78 (d, 5.7) 2.49 (t, 4.7) 2.50 (d, 5.7) | 73.8 (tt) 75.3 (q) |

| 8b | Me2NEt | Et | OMe | 0.81 (d, 6.3) 2.24 (d, 6.0) 2.80 (t, 4.9) | 74.2 (tt) 74.3 (q) |

| 9a | THF | Me | F | 0.40 (d, 4.8) | 79.1 (q) |

| 9b | n-BuOMe | Et | OMe | 0.93 (d, 4.9) | 75.1 (q) |

| 9c | HMPA | Et | OMe | 0.54 (d, 5.3) | 76.5 (q) |

| 9d | HMPA | Me | F | 0.66 (d, 4.6) | 76.3 (q) |

| 10a | n-BuOMe | Et | OMe | 1.49 (d, 5.5) 1.55 (d, 6.2) 1.89 (t, 5.2) | 74.4 (--)d 74.1 (--)d |

| 10b | HMPA | Et | OMe | 1.09 (d, 5.3) 1.12 (d, 5.3) 1.58 (t, 4.6) | 73.2 (--)d 74.7 (tt) |

| 10c | DME | Me | F | 0.95 (d, 4.7) 0.98 (d, 5.1) 1.82 (t, 5.1) | 72.9 (q) 74.3 (q) |

| 10d | TMEDA | Me | OMe | 1.21 (d, 5.0) 1.67 (t, 4.9) | 74.9 (q) 75.1 (q) |

| 10e | Me2NEt | Et | OMe | 1.79 (d, 6.2) 1.79 (t, 5.1) 1.84 (d, 6.1) | 73.8 (tt) 74.3 (tt) |

Multiplicities are denoted as follows: s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; q, quintet. The chemical shifts are reported relative to 0.30 M 6LiCl/MeOH (δ 0.0 ppm) and neat Me2NEt (δ 25.7 ppm) at -90 °C. 13C NMR spectra are referenced to toluene-d8 (δ 137.9 ppm), pentane (δ 14.1 ppm), or THF (δ 67.6 ppm). Chemical shifts are reported in ppm, and J values are reported in Hz.

Carbon-13 resonances of the carbanionic carbons: 6c, δ 158.7 (br s); 6f, δ 150.1 (br d, JFC=7.7); 6g, δ 155.1 (t, JCLi=120.7); 7b, δ 150.5 (br d, JFC=123); 7d, δ 155.2 (q, JCLi=5.7); 7f, δ 154.6 (dq, JFC=123, JCLi=5.9).

1.0 equiv [6Li,15N]LDA.

Obscured by another resonance.

Some monomeric aryllithiums could be generated only by using 1.0 equiv of [6Li,15N]LDA in some cases (6a and 6f) whereas other monomers are formed even with excess [6Li,15N]LDA (6b-e and 6g). The anticipated 6Li-13C coupling is seen by 13C NMR spectroscopy in some cases, but most show only broad mounds. We have noted, however, that mixtures of such putative aryllithium monomers do not form ArLi-Ar’Li heteroaggregates,21 consistent with the monomer assignment.22 Previous spectroscopic studies strongly support a prevalence of monomers.23-25 Especially large 2JFC couplings (>100 Hz) in the 13C NMR spectra are similar to those observed in other orthofluorinated aryllithiums.7,23a,23b,26

Mixed dimers (7) available by using excess [6Li,15N]LDA show characteristic 6Li doublets and 15N quintets consistent with the Lia-Nb-Lic connectivity. The asymmetry imparted by chelation of the carbamate moiety could be observed as two 6Li resonances at very low temperature (<-125 °C). 13C NMR spectra show quintets due to coupling of the lithiated carbon to two 6Li nuclei and, in the case of the meta fluoro species, are further split by JFC coupling.

Mixed trimers (8) display three 6Li resonances in a 1:1:1 ratio, manifesting the 6Li-15N coupling consistent with a Lia-Nb-Lic-Nd-Lie subunit. Each mixed trimer also displays a triplet of triplets and a quintet in the 15N NMR spectrum. The asymmetry confirms the chelation of the carbamate moiety as drawn.

Phenolate mixed dimers (9) display characteristic 6Li doublets and 15N quintets that are consistent with Lia-Nb-Lic connectivity. The 6Li resonances of the phenolate mixed dimers are upfield from the aryllithium mixed dimers (7).

Phenolate mixed trimers (10) show three 6Li resonances as two doublets and one triplet in a 1:1:1 ratio. Two 15N resonances appear as either triplet of triplets or quintets.7,27

Rate Studies: General Methods11,28,29

The anionic Snieckus-Fries rearrangement was monitored using an in situ IR spectrometer fitted with a 30-bounce, silicon-tipped probe.30 The carbonyl group provided an excellent handle for following the loss of the aryllithium (monomer 6 or mixed dimer 7; 1670-1690 cm-1) and the growth of the aryl carboxamide (9 or 10; 1590-1610 cm-1). Pseudo-first-order conditions were established by maintaining the aryllithium concentration at 0.004 M. Mixed dimers 7a, 7d, and 7e and monomers 6b, 6d, and 6g were generated in situ with excess LDA. Solvent concentrations were high, yet adjustable, using a cosolvent (pentane, hexane, or toluene).31 The resulting pseudo-first-order rate constants (kobsd) are independent of the initial concentration of the aryllithium, confirming a first-order dependence. The decays also follow first-order dependencies, as shown by least-squares fits to the nonlinear Noyes equation.32 Phenolate-based mixed aggregates 9 and 10 or any unforeseen conversion-dependent changes were shown to be inconsequential under the pseudo-first-order conditions by reestablishing the baseline at the end of a run, injecting a second aliquot of aryl carbamate, and confirming that the first and second rate constants are equivalent (±10%). The reaction orders are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of Rate Studies for the Anionic Snieckus-Fries Rearrangement

| ArLi | Solvent | R | X | Temperature °C | LDA Order | Solvent Order |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7a | THF | Me | F | -40 | 0 -0.48±0.04 |

+1.08±0.05a +2.4±0.6b |

| 7d | n-BuOMe | Et | OMe | 15 | 0c +0.49±0.09d |

0 -1.10±0.05 |

| 6be | HMPA | Et | OMe | -65 | 0 | +0.8±0.1 |

| 6de | HMPA | Me | F | -78 | 0 | +1.2±0.3 |

| 7e | DME | Me | F | -60 | 0 | 0 |

| 6g | TMCDA | Et | OMe | -25 | 0 | 0 |

0.42 M LDA.

0.098 M LDA.

7.0 M n-BuOMe.

1.3 M n-BuOMe.

The order in THF cosolvent is zero.

Computations

Calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) were performed at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory using Gaussian 03 and visualized with GaussView 3.09.33 Gibbs free energies (ΔGo, kcal/mol) include thermal corrections at 298 K. Calculated transition structures were shown to be legitimate saddle points by the existence of a single imaginary frequency. The alkyl groups on the carbamate were modeled as methyl groups, and LDA was modeled as lithium dimethylamide. THF and n-BuOMe were modeled as dimethylether (Me2O). TMCDA was modeled as TMEDA. The results, comprising 43 calculated reactants and 23 calculated transition structures, are archived in supporting information. Selected observations are presented in the context of the specific solvents as described below.

THF

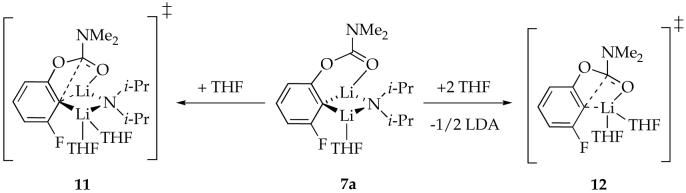

The metalation of 4d and subsequent rearrangement in THF solution were studied previously;7 the results are summarized to provide context. Rearrangement of mixed dimer 7a in THF and excess LDA affords LDA-lithium phenolate mixed dimer 9a. The idealized rate law34 for the rearrangement (eq 2) is consistent with parallel pathways via transition structures 11 and 12 (eq 3). Computations using Me2NLi/Me2O suggest that 7a is a monosolvated mixed dimer as drawn and they support 11 and 12 implicated by the rate law are reasonable.

| (2) |

|

(3) |

n-BuOMe

Lithiation of 4b with excess LDA/n-BuOMe affords mixed dimer 7d as the only observable form. Solvation numbers cannot be ascertained spectroscopically, but DFT computations (see supporting information) suggest that monosolvated mixed dimer 7d is favored. Rearrangement of 7d in n-BuOMe with excess LDA affords LDA-lithium phenolate mixed dimer 9b and mixed trimer 10a.

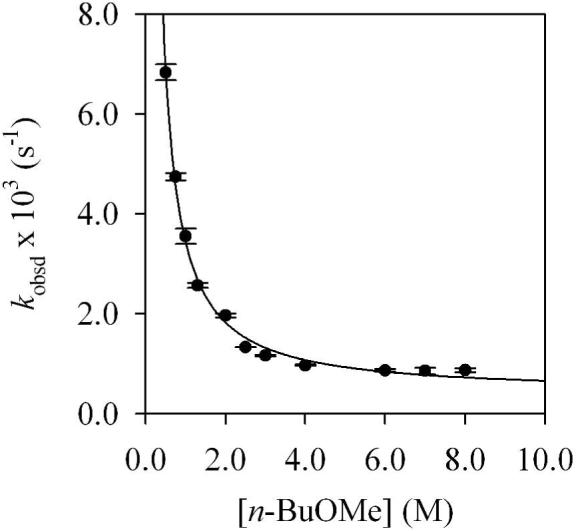

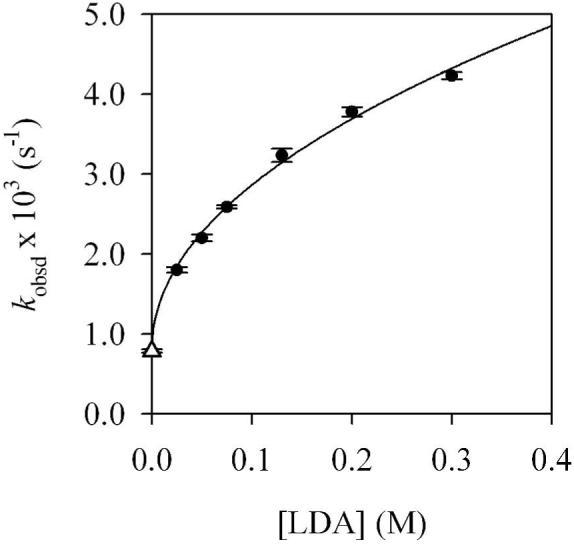

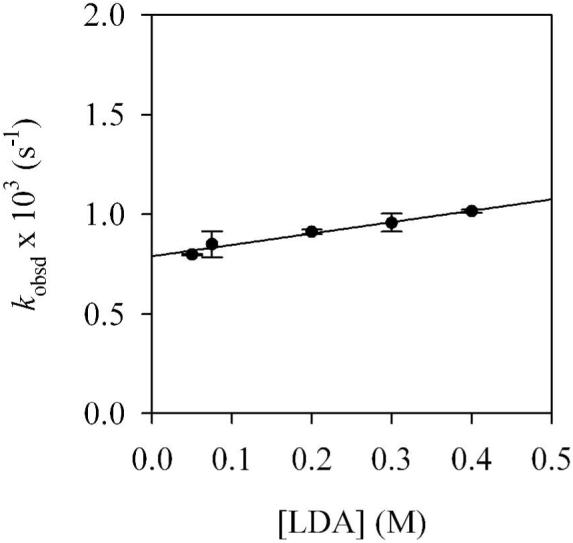

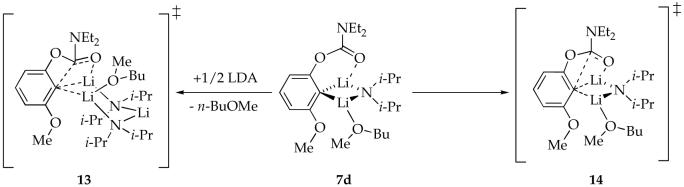

A plot of kobsd versus n-BuOMe concentration (Figure 1) for the rearrangement of mixed dimer 7d reveals two limiting behaviors: (1) an inverse dependence on n-BuOMe concentration, which is consistent with a mechanism requiring solvent dissociation, and (2) a zeroth-order dependence on n-BuOMe concentration, indicating a nondissociative mechanism. Plots of kobsd versus LDA concentration (Figures 2 and 3) show a positive half-order LDA dependence with a non-zero intercept at low n-BuOMe concentration (affiliated with the mechanism requiring solvent dissociation) and a zeroth-order LDA dependence at high n-BuOMe concentration (affiliated with the nondissociative mechanism). The reaction orders are consistent with the idealized rate law in eq 4, the mechanisms described generically in eq 5-7, and transition structures 13 and 14 (eq 8). Although mixed dimer 7d is the observable form, the Snieckus-Fries rearrangement is faster via mixed trimer-based transition structure 13. Calculations using Me2NLi/Me2O support both 13 and 14 as viable and suggest a greater preference for 13 (although such a non-isodesmic comparison should be made with caution if at all).

Figure 1.

Plot of kobsd versus [n-BuOMe] in pentane cosolvent for the rearrangement of 7d (0.004 M) by LDA (0.075 M) at 15 °C. The curve depicts an unweighted least-squares fit to kobsd = k[n-BuOMe]n + k’ (k = (3.0 ± 0.1) × 10-3, n = -1.10 ± 0.05, k’ = (4.1 ± 0.1) × 10-4).

Figure 2.

Plot of kobsd versus [LDA] in 1.3 M n-BuOMe/pentane for the rearrangement of 7d (0.004 M) at 15 °C. The curve depicts an unweighted least-squares fit to kobsd = k[LDA]n + k’ (k = (6.3 ± 0.2) × 10-3, n = 0.49 ± 0.09, k’ = (7.9 ± 0.2) × 10-4). k’ (see ·) was set to equal k’ in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Plot of kobsd versus [LDA] in 7.0 M n-BuOMe/pentane for the rearrangement of 7d (0.004 M) at 15 °C. The curve depicts an unweighted least-squares fit to kobsd = k[LDA] + k’ (k = (5.7 ± 0.8) × 10-4, k’ = (7.9 ± 0.2) × 10-4).

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

|

(8) |

HMPA

Metalation of 4c and 4e with LDA/HMPA/THF affords monomers 6c and 6e to the exclusion of mixed aggregates even with excess LDA.35 Unfortunately, 1JCLi coupling was not observed in the 13C NMR spectra. 6Li-31P coupling was also absent.36 Rearrangement of 6b in HMPA/THF and excess LDA affords LDA-lithium phenolate mixed dimer 9c and mixed trimer 10b. By contrast, rearrangement of 6d in HMPA/THF and excess LDA affords only LDA-lithium phenolate mixed dimer 9d.

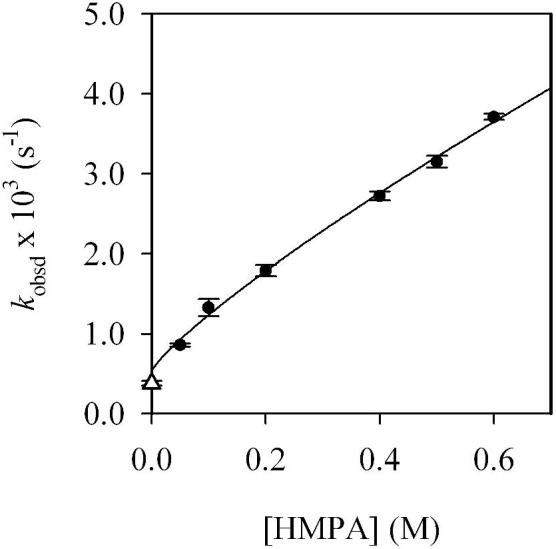

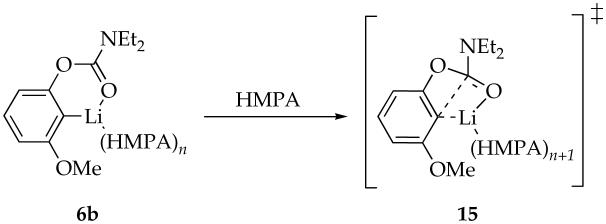

A plot of kobsd versus HMPA concentration (Figure 4) for the rearrangement of monomer 6b reveals a first-order dependence on HMPA concentration (with a relatively minor non-zero intercept) consistent with a dominant mechanism requiring solvation by one additional HMPA. Plots of kobsd versus LDA concentration and kobsd versus THF concentration reveal zeroth-order dependencies. The idealized rate law (eq 9) is consistent with the mechanisms described generically in eq 10 and transition structure 15. Analogous results are obtained using the fluorinated aryllithium monomer 6d, albeit at approximately threefold slower rearrangement rates, presumably due to inductive stabilization. Similar relative reactivities of MeO- and F-substituted aryllithiums were observed for the elimination of lithium halides to form benzynes.23b

Figure 4.

Plot of kobsd versus [HMPA] in 10.0 M THF/hexanes cosolvent for the rearrangement of 6b (0.004 M) by LDA (0.10 M) at -65 °C. The curve depicts an unweighted least-squares fit to kobsd = k[HMPA]n + k’ (k = (4.8 ± 0.2) × 10-3, n = 0.8 ± 0.1, k’ = (0.5 ± 0.2) × 10-3). Pseudo-first-order conditions not maintained at 0.05 M HMPA (·); data was omitted from the fit.

| (9) |

| (10) |

|

(11) |

DME

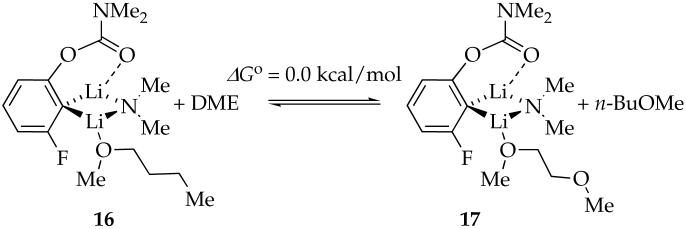

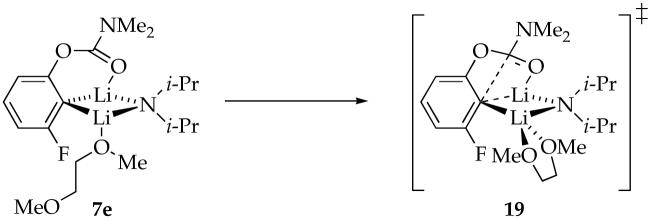

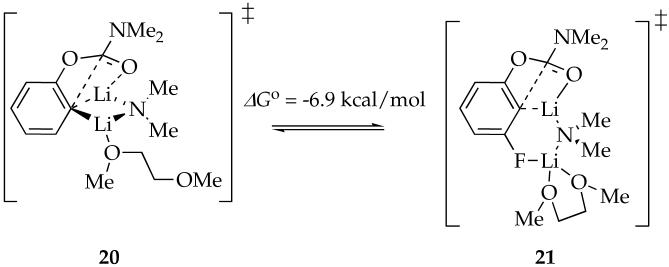

Lithiation of 4e with excess LDA/DME affords mixed dimer 7f as the sole observable aggregate. Unlike n-BuOMe, DME can be η1- or η2-coordinated in either the reactant or the transition structure. DFT computations indicate that (1) the substitution of n-BuOMe by η1-coordinated DME is nearly thermoneutral (eq 12), and (2) the η2-coordinated mixed dimer (18) is 5.1 kcal/mol favored over the η1-coordinated mixed dimer 17 (eq 13). One Li-C bond of η2-coordinated mixed dimer 18 is long (2.88 Å) with an accompanying shortening of the Li-F contact, however, suggesting cleavage (ring expansion) to accommodate the second oxygen of DME. Although the calculations are provocative, the veracity of 18 is undermined by experimental binding studies (discussed below). The open dimer motif of 18, however, resurfaces in the context of the rate studies described below.

|

(12) |

|

(13) |

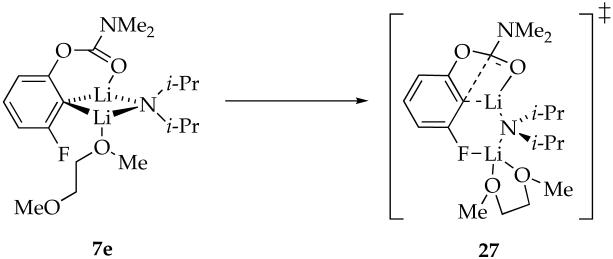

Plots of kobsd versus DME concentration and kobsd versus LDA concentration for the rearrangement of mixed dimer 7e reveal that the rearrangement is independent of both the DME and LDA concentrations. The reaction orders are consistent with the idealized rate law in eq 14, the mechanism described generically in eq 15, and transition structure 19. Notably, the reaction is much faster (approximately 90 times in eq 1) than it is in neat n-BuOMe. The origins of the acceleration are instructive about the role of chelation in the reactant 7e and transition structure 19.

| (14) |

| (15) |

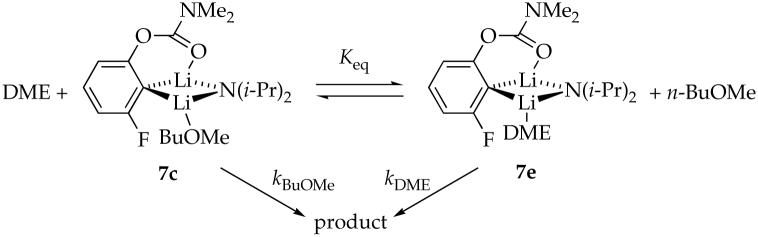

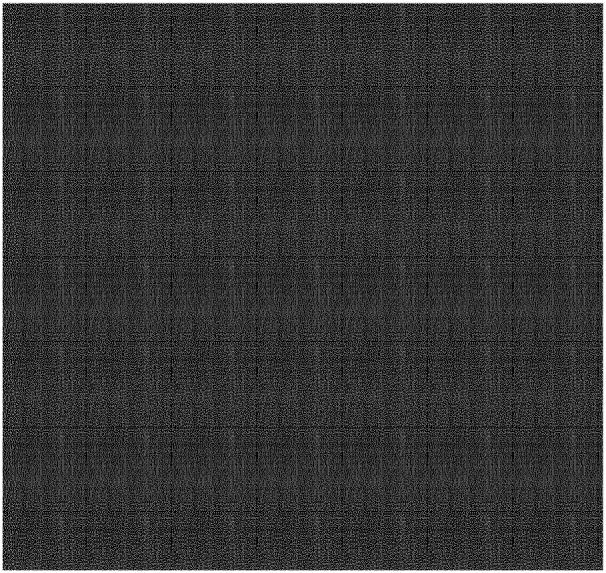

To understand the binding of DME in mixed dimer 7e we experimentally measured the relative binding energies of n-BuOMe and DME using a variation of a Job plot as follows.37 The rearrangement was carried out in DME/n-BuOMe mixtures according to Scheme 1. The total concentration of DME and n-BuOMe is held fixed at 5.0 M. The proportion is expressed as a mole fraction of DME, X. The observed rate constant is described as a function of the mole fraction according to eq 16. Three possible limiting results are illustrated in Figure 5. If n-BuOMe and DME bind equivalently (Keq = 1), a plot of kobsd versus mole fraction of DME will be linear. If chelation causes DME to be a superior ligand (Keq = 10), then the rate will rise and saturate at relatively low DME concentrations. In the unlikely event that n-BuOMe is superior to DME as a ligand for the mixed dimer (Keq = 0.1), then the opposite curvature will be observed.

Scheme 1.

Figure 5.

Theoretical curves describing kobsd versus mole fraction of DME (XDME) according to eq 16 for mixtures of n-BuOMe and DME. The assumed values of Keq are as labeled. The relative rate constants for kBuOMe and kDME correspond to the left and right y-intercepts and arbitrarily assigned as 0.05 and 1.1, respectively.

| (16) |

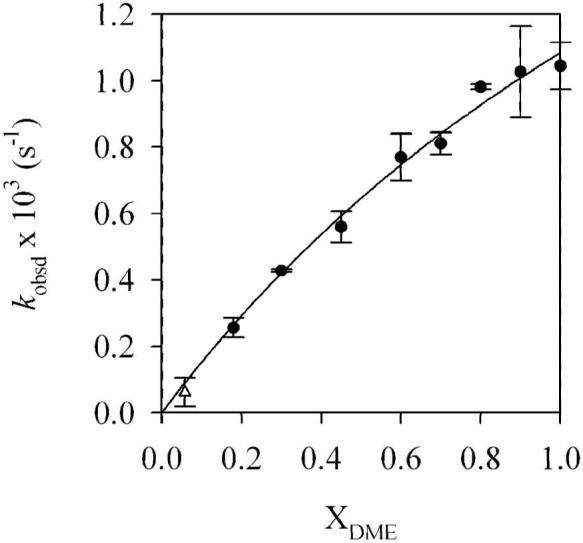

The data in Figure 6 shows curvature consistent with slight preference for solvation by DME compared to n-BuOMe (·Go = -0.2 kcal/mol). Therefore, either η2-coordinated DME is not present, or the η1 and η2 forms are isoenergetic. For the sake of further discussion, we depict 7e as containing unchelated DME as drawn. Although it is unclear why the computations (cf. 17 and 18) are so poorly predictive (the Me2NLi model could be at fault), the potential importance of the fluoro moiety to stabilize ring-expanded (open) dimers resurfaces (vide infra).

Figure 6.

Plot of kobsd versus mole fraction of DME (XDME) for the rearrangement of 7e (0.004 M) by LDA (0.05 M) at -60 °C. The donor solvent concentration is held constant ([DME]+[n-BuOMe]=5.0 M) using pentane as cosolvent. The curve depicts an unweighted least-squares fit to kobsd = (a + bx)/(1 + cx) (a = (0.0 ± 0.1) × 10-3, b = 1.6 ± 0.5, c = 0.5 ± 0.4) such that 1 + c = Keq (see eq 16). At low DME concentrations the lithium phenolate precipitated during the reaction; the value of kobsd (shown as *) was not included in the fit.

The nearly equal binding energies of n-BuOMe and DME in the reactant and 90-fold acceleration of the rearrangement suggest that DME is chelated in the transition state illustrated in eq 17. Such “hemilability” of DME-solvated LDA has been documented on several occasions.38 Computations show a significant preference for the chelated form with affiliated ring expansion, as illustrated in eq 18. (Recall that caution is warranted here.)

|

(17) |

|

(18) |

TMEDA and Me2NEt

TMEDA surprisingly affords both mixed dimer 7g and mixed trimer 8a. We believed that chelation would disfavor trimers. Is TMEDA failing to chelate? Possibly. Me2NEt, a non-chelating analog of TMEDA, also affords mixed dimer and trimer (7h and 8b). Fries rearrangement of the mixed dimers and trimers in TMEDA and Me2NEt with excess LDA yield trimers 10d and 10e. Rate studies using mixtures of starting materials are generally ill advised and were not pursued.

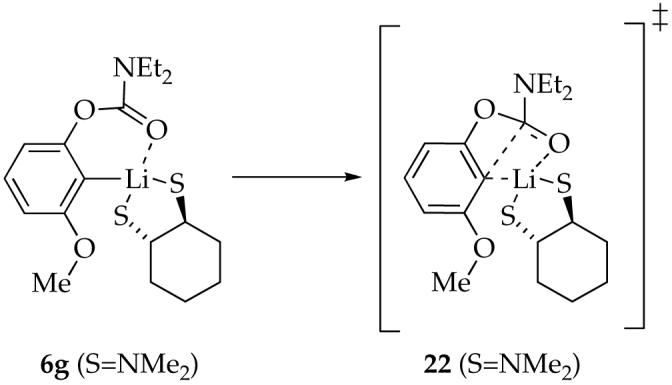

TMCDA

To study the role of a chelating diamine on the reaction rate and mechanism, we investigated TMCDA as a strongly coordinating model of TMEDA. Metalation of 4b with LDA/TMCDA affords only monomer 6g even with excess LDA. This substantial change in structure, when compared with the results using TMEDA, suggests that TMCDA chelates and TMEDA does not. Monomer 6g displays a characteristic 6Li singlet and 13C triplet. We were not, however, able to observe free and bound TMCDA using 13C NMR spectroscopy. DFT calculations using, ironically, TMEDA as a model for TMCDA suggest that the chelate is plausible. Rearrangement of 6g at -25 °C affords a complex mixture of phenoxides. The complexity of the product distribution does not preclude detailed rate studies, however.

Plots of kobsd versus TMCDA concentration and kobsd versus LDA concentration for the rearrangement of monomer 6g reveal zeroth-order dependencies. The idealized rate law in eq 19 is consistent with a single mechanism requiring no net changes in aggregation or solvation described generically in eq 20 and transition structure 22 (eq 21).39

| (19) |

| (20) |

|

(21) |

Discussion

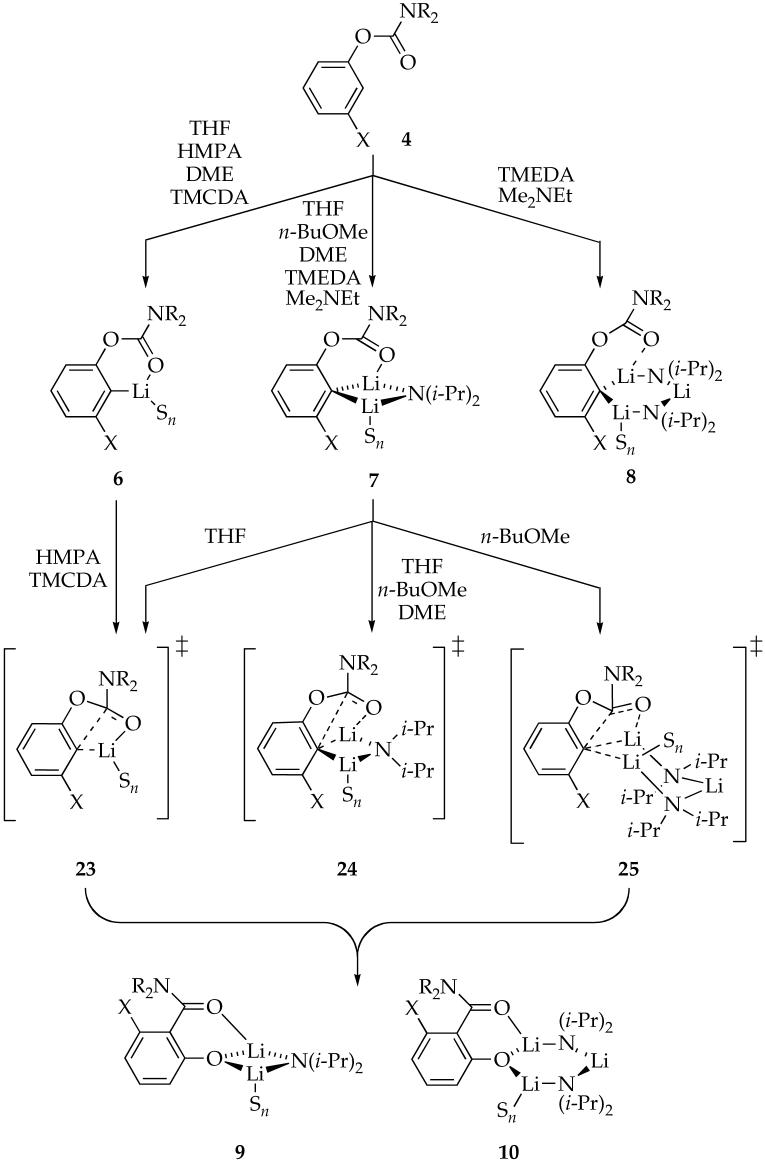

We introduced the work described herein with solvent-dependent yields and rates of an archetypal Snieckus-Fries rearrangement shown in eq 1. Noting that yields do not shed light on rates, and simple relative rate constants do not shed light on causative organolithium structures and mechanisms, we embarked on studies of solvent-dependent structure-reactivity relationships. Control over both reactant structures and reaction rates--two important requisites of transparent mechanistic studies--demanded taking liberties in the choice of carbamoyl group and meta substituent. A coherent summary of the results, however, requires that we also take some linguistic liberties by largely ignoring the substrate variations and focusing on the influence of solvent. Scheme 2 summarizes these results. We do not wish to imply, however, that fluoro and methoxy moieties are interchangeable; substrate-dependent changes in mechanism may lurk undetected under the surface. The structures of the reactants assigned spectroscopically and the putative transition structures are supported by computations that are largely archived in supporting information.

Scheme 2.

Solution Structures

The solvent dependent structures of lithiated aryl carbamates follow fairly conventional patterns. The most strongly coordinating solvents such as TMCDA and HMPA promote monomers (6). The most strongly coordinating ethereal solvent (THF) can afford monomers, but affords mixed dimers (7) with excess LDA. The less strongly coordinating n-BuOMe promotes exclusively mixed dimers, whereas the very weakly coordinating Me2NEt10a, 10c,17c,40 affords mixtures of mixed dimers and mixed trimers. (Mixed trimers are generally favored by weakly coordinating solvents because of their relatively low perlithium solvation numbers.)7,17a,41,42 Previous studies, however, have shown that TMEDA is superior to DME as a chelating ligand.43 By the simple paradigm that solvation energy correlates with aggregation state, therefore, DME appears to be a stronger ligand than TMEDA given that TMEDA affords mixed dimers and trimers. Indeed, tacit evidence suggests that TMEDA is too sterically demanding to chelate mixed dimer 7, causing TMEDA to function equivalently to the poorly coordinating Me2NEt.44 On many occasions we have found that the often-cited inverse correlation of solvent donicity (enthalpy of solvation) with aggregation number is flawed.42 In this study, however, the old paradigm holds true.

Despite its complexity, the structure of the aryllithium was successfully controlled as monomer 6 (TMCDA and HMPA) or mixed dimer 7 (THF, n-BuOMe, and DME) as required for detailed rate studies.

Monomer-Based Reactivity

In the case of HMPA, solvation by an additional HMPA ligand occurs en route to the transition state. Two solvents eliciting the highest overall reaction rates (eq 1) also foster monomer-based pathways; these results follow conventional wisdom. Previous studies had shown that THF-solvated mixed dimer 7 can rearrange either directly as the mixed dimer or via aryllithium monomer following deaggregation (see 12). In this instance, the high rates observed at low LDA concentrations arise from the monomer-based rearrangement. Overall, as one might expect, the two solvents that afford observable monomers even in the presence of excess LDA also promote reaction via monomer-based transition structures.

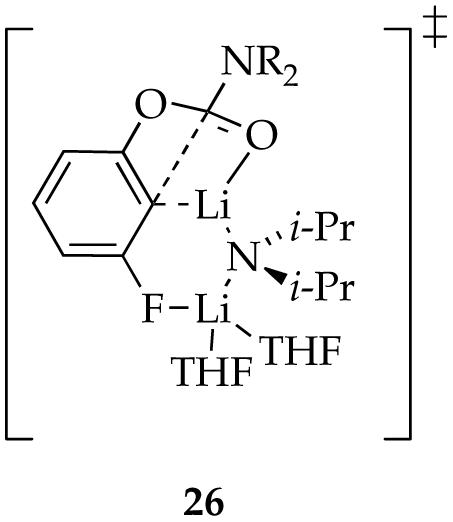

Mixed Dimer-Based Reactivity

Mixed dimers are reactive forms for all of the ethereal solvents (although not exclusively so). The results in THF present an interesting mechanistic issue. A first-order THF dependence affiliated with the mixed dimer-based reaction suggests that a disolvated dimer-based pathway is operative (eq 3). Computations reveal that one of the reasonable transition structures has an affiliated expanded ring resulting from chelation by the meta fluoro group. This expanded ring is illustrated in transition structure 26. We expressed some concern (vide supra) that the stability of such open dimers may be over-stated, but we find them interesting.

A similar effect shows up in rearrangements using DME. Binding studies show that DME and n-BuOMe are nearly equivalent ligands toward mixed dimer 7, whereas rate studies show that the rearrangement is 90 times faster in DME (eq 1). We infer, therefore, that DME is not chelated in the reactant but is chelated in the transition structure (eq 22). Marked rate accelerations stemming from the hemilability of DME are well documented for LDA-mediated metalations.38 Computations suggest that the rearrangement proceeds via open dimer 27. We hasten to add, however, that the computations exaggerated the stability of such an open dimer motif in the reactant. Nonetheless, this role of the meta substituent certainly provokes thought.

|

(22) |

Mixed Trimer-Based Reactivity

Metalations in n-BuOMe in which mixed dimer 7 is the observable reactant displayed an unusual (possibly unprecedented11) half order LDA dependence affiliated with a non-zero intercept. The intercept signifies a pathway requiring no LDA dissociation from mixed dimer 7, which implicates a mixed dimer-based pathway as discussed above. The half-order dependence, in conjunction with a zeroth-order n-BuOMe dependence, suggests a rearrangement mechanism requiring an additional equivalent of LDA monomer. The stoichiometry must be that of a mixed trimer, [(i-Pr2NLi)2(ArLi)(n-BuOMe)]‡.14 Of the >100 rate laws measured for LDA-mediated reactions to date,11 we have not observed evidence of trimer- or mixed trimer-based reactivity. Moreover, we are unaware of any documented case of an organolithium reaction proceeding through a higher aggregation state than that observed for the reactants.13 It is also interesting that simply changing from THF to n-BuOMe, arguably a fairly subtle change, causes the rearrangement to change from LDA inhibited to LDA promoted.

Conclusions

Studies of ortholithiated aryl carbamates show that changes in solvent afford marked shifts in structure from aryllithium monomer to LDA-aryllithium mixed dimers and trimers. The mechanisms of the subsequent Snieckus-Fries rearrangements underscore a similar structural diversity in the rate limiting transition structures. In addition to the insights offered into the intimate interplay between solvent and substrate to control solution structure and reaction mechanism, one finds several surprising observations. The meta substituent on the aryl ring may play role in the rearrangement beyond simply stabilizing the aryllithium. Given the importance of substituted aryllithiums in synthesis,1,45 such an observation may be of significance. Also, an odd variant of hemilability46--the penchant for bifunctional ligands to accelerate organolithium reactions by chelating only in the rate-limiting transition state38,47--seems to have surfaced. As a final summarizing note, evidence that an observable mixed dimer undergoes further aggregation to mixed trimer, once again, suggests that the correlation of aggregation state and reactivity requires some care. Thus, one is reminded that relationships among product yields, reaction rates, aggregate structures, and reaction mechanisms are often quite complex.

Experimental Section

Reagents and Solvents

THF, n-BuOMe, DME, Me2NEt, hexane, toluene, and pentane were distilled from blue or purple solutions containing sodium benzophenone ketyl. The hydrocarbon stills contained 1% tetraglyme to dissolve the ketyl. HMPA was dried over CaH2 and vacuum distilled. TMEDA and TMCDA were recrystallized as their HCl salts39,48 and distilled from blue or purple solutions containing sodium benzophenone ketyl. Owing to evidence that commercially available R,R- and S,S-cyclohexanediamine may contain impurities that influence reaction rates, we resolved racemic trans-1,2-cyclohexanediamine following literature procedures.39 LDA, [6Li]LDA, and [6Li,15N]LDA were prepared from n-BuLi and i-Pr2NH and recrystallized.15 Air- and moisture-sensitive materials were manipulated under argon or nitrogen using standard glovebox, vacuum line, and syringe techniques. Solutions of n-BuLi and LDA were titrated using a literature method.49 Aryl carbamates 4a-e were prepared by literature procedures.18

NMR Spectroscopic Analyses

Standard 1H and 13C spectra were recorded on a 300 MHz spectrometer. 1H, 6Li, 13C, and 15N NMR spectra were recorded on a 400, 500, or 600 MHz spectrometers. The 6Li and 15N resonances are referenced to 0.30 M [6Li]LiCl/MeOH at -90 °C (0.0 ppm) and neat Me2NEt at -90 °C (25.7 ppm), respectively. The 13C resonances are referenced to the CH2O resonance of THF at -90 °C (67.6 ppm), the ipso resonance of toluene at 137.9 ppm, and methyl resonance of pentane at 14.1 ppm.

IR Spectroscopic Analyses

Spectra were recorded using an in situ IR spectrometer fitted with a 30-bounce, silicon-tipped probe. The spectra were acquired in 16 scans at a gain of 1 and a resolution of 8 cm-1. A representative reaction was carried out as follows: The IR probe was inserted through a nylon adapter and O-ring seal into an oven-dried, cylindrical flask fitted with a magnetic stir bar and a T-joint. The T-joint was capped by a septum for injections and a nitrogen line. Following evacuation under a full vacuum, heating, and flushing with nitrogen, the flask was charged with LDA (25 mg to 500 mg) in a solvent/co-solvent solution (9.9 mL) and cooled in a temperature-controlled bath. After recording a background spectrum, a carbamate was added to the LDA/solvent/co-solvent mixture from a dilute stock solution (100 μL, 0.400 M) with stirring. IR spectra were recorded over the course of the reaction. To account for mixing and temperature equilibration, spectra recorded in the first 1.5 min were discarded. All reactions were monitored to >5 half-lives.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health for direct support of this work and Merck, Pfizer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, R. W. Johnson, Aventis, Schering-Plough, and DuPont Pharmaceuticals (Bristol-Myers Squibb) for indirect support. We also thank Emil Lobkovsky for help with a crystal structure determination.

References and Footnotes

- 1.(a) Hartung CG, Snieckus V. In: Modern Arene Chemistry. Astruc D, editor. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2002. Chapter 10. [Google Scholar]; (b) Snieckus V. Chem. Rev. 1990;90:879. [Google Scholar]; (c) Taylor CM, Watson AJ. Curr. Org. Chem. 2004;8:623. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sibi MP, Snieckus V. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:1935. [Google Scholar]

- 3.LDA = lithium diisopropylamide (LDA); DME = 1,2-dimethoxyethane; TMEDA = N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylethylenediamine; TMCDA = trans-N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylcyclohexanediamine (optically pure R,R or S,S enantiomer); and HMPA = hexamethylphosphoramide.

- 4(a).The Lewis acid-mediated version was discovered by Fries in 1908.5a A photochemical variant was first described in 1960,5b and the anionic variant appears to have been first reported by Melvin in 1981.5c Snieckus reported the first anionic Fries rearrangement of an aryl carbamate in 1983.2

- 5.(a) Fries K, Finck G. Ber. 1908;41:2447. [Google Scholar]; (b) Anderson JC, Reese CB. Proc. Chem. Soc. 1960:217. [Google Scholar]; (c) Melvin LS. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981:3375. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Industrial applications:Nguyen T, Wicki MA, Snieckus V. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:7816. doi: 10.1021/jo049890h.Mhaske SB, Argade NP. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:4563. doi: 10.1021/jo040153v.Harfenist M, Joseph DM, Spence SC, Mcgee DPC, Reeves MD, White HL. J. Med. Chem. 1997;40:2466. doi: 10.1021/jm9608063.Piettre A, Chevenier E, Massardier C, Gimbert Y, Greene AE. Org. Lett. 2002;4:3139. doi: 10.1021/ol026454d.Dankwardt JW. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:3753.Mohri S, Stefinovic M, Snieckus V. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:7072. doi: 10.1021/jo971123d.Lampe JW, Hughes PF, Biggers CK, Smith SH, Hu H. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:5147. doi: 10.1021/jo952280k.Ding F, Zhang Y, Qu B, Li G, Farina V, Lu BZ, Senanayake CH. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1067. doi: 10.1021/ol7029905.

- 7.(a) Singh KJ, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13753. doi: 10.1021/ja064655x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ma Y, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14818. doi: 10.1021/ja074554e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Kauch M, Hoppe D. Can. J. Chem. 2001;79:1736. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kauch M, Snieckus V, Hoppe D. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:7149. doi: 10.1021/jo0506938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collum DB. Acc. Chem. Res. 1992;25:448. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Bernstein MP, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:8008. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sun X, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2452. [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhao P, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:14411. doi: 10.1021/ja030168v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collum DB, McNeil AJ, Ramirez A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:3002. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.For leading references and discussions of mixed aggregation effects, see:Seebach D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1988;27:1624.Tchoubar B, Loupy A. Salt Effects in Organic and Organometallic Chemistry. VCH; New York: 1992. Chapters 4, 5, and 7.Briggs TF, Winemiller MD, Xiang B, Collum DB. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:6291. doi: 10.1021/jo010305b.Caubere P. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:2317.Gossage RA, Jastrzebski JTBH, van Koten G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:1448. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462103.Seebach D. Proceedings of the Robert A. Welch Foundation Conferences on Chemistry and Biochemistry; Wiley: New York. 1984.p. 93.

- 13.The exchange of free and bound TMEDA on a TMEDA-chelated lithium amide monomer appears to proceed by dimer-based mechanism:Lucht BL, Bernstein MP, Remenar JF, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:10707.

- 14.The rate law provides the stoichiometry of the transition structure relative to that of the reactants:Edwards JO, Greene EF, Ross J. J. Chem. Educ. 1968;45:381.

- 15.Kim Y-J, Bernstein MP, Galiano-Roth AS, Romesberg FE, Fuller DJ, Harrison AT, Collum DB, Williard PG. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:4435. [Google Scholar]

- 16.The spins of 6Li, 13C, and 15N are 1, 1/2, and 1/2, respectively.

- 17.(a) Collum DB. Acc. Chem. Res. 1993;26:227. [Google Scholar]; (b) Remenar JF, Lucht BL, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:5567. [Google Scholar]; (c) Bernstein MP, Romesberg FE, Fuller DJ, Harrison AT, Williard PG, Liu QY, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:5100. [Google Scholar]; (d) Romesberg FE, Gilchrist JH, Harrison AT, Fuller DJ, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:5751. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Lustig E, Benson WR, Duy N. J. Org. Chem. 1967;32:851. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamagami C, Takao N, Nishioka T, Fujita T, Takeuchi Y. Org. Magn. Reson. 1984;22:439. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rutherford JL, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:10198. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiang B, Winemiller MD, Briggs TF, Fuller DJ, Collum DB. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2001;39:137. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh KJ, Hoepker AC, Collum DB. Cornell University; Ithaca, N.Y.: Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- 22.For a discussion and leading references to the use of mixed aggregation to provide insight into homoaggregation, see ref 47b.

- 23.(a) Ramirez A, Candler J, Bashore CG, Wirtz MC, Coe JW, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:14700. doi: 10.1021/ja044899m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Riggs JC, Ramirez A, Cremeens ME, Bashore CG, Candler J, Wirtz MC, Coe JW, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:3406. doi: 10.1021/ja0754655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Stratakis M, Wang PG, Streitwieser A. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:3145. doi: 10.1021/jo9516401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Reich HJ, Green DP, Medina MA, Goldenberg WS, Gudmundsson BÖ, Dykstra RR, Phillips NH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:7201. [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Crittendon RC, Beck BC, Su J, Li XW, Robinson GH. Organometallics. 1999;18:156. [Google Scholar]; (b) Olmstead MM, Power PP. J. Organomet. Chem. 1999;408:1. [Google Scholar]; (c) Girolami GS, Riehl ME, Suslick KS, Wilson SR. Organometallics. 1992;11:3907. [Google Scholar]; (d) Bosold F, Zulauf P, Marsch M, Harms K, Lohrenz J, Boche G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1991;30:1455. [Google Scholar]; (e) Hardman NJ, Twamley B, Stender M, Baldwin R, Hino S, Schiemenz B, Kauzlarich SM, Power PP. J. Organomet. Chem. 2002;643:461. [Google Scholar]; (f) Wegner GL, Berger RJF, Schier A, Schmidbaur H. Z. Naturforsch., B: Chem. Sci. 2000;55:995. [Google Scholar]; (g) Schiemenz B, Power PP. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1996;35:2150. [Google Scholar]; (h) Maetzke T, Seebach D. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1989;72:624. [Google Scholar]; (i) Kottke T, Sung K, Lagow RJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1995;34:1517. [Google Scholar]

- 25.For representative computational studies of aryllithiums, see:Krasovsky A, Straub BF, Knochel P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2006;45:159. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502220.Bachrach SM, Chamberlin AC. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:2111. doi: 10.1021/jo035265l.Kwon O, Sevin F, McKee ML. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2001;105:913.Wiberg KB, Sklenak S, Bailey WF. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:2014. doi: 10.1021/jo991511a.Kremer T, Junge M, Schleyer P. v. R. Organometallics. 1996;15:3345.(f) Also, see ref 23b.

- 26.Menzel K, Fisher EL, DiMichele L, Frantz DE, Nelson TD, Kress MH. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:2188. doi: 10.1021/jo052515k.(b) 2JC-F values have been correlated with ·-bond orders and total electronic charge at the 13C atom:Doddrell D, Barfield M, Adcock W, Aurangzeb M, Jordan D. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2. 1976:402.

- 27.The homoaggregated phenolates tend to be insoluble, and their often-complex structures in solution are unknown. Structurally analogous lithium phenolates bearing carbonyl-containing moieties in the ortho position have been characterized crystallographically:Wang Z, Chai Z, Li Y. J. Organomet. Chem. 2005;690:4252.Boyle TJ, Pedrotty DM, Alam TM, Vick SC, Rodriguez MA. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:5133. doi: 10.1021/ic000432a.Clegg W, Lamb E, Liddle ST, Snaith R, Wheatley AEH. J. Organomet. Chem. 1999;573:305.Cetinkaya B, Gumrukcu I, Lappert MF, Atwood JL, Shakir R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:2086.Khanjin NA, Menger FM. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:8923.

- 28.(a) Hsieh HL, Quirk RP. Anionic Polymerization: Principles and Practical Applications. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wardell JL. In: Comprehensive Organometallic Chemistry. Wilkinson G, Stone FGA, Abel EW, editors. Vol. 1. Pergamon; New York: 1982. Chapter 2. [Google Scholar]; (c) Szwarc M, editor. Ions and Ion Pairs in Organic Reactions. I-II. Wiley; New York: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Espenson JH. Chemical Kinetics and Reaction Mechanisms. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rein AJ, Donahue SM, Pavlosky MA. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Dev. 2000;3:734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The concentration of the LDA, although expressed in units of molarity, refers to the concentration of the monomer unit (normality). The concentrations of solvent are expressed as total concentration of free (uncoordinated) form.

- 32.Briggs TF, Winemiller MD, Collum DB, Parsons RL, Jr., Davulcu AK, Harris GD, Fortunak JD, Confalone PN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5427. doi: 10.1021/ja0305813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian 03; revision B.04. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford, CT: 2004. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dennington R, II, Keith T, Millam J, Eppinnett K, Hovell WL, Gilliland R. GaussView, Version 3.09. Semichem, Inc.; Shawnee Mission, KS: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.We define the idealized rate law as that obtained by rounding the observed reaction orders to the nearest rational order.

- 35.Romesberg FE, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:9198. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reich HJ, Kulicke KJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:6621.Reich HJ, Green DP, Medina MA, Goldenberg WJ, Gudmundsson BÖ, Dykstra RR, Philips NH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:7201.Reich HJ, Sikorski WH, Gudmundsson BÖ, Dykstra RR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:4035.Reich HJ, Holladay JA, Mason JD, Sikorski WH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:12137.Reich HJ, Borst JP, Dykstra RR, Green DP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:8728.Jantzi KL, Puckett CL, Guzei IA, Reich HJ. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:7520. doi: 10.1021/jo050592+.and references cited therein.

- 37.See ref 10c and references cited therein.

- 38.(a) Ramirez A, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:11114. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ramirez A, Lobkovsky E, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:15376. doi: 10.1021/ja030322d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Remenar JF, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:5573. [Google Scholar]

- 39(a).We found that TMCDA prepared from commercially available R,R- and S,S-1,2-cyclohexanediamines did not afford equivalent rates of rearrangement. Although the source of the differences was not found, we alleviated the problem by resolving trans-cyclohexanediamine,39b N-methylating the methyls,17b and re-crystallizing the resulting TMCDA as its HCl salt.17b We found that the optical purity of trans-1,2-cyclohexanediamine and TMCDA could be evaluated by 13C NMR spectroscopy by adding two equiv of (+)-taddol in toluene-d8.39cLarrow JF, Jacobsen EN. Org. Synth. 1998;10:96.Seebach D, Beck AK, Heckel A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:92.

- 40.(a) Lucht BL, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:2217. [Google Scholar]; (b) Settle FA, Haggerty M, Eastham JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964;86:2076. [Google Scholar]; (c) Lewis HL, Brown TL. J.Am.Chem.Soc. 1970;92:4664. [Google Scholar]; (d) Brown TL, Gerteis RL, Rafus DA, Ladd JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964;86:2135. [Google Scholar]; (e) Quirk RP, Kester DE. J. Organomet. Chem. 1977;127:111. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lucht BL, Collum DB. Acc. Chem. Res. 1999;32:1035. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun X, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2459.Also, see ref 9.

- 43.Lucht BL, Bernstein MP, Remenar JF, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:10707. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bauer W, Klusener PAA, Harder S, Kanters JA, Duisenberg AJM, Brandsma L, Schleyer P. v. R. Organometallics. 1988;7:552.Köster H, Thoennes D, Weiss E. J. Organomet. Chem. 1978;160:1.Tecle’ B, Ilsley WH, Oliver JP. Organometallics. 1982;1:875.Harder S, Boersma J, Brandsma L, Kanters JA. J. Organomet. Chem. 1988;339:7.Sekiguchi A, Tanaka M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:12684. doi: 10.1021/ja030476t.Linnert M, Bruhn C, Ruffer T, Schmidt H, Steinborn D. Organometallics. 2004;23:3668.Fraenkel G, Stier M. Prepr. Am. Chem. Soc., Div. Pet. Chem. 1985;30:586.Ball SC, Cragg-Hine I, Davidson MG, Davies RP, Lopez-Solera MI, Raithby PR, Reed D, Snaith R, Vogl EM. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1995:2147.Wehman E, Jastrzebski JTBH, Ernsting J-M, Grove JM, van Koten GJ. Organomet. Chem. 1988;353:145.Becker J, Grimme S, Fröhlich R, Hoppe D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:1645. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603347.(k) Also, see ref 17c.

- 45.(a) Gribble GW. Science of Synthesis. 8.1.14. Georg Thieme Verlag; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]; (b) Clayden J. Organolithiums: Selectivity for Synthesis. Pergamon; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]; (c) Schlosser M. In: Organometallics in Synthesis: A Manual. 2nd ed. Schlosser M, editor. John Wiley; Chichester: 2002. Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]; (d) Clayden J. In: The Chemistry of Organolithium Compounds. Rappoport Z, Marek I, editors. Vol. 1. Wiley; New York: 2004. p. 495. [Google Scholar]

- 46.For reviews of hemilabile ligands, see:Braunstein P, Naud F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2001;40:680. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010216)40:4<680::aid-anie6800>3.0.co;2-0.Slone CS, Weinberger DA, Mirkin CA. Progr. Inorg. Chem. 1999;48:233.Lindner E, Pautz S, Haustein M. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1996;155:145.Bader A, Lindner E. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1991;108:27.

- 47.(a) Ramirez A, Sun X, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:10326. doi: 10.1021/ja062147h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liou LR, McNeil AJ, Ramirez A, Toombes GES, Gruver JM, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:4859. doi: 10.1021/ja7100642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.(a) Rennels RA, Maliakal A, Collum DB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:421. [Google Scholar]; (b) Freund M, Michaels H. Ber. 1897;30:1374. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kofron WG, Baclawski LM. J. Org. Chem. 1976;41:1879. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.