Abstract

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) causes growth arrest in epithelial cells and proliferation and morphological transformation in fibroblasts. Despite the ability of TGF-β to induce various cellular phenotypes, few discernible differences in TGF-β signaling between cell types have been reported, with the only well-characterized pathway (the Smad cascade) seemingly under identical control. We determined that TGF-β receptor signaling activates the STE20 homolog PAK2 in mammalian cells. PAK2 activation occurs in fibroblast but not epithelial cell cultures and is independent of Smad2 and/or Smad3. Furthermore, we show that TGF-β-stimulated PAK2 activity is regulated by Rac1 and Cdc42 and dominant negative PAK2 or morpholino antisense oligonucleotides to PAK2 prevent the morphological alteration observed following TGF-β addition. Thus, PAK2 represents a novel Smad-independent pathway that differentiates TGF-β signaling in fibroblast (growth-stimulated) and epithelial cell (growth-inhibited) cultures.

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) mediates a variety of signaling responses, depending on the cell context (6, 48). For example, TGF-β stimulates apoptosis in hepatocytes and lymphocytes (11), whereas vascular smooth muscle cells become resistant to apoptosis (8). Similarly, epithelial cells undergo a reversible late-G1 growth arrest following TGF-β addition (24) while fibroblasts proliferate and take on a morphologically transformed phenotype with characteristics similar to those of myofibroblasts (5, 43).

With such a wide variety of responses, it is not surprising that TGF-β receptor (TGF-βR) activation and signaling are uniquely regulated (29). There are three primary receptors for TGF-β on most cell types; they are referred to as the type I, II, and III (β-glycan) receptors. In the current model of receptor activation, ligand initially binds the type II receptor, which is a constitutively active serine/threonine kinase. This promotes the recruitment and subsequent transphosphorylation of the type I receptor in the juxtamembrane GS domain. The activated type I receptor now serves as a docking site for receptor-associated Smad (R-Smad) proteins that are brought to the receptor complex associated with the FYVE domain protein SARA (Smad anchor for receptor activation). Following phosphorylation at a specific SSxS site in the C terminus by the type I receptor, the R-Smad protein dissociates from the type I receptor, complexes with the common mediator Smad4, and translocates to the nucleus, where it can function as a comodulator of transcription (45). Recent evidence indicates that activation of R-Smad protein Smad2 or Smad3 occurs in an endosomal compartment downstream of dynamin 2ab action (20, 31).

Although the Smad pathway has been shown to be critical for many aspects of TGF-β signaling, Smad-independent responses have also been documented (16, 22, 48). While this indicates the possibility of various synergistic and/or antagonistic interactions, none of the known pathways have been capable of differentiating TGF-β signaling in cell types with distinct biologies. For instance, similar Smad-dependent and -independent signaling is observed in both epithelial and mesenchymal cultures. Since these two cell types show distinct biological responses to TGF-β, it seems likely that additional Smad-independent pathways exist that are modulated by TGF-β in a cell-type-specific manner. To address that general question, we investigated targets shown to regulate phenotypes uniquely stimulated by TGF-β in different cell lineages. As morphological alterations were some of the original responses observed in mesenchymal cells following TGF-β identification (44), we determined whether known cytoskeletal regulators would (i) respond to TGF-βR signaling and (ii) distinguish TGF-β responses in fibroblasts versus epithelial cells. To that end, the present report documents that the yeast STE20 gene homologue PAK2 (12) is activated by TGF-β independently of Smad2 or Smad3 in a cell-type-specific manner.

The p21-activated kinases (PAKs) were first identified as effectors of the Rho GTPases (26). There are currently six human PAK proteins, which fall into two subfamilies (25). The first subfamily (group I) consists of PAK1 (α-PAK), PAK2 (γ-PAK, PAKθ, hPAK65), and PAK3 (β-PAK), while the second subfamily (group II) contains PAK4, PAK5, and PAK6. The kinase domains within a subfamily show a high degree of sequence identity, and all PAK proteins bind GTP-bound Rho family members at the amino-terminal p21-binding domain (PBD). While GTP-Cdc42 or -Rac binding does not stimulate group II PAK kinase activity, it is believed that GTPase binding to the PBD results in a conformational shift whereby the binding of the regulatory N terminus with the C-terminal kinase domain is disrupted, leading to activation of the group I PAKs (25, 27). An additional mechanism through which PAK activity is both positively and negatively regulated is the binding of a family of PAK-interacting proteins called Cool (cloned out of library) or Pix (PAK-interactive exchange factor) (3, 28).

In mammalian cells, group I PAK have been implicated as regulators of actin reorganization (25, 26), cell motility (15), apoptosis (40, 42), gene transcription (47), and oncogenesis (9, 34). While PAK1 is activated following ligand addition to a number of tyrosine kinase receptors (21, 39), PAK2 activation primarily occurs in response to a variety of stresses, such as exposure to ionizing radiation, hyperosmotic shock, and serum starvation (37). Much less is known about activation of the group II PAKs; however, group II PAKs similarly modulate actin organization and it has recently been shown that PAK4 is activated via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in hepatocyte growth factor-stimulated epithelial cells (46). It is unclear how different stimuli differentially activate various PAK isoforms.

The present study shows that (i) the mammalian homolog of the STE20 gene, PAK2 (not PAK1 or PAK3), is activated in an Smad2- and Smad3-independent manner by TGF-β; (ii) TGF-β stimulation of PAK2 activity is only observed in fibroblast cells, no response is seen in a variety of epithelial cell lines although PAK2 protein is equally present; (iii) PAK2 activation is dependent on Cdc42 and Rac1, but not Rac2 or RhoA; and (iv) TGF-β-induced morphological transformation and fibroblast proliferation are inhibited by dominant negative and/or antisense PAK2. Thus, PAK2 activation represents a new cell-type-specific target of TGF-β signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Mammalian cells were grown in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DME) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biosource International) while human prostate epithelial cells (provided by Robert Abraham, The Burnham Institute) were grown in PrEGM (Clonetics) supplemented with 5% FBS. Wild-type and dominant negative tetracycline-on PAK2-expressing AKR-2B clones were generated by Fugene (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) transfection. Prior to use, clones were grown for 48 h in the presence of 10 μg of tetracycline per ml and sterilely sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting to select the highest 1% of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-expressing (EGFP-PAK2) cells.

Western blotting.

Fibroblast lines with a targeted deletion of Smad2 or Smad3 were obtained from Anita Roberts. Cultures treated overnight in serum-free DME were stimulated for the indicated times in the presence or absence of 10 ng of TGF-β per ml. Cells were lysed (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1× Complete protease inhibitor), and equivalent protein was probed with a phosphospecific Smad2 antibody, stripped, and tested for total Smad protein. The phospho-Smad2 and total Smad2 antibodies were from Upstate Biotechnology (no. 06-829) and Transduction Labs (no. 618042), respectively, while the total Smad3 antibody was from Zymed Laboratories (no. 51-1500). A rabbit anti-phospho-Smad3 antibody to the peptide COOH-GSPSIRCSpSVpS was generated in our laboratory. This antibody shows little cross-reactivity with phospho-Smad2 (see Fig. 3; data not shown). Other antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (anti-PAK1, sc-882; anti-PAK2, sc-7117; anti-PAK3, sc-1871; anti-Cdc42, sc-87; anti-Rac1, sc-95; anti-Rac2, sc-96; anti-TGF-βRI, sc-398; anti-TGF-βRII, sc-220) or Roche (anti-GFP, no. 1814460).

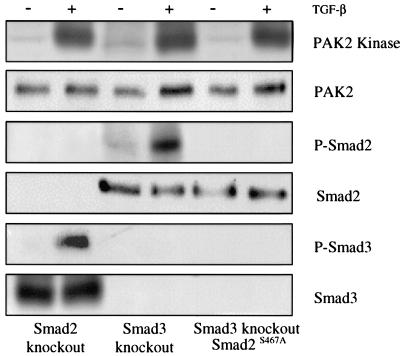

FIG. 3.

PAK2 activation is independent of Smad proteins. Fibroblast cell lines with a deletion of the gene for Smad2 (Smad2 knockout, vertical columns 1 and 2) or Smad3 (Smad3 knockout, vertical columns 3 and 4) were grown to confluence, serum starved overnight, and either left untreated (−) or stimulated (+) for 45 min with 10 ng of TGF-β per ml. Samples were lysed, normalized for equal protein, split into six aliquots, and tested for PAK2 activation (PAK2 kinase), phospho-Smad2 (P-Smad2), phospho-Smad3 (P-Smad3), or the corresponding total protein. As there is potential cellular redundancy between Smad2 and Smad3, a dominant negative Smad2-GFP construct (Smad2S467A) was transiently transfected into the Smad3 knockout cell line and GFP-positive cells were sorted by flow cytometry (data not shown). Cultures (vertical columns 5 an 6) were left untreated (−) or stimulated (+) with 10 ng of TGF-β per ml for 45 min and processed as described for the other panels.

PAK2 kinase assays.

For kinase assays and Western blotting, cells were grown to confluence in 10% DME and serum starved overnight. Cultures were treated as indicated and lysed for 30 min at 4°C in 750 μl of kinase lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 5 mM EDTA, 250 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 50 mM NaF, 0.1 trypsin inhibitor unit of aprotinin per ml, 50 μg of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride per ml, 100 μM sodium vanadate, 1 μg of leupeptin per ml). Extracts were clarified, and equivalent protein (500 to 700 μg) was incubated overnight at 4°C with antibody. Immune complexes were collected with protein A-Sepharose (Sigma) and washed twice in kinase lysis buffer and twice in kinase buffer (25 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol) prior to incubation in 50 μl of kinase buffer containing 5 μM ATP, 5 μg of myelin basic protein (Sigma), and 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP per μl. The kinase reaction was allowed to proceed for 10 min at 37°C, stopped with 50 μl of 2× Laemmli buffer, submitted to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and visualized by autoradiography.

Morphological transformation.

AKR-2B cells were plated at 2.5 × 105 per six-well dish and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Confluent cultures were placed in serum-free MCDB 402 for 48 h and stimulated by the addition of fresh serum-free DME alone or containing 10 ng of TGF-β per ml. The top 1% of EGFP-PAK2- or EGFP-PAK2K278R-expressing cells were plated at 2.5 × 105 per six-well dish and grown for 24 h in DME supplemented with 10% tetracycline-free FBS and 50 μg of hygromycin B per ml. The medium was changed to include 10 μg of tetracycline per ml, and cells were allowed to grow for an additional 24 h to confluence. Cultures were placed in serum-free DME containing 10 μg of tetracycline per ml (24 h) before addition of 10 ng of TGF-β per ml and incubation for a further 48 h. Documentation was by phase-contrast microscopy (magnification, ×20).

To investigate the effect of antisense PAK2, morpholino antisense oligonucleotides representing nucleotides −1 to +24 of mouse PAK2 (5′ TTCTAGCTCTCCGTTATCAGACATG) or the invert control (5′ GTACAGACTATTGCCTCTCGATCTT) were synthesized with 3′ fluorescein by Gene Tools. AKR-2B cells were plated in six-well dishes at a density of 8.0 × 104 per well in 10% DME and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Confluent cells were transfected with the PAK2 antisense or PAK2 invert control oligonucleotide at a final concentration of 6 μM with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Following 48 h of incubation in 2% DME and 24 h of incubation in 0.1% DME, cultures were stimulated for 48 h at 37°C in 2 ml of serum-free DME alone or containing 5 ng of TGF-β per ml prior to imaging. Transfected cells were detected by immunofluorescence.

Adenovirus constructs.

Dominant negative PAK2-expressing adenovirus was generated by transfection of adenovirus shuttle vector pAdCMV into 293Cre cells plated 24 h earlier at 9 × 105 per six-well dish. Recombinant clones were determined by induction of cytopathic effects in the monolayers, isolated, and plaque purified in 293Cre cells. Cell-free viral supernatants were prepared, and titers were determined in 293 cells. Control GFP-expressing adenovirus was purchased from Riken GenBank (Japan).

RESULTS

Activation of PAK2 distinguishes TGF-β signaling in fibroblast and epithelial cells.

While TGF-β modulates (is causal to) a number of biological phenotypes (6), the manner in which the TGF-β signal(s) is transduced following receptor binding is relatively unknown. While both Smad-dependent and -independent pathways have been shown to be critical for many aspects of TGF-β action, none of the currently identified pathways can differentiate TGF-β signaling in cell types with distinct biologies. Since TGF-β induces significant morphological changes and PAK family members are known regulators of the actin cytoskeleton, we determined whether PAK proteins were activated by TGF-β. AKR-2B fibroblasts were stimulated with TGF-β for 5 to 120 min, and lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies to PAK1, PAK2, or PAK3. As shown in Fig. 1A, TGF-β stimulated the kinase activity of PAK2 within 5 to 15 min of ligand addition and no effect on PAK1 or PAK3 activation was observed.

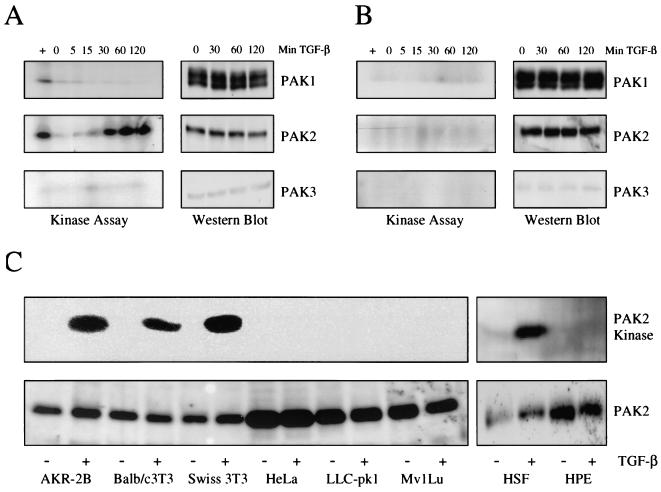

FIG. 1.

TGF-β activates PAK2 in fibroblast but not epithelial cells. (A, left half) AKR-2B fibroblasts were grown to confluence, serum starved for 24 h, and stimulated with 10 ng of TGF-β per ml for the indicated times. Stimulation with platelet-derived growth factor (25 ng/ml) for 20 min was used as a positive control for PAK1 and PAK2 in fibroblasts (+). Following immunoprecipitation, the in vitro kinase activity of the various PAK proteins was examined with myelin basic protein. (A, right half) Prior to immunoprecipitation and kinase assay, 100 μg of protein was used for Western analysis against the various PAK proteins. (B) The same protocols as described for panel A were used with Mv1Lu epithelial cells. The results shown are representative of three separate experiments. (C) Fibroblast cell lines AKR-2B, Swiss 3T3, and BALB/c 3T3, along with epithelial cell lines Mv1Lu, HeLa, and LLC-pk1, were grown to confluence, serum starved overnight, and either left untreated (−) or stimulated (+) with 10 ng of TGF-β per ml for 45 min at 37°C. Samples were normalized for total protein (within a cell type) and assayed for kinase activity (top) or Western blotted for total PAK2 (bottom). The same protocols were used for human skin fibroblasts (HSF) and human prostate epithelial cells (HPE).

As PAK2 activation represents a novel target of TGF-β signaling, we next addressed two general questions: first, does TGF-β similarly stimulate PAK2 activity in Mv1Lu cells which are growth inhibited by TGF-β, and second, would the PAK2 response observed in AKR-2B and Mv1Lu cells be representative of a more generalized distinction for mesenchymal and epithelial cultures, respectively? While Fig. 1A demonstrates isoform-specific PAK activation by TGF-β in AKR-2B cells, when we examined the response in Mv1Lu epithelial cells, none of the group I PAK isoforms were activated although the PAK1 and PAK2 proteins were equally expressed (Fig. 1B). The low-level expression or lack of expression of PAK3 in AKR-2B and Mv1Lu cells was expected because of the primary brain tropism of PAK3 (25). Having found a possible fibroblast-epithelial-cell difference in response to TGF-β, we wanted to exclude the possibility that our observation was unique to AKR-2B or Mv1Lu cells. To address this issue, we stimulated three representative fibroblast (AKR-2B, Swiss 3T3, and BALB/c 3T3) and epithelial (Mv1Lu, HeLa, and LLC-pk1) cell lines with TGF-β for 45 min and examined the induction of PAK2 kinase activity. In agreement with the results shown in Fig. 1A and B, PAK2 activation by TGF-β only occurred in the fibroblast cultures, with no significant difference in the level of PAK2 protein expressed across the cell types (Fig. 1C). Similar results were observed when primary human skin fibroblasts and nontransformed (but immortalized) human prostate epithelial cells were examined (Fig. 1C). Thus, PAK2 activation by TGF-β represents (i) an example of PAK isoform-specific cytokine stimulation, (ii) the identification of a new target downstream of the TGF-βR complex, and (iii) a kinase activity that differentiates TGF-β signaling in a subset of murine and human fibroblast and epithelial cell lines (Fig. 1).

PAK2 activation requires TGF-βR kinase activity and is downstream of the TGF-βR complex.

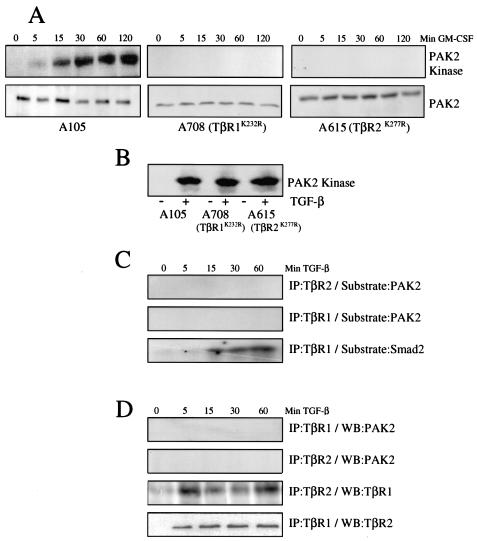

TGF-β action is mediated through a complex interaction of type I and II receptors. Fundamental to this response is a requirement for both type I and II TGF-βR kinase activities. Since TGF-β stimulation of the PAK2 kinase represents a new cell-type-specific signaling target, we addressed two essential issues. First, what is the role of receptor kinase activity in PAK2 activation, and second, is PAK2 a substrate or binding partner for the TGF-βR complex? To determine the requirement for TGF-βR kinase activity in PAK2 activation, we took advantage of the chimeric TGF-βR model we developed with AKR-2B cells (2). This system uses the ligand-binding domain of the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) α and β receptors and fuses them to the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of the type I or II TGF-βR. We have previously determined that the chimeric system faithfully recapitulates native TGF-βR signaling in both substrate specificity and the requirement for type I and II receptor kinase activities (1, 14). To that end, we examined PAK2 activation in AKR-2B clones expressing (i) wild-type type I and II chimeric TGF-βRs (A105), (ii) wild-type type II and kinase-impaired type I chimeric TGF-βRs (A708), and (iii) wild-type type I and kinase-impaired type II chimeric TGF-βRs (A615). As shown in Fig. 2A, while activation of wild-type chimeric receptors with GM-CSF induces PAK2 kinase activity with kinetics similar to those of native TGF-βRs (compare Fig. 1A and 2A), the absence of receptor kinase activity in either the type I or the type II chimeric TGF-βR prevents PAK2 activation (Fig. 2A, A708 and A615 cultures, respectively). This does not reflect a general signaling anergy in the A615 or A708 clones, since stimulation of the native TGF-βRs with TGF-β resulted in increased PAK2 kinase activity (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

PAK2 activation occurs downstream of the TGF-βR complex. (A and B) Requirement for TGF-βR kinase activity. Stable cell lines expressing either wild-type (A105) or kinase-deficient (A708, TβR1K232R; A615, TβR2K277R) chimeric TGF-βRs were processed for kinase activity and/or PAK2 expression following stimulation with 10 ng of GM-CSF per ml for the indicated times (A) or TGF-β for 45 min (+, B) (1). (C) PAK2 is not a substrate for the TGF-βR complex. AKR-2B cells were grown to confluence and serum starved for 24 h prior to cell lysis and immunoprecipitation (IP) with antibodies to the type I (TβR1) or II (TβR2) TGF-βR after stimulation with TGF-β (10 ng/ml) for the indicated times. Purified PAK2 (top and middle) and Smad2 (bottom) were used as in vitro kinase substrates as previously described (31). (D) PAK2 does not bind the TGF-βR complex. AKR-2B cells were grown to confluence, serum starved for 24 h, and stimulated with 10 ng of TGF-β per ml for 5 to 60 min. Cultures were lysed and immunoprecipitated with the indicated TGF-βR antibody, and associated PAK2, TβR1, or TβR2 was determined by Western blot (WB) analysis.

A number of proteins have been shown to bind and/or be serine/threonine phosphorylated by the TGF-βR complex (23, 45). Since PAK2 is extensively phosphorylated on serine and threonine residues and phosphorylation of T402 is believed to be critical to PAK2 activation (37), we next determined if PAK2 is directly phosphorylated by the ligand-activated type I or II TGF-βR. AKR-2B cells were stimulated with TGF-β, and following immunoprecipitation with antibodies to the type I or II receptor, an in vitro kinase reaction was performed with either PAK2 or Smad2 as the substrate (Fig. 2C). Although no detectable phosphorylation of PAK2 was observed, as expected, Smad2 was readily phosphorylated by the ligand-activated type I receptor. While these results indicate that PAK2 is not directly phosphorylated by the TGF-βR complex, it is still possible that TGF-βRs and PAK2 associate in a multiprotein complex. However, as shown in Fig. 2D, we were unable to observe any interaction between PAK2 and the TGF-βRs under conditions in which ligand-dependent association of the type I and II receptors is apparent. Thus, PAK2 does not appear to be either a substrate or a binding partner for the type I or II TGF-βR.

PAK2 activation and Smad phosphorylation occur independently.

TGF-β signaling is primarily mediated through the Smad family of transcriptional coregulators, although Smad-independent signaling has been reported. As PAK2 represents a novel TGF-β-modulated kinase uniquely controlled in fibroblasts versus epithelial cells, we next determined the role(s) of Smad2 and/or Smad3 in PAK2 activation. Fibroblast cell lines from Smad2 or Smad3 knockout mice were stimulated with TGF-β, and PAK2 kinase activity was measured. There was no appreciable effect on TGF-β-stimulated PAK2 activity when either the Smad2 or Smad3 gene was knocked out (Fig. 3, first four columns). Although defined activities for Smad2 and -3 have been reported (32), it is possible that potential redundancy exists such that the loss of one is compensated for by the other. To address this issue, we transfected a dominant negative GFP-Smad2 construct (33) into the Smad3 knockout cell line and sorted for GFP-positive cells. While phosphorylation of both Smad2 and Smad3 was abolished, there was no effect on TGF-β-stimulated PAK2 activity (Fig. 3, far right two columns).

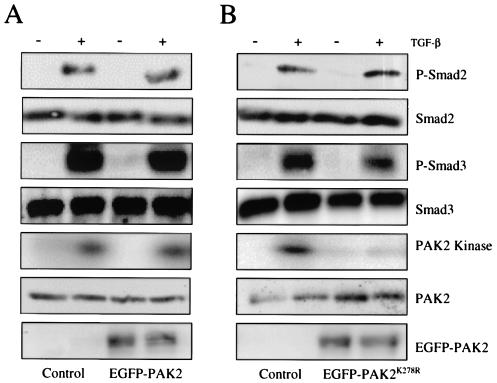

Although Fig. 3 demonstrates that Smad2 and/or Smad3 phosphorylation is not required for PAK2 activation, it does not address the converse (i.e., whether PAK2 activation is required for Smad2 or Smad3 phosphorylation). Accordingly, AKR-2B cells were transfected with GFP-tagged wild-type or dominant negative PAK2, GFP-positive cells were selected by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis, and the level of phosphorylated Smad2 and Smad3 was determined following addition of TGF-β (Fig. 4). Expression of wild-type (Fig. 4A, columns 3 and 4) or dominant negative (Fig. 4B, columns 3 and 4) PAK2 had no effect on TGF-β-stimulated R-Smad phosphorylation. The preceding data (Fig. 1 to 4) show that TGF-β stimulation of PAK2 activity is (i) differentially regulated in fibroblast and epithelial cell types, (ii) dependent on TGF-βR kinase activity, and (iii) independent of Smad2 and Smad3 phosphorylation.

FIG. 4.

Smad phosphorylation is independent of PAK2 kinase activity. (A) AKR-2B cells (Control, vertical columns 1 and 2) or stable AKR-2B clones harboring tetracycline-on regulated wild-type PAK2 (EGFP-PAK2, vertical columns 3 and 4; see Materials and Methods) were grown to confluence, serum starved overnight, and either left untreated (−) or stimulated (+) with 10 ng of TGF-β per ml for 45 min. EGFP-PAK2-expressing clones were grown in the presence of 10 μg of tetracycline per ml. Cells were lysed and assayed for the indicated total or activated proteins as described in the legend to Fig. 3. (B) Studies similar to those in panel A were performed with AKR-2B cells (Control, vertical columns 1 and 2) or stable AKR-2B clones harboring tetracycline-on regulated dominant negative PAK2 (EGFP-PAK2K278R, vertical columns 3 and 4).

TGF-β-stimulated PAK2 activity is regulated by Rho family GTPases.

All of the currently known PAK kinases bind activated Rho proteins through a binding motif at the amino terminus (25, 37). This activates the kinase activity of group I (not group II) PAKs because of a loss of an autoinhibitory interaction between the amino regulatory domain with the COOH-terminal catalytic region. In order to determine which (if any) Rho family member was activated by TGF-β to bind PAK2, PAK2 was immunoprecipitated from cultures following TGF-β treatment and Western blotted for the indicated Rho protein. Within 5 min of TGF-β addition, enhanced Cdc42 and Rac1 binding to PAK2 was observed, resulting in a four- to fivefold increase by 30 min (Fig. 5A, left vertical column). No appreciable change in Rac2/PAK2 association was detected (data not shown), nor was binding of Rac1 or Cdc42 to PAK2 observed in Mv1Lu epithelial cells treated with TGF-β (Fig. 5A, left vertical column).

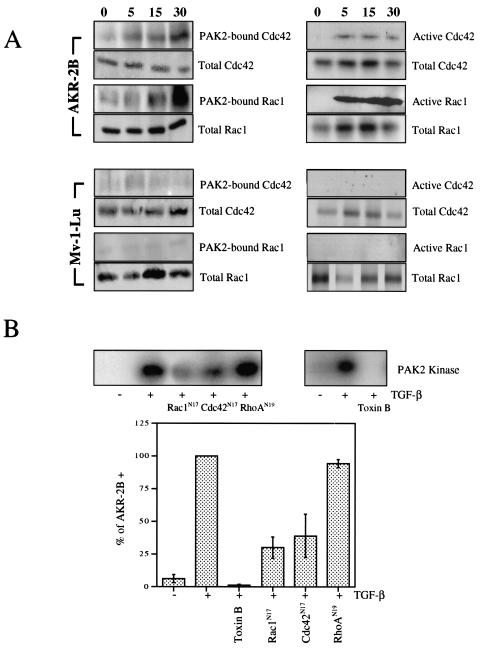

FIG. 5.

Rac1 and Cdc42, but not RhoA or Rac2, regulate PAK2 activation by TGF-β. (A) AKR-2B fibroblasts or Mv1Lu epithelial cells were grown to confluence, serum starved for 24 h, and stimulated with 10 ng of TGF-β per ml for the indicated times (in minutes). (Left half) PAK2 was immunoprecipitated (IP), and associated Cdc42 or Rac1 was determined by Western blotting. (Right half) GTP-bound Cdc42 or Rac1 was evaluated by binding to GST-PBD. Prior to immunoprecipitation, 100 μg of protein from the same lysate was analyzed for total Cdc42 or Rac1. (B, top left) AKR-2B fibroblasts were transiently transfected with either wild-type EGFP-PAK2 or both EGFP-PAK2 and dominant-negative Rac1 (Rac1N17), Cdc42 (Cdc42N17), or RhoA (RhoAN19). Cells were serum starved for 24 h and either left untreated (−) or stimulated (+) for 45 min with 10 ng of TGF-β per ml. Following immunoprecipitation with an anti-GFP antibody, the in vitro kinase activity of the transfected EGFP-PAK2 protein was determined. (B, top right) AKR-2B cultures were untreated or pretreated for 6 h with Clostridium difficile toxin B (2 ng/ml) prior to stimulation (+) with 10 ng of TGF-β per ml for 45 min. PAK2 kinase activity was assessed as described in Materials and Methods. (B, bottom) TGF-β-stimulated PAK2 kinase activity was quantified following disruption of the indicated Rho pathways and normalized to that of control AKR-2B cells treated with 10 ng of TGF-β per ml as in panel B (top two parts). For the dominant negative Rho mutants, the values represent the remaining transfected EGFP-PAK2 kinase activity while the effect of toxin B reflects endogenous PAK2. Results represent the mean ± the standard deviation of four separate experiments.

The distinct cell type association of Cdc42 and Rac1 with PAK2 (Fig. 5A, left vertical column) indicates differential Rho family member activation stimulated by TGF-β. However, the inability of Rac1 and Cdc42 to bind PAK2 in epithelial cells may reflect a binding difference, per se, and not a lack of GTP loading. To investigate this further, we also used PBD binding to assess Cdc42 and Rac1 activation (Fig. 5A, right vertical column). Similar to the binding observed with PAK2 coimmunoprecipitation, Cdc42 and Rac1 bound the PAK PBD within 5 min of TGF-β stimulation of mesenchymal AKR-2B cells. Again, no binding was observed in Mv1Lu epithelial cell lysates although Cdc42 and Rac1 were equally expressed (Fig. 5A, right vertical column).

Rho protein binding to PAK kinases only occurs in the GTP-bound (activated) state (7, 25). That activation of Cdc42 and/or Rac1 is necessary for TGF-β-stimulated PAK2 kinase activity is shown in Fig. 5B. AKR-2B cells were transfected with wild-type EGFP-PAK2 alone or with the indicated dominant negative Rho family protein. Following TGF-β stimulation, the transfected PAK2 was immunoprecipitated with GFP antibodies and kinase activity was determined. While Rac1N17 and Cdc42N17 each inhibited PAK2 kinase activity approximately 40 to 60%, dominant negative RhoA was without effect. Clostridium toxin B was used to document the total Rho dependence on PAK2 activation. Thus, TGF-β activation of PAK2 in AKR-2B cells uses Rho proteins Rac1 and Cdc42, but not RhoA or Rac2.

PAK2 activity is required for TGF-β morphological transformation and cell proliferation.

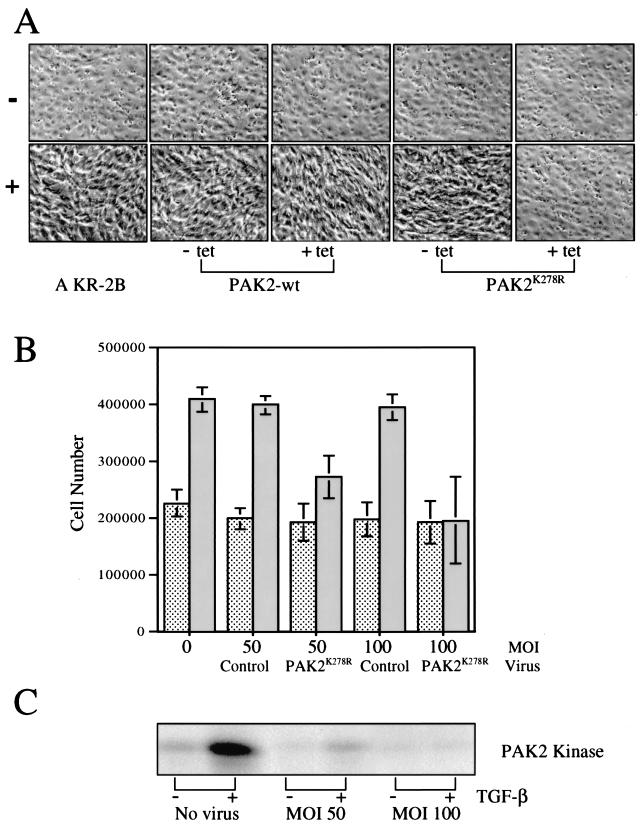

The previous data indicate that PAK2 represents a novel intermediary downstream of TGF-βR activation capable of distinguishing TGF-β signaling in fibroblast and epithelial cell types (Fig. 1 to 5). Of interest, however, was whether this new pathway could be causally linked to biological phenotypes regulated by TGF-β. As cytoskeletal alterations resulting in a morphological transformation were one of the earliest cellular findings associated with TGF-β stimulation of fibroblasts (44) and the pathways leading to PAK2 activation are known to be associated with actin rearrangement (36, 38), we examined the role of PAK2 in this response. As shown in Fig. 6A, AKR-2B cells treated with TGF-β transform from large “cobblestone-like” round cells into thin elongated cells that spread and crawl over one another, reminiscent of transformed cultures. In order to investigate the role(s) of PAK2 and/or upstream Rho GTPases in TGF-β morphological transformation, stable cell lines were generated expressing wild-type or dominant negative PAK2 with a tetracycline-on inducible promoter. While the wild-type PAK2 construct was without effect, expression of the dominant negative prevented AKR-2B cells from morphologically transforming in the presence of TGF-β (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Dominant negative PAK2 prevents TGF-β-stimulated morphological transformation and cell proliferation. (A) Parental AKR-2B cells or AKR-2B clones stably transfected with tetracycline-on wild-type (PAK2-wt) or dominant negative EGFP-PAK2 (PAK2K278R) were grown to confluence in either the absence (−tet) or the presence (+tet) of 10 μg of tetracycline per ml, serum starved for 24 h, and either left untreated (−) or stimulated (+) for 48 h with 10 ng of TGF-β per ml. Representative areas were photographed at a magnification of ×20 by phase microscopy. (B) AKR-2B cells were plated at 2.5 × 105 per six-well dish and grown overnight at 37°C. The serum-containing medium was removed and replaced with serum-free DME alone or containing the indicated multiplicity of infection (MOI) of adenovirus expressing GFP (Control) or dominant negative PAK2 (PAK2K278R). Following 24 h of incubation, TGF-β was directly added to a final concentration of 5 ng/ml (solid bars) and the cell number was determined 48 h later. Dotted bars show results after addition of the indicated virus to serum-free DME. Results represent the mean ± the standard deviation of two separate experiments done in duplicate. (C) AKR-2B cells were plated at 2 × 106 per 100-mm culture dish and cultured as described for panel B. Following 45 min of treatment with (+) or without (−) 10 ng of TGF-β per ml, cell lysates were prepared and PAK2 kinase activity was determined (Materials and Methods).

The ability of the dominant negative PAK2 enzyme to inhibit the morphological transformation indicated a direct role for proteins downstream of activated Rho proteins in TGF-β-mediated cytoskeletal reorganization. To investigate this further, we wished to discern if the cell proliferation induced by TGF-β was also sensitive to dominant negative PAK2. To that end, a dominant negative PAK2 adenovirus was constructed and its effect on TGF-β-mediated proliferation was determined. Addition of TGF-β to serum-free medium resulted in an approximate cell doubling over 48 h (Fig. 6B). While the control GFP-expressing adenovirus was without effect, infection with adenovirus expressing dominant negative PAK2 abolished TGF-β-stimulated proliferation and PAK2 kinase activity was diminished to control levels (Fig. 6B and C).

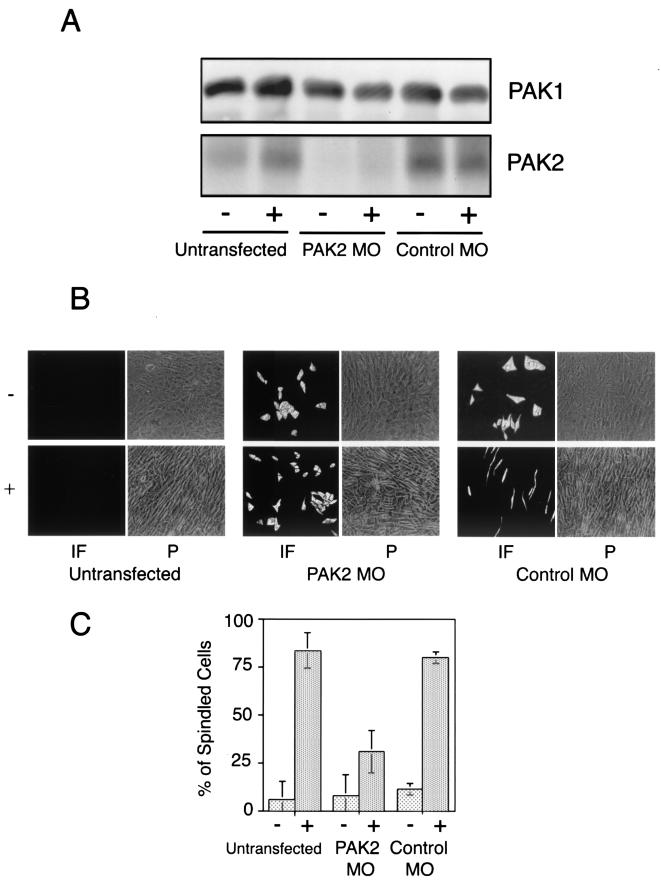

While the dominant negative PAK2 constructs used in Fig. 6 suggest that PAK2 activation is coincident with or necessary for TGF-β morphological transformation and cell growth, it is also possible that the dominant negative protein functions by (i) sequestering activated Rac1 and/or Cdc42 and not through direct inhibition of PAK2 and/or (ii) complexing with other PAK family members and inhibiting their activity. To address these issues, we transfected morpholino antisense oligonucleotides to PAK2 and assessed their effect on TGF-β-stimulated morphological transformation. As shown in Fig. 7, the antisense oligonucleotides, but not the invert control, specifically diminish PAK2 protein (no effect on PAK1 was observed) and prevent the morphological alteration associated with TGF-β treatment more than 60%.

FIG.7.

PAK2 antisense oligonucleotides inhibit TGF-β morphological transformation. (A) Cos7 cells were plated at 8.0 × 104 per six-well dish and grown for 2 days prior to transient transfection with either PAK2 antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (PAK2 MO) or invert control (Control MO). Total PAK1 and PAK2 protein was determined as described in Materials and Methods following 48 h of stimulation in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 10 ng of TGF-β per ml. (B) AKR-2B cells were treated as described for panel A. Transfected and total cell populations were visualized by immunofluorescence (IF) and phase-contrast (P) microscopy, respectively, and representative fields were photographed at an original magnification of ×20. (C) Transfected cells were scored as to whether TGF-β (+) stimulated the morphological change where the length was greater than or equal to five times the width shown in panel B. A similar analysis was performed with the untransfected cultures. The data are the mean ± the standard deviation of two separated experiments done in triplicate and represent a total of more than 1,000 cells per treatment.

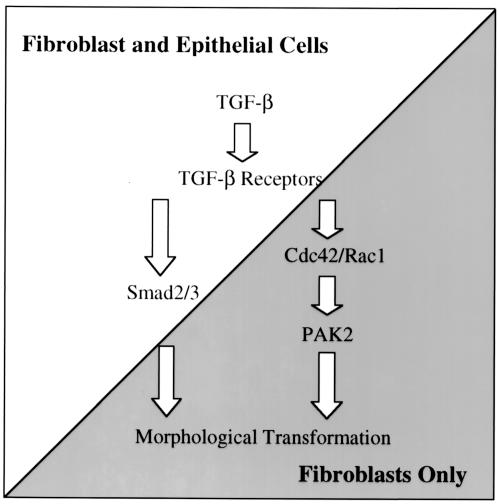

Cell-type-specific PAK2 activation by TGF-β.

On the basis of our observations, we propose a model depicting cell-type-specific activation of PAK2 (Fig. 8). TGF-βR activation results in the stimulation of both overlapping and distinct signaling pathways in fibroblasts and epithelial cells. While Smad-dependent signaling is induced in both cell types, a series of events are initiated in fibroblasts such that PAK2 is activated in a Cdc42- and Rac1-dependent manner. Although it is not known how the TGF-βR complex induces Rho protein activation and/or cross talk between the PAK- and Smad-dependent pathways, signals emanating from both are required for morphological transformation and cellular proliferation (Fig. 6 and 7) (13, 17).

FIG. 8.

Cell-type-specific PAK2 activation by TGF-β. A model depicting our present understanding of PAK2 activation by TGF-β in fibroblasts is shown. Following ligand binding to the TGF-βR complex, fibroblasts and epithelial cells differentially integrate the signal(s) such that Smad-dependent signaling is activated in both cell types while PAK2 becomes activated only in fibroblasts. Activation of PAK2 is dependent on Rho GTPases Cdc42 and Rac1. While the Smad- and PAK2-dependent pathways are believed to be distinct, both are required for fibroblast morphological transformation and cellular proliferation (Fig. 6 and 7) (13, 17). Arrows do not necessarily indicate a direct interaction and may reflect multiple events.

DISCUSSION

The pathways downstream of the activated TGF-βR complex have been difficult to define. In fact, an early publication by Chambard and Pouyssegur documented that TGF-β did not induce a number of mediators routinely stimulated by various growth factors (10). It was not until the studies by Savage et al. (41) and Raftery et al. (35) describing the Sma and Mad proteins, respectively, that a pathway emerged (i.e., the Smad pathway) that responded to TGF-β in a consistent manner. During the ensuing years, a number of laboratories have described a variety of activities and mechanisms through which the Smad pathway responds to and regulates TGF-β action (30, 45). Although Smad signaling can account for much of TGF-β's action, when one considers the plethora of activities believed to be controlled by TGF-β, it seems reasonable that additional Smad-independent pathways must exist and be operative. In that regard, recent work has demonstrated that Smad-independent signaling occurs for fibronectin synthesis and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation (16, 22, 48). However, while these findings have significantly extended our understanding of TGF-β signaling, a major limitation of all of these studies is that each of the pathways has been shown to be activated in a variety of cell types and lineages. Since TGF-β can induce cellular responses as diverse as growth inhibition versus growth stimulation, proapoptotic versus antiapoptotic responses, and stimulation of differentiation versus inhibition of differentiation, for example, depending on the cell context, a missing component of TGF-β signaling was the identification of a pathway(s) that might only be activated under one biological condition and not the converse (i.e., in cells growth stimulated but not growth inhibited). It was to that end that the present study was initiated.

TGF-β addition to fibroblastic AKR-2B cells resulted in activation of the PAK2 kinase within 5 to 15 min; no effect on either PAK1 or PAK3 (i.e., other group I PAKs) was observed (Fig. 1A), nor was PAK2 activated by TGF-β in a variety of epithelial cell lines (Fig. 1B and C). These findings were of interest for a number of reasons. First, PAK2 has not been previously considered a target of growth factor-activated receptors. In general, while PAK1 has been shown to be downstream of many tyrosine receptor kinases, PAK2 is routinely activated in response to various stress. It is not known why PAK1 is not activated or whether PAK4 to -6 can be activated by TGF-β. In that regard, the effect of TGF-β on PAK4 activity would be of interest as PAK4 (similar to TGF-β) has been reported to be involved in stimulating anchorage-independent growth (9, 34). However, PAK4 to -6 have been classified as group II PAKs and are structurally quite different from the group I PAKs (25). For instance, Rho protein binding to PAK4 does not appear to enhance kinase activity. Second, the activity of any PAK family member has not been previously shown to be regulated by TGF-β. Third, while PAK2 activation was shown to be dependent on TGF-βR kinase activity (Fig. 2A and B), PAK2 was neither a substrate nor a binding partner for the TGF-βR complex (Fig. 2C and D) and was activated in the absence of Smad2 and/or Smad3 (Fig. 3). Thus, TGF-β stimulation of PAK2 represents a new Smad-independent signaling target downstream of the activated TGF-βR complex.

It is of note that of the group I PAKs, PAK2 was specifically activated by TGF-β in fibroblasts and not epithelial cells (Fig. 1). This was observed in both normal and transformed human and murine cell types. While it is unknown if TGF-β stimulates PAK2 activation in other cell lineages (i.e., hematopoietic, endothelial, neural, etc.) or more differentiated models (i.e., bone, muscle, etc.), the finding of differential TGF-β signaling in mesenchymal and epithelial cultures provides initial insight into the distinct phenotypes induced by TGF-β in these two cell types. To that end, we have previously reported that the endocytic response of the TGF-βR complex is regulated differently in fibroblasts and epithelial cells (14, 18). Further work is required to define the most proximal events subsequent to TGF-β binding if we hope to modulate distinct components of TGF-β action.

While both group I and II PAKs bind GTP-bound Rho family proteins, the kinase activity of only the group I PAKs is enhanced (25). This was directly observed in the experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 5, in which both Rac1 and Cdc42 were shown to associate with PAK2, bind to the PAK PBD, and (each) independently regulate approximately 50% of the TGF-β-dependent increase in PAK2 kinase activity. No effect was observed with Rac2 or RhoA (data not shown and Fig. 5B, respectively). The fact that RhoA (and not Rac1 or Cdc42) has been reported to be required for an epithelial-to-mesenchymal cell transition mediated by TGF-β (4) might suggest that the transdifferentiated epithelial cell is distinct from a fibroblast, per se, and/or the initial TGF-β signal is uniquely integrated in the two cell types. Similarly, activation of PAK2 (and/or that of other PAK family member) might correspond to a unique activity stimulated by TGF-β during the epithelial-to-mesenchymal cell transition process(es). Current projects in the laboratory are addressing that issue.

PAK are involved in or causal to a number of biological processes. Chief among them is the cytoskeletal rearrangement associated with lamellipodia or filopedia and cell migration (25, 26). As TGF-β induces both PAK2 activity and actin reorganization, PAK2 activation might represent a potential biochemical pathway linking the various morphological changes under TGF-β control with TGF-βR signaling. In support of that hypothesis, the experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 6 demonstrated that expression of dominant negative PAK2 prevented TGF-β-mediated cellular proliferation and morphological transformation. However, the PAK2 dominant negatives could be having unexpected effects in that they could be inhibiting other PAK family members and/or sequestering Rac1/Cdc42 in nonfunctional complexes. To address these concerns, we used morpholino antisense oligonucleotides to PAK2 and demonstrated that (i) PAK2 protein was decreased while PAK1 protein levels were unchanged and (ii) the antisense oligonucleotides diminished the morphological alteration induced by TGF-β by more than 60% (Fig. 7). As PAK3 is not activated or expressed in AKR-2B cells (Fig. 1A) and the group II PAKs (PAK4 to -6) lack the amino-terminal region to which the antisense oligonucleotide was generated, the results indicate a direct role for PAK2 in TGF-β morphological transformation.

The morphological change induced by TGF-β generates a cellular phenotype with similarities to myofibroblasts observed in fibrogenic tissues such as induction of α smooth-muscle actin and accumulation of extracellular matrix molecules (5, 19, 43). However, PAK2 is clearly only one component in the pathways required for these alterations and a model is presented in Fig. 8 that depicts that interrelationship. For instance, while we show that PAK2 is activated independently of Smad2 and/or Smad3 (Fig. 3), Smad3 is required for fibrosis and α smooth-muscle actin expression (13, 17). In support of these results, we found that dominant negative PAK2 had no effect on the induction of α smooth-muscle actin (unpublished data), further supporting the hypothesis that PAK2 and Smad signaling are distinctly regulated (Fig. 3 and 4). Whether the pathways remain parallel, eventually converge, and/or are antagonistic to other TGF-β responses is not known. However, regardless of any integration between the PAK and Smad pathways, the present study indicates that it may become possible to specifically modulate distinct TGF-β-regulated phenotypes in defined cell types.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rolf Jakobi for the wild-type (pRevTRE-EGFP-γ-PAK) and dominant negative (pRevTRE-EGFP-γ-PAK-K278R) PAK2 plasmids, Azeddine Atfi for the dominant negative (pEGFP-SMAD2-S467A) Smad2 vector, and Jeffrey Field (pCMV5-Rac1N17 and pCMV5-Cdc42N17) and Dan Billadeau (pCMV5-RhoAN19) for dominant negative Rho constructs. Sandra Arline provided excellent technical assistance in the early stages of the project, while Jules Doré provided helpful discussions.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants GM-54200 and GM-55816 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anders, R. A., J. E. J. Doré, S. A. Arline, N. Garamszegi, and E. B. Leof. 1998. Differential requirements for type I and type II TGFβ receptor kinase activity in ligand-mediated receptor endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 273:23118-23125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anders, R. A., and E. B. Leof. 1996. Chimeric granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor/transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) receptors define a model system for investigating the role of homomeric and heteromeric receptors in TGF-β signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 271:21758-21766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagrodia, S., and R. A. Cerione. 1999. PAK to the future. Trends Cell Biol. 9:350-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhowmick, N. A., M. Ghiassi, A. Bakin, M. Aakre, C. A. Lundquist, M. E. Engel, C. L. Arteaga, and H. L. Moses. 2001. Transforming growth factor-β1 mediates epithelial to mesenchymal transdifferentiation through a RhoA-dependent mechanism. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:27-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bissell, D. M. 2001. Chronic liver injury, TGF-β, and cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 33:179-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blobe, G. C., W. P. Schiemann, and H. F. Lodish. 2000. Role of transforming growth factor beta in human disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 342:1350-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bokoch, G. M. 2000. Regulation of cell function by Rho family GTPase. Immunol. Res. 21:139-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bono, F., I. Lamarche, and J. Herbert. 1997. NGF exhibits a pro-apoptotic activity for human vascular smooth muscle cells that is inhibited by TGF-β1. FEBS Lett. 416:243-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callow, M. G., F. Clairvoyant, S. Zhu, B. Schryver, D. B. Whyte, J. R. Bischoff, B. Hallal, and T. Smeal. 2002. Requirement for PAK4 in the anchorage-independent growth of human cancer cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 277:550-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chambard, J.-C., and J. Pouyssegur. 1988. TGF-β inhibits growth factor-induced DNA synthesis in hamster fibroblasts without affecting early mitogenic events. J. Cell. Physiol. 135:101-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, R., Y. Su, R. L. C. Chuang, and T. Chang. 1998. Suppression of transforming growth factor-β-induced apoptosis through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/akt-dependent pathway. Oncogene 17:1959-1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, Y., and T. Tan. 1999. Mammalian c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway and STE20-related kinases. Gene Ther. Mol. Biol. 4:83-98. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cogan, J. G., S. V. Subramanian, J. A. Polikandriotis, R. J. Kelm, and A. R. Strauch. 2002. Vascular smooth muscle α-actin gene transcription during myofibroblast differentiation requires Sp1/3 protein binding proximal to the MCAT enhancer. J. Biol. Chem. 277:36433-36442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doré, J. J. E., Jr., M. Edens, N. Garamszegi, and E. B. Leof. 1998. Heteromeric and homomeric transforming growth factor-β receptors show distinct signaling and endocytic responses in epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273:31770-31777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edwards, D. C., L. C. Sanders, G. M. Bokoch, and G. N. Gill. 1999. Activation of LIM-kinase by PAK1 couples Rac/Cdc42 GTPase signaling to actin cytoskeletal dynamics. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:253-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engel, M. E., M. A. McDonnell, B. K. Law, and H. L. Moses. 1999. Interdependent SMAD and JNK signaling in TGF-β mediated transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 274:37413-37420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flanders, K. C., C. D. Sullivan, M. Fujii, A. Sowers, M. A. Anzano, A. Arabshahi, C. Major, C. Deng, A. Russo, J. B. Mitchell, and A. B. Roberts. 2002. Mice lacking Smad3 are protected against cutaneous injury induced by ionizing radiation. Am. J. Pathol. 160:1057-1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garamszegi, N., J. J. E. Doré, Jr., S. G. Penheiter, M. Edens, D. Yao, and E. B. Leof. 2001. Transforming growth factor β receptor signaling and endocytosis are linked through a COOH terminal activation motif in the type I receptor. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:2881-2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashimoto, S., Y. Gon, I. Takeshita, K. Matsumoto, S. Maruoka, and T. Horie. 2001. Transforming growth factor-β1 induces phenotypic modulation of human lung fibroblasts to myofibroblasts through a c-Jun-NH2-terminal kinase-dependent pathway. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 163:152-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayes, S., A. Chawla, and S. Corvera. 2002. TGFβ receptor internalization into EEA1-enriched early endosomes: role in signaling to Smad2. J. Cell Biol. 158:1239-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He, H., A. Levitzki, H.-J. Zhu, F. Walker, A. Burgess, and H. Maruta. 2001. Platelet-derived growth factor requires epidermal growth factor receptor to activate p21-activated kinase family kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 276:26741-26744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hocevar, B. A., T. L. Brown, and P. H. Howe. 1999. TGF-β induces fibronectin synthesis through a c-Jun N-terminal kinase-dependent, Smad4-independent pathway. EMBO J. 18:1345-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hocevar, B. A., A. Smine, X.-X. Xu, and P. H. Howe. 2001. The adaptor molecule disabled-2 links the transforming growth factor β receptors to the Smad pathway. EMBO J. 20:2789-2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howe, P. H., G. Draetta, and E. B. Leof. 1991. Transforming growth factor β1 inhibition of p34cdc2 phosphorylation and histone H1 kinase activity is associated with G1/S-phase growth arrest. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:1185-1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaffer, Z. M., and J. Chernoff. 2002. p21-activated kinases: three more join the Pak. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 34:713-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knaus, U. G., and G. M. Bokoch. 1998. The p21Rac-Cdc42-activated kinases (PAKs). Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 30:857-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lei, M., W. Lu, W. Meng, M. Parrini, M. J. Eck, B. J. Mayer, and S. C. Harrison. 2000. Structure of PAK1 in an autoinhibited conformation reveals a multistage activation switch. Cell 102:387-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manser, E., T.-H. Loo, C.-G. Koh, Z.-S. Zhao, X.-Q. Chen, L. Tan, I. Tan, T. Leung, and L. Lim. 1998. PAK kinases are directly coupled to the PIX family of nucleotide exchange factors. Mol. Cell 1:183-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Massagué, J., and Y.-G. Chen. 2000. Controlling TGF-β signaling. Genes Dev. 14:627-644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Massagué, J., and D. Wotton. 2000. Transcriptional control by the TGF-β/Smad signaling system. EMBO J. 1745-1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Penheiter, S. G., H. Mitchell, N. Garamszegi, M. Edens, J. J. E. Doré, Jr., and E. B. Leof. 2002. Internalization-dependent and -independent requirements for transforming growth factor β receptor signaling via the Smad pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:4750-4759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piek, E., W. J. Ju, J. Heyer, D. Escalante-Alcalde, C. L. Stewart, M. Weinstein, C. Deng, R. Kucherlapati, E. P. Böttinger, and A. B. Roberts. 2001. Functional characterization of transforming growth factor β signaling in Smad2- and Smad3-deficient fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 276:19945-19953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prunier, C., A. Mazars, V. Noë, E. Bruyneel, M. Mareel, C. Gespach, and A. Afti. 1999. Evidence that Smad2 is a tumor suppressor implicated in the control of cellular invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 274:22919-22922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qu, J., M. S. Cammarano, Q. Shi, K. C. Ha, P. de Lanerolle, and A. Minden. 2001. Activated PAK4 regulates cell adhesion and anchorage-independent growth. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:3523-3533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raftery, L. A., V. Twombly, K. Wharton, and W. M. Gelbart. 1995. Genetic screens to identify elements of the decapentaplegic signaling pathway in drosophila. Genetics 139:241-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roig, J., Z. Huang, C. Lytle, and J. A. Traugh. 2000. p21-activated protein kinase γ-PAK is translocated and activated in response to hyperosmolarity. J. Biol. Chem. 275:16933-16940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roig, J., and J. A. Traugh. 2001. Cytostatic p21 G protein-activated protein kinase γ-PAK. Vitam. Horm. 62:167-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roig, J., P. T. Tuazon, P. A. Zipfel, A. M. Pendergast, and J. A. Traugh. 2000. Functional interaction between c-Abl and the p21-activated protein kinase γ-pak. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14346-14351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Royal, I., N. Lamarche, L. Lamorte, K. Kozo, and M. Park. 2000. Activation of Cdc42, Rac, PAK, and Rho-kinase in response to hepatocyte growth factor differentially regulates epithelial cell colony spreading and dissociation. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:1709-1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rudel, T., and G. M. Bokoch. 1997. Membrane and morphological changes in apoptotic cells regulated by caspase-mediated activation of PAK2. Science 276:1571-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savage, C., P. Das, A. L. Finelli, S. R. Townsend, C.-Y. Sun, S. E. Baird, and R. W. Padgett. 1996. Caenorhabditis elegans genes sma-2, sma-3, and sma-4 define a conserved family of transforming growth factor beta pathway components. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:790-794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schurmann, A., A. F. Mooney, L. C. Sanders, M. A. Sells, H. G. Wang, J. C. Reed, and G. M. Bokoch. 2000. p21-activated kinase 1 phosphorylates the death agonist Bad and protects cells from apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:453-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Serini, G., and G. Gabbiani. 1999. Mechanisms of myofibroblast activity and phenotype modulation. Exp. Cell Res. 250:273-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shipley, G. D., C. B. Childs, M. E. Volkenant, and H. L. Moses. 1984. Differential effects of epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor, and insulin on DNA and protein synthesis and morphology in serum-free cultures of AKR-2B cells. Cancer Res. 44:710-716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.ten Dijke, P., M.-J. Goumans, H. Itoh, and S. Itoh. 2002. Regulation of cell proliferation by Smad proteins. J. Cell. Physiol. 191:1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wells, C. M., A. Abo, and A. J. Ridley. 2002. PAK4 is activated via P13K in HGF-stimulated epithelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 115:3947-3956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang, F., X. Li, M. Sharma, M. Zarnegar, B. Lim, and Z. Sun. 2001. Androgen receptor specifically interacts with a novel p21-activated kinase, PAK6. J. Biol. Chem. 276:15345-15353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yue, J., and K. M. Mulder. 2001. Transforming growth factor-β signal transduction in epithelial cells. Pharmacol. Ther. 91:1-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]