Abstract

The heme-copper oxidase (HCuO) superfamily consists of integral membrane proteins that catalyze the reduction of either oxygen or nitric oxide. The HCuOs that reduce O2 to H2O couple this reaction to the generation of a transmembrane proton gradient by using electrons and protons from opposite sides of the membrane and by pumping protons from inside the cell or organelle to the outside. The bacterial NO-reductases (NOR) reduce NO to N2O (2NO + 2e− + 2H+ → N2O + H2O), a reaction as exergonic as that with O2. Yet, in NOR both electrons and protons are taken from the outside periplasmic solution, thus not conserving the free energy available. The cbb3-type HCuOs catalyze reduction of both O2 and NO. Here, we have investigated energy conservation in the Rhodobacter sphaeroides cbb3 oxidase during reduction of either O2 or NO. Whereas O2 reduction is coupled to buildup of a substantial electrochemical gradient across the membrane, NO reduction is not. This means that although the cbb3 oxidase has all of the structural elements for uptake of substrate protons from the inside, as well as for proton pumping, during NO reduction no pumping occurs and we suggest a scenario where substrate protons are derived from the outside solution. This would occur by a reversal of the proton pathway normally used for release of pumped protons. The consequences of our results for the general pumping mechanism in all HCuOs are discussed.

Keywords: cbb3, flow-flash, nitric oxide, proton pumping, pathway

Terminal oxidases catalyze the last step in the respiratory chain: the reduction of oxygen to water (see Eq. 1a). The enzymes of the respiratory chain are located in the mitochondrial inner membrane (of eukaryotes) or the inner cell membrane (of bacteria). Most terminal oxidases belong to the family of heme-copper oxidases (HCuOs), which get their name from their catalytic O2-binding center that is composed of a heme and a copper ion. Heme-copper oxidases couple the exergonic O2 reduction to the generation of a proton electrochemical gradient across the membrane. This is achieved in 2 ways: first, electrons and protons used to reduce O2 to H2O (Eq. 1a) are derived from opposite sides of the membrane; electrons from donors (often a cytochrome c) in the “outside” [positive (P) side] solution, and protons from the “inside” [negative (N) side]. Second, HCuOs are proton pumps, i.e., they translocate protons through the protein across the membrane (Eq. 1b). The resulting proton gradient is then used by the organism for energy-requiring processes.

The most studied heme-copper oxidases are of the type found in mitochondria, the aa3-type oxidases. These oxidases contain, in their catalytic subunit I, a low-spin heme a and a high-spin heme a3. Heme a3 forms, together with a Cu-ion close by (CuB), the catalytic site of oxygen reduction. There is an additional redox cofactor, CuA, that is bound to the extramembrane part of subunit II, a membrane-anchored protein. Protons are transferred through 2 proton pathways, the D pathway, leading from an aspartate (D-132, Rhodobacter sphaeroides aa3 numbering) at the cytoplasmic surface up to a glutamate (Glu-286) close to CuB, and the K pathway leading via lysine (K-362) up to the active site. The D pathway is presumably used for 6 or 7 of the 8 protons transferred per turnover, the protons used during oxidation of the active site, and the pumped protons. The K pathway is used for the remaining 1–2 protons that are taken up during reduction of the active site (1, 2). The pathway from the active site to the outside solution, used for the output of pumped protons, is largely unknown.

Heme-copper oxidases of the cbb3-type were first found in nitrogen-fixing and pathogenic bacteria, where they are expressed under low oxygen tension and have a lower Km for O2 than other HCuOs (3). The purified cbb3 oxidase consists of 3 cofactor-containing subunits: CcoN, related to the subunit I of the aa3-type, which contains the high-spin heme b3-CuB catalytic site and a low-spin heme b; CcoO that contains 1 c-type heme; and CcoP that contains 2 c-type hemes (4). There is also possibly a 4th small subunit, CcoQ (5), but with no cofactors. Sequence alignments of the catalytic subunits in the HCuO family have shown that in the cbb3-type oxidases there is no equivalent to the D pathway, and the pattern of conserved residues supports the presence of only 1 proton input pathway up to the catalytic site, spatially analogous to the K pathway (6, 7). The cbb3-type oxidases, however, have been shown to pump protons (8, 9).

Sequence alignments have also identified a different member of the family of heme-copper oxidases: the bacterial NO-reductase (NOR) (10, 11). The NORs perform part of the denitrification process, reducing NO to N2O (see Eq. 2).

Instead of the copper in the catalytic site, NORs contain a nonheme iron, which is thought to be important for efficient NO reduction. There are no crystal structures available for the cbb3 oxidases or the NORs, but models have been generated based on the homology to the known oxidase structures (12–15). In significant contrast to the O2-reducing HCuOs, NORs do not couple the energetically downhill reduction of NO, which is as exergonic as O2 reduction, to the generation of a proton gradient across the membrane. NO reduction by NOR is thus nonelectrogenic (14, 16, 17) and protons are taken up from the outside (periplasmic) solution (14). Different reasons are possible for the lack of coupling of NO reduction to the generation of a proton gradient. It is either determined by the enzyme, such that NORs have evolved into rapidly removing toxic NO rather than conserving energy, or it is determined by the substrate such that the chemical properties of the NO intermediates would make it difficult to couple the reaction to proton translocation (see refs. 14 and 18 and Discussion).

Among the O2-reducing HCuOs, the cbb3 type is the closest relative to NOR, and interestingly, the cbb3-type oxidase from Pseudomonas stutzeri was shown to have a substantial NO reduction activity of ≈2 e− s−1, in contrast to the mitochondrial-like aa3-type oxidases that show no such activity (19, 20). The capability of the cbb3s to reduce NO leads to the possibility to resolve the question about whether the substrate or the protein determines whether NO reduction can be linked to proton pumping; that is, do the cbb3 oxidases pump protons also while reducing NO? In this study we have explored this issue by studies of the effect of uncouplers on the steady-state reduction of O2 and NO in liposome-reconstituted cbb3. In addition, we have studied oxidation of the fully reduced cbb3 oxidase time-resolved by using the flow-flash technique in combination with electrometric detection and optical spectroscopy. Our results suggest that NO reduction is not coupled to proton translocation and we suggest that protons consumed in the reaction (see Eq. 2), are taken from the outside, periplasmic solution. Possible reasons for such uncoupling and its implications for the general pumping mechanism for HCuOs are discussed.

Results

Catalytic Activity with O2 and NO of the Detergent-Solubilized and Liposome-Reconstituted R. sphaeroides cbb3 Oxidase.

The turnover activity with O2 in the solubilized cbb3 varied between 250 and 600 e− s−1 for different preparations. The R. sphaeroides cbb3 was also found to catalyze NO reduction, with turnover numbers in the range from 2 to 10 e− s−1, higher than other published activities for heme-copper oxidases [0.05 e− s−1 and 0.5 e− s−1 for the ba3 and caa3 from Thermus thermophilus, respectively (20) and ≈2 e− s−1 for the cbb3 from Pseudomonas stutzeri (19)].

The liposome-reconstituted cbb3 had an uncoupled activity similar to that of the solubilized enzyme, and showed a respiratory control ratio of 3–7 when reducing O2. However, with NO, the respiratory control ration (RCR) was ≈1, indicating that NO reduction does not lead to the generation of a transmembrane proton gradient. Because NO reduction is much slower than O2 reduction, and could thereby be associated with smaller RCRs because of slow proton leaks across the membrane, the RCR with O2 was also measured at low mediator [N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine (TMPD) = 10 μM] concentration where the uncoupled rate was 4.5 e− s−1, i.e., similar to kcat with NO. The RCR at this slower O2 turnover was 2.3.

The Reaction of Fully Reduced cbb3 with O2 or NO; Time-Resolved Optical Detection.

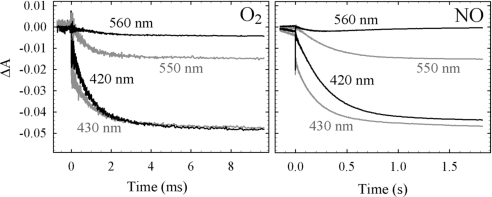

Fig. 1 shows the progress of the flow-flash reaction where the substrate (O2 or NO) is mixed rapidly with the fully reduced CO-bound cbb3, CO is then flashed off, allowing the substrate to bind and oxidize the cbb3.

Fig. 1.

Reaction of the fully reduced liposome-reconstituted cbb3 with O2 or NO in the flow-flash reaction. A laser flash initiates the reaction at t = 0. Shown are the absorbance changes at 430, 420, 550 (reporting oxidation of the c-type hemes), and 560 nm (reporting on the b-type hemes). Experimental conditions: ≈1.4 μM cbb3 after mixing (1:1), 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, [O2] = 0.6 mM or [NO] = 1 mM, T = 298 K. For other experimental details, see text.

With O2, the major phase of oxidation has a time constant (τ) = 1 ms (k = 1,000 s−1), and is seen in both the Soret region (see examples at 420 nm and 430 nm in Fig. 1), reporting the oxidation of all heme groups, and in the alpha region, shown at 550 nm and 560 nm in Fig. 1, reporting the oxidation of the low-spin hemes c and b, respectively.

With NO as the oxidant, the major phase of oxidation has a τ = 250 ms (k = 4 s−1), with amplitudes similar at all wavelengths to those obtained with O2.

At 560 nm, reporting the oxidation of the low-spin heme b, the amplitude varied between experiments for both substrates, and sometimes re-reduction was seen at longer times (on the timescale of seconds; data not shown). It should be noted that the fully reduced cbb3 contains 6 electrons (on the 2 c-hemes in CcoP, the heme c in CcoO, on the low-spin heme b, as well as on the high-spin heme b3 and the CuB in CcoN), whereas the complete reduction of O2 to H2O requires 4 electrons, which means that presumably 2 electrons remain somewhere in the protein after a single turnover. With NO, 2 electrons reduce 2 NOs to N2O, so the enzyme contains enough electrons for 3 turnovers. However, the extent of oxidation was similar for NO and O2, indicating that the reaction comprises 2 turnovers with NO. It is possible that the end product with NO after the τ = 250 ms phase has NO bound to the oxidized active site, inhibiting further electron transfer.

The Reaction of Fully Reduced cbb3 with O2 or NO; Electric Potential Generation.

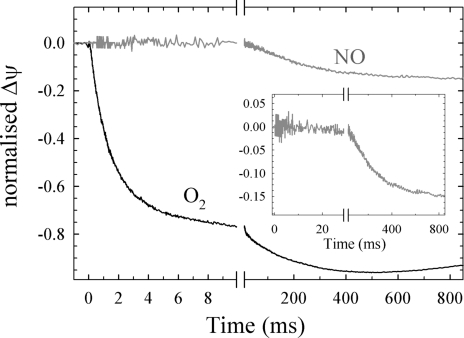

Fig. 2 shows the progress of the generation of electric potential in the flow-flash reaction where the substrate (O2 or NO) is injected into the chamber with the fully reduced CO-bound cbb3 in liposomes attached to a Teflon membrane.

Fig. 2.

Generation of electrical potential during the reaction between fully reduced cbb3 and either O2 or NO with the same sample. A laser flash initiates the reaction at t = 0. (Inset) A close-up of the small NO signal. The buffer and temperature used is the same as for Fig. 1. The HARC concentration was 40 μM. The relative amplitudes varied between experiments and the traces shown represent the average relationship between the O2 and NO signals. A linear drift has been subtracted from the traces. For further experimental details, see text.

With O2 as the oxidant, the major phase has a time constant of 1–2 ms (k = 500–1,000 s−1), corresponding to the major phase in the optical measurements. There is also a slower phase with a time constant and amplitude that vary with mediator [hexa-amineruthenium(II)-chloride (HARC)] concentration.

With NO as the oxidant, the small signal of negative electric potential generation had a time constant of 250 ms (k = 4 s−1), correlating well to the kinetics seen in the optical flow-flash measurements. The size of the signal with NO relative to that with O2 varied between experiments; it was on average 20 ± 10 (SD, n = 5) % of the amplitude of the τ = 1 ms phase with O2 (see in Fig. 2 Inset). We interpret the variation in amplitudes to be mainly due to a variation in the reduction level of the oxidase at the initiation of the reaction, which should vary “in both directions,” i.e., lead to both over- and underestimation of the signal size with NO, which would make the average signal the best estimation.

As a control that NO did not induce irreversible changes to the vesicles and/or Teflon coating, we repeated an O2 injection after the NO injection and obtained traces similar to the original O2 traces (data not shown).

To verify that the small negative signal with NO is due to oxidation of the protein and not to NO binding that can occur with any heme-copper oxidase, we studied the same reaction in the aa3 oxidase from R. sphaeroides, which gave no signal.

We note that the signal with O2 contains contributions from both rapid oxidation of the reduced cbb3 and, in part, also slower multiple turnover (or re-reduction; see Discussion) and that this multiple turnover could “hide” a relaxation of the membrane due to proton leaks on the timescale of the measurements with NO, leading to an underestimation of the size of the signal. Several lines of evidence point to this not being a major problem. First, when the mediator concentrations were kept low, we observed smaller O2 signals in total (these signals were not used for comparison with NO), but they contained no or very little slower phases, and from these experiments we could estimate better the “true” relaxation rates, which were still 1 s−1 or slower (data not shown; see also Materials and Methods). Second, experiments on aa3 oxidase from R. sphaeroides using the same experimental setup as here give similar amplitudes for the WT oxidase as for mutant oxidases where rate constants are comparable to those observed here for the reaction with NO (H.L. and P. Brzezinski, unpublished data).

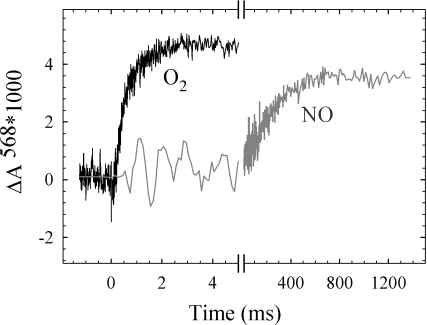

The Reaction of Fully Reduced cbb3 with O2 or NO; Proton Uptake from Solution.

To investigate whether the much smaller degree of generation of electric potential in cbb3 with NO compared with O2 was due to a much smaller degree of coupling of the electron transfer to proton uptake, we studied pH changes in solution during oxidation of the fully reduced detergent-solubilized cbb3 by either O2 or NO by using a pH-sensitive dye. The results, shown in Fig. 3, clearly demonstrate that protons are taken up from solution during both O2 and NO reduction, coupled to the major phases of oxidation as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 3.

Proton uptake from solution during the flow-flash reaction of the fully reduced solubilized cbb3 with either O2 or NO. Experimental details as in Fig. 1 except that no buffer was present, the mixing was 1:5, and the solution contained 0.03% DDM. The traces shown are differences where the trace in the presence of 50 mM Hepes has been subtracted from the trace in the absence of buffer.

The somewhat smaller amplitude observed with NO is presumably due to a somewhat higher buffering capacity of the NO solution.

Discussion

The cbb3 type oxidase from R. sphaeroides catalyzes both O2 and NO reduction. The measured NO reduction activity of 2–10 e− s−1 is higher than any published for a heme-copper oxidase, excluding the NORs. The turnover NO reduction activity is presumably not associated with generation of a transmembrane proton gradient, as manifested in the RCR of 1, whereas turnover O2 reduction is associated with an RCR of 3–7 (remaining at ≈2.5 when the turnover rate is comparable to that with NO; see Results).

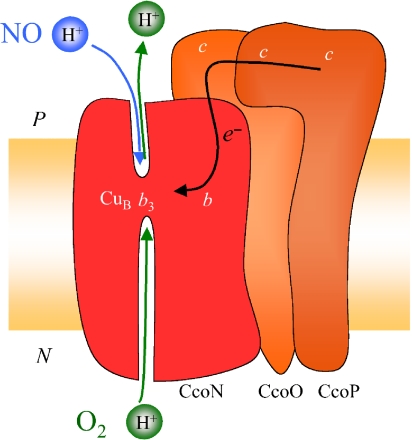

During oxidation of the fully reduced cbb3 we show that electron transfer from the hemes takes place with time constants of ≈1 ms with O2 and 250 ms with NO as the substrate. Both processes are coupled to the uptake of protons from the bulk solution, but only the reaction with O2 is associated with generation of a significant negative voltage across the membrane. We thus conclude that when the cbb3 reduces O2, substrate protons are used from the inner cytoplasmic space, and in addition, protons are presumably pumped across the membrane (see below). In contrast, when NO is the substrate, no pumping occurs and, furthermore, we suggest a scenario where the substrate protons needed for the reduction of NO to N2O (see Eq. 2) are taken from the outer (periplasmic) solution. Fig. 4 shows a schematic summary of this suggested scenario.

Fig. 4.

Schematic picture of the cbb3 oxidase summarizing the suggested scenario from the results from this study. Shown are the redox centers in the subunits CcoN (red), CcoO and CcoP (both orange), and their approximate location in relation to the membrane.

Generation of Electrical Potential.

With O2 as the oxidant, electrical potential is generated with τ = 1–2 ms, correlating with the time constant of heme oxidation observed by using optical detection. There is also a smaller slower phase with no clear counterpart in the optical data. This voltage change is presumably due to electron and proton flow during re-reduction or turnover resulting from the excess ascorbate present so that when comparing the amplitudes for O2 and NO, we only use the τ = 1 ms phase for O2. This way, the size with NO corresponds to 20 ± 10% of that with O2.

Among the heme centers in cbb3 oxidase, only electron transfer from the c-type hemes in CcoO and CcoP into the catalytic subunit (see Fig. 4) gives rise to electric potential. From the sizes of the optical signals at 550 nm, we estimate that all 3 c-type hemes oxidize with both O2 and NO (Fig. 1). From the size of the proton uptake signal (Fig. 3), we estimate that ≈2 H+ are taken up when O2 is the oxidant (similar to the scenario in aa3 oxidases where ≈2 H+ are taken up during oxidation and ≈2 H+ are “preloaded” on reduction (see, e.g., ref. 21). For simplicity, we will assume that the active site is located halfway through the membrane dielectric. In this way, the scenario that best fits the experimental data is the one where, during the τ = 1 ms phase with O2, 3 electrons move from the c-type hemes into the catalytic subunit, 2 substrate protons move from inside the vesicle to the active site, and we will assume that 1 proton is pumped across the membrane, leading to the transfer of −3.5 charge equivalents across the membrane in total. Our measurements do not discriminate between substrate and pumped protons; the pumping of 1 proton during this phase is a suggestion based on the observation of pumping of ≈0.5H+/e− (which is half of that observed for “classical” oxidases like the bovine or R. sphaeroides aa3) observed for cbb3 turnover in proteoliposomes (8).

During the τ = 250 ms phase with NO, 3 electrons still move from the c-type hemes, leading to the transfer of −1.5 charge equivalents (43% of −3.5) across the membrane, which is larger than the average observed signal, which was 20% of the rapid O2 signal. Therefore, we suggest that the substrate protons we know to be taken up (see Fig. 3) come from the outside solution to compensate. Assuming the uptake of 2 H+, the total charge transferred would be −0.5 (−1.5 + 1), which is 14% of the −3.5 charges with O2, within the errors observed correlating with observed amplitudes. Although in our measurements the amplitude with NO relative to that with O2 varied quite substantially between experiments, it was never > 30% of the O2 signal. Assuming this most extreme case, and taking other uncertainties into account (like the stoichiometry of proton uptake), uptake of substrate protons would occur from either side of the membrane leading to a total of −1.5 charge equivalents transferred, which is 43% of the presumed −3.5 charge equivalents moved with O2.

We note that in the time-resolved experiments presented in this study, the reductive phase is separated from the oxidative phase and the reaction is initiated from the fully reduced, CO-bound enzyme, when the oxidant (O2 or NO) is added. Where the protons presumably “preloaded” on reduction come from, and to where they are transferred is not known. It is possible that during steady-state turnover conditions, where our RCR measurements indicate that all protons for NO reduction come from the outside, the fully reduced state is never significantly populated so that no intermediates are shared between O2 and NO reduction.

Proton Transfer During NO Reduction in cbb3 Oxidase.

Also the bacterial NO-reductases (NORs) belong to the superfamily of heme-copper oxidases. However, even though NO reduction is similarly exergonic to O2 reduction, NORs do not pump protons, and substrate protons are taken from the periplasmic solution (14, 16, 17). Because the electrons also are donated from the same side of the membrane, the reaction is nonelectrogenic. Several explanations for this lack of electrogenicity have been suggested. For example, because NO is a toxic molecule, the protein has evolved to reduce it quickly rather than to preserve energy (22), or it has been suggested that the reason is more “chemical,” i.e., that NO reduction does not result in the formation of intermediates with high enough pKas, making it mechanistically difficult to couple proton translocation to the reaction (14, 18). Investigation of the coupling between NO reduction and proton translocation in the cbb3 oxidases should be informative in this regard, because these proteins, in contrast to the NORs, have the capability to pump during O2 reduction, so all structural elements needed for pumping are present. The results presented here, both RCR measurements and measurements of generation of electrical potential, indicate that there is no generation of electrochemical proton gradient in cbb3s during NO reduction. This means that no protons are pumped and we prefer a scenario where the substrate protons are derived from the outer periplasmic solution. This, in turn, supports the explanation that NO reduction is mechanistically difficult to couple to proton translocation in any protein, presumably because of the unfavorable pKas of the intermediates involved. Because NO reduction is presumably not of physiological importance in cbb3, they should not have developed a separate proton transfer pathway for this task. Thus, the substrate protons presumed to be taken from the outside solution are more likely transferred by reversing the direction of the pathway normally used for the output of the pumped protons. Little is known about the output path for pumped protons in HCuOs, both for the mitochondrial-like oxidases and the cbb3s. However, the cbb3s share 2 conserved glutamate residues at the “outer” protein surface with the NORs, which use protons from the periplasmic side. In NOR, these glutamates (Glu-122 and Glu-125, Paracoccus denitrificans NOR numbering) are needed for efficient catalysis (23) and they were recently shown to be specifically involved in the proton pathway and to define the proton donor to the active site (24). Mutation of the corresponding residues in the R. sphaeroides cbb3 leads to a significant reduction in O2-reducing activity (7), consistent with a direct involvement in proton transfer.

So, why would the cbb3 oxidase reverse the proton transfer pathway when reducing NO? In the flow-flash experiments presented here, we are measuring the potential generation during the very first turnover, i.e., in the absence of a transmembrane charge gradient, so it would be “as easy” to pull protons from the inside as from the outside. We suggest that the reason for proton uptake from the outside is the same as for not pumping protons with NO, i.e., that the pKas of intermediates generated at the active site are not high enough to pull protons from the “normal” proton donor. In the cbb3s, the identity of the immediate proton donor to the active site during O2 reduction is not known, but in the mitochondrial-like CcOs, this proton donor, Glu-286 (25) (R. sphaeroides aa3 numbering) has a pKa > 9 (26). So, presuming that the normal proton donor, sitting in the pathway leading from the inside, has a pKa that is too high to be deprotonated by the NO intermediates, protons would instead be pulled from a donor with a lower pKa, a candidate being one of the glutamates at the surface. In NOR, the proton donor located in this region has a pKa of 6.6 (27).

The reason for why some O2-reducing HCuOs can also reduce NO and others can not is not known, but has been suggested to be related to the affinity of CuB for ligands such as CO (20). As an alternative suggestion, we can speculate that the presence of a glutamate(s) (at the outer surface of the protein) with a pKa suitable for proton transfer to NO reduction intermediates is part of the reason why the cbb3s can reduce NO.

Assuming that all proton-pumping heme-copper oxidases use the same mechanistic principles for pumping, the uncoupling we presume occurs with NO where the total free energy available is as high as for O2, but where the intermediates are presumably formed with lower pKas, puts serious restraints on possible models for such a mechanism.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Purification of the cbb3 Oxidase.

R. sphaeroides cells from the strain cbb3Δ, carrying the overexpression plasmid pUI2803NHIS (5), was grown as described in ref. 5. Isolation of the cell membrane fraction and Ni2+-affinity purification of the cbb3 oxidase were carried out essentially as in ref. 5, with the following exceptions. The membrane fraction was solubilized with 0.5% (wt/vol) n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside (DDM). After 3 h of binding to the Ni resin, the mixture was loaded onto a column and washed with buffer A (20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl, and 0.01% (wt/vol) DDM) containing 5 mM [6 column volumes (CVs)], 10 mM (4 CVs), and finally 25 mM imidazole (1 CV). The bound cbb3 oxidase was then eluted with a stepwise gradient of buffer A containing 75 mM, 100 mM, and 150 mM histidine, and glycerol was added to final concentrations of 30%. The purified protein was stored at −80 °C until used. The concentration of the purified cbb3 was determined from the reduced-oxidized difference spectra by using a ε of 35 mM−1 cm−1 at 550 nm.

Determining cbb3 Steady-State Reduction Rates of O2 and NO.

The O2 and NO reduction activities of cbb3 oxidase were measured by using a Clark-type electrode (Hansatech) with a variable voltage setting (polarized at −0.7 V for O2 and −0.8 V for NO) essentially as in ref. 28. In brief, for NO reduction, the chamber was kept anaerobic by a gentle stream of N2, and the buffer contained the glucose/glucose oxidase/catalase system (30 mM glucose, 1 unit/ml glucose oxidase, and 20 units/ml catalase) to remove any remaining O2. Substrate NO was added by repeated injections of small volumes of saturated (2 mM) NO buffer. The reaction buffer typically contained 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM ascorbate, 0.5 mM TMPD, 0.1 mM horse-heart cytochrome c 0.01% DDM (for solubilized cbb3, and 250 μM O2 or 150 μM NO.

Reconstitution of cbb3 into Liposomes and Measurements of Respiratory Control Ratio.

Reconstitution of cbb3 into liposomes was induced by additions of BioBeads (BioRad) to a mix of cbb3 and liposomes made from soybean lipids (Sigma) solubilized in cholate as described in ref. 29. For the vesicles used in the electrical measurements, glycerol was added to 30% before instant freezing in liquid nitrogen and storage at −80 °C [an RCR (see below) of >3 was retained in the thawed vesicles]. The orientation of cbb3 in the liposomes, measured essentially as in ref. 30, was 90–95% “right-side out,” i.e., with the soluble parts of CcoO and CcoP subunits facing the outside solution.

To investigate whether a proton gradient was created across the membrane during turnovers with both O2 and NO, the respiratory control ratio (RCR) was measured. The RCR is the ratio between the activity obtained after adding valinomycin (a potassium-specific ionophore removing the electrical component of any formed proton gradient) and carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenyl-hydrazon (FCCP; a protonophore abolishing the chemical proton gradient) and the activity before these additions.

Flow-Flash Measurements; Optical Detection of Heme Oxidation and Proton Uptake.

The flow-flash measurements were performed on a setup described in ref. 31. Cbb3 solubilized or in liposomes was fully reduced with 2 mM ascorbate in the presence of 1 μM HARC before being exposed to CO in a modified Thunberg cuvette. The CO-bound protein (we noted that CO bound to both the b3 and to one of the c-type hemes as described in ref. 32, but to a degree that varied between samples and did not significantly influence the results described) was then mixed with saturated O2 (1.2 mM) or NO (2 mM) in 25 mM Hepes, 100 mM KCl (plus 0.01% DDM for solubilized protein) in a modified stopped-flow apparatus (Applied Photophysics). The protein concentration after mixing was 1.5–2 μM. After a 200-ms delay, a laser flash (Nd:YAG laser, Quantel) was applied, dissociating CO from the active site and allowing the substrates to bind and oxidize the protein. These reactions were monitored optically at different wavelengths to study oxidation of the different hemes. The spontaneous rate constant of CO dissociation from the b3 heme was measured at 430 nm in the same setup without flashing, to 0.3 s−1.

To measure proton uptake during oxidation of the cbb3, the protein was concentrated and passed through a PD-10 column (Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated with 100 mM KCl, 0.03% DDM, 50 μM EDTA, pH ≈ 7.6, to remove the buffer in the solution. Phenol red was added to 40 μM and the pH adjusted to ≈7.6. The protein sample was then reduced and CO bound as described before. The substrate-mixing solutions were prepared by bubbling O2 or NO through solutions containing 100 mM KCl, 50 μM EDTA, 0.03% DDM, and 40 μM phenol red, pH ≈ 7.6. Because NO reacts with any residual O2 and produces HNO3 through multistep reactions, it easily affects the pH in the unbuffered solution in a drastic way. To minimize such pH drifts, the glucose/glucose oxidase/catalase system was included in both the protein sample and the unbuffered NO-mixing solution. The pH of this solution was monitored by the absorbance of phenol red at 570 nm and adjusted just before the transfer to the flow-flash mixing syringes. The mixing solution containing buffer used as controls contained 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.6, 50 mM KCl, 50 μM EDTA, 0.03% DDM, and 40 μM phenol red.

Flow-Flash Measurements; Electrometric Detection.

The setup for the electrical measurements was described in ref. 33. In brief, the voltage changes during oxidation of the reduced protein by O2 or NO were measured by Ag/AgCl electrodes in 2 chambers separated by a thinly stretched lipid-coated Teflon film. Proteoliposomes containing 2–3 μM cbb3 were added to 1 chamber and the attachment to the Teflon film was induced by addition of 10 mM CaCl2. The measurements were conducted in a solution containing 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl. The whole setup was then placed in an air-tight box, air was exchanged for N2, and then for CO. To reduce the cbb3, ≈4 mM ascorbate and 25–50 μM HARC were added. The glucose/glucose oxidase/catalase system was also included in both chambers to remove residual O2 after each O2 injection. For injections with NO, 50–100 μM dithionite was added to the chamber that did not contain the proteoliposomes to ensure removal of residual NO after NO injections.

The rate of relaxation of the built-up potential back to the zero level in this setup depends in part on the tightness of the attached membrane vesicles, such that it puts an upper limit on the rate constant for proton leakage through the vesicles. This relaxation rate constant varied between experiments, but was typically slower or much slower than 1 s−1 (data not shown; see also Results), indicating well-sealed vesicles.

Data Handling and Analysis.

Typically, for the flow-flash traces, 5·104 to 5·105 data points were collected and the number of data points reduced to ≈1,000 by averaging (on a linear or logarithmic timescale). Rate constants were obtained by fitting either separately or globally (when data from multiple wavelengths were used) to a model of consecutive irreversible reactions by using the software package Pro-K (Applied Photophysics). Alternatively, rate constants were fitted as a sum of exponentials in Sigmaplot (Jandel Scientific).

Acknowledgments.

We thank Professor Samuel Kaplan (University of Texas Medical School, Houston) for the strain expressing the His-tagged cbb3, Professor Jon Hosler (University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS) for advice about the purification, and Professors Peter Brzezinski and Robert Gennis for stimulating discussions. This work was supported by The Swedish Research Council and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. Y.H. received a postdoctoral stipend from the Carl Trygger Foundation. P.Ä. is a Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Research Fellow supported by a Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation grant.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Ädelroth P, Gennis RB, Brzezinski P. Role of the pathway through K(I-362) in proton transfer in cytochrome c oxidase from R. sphaeroides. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2470–2476. doi: 10.1021/bi971813b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konstantinov AA, Siletsky S, Mitchell D, Kaulen A, Gennis RB. The roles of the 2 proton input channels in cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides probed by the effects of site-directed mutations on time-resolved electrogenic intraprotein proton transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9085–9090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preisig O, Zufferey R, Thöny-Meyer L, Appleby CA, Hennecke H. A high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase terminates the symbiosis-specific respiratory chain of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1532–1538. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.6.1532-1538.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pitcher RS, Cheesman MR, Watmough NJ. Molecular and spectroscopic analysis of the cytochrome cbb(3) oxidase from Pseudomonas stutzeri. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31474–31483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oh JI, Kaplan S. Oxygen adaptation. The role of the CcoQ subunit of the cbb3 cytochrome c oxidase of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16220–16228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pereira MM, Santana M, Teixeira M. A novel scenario for the evolution of haem-copper oxygen reductases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1505:185–208. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(01)00169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hemp J, et al. Comparative genomics and site-directed mutagenesis support the existence of only one input channel for protons in the C-family (cbb(3) oxidase) of heme-copper oxygen reductases. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9963–9972. doi: 10.1021/bi700659y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arslan E, Kannt A, Thöny-Meyer L, Hennecke H. The symbiotically essential cbb(3)-type oxidase of Bradyrhizobium japonicum is a proton pump. FEBS Lett. 2000;470:7–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toledo-Cuevas M, Barquera B, Gennis RB, Wikström M, Garcia-Horsman JA. The cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides, a proton-pumping heme-copper oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1365:421–434. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saraste M, Castresana J. Cytochrome oxidase evolved by tinkering with denitrification enzymes. FEBS Lett. 1994;341:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Oost J, et al. The heme-copper oxidase family consists of three distinct types of terminal oxidases and is related to nitric oxide reductase. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;121:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hemp J, Christian C, Barquera B, Gennis RB, Martínez TJ. Helix switching of a key active-site residue in the cytochrome cbb(3) oxidases. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10766–10775. doi: 10.1021/bi050464f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma V, Puustinen A, Wikström M, Laakkonen L. Sequence analysis of the cbb3 oxidases and an atomic model for the Rhodobacter sphaeroides enzyme. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5754–5765. doi: 10.1021/bi060169a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reimann J, Flock U, Lepp H, Honigmann A, Ädelroth P. A pathway for protons in nitric oxide reductase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1767:362–373. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kannt A, et al. The electron transfer centers of nitric oxide reductase: Homology with the heme-copper oxidase family. In: Canters GW, Vijgenboom E, editors. Biological Electron-Transfer Chains: Genetics, Composition and Mode of Operation. The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht; 1998. pp. 279–291. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell LC, Richardson DJ, Ferguson SJ. Identification of nitric oxide reductase activity in Rhodobacter capsulatus: The electron transport pathway can either use or bypass both cytochrome c2 and the cytochrome bc1 complex. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:437–443. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-3-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hendriks JH, Jasaitis A, Saraste M, Verkhovsky MI. Proton and electron pathways in the bacterial nitric oxide reductase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2331–2340. doi: 10.1021/bi0121050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blomberg LM, Blomberg MR, Siegbahn PE. A theoretical study on nitric oxide reductase activity in a ba(3)-type heme-copper oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:31–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forte E, et al. The cytochrome cbb3 from Pseudomonas stutzeri displays nitric oxide reductase activity. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:6486–6491. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giuffrè A, et al. The heme-copper oxidases of Thermus thermophilus catalyze the reduction of nitric oxide: Evolutionary implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14718–14723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ädelroth P, Ek M, Brzezinski P. Factors determining electron-transfer rates in cytochrome c oxidase: Investigation of the oxygen reaction in the R. sphaeroides enzyme. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1367:107–117. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00142-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zumft WG. Nitric oxide reductases of prokaryotes with emphasis on the respiratory, heme-copper oxidase type. J Inorg Biochem. 2005;99:194–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorndycroft FH, Butland G, Richardson DJ, Watmough NJ. A new assay for nitric oxide reductase reveals two conserved glutamate residues form the entrance to a proton-conducting channel in the bacterial enzyme. Biochem J. 2007;401:111–119. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flock U, et al. Defining the proton entry point in the bacterial respiratory nitric-oxide reductase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3839–3845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorbikova EA, Belevich NP, Wikström M, Verkhovsky MI. Time-resolved ATR-FTIR spectroscopy of the oxygen reaction in the D124N mutant of cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13141–13148. doi: 10.1021/bi701614w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Namslauer A, Aagaard A, Katsonouri A, Brzezinski P. Intramolecular proton-transfer reactions in a membrane-bound proton pump: The effect of pH on the peroxy to ferryl transition in cytochrome c oxidase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1488–1498. doi: 10.1021/bi026524o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flock U, Watmough NJ, Ädelroth P. Electron/proton coupling in bacter-ial nitric oxide reductase during reduction of oxygen. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10711–10719. doi: 10.1021/bi050524h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hendriks J, et al. The active site of the bacterial nitric oxide reductase is a dinuclear iron center. Biochemistry. 1998;37:13102–13109. doi: 10.1021/bi980943x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faxén K, Gilderson G, Ädelroth P, Brzezinski P. A mechanistic principle for proton pumping by cytochrome c oxidase. Nature. 2005;437:286–289. doi: 10.1038/nature03921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicholls P, Hildebrandt V, Wrigglesworth JM. Orientation and reactivity of cytochrome aa3 heme groups in proteoliposomes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1980;204:533–543. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(80)90065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brändén M, et al. On the role of the K-proton transfer pathway in cytochrome c oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5013–5018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081088398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pitcher RS, Brittain T, Watmough NJ. Complex interactions of carbon monoxide with reduced cytochrome cbb(3) oxidase from Pseudomonas stutzeri. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11263–11271. doi: 10.1021/bi0343469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lepp H, Svahn E, Faxén K, Brzezinski P. Charge transfer in the K proton pathway linked to electron transfer to the catalytic site in cytochrome c oxidase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4929–4935. doi: 10.1021/bi7024707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]