Abstract

Although cells of the immune system can produce thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), the significance of that remains unclear. Using 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends, we show that mouse bone marrow cells produce a novel in-frame TSHβ splice variant generated from a portion of intron 4 with all of the coding region of exon 5 but none of exon 4. The TSHβ splice variant gene was expressed at low levels in the pituitary but at high levels in the bone marrow and the thyroid, and the protein was secreted from transfected CHO cells. Immunoprecipitation identified an 8 kDa product in lysates of CHO cells transfected with the novel TSHβ construct, and a 17 kDa product in lysates of CHO cells transfected with the native TSHβ construct. The splice variant TSHβ protein elicited a cAMP response from FRTL-5 thyroid follicular cells and a mouse alveolar macrophage cell line. Expression of the TSHβ splice variant but not the native form of TSHβ was significantly upregulated in the thyroid during systemic virus infection. These studies characterize the first functional splice variant of TSHβ, which may contribute to the metabolic regulation during immunological stress, and may offer an new perspective for understanding autoimmune thyroiditis.

Keywords: isoform, thyrotropin, 5′ RACE analysis, metabolism, autoimmunity

Introduction

Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), along with luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, and chorionic gonadotropin, are members of a family of glycoprotein hormones. Glycoprotein hormones consist of a common α-subunit and unique β-subunits, the latter being responsible for hormone specificity1,2. As would be expected for molecules that are highly conserved evolutionarily, there is considerable homology at both the gene and protein levels between human and mouse TSHβ. In both species, the TSHβ polypeptide consists of 138 amino acids of which 20 amino acids comprise the signal peptide and 118 constitute the mature protein3. Overall, there is 82% homology at the nucleic acid level and 88% homology at the amino acid level between human (accession no. NM_000549) and mouse (accession no. NM_009432) TSHβ. The mouse TSHβ gene consists of 5 exons, with the coding region located in portions of exon 4 and exon 53. At present, the only evidence for alternative exon splicing for mouse TSHβ is in exons 1, 2, and 34,5, all of which are outside the TSHβ coding region. No evidence yet exists for alternative splicing of TSHβ either within the coding region itself, or in ways that affect expression of the TSHβ protein.

The thyroid hormones, thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), are essential deterministic factors that influence nearly every aspect of mammalian physiology, including basal metabolism, growth, development, mood, and cognition. TSH induces thyroid hormone synthesis by promoting the proteolytic conversion of thyroglobulin to T4 and T3 in thyroid follicles. Levels of thyroid hormones are controlled by the presence of circulating pituitary-derived TSH; feedback mechanisms, in particular T4 levels, modulate TSH synthesis via hypothalamic-derived thyrotropin releasing hormone1,6.

That there are extra-pituitary sources of TSH, including TSH produced by cells of the immune system, has been known for over twenty years7-9. Although TSH may have some activity as an immunoregulatory/cytokine-like molecule within the immune system10-13, several observations now point to a more direct link between immune system TSH and the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis. For example, hypophysectomized mice challenged with foreign antigen have increases in circulating T414. Inasmuch as the elevated levels of T4 in hypophysectomized mice could not be accounted for through classical pituitary-thyroid circuitry, this suggested that an extra-pituitary source of TSH was responsible. Additionally, TSH has been shown to be actively produced by a subset of CD11b+ bone marrow (BM) cells15. Moreover, following adoptive transfer of CD11+ BM cells from enhanced green-fluorescent protein (EGFP) transgenic mice into non-EGFP mice, EGFP+ cells traffic to the thyroid where they express TSH transcripts and secrete TSH16.

As part of our studies aimed at gaining a better understanding of the role of immune system-derived TSH, we conducted a comprehensive examination of murine BM mRNA using a panel of TSHβ primers. These studies revealed significant differences in gene expression in the BM compared to the pituitary in the 5′ region of TSHβ mRNA in exons 3 and 4. Using 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE), we have identified a novel in-frame TSHβ splice variant that is preferentially expressed in BM cells relative to native TSHβ. This isoform, the first functional alternatively-spliced form of murine TSHβ to be identified, is upregulated in thyroid tissues following systemic virus infection.

Results

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) and 5′ RACE analyses identify a novel TSHβ splice variant expressed in BM hematopoietic cells

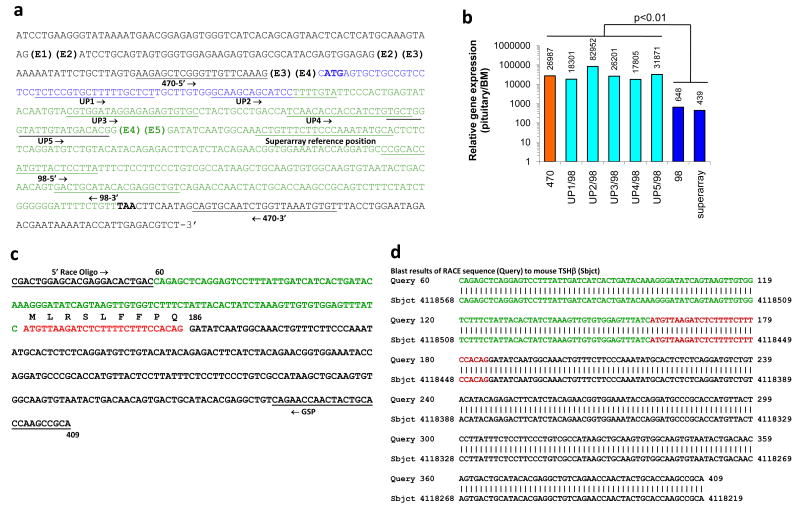

The full-length mRNA sequence is shown in Figure 1a, which indicates the positions of the five mouse TSHβ exons (designated E1 – E5), with the translated portion beginning with the ATG (bolded) at the second nucleotide of exon 4. The signal peptide is coded for by the region highlighted in blue; the translated portion of the mature peptide is highlighted in green; the location of the stop codon (TAA) is bolded.

Figure 1.

Characterization of a novel TSHβ splice variant produced in BM cells. (a) The full-length TSHβ mRNA sequence showing the locations of the five TSHβ exons (E1 – E5), and the primers used for qRT-PCR. (b) Results of qRT-PCR analyses using pituitary and BM RNA with the primer sets shown in panel a, indicating a statistically-significant difference (p<0.01) in gene expression comparing results when upstream primers sequences were targeted to exons 3 and 4 vs. upstream primer sequences targeted to exon 5. (c) Sequence of the 5′ RACE product generated with the 5′ RACE oligo and the downstream TSHβ GSP (underlined). The green and red nucleotides are a portion of intron 4 that immediately precedes exon 5 (black). The red portion represents the 27 nucleotides that begin with an ATG codon and continue in-frame through the RACE sequence. (d) Blast results of the 5′ RACE sequence reveal complete identity to the mouse TSHβ gene in portions of intron 4 (green and red) and exon 5 (black).

qRT-PCR analysis was done using primers targeted to several regions of mouse TSHβ mRNA. A primer set designated ‘470’; was used for PCR amplification with pituitary and BM RNAs. Those primer sequences, which span the TSHβ coding region, are targeted to a region in exon 3 (470-5′) and exon 5 (470-3′) (Figure 1a). Using the 470 primer set, we consistently observed a marked difference (26,987 fold greater) in the amount of amplified product for pituitary vs. BM RNA (Figure 1b). That pattern also held true using five additional upstream primers targeted to regions in exon 4 (designated UP1 – UP5) (Figure 1a and b) with a downstream primer targeted to exon 5 [designated 98-(3′)]. Conversely, when qRT-PCR analysis was done using two primer sets targeted to exon 5 (98-5′ to 98-3′, and Superarray) (Figure 1a), the fold difference in gene expression between pituitary vs. BM was 648 and 439, respectively (Figure 1b). This represented a statistically-significant (p<0.01) 62.8-fold reduction (34,019 vs. 543) in the relative gene expression of the ratio of pituitary/BM TSHβ expression using upstream primer sequences targeted to exons 3 or 4 compared to primers targeted to exon 5 (Figure 1b).

We hypothesized that the qRT-PCR differences between BM and pituitary RNAs as a function of the primer target location were due to alternative splicing of the TSHβ gene at or near the junction of exons 4 and 5. In order to obtain a sequence of BM TSHβ mRNA from that region, 5′ RACE analysis was done using a highly-purified preparation of BM RNA. RACE technology insured that only full-length, non-truncated mRNAs were used. A sequence, which was consistently obtained in multiple 5′ RACE cDNA clones, is shown in Figure 1c. The underlined nucleotide regions are the 5′ RACE oligo and the 3′ TSHβ GSP (Figure 1c). A gene blast search revealed complete homology to a portion of the mouse TSHβ gene as shown in Figure 1d. A striking finding from these experiments was that all of the 5′ RACE sequences obtained from BM RNA included a portion of intron 4 that was contiguous with exon 5. These sequences are highlighted in green and red in Figure 1c and d; the red nucleotides designate a part of intron 4 that includes a potential ATG (methionine) start codon followed by a sequence that codes for 9 amino acids (MLRSLFFPQ) that are in-frame with TSHβ exon 5 beginning at nucleotide 186 (Figure 1c). Using a program for identifying an open reading frame (ncbi/nlm/nih.gov), that ATG comprises an open reading frame with a Kozak sequence consisting of the ATC prior to the ATG triplet. These data thus point to a modified splicing mechanism for BM TSHβ, and they explain the low levels in PCR product from BM RNA using upstream primer sequences targeted to exons 3 or 4 vs. the abundance of product using primers targeted to exon 5.

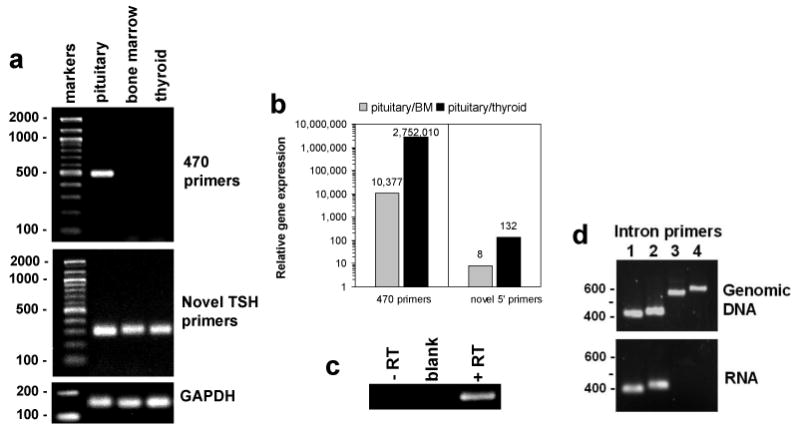

Relative to the expression of native TSHβ, the TSHβ splice variant is expressed at low level in pituitary cells but at high level in BM and thyroid cells

Conventional and realtime PCR analysis were done to determine whether the novel TSHβ splice variant was expressed in pituitary, BM, and/or thyroid tissues. For this, a new primer set designated ‘novel primers’ (Table 1 and Figure S1a) was used consisting of a 24 nucleotide upstream primer targeted to intron 4, and a downstream primer targeted to a sequence located just after the TAA stop codon of exon 5. If present, the novel TSHβ transcript would be amplified using these. Figure 2a indicates the relative gene expression levels using the 470 primer set and the TSHβ novel primer set. By conventional PCR, transcript levels using the 470 primers were detectable only in pituitary RNA (Figure 2a, top panel), whereas the novel TSHβ transcript was present in all three tissues – the pituitary, the BM, and the thyroid. These findings were confirmed by qRT-PCR (Figure 2b), which indicated an overwhelming preference for the native TSHβ using the 470 primer set with pituitary vs. BM or thyroid RNA. In contrast, the amount of levels of qRT-PCR amplification were more similar in those three tissues (Figure 2b), implying that there is a preferential use of the novel TSHβ splice variant in the BM and thyroid.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer designation | Sequence |

|---|---|

| 470 forward | 5′-AAGAGCTCGGGTTGTTCAAA-3′ |

| 470 reverse | 5′-CACATTTAACCAGATTGCACTG-3′ |

| UP1 forward | 5′-TCCCCGTGCTTTTTGCTCTT-3′ |

| UP2 forward | 5′-GCAAGCAGCATCCTTTTGTA-3′ |

| UP3 forward | 5′-CGTGGATAGGAGAGAGTGTGC-3′ |

| UP4 forward | 5′-TCAACACCACCATCTGTGCT-3′ |

| UP5 forward | 5′-TGCTGGGTATTGTATGACACG-3′ |

| 98 forward | 5′-CCGCACCATGTTACTCCTTA-3′ |

| 98 reverse | 5′-ACAGCCTCGTGTATGCAGTC-3′ |

| 5′ RACE oligo (forward) | 5′-CGACTGGAGCACGAGGACACTGAC-3′ |

| TSHβ GSP (reverse) | 5′-TGCGGCTTGGTGCAGTAGTTGGTTCTG-3′ |

| Novel TSH forward | 5′-ATCATGTTAAGATCTCTTTTCTTT-3′ |

| Novel TSH reverse | 5′-AACCAGATTGCACTGCTATTGAA-3′ |

| Intron primer 4 forward | 5′-TTGTTCAATGCATTTCTTTTAGC-3′ |

| Intron primer 3 forward | 5′-GAAAGGAAGTGGGGATAAATCA-3′ |

| Intron primer 2 forward | 5′-GATGGGTTAATTGTAGATGTGTGG-3′ |

| Intron primer 1 forward | 5′-CAGAGCTCAGGAGTCCTTTATTG-3′ |

| Superarray TSHβ (forward and reverse) | Cat. No. PPM30787A |

| Superarray GAPDH (forward and reverse) | Cat. No. PPM02946E |

Figure 2.

Native TSHβ is expressed at high levels in the pituitary but not in the bone marrow or in the thyroid, whereas the novel TSHβ splice variant is expressed in all three tissues. (α) PCR and agarose gel electrophoresis analysis of pituitary, bone marrow, and thyroid RNA using the 470 primer set that spans the TSHβ coding region yielded a product that was evident only from pituitary RNA. In contrast, using primers (see S1a) for the novel TSHβ splice variant, a PCR product of the anticipated size was obtained using RNA from all three tissues. (b) qRT-PCR was used to compare the ratio of the 470 PCR product and the novel splice variant product of pituitary/BM and pituitary/thyroid. Using the 470 primer set, there was an extremely high preference for expression of native TSHβ in the pituitary relative to the BM and thyroid. Using the novel primer set, however, the ratio of pituitary/BM and pituitary/thyroid was substantially lower. (c) To confirm that amplification using the novel primer set had not occurred from genomic DNA, a one-step PCR reaction was done in which reverse transcriptase was included or omitted. Note that amplification occurred only in the presence of reverse transcriptase, thus excluding the possibility that contaminating genomic DNA was present. (d) The presence of contaminating genomic DNA was also ruled out using four upstream primers targeted to intron 4 (see S1b). Amplification using those primers with the 98-3′ primer with genomic DNA yielded four PCR products of the anticipated sizes. In contrast, PCR products were obtained from BM RNA only with intron primers 1 and 2, both of which target a region near the 5′ RACE start site. These findings also confirm that the data shown in Figure 1c and d accurately reflect the 5′ RACE start site.

Because the novel TSHβ product was generated using an upstream primer targeted to a sequence of intron 4, experiments were done to rule out that amplification had occurred from genomic DNA. Three experiments confirmed that amplification was not due to genomic DNA. First, if genomic DNA were present, amplification with the 470 primer sets would yield larger PCR products due to the presence of introns 3 and 4. As seen in Figure 2a (top panel), all three samples were devoid of PCR products larger than the anticipated 470 nucleotide size. Second, when BM RNA was tested in a one-step PCR reaction in the absence or in the presence of reverse transcriptase using the novel upstream primer, a PCR product was obtained only in the presence of reverse transcriptase and not in the absence of reverse transcriptase (Figure 2c). Third, using four upstream primer sequences targeted to regions of intron 4 (Figure S1b), all yielded products of the correct size from genomic DNA, but only the two primers for regions at the beginning of the RACE sequence yielded products from BM RNA (Figure 2d). The latter not only confirmed the lack of genomic DNA in RNA preparations, but it also validated the 5′ RACE findings as accurately defining the beginning of the BM TSHβ splice variant.

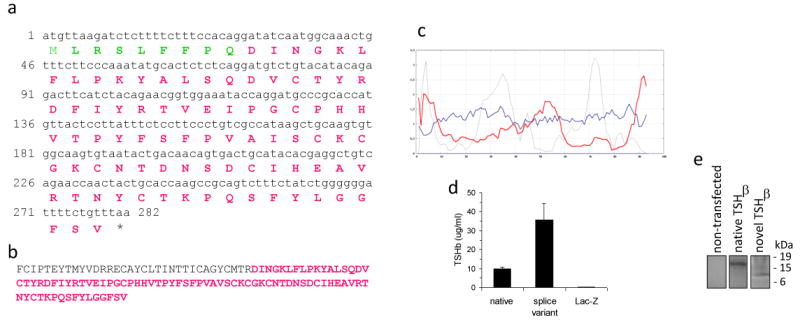

The novel TSHβ protein is an actively secreted protein

The physiochemical characteristics of the novel TSHβ polypeptide predicted from the nucleotide sequence is shown in Figure 3. This consists of a 9 amino acid leader sequence followed by an eighty-four amino acid polypeptide of the mature protein molecule coded for by exon 5 up to the TSHβ stop codon (Figure 3a). The difference between the novel TSHβ polypeptide (Figure 3b, red) and the native TSHβ molecule is the lack of amino acids coded for by exon 4. The secondary structure of the novel TSHβ splice variant is shown in Figure 3c, Note the high hydrophobic moment index (grey line; >3.0) and the high transmembrane helix preference (red line; 2.0) for the first 9 amino acids, thus favoring a transmembrane location and a likely signal peptide function. Importantly, cell-free supernatants from CHO cells transfected with native and splice variant TSHβ constructs had high levels of TSHβ as detected by reactivity with an anti-mouse TSHβ-specific monoclonal antibody17 (Figure 3d). Supernatants from control CHO cells transfected with a LacZ construct were non-reactive with the anti-TSHβ antibody. Since CHO cells were not transfected with the TSHα gene, it is assumed that the observed activity is due to TSHβ alone. These findings collectively indicate that the novel TSHβ product is actively secreted from cells.

Figure 3.

Amino acid composition of the novel TSHβ splice variant. (a) Predicted amino acid sequence of the novel TSHβ slice variant, consisting of a nine amino acid signal peptide (green residues) and an eighty-four amino acid polypeptide (red residues). (b) Location of the novel TSHβ isoform (red residues) within the 118 amino acid sequence of the mature native TSHβ molecule. (c) Secondary structure analysis of the novel TSHβ polypeptide. The grey line is the hydrophobic momentum index; the red line is the transmembrane helix momentum; the blue line is the beta preference index. Note the high hydrophobic momentum index and the high transmembrane helix momentum of the first 7-9 amino acids that would comprise the signal peptide. (d) TSHβ is secreted into the media from CHO cells transfected with native or splice variant TSHβ constructs, indicating that both forms of TSHβ are produced as secreted proteins. Control CHO cells transfected with LacZ had no detectable TSHβ. Data are mean values ± SEM of three replicate samples. (e) Cell lysates from non-transfected CHO cells were non-reactive by immunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitation of cell lysates from CHO cells transfected with the native TSHβ construct produced a 17 kDa product; a 8 kDa product was precipitated from lysates of CHO cells transfected with the novel TSHβ construct.

Immunoprecipitation was done using an anti-TSHβ antibody directed to a portion of the molecule that is shared by both native and novel TSHβ to confirm that transfected CHO cells produced TSHβ of the correct molecular size. Cell lysates from non-transfected CHO cells were non-reactive by immunoprecipitation (Figure 3e). Immunoprecipitation of cell lysates from CHO cells transfected with the native TSHβ construct produced a 17 kDa product; a 8 kDa product was precipitated from lysates of CHO cells transfected with the novel TSHβ construct (Figure 3e).

The TSHβ splice variant is biologically active and is upregulated in the thyroid during systemic virus infection

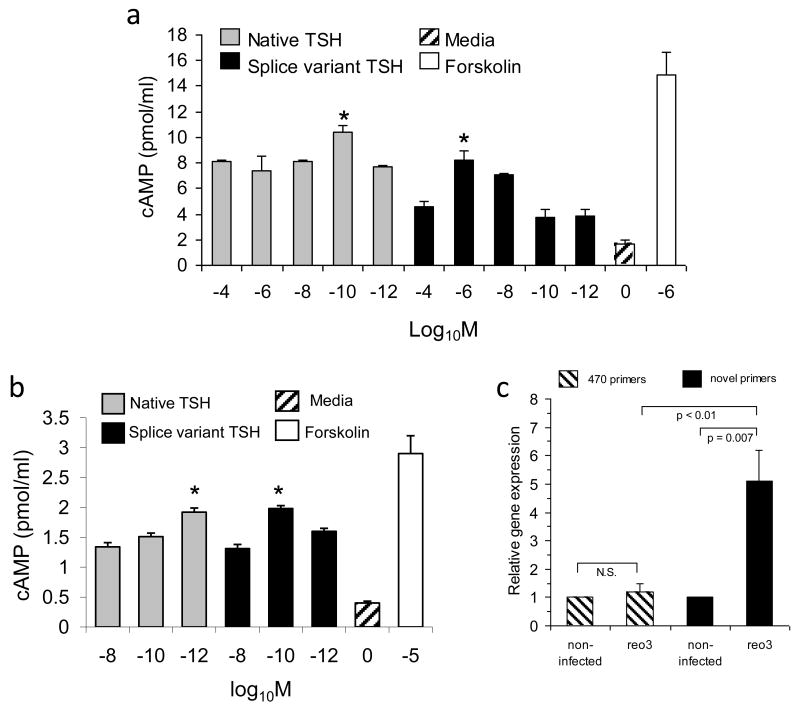

Recombinant native and splice variant proteins also were used to evaluate their ability to induce a cAMP response from mouse AM cells and rat FRTL-5 cells. As described in the Materials and Methods, cAMP activity was assayed in cell supernatants after 3 hr of TSH stimulation. Mouse AM cells were confirmed to express the TSH receptor by RT-PCR (data not shown). Culture of AM cells with recombinant native and splice variant TSHβ induced a cAMP responses with native TSHβ having peak activity at a concentration of 10-10M, and splice variant TSHβ having peak activity at a concentration of 10-6M (Figure 4a). Differences in those responses as a function of TSH concentration may reflect differences in receptor binding activities. Future studies are planned to examine this possibility.

Figure 4.

Recombinant novel TSHβ splice variant is capable of delivering a cAMP signal and is upregulated in the thyroid following systemic virus infection. (a) cAMP response of AM cells cultured with log10 dilutions of recombinant native TSHβ, splice variant TSHβ, media, or forskolin at the concentration indicated. Both forms of TSHb elicited a cAMP response in a dose-dependent fashion. (*p<0.05 compared to other molar concentrations for that form of TSH). Data are mean values ± SEM of four replicate samples. (b) FRTL-5 cells, seeded into 24 well plates as described in the Material and Methods, were cultured with log10 dilutions of recombinant native TSHβ, splice variant TSHβ, media, or forskolin at the concentrations indicated. Both forms of TSHβ elicited a cAMP response in a dose-dependent fashion. (*p<0.01 compared to other molar concentrations for that form of TSH). Data are mean values ± SEM of three replicate samples. (c) qRT-PCR analysis of RNA from thyroid tissues 48 hrs post-reovirus infection using the 470 and novel primer sets. Note the statistically-significant increase in the novel TSHβ splice variant gene expression in the thyroid of infected mice compared to non-infected mice, and the lack of change in the thyroid in gene expression of native TSHβ in the thyroid during virus infection as identified with the 470 primers. Data are mean values ± SEM of three replicate values. In each case, gene expression of virus infected mice was compared to that of non-infected mice, the latter being designated as a gene expression level of 1.0.

Using FRTL-5 cells, both native and the novel TSHβ splice variant induced dose-dependent cAMP responses (Figure 4b). Moreover, the optimal molar concentrations for these responses (10-10 − 10-12) were typical of TSH concentration used by others to induce cAMP responses in vitro18. The cAMP response induced by recombinant TSHβ proteins, although low, were generally in line with some reports of cAMP responses from FRTL-5 cells19. A lower cAMP response from FRTL-5 cells also may be due to poor binding of mouse TSH to rat FRTL-5 cells, an interpretation that is supported by the fact that bovine TSH generated a stronger cAMP response from FRTL-5 cells (8.83 pmol/ml and 7.75 pmol/ml cAMP following stimulation with 10-7 M and 10-9 M bovine TSH, respectively). Collectively, these findings confirm that the polypeptide made from the TSHβ splice variant is biologically active with regard to its ability to induce a cAMP signal.

Given our previous studies demonstrating that TSH-producing BM cells migrate to the thyroid16, we were interested in determining if immune challenge by virus would result in changes in intrathyroidal levels of native and/or splice variant TSHβ. C57BL/6 mice were infected i.p. with 107.5 pfu T3D reovirus. The rationale for using reovirus was based on studies demonstrating altered thyroid function following reovirus infection20,21. Thyroid tissues were isolated 48 hrs later, RNA was extracted, and qRT-PCR was done using the 470 and the novel TSHβ primer sets. Systemic virus infection did not alter the level of native TSHβ gene expression in the thyroid relative that of non-infected mice; however, there was a statistically-significant increase in gene expression of the TSHβ splice variant in the thyroid of virus-infected mice (Figure 4b). These findings suggest that the intrathyroidal host response is linked to the TSHβ splice variant but not the native form of TSHβ.

Discussion

This study has identified the first functionally-active splice variant of mouse TSHβ. The novel nature of this isoform, involving the retention of a portion of intron 4, makes it particularly intriguing. Splice variants that incorporate intronal pieces22-27, though once thought to be uncommon, appear to occur at a higher frequency than previously believed, possibly occurring in upwards of 15% of human and mouse genes28,29. However, most such splicing events are associated with disease conditions or with tumor cells, and they frequently result in truncated proteins or aborted translation due to the generation of a stop codon30. The splice variant described here consists of a portion of intron 4 and it includes all of the coding region of exon 5 but none of exon 4, thereby coding for a polypeptide that corresponds to 71.2% of the mature native TSHβ molecule. Interestingly, exon 5 of TSHβ, the coding portion retained in the novel TSHβ slice variant, is important for the biological function of TSH since it includes an 18 amino acid ‘seatbelt’ region (CNTDNSDCIHEAVRTNYC) that is used for attachment to the α-subunit. This suggests that the splice variant may retain the ability to function as a heterodimeric complex.

Using an adoptive cell transfer system involving EGFP BM cells injected into non-EGFP mice, we have demonstrated that some BM cells consistently traffic to the thyroid of healthy animals16. Trafficking also occurred using CD11b+ EGFP cells that were matured from BM cells by in vitro culture for 6 days with GM-CSF and injected into non-irradiated, non-EGFP recipient mice; twenty-five days later there was an abundance of EGFP+ cells surrounding thyroid follicular areas16. In those studies, donor EGFP+ cells were documented to produce TSHβ in situ by immunocytochemical staining. At that time we were unaware of the splice variant form of TSHβ, and the anti-TSHβ antibody used was generated to 12 amino acid residues of TSHβ that are coded for by exon 517. As such, that antibody would not discriminate between native and splice variant forms of TSHβ. From the present study, it is clear that the novel TSHβ splice variant is preferentially expressed in the bone marrow and the thyroid (Figure 2b and c), and that gene expression increases in the thyroid following systemic virus infection (Figure 4b). Inasmuch as BM cells appear to be a primary source of TSHβ in the thyroid15,16, the most likely interpretation of our findings is that the higher level of TSHβ gene expression is due either to an increase in TSH synthesis by resident BM cells in the thyroid, or that there is increased trafficking of BM cells to the thyroid during infection.

There are several potential ways in which immune system TSH might serve to regulate thyroid hormone activity. On the one hand it could function agonistically to elicit a thyroid hormone response leading to increases in T3 and T4 synthesis and an upregulation in cellular and physiologic metabolic activity. The fact that the TSHβ splice variant was capable of inducing a cAMP response provides some support for this possibility. Conversely, it is possible that the TSHβ splice variant has antagonistic activity which serves to restrict thyroid hormone synthesis by binding to and competing for TSH receptor signaling. Clearly, considerably more work will be needed to discriminate between these two possibilities in the context of both normal physiological conditions and in various pathological states. However, because the immune system is vested with the capacity to detect a wide range of threats to the health of the organism, including challenge due to acute and chronic infection, malignant conditions, and debilitating conditions such as coronary disease, the network described here provides an additional source of information that is not typically incorporated in sensory processing by the neuroendocrine system. Microregulation of thyroid hormone activity by immune system TSH may be important for adjusting to altered metabolic demands during times when energy conservation is needed.

Finally, it should be noted that a system such as this could have negative consequences for the host, particularly if the TSHβ splice variant displays an enhanced potential for immunogenicity relative to native TSHβ. Local intrathyroidal production of the TSHβ splice variant under the scenario described above may inadvertently lead to the generation of anti-TSH autoantibodies and autoimmune thyroiditis, as can occur following systemic virus infection21.

Materials and methods

Mice

6-8 week old female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Indianapolis, IN). Mice were used in accord with University of Texas Health Science Center institutional animal welfare guidelines.

RNA isolation and PCR analyses

qRT-PCR analysis was done using RNA isolated with an RNAeasy Protect Mini Kit-50; samples were treated with DNase using an RNase-Free DNase Set-50 (Qiagen; Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocols. RNA concentrations were determined at A260. Primer sets were purchased from IDT Technologies (Coralville; IA) or Superarray Bioscience Corp. (Frederick, MD). qRT-PCR was performed on 100 ng total RNA using an iScript One-Step RT-PCR kit with SYBR Green (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA). A blank sample with RNase-free water was used for primer controls. Amplification was done in 96-well thin-wall plates sealed with optical quality film in a Mini-Opticon (Bio-Rad) with a program of 10 min at 50°C for cDNA synthesis, 5 min at 95°C for reverse transcriptase inactivation, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 10s and 55°C for 30s for data collection. A melt curve was performed using a protocol of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 55°C, increasing the temperature in 0.5°C increments for 80 cycles of 10s each. Real-time PCR data were quantified using the 2-ΔΔCt method of Livak and Schmittgen31; samples were normalized to respective GAPDH values using a Gene Expression Macro Version 1.1 program (Bio-Rad).

5′ RACE, cloning, sequencing and generation of recombinant proteins

5′ RACE was done using a GeneRacer Kit (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, highly pure RNA isolated from BM cells was dephosphorylated with calf intestinal phosphatase to insure that only full-length non-truncated mRNA was used. RNA was treated with tobacco acid pyrophosphatase to remove the 5′ cap structure from intact full-length mRNA. A 5′ RACE Oligo provided with the kit was ligated to the 5′ end of the mRNA. The ligated mRNA was reverse transcribed using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase to create a RACE-ready first strand cDNA. The cDNA was amplified using Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase with the 5′ RACE Oligo primer and a TSH gene specific primer (GSP). The RACE PCR products were purified using an S.N.A.P. column provided with the kit. PCR products were cloned into a pCR4BLUNT-TOPO vector using a TOPO cloning kit (Invitrogen). Chemically competent E. coli were transformed with 4 μl of the 5′ RACE PCR product; transformed cells were selected based on kanamycin resistance. The clones were grown overnight in LB broth in the presence of kanamycin. Plasmid DNA was purified using a Qiagen QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, Inc; Valencia, CA). Sequencing was done by Seqwright, Inc. (Houston, TX) using M13 primers.

To obtain recombinant proteins, native TSHβ and splice variant TSHβ DNAs were subcloned into pcDNA3.1/V5-His-TOPO vectors. Plasmid DNA was obtained using standard methods. CHO cells grown in serum-free CHO-CD media (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) were transfected with native or novel plasmid DNA using an Amaxa electroporator (Amaxa Biosystems; Gaithersburg, MD). Cells were selected for stable tranfectants by continuous culture in 1.2 mg/ml neomycin. 107 cells were used to purify His-tagged recombinant proteins using a NI-NTA Fast Start Kit (Qiagen). Estimate of protein concentration was determined using a Coomassie Plus-200 Protein assay (Pierce; Rockford, IL). Recombinant proteins were stored at -80°C in the presence of 0.5% bovine serum albumin for stabilization.

cAMP assay

FRTL-5 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The moue alveolar macrophage cells line, AMJ2-C8 (American Type Culture Collection), hereafter referred to as AM, was a gift from Dr. Chinnaswamy Jagannath, Department of Pathology, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. FRTL-5 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2mM L-glutamine, 10μg/ml insulin, 10nM hydrocortisone, 5μg/ml transferin, 10ng/ml gly-his-lys-acetate, 10ng/ml somatostatin, and 10mU/ml bovine TSH (Sigma-Aldrich). AM cells were grown in defined serum-free hybridoma medium (Gibco-Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 2mM L-glutamine. 5-7 days prior to stimulation with native and splice variant TSHβ, media lacking bovine TSH was used for FRTL-5. FRTL-5 cells were grown to 80% confluency in 24 well Corning tissue culture plates (Fisher Scientific; Pittsburgh, PA); AM cells were grown to a density of 1-2×106/ml. As described by others18, FRTL-5 cells were washed twice with HBSS containing 0.4% BSA, 220mM sucrose, and 1mM isobutylmethylxanthine (Sigma). AM cells were washed and seeded at a density of 1×106 cell/ml in 1.5 ml eppendorf tubes. Log10M dilutions of recombinant native TSHβ, splice variant TSHβ, forskolin, or media for control cultures was added for 3 hr at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Cell free supernatants were collected and assayed for cAMP activity using a commercial assay kit (R&D Systems; Minneapolis, MN).

Immunoprecipitation

2×106 non-transfected CHO cells, CHO cells transfected with native TSHβ, and CHO cells transfected with splice variant TSHβ were lysed on ice for 15 min in buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCL (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1mM EGTA, 2 μg/ml aprotinin 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 mM phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride (Sigma, all reagents). Lysates were clarified by high speed centrifugation in a microfuge for 5 min. Supernatants were collected and pre-cleared by end-over-end mixing overnight with 50 μl of protein G plus agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies; Santa Cruz, CA). Protein G was removed from lysates by three successive centrifugation. Lysates were reacted by end-over-end mixing for 1 hr at 4°C with 25 μl of anti-TSHβ antibody (N-19) (Santa Cruz) adsorbed to protein G. Protein G immune complexes were washed with lysis buffer and suspended in 30 μl of Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA) containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol, boiled for 5 min, and electrophoresed though a pre-cast 12% polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad). Gels were fixed and exposed to silver staining using the reagents and methods of M. Barton Frank (http://omrf.ouhsc.edu/∼frank/SILVER.html).

Enzyme-linked immunoassay (EIA)

Because there are no commercially-available mouse TSH EIA assays, the EIA used in this study was similar to a procedure developed and published by our laboratory using an anti-mouse TSHβ antibody17.

Reovirus infection of mice

Reovirus serotype 3 Dearing strain (T3D reovirus) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. Virus stocks were grown as previously described32. Mice were infected i.p. with 107.5 pfu T3D reovirus or with PBS to serve as non-infected control animals. Two days post-infection, mice were euthanized, thyroid tissues were recovered and used for RNA extraction for qRT-PCR analysis with native and splice variant primers.

Statistical analyses

Determination of statistical significance was done by ANOVA or by a t-test for two samples with unequal variance.

Supplementary Material

(S1a) location of the novel TSHβ primers consisting of a 24 nucleotide upstream primer targeted to a region within intron 4 and a downstream primer sequence located just after the TAA TSHβ stop codon. (S1b) Location of the four upstream intron primers used for the experiment in Figure 2d.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants DK035566 and DE015355.

References

- 1.Kelly GS. Peripheral metabolism of thyroid hormones: a review. Altern Med Rev. 2000;5(4):306–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szkudlinski MW, Fremont V, Ronin C, Weintraub BD. Thyroid-stimulating hormone and thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor structure-function relationships. Physiol Rev. 2002;82(2):473–502. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon DF, Wood WM, Ridgway EC. Organization and nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the beta-subunit of murine thyrotropin. DNA. 1988;7(1):17–26. doi: 10.1089/dna.1988.7.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood WM, Gordon DF, Ridgway EC. Expression of the beta-subunit gene of murine thyrotropin results in multiple messenger ribonucleic acid species which are generated by alternative exon splicing. Mol Endocrinol. 1987;1(12):875–83. doi: 10.1210/mend-1-12-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf O, Kourides IA, Gurr JA. Expression of the gene for the beta subunit of mouse thyrotropin results in multiple mRNAs differing in their 5′-untranslated regions. J Biol Chem. 1987;262(34):16596–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shupnik MA. Thyroid hormone suppression of pituitary hormone gene expression. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2000;1(12):35–42. doi: 10.1023/a:1010008318961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruger TE, Smith LR, Harbour DV, Blalock JE. Thyrotropin: an endogenous regulator of the in vitro immune response. J Immunol. 1989;142(3):744–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith EM, Phan M, Kruger TE, Coppenhaver DH, Blalock JE. Human lymphocyte production of immunoreactive thyrotropin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80(19):6010–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.19.6010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harbour DV, Kruger TE, Coppenhaver D, Smith EM, Meyer WJ., 3rd Differential expression and regulation of thyrotropin (TSH) in T cell lines. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1989;64(2):229–41. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(89)90150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley KW, Weigent DA, Kooijman R. Protein hormones and immunity. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(4):384–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fabris N, Mocchegiani E, Provinciali M. Pituitary-thyroid axis and immune system: a reciprocal neuroendocrine-immune interaction. Horm Res. 1995;43(13):29–38. doi: 10.1159/000184234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whetsell M, Bagriacik EU, Seetharamaiah GS, Prabhakar BS, Klein JR. Neuroendocrine-induced synthesis of bone marrow-derived cytokines with inflammatory immunomodulating properties. Cell Immunol. 1999;192(2):159–66. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dardenne M, Savino W. Interdependence of the endocrine and immune systems. Adv Neuroimmunol. 1996;6(4):297–307. doi: 10.1016/s0960-5428(97)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bagriacik EU, Zhou Q, Wang HC, Klein JR. Rapid and transient reduction in circulating thyroid hormones following systemic antigen priming: implications for functional collaboration between dendritic cells and thyroid. Cell Immunol. 2001;212(2):92–100. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang HC, Dragoo J, Zhou Q, Klein JR. An intrinsic thyrotropin-mediated pathway of TNF-alpha production by bone marrow cells. Blood. 2003;101(1):119–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein JR, Wang HC. Characterization of a novel set of resident intrathyroidal bone marrow-derived hematopoietic cells: potential for immune-endocrine interactions in thyroid homeostasis. J Exp Biol. 2004;207(Pt 1):55–65. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Q, Wang HC, Klein JR. Characterization of novel anti-mouse thyrotropin monoclonal antibodies. Hybrid Hybridomics. 2002;21(1):75–9. doi: 10.1089/15368590252917674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patibandla SA, Dallas JS, Seetharamaiah GS, Tahara K, Kohn LD, Prabhakar BS. Flow cytometric analyses of antibody binding to Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing human thyrotropin receptor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(6):1885–93. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.6.4020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chico Galdo V, Massart C, Jin L, et al. Acrylamide, an in vivo thyroid carcinogenic agent, induces DNA damage in rat thyroid cell lines and primary cultures. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;257-258:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neufeld DS, Platzer M, Davies TF. Reovirus induction of MHC class II antigen in rat thyroid cells. Endocrinology. 1989;124(1):543–5. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-1-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Srinivasappa J, Garzelli C, Onodera T, Ray U, Notkins AL. Virus-induced thyroiditis. Endocrinology. 1988;122(2):563–6. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-2-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ding WQ, Kuntz SM, Miller LJ. A misspliced form of the cholecystokinin-B/gastrin receptor in pancreatic carcinoma: role of reduced sellular U2AF35 and a suboptimal 3′-splicing site leading to retention of the fourth intron. Cancer Res. 2002;62(3):947–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chand HS, Ness SA, Kisiel W. Identification of a novel human tissue factor splice variant that is upregulated in tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(7):1713–20. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sironen A, Thomsen B, Andersson M, Ahola V, Vilkki J. An intronic insertion in KPL2 results in aberrant splicing and causes the immotile short-tail sperm defect in the pig. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(13):5006–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506318103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaillon O, Bouhouche K, Gout JF, et al. Translational control of intron splicing in eukaryotes. Nature. 2008;451(7176):359–62. doi: 10.1038/nature06495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baralle D, B M. Splicing in action: assessing disease causing sequence changes. J Med Genet. 2005;42(10):737–48. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.029538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown PJ, Kagaya R, Banham AH. Characterization of human FOXP1 isoform 2, using monoclonal antibody 4E3-G11, and intron retention as a tissue-specific mechanism generating a novel FOXP1 isoform. Histopathology. 2008;52(5):632–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.02990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galante PA, Sakabe NJ, Kirschbaum-Slager N, de Souza SJ. Detection and evaluation of intron retention events in the human transcriptome. Rna. 2004;10(5):757–65. doi: 10.1261/rna.5123504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kan Z, States D, Gish W. Selecting for functional alternative splices in ESTs. Genome Res. 2002;12(12):1837–45. doi: 10.1101/gr.764102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Black DL. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:291–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montufar-Solis D, Garza T, Teng BB, Klein JR. Upregulation of ICOS on CD43+ CD4+ murine small intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes during acute reovirus infection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342(3):782–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(S1a) location of the novel TSHβ primers consisting of a 24 nucleotide upstream primer targeted to a region within intron 4 and a downstream primer sequence located just after the TAA TSHβ stop codon. (S1b) Location of the four upstream intron primers used for the experiment in Figure 2d.