Abstract

Bax is a member of the Bcl-2 family that, together with Bak, is required for permeabilisation of the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM). Bax differs from Bak in that it is predominantly cytosolic in healthy cells and only associates with the OMM after an apoptotic signal. How Bax is targeted to the OMM is still a matter of debate, with both a C-terminal tail anchor and an N-terminal pre-sequence being implicated. We now show definitively that Bax does not contain an N-terminal import sequence, but does have a C-terminal anchor. The isolated N-terminus of Bax cannot target a heterologous protein to the OMM, whereas the C-terminus can. Furthermore, if the C-terminus is blocked, Bax fails to target to mitochondria upon receipt of an apoptotic stimulus. Zebra fish Bax, which shows a high degree of amino acid homology with mammalian Bax within the C-terminus, but not the N-terminus, can rescue the defective cell death phenotype of Bax/Bak deficient cells. Interestingly, we find that Bax mutants which themselves cannot target mitochondria or induce apoptosis are recruited to clusters of activated wildtype Bax on the OMM of apoptotic cells. This appears to be an amplification of Bax activation during cell death that is independent of the normal tail-anchor mediated targeting.

Keywords: Bax, mitochondria, tail anchor, apoptosis

Introduction

The Bcl-2 family of proteins are important regulators of the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis (1). The major site of action of these proteins is on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), where they regulate release of factors, including cytochrome c and Smac/Diablo, from the intermembrane space (IMS) to the cytosol, initiating caspase activation. Bax and Bak, pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, show a high degree of sequence similarity and are absolutely required for cells to permeabilise the OMM (2). Given this similarity, it is surprising that Bax and Bak show a significant difference in their regulation. Bak is permanently on the OMM, whereas Bax is predominantly an inactive monomer in the cytosol of healthy cells (3, 4). Upon receipt of an apoptotic signal, Bax translocates to the mitochondria where it is thought to oligomerise into an active transmembrane pore (5-10).

Most mitochondrial proteins are post-translationally targeted to their destination (11). This targeting is a complex process; each protein having an addressing signal to specifically reach the intended mitochondrial compartment. Most proteins imported into mitochondria contain an N-terminal pre-sequence that is recognised by components of the general import pore (GIP), consisting of the TOM and TIM translocases (11). These span the OMM and inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) respectively. N-terminal pre-sequences contain an amphipathic α-helix, but the exact sequence, surrounding amino acids, and whether it is cleaved, determine to which mitochondrial compartment the protein is delivered.

Another class of targeting signal is the C-terminal tail anchor (12). A common feature of tail-anchored proteins is a moderately hydrophobic transmembrane domain (TMD), flanked on both sides by basic amino acids (13, 14). The Bcl-2 proteins Bak, Bcl2, Bcl-XL, Bcl-w and Mcl-l have C-terminal sequences meeting these criteria (15). Bax has a hydrophobic tail that is flanked only at its C-terminus by basic amino acids (16). Nonetheless Bax targets to the OMM, possibly suggesting that other regions determine its mitochondrial localisation. Recently, it was suggested that the Bax C-terminus is not a tail anchor, but that its N-terminus contains a targeting sequence for the TOM complex (17-21). In contrast, other reports suggest a C-terminal anchor is required for Bax translocation during apoptosis (22-24).

Due to the conflicting evidence for the roles of its N- and C-termini in Bax function, we have examined the relative contributions of each as a mitochondrial targeting sequence. We show that Bax targeting to mitochondria occurs in two distinct phases. The first occurs exclusively through a C-terminal tail anchor, and is an obligate step for Bax dependent apoptosis. During OMM permeabilisation a second wave of Bax recruitment to mitochondria occurs which is tail anchor independent. This second wave requires activated Bax or Bak to be present on the OMM, and may represent amplification of apoptotic pore formation. Distinguishing between these two phases is important in order to understand how Bax translocation is regulated.

Results

Blocking the C-terminus of Bax abrogates its pro-apoptotic function by preventing its recruitment to mitochondria

A number of publications have reported that, unlike other multi-domain Bcl-2 proteins, Bax targeting to the OMM is determined not by a C-terminal anchor sequence but rather by an N-terminal import sequence (17-21). To directly test this, we generated constructs to express Bax tagged at either the N- or C-terminus with YFP/GFP. Our reasoning was that if either were required for membrane targeting, the addition of GFP would abrogate that function.

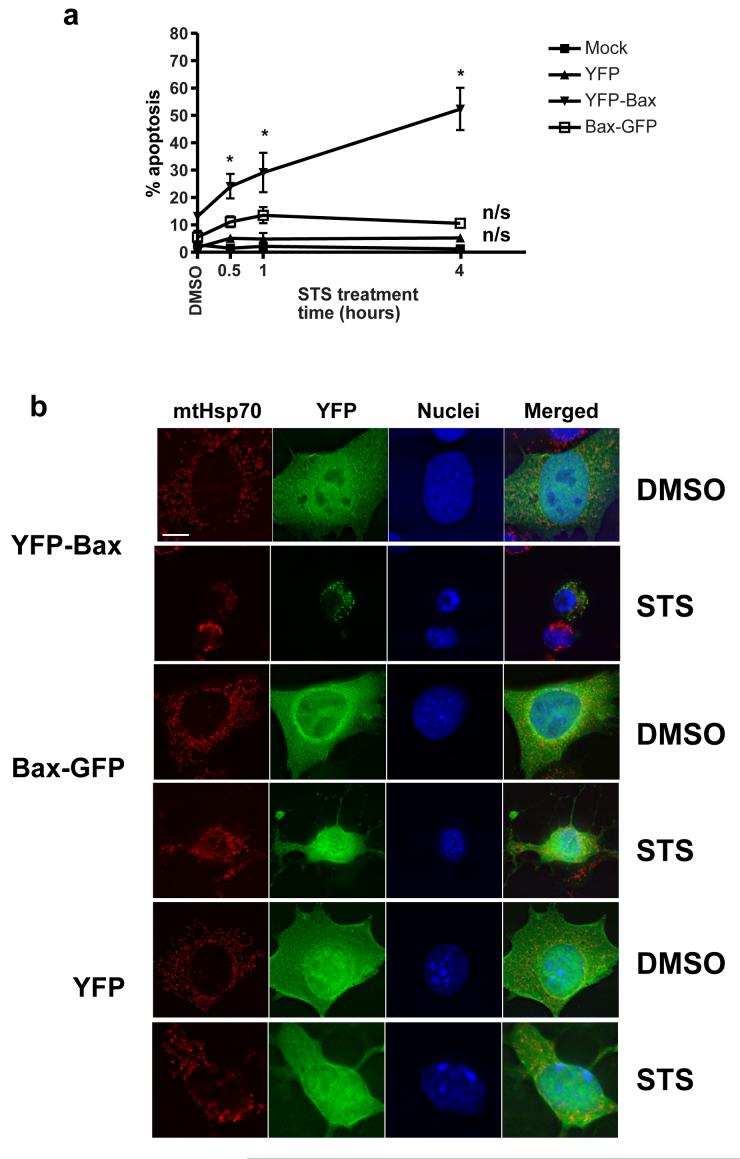

We asked if YFP-Bax or Bax-GFP restored sensitivity of Bax/Bak double knockout fibroblasts (DKO cells) to staurosporine. YFP-Bax, Bax-GFP or YFP alone were transiently expressed in DKO cells, which were then treated with staurosporine for various times (Fig. 1a). There was no significant apoptosis in any of the cells prior to staurosporine treatment. Following staurosporine treatment, YFP-Bax expressing cells showed significant apoptosis after 30 minutes. Neither YFP alone nor Bax-GFP significantly increased the sensitivity of DKO cells to staurosporine. When we examined the subcellular distribution of YFP, YFP-Bax and Bax-GFP we observed that all were diffuse throughout the cytoplasm of untreated cells (Fig. 1b). Following treatment with staurosporine, only YFP-Bax showed a punctate distribution associated with a mitochondrial marker (mtHsp70).

Figure1. Blocking the C-terminus of Bax blocks its apoptotic potential in DKOs.

(a) DKO cells were transiently transfected with YFP, YFP-Bax and Bax-GFP and treated with vehicle (DMSO) alone or 10 μM staurosporine for various times. Apoptosis was quantified by nuclear morphology of those cells expressing YFP alone or tagged Bax. Data was compared by two-way ANOVA, with significant p-values indicated by *, and n/s denoting significant. Error bars show standard error of the mean, and the data represents three independent experiments. (b) DKO cells grown on coverslips were transiently transfected as before and either treated with DMSO or staurosporine (STS) for 4 hours after which they were fixed and immunostained for mtHsp-70. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst.

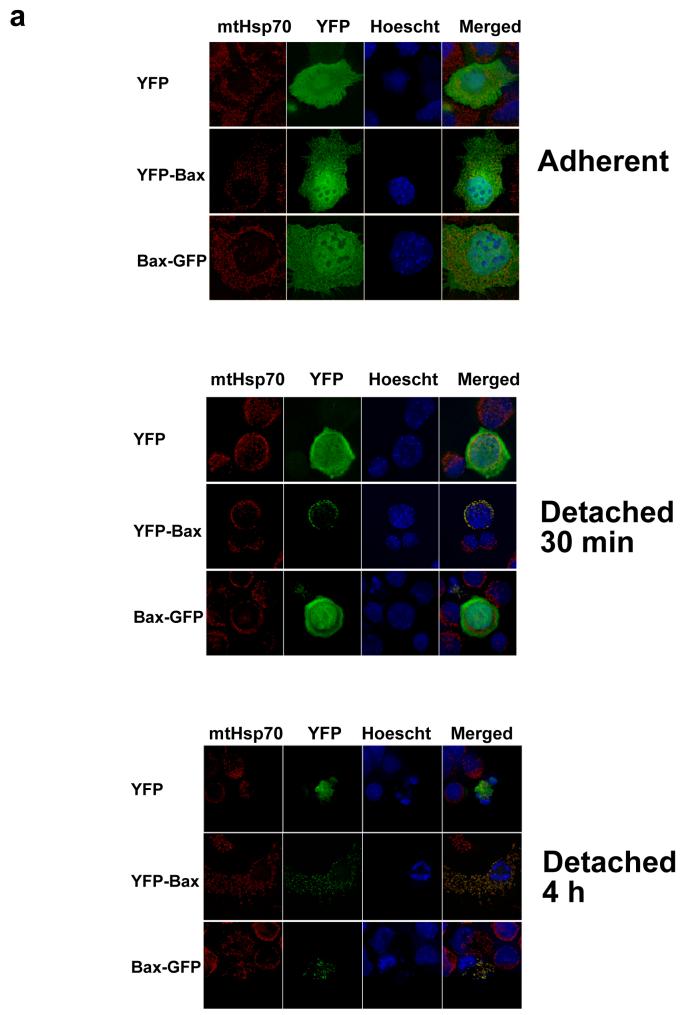

We next examined the distribution of YFP-Bax and Bax-GFP during anoikis in epithelial cells. Anoikis allows a temporal analysis of Bax recruitment and its subsequent activation (9, 24). YFP-Bax, Bax-GFP or YFP alone were transiently expressed in FSK-7 mammary epithelial cells, which were detached from extracellular matrix (ECM) for 30 minutes or 4 hours (Fig. 2a). In adherent cells, all three proteins were distributed throughout the cytoplasm. As we have previously shown, YFP-Bax redistributed to mitochondria within 30 minutes following loss of ECM contact, whereas YFP and Bax-GFP remained cytosolic. Interestingly, we observed that after 4 hours of detachment Bax-GFP demonstrated a punctate distribution similar to YFP-Bax, but only in those epithelial cells that had apoptotic nuclei. YFP remained cytosolic in apoptotic cells. To ascertain if Bax-GFP had any proapoptotic function in FSK-7 cells, we quantified apoptosis at various times following loss of ECM attachment (Fig. 2b). As previously demonstrated, over expression of YFP-Bax sensitised epithelial cells to anoikis. However, Bax-GFP expression did not sensitise FSK-7 cells to anoikis. Similar levels of expression for Bax-GFP and YFP-Bax were seen by immunoblotting (Fig. 2b). Substituting proline 168 to alanine (P168A) in the C-terminus of Bax prevents it targeting to the OMM and abrogates its apoptotic activity (23, 24). We asked if Bax-P168A could also redistribute to mitochondria in dead epithelial cells. FSK-7 cells expressing YFP, YFP-Bax, Bax-GFP or YFP-BaxP168A were detached from ECM for 4 hours. A punctate distribution was observed for all the Bax constructs in cells with apoptotic nuclei (Fig. 2c). As FSK-7 cells express endogenous Bax, it was possible that the recruitment of Bax-GFP and YFP-BaxP168A seen was dependent upon functional Bax being present.

Figure 2. Immunolocalisation of YFP-Bax and Bax-GFP during anoikis.

(a) Fsk-7 cells transiently expressing YFP, YFP-Bax or Bax-GFP, detached from ECM for various times, and their subcellular localisation assessed by immunofluorescence. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst and the mitochondria with mtHsp-70. Note the cytosolic distribution of all constructs in adherent cells. Note that after detachment for 30 minutes, only YFP-Bax has a punctate distribution that colocalised with mtHsp-70. Bax-GFP remains cytosolic and does not colocalise with mtHsp-70. After detachment for 4 hours, Bax-GFP localises to mitochondria in cells that have apoptotic nuclei. (b) Anoikis assay in Fsk-7 cells transiently expressing YFP, YFP-Bax, and Bax-GFP. Fsk-7 cells were left adherent or detached and maintained on polyHEMA for various times. Apoptosis was quantified by nuclear morphology. Only YFP-Bax sensitised cells to apoptosis. Data was compared by two-way ANOVA, with significant p-values indicated by *, and n/s denoting significant. Error bars show standard error of the mean, and the data represents three independent experiments. (c) Immunolocalisation of YFP, YFP-Bax, YFP-BaxP168A and Bax-GFP in transiently transfected Fsk-7 cells detached from the ECM for 4 hours.

Together, these data suggest that for Bax to promote apoptosis an exposed C-terminus is required. However, although Bax-GFP does not appear to posses any apoptotic activity, it can redistribute to mitochondria following epithelial cell death.

The N-terminus of Bax does not contain a mitochondrial targeting sequence

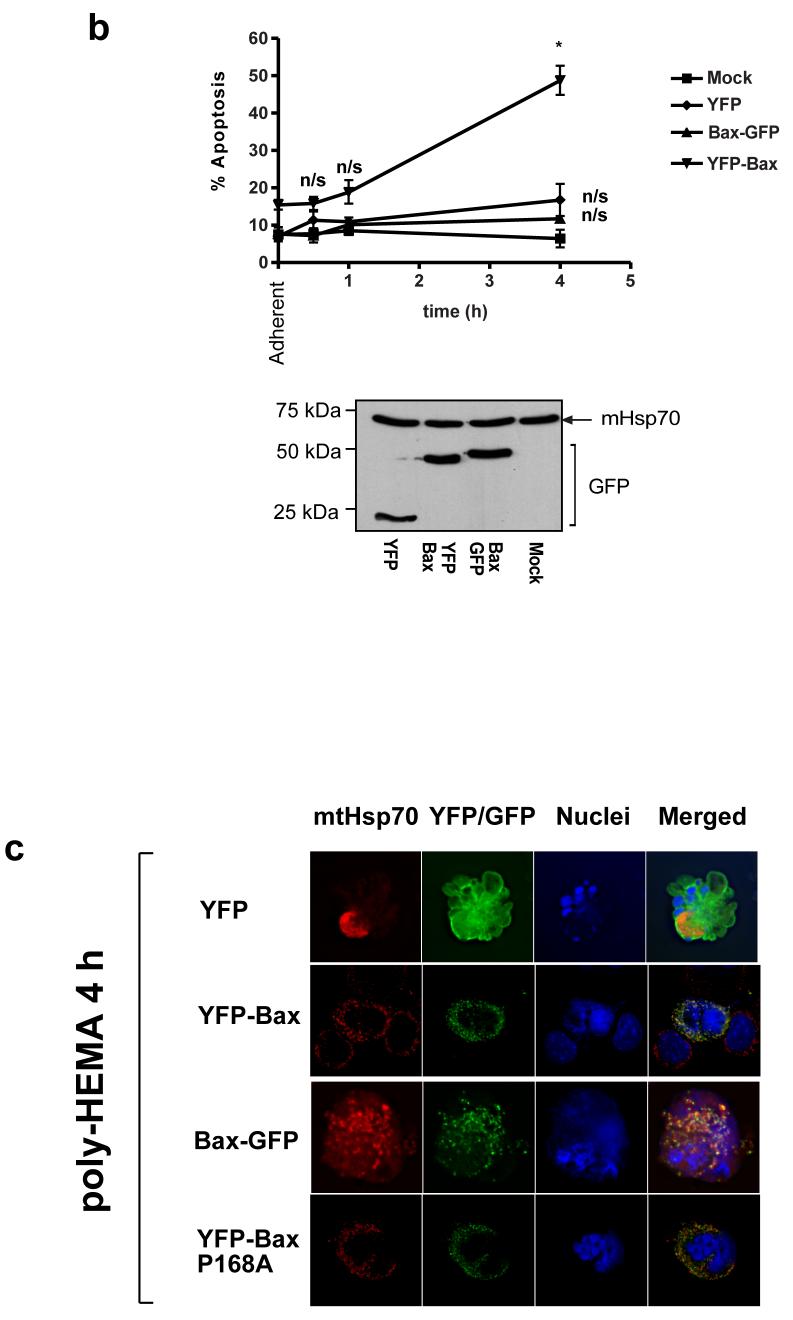

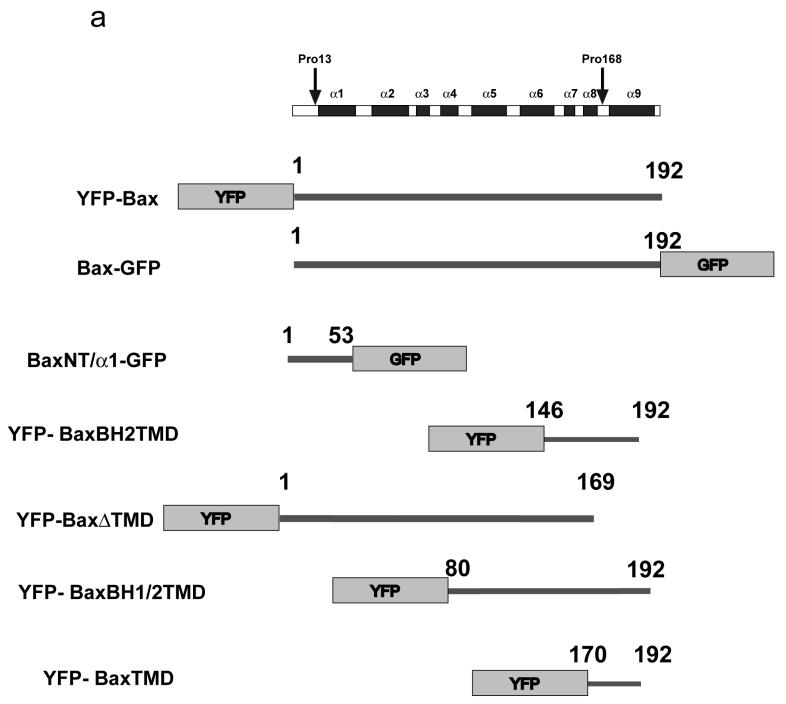

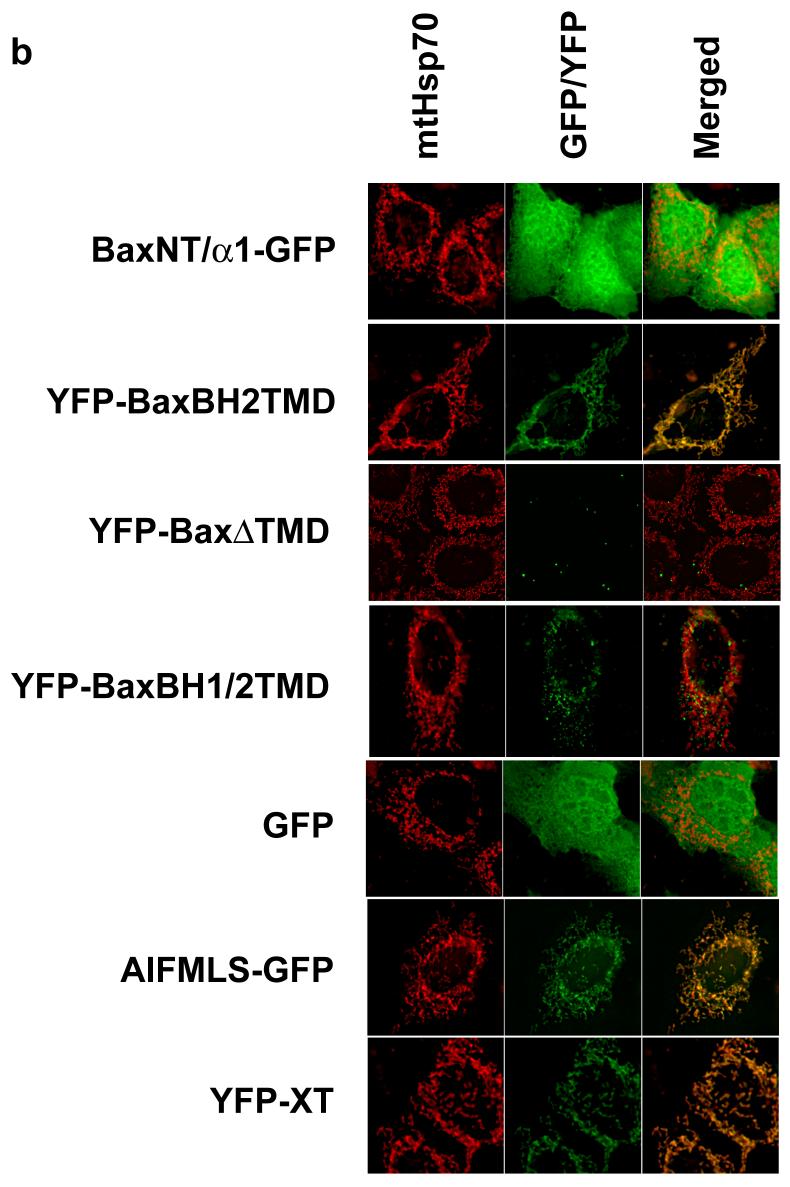

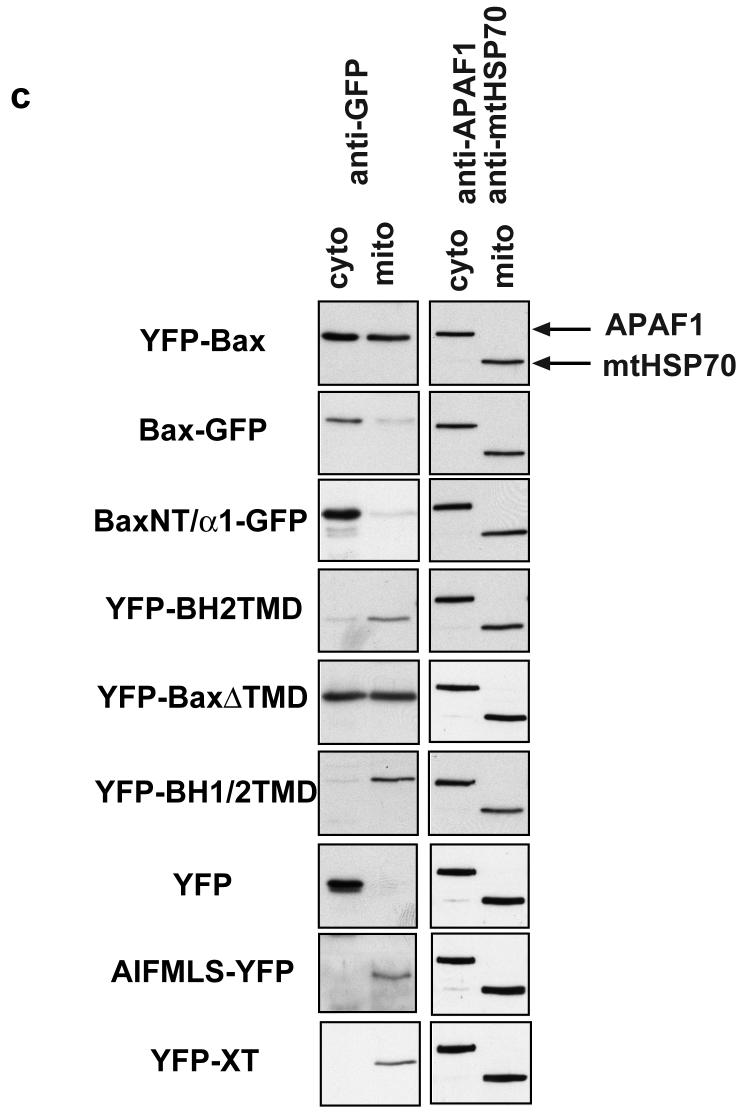

We designed a number of YFP/GFP constructs to directly test if the N- or C-termini of Bax contained mitochondrial-addressing sequences (Fig. 3a). As a control, a known N-terminal mitochondrial import sequence from Apoptosis Inducing Factor was fused to GFP (AIFMLS-GFP) (25). For a C-terminal anchor we used a previously described construct, YFP-XT, consisting of YFP fused to the C-terminal tail anchor of Bcl-XL(9). When transiently expressed in FSK-7 cells, both AIFMLS-GFP and YFP-XT colocalised with mtHsp70, whereas GFP alone was cytosolic (Fig. 3b). The construct consisting of the putative Bax tail anchor, YFP-BaxBH2TMD, colocalised perfectly with mtHsp70. In contrast, BaxNT/α1-GFP, containing the suggested N-terminal signal sequence, was distributed throughout the cytosol. YFP-BaxΔTMD, with the tail anchor deleted, formed large aggregates that did not associate with mitochondria. YFP-BaxBH1/2TMD, which contains the tail anchor but also the central hydrophobic α5-helix, formed aggregates that resembled the clusters of Bax found associated with mitochondria in apoptotic cells.

Figure 3. The N-terminus of Bax does not possess a mitochondrial addressing signal.

(a) Schematic representation of Bax and its helical domains. Arrows indicate the proline residues (13 and 168) that were mutated to alanine. Also shown are the various truncated forms of Bax, tagged with either YFP or GFP, that were generated to address the relative contribution of the N- and C- terminus to targeting. Numbers indicate the amino acids included in each. (b) Several YFP and GFP constructs were engineered to assess the contribution of the N-terminus of Bax to mitochondrial targeting. As control, a known N-terminal import sequence of apoptosis inducing factor (AIFMLS) was fused to GFP. The C-terminus of Bcl-XL was fused to YFP as a control for C-terminal directed targeting (YFP-XT). Truncated forms of Bax were generated: the α1helix alone (BaxNTα1-GFP), Bax with only the BH2 and transmembrane domains (YFP-BaxBH2/TMD), Bax minus the TMD (YFP-BaxΔTMD) and Bax comprising the BH1, BH2 and TMD (YFP-BaxBH1/2/TMD). Fsk-7 cells were grown on coverslips, transiently transfected and immunostained for mtHsp-70. (c) Subcellular localisation of the various YFP-and GFP-tagged proteins. Fsk-7 cells transiently transfected with the tagged proteins were subfractionated into a cytosolic and a crude mitochondrial fraction. Protein lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for GFP. Fractionation was checked by immunoblotting for the cytosolic marker (APAF-1) and the mitochondrial marker (mtHsp-70). (d) Fsk-7 cells were transiently transfected with various tagged proteins and then subfractionated into cytosol and a crude mitochondrial fraction. The isolated mitochondrial fraction was extracted with 0.1M sodium carbonate and the soluble fraction (carbonate-sensitive) separated from the insoluble (carbonate-resistant) fraction. All fractions, including an aliquot representing total, were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for GFP.

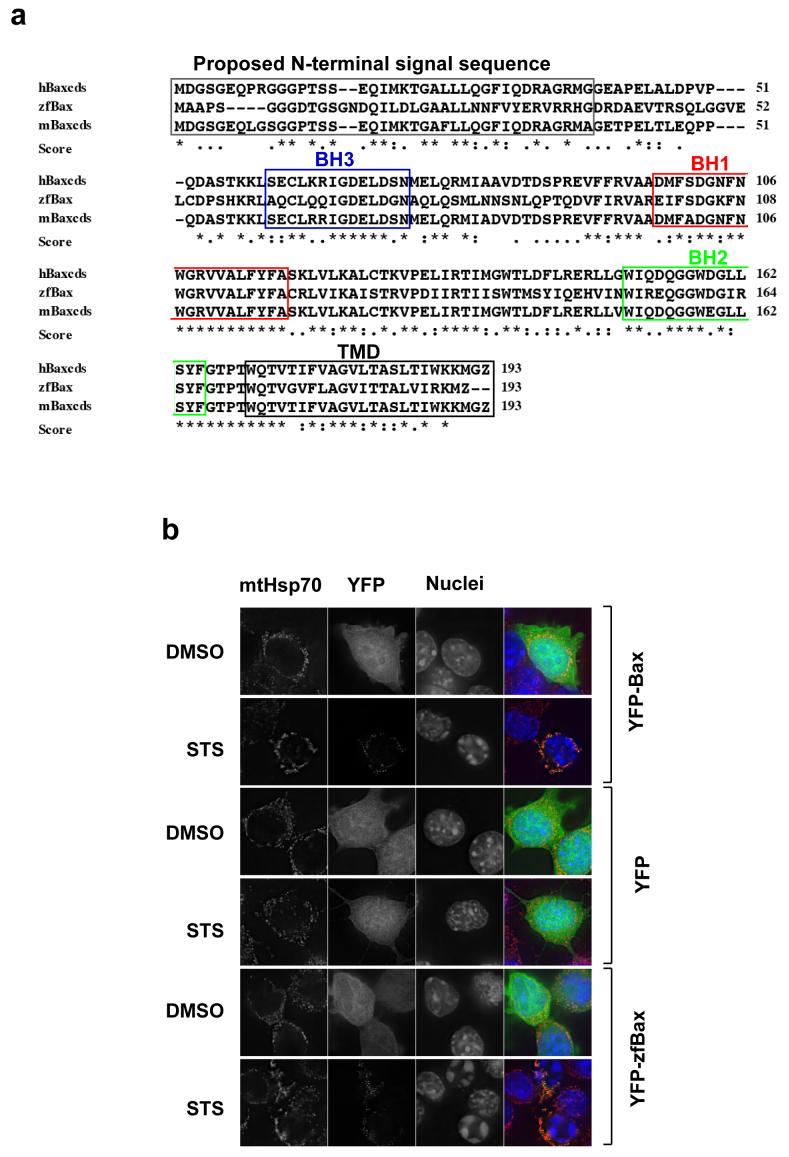

We also examined the distribution of these deletion mutants by biochemical fractionation (Fig. 3c). Cells expressing the indicated constructs were separated into soluble and heavy membrane fractions, and analysed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for GFP, APAF-1 (cytosolic marker) and mtHsp70. All the constructs that co-localised with mtHsp70 by fluorescence were found in the membrane fraction. Both YFP alone and BaxNT/α1-GFP were exclusively cytosolic. YFP-Bax was distributed between both fractions. The two constructs that formed aggregates (YFP-BaxΔTMD and YFP-BaxBH1/2TMD) were detected in the heavy membrane fraction, indicating that biochemical fractionation alone is insufficient to determine if a protein targets to mitochondria. To determine if the Bax constructs inserted into the membrane, heavy membrane fractions were extracted in carbonate buffer (Fig. 3d). The cytosolic (supernatant) along with the carbonate sensitive and carbonate resistant membrane fractions were immunoblotted. All the YFP-Bax constructs that were associated with the membrane fraction in FSK-7 cells were resistant to carbonate extraction.

Together, these data indicate that the C-terminus of Bax is necessary and sufficient for mitochondrial targeting. In contrast, our data indicates that the N-terminus of Bax does not contain a mitochondrial targeting sequence.

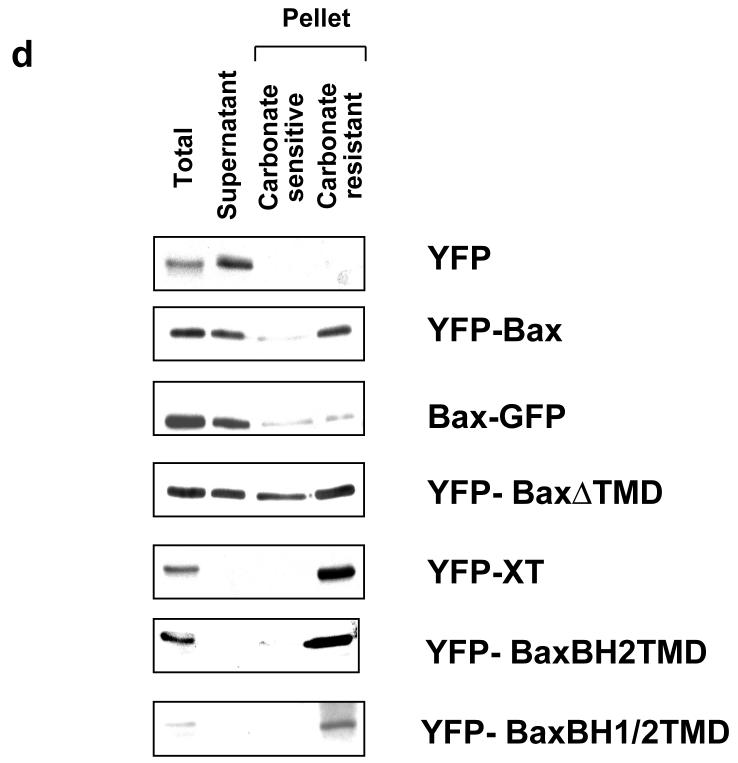

Zebrafish Bax targets to mitochondria in mammalian cells despite a divergent N-terminal sequence

Regions of sequence conservation between protein homologues from distant species can highlight functional domains. The zebrafish genome contains homologues of most Bcl-2 family proteins (26). We noted that zebrafish Bax (zfBax) showed localised regions of sequence identity with mammalian Bax (Fig. 4a). In particular, zfBax showed strong sequence identity at the C-terminus, but not at the N-terminus. Given the similarity in the C-termini, we asked if zfBax could function in mammalian cells.

Figure 4. Zebra fish Bax (zfBax) localises to mammalian mitochondria despite a divergent N-terminal sequence.

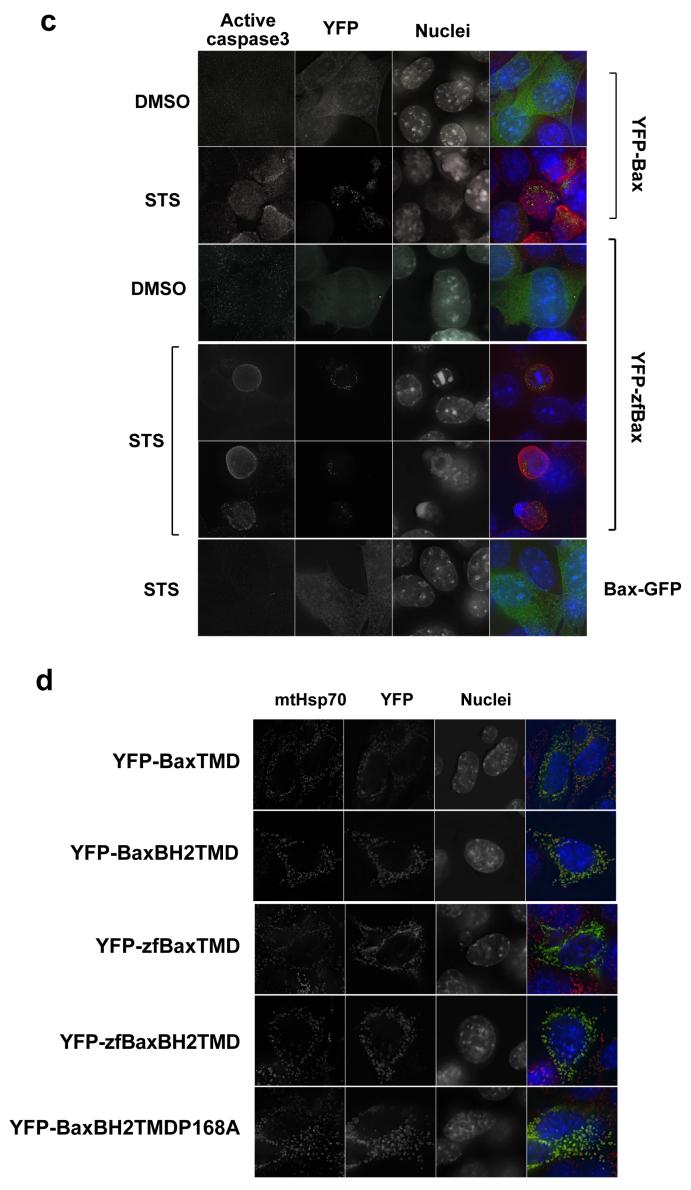

(a) Comparison of the amino acid sequence of zebra fish Bax with mouse Bax. Note the high degree of homology of zebra fish Bax with mouse Bax at the C-terminus. (b) DKO cells were transiently transfected with YFP-zfBax, YFP-Bax and YFP and then treated with vehicle alone or 10um staurosporine after which they were immunostained for mtHsp-70. (c) DKO cells were transiently transfected with YFP-Bax, YFP-zfBax, and Bax-GFP were treated with vehicle alone or 10um staurosporine after which they were immunostained for active caspase 3 (d) DKO cells transiently expressing YFP-Bax fusions containing the BH2TMD and TMD regions of mouse and zfBax were immunostained for mtHsp70.

YFP-zfBax, YFP-Bax or YFP were expressed transiently in DKO MEFs. These were treated with either DMSO or staurosporine. YFP-zfBax was cytosolic in DMSO treated cells but became punctate following treatment with staurosporine, and was indistinguishable from murine YFP-Bax (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, zfBax rescued the apoptosis defect in the DKO cells, shown by the apoptotic nuclei in the cells following staurosporine treatment (Fig. 4b), and the presence of activated caspase 3 (Fig. 4c)

Given the sequence similarity with mammalian Bax, we asked if the C-terminus of zfBax was a mitochondrial anchor sequence. The transmembrane region (TMD) and the BH2/TMD sequence of zfBax were expressed as YFP fusions in DKO MEFs, as well as the equivalent mouse sequences. Cells were immunostained for mtHsp70 (Fig. 4d). The subcellular distribution of the zfBax C-terminus was indistinguishable from the mouse constructs, showing constitutive co-localisation with mitochondria. These data support the hypothesis that Bax from distant vertebrate species contains a conserved C-terminal tail anchor. We also expressed YFP-BaxBH2TMD containing the P168A mutation shown to block the association of full length Bax with mitochondria. In agreement with previous data that indicated that this proline lies outside the tail anchor, YFP-BaxBH2TMDP168A constitutively localised to the OMM.

The Bax C-terminal anchor forms complexes following translocation to mitochondria

To determine if Bax oligomerisation had a role in mitochondrial targeting, we used two-dimensional Blue Native PAGE (2D BN-PAGE). 2D BN-PAGE analysis of endogenous Bax indicated that in adherent cells, the cytosolic protein was exclusively monomeric (Fig. 5a). Following detachment, mitochondrial Bax was found in a high molecular weight complex of approximately 200 kDa. YFP-Bax was found in high molecular weight complexes identical in size to endogenous Bax (Fig. 5b). YFP alone analysed by BN-PAGE was monomeric.

Figure 5. Bax resides in a 200Kd complex following detachment from the ECM.

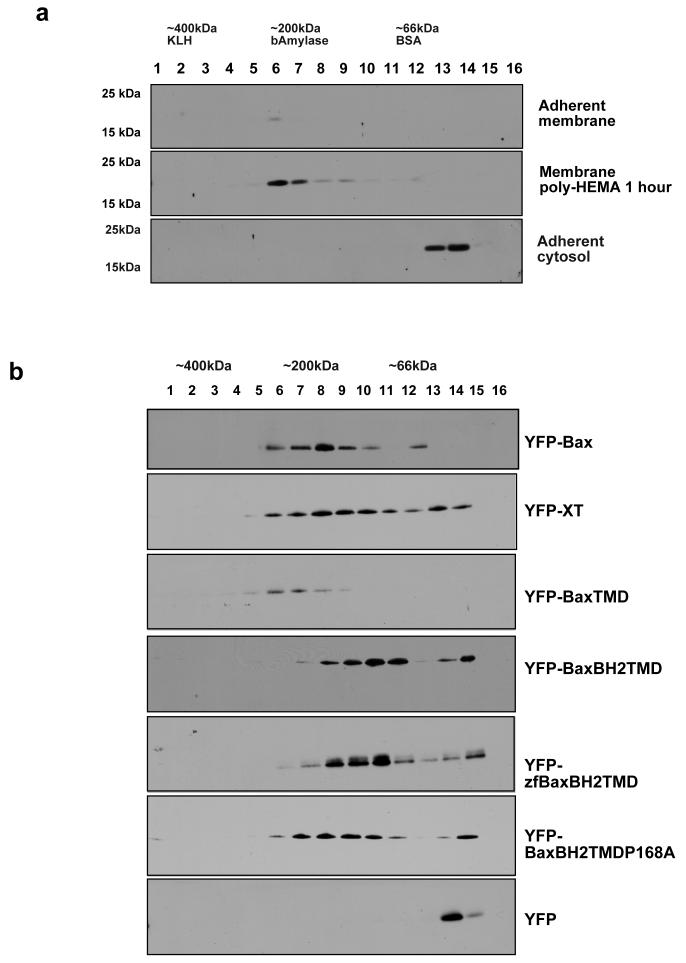

(a) Crude mitochondria from adherent and detached Fsk-7 cells were analysed by 3-15% BN-PAGE following solubilisation in 1% CHAPS, 0.5M aminocaproic acid. Lanes (40ug protein/lane) from BN-PAGE were cut into 16 small pieces and each piece boiled in SDS sample buffer. Endogenous Bax was detected by immunoblotting with antibody 5B7. (b) The mitochondrial fraction from transiently transfected 293T cells expressing the indicated YFP-Bax constructs were isolated and subjected BN-PAGE as in (a).

C-terminal anchor proteins may be targeted to mitochondria and the ER through interactions with chaperone proteins or receptors (12), and may also oligomerises within the membrane (27). To ask if the tail anchor of Bax interacted with chaperones, we examined the native molecular weights of the Bax C-terminal YFP fusions. YFP-XT, YFP-BaxTMD, YFP-BaxBH2TMD, and YFP-zfBaxBH2TMD were expressed in 293T cells, mitochondria isolated and analysed by BN-PAGE. Intriguingly, the YFP-Bax tail anchor constructs also appeared to associate with high molecular weight complexes on mitochondria, as did YFP-XT. YFP-BaxBH2TMDP168A migrated in an identical manner as the other BaxBH2TMD constructs. Thus, Proline 168 does not itself constitute part of the tail anchor and can only regulate its function in the context of full-length Bax. These data indicate that the minimal tail anchor sequences of Bax and Bcl-XL may interact with other proteins on mitochondria. Indeed, Bcl-XL has been shown to form dimers, both with itself and with Bax, via its C-terminal domain (28).

Tail anchor independent amplification of Bax targeting to mitochondria

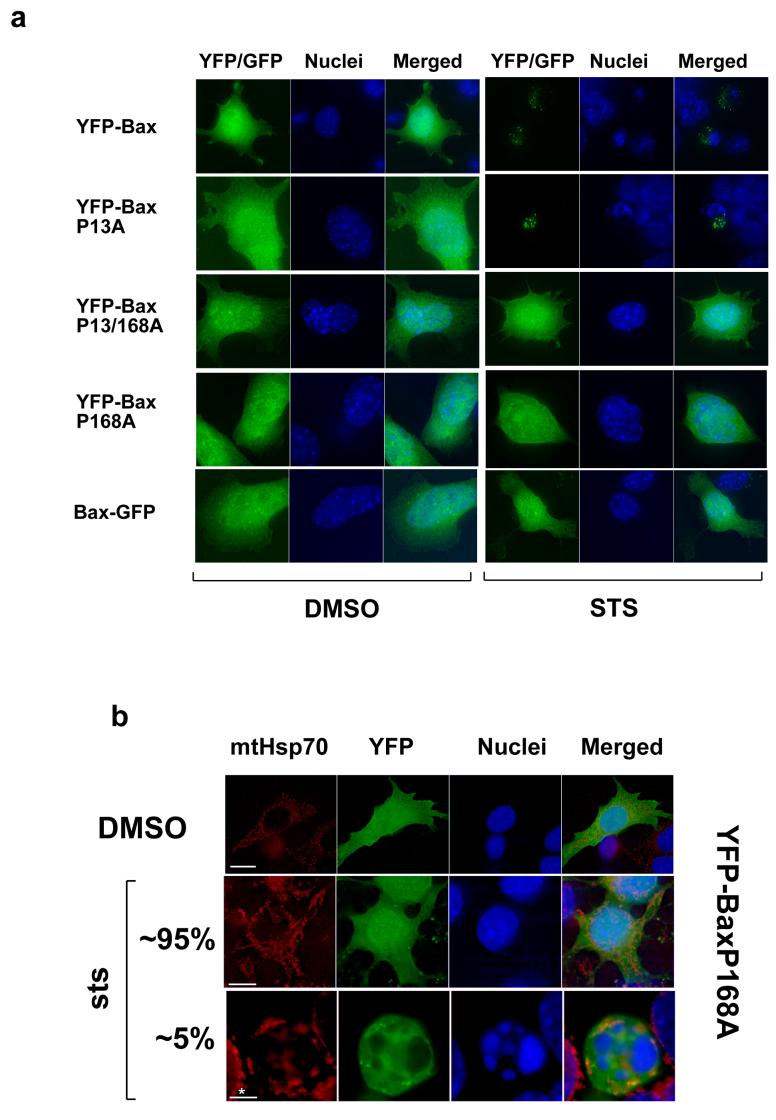

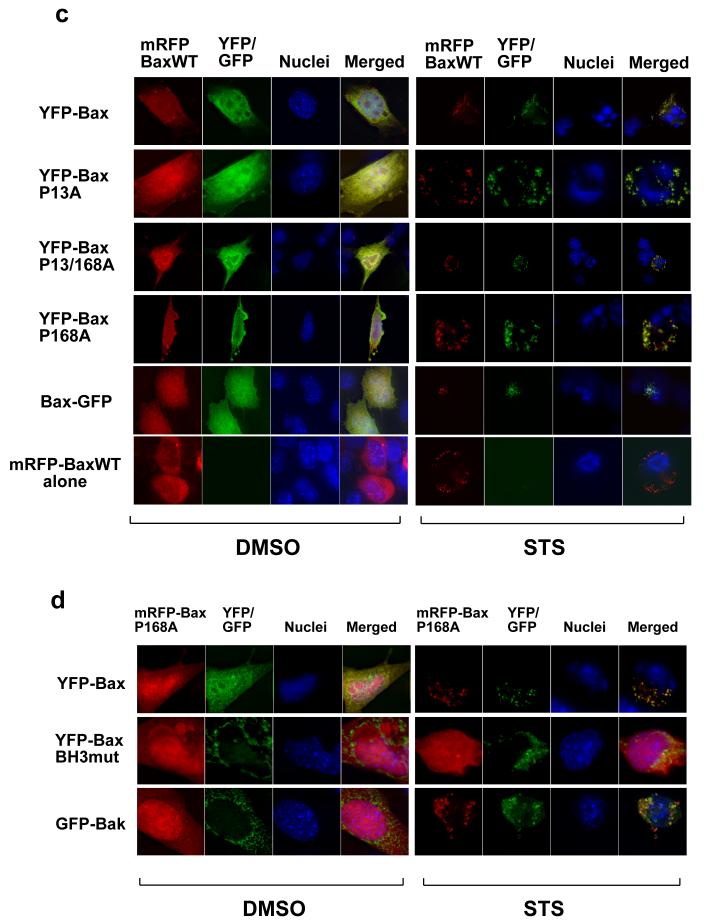

Bax forms large aggregates on mitochondria during apoptosis (29). Mutants of Bax that cannot target to mitochondria or initiate apoptosis in DKO cells were still recruited to these clusters on the OMM in FSK-7 cells, which express endogenous Bax and Bak. We hypothesised that targeting of non-functional Bax mutants to mitochondria was due to endogenous Bax on the mitochondria. To test this we expressed in DKO cells YFP-Bax, Bax-GFP, YFP-BaxP13A, YFP-BaxP168A or the double mutant YFP-BaxP13/168A. We have shown the proline 13 to alanine substitution to accelerate Bax dependent MOMP following mitochondrial translocation. However, Cartron et al. have suggested that the same mutation exposes the proposed N-terminal targeting-sequence, resulting in constitutive mitochondrial association (17, 19). Cells were treated with either DMSO or staurosporine for 2 hours (Fig. 6a). As previously reported, both YFP-Bax and YFP-BaxP13A induced apoptosis and formed punctate clusters in DKO cells (24). YFP-BaxP168A and Bax-GFP remained cytosolic following staurosporine treatment. Some DKO cells do undergo apoptosis (approximately 5%), presumably through a mitochondrial independent mechanism. Even in those DKO cells with apoptotic nuclei, YFP-BaxP168A remained cytosolic (Fig. 6b). In agreement with our previous findings, YFP-BaxP13/168A also remained cytosolic (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6. Reintroducing WT-Bax into DKO recruits target-defective forms of Bax to the mitochondria during apoptosis.

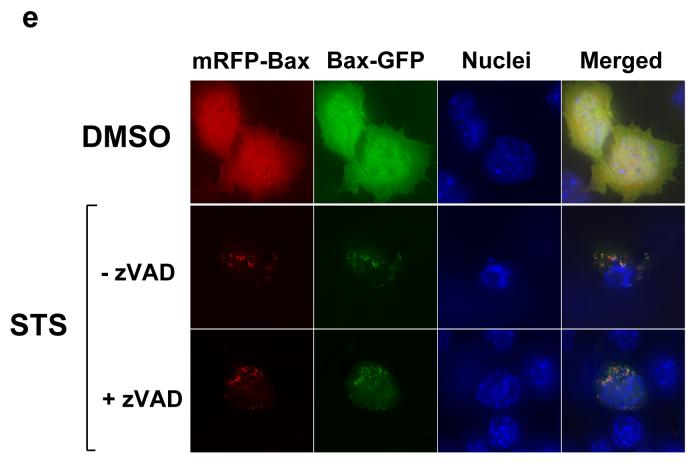

(a) DKO cells transiently expressing YFP-Bax, YFP-P13ABax, YFP-P168ABax or YFP-P13/168ABax were treated with vehicle (DMSO) alone (top) or 10um Staurosporine for 4 hours (STS). (b) Immunolocalisation of YFP-BaxP168A in DKO in control and STS-treated cells. The relative percentage of cells with an apoptotic nuclear morphology versus healthy nucleus is shown. (c) DKO cells transiently co-expressing mRFP-Bax with either YFP-Bax, YFP-BaxP13A, YFP-Bax168A or YFP-BaxP13/168A were treated with vehicle (DMSO) alone or 10um STS for four hours. Cells expressing just mRFP-Bax alone did not show any signal in the YFP channel (d) DKO cells transiently co-expressing mRFP-BaxP168A with either YFP-Bax, YFP-BaxBH3mut, GFP-Bak were treated with vehicle (DMSO) alone or 10um STS for four hours. (e) DKO cells transiently co-expressing Bax-GFP or with either YFP-BaxP168A, along with either mRFP or mRFP-BaxWT were treated with vehicle (DMSO) alone or 10um STS for four hours, in the presence or absence of zVADfmk.

Next, we co-expressed each of Bax-GFP, YFP-Bax, YFP-BaxP13A, YFP-BaxP168A or YFP-BaxP13/168A along with mRFP-Bax wildtype (WT). mRFP-BaxWT restored DKO sensitivity to apoptosis in an identical manner to YFP-Bax (data not shown). Cells were treated with DMSO or staurosporine for 4 hours and the distribution of YFP and mRFP compared (Fig. 6c). In DMSO treated cells, the YFP-Bax mutants and mRFPBaxWT were all cytosolic. Staurosporine treatment in DKO cells resulted in recruitment of Bax-GFP, YFP-BaxP168A and YFP-BaxP13/168A to mitochondria in cells expressing mRFP-BaxWT. As in FSK-7 cells undergoing anoikis, recruitment of either P168A Bax mutant was only observed in cells that had apoptotic nuclei. We repeated the experiment with mRFP-BaxP168A co-expressed with either GFP-Bak, or YFP-Bax containing a non-functional BH3-domain (YFP-BaxBH3mut, L63E/G67E). YFP-BaxBH3mut constitutively targets to mitochondria, but cannot induce cytochrome c release (our unpublished data). Following staurosporine treatment, GFP-Bak recruited mRFPBaxP168A, whereas YFP-BaxBH3mut did not (Fig. 6d).

Finally, we asked if the recruitment of non-functional Bax was downstream of caspase activation. DKO cells co-expressing Bax-GFP and mRFP-BaxWT were treated with DMSO or staurosporine, in the presence of absence of zVAD-fmk. Bax-GFP was recruited to mitochondria in mRFP-Bax expressing cells even if caspase activity had been inhibited (Fig. 6e).

Together, these data indicate that Bax mutants that are defective for mitochondrial targeting are still recruited to mitochondrial clusters during apoptosis.

Discussion

Bax translocation during apoptosis is essentially a problem of mitochondrial targeting. Most mitochondrial proteins are translated in the cytosol and imported into the correct mitochondrial compartment via a number of mechanisms (11, 12). The mechanism utilised by Bax remains controversial, with conflicting data indicating an N-terminal pre-sequence or a C-terminal tail anchor. In this paper we show that Bax is initially targeted to the OMM by a C-terminal tail anchor, and exclude an N-terminal pre-sequence. Tail anchor mediated targeting of Bax is essential for its function. Subsequently, Bax aggregates form through recruitment and activation of further Bax molecules from the cytosol, which does not require a functional tail anchor. Instead, this second wave requires functional, multi-domain pro-apoptotic proteins on the OMM. Bax or Bak were both capable of recruiting cytosolic Bax during this second wave of targeting.

Most multi-domain Bcl-2 proteins have functional tail anchor sequences (15), however Tremblais and co-workers have claimed that Bax does not (20). By replacing the tail anchor sequence of Bcl-XL with the C-terminal 20 amino acids of Bax, they showed that the resulting chimera did not target mitochondria. A crucial point for tail anchor function is the amount of sequence N-terminal to the transmembrane domain (14). Although Bax does not have basic residues in that position, this flanking sequence is still important. Schinzel et al. indicated that a minimum 23 amino acids of the Bax C-terminus is required to target a heterologous protein to mitochondria (23). When they expressed either a 22 or 21 amino acid GFP-BaxTMD chimeras, the protein remained cytosolic. We show that not only can the C-terminus of Bax target YFP to mitochondria, but it can also forms protein complexes on the OMM similar in size to those containing full-length Bax.

Another argument put forward for the absence of a tail anchor in Bax was that deletion of the C-terminal 22 amino acids did not block recruitment to mitochondria during apoptosis (19). This can be explained by the amplification of Bax activation we report. Functional Bax or Bak on mitochondria can drive further Bax recruitment from the cytosol using a mechanism separate from the initial tail-anchor dependent targeting. Amplification occurs either during or after MOMP, as we observed punctate Bax-GFP and YFP-BaxP168A only in cells with apoptotic nuclei. Amplification of Bax and Bak activation has previously been shown in vitro (30, 31). Activated Bax on liposomes induced further activation and recruitment of soluble Bax. Taking these studies together, the data suggest that once activation of mitochondrial Bax or Bak has exceeded a certain threshold, it induces a chain reaction of further Bax activation that may irreversibly drive MOMP.

It has been proposed that Bax possesses an N-terminal signal sequence (18). These sequences target proteins to mitochondria via the TOM/TIM general import pore (GIP). The proposed import sequence does not reside at the extreme N-terminus of Bax, but becomes exposed if the first 20 amino acids are removed. In most cases proteolysis of Bax does not occur during translocation to mitochondria. Also, if the targeting sequence were contained within the N-terminus, Bax-GFP might be expected to restore sensitivity to staurosporine to DKO cells. Bax-GFP was unable to rescue apoptosis in DKO cells, whilst YFP-Bax did, suggesting that a native C-terminus is essential, whereas an exposed N-terminus is not. Neither the N-terminus of mammalian Bax or zfBax is predicted to contain a mitochondrial import sequence when analysed by MitoProt (unpublished observations). Furthermore, the N-terminus of Bax had no ability at all to target GFP to mitochondria. Thus, our data does not support the presence of an N-terminal import sequence.

Tail-anchored proteins differ from N-terminal directed membrane proteins in that targeting must occur following detachment from the ribosome. This post-translational insertion has been shown to require chaperone proteins to mask the hydrophobic TMD in the cytosol (32, 33). Unlike most known tail-anchored proteins, Bax is not constitutively targeted to the OMM, instead translocating in response to apoptotic stimuli. The solution structure of monomeric Bax indicates that α-helix 9, the TMD of the tail anchor, lies hidden within a hydrophobic groove on the proteins surface. Thus, Bax may function as its own chaperone. Youle and co-workers found that different mutations within the C-terminal α-helix could either inhibit Bax targeting or induce it (22). Furthermore, mutating proline 168, immediately upstream of the tail anchor prevented Bax translocation during both staurosporine induced cell death and anoikis and abolished its apoptotic activity (23, 24). A model developed with mitochondrial targeting of Bax occurring when an activated BH3-only protein, such as tBid, induced reorientation of the TA from the surface groove, with proline 168 at the hinge, exposing it. However, the NMR structure indicates that the energy required to release the hydrophobic tail into an aqueous environment is too great to be explained by the proposed Bax/tBid BH3-domain interaction(34). Another scenario is that the tail anchor unfolds when in close proximity to a lipid bilayer. Thus, Bax targeting may occur prior to TMD reorientation, and may require mitochondrial receptors. Mitochondrial proteins are required for Bax to oligomersie in mitochondria, but not in synthetic liposomes (35, 36), and two recent reports identify interactions between Bax and TOM proteins (21, 37). A study utilising mitochondria from yeast that were either treated with proteases to remove the GIP, or which were derived from mutants for various TOM proteins, indicated that a functional GIP was not required for Bax dependent MOMP (38). However, another study using similar yeast mutants came to the opposite conclusion, and loss of functional Tom40 or Tom22 inhibited Bax induced cytochrome c release (37). A role for TOM proteins does not exclude a C-terminal anchor, as an amphipathic helix at either end can direct a protein to the GIP receptors. Hmi1p, a DNA helicase, has a C-terminal sequence that directs it into the mitochondrial matrix via the GIP. It remains to be seen if Bax is targeted via a receptor, but a recent study examining a variety of mitochondrial tail anchor proteins concluded that they utilised a common mechanism (39). Bax targeting does not differ fundamentally from other tail anchor proteins. How the Bax tail anchor is activated following an apoptotic signal, however, remains the central question in the regulation of this protein.

Materials and Methods

Cells

Fsk-7 mouse mammary epithelial cells were cultured as previously described (9, 24). SV40 transformed bax-/- /bak-/- mouse embryonic fibroblasts (DKO MEFs) were kindly provided by Nika Danial (Dana Faber, Boston), and were grown as described (2). Human embryonic kidney 293T cells were cultured in Dulbeccos modified Eagle’s medium with 10% foetal bovine serum.

Plasmids and transfections

YFP-Bax and mRFP-Bax have been previously described (9, 24). Bax deletion mutants were generated using PCR amplification with Pfu polymerase (Promega), and were ligated into pEYFP-C1 or pEGFP-N1. All mutations were confirmed by sequencing. Cells were plated onto coverslips or 60 mm dishes at 80% confluence and transfected as previously described (9). After 24 hours cells were harvested for either immunoblotting, anoikis assays, live cell imaging or immunofluorescence.

Cell fractionation and sodium carbonate extraction

Cells were grown on 100 mm plates until ∼ 80% confluent and then transfected with 3.0 μg plasmid using Lipofectamine Plus (Invitrogen) as described by the manufacturer. 18hr post-transfection cells treated with Staurosporine (10 μm) or vehicle alone (DMSO) for 2-4 hrs and were then sub fractionated. Adherent cells were scraped into hypotonic lysis buffer (10mM Tris.Cl, pH 7.5, 10mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2) containing protease inhibitors and allowed to swell on ice for 10 min prior to homogenising with a glass dounce homogeniser. MS buffer (2.5X; 525 mM mannitol, 175mM sucrose, 12.5 mM Tris.Cl, pH 7.5, 2.5 mM EDTA) was added to 1X. The homogenates were centrifuged at 1300g for 10 min at 4°C to pellet nuclei and unbroken cells. The supernatant was centrifuged as before and the subsequent supernatant at 17000g (S17) for 15 min at 4°C to obtain the mitochondrial pellet (P17). The S17 was centrifuged at 100,000g for 30 min at 4°C to produce the cytosolic fraction. The P17 fraction was then washed once with 1X MS buffer and then solubilised in 0.1M Na2CO3 for 30 min on ice. After centrifugation at 100,000g for 30 min at 4°C, the supernatant (alkali-soluble fraction) was titrated to neutral pH with HCl. The pellet (alkali-resistant fraction) was solubilised in SDS sample buffer. The presence of YFP-tagged proteins was detected by immunoblotting for GFP.

Blue native (BN)-PAGE

Blue native (BN)-PAGE was carried out essentially as described by Brookes et al.(40). Crude mitochondrial fractions were prepared and membrane proteins extracted in 1% CHAPS, 10% glycerol, 0.5 M aminocaproic acid in 50 mM Bis/Tris, pH 7.0. The 1st dimension BN-PAGE was then resolved in the 2nd dimension by conventional SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted.

Antibodies and Immunoblotting

Protein from subcellular fractions, transfections, cross-linking reactions and sodium carbonate extractions were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose and then subjected to immunoblotting. Polyclonal anti-Bax NT (06-499) was from Upstate Biotechnology. Anti-active caspase 3 was from R&D systems. Polyclonal anti-GFP (A11122) was from Molecular Probes. Monoclonal mtHsp 70 (MA3-028) was from Affinity Bioreagents. Anti-APAF-1 (AAP-300) was from Stressgen. Following 1° antibody incubation, detection was performed using peroxidase conjugated 2° antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and chemiluminesence (Pierce).

Immunofluorescence and imaging

Anoikis was induced in FSK-7 cells by trypsinising them and plating them onto dishes coated with polyhydroxyethylmethacrylate (poly-HEMA) in complete growth media. To image detached FSK-7 cells, they were cytospun onto polysine slides as previously described (9). Apoptosis was induced in DKO MEFs via treatment with 10μM staurosporine (Calbiochem) in DMSO for the time indicated. Cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS and permeabilised with 0.5% Triton X-100/PBS. 1° antibodies were incubated in PBS/0.1% Triton-X100/0.1% horse serum (1 hour, 37°C). Following washing in PBS, 2° goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit Cy5, Cy2 or RhodamineRx conjugates were incubated in above buffer (30 minutes, 37°C). Where indicated, nuclei were stained with 1 μg/ml Hoechst 33258. Images were collected on an Olympus microscope, equipped with a Deltavision imaging system, using a 100 × PLAN-APO 1.4NA objective. Images were processed by constrained iterative deconvolution using softWoRx™ (Applied Precision). Apoptosis was quantified by assessing nuclear morphology in transfected cells using an Axioplan2 microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.). Transfected cells were identified by YFP or mRFP-fluorescence, and nuclear morphology assessed following staining with Hoechst. For each time point, approximately 300 cells were counted, and each experiment was performed in troplicate. Time course apoptosis assays were analysed with two-way ANOVA with Bonferronis post-test to obtain p values, using Prism 4 software (GraphPad).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust. J-PU was supported by a studentship from the BBSRC. The authors thank Fiona Foster and Thomas Owens for comments on the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- APAF-1

apopotic protease activating factor 1

- BN-PAGE

blue native polyacrylamide electrophoresis

- DKO

double knock out

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GIP

general import pore

- IMS

inter-membrane space

- IMM

inner mitochondrial membrane

- MOMP

mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilisation

- mRFP

monomeric red fluorescent protein

- mtHsp70

mitochondrial heat shock protein 70

- OMM

outer mitochondrial membrane

- poly-HEMA

poly-2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate

- SMAC

second mitochondrial activator of caspases

- TA

tail anchor

- TIM

translocase inner membrane

- TMD

transmembrane domain

- TOM

translocase outer membane

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein

- zVADfmk

benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp-fluoromethane.

References

- 1.Cory S, Adams JM. The Bcl2 family: regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:647–656. doi: 10.1038/nrc883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, Lindsten T, Panoutsakopoulou V, Ross AJ, et al. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001;292:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilmore AP, Metcalfe AM, Romer LH, Streuli CH. Integrin-mediated survival signals regulate the apoptotic function of Bax through its conformation and subcellular localization. J. Cell Biol. 2000;149:431–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.2.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goping IS, Gross A, Lavoie JN, Nguyen M, Jemmerson R, Roth K, et al. Regulated targeting of BAX to mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 1998;143:207–215. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonsson B, Montessuit S, Sanchez B, Martinou JC. Bax is present as a high molecular weight oligomer/complex in the mitochondrial membrane of apoptotic cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11615–11623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desagher S, Osen Sand A, Nichols A, Eskes R, Montessuit S, Lauper S, et al. Bid-induced conformational change of Bax is responsible for mitochondrial cytochrome c release during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:891–901. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.5.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eskes R, Desagher S, Antonsson B, Martinou JC. Bid induces the oligomerization and insertion of Bax into the outer mitochondrial membrane. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:929–935. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.929-935.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu YT, Wolter KG, Youle RJ. Cytosol-to-membrane redistribution of Bax and Bcl-X(L) during apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3668–3672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valentijn AJ, Metcalfe AD, Kott J, Streuli CH, Gilmore AP. Spatial and temporal changes in Bax subcellular localization during anoikis. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:599–612. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolter KG, Hsu YT, Smith CL, Nechushtan A, Xi XG, Youle RJ. Movement of Bax from the cytosol to mitochondria during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1281–1292. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.5.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfanner N, Geissler A. Versatility of the mitochondrial protein import machinery. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:339–349. doi: 10.1038/35073006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borgese N, Brambillasca S, Colombo S. How tails guide tail-anchored proteins to their destinations. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horie C, Suzuki H, Sakaguchi M, Mihara K. Characterization of signal that directs C-tail-anchored proteins to mammalian mitochondrial outer membrane. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1615–1625. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-12-0570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufmann T, Schlipf S, Sanz J, Neubert K, Stein R, Borner C. Characterization of the signal that directs Bcl-x(L), but not Bcl-2, to the mitochondrial outer membrane. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:53–64. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schinzel A, Kaufmann T, Borner C. Bcl-2 family members: intracellular targeting, membrane-insertion, and changes in subcellular localization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1644:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oltvai ZN, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 heterodimerizes in vivo with a conserved homolog, Bax, that accelerates programmed cell death. Cell. 1993;74:609–619. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90509-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cartron PF, Arokium H, Oliver L, Meflah K, Manon S, Vallette FM. Distinct domains control the addressing and the insertion of Bax into mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10587–10598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cartron PF, Priault M, Oliver L, Meflah K, Manon S, Vallette FM. The N-terminal end of Bax contains a mitochondrial-targeting signal. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11633–11641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cartron PF, Moreau C, Oliver L, Mayat E, Meflah K, Vallette FM. Involvement of the N-terminus of Bax in its intracellular localization and function. FEBS Lett. 2002;512:95–100. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tremblais K, Oliver L, Juin P, Le Cabellec TM, Meflah K, Vallette FM. The C-terminus of bax is not a membrane addressing/anchoring signal. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:582–591. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellot G, Cartron PF, Er E, Oliver L, Juin P, Armstrong LC, et al. TOM22, a core component of the mitochondria outer membrane protein translocation pore, is a mitochondrial receptor for the proapoptotic protein Bax. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:785–794. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nechushtan A, Smith CL, Hsu YT, Youle RJ. Conformation of the Bax C-terminus regulates subcellular location and cell death. EMBO J. 1999;18:2330–2341. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schinzel A, Kaufmann T, Schuler M, Martinalbo J, Grubb D, Borner C. Conformational control of Bax localization and apoptotic activity by Pro168. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:1021–1032. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Upton JP, Valentijn AJ, Zhang L, Gilmore AP. The N-terminal conformation of Bax regulates cell commitment to apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:932–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, Marzo I, Snow BE, Brothers GM, et al. Molecular characterization of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature. 1999;397:441–446. doi: 10.1038/17135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kratz E, Eimon PM, Mukhyala K, Stern H, Zha J, Strasser A, et al. Functional characterization of the Bcl-2 gene family in the zebrafish. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1631–1640. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Millar DG, Shore GC. Mitochondrial Mas70p signal anchor sequence. Mutations in the transmembrane domain that disrupt dimerization but not targeting or membrane insertion. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12229–12232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeong SY, Gaume B, Lee YJ, Hsu YT, Ryu SW, Yoon SH, et al. Bcl-x(L) sequesters its C-terminal membrane anchor in soluble, cytosolic homodimers. Embo J. 2004;23:2146–2155. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nechushtan A, Smith CL, Lamensdorf I, Yoon SH, Youle RJ. Bax and Bak coalesce into novel mitochondria-associated clusters during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1265–1276. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruffolo SC, Shore GC. BCL-2 selectively interacts with the BID-induced open conformer of BAK, inhibiting BAK auto-oligomerization. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25039–25045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302930200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan C, Dlugosz PJ, Peng J, Zhang Z, Lapolla SM, Plafker SM, et al. Auto-activation of the apoptosis protein Bax increases mitochondrial membrane permeability and is inhibited by Bcl-2. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:14764–14775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602374200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abell BM, Rabu C, Leznicki P, Young JC, High S. Post-translational integration of tail-anchored proteins is facilitated by defined molecular chaperones. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1743–1751. doi: 10.1242/jcs.002410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stefanovic S, Hegde RS. Identification of a targeting factor for posttranslational membrane protein insertion into the ER. Cell. 2007;128:1147–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki M, Youle RJ, Tjandra N. Structure of Bax: coregulation of dimer formation and intracellular localization. Cell. 2000;103:645–654. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuwana T, Mackey MR, Perkins G, Ellisman MH, Latterich M, Schneiter R, et al. Bid, Bax, and lipids cooperate to form supramolecular openings in the outer mitochondrial membrane. Cell. 2002;111:331–342. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roucou X, Montessuit S, Antonsson B, Martinou JC. Bax oligomerization in mitochondrial membranes requires tBid (caspase-8-cleaved Bid) and a mitochondrial protein. Biochem J. 2002;368:915–921. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ott M, Norberg E, Walter KM, Schreiner P, Kemper C, Rapaport D, et al. The mitochondrial TOM complex is required for tBid/Bax-induced cytochrome c release. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27633–27639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703155200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanjuan Szklarz LK, Kozjak-Pavlovic V, Vogtle FN, Chacinska A, Milenkovic D, Vogel S, et al. Preprotein transport machineries of yeast mitochondrial outer membrane are not required for Bax-induced release of intermembrane space proteins. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Setoguchi K, Otera H, Mihara K. Cytosolic factor- and TOM-independent import of C-tail-anchored mitochondrial outer membrane proteins. Embo J. 2006;25:5635–5647. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brookes PS, Pinner A, Ramachandran A, Coward L, Barnes S, Kim H, et al. High throughput two-dimensional blue-native electrophoresis: a tool for functional proteomics of mitochondria and signaling complexes. Proteomics. 2002;2:969–977. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200208)2:8<969::AID-PROT969>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]