Abstract

The CRH family of ligands signals via two distinct receptors, CRH-R1 and CRH-R2. Previous studies localized CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 to a subset of anterior pituitary corticotropes and gonadotropes, respectively. However, numerous studies have indicated that stress and CRH activity can alter the secretion of multiple anterior pituitary hormones, suggesting a broader expression of the CRH receptors in pituitary. To examine this hypothesis, the in vivo expression of CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNA was further characterized in adult mouse pituitary. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that CRH-R1 mRNA is greater than 100-fold more abundant than CRH-R2 mRNA in male and female mouse pituitaries. Dual in situ hybridization analysis identified cell-specific CRH-R1 expression in the anterior pituitary. At least half of the CRH-R1-positive cells expressed proopiomelanocortin-mRNA (50% in females; 70% in males). In females, a significant percentage of the cells expressing CRH-R1 also expressed transcript for prolactin (40%), LHβ (10%), or TSH (3%), all novel sites of CRH-R1 expression. Similarly in males, a percentage of CRH-R1-positive cells expressed prolactin (12%), LHβ (13%), and TSH (5%). RT-PCR studies with immortalized murine anterior pituitary cell lines showed CRH-R1 and/or CRH-R2 expression in corticotropes (AtT-20 cells), gonadotropes (αT3-1 and LβT2 cells), and thyrotropes (αTSH cells). Whereas CRH-R1 expression in corticotropes is well established, the presence of CRH-R1 mRNA in a subset of lactotropes, gonadotropes, and thyrotropes establishes these cell types as novel sites of murine CRH-R1 expression and highlights the pituitary as an important site of interaction between the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal and multiple endocrine axes.

Corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1 mRNA is detected in multiple mouse anterior pituitary cell types, including corticotropes, lactotropes, and gonadotropes, in a sexually dimorphic pattern.

The neuroendocrine aspect of the mammalian stress response is initiated by the release of CRH from hypothalamic neurons into the pituitary portal system. In the anterior pituitary, CRH receptor (CRH-R) activation stimulates proopiomelanocortin (POMC) synthesis and ACTH hormone release from corticotropes, followed by adrenal secretion of glucocorticoids, and the subsequent physiological changes associated with the classic stress response. In addition to this neuroendocrine role, CRH acts at numerous sites in the central nervous system and the periphery to mediate anxiogenic, immune, reproductive, autonomic, and metabolic functions (1,2,3).

In mammals, the CRH family of peptides includes CRH, urocortin (Ucn)-I (4), Ucn II/stresscopin-related peptide (Ucn-II) (5,6), and urocortin III/stresscopin (Ucn-III) (5,7). The urocortins are distributed throughout the brain and periphery and have diverse roles in physiology, including roles in cardiac/vascularization, immune/inflammation, lipogenesis, and gastrointestinal function (8,9).

Two major receptor subtypes bind the CRH family of ligands. These receptors belong to the class B1 subfamily of seven transmembrane G protein-coupled receptors and signal via a number of intracellular signaling pathways, most notably adenylate cyclase/protein kinase A (10). The type 1 CRH receptor, CRH-R1, and the type 2 CRH receptor, CRH-R2, are translated from distinct gene products and share 70% amino acid identity. The highest region of divergence is in their N-terminal or ligand binding regions, consistent with their selectivity for the various CRH-like ligands. CRH-R1 binds both CRH and Ucn-I with high affinity and has little to no affinity for Ucn-II and Ucn-III (4,10,11,12,13,14). CRH-R2 binds the urocortins, Ucn-I, -II, and -III, with high affinity and binds CRH with significantly reduced affinity (15).

The CRH receptors are expressed at numerous sites within the rodent central nervous system and periphery and are associated with distinct functional roles. In the brain, CRH-R1 is localized to cortical, limbic, thalamic/hypothalamic, cerebellar, somatic, and sensory nuclei (16,17,18). CRH-R1 is expressed in the pituitary and is localized to the intermediate lobe and a subset of anterior pituitary corticotropes, in which it mediates CRH- induced ACTH release (16,17). The functions related to CRH-R1 activation, both centrally and at the pituitary, involve the maintenance and regulation of homeostasis in response to stress (19). CRH-R2 has two major splice variants in rodents, CRH-R2α and CRH-R2β. The α-variant is expressed predominantly in brain including the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and lateral septum, and in the pituitary, whereas CRH-R2β is expressed largely at peripheral sites including heart, lung, skin, skeletal muscle, and gastrointestinal tract and in the choroid plexus (18,20,21,22). Analysis of CRH-R2-deficient mice demonstrated an increased sensitivity to stress and suggested that this receptor functions to modulate the stress response associated with CRH-R1 activation (19).

Stress has long been known to alter the function of multiple endocrine axes, both via central mechanisms and at the pituitary (23,24,25,26,27,28,29). Whereas CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNA have been detected in anterior pituitary (16,17,18,30,31), a complete characterization of CRH receptor expression in the various cell types in the murine anterior pituitary has not been described. Previous in situ hybridization analyses have shown CRH-R1 expression in a subset of anterior pituitary corticotropes (16,17) and CRH-R2 expression in a subset of rat gonadotropes (30). In this study, we use dual in situ hybridization studies and RT-PCR to detect mouse CRH receptors (mCRH-R) in multiple anterior pituitary cell types. An understanding of the specific cell types expressing CRH receptors in the anterior pituitary is required for developing hypotheses to explain novel roles of CRH family signaling in the pituitary, including the sites and potential mechanisms underlying interactions between the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal and additional endocrine axes.

Materials and Methods

Animals and sample collection

Twelve-week-old male and female C57BL/6 mice (bred and raised in the laboratory colony) were used for all experiments. Mice were maintained on a 14-h light, 10-h dark schedule with lights on between 0600 and 2000 h and had access to food and water ad libitum. All animal experiments were approved by the University of Michigan Committee on Use and Care of Animals and performed according to National Institutes of Health guidelines. Mice were killed under basal nonstressed conditions and pituitaries were removed and immediately placed at −80 C. Female mice used for the real-time RT-PCR analysis were killed at proestrus. The female mice used for the dual in situ hybridization studies were both proestrus and diestrus because previous studies have shown no difference in the total number of CRH-R1-positive cells per field in male, proestrus, metestrus, or diestrus mouse anterior pituitary (Speert D., and N. Westphal, data not shown).

Real-time RT-PCR

RNA isolation and real-time RT-PCR were performed as described previously, with minor modifications (32). Total cellular RNA was isolated from two pooled pituitaries by homogenization with a Polytron (Kinematica, Inc., Johnson City, TN) in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). At least three independent sets of biological samples were used for RNA isolation. Total pituitary RNA was treated with ribonuclease-free deoxyribonuclease according to the manufacturer’s protocol (DNAfree-Turbo; Ambion, Austin, TX). Two pituitaries yielded approximately 20 μg of RNA. Five micrograms of DNA-free RNA were used for first-strand cDNA synthesis using random hexamer primers and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). PCRs (25 μl) contained 2 μl cDNA template, 12.5 μl 2× SYBR Green I master mix (SuperArray; Bioscience Corp., Frederick, MD), and 250–500 nm forward and reverse primers. The primers used for mCRH-R1 analysis were: 5′-CGCAAGTGGATGTTCGTCT-3′ and 5′-GGGGCCCTGGTAGATGTAGT-3′ and correspond to sequences in exons 7 and 9, respectively. The primers used for mCRH-R2 analysis were: 5′-AAGCTGGTGATTTGGTGGAC-3′ and 5′-GGTGGATGCTCGTAACTTCG-3′ and correspond to sequences in exons 9 and 11, respectively. Reactions were carried out in a iCycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The cycling conditions included 10 min at 95 C and 40 cycles at 95 C for 20 sec, 60 C for 20 sec, and 72 C for 20 sec, followed by melt curve analysis. mCRH-R1 and mCRH-R2 gene-specific expression were normalized in parallel reactions with TATA-binding protein (TBP) gene expression, which was not regulated between sexes. Primer sequences for TBP were: 5′-GAACAATCCAGACTAGCAGCA-3′ and 5′-GGGAACTTCACATCACAGCTC-3′. Differences in CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 gene expression between and within sexes were calculated using efficiency corrected values based on the formula: R = (Etarget)ΔCPtarget/(Eref)ΔCPref where E is efficiency and CP is crossing point (33).

In situ hybridization riboprobes

The CRH-R1 antisense riboprobe was synthesized from a plasmid (TOPO PCR Blunt II) containing 1.1 kb of the CRH-R1 coding region (bases 258-1339), matching GenBank accession no. NM_007762. For riboprobe synthesis, the TOPO CRH-R1 plasmid was linearized with XhoI and transcribed with SP6 RNA polymerase (Promega Corp., Madison, WI). The CRH-R2 insert was isolated by PCR using Pfu proofreading polymerase from an expression vector containing the full-length CRH-R2β cDNA (CMV-CRHR2β-neo) that was originally cloned from mouse heart. The primers used to isolate the CRH-R2 insert are as follows: 5′-CCTGGGTCACTGTGTTTCCGTGGT-3′ and 5′-CCTCTGAGGGTCCTGTGATGTC-3′. They amplified a 1.1-kb product that spanned exons 5–13 of CRH-R2 (thereby detecting both the α- and β-splice variants, GenBank accession no. NM_009953, nucleotides 551-1676) and included approximately 300 bp of 3′ untranslated region. The PCR product was gel purified, subcloned into the PCR Blunt II TOPO vector, and confirmed by sequencing. The TOPO CRH-R2 plasmid was linearized with KpnI and the antisense riboprobe was transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase (Promega). CRH-R1 and -R2 riboprobes were double labeled with 35S-uridine 5-triphosphate (UTP)/35S-CTP (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Inc., Boston, MA). Riboprobes for rat prolactin (PRL), rat proopiomelanocortin (POMC), mouse TSH, mouse GH and mouse LH β-subunit (LHβ) have been described (34) and were labeled with digoxigenin-11-UTP according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (digoxigenin-11-UTP labeling mix; Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN).

Dual in situ hybridization analysis

Pituitaries from male and female mice were cryosectioned (12 μm thick, each pituitary yielded ∼50 sections) and stored at −80 C until use. The procedure for dual in situ hybridization followed Speert et al. (34) with the following modifications. Briefly, slides were hybridized with a 35S-labeled CRH-R1 or -R2 riboprobe (2 × 106 cpm/slide) and a digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled riboprobe (POMC, PRL, TSH, LHβ, or GH) in 50% formamide hybridization buffer overnight at 55 C. After ribonuclease A treatment, slides were washed in decreasing salt solutions (2×, 1×, and 0.5× saline sodium citrate) before a final high-stringency wash in 0.1× saline sodium citrate (60 C, 1 h). Slides were washed in buffer 1 [100 mm Tris (pH 8.0), 50 mm NaCl] and blocked in buffer 1 containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1% normal sheep serum. Slides were incubated overnight with anti-DIG antibody coupled to alkaline phosphatase (Roche) diluted 1:10,000 (1:20,000 for GH) in fresh block buffer. Equilibration in alkaline substrate buffer [100 mm NaCl, 100 mm Tris (pH 9.5), 50 mm MgCl2], the color reaction, and subsequent postfixation steps were performed as described (34). For 35S-CRH-R1 and -R2 detection, slides were dipped in Ilford K5 nuclear emulsion (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) and stored for 4–6 wk in the dark at 4 C. Slides were developed in Kodak D19 developer (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, NY; 2 min) and Rapid Fixative (Kodak; 3 min), rinsed in water, dehydrated briefly in increasing alcohols and xylenes, and coverslipped with Permount (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Emulsion dipped slides were analyzed on a Leica microscope (Leitz DMR, Wetzlar, Germany) and both bright-field and dark-field images were captured using a digital imaging/camera system (Optronics, Goleta, CA). Dual-labeled cells were DIG positive and contained silver grains (CRH-R1 signal). To quantify the number of CRH-R1 cells that expressed the various pituitary hormones, the number of CRH-R1-positive cells and the number of CRH-R1 and pituitary hormone-labeled (dual labeled) cells were counted per field. For cell quantification, positive cells within five to 10 fields per section were analyzed for each mouse (one to two sections/mouse, n = 2–5 mice/sex per pituitary hormone). For each hormone, the percentage of CRH-R1 cells that were dual labeled was calculated by dividing the total number of dual cells by the total number of CRH-R1 cells and multiplying by 100.

RT-PCR of pituitary cell lines

αT3-1, LβT2, αTSH, and AtT-20 cell cultures were grown to 80% confluence in DMEM + 10% fetal calf serum + 25 μg/ml gentamicin, whereas GH3 and GH4C1 cell cultures were grown to 80% confluence in Ham’s/F12 + 10% fetal calf serum + 25 μg/ml gentamicin. RNA was isolated, treated with deoxyribonuclease, and used for first-strand cDNA synthesis as previously described (32). PCRs (50 μl) for CRH-R1 used 2.5 U Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) in 1× PCR buffer (Invitrogen) containing 1.5 mm MgCl2, 1 μl cDNA, 0.3 μm forward and reverse primer, and 0.3 mm deoxynucleotide triphosphates (Invitrogen). The cycling conditions included: activation at 94 C for 3 min, and 35 cycles at 94 C for 30 sec, 60 C for 60 sec, and 72 C for 45 sec, followed by an elongation at 72 C for 2 min. The forward and reverse primers for CRH-R1, which function for mouse and rat transcripts, were 5′-CCTGCCTTTTTCTACGGTGTCC-3′ and 5′-GGTGAGCTGGACCACAAAC-3′, respectively. Cycling reactions were carried out in a PTC-100 Programable thermal controller (MJ Research, Inc., Waltham, MA). PCRs (25 μl) for CRH-R2 used 1.25 U Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) in 1× PCR buffer (Invitrogen) containing 1.5 mm MgCl2, 1 μl cDNA, 0.4 μm forward and reverse primer, and 0.3 mm deoxynucleotide triphosphates (Invitrogen). The cycling conditions included: activation at 94 C for 3 min, and 40 cycles at 94 C for 30 sec, 58 C for 60 sec, and 72 C for 90 sec, followed by an elongation at 72 C for 10 min. The forward primer for CRH-R2 was 5′-GTCCCTACACCTACTGCAACAC-3′ for all cell lines, whereas the reverse primer was 5′-CAGAATGAAGGTGGTGATGAGGTT-3′ for murine cell lines αT3-1, LβT2, αTSH, and AtT-20 and 5′-CAGGATGAAGGTGGTGATGAGGTT-3′ for rat cell lines GH3 and GH4C1. PCRs for β-actin were performed as described for CRH-R2 but with cycling conditions as follows: activation at 94 C for 3 min, 30 cycles at 94 C, 50C, and 72 C for 1 min each, followed by an elongation at 72 C for 5 min. The forward and reverse primers for β-actin, which function under these conditions for mouse and rat transcripts, were 5′-GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG-3′ and 5′-TCTCAGCTGTGGTGGTGAAG-3′ respectively. PCR products and 1 kb DNA ladder (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY) were electrophoresed through 2% agarose gels stained with SYBR Safe DNA gel stain (Invitrogen). RNA isolation and RT-PCR analysis were performed in duplicate on two separately isolated cell preparations for each cell line.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance in the real-time RT-PCR experiments (three independent sets of biological samples) was determined using Student’s t test (Statview software; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). In the dual in situ hybridization experiments, two to five mice of each sex were analyzed for each hormone (five to 10 representative fields from one to two sections per mouse). The percentage of CRH-R1 cells that were dual labeled for each hormone was compared across sexes using Student’s t test with P < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

CRH-R1 mRNA is more abundant than CRH-R2 mRNA in the murine pituitary

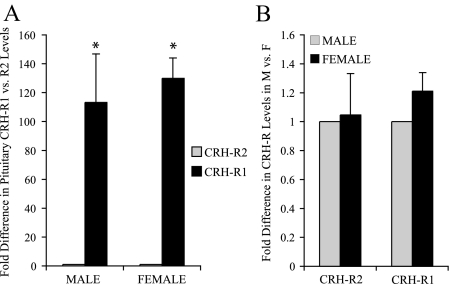

Previous studies have demonstrated that both CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNA are expressed in the rodent pituitary (16,17,30), but the relative abundance of these receptor mRNAs and their gender-specific expression have not been examined quantitatively. Using real-time RT-PCR, mRNA for both CRH receptors was detected in male and female mouse pituitaries. Strikingly, CRH-R1 mRNA expression was greater than 100-fold more abundant than CRH-R2 mRNA in both male and female pituitaries (Fig. 1A), whereas CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNA levels were not significantly different between sexes (Fig. 1B). Thus, whereas CRH-R1 and -R2 mRNA levels in mouse pituitary were significantly different in abundance, with CRH-R1 expressed at much higher levels than CRH-R2, no major gender differences were detected.

Figure 1.

CRH receptor expression in the murine pituitary as measured by real-time RT-PCR. A, CRH-R1 mRNA was greater than 100-fold more abundant than CRH-R2 mRNA in the murine pituitary. Average cycle threshold values for male CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 expression were 25.0 ± 0.2 and 31.8 ± 0.4, respectively. Average cycle threshold values for female CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 expression were 25.8 ± 0.2 and 32.8 ± 0.2, respectively. Values are represented as fold difference ± sem in CRH-R1 vs. CRH-R2 expression in male or female pituitary. *, P < 0.05. B, CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 did not exhibit sexually dimorphic expression in the murine pituitary. CRH-R2 expression was not statistically different between male and female pituitaries, with an average expression ratio of 1.05 ± 0.29 (female to male). Similarly, CRH-R1 mRNA levels were not different between males and females, with an average expression ratio of 1.2 ± 0.13 (female to male). Values in B were normalized with TBP expression and are represented as normalized fold difference in CRH receptor expression between male and female pituitaries.

CRH-R1 mRNA is expressed in a subset of POMC-positive cells in anterior pituitary

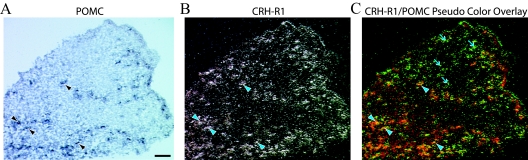

In both sexes, in situ hybridization studies detected CRH-R1 mRNA in the intermediate lobe (data not shown) and individual cells throughout the murine anterior pituitary. CRH-R1 expression was not observed in the posterior pituitary, and signal was absent in sense control sections (data not shown). Thus, our general CRH-R1 expression pattern in pituitary is consistent with previous studies in rat and mouse (16). Representative images from anterior pituitary of a dual in situ hybridization experiment in which radiolabeled CRH-R1 riboprobe was cohybridized with DIG-labeled riboprobe for POMC mRNA are depicted in Fig. 2. POMC mRNA was strongly expressed in the intermediate lobe (not shown) as well as in individual cells throughout the anterior pituitary (purple staining, Fig. 2A). CRH-R1 signal in the same section is represented by the silver grains in the dark-field photomicrograph and showed widespread distribution in the anterior pituitary gland (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, large regions devoid of POMC-positive cells exhibited multiple CRH-R1-positive cells [Fig. 2C, arrows, (CRH-R1/POMC pseudocolor overlay)], indicating that cells in addition to POMC-positive cells expressed CRH-R1. Arrowheads (Fig. 2) denote dual-labeled CRH-R1/POMC cells.

Figure 2.

CRH-R1 is expressed in multiple anterior pituitary cell types. Individual pituitaries were cryosectioned (12 μm) and used for dual in situ hybridization analysis. A, Representative bright-field photomicrograph showing a portion of the anterior pituitary from a female mouse (horizontal section). Purple staining corresponds to POMC-positive cells. B, Dark-field image of the pituitary section described in A. The silver grains correspond to CRH-R1-positive signal. C, Pseudocolor overlay showing POMC staining in red and CRH-R1 signal in green. CRH-R1 mRNA was expressed in a subset of POMC-positive cells (depicted by arrowheads); however, numerous CRH-R1-positive cells did not coexpress POMC (arrows). The scale bar (A), approximately 100 μm.

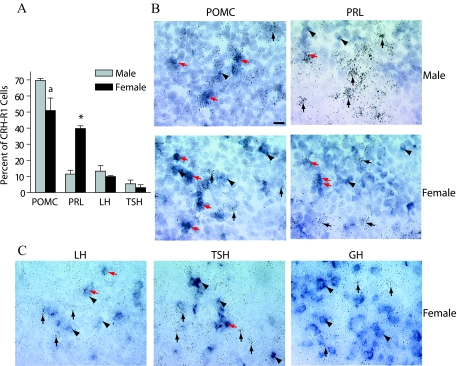

Detailed examination of the CRH-R1 and POMC colocalized signal revealed that at least half of CRH-R1-positive cells expressed POMC mRNA (females: 50% of CRH-R1-positive cells; males: 70% of CRH-R1-positive cells, Fig. 3, A and B). There were no significant differences between males and females in the total number of anterior pituitary CRH-R1-positive cells or the percentage of POMC-positive cells that expressed CRH-R1 mRNA (female: 43 ± 6%; male: 49 ± 2%). These results are consistent with earlier reports that demonstrated CRH-R1 mRNA expression and CRH binding on ACTH-positive cells in vivo and in culture (17,35).

Figure 3.

Identification of the endocrine cell types that express CRH-R1 mRNA in the anterior pituitary by dual in situ hybridization. CRH-R1 was expressed in a subset of POMC-, LH-, PRL-, and TSH-positive cell types in male and female pituitaries. A, The percentage of CRH-R1 cells that colocalize with POMC, PRL, LH, or TSH mRNA was quantified. Dual-labeled cells and total CRH-R1-positive cells were counted for males and females separately. The percentage of dual-labeled cells was calculated by dividing the total number of dual-labeled cells by the total number of R1 cells × 100 for each sex. There is a significant difference in the percentage of CRH-R1-positive cells expressing PRL between sexes (*, P < 0.0001) and a trend toward a sexually dimorphic difference for the percentage of CRH-R1-positive cells expressing POMC (a, P = 0.055). B and C, Representative bright-field photomicrographs are shown from dual in situ hybridization analyses with radiolabeled CRH-R1 riboprobe cohybridized with DIG-labeled riboprobes for POMC (B), PRL (B), LH (C), TSH (C), or GH (C). Representative panels in both male and female pituitaries are shown for POMC and PRL, whereas only representative panels of female pituitaries are shown for cell types with no sexual dimorphism. The red arrows indicate representative cells that coexpress CRH-R1 (silver grains) and hormone (DIG precipitate). Black arrows indicate examples of cells that express only CRH-R1, whereas black arrowheads point to hormone only cells. Scale bar (male POMC panel), approximately 20 μm. These experiments were performed in two groups in succession. Experiments represented in panels for LH, TSH, and GH and for POMC and PRL were conducted in separate experiments, with the same CRH-R1 riboprobe and emulsion exposure times.

Cellular localization of CRH-R1 mRNA reveals expression in PRL-, LHβ-, and TSH-expressing cell types

A significant percentage of the CRH-R1-positive cells did not express POMC mRNA, suggesting that a subset of CRH-R1-positive cells would express mRNA for other pituitary hormones. Indeed, CRH-R1 mRNA colocalized with multiple pituitary hormones in both the male and female anterior pituitaries. In females, a significant percentage of the CRH-R1 population expressed PRL (39.8%), LHβ (10.0%), or TSH (3.0%) mRNA, all novel sites of CRH-R1 expression (Fig. 3). In males, CRH-R1 was detected in cells expressing PRL (11.5%), LHβ (13.3%), and TSH (5.4%) mRNA (Fig. 3). CRH-R1 did not appear to colocalize significantly with GH-expressing cells. Female mice exhibited a significantly higher percentage of CRH-R1/PRL cells than male mice (P < 0.0001).

CRH-R2 mRNA is expressed in the posterior pituitary gland

Pituitary CRH-R2 mRNA expression was also examined by dual in situ hybridization analysis (data not shown). Whereas CRH-R2 signal was readily observed in the lateral septum in control brain sections, CRH-R2 signal could not be localized to specific anterior pituitary cell types. Some signal was detected in the posterior pituitary and is in line with the results of others (16). These data are consistent with our results from the real-time RT-PCR experiments in Fig. 1, in which CRH-R2 signal did not reach the threshold of detection until PCR cycle 32–33, near the limit of reliable detection. Thus, CRH-R2 mRNA expression under basal conditions in murine anterior pituitary is quite low and below the limit of detection in our dual in situ hybridization analysis; further cell-specific localization was therefore not possible.

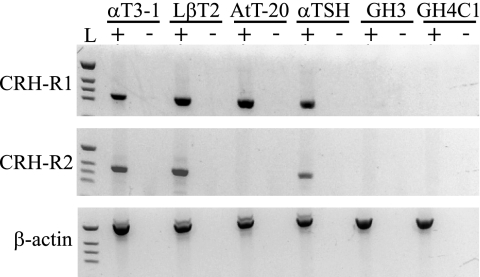

CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNA are detected in multiple immortalized pituitary cell lines

The demonstration of CRH-R1 mRNA in multiple anterior pituitary cell types in vivo suggests that CRH may signal at these cell types to alter pituitary hormone synthesis and secretion. Because many pituitary hormone expression and secretion studies use a variety of immortalized anterior pituitary cell lines, we tested for the expression of CRH receptor mRNA in these cells. Consistent with CRH-R1 expression on multiple cell types in the murine pituitary, RT-PCR of mouse or rat immortalized pituitary cell lines showed detectable CRH-R1 mRNA not only in the murine corticotrope-like AtT-20 cell line but also in the murine gonadotrope-like αT3-1 and LβT2 cell lines and the murine thyrotrope-like cell line αTSH (Fig. 4). CRH-R1 was not detected in GH3 or GH4C1, the two rat somatolactotrope-like cell lines tested. CRH-R2 mRNA was also detected by RT-PCR in αT3-1, LβT2, and αTSH cells but was not detected in AtT-20, GH3, or GH4C1 cells.

Figure 4.

RT-PCR analyzing CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 in immortalized pituitary cell lines. The top panel shows CRH-R1 PCR results with a band of the predicted size (321 bp) present in αT3-1, LβT2, AtT-20, and αTSH cells. The middle panel shows the PCR product for CRH-R2 with the predicted size (380 bp) in αT3-1, LβT2, and αTSH cells. The bottom panel shows the results of the β-actin PCR with the predicted band size (536 bp) present in all cells, demonstrating cDNA quality. PCRs were performed on cDNA template (+) and a negative reverse transcriptase control (−) for each cell line, and a 1-kb ladder (L) was used for size determination. The expression of CRH receptors in αT3-1 cells was presented in poster format at the 85th Annual Meeting of The Endocrine Society, Philadelphia, PA (2003).

Discussion

This study examined cell-specific expression of CRH receptor mRNA in the murine anterior pituitary. CRH-R1 mRNA expression within corticotropes has been described (17) and was further confirmed in the present study in male and female POMC-expressing cells in vivo and in AtT-20 corticotrope-like cells. Interestingly, CRH-R1 mRNA expression was also detected in PRL-, LH-, and TSH-expressing cells in male and female murine pituitary, which are newly described sites of CRH-R1 expression.

Stress and the actions of CRH modify the secretion of pituitary hormones from multiple endocrine cells, suggesting that multiple anterior pituitary cell types might express CRH receptors. Indeed, mouse gonadotrope-like cells (αT3-1 and LβT2) expressed mRNA for both CRH receptors (Fig. 4), consistent with CRH-R2 mRNA expression in rat gonadotropes (30). In our in situ hybridization studies, CRH-R2 expression was not readily detected in the murine anterior pituitary (including gonadotropes), suggesting developmentally regulated and/or species-specific expression of CRH-R2 mRNA. However, CRH-R1 mRNA was detected in a subset of gonadotropes in both male and female mice (Fig. 3). The relative percentage of the total CRH-R1 population that localized to gonadotropes was not different between the sexes, suggesting that sex steroids are not principal regulators of CRH-R1 expression in gonadotropes. CRH-R1 expression in gonadotropes further suggests that this cell type is a target of stress-induced CRH signaling. However, it should be noted that only a small percentage of the total gonadotrope population expressed CRH-R1 (10–15%), and whereas CRH could potentially signal at gonadotropes, the in vivo significance of such colocalization needs to be carefully examined.

Both CRH-receptors were also identified in murine thyrotrope-like cells, αTSH (Fig. 4), suggesting that thyrotropes in vivo might also express CRH receptors. Indeed, a small subset of thyrotropes showed detectable CRH-R1 mRNA (Fig. 3), although the functional significance of this low level of expression is unclear. Numerous studies in nonmammalian vertebrates have shown that CRH can act as a potent TSH releasing hormone, stimulating TSH secretion from amphibians (24,36), birds (37,38), reptiles (39), and fish (40). Studies using in vitro-cultured chicken pituitaries have identified CRH-R2 mRNA expression on thyrotropes and experiments with a selective CRH-R2 agonist (Ucn-III) and antagonist (antisauvagine-30) support the hypothesis that CRH-R2 (but not CRH-R1) mediates CRH-induced TSH release in chicken (38). In lower vertebrate species, it appears that CRH’s ability to simultaneously stimulate both the adrenal and thyroid axes via distinct CRH receptors is an important mechanism for developmental plasticity (41). Although intriguing, the absence of detectable CRH-R2 mRNA expression in murine adult anterior pituitary cell types, combined with the small percentage of TSH-positive cells coexpressing CRH-R1, indicates that thyroid-adrenal interaxial communication in adult rodents is limited. However, it is possible that pituitary CRH receptor expression is induced under specific developmental or physiological conditions not examined by the present studies.

CRH-R1 expression was not readily detected in GH-positive anterior pituitary cells in either male or female mice. Likewise, neither CRH-R1 nor CRH-R2 mRNA was detected in the rat somatolactotroph-like cell lines GH3 and GH4C1 (Fig. 4). Whereas CRH-R1 expression was observed in a population of lactotrophs in vivo (Fig. 3), these immortalized somatolactotroph cell lines could reflect a transition phenotype more closely resembling GH-expressing cells with regard to CRH receptor expression. Previous studies identified a very small subpopulation of GH-expressing and GH/ACTH coexpressing cells that respond to CRH treatment (42,43). However, the low percentage of CRH-responsive GH-positive cells combined with our results (no detectable CRH-R1 expression on GH expressing cells) suggest that CRH does not directly regulate GH expression or release in the basal state in the murine pituitary.

The ability for numerous stressors to stimulate prolactin secretion has been known for many years, but the mechanisms underlying this regulation remain unclear (23,27,44,45). More recently, studies have begun to demonstrate a specific role for CRH and CRH receptors in mediating this interaction (46,47,48). The CRH-R1 selective antagonist CP-154,526 suppressed immobilization-induced PRL release in the rat (46) and inhibited hypoxia stress-induced prolactin immunoreactivity and mRNA expression in rat pituitary (48). Together these studies indicated that CRH-R1 represented a possible mechanism mediating CRH-induced prolactin release. However, the studies did not examine CRH receptor expression in lactotropes and left open the possibility that CRH played a permissive role in which additional secondary factors directly stimulated PRL release. The identification of CRH-R1 expression in PRL-expressing cells in this study (Fig. 3) certainly provides evidence that CRH could directly signal at these cells.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that many pituitary cells store and release more than one anterior pituitary hormone (multihormonal cells). Multihormonal corticotropes (42,49,50), somatogonadotropes (51), mammosomatotropes (52), multihormonal thyrotropes (53), and many other combinations have been identified (43,54). These multihormonal cells exhibit plasticity in hormone coexpression across development (55) and may represent multipotential cells that can be recruited into specific populations as cellular conditions (e.g. stress) dictate. Studies have also identified monohormonal and multihormonal anterior pituitary cells that express multiple hypothalamic-releasing hormone receptors (multiresponsive cells) (43,56). These cells challenge our conventional understanding of pituitary function and illustrate an increasingly complex and plastic environment in which multiple hormones are cosecreted in response to one or more hypothalamic-releasing hormones.

Our dual in situ hybridization studies colocalized CRH-R1 mRNA with the expression of one pituitary hormone at a time; however, a percentage of the CRH-R1-positive cells may express multiple pituitary hormones. Recent data from Senovilla et al. (42) revealed the multihormonal and multiresponsive potential of ACTH-positive cells in mouse anterior pituitary. In male mice, only a small subset of ACTH-positive cells (∼25%) was multihormonal. In contrast, in female mice, the majority of ACTH-positive cells (∼66%) were multihormonal, costoring PRL (30%) or GH (35%) most frequently, with only 30% of the ACTH-positive cells being monohormonal. Of the ACTH/GH multihormonal cells, CRH treatment stimulated less than 2% of these cells (42), suggesting that CRH receptor expression is largely absent from GH-expressing cells, consistent with our results. Perhaps more intriguing were the findings that PRL is costored in 30% of ACTH-expressing cells in female mice and that 40% of these ACTH/PRL multihormonal cells respond to CRH (42). Consistent with this result, we identified in this study a significantly greater percentage of CRH-R1-positive cells that colocalize with PRL mRNA expression in female pituitaries compared with males (40 vs. 12%, Fig. 3). Together these results suggest that CRH-R1 is expressed in a significant population of both monohormonal (ACTH or PRL) and ACTH/PRL multihormonal cells in female anterior pituitary. Future binding studies will confirm the presence of functional CRH-R1 on these monohormonal and multihormonal cells. These results are particularly interesting because CRH-binding protein, an important modulator of CRH/Ucn-1 activity, is also highly expressed in PRL-expressing cells in female mouse pituitary, and like CRH-R1, the reason for its expression in these cells is still unclear (34). The expression of both of these genes in PRL-expressing cells further suggests that the female lactotrope (mono- and multihormonal) is an important, yet largely unexplored, target of CRH signaling.

Numerous studies have indicated that stress and the actions of CRH can alter the function of multiple endocrine axes, including those associated with development, reproduction, and lactation. The present study provides evidence of CRH-R1 mRNA expression in multiple endocrine cells associated with each of these functions and suggests a direct mechanism for CRH/Ucn-I signaling at these cell types. Whereas detailed studies will be necessary to elucidate the physiological significance and effects of CRH-R1 expression on these monohormonal and multihormonal corticotropes, lactotropes, gonadotropes, and thyrotropes, these data further highlight the pituitary as an important, and remarkably plastic, site of interactions between the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and multiple endocrine systems.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Debra Speert for her contributions to the early stages of this study and Linda Gates for her assistance with the cell culture work. The αT3-1, LβT2, and αTSH cell lines were kindly provided by Dr. Pamela Mellon (University of California, San Diego, San Diego, CA).

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants F31 NS048775 (to N.J.W.), T32 GM07544 (to R.T.E.), T32 HD07048 (to N.J.W. and R.T.E.), DK42730, and DK57660 (to A.F.S.) and Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center Cell and Molecular Biology Core National Institutes of Health Grant DK20572 (to William Herman).

Results from this work were presented at the 89th Annual Meeting of The Endocrine Society Meeting, Toronto, Canada, 2007.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online September 11, 2008

Abbreviations: CRH-R, CRH receptor; DIG, digoxigenin; LHβ, LH β-subunit; mCRH-R, mouse CRH receptor; POMC, proopiomelanocortin; PRL, prolactin; TBP, TATA-binding protein; Ucn, urocortin; UTP, uridine 5-triphosphate.

References

- Vale W, Spiess J, Rivier C, Rivier J 1981 Characterization of a 41-residue ovine hypothalamic peptide that stimulates secretion of corticotropin and β-endorphin. Science 213:1394–1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AJ, Berridge CW 1990 Physiological and behavioral responses to corticotropin-releasing factor administration: is CRF a mediator of anxiety or stress responses? Brain Res Brain Res Rev 15:71–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB 1991 Physiology and pharmacology of corticotropin-releasing factor. Pharmacol Rev 43:425–473 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan J, Donaldson C, Bittencourt J, Perrin MH, Lewis K, Sutton S, Chan R, Turnbull A, Lovejoy DA, Rivier C, Rivier J, Sawchenko PE, Vale W 1995 Urocortin, a mammalian neuropeptide related to fish urotensin I and to corticotropin-releasing factor. Nature 378:287–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SY, Hsueh AJ 2001 Human stresscopin and stresscopin-related peptide are selective ligands for the type 2 corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Nat Med 7:605–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes TM, Lewis K, Perrin MH, Kunitake KS, Vaughan J, Arias CA, Hogenesch JB, Gulyas J, Rivier J, Vale WW, Sawchenko PE 2001 Urocortin II: a member of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) neuropeptide family that is selectively bound by type 2 CRF receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:2843–2848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K, Li C, Perrin MH, Blount A, Kunitake J, Donaldson C, Vaughan J, Reyes TM, Gulyas J, Fischer W, Bilezikjian L, Rivier J, Sawchenko P, Vale WW 2001 Identification of urocortin III, an additional member of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) family with high affinity for the CRF2 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:7570–7575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Nishiyama M, Tanaka Y, Noguchi T, Asaba K, Hossein PN, Nishioka T, Makino S 2004 Urocortins and corticotropin releasing factor type 2 receptors in the hypothalamus and the cardiovascular system. Peptides 25:1711–1721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez V, Wang L, Million M, Rivier J, Tache Y 2004 Urocortins and the regulation of gastrointestinal motor function and visceral pain. Peptides 25:1733–1744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillhouse EW, Grammatopoulos DK 2006 The molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of the biological activity of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptors: implications for physiology and pathophysiology. Endocr Rev 27:260–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C-P, Pearse RV, O'Connell S, Rosenfeld MG 1993 Identification of a seven transmembrane helix receptor for corticotropin-releasing factor and sauvagine in mammalian brain. Neuron 11:1187–1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Lewis KA, Perrin MH, Vale WW 1993 Expression cloning of a human corticotropin-releasing-factor receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:8967–8971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vita N, Laurent P, Lefort S, Chalon P, Lelias J-M, Kaghad M, Le Fur G, Caput D, Ferrara P 1993 Primary structure and functional expression of mouse pituitary and human brain corticotropin releasing factor receptors. FEBS Lett 335:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asaba K, Makino S, Hashimoto K 1998 Effect of urocortin on ACTH secretion from rat anterior pituitary in vitro and in vivo: comparison with corticotropin-releasing hormone. Brain Res 806:95–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grammatopoulos DK, Chrousos GP 2002 Functional characteristics of CRH receptors and potential clinical applications of CRH-receptor antagonists. Trends Endocrinol Metab 13:436–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Pett K, Viau V, Bittencourt JC, Chan RK, Li HY, Arias C, Prins GS, Perrin M, Vale WW, Sawchenko PE 2000 Distribution of mRNAs encoding CRF receptors in brain and pituitary of rat and mouse. J Comp Neurol 428:191–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter E, Sutton S, Donaldson C, Chen R, Perrin M, Lewis K, Sawchenko PE, Vale W 1994 Distribution of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor mRNA expression in the rat brain and pituitary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:8777–8781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers DT, Lovenberg TW, DeSouza EB 1995 Localization of novel corticotropin-releasing factor receptor (CRF2) mRNA expression to specific subcortical nuclei in rat brain: comparison with CRF1 receptor mRNA expression. J Neurosci 15:6340–6350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale TL 2005 Sensitivity to stress: dysregulation of CRF pathways and disease development. Horm Behav 48:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovenberg TW, Chalmers DT, Liu C, DeSouza EB 1995 CRF2a and CRF2b receptor mRNAs are differentially distributed between the rat central nervous system and peripheral tissues. Endocrinology 136:4139–4142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovenberg TW, Liaw CW, Grigoriadis DE, Clevanger W, Chalmers DT, De Souza EB, Oltersdorf T 1995 Cloning and characterization of a functionally distinct CRF receptor subtype from rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:836–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin M, Donaldson C, Chen R, Blount A, Berggren T, Bilezikjian L, Sawchenko P, Vale W 1995 Identification of a second CRF receptor gene and characterization of a cDNA expressed in heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:2969–2973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gala RR 1990 The physiology and mechanisms of the stress-induced changes in prolactin secretion in the rat. Life Sci 46:1407–1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denver RJ, Licht P 1989 Neuropeptide stimulation of thyrotropin secretion in the larval bullfrog: evidence for a common neuroregulator of thyroid and interrenal activity in metamorphosis. J Exp Zool 252:101–104 [Google Scholar]

- Dorshkind K, Horseman ND 2001 Anterior pituitary hormones, stress, and immune system homeostasis. Bioessays 23:288–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olster DH, Ferin M 1987 Corticotropin-releasing hormone inhibits gonadotropin secretion in the ovariectomized rhesus monkey. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 65:262–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel G, Enjalbert A, Proulx L, Pelletier G, Barden N, Grossard F, Dubois PM 1989 Effect of corticotropin-releasing factor on the release and synthesis of prolactin. Neuroendocrinology 49:669–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivier C, Vale W 1984 Influence of corticotropin-releasing factor on reproductive functions in the rat. Endocrinology 114:914–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivest S, Rivier C 1995 The role of corticotropin-releasing factor and interleukin-1 in the regulation of neurons controlling reproductive functions. Endocr Rev 16:177–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama K, Li C, Vale W 2003 Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 2 messenger ribonucleic acid in rat pituitary: localization and regulation by immune challenge, restraint stress, and glucocorticoids. Endocrinology 144:1524–1532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TY, Chen XQ, Du JZ, Xu NY, Wei CB, Vale WW 2004 Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 1 and 2 mRNA expression in the rat anterior pituitary is modulated by intermittent hypoxia, cold and restraint. Neuroscience 128:111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal NJ, Seasholtz AF 2005 GnRH positively regulates corticotropin releasing hormone-binding protein (CRH-BP) expression via multiple intracellular signaling pathways and a multipartite GnRH response element in αT3-1 Cells. Mol Endocrinol 19:2780–2797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L 2002 Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 30:e36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speert DB, McClennen SJ, Seasholtz AF 2002 Sexually dimorphic expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone-binding protein in the mouse pituitary. Endocrinology 143:4730–4741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westlund KN, Wynn PC, Chmielowiec S, Collins TJ, Childs GV 1984 Characterization of a potent biotin-conjugated CRF analog and the response of anterior pituitary corticotropes. Peptides 5:627–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boorse GC, Denver RJ 2004 Expression and hypophysiotropic actions of corticotropin-releasing factor in Xenopus laevis. Gen Comp Endocrinol 137:272–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geris KL, Kotanen SP, Berghman LR, Kuhn ER, Darras VM 1996 Evidence of a thyrotropin-releasing activity of ovine corticotropin-releasing factor in the domestic fowl (Gallus domesticus). Gen Comp Endocrinol 104:139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groef B, Goris N, Arckens L, Kuhn ER, Darras VM 2003 Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH)-induced thyrotropin release is directly mediated through CRH receptor type 2 on thyrotropes. Endocrinology 144:5537–5544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denver RJ, Licht P 1990 Modulation of neuropeptide-stimulated pituitary hormone secretion in hatchling turtles. Gen Comp Endocrinol 77:107–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen DA, Swanson P, Dickey JT, Rivier J, Dickhoff WW 1998 In vitro thyrotropin-releasing activity of corticotropin-releasing hormone-family peptides in coho salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch. Gen Comp Endocrinol 109:276–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groef B, Van der Geyten S, Darras VM, Kuhn ER 2006 Role of corticotropin-releasing hormone as a thyrotropin-releasing factor in non-mammalian vertebrates. Gen Comp Endocrinol 146:62–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senovilla L, Nunez L, Villalobos C, Garcia-Sancho J 2008 Rapid changes in anterior pituitary cell phenotypes in male and female mice after acute, cold stress. Endocrinology 149:2159–2167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalobos C, Nunez L, Frawley LS, Garcia-Sancho J, Sanchez A 1997 Multi-responsiveness of single anterior pituitary cells to hypothalamic-releasing hormones: a cellular basis for paradoxical secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:14132–14137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman ME, Kanyicska B, Lerant A, Nagy G 2000 Prolactin: structure, function, and regulation of secretion. Physiol Rev 80:1523–1631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armario A, Lopez-Calderon A, Jolin T, Castellanos JM 1986 Sensitivity of anterior pituitary hormones to graded levels of psychological stress. Life Sci 39:471–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akema T, Chiba A, Oshida M, Kimura F, Toyoda J 1995 Permissive role of corticotropin-releasing factor in the acute stress-induced prolactin release in female rats. Neurosci Lett 198:146–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck ME, Welt T, Muller MB, Landgraf R, Holsboer F 2003 The high-affinity non-peptide CRH1 receptor antagonist R121919 attenuates stress-induced alterations in plasma oxytocin, prolactin, and testosterone secretion in rats. Pharmacopsychiatry 36:27–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JF, Chen XQ, Du JZ 2006 CRH receptor type 1 mediates continual hypoxia-induced changes of immunoreactive prolactin and prolactin mRNA expression in rat pituitary. Horm Behav 49:181–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs GV 1991 Multipotential pituitary cells that contain adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) and other pituitary hormones. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2:112–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty GC, Garner LL 1977 Immunocytochemical studies of cells in the rat adenohypophysis containing both ACTH and FSH. Nature 265:356–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs GV, Unabia G, Wu P 2000 Differential expression of growth hormone messenger ribonucleic acid by somatotropes and gonadotropes in male and cycling female rats. Endocrinology 141:1560–1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frawley LS, Boockfor FR 1991 Mammosomatotropes: presence and functions in normal and neoplastic pituitary tissue. Endocr Rev 12:337–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalobos C, Nunez L, Garcia-Sancho J 2004 Anterior pituitary thyrotropes are multifunctional cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287:E1166–E1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez L, Villalobos C, Senovilla L, Garcia-Sancho J 2003 Multifunctional cells of mouse anterior pituitary reveal a striking sexual dimorphism. J Physiol 549:835–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs GV, Ellison DG, Ramaley JA 1982 Storage of anterior lobe adrenocorticotropin in corticotropes and a subpopulation of gonadotropes during the stress-nonresponsive period in the neonatal male rat. Endocrinology 110:1676–1692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senovilla L, Garcia-Sancho J, Villalobos C 2005 Changes in expression of hypothalamic releasing hormone receptors in individual rat anterior pituitary cells during maturation, puberty and senescence. Endocrinology 146:4627–4634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]