Abstract

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) is expressed in Alzheimer disease (AD) but not normal aged brain. A functional -463G/A MPO promoter polymorphism has been associated with AD risk through as yet unidentified mechanisms. Here we report that human MPO-463G allele, but not MPO-463A or mouse MPO, is strongly expressed in astrocytes and deposited in plaques in huMPO transgenic mice crossed to the APP23 model. MPO is similarly expressed in astrocytes in human AD tissue. In cortical homogenates of the MPOG-APP23 model, MPO expression correlated with increased levels of a lipid peroxidation product, 4-hydroxynonenal. Fluorescence high-performance liquid chromatography and electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy identified selective accumulation of phospholipid hydroperoxides in two classes of anionic phospholipids, phosphatidylserine (PS-OOH) and phosphatidylinositol (PI-OOH). The same molecular species of PS-OOH and PI-OOH were elevated in human AD brains as compared with non-demented controls. Augmented lipid peroxidation in MPOG-APP23 mice correlated with greater memory deficits. We suggest that aberrant huMPO expression in astrocytes leads to a specific pattern of phospholipid peroxidation and neuronal dysfunction contributing to AD.

Mounting evidence points to oxidative damage as an early event in Alzheimer disease (AD)2 (1-4). Autopsy tissues from patients with mild cognitive impairment or early stage AD show higher levels of lipid peroxidation (5), along with oxidized proteins (6) and nucleic acids (4). Late stage AD is also marked by increased lipid and protein oxidation (7-9). The highly polyunsaturated lipids in brain tissue are susceptible to oxidative damage due to a high level of oxygen consumption and the postmitotic state of neurons. However, specific mechanisms of lipid peroxidation in AD brain have not been definitively identified (reviewed in Ref. 10). Among candidate sources of free radicals and other reactive oxidants in AD brain are mitochondria (11), amyloid β (Aβ) peptides (12), iron (13), and myeloperoxidase (MPO) (14). MPO is an oxidant-generating enzyme that is not present in normal aged brain yet is abundant in amyloid-β plaques in AD brain (14, 15). MPO reacts with H2O2 to oxidize chloride, producing the potent oxidant, hypochlorous acid. MPO also oxidizes nitrate and tyrosine to produce nitrogen dioxide (NO2.) and tyrosyl radicals that cause lipid peroxidation (16-18). Therefore, we hypothesized that MPO-generated radicals may generate lipid peroxides in AD brain, contributing to neuronal dysfunction and memory loss.

To study the effects of MPO in AD, we turned to mouse models, such as APP23, that overexpresses the human APP751 transgene, developing amyloid plaques (19). However, early findings showed that the mouse MPO gene was not expressed in APP23 brain, in contrast to human MPO expression in AD. One possible reason for the aberrant expression of human MPO in AD brain lesions may be the insertion of a primate-specific Alu element in the upstream promoter. This Alu element encodes several response elements recognized by members of the nuclear receptor superfamily of ligand-dependent transcription factors, including peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ/α, liver X receptor and estrogen receptor, as well as SP1 (20-22). The functional -463 G/A promoter polymorphism is in the first of four hexamer response elements in the Alu (20, 23). The -463G site enhances SP1 binding (20), whereas the -463A site enhances estrogen receptor binding (22). The -463A allele is linked to lower MPO gene expression (22). In a number of case-control association studies, the -463G/A polymorphism has been linked to risk for chronic inflammatory states, including AD or cognitive decline (14, 24-28), atherosclerosis (29-31), as well as some cancers (32-35).

To study the effects of human type MPO expression in murine disease models, we created human MPO transgenic mice in which the intact gene was driven by extensive native human promoter elements (36). In an earlier study, we crossed the huMPO transgenic mice to the LDL receptor deficient model (LDLR-/-) of atherosclerosis. The human MPO transgene was expressed in foam cell macrophages in atherosclerosis lesions (36), leading to increased atherosclerosis, along with hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and obesity (36), and increased protein oxidation in lesions (37).

In the present study, we crossed the huMPO transgenic mice to the APP23 model. Findings show that the human MPO -463G allele is strongly expressed in astrocytes, and MPO protein is deposited in plaques, leading to increased lipid peroxidation and greater spatial memory impairment. These findings suggest that aberrant expression of human MPO in astrocytes promotes oxidative damage, contributing to neuronal dysfunction.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals—The APP23 transgenic mice express the human familial AD mutant APP751 isoform with the Swedish double mutation (APPK670N, M671L) under control of the neuronspecific mouse Thy1.2 expression cassette (19). The APP23 mice used in this study were hemizygous for the APP751 transgene and had been backcrossed to C57Bl6/J mice for more than 10 generations. The MPOG and MPOA mice were created on the C57Bl6/J background. Comparisons between MPOG-APP23 and APP23 mice in water maze studies were carried out with littermates.

Transgenic mice carrying the human -463G and A alleles have been previously described (21, 22, 36, 38, 39). The mice were generated by microinjection of a 32-kb BST11071 restriction fragment into C57BL6/J eggs (22). Both transgenes produce functional MPO enzyme, and the cDNA sequences are identical (36). The care of the mice, and all procedures in this study, were approved by the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee and complied with the National Institutes of Health animal care guidelines.

Tissues—Human brain tissue was generously provided by the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center (Belmont, MA), Sun Health Research Institute (Sun City, AZ), and the University of California, San Diego. For oxidative lipidomics studies, postmortem human brain samples from control and AD patients were obtained from Bank collection of University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hospital of the University of Pittsburgh. All procedures were pre-approved and performed according to the protocols established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee as well as by the Institutional Review Board (human brain samples) of the University of Pittsburgh.

Immunohistochemistry—Mouse brain tissue was fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline. Free floating sagittal or coronal sections, obtained with a Leica VT1000S vibrating microtome, were incubated with 10% hydrogen peroxide in phosphate-buffered saline for 10 min, blocked with 10% goat normal serum for 12 h, and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: polyclonal to human MPO (BioDesign, Int. K50891R, Lee Biosciences RPX-80A, Dako A0398, 1:1000), rat monoclonal to GFAP (Calbiochem, 1:1000), mouse monoclonal to Aβ (Signet 4G8 or 6E10, 1:1000), or rabbit polyclonal antibodies generated against mouse MPO (1:1000). Primary antibodies were detected with biotinylated secondary antibodies and avidinconjugated horseradish peroxidase (Vectastain ABC kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and detected with peroxidase chromogen (SG (peroxidase substrate) or 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole, Vector Laboratories). Confocal images were obtained with fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Alexafluor 488 or 564). All incubations were carried out in phosphate-buffered saline containing 250 mm NaCl and Tween 20 (0.1%).

In Situ Hybridization—In situ hybridization on mouse brain sections was carried out with digoxigenin-labeled MPO RNA antisense probes (Allele Biotechnology, San Diego, CA) and detected with anti-digoxigenin antibodies coupled to alkaline phosphatase (Roche Applied Biosystems) and detected with the nitro blue tetrazolium-5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate color substrate.

HNE ELISA—To measure levels of HNE in mouse cortical extracts, we used the 4-HNE-histidine ELISA kits from Cell Biolabs according to the protocol supplied with the kit. Protein levels were normalized with BCA-protein reagent (Pierce).

Oxidative Lipidomics: Lipid Extraction and Two-dimensional-HPTLC Analysis—Total lipids were extracted from mouse brain using the Folch procedure (40). Lipid extracts were separated and analyzed by two-dimensional high performance TLC (HPTLC) (41). The phospholipid classes in the extracts were separated by two-dimensional-HPTLC on silica G plates (5 × 5 cm, Whatman). The plates were first developed with a solvent system consisting of chloroform:methanol:28% ammonium hydroxide (65:25:5, v/v). After the plate was dried with a forced N2 blower to remove the solvent, it was developed in the second dimension with a solvent system consisting of chloroform:acetone:methanol:glacial acetic acid:water (50:20:10:10:5, v/v). The phospholipids were visualized by exposure to iodine vapors and identified by comparison with authentic phospholipid standards. Lipid phosphorus was determined by a micromethod (42).

Mass Spectra of Phospholipids—The phospholipid mass spectra were analyzed by direct infusion into a linear ion trap mass spectrometer LXQ (Termo Electron, San Jose, CA). Samples after two-dimensional-HPTLC separation were collected, evaporated under N2, re-suspended in chloroform: methanol (1:2, v/v, 20 pmol/μl), and directly used for acquisition of negative-ion ESI mass spectra using a flow rate of 5 μl/min. The electrospray probe was operated at a voltage differential of 5.0 kV in the negative ion mode. Source temperature was maintained at 70 or 150 °C. Mass spectrometry analysis on the ion trap instrument was carried out with a relative collision energy that ranged from 20 to 40% and with an activation q value of 0.25 for CID and a q value of 0.7 for the pulsed-Q dissociation technique. PS molecular species were quantitated by comparing the peak intensities with that of an internal standard (PS17:0/17:0). Isotopic corrections were performed by entering the chemical composition of each species into the Qual browser of Xcalibur (operating system) and using the simulation of the isotopic distribution to make adjustments for the major peaks. Chemical structures of lipid molecular species were confirmed by comparing with the fragmentation patterns presented in Lipid Map Data Base (www.lipidmaps.org).

Total Contents of Lipid Hydroperoxides—The total contents of lipid hydroperoxides in major classes of phospholipids were estimated by fluorescence high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) of products formed in a microperoxidase-11-catalyzed reaction with a fluorogenic substrate, Amplex Red (43). The phospholipid spots on the silica plates were visualized by spraying the plates with deionized water. The spots were then scraped, and phospholipids were extracted by choloroform:methanol:water (20:10:2, v/v). Extracted phospholipids were divided into aliquots for phosphorus measurements and HPLC analysis.

Morris Water Maze—The Morris water maze (44) was performed in a white circular pool (120-cm diameter) with smooth vertical sides, filled with water at 22 °C, made opaque with nontoxic white paint. Spatial cues were located on the walls of the room. The escape platform (10-cm diameter) was 1 cm beneath the surface of the water, and midway between the side and center of the pool. The mice were tracked by a camera fixed to the ceiling for digital recordings of the trials that were analyzed by EthoVision software (Noldus Information Technology, Leesburg, VA). Mice were introduced at one of four positions in semi-random order, excluding the platform quadrant, and the time required to find the hidden platform was determined. Mice were allowed 60 s to find the escape platform and remained on the platform for 20 s. If a mouse failed to find the platform in 60 s, it was placed on the platform for 20 s. Each mouse had four trials per day, separated by 15 min, and the trials continued for 7 to 8 consecutive days. For each experimental group, the time required to find the escape platform for the four trials on each day were averaged to provide mean escape latency. EthoVision software was also used to calculate the percent time spent in the target quadrant.

Statistical Analysis—Student's t test or analysis of variance (with Fisher's post-hoc least significant difference) was used to determine statistical significance using StatView software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). All data are presented as mean ± S.E. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

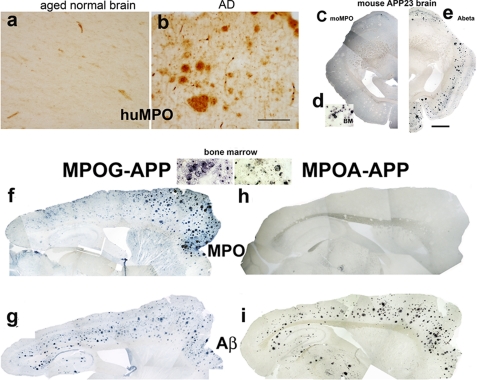

Human MPO Is Expressed in AD, but Mouse MPO Is Not Expressed in the APP23 Model—MPO is virtually absent from normal aged human brain parenchyma (Fig. 1a), yet is present at high levels in some amyloid plaques in AD (Fig. 1b) (14). This finding indicated that certain conditions in AD brain allow aberrant MPO gene expression, raising the possibility that MPO-generated oxidants contribute to AD pathology.

FIGURE 1.

The huMPO-463G transgene is expressed at plaques in the APP23 model, unlike the huMPO-463A transgene or mouse MPO. Cerebral cortex from normal aged human brain (a) and human AD brain (-463G/G genotype) (b) were immunostained with antibodies against human MPO (BioDesign). There was virtually no MPO immunostaining in normal aged brain parenchyma, yet MPO was abundant in plaques in AD brain. Original objective magnification is 4× in a and b. Scale bar = 200 μm. Antibody to Aβ (6E10, Signet) detected cortical plaques in coronal sections of APP23 brain (e). Mouse MPO was not detected in plaques using an antibody against a mouse MPO specific peptide (c), although these antibodies did detect mouse MPO in bone marrow (BM) myeloid precursors (d). Photomontage of overlapping images (4× objective) was assembled with Adobe Photoshop (c and e). Scale bar = 1 mm in e. Sagittal brain sections from MPOG-APP23 (f and g) and MPOA-APP23 (h and i) were immunostained with antibodies against human MPO (f and h) or Aβ (g and i). Aβ antibody (6E10) detected abundant plaques in both MPOG-APP23 and MPOA-APP23 brain (g and i). MPO was present in plaques in MPOG-APP23 (f) but not MPOA-APP23 brain (h). As evidence that the MPOA transgene is functional, the antibody to human MPO (BioDesign) detected the protein in bone marrow myeloid precursors in both MPOG and MPOA mice (inset, bone marrow).

These observations led us to investigate whether the mouse MPO gene was similarly expressed in brain tissue in mouse models of AD that overexpress the human amyloid precursor protein (APP). We examined the APP23 model, which expresses the human APP751 cDNA encoding the Swedish double mutations (APPK670N, M671L) linked to familial early onset AD, and driven by the neuron-specific Thy-1 promoter (19). Aged APP23 mice develop abundant amyloid plaques in the cortex and hippocampus as detected by immunostaining for Aβ (Fig. 1e), but mouse MPO was not detected in these plaques or associated cells (Fig. 1c) using an antibody that detected the protein in bone marrow myeloid precursors (Fig. 1d). As confirmation of this finding, examination of brain sections from another huAPP-overexpressing model, Tg2576, also showed a lack of mouse MPO protein (data not shown). In addition, MPO was not detected in brain from aged wild-type C57Bl6 mice (supplemental Fig. S1A). These observations demonstrate that the mouse MPO gene is not expressed in mouse models of AD, in contrast to human MPO expression in AD tissue.

The Human MPO -463G Allele Is Strongly Expressed in APP23 Brain—The detection of MPO in human AD tissue, but not in APP23 brain, indicates differences between human and mouse MPO promoter elements. Earlier studies suggested this differential expression may be due to the Alu element inserted in the human MPO upstream promoter (20, 22, 23). To examine this possibility, we utilized human MPO transgenic mouse models that carry the intact native human MPO gene with extensive upstream and downstream flanking regions. Independent transgenic lines were generated carrying either the -463G or A allele (MPOG and MPOA). Both transgenes were shown previously to be expressed appropriately and selectively in bone marrow precursors and subsets of reactive macrophages (36).

The huMPO transgenic mice were crossed to the APP23 model to yield double transgenics, MPOG-APP23 and MPOA-APP23. Immunohistochemical analysis of sections from 2-year-old MPOG-APP23 mice revealed abundant amyloid plaques in hippocampus and cortex (Fig. 1g) with dense MPO deposition in plaques in the cortex, especially the frontal cortex (Fig. 1f). MPO was also detected in ramified cells in the cortex and striatum. These findings demonstrated that the human MPOG gene is induced in APP23 brain, unlike the mouse MPO gene.

The Human MPO -463A Allele Is Not Expressed in APP23 Brain—In the MPOA-APP23 cross, amyloid plaques were abundant throughout the cortex and hippocampus (Fig. 1i), but human MPO was not detected (Fig. 1h). This indicated that the -463A site or other sequence difference prevented MPOA allele expression in APP23 brain. As confirmation that the MPOA transgene is indeed functional, human MPO was detected in bone marrow myeloid precursors from MPOA-APP23 and MPOG-APP23 mice (bone marrow, Fig. 1). Moreover, prior studies detected human MPO in bone marrow cells from MPOG and MPOA transgenics crossed onto the mouse MPO knockout strain to eliminate potential signal from the mouse gene (36). In addition, huMPO was previously detected in macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions in both the MPOG-LDLR-/- and MPOA-LDLR-/- crosses (36). These findings indicate that the -463G/A polymorphism or other sequence differences results in selective expression of the human MPO-G allele in APP23 brain.

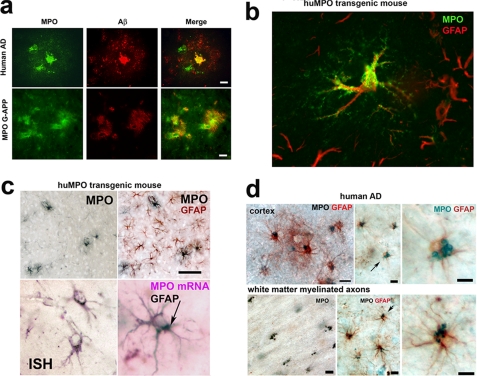

MPO Colocalizes with Aβ in Plaques in Human AD and Transgenic APP23 Brain—Confocal fluorescence microscopy of human AD tissue showed that MPO colocalizes with Aβ. In the example shown in Fig. 2a, MPO colocalizes with Aβ in the core of a plaque and was present in cytoplasmic vesicles in two cells embedded in a halo of Aβ-staining material surrounding the core (Fig. 2a, top panels), consistent with our prior study (14). In the MPOG-APP23 model, MPO similarly colocalized with Aβ in plaques and was detected in the walls of blood vessels traversing the plaques (Fig. 2a, lower panels). These findings showed that MPO is deposited along with Aβ in plaques in huMPO-APP23 brain as in human AD.

FIGURE 2.

MPO is expressed in astrocytes in human AD and in MPOG-APP23 brain. a, colocalization of MPO and Aβ in plaques. Confocal fluorescence microscopy detected MPO (green) in the dense core of a plaque in human AD brain tissue and in cytoplasmic vesicles within two associated cells (top left panel). Aβ (red) was detected in the dense core and in a halo of particulate material (middle panel, top). The merged image (right panel, top) shows colocalization of MPO and Aβ in the plaque core. In the transgenic MPOG-APP23 mice, MPO (left panel, bottom) and Aβ (middle panel, bottom) were detected in plaques, colocalizing in the merged image (right panel, bottom). MPO is also seen in blood vessels traversing the plaques (right and left panels). Scale bars = 20 μm in top row and 50 μm in bottom row. b, MPO is expressed in astrocytes in MPOG-APP23. Confocal image shows punctate MPO immunofluorescent staining (Alexa Fluor 488, green, Molecular Probes) in vesicles throughout a GFAP-positive (Alexa Fluor 594, red) astrocyte. GFAP immunofluorescence was primarily localized to thick projections off the cell body, whereas MPO staining was present in the cell body as well as highly ramified projections. MPO was expressed in only a subset of astrocytes as shown by the several GFAP-positive cells in the background, which lack MPO staining. c, antibodies to MPO (SG, Vector, black) detect only a few ramified cells in a section of MPOG-APP23 cortex, whereas antibodies to GFAP (AEC, red) label these MPO-positive cells along with many other astrocytes in the same section (top row). Scale bar = 70 μm. In situ hybridization (ISH) was carried out with digoxigenin-labeled MPO RNA antisense probes detected with anti-digoxigenin (DIG) antibodies coupled to alkaline phosphatase (Roche Applied Science) and nitro blue tetrazolium-5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate substrate. The DIG-MPO RNA detection signal (purple) labeled cells (bottom left) that also stained with antibodies to GFAP (arrow, bottom right). d, MPO is expressed in astrocytes in human AD. Immunostaining detects human MPO (Vector SG, black) in large vesicles in GFAP-positive (AEC, red) astrocytes around a plaque in AD tissue (top left panel). Middle panel top shows another example of GFAP-positive astrocytes (AEC, red) with a cluster of MPO-positive vesicles (SG, blue-black), more clearly seen at higher magnification of the cell denoted by an arrow (right panel, top). Similar clusters of MPO-positive vesicles were found to be evenly distributed in nearby white matter axonal tracts (left panel, bottom). Costaining for GFAP indicated the vesicles were in astrocytes (middle panel, bottom), and shown more clearly by higher magnification of the cell denoted by arrow (right panel, bottom). Scale bars = 20 μm.

MPOG Is Expressed in Astrocytes in APP23 Mouse Brain—Confocal fluorescence microscopy was used to identify cells expressing human MPO in APP23 brain. Surprisingly, confocal images clearly showed MPO to be present in astrocytes, colocalizing with glial fibrillary associated protein (GFAP) (Fig. 2b). GFAP was predominantly localized to thick projections off the cell body, whereas punctate MPO immunostaining was present throughout the cell body and in finer ramifications. Although the great majority (∼95%) of MPO-positive cells clearly costained for GFAP, only a fraction (∼5%) of GFAP-positive astrocytes costained for MPO, as illustrated by the GFAP-positive astrocyte projections in the background of Fig. 2b, which lack MPO staining. Conventional immunostaining similarly detected MPO in only a subset of GFAP-positive astrocytes (Fig. 2c, top panels). In situ hybridization confirmed the presence of huMPO mRNA in astrocytes that costained for GFAP (Fig. 2c, lower panels). We found no convincing evidence for colocalization of MPO with markers for microglia (CD68, CD11b) or neurons (NeuN), although faint signals were occasionally observed such that this possibility has not been ruled out (data not shown).

MPO Is Expressed in Astrocytes in Human AD Brain—The unexpected finding of MPO in astrocytes in the MPOG-APP23 mouse model led us to investigate whether astrocytes express MPO in human AD brain tissue. Most MPO protein in AD brain is present in extracellular plaques, although earlier studies detected MPO in a few CD68-positive microglia (14) and some neurons (15) in human AD. In the present study, we examined cortical sections from human AD brain tissue for evidence of MPO in astrocytes. Immunohistological analysis detected MPO in GFAP-positive astrocytes in all of the six cases examined. In plaque-laden cortical regions, MPO was present in clustered vesicles in GFAP-positive astrocytes (Fig. 2d, top panels). Similar clusters of MPO-positive vesicles were found evenly distributed in nearby white matter axonal tracts (Fig. 2d, lower panels). Costaining for GFAP showed these vesicles to be present in astrocytes. As in the MPOG-APP23 mouse model, MPO was present in only a subset (<5%) of GFAP-positive astrocytes in plaque-laden regions or associated white matter tracts. These findings demonstrate that MPO is expressed in a subset of astrocytes in human AD as in the MPOG-APP23 model.

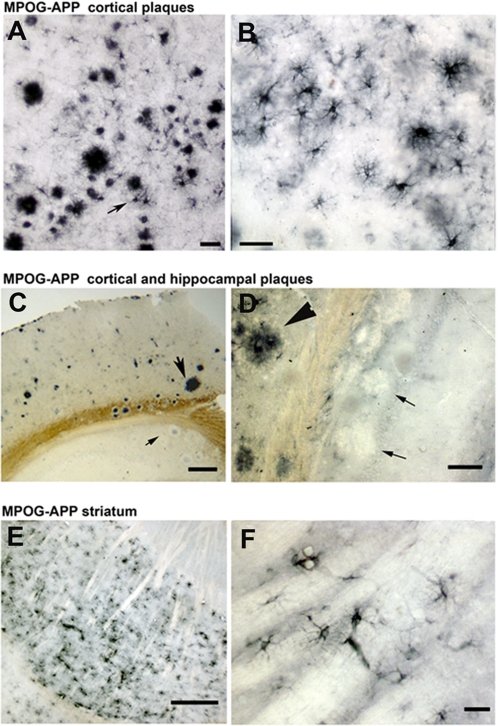

Regional Differences in MPO Expression in APP23 Brain—MPO deposition was not uniform in plaque-laden regions of MPOG-APP23 brain. There were high levels of MPO deposition in plaques and associated astrocytes in the frontal cortex (Fig. 3, A and B), but relatively little MPO in hippocampal plaques (Fig. 3, C and D, and supplemental Fig. S1B), indicating that amyloid deposits are not sufficient to induce MPO expression in plaque-associated astrocytes. Conversely, in the striatum, which generally lacks amyloid deposits, MPO was strongly expressed in astrocytes (Fig. 3, E and F), indicating amyloid deposits are not required for MPO expression at this site. These observations suggest regional differences in agents that induce MPO expression in astrocytes in response to Aβ or other byproducts of APP751 expression.

FIGURE 3.

Spatial differences in huMPO gene expression in MPOG-APP23 brain. Immunostaining detected high levels of human MPO in plaques and associated astrocytes (arrow) in the frontal cortex of MPOG-APP23 brain (A), seen more clearly at higher magnification (B). There was less MPO deposition in plaques in the hippocampus (C, small arrow) than cortical plaques (large arrow), as seen more clearly at higher magnification in another example (D) in which the large arrowhead indicates a cortical plaque with high MPO staining, while two small arrows denote hippocampal plaques with little MPO staining. MPO was also detected in astrocytes in the striatum, a region generally lacking amyloid plaque deposition (E), as shown at higher magnification (F). Scale bars are 60 μm (A), 20 μm (B), 200 μm (C), 50 μm (D), 100 μm (E), and 20 μm (F).

There was preferential expression of MPO in astrocytes with extensions contacting amyloid plaques (Fig. 4, F and H), suggesting that such contact triggers MPO gene expression. In similar fashion, MPO was often detected in astrocytes associated with β-amyloid-positive neurons (Fig. 4G). (The APP751 transgene is expressed in neurons through the Thy-1 promoter.) Astrocytes attached to blood vessels were often MPO-positive (Fig. 4E), possibly reflecting the high levels of cerebrovascular amyloid characteristic of the APP23 model (45). Consistent with this explanation, MPO-positive astrocytes were often observed encircling vessels (Fig. 4C) with amyloid deposits (Fig. 4D). MPO was also deposited in the walls of meningeal vessels (Fig. 4A) in a banding pattern resembling that of Aβ (Fig. 4B), further suggesting that Aβ provokes MPO expression and deposition in vessels. Finally, it is important to note that little to no MPO expression is observed in astrocytes in MPOG mice lacking the APP751 transgene (data not shown and supplemental Fig. S1A), indicating that Aβ or other byproduct is key to this aberrant MPO expression. Together, these findings suggest that Aβ, soluble or insoluble, promotes MPO gene expression in astrocytes, while other spatially restricted agents (cytokines and nuclear receptor ligands) modulate the inducibility of this gene.

FIGURE 4.

Expression of MPO in astrocytes associated with amyloid deposits in plaques or vessels. In MPOG-APP23 brain section, MPO immunostaining (black) presents as a banded pattern in meningeal vessels (A) similar to the banding pattern of β-amyloid as detected with thioflavin-S fluorescence (B). MPO (red) is detected in an astrocyte encircling a blood vessel (C), which contains amyloid detected by thioflavin-S (D). A number of MPO-positive astrocytes are attached along a blood vessel (E). MPO immunostaining detects astrocytic extensions to MPO-positive amyloid plaque (F and H). In panel G, MPO (fluorescent green) is present in an astrocyte contacting a neuron immunostained for Aβ (red). The huAPP751 transgene is expressed in neurons through the neuron specific Thy-1 promoter.

Higher Levels of Peroxidized Phosphatidylserine and Phosphatidylinositol in Human AD and MPOG-APP23 Brain—Oxidative stress is thought to contribute to AD, and MPO is a likely source of reactive oxidants. Unsaturated phospholipids in neuronal tissue are vulnerable to free radical attack leading to lipid peroxidation. We undertook an oxidative lipidomics approach to identify and characterize peroxidized phospholipids in brain. We employed a combination of ESI-MS and fluorescence HPLC techniques to assess the amount of specific phospholipid hydroperoxides in postmortem brain samples from AD patients and controls (supplemental Table S1) and MPOG-APP23 transgenic mice.

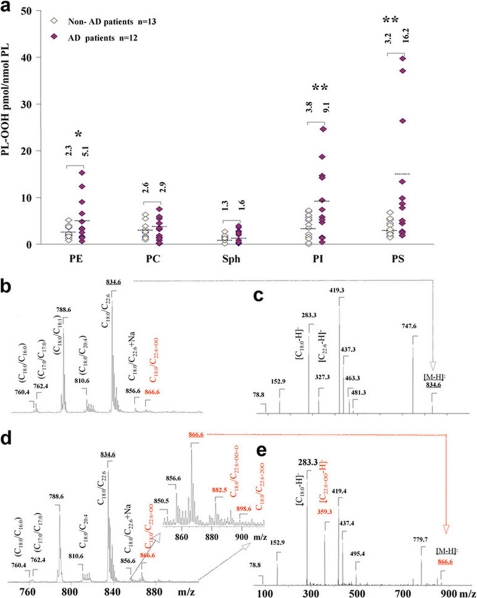

By fluorescence HPLC, we established that the pattern of phospholipid oxidation displayed a non-random character in human AD brain. A robust difference between AD and control brain samples was found in the amounts of phosphatidylserine hydroperoxides (PS-OOH), followed by phosphatidylinositol hydroperoxides (PI-OOH) and phosphatidylethanolamine hydroperoxides (PE-OOH) (Fig. 5a). The contents of PS-OOH and PI-OOH in brain samples from AD patients (n = 12) were 5- and 2.4-fold higher than in controls (n = 13). No significant differences between AD and control samples were detected in the most abundant phospholipid, phosphatidylcholine (PC) as well as in sphingomyelin (SPH).

FIGURE 5.

Increased peroxidation of anionic phospholipids in human AD. a, profiles of hydroperoxides content in major classes of phospholipids in brain samples from non-AD and AD patients. Note that 3-5 times higher levels of hydroperoxides were found in PS and PI from AD brain tissue than non-demented controls (*, p < 0.05 and **, p < 0.01 versus non-demented controls). A 2-fold increase of hydroperoxides was detected in PE from AD brain versus controls. No differences in the content of hydroperoxides between AD and control brain samples were observed in the most abundant phospholipid, PC, as well as in SPH. Patients characteristics are shown in supplemental Table S1. b-e, typical negative ion ESI mass spectra (b and d) and MS-MS spectra (c and e) of PS from postmortem samples from non-AD patients (b and c) and AD patients (d and e). Fragmentation of a major non-oxidized PS species (non-AD sample) with m/z 834 is shown on panel c. MS of an AD sample shows oxidized PS with m/z 866 (d). MS-MS analysis of oxidized PS species (m/z 866) confirmed that it originated from a molecular species of PS with m/z 834 and contained mono-hydroperoxy, C22:6+OO fatty acid (m/z 359). Additionally, other oxidized molecular products with m/z 850, 882, and 898 corresponded to PS molecular species with oxidized C22:6 such as (C18:0/C22:6+O), (C18:0/C22:6+O+OO), and (C18:0/C22:6 + 2OO), respectively.

We used ESI-MS analysis to characterize individual molecular species of oxidizable phospholipids and their oxidation products. A single major molecular ion of PS with m/z 834 was observed using negative ionization mode (Fig. 5, b and c). PS fragmentation yielded a strong peak with m/z 747 due to loss of the serine group. Molecular fragments with m/z 283 and 327 correspond to carboxylate anions of stearic (C18:0) and docosahexaenoic (C22:6) fatty acids, respectively (Fig. 5c). ESI-MS analysis and tandem MS/MS experiments revealed that the major oxidized molecular species of PS was the one with oxidized C22:6 (m/z 866 (C18:0/C22:6+OO) that originated from the ion with m/z 834 (C18:0/C22:6) (Fig. 5, d and e). Other less abundant oxidized molecular species of PS with m/z 850, 882, and 898 formed from PS with C22:6 fatty acid and corresponding to molecular clusters (C18:0/C22:6+O), (C18:0/C22:6+O+OO), and (C18:0/C22:6 + 2OO), respectively, were detected (Fig. 5d). ESI-MS analysis of another oxidized anionic phospholipid, PI, showed that the major molecular ion with m/z 885 corresponded to the species with C18:0/C20:4 fatty acids, which underwent oxidation to yield hydroxy-PI (PI-OH) and hydroperoxy-PI (PI-OOH) with m/z 901 and 917, that corresponded to PI species C18:0/C20:4+O and C18:0/C20:4+OO, respectively (data not shown). ESI-MS and tandem MS/MS experiments revealed that the main products of PE oxidation originated from its diacylated forms (m/z 762; 790 corresponding to C16:0/C22:6- and C18:0/C22:6-containing species, respectively) as well as alkenyl-acyl forms (m/z 722, 728, 748, 772, and 774 corresponding to C16:0p/C20:4, C16:0p/C22:6, C18:1p/C20:4, C18:1p/C22:6, and C18:0p/C22:6, respectively). PE oxidation products with m/z 794 and 822 are signals from C16:0/C22:6+OO and C18:0/C22:6+OO species, respectively. PE oxidation products formed from alkenyl-acyl clusters produced ions with m/z 738, 778, 764, 804, and 806 corresponding to C16:0p/C20:4+O, C16:0p/C22:6+OO, C18:1p/C20:4+O, C18:1p/C22:6+OO, and C18:0p/C22:6+OO, respectively (data not shown).

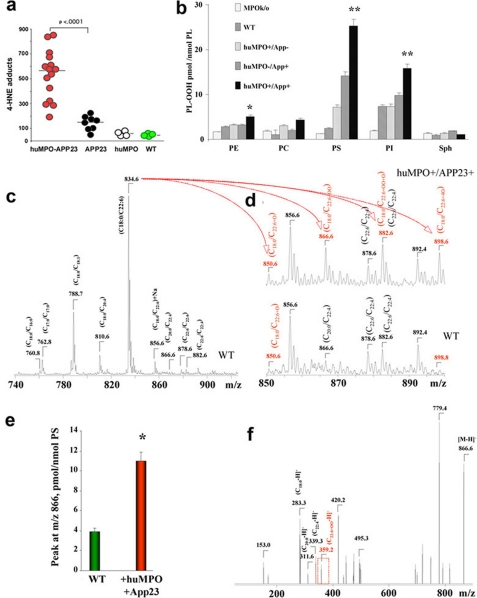

Increased Lipid Peroxidation in Brain Tissue of MPOG-APP23—Lipid peroxides decompose to generate aldehydes such as 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), a neurotoxic product that is increased in serum of AD patients (46). 4-HNE forms stable adducts with proteins, providing an assay for levels of lipid peroxidation in brain tissue. To investigate whether huMPO expression in APP23 brain promotes lipid peroxidation, we performed ELISA assays to compare the levels of 4-HNE in cortical homogenates from MPOG-APP23 (n = 15), APP23 (n = 8), MPOG (n = 4), and wild-type C57Bl6/J mice (n = 4) at 18-20 months of age. Findings revealed a striking increase in 4-HNE in MPOG-APP23 brain as compared with APP23 (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 6a). There was no significant difference in HNE levels between APP23 and wild-type (WT) brain. There was also no increase in HNE in MPOG brain lacking the APP23 transgene, as compared with WT. Thus, the co-expression of huMPO and the human APP transgene led to a marked increase in 4-HNE, a marker of lipid peroxidation.

FIGURE 6.

Increased lipid peroxidation in MPOG-APP23 brain. a, ELISA assays were performed to measure 4-HNE-histidine adducts (CellBIolabs) in frontal cortical extracts from 15 MPOG-APP23 (huMPO-APP), 8 APP23 (APP), 4 MPOG (huMPO), and four wild-type (WT) mice. A significant difference in mean levels of 4-HNE-histidine was found between MPOG-APP23 and APP23 (p < 0.0001). b, profiles of hydroperoxides content in major classes of phospholipids in samples of frontal cortex from wild-type, MPO-knockout, and MPO-APP23 mice. Selective and robust accumulation of PL-OOH in PS and PI from MPOG-APP23 versus WT animals was observed (**, p < 0.01 versus WT brain samples). PE of MPO-APP23 animals contained slightly but significantly elevated levels of hydroperoxides (*, p < 0.05 versus WT brain samples). The contents of PL-OOH in the most abundant phospholipid, PC, as well as in SPH was not significantly different between the groups. c-f, typical negative-ion ESI mass spectra of PS molecular species in WT and MPOG-APP23. The dominant molecular ion of PS had a signal with m/z 834 corresponding to a PS species containing C18:0/C22:6 fatty acids. Molecular ions of PS with m/z 760, 788, and 810 correspond to its individual species containing C18:0/C16:0, C18:0/C18:1, and C18:0/C20:4 fatty acids, respectively. Major oxidized molecular species of PS with m/z 866, containing C18:0/C22:6+OO was detected in MPOG-APP23 brain homogenates. This dominant product was produced by oxidation of PS species with m/z 834 (C18:0/C22:6). Additionally, other oxidized species with m/z 850, 882, and 898, formed from PS containing C22:6 fatty acid, corresponded to molecular clusters (C18:0/C22:6+O), (C18:0/C22:6+O+OO), and (C18:0/C22:6 + 2OO), respectively. Note that MS/MS fragmentation analysis showed that signals with m/z at 866 and 882 in MPOG samples included both non-oxidized PS species (C20:0/C22:4 and C22:6/C22:4, respectively) as well as oxidized PS species (C18:0/C22:6+OO and C18:0/C22:6+O+OO, respectively). In MPOG samples, the oxidized PS species were quantitatively predominant and accountable for more than 70% of these signals. In WT samples, theses signals did not contain oxidized PS species and contained only non-oxidized species C20:0/C22:4 and C22:6/C22:4, respectively. In e, *, p < 0.01 for comparison of m/z 866 peak for huMPO-APP versus WT sample.

As in the analysis of human AD brain tissue in Fig. 5, we also employed a combination of ESI-MS and fluorescence HPLC techniques to analyze the oxidation of phospholipids in the mouse models, comparing MPOG-APP23 to APP23 mice (n = 4 per group), as well as MPO knockout and wild-type C57Bl6 mice (Fig. 6, b-f). Fluorescence HPLC assessments showed selective oxidation of PS with the highest level of PS-OOH in extracts of frontal cortices in MPOG-APP23 mice (Fig. 6b); the decreasing order of PS-OOH contents was found in APP23, MPOG (lacking APP23), wild-type, and MPO knockout mice. Among different phospholipid classes, levels of hydroperoxides (PL-OOH) decreased in the order PS > PI ≫ PE; very low, not significantly different between different groups of animals, amounts of PL-OOH were detected in PC and SPH (Fig. 6b).

As in human AD brain samples, ESI-MS and tandem MS/MS analysis revealed that PS with oxidized C22:6 (m/z 866 (C18:0/C22:6+OO)) originating from the ion at m/z 834 (C18:0/C22:6) was the major oxidized molecular species (see the signal of C22:6+OO with m/z 359.3) (Fig. 6, c-f). The highest intensity of this signal was detected in MPOG/APP23 mice, a 3-fold increase compared with WT animals (Fig. 6e). Note that additional PS oxidation products with m/z 882 and 898 containing hydroperoxy groups (2O) plus hydroxy groups (O) and di-hydroperoxy groups (4O), respectively, were also detectable. MS analysis of PI showed that MPO-APP23 brain contained oxidized molecular species with m/z 901 and 917 corresponding to PI-OH and PI-OOH corresponding to the dominant species containing C18:0/C20:4+O and C18:0/C20:4+OO. These oxidation products were formed by oxidation of the PI molecular species with ion at m/z 885 (C18:0/C20:4) (data not shown). Overall, these oxidative lipidomics findings provide the first evidence for the similarity of MPO catalyzed selective oxidation of PS and PI in the MPOG-APP23 mouse model with that occurring in human AD brain.

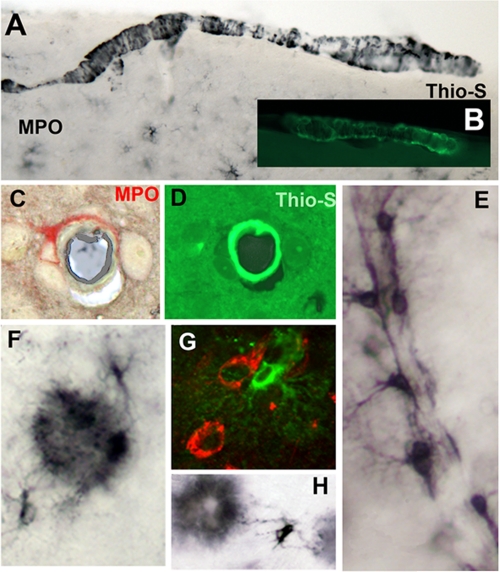

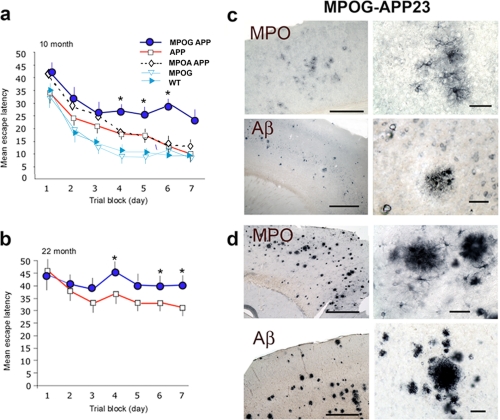

MPOG-APP23 Mice Exhibit Greater Spatial Memory Impairment in Water Maze Experiments—We investigated the possibility that MPO-generated oxidants affect neuronal function in the mouse model of AD. To assess effects of MPO-oxidants on spatial memory, Morris water maze experiments were carried out comparing MPOG-APP23 (n = 8), MPOAAPP23 (n = 8), and APP23 mice (n = 7) at 10 or 22 months of age, along with MPOG (n = 8) and wild-type controls (n = 9). At 10 months, there were few plaques immunostaining for Aβ or MPO (Fig. 7c), but MPO was expressed in clusters of astrocytes in the cortex (Fig. 7c, upper panels). This indicated that MPO expression occurs in astrocytes prior to significant amyloid plaque deposition.

FIGURE 7.

Greater spatial memory deficits in MPOG-APP23 mice. a, hidden platform Morris water maze experiments were carried out with MPOG-APP23 (n = 8), APP23 (n = 7), MPOA-APP23 (n = 8), MPOG (n = 8), and C57BL6 (WT) (n = 9) mice at age 10 ± 1.2 months. Each data point represents mean escape latency (seconds) ± S.E. for the combined latency of four daily trials. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*, p < 0.05) between control APP23 and MPOG-APP23 values as determined by analysis of variance (Fisher's post-hoc least significant difference). The MPOG-APP23 exhibited significantly greater escape latency than APP23 controls on days 4-7. b, Morris water maze experiments were conducted with MPOG-APP23 (n = 9) and APP23 (n = 8), mice at 22 ± 1.8 months of age. Asterisks indicate significant differences between escape latency for MPOG-APP23 and APP23 controls on days 4, 6, and 7. c, MPO immunostaining of frontal cortex of MPOG-APP23 shows clusters of MPO-positive astrocytes with few MPO-positive plaques at 10 months of age (top row). A higher magnification of an astrocyte cluster in a region of the left panel is shown in the right panel. Scale bars = 200 μm (left top panel), and 25 μm (right top panel). Aβ immunostaining (6E10) shows few amyloid deposits at 10 months of age in MPOG-APP23 brain (lower panels). A region in the left panel is shown at higher magnification in the right panel. d, at 22 ± 1.8 months of age, MPO was densely deposited in plaques in the frontal cortex (top panels), as was Aβ (lower panels). Right panels show higher magnification of areas in left panels. Scale bars = 200 μm (left panels) and 25 μm (right panels).

The maze was carried out as detailed under “Experimental Procedures.” Briefly, the mice were introduced into a pool of opaque water and allowed up to 60 s to find a hidden escape platform. Escape latency refers to the average time required to find the platform. Over the 7-day testing period, the average escape latency for the APP23 mice declined from 35 to 10 s (Fig. 7a). The MPOG-APP23 mice required significantly more time to find the platform, with mean escape latency declining from 44 to 25 s. The MPOAAPP23 mice were not significantly different from APP23 in escape latency, whereas MPOG mice lacking the APP23 transgene were equivalent to wild-type C57BL6 mice in escape latency (Fig. 7a). These findings link MPOG expression in astrocytes to spatial memory impairment in APP23 mice at 10 months of age when MPO is expressed in clusters of cortical astrocytes, yet prior to significant amyloid plaque deposition. It should be noted that no differences were seen between MPOG, MPOA, and wild-type mice lacking the APP23 transgene when these mice were tested for spatial memory in the maze.

Water maze experiments were also carried out with MPOG-APP23 (n = 9) and APP23 mice (n = 8) at 22 months of age (Fig. 7b). Immunohistological studies revealed abundant amyloid plaques (Fig. 7d, lower panels) with heavy deposition of MPO (Fig. 7d, upper panels). At this advanced age, mean escape latency increased for both groups, but latency remained significantly greater for the MPOG-APP23 mice than APP23 controls (Fig. 7b). Thus, MPOG expression correlated with greater spatial memory impairment in 22-month-old MPOG-APP23 mice with abundant amyloid plaques and dense MPO deposits.

DISCUSSION

The central findings of this study include the discovery that the human MPO -463G allele is aberrantly induced in astrocytes in the APP23 mouse model, and that MPO is aberrantly expressed in astrocytes in human AD brain. Second, MPO expression in APP23 brain promotes lipid peroxidation as shown by significant increases in 4-hydroxynonenal and oxidized anionic phospholipids, notably PS and PI. Finally, huMPO expression in the huAPP mouse model leads to greater memory deficits. These results support a model in which the induction of huMPO expression in astrocytes promotes oxidative damage, which contributes to neuronal damage and cognitive decline.

A number of hypotheses have been proposed to explain AD pathogenesis, including β-amyloid-induced toxicity (47), free radical-mediated oxidative stress (2), and inflammation (48). It is unclear which of these are most important or more involved in the initiation of the process. Results presented here suggest that oxidative stress is an important contributing factor to the development of AD. Oxidation can be manifested by an increase in lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, or DNA and RNA oxidation (reviewed in Ref. 4). Our findings suggest that MPO-generated oxidants contribute significantly to lipid peroxidation, which is likely to contribute to neurological dysfunction in AD. Markedly higher levels of 4-HNE were detected in brain extracts from MPOG-APP23 mice as compared with APP23 mice. In addition, mass spectrometry and fluorescence HPLC detected higher levels of oxidized anionic phospholipids PS and PI, particularly PS, in MPOG-APP23 brain, correlating with increased levels of oxidized PS-OOH and PI oxidation products in postmortem brain samples from AD patients. Strikingly, accumulation of the same individual molecular species of PS-OOH and PI-OOH was characteristic of brain samples from AD patients and MPOG-APP23 mice.

Why does MPO preferentially oxidize PS rather than other more abundant lipids? As an anionic phospholipid, phosphatidylserine confers negative charge to the sites of its location in membranes. Surface charge distribution and the presence of positively charged domains in MPO have been associated with its predominant binding to negatively charged proteins and confinement to negatively charged sites (49, 50). Recently, binding of MPO to externalized PS on the surface of apoptotic cells has been demonstrated (51). It is tempting to speculate that aberrant expression of huMPO in AD brain and in MPOG-APP23 brain leads to preferred binding to sites in the internal membrane leaflet enriched with negatively charged PS. Oxidized PS would then be transferred to the outer membrane leaflet where it serves as an apoptotic marker to macrophages. Oxidation and externalization of PS could alter membrane dynamics in astrocytes, interfering with the ability of these glial cells to supply neurons with cholesterol and glucose, potentially contributing to neuronal dysfunction in AD. Another possibility is that extracellularly released MPO is taken up by neurons as suggested by the presence of MPO in some neurons in AD brain (15). MPO is known to bind surface receptors on vascular endothelial cells leading to internalization (50, 52) and an increase in intracellular oxidants (53). Internalization of MPO decreases the bioavailability of nitric oxide, inhibiting vasodilation and vascular signaling (54, 55). MPO may similarly be internalized by neurons, leading to oxidative damage and the externalization of PS. An increase in externalized PS has been found in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and AD (5). It should be noted that PS is present in very low amounts in mitochondria due to its effective decarboxylation (56-58). Therefore selective and robust PS peroxidation in AD patients' brain and in MPOG-APP23 mice is not likely to result from mitochondrial production of ROS thus emphasizing the role of MPO as the major source of PS oxidation.

It is interesting that MPOG-APP23 brain exhibited a significant increase in the levels of 4-HNE, an aldehyde product of lipid peroxidation. 4-HNE is a reactive aldehyde that covalently modifies proteins by forming adducts with cysteine, lysine, or histidine residues. 4-HNE is also a neurotoxin that is elevated in multiple brain regions in AD patients, and in ventricular fluid and amyloid deposits, as compared with controls (59-63). Levels of 4-HNE are also increased in mild cognitive impairment brain as compared with normal subjects (64, 65), suggesting this is an early event in AD. Similarly, in the MPOG-APP23 model, increases in 4-HNE were an early event, occurring when MPO was expressed in clusters of cortical astrocytes, prior to significant plaque deposition, yet coincident with the onset of memory deficits.

Cardiovascular disease is thought to exacerbate AD by impairing the supply of oxygen and nutrients to neuronal tissue. MPO is strongly implicated in atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease (18, 37, 66). In the LDLR-/- model of atherosclerosis, huMPO expression increased atherosclerosis along with increased protein oxidation in lesions (36, 37). The mechanism by which MPO promotes atherosclerosis involves oxidation of LDL, which enhances its uptake by macrophage scavenger receptors to create foam cells (67). Also, MPO-oxidation of the apoA1 component of HDL impairs ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux from foam cells (66, 68, 69). In the nervous system, apoE is the principal apoprotein component of high density lipoprotein-like particles involved in transport of cholesterol from astrocytes to neurons. Astrocytes are the major producer of apoE and cholesterol in nervous tissue, and as shown here, a producer of MPO in APP23 and AD brain. ApoE4, the major genetic risk factor for AD, is preferentially oxidized by MPO, as compared with apoE3 or apoE2 (14). These observations suggest another possible mechanism to explain the MPO-dependent decline in spatial memory in MPOG-APP23 mice. Oxidation of apoE by MPO in astrocytes may impair cholesterol transport to neurons, thus inhibiting neuronal sprouting, repair, or synaptic maturation (70, 71). In support of this concept, some genetic association studies have suggested a synergism between the MPO -463G/A polymorphism and apoE4 in AD risk (14, 24).

It was surprising to find robust expression of huMPO in astrocytes in MPOG-APP23 brain as well as human AD tissue. In normal circumstances, MPO expression is restricted to bone marrow myeloid precursors and subsets of reactive monocytemacrophages at inflammatory sites (36). Prior studies have detected MPO in occasional microglia (14) and neurons in AD brain (15) and in astrocytes in Parkinson disease (72). The mouse MPO gene was not expressed in APP23 brain, indicating that human-specific promoter elements are required for the induction of MPO gene expression, such as the primate-specific Alu element with SP1 and nuclear receptor binding sites. As evidence that the Alu sites are important in this regard, the MPOA transgene with the -463A base change in the Alu was completely inactive in MPOA-APP23 brain. This finding suggests that the -463G/A site is key to binding of transcription regulators that allow expression of the MPOG transgene while disallowing MPOA expression (32-35). Prior studies showed that this polymorphism results in preferred binding of the SP1 transcription factor to the -463G site (20) and estrogen receptor to the -463A site (22). The -463G allele has been found to be higher expressing than the -463A allele in human and MPOG mouse monocyte-macrophages (36). The higher expressing GG genotype was previously found to be associated with higher levels of MPO in amyloid plaques in male AD cases as compared with GA/AA cases (14). Several genetic association studies have linked the -463G/A polymorphism to risk for AD (14, 24, 25, 27, 73) or cognitive decline in aging patients (25).

The absence of mouse MPO expression in APP23 brain may be due to the lack of the primate specific Alu element with multiple transcription factor binding sites. The lack of mouse MPO expression may be one reason for the lower level of neuronal cell loss in huAPP-overexpressing mouse models as compared with human AD.

The insertion of the primate-specific Alu element may allow the human MPO gene to escape regulatory mechanisms, which normally inhibit MPO expression in cells other than myeloid precursors. The Alu-encoded transcription factor binding sites may permit aberrant human MPO expression in astrocytes in AD or Parkinson disease (72), microglia (14), or neurons in AD (15), macrophages in atherosclerosis lesions (36), or hepatocytes in hyperlipidemic conditions (36). These Alu-encoded sites may have conferred a selective advantage in ancient populations by allowing up-regulation of MPO at sites of infection. Unfortunately, these Alu sites have a deleterious impact in present day populations with longer lifespans by allowing induction of MPO in chronic inflammatory states such as AD or atherosclerosis. The Alu-enabled induction of MPO expression in reactive cells may thus have contributed to major chronic inflammatory states afflicting modern humans.

There are at present no effective means to slow the advance of AD. Findings here raise the possibility of a novel therapeutic approach aimed at suppression of MPO gene expression or enzyme activity. As examples, statins (38) and liver X receptor ligands (21) reduce MPO mRNA expression, potentially explaining the protection provided by these agents in AD patients or mouse models of AD (74-76).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The APP23 mouse model was generously provided by Matthias Staufenbiel (Novartis Pharma, Switzerland).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AG-017879, HL088428 (to W.R.), and AG026539 (to V. K.). This work was also supported by the Pennsylvania Dept. of Health (Grant SAP 4100027294 to V. K.). Human brain tissue samples were generously provided by the Harvard Brain Repository, which is supported by PHS Grant R24-MH068855, and also by Douglas Walker (Sun Health Research Institute), Eliezer Masliah, and Lawrence Hansen (University of California at San Diego). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1 and Table S1.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: AD, Alzheimer disease; Aβ, amyloid β; MPO, myeloperoxidase; LDL, low density lipoprotein; hu, human; GFAP, glial fibrillary associated protein; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HPTLC, high-performance TLC; ESI, electrospray ionization; MS, mass spectrometry; MS/MS, tandem MS; CID, collision-induced dissociation; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; APP, amyloid precursor protein; PS, phosphatidylserine; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PC, phosphatidylcholine; SPH, sphingomyelin; 4-HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal; WT, wild type.

References

- 1.Nunomura, A., Perry, G., Aliev, G., Hirai, K., Takeda, A., Balraj, E. K., Jones, P. K., Ghanbari, H., Wataya, T., Shimohama, S., Chiba, S., Atwood, C. S., Petersen, R. B., and Smith, M. A. (2001) J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 60 759-767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovell, M. A., and Markesbery, W. R. (2007) J. Neurosci. Res. 85 3036-3040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lovell, M. A., and Markesbery, W. R. (2008) Neurobiol. Dis. 29 169-175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markesbery, W. R., and Lovell, M. A. (2007) Arch. Neurol. 64 954-956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bader Lange, M. L., Cenini, G., Piroddi, M., Abdul, H. M., Sultana, R., Galli, F., Memo, M., and Butterfield, D. A. (2008) Neurobiol. Dis. 29 456-464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keller, J. N., Schmitt, F. A., Scheff, S. W., Ding, Q., Chen, Q., Butterfield, D. A., and Markesbery, W. R. (2005) Neurology 64 1152-1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Picklo, M. J., Montine, T. J., Amarnath, V., and Neely, M. D. (2002) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 184 187-197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markesbery, W. R., Kryscio, R. J., Lovell, M. A., and Morrow, J. D. (2005) Ann. Neurol. 58 730-735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sultana, R., Boyd-Kimball, D., Poon, H. F., Cai, J., Pierce, W. M., Klein, J. B., Merchant, M., Markesbery, W. R., and Butterfield, D. A. (2006) Neurobiol. Aging 27 1564-1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreira, P. I., Honda, K., Liu, Q., Santos, M. S., Oliveira, C. R., Aliev, G., Nunomura, A., Zhu, X., Smith, M. A., and Perry, G. (2005) Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2 403-408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castellani, R., Hirai, K., Aliev, G., Drew, K. L., Nunomura, A., Takeda, A., Cash, A. D., Obrenovich, M. E., Perry, G., and Smith, M. A. (2002) J. Neurosci. Res. 70 357-360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varadarajan, S., Yatin, S., Aksenova, M., and Butterfield, D. A. (2000) J. Struct. Biol. 130 184-208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bush, A. I., and Curtain, C. C. (2008) Eur. Biophys. J. 37 241-245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reynolds, W. F., Rhees, J., Maciejewski, D., Paladino, T., Sieburg, H., Maki, R. A., and Masliah, E. (1999) Exp. Neurol. 155 31-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green, P. S., Mendez, A. J., Jacob, J. S., Crowley, J. R., Growdon, W., Hyman, B. T., and Heinecke, J. W. (2004) J. Neurochem. 90 724-733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klebanoff, S. J. (2005) J. Leukocyte Biol. 77 598-625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinecke, J. W. (2002) Toxicology 177 11-22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang, R., Brennan, M. L., Shen, Z., MacPherson, J. C., Schmitt, D., Molenda, C. E., and Hazen, S. L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 46116-46122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sturchler-Pierrat, C., Abramowski, D., Duke, M., Wiederhold, K. H., Mistl, C., Rothacher, S., Ledermann, B., Burki, K., Frey, P., Paganetti, P. A., Waridel, C., Calhoun, M. E., Jucker, M., Probst, A., Staufenbiel, M., and Sommer, B. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94 13287-13292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piedrafita, F. J., Molander, R. B., Vansant, G., Orlova, E. A., Pfahl, M., and Reynolds, W. F. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 14412-14420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reynolds, W. F., Kumar, A. P., and Piedrafita, F. J. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 349 846-854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar, A. P., Piedrafita, F. J., and Reynolds, W. F. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 8300-8315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vansant, G., and Reynolds, W. F. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92 8229-8233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds, W. F., Hiltunen, M., Pirskanen, M., Mannermaa, A., Helisalmi, S., Lehtovirta, M., Alafuzoff, I., and Soininen, H. (2000) Neurology 55 1284-1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pope, S. K., Kritchevsky, S. B., Ambrosone, C., Yaffe, K., Tylavsky, F., Simonsick, E. M., Rosano, C., Stewart, S., and Harris, T. (2006) Am. J. Epidemiol. 163 1084-1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zappia, M., Manna, I., Serra, P., Cittadella, R., Andreoli, V., La Russa, A., Annesi, F., Spadafora, P., Romeo, N., Nicoletti, G., Messina, D., Gambardella, A., and Quattrone, A. (2004) Arch. Neurol. 61 341-344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leininger-Muller, B., Hoy, A., Herbeth, B., Pfister, M., Serot, J. M., Stavljenic-Rukavina, M., Massana, L., Passmore, P., Siest, G., and Visvikis, S. (2003) Neurosci. Lett. 349 95-98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoy, A., Leininger-Muller, B., Kutter, D., Siest, G., and Visvikis, S. (2002) Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 40 2-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikpoor, B., Turecki, G., Fournier, C., Theroux, P., and Rouleau, G. A. (2001) Am. Heart J. 142 336-339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Makela, R., Karhunen, P. J., Kunnas, T. A., Ilveskoski, E., Kajander, O. A., Mikkelsson, J., Perola, M., Penttila, A., and Lehtimaki, T. (2003) Lab. Invest. 83 919-925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asselbergs, F. W., Reynolds, W. F., Cohen-Tervaert, J. W., Jessurun, G. A., and Tio, R. A. (2004) Am. J. Med. 116 429-430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahn, J., Ambrosone, C. B., Kanetsky, P. A., Tian, C., Lehman, T. A., Kropp, S., Helmbold, I., von Fournier, D., Haase, W., Sautter-Bihl, M. L., Wenz, F., and Chang-Claude, J. (2006) Clin. Cancer Res. 12 7063-7070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahn, J., Gammon, M. D., Santella, R. M., Gaudet, M. M., Britton, J. A., Teitelbaum, S. L., Terry, M. B., Neugut, A. I., Josephy, P. D., and Ambrosone, C. B. (2004) Cancer Res. 64 7634-7639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schabath, M. B., Spitz, M. R., Hong, W. K., Delclos, G. L., Reynolds, W. F., Gunn, G. B., Whitehead, L. W., and Wu, X. (2002) Lung Cancer (Amst.) 37 35-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cascorbi, I., Henning, S., Brockmoller, J., Gephart, J., Meisel, C., Muller, J. M., Loddenkemper, R., and Roots, I. (2000) Cancer Res. 60 644-649 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castellani, L. W., Chang, J. J., Wang, X., Lusis, A. J., and Reynolds, W. F. (2006) J. Lipid Res. 47 1366-1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, Z., Nicholls, S. J., Rodriguez, E. R., Kummu, O., Horkko, S., Barnard, J., Reynolds, W. F., Topol, E. J., DiDonato, J. A., and Hazen, S. L. (2007) Nat. Med. 13 1176-1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar, A. P., and Reynolds, W. F. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 331 442-451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar, A. P., Ryan, C., Cordy, V., and Reynolds, W. F. (2005) Nitric Oxide 13 42-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Folch, J., Lees, M., and Sloane Stanley, G. H. (1957) J. Biol. Chem. 226 497-509 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kagan, V. E., Ritov, V. B., Tyurina, Y. Y., and Tyurin, V. A. (1998) Methods Mol. Biol. 108 71-87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bottcher, C. S. F., Van Gent, C. M., and Fries, C. (1961) Anal. Chim. Acta 24 203-204 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kagan, V. E., Tyurin, V. A., Jiang, J., Tyurina, Y. Y., Ritov, V. B., Amoscato, A. A., Osipov, A. N., Belikova, N. A., Kapralov, A. A., Kini, V., Vlasova, II, Zhao, Q., Zou, M., Di, P., Svistunenko, D. A., Kurnikov, I. V., and Borisenko, G. G. (2005) Nat. Chem. Biol. 1 223-232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morris, R. (1984) J. Neurosci. Methods 11 47-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calhoun, M. E., Burgermeister, P., Phinney, A. L., Stalder, M., Tolnay, M., Wiederhold, K. H., Abramowski, D., Sturchler-Pierrat, C., Sommer, B., Staufenbiel, M., and Jucker, M. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 14088-14093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGrath, L. T., McGleenon, B. M., Brennan, S., McColl, D., Mc, I. S., and Passmore, A. P. (2001) QJM 94 485-490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Selkoe, D. J. (1991) Neuron 6 487-498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akiyama, H., Barger, S., Barnum, S., Bradt, B., Bauer, J., Cole, G. M., Cooper, N. R., Eikelenboom, P., Emmerling, M., Fiebich, B. L., Finch, C. E., Frautschy, S., Griffin, W. S., Hampel, H., Hull, M., Landreth, G., Lue, L., Mrak, R., Mackenzie, I. R., McGeer, P. L., O'Banion, M. K., Pachter, J., Pasinetti, G., Plata-Salaman, C., Rogers, J., Rydel, R., Shen, Y., Streit, W., Strohmeyer, R., Tooyoma, I., Van Muiswinkel, F. L., Veerhuis, R., Walker, D., Webster, S., Wegrzyniak, B., Wenk, G., and Wyss-Coray, T. (2000) Neurobiol. Aging 21 383-421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yeung, T., Gilbert, G. E., Shi, J., Silvius, J., Kapus, A., and Grinstein, S. (2008) Science (New York) 319 210-213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baldus, S., Eiserich, J. P., Mani, A., Castro, L., Figueroa, M., Chumley, P., Ma, W., Tousson, A., White, C. R., Bullard, D. C., Brennan, M. L., Lusis, A. J., Moore, K. P., and Freeman, B. A. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 108 1759-1770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lessig, J., Spalteholz, H., Reibetanz, U., Salavei, P., Fischlechner, M., Glander, H. J., and Arnhold, J. (2007) Apoptosis 12 1803-1812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Astern, J. M., Pendergraft, W. F., 3rd, Falk, R. J., Jennette, J. C., Schmaier, A. H., Mahdi, F., and Preston, G. A. (2007) Am. J. Pathol. 171 349-360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang, J. J., Preston, G. A., Pendergraft, W. F., Segelmark, M., Heeringa, P., Hogan, S. L., Jennette, J. C., and Falk, R. J. (2001) Am. J. Pathol. 158 581-592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang, R., Brennan, M. L., Fu, X., Aviles, R. J., Pearce, G. L., Penn, M. S., Topol, E. J., Sprecher, D. L., and Hazen, S. L. (2001) J. Am. Med. Assoc. 286 2136-2142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eiserich, J. P., Baldus, S., Brennan, M. L., Ma, W., Zhang, C., Tousson, A., Castro, L., Lusis, A. J., Nauseef, W. M., White, C. R., and Freeman, B. A. (2002) Science (New York) 296 2391-2394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steenbergen, R., Nanowski, T. S., Beigneux, A., Kulinski, A., Young, S. G., and Vance, J. E. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 40032-40040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Modi, H. R., Katyare, S. S., and Patel, M. A. (2008) J. Membrane Biol. 221 51-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kiebish, M. A., Han, X., Cheng, H., Lunceford, A., Clarke, C. F., Moon, H., Chuang, J. H., and Seyfried, T. N. (2008) J. Neurochem. 106 299-312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Markesbery, W. R., and Lovell, M. A. (1998) Neurobiol. Aging 19 33-36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Butterfield, D. A., Poon, H. F., St Clair, D., Keller, J. N., Pierce, W. M., Klein, J. B., and Markesbery, W. R. (2006) Neurobiol. Dis. 22 223-232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Annangudi, S. P., Deng, Y., Gu, X., Zhang, W., Crabb, J. W., and Salomon, R. G. (2008) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 21 1384-1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sompol, P., Ittarat, W., Tangpong, J., Chen, Y., Doubinskaia, I., Batinic-Haberle, I., Abdul, H. M., Butterfield, D. A., and St Clair, D. K. (2008) Neuroscience 153 120-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ando, Y., Brannstrom, T., Uchida, K., Nyhlin, N., Nasman, B., Suhr, O., Yamashita, T., Olsson, T., El Salhy, M., Uchino, M., and Ando, M. (1998) J. Neurol. Sci. 156 172-176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Williams, T. I., Lynn, B. C., Markesbery, W. R., and Lovell, M. A. (2006) Neurobiol. Aging 27 1094-1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Butterfield, D. A., Reed, T., Perluigi, M., De Marco, C., Coccia, R., Cini, C., and Sultana, R. (2006) Neurosci. Lett. 397 170-173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zheng, L., Nukuna, B., Brennan, M. L., Sun, M., Goormastic, M., Settle, M., Schmitt, D., Fu, X., Thomson, L., Fox, P. L., Ischiropoulos, H., Smith, J. D., Kinter, M., and Hazen, S. L. (2004) J. Clin. Invest. 114 529-541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Podrez, E. A., Febbraio, M., Sheibani, N., Schmitt, D., Silverstein, R. L., Hajjar, D. P., Cohen, P. A., Frazier, W. A., Hoff, H. F., and Hazen, S. L. (2000) J. Clin. Invest. 105 1095-1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu, Z., Wagner, M. A., Zheng, L., Parks, J. S., Shy, J. M., 3rd, Smith, J. D., Gogonea, V., and Hazen, S. L. (2007) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14 861-868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Borisenko, G. G., Matsura, T., Liu, S. X., Tyurin, V. A., Jianfei, J., Serinkan, F. B., and Kagan, V. E. (2003) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 413 41-52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mauch, D. H., Nagler, K., Schumacher, S., Goritz, C., Muller, E. C., Otto, A., and Pfrieger, F. W. (2001) Science (New York) 294 1354-1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koudinov, A. R., and Koudinova, N. V. (2001) FASEB J. 15 1858-1860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Choi, D. K., Pennathur, S., Perier, C., Tieu, K., Teismann, P., Wu, D. C., Jackson-Lewis, V., Vila, M., Vonsattel, J. P., Heinecke, J. W., and Przedborski, S. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25 6594-6600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Crawford, F. C., Freeman, M. J., Schinka, J. A., Morris, M. D., Abdullah, L. I., Richards, D., Sevush, S., Duara, R., and Mullan, M. J. (2001) Exp. Neurol. 167 456-459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wolozin, B., Kellman, W., Ruosseau, P., Celesia, G. G., and Siegel, G. (2000) Arch. Neurol. 57 1439-1443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rockwood, K., Kirkland, S., Hogan, D. B., MacKnight, C., Merry, H., Verreault, R., Wolfson, C., and McDowell, I. (2002) Arch. Neurol. 59 223-227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zelcer, N., Khanlou, N., Clare, R., Jiang, Q., Reed-Geaghan, E. G., Landreth, G. E., Vinters, H. V., and Tontonoz, P. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 10601-10606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.