Abstract

In many instances, the encounter between host and microbial cells can be, through a longstanding evolutionary association, a balanced interaction whereby both cell types co-exist and inflict a minimal degree of harm on each other. In the oral cavity, despite the presence of large numbers of diverse organisms, health is the most frequent status. Disease will only ensue when the host-microbe balance is disrupted on a cellular and molecular level. With the advent of microarrays, it is now possible to monitor the responses of host cells to bacterial challenge in a global scale. However, microarray data are known to be inherently noisy, which is caused in part by their great sensitivity. Hence, we will address a number of important general considerations required to maximize the significance of microarray analysis in order to faithfully depict relevant host-microbe interactions. Several advantages and limitations of microarray analysis that may directly impact the significance of array data are highlighted and discussed. Further, this review revisits and contextualizes recent transcriptional profiles that were originally generated to specifically study intricate cellular interactions between gingival cells and four important plaque microorganisms. This is, to our knowledge, the first report that systematically investigates the cellular responses of a cell line to challenge by 4 different microorganisms. Of particular relevance to the oral cavity, the model bacteria span the entire spectrum of documented pathogenic potential from commensal to opportunistic to overtly pathogenic. These studies provide a molecular basis of the complex and dynamic interaction between the oral microflora and its host, which may lead, in the long run, to the development of novel, rational and practical therapeutic, prophylactic and diagnostic applications.

Keywords: microarray, transcriptional profiling, oral epithelium, commensal, pathogen, transcriptomic

Introduction

The human oral cavity is a complex ecosystem that contains a large number of bacterial colonizers that thrive in a dynamic environment. Since health is the most common state of a host, it has been speculated that the autochthonous flora and the host have co-evolved and interact in a balanced fashion that is beneficial to both the host and the microbiota (Marsh 2003). Although such benefits are not well defined in the oral cavity, in an analogous situation, indigenous bacteria of the GI tract provide an appreciable number of documented benefits to the host including, for example, the generation of simplified carbohydrates, amino acids and vitamins; the prevention of infection by pathogens through direct competition for niches or by immune cross-reactivity; the stimulation of vascularization and development of intestinal vili; and the enhancement of the normal development of the immune system (Gilmore and Ferretti 2003; Hooper et al 2001). Thus, colonizing organisms have the potential to impact the normal physiological status and development of the epithelium through modulation of host gene expression. Study of the effect of the oral flora on the oral epithelium in the gingival crevice is less advanced; however emerging work suggests a role in stimulating the host innate immune response (Darveau et al 1998; Dixon Bainbridge and Darveau 2004). Since host and microbiota interactions are inherently unstable, disease may arise in the oral cavity of a susceptible host when a perturbation occurs at the subgingival interface between host and bacteria.

The subgingival microbial challenge

The etiology of oral infectious diseases is complex and involves consortia of bacteria working in concert with immunological susceptibilities in the host. Colonization of the subgingival area initially depends on extension of the supragingival plaque biofilm below the gumline, whereupon it becomes subgingival plaque. The subgingival area is less oxygenated, and this in combination with the metabolic activity of the initial colonizers such as the streptococci, reduces the oxygen tension and allows anaerobes to survive. Early colonizing streptococci such as S. gordonii generally do not cause disease in the oral cavity but are capable of causing disease at systemic sites such as on defective heart valves. While the relative proportion of streptococci decreases as subgingival plaque matures, the total number of these organisms remains high (Aas et al 2005; Quirynen et al 2005; Socransky et al 1998; Ximenez-Fyvie Haffajee and Socransky 2000). A predominant anaerobic species in the subgingival biofilm is F. nucleatum, a gram-negative organism that is prevalent in mature plaque in both health and disease (Dzink Socransky and Haffajee 1988; Moore and Moore 1994; Tanner and Bouldin 1989) and thus considered an opportunistic commensal. The presence of S. gordonii and F. nucleatum favors colonization by later, more pathogenic organisms such as P. gingivalis which plays a role in the initiation and progression of chronic periodontitis. Another later pathogenic colonizer is A. actinomycetemcomitans, a causal agent of the clinically distinct localized aggressive periodontitis (LAP). However, while traditionally bacteria have been viewed as beneficial (good) or harmful (evil) it is our contention that these designations are no longer useful. In his pivotal work, “Beyond Good and Evil”, Nietzsche explored the concept of abandoning traditional morality in favor of a perspectival view of the nature of knowledge. Simply stated, “it is we alone who have fabricated causes…motive and purpose”. Similarly, we should progress beyond the traditional concept of bacteria as good or bad, and rather embrace a contextual view of relative potential pathogenicity. Transcriptional profiling specifically allows the host to report the level of disruption induced by bacteria to impact host cells in the absence of preconceived notions regarding bacterial intentions.

The epithelial cells that line the gingival crevice constitute the initial interface between potential periodontopathic organisms, such as P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans, and the host. However, commensal organisms including S. gordonii also have the opportunity to interact with gingival epithelial cells (Socransky et al 1998; Ximenez-Fyvie Haffajee and Socransky 2000). Epithelial cells recovered from the oral cavity show high levels of intracellular P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans and streptococci (Colombo et al 2007; Rudney Chen and Sedgewick 2001; Rudney Chen and Sedgewick 2005). Consequently, it can be hypothesized that the regulation of normal host cell physiological processes by these bacteria may be key to a balanced longstanding co-existence, and thus may also provide putative targets for therapeutic intervention (Habib et al 1999; von Gruenigen et al 1998; Wu 2003).

Both A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis impact host epithelial cell signaling pathways, including those that funnel through nuclear transcription factors. Moreover, many oral organisms including A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum and S. gordonii have been shown to modulate expression of individual genes in epithelial cells (Belton et al 1999; Cao et al 2004; Darveau et al 1998; Fives-Taylor et al 1999; Guthmiller Lally and Korostoff 2001; Haraszthy et al 2000; Holt et al 1999; Korostoff et al 1998; Korostoff et al 2000; Lamont et al 1995; Lamont and Jenkinson 1998; Meyer Sreenivasan and Fives-Taylor 1991; Meyer Lippmann and Fives-Taylor 1996; Meyer Mintz and Fives-Taylor 1997; Meyer and Fives-Taylor 1997; Nakhjiri et al 2001; Noguchi et al 2003; Shenker et al 1999; Shenker et al 2000; Shenker et al 2001; Song et al 2002; Yilmaz Watanabe and Lamont 2002; Yilmaz et al 2003; Zhang et al 2001a; Zhang Pelech and Uitto 2004; Zhang et al 2004). Thus epithelial cells are capable of sensing and responding to oral bacteria at the transcriptional level. However, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that despite the pathogenic potential of individual species, periodontal lesions are mixed infections and the contribution of specific organisms to disease status is difficult to assess. Moreover, mixtures of organisms can be more pathogenic than single species (Ebersole et al 1997; Kesavalu Holt and Ebersole 1998). Conversely, the presence of certain species, such as streptococci, can be antagonistic to others such as A. actinomycetemcomitans (Hillman and Socransky 1982; Hillman Socransky and Shivers 1985). While such synergistic and antagonistic interactions can occur at the bacteria-bacteria level, the impact of mixed microbial challenges on epithelial cell transcriptional responses has received little attention. Studies have shown, however, that P. gingivalis can antagonize the ability of Fusobacterium nucleatum to stimulate IL-8 and ICAM-1 (Darveau et al 1998; Huang et al 2001). Thus the composition and timing of microbial challenge could have significant implications for epithelial cell transcriptional activity.

Epithelial cell responses to bacterial infection dissected with human DNA microarrays

As mentioned above, epithelial cells are one of the first cell types encountered by a pathogen of the mucosal surface. In particular, keratinocytes are the main cell type in gingival epithelial tissues (Asai et al 2001a; Huang et al 2001; Pleguezuelos et al 2005; Suchett-Kaye Morrier and Barsotti 1998). In addition to their barrier function, these cells also actively sense and signal the presence of bacteria and mobilize innate and specific defense mechanisms (Hybiske et al 2004; Ichikawa et al 2000; Lory and Ichikawa 2002; Mans Lamont and Handfield 2006). Thus, it is increasingly appreciated that epithelial tissues such as the gingival epithelia are not merely passive barriers to infection but have a proactive role in immune responses and the development of localized inflammatory conditions such as periodontitis.

The completion of the human genome sequence has ushered in a new era in the study of host-pathogen interactions. It is now possible to monitor the responses of host cells to bacterial challenge on a global scale. Expression profiling based on DNA microarrays (gene chips) permits the identification of pathways that are mobilized by the host in response to an invading organism. Using a combination of expression profiling performed on human DNA microarrays and challenge with microbial mutant strains, it is now possible to characterize the role of individual bacterial virulence factors in the recognition, response and subsequent mobilization of host responses (Cummings and Relman 2000; Kato-Maeda Gao and Small 2001; Kellam 2000; Kellam and Weiss 2006; Manger and Relman 2000). As recently reviewed by Mans et al., (Mans Lamont and Handfield 2006), microarrays can be used to monitor the molecular dialogue between host and bacterial cells and allow the epithelial cells to “describe” their responses to individual bacteria and to specific bacterial molecules. To date, the use of different sets of arrays and experimental systems in different studies has precluded a direct comparison of the genes discovered with similar organisms. Nevertheless, interesting similarities have been observed and the modulation of a large number of induced or repressed genes was found in all systems tested (Cummings and Relman 2000; Kagnoff and Eckmann 2001; Kato-Maeda Gao and Small 2001; Kellam 2000; Kellam and Weiss 2006; Manger and Relman 2000; Yowe Cook and Gutierrez-Ramos 2001). Human microarrays have also been used to determine the transcriptional response of gingival epithelial cells to co-culture with oral microbiota. In particular, transcriptional profiling, bioinformatics, statistical and ontology tools were used to uncover and dissect genes and pathways of human gingival epithelial cells that are modulated upon interaction with important oral organisms that have specific pathogenic personalities. A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis are considered more aggressive pathogens, although these organisms can also be present in the absence of disease. F. nucleatum is considered more of an opportunistic commensal that may participate in the disease process when environmental conditions allow. S. gordonii generally does not directly contribute to the periodontal disease process. In addition, these organisms are representative of distinct temporal stages in the development of the subgingival biofilm: early – S. gordonii; mid – F. nucleatum; and late – P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans.

General considerations for array analysis of host-microbe interactions

Early investigations described above demonstrated the promise and potential of this new technology as a major research tool in the biological sciences. Unfortunately some early studies also served to illustrate potential pitfalls associated with improper experimental methodologies and inadequate or faulty computational analysis. In particular, the use of measurements of hybridization signal intensities to infer gene expression involves many steps, some of which are poorly understood. Key to the design, analysis and interpretation of microarray experiments is the understanding that the parameter being measured, signal intensity of indirectly labeled probes, is many steps removed from the parameter being inferred, gene expression. A typical microarray experiment represents a large-scale physiological study in which cells are isolated, RNA is harvested, labeled representations of the harvested RNA are prepared, and then used in hybridization experiments to indirectly label the nucleic acid probes constituting the array. The signal intensity of the label at each probe on the array is taken as a measure of gene expression for the genes specified by the probes on the array. It is also important to realize that the inferred gene expression is not that of a single cell but rather that of a population of cells. In some cases the population of cells under investigation is composed of many different cell types each of which may have varied expression profiles unique to themselves.

Microarray experiments are sensitive, albeit indirect, assays capable of measuring the genomic response to subtle changes in the environment that occur during the RNA harvesting process. Uncontrolled experimental variables may be introduced at any step in the wet laboratory work up of microarray experiments and may add to observed variances from array to array. In designing microarray experiments, it is important to recognize areas where uncontrolled experimental variables may be introduced so that they may be guarded against; although in some cases they are unavoidable. In these instances variations in the experimental protocol should be documented (Brazma et al 2001). Potential sources of uncontrolled experimental variables vary with individual applications. In clinical studies involving patient volunteers, the greatest potential for uncontrolled experimental variables exists. For instance in clinical studies uncontrolled experimental variables may include: age of subject, diet, diurnal variations in gene expression, type of anesthesia used, length of ischiemia prior to tissue removal, time from tissue removal to RNA stabilization, and method of RNA isolation. In contrast, in considering experiments with tissue or cell cultures, passage number also needs to be added to the list of potential sources of variation mentioned above.

In addition to apparent gene expression differences associated with uncontrolled experimental variables, biases and artifacts may be introduced by virtue of the methods used at each step of the procedure, including cellular and tissue harvest, RNA isolation, and labeling methods. Differential recovery of specific cell types from tissue may bias the gene expression profile observed for a particular tissue type. Likewise, RNA isolation protocols may introduce bias if they differentially recover membrane bound RNA versus soluble RNA. In one large study involving gene expression profiling of human leukocytes before and after Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B (SEB) treatment, the largest response variable was method of RNA isolation and not SEB stimulation; although with both RNA isolation protocols, gene expression differences due to SEB stimulation were readily apparent (Feezor et al 2004). Labeling reactions involving limited amplifications of the target material such as those used with Affymetrix GeneChips can result in skewing if unequal amplification occurs during the in vitro transcription reactions. The last step in the indirect labeling of the array is the hybridization of the targets to the probes. The hybridization reaction is governed in large part by the specific sequences of the individual targets and probes and is affected by the ability of the target to form secondary structures with itself and other molecules that may be present in the hybridization mixture. Target molecules that form extensive secondary structure with themselves tend to produce dimmer signals than targets that are devoid of secondary structure (Mir and Southern 1999; Southern Mir and Shchepinov 1999). Some hybridization protocols employ a target fragmentation step in an attempt to circumvent secondary structure problems. Other factors that may affect hybridization from experiment to experiment, and hence hybridization signal intensity, are temperature and duration of hybridization; both of which are important experimental parameters that should be highly controlled.

Microarray experiments by their nature are very complex experiments that indirectly provide a measure of gene expression. The steps between gene expression at the level of mRNA expression and measurement of the signal intensities of the probes arrayed are numerous and some are poorly understood. Yet with care it is possible to use microarrays as a tool begin to discern the dynamic changes that occur within cells as they respond to their environment, but great precautions must be taken to avoid contaminating the dataset with noise resulting from uncontrolled experimental variables.

Microarray experiments are no different than any other experiment; for meaningful results, experiments must be replicated. The question that thus arises is not whether to replicate but the number of replicates to perform and the level at which to replicate. Differences in gene expression due to uncontrolled experimental differences tend to dampen while differences due to the controlled response variable tend to reinforce with replication. The number of replicates to perform is dependant, in part, on the noise associated with the system under study. For the simplest of experiments, such as those aimed at identifying differences between two cell lines, a minimum of three replicates per condition should be budgeted. Four replicates per condition are better and more appropriate if one is considering cross-validation methods such as leave-one-out cross validation or other statistical validation measures.

The level of replication is dictated in part by the question being addressed. If the aim is to determine the variances in hybridization signal intensities associated with length of hybridization time, then technical replicates would be appropriate. Hybridization time would be the sole variable, and the experiment would be designed whereby one preparation of labeled target was repeatedly hybridized to different arrays for varying amounts of time. If however gene expression differences are the goal, then the level of replication should be at the biological level and the replicates should be independent. With clinical specimens more replicates are usually required than for laboratory studies utilizing cell lines or isogenic strains due to the higher coefficients of variation in hybridization signal intensities usually encountered with clinical material.

The development of analytical methods for use on datasets derived from microarray expression studies is a rapidly changing and progressing field (Golub et al 1999; Leek et al 2006; Li and Wong 2001; Storey et al 2005; Storey Dai and Leek 2007; Tusher Tibshirani and Chu 2001; Wright and Simon 2003; Zhang 2006). Most investigators utilize a combination of supervised and unsupervised methods in their analysis and the individual methods of analysis used are somewhat of an art form that vary from investigator to investigator. However there are becoming several generally recognized acceptable methods of analysis.

Most microarray analyses use a combination of supervised and unsupervised statistical methods. Unsupervised statistics attempt to define a model in order to fit observations, and is distinguished from supervised learning by the fact that there is no a priori output. In other words, in unsupervised statistics, input objects are treated as random variables. Thus, the first level of microarray data analysis is usually supervised. One simply seeks to determine which genes are most affected by a particular condition or treatment protocol. In this line of endeavor the investigator makes use of the class labels of the samples, for example wild-type vs. mutant, in determining the probes that display differential signal intensities. Early studies tended to rely on fold-change differences and not on the use of statistics. In several studies published early in the microarray era it was not even clear that replicates were preformed. Among reports that utilize p-values or estimates of error based on permutations of the dataset in setting significance levels, the cutoff levels used remains largely arbitrary. In some cases p-values as low as p = 0.05 for arrays with greater than 54,000 probes have been used. With such a modest threshold, 2700 probes would be expected to exceed the threshold by chance alone. Clearly for larger arrays, a Bonferroni-correction applied to the traditional p-value of 0.05 may be too stringent. A significance threshold of p < 0.001 has been offered as a compromise between the traditional p < 0.05 and a Bonferroni corrected p < 0.05. Many investigators prefer to tune the significance level used for specific studies by estimating false discovery rates based on permutations of the dataset (Tusher Tibshirani and Chu 2001).

In many cases supervised analyses are used for purposes of identifying genes that can be used for class prediction, for example to diagnose and differentiate diseased from normal tissue. In this case the goal of the investigator is to identify probes that are predictors of the class labels, which then can be used in future studies to identify the nature of the specimen as normal or diseased using one or more of several prediction models. Investigators however should be aware that microarray experiments exemplify the “small n large p” trap. The number of probes on a typical microarray, tens of thousands, vastly exceeds the number of categories into which the arrays can be classified. Thus, by chance alone it is likely that many probes can be identified out of a typical dataset that can distinguish between the small numbers of class labels in a typical study. Cross validation studies and Monte Carlo simulations should be employed to gauge the significance of the probes identified as predictors.

Supervised analyses are only as good as the supervision applied. In cases where the class labels of the specimens are definitively known, as in comparing gene expression of a wild-type tissue vs. tissue of a knock-out organism where the genotypes of the wild-type and knock-out are precisely known, supervised analyses can be very powerful. However when phenotypic distinctions are subtle and class labels are known with less certainty, as is the case often encountered in the clinical setting where highly skilled pathologists may disagree over the diagnosis of a tumor as a particular cancer or grade, supervised analysis methods are hampered by misclassification errors at the supervision stage.

Unsupervised analysis methods, including hierarchical clustering, k-means clustering, and self organizing maps, can be used as tools for class discovery in situations where standard methods of assigning class labels are incomplete or inadequate. In situations where class labels can be assigned with impunity, as in studies designed to identify gene expression differences between a wild-type and knockout animals, unsupervised cluster analysis can be used as an assessment of overall reproducibility of measurements between replicates. Experimental replicates should cluster together according to the controlled response variable in this case, wild-type with wild-type and knockout with knockout. If replicates do not cluster together or if clustering occurs according to some other identifiable variable, such as date of tissue harvest or date of labeled target preparation, then responses to uncontrolled experimental variables are likely contaminating the dataset, obscuring gene expression changes resulting from the controlled experimental variable.

For the experiments reviewed in this paper we used array-to-array comparisons that were carried out using unsupervised and supervised methods. This was performed to assess the relatedness of the specimens under investigation using methods exhaustively described elsewhere (Handfield et al 2005). Hierarchical clustering was first used to perform an unsupervised analysis. The resulting dendrogram revealed that the array chips from each infection state clustered together (Fig. 1) indicating that each infection state elicited a specific and distinct transcriptome in HIGK cells. This was also an indication of the quality and consistency of the hybridization procedure.

Figure 1. Different patterns of gene expression of oral epithelial HIGK cells upon co-culture with oral species.

Hierarchical clustering of variance-normalized gene expression data from uninfected human HIGK cells and from cells in co-culture with microorganisms for 2 h before RNA isolation and purification. Expression and variation filters were applied to the data set before clustering. Probe sets giving hybridization signal intensity at or below background levels on all arrays tested were eliminated from further analysis. The resulting data set was culled by ranking on the coefficient of variation and eliminating the bottom half of the data set to remove probe sets whose expression did not vary between the treatment regimens. The gene expression observations were variance normalized to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, and this normalized data set was subjected to hierarchical cluster analysis with average linkage clustering of the nodes. The variation in gene expression for a given gene is expressed as distance from the mean observation for that gene. Each expression data point represents the ratio of the fluorescence intensity of the cRNA from A. actinomycetemcomitans infected (columns Aa), P. gingivalis-infected (columns Pg) F. nucleatum-infected (column Fn) and S. gordonii-infected (column Sg) to the fluorescence intensity of the cRNA from mock-infected HIGK cells (columns CTRL). The scale adjacent to the dendrogram relates to Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Re-normalized from array data previously reported in Handfield et al. (2005) and Hasegawa et al. (2007), following procedure described in supplementary information.

Bacteria with distinct pathogenic personalities trigger a distinct transcriptional signature in oral epithelial cells

To characterize epithelial cell responses to species of differing pathogenic potential and to assess the extent to which host responses are characterized by the challenging organism, we used transcriptional profiling to monitor relative abundance of human immortalized gingival keratinocytes (HIGK) transcripts following co-culture for 2h with A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum or S. gordonii. This was done by re-normalization of a collection of previously reported array experiments (methods presented in supplementary material; from data presented in Handfield (Handfield et al 2005) and Hasegawa (Hasegawa et al 2007a). As shown in Figure 1, supervised analyses were next performed to identify gene expression differences between uninfected HIGK cells as compared to infected cells with the four bacterial species. Overall, the common core transcriptional response of epithelial cells to all organisms was very limited, and organism-specific responses predominated. No obvious correlation was found between the pathogenic potential or invasive potential of individual bacterial species and the core response of challenged host cells. To test the predictive validity of the probe sets identified, a ‘leave-one-out’ cross-validation was performed with four different prediction models (linear discriminant, 1KNN, 3KNN and nearest centroid; see Supplementary Table 1). This validation step addressed the reproducibility of the datasets and the performance of the classifiers for each bacterial species.

Insight into gingival cell-microbiota interactions from ontology analysis of the most impacted pathways

It is a daunting challenge to analyze the massive amount of data that is generated by any microarray experiment, and to synthesize information that has biological relevance. One avenue is to apply gene ontology tools to analyze the complex array output and cull down to biologically significant information. Gene ontology is defined as a hierarchical structuring of the constantly evolving sum of knowledge that is compiled for all known genes and the pathways that they relate to. The structure is performed by subcategorizing genes according to their essential (or at least relevant) biological function. Thus, gene ontology can be applied to all organisms even as knowledge of gene and protein roles in cells is accumulating and changing. Gene ontology uses statistical algorithms to structure and mine complex array data, which is then used to determine how biologically relevant information can be extracted from microarray data. Essentially, an ontology analysis compares the total number of genes of a given ontology family that are found consistently modulated in a given array experiment, to the total number of genes comprising the same pathway. This comparison can be quantified and used to determine the probability that this particular pathway is significantly impacted, as compared to what would be expected if the number of genes found in an experiment were to be randomly distributed amongst all known pathways. Although it should be remembered that cells in vivo are subject to inputs from multiple signaling pathways and these signaling pathways do not work in isolation of each other (Jordan Landau and Iyengar 2000; Mehra and Wrana 2002a). Signaling cascades may intersect or their activities may depend on the output of other simultaneous signals. As shown in Table 1, ontology analysis overlaid on the transcriptional profiles of HIGK cells upon infection with oral bacteria revealed that the most impacted pathways were common amongst all bacterial infections. Yet, for most impacted pathways, each bacterium induced a characteristic pattern of expression in the host epithelial cells. In other words, the common core transcriptional response relates to the identity of the genes that, although different, were found to still impact similar pathways. Hence, although the transcriptional signature is different and characteristic of species, the host’s response is apparently limited to a few discrete pathways. Note that while two distinct organisms can impact the same pathway, they do not necessarily impact the same pathway in a consistent, physiologically-relevant and similar response.

Table 1.

Ontology Analysis of the Top Ten Gingival Epithelial Cell Pathways Impacted by Infection with Oral Bacterial Speciesa.

| Impacted pathwayb | Impact factorc | Input genes/Pathway genesd | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focal adhesion | 5.3 | 17.0 | 0.005 |

| MAPK signaling pathway | 4.4 | 15.0 | 0.012 |

| Wnt signaling pathway | 4.0 | 15.6 | 0.018 |

| Cell cycle | 3.3 | 16.1 | 0.038 |

| ECM-receptor interaction | 3.3 | 17.2 | 0.039 |

| Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | 2.7 | 13.6 | 0.067 |

| Apoptosis | 2.7 | 16.7 | 0.067 |

| TOLL-like receptors | 1.9 | 14.3 | 0.445 |

| TGFβ signaling | 1.9 | 14.3 | 0.450 |

| JAK-STAT signaling | 1.1 | 11.1 | 0.717 |

Pathogenic, commensal or opportunistic species including A. actinomycetemcomitans, F. nucleatum, P. gingivalis and S. gordonii.

Determined by Pathway Express (Khatri et al., 2005), mapped to Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) and ranked according to the Impact Factor using a threshold of ≥10 input genes per impacted pathway and ≥15% of represented genes in a given pathway.

The impact factor measures the pathways most affected (relatively) by changes in gene expression, by considering and integrating the proportion of differentially regulated genes, the perturbation factors of all pathway genes, as well as the consistency of the propagation of these perturbations throughout the pathway.

Ratio of the number of regulated genes in a pathway/total number of genes currently mapped to this pathway.

The following paragraphs further dissect these differentially impacted pathways in an attempt to provide additional insight into the intricate mechanisms that different microbes have evolved to manipulate epithelial cells in the oral cavity. Because of space constraints, other pathways of particular interest that are listed in Table 1 could only be depicted in the supplementary electronic version of this manuscript. These pathways include the cell cycle, the TOLL-like receptors, JAK-STAT signaling and cytokine profiles, TGF-β signaling, Wnt signaling and apoptosis.

Focal Adhesion, Extra-Cellular Matrix (ECM)-Receptor Interaction and Regulation of the Actin Cytoskeleton

The most common target of invasive bacteria in eukaryotic epithelial cells is arguably the cytoskeleton (Stebbins 2004). The interactions between invasive bacteria and the cytoskeleton are numerous and of considerable complexity, reflecting the complexity of the cytoskeleton itself (Steele-Mortimer Knodler and Finlay 2000). Since cytoskeletal dynamics are central to immune function, cell shape and motility, organelle and chromosome movement, phagocytosis, processes that can also be important to invading bacteria, evolution has favored species that have acquired the ability to modulate this important aspect of host cell biology (Stebbins 2004; Steele-Mortimer Knodler and Finlay 2000). Cytoskeletal modulation can occur at several points of contact between bacteria and the host cells, and involves extracellular receptors, intracellular signal transduction and cytoskeletal proteins themselves (Stebbins 2004). A number of examples, mostly taken from enteric pathogens, illustrate that various host cytoskeletal components are common targets of bacterial virulence determinants. These host cytoskeleton proteins include actin, tubulin, vimentin, profilin, filamin, fimbrin/plastin and others (Gruenheid and Finlay 2003; Pizarro-Cerda Sousa and Cossart 2004; Stebbins 2004; Steele-Mortimer Knodler and Finlay 2000). The eukaryotic proteins of the Rho family, such as Rho itself, Rac and Cdc42, are key GTPases that exert signaling events ultimately leading to cytoskeletal organization of the cell (Stebbins 2004; Steele-Mortimer Knodler and Finlay 2000). Such cytoskeletal changes are required for the formation of lamellipodia (membrane ruffles), filopodia (microspikes), stress fibers, and focal adhesions (Steele-Mortimer Knodler and Finlay 2000). Rho proteins also interface in the signaling cascades that regulate a number of other cellular processes including endocytosis, secretion, cell-cycle regulation, and apoptosis (Steele-Mortimer Knodler and Finlay 2000).

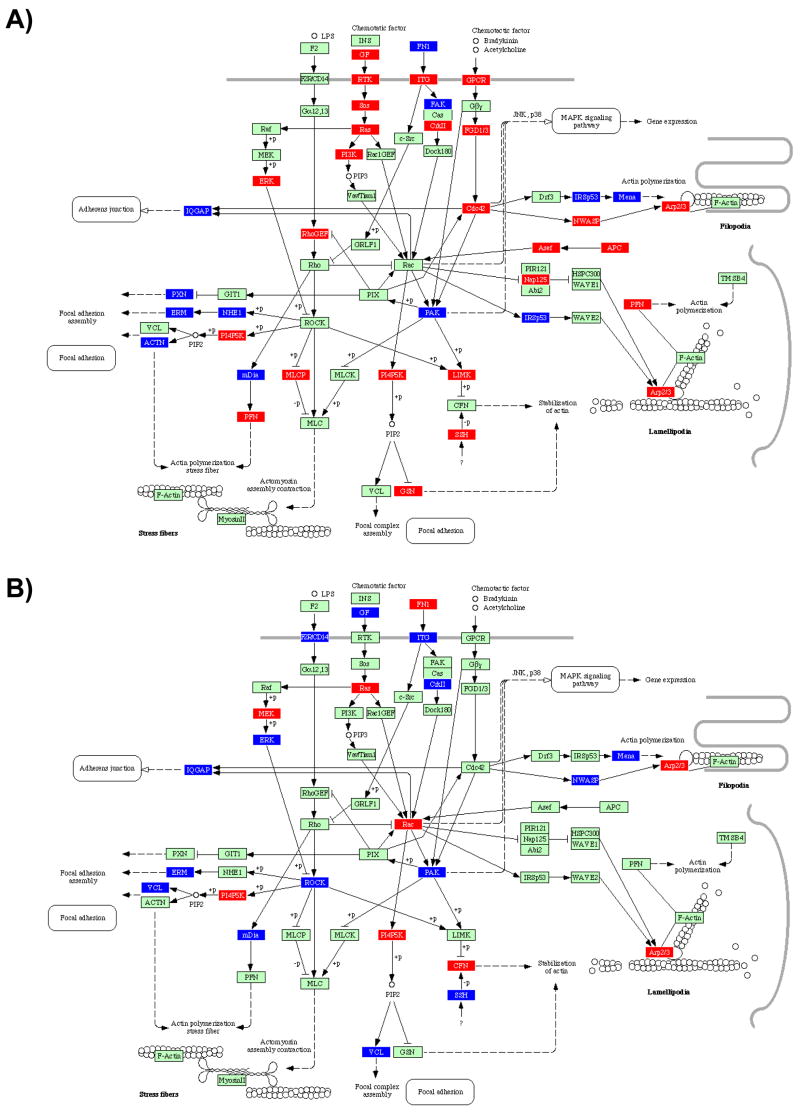

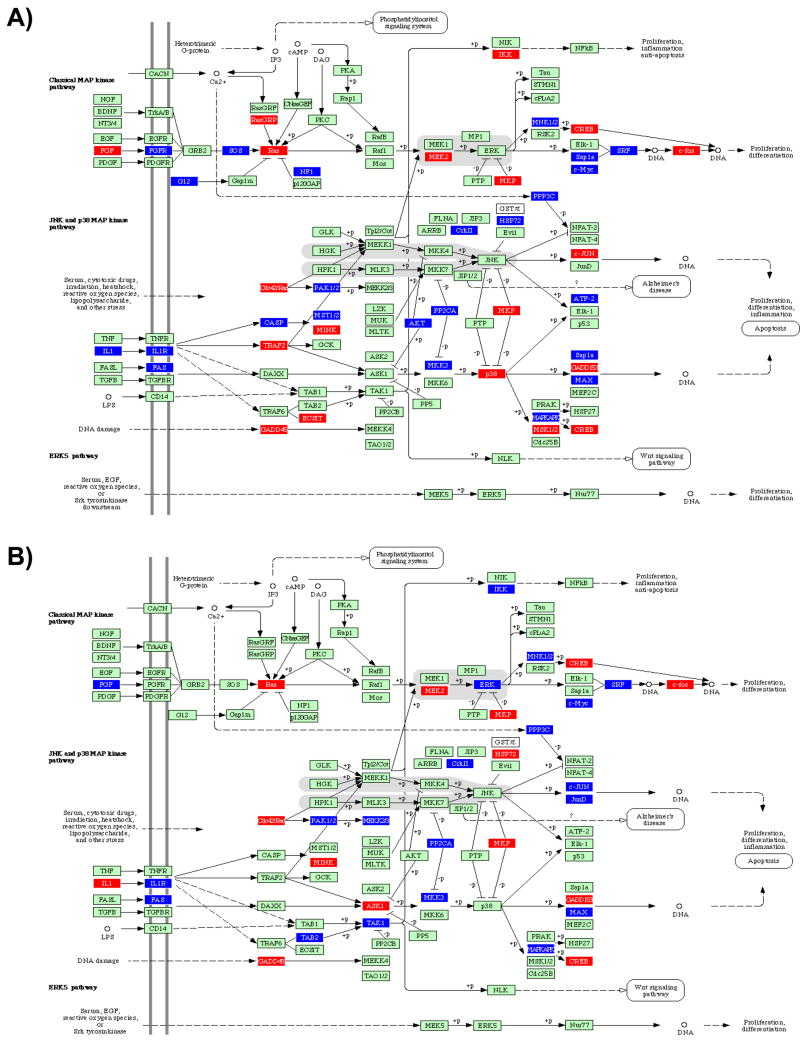

While information regarding cytoskeletal responses to invasive enteric pathogens is well established, less is known about the impact of oral bacteria on cytoskeletal structure. As shown in Figure 2.1, infection of HIGK cells with all microbes tested reveals a number of significant differences in cytoskeletal pathway responses. For example, Rac was upregulated in both S. gordonii and F. nucleatum-infected cells. The activation of Rac may stimulate the host cell to maintain homeostasis, returning cell morphology to a normal state post-infection, or disrupt the cytoskeleton as a means to modulate bacterial cell uptake (Gruenheid and Finlay 2003). In contrast, Cdc42 was upregulated by infection with both A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis, but down- or not regulated by F. nucleatum and S. gordonii, respectively, despite the invasive properties of F. nucleatum (Edwards Grossman and Rudney 2006; Ellen 1999b; Han et al 2000; Uitto et al 2005; Weiss et al 2000). Cdc42 has been involved with the burst of actin polymerization which occurs during Shigella invasion (Mounier et al 1999). The membrane–cytoskeletal linker protein ezrin, also a member of the ezrin/radixin/moesin (ERM) family, plays an active role in Shigella invasion of epithelial cells. Ezrin is enriched in the cellular protrusions surrounding and induced by the bacterium and colocalizes with F-actin. (Skoudy et al 1999). Although Rho itself was not transcriptionally modulated by infection with any bacterium, ERM was upregulated by infection with P. gingivalis (only). This was consistently accompanied in P. gingivalis-infected cells by the up-regulation of the upstream protein kinase ROCK, which is known to be triggered in response to enteric LPS stimulation via transduction by F2R/CD14.

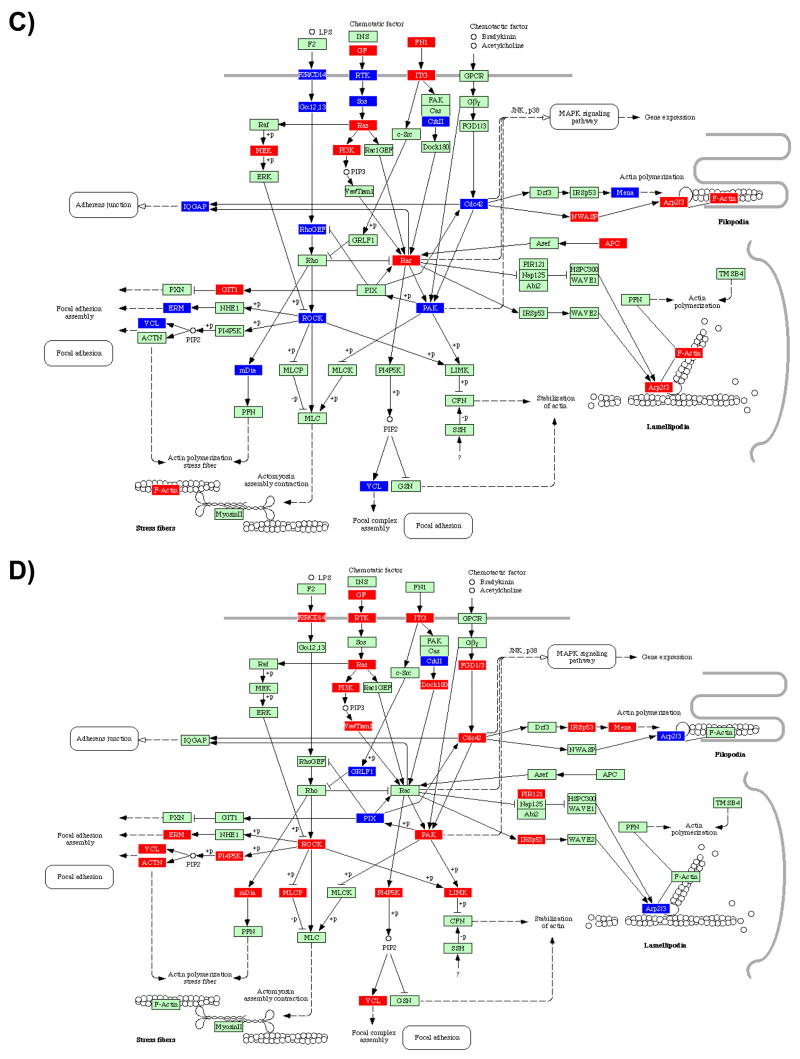

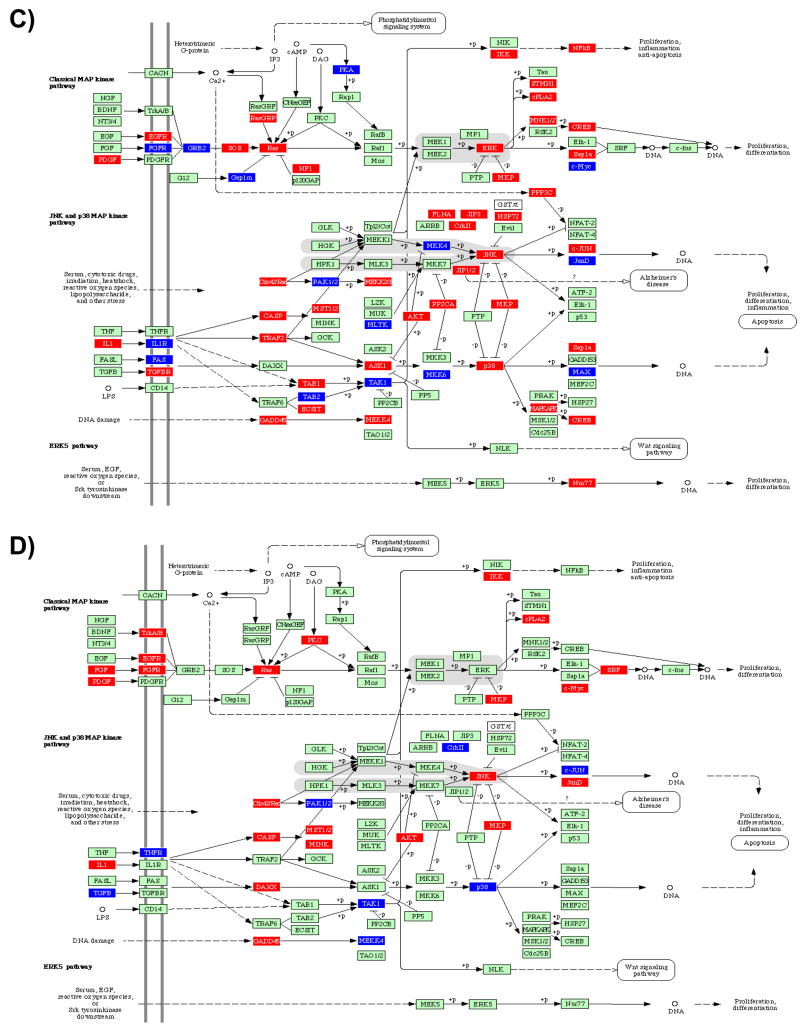

Figure 2. Ontology analysis of selected pathways of infected HIGK Cells.

2.1 Regulation of the Actin Cytoskeleton; 2.2 MAPK Signaling Pathway. BRB Array Tools was used to generate probesets differentially regulated at the P<0.05 level of significance. The geometric mean signal intensity level for probesets passing this threshold were analyzed with Pathway Express software to populate known KEGG pathways according to transcriptional profiles obtained from GeneChip experiments. HIGK response of infected vs controls for A) S. gordonii, B) F. nucleatum, C) A. actinomycetemcomitans and D) P. gingivalis. Genes shown in red are transcriptionally induced compared to the baseline level, while genes in blue are transcriptionally down-regulated. Genes in green are unchanged at the P<0.05 significance level.

Many intracellular pathogens have independently evolved mechanisms to harness the activity of the actin cytoskeleton at different points, in some cases resulting in the formation of an actin tail that propels intracellular organisms between host cells. Strikingly, these strategies all converge on the Arp2/3 complex. This is a seven-protein complex that, when activated, nucleates de novo actin polymerization on the surface of the bacterium (Hueck 1998; Welch Iwamatsu and Mitchison 1997; Welch et al 1998; Zhou and Galan 2001). Arp2/3 is activated by the Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) family. These proteins, which serve a scaffolding function to bring together actin monomers and Arp2/3 to form a nucleation core, dictate the rate-limiting step in actin polymerization (Gruenheid and Finlay 2003). It is interesting to note that Arp2/3 was induced by all bacterial species except P. gingivalis, although S. gordonii is not invasive and A. actinomycetemcomitans is not thought to use actin for intracellular cell mobility (Meyer et al 1999).

Surface receptors provide a means for bacteria to induce intracellular signals that affect the cytoskeleton (Cossart and Lecuit 1998; Kahn Fu and Roy 2002; Stebbins 2004). It has been established that P. gingivalis fimbriae bind and activate the β1-integrin receptor and consequently induce signal transduction through downstream targets of the integrin receptor such as Pyk2, Src, Rac, Arp2/3, FAK and CAS, leading to actin and tubulin rearrangements and bacterial uptake (Yilmaz Watanabe and Lamont 2002). As presented in Supplementary Fig. 2.1, integrins (ITG) were transcriptionally regulated following a pattern that was species-specific. In particular, P. gingivalis up-regulated all integrins detected, in sharp contrast to F. nucleatum which down-regulated all integrins detected. In the middle of this spectrum, S. gordonii down-regulated all integrins except α10, whereas A. actinomycetemcomitans up-regulated α3, α4, α5, β3 and β4 integrins, but down-regulated α2, α6, β5, and β6 integrins. Taken together, the higher pathogenic potential of A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis correlated with the upregulation of α3, α4, α5, β3 and β4 integrins, whereas the more commensal nature of S. gordonii and F. nucleatum was associated with the down regulation of all integrins, except α10 (upregulated by S. gordonii only). Various ECM components were also differentially expressed following a species-specific pattern. For example, collagen, laminin, THBS (thrombospondin, an adhesive glycoprotein that mediates cell-to-cell and cell-to-matrix interactions) and tenascin were all up-regulated by P. gingivalis. A. actinomycetemcomitans up-regulated all of these ECM proteins except fibronectin. In comparison, F. nucleatum up-regulated fibronectin only, while S. gordonii up-regulated laminin and fibronectin. Hence, more overtly pathogenic species appear to specifically up-regulate collagen and thrombospondin.

In addition, A. actinomycetemcomitans infection was characterized by the up-regulation of glycoproteins CD44, SV2, αDG and βDG (aka DAG, dystroglycan 1 and 2, or dystrophin-associated glycoproteins). Of particular interest, CD44 is a hyaluronic acid (HA) binding protein that mediates cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions. CD44 has been shown to facilitate the migration of E. coli through the epithelial monolayer and thus increases the migration of the bacterium through the urinary-tract epithelium (Rouschop et al 2006). In Group A Streptococcus (GAS) infections, ligation of CD44 by its hyaluronic acid capsule induces epithelial cell movement on extracellular matrix and marked cytoskeletal rearrangements manifested by membrane ruffling and disruption of intercellular junctions. Transduction of the signal induced by GAS binding to CD44 on keratinocytes opened intercellular junctions and promoted tissue penetration by GAS through a paracellular route (Cywes and Wessels 2001). In the case of Shigella, entry into epithelial cells is characterized by a transient reorganization of the host cell cytoskeleton at the site of bacterial interaction with the cell membrane, which leads to bacterial engulfment in a macropinocytic process. CD44 associates with IpaB, a Shigella protein that is secreted upon cell contact. The IpaB-CD44 interaction appears to be required for Shigella invasion by initiating the early steps of the entry process (Skoudy et al 2000). Collectively, these results support a potentially novel host cytoskeleton manipulation system of tissue invasion by A. actinomycetemcomitans.

In P. gingivalis-infected epithelial cells, actin remodeling has been shown to be required for P. gingivalis entry into gingival epithelial cells (Abreu et al 2001; Lamont et al 1995) and is known to be mediated by the engagement of integrins (Yilmaz Watanabe and Lamont 2002). Prolonged invasion with intracellular P. gingivalis results in a cortical redistribution and condensation of actin microfilaments (Hasegawa et al 2007a). The impact of P. gingivalis on actin cytoskeletal architecture remodeling was associated here with the differential regulation of a number of actin binding proteins, including ACTN, WAVE2, Mena, mDia and LIMK (Fig. 1.1). ACTN (α-actinin) is an F-actin cross-linking protein that can anchor actin to a variety of intracellular structures. WAVE2 is involved in transmission of signals from tyrosine kinase receptors and small GTPases to the actin cytoskeleton. Mena (ENAH)/VASP is an actin-associated protein involved in a range of processes relating to cytoskeleton remodelling. mDia can directly nucleate, elongate, and bundle actin filaments, and can also activate PFN which is involved in the assembly or maintenance of cortical microfilaments. LIMK is a protein kinase that phosphorylates and inactivates the actin binding/depolymerizing factor cofilin, thereby stabilizing the actin cytoskeleton and preventing actin remodeling (Hasegawa et al., unpublished). Further, only P. gingivalis triggered the up-regulation of Caveolin, which serves to stabilize and organize lipid raft components and is necessary for bacterial invasion of numerous pathogens (Abraham et al 2005). This mechanism has previously been shown to be required for effective invasion of P. gingivalis into human oral epithelial cells (Tamai Asai and Ogawa 2005).

The focal adhesion pathway is closely interlaced with regulation of the actin cytoskeleton pathway. These pathways share a number of effector proteins that feed into one another. In particular, the integrins discussed above are critical molecules that mediate epithelial barrier formation, as well as cell activation, proliferation, differentiation, metabolism, and motility (Gumbiner 1996; Nakagawa et al 2006). Integrins provide a physical link, via focal adhesion, between the extracellular environment and the intracellular cytoskeleton (Clark et al 1998). Focal adhesions are involved in cellular anchorage and directed migration, as well as in signal transduction pathways, which ultimately control wound healing and regeneration, as along with tissue integrity (Hakkinen Uitto and Larjava 2000). Key factors in these events include paxillin and the focal adhesion kinase FAK. The phosphorylation of FAK is a central regulator of cell migration during integrin-mediated control of cell behavior (Schlaepfer Hauck and Sieg 1999). Paxillin is localized primarily at sites of adhesion of cells to the extracellular matrix (i.e., focal adhesions), and activation of this molecule is a prominent event upon integrin activation for actin-cytoskeleton formation, as well as the recruitment of FAK to robust focal adhesions (Nakagawa et al 2006; Nakamura et al 2000; Ren Kiosses and Schwartz 1999).

As presented in Supplementary Fig. 2.2, focal adhesion components were differentially regulated among the bacteria tested. Although some extra-cellular matrix proteins (ECM, i.e. laminins) were up-regulated by all bacterial species, only A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis also up-regulated their corresponding receptors, the alpha- and beta-integrins (ITGA and ITGB, respectively). Furthermore, epidermal growth factor (GF) and it’s receptor (RTK) were up-regulated by A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis, while F. nucleatum induced GF but not it’s receptor. FAK and paxillin were not transcriptionally modulated by S. gordonii, F. nucleatum or P. gingivalis, and both components were down-regulated by A. actinomycetemcomitans. It has also been demonstrated that GECs infected with P. gingivalis demonstrate a significant redistribution of paxillin and FAK from the cytosol to cell peripheries and assembly into focal adhesion complexes, which is dependent on the expression of FimA. Ultimately, the majority of paxillin and FAK return to the cytoplasm with significant co-localization with P. gingivalis in the perinuclear region (Yilmaz Watanabe and Lamont 2002; Yilmaz et al 2003). Interestingly, enhanced FAK immunostaining is detected in small populations of preinvasive (carcinoma in situ) oral cancers and in large populations of cells in invasive oral cancers. FAK is probably not a classical oncogene but has been suggested to be involved in the progression of cancer to invasion and metastasis (Kornberg 1998; Kornberg et al 2005) which may offer some physiological basis that provides a mechanistic basis for a possible link between infection with oral pathogens and oral cancers

Seemingly, some pathogens bind and modify junction components directly, while others exert their effects through the actin cytoskeleton, which ultimately controls the integrity of tight junctions (Gruenheid and Finlay 2003). P. gingivalis remarkably displays a dual action, highlighting again the relevance of the manipulation of the host cytoskeleton in oral host-microbe interactions. In this regard, P. gingivalis binds to and/or degrades gingival proteoglicans and matrix proteins, including laminin and fibronectin (Ellen 1999a), as well as directly affecting the cytoskeleton through secreted products, such as SerB. Although much work is being currently done to identify the host and other bacterial players involved in these phenomena, the exact sequence of events and their interrelation remains to be established.

Considering the co-evolution of oral commensals and the epithelial surface of the oral cavity, and the profound effect that S. gordonii has on the transcriptome of epithelial cells, it may be more appropriate to assume that the normal physiologic steady-state of epithelial cells is in continuous response to commensal bacterial species. Altogether, one could argue that an infected state is normal, and possibly beneficial for the oral epithelium as it confers a state of wound healing, driven by infection or coexistence (Ellen 1999a). Oral pathogenicity then would be associated with the expression of virulence determinants that impinge on the cytoskeleton, possibly reflective of failure to reach evolutionary balance. Disregulation of cytoskeletal proteins may have profound effect on the normal physiologic homeostasis of the periodontium, affect the normal physiologic remodeling of the tissue and exacerbate inflammatory pathways.

Cell Cycle

Eukaryote cells coordinate their cell division through four phases: cell growth and preparation for replication (G1- or gap1 phase), chromosome duplication (S- or synthesis phase), growth and preparation for mitosis (G2- or gap2 phase) and mitosis (M-phase). This cell cycle is orchestrated by a set of protein kinases that initiate the successive stages of each cycle and that are associated with regulatory protein subunits called cyclins. To regulate cell cycling, levels of cyclin-dependant kinases (Cdks) are modulated. The kinase activity of Cdks is regulated by association, attachment, binding of inhibitors, phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, and degradation of the associated cyclin. These cyclins ultimately phosphorylate downstream substrates and mediate various cellular processes during cycling. (Elledge 1996; Kaufmann and Paules 1996; Rotman and Shiloh 1999; Smith and Bayles 2006b).

As presented in Supplementary Figure 1.3, infection with all organisms tested had profound and diametrically opposed effects on cell cycling of gingival cells. For example, the cell division cycle proteins CDC20 and CDC25B mediate the mitotic progression and are highly expressed in proliferating cells, their levels peaking in M phase. Both CDC20 and CDC25B were down-regulated by A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis, but upregulated by F. nucleatum and S. gordonii. Consistent with this effect, Bub1 and Bub3, involved in cell cycle checkpoint enforcement, were also downregulated by A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis and upregulated by F. nucleatum and S. gordonii. Only two genes were consistently modulated upon infection: GADD45 was upregulated whereas Cyclin E (CycE) was downregulated by all four microorganisms. The growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible GADD45, as the name indicates, was originally identified as a gene that is induced by agents that cause DNA damage (Fornace Alamo and Hollander 1988; Hasegawa et al 2007b; Papathanasiou et al 1991). Transcriptional regulation of the GADD45 gene is mediated by both p53-dependent and -independent mechanisms (Hasegawa et al 2007b; Takekawa and Saito 1998), and GADD45 family members (α, β and γ) are involved in the activation of p38 and JNK pathways through MEKK4, ultimately affecting various pathways including the cell cycle and the immune response. Up-regulation of GADD45 has been shown to ultimately converge on growth arrest and on the activation of the nuclear transcription factor NF-κB (Hasegawa et al 2007b; Papathanasiou et al 1991; Takekawa and Saito 1998; Takekawa et al 2002; Yang et al 2001). We have previously shown that genes for GADD45α and GADD45β were transcriptionally up-regulated following F. nucleatum infection whereas S. gordonii also up-regulated GADD45β but had no detectable effect on GADD45α. This profile was consistently reflected at the protein level (Hasegawa et al 2007b). Cyclin E (a.k.a CycE, CCNE1 and CCNE2) is known to complex with CDK2 and regulating G1 to S transition of the cell cycle. CCNE1 is overexpressed in many tumors leading to deregulated levels of protein and kinase activity. In addition, CCNE2 is activated by papilloma viral oncoproteins E6 and E7 which bind to and inactivate p53 and Rb, respectively, inducing chromosome instability (according to GeneCards, http://www.genecards.org/index.shtml). Within the confines of our experimental model, it cannot be ruled out that the regulation of CycE by all infecting agents may be an artifact associated with the HPV-immortalized nature of HIGK cells.

In sharp contrast, Cyclin A and Cyclin D were upregulated by S. gordonii, non-regulated by F. nucleatum and down-regulated by both P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans. Cyclin A1 (a.k.a CCNA1) complexes CDK2, and is overexpressed in early G1 phase to reach highest levels during the S and G2/M phases, whereas Cyclin A2 (CCNA2) accumulates steadily during G2 and is abruptly destroyed at mitosis (GeneCards). In addition, both A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis down-regulated Cyclin B which is essential for the control of the cell cycle at the G2/M transition (GeneCards), and down-regulated CDK1 (a.k.a. CDC2 and p34 protein kinase), which plays a key role in the control of the eukaryotic cell cycle during entry into S-phase and mitosis. CDK1 is activated by CDC25 and continually shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm. CDK1 is maintained in an inactive state through phosphorylation by WEE1 (also upregulated in A. actinomycetemcomitans-infected cells) and MYT1. CDK1 is thought to be up-regulated by c-Myc, another gene that is down regulated by all organisms, except P. gingivalis. In A. actinomycetemcomitans- and F. nucleatum-infected cells, Kip1 and Kip2 (a.k.a. cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor CDKN1B or p27, and CDKN1C or p57) were upregulated, providing an additional level of repression for Cyclin A, -D and -E. Kip1,2 are involved in TGF β-induced G1 arrest, and in the cellular response after DNA damage. In the case of A. actinomycetemcomitans-infected cells, this was also consistent with the induction of ATM and DNA-PK (a.k.a. PRKDC), which have been shown to be central to the genotoxic effect the cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) of A. actinomycetemcomitans (Alaoui et al., unpublished). Several checkpoints can stop the cell cycle in response to incomplete replication or damaged DNA, by delaying the progression of the cycle until the DNA damage is repaired, which ensures that the essential events of a cell cycle stage are completed before progression to the next stage. Phenotypically, the checkpoints extend the length of a stage for DNA repair to take place prior to DNA replication and mitosis (Elledge 1996; Kaufmann and Paules 1996).

A. actinomycetemcomitans was the only organism able to upregulate Cyclin H, while P. gingivalis was the only organism that induced CDK7. Cyclin H (a.k.a CCNH) regulates CDK7, the catalytic subunit of the CDK- activating kinase (CAK) enzymatic complex. CAK activates the cyclin-associated kinases CDC2/CDK1, CDK2, CDK4 and CDK6 by threonine phosphorylation, while CAK is involved in cell cycle control and in RNA transcription by RNA polymerase II. Interestingly, the expression and activity of Cyclin H have been thought to remain constitutive throughout the cell cycle (GeneCard). This may be another example where the more pathogenic organisms have developed strategies to manipulate the cell cycle. Alternatively, this may constitute a feedback loop aimed maintaining homeostasis by upregulating the cyclins that are apparently down-regulated by both A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis.

Overall, at 2h of infection, the differential modulation of all cyclins, as well as the cell division cycle proteins would argue that S. gordonii, and F. nucleatum to a lesser extent, can stimulate the transition through the G1/S and the G2/M phases, as compared to uninfected control cells. In contrast, A. actinomycetemcomitans appeared to delay cell cycle progression, likely in response to genotoxic stresses induced by the cytolethal distending toxin (CDT).

TOLL-like receptors, JAK-STAT signaling and cytokine profiles

Gingival epithelial cells, as the first physical line of defense against the oral microflora, locally orchestrate the immune reaction through the specific recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP) by their respective Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (Akira and Takeda 2004). For example, TLR ligands include bacterial products such as lipoproteins, glycolipids and peptidoglicans (TLR2), lipopolysaccharide (TLR4), flagellin (TLR5) and bacterial DNA (TLR9). Both TLR2, TLR4 and other TLRs, are expressed in numerous oral epithelial cells (primary and transformed). However, TLR-2 and -4 remain the only two that have been detected in gingival tissue from periodontitis patients to date (Asai et al 2001b; Asai Jinno and Ogawa 2003; Brozovic et al 2006; Kusumoto et al 2004; Milward et al 2007; Mori et al 2003; Ren et al 2005; Yoshimura et al 2002). These two TLRs have been shown, in certain instances, to be transcriptionally modulated by challenges with P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum (Brozovic et al 2006; Milward et al 2007). Genetically, the polymorphism of TLR2 and TLR4 that has been observed in periodontitis patients has been suggested to contribute to an increased susceptibility to this disease (Folwaczny et al 2004; Kinane et al 2006; Laine et al 2005; Milward et al 2007; Schroder et al 2005). As presented in Supplementary Fig. 1.4, TLR2 and TLR4 were not transcriptionally modulated by any of species tested (at 2 hours of co-culture with live organisms). However, downstream events associated with TLR-signaling were clearly modulated, supporting the significant role of this pathway in host-microbe interactions. In fact, signaling through TLR2 and TLR4 was evident for all bacterial species tested.

One of the central components of the response to cytokines induction via the Toll-like receptor signaling pathways is the JAK (Janus Kinase)/STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) pathway, depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1.5, JAKs are associated with intracellular domains of several cytokine membrane receptors, and can activate members of the STAT family by phosphorelay. STAT thus activated translocates to the nucleus to modulate specific transcriptional responses (Planas Gorina and Chamorro 2006; Schindler 2002). The JAK/STAT signaling pathway is involved in a number of cellular pathways such as cell proliferation, cell cycle, apoptosis and regulation of the immune response (O’Shea et al 2004; Planas Gorina and Chamorro 2006). These pathways cross-talk, exert feedback loops, and impact each other at the transcriptional level. The molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of JAK/STAT activity are very complex and still not fully understood. There is no doubt, however, that it plays a major role in the regulation of inflammatory and immune responses to cytokines in response to infection (Planas Gorina and Chamorro 2006). There is, surprisingly, little information available on how oral bacteria modulate and/or may impinge on the JAK/STAT signal transduction pathway in the oral cavity, and how this can affect the maintenance of health and disease progression (Mao et al 2007).

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.4, infection of HIGK cells with all microbes tested invariably modulated several cytokines and their cellular surface receptors. However, the cytokine profiles varied considerably and characterized each challenging organism. As summarized in Table 2, S. gordonii up-regulated interleukin IL8 and IL23α, and down-regulated IL1α, IL1β, IL6, and IL11. In contrast, F. nucleatum up-regulated IL1α and IL23α, and down-regulated IL1β, IL8, IL11 and interferon IFNα5. A. actinomycetemcomitans-infected cells upregulated IL1α, IL1β, IL2, IL3, IL6, and IL8, but downregulated IL11 and interferon IFNα17. Furthermore, P. gingivalis-challenged cells upregulated IL1α, IL1β, IL2, IL6, IL8, IL12α, and IL12β, but down-regulated IL3. Thus, based on the early transcriptional response of HIGK, differential expression of IL1β, IL2, IL6, IL12α and IL12β (up-regulated by A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis only), and IL23α (upregulated by F. nucleatum and S. gordonii) discriminated between more and less pathogenic species. There are conflicting reports on the differential activation/repression of cytokines in oral epithelial tissues and cells by oral organisms. Notably, discrepancies are highlighted when different cell lines, time-points, strains or experimental conditions are used, and whether activity, secretion or mRNA expression is measured. Thus, while not broadly applicable across all in vitro model systems, these results provide a potential cytokine personality profile that could be used to assess the potential roles of previously uncharacterized periodontal organisms.

Table 2.

Cytokine profiles upon a 2-hours co-culture with oral microbiota1.

| IL1α | IL1β | IL2 | IL3 | IL6 | IL8 | IL11 | IL12α | IL12β | IL23α | INFα5 | INFα17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sg | down | down | down | up | down | up | ||||||

| Fn | up | down | down | up | down | |||||||

| Aa | up | up | up | up | up | up | down | down | ||||

| Pg | up | up | up | down | up | Up | up | up |

Legend: Sg, S. gordonii; Fn, F. nucleatum; Aa, A. actinomycetemcomitans; Pg, P. gingivalis. Red boxes are up-regulates whereas green boxes are down-regulated.

Numerous cytokines are located upstream of JAKs, which were transcriptionally induced by HIGK cells by S. gordonii and A. actinomycetemcomitans (JAK1), only. In contrast, STATs (STAT1 and STAT5B) were induced by both A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis, but down-regulated by F. nucleatum and S. gordonii (STAT1, STAT2 in S. gordonii only, and STAT3 in both organisms). As the action of signaling by STATS may be very transient (Planas Gorina and Chamorro 2006; Wormald and Hilton 2004), it is recognized that a transcriptional “snap-shot” at a single time point may provide only a limited insight into long term biological properties. However, the stringency of the statistical methods applied in this model system confers great confidence that the JAK/STAT pathway is indeed modulated upon infection, and apparently differs between infecting species, which warrants further dissection. For example, a recent report confirmed that P. gingivalis can block apoptotic pathways in primary gingival epithelial cells through the manipulation of the JAK/STAT pathway, ultimately modulating the intrinsic mitochondrial cell death pathways as a means of intracellular survival. Using quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, expression of STAT3 was shown to be elevated in P. gingivalis-infected cells. Also, Western analysis confirmed that the levels of phosphorylation of JAK1 and Stat3 increased upon infection (Mao et al 2007).

The ras and MAPK pathways can be stimulated in response to a trigger of JAK to further modulate cell cycle and apoptosis. This branch of the pathway was induced by both A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis, and consistently repressed by F. nucleatum and S. gordonii. Another branch downstream of the JAK sensing system is the PI3K/AKT pathway, which is an important modulator of apoptosis. AKT was found to be consistently upregulated by both A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis, relative to the level of expression found in F. nucleatum and S. gordonii. Altogether, the pattern presented above suggests that more pathogenic organisms have evolved mechanisms to directly impinge on MAPKs, thus reprogramming the cell to remain viable despite infection.

MAPK Signaling Pathway

Conceivably, infected gingival epithelial cells can either attempt to eliminate challenging microorganisms, tolerate the spread of infection and invasion, or simply induce cell death to protect neighboring cells from infection (Menaker and Jones 2003). In any of these scenarios the decisive determinant of cell behavior is the signaling system that is activated in the host cell upon infection (Finlay 1997; Kyburz et al 2003; Litchfield 2003; Sancar et al 2004; Uitto et al 2005). Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-related signal transduction pathways are among the most widespread mechanisms of eukaryotic cell regulation (activation, stress response, differentiation, and growth). MAPKs are activated following engagement of numerous cell surface receptors, and the MAPK-dependent activation of transcription factors is considered to be a prerequisite for altered gene expression in stimulated target cells (for a review, Chang and Karin 2001; Kyriakis and Avruch 2001; Walter et al 2004). There are three well-characterized subfamilies of MAPKs: the extracellular signal- regulated kinases (ERK), the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases (JNK), and the p38 family of kinases (p38 MAPKs) (Hommes Peppelenbosch and van Deventer 2003; Johnson and Lapadat 2002). ERK activation is considered essential for entry into cell cycle and, thus, mitogenesis. Activation of the JNK pathway is associated with programmed cell death or apoptosis. The p38 MAPKs regulate the expression of many cytokines and have an important role in activation of immune response (Johnson and Lapadat 2002; Zhang et al 2005). While the JNK and p38 pathways are activated by many proinflammatory cytokines and by environmental stress and lead to altered gene expression and apoptosis, the ERK MAPK pathway is induced by several growth factors and mitogens and results in control of cell proliferation through stimulation of mitosis associated protein kinases (Marshall 1999). Considerable cross-talk exists between the different MAPK pathways. The MAP kinases also interact with intrinsic heat shock proteins that are known to modulate cell behavior (Zhang et al 2001b). The activation of intracellular signaling pathways and subsequent inflammatory cytokine production has been induced by different stimuli in different cell types; however, the response induced by one stimulus cannot be extrapolated to another or from one cell type to another (Rao 2001; Zhang et al 2005).

As shown in Figure 1.2, the transcriptional profiles obtained from infected HIGK cells were characterized by very little consistency between all four species tested. Overall, F. nucleatum and S. gordonii appeared to perturb the MAPK signaling pathway’s transcriptome much less significantly than A. actinomycetemcomitans or P. gingivalis, which provided additional evidence that less pathogenic species present a greater degree of host adaptation as compared to more pathogenic species. In particular, all three MAPKs subfamilies (ERK, JNK and p38) were transcriptionally upregulated by A. actinomycetemcomitans. Several A. actinomycetemcomitans, molecules are known to be sensed through multiple MAPKs pathways. For instance, hsp60 from A. actinomycetemcomitans triggers the ERK1/2 MAPK pathway and is involved in hsp60-induced cell growth which may, in case of mucosal infection, lead to increased wound repair (Zhang et al 2001a). In addition, hsp60 released by human structural or inflammatory cells may contribute to increased cell motility in inflamed tissue. In case of tissue repair this may mean accelerated wound closure. Furthermore, hsp60-induced epithelial cell migration may lead to local invasion of infected epithelium in some mucosal infections, or to increased cell invasion in infected tumors (Zhang et al 2004). Besides hsp60, the LPS from A. actinomycetemcomitans induces rapid p44 and p42 phosphorylation (ERK 1 and ERK 2, respectively) in human gingival fibroblasts (Gutierrez-Venegas et al 2006) and activates ERK, JNK, p38 and IκBα in these cells (Bodet et al 2007; Mochizuki et al 2004). It has been shown that the induction of IL-6 by IL-1β and A. actinomycetemcomitans LPS requires signaling through multiple MAPK pathways, including MKK-3-p38α ERK, JNK and p38 MAPK in mPDL cells (murine periodontal ligament cell line). Interestingly, it has been suggested that because p38 MAPK is a key signaling intermediate utilized by LPS and IL-1- induced IL-6 expression in PDL fibroblasts, targeting p38 MAPK may have therapeutic importance for the management of chronic periodontitis (Patil Rossa and Kirkwood 2006).

Contrasting with A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis only transcriptionally up-regulated JNK. In primary oral gingival epithelial cells (GEC), previous work has confirmed that P. gingivalis can selectively target components of the MAP kinase pathways. In particular, ERK1/2, while not involved in P. gingivalis invasion of GECs, may be downregulated by internalized P. gingivalis, while the activation of JNK is associated with the invasive process of P. gingivalis (Watanabe et al 2001). Others have suggested that in endothelial cells P. gingivalis strains induced phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, degradation of IκBα, and translocation and activation of endothelial cell NF-κB, with subsequently increased transcription and translation of E-selectin and ICAM-1. Specifically, it was reported that p38 is strongly activated during inflammatory reactions and appears to be of central importance during LPS-mediated signal transduction (Hippenstiel et al 2002; Walter et al 2004), triggering a cascade of events that could lead to endothelial damage as well as local and systemic inflammation (Walter et al 2004). However, oral keratinocytes respond to exogenous HSP60 by triggering expression of the inflammatory cytokine IL-1β through activation of p44/42 MAP kinase. Oral keratinocytes are also a source for self-HSP60 and the secretion of this protein may be differentially modified by LPS from different bacterial species (Pleguezuelos et al 2005). In contrast, down-regulation of IL-8 mRNA by P. gingivalis involved MEK/ERK, and NF-κB but not MAPK p38 pathways. (Huang et al 2004; Watanabe et al 2001).

It has previously been shown that NF-κB, p38 and the MEK/ERK pathways are involved in IL-8 mRNA induction by F. nucleatum. MAPK p38 and JNK signaling pathways were found to be involved in the upregulation of the antimicrobial peptide human β-defensin-2 following stimulation with F. nucleatum (Huang et al 2004; Krisanaprakornkit et al 2000; Krisanaprakornkit Kimball and Dale 2002). Stimulation of HGECs by F. nucleatum cell wall is known to activate several signal transduction pathways including NF-κβ, JNK, and MAPK p38 (Chung and Dale 2004; Krisanaprakornkit Kimball and Dale 2002). The up-regulation of IL-8 by F. nucleatum involved largely the activation of NF-κβ and to some extent MAPK p38 and MEK/ERK pathways (Huang et al 2004). In a human gingival epithelial cell model, it was shown that F. nucleatum activated p38 and JNK pathways, whereas it had little effect on ERK1/ERK2 in the regulation of human beta-defensin-2 (Krisanaprakornkit Kimball and Dale 2002). F. nucleatum can exert its pathogenic potential in the periodontal tissue (and other sites) by activating multiple cell signaling systems that lead to stimulation of collagenase 3 expression and increased migration and survival of the infected epithelial cells (Uitto et al 2005). In contrast with these studies, the infection of HIGK cells by F. nucleatum had little effect on ERK, JNK or p38. Similarly, S. gordonii was only found to up-regulate p38.

In the maintenance of oral health or during disease development, accumulating evidence supports the central role of MAPKs. Their significant differential regulation by all bacteria studied to date remains particularly compelling evidence that they are key to various (and diverse) responses to infection. Indeed, MAPKs transduction is involved in maintaining the balance between cellular proliferation and cellular death, thus fine-tuning cellular turn over and directing wound healing and clearance of invading organisms. It remains to be investigated whether the transcriptional discrepancies noted above reflect the transient nature of MAPKs.

TGF-β Signaling Pathway

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β is a multifunctional cytokine that is involved in various cellular functions such as angiogenesis, immune suppression, extracellular matrix synthesis, apoptosis and cell growth inhibition. (Gurkan et al 2006; Noda et al 1988; Postlethwaite et al 1987; Prime et al 2004; Wahl et al 1987; Yamaji et al 1995). Of particular interest in the context of host-microbiota interactions, TGF-β is one of the key cytokines with pleiotrophic properties that has both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory features in regulation of the inflammatory infiltrate and in resolution of inflammation (Gurkan et al 2006; Wahl and Chen 2005). Furthermore, TGF-β affects cell proliferation and the differentiation process, making it an important cytokine in wound healing, tissue remodeling and regeneration (Gurkan et al 2006; Sporn and Roberts 1993) and in enhancing epithelial barrier functions (Howe et al 2005). TGF-β has a central role in regulation of collagen metabolism in physiologic as well as pathologic conditions, like periodontitis (Gurkan et al 2006; van der Zee Everts and Beertsen 1997). Moreover, reduced TGF-β levels at a wound area may lead to impairment in healing (Gurkan et al 2006). Further, it is likely that the coupling of bone formation and bone resorption is mediated by local factors in the bone microenvironment. TGF-β acts as a regulatory growth factor for osteoblasts, and it has been suggested that it affects their functions (Pfeilschifter D’Souza and Mundy 1987; Pfeilschifter Seyedin and Mundy 1988; Wahl et al 1988; Yamaji et al 1995). It has also been suggested that following stimulation with LPS, TGF-β accumulates in inflammatory lesions and suppresses immune cell function, but does not lead to tissue destruction (Yamaji et al 1995).

Compared to healthy subjects, increased TGF-β levels are found in gingival tissues and gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) samples from patients with gingivitis, chronic periodontitis, generalized aggressive periodontitis and peri-implantitis (Buduneli et al 2001; Cornelini et al 2003; Ejeil et al 2003; Gurkan et al 2006; Steinsvoll Halstensen and Schenck 1999; Wright Chapple and Matthews 2003). Genetic polymorphisms in the TGF-β gene have been shown to interfere with the production, secretion or activity of this growth factor (Atilla et al 2006; Awad et al 1998; Li et al 1999) and this has been associated with risk for systemic diseases including cardiovascular diseases and rheumatoid arthritis, which are related to periodontitis in terms of chronic inflammatory processes (Atilla et al 2006; Garcia Henshaw and Krall 2001; Mercado Marshall and Bartold 2003; Sugiura et al 2002). Epithelial surfaces up-regulate TGF-β in response to infection with other non-oral bacterial pathogens, including Yersinia, Cryptosporidium, EHEC O157:H7 and EPEC (Howe et al 2005). Collectively, this response may reflect the host’s attempt to restore cell integrity or to avoid cell destruction upon microbial challenges (Bohn et al 2004; Howe et al 2005).

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.6, signaling through TGF-β functions through the activation of ERK, MAPK and SMAD signaling, and affects a plethora of downstream functions. Infection of HIGK cells with all microbes tested significantly modulated several components of the TGF-β signaling pathway. Notably, the pattern of expression presented striking differences related to more/less overt pathogenicity. Most genes were down-regulated in S. gordonii and F. nucleatum-infected HIGK cells. In contrast, A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis consistently up-regulated most genes affected. The most significant differences were in TGF-β itself (down-regulated by P. gingivalis) and in the level of expression of Smad1/5/8, which was down-regulated by A. actinomycetemcomitans but up-regulated by P. gingivalis. In sum, this response appeared to correlate the inflammatory potential of oral pathogenic species, and may reflect the hosts attempt to restore cell integrity or to avoid cell destruction upon microbial challenges with overt pathogens, as previously suggested in respiratory and gastro-intestinal systems (Bohn et al 2004; Howe et al 2005).

Wnt Signaling Pathway

The Wnt gene family is a group of highly conserved developmental genes involved in cell growth regulation, differentiation and organogenesis. Beta-catenin, a central component of this pathway, which also links cell adhesion and cell differentiation; it stabilizes cell-cell adhesion by anchoring cadherins via α-catenin to the cytosekeleton (Gradl Kuhl and Wedlich 1999; Kemler 1993; Takeichi 1995). Wnt pathway signaling is mediated via interactions between β-catenin and members of the LEF/TCF family of transcription factors (Behrens et al 1996; Gradl Kuhl and Wedlich 1999; Huber et al 1996; Lo Muzio et al 2002; Molenaar et al 1996). The Wnt/Wg signaling cascade includes a membrane-integrated receptor of the frizzled family, which activates the phosphoprotein dishevelled (Dsh, a.k.a Dvl), leading to inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3b. Because β-catenin is a substrate of this serine/threonine kinase, it remains hypophosphorylated upon Wnt signaling and accumulates in the cytoplasm. This promotes β-catenin binding to LEF-TCF transcription factors. The β-catenin–LEF-TCF heterodimer enters the nucleus and is able to activate or repress gene transcription (for detailed reviews, see Cavallo Rubenstein and Peifer 1997; Gradl Kuhl and Wedlich 1999; Gumbiner 1995; Kuhl and Wedlich 1997).