Abstract

The calmodulin (CaM) family is a major class of calcium sensor proteins which collectively play a crucial role in cellular signaling cascades through the regulation of numerous target proteins. Although CaM is one of the most conserved proteins in all eukaryotes, several features of CaM and its downstream effector proteins are unique to plants. The continuously growing repertoire of CaM-binding proteins includes several plant-specific proteins. Plants also possess a particular set of CaM isoforms and CaM-like proteins (CMLs) whose functions have just begun to be elucidated. This review summarizes recent insights that help to understand the role of this multigene family in plant development and adaptation to environmental stimuli.

Key Words: calcium signaling, calmodulin, calmodulin-like protein, calmodulin-binding proteins, plant development, biotic and abiotic stress

Introduction

Calcium (Ca2+) is an element that is crucial for numerous biological functions. In addition to its key roles in the structural integrity of the cell wall and the membrane system, it has been shown to act as an intracellular regulator in many aspects of plant growth and development including stress responses.1–3 Involvement of Ca2+ as a second messenger to trigger physiological changes in response to developmental and environmental stimuli is the subject of intense investigations, and several reviews present the different aspects of Ca2+ signaling in plants.4–8 This update focuses on calmodulin, an essential Ca2+ transducer in eukaryotic cells and its functions in plants.

As high Ca2+ concentrations can be toxic to cellular energy metabolism, cytosolic Ca2+ level in unstimulated cells is maintained at a submicromolar concentration by removing Ca2+ ion from the cytosol to either the apoplast or the lumen of intracellular organelles such as the vacuole or the endoplasmic reticulum. Transient elevations in cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations occur via an increased Ca2+ influx and a rapid return to the basal level by Ca2+ efflux in response to a variety of stimuli including hormones, light, gravity, abiotic stress factors or interactions with pathogens and symbionts.6 These Ca2+ pulses are briefly available to act as cellular signals and exert changes in cellular functions.4 Given that a myriad of stimuli uses Ca2+ as an intracellular intermediate, a central question on Ca2+ signaling is how this signal carrier conveys information from a perceived stimulus and controls the specificity of cellular responses. In recent years, significant progress have been made in elucidating the patterns of Ca2+ signals and the relays that convert these messages into cellular responses. Using calcium imaging techniques, in vivo measurements of Ca2+ changes in plant cells have revealed that different stimuli can elicit distinct Ca2+ signals, also referred to as Ca2+ signatures.9 Patterns of Ca2+ signatures may differ in the amplitude, duration, localization and frequency of Ca2+ oscillations, and there is evidence that these parameters are used to encode the information required to initiate specific and appropriate responses for a given stimulus.10 For instance, analyses of the Arabidopsis det3 mutant have demonstrated that cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations are required for stomatal closure. In guard cells of this mutant, external Ca2+ and oxidative stress elicit sustained Ca2+ increases instead of Ca2+ oscillations observed in wild-type cells, and stomatal closure is abolished. However, experimentally imposing Ca2+ oscillations in the det3 guard cells restores the stomatal closure, indicating that stomatal closure is programmed by Ca2+ oscillation parameters. The sub-cellular localization of Ca2+ signals may also affect the subsequent response, and nuclear Ca2+ signaling is of particular interest. Ca2+ changes in the nucleus can occur independently from cytosolic Ca2+ signals, indicating that the nucleus has an Ca2+ autonomous system.11 Moreover, Ca2+ signals in the nucleus or the cytosol can result in specific changes in gene expression.12

Ca2+ signals are deciphered by various Ca2+-binding proteins that convert the signals into a wide variety of biochemical changes.13 Most of these proteins harbor the EF-hand motif, a helix-loop-helix structure binding a single Ca2+ ion. Plants have evolved a large repertoire of EF-hand proteins which is subdivided in several classes on the basis of the number and organization of EF-hand motifs, and the presence of other functional domains. To date, much of our knowledge on EF-hand proteins that function as transducers of Ca2+ signals in plants comes from information on calmodulin (CaM), calcineurin B-like protein (CBL) and calcium-dependent protein kinase (CDPK). CDPK is a class of plant protein kinases that contain a kinase domain and a Ca2+-binding domain bearing 4 EF-hands. The activity of CDPK is stimulated by Ca2+ suggesting that CDPKs may function in Ca2+-mediated signaling pathways.14 Plants possess other classes of Ca2+ regulated protein kinase such as the Ca2+/CaM dependent kinase (CCaMK) that differs from CDPK in several respects.15 CCaMK harbors a C-terminal regulatory domain similar to visinin, a Ca2+ binding domain consisting of 3 EF-hands, and it can be activated by CaM. Other Ca2+-binding proteins including CaM and CBL lack an effector domain such as the kinase domain of CDPK and CCaMK. CBL and CaM are small proteins with three and four EF-hand motifs respectively, which function as sensor relays via Ca2+-dependent interaction with effector proteins.16 CBL belongs to a family of plant proteins related to the neuronal Ca2+ sensor and the regulatory B subunit of calcineurin. To transmit Ca2+ signals, CBLs interact with a family of protein kinases similar to the SNF-protein kinase from yeast, and modulate their kinase activity.17 CaM was identified in plants and animals more than two decades ago and named calmodulin for CALcium MODULating proteIN.18 A large repertoire of CaM target proteins with diverse cellular functions is found in both plants and animals, indicating that CaM regulates a wide variety of cellular events.5,8,19 While a single CaM gene is found in yeast, plants and vertebrates harbour a CaM gene family which includes a typical and structurally conserved CaM throughout both kingdoms.20,21 In addition to the evolutionarily conserved form of CaM, plants possess an extended family of CaM isoforms and CaM-like proteins. This is one of the striking differences between Ca2+ signaling in plants and animals. Although mammals possess a few CaM-like proteins, these are closely related to the typical CaM.22,23 Moreover, CaM gene family in humans and rats is composed of 3 non-allelic members that encode an identical CaM protein. In plants, genetically distinct CaM isoforms exhibiting about 90% sequence identity can be found within a species, and many distantly related proteins annotated as CaM-like have been deduced from plant genome sequence data. These proteins are now being actively characterized, and recent data indicate that at least some of them have a role in signal transduction and further extend the Ca2+/CaM signaling system in plants. Our intention here is to summarize most recent advances on the Ca2+/ CaM messenger system in plants.

CaM and CaM-Like Proteins in Plants: An Extended Family

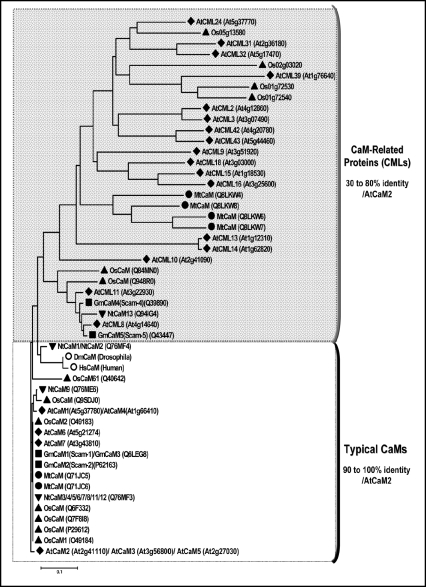

The development of genomic approaches and sequencing projects give us an overview of the diversity of genes encoding Ca2+-binding proteins in the plant genomes. Genome analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana displays a large number of genes (∼250) encoding proteins harbouring at least one predicted EF-hand motif.13 Seven genes (AtCaM1 to 7) have been reported to encode 4 CaM isoforms that share 97 to 99% amino acid identity between each other and are called “typical CaM” because of their high identity with CaM found in vertebrates or insect such as drosophila (Fig. 1). Interestingly, plants also possess numerous CaM-related proteins (CMLs) exhibiting significant structural divergences with the typical CaM (Fig. 1). According to McCormack et al.,24 CMLs are defined by the presence of 2 to 6 predicted EF-hands motifs, by the absence of any other identifiable functional domain and at least by 15% amino acid identity with CaMs. Upon these criteria, 50 CML genes can be identified in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. The progress of plant genomes sequencing indicates that this large diversity is encountered in all plant species (i.e., rice, Medicago, , soybean…) (Fig. 1) and questions about the meaning of this CaMs and CMLs diversity in plant genomes.

Figure 1.

Neighbour joining tree based on amino acid similarities of CaM and CML proteins from different plant species. Sequences of CaM and CML proteins were downloaded from SwissProt or from the TIGR and subjected to phylogenetic analysis using MEGA version 3.1 software.103 Alignments of CaM and CML proteins ranging from 150 to 200 amino acids and harbouring 4 EF-hand from different plant species were constructed using the multiple sequence alignment mode of ClustalW with protein matrix blosum. Protein tree was constructed by the neighbour-joining method implemented in the MEGA 3.1 program. The distance indicated by ‘0.1’ refers to the percent sequence divergence as calculated by ClustalW. AtCaM/AtCML refer to Arabidopsis thaliana CaM or CML (♦); Rice calmodulins (▴) are named OsCaM for Oryza sativa CaM or according to their TIGR accession; NtCam: Nicotiana tabacum CaM (▾); MtCaM: Medicago truncatula CaM (•); GmCaM or Scam refer to Glycine max or soybean CaM (▪); HsCaM: Homo sapiens CaM (P62158) (○); DmCaM: Drosophila melanogaster CaM (P62152) (○). The percentage of identity is indicated by using AtCaM2 as reference.

Sequence analysis of CMLs proteins indicate that amino acids substitutions can be observed in the EF-hand loop motif suggesting that these motifs are more or less active in Ca2+ coordination and consequently they could modify protein Ca2+ affinity. However, experimental evidence of the functionality of predicted EF-hands in CMLs was performed for only a restricted number of these proteins.25 Differences between these proteins are not restricted to the EF-hand motifs and can account for a differential interaction/activation of CaM target by diverse CaM isoforms and CMLs. It was shown that NtCBK2, a tobacco CaM-binding protein kinase, is differentially regulated by diverse CaM isoforms.26 Three tobacco CaM isoforms (NtCaM1, NtCaM3 and NtCaM13) (Fig. 1) bind to NtCBK2, but with different dissociation constants, indicating that NtCBK2 has a higher affinity for NtCaM3 and NtCaM13 than for NtCaM1. Moreover, differential activation of a NAD kinase (NADK) by CaM and CML proteins has also been reported.27 In Arabidopsis, NADK was fully activated by typical CaM in the presence of Ca2+ but displayed differential responsiveness to eight Arabidopsis CMLs proteins (AtCML 2-3-10-18-39-42-43-47). Interestingly, AtC-ML10 which is about 64% identical to the typical CaM but possesses 42 amino acids in its C-terminal extension is able to fully activate native NADK in vitro. By contrast, the more divergent CML proteins tested in this work are only able to weakly activate NADK above background levels.27 Collectively, these data show that CaM and CMLs differ in their ability to bind and activate known CaM-regulated enzymes in vitro.

The diversity of CaM or CMLs could also be explained by a specific tissue or sub-cellular location of these proteins. A cytosolic location is generally associated to the typical isoform of CaM and several examples also report that CaM is present in the nucleus.12 Few reports also described the presence of CaM in the peroxisome28 and in the extracellular matrix29 and question about functionality and role of CaM and/or CMLs in such compartments. Recently, AtCML18 was identified as a vacuolar protein able to interact with the C-terminus region of AtNHX1, a vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter.30 It was also shown that PhCaM53 and OsCaM61, two CMLs from Petunia and rice, exhibit an extended C-terminal basic domain which is required for efficient prenylation and particular subcellular location of the proteins.31,32 Prenylated PhCaM53 associates with the plasma membrane, and the non-prenylated form is located into the nucleus. Expression of wild-type PhCaM53 or a non-prenylated mutant protein in plants causes distinct morphological changes. These findings suggest that CaM and CML may exert different functions through their binding targets that can be located in different cellular compartments. Protein sequence analyses of CMLs indicate that many of these proteins present extra-sequences at the N- or C-terminus regions but the biological roles of these sequences need to be elucidated.

Finally, global expression analyses recently undertaken by microarray approaches show that the major part of CaMs and CMLs genes do not present redundant patterns during plant development or in response to environmental factors.33 According to the relative abundance of a specific CaM isoform in cells, a given Ca2+ signal might lead to different biochemical consequences by virtue of its CaM isoform-dependent selective activation/inhibition of particular target proteins. Now, the recurring question is to decipher the biological meanings associated to this large family of calcium sensors. A part of the answer could come from the identification of target proteins regulated by these CaMs and CMLs.

Downstream Target Proteins: Functional Diversity of CaM Targets

Much effort has been dedicated in isolating downstream target proteins by the use of CaM as a bait in protein-protein interaction screening. CaM-regulated (or associated) proteins identified from plants now include several metabolic enzymes, cytoskeleton-associated proteins, ion transporters, chaperonins, transcription factors, protein kinases/phosphatases and proteins of unknown function (Fig. 2). A detailed list of CaM binding proteins (CaMBP) has been described.8 As this list regularly increases, examples of recently identified CaM targets in plants are presented in Table 1. Up to now, about 80 CaMBPs have been identified in plants. The typical CaM isoform is present in all eukaryotes and it is not surprising to find, among the global list of CaMBPs, about one third of homologous proteins between plants and other organisms that are regulated by CaM. The others proteins that compose this list can be ranged in two classes, those having homologs in other organisms but known to be CaM-regulated only in plants and those that correspond to plant specific proteins. Collectively, this strongly suggests that Ca2+/CaM pathways are highly diversified in plants compared to others organisms. The list provided in Table 1 indicates that the repertoire of target for the typical CaM still increases but it is interesting to note that CaMBPs interacting with non-typical CaMs, such as the vacuolar Na+/H+ exchanger AtNHX130 and AtMYB2, a transcriptional activator from Arabidopsis,34 are emerging.

Figure 2.

Calcium signaling with CaMs and CMLs. In response to environmental and developmental stimuli, a transient elevation of Ca2+ concentration can be observed in the cytosol as well as in other cellular compartments. These Ca2+ variations can be decoded by a wide range of Ca2+ sensors such as the typical CaM and CMLs proteins which are highly abundant in plant cell. Some of these proteins have been shown to interact and modulate the activity of downstream target proteins to relay the Ca2+ message and to initiate biochemical, cellular and physiological responses. Many of these targets have been identified as typical CaM binding proteins and in most cases their interaction with CMLs need to be examined.

Table 1.

Examples of recently identified CaM-binding proteins from plants

| Proteins | CaM binding properties | Biological function |

| Ion transporter | ||

| AtNHX1 | ||

| Na+/H+ transporter (30) | - binds a CML isoform (AtCML18), but not a typical isoform of CaM | - Ca2+/CaM decreases the Na+/K+ selectivity ratio of |

| - CaM binding domain located in the vacuolar lumen | AtNHX1 | |

| Enzymes | ||

| DWF1 | - binds typical CaM isoform but not the CML isoform AtCML9 | - loss of CaM binding alters in vivo function of DWF1 |

| Cytochrome P450-like-enzyme (42) | - CaM binding domain is not conserved in animals homologues | - involved in brassinosteroid biosynthetic pathway |

| Peroxidase (98) | - binds typical CaM isoform | - Ca2+/CaM stimulates peroxydase activity |

| AtUBP6 | - binds typical CaM isoform (AtCaM2) | - protein degradation and/or stabilization |

| Ubiquitin-specific protease (99) | - CaM binding domain may be conserved in animals homolog | |

| Regulator of gene expression | - CaM isoform differentially modulates the DNA binding | |

| AtMYB2 | activity | |

| Transcriptional activator (34) | - binds typical (GmCaM1) and divergent (GmCaM4) CaM from Soybean | - involved in the regulation of salt and dehydration |

| - CaM binding domain is conserved in some other MYB proteins | responsive genes | |

| AtWRKY7 | ||

| Transcription factor (100) | - binds typical CaM isoform | |

| - CaM binding domain is conserved in some other WRKY factors | ||

| AtCPSF30 | ||

| Nuclear RNA binding protein (101) | - binds typical CaM isoform (AtCaM6) | - RNA binding activity is inhibited by Ca2+/CaM binding |

| Other proteins | ||

| IQD 1 Nuclear protein (102) | - binds typical CaM isoform | - positive regulator of glucosinolate accumulation |

| AtBAG6 | ||

| IQ domain/BAG domain containing | ||

| protein (78) | - binds typical CaM isoform in absence of Ca2+ | - inducer of cell death |

Up to now, screening for plant CaMBPs have been mainly made by using the typical CaM isoform as a bait35 and it would be of great interest to use CMLs as baits to identify more targets. Recent efforts in plant genome analyses have produced large quantities of genomic and cDNA sequences which could be exploited to estimate the complete set of CaM-binding proteins found in a genome by searching for the presence of CaM-Binding Domain (CaMBD) in deduced protein sequences. CaM is known to bind to a small region of many proteins composed by basic and hydrophobic residues that form a basic amphiphilic-helice.36 A sequence compilation of CaM targets has led to define several CaMBDs based on the distribution of these hydrophobic residues. The CaMBD that are often encountered, belong to the 1–10 and 1–14 so-called motifs which are known to bind CaM in presence of Ca2+.36 However, another CaMBD was also described and named the IQ motif which typically binds CaM in the absence of Ca2+ and dissociates by increased level of cytosolic Ca2+, although there are some exceptions.37 A very useful web-interface (The Calmodulin Target Database, http://calcium.uhnres.utoronto.ca/ctdb) was developed to identify, in a protein sequence, the putative sites that could bind to CaM.38 This database is composed by CaMBDs discovered in proteins able to interact with the typical CaM. Recently, a new approach, based on solved structures of CaM to predict CaMBDs have been described and opens new opportunity to reveal others CaMBPs.39 However, all the CaMBPs do not present such motifs and no consensus amino acid sequence has emerged from the comparison of the CaMBDs identified in CaMregulated proteins and it is not possible to deduce all plant CaM and CML targets only by in silico approaches.35 This might be achieved by developing new protein screening approaches, such as proteome chips already available for yeast40 or mRNA display techniques as recently used for identifying CaMBPs from human.41

Physiological Functions of CaM and CML

Expression data for CaM multigene family in plants indicate that CaM and CML genes are actively and differentially expressed over developmental stages, in various organs and in response to many different stimuli. Importantly, molecular and genetic studies now provide strong evidence for the involvement of CaM, CML and their downstream targets in diverse aspects of plant development and plant responses to biotic and abiotic stimuli. Recent data on these topics are presented below.

Plant Development

Interesting data implying CaM target proteins in plant growth and development have been recently obtained by forward and reverse genetics. CaM was found to interact with Arabidopsis DWF1, a cytochrome P450 like enzyme.42 This protein catalyzes an early step in the biosynthesis of brassinosteroid, a plant-specific steroid hormone which is essential for plant growth.43,44 Using Arabidopsis lines overexpressing DWF1, an in vivo crosslinking and coimmunoprecipitation strategy revealed that interaction between DWF1 and CaM does occur in planta. Furthermore, an Arabidopsis mutant lacking DWF1 activity exhibits a dwarf phenotype. This phenotype is due to deficient levels in brassinosteroids and it can be suppressed by the addition of exogeneous brassinolide. Interestingly, complementation with DWF1 impaired in CaM binding does not rescue the mutant phenotype, demonstrating that CaM is critical for DWF1 function in planta. DWF1 orthologues from other plants contain a similar CaM binding domain, suggesting that regulation of this protein by Ca2+/CaM is common in plants. Other important enzymes, DWF4 and CPD involved in brassinosteroid biosynthesis were also found to be CaM-binding proteins, indicating that CaM might exert several regulatory controls on the biosynthesis of brassinosteroid. Because null mutations in DWF445 and CPD46 genes cause severe alterations in plant morphology and development, it will be interesting to examine the importance of CaM binding to these enzymes by complementation experiments. Thus, the identification of mutations in morphological mutants can reveal key roles of CaM target proteins and provide valuable tools to investigate Ca2+ signaling during plant development.

Implication of CaM binding proteins in reproductive development is also well documented. A tobacco Ca2+/CaM binding protein kinase (NtCBK1) was reported to function as a negative regulator of flowering.47 NtCBK1 gene is expressed in the shoot apical meristem during vegetative growth, but its expression in the meristem is dramatically decreased after floral determination, suggesting a role of this protein kinase in the transition to flowering. This assumption has been confirmed by overexpressing NtCBK1 in transgenic tobacco plants where maintenance of high levels of NtCBK1 in the shoot apical meristem delayed the switch to flowering. Several tobacco CaMs including the typical NtCaM1/2 isoforms and the divergent NtCaM13 can stimulate the in vitro kinase activity of NtCBK1, but the importance of modulation of the kinase activity by CaM in the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth remains to be examined. Other protein kinases known to interact with CaM include the S-locus receptor kinase (SRK) which is involved in pollen-pistil interactions by acting as the female determinant of the self-incompatibility response in Brassica.48 SRK is located in the plasma membrane of the stigmatic papillar cells and it mediates self-pollen recognition by binding to a small peptide present in the pollen coat.49,50 CaM interacts in a Ca2+-dependent manner with the kinase domain of SRK, but this interaction has no direct effect on SRK kinase activity. In addition to SRK, CaM was found to bind to the cytoplasmic domain of distantly related receptor kinases such as RLK4, AtCaMRLK and CLV1, but in all cases, the role of this interaction is unknown.48,51 A potential role of CaM in the internalization of plant receptor kinases could be proposed as suggested by studies on animal receptors.52,53

Finally, two CaM targets, Arabidopsis NPG1 and ACA9 which are expressed primarily in pollen, were found to be essential for pollen development and fertilization.54,55 NPG1 belongs to a plant-specific family of CaM binding protein whereas ACA9 is a member of the family of autoinhibited Ca2+-ATPase that is activated by Ca2+/CaM. Analysis of Arabidopsis mutant revealed that pollen carrying a NPG1 mutant allele does not germinate. However, the mode of action of NPG1 in controlling pollen germination needs to be clarified. In addition to the CaM binding domain, NPG1 protein contains tetratricopeptide repeats, a motif known to be involved in protein-protein interaction. Therefore, NPG1 likely interacts with other proteins, and further studies on identification of these proteins will be helpful to precise the function of NPG1. A key role for ACA9 was also observed in Arabidopsis mutants where gene disruption of ACA9 results in a semisterile phenotype. This phenotype comes from a reduced growth potential of the mutant pollen and a high frequency of aborted fertilization when the pollen tube reaches the embryo sac. This finding suggests that control of Ca2+ dynamics by ACA9, a plasma membrane Ca2+ transporter is essential for pollen tube growth and fertilization. This is consistent with previous reports indicating that the establishment of a Ca2+ gradient at the tip of pollen tube is important for tube elongation and directional growth.56,57 Moreover, CaM was found to be highly active at the pollen tube apex.58 Alterations in CaM activity by the use of CaM antagonists result in a misguidance of pollen tube growth, and genetic evidence now demonstrate that CaM targets such as ACA9 and NPG1 are key players in Ca2+ signaling during pollen development.

Plant-Microbe Interactions

A number of studies suggest that Ca2+ and CaM are critical players in plant responses to invading pathogens and symbionts. Significant progresses on this topic are presented below.

To ensure nitrogen supply required for plant growth, many legumes enter a symbiotic interaction with nitrogen-fixing bacteria which can reduce nitrogen to ammonia.59 Establishment of the legume/rhizobia symbiosis requires a signaling molecule termed Nod factor that is produced by the Rhizobium bacteria and recognized by the root hair cells of the host plant.60 Early events in this recognition include Ca2+ responses that are separated both spatially and temporally.61 An initial Ca2+ flux occurs at the tip of the root hair, then repetitive cytosolic oscillations of Ca2+ or Ca2+ spiking appears in the region surrounding the nucleus. Analysis of mutations that disrupt the formation of nitrogen-fixing nodules on the roots of M. truncatula were found to be highly informative of the role of Ca2+ in the transduction of Nod factor signal.62,63 DMI3, an essential gene for Nod factor signaling, functions downstream of Ca2+ spiking. DMI3 was identified as a member of CCAMK family.64,65 A highly similar protein kinase from lily was shown to be activated by Ca2+ in a two steps process.66 First, interaction of Ca2+ with the EF-hands of the visinin-like domain results in the autophosphorylation of the kinase which leads to increased affinity for CaM. In a second step, Ca2+/CaM binds to the kinase and allows substrate phosphorylation. This suggests that DMI3 might recognize and transduce complex Ca2+ signatures such as Ca2+ spiking. Interestingly, it was recently reported that an ortholog of DMI3 from rice can restore nodule formation in dmi3 mutant indicating that CCaMK from non legumes can interpret the calcium signature generated by Nod factors.67 The critical function of DMI3 for root nodule formation gives also the opportunity to assess the significance of Ca2+ and CaM in the transduction of Nod factor signal by complementation experiments with DMI3 impaired in Ca2+ and CaM binding. Furthermore, the nuclear localization of DMI3 suggests that putative targets of this protein kinase are transcription factors mediating Nod factor-induced gene expression. Recent studies of additional mutants that are defective in nodules formation has led to identify transcription factors that act directly downstream of DMI3; however, their interaction with DMI3 is still lacking.68,69 Overall, these findings provide novel insights on the role of CCaMK in plants. Global gene expression profiles in nodules and analysis of Medicago cDNA libraries indicate that CaM family is also implicated at later stages of symbiosis. Several CaM and CML genes from Medicago and Lotus were found to be expressed in nodules.70,71 A remarkable feature of nodule-specific CML proteins is the presence of a predicted N-terminal extension which potentially directs these proteins out of the cytoplasm into the symbiosome space, a matrix-filled space surrounding the bacteroïd.72 Further studies on the role of these CMLs are needed and this should provide new information on Ca2+-dependent processes in symbiosis.

Plants have evolved diverse strategies to defend themselves against pathogens, and increasing evidence implicates Ca2+ signaling in plant defense responses. A rapid increase in cytoplasmic free Ca2+ levels is a common response to pathogen infection, and Ca2+ signal has been shown to be essential for the activation of defense responses such as the induction of defense-related genes and hypersensitive cell death. Recently identified elements of plant defense signaling pathways include diverse CaMs, CMLs and CaM-binding proteins. Among CaM/CML genes, soybean SCaM4 and SCaM5, and Arabidopsis AtCML9 have been reported to be one of the earliest genes induced by infection and pathogen-derived elicitors (refs. 73, 74 and unpublished data from our group). Soybean SCaM4 and SCaM5 exhibit about 78% identity to typical CaM while Arabidopsis AtCML9 shares only 50% identity (Fig. 1). Gene expression analysis in diverse plants has revealed that additional CML genes including bean Hra32, tobacco ACRE-31, tomato APRI-34 are responsive to pathogens.75–77 In few cases, involvement of CaM isoforms in plant defense responses has been demonstrated by functional studies in transgenic plants. For instance, constitutive expression of soybean SCaM4 and SCaM5 in tobacco and Arabidopsis results in the activation of pathogenesis-related genes and an enhanced resistance to a wide spectrum of pathogen, whereas soybean SCaM1 and SCaM2, two highly conserved isoforms do not have these properties.73 Such observations suggest that divergent CaM isoforms have specific functions leading to disease resistance. Although downstream targets of soybean SCaM4 and SCaM5 are still unknown, involvement of several CaM-binding proteins in plant defense responses is well documented. A recently identified CaM-binding protein, AtBAG6 was found to induce programmed cell death in plants.78 Leaves of Arabidopsis expressing AtBAG6 develop disease-like necrotic lesions. This phenotype resembles the hypersensitive response, a localized programmed cell death of plant cells that occurs at the site of pathogen infection and contributes to restrict pathogen growth and spread. AtBAG6 is a member of BAG domain protein family that was originally identified in mammals due to their ability to interact with the antiapoptotic protein BCL2 and promote cell survival.79 Conversely, AtBAG6 is an inducer of cell death and further identification of components associated to AtBAG6 is needed to elucidate the mechanism by which this protein regulates cell death. Importantly, AtBAG6 was shown to bind CaM in the absence of Ca2+, but not in its presence. This interaction occurs through a CaM-binding IQ motif, and single amino-acid changes within this motif abrogate CaM binding and cell death in plants. These data strongly suggest that CaM regulates cell death in plants.

Additional studies have revealed that mutations in other CaM binding proteins cause severe alterations in defense responses to pathogen infection. Cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (CNGCs) are a class of ion transport proteins containing a cytoplasm-localized cyclic nucleotide binding domain and an overlapping CaM binding site at the C-terminus of the polypeptide.80,81 Plant genomes contain multiple genes encoding putative CNGC subunits that are believed to assemble into heterotetramers to form functional channels. These channels are permeable to monovalent and divalent cations including Ca2+, and their activation by cyclic nucleotides can be blocked by Ca2+ and CaM.82 Plants carrying mutations in different members of CNGC family such as Arabidopsis CNGC2, 4, 11 and 12 were found to exhibit altered responses to pathogen infection and a constitutive activation of defense mechanisms.83–86 Moreover, mutations in these genes result in some differences in disease resistance of the mutated plants, indicating that they do not play redundant roles during pathogen infection. This suggests a critical role of ion fluxes mediated by CNGCs in defense signaling but their positioning in the pathogen response signaling network is still unclear. Other studies have revealed the involvement of CNGCs in plant tolerance to heavy metals.87,88 When overexpressed in transgenic plants, NtCBP4, a tobacco member of CNGC family confers a higher sensitivity to Pb2+ than the wild-type plants. In contrast, expression of a truncated form of this protein from which the CaM binding domain and the cyclic nucleotide binding site were removed leads to higher tolerance to Pb2+, indicating the importance of this regulatory domain. Collectively, these findings reveal key roles of plant CNGCs and provide useful tools for further dissection of cyclic nucleotide and Ca2+ signaling pathways mediating plant defense.

Elegant studies have recently demonstrated the significance of CaM interaction with MLO (powdery mildew-resistance gene o) protein in pathogen challenge. Many fungal pathogens must enter plant cells for successful colonization. This critical phase requires particular host proteins such as MLO proteins.89 In Arabidopsis and barley, plants lacking a functional MLO are resistant to penetration of powdery mildew fungus in leaf epidermal cells, indicating a crucial role of this protein in plant susceptibility.90 MLO is a plasma membrane integral protein that binds CaM in its C-terminal cytoplasmic tail, a domain relatively well conserved among MLO family members.91 Interestingly, site-directed mutations in barley MLO that compromises CaM binding reduce the susceptibility-conferring activity of MLO in planta, thus demonstrating the importance of CaM in MLO function.92 Analysis of fluorescently tagged protein expressed in barley leaf epidermal cells showed a focal accumulation of MLO protein at sites of attempted fungal penetration, thus revealing a specific redistribution pattern of this membrane-localized protein upon pathogen challenge. Furthermore, in planta fluorescence resonance energy transfer analysis revealed that MLO protein recruits cytoplasmic CaM at penetration sites coincident with successful host cell entry.93 Importantly, energy transfer between the two tagged-proteins was shown to require an intact CaM binding domain in MLO protein. Overall, these findings demonstrate that a fungal pathogen can trigger the formation of plasma membrane micro-domain containing particular proteins. Elucidation of the biochemical function of MLO should help to understand the effect of CaM binding to this membrane protein.

Abiotic Stress Response

There is ample evidence for the involvement of Ca2+ signaling in abiotic stress responses. Changes in intracellular Ca2+ levels have been reported as an early response to diverse abiotic signals including mechanical stimuli, osmotic and salt treatments, cold and heat shocks. Noteworthy, analysis at a whole-tissue level have shown that different root cell types produce distinct Ca2+ responses to osmotic and salt stress, indicating a cellular specificity of Ca2+ patterns. Numerous data support that CaM, CML and downstream elements are important players in plant adaptation to abiotic stress. The induction of CaM and CML genes by abiotic stimuli has been described in various plant species, and genetic studies indicate positive as well as negative effects of CaM-regulated pathways on stress responses.

A well characterized pathway involved in abiotic stress response is the activation of glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) by CaM. GAD catalyzes the conversion of L-glutamate to GABA, and the enzyme is rapidly activated during stress responses. CaM and Ca2+ are required for the enzyme activity, and the use of transgenic plants expressing either CaM or a mutated form of GAD lacking the ability to bind CaM demonstrate the importance of CaM in the modulation of GABA production in plants.94 Although the role of GABA has yet to be clarified, an increase in GABA levels is a common response to various stress, and a tight control of GABA synthesis by GAD and CaM appears to be essential for plant development.

During last few years, significant advances on the role of CaMs, CMLs and target proteins during salt and osmotic stress have been reported. For instance, a transcription factor (AtMYB2) that regulates the expression of salt and dehydration-responsive genes, was recently identified as a CaM-binding protein.34 Interestingly, soybean ScaM4, a salt-inducible CaM isoform, increases the DNA binding activity of AtMYB2 whereas this activity is inhibited by soybean ScaM1. How binding of these closely related CaM isoforms to AtMYB2 differentially regulates the DNA binding activity of this transcription factor needs to be elucidated. Ectopic expression of ScaM4 in Arabidopsis enhances the transcription of AtMYB2-regulated genes including a proline-synthesizing enzyme which confers salt tolerance in transgenic plants. Conversely, proline production and salt tolerance are not significantly affected in ScaM1 transgenic plants.

Another CaM binding protein (AtCaMBP25) that is targeted to the nucleus was found to act as a negative effector of osmotic and salt stress responses.95 AtCaMBP25 belongs to a family of plant specific proteins where representative members have been reported to bind transcription factors, suggesting their involvement in gene expression. Germination and root elongation of transgenic plants overexpressing AtCaMBP25 was inhibited on osmotic and saline media, and improved for the antisense lines.95

The involvement of CMLs in salt stress and ion homeostasis is also documented. Arabidopsis CML24 is a CaM-related protein that shares 40% overall sequence identity with the conserved CaM.96 This protein undergoes conformational changes upon Ca2+ binding and likely functions in a Ca2+-influenced manner. CML24 was first identified as a touch-inducible gene, but it is also highly responsive to diverse abiotic stress and hormones. Phenotypic analysis of transgenic plants underexpressing CML24 indicate the involvement of this CaM-like protein in ABA responses, timing of transition to flowering and salt stress responses.96 The transgenic lines are less sensitive to various ions including CoCl2, ZnSO4 and MgCl2, but the specific function of CML24 in Ca2+ signaling and ion homeostasis has to be determined. Another example for a role of Ca2+ signaling in ion homeostasis is the regulation of Na+/H+ antiporters. These ion exchangers are integral membrane proteins that play a major role in Na+ and pH homeostasis. Interestingly, distinct Ca2+-dependent mechanisms are implicated in the regulation of Na+/H+ antiporters. A genetic screen for Arabidopsis mutants that are salt overly sensitive (SOS) has led to the characterization of the SOS pathway.97 This consists of a calcineurin B like Ca2+ sensor (SOS3) which interacts with and activates the protein kinase SOS2 in the presence of Ca2+. The SOS2 kinase then activates a plasmalemma-localized Na+/H+ antiporter which confers salt tolerance by removing Na+ from the cytosol More recently, the interaction between a vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter and Arabidopsis CML18 has been described.30 Surprisingly, AtCML18 is present in the vacuole and interacts in the vacuolar lumen with the C-terminal region of AtNHX1, a vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter. The interaction is Ca2+ and pH-dependent, and decreases with increasing pH values. Binding of AtCML18 to AtNHX1 modified the Na+/K+ selectivity of the antiporter, decreasing its Na+/H+ exchange activity.30 It is proposed that, at physiological conditions, the acidic pH value and the high Ca2+ concentration in the vacuole maintain AtCML18 bound to AtNHX1, thereby repressing the Na+/H+ exchange activity. Release of AtCML18 from AtNHX1 would occur as a consequence of salt stress-induced rise in vacuolar pH and increase the Na+/H+ exchange activity in favor of vacuolar Na+ accumulation.

Conclusions

Recent data reveal the diversity of CaM signaling system in plants (Fig. 2). Plants possess an extended family of CaM genes encoding closely related isoforms as well as divergent CaM like proteins, and an extremely diversified set of CaM target proteins, many of which are plant specific. Our knowledge on the physiological functions of these proteins strengthens the idea that CaM family has evolved to fulfil multiple roles in plant biology, but more functional studies are needed to better understand when, where and how CaM family recognizes and decodes Ca2+ signatures generated from various stimuli. As stimulus-response coupling is governed by the nature, localization and interconnection of signaling components present in a cell type at a particular physiological condition, further studies on protein expression, localization and interaction are essential to elucidate the complex picture of cell signaling system. Progress in proteomics and cell imaging technology, and increasing availability of genetic tools will be helpful to drive future research.

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Mazars and R. Pont-Lezica for critical reading of the manuscript as well as M. Charpenteau, F. Magnan and A. Perochon for helpful comments. Our research is supported by University Paul Sabatier (Toulouse, France) and CNRS.

Abbreviations

- CaM

calmodulin

- CML

calmodulin-like protein

- CaMBP

calmodulin binding protein

- CaMBD

calmodulin binding domain

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Plant Signaling & Behavior E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/abstract.php?id=2998

References

- 1.White PJ, Broadley MR. Calcium in plant. Ann Bot (Lond) 2003;92:487–511. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcg164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanders D, Pelloux J, Brownlee C, Harper JF. Calcium at the crossroads of signaling. Plant Cell. 2002;14:S401–S417. doi: 10.1105/tpc.002899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reddy AS. Calcium: silver bullet in signaling. Plant Sci. 2001;160:381–404. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9452(00)00386-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudd JJ, Franklin-Tong VE. Unravelling response-specificity in Ca2+ signalling pathways in plant cells. New Phytol. 2001;151:7–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2001.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snedden WA, Fromm H. Calmodulin as a versatile calcium signal transducer in plants. New Phytol. 2001;151:35–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2001.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hetherington AM, Brownlee C. The generation of Ca2+ signals in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:401–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hepler PK. Calcium: a central regulator of plant growth and development. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2142–2155. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.032508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouche N, Yellin A, Snedden WA, Fromm H. Plant-Specific Calmodulin-Binding Proteins. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2005;56:435–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAinsh MR, Hetherington AM. Encoding specificity in Ca2+ signalling systems. Trends Plant Sci. 1998;3:32–36. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen GJ, Schroeder JI. Combining genetics and cell biology to crack the code of plant cell calcium signaling. Sci STKE. 2001;2001:RE13. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.102.re13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pauly N, Knight MR, Thuleau P, Graziana A, Muto S, Ranjeva R, Mazars C. The nucleus together with the cytosol generates patterns of specific cellular calcium signatures in tobacco suspension culture cells. Cell Calcium. 2001;30:413–421. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2001.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Der Luit AH, Olivari C, Haley A, Knight MR, Trewavas AJ. Distinct calcium signaling pathways regulate calmodulin gene expression in tobacco. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:705–714. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.3.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Day IS, Reddy VS, Shad Ali G, Reddy AS. Analysis of EF-hand-containing proteins in Arabidopsis. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-10-research0056. RESEARCH0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harper JF, Breton G, Harmon A. Decoding Ca2+ signals through plant protein kinases. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:263–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang L, Lu YT. Calmodulin-binding protein kinases in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8:123–127. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00013-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luan S, Kudla J, Rodriguez-Concepcion M, Yalovsky S, Gruissem W. Calmodulins and calcineurin B-like proteins: calcium sensors for specific signal response coupling in plants. Plant Cell. 2002;14(Suppl):S389–S400. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batistic O, Kudla J. Integration and channeling of calcium signaling through the CBL calcium sensor/CIPK protein kinase network. Planta. 2004;219:915–924. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1333-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Means AR, Dedman JR. Calmodulin-an intracellular calcium receptor. Nature. 1980;285:73–77. doi: 10.1038/285073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang T, Poovaiah BW. Calcium/calmodulin-mediated signal network in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8:505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis TN, Urdea MS, Masiarz FR, Thorner J. Isolation of the yeast calmodulin gene: calmodulin is an essential protein. Cell. 1986;47:423–431. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90599-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toutenhoofd SL, Strehler EE. The calmodulin multigene family as a unique case of genetic redundancy: multiple levels of regulation to provide spatial and temporal control of calmodulin pools? Cell Calcium. 2000;28:83–96. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2000.0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehul B, Bernard D, Simonetti L, Bernard MA, Schmidt R. Identification and cloning of a new calmodulin-like protein from human epidermis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12841–12847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang M, Morasso MI. The novel murine Ca2+-binding protein, Scarf, is differentially expressed during epidermal differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47827–47833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306561200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCormack E, Braam J. Calmodulins and related potential calcium sensors of Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2003;159:585–598. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee SH, Johnson JD, Walsh MP, Van Lierop JE, Sutherland C, et al. Differential regulation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent enzymes by plant calmodulin isoforms and free Ca2+ concentration. Biochem J. 2000;350:299–306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hua W, Liang S, Lu YT. A tobacco (Nicotiana tabaccum) calmodulin-binding protein kinase, NtCBK2, is regulated differentially by calmodulin isoforms. Biochem J. 2003;376:291–302. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner WL, Waller JC, Vanderbeld B, Snedden WA. Cloning and characterization of two NAD kinases from Arabidopsis. identification of a calmodulin binding isoform. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:1243–1255. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.040428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang T, Poovaiah BW. Hydrogen peroxide homeostasis: activation of plant catalase by calcium/calmodulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4097–4102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052564899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma L, Xu X, Cui S, Sun D. The presence of a heterotrimeric G protein and its role in signal transduction of extracellular calmodulin in pollen germination and tube growth. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1351–1364. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.7.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamaguchi T, Aharon GS, Sottosanto JB, Blumwald E. Vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter cation selectivity is regulated by calmodulin from within the vacuole in a Ca2+- and pH-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16107–16112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504437102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodriguez-Concepcion M, Yalovsky S, Zik M, Fromm H, Gruissem W. The prenylation status of a novel plant calmodulin directs plasma membrane or nuclear localization of the protein. Embo J. 1999;18:1996–2007. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong A, Xin H, Yu Y, Sun C, Cao K, Shen WH. The subcellular localization of an unusual rice calmodulin isoform, OsCaM61, depends on its prenylation status. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;48:203–210. doi: 10.1023/a:1013380814919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCormack E, Tsai YC, Braam J. Handling calcium signaling: Arabidopsis CaMs and CMLs. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoo JH, Park CY, Kim JC, Heo WD, Cheong MS, Park HC, Kim MC, Moon BC, Choi MS, Kang YH, Lee JH, Kim HS, Lee SM, Yoon HW, Lim CO, Yun DJ, Lee SY, Chung W S, Cho MJ. Direct interaction of a divergent CaM isoform and the transcription factor, MYB2, enhances salt tolerance in arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3697–3706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408237200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reddy VS, Ali GS, Reddy AS. Genes encoding calmodulin-binding proteins in the Arabidopsis genome. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9840–9852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111626200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhoads AR, Friedberg F. Sequence motifs for calmodulin recognition. Faseb J. 1997;11:331–340. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.5.9141499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheney RE, Mooseker MS. Unconventional myosins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1992;4:27–35. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(92)90055-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yap KL, Kim J, Truong K, Sherman M, Yuan T, Ikura M. Calmodulin target database. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2000;1:8–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1011320027914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Radivojac P, Vucetic S, O'Connor T R, Uversky VN, Obradovic Z, Dunker AK. Calmodulin signaling: Analysis and prediction of a disorder-dependent molecular recognition. Proteins. 2006;63:398–410. doi: 10.1002/prot.20873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu H, Bilgin M, Bangham R, Hall D, Casamayor A, Bertone P, Lan N, Jansen R, Bidlingmaier S, Houfek T, Mitchell T, Miller P, Dean RA, Gerstein M, Snyder M. Global analysis of protein activities using proteome chips. Science. 2001;293:2101–2105. doi: 10.1126/science.1062191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen X, Valencia CA, Szostak JW, Dong B, Liu R. Scanning the human proteome for calmodulin-binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5969–5974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407928102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Du L, Poovaiah BW. Ca2+/calmodulin is critical for brassinosteroid biosynthesis and plant growth. Nature. 2005;437:741–745. doi: 10.1038/nature03973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klahre U, Noguchi T, Fujioka S, Takatsuto S, Yokota T, Nomura T, Yoshida S, Chua NH. The Arabidopsis DIMINUTO/DWARF1 gene encodes a protein involved in steroid synthesis. Plant Cell. 1998;10:1677–1690. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.10.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fujioka S, Yokota T. Biosynthesis and metabolism of brassinosteroids. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2003;54:137–164. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Choe S, Dilkes BP, Fujioka S, Takatsuto S, Sakurai A, Feldmann KA. The DWF4 gene of Arabidopsis encodes a cytochrome P450 that mediates multiple 22alpha-hydroxylation steps in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 1998;10:231–243. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szekeres M, Nemeth K, Koncz-Kalman Z, Mathur J, Kauschmann A, Altmann T, Redei GP, Nagy F, Schell J, Koncz C. Brassinosteroids rescue the deficiency of CYP90, a cytochrome P450, controlling cell elongation and de-etiolation in Arabidopsis. Cell. 1996;85:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hua W, Zhang L, Liang S, Jones RL, Lu YT. A tobacco calcium/calmodulin-binding protein kinase functions as a negative regulator of flowering. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31483–31494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vanoosthuyse V, Tichtinsky G, Dumas C, Gaude T, Cock JM. Interaction of calmodulin, a sorting nexin and kinase-associated protein phosphatase with the Brassica oleracea S locus receptor kinase. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:919–929. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.023846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stein JC, Howlett B, Boyes DC, Nasrallah ME, Nasrallah JB. Molecular cloning of a putative receptor protein kinase gene encoded at the self-incompatibility locus of Brassica oleracea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8816–8820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Delorme V, Giranton JL, Hatzfeld Y, Friry A, Heizmann P, Ariza MJ, Dumas C, Gaude T, Cock JM. Characterization of the S locus genes, SLG and SRK, of the Brassica S3 haplotype: identification of a membrane-localized protein encoded by the S locus receptor kinase gene. Plant J. 1995;7:429–440. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.7030429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Charpenteau M, Jaworski K, Ramirez BC, Tretyn A, Ranjeva R, Ranty B. A receptor-like kinase from Arabidopsis thaliana is a calmodulin-binding protein. Biochem J. 2004;379:841–848. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ceresa BP, Schmid SL. Regulation of signal transduction by endocytosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:204–210. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tebar F, Villalonga P, Sorkina T, Agell N, Sorkin A, Enrich C. Calmodulin regulates intracellular trafficking of epidermal growth factor receptor and the MAPK signaling pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2057–2068. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-12-0571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Golovkin M, Reddy AS. A calmodulin-binding protein from Arabidopsis has an essential role in pollen germination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10558–10563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1734110100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schiott M, Romanowsky SM, Baekgaard L, Jakobsen MK, Palmgren MG, Harper JF. A plant plasma membrane Ca2+ pump is required for normal pollen tube growth and fertilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9502–9507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401542101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taylor LP, Hepler PK. Pollen Germination and Tube Growth. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:461–491. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hepler PK, Vidali L, Cheung AY. Polarized cell growth in higher plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:159–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rato C, Monteiro D, Hepler PK, Malho R. Calmodulin activity and cAMP signalling modulate growth and apical secretion in pollen tubes. Plant J. 2004;38:887–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oldroyd GE, Harrison MJ, Udvardi M. Peace talks and trade deals. Keys to long-term harmony in legume-microbe symbioses. Plant Physiol. 2005;137:1205–1210. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.057661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roche P, Maillet F, Plazanet C, Debelle F, Ferro M, Truchet G, Prome JC, Denarie J. The common nod ABC genes of Rhizobium meliloti are host-range determinants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15305–15310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shaw SL, Long SR. Nod factor elicits two separable calcium responses in Medicago truncatula root hair cells. Plant Physiol. 2003;131:976–984. doi: 10.1104/pp.005546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wais RJ, Galera C, Oldroyd G, Catoira R, Penmetsa RV, Cook D, Gough C, Denarie J, Long SR. Genetic analysis of calcium spiking responses in nodulation mutants of Medicago truncatula. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13407–13412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230439797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oldroyd GE, Downie JA. Calcium, kinases and nodulation signalling in legumes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:566–576. doi: 10.1038/nrm1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levy J, Bres C, Geurts R, Chalhoub B, Kulikova O, Duc G, Journet EP, Ane JM, Lauber E, Bisseling T, Denarie J, Rosenberg C, Debelle F. A putative Ca2+ and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase required for bacterial and fungal symbioses. Science. 2004;303:1361–1364. doi: 10.1126/science.1093038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mitra RM, Gleason CA, Edwards A, Hadfield J, Downie JA, Oldroyd GE, Long SR. A Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase required for symbiotic nodule development: Gene identification by transcript-based cloning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4701–4705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400595101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sathyanarayanan PV, Cremo CR, Poovaiah BW. Plant chimeric Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Role of the neural visinin-like domain in regulating autophosphorylation and calmodulin affinity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30417–30422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Godfroy O, Debelle F, Timmers T, Rosenberg C. A rice calcium- and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase restores nodulation to a legume mutant. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19:495–501. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kalo P, Gleason C, Edwards A, Marsh J, Mitra RM, Hirsch S, Jakab J, Sims S, Long SR, Rogers J, Kiss GB, Downie JA, Oldroyd GE. Nodulation signaling in legumes requires NSP2, a member of the GRAS family of transcriptional regulators. Science. 2005;308:1786–1789. doi: 10.1126/science.1110951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smit P, Raedts J, Portyanko V, Debelle F, Gough C, Bisseling T, Geurts R. NSP1 of the GRAS protein family is essential for rhizobial Nod factor-induced transcription. Science. 2005;308:1789–1791. doi: 10.1126/science.1111025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fedorova M, van de Mortel J, Matsumoto PA, Cho J, Town CD, VandenBosch KA, Gantt JS, Vance CP. Genome-wide identification of nodule-specific transcripts in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:519–537. doi: 10.1104/pp.006833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Colebatch G, Desbrosses G, Ott T, Krusell L, Montanari O, Kloska S, Kopka J, Udvardi MK. Global changes in transcription orchestrate metabolic differentiation during symbiotic nitrogen fixation in Lotus japonicus. Plant J. 2004;39:487–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu J, Miller SS, Graham M, Bucciarelli B, Catalano CM, Sherrier DJ, Samac DA, Ivashuta S, Fedorova M, Matsumoto P, Gantt JS, Vance CP. Recruitment of novel calcium-binding proteins for root nodule symbiosis in Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:167–177. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.076711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Heo WD, Lee SH, Kim MC, Kim JC, Chung WS, Chun HJ, Lee KJ, Park CY, Park HC, Choi JY, Cho MJ. Involvement of specific calmodulin isoforms in salicylic acid-independent activation of plant disease resistance responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:766–771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Torres M, Sanchez P, Fernandez-Delmond I, Grant M. Expression profiling of the host response to bacterial infection: the transition from basal to induced defence responses in RPM1-mediated resistance. Plant J. 2003;33:665–676. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jakobek JL, Smith-Becker JA, Lindgren PB. A bean cDNA expressed during a hypersensitive reaction encodes a putative calcium-binding protein. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1999;12:712–719. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1999.12.8.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Durrant WE, Rowland O, Piedras P, Hammond-Kosack KE, Jones JD. cDNA-AFLP reveals a striking overlap in race-specific resistance and wound response gene expression profiles. Plant Cell. 2000;12:963–977. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.6.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mysore KS, Crasta OR, Tuori RP, Folkerts O, Swirsky PB, Martin GB. Comprehensive transcript profiling of Pto- and Prf-mediated host defense responses to infection by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. Plant J. 2002;32:299–315. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kang CH, Jung WY, Kang YH, Kim JY, Kim DG, Jeong JC, Baek DW, Jin JB, Lee JY, Kim MO, Chung WS, Mengiste T, Koiwa H, Kwak SS, Bahk JD, Lee SY, Nam JS, Yun DJ, Cho MJ. AtBAG6, a novel calmodulin-binding protein, induces programmed cell death in yeast and plants. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:84–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Takayama S, Sato T, Krajewski S, Kochel K, Irie S, Millan JA, Reed JC. Cloning and functional analysis of BAG-1: a novel Bcl-2-binding protein with anti-cell death activity. Cell. 1995;80:279–284. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90410-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kohler C, Neuhaus G. Characterisation of calmodulin binding to cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels from Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2000;471:133–136. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Arazi T, Kaplan B, Fromm H. A high-affinity calmodulin-binding site in a tobacco plasma-membrane channel protein coincides with a characteristic element of cyclic nucleotide-binding domains. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;42:591–601. doi: 10.1023/a:1006345302589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Talke IN, Blaudez D, Maathuis FJ, Sanders D. CNGCs: prime targets of plant cyclic nucleotide signalling? Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8:286–293. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Clough SJ, Fengler KA, Yu IC, Lippok B, Smith RK, Jr, Bent AF. The Arabidopsis dnd1 “defense, no death” gene encodes a mutated cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9323–9328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150005697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Balague C, Lin B, Alcon C, Flottes G, Malmstrom S, Kohler C, Neuhaus G, Pelletier G, Gaymard F, Roby D. HLM1, an essential signaling component in the hypersensitive response, is a member of the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel ion channel family. Plant Cell. 2003;15:365–379. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jurkowski GI, Smith RK, Jr, Yu IC, Ham JH, Sharma SB, Klessig DF, Fengler KA, Bent AF. Arabidopsis DND2, a second cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel gene for which mutation causes the “defense, no death” phenotype. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2004;17:511–520. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.5.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yoshioka K, Moeder W, Kang HG, Kachroo P, Masmoudi K, Berkowitz G, Klessig DF. The chimeric Arabidopsis CYCLIC NUCLEOTIDE-GATED ION CHANNEL11/12 activates multiple pathogen resistance responses. Plant Cell. 2006;18:747–763. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.038786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Arazi T, Sunkar R, Kaplan B, Fromm H. A tobacco plasma membrane calmodulin-binding transporter confers Ni2+ tolerance and Pb2+ hypersensitivity in transgenic plants. Plant J. 1999;20:171–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Arazi T, Kaplan B, Sunkar R, Fromm H. Cyclic-nucleotide- and Ca2+/calmodulin-regulated channels in plants: targets for manipulating heavy-metal tolerance, and possible physiological roles. Biochem Soc Trans. 2000;28:471–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Panstruga R. Serpentine plant MLO proteins as entry portals for powdery mildew fungi. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:389–392. doi: 10.1042/BST0330389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Buschges R, Hollricher K, Panstruga R, Simons G, Wolter M, Frijters A, van Daelen R, van der Lee T, Diergaarde P, Groenendijk J, Topsch S, Vos P, Salamini F, Schulze-Lefert P. The barley Mlo gene: a novel control element of plant pathogen resistance. Cell. 1997;88:695–705. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81912-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kim MC, Lee SH, Kim JK, Chun HJ, Choi MS, Chung WS, Moon BC, Kang CH, Park CY, Yoo JH, Kang YH, Koo SC, Koo YD, Jung JC, Kim ST, Schulze-Lefert P, Lee SY, Cho MJ. Mlo, a modulator of plant defense and cell death, is a novel calmodulin-binding protein. Isolation and characterization of a rice Mlo homologue. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19304–19314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108478200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kim MC, Panstruga R, Elliott C, Muller J, Devoto A, Yoon HW, Park HC, Cho MJ, Schulze-Lefert P. Calmodulin interacts with MLO protein to regulate defence against mildew in barley. Nature. 2002;416:447–451. doi: 10.1038/416447a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bhat RA, Miklis M, Schmelzer E, Schulze-Lefert P, Panstruga R. Recruitment and interaction dynamics of plant penetration resistance components in a plasma membrane microdomain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3135–3140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500012102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bouche N, Fromm H. GABA in plants: just a metabolite? Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Perruc E, Charpenteau M, Ramirez BC, Jauneau A, Galaud JP, Ranjeva R, Ranty B. A novel calmodulin-binding protein functions as a negative regulator of osmotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Plant J. 2004;38:410–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Delk NA, Johnson KA, Chowdhury NI, Braam J. CML24, Regulated in Expression by Diverse Stimuli, Encodes a Potential Ca2+ Sensor That Functions in Responses to Abscisic Acid, Daylength, and Ion Stress. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:240–253. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.062612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhu JK. Regulation of ion homeostasis under salt stress. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2003;6:441–445. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(03)00085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mura A, Medda R, Longu S, Floris G, Rinaldi AC, Padiglia A. A Ca2+/calmodulin-binding peroxidase from Euphorbia latex: novel aspects of calcium-hydrogen peroxide cross-talk in the regulation of plant defenses. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14120–14130. doi: 10.1021/bi0513251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Moon BC, Choi MS, Kang YH, Kim MC, Cheong MS, et al. Arabidopsis ubiquitin-specific protease 6 (AtUBP6) interacts with calmodulin. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3885–3890. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.05.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Park CY, Lee JH, Yoo JH, Moon BC, Choi MS, Kang YH, Lee SM, Kim HS, Kang KY, Chung WS, Lim CO, Cho MJ. WRKY group IId transcription factors interact with calmodulin. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1545–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Delaney K, Xu R, Li QQ, Yun KY, Falcone DL, Hunt AG. Calmodulin interacts with and regulates the RNA-binding activity of an Arabidopsis polyadenylation factor subunit. Plant Physiol. 2006;40:1507–1521. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.070672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Levy M, Wang Q, Kaspi R, Parrella MP, Abel S. Arabidopsis IQD1, a novel calmodulin-binding nuclear protein, stimulates glucosinolate accumulation and plant defense. Plant J. 2005;43:79–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA3: Integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform. 2004;5:150–163. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]