Abstract

Motivation: As the use of microarrays in human studies continues to increase, stringent quality assurance is necessary to ensure accurate experimental interpretation. We present a formal approach for microarray quality assessment that is based on dimension reduction of established measures of signal and noise components of expression followed by parametric multivariate outlier testing.

Results: We applied our approach to several data resources. First, as a negative control, we found that the Affymetrix and Illumina contributions to MAQC data were free from outliers at a nominal outlier flagging rate of α=0.01. Second, we created a tunable framework for artificially corrupting intensity data from the Affymetrix Latin Square spike-in experiment to allow investigation of sensitivity and specificity of quality assurance (QA) criteria. Third, we applied the procedure to 507 Affymetrix microarray GeneChips processed with RNA from human peripheral blood samples. We show that exclusion of arrays by this approach substantially increases inferential power, or the ability to detect differential expression, in large clinical studies.

Availability: http://bioconductor.org/packages/2.3/bioc/html/arrayMvout.html and http://bioconductor.org/packages/2.3/bioc/html/affyContam.html affyContam (credentials: readonly/readonly)

Contact: aasare@immunetolerance.org; stvjc@channing.harvard.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

Recent successes with microarrays for the identification of gene patterns that correlate with disease states has resulted in their increased use in human studies. As this approach moves from smaller scale efforts into biomarker discovery efforts in clinical trials, rapid and reliable quality assurance approaches are necessary, both from the perspective of ensuring accurate data for inclusion as clinical trial secondary endpoints, and as a measure to contain costs (Group, 2004). As a large clinical trial consortium, we have processed over 1500 Affymetrix Gene Chips® fromeight different clinical trials, with these numbers growing yearly. Thus, we required a streamlined and accurate method for defining which arrays are of high quality and to determine the overall success rate of arrays processed in our central laboratory.

Many of the currently used microarray quality assessments are manufacturer-based recommendations that rely on a limited number of parameters with imprecise specifications for acceptable results. In this report, we review definitions of quality assessment criteria for Affymetrix and Illumina expression arrays, and describe algorithms for formally identifying aberrant arrays with a specified false positive rate. Our procedure involves parametric multivariate outlier testing using a multivariate Gaussian model, which we apply to principal components of the quality measure matrix.

2 METHODS

2.1 Definitions of quality metrics

For Affymetrix Gene Chips®, quality criteria include the actin (HSACO7) and GAPDH 3′/5′ ratios, the percent present calls according to the MAS5 algorithm, the array-specific scale factor and average background [see Hubbell et al. (2002) and the Affymetrix Statistical Algorithm Reference Guide]. The actin and GAPDH ratios indirectly reflect the efficiency of reverse transcription of the total RNA template, as high 3′ to 5′ ratios indicate poor transcription from the 3′-end, resulting in small fragments of cDNA/cRNA available for hybridization. The other indicators reflect hybridization efficiency as they indicatethe number of probes hybridized from the total (percent present call) and the amount of background noise.

Bolstad et al. (2003) define probe-level modeling (PLM) for Affymetrix arrays as a flexible generalization of the established robust multiarray preprocessing procedure (RMA) due to Irizarry et al. (2003). PLM computes two quantities of particular interest for quality assessment. The first, relative log expression (RLE), examines point estimates of expression values at the probe set level. Suppose, here and in the sequel, that there are N arrays and G probe sets. PLM computes êij, i=1,…, G, j=1,…, N, on the basis of a robust regression model allowing general probe and sample effects. The quantity  is the median log expression of the i-th probe set.

is the median log expression of the i-th probe set.  computed for all probes, all arrays. Denote by RLE·j the G-vector of RLE measures for the j-th array. Features of the distribution of RLE·j are informative on array quality: medians should be close to zero for all arrays, and variances should be similar across arrays. Departures from these conditions are usually associated with quality defects. Another quantity derived from PLM is the normalized unscaled standard error (NUSE). Here, the focus is on variability of estimation of expression. PLM computes standard errors of all expression measures, and these are standardized, gene by gene, across arrays, so that the median standard error across arrays is 1. The G-vector of NUSE for each array should have median 1 and common variance across arrays.

computed for all probes, all arrays. Denote by RLE·j the G-vector of RLE measures for the j-th array. Features of the distribution of RLE·j are informative on array quality: medians should be close to zero for all arrays, and variances should be similar across arrays. Departures from these conditions are usually associated with quality defects. Another quantity derived from PLM is the normalized unscaled standard error (NUSE). Here, the focus is on variability of estimation of expression. PLM computes standard errors of all expression measures, and these are standardized, gene by gene, across arrays, so that the median standard error across arrays is 1. The G-vector of NUSE for each array should have median 1 and common variance across arrays.

Another indicator provided by the affy package of Bioconductor/R (Gautier et al., 2004) is the RNA degradation slope, which assesses the 3′/5′ ratio for all genes on the array. Probes are ordered within probe sets from 5′- to 3′-most and the intensity gradient along this sequence is qualitatively estimated pointwise for each array. Arrays with quality problems can possess aberrant gradients, typically assessed visually.

For Illumina arrays, the Bioconductor lumi package (Du et al., 2008) includes the lumiQ function which computes a four-dimensional quality feature vector for each array in a lumiBatch. The quality measures are average intensity and intensity SD, average detection rate as reported by the BeadStudio preprocessor and average Euclidean distance of probe-specific intensities to their means over all samples.

2.2 Array quality feature-vector and dimension reduction

For Affymetrix arrays, the metrics described above lead to nine quantitative measures of array quality computed on each array: ABG (average background), SF (scale factor), PP (percent present), AR (actin 3′/5′ ratio), GR (GAPDH 3′/5′ ratio), median NUSE, median RLE, RLE-IQR (interquartile range of IQR per array, to measure variability in RLE) and RNAS (slope of RNA degradation measure). This sequence of numbers is regarded as the array-specific quality feature vector. A principal components transformation is conducted using R function prcomp to obtain linear combinations of the original features that are mutually orthogonal and that capture substantial fractions of variation among samples. The use of linear combinations also aids in procuring a multivariate representation of the quality information that may, under a null hypothesis of equivalent quality, be reasonably approximated by a multivariate Gaussian probability model. We denote by Q the N×9 feature matrix (with arrays defining rows and quality measures defining qualities). The matrix consisting of the user-selected m>1 initial principal components of Q as columns is denoted as P.

For Illumina arrays, we denote by Q the N×4 feature matrix of lumi-based quality measures, to which principal components transformations may be applied.

2.3 Multivariate outlier detection algorithms

If there are r>N/2 non-outlying rows of the N×m matrix, P are regarded as a collection of r samples from the m-dimensional Gaussian model Nm(μ, Σ) with m-dimensional mean μ and m×m covariance matrix Σ, an algorithm of Caroni and Prescott (1992) can be used to identify outlying observations among the N data rows with a fixed small probability of incorrectly labeling a non-outlying observation as an outlier.

Let S denote the m×m sample covariance matrix of the m first principal components of Q [taking the m columns of P as variables and the N rows of P as observations (denoted Pi, i=1,…,N)]. Wilks' scatter ratios are the quantities

where S(l) denotes the sample covariance matrix of P computed with row l removed. Wilks' scatter ratio is the likelihood ratio test statistic of

against

where the outlier index j, the m-dimensional ‘slippage parameter’ aj and the variance parameter Σ are all unknown. The scatter ratio may be re-expressed as a function of the Mahalanobis distance:

Caroni and Prescott implement an inward peeling followed by outward testing procedure following a univariate procedure due to Rosner (1983). Define D1=minj(Wj), and D2,…, DN−r as the sequence of scatter ratios formed from successive eliminations of rows of P posessing the smallest scatter ratios at each stage. Caroni and Prescott observe that the distribution of Wj for given j is Beta([n−p−1]/2, p/2) and derive Bonferroni bounds using Rosner's arguments to obtain approximations to the distributions of Ds, s=1,…, N−r. Critical values are obtained using these approximations and thequantities DN−r,…, D1 are each tested at level α. If DN−q is smaller than the associated critical value, then the associated sample and all samples associated with minimal scatter ratios computed at stages earlier than N−q are declared outlying. This procedure mislabels non-outlying samples as outliers with overall error rate α whether or not any outliers are actually present in P, and is implemented in R source code in the arrayMvout package. In tables below, we refer to the results of using this procedure as PMVO (for Parametric MultiVariate Outlier labeling).

An important recent contribution to array outlier assessment is the methodology of Cohen Freue et al. (2007) in which robust Mahalanobis distances are used to identify aberrant arrays. The standard Mahalanobis distance can be robustified by substituting for the sample covariance a covariance estimator based on the minimum covariance determinant, minimum volume ellipsoid or a specific S-estimator. Parametric or simulation-based critical values for outlier labeling are available. In comparative tabulations below this algorithm is denoted MDQC.

2.4 Implementation

The arrayMvout package includes a function ArrayOutliers that accepts an AffyBatch (imported intensity data structure derived from CEL files) or lumiBatch instance, specification of α and a vector indicating which principal components are to be used to define P. ArrayOutliers returns an instance of the arrOutStruct class, for which a simple reporting method is defined, showing the indices and feature values of outlying arrays; a plot method returns the principal components biplot of Q. The object quietly maintains results of all quality metric computations, such as the fitPLM result, facilitating more detailed diagnosis should such be required.

2.5 Power estimation

PowerAtlas, a power and sample size estimation tool for microarray study, was adopted to investigate impact of aberrant arrays on statistical power for identification of differentially expressed genes (Page et al., 2006). The PowerAtlas tool is developed based on a mixture model approach for estimation of power and sample size of high-dimensional data (Gadbury et al., 2004). A list of per-gene P-values, generated from a pair-wise comparison using LIMMA package, was used as input for PowerAtlas for power estimation of the comparison.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Negative control: application to MAQC arrays

The Affymetrix contribution to the MAQC expression study consists of 120 Affymetrix hgu133plus2 arrays collected from three MAQC labs with two replicates on each of four sample types. These arrays were produced under a strict protocol for the MAQC cross-platform comparison (Shi et al., 2006) and so are expected to be of very high quality. Our outlier algorithm was applied with m=3 and α=0.01, 0.05 and 0.10 with two approaches to feature representation. As requested by two referees, we applied outlier detection to the raw quality features without principal components re-expression. The table entry under PMVO-raw shows that relatively large numbers of outliers are flagged with this approach. When principal components re-expression is applied, no outliers are detected with PMVO at α=0.01, 0.05or 0.10.

We obtained the raw MAQC data contributions from Illumina, Inc. (Le. Shi, personal communication), and created raw reads of 19 arrays using the lumiR procedure of the lumi package of Bioconductor (Du et al., 2008), and then computed the quality measures via the lumiQ procedure. Table 1 shows that PMVO finds no outliers, while MDQC finds a small number as long as α≥0.05. We conclude that PMVO has reasonable specificity when used in conjunction with principal components re-expression for arrays produced in good quality conditions.

Table 1.

Application of multivariate outlier detection to negative and positive controls derived from MAQC and Affymetrix spike-in series, the latter with digital contamination

| Negative controls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | No. of chips | No. of chips flagged |

||

| PMVO-raw | PVMO-PC | MDQC-PC | ||

| Affy. MAQC | 120 | (34,34,23) | (0,0,0) | (9,3,1) |

| Illu. MAQC | 19 | (0,0,0) | (0,0,0) | (3,1,0) |

| Digitally contaminated arrays | ||||

| Source | No. of chips | Contaminated | Chips flagged |

|

| PMVO-PC | MDQC | |||

| Affy. spike-in | 12 | – | none | 2,8,10 |

| 1 | 1 | 1,8 | ||

| 1,2 | 1,2,8 | 1,2 | ||

| 1,2,11 | 1,2,8,11 | 8,10 | ||

For negative controls, table cells give number of arrays flagged at α=0.10, 0.05, 0.01.

For positive controls, cell entries give indices of arrays contaminated or identified by various algorithms. Method labels are: PMVO-raw, for parametric multivariate outlier detection applied to raw QA features; PMVO-PC, for PMVO applied with dimension reduction to first three principal components; MDQC, for Mahalanobis distance-based algorithm of Cohen Freue et al. (2007) with the MCD estimator of covariance, applied to raw QC features; and MDQC-PC, for MDQC with the S-estimator of covariance applied on PC1–PC3 of QC features.

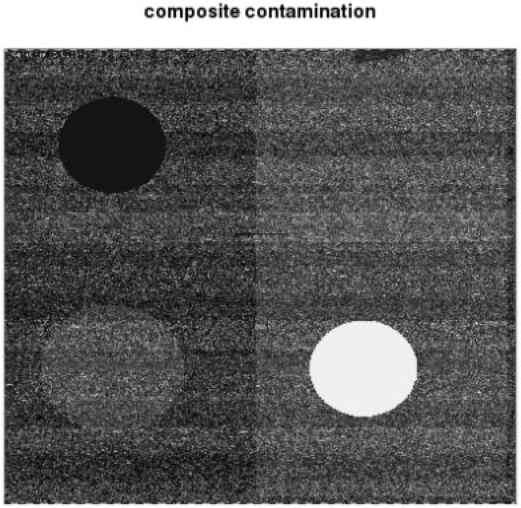

3.2 Sensitivity to specific contamination events

Figure 1 displays a digitally contaminated CEL file from the Affymetrix spike-in experiment archive. The readily visible artifacts are created by altering intensity levels in specific regions of the chip either by fixing them to constant value or by rescaling them to achieve altered intensity variance. For conciseness, the figure shows a chip on which four contamination events occur simultaneously; in our data analyses these were applied separately to different subseries of chips as shown in Table 1. The base series is the first 12 chips in the U133A spike-in subset. Each of four types of artifact were introduced to chip 1, then chips 1 and 2, and then chips 1, 2 and 11, to understand the effects of artifact type and number on sensitivity of outlier detection algorithms. We see that when there are no artifacts, PMVO does not declare any array to be outlying, but MDQC (run with default settings) declares three arrays to be outliers. Results for PMVO and MDQC were invariant to the type of artifact when only 1 or 2 chips were contaminated, so contamination type is not recorded in Table 1. When three chips were contaminated (1, 2 and 11), PMVO always flagged chips 1, 2, 8 and 11, regardless of the type of contamination. MDQC was sensitive to type; in the table we show that it flagged chips 8 and 10, as was true for low constant and increased variability blobs; with the high constant blob MDQC flagged 10 and 11, and for rectangle of increased variability, MDQC flagged 1 and 8. Further study of differential sensitivity to artifact type will be warranted.

Fig. 1.

Composite of four types of digital contamination applied to raw Affymetrix intensity data—the three circular subregions are, counterclockwise from upper left, low constant, variable and high constant blobs, and the rectangular region on the right has inflated variance.

3.3 Large-scale applications

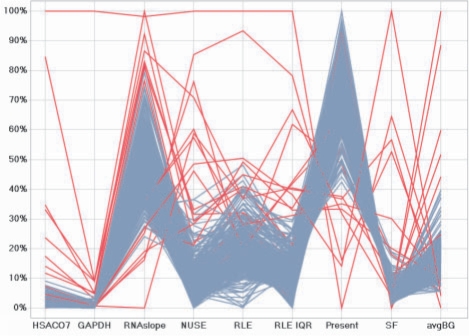

We applied this method to identify aberrant arrays from a pool of 507 microarrays from multiple clinical studies conducted by the Immune Tolerance Network (ITN). This dataset was generated from clinical human studies using peripheral blood samples, representing a very different experimental setting from the MAQC study. There is higher variability and little to no ability to perform technical replicates due to cost and sample limitations. In the human peripheral blood RNA microarray sample set, 18 microarrays, or 3.5%, were detected as outliers at α=0.01 (Fig. 2). We confirmed this approach to outlier detection by plotting the distribution of arrays by individual QA indicator (Fig. 1) with the outlier arrays highlighted in red. As shown, blue traces correspond to arrays of high quality that fall within acceptable QA ranges as previously described (GeneChip Expression Analysis Technical Manual, www.affymetrix.com). Arrays that the approach flagged as outliers (Fig. 2) do not fall within the acceptable range for at least one if not more of the QA parameters.

Fig. 2.

Parallel coordinate plots are a common way of visualizing multi-variate data with different scales to facilitate detection of outliers. Applying our QA approach, 18 of the 507 microarrays were flagged as aberrant (highlighted in red). As shown, our approach to QA has selected samples as problematic where one or more indicators appear as an outlier based on reduction of the dimensionality of the data via PCA and applying a sequential Wilks's multivariate outlier test at an α=0.01. Our approach provides greater consistency in designating problematic arrays through a statistical framework that does not rely on arbitrary cutoffs for any individual indicator.

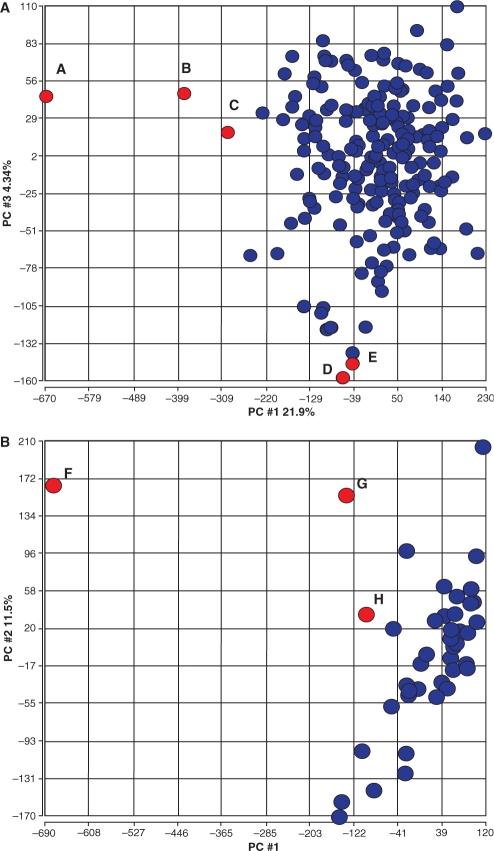

To demonstrate that our outlier detection method improves the ability to determine meaningful changes in gene expression (differential gene expression), we assessed the impact of our outliers on gene expression estimates (absolute measures that are averaged across all probes for a particular gene). Our assessment focused on two trials where we expected differential expression based on clinical phenotype or treatment regimen. In the first case, we used a set of 204 arrays from a ragweed allergy clinical trial. Our method identified five outliers (Fig. 3A, shown in red and designated as A–E) that are coincident with five points outside the major grouping of samples on plots of PCA gene expression estimates. For outliers ABC, this was due to poor (high) NUSE values, with only array A having poor (low) percent present calls. Outliers D and E had normal percent present calls and NUSE values, but poor GAPDH , actin (HSACO7) and RNA slope values.

Fig. 3.

PCA was applied to gene expression estimates for all genes in two clinical trials. (A) The outlier detection approach described was applied to 204 arrays from a ragweed allergy study and identified five samples. These microarrays are highlighted in red in the PCA 1 versus PCA 3 plot for gene expression to show the relationship of outlier samples detected by the system to actual gene expression estimates per array. Points A, B and C have problematic NUSE values. Points D and E have abnormally high GAPDH and HSAC07 ratios. The location of these arrays based on gene expression PCA suggests that QA problems may contribute to deterioration of overall expression. (B) A kidney transplant trial with 42 arrays where three were detected as outliers. The three arrays are highlighted in red in the PCA 1 versus PCA 2 gene expression plot. Points F, G and H have abnormal NUSE, GAPDH and HSAC07 ratios. Again, the samples flagged by the QA approach appear to have gene expression estimates that differ from the majority of other arrays. The arrayMvout package includes a map fig3map from records in the ITN QA metrics matrix to samples labeled A–H in these figures.

Our second case study used a set of 42 microarrays from a kidney transplant trial, in which three patient cohorts were compared. Here, we detected three outliers using our method. These outliers also correspond to arrays which fall outside the primary cluster on PCA gene expression estimate plots (Fig. 3B Points F–H). In this case, all three points falling out of the cluster had poor GAPDH, actin (HSACO7) ratio, RNA slope, and NUSE values. Array F had a poor percent present call, while G and H did not. While the outlier arrays detected by our method correspond to arrays that are outside the cluster of gene expression estimate PCA plots, our approach provides improved discriminatory power in that it permits discrimination of arrays that are outliers due to poor array quality compared with those that are likely to reflect actual biological variance.

3.4 Improvement of statistical power

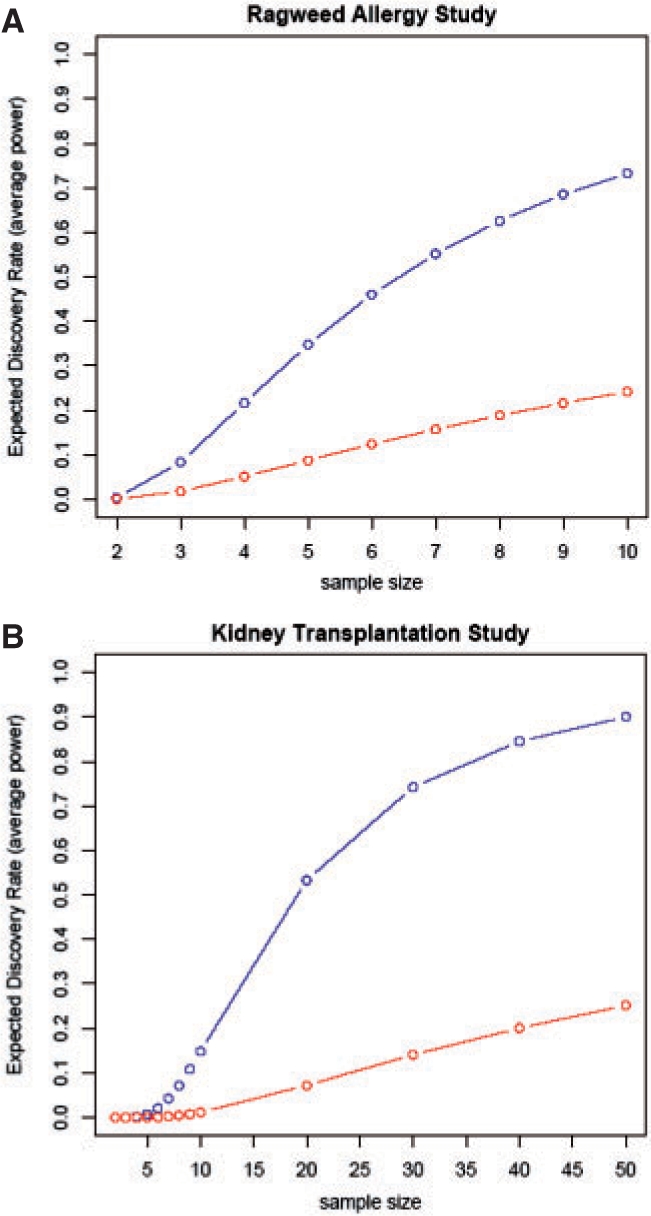

The benefit of excluding poor quality arrays in differential expression analyses was further demonstrated through statistical power calculations for these two clinical trials.Statistical power is a major limiting factor in clinical microarray studies due to limited sample size and lack of technical replicates.

Power calculations were performed, using PowerAtlas (Gadbury et al., 2004), both with and without the two array outliers (Fig. 3A, Points B and C) identified by our method. These two microarrays correspond to data points that were collected to assess treatment effect. The other three outliers in Fig. 3A addressed seasonal effects of the study. Gadbury's procedure fits a two-component mixture of Beta variates to the distribution of P-values of gene-specific differential expression tests. The two components of the Beta model for P-values correspond to (i) the distribution of P for non-differentially expressed genes (which will be uniform), and (ii) the distribution of P for differentially expressed genes (which will have mass predominantly near zero). Parametric bootstrapping is then used in conjunction with the mixture model fit to relate the sample size of an experiment to the operating characteristics of tests for differential expression. Gadbury defines the expected discovery rate (EDR) as the expected proportion of genes that are truly differentially expressed that will be declared to be differentially expressed under a given design. If differential expression is present, but tests of differential expression are impaired by the presence of poor quality arrays, the P-values obtained will not be readily resolved into two components, and power will be diminished. With the arrays of low quality included, Gadbury's estimate of the EDR [with false discovery rate (FDR)=0.05] was 24.2% at a sample size of 10, whereas the EDR improved to 73.3% for the same sample size, same FDR, through exclusion of the poor quality arrays (Fig. 4A). Similarly, in our kidney transplantation case study, we compared two of the three cohorts; each of these two cohorts had one outlier (Fig. 3B, Points F and G). Power calculations with outlier arrays both included and excluded showed that the EDR reached 14.1% and 74.2%, respectively for a sample size of 30 (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Statistical power calculations. (A) Ragweed allergy study showing improved EDR upon removal of arrays flagged as Points B and C in Figure 3A comparing two time points of interest. (B) Kidney transplant study showing removal of two arrays flagged as F and G in Figure 3B in a differential expression comparison of two treatment cohorts.

4 CONCLUSION

While microarray post-hybridization quality indicators are readily generated via standard output from analysis software packages, cutoffs used to identify problematic arrays have typically been subjective and arbitrary in nature. These indicators, by themselves, do not always give the level of discrimination needed to distinguish microarrays that are poor in quality.

We have proposed a three-step procedure for decision-making about array quality.

First, choose a collection of quantitative quality metrics. For Affymetrix expression arrays, we have identified nine metrics that appear to have reasonable utility, and for Illumina expression arrays we use four metrics that are routinely computed by open source software. These metrics can be supplemented or restricted as desired by users.

Second, compute the principal components re-expression of the metrics and reduce the quality data to a modest number of components. This step pursues parsimonious integration of the various metrics and yields a multivariate quality representation that should be reasonably approximated by the multivariate Gaussian model.

Third, apply calibrated parametric multivariate outlier detection to a subset of the resulting quality principal components. We propose Caroni and Prescott's generalization of Rosner's GESD procedure, show that it has reasonable specificity and sensitivity in several contexts, and indicate that its use leads to increased inferential power in an important clinical application.

Despite the attractive features identified above, prospective users of statistical outlier labeling in microarray contexts need to be cautious in their application of these methods. It is a commonplace that the outliers are often the most interesting records in any given database. Because we are studying outlyingness with respect to average quality, the outlying arrays may be informative about important events or discrepancies in the overall processing workflow. It is also inevitable that the procedure described here has several components conferring flexibility, and, consequently, manipulability. There is no basis at present for objective choice of base quality metrics, for the choice of number of principal components to use in reduction, or for the choice of null outlier labeling rate α that will lead to greatest confidence that arrays labeled as outliers are truly aberrant and that unlabeled arrays are of adequate quality. Thus, it is possible that two users may obtain different decisions on identical data. We have designed the ArrayOutliers tools so that they are reasonably self-documenting, so that all applications canbe audited.

There are various avenues along which the work described here should be extended. First, by working with larger numbers of arrays that have been independently classified into ‘acceptable’ and ‘unacceptable’ states, it should be possible to analyze the contributions of different quality metrics to probabilities of class membership. Second, when large numbers of arrays that are known to be of good quality are available, the outlier detection process can be supplemented by a ‘reference’ database. Specifically, parametric outlier testing can be conducted on the basis of a fixed null mean and covariance for quality features derived from a family of arrays known to be of high quality. The arrayMvout package includes matrices of quality measures for the Affymetrix and Illumina MAQC contributions, which can support exploration of this reference-based testing concept.

Funding

Subcontract from the Immune Tolerance Network; a project of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; The National Institute for Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation. National Institute of Health (P41 HG004059-01 to V.J.C.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the constructive comments of referees and an associate editor.

REFERENCES

- Bolstad BM, et al. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroni C, Prescott P. Sequential application of wilks' multivariate outlier test. Appl. Stat. 1992;41:355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Freue GV, et al. Mdqc: a new quality assessment method for microarrays based on quality control reports. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:3162–3169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du P, et al. lumi: a pipeline for processing illumina microarray. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1547–1548. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadbury G, et al. Power and sample size estimation in high dimensional biology. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2004;13:325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Gautier L, et al. affy–analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip Data at the probe level. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:307–315. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group T.A.BP. Expression profiling–best practices for data generation and interpretation in clinical trials. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:229–237. doi: 10.1038/nrg1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbell E, et al. Robust estimators for expression analysis. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1585–1592. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.12.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, et al. Summaries of affymetrix genechip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page GP, et al. The poweratlas: a power and sample size atlas for microarray experimental design and research. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:84. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner B. Percentage points for a generalized ESD many-outlier procedure. Technometrics. 1983;25:165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, et al. The Microarray Quality Control (MAQC) project shows inter- and intraplatform reproducibility of gene expression measurements. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1151–1161. doi: 10.1038/nbt1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]