Abstract

Summary: Cross-mapping of gene and protein identifiers between different databases is a tedious and time-consuming task. To overcome this, we developed CRONOS, a cross-reference server that contains entries from five mammalian organisms presented by major gene and protein information resources. Sequence similarity analysis of the mapped entries shows that the cross-references are highly accurate. In total, up to 18 different identifier types can be used for identification of cross-references. The quality of the mapping could be improved substantially by exclusion of ambiguous gene and protein names which were manually validated. Organism-specific lists of ambiguous terms, which are valuable for a variety of bioinformatics applications like text mining are available for download.

Availability: CRONOS is freely available to non-commercial users at http://mips.gsf.de/genre/proj/cronos/index.html, web services are available at http://mips.gsf.de/CronosWSService/CronosWS?wsdl.

Contact: brigitte.waegele@helmholtz-muenchen.de

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online. The online Supplementary Material contains all figures and tables referenced by this article.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the past, gene names and protein names were assigned by scientists working on their favourite molecules. As result of the uncontrolled nomenclature, different protein names are used for identical molecules and, vice versa, one name is linked to different molecules. The same is true for gene names like IGEL which is now a synonym for PHF11 and MS4A2. When the problem became pressing, organizations like the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (Povey et al., 2001) took the responsibility to standardize at least gene names. However, protein names are still differently assigned between databases like UniProt (The UniProt Consortium, 2008) and RefSeq (Pruitt et al., 2007). Also, for the application of unique molecule identifiers, each database has its own peculiarities limiting the compatibility of the different resources. An additional level of complication is introduced by the instability of identifiers, which are changed, for example, as a result of improved gene models.

These inconveniences have considerable implications on subsequent bioinformatics applications. Ambiguous molecule nomenclature affects, for example, analysis of protein networks using text mining by introducing erroneous protein–protein interactions. Other applications which require the incorporation of heterogeneous datasets are hampered by arbitrary identifiers from different databases. The inevitable conversion of identifiers between databases is a time consuming and painful task.

In the past different approaches like calculating sequence identity or molecule names were used to cross-reference identifiers.

Tools like MatchMiner (Bussey et al., 2003) which are based on gene and protein names are affected by the above mentioned problem of misleading nomenclature. On the other hand, the advantage of the sequence similarity approach is the independence of misleading nomenclature. However, the hit with the highest similarity is not necessarily the same gene and thus a threshold of 100% sequence identity used in PICR (Cote et al., 2007) does not detect all correct mappings. This is due to the fact that in different databases gene models and derived protein sequences sometimes are not consistent, especially at the N-terminus (e.g. IARS gene product).

Here, we present CRONOS, a versatile tool for mapping of identifiers, gene names and protein names from various resources like UniProt, RefSeq and Ensembl (Flicek et al., 2008). Validity of the results is ensured by elimination of ambiguous gene names and the presentation of results from sequence similarity calculations. Manual inspection of potentially error-prone terms resulted in organism-dependant lists of ambiguous gene and protein names which are not only required for accurate mapping of identifiers but also for bioinformatics applications like text mining.

2 METHODS

2.1 Generation of cross-references

Building of the cross-references is performed with data from five mammalian organisms (human, mouse, rat, cow and dog) using UniProt, RefSeq and Ensembl as primary resources. Human, mouse and rat are the most thoroughly investigated organisms according to PubMed entries. Data from dog and cow could easily be integrated. The relation between two gene products, which is the basis of the mapping, is defined as a connection between two entries that share at least one gene name or protein name. Relations are calculated in consecutive steps until two entries share identical attributes: (i) Two entries have one gene name or synonym in common. (ii) Two entries have one gene or protein name in common. This step is necessary, since some databases use gene names as protein names and vice versa. (iii) Two entries share at least one protein name/synonym.

This procedure is first performed with data from RefSeq and UniProt. If several relations can be formed for a RefSeq entry, Swiss-Prot entries are preferred to TrEMBL entries. Second, relations between RefSeq and Ensembl entries are calculated. If a relation between RefSeq and Ensembl cannot be established but there is a relation between Ensembl and UniProt, Ensembl is linked to RefSeq via UniProt.

The next step is the calculation of transitive relations for the formerly defined relations. The aim is the creation of unique ID-triplets, containing corresponding identifiers from all three resources, whenever possible. Those are directly imported to CRONOS. The fourth step includes the integration of all entries that have not been imported yet. This step covers import of entries occurring only in one of the above relations and import of remaining entries without any relation to other entries.

In the end, CRONOS entries are assigned to complete non-redundant lists of all gene and protein names. The contents of CRONOS will be updated annually.

UniProt, RefSeq and Ensembl provide cross-references to various other resources providing information about metabolic pathways, functional annotation or protein domain information. This additional information allows to search with up to 18 different identifiers (Supplementary Material S1) for cross-references depending on the organism. Thus, CRONOS functions as distribution center for all requests to convert ID-Types.

2.2 Generation of lists with ambiguous gene names and protein names

In order to detect gene and protein names which are assigned to products of different genes and thus result in erroneous cross-references, dedicated lists are created for each organism separately. Organism-specific lists are necessary, since terms that are ambiguous in one organism might be explicit in another. For example, ADORA2 is an ambiguous gene name in Homo sapiens but not in mouse, and GALT in mouse but not in H.sapiens.

In a first step, ambiguous names within the databases were extracted. If a name occurs in at least two entries describing different genes or proteins (splice variants count as one gene/protein), this particular name is marked as ambiguous and is excluded from the mapping process. In a second step, corresponding gene names occurring in the manually annotated sections of RefSeq as well as in UniProt were analyzed. Entries containing the same gene product name and having a one-to-many or many-to-many relation (e.g. one Swiss-Prot entry maps to many RefSeq entries) were scrutinized for misleading annotation. This process is done manually by inspecting additional information like sequence similarity or functional information about the involved entries. In most of the cases, the exclusion of the ambiguous gene names resulted in correct one-to-one relations.

As statistical analysis revealed (Supplementary Material S2) that gene names with less than four letters are exceptionally error-prone, only gene names with at least four letters are kept for mapping purposes. However, gene names with less than four letters can be queried, e.g. a search for the tumor suppressor ‘p53’ reveals the respective entries with the official gene name ‘TP53’. Organism-specific lists of ambiguous gene and protein names are available for download on the CRONOS home page.

2.3 Validation of the mapping

To provide a measure for the reliability of the mapping procedure, entry pairs from UniProt and translated coding sequences from RefSeq are aligned. The alignment is performed with JAligner (http://jaligner.sourceforge.net). The percent identity is calculated as number of matches divided by the length of the longer sequence. Since sequence similarity tends to be very low if TrEMBL entries are referenced to RefSeq, the underlying alignment can be displayed.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Here, we present a fast and accurate resource for mapping of cross-references from major databases. Currently, CRONOS contains entries from five mammalian organisms. Model organisms like Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Drosophila melanogaster will follow soon. With UniProt, RefSeq and Ensembl, we include data from three of the most frequently used data resources for gene and protein sequences. If a search for cross-references reveals several results, the primary results are listed together with protein sequence identity (see Section 2) and all gene and protein names.

More than 17 500 (90%) of human Swiss-Prot entries were mapped to 24 000 (95%) corresponding reviewed RefSeq entries. The higher number of RefSeq entries is due to the fact that RefSeq represents splice variants of genes as individual entries, whereas UniProt usually provides one representative entry including all products of a gene.

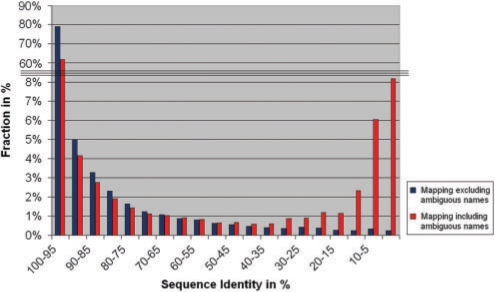

In order to validate the mapping, the identity between protein sequences from different databases is calculated using JAligner and displayed in the primary and the final results pages. The alignment can be visualized via hyperlink. Examination of the complete dataset for H.sapiens revealed the high quality of the mapping. For ∼85% of all Swiss-Prot-RefSeq protein pairs, the sequence identity is higher than 90% (see Figure 1 and Supplementary Material S3).

Fig. 1.

Quality of the mapping with and without ambiguous gene names and protein names. The sequence identity of the mapped entries from human (Swiss-Prot and RefSeq) was calculated and pooled in fractions of 0–5%, 5–10% sequence identity etc. The plot shows the fraction of the mapped entries plotted against the sequence identity of these entries.

Since 20% of bona fide mappings are in the range between 95% and 99% sequence identity, CRONOS reveals more comprehensive results compared with tools which are restricted to 100% identity.

There are two kinds of gene names not suitable for mapping. Gene names with less than four characters are considerably error-prone, e.g. up to 20% of all gene names with less than four letters from databases were shown to be ambiguous (Supplementary Material S2). Another source of errors are gene names which were historically assigned to different genes, e.g. MDR1, which was used for an ABC transporter (now ABCB1) and a TBC1 domain family gene (TBC1D9). The consequences of such multiple assignments are erroneous mapping results. To avoid mapping errors, we created lists with ambiguous gene names. These lists were manually revised and contain approximately 1900 terms for H.sapiens. Analysis of 18.1 Mio PubMed abstracts showed that ambiguous gene names appear 1.25 Mio times in abstracts.

These lists are invaluable for bioinformatics applications like text mining. Generation of protein–protein interaction networks using gene names leads to a considerable number of false positive interactions if ambiguous gene names are not removed.

Mapping of gene names and protein names is conceptually the core of CRONOS. UniProt, RefSeq and Ensembl provide links to a variety of other resources which allows to include additional identifiers for mapping. Thus, the user might enter Agilent microarray identifiers provided by Ensembl in order to obtain UniProt identifiers. This allows mapping of all over-expressed cDNAs from a microarray experiment easily to another format. Beside gene and protein names, CRONOS offers to search with 18 different identifier types. Conversion of lists of IDs into other database-IDs can be done via batch submission. The results are sent via e-mail in a comma separated value (csv) file. Web services were implemented for fully automated access (Supplementary Material S5).

Result pages in CRONOS contain mapping relevant information for UniProt, RefSeq, Ensembl and, if available, OMIM (McKusick, 2007). Additional information like protein domains, pathways and functional annotation is also provided.

In conclusion, CRONOS allows easy access to cross-references of major resources. Manually curated lists of ambiguous gene and protein names are provided.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Bussey KJ, et al. MatchMiner: a tool for batch navigation among gene and gene product identifiers. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R27. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-4-r27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote RG, et al. The Protein Identifier Cross-Referencing (PICR) service: reconciling protein identifiers across multiple source databases. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:401. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicek P, et al. Ensembl 2008. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D707–D714. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKusick VA. Mendelian inheritance in man and its online version, OMIM. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;80:588–604. doi: 10.1086/514346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povey S, et al. The HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) Hum. Genet. 2001;109:678–680. doi: 10.1007/s00439-001-0615-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt KD, et al. NCBI reference sequences (RefSeq): a curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D61–D65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The UniProt Consortium. The universal protein resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D190–D195. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.